Abstracts

Abstract

Organizational ambidexterity has been well researched. Yet, the human resource perspective on this is non-existent. We contribute by providing an empirical understanding of HRM practices at a large MNC encompassing both structural and contextual ambidexterity. Our revelatory case design provides an in-depth investigation of a French MNC. Findings suggest that an intellectual capital configuration, with relatively high levels of human, social, and organizational capital respectively is essential for fostering ambidexterity. Additionally, both a human-capital enhancing HR system and an administrative HR system aids ambidexterity. We discuss the intellectual capital architecture, HR practices, theoretical contributions, limitations, and directions for further research.

Keywords:

- organizational ambidexterity,

- HRM practices,

- intellectual capital architecture,

- French MNC,

- single case study

Résumé

L’ambidextrie organisationnelle a été bien étudiée. Cependant, la perspective des ressources humaines reste limitée. Nous contribuons avec une étude sur les pratiques de gestion des ressources humaines dans une grande multinationale qui mobilise à la fois l’ambidextrie structurelle et contextuelle. Nous présentons une étude approfondie de cette multinationale française. Nos résultats suggèrent qu’une configuration du capital intellectuel avec des niveaux relativement élevés de capital humain, social et organisationnel est essentielle pour favoriser l’ambidextrie. Nous constatons également que la combinaison d’un système renforçant le capital humain et d’un système administratif supporte l’ambidextrie. Nous discutons des pistes de recherche ultérieures.

Mots-clés :

- L’ambidextrie organisationnelle,

- les pratiques de gestion des ressources humaines,

- l’architecture du capital intellectuel,

- multinationale française,

- étude approfondie

Resumen

La ambidestreza organizacional ha sido bien investigada; sin embargo, la perspectiva de los recursos humanos es inexistente. Contribuimos aportando un estudio de GRH en una corporación multinacional que abarca ambidestreza estructural y contextual. Nuestro diseño de caso proporciona una investigación en profundidad de una corporación multinacional francesa. Los hallazgos sugieren que una configuración de capital intelectual con niveles relativamente altos de capital humano, social y organizacional es esencial para fomentar la ambidestreza. Además, tanto un sistema de GRH de mejora de capital humano como un sistema administrativo de recursos humanos ayuda a la ambidestreza. Discutimos las direcciones para seguir investigando.

Palabras clave:

- ambidestreza organizacional,

- prácticas de GRH,

- arquitectura del capital intelectual,

- MNC francesa,

- estudio de caso único

Article body

Organizational ambidexterity is an increasingly researched topic (e.g., Kang & Snell, 2009; Simsek, Heavey, Veiga, & Souder, 2009) in the organizational sciences because of its evident contributions to innovation outcomes and organizational performance (Raisch, Birkinshaw, Probst, & Tushman, 2009). This literature has long since recognized the criticality of reconciling the conflicting requirements and contradictory demands posed by two forms of learning, viz., exploration and exploitation, and the tensions involved for organizations trying to achieve this balance (March, 1991, 1996). This literature has identified mainly two different types of ambidexterity, viz. structural and contextual (Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008). Structural ambidexterity is based on an organizational design perspective and has recognized, identified, and expanded on a range of balanced organizational structures required to manage such ambidexterity (e.g., Jansen, Tempelaar, Van Den Bosch, & Volberda, 2009). Contextual ambidexterity, on the other hand, is based on the perspective of shaping the behavioral context in organizations, to enable individuals to engage simultaneously in both exploration and exploitation activities. Although the literature has also suggested two other types of ambidexterity: a) the outsourcing of explorative or exploitative activities (e.g., Baden-Fuller & Volberda, 2007), and b) the temporal cycling through exploration and exploitation (e.g., Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008), we focus this study on the two dominant types, viz., structural and contextual ambidexterity.

Despite the importance of Human Resource Management (HRM) to managing the behavioral and organizational contexts and structures within which people enable ambidextrous functioning, the HRM perspective on ambidexterity has been relatively non-existent (see Dhifallah, Chanal, & Defelix, 2008 for an exception). The literature has generally described organizational structures, and behavioral contexts as promoters of ambidexterity (e.g., Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008), both of which are dependent on the quality of the HRM system (e.g., Dhifallah et al., 2008; Kang & Snell, 2009) for effective deployment and execution. Commonly used conceptions of ambidexterity have emphasized the importance of entire HRM systems and practices such as socialization and team-building for fostering shared values (e.g., Andriopoulos & Lewis, 2009); recruitment and selection practices (Bartlett & Ghoshal, 1989); training and career development (Adler et al., 1999); job enrichment schemes, performance management, and rewards system (Gibson & Birkinshaw, 2004). Yet, it is very surprising that very little research has investigated which HRM practices contribute to the building of ambidexterity at the organizational level, especially organizations consisting of multiple businesses. Our unit of analysis is the organizational level, which is inherently multi-level because of multiple business units and/or multiple country locations.

In this paper, we address this issue by providing an empirical investigation of how MNCs manage their human resources at headquarters and across globally spread subsidiaries to build organizational ambidexterity. Specifically we investigate the nature of HRM practices, in specific configurations, that are best suited for ambidexterity in a global organization. This broad objective implies the following research question: What HR practice configurations within broader Intellectual Capital (IC) configurations are best suited for an organization that simultaneously uses different types of ambidexterity? We consider HR practice configurations embedded within intellectual capital configurations because of the compelling logic and broad literature consensus that HRM practices contribute to organizational outcomes via the mediating construct of intellectual capital (Wright, Dunford, & Snell, 2001), especially in contexts involving learning and knowledge management, such as those involving organizational ambidexterity.

As we demonstrate later, firms using contextual ambidexterity have a choice between a pair of intellectual capital configurations (Kang & Snell, 2009), with specific sets of HRM practices aiding each configuration. Firms using both structural and contextual ambidexterity, on the other hand, need to use both of the polar types of intellectual configuration types. This is because structural separation of exploration and exploitation requires different kinds of intellectual capital in these separated units. Thus, not examining intellectual capital configurations in these contexts will make it difficult to identify the relationship between specific sets of HRM practices and ambidexterity. We provide more details on these below.

To examine the above question, we identify and build on previous attempts in the Strategic Human Resource Management (SHRM) literature (e.g., Dhifallah et al., 2008; Kang and Snell, 2009). Despite their valuable contributions, work done by Dhifallah and others (2008), and Kang and Snell (2009) are limited in their scope and our collective understanding as of yet, in this context, is severely limited. First, each of these studies addresses the identification of an HRM architecture for one type of ambidexterity, thereby excluding organizations that may be using both types of ambidexterity simultaneously (e.g., Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008). It is to be noted here that contextual ambidexterity is normally conceptualized and is applicable at the business unit level (Gibson & Birkinshaw, 2004), but not applicable at the organizational level for multi-business corporations, such as our focal case organization. Second, neither of these studies addresses the challenges of managing ambidexterity in an organization with a global spread of businesses, functions, and operations, which may necessitate the use of a combination of structural and contextual approaches to ambidexterity.

Next, although Dhifallah and colleagues (2008) comparatively examined the nature of HR practices in two R&D units, each of these two organizational units were limited to either structural- or contextual ambidexterity, respectively. This work (Dhifallah et al., 2008) is therefore limited by its narrow and exclusive focus on R&D units as opposed to entire organizations. A complete understanding of ambidexterity requires a comprehensive examination of other functional areas such as marketing, and manufacturing and should encompass the entire business unit (Gibson & Birkinshaw, 2004). Additionally, Dhifallah and colleagues (2008) expected to find different HR practice configurations in R&D units using structural ambidexterity from those using contextual ambidexterity. In contrast to their expectations, however, they found that R&D organizations used ‘mixed HR configurations’ in pursuit of ambidexterity, regardless of the type of ambidexterity favored in the larger organization where they were housed. An examination of the associated intellectual capital could have resolved the ‘surprising’ finding by revealing the possibility of different HR practices contributing to the same outcome, viz., equifinality (Wright et al., 2001). Thus, an examination of HRM practices embedded in intellectual capital configurations is required to obtain a good understanding of the HRM practices contributing to ambidexterity.

Overall, we know very little about what configurations of HRM practices are best suited for an organization that uses a) structural ambidexterity, or b) simultaneously uses structural and contextual ambidexterity, in a global setting. We contribute to the literature by studying a French MNC, which simultaneously uses structural and contextual approaches to ambidexterity. Thus, in contrast to the HRM architectures for individual types of ambidexterity (e.g., Dhifallah et al., 2008; Kang & Snell, 2009), we contribute to the literature by providing an empirical understanding of HRM practices at a large MNC encompassing structural and contextual ambidexterity. We provide one of the first comprehensive qualitative empirical investigations of HRM practices in the ambidexterity literature, involving a French MNC with global (180 countries) operations.

We first provide a brief overview of the relevant literature. Next, we provide a brief review of the sparse SHRM literature on ambidexterity issues and identify the separate and combined roles of human-, social-, and organizational- capital in managing the tensions between explorative and exploitative learning. We then turn our attention to the design and methodology we use for the study. We then present the findings of our case study. Our assessment of this MNC reveals a processual view on ambidexterity, characterized by initial structural separation of exploration and exploitation activities, followed by a progressive integration. We present the findings of our investigation of HR practices within this context of processual ambidexterity consisting of both structural and contextual approaches. We characterize the configuration of HRM practices we identified at this firm and place it in the above context. Finally, we discuss contributions, limitations, and directions for future research in this area.

HRM Architectures for Organizational Ambidexterity

Following early work on organizational learning by March (1991) and his identification of exploration and exploitation learning mechanisms, the literature has defined ambidexterity as the balancing of these two distinctive and sometimes conflicting processes of learning. This literature associates exploratory learning with activities such as search, variation, experimentation, and discovery (quest of new knowledge), while exploitation is associated with activities such as refinement, efficiency, selection, and implementation (deepening existing knowledge; March, 1991: Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008). The literature describes incremental innovations (minor adaptations) as exploitative and radical innovations (fundamental changes) as explorative (e.g., Simon & Tellier, 2008; Smith & Tushman, 2005). We focus on two different means identified in the literature to simultaneously manage and balance these two learning processes constituting ambidexterity (Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008).

The first is structural ambidexterity where these two learning activities are separated into distinct, specialized organizational units. Exploration-oriented units are typically characterized by an organic design, incentives for learning and exploration, and an error-embracing management style. Exploitation-oriented units are characterized by a mechanistic design, incentives for efficiency and quality, and an error-avoiding management approach (O’Reilly &Tushman, 2008). The integration between these different units is achieved by managers who have the ability to reconcile different and opposing threads into a coherent whole. The literature suggests that complex organizational designs reconciling mechanistic and organic features are necessary for resolving the paradox involved in balancing exploration and exploitation (e.g., Adler et al., 1999; Jansen et al., 2009).

Contextual ambidexterity, on the other hand, refers to the situation where exploration and exploitation need not be nested in different units, but on the contrary can be carried out in a single business unit (Gibson & Birkinshaw, 2004). This is possible only if management sets an organizational context that encourages individuals to divide their working time between exploration and exploitation. This organizational context is underlain by four attributes, support, discipline, stretch and trust. The combination of these four attributes leads to a contextual balance between exploration and exploitation (Gibson & Birkinshaw, 2004). Comprehensive reviews (e.g., Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008) have identified two broad gaps for future research to address: a) The simultaneous presence and interaction among structural and contextual approaches to ambidexterity (the extant approach considers them as mutually exclusive), and b) The impact of international context on ambidexterity, involving multiple national business systems and cultures (the extant approach has been ‘context-free’). Examining ambidexterity in a global organization, as we do here, provides a comprehensive understanding of it in manner different from the literature’s (e.g., Kang & Snell, 1999) conclusions. We address these gaps and contribute by examining the intellectual capital and HR practices in a firm where the two hitherto mutually exclusive approaches (viz., structural and contextual) coexist with each other.

The need and rationale to examine a firm’s intellectual capital and its HR practices for ambidexterity objectives is as follows. First, ambidexterity is achieved by resolving the paradox resulting from the simultaneous management of exploration and exploitation, which necessitate fundamentally different organizational structures, strategies and contexts (e.g., Mothe & Brion, 2008; Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008). The literature identifies a strong connection between a firm’s orientation to learning and its knowledge stocks (e.g., Cohen & Levinthal, 1999). Thus, a real understanding of the ‘trade-off’ between exploration and exploitation necessitates a direct examination of the organization’s knowledge stocks and therefore its intellectual capital (Youndt et al., 2004), which represents the sum of all its knowledge stocks (e.g., Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005). Moreover, learning theorists argue that organizations do not create knowledge in and of themselves but only do so by virtue of the people (or human capital) in them (e.g., Argyris & Schon, 1978; March, 1991). Conversely however, individual learning is a necessary but insufficient condition for organizational learning (Argyris & Schon, 1978), which requires individuals to exchange and diffuse shared insights, knowledge, and mental models (Simon & Tellier, 2008) through the organization’s social capital (Youndt et al., 2004). Ultimately, the knowledge created by human capital, and diffused by its social capital, becomes codified and institutionalized in the organization, thereby turning into organizational capital (e.g., Kang & Snell, 2009). Next, researchers identify HRM as one of the more crucial investments in an organization’s efforts at building its intellectual capital, among others including Information Technology (IT) and R&D (e.g., Youndt et al., 2004). Recent work implicitly notes the importance of human capital (e.g., Dhifallah et al., 2008) and social capital (Simon & Tellier, 2008) within IT and R&D units for achieving broad organizational ambidexterity objectives, without directly examining them. Since IT and R&D functions are also dependent on people and human capital, the HRM function and its practices are among the most important in an organization for creating the context for organizational ambidexterity (Wright et al., 2001). If we are to believe that HRM practices lead to the creation of appropriate knowledge stocks in the form of intellectual capital, as the evolving consensus (Wright et al., 2001) suggests, it becomes imperative to explicitly examine HRM practices embedded within intellectual capital configurations.

The SHRM literature has only recently begun to investigate the impact of HRM practices on organizational ambidexterity (see Dhifallah et al., 2008; Kang and Snell, 2009; Simon & Tellier, 2008). While some in this literature (e.g., Dhifallah et al., 2008; Simon & Tellier, 2008) have not examined intellectual capital, others (Kang & Snell, 2009) have not addressed global context issues. Moreover, all of these studies only focus on one type of ambidexterity at a time and therefore ignore the simultaneous presence of two types of ambidexterity. Thus, our collective understanding of ambidexterity is severely limited. However, as these authors suggest, this literature contains the critical building blocks that can be assembled together to create the foundation for future studies. This body of work identifies the importance of HRM practices for developing a firm’s human capital (e.g., Lepak & Snell, 1999), social capital (e.g., Kang & Snell, 2009), and organizational capital (e.g., Wright et al., 2001), which are constituents of the overall intellectual capital (e.g., Youndt et al., 2004). Further work identifies the importance of human- and social capital for radical innovation (exploitative) capabilities, and the importance of organizational capital for incremental innovation (explorative) capabilities (Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005). Thus, intellectual capital and various profiles of it are critical for ambidextrous learning (Subramaniam & Youndt, 2005; Youndt et al., 2004). Organizations possess unique intellectual capital profiles by virtue of the different levels of human-, social-, and organizational-capital constituents. Working within the confines of a configurational approach (e.g., Huselid, 1995), and invoking the crucial concept of equifinality (Wright et al., 2001), Kang and Snell (2009) develop a pair of theoretically possible intellectual capital architectures, each combining unique types of human-, social-, and organizational capital that would be most instrumental for managing contextual ambidexterity. Additionally, Kang and Snell (2009) also identify configurations of HR practices that help the firm to manage these intellectual capital architectures to foster ambidextrous learning.

Human-, Social-, and Organizational Capital: Intellectual capital consists of three separate sub-dimensions viz., human capital (i.e., knowledge, skills, and experience of employees), social capital (knowledge residing in groups and networks), and organizational capital (i.e., institutionalized knowledge residing in systems, databases, routines etc.) (Youndt et al., 2004). Empirical research notes that high investment in HRM is associated with an intellectual capital profile with high levels of all three constituents (Youndt et al., 2004). Subramaniam and Youndt (2005) find that social capital is related to both types of innovation, as a result of resolving the paradox between the two different types of learning mechanisms described in the literature. Although Simon and Tellier (2008) do not examine social capital in their study of R&D projects, they find that the types of social networks (proxy for social capital here) are different in projects focusing on exploration versus exploitation, but are critical for both types. Specifically, they find that while a connection between dense, homogenous networks, composed of strong ties exists in exploitation projects, the connection between sparse, heterogeneous networks, composed of weak ties exists in exploration projects (Simon & Tellier, 2008). This body of work generally suggests the critical role of HRM practices and HRM investments in building intellectual capital profiles contributing to managing ambidexterity.

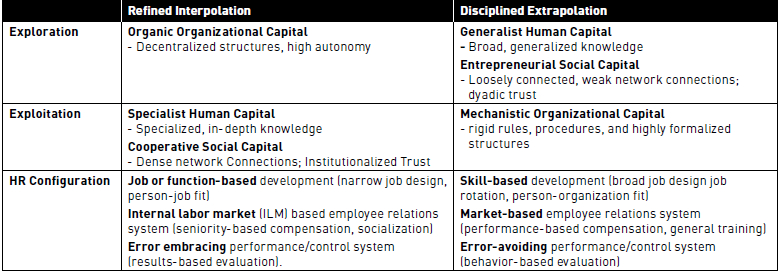

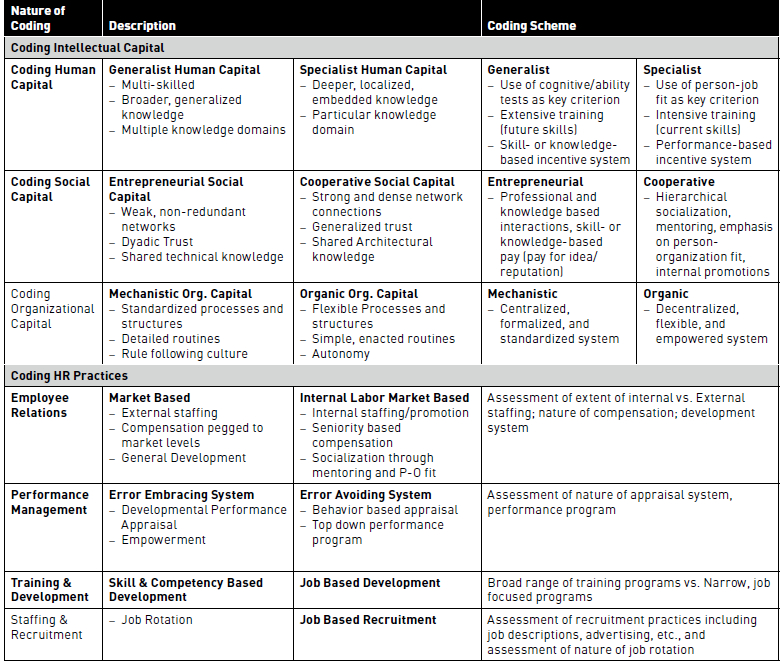

Table 1

Summary of Kang & Snell’s (2009) Intellectual Capital Architectures for Contextual Ambidexterity

Intellectual Capital Architecture: Focusing exclusively on contextual ambidexterity, Kang and Snell (2009) identify two distinct architectures, viz., refined interpolation and disciplined extrapolation as alternative mechanisms to manage ambidexterity. Refined interpolation consists of a specialist human capital, cooperative social capital, and an organic organizational capital (Kang & Snell, 2009; see Table 1). Specialist HC involves highly specialized and in-depth knowledge of a narrow domain and is thus better suited for exploitative learning mechanisms. Cooperative SC is characterized by dense network connections and institutional trust mechanisms and is inherently suited for exploitative learning mechanisms (see also Simon & Tellier, 2008). To balance the above two exploitation oriented components, Kang and Snell (2009) argue for an organic OC characterized by decentralized structures and higher levels of autonomy in groups and networks that foster more explorative learning mechanisms than the other type (viz., mechanistic OC).

The disciplined extrapolation architecture, on the other hand, consists of a generalist human capital, entrepreneurial social capital, and a mechanistic organizational capital (Kang & Snell, 2009). Generalist HC involves knowledge from across domains, inherently more suitable for explorative learning. Entrepreneurial SC consists of non-generalized, dyadic trust between individuals and loosely connected, weak and non-redundant networks generally favoring exploratory learning (see Simon & Tellier, 2008). Again, to balance the above two components’ natural inclinations towards exploration, Kang and Snell (2009) argue for mechanistic OC characterized by rigid rules, procedures, and highly formalized structures for enhancing exploitative learning.

In addition to these two types of intellectual capital architectures, Kang and Snell (2009) identify configurations of HR practices that aid these two architectures. To support refined interpolation, Kang and Snell (2009) theorize and utilize an HR configuration consisting of job or function-based development for specialist HC, internal labor market (ILM) based employee relations system for cooperative SC, and error embracing performance/control systems for organic OC. Job or function-based development is characterized by narrow job design, focused career development, and a person-job fit approach to recruitment. Internal labor market based employee relations system is characterized by internal staffing/promotion, seniority based compensation, and socialization practices (Osterman, 1984). Error embracing performance/control systems acknowledge mistakes as a natural by-product of learning, allow individuals to make decisions, to set their own performance goals, and to make changes in the way they perform their jobs (i.e., empowerment).

To support disciplined extrapolation on the other hand, these authors (Kang & Snell, 2009) argue for the use of a configuration consisting of skill-based HC development for generalists, market-based employee relations system for entrepreneurial SC, and error-avoiding performance/control system for mechanistic OC. Skill-based development is characterized by broad (multi-dimensional) job design, job rotation, and a person-organization fit approach to recruitment (Lepak & Snell, 1999). A market-based employee relations system is characterized by extensive external recruitment, performance-based compensation, and general training and development. Error avoiding performance/control systems uphold specific provisions regarding work protocols, use behavior (versus result)-based evaluation and rewards, and performance programs imposed top-down (Lepak & Snell, 1999). This work builds on the foundations built by earlier scholars and provides a theoretical framework that enables subsequent work in this area.

In summary, the only available theoretical framework in HRM (Kang & Snell, 2009) focuses exclusively on contextual ambidexterity. The rare empirical studies focus on specific organizational units (e.g., R&D) or projects within them, while focusing on one or the other type of ambidexterity (e.g., Dhifallah et al., 2008; Simon & Tellier, 2008). Thus, we do not know what kinds of HR practices, within broader intellectual capital architectures are suitable for simultaneous use of two types of ambidexterity in a global setting. We contribute to the literature by addressing this issue.

Research design and methodology

Research setting. In the tradition of studies designed to generate theoretical insights, we used a single revelatory case design (Yin, 1994) to examine HR practices facilitating ambidexterity. To develop a refined theoretical view, we conducted a case study at a MNC (listed on the Paris Stock Exchange) operating in the electrical appliances sector having global leadership positions. The company holds strong leadership positions in Europe due to the rapid development based on a dynamic policy of strategic acquisitions. For more than twenty years now, the MNC has maintained the number-one place for wiring devices and cable management worldwide, as well as number-one rankings in many key national markets.

In 2009, annual turnover of the company employing 30,000 people worldwide was around € 4 billion and its net income was almost € 300 million. The company holds from 14% to 20% of the world market share in certain products and services. It has manufacturing and/or distribution subsidiaries and offices in more than 70 countries, and sells its products in about 180 countries. Almost 60% of the business revenues are drawn from Europe, another 15% from the American continent, and the rest from all over the world. Its key markets are France, Italy and the United States, however new/emerging economies currently account for one third of its revenue.

The company is organized around three industrial divisions in charge of R&D and production and local front offices in countries, responsible for sales. The company offers integrated solutions and a complete range of specific services customized to different types of clients: residential apartments and industrial constructions, commercial buildings and hospitals, hotels and schools, etc. Sensing a need to speed up the new product development process the company, in recent years, has launched an ‘innovation challenge’ and reduced projects cycle time from four to two years. The catalogue of the MNC contains more than 170,000 offerings in the 80 categories of products.

We chose this particular company for its demonstration of consistent success at exploitative and explorative (usual proxies for ambidexterity) innovation respectively (e.g., Andriopoulos & Lewis, 2009). This company is judged by observers as being excellent, both at conducting routinized operations, and at innovating. For more than 30 years now, innovation, espoused as one of the company’s four major values, has been guiding the company’s development. In 2010, 38% of sales turnover was generated from new products; and almost 60% of the company’s investments were allocated to new products. A research and development team of almost 2000 engineers is one of the strengths of the company. The MNC possesses more than 4000 patents and spends close to 4.5% of the sales turnover on research and development. An acceleration of new product launches and a continuous search of opportunities for external growth are the two major characteristics of this company. Due to the firm’s multinational nature, balancing exploration and exploitation takes place in the context of the presence of multiple national business systems. Finally, the authors have had a longstanding relationship with this MNC, thus facilitating access to various parts of the organization as well as open conversations with informants.

Nature of Ambidexterity at this firm. At this company, the innovation process requires a constant balance between exploration and exploitation. Therefore, ambidexterity takes place at multiple levels and locations. At each level and location, specific actors or groups of actors make decisions and take action to maintain the balance between exploration and exploitation. In this section, we present the different activities in a sequential manner, but remind readers that exploration and exploitation are managed simultaneously and coexist at any point in time throughout the organization. Additionally, although we trace structural and contextual ambidexterity locations in this sequential description, we remind readers that they also coexist at any point in time throughout the organization.

First, innovative ideas originate everywhere in the organization, within subsidiaries as well as at the Headquarters. At the beginning, these ideas are generated and voiced by individuals (facilitated by suitable organizational contexts), more often than not from operational levels. In their everyday work, individuals simultaneously carry out their routine tasks and look for new ideas. The dominant mode at this stage is thus contextual ambidexterity (Gibson and Birkinshaw, 2004). The best ideas are then examined for developing potential projects. The project portfolio is made of innovative, new-to-the-firm (exploration) projects and more incremental developments of existing lines of products (exploitation). The balance among these different kind of projects is made at the tactical level by middle managers located at the HQ. Because of the structural separation of exploration and exploitation by project structure, the dominant mode in this phase is structural ambidexterity (O’Reilly and Tushman, 2008). Once the detailed study and prototyping of projects is completed, the top management team then decides on the definitive portfolio mix for the mid-term. At this stage, the dominant mode is contextual ambidexterity. Once the projects are completed, the new products are progressively transferred to production. The knowledge transformation implied is made by specific teams that work in close coordination with R&D teams while remaining structurally separate. The dominant mode here is structural ambidexterity. Heads of each country are free to adopt a new product or not and are in charge of deciding the appropriate mix of new and old products in its portfolio. Lastly, if a head of a country decides to produce a new product, local production and sales contexts must be adapted by local employees who then manage old and new products in their daily activity in the contextual ambidexterity mode. Broadly, therefore, the two forms of ambidexterity are present at different stages of the innovation cycle at this MNC. Instead of being purely structural or contextual in form, the ambidexterity at this firm encompasses a process whereby structural ambidexterity at some levels is complemented by contextual ambidexterity at other levels.

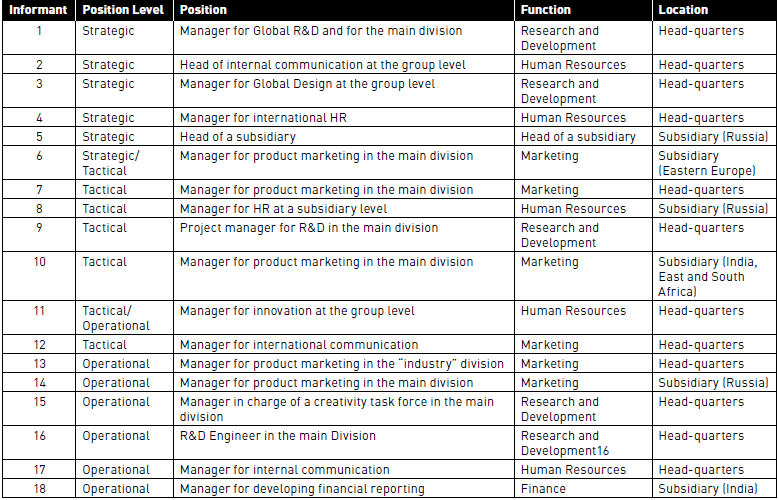

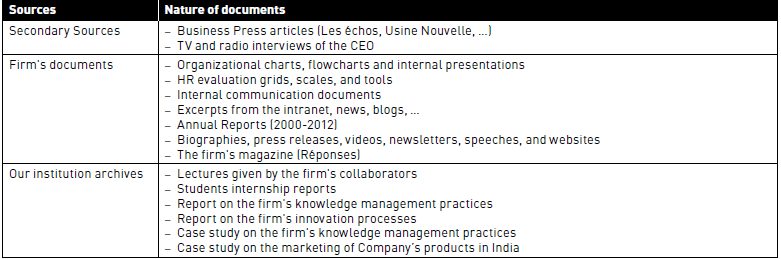

Data Sources and Collection. We, as an institution, have had a long standing relationship (since the late 1990s) with this MNC encompassing collaborative work on case study development, development of modules on innovation for the MNC, several collective research projects, regular involvement of MNC managers in our courses, supervised student internships at this company, and social interactions. By virtue of this long relationship, we had access to and utilized a variety of archival data sources such as company videos, internal brochures, newsletters, intranet, annual reports of the company, newspaper articles, published case studies (joint copyright), and previous research project documents on knowledge management processes, in addition to specifically focused interviews (between 2010 and 2011) for this particular study. We used an interview schedule specifically developed for this study, focused directly on the HRM practices associated with the exploration and exploitation processes of organizational learning. Specifically, we asked the interviewees about the company’s overall approach to exploration and exploitation respectively, their approach to managing them simultaneously, the interviewee’s role in managing these two learning processes, how these processes unfolded, who or what they saw as major contributors or critical elements of this process, HRM’s role in the process, the role of organizational structure/design in this process, and their overall evaluation of the success of these efforts. We triangulated data from the interviews with our database of different archival sources (to ensure credibility and reliability) in seeking converging evidence and inductively theorizing the intellectual capital architecture and HRM practices we develop in this study. Table 2 below summarizes functions and positions of our respondents.

We used the notion of purposive sampling (Lincoln & Guba, 1985) and selected interviewees according to two main criteria. First, we ensured that all the main functional areas where organizational learning and knowledge management were likely to play a key role were covered. Second, we selected respondents from different hierarchical levels to have an overall view of functional areas, as well as of the interactions and interdependencies with other functions. Incidentally, all of our interviewees have held different positions at headquarters and in several subsidiaries at different points in time. Utilizing these two criteria allowed us to have a global vision of the way this firm handles exploration and exploitation at the organizational level. This variety of viewpoints gave us a global overview of the firm’s functioning. These interviews helped us, both to deepen the emergent themes of exploration/exploitation activities, and to understand the managerial sensemaking efforts in critical events. We continued the data collection process until we stopped learning anything new from the additional informants and sources (Lincoln & Guba 1985).

Interviews typically lasted 110 minutes, although a few ran as long as three hours. We took detailed notes regarding our observations and interpretations, which we included in our analysis. In addition, we received permission from all respondents to audio-record their interviews, which were then professionally transcribed and validated. This corpus, presented in table 3 below, combined with our database of eighty archival documents, provided us with extensive information on the events, the innovation initiatives, and the balancing of exploration and exploitation activities.

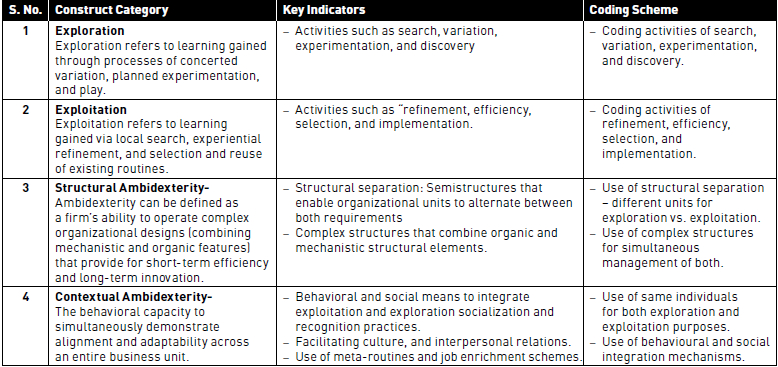

Data Analysis. We present a description of the coding procedures, following construct definitions, in tables 3a and 3b. We used existing theoretical categories shown in these tables for all our coding, following theory generation principles identified by Eisenhardt (1989), with the aim of discovering new links between them, not established in previous literature. For all the coding in this study, each of the three authors independently coded all of the relevant data sources. Differences were then discussed and reconciled in all instances. In the end, we had complete agreement for all the instances and each of the theoretical constructs used in the analysis. We analyzed the interviews for themes related to the use of human-, social-, and organization capital for explorative and exploitative learning respectively, using the guide shown in table 4b. We also analyzed the interviews for use of different HR practices for these two modes of learning respectively. In this step of the coding the relevant match of the intellectual capital constituents with the corresponding learning type emerged from the data, consistent with our qualitative/inductive approach to theory building. Overall, the process of data collection, data representation and data verification were interrelated in our study. Our theory building in this study is recursive in that it cycles among the case data, the emerging theory, and extant theory from the literature.

Table 2

Summary of interviewees’ function, position, and geographic location

Findings

Intellectual Capital Profile and HR Practices fostering Ambidexterity

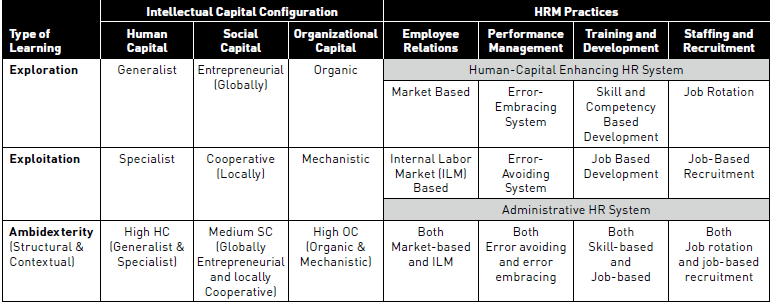

Our findings described below in detail provide an interesting picture of the ways in which HR practices and the broader intellectual capital configuration at this firm contribute to the activities of exploration and exploitation critical for ambidexterity. Table 5 shows what we found at this firm for the combined (simultaneous) processes of contextual and structural ambidexterity, both in terms of the intellectual capital configuration and set of HR practices in use. We found that ambidexterity at the organizational level comes from differences in structural and contextual ambidexterity at various organizational levels. We parse our findings and organize them in to the different rows and columns of Table 5, which distinguishes between the learning processes of exploration and exploitation on the one hand and matches them with the corresponding intellectual capital profile we identified from our data and analysis. We use these learning processes (i.e., exploration and exploitation) as the basis of organizing the findings because these are the core processes involved, regardless of the type of ambidexterity. The bottom row of table 5, labeled ambidexterity reflects the combined presence of the two types of ambidexterity. Additionally, we also match these learning processes to the corresponding HR practices. We identified the different components of the rows and columns in the table by directly associating practices with their stated purpose and by confirming their corresponding match by drawing from the literature and using our coding procedures outlined in tables 3a and 3b.

Human capital: As shown in Table 5, we see a good blend of both generalist and specialist human capital across the length and breadth of the organization for fostering ambidexterity. Broadly, we find differences in HC at different levels of analysis. Our analysis suggests that a predominantly generalist HC is used at this MNC for facilitating the learning processes of exploration, whereas the processes of exploitation seem to be more the result of a specialist HC. Alternatively, we see a relatively high level of human capital in use at this organization, providing it the necessary capabilities to be flexible and agile, and to manage the appropriate knowledge stocks and knowledge flows to foster ambidexterity. We highlight the distinction between a typological conceptualization of HC (as either generalist or specialist) and one that is continuous (from low to high) later on in the discussion section, in terms of its relevance for theory building and practice of ambidexterity. Now, we turn our attention to describing our findings related to HC by specifically focusing on their domain of application (exploration or exploitation), in sequence. Subsequently, we follow a similar structure for the other two components of intellectual capital (viz., social, and organizational), followed by the HR practices, while following Table 5 in this regard.

Table 3

Archival data sources

Table 4a

Key Definitions and Operationalizing Criteria used for Coding

Table 4b

Description of Coding Procedures

Generalist HC for exploration: Consistent with their approach to optimizing knowledge production (exploration), the group aims at managing their executive human capital to obtain these broad objectives. This translates into the utilization of expatriates from HQ in a number of subsidiaries, however, after having considered the possibility of retaining the host country executives, including those heading acquired entities. As we identified earlier, the group has grown primarily through acquisitions abroad. Even when these expatriates are used, they are typically complemented by host country executives beginning from the second (from the top) hierarchical level. This blend of executives from HQ and the host country, and in some cases, regionally sourced top managers (as country heads) provides the blending of global and local knowledge, and familiarity with the internal organizational hierarchy at HQ, to effectively carry out the task of growth through innovation. In the words of one top R&D manager,

What’s important to understand here is that our company is really a mosaic, with many entities and subsidiaries and that my task, in my roles, because I am familiar with multiple subsidiaries, multiple situational contexts, is to encourage this cross-fertilization. For example, my commercial director in Germany who went to a session in Dubai, where he ran in to one of my ex-colleagues who was head of the markets for copper bars which are used in electricity distribution, and he asked me if he could invite him to Germany for making a presentation on sharing his best practices, his work methods, and how he had so successfully managed the situation.

R&D Chief, largest Industrial Division

As this manager notes, most of these managers bring a generalized knowledge base to the table, regardless of whether this was achieved as the result of a long process of career building within the firm or outside, particularly as it applies to new knowledge generation. Another top manager within the centralized design (different from R&D at this MNC) unit at HQ shared with us his notions of the typical profile of design engineers working for him, as follows.

Let’s start with a broad overview, a designer is not an artist, is not an engineer, but is a little bit of both. We have notions of how materials can be shaped and incorporated with appropriate technologies. We have to be familiar with processes of utilizing materials to be able to communicate intelligently. But, additionally, we have to also be on top of current style trends, which are in use with new interfaces. So, there are anthropological and ethnographical components, in addition to strong technical and industrial ones, and then there are artistic components which are mostly and in general used in the company for properly installing products at the point of use.

Chief of Design, HQ

Specialist HC for exploitation: Broadly speaking, we find that at this MNC most of the exploration activities are managed at the HQ[1] while most of the exploitation activities take place at the subsidiaries. In contrast to the generalist HC in use at the HQ level, this firm uses a specialist HC at the subsidiary levels across the world. One of the subsidiary HR managers had this to say about the typical job profiles of individuals in her purview.

I have job descriptions specialized by function. We even have sub-functions. We have, for example, job descriptions such as ‘Engineer-Commercial Applications’ or ‘Engineer-Commercial Power’.

HR Manager, Russian Subsidiary

At this and other subsidiaries, it is common for this MNC to create more specialized (narrow) job descriptions and to use more of a person-job fit approach rather than a person-organization fit approach, thereby creating a specialist HC. Thus, whereas the organization fit approach would involve the use of cognitive tests, among other selection mechanisms, which would form part of a High Performance Work System (HPWS; e.g., Datta et al., 2005), this MNC uses more technical aptitude tests and assesses functional or trade competencies as part of an administrative HR system (e.g., Youndt et al., 1996) within subsidiaries. In the words of a subsidiary HR manager,

In reality, in this subsidiary, for the blue-collar workforce, we have aptitude tests for assessing their skills. But in other functions such as administrative, sales, and for white collar workers we mainly assess them on functional competence or trade skills and experience. We normally go through local recruitment agencies.

HR Manager, Russian Subsidiary

Thus, the mostly specialist HC at the subsidiary level depends on SC configurations that connect people at HQ to those in subsidiaries to help complete the processes of exploiting knowledge that can then be used in each of the country subsidiaries and corresponding markets. One of our interviewees from the subsidiary in India pointed to these aspects, as follows

We only used to formalize one (broad) project group. However, there is a project group for assistance which convenes, I’d say, on a weekly basis in France, focusing on implementing technical solutions. There, I’d say, it is more a project group that challenges a bit the R&D group based in India. That is to say, the discussions are between technical experts, and between product experts etc.

Head of Marketing, Indian Subsidiary

In addition to the above that suggests a specialist HC at the subsidiary level in terms of the individuals that compose the broader HC at this MNC, the firm also deliberately aims to identify local targets for acquisition in different countries, with the basic criteria that they bring in value-addition in the form of specialized skills. Thus, though not at the individual level, the broader strategy of the firm reflects this generalist at HQ/specialist at subsidiary dichotomy, as exemplified by the following statement,

At this point in time, following the strategic direction of our top managers, we are seeking acquisition opportunities, internationally. For example, ‘alpha’ that we acquired in India. We often make acquisitions of specialists who bring value addition to our firm in specialized products.

Manager, Internal Communications, HQ

These statements and other data from multiple locations of the firm that provide converging evidence (Yin, 1994) led us to the conclusion that this firm uses a mostly specialist HC at the subsidiaries mainly for enhancing capabilities of exploitation and therefore converting new knowledge generated from the exploratory processes for eventual use in each of the local country markets. As briefly mentioned here and as will be explained in a little more detail later, the complementary use of SC and OC mechanisms facilitates the transition from exploration to exploitation processes.

Table 5

Intellectual Capital Configuration and HR Practices for Ambidexterity

Generalist and Specialist HC for Ambidexterity: For simultaneous management of exploration and exploitation, i.e., ambidexterity, this firm uses a mix of both generalist and specialist HC configurations, although at different levels in the global organization. In addition to the above findings where we clearly distinguished between exploration and exploitation, we also found managerial mindsets and views percolating within the organization that suggested that rather than a simple addition of the two HC configurations, there were other instances where a simultaneous blend of the two HC configurations were in use. The R&D chief of the largest industrial division in the firm provides us with some insights on one such instance,

These are people dedicated to specific functions. It’s fundamental. We cannot have people doing ‘research’ all the time because it deviates from the business at hand. We cannot have people doing ‘development’ all the time because at any given moment they have to bring these two elements together. I believe that it is important to keep things moving. So there, that’s my idea. Yes they are specialized but at any moment it could change. It’s highly enriching for people and their mindsets.

R&D Chief, largest Industrial Division

In addition to the above, there were other instances of converging evidence (Yin, 1994) when the top managers at the firm pointed to having on board the firm’s payroll, specific individuals with hybrid capabilities of both specialists and generalists, especially in comparing themselves to global competitors. Thus, in addition to the simple addition of the types of HC used independently for exploration and exploitation purposes, we see a broader tendency on the part of this firm to also use a blend of specialized experts and generalists, although these knowledge bases are not necessarily located in different individuals. Moreover, middle managers throughout the organization play a crucial role in encouraging idea generation from lower level managers and employees, thus fostering ambidextrous competencies. We now turn our attention to the SC profile at this firm.

Social Capital: As shown in Table 5 we find that the SC at this firm can be characterized as globally entrepreneurial (Kang & Snell, 2009) but locally cooperative. Thus, overall we find a blend of SC types in use at this MNC, which are both critical to the ambidexterity processes at the firm. Below, we describe each of them in detail.

(Globally) Entrepreneurial SC for exploration: The SC at this MNC can be best characterized as entrepreneurial (on a global scale, i.e., from the perspective of HQ) in terms of the nature of the networks of exchange constituting loose-coupling, weak rather than tight connections, and significant levels of autonomy to key managers across levels. In addition to specific HR practices, the group also places emphasis on building and sustaining informal networks of the key people around the world, both face-to-face and technological through the intranet. These serve as effective mechanisms for circulating best practices. Although the idea generation process stems from individual initiatives, they are encouraged and supported by middle and top management, across levels. Aware of the importance of such processes, the middle management provides spaces in which these ideas can be expressed and discussed. For instance, at the Equipment and Home system division,

We have a meeting “staff and development”, every Friday. It is the French division team, but all the persons in charge of the development in the group are invited. It is at 11 am/12 noon to have Chinese, Indian, Brazilian, Hungarian, Italian people. And then, we have an exchange meeting. It is formal, we have an agenda, minutes,… but it’s really about exchanging and sharing. […] In each center, we have meetings where we are going to look at what is new, what is being made. And, at some point, I will decide to discuss this at one of the Friday meetings. It is very informative, sharing of best ideas….

R&D Chief, Equipment and Home System Division

Another instance of creating such spaces (forums) in the electronic realm for discussing ideas in a free-flowing manner was noted by the chief of internal communication at this firm, as follows

I’ll show you an example based on Sharepoint[2]. Here! This is something I created. I wanted this to be very simple, I call this “That made me think of”. In fact, I was thinking to myself that every individual who works in an organization, regardless of what kind, has a brain that functions by analogy. During the weekend, for example, we are watching TV, walking through town or on the beach…….and all of a sudden you see something that makes you think of your professional life. I told myself, therefore, that we had to create a space, in France to begin with, where people could easily recount their experiences that made them think of things. Here’s something I posted on this………….I created this in this manner because the tool permits this, a subscription. Gradually, each time there is a new post, everyone at the firm receives an email on Monday morning that says “there are new posts on ‘that made me think of’.

Manager, Internal Communication

These instances above indicate the formal and informal exchanges with loosely-coupled, weak connections, all based on organizational trust. These and numerous other such instances providing converging evidence (Yin, 1994) were shared with us that led us to the characterization of SC at this firm as entrepreneurial at the global level. Most critically, managerial accounts confirm to us that this configuration of SC seems to serve well in enhancing the effectiveness of learning processes of exploration.

(Locally) Cooperative Social Capital for Exploitation: In contrast to the entrepreneurial SC for exploration at a global level, this firm utilizes a cooperative SC at the local level in each of the countries where it has operations. As the rest of the organization, most of the work at this firm is done in project groups. These project groups at the local level have tightly coupled, close and regular interactions, all of which are better geared for exploiting knowledge that is already available in the organization. The following quote from one of our HR manager respondents highlights this, as follows

In all our departments, whether in Russia or here, we work in project mode. We have a lot of meetings where we bring together people from different functions or different sectors around a common subject. The exchange on best practices is thereby facilitated. Me, for example, I organize an international work group on processes of recruitment that respects the principle of non-discrimination. There is an American in the USA, an Italian in Italy, a Turk in Turkey, a French person in France. We do all this through videoconference or conference calls. During the event, we have multiple sessions on work dedicated to best practices on the topic. It is one way of circulating and sharing best practices.

HR head, Russian Subsidiary

These videoconference or conference call meetings, referred to in the above, are followed by local diffusion meetings at the level of each subsidiary (converging evidence across subsidiaries), again in a manner that can be characterized as tightly coupled and frequent in nature. One of the top R&D managers shared with us this view of how new knowledge and innovation is diffused throughout each of the country operations, as follows

Meetings, that’s all we have been talking about. … Every week, in all projects, there is an exchange not directly with me but with the divisional expert team and with the people that are actually doing it. It is organized, planned for every week, it works this way. There are numerous exchanges and I have expatriates in all centers. It is our strength.

Chief of R&D, Largest Industrial Division

Entrepreneurial and Cooperative SC for Ambidexterity: As described above, while we find on the one hand that SC of an entrepreneurial nature is in use, mainly to serve exploratory learning processes, we find on the other that a cooperative SC complements the former at the local subsidiary levels, for exploitation. As in the case of HC above, the appropriate SC for ambidexterity is not a simple addition of the SC types for exploration and exploitation. Instead, other mechanisms enhance the relationships between HQ and subsidiaries to manage ambidexterity. With the growth of the company, mainly through acquisitions in other countries, the HQ-subsidiary relationship has been evolving dynamically at this firm. With this changing nature of the HQ-subsidiary relationship, it is critical for the firm to reconfigure their SC to remain ambidextrous[3]. Thus, new knowledge stocks and flows of existing stocks of knowledge have to be carefully managed and kept in balance. This is done at this firm with a mixture of training, acculturation, and judicious use of a blend of inpatriates and expatriates, as suggested by the following,

I mentioned it a little earlier, weekly meetings of staff development which are global plus the training of people from international locations. There is a Hungarian currently (here). In the upward stream of projects, there is a permanent exchange. And then I have people in the reverse situation. I currently have two French people in China, one that has just come back from India, one that leaves on Monday, I will be going to Hungary next week. We have a flux of exchanges that is quite significant.

Chief of R&D, Largest Industrial Division

Thus knowledge flows and creation of new stocks of knowledge are balanced by managing the flow of people who are then acculturated and trained accordingly. This flow of people creates social capital that links the globally entrepreneurial SC with the locally cooperative SC. In addition to these socialization practices, the HR function is also trying to standardize global operations, on some fronts, in order to establish an increasingly integrated organization. In response to a direct question on the firm’s strategy to increase levels of standardization, the International HR manager (formerly a manager at the subsidiary level) had this to say,

Increasingly, yes. For example in HR, we have been organizing ourselves, for the last six months, to be a true link with the subsidiaries. For the last 11 years (when I was in Russia), I was rarely in touch with HQ. So today, we are increasingly asking our subsidiaries to do their personnel reviews on Talentis[4], to furnish a quarterly report, to really work with HQ and to exchange with them. In essence, we are standardizing the personnel review, the reporting, the mobility procedures certainly……….in HR we are getting there, in Finance it’s already been done, in logistics, we are getting there as well.

Manager, International HR

Thus, converging evidence indicates that the firm manages ambidexterity through a combination of a globally entrepreneurial SC and a locally cooperative SC, with an increasingly centralized and standardized component in global operations that serves to guide the nature of the exchange relationships at HQ, in the subsidiaries, and increasingly in relations between these entities.

Organizational Capital: The OC at this MNC is a balanced blend of both organic and mechanistic types and thus ensures the balancing of exploratory and exploitative learning processes and the tensions in managing them simultaneously. As with the two previous components of intellectual capital, we first focus our attention on exploration and then move on to a description of the OC for exploitation.

Organic OC for Exploration: Organic OC is characterized by flatter organizational structures, relatively higher levels of autonomy within each of the hierarchical levels, and flexible procedures and systems, all of which are amenable to creation of new knowledge and therefore quick responsiveness to the external environment. In the previous section on SC, we outlined how the historically free-running and independent subisidiaries were brought into the group umbrella organization with increasing levels of standardization. However, the top managers at the firm envisaged a clear end to these changes and wanted the subsidiaries and lower organizational levels in all locations to have sufficient levels of autonomy. One subsidiary head shared his view of the level of autonomy as experienced by him,

What happens is that at all levels of the enterprise you have interactions (links) with HQ. When you are in a country, in the marketing function you have teams that are in contact with those at HQ to know what new products, new trends……to be able to propose to top management of the country, a new orientation, a new commercial package…..again, it is the country head that makes the final decision. There could be conflicts of interest between one industrial division which has developed a certain number of new products, having convinced themselves that it has been good for that country, and another country that does not want to make that product. When the upstream work is poorly done, this happens quite frequently.

Head, Russian Subsidiary

This and other such interview responses provide converging evidence and a description of an organization where diversity in view-points is welcomed and encouraged, along with the associated provision of a degree of latitude for people to carry out their work. Most of our respondents also had a clear realization of the responsibility that went along with the freedom to maneuver as exemplified by the following,

In general, we are a group that is quite decentralized. So, the final decision making power rests with the subsidiary. So, if one subsidiary decides to not use a certain method developed by the group, it has the liberty. It finances it on its own. The subsidiary, then, will not contractually benefit from the sharing/leveraging of that method. It still has the liberty of developing its own means, to develop its own commercialization strategy. So there is a large degree of autonomy. That is to say, a country head, he has the liberty and room to maneuver. I would say that from the moment when one brings results to the table, there is a strong possibility that one’s strategic choices are not called into question by top management during budgetary sessions. We are a group that is quite decentralized, and I’d even say that we are a myriad of SMEs.

Chief of Finance, Indian Subsidiary

Even on a domestic basis (i.e., without taking the international context into account), the organization and its structural features are organic in nature, especially when the objective is exploratory learning and the creation of new knowledge.

We really have a culture that says that ideas are born within specific frameworks. The basic platform for new ideas, at our company, is the project. New ideas are increasingly better diffused with and through projects. …… When we made the innovation challenge we realized that employees were full of ideas but we had to be selective, we had to aid and support them in the process of implementing their ideas. Innovation is reality (here). …….It is within projects that we put a frame around ideas expressed. Here, the project advances, when we decide to make products in specific categories, the frame is provided. Beyond that we can be very participative, but it is essential to have such a frame.

Manager, Internal Communications

Mechanistic OC for Exploitation: In direct contrast to what is required for exploratory learning, this MNC’s OC is very mechanistic to ensure that sufficient levels of exploitative learning are obtained. In contrast to the decentralized nature of the structure discussed above, we found dimensions of the structure that are quite centralized, formalized, and standardized as exemplified by the following

Design is mostly centralized, it is really at the HQ. The development part could possibly be done in the subsidiaries (everything depends on the industrial structure of the division) which could be the source of idea generation. It is the same in marketing, the idea could come from a local marketer. Globally speaking we are highly centralized.

Chief of Marketing, Russian Subsidiary

There is a clear centralization of decision making at the top of the organization in some of these domains. The formalization comes from the ‘frame around ideas’ referred to in the previous comment, among others. Top management has an important role regarding innovation and the development of new areas for business. These decisions could pertain to external acquisitions or to organic growth, through internal innovation. Referring to external growth one of our respondents said,

We are very pragmatic, plenty of things come down from the CEO, I would say. I think of the strategy, of divisions and heads of subsidiaries [countries] part of whose mission is to spot potential acquisitions. It is crossed. In the end, decisions will be made by the CEO or vice-CEO but they are fertilized by lower levels.

Chief, Internal communication

Top management also plays an important role regarding internal innovation.

Top management is very important. In the growth, in entering new markets, impulsing new subjects. We are a very hierarchical organization in the sense that we are very disciplined. When they say so up there, we do so. At the same time, we are rather simple. That is, if the CEO calls one person, he won’t go along the hierarchical line. Conversely, we can call him. His line is not filtered. Anyone can call him. If he’s there, you get him

Chief of HR, HQ

Additionally, every project beyond € 250,000 requires approval by the CEO before its launch. Innovation is one of the core values of the group and its importance is regularly asserted by the CEO. Each project, regardless of whether it is innovation or an acquisition, is submitted to the top management which decides (based on formal procedures of evaluation) if it should be launched. These procedures are standardized across projects and across countries. The top management is in charge of managing the global technological and markets portfolio of the firm. Its decisions are about the structure of that portfolio and to balance the exploration/exploitation ratio at the firm level.

OC for Ambidexterity: Simultaneously managing exploration and exploitation requires a balance of the above two types of OC. Much of the balance between centralization and decentralization comes primarily in the form of the matrix structure, which is probably the best mechanism to achieve this on the one hand, and to balance global standardization with local responsiveness on the other (e.g., Burns & Wholey, 1993). In addition, the top management of this hierarchical organization also ensures a certain level of formalization and conformance to rules and procedures, where it counts. This MNC adopted a matrix structure three years ago:

We have in parallel divisions and subsidiaries (better characterized as “countries”). Within subsidiaries, one finds industrial and sales activities. The industrial part is truly matrix-like and depends of the division, while the commercial part is managed by countries only

Chief, Internal communication

Within the division, one finds all the functions of the organization (HR, marketing, development, manufacturing, etc.). Overall, the matrix structure, and especially the divisions contribute to thickening the communication network of the organization. This organization facilitates communication and knowledge exchanges between the different functions involved in the process in bringing new products to local markets. It also helps in deploying knowledge quickly in different sub environments. For instance,

In [a particular technological domain], standards are similar in switchgears and control gears from one country to another. Hence, the product can be made for several countries. […] The fact that divisions are international will help the R&D’s boss and the division’s boss impulse things elsewhere and make others benefit of all that. Our engineering departments are platform departments that work on subjects rather than countries

Chief, Internal communication

As a result, there are strong interactions between teams located in headquarters and those located in the different countries. Some of these exchanges are strictly hierarchical and to ensure that appropriate levels of higher management involvement exists where necessary, as follows

And then each project is subject to reporting (processes) which is done locally for all projects (downstream or upstream) with divisional experts. And each centre makes a report to me on mode of operation. I told you (earlier) that I speak with each centre head for at least one hour on the telephone every week. At least one hour because sometimes we have specific reports on projects where we have subsidiary heads, they could be chief of marketing, or chief of finance…..all of which is adapted to the size of the project. It is somewhat modular. We do not treat a project worth € 4 million in the same way as one that is € 400,000. We do not put in the same effort, we do not see them in the same way.

R&D Chief, Largest Industrial Division

Such exchanges also take place in support functions, such as HR or external communications. The organization envisions the HR unit as being the true link between the HQ and the different subsidiaries and there is an increasing effort on the part of the International HR group at HQ to standardize HR activities across subsidiaries in different countries. Such standardization is aimed to be in balance with the necessary levels of autonomy and country specific needs and therefore is progressing at a slow but steady pace. Such a balance between the standardization and local adjustment in HR practices gives the global organization the required mix of centralized and decentralized set of practices to create a truly transnational organization. One interviewee stressed the importance of this increase in standardization to balance the earlier existence of higher levels of subsidiary autonomy, as the company is gearing up to better match the environmental demands of balancing radical and incremental innovation in products and services.

There is an annual budget meeting during which all the subsidiaries present their budgets. The subsidiaries have a lot of leeway but they are evaluated on their budgetary performance. The budget is elaborated in strong collaboration with the divisions. The divisions have a more global vision on the budget. Some thirty years ago, everything was independent, finance has always been relatively more integrated, but now the HR function, and purchasing have also become more centralized. Nevertheless, we are not going towards complete integration. We have to stop here.

Chief of Internal Communication, HQ

HR Practices: Several HRM practices, sometimes with associated IT applications, facilitate the framing of a common context and common knowledge architecture for the entire organization. The firm uses a number of HRM practices to work in conjunction with broader initiatives for managing the ambidexterity of the global organization. The entire gamut of practices range from domestic and international mobility of executives for knowledge sharing purposes, talent management using the Talentis e-platform, training and development for managers and lower level employees, performance management practices of key executives across country borders, and the continuous and ongoing efforts to standardize the HR practices across subsidiaries, as described below. The firm strives for consistency across these HR practices to enable overall organizational objective accomplishment. All of these practices in general help knowledge flows between the headquarters in France and the multiple subsidiaries, and eventually to countries where there are no subsidiaries but commercial operations do exist.

Configuration of HRM Practices

We find that this firm uses two broad HR system configurations to manage ambidexterity successfully. First, the set of HR practices that facilitate exploration can best be characterized as ‘Human Capital Enhancing HR System’ (see Datta et al., 2005; Youndt et al., 1996), whereas the set of HR practices that facilitate exploitation could be best characterized as an administrative HR system (as shown in Table 5). We provide more details in the following.

This MNC uses an internal labor market-based employee relations approach, which primarily serves the objectives of exploitation, but resorts to a market based approach for facilitating exploration. At this MNC, performance and talent management using the Talentis platform, eventually leading to internal mobility of executives plays a key part in managing the knowledge flows. In the context of succession plans and individual preferences of key executives being considered for internal mobility, decisions are made on optimal choices among different propositions. This ensures that key executives with crucial knowledge of content and processes are utilized in locations where they are needed the most. Thus, this serves as a key component of knowledge flow and transfer initiatives, in line with broad organizational objectives identified in annual strategic plans. This is highlighted by one top HR manager at HQ:

For central functions, strategy, the HR people, top or central positions, we have the mobility platform mobilized every month by the HR people (it’s for internal mobility). There they are placed in common meetings lasting 2 to 3 hours (depending on situational factors) and top management is deeply involved in it. They consider all positions to be filled, the succession plans…all that is anticipated, and then the internal mobility is effected, we have individual interviews each year end where we see if people are inclined to move or not; if we want to have them moved because we think that it is best, but they may think otherwise. People are therefore passed through the review process and we try to examine possibilities. When we don’t have people internally, we look outside. This is done transnationally, the finance mobility platform considers the entire population of finance people. It’s done by discipline. Sometimes it is regrouped a little, as for instance, commercial and marketing

Chief, Internal communication

In terms of the performance/control system, again this firm uses a hybrid of error-avoiding and error-embracing approaches, with the former mainly aiding exploratory learning processes and the latter aiding exploitative learning. The performance appraisal and management system at this MNC is based on a mix of both behavioral and results evaluation. The annual appraisal interview serves both as a stage for setting subsequent year objectives, as well as evaluating objective accomplishment for the most recently ended year. The following quote provides details of such a process of people review.

It is a mix of both (behavioral and results-based). In the annual appraisal, there are specific objectives, with specified weights (totaling 100%); then during the appraisal interview, there is a quantitative evaluation (to what extent objectives have been attained) and narrative commentaries on performance. Even with 0% of the objectives accomplished, the evaluation could be positive.

Chief of HR, HQ

Another hybrid approach in terms of the HR practice configuration relating to Training and Development is that of the blending of a skill-based development approach with a function or job-based development approach seen in this firm. This MNC uses a mixture of programs focused on broadening managerial and employee competencies on the one hand, and those focusing on enhancing functional skills, on the other. Such an approach seems to be well-suited to the management of ambidexterity objectives, requiring both exploration and exploitation of knowledge. Such an approach is especially effective within the mixture of structural and contextual approaches to ambidexterity that we have identified to be in use at this MNC. Speaking on this issue, a senior manager in charge of International HR at HQ had this to say,

Both. We have a lot of training programmes in Russia. We have training programmes on sales techniques, time and priority management, how to make presentations, etc…..we also have group oriented training programmes by discipline, training on our products, training on our sales arguments, marketing programmes made for our group (practices and products of the group)

HR, HQ

Finally, even in the domain of staffing and recruitment, we see a combination of job-based recruitment and job rotation (including internal mobility) approaches we described earlier. The following quote from a former top HR manager from Russia speaks to this issue:

Internal mobility? It exists. It is fairly well developed and actively promoted. It works very well in France, there is mobility within work disciplines. Internal mobility on an international scale exists as well, but as it is expensive, it is less frequent. We have inpatriates who come to work at HQ (exclusively in Paris) and we have transfers between subsidiaries. But often, we stay within the same continent. It’s simple that way, …..but there are a lot of people on specific missions in Russia for specific projects (transfers in production at Y subsidiary). We have people from France and from Italy every month

Manager, International HR

This MNC manages the recruitment of its key people across the world up to a certain hierarchical level in the organization. A senior HR manager says,

The HQ is involved up to a certain level (N-1, sometimes N-2). They have their view, for recruitments for instance, they use the internal mobility platform in the course of an established process

Chief of HR, HQ

The overall focus of recruitment is on broad job competencies, supplemented by significant levels of job rotation across countries in the effort to develop a global (regional) cadre. We discuss these findings and identify implications for theory development in the next section.

Discussion