Résumés

Summary

This study investigates the prevalence and impacts of employer resistance to union certification applications in eight Canadian jurisdictions. Employer resistance was found to be the norm, with 80 percent of employers overtly and actively opposing union certification applications. Analysis demonstrated that, depending on its form, employer opposition to union certification can impact upon both initial certification outcomes and on the probability the parties will establish and sustain a collective bargaining relationship. Furthermore, the study demonstrates that focusing only on the probability of certification success seriously underestimates the impact of employer opposition.

Résumé

Cet article s’appuie sur des données canadiennes pour tenter de combler la pénurie d’études empiriques sur l’ampleur de la résistance des employeurs face aux demandes d’accréditation syndicale. Il en évalue les conséquences non seulement sur l’accréditation initiale mais aussi suite à l’obtention du certificat d’accréditation. Il est important au Canada de jeter un coup d’oeil au-delà des taux de succès de l’accréditation et d’évaluer l’impact de la résistance d’un employeur sur la capacité des employés de se syndiquer, mais aussi d’enclencher et de maintenir avec succès des rapports de négociation collective. On croit que les systèmes canadiens d’accélération de l’accréditation, plus particulièrement ceux qui reposent sur la signature de cartes syndicales par une majorité, ont tendance à protéger le support de la majorité nécessaire à des fins d’accréditation contre les effets d’une opposition de la part d’un employeur. Cependant, dans le cas des systèmes à cartes, l’effet de l’opposition d’un employeur, même subtile, sur la solidarité et sur le support actuels ou sur leur érosion éventuelle peut faire tourner le succès d’une campagne de syndicalisation en une victoire à la Pyrrhus.

Les résultats de cette étude s’appuient sur une enquête effectuée auprès de 420 employeurs dans huit juridictions canadiennes où un certificat d’accréditation a été accordé par une commission de relations du travail appropriée entre 1991 et 1993 inclusivement. On a utilisé une technique statistique de régression pour apprécier les relations entre onze mesures des réactions des employeurs aux demandes d’accréditation et quatre mesures dichotomiques des conséquences : (1) le résultat initial d’une demande d’accréditation ; (2) la conclusion ou non d’une première convention collective ; (3) le fait ou non que des difficultés de négociation sont apparues tel qu’indiqué ou non par le recours à l’assistance d’une tierce partie, incluant la médiation, la conciliation ou l’arbitrage de la première convention ; (4) le fait que le syndicat a perdu ou non son accréditation à l’intérieur des deux premières périodes ouvertes de maraudage. On a fait appel à deux modèles d’évaluation : un qui utilise des variables fictives dans le cas d’un syndicat impliqué dans un processus d’accréditation; un deuxième qui utilise des variables propres à l’industrie. Cet échantillon montre que l’opposition à l’accréditation est la norme. Les réactions des employeurs sont variées; cependant, 88 % d’entre eux ont posé des gestes visant à rendre difficile l’accès du syndicat aux employés; 68 % ont entretenu des communications directes avec leurs employés pour s’opposer à l’accréditation; 29 % ont resserré les règlements d’atelier ou ils ont surveillé les employés; enfin, 12 % ont admis avoir eu recours à des pratiques déloyales au cours de la campagne de syndicalisation. Même en présence d’une liste extrêmement conservatrice de gestes que peuvent poser les employeurs sans être taxés d’opposition, les réponses qu’ont fourni 80 % d’entre eux dans l’échantillon pouvaient être sans se tromper de l’ordre d’une résistance de leur part. De plus, 20 % des employeurs ont été accusés ou ont admis avoir utilisé au moins une pratique syndicale déloyale.

L’analyse a démontré que, dépendamment de sa forme, l’opposition de l’employeur à la reconnaissance du syndicat peut avoir des conséquences sur une première accréditation et sur la probabilité que les parties réussissent à établir et à maintenir des rapports de négociation. Quelques gestes, par exemple la formation des dirigeants en vue d’affronter une campagne d’organisation syndicale, ont eu des effets désastreux sur la probabilité de succès d’une accréditation. Cependant, les comportements des employeurs pendant la campagne de syndicalisation ont produit leurs effets les plus dramatiques après l’accréditation. On en percevait les effets sur la conclusion de la convention collective et sur le maintien du certificat d’accréditation après les deux premières périodes de maraudage.

Cette étude ajoute du poids à ceux qui rejettent l’hypothèse voulant que des employeurs complaisants, qu’une législation protectrice et que des procédures d’accréditation accélérée protègent les syndicats canadiens des effets délétères de l’opposition des employeurs. Elle va plus loin que les recherches antérieures en démontrant que l’attention sur le résultat d’une première accréditation sous-estime largement l’impact de la résistance des employeurs, plus spécifiquement dans les systèmes d’accréditation accélérée. Pour être plus clair, le fait d’obtenir une ordonnance d’accréditation ne constitue qu’un pas vers les avantages et la protection de la syndicalisation. Quoique les systèmes accélérés vont probablement offrir une protection contre l’opposition d’un employeur qui interfère avec l’ordonnance initiale d’accréditation, leur protection est sérieusement minée si les gestes d’un employeur au cours de la campagne empêchent la conclusion d’une première convention collective ou contribuent à la désaccréditation hâtive du syndicat.

Resumen

Este estudio investiga la prevalencia y los impactos de la resistencia de los empleadores a las demandas de certificación sindical en ocho jurisdicciones canadienses. La resistencia de los empleadores aparece como la norma, con 80% de empleadores que se declaran abierta y activamente opuestos a las demandas de certificación sindical. El análisis demostró que, dependiendo de sus formas, la oposición de los empleadores a la certificación sindical puede tener impacto sobre el resultado inicial de certificación y sobre la probabilidad que las partes establezcan y mantengan una relación de negociación colectiva. De otro lado, el estudio demuestra que enfocar solamente la probabilidad de obtener la certificación lleva a subestimar gravemente el impacto de la oposición del empleador.

Corps de l’article

Much research effort has been directed toward the study of factors that give rise to both union growth generally and to the individual employee’s decision to join a union. Employer opposition to unionization is considered to impact negatively on both. A plethora of U.S. research studies have confirmed this assumption by analyzing the impact of employer resistance on employee voting behaviour and union certification success rates in National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) elections. With rare exception, every study has demonstrated a negative link between employer resistance and the establishment of unions’ representation rights. In fact, a consensus of studies cite increased levels of employer resistance and the failure of public policy to insulate employees from its impact as one of the most salient contributors to the precipitous decline of organized labour in the United States.

The interest in employer responses to union certification applications has, for the most part, not been shared by Canadian researchers. Accelerated certification procedures and restrictions on employer behaviour that are both more strict and more strictly enforced than in the United States were assumed to have so decreased the manifestations of employer opposition as to virtually obviate their negative impacts. However, recent evidence suggests the popular conception of Canadian employers as less willing to oppose unionization than their U.S. counterparts may be mistaken (Saporta and Lincoln 1995) and that employer resistance in Canada may not be as infrequent or as innocuous as assumed (Thomason 1994b; Riddell 2001). Furthermore, some evidence suggests that while the per-certification-application incidence of employer unfair labour practices has increased in the United States, so too have such practices increased in Canada, both absolutely and relatively (Bruce 1994). Finally, public policy amendments mandating certification votes in some Canadian jurisdictions[1] have decreased the differences between Canadian and U.S. certification procedures, making empirical analysis of employer resistance in Canada even more important.

This study uses Canadian data to address the dearth of empirical evidence on the prevalence of employer resistance to union certification and investigates its impact not only on initial certification outcomes but also on post-certification outcome measures. It is especially important in Canada to look beyond certification success rates and consider the impact of employer resistance on the ability of employees not only to become certified, but also to establish and sustain a collective bargaining relationship. Card majority systems measure union support at a point in time that often precedes any manifestations of employer opposition, perhaps even of employer knowledge of the organizing campaign. Likewise, most Canadian mandatory vote procedures set relatively strict and short time limits between the filing of a certification application and the vote. These accelerated certification systems, especially card majority procedures, are believed to insulate evidence of majority support from the effects of employer opposition. However, freezing the evidence in time does not prevent actual or subsequent erosion of union solidarity and support, and may make winning a certification campaign little more than a Pyrrhic victory (Bronfenbrenner 1994).

Thus, this study estimates the relationships between employer responses to union certification applications and: (1) initial certification success rates; and (2) other milestones on the road to establishing a stable collective bargaining relationship, the ability to negotiate a collective agreement and the ability to avoid early decertification. The remainder of this article begins with a literature review of the impact of employer opposition on both initial and post-certification outcomes as well as a review of the other factors known to affect certification outcomes. This is followed by a description of the data and methods of analysis and, finally, an examination of the results including both the incidence of employer opposition and the evidence regarding its impact on certification outcomes.

Literature Review

Impact of Employer Opposition on Certification Success

A multitude of mostly U.S. studies provide evidence of what employers have long assumed, that employer opposition to union certification can indeed impact upon certification outcomes, and that impact is almost invariably negative. With the exception of Getman, Goldberg and Herman’s (1976) study in which no statistically significant relationship was found,[2] virtually every study has demonstrated a negative link between employer resistance and the establishment of union representation rights. Only a handful of researchers have found the link between employer resistance and union certification success to sometimes be a positive one. Their results suggest that a large number of management-requested votes (Hunt and White 1985), a large number of unfair labour practices (Hunt and White 1985; Koeller 1992), intentional delay of the election through the use of appeals (Peterson, Lee and Finnegan 1992), discharging employees who are reinstated prior to the election (Bronfenbrenner 1994) and shifting work to other facilities (Peterson, Lee and Finnegan 1992) may, in some instances, cause a rebound effect and increase, as opposed to undermine, worker solidarity.

Research has predominantly focused on two measures of certification outcomes: the percentage of employees voting in favour of the union (see, for example, Dickens 1983; Seeber and Cooke 1983; Lawler and West 1985; Hunt and White 1985; Hurd and McElwain 1988; Bronfenbrenner 1994, 1997; Thomason 1994a, 1994b; Thomason and Pozzebon 1998) and/or the percentage of union election wins (see, for example, Drotning 1967; Prosten 1979; Roomkin and Block 1981; Seeber and Cooke 1983; Lawler 1984; Cooke 1985a; Reed 1989; Freeman and Kleiner 1990; Bronfenbrenner 1996, 2000; Bronfenbrenner and Juravich 1994; Riddell 2001). Some of the many employer responses that have been shown to negatively affect these certification outcome measures include: dismissing union organizers or supporters (Cooke 1985a; Bronfenbrenner 1994; Bronfenbrenner and Juravich 1998; Riddell 2001); being charged with an unfair labour practice (Hunt and White 1985; Koeller 1992; Thomason 1994a, 1994b; Riddell 2001); communicating anti-union sentiments directly to employees by means of letters, and/or one-on-one or captive-audience meetings (Drotning 1967; Dickens 1983; Bronfenbrenner 1994, 1996; Bronfenbrenner and Juravich 1998; Thomason and Pozzebon 1998); restricting union access to the workplace or supporters’ ability to engage in workplace solicitations (Lawler 1990); monitoring employees (Bronfenbrenner 1996); hiring consultants to assist in the employer’s campaign (Lawler 1984; Freeman and Kleiner 1990; Bronfenbrenner 1994; Thomason and Pozzebon 1998; Bronfenbrenner and Juravich 1998); training managers to take action against the organizing campaign (Reed 1989; Freeman and Kleiner 1990; Thomason and Pozzebon 1998); threatening to close the plant or spreading rumours that this will happen (Bronfenbrenner 1996, 2000; Peterson, Lee and Finnegan 1992); promising increased pay or benefits if the union is defeated (Bronfenbrenner 1994; Bronfenbrenner and Juravich 1994); using administrative means, such as filing objections or requesting postponements to delay the certification vote (Roomkin and Block 1981; Cooke 1985a; Thomason 1994a; Prosten 1979; Hunt and White 1985; Hurd and McElwain 1988); or using some combination of tactics (Dickens 1983; Lawler and West 1985; Freeman and Kleiner 1990; Thomason 1994b; Bronfenbrenner 1994; Bronfenbrenner and Juravich 1998; Thomason and Pozzebon 1998).

Thomason (1994a) was one of the first to use Canadian data to estimate the effect of employer unfair labour practices on the proportion of employees voting in favour of the union and on the probability of certification. He concluded that the negative effect of employer resistance on employee support for unionization in Ontario was “relatively slight, particularly when compared to the impact of such practices in the United States” (1994a: 224). In a subsequent study (1994b), after controlling for differences in wages and working conditions, and for endogeneity between employer resistance and the probability of certification, Thomason amended his findings. He noted that both employer unfair labour practices and an index of other indicators of employer resistance tactics were significantly negatively related to the proportion of employees supporting the union and to the probability of certification. Rather than the one to two percent reduction calculated in his earlier study, he estimated employer unfair labour practices in Ontario and Quebec reduced the probability of certification by 8 to 13 percent (1994b), a figure much closer to the 17 percent reduction estimated by the most comparable U.S. study (Cooke 1985a). Another Canadian study focused on the impact of employer suppression on union organizing success within a mandatory vote regime by analyzing certification-related unfair labour practices in British Columbia private-sector organizing campaigns in 1987 and 1988. Results provide new evidence that where Canadian certification procedures resemble those in the U.S., unfair labour practices can have comparably detrimental effects, reducing union win rates generally by 21 percent and by an even greater measure in certain industries (Riddell 2001).

Several U.S. and Canadian studies also provide evidence of post-certification impacts of employer actions during a certification drive. For example, employer unfair labour practices (Forrest 1989; Solomon 1985), plant closure threats (Bronfenbrenner 1996), or discrimination against union activists (Cooke 1985b) during the election campaign substantially decrease the probability a first contract will be reached. Even if employer resistance tactics have not been effective in foiling employees’ efforts to become unionized and negotiate a first agreement, the opposition may so effectively undermine worker solidarity as to threaten the long-term viability of collective representation and precipitate decertification.

Other Influences on Certification Success

Factors not necessarily related to employer responses also play an important role in determining certification outcomes. Delay between the initial filing of the application for certification and its resolution detrimentally affects certification success (Prosten 1979; Roomkin and Block 1981; Roomkin and Juris 1979; Scott, Simpson and Oswald 1993; Thomason 1994a). While some delays are due to unavoidable hold-ups, delay is often the result of employer stalling tactics. Certainly U.S. employers are cognizant that delaying the certification vote affords greater opportunity to dissuade employees from supporting the union. Thomason (1994a) pointed out that increased employer resistance associated with certification votes may not only be a function of opportunity but also of greater expected payoff. The expected effectiveness of resistance is far greater when incremental changes in union support can affect the certification outcome (see also Koeller 1992). In Canadian jurisdictions where certification is granted based upon membership card evidence, certification votes are, by definition, close contests since they are only held where the union is able to assemble an initial threshold level of support but not a clear majority. Thus, we would expect delay, and other factors that increase uncertainty such as holding a vote or a hearing, to be associated with more employer resistance and lower certification success rates.

One of the most important factors to impact upon certification success is the size of the bargaining unit. Partially due to the difficulty associated with communicating with and balancing the interests of large, diverse groups of employees, there is a negative relationship between bargaining unit size and certification success (Scott, Simpson and Oswald 1993; Thomason 1994a; Lawler 1982; Cooke 1983). Similarly, unions face greater difficulty in organizing employees of a large firm (Scott, Simpson and Oswald 1993; Thomason 1994a). While employees in large firms may feel greater alienation and less loyalty, large firms seem better able to either mount campaigns to oppose organizing efforts or to implement human resource policies to address employees’ needs and thereby decrease their motivation to unionize (Maranto and Fiorito 1987).

Union density has often been assumed to be an indicator of public support for unionism and positively associated with certification success (Seeber and Cooke 1983; Hurd and McElwain 1988). However, some studies have found union density to be negatively related to certification success rates (Cooke 1983; Scott, Simpson and Oswald 1993), a phenomenon that may be attributable to union saturation and little remaining unfilled demand for unionization. Just as union density is assumed to be an indicator of a community’s favourable disposition toward unionism, the presence of at least some unionized workers in a firm may indicate the organization is not vehemently opposed to unionization and may serve to demonstrate the benefits of unionism to non-union employees. Indeed, established unionization within the firm has been shown to be positively associated with the probability of certification success (Delaney 1981; Rose 1972; Bronfenbrenner and Juravich 1994, 1998), as has the presence of more than one union vying for employees’ support (Scott, Simpson and Oswald 1993).

Other factors such as the particular union involved, and the occupation or mix of occupations included in the bargaining unit have also been shown to impact upon the success of certification applications. One study found independent locals engendered greater support from employees (Thomason 1994a). Another found Employee Associations to have greater certification success (Delaney 1981), while others found specific unions to have lower success rates (Sandver 1980; Scott, Simpson and Oswald 1993). A study using Canadian data found heterogeneous bargaining units containing a mix of occupations had greater success in elections determined by pre-hearing votes but that units composed solely of office workers came out ahead in certifications determined by membership card evidence (Thomason 1994a). Bargaining units in different industries will have varying degrees of homogeneity and will be composed of different types of workers, perhaps with different attitudes toward unionization, and these will influence certification success (Riddell 2001). Finally, a large body of research exists that examines the influence of the tactics used by, and characteristics of, union organizers. However, examination of these factors is beyond the scope of this study and a survey of employers is of questionable validity for collection of data regarding union organizing tactics or characteristics of union organizers.

Post-Certification Outcomes

As discussed earlier, it is important to look beyond initial election outcomes and consider whether the union is able, after becoming certified, to conclude a first collective agreement and sustain a collective bargaining relationship with the employer. Many of the same factors that impact upon certification success rates also influence the likelihood the union and employer will conclude a first collective agreement. For example, delay between the initial certification application and its disposition impacts negatively not just on certification but may also decrease the probability of negotiating a first collective agreement (Cooke 1985b). Paradoxically, while large bargaining units are less likely to win certification, they are more likely to successfully negotiate first contracts and establish stable labour relations (Cooke 1985b; Pavy 1994). Other factors, such as the availability of first contract arbitration, have little or no influence on initial certification success but increase the likelihood of sustained certification success by increasing the probability parties will establish a first agreement (Macdonald 1987; Sexton 1987).

Establishing a collective bargaining relationship by becoming certified and concluding a first contract are but first steps for a union. In order to sustain the relationship, the union must avoid early decertification that may result if employer resistance erodes employee support or undermines the union’s ability to effectively represent employees. While employer resistance may contribute to early decertification, some research suggests that decertification activity is primarily explained by market conditions (Lawler and Hundley 1983; Ahlburg and Dworkin 1984). Other studies, however, have shown that union characteristics and actions, and bargaining unit characteristics were better predictors of decertification activity than models based upon economic indicators (Anderson, Busman and O’Reilley III 1982). Other studies attribute decertification activity to both union actions, such as shifting resources from servicing units to organizing new ones, and to changing economic conditions beyond the control of the union (Elliott and Hawkins 1982). One study (Meyer and Bain 1994) favoured a model that combined economic and bargaining-unit specific measures and found the most important factors influencing the outcome of decertification elections to include: (1) the union involved; (2) local employment opportunities; and (3) the size and type of bargaining unit.

Independent locals were more likely to lose employee support than were nationally affiliated unions, which typically have greater available resources. Where the firm’s compensation package was below the local labour market average or where local alternative employment opportunities were increasing, decertification was also more likely. Other research, however, has found shrinking employment opportunities, as measured by the national unemployment rate, to be positively related to decertification activity, perhaps due to union members’ perceptions that their union is not protecting their interests (Anderson, O’Reilley III and Busman 1980). Finally, unions were more likely to lose support in smaller bargaining units (Anderson, Busman and O’Reilley III 1982; Meyer and Bain 1994). Controlling for these factors known to affect decertification activity, this study will seek evidence of a relationship between employer actions during certification campaigns and early decertification. For the purposes of this study, early decertification is defined as within the first two open periods, the two or three month periods preceding the anniversary of certification or the expiry of a collective agreement and during which decertification or new certification applications may be submitted.[3]

Overview of Previous Research

The literature review outlined many factors that influence the probability of certification success, including delay, size of the bargaining unit, firm size, union density, established unionization within the firm, whether more than one union is vying for employees’ support as would be the case in a raid, occupational mix in the unit, industry in which the employer operates, the particular union involved, and uncertainty of the certification outcome including whether a vote or a hearing is held. Certification policy variables such as whether card majority certification is available and whether the labour relations board has authority to impose certification in cases where egregious employer misconduct has made discerning employees’ true wishes unlikely may also influence organizing success. Post-certification outcomes are affected by many of the factors mentioned above as well as by the availability of first-contract arbitration, the firm’s relative compensation, and unemployment rates. Employer opposition to unionization is known to affect both the probability of certification success and whether a first collective agreement will be concluded. This study hypothesizes that employer opposition also influences other post-certification outcomes such as whether bargaining difficulties are encountered during first-contract negotiations and whether the certification is effectively reversed through early decertification.

Employer responses that detrimentally affect initial certification success, and most likely post-certification outcomes as well, include: communicating anti-union sentiments directly to employees; limiting communication between union organizers and employees; dismissing union organizers or supporters; threatening to close the plant or contract out work; promising increased pay and benefits if the union is defeated; committing and being charged with an unfair labour practice; using administrative means such as postponements, appeals or objections; training managers to deal with the organizing campaign, and engaging lawyers or consultants to assist in the employer’s campaign. In some instances, some of the above employer tactics used repeatedly, as well as a few other tactics, may produce a rebound effect and result in less favourable outcomes for the employer. This study reports on the incidence of a variety of employer responses and on the impacts of those responses not only on initial certification, which may be somewhat insulated from employer resistance due to accelerated certification systems, but also on post-certification outcomes, which may more accurately reflect the true impact of employers’ actions during union organizing campaigns.

Data and Methods

Data were obtained from questionnaires mailed to employers in a stratified, cross-sectional research design that included eight Canadian labour relations jurisdictions.[4] The unit of analysis was the individual certification application concerning one employer and one union. Temporal limits were selected in order to make data collection feasible, to ensure sufficient time for parties to either succeed or fail to conclude a collective agreement, and to allow two open periods to pass.[5] Sectorial and jurisdictional limits were imposed by limiting the study to cases processed by provincial labour relations boards. This limitation made data collection feasible and allowed inclusion of a variety of employers in a variety of industries, including some para-public sector employers, such as those in education and health-care, and municipalities.

The sample was stratified by labour relations board and sampled non-proportionally in order to decrease sampling error and to decrease costs while still ensuring an adequate number of cases from each jurisdiction. Thus, sample frames consisted of a separate list for each province. Each list consisted of all certification applications processed by that province’s labour relations board during the calendar years 1991, 1992, and 1993 regardless of whether the application was allowed, denied or withdrawn. Four hundred and twenty completed surveys were returned with fairly consistent response rates across provinces, from a high of 32 percent in Saskatchewan to a low of 22 percent in Alberta, Manitoba and Newfoundland.[6] The achieved sample is very similar to the population with respect to the proportion of non-respondents and respondents from each of the study years, and from each province. However, there does appear to be some response bias with respect to outcome measures: the sample includes a higher proportion of successful certifications and a lower proportion of unsuccessful or withdrawn applications than in the population. Although the response bias is minimal and not unexpected,[7] it should be kept in mind when considering results. Organizing drives that did not result in certification, either through no fault of the employer or due to employer resistance, are more common in the population than in the achieved sample. Furthermore, the indicators of employer resistance used in this study were measured using information provided by questionnaire respondents whose memories may have been clouded or distorted by intervening events and the passage of time. Since this information reflects only respondents’ recollection and admission of employer actions, it most likely understates the number and types of tactics in which employers engaged.

Measures of Employer Responses and Certification Outcomes

Based upon employer activities characterized as employer resistance in previous studies, a list of employer responses was developed and respondents were asked to indicate whether or not they had engaged in these activities. Exploratory factor analysis, using principal component analysis as the extraction method, was used to distil three patterns of employer behaviour in response to union certification applications: (1) actions that interfere with the union’s ability to communicate with employees or with employees’ communications amongst themselves; (2) direct communication with employees regarding the union certification application; and (3) tightening work rules or monitoring employees. Since so few respondents admitted to behaviours that are commonly recognized as unfair labour practices, a dummy-coded variable was created to indicate the admission of one or more of the following behaviours: promising increased pay and benefits if the union was defeated; threatening to relocate or contract-out if the union was certified; transferring union activists; dismissing or laying off employees in response to the organizing drive; or any other action described by respondents that, in the author’s opinion, would constitute an unfair labour practice.

The remaining seven indicators of employers’ responses are dummy coded variables: (1) administrative challenges and delays such as postponements, objections or appeals of board decisions; (2) objection(s) to the bargaining unit that were granted;[8] (3) objection(s) to the bargaining unit that were denied or partially denied; (4) training managers to deal with an organizing drive; (5) hiring a lawyer; (6) hiring a consultant and (7) whether unfair labour practice charge(s) were filed against the employer. Several of the above measures may or may not be indicators of employer resistance since management’s motives are unclear. Employers may engage lawyers to assist them in battling the union or they may simply need information about the certification process and their rights and responsibilities; consultants may be hired for the understood, albeit surreptitious, purpose of defeating the union or, alternately, to provide guidance and advice during the certification process and subsequent contract negotiations. Thus, measures should be thought of more as employer responses than gauges of resistance or opposition; patterns or combinations of responses provide more definitive classification of employer responses.

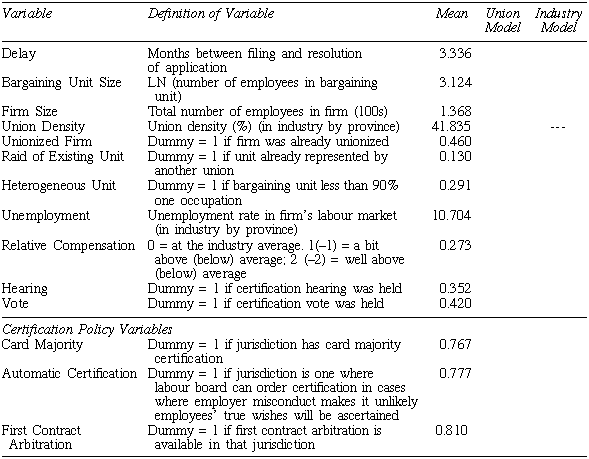

Utilizing logistic regression, measures of employer responses and a vector of control variables were regressed against four dichotomous outcome measures: (1) initial outcome of the certification application; (2) whether a first collective agreement was concluded; (3) whether bargaining difficulties were encountered as indicated by whether third-party assistance, including mediation, conciliation or first-agreement arbitration, was required; and (4) whether the union was decertified within the first two open periods following certification. Two estimation models were utilized, one that included dummy variables for the union involved in the certification application and a model including industry variables. Union dummies and the union density variable were excluded from the industry model due to multicollinearity. A third model incorporating provincial dummy variables is not reported but produced no appreciably different results. Definitions and weighted means of control variables are reported in Table 1.

This research was undertaken in conjunction with a study of the determinants of employer resistance and an attempt was made to utilize a two-stage estimation procedure, substituting estimated values of employer responses for actual measures. This served to control for the endogenous relationship found by Freeman and Kleiner (1990) to exist in the United States between the percentage of employees who signed union authorization cards and employers’ propensity to engage in resistance tactics. Unfortunately, the two-stage estimation procedure produced questionable and unexpected results, likely due to problems in the model of determinants of employer resistance including incomplete specification and multicollinearity. Theoretically, however, it is hard to argue that, in Canada, employers calculate the intensity of their response based upon an objective measure of employee support for unionization. Information regarding the level of employee support demonstrated by unions tendering membership card evidence is not made public in Canada other than indirectly by the Board either ordering a vote or certifying the union. Thus, unlike employers in the United States, Canadian employers may not factor objective measures of employee support for unionization into their response decisions. Instead, employers may either base their decision upon a subjective reading of employee sentiment or simply assume their actions have the capacity to influence certification outcomes. Thus, this research does not assume that Freeman and Kleiner’s findings should be extrapolated and presumed to apply to Canadian employers functioning within different public policy contexts. While it could be argued that failing to control for the endogeneity of employer resistance may understate its impact on certification outcomes, this bias is less likely to be present for Canadian than U.S. data and, if it is present, is likely to be of much smaller magnitude.

Table 1

Definitions and Weighted Means of Control Variables

Results

Incidence of Employer Responses

In this sample, overt opposition to union certification was the norm. Employer responses were varied but fully 88 percent engaged in actions to limit employees’ ability to communicate amongst themselves or with union representatives and 68 percent communicated directly with employees regarding the certification application, with the most popular method of communication being captive audience speeches. Just less than a third of employers tightened work rules or monitored employees, and 12 percent admitted to unfair labour practices during the organizing drive. Frequencies and percentages for all employer responses are reported in Table 2.

Even when characterizing employers using an extremely lenient list of actions in which employers could engage and still not be considered to have opposed unionization, only 20 percent of employers did not oppose the certification applications. These employers admitted to none, some, or all of the following actions: (1) hiring a lawyer; (2) hiring a consultant; (3) training managers to deal effectively with the organizing drive; (4) filing an objection to the proposed bargaining unit, regardless of its outcome; (5) engaging in actions to limit employees’ ability to communicate amongst themselves or with union representatives. Fully 80 percent of employers in the sample admitted to actions that unmistakably evince open opposition to union certification.[9] Sixty percent admitted to any or all of the above-listed actions but also to engaging in one or more of the following actions more commonly recognized as active resistance tactics: (1) discussing the application directly with employees one on one, in captive-audience speeches, or through written communications; (2) utilizing administrative challenges and delays such as postponements, objections or appeals of board decisions; (3) tightening work rules or monitoring employees. Twenty percent of employers not only engaged in some or all of the responses listed thus far, but also admitted to either being charged with an unfair labour practice and/or engaging in other actions commonly recognized as unfair labour practices such as threatening to contract out or relocate if unionized, transferring or dismissing union supporters, or promising increased pay and benefits if the certification application was defeated.

Table 2

Employer Responses to Union Certification Applications

Percentages are of those who responded to that question or group of questions.

Thomason and Pozzebon (1998).

Defined by Thomason and Pozzebon as “threats against union supporters.”

These characterizations along a scale of increasing and more egregious forms of opposition, although somewhat sensitive to definition,[10] indicate that the vast majority of Canadian employers respond to union certification applications with some degree of overt defiance. The figures are astounding given the extremely generous definition of non-resistance and a response bias that suggests this sample under-represents employers whose opposition efforts were successful in defeating certification. Furthermore, sample data capture employers’ admissions of actions and, given the sensitive nature of these admissions, likely understate employer resistance, especially those actions that may be illegal or not publicly sanctioned.

This sample’s understating of employer resistance is apparent when considering the rate of unfair labour practice charges associated with certification applications in the sample: 10.2 percent, as compared to other Canadian samples that found the incidence of certification-related unfair labour practice charges to be no less than 11.6 percent (Forrest 1989) and more likely in the 16 to 19 percent range (Thomason 1994b; Solomon 1985). The degree to which employers in this sample under-report obstructive forms of resistance becomes even more apparent when one compares the percentage of respondents in this sample who admitted to certain actions to the incidence of these tactics reported in a study based upon a survey of union organizers in Ontario and Quebec (Thomason and Pozzebon 1998) and reported in Table 2. The results of this study conform quite closely with Thomason and Pozzebon’s results when considering less obstructive forms of resistance such as: (1) training managers; (2) hiring a consultant; (3) discussing the application with employees;[11] (4) holding captive-audience meetings; and (5) sending letters or memos to employees.[12] However, when more obstructive tactics, such as tightening work rules, monitoring employees,[13] and making inappropriate threats[14] or promises are considered, Thomason and Pozzebon’s results imply that obstructive forms of employer resistance are far more common than the results of this sample would suggest.

While the data likely understate the more egregious forms of employer resistance, they clearly document the propensity of Canadian employers to actively oppose union certification. What the data do not capture are employer actions outside the boundaries of the organizing drive, those designed to avoid a certification application, or to destabilize the union once it is certified. Further, the sample data do not capture the actions of employers who quashed the organizing drive in its early stages, prior to the union filing a certification application.

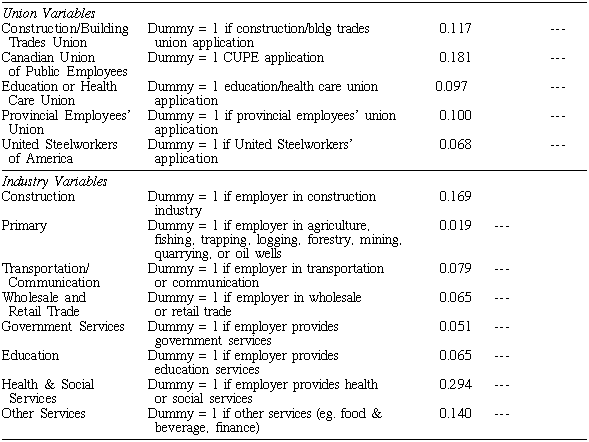

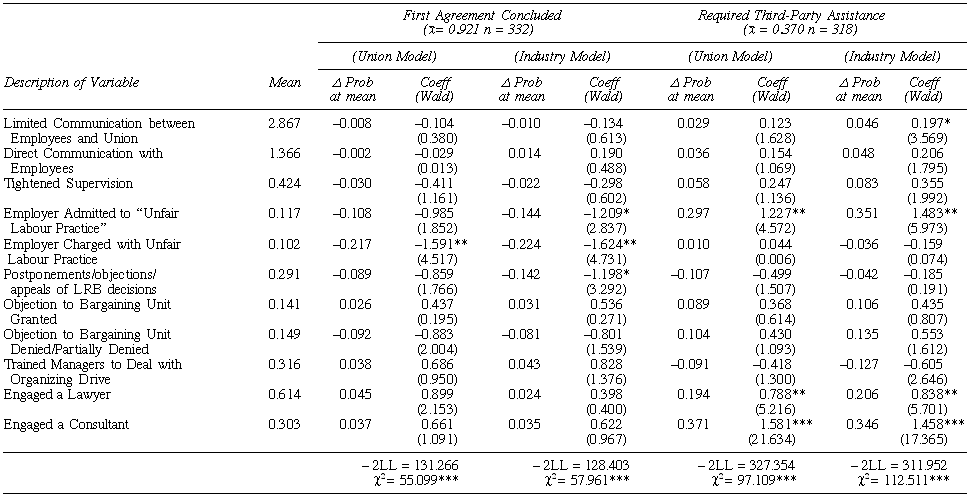

Impacts of Employer Responses

Results for the impact of employer responses on the probability of certification or early decertification are presented in Table 3. Estimates of the impacts of employer responses on negotiation of a first collective agreement, including whether one was concluded and whether the parties encountered sufficient difficulties to require the assistance of a third party, are presented in Table 4. The two estimation models demonstrate consistent results but none of the employer responses has consistent, statistically significant, detrimental effects on all certification outcomes. This lack of consistency may be due to this study’s focus on individual employer actions, which previous research (Lawler 1990) suggests have less impact than the overall employer campaign and the synergies between tactics. While data limitations prohibited an analysis of interactions between tactics, future Canadian research should focus on this. Furthermore, this sample’s understating of certain tactics, such as those that likely constitute unfair labour practices, contributes to the lack of significance or low significance levels of some results.

The employer tactic of monitoring employees, which may also include tightening supervision or work rules, demonstrates the most consistent, significant effect, although that effect is unexpected. Rather than decreasing the probability of certification, this employer tactic demonstrates a long-lasting rebound effect that not only increases the likelihood of certification success by approximately 8 percentage points at the mean but also decreases the likelihood of early decertification by as much as 20 percentage points. This result replicates the paradoxical effect of employer resistance occasionally found by other researchers that certain types of resistance may bolster, rather than undermine, worker solidarity and suggests this effect is sustained well past initial certification. In this instance, the effect may be due to this tactic’s pervasive and unwelcome intrusion into virtually all employees’ day-to-day work lives.

Table 3

Probability of Certification and of Early Decertification: Selected Coefficients and Changes in Probabilities from Logistic Regressions

Significant at the 0.10 level

at the 0.05 level

at the 0.01 level (two-tailed tests).

Early Decertification defined as: Bargaining unit decertified within first two open periods.

Estimated coefficients were converted to changes in probabilities associated with a one-unit change in each explanatory variable at the mean of the dependent variable. The change in probability of a certification outcome emanating from a one-unit change in continuous or categorical explanatory variables was calculated by applying the following formula: ∂P/∂P = P(1–P)b. Large discrete changes such as those associated with a change in a dichotomous independent variable, require the incorporation of the discrete change into the logistic function. Thus, the change in the probability of a certification outcome emanating from discrete changes associated with dichotomous independent variables was calculated using the following formula: ∆Pi = [ 1 + exp {–ln (P/(1–P)) – bi}] –1 – P.

Table 4

Probability of Concluding a First Collective Agreement and of Requiring Third-Party Assistance: Selected Coefficients and Changes in Probabilities from Logistic Regressions

Significant at the 0.10 level

at the 0.05 level

at the 0.01 level (two-tailed tests).

Required Third-Party Assistance defined as: Mediation, conciliation or first-contract arbitration required to conclude first agreement.

Another measure that increases the chance of certification success is really an indicator that the definition of the bargaining unit was not altered by presumably vexatious employer objections. Bronfenbrenner (1994) and Bronfenbrenner and Juravich (1998) found that if the ultimate bargaining unit was defined differently than the one petitioned for, the probability of a union win decreased by 15 or 16 percentage points. In this sample, where labour relations boards thwarted employer attempts to make inappropriate changes to the bargaining unit, the probability of a union win increased by 13 percentage points. It may also be that causation runs in the opposite direction: where the perceived likelihood of certification success is high, employers may resort to objections to the bargaining unit in an attempt to limit union encroachment. Employer bargaining unit objections that were granted had no significant effect on certification success but decreased the probability of early decertification by 8 percentage points. Although this result is only statistically significant in the union model and even then the significance level is low, it may suggest that exclusions of managerial or other employees who, in the view of the labour relations board, should legitimately be excluded, result in units that unions can more effectively represent and sustain. While collinearity between individual industry variables and the variable representing objections to the bargaining unit that were granted is not a problem, the latter is correlated with the industry variables as a group, which may account for the lack of significance of this result in the industry model.

Two employer responses, training managers to deal effectively with the organizing drive and limiting communication between the union and employees, demonstrate statistically significant negative effects on the probability of certification success. Ironically, the employer response with the largest negative influence is one that may be interpreted as indicative of resistance or as simply a rational response to changing circumstances and, in fact, is included in the list of activities in which employers can engage and still be considered to not have resisted unionization; in this sample, training managers to deal “effectively” with the organizing drive decreased the probability of certification by 15 to 16 percentage points. These results support Freeman and Kleiner’s (1990) conclusion, based on U.S. data, that supervisory action is the most effective employer tactic to deter unionization but contradict Thomason and Pozzebon’s (1998) finding that, in Ontario and Quebec, training managers is among the least effective resistance tactics. Tactics that make it more difficult for employees to meet or communicate with each other and their union also reduce the probability of certification success, albeit in smaller increments of approximately three percentage points per tactic. Nonetheless, a consistent employer approach consisting of four or five barriers designed to hinder employees’ ability to spread the word about the organizing campaign could potentially decrease the probability of certification by as much as 14 percentage points.

Some employer responses that show no evidence of statistically significant effects on initial certification success are associated with poorer long-term certification outcomes. If, during the organizing drive, the employer engaged in actions commonly recognized as unfair labour practices, the probability of concluding a collective agreement decreased in the industry model by 14 percentage points, the likelihood of encountering serious bargaining difficulties increased in both models by 30 to 35 percentage points and early decertification increased by an amazing 46 to 57 percentage points, increasing the probability of early decertification from the mean of height percent to as high as 65 percent. It is quite possible that this and other measures of employer responses act as proxies for employer willingness to engage in aggressive opposition to unionization, opposition that likely continues well past initial certification. It is these employer responses that have all too often been discounted as negated by Canada’s accelerated certification processes. Even the seemingly innocuous act of hiring a lawyer may, in some instances, signal an employer’s willingness to engage in a resistance campaign that perhaps remains within the bounds of legality and even accepts initial certification as almost inevitable, yet considers continued unionization avoidable. In this sample, hiring a lawyer increased the likelihood of encountering bargaining difficulties and requiring third-party assistance by 19 to 21 percentage points and increased the probability of early decertification by 29 percentage points, although this latter result is only significant in the industry model. Again, collinearity between variables of interest and groups of dummy control variables appears to influence the magnitude of coefficients and the significance of results. The union variables, as a group, are more collinear with hiring a lawyer than are the industry dummies as a group, perhaps accounting for the lack of significance in the union model. Similarly, the variable representing employer admissions of unfair labour practices correlates with both groups of dummy variables, albeit more strongly and significantly with the group of variables included in the union model.

While hiring a consultant is associated with an even greater increase in the likelihood of requiring third-party assistance than hiring a lawyer, it decreases the probability of early decertification by seven or eight percentage points. This supports the perception that consultants play a very different role in Canada than in the United States and that a Canadian employer is more likely to engage a lawyer when launching a legal challenge to unionization and to turn to a consultant for industrial relations expertise or bargaining assistance. Rather than contributing to bargaining difficulties, consultants may be hired in reaction to such problems.

The only employer response that demonstrates a consistent, statistically significant relationship with the probability of concluding a first collective agreement is employer unfair labour practice charges. This negative relationship has been documented many times (Reed 1993; Cooke 1985b; Solomon 1985; Forrest 1989) and is supported by these data, which suggest that an unfair labour practice charge is associated with a 22 percentage point decrease in the probability of concluding a first collective agreement. Rather than a greater than nine out of 10 likelihood of concluding a collective agreement, the chances decrease to only slightly better than two out of three. Results from the industry model suggest that administrative challenges or delays and employer actions commonly recognized as unfair labour practices may also be associated with a slight decrease in the probability of concluding a first collective agreement. The low significance levels for these latter results and the lack of significance of any of the other coefficients may be partially due to the lack of variation in the dependent variable. In the cases where unions achieved certification, over 92 percent concluded a collective agreement, leaving only 27 (weighted) cases without a first agreement.

Control variables behaved consistently and as expected in both models, although not always displaying statistical significance where predicted. Complete results are not presented here but are available from the author upon request. Interestingly, strong statistically significant relationships were found between certification outcome measures and two control variables that may be symptomatic of employer opposition: the requirement for a hearing and the holding of a vote. A certification hearing was associated with a 17 to 19 percentage point reduction in the probability of certification success and an 18 percentage point increase in the likelihood of early decertification.[15] The latter result was only significant in the industry model likely due to a combination of low variation in the dependent variable and slight collinearity between holding a hearing and the dummies included in the union model. Even when controlling for the certification process applicable in each jurisdiction, the probability of early decertification increased by as much as 41 percentage points if a certification vote was required.[16] In fact, of the 29 instances where early decertification occurred, a certification vote had been held in 65 percent of the cases.

Summary and Conclusions

Overall, this study demonstrates that employer opposition to union certification is neither as infrequent nor as innocuous in Canada as has often been assumed. The vast majority of employers included in this study engaged in actions that can only be characterized as overt and active resistance. A few actions, such as training managers to deal with the organizing campaign, had quite detrimental effects on the probability of certification success. However, employers’ actions during the organizing campaign had their most dramatic effects on post-certification outcome measures. For example, this study provides further evidence of the negative relationship between employer unfair labour practice charges and the likelihood of concluding a first collective agreement, even though it provides no evidence of detrimental effects of such charges on initial certification outcomes. Results also suggest that employer actions commonly recognized as unfair labour practices, such as dismissing or transferring union activists or issuing inappropriate threats or promises, have extremely detrimental effects on the negotiation of a first contract and the continued existence of a certification order even though they do not appear to affect its initial issuance. Thus, the employer responses generally considered, and characterized in this study, as the most obstructive forms of resistance had no discernible effect on the likelihood of certification success. Their effects were only seen when considering other post-certification outcomes such as whether a collective agreement was concluded and whether the certification continued to exist past the first two open periods.

Future research should address the limitations of, and extend, this study. For example, this and other studies based on self-reported data are subject to problems of bias and recall. The latter is particularly problematic in this study. Furthermore, dichotomous measures of employer tactics are crude and should, in future, be refined to measure not only the extent to which certain tactics are used but also combinations, patterns, and interactions of tactics. It is also important to discern whether employer actions during the organizing campaign erode employee support for unionization or cause other changes that result in later difficulties or whether such actions are simply proxies for continued, post-certification employer opposition. Future studies should strive to incorporate all Canadian jurisdictions and to utilize instrumental variable analysis as evidence suggests that simple regression models, whether ordinary least squares, probit, or logistic (Thomason 1994b; Riddell 2001) seriously underestimate the impact of employer opposition.

This study adds volume to the voices objecting to the assumption that compliant employers, protective legislation, and accelerated certification procedures insulate Canadian unions from the deleterious effects of employer opposition. It goes further than previous research by demonstrating that a focus on the initial certification outcome vastly understates the impact of employer opposition and suggesting this is especially the case with accelerated certification systems. Clearly, being granted a certification order is but one step toward gaining the protections and advantages of collective representation. While accelerated certification systems may indeed offer some protection from employer opposition interfering with employees’ attempts to initially become unionized, their protections are seriously undermined if employer actions during the organizing campaign can prevent the establishment of a first collective agreement or contribute to the union’s early decertification.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

During the study years, 1991 to 1993, Nova Scotia, Alberta, and until January, 1993, British Columbia, mandated certification votes. Since then, Ontario implemented mandatory vote procedures (1995) and such procedures were in place in Manitoba from 1996 to 2000.

-

[2]

Getman, Goldberg and Herman’s conclusions, or lack thereof, are countered by Dickens’ (1983) study that utilized the same data yet found a significant negative relationship between employer resistance activities during union election campaigns and workers’ support for unionization.

-

[3]

In order to provide some stability for collective bargaining relationships, all Canadian jurisdictions place time limits on certification and decertification applications. The most important of these limits is the “collective agreement bar” which usually provides that applications may only be made during the last two or three months of the term of a collective agreement. Where an agreement is not in place, the period during which applications may be made is usually a 60 or 90 day window of opportunity six to twelve months after the date of the original certification application. If employer resistance undermines support for the union, an application for decertification may be filed during one of these “open periods.”

-

[4]

Prince Edward Island was dropped due to the extremely low number of cases during the relevant years (12) and the difficulties associated with obtaining information concerning those cases. The federal jurisdiction was dropped as information available from the Canada Labour Relations Board was so limited that the job of contacting an adequate number of employers was prohibitively expensive and time-consuming. It was with sincere regret that the decision to exclude Quebec was taken. However, the budget for this project was tightly constrained and it was determined that to allocate dollars to translation would have required decreasing the sample size to such a degree as to potentially compromise project results.

-

[5]

Surveys were mailed out in late 1996 and early 1997.

-

[6]

The overall response rate of 25% is relatively low but understandable given the fact that no letter or phone call preceded receipt of the questionnaire and the questionnaires were not addressed to a specific person within the employer’s organization but rather to a position title such as Manager/Director of Human Resources. Furthermore, many employers may have considered the survey to be of little relevance given both the subject matter and the protracted time lag between the union organizing drive and receipt of the questionnaire. Finally, survey questions addressed sensitive subject matter and, in some instances, requested employers to admit engaging in illegal actions.

-

[7]

Applications resulted in certification for approximately 82% of respondents, as compared to 70% of the population and only 64% of non-respondents. Certification applications were denied or dismissed 14% of the time in the population but only 11% of respondents reported that outcome. The greatest discrepancy between population characteristics and the characteristics of respondents is the proportion of certification applications withdrawn: 17% and 6% respectively. The fact that employers were more likely to respond if an organizing drive resulted in the certification of a union is not unexpected. Several years after the fact the perceived relevance of a questionnaire is likely to be lower and the memories of the event faintest if the union was never certified. Least likely to be remembered in detail or considered worthy of investing the time to complete a questionnaire would be certification applications withdrawn before formal proceedings began.

-

[8]

This variable indicates the labour relations board granted the exclusion and assumes this differentiates the objection from a vexatious one contrived to frustrate unionization.

-

[9]

The categorization system used here loosely draws upon Lawler’s (1990) Unionization/Deunionization model and his characterization of employer strategies during the campaign phase of unionization.

-

[10]

Although the characterization of acceptance already provides employers great latitude, adding other debatably neutral responses to the list of actions in which employers can engage and still not be considered to have resisted unionization changes the percentages only slightly. For example, moving administrative challenges and delays from the list of active resistance tactics to the list of tactics indicating acceptance, still suggests that 74 percent of employers in this sample engaged in unmistakably blatant opposition.

-

[11]

Defined as “small group meetings” by Thomason and Pozzebon.

-

[12]

Defined as “anti-union literature” by Thomason and Pozzebon.

-

[13]

Defined as “surveillance of employees” by Thomason and Pozzebon.

-

[14]

Defined as “threats against union supporters” by Thomason and Pozzebon.

-

[15]

Results for Hearing in certification estimates: Coeff. = –0.947***, Wald Stat = 6.796 (union model); Coeff. = –1.044***, Wald Stat = 8.402 (industry model). Results for Hearing in early decertification estimates: Coeff. = 1.387*, Wald Stat = 2.968 (industry model).

-

[16]

Results for Vote in early decertification estimates: Coeff. = 2.217***, Wald Stat = 10.093 (union model); Coeff. = 2.358***, Wald Stat = 8.954 (industry model)

References

- Ahlburg, Dennis A. and James B. Dworkin. 1984. “The Influence of Macroeconomic Variables on the Probability of Union Decertification.” Journal of Labor Research, Vol. V, No. 1, 13–28.

- Akyeampong, Ernest B. 1997. “A Statistical Portrait of the Trade Union Movement.” Perspectives, Winter, Statistics Canada, Catalogue No. 75–001-XPE.

- Anderson, John, Charles A. O’Reilly III and Gloria Busman. 1980. “Union Decertification in the U.S.: 1947–1977.” Industrial Relations, Vol. 19, No. 1, 100–107.

- Anderson, John, Gloria Busman and Charles A. O’Reilly III. 1982. “The Decertification Process: Evidence from California.” Industrial Relations, Vol. 21, No. 2, 178–195.

- Bronfenbrenner, Kate. 1994. “Employer Behavior in Certification Elections and First-Contract Campaigns: Implications for Labor Law Reform.” Restoring the Promise of American Labor Law. S. Friedman et al., eds. Ithaca, New York: ILR Press, 75–89.

- Bronfenbrenner, Kate. 1996. “Final Report: The Effects of Plant Closing or Threat of Plant Closing on the Right of Workers to Organize.” Report submitted to the Labor Secretariat of the North American Commission for Labor Cooperation.

- Bronfenbrenner, Kate. 1997. “The Role of Union Strategies in NLRB Certification Elections.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 50, No. 2, 195–212.

- Bronfenbrenner, Kate. 2000. “Uneasy Terrain: The Impact of Capital Mobility on Workers, Wages, and Union Organizing.” Submitted to the U.S. Trade Deficit Review Commission, September 6, 2000.

- Bronfenbrenner, Kate and Tom Juravich. 1994. The Impact of Employer Opposition on Union Certification Win Rates: A Private/Public Sector Comparison. Economic Policy Institute. Working Paper 113.

- Bronfenbrenner, Kate and Tom Juravich. 1998. “It Takes More than House Calls: Organizing to Win with a Comprehensive Union-Building Strategy.” Organizing to Win: New Research on Union Strategies. K. Bronfenbrenner et al., eds. Ithaca, New York: ILR Press, 19–36.

- Bruce, Peter G. 1994. “On the Status of Workers’ Rights to Organize in the United States and Canada.” Restoring the Promise of American Labor Law. S. Friedman et al., eds. Ithaca, New York: ILR Press, 273–282.

- Cooke, William N. 1983. “Determinants of the Outcomes of Union Certification Elections.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 36, No. 3, 402–414.

- Cooke, William N. 1985a. “The Rising Toll of Discrimination against Union Activists.” Industrial Relations, Vol. 24, No. 3, 421–442.

- Cooke, William N. 1985b. “The Failure to Negotiate First Contracts: Determinants and Policy Implications.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 38, No. 2, 163–178.

- Delaney, John Thomas. 1981. “Union Success in Hospital Representation Elections.” Industrial Relations, Vol. 20, No. 2, 149–161.

- Dickens, William T. 1983. “The Effect of Company Campaigns on Certification Elections: Law and Reality Once Again.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 36, No. 4, 560–575.

- Drotning, John. 1967. “NLRB Remedies for Election Misconduct: An Analysis of Election Outcomes and their Determinants.” Journal of Business, Vol. 40, No. 2, 137–148.

- Elliott, Ralph D. and Benjamin M. Hawkins. 1982. “Do Union Organizing Activities Affect Decertification?” Journal of Labor Research, Vol. III, No. 2, 153–161.

- Forrest, Anne. 1989. “Effect of Unfair Labour Practice Complaints on Certification and Collective Bargaining.” Industrial Relations Issues for the 1990’s: Proceedings of the 26th Conference of the Canadian Industrial Relations Association. Laval University, Quebec: ACRI/CIRA, 423–431.

- Freeman, Richard B. and Morris Kleiner. 1990. “Employer Behavior in the Face of Union Organizing Drives.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 43, No. 4, 351–365.

- Getman, Julius G., Stephen B. Goldberg and Jeanne B. Herman. 1976. Union Representation Elections: Law and Reality. New York: Russel Sage Foundation.

- Hunt, Janet C. and Rudolph A. White. 1985. “The Effects of Management Practices on Union Election Returns.” Journal of Labor Research, Vol. VI, No. 4, 389–403.

- Hurd, Richard W. and Adrienne McElwain. 1988. “Organizing Clerical Workers: Determinants of Success.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 41, No. 3, 360–373.

- Koeller, C. Timothy. 1992. “Employer Unfair Labor Practices and Union Organizing Activity: A Simultaneous Equation Model.” Journal of Labor Research, Vol. XIII, No. 2, 173–187.

- Lawler, John. 1982. “Labor-Management Consultants in Union Organizing Campaigns: Do They Make a Difference?” Proceedings of the Thirty-Fourth Annual Winter Meeting, December 28–30, 1981, Washington, D.C. Madison, Wisc.: Industrial Relations Research Association, 274–280.

- Lawler, John and Greg Hundley. 1983. “Determinants of Certification and Decertification Activity.” Industrial Relations, Vol. 22, No. 3, 335–348.

- Lawler, John. 1984. “The Influence of Management Consultants on the Outcome of Union Certification Elections.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 38, No. 1, 38–51.

- Lawler, John and Robin West. 1985. “Impact of Union Avoidance Strategy in Representation Elections.” Industrial Relations, Vol. 24, No. 3, 406–442.

- Lawler, John. 1990. Unionization and Deunionization. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press.

- Macdonald, Alastair Peter. 1987. First Contract Arbitration in Canada. Kingston, Ontario: Industrial Relations Centre, Queen’s University. School of Industrial Relations, Research Essay Series No. 17.

- Maranto, Cheryl L. and Jack Fiorito. 1987. “The Effect of Union Characteristics on the Outcome of NLRB Certification Elections.” Industrial and Labour Relations Review, Vol. 40, No. 2, 225–238.

- Meyer, David and Trevor Bain. 1994. “Union Decertification Election Outcomes: Bargaining Unit Characteristics and Union Resources.” Journal of Labor Research, Vol. XV, No. 2, 117–136.

- Pavy, Gordon R. 1994. “Winning NLRB Elections and Establishing Collective Bargaining Relationships.” Restoring the Promise of American Labor Law. S. Friedman et al., eds. Ithaca, New York: ILR Press, 110–121.

- Peterson, Richard B., Thomas W. Lee and Barbara Finnegan. 1992. “Strategies and Tactics in Union Organizing Campaigns.” Industrial Relations, Vol. 31, No. 2, 370–381.

- Prosten, Richard. 1979. “The Longest Season: Union Organizing in the Last Decade.” Proceedings of the Thirty-First Annual Meeting, August 29–31, 1978, Chicago. Madison, Wisc.: Industrial Relations Research Association, 240–249.

- Reed, Thomas F. 1989. “Do Union Organizers Matter? Individual Differences, Campaign Practices, and Representation Election Outcomes.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 43, No. 1, 103–119.

- Reed, Thomas F. 1993. “Securing a Union Contract: Impact of the Union Organizer.” Industrial Relations, Vol. 32, No. 2, 188–203.

- Riddell, Chris. 2001. “Union Suppression and Certification Success.” Canadian Journal of Economics, Vol. 34, No. 2, 396–410.

- Roomkin, Myron and Hervey A. Juris. 1979. “Unions in the Traditional Sectors: The Middle Life Passage of the Labor Movement.” Proceedings of the Thirty-First Annual Meeting, August 28–31, 1978, Chicago. Madison, Wisc.: Industrial Relations Research Association, 212–222.

- Roomkin, Myron and Richard N. Block. 1981. “Case Processing Time and the Outcome of Representation Elections: Some Empirical Evidence.” University of Illinois Law Review, Vol. 1, No. 1, 75–97.

- Rose, Joseph B. 1972. “What Factors Influence Union Representation Elections?” Monthly Labor Review, Vol. 95, No. 10, 49–51.

- Sandver, Marcus H. 1980. “Predictors of Outcomes in NLRB Certification Elections.” Proceedings of the Twenty-Third Annual Meeting, April 10–12, 1980, Cincinnati, Ohio. Midwest Academy of Management, 174–181.

- Saporta, Ishak and Bryan Lincoln. 1995. “Managers’ and Workers’ Attitudes Toward Unions in the U.S. and Canada.” Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, Vol. 50, No. 3, 550–565.

- Scott, Clyde, Jim Simpson and Sharon Oswald. 1993. “An Empirical Analysis of Union Election Outcomes in the Electrical Utility Industry.” Journal of Labor Research, Vol. XIV, No. 3, 355–365.

- Seeber, Ronald L. and William N. Cooke. 1983. “The Decline in Union Success in NLRB Representation Elections.” Industrial Relations, Vol. 22, No. 1, 34–44.

- Sexton, Jean. 1987. “First Contract Arbitration in Canada.” Labor Law Journal, Vol. 38, No. 8, 508–518.

- Solomon, Norman A. 1985. “The Negotiation of First Collective Agreements under the Canada Labour Code: An Empirical Study.” Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, Vol. 40, No. 2, 458–470.

- StatisticsCanada. 1980. Standard Industrial Classification 1980. Catalogue No. 12–501–E. Ottawa: Ministry of Supply and Services Canada.

- Statistics Canada, Household Surveys Division. 1995. Labour Force Annual Averages 1989–1994. Catalogue No. 71–529. Ottawa: Minister of Industry, Science and Technology.

- Statistics Canada, Industrial Organization and Financial Division, Labour Unions Section. 1990–1994. Annual Report: Part II – Labour Unions. Catalogue No. 71–202. Ottawa: Minister of Industry, Science and Technology under the Corporations and Labour Unions Returns Act.

- Thomason, Terry. 1994a. “The Effect of Accelerated Certification Procedures on Union Organizing Success in Ontario.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 47, No. 2, 207–226.

- Thomason, Terry. 1994b. “Managerial Opposition to Union Certification in Quebec and Ontario.” Unpublished. Faculty of Management, McGill University.

- Thomason, Terry and Silvanna Pozzebon. 1998. “Managerial Opposition to Union Certification in Quebec and Ontario.” Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, Vol. 53, No. 4, 750–771.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Definitions and Weighted Means of Control Variables

Table 2

Employer Responses to Union Certification Applications

Table 3

Probability of Certification and of Early Decertification: Selected Coefficients and Changes in Probabilities from Logistic Regressions

Significant at the 0.10 level

at the 0.05 level

at the 0.01 level (two-tailed tests).

Early Decertification defined as: Bargaining unit decertified within first two open periods.

Estimated coefficients were converted to changes in probabilities associated with a one-unit change in each explanatory variable at the mean of the dependent variable. The change in probability of a certification outcome emanating from a one-unit change in continuous or categorical explanatory variables was calculated by applying the following formula: ∂P/∂P = P(1–P)b. Large discrete changes such as those associated with a change in a dichotomous independent variable, require the incorporation of the discrete change into the logistic function. Thus, the change in the probability of a certification outcome emanating from discrete changes associated with dichotomous independent variables was calculated using the following formula: ∆Pi = [ 1 + exp {–ln (P/(1–P)) – bi}] –1 – P.

Table 4

Probability of Concluding a First Collective Agreement and of Requiring Third-Party Assistance: Selected Coefficients and Changes in Probabilities from Logistic Regressions

10.7202/051034ar

10.7202/051034ar