Résumés

Abstract

Many studies assume that dance develops as a bearer of tradition through iconic continuity (Downey 2005; Hahn 2007; Meduri 1996, 2004; Srinivasan 2007, 2011, Zarrilli 2000). In some such studies, lapses in Iconic continuity are highlighted to demonstrate how “tradition” is “constructed”, lacking substantive historical character or continuity (Meduri 1996; Srinivasan 2007, 2012). In the case of Mohiniyattam – a classical dance of Kerala, India – understanding the form’s tradition as built on Iconic transfers of semiotic content does not account for the overarching trajectory of the forms’ history. Iconic replication of the form as it passed from teacher to student was largely absent in its recreation in the early 20th century. Simply, there were very few dancers available to teach the older practice to new dancers in the 1960s. And yet, Mohiniyattam dance is certainly considered to be a “traditional” style to its practitioners. Throughout this paper I argue that the use of Peircean categories to understand the semiotic processes of Mohiniyattam’s reinvention in the 20th century allows us to reconsider tradition as a matter of Iconic continuity. In particular, an examination of transfers of repertoire in the early 20th century demonstrates that the “traditional” and “authentic” character of this dance style resides in semeiotic processes beyond Iconic reiteration; specifically, the “traditional” character of Mohiniyattam is Indexical and Symbolic in nature.

Résumé

Il existe de nombreuses études qui tendent à démontrer que l’apprentissage de la danse procède par le truchement d’une continuité iconique qui en assure l’authenticité culturelle (Downey 2005; Hahn 2007; Meduri 1996, 2004; Srinivasan 2007, 2011, Zarrilli 2000). Pour les auteurs de ces études, tout manquement ou interruption dans cette continuité est le signe qu’une tradition est “construite” au sens où elle aurait perdu toute authenticité historique (Meduri 1996; Srinivasan 2007, 2012). En ce qui concerne le Mohiniyattam – une dance classique de la région du Kérala en Inde – force est de reconnaître que la transmission par voie iconique ne permet pas d’en saisir l’histoire et les différentes formes. La duplication iconique qu’assure normalement le rapport maître-élève dans la transmission intergénérationnelle de la tradition a été, en effet, interrompue au tournant du XXe siècle. Par conséquent, et ce, dès les années 1960, il n’y avait pour ainsi dire plus de danseurs capables de transmettre cette forme de danse. Or le Mohiniyattam est aujourd’hui encore considéré comme une danse “traditionnelle” par ceux qui le pratique et l’enseigne. Dans cet article, je soutiens que l’usage des catégories peircéennes pour concevoir la ré-invention du Mohiniyattam au XXe siècle permet de réviser l’idée que la tradition repose nécessairement sur une continuité de nature iconique. L’examen de la transmission du répertoire Mohiniyattam montre plutôt que son caractère “traditionnel” et “authentique” repose sur des processus sémiotiques qui vont au-delà de la réitération iconique et nécessitent la prise en compte de processus indexicaux et symboliques.

Corps de l’article

Introduction

The assumption that dance moves through history via Iconic continuity – that is, through unaltered, uninterrupted, replicative action, however fallibly performed – seems logical, especially to scholars who have personally learned, embodied and performed movement and dance techniques as a part of their research (e.g., Downey 2005; Hahn 2007; Kersenboom 1987; Marglin 1985, 1990; Lewis 1992; Ness 1992, 1997, 2004; Novack 1990; Sklar 2001; Zarrilli 2000). In the case of traditional or classical dance transmission, in particular, the anthropological student imitates the teacher or the teacher instructs the student to replicate some aspect of the dance form’s technique. A famous example of this exchange is typified in Mead and Bateson’s 1978 film Learning to Dance in Bali, in which Balinese dancers learn to dance by being physically guided by the instructor and then by imitating the instructor’s movements. Likewise, dance scholar Tomie Hahn’s landmark work Sensational Knowledge : Embodying Culture Through Japanese Dance describes this process of replication in a lesson of nihon buyo dance : “She [Michiyo] concentrates on Iemoto’s every move and attempts to imitate each step” (2007 : 74). She adds : “The art of following forms the foundation of nihon buyo transmission. Following is essential, as the rudiments of nihon buyo movement vocabulary are not introduced prior to learning a dance piece” (ibid. : 86). Similarly, scholar Greg Downey describes the transmission of the Brazilian martial art/dance form capoeira as a primarily Iconic process : “Practitioners widely believe that capoeira education depends upon imitation...” (2005 : 41). In this way, replication is perceived as the main mode through which dance and movement are learned and shared.

Paul Stoller’s phenomenological-ethnographic work, like Hahn and Downey’s, emphasizes Iconic replication of repertoire over other semeiotic modes of information transfer. For example, in his work Embodying Colonial Memories : Spirit Possession, Power and the Huka in West Africa (1995), Stoller highlights Taussig’s concept of “mimetic faculty”, the process through which history becomes creatively embodied and articulates the “relationship between bodily practices and cultural memory” (ibid. : 19-20). Stoller writes : “Knowing is corporeal. One mimes to understand. We copy the world to comprehend it through our bodies” (ibid. : 40-41).

This process of replication is also described as occurring over longer stretches of time, as a process that creates history. Priya Srinivasan’s work on “kinesthetic traces” has likewise re-envisioned the inspiration of early modern dancer Ruth St. Denis.[1] Srinivasan’s work turns our attention towards the physical presence of Indian, or perhaps Sri Lankan, dancers brought to the US to perform at Coney Island. Srinivasan writes : “While St. Denis may not have trained with these dancers formally, she did in fact have kinesthetic contact that influences her creations, albeit as a receptive audience member” (2007 : 20). At its heart, “kinaesthetic contact”, as theorized by Srinivasan, is a process of imitation wherein St. Denis imitated the dancers’ turns, rhythmic footwork, mudras (hand gestures) and abhinaya (facial expressions). In all the examples discussed above, Iconic transmission does not happen perfectly, but Iconic replication is the main mode through which scholars assume that traditions perpetuate. In Peircean terms, the “representations” (in this case the dance movements) generate further Interpretants via “a mere community in some quality” (“On a New List of Categories”, EP I : 7). These he calls likenesses, more familiarly known as ‘Icons’. So, it is presumed that dance styles continue through time via a process of likeness. A student replicates the movements of a teacher : this establishes and maintains tradition.

While it is true that for many dance forms, a process of Iconic replication seems to establish itself as the primary mode upon which tradition and authenticity resides, the emphasis that dance scholarship has placed on Iconic processes has occluded other ways in which “tradition” is established and authenticated. In the case of Mohiniyattam, the female classical dance form of Kerala, South India, for example, Iconicity can neither explain, nor account for, certain developments in the tradition. The form’s continuity as traditional is important for stake-holders in the cultural community for whom it matters the most : Malayalees, dancers, scholars, Indian nationals, tourists, audience members and dance witnesses. But because Iconicity cannot account for certain developments in the tradition of Mohiniyattam, we must examine the possibility that its tradition is based on something other than Iconic continuity. To examine this possibility, this paper argues that the use of Peircean categories to understand the semeiotic processes of the recreation of Mohiniyattam dance in the 20th century allows for a reconsideration of its traditional character as resting primarily on Iconicity. An examination of transfers of repertoire in the early 20th century demonstrates that the continuous, traditional, and authentic character of this dance style resides in semeiotic processes beyond Iconic reiteration.

Scholars, historians and dancers recount the history of Mohiniyattam as having at least four distinct phases : a “golden” age; a “decadence”; a “hibernation”; and a renaissance (Bharati & Parisha1986; Jones 1973; Mussata 1986; Bhalla 2001; Rele 1992; Shivaji and Lakshmi 2004; Venu 1995). According to social reformer K. Govinda Menon, who wrote about the form at the height of its 19th century “decadence”, Mohiniyattam was a “plague” upon Kerala, “like certain contagious diseases […] an illness born in Kerala during certain seasons” (ibid. : 1895). At the close of the 19th century, because of social reforms aimed at “uprooting and destroying” (ibid. : 1895) Mohiniyattam dance, the form was, according to cultural observer Anantha Krishna Iyer, “dying a natural death” (Iyer 1912, reprint 1969 : 66-67). Then, according to Mohiniyattam dance scholar Geeta Radhika, after a long period of “hibernation” (2004 : 27-29) following its “decadence” (ibid.) there was a renaissance of the form at Kerala Kalamandalam, the state’s first institution for the arts. This renaissance began in the 1940s but did not really gain momentum until the 1960s. It was championed by the institution’s founder, Vallathol Narayana Menon (b.1878 – d.1958) who was popularly known as Mahakavi. During this period, the style underwent considerable transformation. The repertoire of the dance form was vastly reshaped and the vocabulary of the style changed, as did its accompanying music. According to Kaliannikutty Amma, an early practitioner of the re-formed version of 20th century Mohiniyattam,

Vallathol paid considerable attention to provide new expression and prestige to Mohiniyattam and for sharpening its artistic value. As a result, Mohiniyattam, the visually beautiful art form salvaged itself from obscenities and immoralities and emerged like untainted gold

Amma 1992; Translation from Malayalam V. Kaladharan 2007

Illustration 1

As described by Kaliannikutty Amma, then, Mohiniyattam’s “salvage” (in Malayalam, vimuktamaayi) allowed the form to “emerge like untainted gold”. It is this process of Mohiniyattam’s “salvage”, the act of saving Mohiniyattam’s contents from possible ruin, that is not contained in Iconicity. As we shall see, in this presumed “salvage” – the extraction of original material through time – the danced sign grew in ways that exceed replication. “Gold” cannot “emerge” from a replication of the “obscenities and immoralities” that preceded it.

To demonstrate these points, this paper gives historical background on Kerala and Mohiniyattam, then turns to demonstrating how the “gold” of Mohiniyattam emerged via a process of designative Indexing. This Indexical process allowed the dance form to remain traditional despite its radical reinvention in the 20th century.

Historical Background : Kerala

It is impossible to understand Mohiniyattam’s complex regeneration as “untainted gold” without understanding something of the social and cultural history of Kerala as well as the history of Mohiniyattam dance. Kerala, a state in Southern India, was politically unified in 1956 with the first communist government democratically elected in March of 1957. The Communist Party has been in and out of power since that time. The State formed from the princely states of Travancore, Cochin, and later, parts of Malabar, regions of which, at the time of Indian independence, belonged to the Madras Presidency, itself under British rule (see illustration 2 : Map of Kerala).

The state of Kerala has several unique cultural and historical features that distinguish it from the rest of the Indian sub-continent. For instance, it possesses a unique temple architecture style, caste system, and language (from the 12th century onwards). The state is also situated in a geographically unique manner; it is separated from the rest of the sub-continent by the Western Ghat mountains. Finally, it possesses a distinctive history of a strict feudal hierarchy. These hierarchies include the historical practice of “unseeability” which required persons of lower castes to call out their presence or to vacate the road so that higher-caste persons could avoid seeing them (the punishment for failing to do this was death or beating). Polyandrous marriage practices and matrilineal inheritance (marumakkathayam) were also common in certain Keralite communities until at least the 19th century (see Dumont 1983; Fawcett 1915; Fawcett, Evans et als. 2001; Fuller 1974; 1976; Gough 1952, 1952a, 1955, 1959, 1961, 1963; Iyer 1969; Leach 1955; Moore 1985, 1988; Puthenkalam 1977; Renjini 2000). Paradoxically, however, although caste prejudice still exists today, Kerala has progressed relatively quickly towards communal equity and justice (Franke and Chasin 1994).

Illustration 2

Map of Kerala

A few notes regarding caste (jati) in historical Kerala may help to contextualize the argument that follows. The Nayar (also spelled “Nair”) caste of Kerala is of chief concern to understanding how Mohiniyattam developed via modes not contained solely within Iconic replication and transmission since, during the 19th century (and perhaps prior), the women who practiced Mohiniyattam were “invariably from Nayar communities” (Jones 1973; Jones 2013; see also Lemos interviews 2003, 2004, 2007, 2008, 2013).[2] Significantly, these 19th century Mohiniyiattam dancers were from Nayar communities that practiced a form of polyandry in which one woman could be “married” to several men. A lack of Iconicity between historical 19th century Mohiniyattam dance and its contemporary counterpart is evident with the change in social relations surrounding the dance.[3]

In the jati structure of historical (and contemporary) Kerala, the Nayar “caste” figured between the Nambudiris (Kerala Brahmins) and the Ezhavas (a peasant class), with several “temple castes” such as the Ambalavasi in between.[4] Historically, the Nayars were a rice cultivating class but (usually) did not actually work in the paddy fields. Nayar families often administrated or owned large tracts of land, especially in the central Kerala region of Cochin Kingdom (Thrissur, Palaghat, and South Mamalapuram districts) where Mohiniyattam was widely practiced in the 19th century. Nayar men comprised the military for princely provinces and local feudal lords (Zarrilli 2000).

From the 19th century through today, though with significant modifications in dwelling habits, the Nayar community has been organized into extended family units. Historically, the joint family cohabitated with as many as fifty or more maternal relatives in a large complex called a taravadu (the term refers to both the matrilineal joint family and the dwelling place). Until the 19th century, the taravadu owned all property collectively. While today many do not like to speak about the practice,[5] in the past Nayar women practiced a type of polyandry,[6] or more accurately (in most cases), a type of serial monogamy known as sambandham. Women remained in their taravadu and did not join their “husbands” homes, and “married” several men. Women claimed all children from their relationships for the taravadu (Nair 1996 : 151-152). The karanavan, (the senior male member of the taravadu) often controlled the family’s property.[7] From around 1940, however, a younger generation of educated Nayar men employed in the British colonial bureaucracy became discontented both with the communal property system of the taravadu and the sambandham marriage system. As a consequence of this discontent, a series of early 20th century laws abolished the taravadu system of communal property and the Nayar practice of sambandham.

The 19th century locus of Mohiniyattam dance practice and performance were the Thrissur and Palaghat Districts in central Kerala, the historical stronghold of Nayar marumakkattayam (matrilineal inheritance), multiple marriage, rice cultivation, and consolidation of landholding by rich Nayar taravadus (Jones 1973; Namboodiripad 1990; see Lemos interviews with Narayanan Nambiar 20 September 2007; B. A. Amma 2008; D.M. Amma 2008; Nair 2008). Mohiniyattam dancers of this period were also nearly exclusively of the Nayar caste. Because their dance practice was intimately intertwined with marumakkattayam (matrilineal inheritance) and sambandham (polyandrous marriage practice), the changes in 20th century social relations described above had a transformative impact on Mohiniyattam and Mohiniyattam dancers.

In the caste system of Kerala, Nambudiri Brahmins ranked above the Nayar with several temple-serving castes in between. While Nayar women practiced sambadham, Nambudiri (Keralite Brahmin) families, on the other hand, married only their eldest son to a Nambudiri Brahmin woman in a ceremony called veli. This kept Nambudiri wealth and property consolidated, but left several younger Nambudiri men to remain unmarried for life. It also left many unmarried Nambudiri women (Antarjanams, literally “those not seen or heard”) cloistered within the mana or illam (Brahmin home) for the duration of their lifetime. The sambandham system allowed younger Nambudiri brothers (apphan) to have sambandham (relationships) with Nayar and Ambalavasi (temple community) women. By all accounts, sambadham was a fluid relationship that could be dissolved by either party. Nayar men also conducted sambandham with Nayar women – sometimes in cross-cousin relationships (Jeffrey 1976, 1993; Pandit 1995; Nair 1996; Saradamoni 1999; Kodoth 2001; Devika 2002, 2007).

By the turn of the 20th century, however, Nayar women and Nayar marriage and inheritance practices became a subject of legal controversy and underwent legal and social scrutiny (Jeffrey 1976, 1993; Pandit 1995; Nair 1996; Saradamoni 1999; Kodoth 2001; Devika 2002, 2007). It is at the height of these massive cultural changes that Mohiniyattam experienced what has been called its “degeneration”. It was only after its “degeneration” and “hibernation”, that Mohiniyattam’s renaissance in the new cultural landscape of 20th century Kerala managed to supersede Iconic replication; during the 19th century Mohiniyattam dance was deeply intertwined with Nayar polyandrous marital practices, while in the 20th century it was not.

Historical Background : Mohiniyattam

Prior to its “degeneration” in the Thrissur/Palaghat region of 19th century Kerala, dancers, tour guides, scholars and historians recount a long history of Mohiniyattam. Their accounts survey a pan-Kerala, and sometimes pan-South Indian historio-geography. The dance passed from teacher to student, changing places, contexts, names, and functions over several hundreds of years – but, significantly, participants in the dance believe that the form, somehow, retained a continuity of style, intention, and lineage.

The history of Mohiniyattam has three main overlapping stages : Tevadichiattam (8-12th century[8]), dasiyattam (12-19th century) and Mohiniyattam (17th century to present). The term “tevadichi” or “thevadichi” means “servant of the God” and is simply a regional Malayalam variation of the term “devadasi”. Devadasi dancers, having a variety of customs, traditions, duties, and statuses were a socio-cultural entity throughout much of the Indian subcontinent from early times.[9] Ethnographic accounts show that these women were “ever-auspicious” (nitya-sumanagli) and were ritually married to regional Hindu Gods (Kersenboom 1987; Marglin 1985, 1990; Vijaisri 2004). Devadasis had obligatory ritual practices that included dancing, singing, offering lamps, and waving fans for the Gods (Coorlawala 1992; Marglin 1985, 1990; Meduri 1996). Though not concubines or prostitutes, devadasis engaged in highly codified sexual relations with upper-caste males. Far from being morally repudiated, before the 19th and 20th centuries devadasis were treated with considerable respect by their communities (Marglin 1985, 1990; Meduri 2001).

While “Tevadichiattam” or “thevadichiyattam” translates as “dance of the tevadichi”, from around the 19th century onward the word “tevadichi” was synonymous with “prostitute” in colloquial Malayalam (Lemos personal communication with M. Samuel 2008). Significantly, according to the historian M.G.S. Narayanan, during and perhaps before the 19th century, the term “tevadichiattam” (dance of the tevadichis) specifically denoted Mohiniyattam (see Nair 1988 [1890]; Narayanan 1973; Lemos personal communication with Narayanan February 2008). With the onset of feudalism in Kerala (since the 12th century), the dance (koothu) of the tevadichi served as an advertisement for prostitution, for “powerful chieftains, Brahmins and merchants” (Narayanan 1973 : 48). In this summary we see the descent of dance from temple practice to prostitution, a familiar narrative concerning women’s dance throughout the Indian sub-continent (Coorlawala 1992; Marglin 1985, 1990; Meduri 1996).

The title used for the second phase of Mohiniyattam, dasiyattam, translates as the “dance of the dasis” (women servants of the deity). The term is often used to denote ‘dances of devadasis’. Some dancers add that there was another related practice called Avinayar kuthu that, according to some, was a combination of Nangiar Koothu and dasiyattam, and existed sometime prior to the form being called Mohiniyattam (see Radhika 2004, for example).

Finally, from perhaps the 17th century onward when we first find the term in early texts related to dance, the form becomes Mohiniyattam (Amma 1992; Bhalla 2001; Radhika 2004; see also Lemos interviews 2008). According to popular history, each change in name charts the dance’s regress as it disintegrates from a “pure” ritual practice, to a court and/or temple dance of “dasis”, and then into a corrupt secular practice instituted by rich Nayar and Brahmin landlords; Tevadichiiyattam was performed in temples, dasiyattam in courts and temples, and finally Mohiniyattam was performed in court in the South of Kerala and as popular entertainment for rich landholders in Central Kerala. This last phase – as “degenerative” performance for landlords – was followed by the forms ‘renewal and rebirth as “untainted gold” at Kerala Kalamandalam in the 20th century.

The 19th century period, which scholars and dancers term the “decadence”, “degeneration”, or “dark age” of Mohiniyattam, is historically situated after the Raja Swathi Thirunal period (1829-1847) (Jones 1973; Bharati 1986; Mussata 1986; Bhalla 2001; Rele 1992; Shivaji and Lakshmi 2004). Swathi Thirunal was a King of Travancore from 1829 to 1847. He was a patron of the arts and dancers at his court Trivandrum (Thiruvananthapauram) performed a style called “Mohiniyattam”. Before the Thirunal period, there is textual evidence of a specific dance style called “Mohiniyattam” in an Ottam Thullal play from the 1800s and in records located in the Trivandrum State Archive dating from 1821 (Kizhakkemadathil and Pushpa 1992; Jones 1973). While the music’s lyrics, ragas (melodic structure) and talas (rhythm) are extant from this time, we nevertheless have little idea of the style of this court form of Mohiniyattam.[10]

Many consider the Swathi Thirunal period (1829 – 1847) to be a stylistic highpoint in the form’s history. The Swathi Thirunal period was a time of modernization in Travancore, and like the more famous court at Thanjavur, Swathi Thirunal was a great patron of the arts, particularly music and dance. Notably great choreographers of Bharatanatyam (another classical style of Indian dance) from the Thanjavur court resided at Thirunal’s court and probably choreographed Mohiniyattam dances as well.[11] It is after the Swathi Thirunal Period of dance, when Mohiniyattam lost its patronage at court, that Mohiniyattam became problematic for social reformers in Kerala. This was the time of its “decadence”, when Govinda Krishna Menon decried Mohiniyattam as “the essence of all vices and immoral activities upon society” (1895).

The start of the “decadence” is approximate, but the years of this period encompass an intensification of British presence in Kerala, which began in the 1790s and officially ended with Indian Independence in 1947. These are also the years when Nayar marriage reform was instituted and matrilineal inheritance was outlawed : no longer were Nayar women to practice multiple marriage, and wealth was now distributed via paternal lines. At this juncture, a whole host of social, cultural and political changes focused on Mohiniyattam dance and dancers; social reformers began to interpret Mohiniyattam as a symptom of social evils.

Scholars and dancers generally give little emphasis (artistic or scholarly) to the period of “decadence”, which is seen as an aberration in the dance form’s history. We only know that at the start of print media in Kerala (in the 1890s) the form was considered degenerate. We also know that after the Swathi Thirunal period Mohiniyattam lacked patronage at court. After Swathi Thirunal’s demise, Parameswara Bhagavathara, a dancing master from Palaghat (a district in central Kerala) returned to Palaghat from Travancore with dancers trained at the Swathi Thirunal court.[12] Dance styles inevitably shifted and fused in rural Palaghat[13] resulting in the repertoire of the “decadence” (approximately from the 1890s to the1940s). Features of the “decadence” included dance practices that allowed, or required, the dancers to touch audience members, use erotic hand gestures, incorporate elements from Krishnaattam and Kurathyattam[14] and perform interactions between the dancer and the nattuvanar (conductor) on the stage (Jones1973; Rele 1992; Radhika 2004; Lemos personal communication with Kaladharan May 2004, September 2007; Lemos interview with Sri Devi-teacher June 18, 2008).

There are two extant literary sources concerning the performance of Mohiniyattam in the 19th century : Chathu Nair’s 1890 novel Meenakshi and Govinda Menon’s 1895 article condemning the form. The authors produced these literary documents as part of the reform movement aimed at reconstructing Nayar women into models of monogamous chastity. This cultural/legal project, which was largely successful, instituted monogamous marriage, blouses and breast coverings, and a legal reform of matrilineal inheritance. A key component of this project was the stigmatization and subsequent reincarnation of Mohiniyattam dance.

Although they do not label the dance by name, both Chathu Nair (1890) and Menon (1895) describe a particular dance – the infamous “search for the nose ring”, or Mukkutti dance – as a particularly notorious and offensive aspect of Mohiniyattam dance performance. This “nose ring dance” was a chief object of concern for reformers such as Vasudevan Nambudiripad and Mahakavi Vallathol (Lemos interview with Vasudevan Nambudiripad September 20, 2007). In this dance, the dancer would describe how she had lost her nose ring and then approach the audience to search for it in their clothing. The Mohini Attakaris (Mohiniyattam dancers) allegedly sat on their male patrons’ laps searching for the “missing” ring (Jones 1973; Rele 1992).

According to Menon (1895) and Chathu Nair (1890) literary descriptions, (which were corroborated by my interviews with P. K. Narayanan Nambiar, the 78-year-old ritual Chakyar Koothu artist), the dancers “sat on the lap of some of the spectators”, folded betel leaves for them to chew and smeared sandal paste on their foreheads. One can imagine how such a practice might invite sexual actions or innuendo on the part of the dancers, the audience, or both. Thus, part of the project of reforming Mohiniyattam involved avoiding the recreation, reconstructing, or remembering of such “folk” dance pieces.

Betty Jones, an American dance scholar who studied Mohiniyattam in the 1960s (1973) and Kanak Rele, another scholar and author of Mohiniyattam : The Lyrical Dance of Kerala (1992), list the Mukkutti in the pre-reformation repertory of Mohiniyattam dance. While Rele describes the dance choreography as “vulgar” (1992 : 116), Jones’ account is less inflammatory. According to Jones’ account, in the Mukkutti, after circling the audience several times “searching” for her nose ring, the dancer would approach a particular patron who had arranged that he be the focus of the dance by paying an extra fee to the dance conductor prior to the performance. The dancer would enact a scene pretending that this patron had “stolen” her nose-ring, claiming that he had hidden it in his turban. Removing his turban from his head and taking it with her to the stage, she would then “find” her nose ring. She would show it to the audience, all the while scolding the patron, and complaining that he had stolen it from her.

During the Mukkutti, the dancer would also sing a song describing how she lost the ring. Dance scholar Deepti Omcherry Bhalla (2001) records the text of the “MukkuttiSong” as follows :

Did anyone see my Mukkutti [nose ring]?

I have searched for it here and there.

But find it nowhere.

Did anyone find it?

It was made of a glittering diamond.

It was rare to buy.

It was made in gold.

Gold and diamonds.

I’ve searched it under the dhoti [male sarong], beneath the clothes.

Somewhere here and somewhere there,

But find it nowhere.

You, Potti Nampi [A Brahmin surname] from Chingavanam [a place],

Flirting members from the illam [Brahmin household]

Nayar soldiers with swords,

Did you see my Mukkutti?”

Bhalla 2001. Translation from Malayalam by Samuel 2008

The dancer probably accompanied the song with Iconic gestures (mudras) illustrating her dismay at having “lost” her nose ring.[15]

According to all accounts, the Mukkutti and the Candanam (both pieces which emphasized physical contact between the dancer and the audience) led to dancers sitting on the laps of patrons. Rele adds the Kalabham posal to this list of “vulgar” dances, in which the dancer would demonstrate (through gesture) the application of sandalwood on her friend’s entire body in advance of her friend and her friend’s lover meeting (1992 : 116).

Some patrons eschewed such “vulgar” practices. A Brahmin interlocutor interviewed during my research recalled Mohiniyattam performances of the early 20th century :

There is one item called searching for Mukkutti (nose ring). Did you hear about that? My father was a great art lover. He used to invite all the classical performers to my home – also the Mohiniyattam performers. But he ordered them not to perform this particular item

see Lemos interview with Kanur Krishnan Nambudiripad March 14, 2008

As we will see below, dances like the Mukkutti were the chief concern for reformers who felt that physical contact between the dancers and patrons was shameful. In fact, such physical contact became a symptom of other social ills which modern reformers sought to sanitize, including sambandham, women’s public bare-breastedness, and feudal power.

The Mukkutti was seen as a sign of “backwards” pre-modern behaviour, of wanton sexuality, and unconfined women. Indeed, part of the project of reforming Mohiniyattam specifically entailed avoiding the reconstruction of such dances – a decision that almost everyone in the 20th century agrees with. Eschewal of these dances helped ensure Mohiniyattam’s place among India’s other classical dance forms.

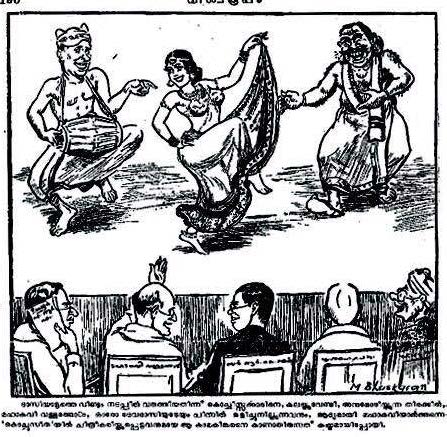

Mindful of the pivotal moments in Mohiniyattam’s history as it entered into the 20th century, we can now turn to a cartoon published in 1940. That year, prior to the project of regenerating Mohiniyattam at Kerala Kalamandalam, Viswarupam Magazine published a cartoon (illustrated by a certain “M. Bluskaran[16]) and a short play by Sanjayan – a pseudonym for writer M.R. Nayar, a popular satirist (see illustration 3). The publication was in reaction to two controversial ongoing public events. The first concerned devadasi practices in the Cochin Kingdom; the second pertained to the great poet Vallathol’s effort to include Mohiniyattam as a subject of study at his institution, Kerala Kalamandalam. The cartoon provides pivotal historical evidence concerning the reconstruction of Mohiniyattam and helps to demonstrate how its recreation superseded the process of Iconic transmission.

Illustration 3

As we will see, the cartoon’s text evidences assumed links between Nayar Mohiniyattam and devadasi dance practices in Kerala.[17] The text also connects the Indian Independence Movement with projects aimed at recasting women’s dance practices. Allusions in the cartoon, and in the short play/dialogue which follows it, serve as an attack on Vallathol, an instrumental figure in Mohiniyattam’s renaissance, who also fought for Indian independence while remaining passionate about Mohiniyattam/dasiyattam. The caption to cartoon translates from Malayalam as such :

Sad it is that Mahakavi Vallathol, while being busy with congratulating the Cochin Government for re-implementing dasiyattam, failed to see the kamakinkara (lustful person) who hides behind each devadasi and whom he [Vallathol] depicted for this first time in Kochuseetha.[18]

The caption clearly refers to the controversy caused by the “re-implementation” of dasiyattam (devadasi dances performed by Konkani devadasis) in the Cochin Kingdom. In fact, at the time of the cartoon’s publication the government of Cochin kept changing its own laws, first making the dances of devadasis in temples illegal, and then in a 1940 Act re-allowing devadasis to dance in the temples, but on a “voluntary basis” only. This meant, primarily, that devadasis could dance if they so wished, but would not get paid for performing in temples. Vallathol, who was an ardent advocate for the so-called “degenerate” Mohiniyattam, became equally passionate about the art of the devadasis of Cochin. The cartoon, taking a reactionary stance, first refers to the Cochin Government’s re-implementation of devadasi dance under this 1940 Act and then ridicules Vallathol for his support of women’s dance practices.

The cartoon plays on a perceived irony in Vallathol’s support of devadasi dance as an art form and his efforts to reconstitute Mohiniyattam. Indeed, Vallathol was already famous at the time for his poem Kochu Sita (“Little Sita” 1928), which told the heart-wrenching story of a young girl forced into prostitution as a devadasi. Yet despite writing Kochu Sita, Vallathol had publicly quipped : “If the Goddess Herself appears before me with morals on one hand and aesthetics on the other, definitely my option is the latter” (Gopalakrishnan 2014; see also Lemos interviews with V. Kaladharan May 2008). To social reformers, the performance and performers of art and its moral climate were inseparable, linked via causal Indexing. It was, therefore, a subject of ridicule and humour that Vallathol would prefer art over God.

The cartoon’s caption precedes a short play, also by Sanjayan, entitled Nattinpuram (Rustic Plain). The play is a satirical drama in which five male characters – Moidu, Alavi Master, Hajiyaar, Krishnan Master and Charu – discuss Mohiniyattam and Indian Independence. The characters Krishnan, Charu and Moidu are discussing entertainment for a Pulpparambu Pradarshanam (outdoor show) to be presented as part of the movement towards Indian independence from British rule. I have translated some of the most relevant passages of the play :

Krishnan : Then Kathakali (male dance-drama), Natakam (drama), and Mohiniyattam.

Charu : How is Mohiniyattam? Is it [performed] now? There is fun in it. I have a memory of a [performance] at my home during my childhood. Mostly ladies. There are some comic actions, such as the dancers coming amidst the people and sitting on men’s lap to search for the mukkutti, etc. Is it still [performed]?

Krishnan : Not anywhere here. I heard that it is [performed] somewhere in Cochin.

Moidu : We do not want plays devoid of goodness.

After discussing other art forms to be presented at their outdoor show, they consider how to word advertisements that will run in the newspaper. The ads will consist of two words in black type and the characters attempt to think of catchy phrases to market the show :

Alavi : I can give a model sentence. Kalayum Sadacharavum (art and morality). Both are different things. Some endorse morality instead of art. Others endorse art instead of morality. But if you want to have both, come early to the Pulpparambu Pradarshanam (literally show on the grass/ground or grass ground show).

This is an obvious reference to Vallathol’s quip concerning art and morality. Next Krishnan suggests an advertisement :

Krishnan : I shall voice one [advertisement]. Panthaloor Manayum Mangappulusseriyum (the household of the Panthaloor Brahmin family and mixed mango curry). Although both of these are incongruous, there is an inextricable relation between Pulpparambu Pradarshanam (outdoor show) and Indian independence.

Krishnan specifically conceives the outdoor show as a nationalist event. And a nationalist event, as they determined above, should exclude Mohiniyattam. The dialogue explicitly links “moral art” with the project of Indian Nationalism and, at the time of publication, Mohiniyattam was expressly not moral art. Next, Alavi suggests another ad :

Alavi : I shall speak one more [sentence for advertisement]. Some deride the Devadasis Sambradayam (devadasi system). But nobody derides Pulpparambu Pradarshanam (outdoor show). Everyone ‘congratulates’ [i.e., approves of] it.

Here the devadasi system is placed in direct counterpoint to nationalism; one can’t coexist with the other. Again the play, like the cartoon, covertly refers to Vallathol as an object of ridicule. Vallathol was passionate about reconstructing Mohiniyattam as a classical art and he championed the Cochin devadasi’s attempts to continue practicing their art in temple settings, but, to the bewilderment of other social reformers, he was also a well-known nationalist (Narayanan 1978 : 34-38).

The cartoon and the play provide evidence about the general perception of women’s dance practices from a time when such traces are scant. Let us examine the cartoon in more detail. It depicts a voluptuous woman dancing on stage. The artist has emphasized her bare shoulders and, possibly, her naked bust. (By 1940 women’s dress reform was underway. Prior to this time Keralite women did not wear any upper-garment. By the 1940s, however, many women did.) The dancer wears several necklaces, a forehead ornament, and bangles on her wrists. She holds the skirt of her sari delicately aloft between two fingers. Her right hand is on her hip and her right foot lifts off the floor as if she is performing a high “can-can” kick, with her right leg bent at the knee. Her body rotates, twisted at the spine creating an illusion so that in addition to her right hip, her left hip and breasts are also clearly visible to the audience. She smiles as she dances, gazing perhaps into the empty space, or perhaps at the nattuvanar on her left. To her left side, a hairy male figure dressed in mundu with a cloth over his shoulders approaches her with outstretched arms as if to grasp her body. He sports a large moustache (meesha), which, to this day, is the most important symbol of mature masculinity in Kerala. His feet are shod with sandals, a traditional marker of wealth.

To summarize, the cartoon signifies an inversion of what was perceived as morally correct female dance movements at that time (not that such a style existed in the 1940s, but its re-creation began shortly after this cartoon was published). That is, the cartoon depicts how a “good” woman dancing should not move. It can be read as a portrayal of immorality in motion, something that social reformers sought to end. Given the cartoon’s caption, it is clear that it is meant to depict those elements of dance that were deemed un-modern, debased, and unseemly.

The cartoon therefore functions as an inverse Icon : the imagined possibilities of an immoral performance, i.e., the image of what one ought not to do. In this inverse Icon we can see the semiogenesis of post-reform-classical Mohiniyattam dance. The 1940s cartoon is thus a shadow image of the 20th century form of Mohiniyattam dance. And in this moment a form of abduction occurs : Mohiniyattam grows into something that doesn’t yet exist in 1940. Using the contemporary form as a counterpoint to the dancer’s movement as presented in the cartoon, contemporary Mohiniyattam has no hip shaking; indeed, a conscious lack of hip movement is a feature frequently noted by teachers. If a contemporary dancer moves her hips, her teacher chastises her. There are no high kicks, jumps, sudden movements, or “lustful” glances in the contemporary form. While the dancer in the cartoon seems at risk of losing her dress, the contemporary costume covers the dancer’s entire body. The spatial patterns of the contemporary dance, which primarily uses diagonal-frontal spatial pulls, are directly opposed to the bodily rotation demonstrated by the dancer portrayed in the cartoon. Almost every movement constellation depicted in the cartoon seems in direct opposition to the contemporary form. The 1940 cartoon provides us with an anti-Icon – something that should not be replicated. Tradition must rely, then, on other modes of transmission.

Semeiotic Analysis of Changes in Tradition : Indexical Transfers

During the reconstruction of the dance, between the 1890s and 1960s, there were starts and gaps in Mohiniyattam practice. Gains in momentum were due to a cultural renaissance and the willingness of teachers to transmit Mohiniyattam and of students to learn the form. Gaps were due to the shame associated with women’s dance. When Vallathol initially wanted to resurrect Mohiniyattam, it was difficult to find students or teachers. Only after the form had been “sanitized” of elements associated with multiple marriage devadasi practices, bare-breastedness[19], and dances like the Mukkutti, were women willing to learn the style.

Just as dasiyattam represented devadasi institutions that social reformers linked to prostitution or concubinage, Mohiniyattam dance was a sign of matrilineal inheritance and all of its perceived social vices. Prior to their neo-classic incarnations (of which Vallathol’s innovations enacted the first wave), women’s dance practices did not resemble or maintain some kind of precise semantic conventional relationship to non-monogamy – they were not Symbolic of sambadham. Nor were women’s dance truly replicative or Iconic of such practices. The sign-type that forged the relationship, between dance forms and perceived social ills, was “Indexical” (EP2 : 307) in that it was grounded in a perceived relation of contiguity (i.e., a relation based on “spatial and temporal location”, Liszka 1996 : 38).

To be more specific, social reformers linked dasiyattam to devadasis, and Mohiniyattam to matriliny (marumakkathayam) as genuine Symptoms (what Peirce also called causal Indexes) (EP 2 : 274). The causal Index, or genuine Symptom, “is caused by that which it represents (a windvane is pushed by the wind indicating the direction of that breeze)” (Liszka 1996 : 38). Social reformers presented women’s dance as a causal Index of other social ills including prostitution, bare-breastedness and non-monogamy and as a result of that connection, sought to ban the dance. Because a causal Index exists contiguously with its Object, distinguishing between Index and the Object of the sign may be difficult. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, parts of the public saw dance as an undifferentiated symptom of social turpitude. This was as exhibited in riots over devadasis dancing in the Cochin temples (see Lemos interview with N. Purushothama Mallaya March 21, 2008).

As a consequence of its perception as a causal Index, in 1912 Mohiniyattam was “dying a natural death” according to cultural observer Iyer (1912, reprint 1969 : 66-67). Iyer presumes the death of Mohiniyattam to be “natural” because of the outlawing of devadasi practices and marumakkattayam (matrilineal inheritance). The former was impossible without the latter; in other words, Mohiniyattam dance simply could not survive without its surrounding cultural institutions.

Yet despite the perception held by many social reformers, it is obvious that the relation between women’s dance and social “evils” was not inherently that of a causal Index. Rather, it more closely functioned as a “Direct Referent” or a “Designative Index” (CP 8.368n). Unlike a causal Symptom, which functions naturally and contiguously, a designative Index, conversely, “results from initial labeling… for example the placement of a letter under a diagram” (see CP 2.329 as referenced in Liszka 1996 : 38). Rather than being natural to certain social practices, Mohiniyattam was simply Indexically designated under the category of “undesirable” social practices. Vallathol, it seems, was one of the only social reformers within Kerala who understood that women’s dance was not a causal Symptom of debauchery, but a “Designative Index”. This designative Index, moreover, directed the public’s attention to perceived social ills rather than art. This is why his comments on “art and morality” created such controversy : Vallathol distinguished dance from other social practices, maintaining that dance was not a symptom, but rather a designator, a non-causal sign. It was this interpretive awareness that made dance (re)creation conceivable. Had Mohiniyatam actually been a causal Index – inextricably linked with its performers and their social practices – women’s dance, as “tradition”, could not have (re)emerged as an uncontroversially moral art form. It was this realization that made it possible for Vallathol to be simultaneously a champion of Mohiniyattam and a fervent nationalist.

In accomplishing Mohiniyattam’s reform – like a finger that can point to any one particular Object – a designative Index shifted to indicate a new Object. In other words, the dance continued to serve as a designative Index although its meaning changed. In effect, a new sign was formed and the post-reform dance could now become moral art. Considering that for Peirce the Object determines the Sign (or Representamen) which then determines the Interpretant in its representation of the Object, the dance form itself had to change for the new semiotic relation to emerge. Movement actions/styles changed, consolidated, and shifted. Dances like the Mukkutti were extracted from the repertoire. The form’s movement vocabulary was redesigned, employing gestures and actions identified with the epitome of chaste femininity (see Lemos interviews with C. Jones April 1 and November 28, 2013). Many of the core features of contemporary post-reform Mohiniyattam dance – in particular the slow tempo and the lack of hip movement – derive from selective recreations formed in reaction to the period of the dance’s “degeneration”. Some of these “core features” of the contemporary form may be surviving traces of a “pre-degeneration” form; but the contemporary classical form, in its present incarnation, is a selected and consciously formed recreation of a past (i.e., pre-degeneration phase) “chaste” practice. It is expressly not the dance of the cartoon discussed above.

The pioneers of the new Mohiniyattam discarded (or could not remember) much of the old repertoire, allowing for the reconstruction of a new/old art (see Lemos interviews with C. Jones April 1 and November 28, 2013). While music underwent “sanitization” much earlier, it took far more time for dance to separate from its stigma of non-monogamous sexuality (Devika 2007). Instead of dances like Mukkutti or in “Moghul” (Muslim) dress, the repertoire now included poems and songs indicating the yearning of a wife for her one and only husband. The “folk” elements that were present in the Palaghat form of the dance, including influences from Krishnattam and Kurattyattam as well as many influences from Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, disappeared. The dance vocabulary became reinvigorated via sources from Sanskrit texts : for instance, mudras (gestures) detailed in the Hasthalakshnadeepika text and the fourfold concept of acting detailed in the Natya Sastra text and followed by other classical dance forms : Angika (motion), Vachika (music/sound), Satvika (mental emotional state/mood) and Aharya (ornamentation).

The elderly women Vallathol convinced to come to Kalamandalam to share their knowledge of the dance form had actually “forgotten” much of what they had learned in their youth. The resulting vacuum allowed for a creative re-invention of a female classical style emblematic of socially reformed Kerala womanhood. While present day Mohiniyattam shares many features with the other classical dance styles – equipoise, controlled effort, rhythmic precision – the defining aspects of the form include its curvilinear use of space, slow tempo, delicate movements and fluttering eyebrows : all coded as female movement. Dance teachers and scholars generally identify these features as an extremely stylized expression of lasya (Sanskrit : pleasing/ feminine), bhava (Sanskrit : emotional content), and sringhara (Sanskrit : love). This is not an uncontrolled love, nor a love that will escape into lust. This is a chaste, controlled sort of love : so controlled that dancers spend hours perfecting the “sringhararasa” (Sanskrit : emotion of love). According to dancers, the movement itself is “love” (they use the Sanskrit terms sringhara and lasya interchangeably). The repertoire at Vallathol’s Kalamandalam (what is now a “classical” dance tradition) was built on the hazy memories of three elderly women, a process that came in fits and bursts with teachers changing (or dying) and few students in attendance until a teacher named Chinnammu Amma became head of dance in 1942 (see illustration 4). But though Chinnammu Amma had learned Mohiniyattam in her youth, she had also forgotten much of her repertoire.

Illustration 4

In spring of 2008 I met with Kanur Krishnan Nambudiripad, a researcher and musician at Kalamandalam in the early days of the institution. We spoke at his house near Thrissur for several hours, drinking coffee served by his wife while a strange torrential rain poured outside (it was not monsoon season and such rains were odd at that time of year). We spoke in English and Malayalam and had a sprightly discussion, with him at certain points becoming very animated about the “inauthenticity” of Mohiniyattam compared to other classical dances such as Bharatanatyam and Kathakali. In the following discussion I rely heavily on the memories of Kanur Krishnan Nambudiripad, as he may be one of the last living people to see Chinnammu Amma’s performances at Kalamandalam. According to Kanur Krishnan Nambudiripad, Chinnammu Amma’s repertoire was very limited :

Vallathol announced that they would start dance classes. He announced that it was very difficult to get a teacher. He had searched a great deal, and at last found out a woman, who is [sic] about 40 or 45 years old [Chinnammu Amma]. I very distinctly remember that. So I can share what I saw there [at Kalamandalam]. She performed two items. One was a Chollkettu. Do you know that item?

I went to Kalamandalam in 1952. There are the only two items she performed : a Chollkettu and a Varnam. And in 1952, she taught only these two items.

Kalamandalam claims there was some padams [short poetic pieces] in her repertoire also, but I am sure they were not there, because she didn’t perform those dances. You know that it is much easier to perform a padam rather than a Chollkettu or Varnam. [A padam is shorter and easier to remember than the lengthy Varnam choreography]. And it is more easy [sic] to attract the people’s attention with padam. She did not perform that [piece]. And these things [performed today] nobody is performing with any resemblance [to her performance] at all.

I asked Kanur Krishna Nambudiripad about Chinnammu Amma’s performance :

She performed Yadukula Kamboji Varnam but there were a lot of mistakes… but they can be corrected. There were a lot of mistakes. I was told that she learned Mohiniyattom only after the age of 30. I think her teacher was Kalamozhi Krishna Menon; I think so. So, after she made this program at Kalamandalam, she was appointed there. I think it was in 1951. The records will be there at Kalamandalam. I was called to sing for her dance performance. But I didn’t sing for this Mohiniyattam because there were a lot of mistakes so I refused to sing.

I asked :

What sort of mistakes? What do you mean by mistakes?

He responded :

In the music there were mistakes in the lyrics, and in the thalam [rhythmic cycle]. She tried to recreate it, but she is a very mischievous lady and there are [sic]many mistakes. The talam is not proper one… We can’t sing for that… If it is Aadi talam, there should be 32 different syllables. [In this Chollkettu] some of them were missing. Then how can we sing? I told her that I cannot sing… Nobody can sing like this. So, whatever it [Mohiniyattam] was, it was misplaced.

I don’t think that Mohiniyattam is an original [type of performance]. That’s a problem. That means Chinnammu Amma contributed only a bit. And that also these people are [now] doing something with it.

When Chinnammu Amma performed. That was the only thing we had. In Chinnammu Amma’s style there was lot of manipulation. But it was original. What Chinnammu Amma had was original.

Mohiniyattam has big problems. How it is presented is very sweet. But if it is too much of sweetness, what will happen? You feel fed up. Feel like vomiting, but if it is a bit spicy, it is okay. Bharatanatyam is something very spicy. There is lot of variety. But in this here [Mohiniyattam] is only sweet. That is the great problem. That is, can you tolerate watching Mohiniyattam continuously for three hours? No no. You will feel fed up, because there is no variety.

I asked him :

So why was there no effort to add variety back in, at Kalamandalam? They could have done anything they wanted? They [the pioneers] had a blank slate, with only a few ingredients. So why didn’t they expand the form?

And he replied :

They got only some sweet things. They tried to develop that. That’s all... When the thread is broken it is difficult, or impossible to put back

see Lemos interview with K.K. Nambudiripad March 21, 2008

According to all the women I interviewed who studied at Kalamandalam with Chinnammu Amma, there were very few dance choreographies in those days, and also very few aduvus (dance steps). One famous Mohiniyattam dance teacher, Kalamandalam Leelama, related me to how, in the early years at Kalamandalam, the students would take lessons with Kapuratte Kunjukutty Amma at her home, but the elderly lady was so advanced in years that she could not remember what they had learned from one day to the next. There was no cohesion in the lessons and the students were unable to learn any dance pieces from her (Lemos interview with Leelama May 18, 2008).

If the younger dancers could only learn simple snippets of movement and perhaps two entire dance pieces from Chinnammu Amma, on what foundation does this “great tradition” stand? While other classical Indian dance traditions drew great inspiration from replicating temple sculptures of dancers (for example the sculptures at Konarak and at Chindambaram), Kerala boasts few temple sculptures for dancers to replicate. Given this, combined with the scarcity of the repertoire transmitted by Chinnammu Amma at Kalamandalam in the 1950s and the relative paucity of the repertoire transmitted by Krishna Pannikker to Kalyanikuttyamma before her, how was today’s vast traditional classical repertoire built?

Given that much of the repertoire was consciously edited while other parts of it were simply forgotten, one way that the style was established as tradition was via co-presence. In the case of Mohiniyattam, this was the perfect solution to establishing a tradition that scarcely resembled that which came before it (see illustrations 5 and 6). The physical presence of elderly Mohiniyattam dancers at Kalamandalam – such as Kalyani Amma, Madhavi Amma, Kapuratte Kunjukutty Amma, and Mohiniyattam conductor Krishna Panniker – provided a link, a designative Index that could point to the past without being its symptom; Iconic replication of their limited repertoire was simply an additional benefit.

And so, the transfer of tradition in Mohiniyattam has less to do with Iconic replication, whereby younger dancers mimic the elderly dancers’ repertoire (though this type of transfer also occurred to a limited degree), than with the proximity of elderly dancers to younger pioneers such as Kalyannikutty Amma and Satyabhama. The many photographs taken of very elderly dancers (one of whom had severe arthritis and memory loss) alongside the women who became prominent Mohiniyattam artists in the 20th century is one clue that the tradition (as it emerges from the 19th into the 20th century) rests more on Indexical and Symbolic processes rather than the Iconic replication of an older repertoire (Rele 1992; C. Jones’ personal collection of historical photographs). Another clue is the many shifts in costume and hairstyle for the dance form as it developed from the late 1950s to the 1990s.

This shift in thinking (from understanding tradition as based solely in Iconicity to understanding it as based on a combination of Iconic, Indexical and Symbolic transfers) allows me to argue for the robustness of the tradition despite its radical reinvention. Because the transfers were not built on Iconicity – imitation or replication – the social stigma attached to the movement and its performers could shift.

Illustration 5

Illustration 6

Illustration 7

Illustration 8

Elements of the deliberate sensitization at Kalamandalam included vast changes to the dance vocabulary, a near reinvention of the style. Vallathol, whose ideas about womanhood and nation-building are well documented by Sankaranarayanan (1978 : 27-33), instructed dancers to avoid flirtatious glances and erotic gestures, and encouraged the use of the Sanskrit concept of “lasya” in relationship to the movement technique. Much of the extant repertoire was discarded. Nevertheless, from the 1930s into the 1950s, the dancers/dance had such a bad reputation that no student would learn the dance at Kalamandalam. Only after the dance had been nearly completely recreated and had moved from the generation of dancers associated with the old “degenerate” style of Mohiniyattam to a younger generation (around the 1960s) did the dance begin to become accepted as a classical style throughout India.

Conclusion

Like other forms of classical dance, Mohiniyattam has been reconstructed and radically refashioned. Yet, it has also come to represent ancient Indian tradition. This process involved a complex exchange of repertoire, informed by arts maestros, an archive of Sanskrit texts, and the raga and tala systems of classical Indian music, which enabled the creation of classical Indian dance forms. To see dance practice as replicated Iconically and to interpret dance as the embodiment of an Icon (a Hypoicon) seems self-evident. Dance, one might presume, grows out of imitation of the natural environment, or through Iconic replication and display of emotional states. Dance tradition as movement technique passed from one body to another seems to rest comfortably in the order of Firstness : “the mode of being of that which is such as it is, positively and without reference to anything else” (CP 8.328). And yet this misreading denies dance the ability to persuade, to change, to grow, and to manifest realms of meaning beyond the imitative while retaining is traditional character. Because the continuity of Mohiniyattam dance is not solely contained in Iconicity, it can embody both polyvalent growth and conventional continuity.

While the “master narratives” of internationalism, Indian nationalism, Orientalism, and colonialism helped to shape contemporary classical Indian dance practices, this does not diminish the importance that dancers and choreographers place on these styles as traditional and spiritual practices, nor does the lack of a robust Iconic replication limit the repertoire’s scope as traditional and classical (Meduri 1996). In part because its tradition is built upon Indexes and Symbols in addition to Iconic transfers of knowledge, the dance that was once degenerate can now be expressly moral art. Today, in the post-revitalization era, instead of Indexing “problematic” female sexuality classical dance now directs attention to more general categories, such as “femininity”, “ancient tradition”, “Hindu spirituality”, and “Keralite and Indian culture”.

The Indexical tradition – that is, the tradition that emerges out of Indexes more than Icons – may be uniquely important in South Asia. Simply sitting near the Guru (teacher), even if the teacher never speaks and even if one doesn’t replicate their actions, can at times be seen as sufficient for the transfer of wisdom. Discussing the transmission of knowledge within the lineages of modern postural yoga, Sanskrit scholar Christopher Wallis justifies Guru Krishnamacharya’s direct transmission of sacred knowledge from a disembodied siddha (master) Krishnamacharya called Naathamuni as a “perfectly valid claim within the tradition, which possesses an “open canon” that can theoretically be added to at any time – and transmission from disembodied beings in dreams and visions is well-attested, as we have seen” (Wallis 2012 : 319). The construction of tradition is imperfect and fallible, but lack of Iconicity should not lead us to believe that tradition is impossible, or simply a figment of the imagination for participants in that tradition. Indexical transfers of tradition are as legitimate as those built on Iconic replication and/or Symbolic identification.

Having grown out of a designative Index that allowed the form to re-shape in the 20th century, Mohiniyattam, as a Symbolic complex, is a phenomenological Legisign-entity[20]. The rules that structure the movement form are conventional Legisigns, built upon aesthetic principles and conventions aimed at producing the culturally constructed “lasya” quality (feminine). Importantly, the properties of the form attributed as lasya are arbitrary. There is no particular reason (beyond cultural convention) why a quality of gentle, light, delicate and refined movement, for example, should link to the Sanskrit concept of lasya (femininity). To restate the above in another way : the Legisign, or habit, that comprises the movement Symbol of a particular aduvu (dance step) endows the aduvu with the lasya construct, which is then reiterated through an Interpretant; in this way the aduvu becomes reflective of feminine ideals. This ability for polyvalent growth makes it possible for politicians to parade themselves with Mohiniyattam dancers as a Sign of auspiciousness, tradition and Kerala state-hood, though in earlier times the form was considered a distasteful social plague.

Certainly Mohiniyattam dance does Iconically replicate certain features of the Kerala landscape; to cite a specific example, the language of mudras Iconically replicate flowers, birds, and a variety of other objects and ideas. Likewise, a performance of contemporary Mohiniyattam does replicate some features of past practice to a degree, though how much is extremely difficult to determine. Music for new choreographies is often taken from 19th century compositions by Maharaj Swathi Thirunal, and in this way, these compositions pull an element of the past into the present : a “salvage”. Nevertheless, the form does not enact a past lifestyle before our eyes exactly, nor does it perfectly replicate an ancient tradition of dance, though it may remind us of these things. The persistent identification of the technique with a more general type of tradition, a tradition based upon designative Indexing, is ultimately Symbolic (that is, conventional or habitual, in Peirce’s terms).

Despite a radical transformation of the form’s costume, hairstyle, and musical compositions, Mohiniyattam has a persistent identification with the ancient past. Just as an utterance of the word “bird” cannot show us a bird nor act it out before us, it can conjure an imaginary sense of a bird in the mind of an informed interpreter; the form does not replicate the past nor somehow conjure it up. Yet the form “is connected with its object by virtue of the idea of the symbol-using mind, without which no such connection would exist” (EP2 : 9). The contemporary form remains a conventional Symbol of an enduring ancient past; an unaffected and “pure” manifestation of Keralite cultural roots incarnated into the present. The Symbolic mode allows for Mohiniyattam’s interpretation as an enduring tradition despite its radical re-invention.

Parties annexes

Biographical note

JUSTINE LEMOS holds a Ph.D. in Cultural Anthropology from University of California Riverside. She also holds a Master’s degree in Dance Ethnography from Mills College, a Master’s degree in Anthropology from UC Riverside and a B.A. in World Dance from Hampshire College in Amherst, MA. From 2003-2004 she held a Fulbright Grant in Kerala (India) where she researched the politics of gender as manifest in the sub-culture of classical Indian Mohiniyattam dance and was a research scholar at Kerala Kalamandalam. She returned to India to continue her studies in Malayalam language and Mohiniyattam dance in 2005 and then again as a recipient of the American Institute for Indian Studies dissertation award fellowship from 2007-2008. She was an American Association for University Women Dissertation Writing Fellow for the 2008-2009 year. She currently teaches classes, workshops and gives papers as an invited presenter at several colleges and Universities. She is also a professional dancer and performs in the Odissi and Mohinyattam classical Indian dance styles.

Notes

-

[1]

Earlier dance scholarship has routinely credited a cigarette poster with St. Denis’ inspiration for the creation of “Oriental” dances.

-

[2]

At least one nattuvanar (dance conductor) was a Tamil Brahmin, perhaps originally from the Coimbatore region accessible just through the “Palaghat gap” in the Western Ghats Mountain range (Namboodiripad 1990). Some Mohiniyattam dancers were from Ambalavasi (temple-serving) communities (Lemos interviews with C. Jones 2013).

-

[3]

In a recent interview, Dr. Clifford Jones – who interviewed Mohiniyattam dancers in the 1960s – stated that a few of the early Mohiniyattam dancers were from Ambalavasi, or temple servant, castes.

-

[4]

Amabalavasi is a generic term referring to any non-Brahmin caste who served in temples. This designation includes the Chakyar, Nambiar, Pothuval, Pushpakas, Muthatu, Variar, Pisharody and Marar castes, each with a particular temple duty.

-

[5]

Historian M.G.S. Narayanan stated in an interview with me that “No one wants to speak of it now, but there are many grandmothers whose children are one from a police officer, one from a government worker, etc” (Lemos : January 31, 2008). A close friend also related to me that his grandmother had several such alliances over the course of her life.

-

[6]

Sambandham was not a polyandrous relationship with one woman married to a set of brothers. A woman’s sambandham partners were usually unrelated to each other.

-

[7]

Scholars debate the influence of the karanavan, the relationship of this role to colonial government structures, and his control of women of the taravadu. Some scholars saw the karanavan as the real power-holder of the taravadu, while others place the power among the Nayar women (see Kodoth 2001 : 362-371).

-

[8]

I approximated these dates with the assistance of the eminent Keralite historian M.G.S. Narayanan. He sourced them from a variety of temple inscriptions that use the term “tevadichiyattam” from the 8-12th centuries. I have found no archival source in Kerala for the use of the term “dasiyattam” but in interviews elderly maestros used it to denote the dance performed by devadasis rather than the term “Mohiniyattam”. We should note that Mohiniyattam dancers of the 19th century did not, for the most part, have obligatory duties or employment to dance at temples for the entertainment of Gods.

-

[9]

Vijairsri contends the academic/ethnographic category of devadasi conflates a variety of regionally and ritually specific categorizations such as yogini, sane, nautch, sule and boghum (2004).

-

[10]

The very few Varnam pieces performed by Chinnammu Amma and Kalyanni Amma (the earliest teachers of Mohiniyattam at Kerala Kalamandalam) may have traces of this court repertoire.

-

[11]

In the Travancore temples it was also devadasi custom to sometimes adopt women from Nayar communities (Thurston 1909 : 140).

-

[12]

However, earlier in the 19th century Mohiniyattam dancers were brought to Travancore from Central Kerala to live and perform at court in Travancore. The form’s relationship to central Kerala, and therefore to polyandry and matrilineality, is long-standing (Menon 1978; Shivaji 1986).

-

[13]

The geography of Kerala is largely isolated from the rest of India. Palaghat, however, has a channel through the Ghats Mountains known as the Palaghat Gap. This gap allowed dancers to travel to and from Tamil Nadu, resulting in a fertile mixture of dances.

-

[14]

Two folk dance styles.

-

[15]

For North Indian tawaif dancers, “the nose-ring, made of gold or silver, was traditionally recognized as a symbol of her [a dancer’s] virginity. Its removal signified her initiation into her new profession” as a courtesan (Nevile 1996, 2005 : 77). Mohiniyattam dancers were also known to dance in “Moghul” (Muslim) costume. These might all be influences from the Muslim court at Mysore on the dance.

-

[16]

“M. Bluskaran” is an unknown figure.

-

[17]

While 19th century Mohiniyattam dance shared many features with devadasi dances, as far as I can tell Mohiniyattam dancers did not dance at temples professionally for the entertainment of Gods, and nor did they identify themselves as devadasi. On the other hand there were dedicated devadasi dancers at temples in the Cochin Kingdom. These dancers were from the community of Konkani Goans, a minority in Kerala who spoke Konakani as their first language.

-

[18]

Kochuseetha is a famous poem by Vallathol about the sad fate of a young devadasi.

-

[19]

19th century dress for Nayar women had no covering for their chest.

-

[20]

For Peirce, a legisign is a sign whose repesentative character is based on a law or a habit. Such a sign is general and is of the nature of a type : “A Legisign” writes Peirce, “is a law that is a Sign. This law is usually established by men. Every conventional sign is a legisign. It is not a single object, but a general type which, it has been agreed, shall be significant” (EP2 : 291).

Bibliography

- ALEXANDER, K. C. (1968) Social mobility in Kerala. Poona : Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Institute.

- AMMA, KALIYANIKUTTY, K. (1992) Mohinyiattam-Charitravum Aattaprakaravum (Mohiniyattam- History and Acting/Dancing Manual). Kottayam : D.C. Books.

- ARUNIMA, G. (2003) There Comes Papa : Colonialism and the Transformation of Matriliny In Kerala, Malabar, c.1850-1940. New Delhi : Orient Longman.

- AYYAPAN, S. K. (1952) “Response of Sahodharan K. Ayyapan to Social Issues”. InBiography of Sahodharan K. Ayyapa. M.K. Sanoo (Ed.), Kottayam, Kerala : D.C. Books

- BHALLA, D. O. (2001) Keralathile Lasyarachanakal. Kottayam : D.C. Books.

- BHALLA, D. O. (2006) Vanishing Temple Arts : Temples of Kerala & Kanyaakumaari District. Gurgaon : Shubhi Publications.

- BHARATI, S., and PASRICHA, A. (1986) The Art of Mohiniyattam. New Delhi : Lancer International.

- CHAKRABORTHY, K. (2000) Women as Devadasis : Origin and Growth of the Devadasi Profession. New Delhi : Deep & Deep Publications.

- CHANDU MENON, O. (2005 [1889]) Indulekha. A. Devasia (trans.), New Delhi; New York : Oxford University Press.

- COORLAWALA, U. (1992) “Ruth St. Denis and India’s Dance Renaissance”. In Dance Chronicle – Studies in Dance and the Related Arts (15) 2 : 123-152.

- DANIEL, E. V. (1984) Fluid Signs : Being a Person the Tamil Way. Berkeley : University of California Press.

- DAUGHERTY, D. (1966) “The Nangyar : Female Ritual Specialist of Kerala”. In Asian Theatre Journal (13) 1 : 54-67.

- DEVIKA, J. (2002) “Imagining Women’s Social Space in Early Modern Keralam”. In Center for Development Studies. Working Paper Series no. 329 : Center for Development Studies : Thiruvananthapuram.

- DEVIKA, J. (2005a) Her-Self : Early Writings on Gender by Malayalee Women, 1898-1938. Kolkata : Stree.

- DEVIKA, J. (2005b) “The Aesthetic Woman : Re-forming Female Bodies and Minds in Early Twentieth-Century Keralam”. In Modern Asian Studies (39) 2 : 461-487.

- DEVIKA, J. (2007) En-Gendering Individuals : The Language of Re-forming in Early Twentieth Century Keralam. Hyderabad : Orient Longman.

- DIWAN, P. (1994) Women and Legal Protection : Indecent Representation of Women, Equal Remuneration, Sati, Devadasi System. New Delhi : Deep & Deep Publications.

- DOWNEY, G. (2005) Learning Capoeira : Lessons in Cunning from an Afro-Brazilian Art. Oxford : Oxford University Press.

- DUMONT, L. (1983) “Nayar Marriages as Indian Facts”. InAffinity as Value. Chicago : University of Chicago Press.

- FAWCETT, F. (1915) Nâyars of Malabar : Anthropology. Madras : Printed by the Superintendent Government Press.

- FAWCETT, F. (1985) Nayars of Malabar. New Delhi : Asian Educational Services.

- FAWCETT, F., EVENTS, F., and THURSTON, E. (2001) Nambutiris : Notes on Some of the People of Malabar. New Delhi : Asian Educational Services.

- FRANKE, R., and CHASIN, B. (1994) Kerala : Development Through Radical Reform. New Delhi : Promilla & Co.

- FULLER, C. J. (1974) Nayars and Christians in Travancore. Ph.D. diss., University of Cambridge.

- FULLER, C. J. (1976) The Nayars Today. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press.

- GOTTSCHILD, B. D. (1996) Digging the Africanist Presence in American Performance : Dance and Other Contexts. Westport, CT. : Greenwood Press.

- GOUGH, E. K. (1952) “Incest Prohibitions and the Rules of Exogamy in Three Matrilineal Groups of The Malabar Coast”. In International Archives of Ethnography (46) : 81-105.

- GOUGH, E. K. (1952a) “Changing Kinship Usages in the Setting of Political and Economic Change Among the Nayars of Malabar”. In Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (82) 1 : 72-88.

- GOUGH, E. K. (1955) “Female Initiation Rites on the Malabar Coast”. In Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (85) : 45-80.

- GOUGH, E. K. (1959) “The Nayars and The Definition of Marriage”. In Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (89) : 23-34.

- GOUGH, E. K. (1961) “Nayar : Central Kerala. Nayar : North Kerala”. InMatrilineal Kinship. D.M. Schneider and E.K. Gough (Eds.), Berkeley : University of California Press : 298-404.

- GOUGH, E. K. (1963)

- GOPALAKRISHNAN, K. K. (2014) “She Shaped the Art!” In The Hindu Newspaper, January 31.

- HAHN, T. (2007) Sensational Knowledge : Embodying Culture Through Japanese Dance. Middletown, CT. : Wesleyan University Press.

- IYER, A. K. (1969 [1912]) The Cochin Tribes and Castes Published for the Government of Cochin by Higginbotham, 1909-12. New York : Johnson Reprint Corp.

- JEFFREY, R. (1976) The Decline of Nayar Dominance : Society and Politics in Travancore, 1847-1908. New York : Holmes and Meier.

- JEFFREY, R. (1993) Politics, Women and Well Being : How Kerala Became a “Model”. Delhi : Oxford University Press.

- JONES, B. T. (1973) “Mohiniyattam : A Dance Tradition of Kerala, South India”. In Dance Research Monograph One. P. A. Rowe and E. Stodelle (Eds.), New York on Research in Dance, , New York University : 9-47.

- KERSENBOOM, S. C. (1987) Nityasumangali : Devadasi Tradition in South India. Delhi : Motilal Banarsidass.

- KODOTH, P. (2001) “Courting Legitimacy or Deligitimizing Custom? Sexuality, Sambandham, and Marriage Reform in Late Nineteenth-Century Malabar”. In Modern Asian Studies (35) 3 : 349-384.

- KRISHNA IYER, L. A. (1968) Social History of Kerala. Madras : Book Centre Publications.

- KIZHAKKEMADATHIL, G., and PUSHPA, B. (1992) Folios of History. Trivandrum State Archives.

- LAKSHMI, R. (1995) At the Turn of The Tide : The Life and Times of Maharani Setu Lakshmi Bayi, The Last Queen of Travancore. Bangalore : Maharani Setu Lakshmi Bayi Memorial Charitable Trust.

- LEACH, E. R. (1955) “Polyandry, Inheritance and The Definition of Marriage”. In Man (55) : 182-186.

- LEWIS, J. L. (1992) Ring of Liberation : Deceptive Discourse in Brazilian Capoeira. Chicago : University of Chicago Press.

- LISZKA, J. J. (1996) A General Introduction to The Semiotic of Charles Sanders Peirce. Bloomington : Indiana University Press.

- MADHAVAN PILLAI, P. (1981) Malayalam-English-Hindi Dictionary. Changanacherry, Kerala : Assissi Printing and Publishing House.

- MADRAS MALABAR COMMISSION. (1891) Report of the Malabar Marriage Commission, With Enclosures and Appendices. Madras : Printed at the Lawrence Asylum Press.

- MANMADHAN NAIR, V. (2004) Padmanabhapuram Palace. Thiruvananthapuram : Dept. of Archaeology.

- MARGLIN, F. A. (1985) Wives of The God-King : The Rituals of the Devadasis of Puri. New York : Oxford University Press.

- MARGLIN, F. A. (1990) “Refining the Body : Transformations of Emotion in Ritual Dance”. InDivine Passions : The Social Construction of Emotion in India. O. Lynch (Ed.), Berkeley : University of California Press : 212-236.

- MATEER, S. (1871) The Land of Charity : A Descriptive Account of Travancore and Its People, with Especial Reference to Missionary Labour. London : J. Snow & Co.

- MATEER, S. (1883) Native Life in Travancore. London : W.H. Allen & Co.

- MAYA, C., and MAHADEVAN, G. (2005) “Reporter’s Diary”. In The Hindu. Trivandrum (Thiruvananthapuram), Kerala.