Résumés

Abstract

The literature generically addresses controversies related to the lack of social acceptance of projects, usually overlooking their specificities. We argue instead that each trajectory of social acceptance (or lack thereof) is unique. This article demonstrates this through a qualitative analysis of three controversial projects: Matoush uranium mining (2006-2020), Facebook’s cryptocurrency (2017-2021), and Covid-19 vaccination (2020-2021). We develop an analytical framework that conceptualizes social acceptance as a dynamic trajectory of legitimation and justification revolving around three pillars: eco-traditional, symbolic, and technical. This article enriches our understanding of social acceptance issues and offers new research perspectives at the interface of social acceptance, legitimation, and institutional logics.

Keywords:

- social license to operate,

- legitimacy,

- institutional logics,

- orders of worth,

- projects,

- controversy

Résumé

La littérature aborde de manière générique les controverses liées à la non-acceptabilité sociale des projets. Nous soutenons plutôt que chaque trajectoire d’acceptabilité sociale (ou de non-acceptabilité) est unique. Cet article le démontre grâce à l’analyse qualitative de trois projets controversés : l’exploitation uranifère Matoush (2006-2020), la cryptomonnaie de Facebook (2017-2021) et la vaccination contre la Covid-19 (2020-2021). Nous développons un cadre d’analyse qui conceptualise l’acceptabilité sociale en tant que trajectoire dynamique de légitimation et de justification autour de trois piliers : éco-traditionnel, symbolique et technique. Cet article enrichit notre compréhension des enjeux d’acceptabilité sociale et offre des perspectives de recherche à l’interface de l’acceptabilité sociale, de la légitimation et des logiques institutionnelles.

Mots-clés :

- acceptabilité sociale,

- légitimité,

- logiques institutionnelles,

- économies de la grandeur,

- controverse

Resumen

La literatura aborda genéricamente las controversias sobre la falta de aceptación social de proyectos, obviando en gran medida sus particularidades. Sostenemos, en cambio, que cada trayectoria de aceptación social (o la falta de ella) es única. Este artículo lo demuestra mediante análisis cualitativos de tres proyectos controversiales: la minería de uranio Matoush (2006-2020), la criptomoneda de Facebook (2017-2021) y la vacunación contra la Covid-19 (2020-2021). Presentamos un marco analítico que conceptualiza la aceptación social como una trayectoria dinámica de legitimación y justificación con tres pilares: eco-tradicional, simbólico y técnico. Así, enriquecemos la comprensión de los problemas de aceptación social y brindamos perspectivas de investigación en la interfaz de la aceptación social, legitimación y lógicas institucionales.

Palabras clave:

- aceptabilidad social,

- legitimidad,

- lógicas institucionales,

- economías de la grandeza,

- controversia

Corps de l’article

Ubiquitous in society, high-impact projects commonly generate significant socio-economic and environmental controversies (Baba et al., 2021; Martens & Carvalho, 2017; Vanclay & Hanna, 2019), often presented as issues of social license to operate (SLO). Beyond the conceptual ambiguity that characterizes this concept, which we revisit in the literature review, we start from the idea that SLO refers to “the perception held by local stakeholders that a project, company or industry operating in a given region is socially acceptable or legitimate” (Raufflet et al., 2013: 2223). Project SLO has undeniably become a top strategic concern for organizations whose core business is based on projects (Boiral, Heras-Saizarbitoria, & Brotherton, 2019; Martens & Carvalho, 2017; Baba, Hemissi, Berrahou, & Traiki, 2021). SLO is also emerging as a major challenge for public policy makers, international institutions, and civil society as they attempt to clarify the contours of the new paradigm surrounding high-impact projects (Maillé, Baba, & Marcotte, 2023).

Given this reality, academics’ infatuation with SLO issues (Gehman, Lefsrud, & Fast, 2017) is therefore not surprising. This concept, virtually absent from the literature at the turn of the 21st century, now abounds in various journals. This literature, which has been burgeoning for at least a decade, has explored the definitional issues of SLO (Gehman, Lefsrud, & Fast, 2017), the best practices that encourage its development (Ofori & Ofori, 2019; Saenz, 2021), typologies and taxonomies (Boutilier & Thomson, 2011; Prno & Slocombe, 2014), as well as the antecedents, processes and results of various forms of relationship management between organizations and various stakeholders (Derakhshan, 2020; Di Maddaloni & Davis, 2018). Empirically, our understanding of SLO is primarily influenced by large-scale development projects with high environmental impacts, such as energy and natural resource projects (e.g. Costanza, 2016; Smits, Leeuwen, & Tatenhove, 2017). To a lesser extent, land use and public infrastructure have also been frequently explored as fertile empirical contexts (e.g. Fournis, Mbaye, & Guy, 2016).

While the literature is informative in many ways, our understanding of SLO is limited by the very fact that this literature has focused on large development projects, namely tangible projects with high socio-environmental impact. Consequently, the literature has emphasized a configuration where environmental issues are central to the controversy (e.g. Nyembo & Lees, 2020) and where traditional market and environmental forces clash. This trend has occurred at the expense of empirical contexts that allow for the exploration of more intangible projects (called soft projects in project management jargon), which place less emphasis on environmental problematizations (e.g. Dionne, Mailhot, & Langley, 2019).

Through an inductive approach within the field of organizational studies, this article attempts to better understand the multiple configurations of SLO issues, beyond the configuration we just described. To this end, two interrelated research questions are formulated: What are the possible configurations of controversies surrounding projects’ SLO? How do the institutional logics at work contribute to these configurations? A hybrid theoretical lens[1] linking institutional logics and orders of worth, sometimes called economies of worth, emerged as fruitful for exploring these questions and providing a conceptual guide for our empirical analysis. Methodologically, this article draws on the richness of the historical approach in organization theory (Maclean, Harvey, & Clegg, 2016) to better understand the multiple trajectories that controversies around SLO-deficient projects can take. The article analyzes three controversial projects: the Matoush uranium mining project (2006–2020), Facebook’s cryptocurrency project called Diem (2019–2022) and the COVID-19 mass vaccination project (2020–2021). The first project was conducted in Quebec, and the other two were international in scope. All of these projects have received ample media coverage: the Matoush project in Quebec, and the cryptocurrency and COVID-19 vaccination projects on the international scale.

This article enriches the literature on SLO by proposing an integrative analytical framework based on multiple logics of action and value systems to better interpret and analyze the various controversies surrounding SLO-deficient projects. The article suggests that the social licence of projects, be they tangible or intangible, is a process of legitimization negotiated around three pillars: eco-traditional, symbolic and technical. This conceptualization thus proposes to go beyond a fixed and homogenizing vision of SLO issues. The analytical framework thus resembles a repertoire of typical ideals, i.e., the proposed division of the pillars can take more hybrid forms in reality, especially if we consider the complexity of social reality. This article proposes several implications for SLO research and regarding the dynamics of legitimization in and around public controversies.

Theoretical background: from social license to operate to institutional logics

Social license to operate and related concepts

The literature on SLO is marked by a lack of convergence as it is characterized by considerable disciplinary and epistemological plurality. In the French-language literature, Batellier (2016: 6) identifies a distinction between “acceptabilité sociale” and “acceptation sociale.” The author associates the first concept with a public relations approach aimed at obtaining approval for projects, whereas the second concept aligns more with a process of co-construction and democratic dialogue between citizens and project proponents. In the English-language literature, several concepts are used interchangeably, notably “social acceptance,” “social acceptability,” and “public acceptance.” The first two terms, which are evidently the equivalents of the French terms mentioned above, date back to at least the 1970s. The concepts of “social acceptance” and “social acceptability” have thus been mobilized to better understand the societal reaction to new technologies (Otway & Winterfeldt, 1982), to changes in education (Dave, 1972), to satellite systems (Klineberg, 1980), and to logging (Bunnell, 1976). The same is true for the concept of “public acceptance,” which has been used since the 1970s to better understand the management of technological risks (Wynne, 1983), the reuse of wastewater (Sims & Baumann, 1974), innovation in health services (Metzner, Bashshur, & Shannon, 1972), the perception of the sales profession (Adkins & Swan, 1982), the public perception of sports (Harry Jebsen, 1979), and even the issues related to the reduction of prison sentences (Galaway, 1984).

More recently, the concept of SLO emerged in the literature to address similar issues (Raufflet et al., 2013). Introduced in the natural resource context to reflect issues of social resistance to development projects (Moore, 1996), this concept has gradually spread to other areas such as the blue economy (Voyer & Leeuwen, 2019), smart cities (Mann et al., 2020), and the use of megadata (Shaw, Sethi, & Cassel, 2020). However, it is still mainly used in the context of extractive industries and energy, unlike the concept of social acceptability, which has spread to other fields such as public policy and land use planning. That said, the concept of SLO is currently difficult to distinguish from other related concepts. We will therefore consider social acceptability and SLO as equivalent.

The literature offers two visions of SLO: a static vision oriented toward good practices and tools, and a processual and dynamic vision that foregrounds the processes of SLO construction and the associated dynamics. In the first vision, SLO is perceived as a product, intangible capital or a result that project promoters can develop and acquire through good management of relations with their stakeholders (Boutilier & Zdziarski, 2017; Saenz, 2021). As a result, there is a strong interest in identifying “best practices” to promote SLO (Prno, 2013; Vanclay & Hanna, 2019). Among the many studies that have been conducted, there has been a focus on modelling SLO and developing measures (Cruz et al., 2020), proposing best practices, and identifying success factors for “winning” (Ofori & Ofori, 2019) and “achieving” SLO (Baines & Edwards, 2018).

The second vision of SLO differs from the first in its more processual and dynamic approach, whereby SLO is considered as a negotiation (Rooney, Leach, & Ashworth, 2014; Saenz, 2021), a permanent construction (Prno & Slocombe, 2014), a long-term trajectory (Baba, Sasaki, & Vaara, 2021), a public debate (Dionne et al., 2019), a process of capacity building of local stakeholders (Syn, 2014), and even a legacy issue (Baba & Raufflet, 2014). This vision is based on essential principles: SLO is an intangible trajectory, constantly co-constructed by the actors, sensitive to the socio-cultural realities of each territory, and specific to each situation, and therefore difficult to limit to a few exemplary practices. The advocates of this processual conception of SLO therefore propose to go beyond the “best practices” that promote SLO and question the institutional, social and cultural dynamics of projects with a high socio-environmental impact (see Batellier, 2016; Gendron, 2014). Accordingly, numerous studies have explored the role of values, norms and social representations in the SLO process (Karimi & Toikka, 2014; Kim & Kim, 2015).

Despite the richness of this literature, our theoretical understanding of SLO is limited by the fact that the literature does not sufficiently theorize the multiplicity of SLO trajectories that ensue from the configurations of institutional logics at work around a project. Yet we know that SLO involves looking at the process through which stakeholders can agree on trade-offs related to projects with a high local impact. This process can vary according to the situation, the issues negotiated and the logics at work; Pasquero (2008) has theorized this process as a “socio-constructionist” dynamic, i.e., a dynamic that is constantly constructed (and continually reconstructed) by social actors.

A theoretical view combining institutional logics and economies of worth

Institutional logics greatly influence on the way social actors evaluate the organizations and projects that surround them in that they dictate the legitimacy of behaviours, actions and discourses (Pache & Santos, 2010). Introduced in 1985 by Alford and Friedland (1985), the concept of institutional logics is commonly understood as “the socially constructed, historical pattern of material practices, assumptions, values, beliefs, and rules by which individuals produce and reproduce their material subsistence, organize time and space, and provide meaning to their social reality” (Thornton & Ocasio, 1999: 804).

Empirical studies on institutional logics abound (see Durand & Thornton, 2018). These studies have often focused on conflicts between institutional logics, along with strategies for managing these conflicts and maintaining a balance between them (Greenwood et al., 2011). For example, in studying the Alberta health system, Reay and Hinings (2009) show that competing logics, notably the market and professional logics, can co-exist over time through the development of collaborative relationships. In another study based on a 15-month ethnography in a drug court, McPherson and Sauder (2013: 165) point out that “available logics closely resemble tools that can be creatively employed by actors to achieve individual and organizational goals.” Negotiations in the court thus mobilize logics to meet specific individual goals.

Institutional logics represent a fruitful theoretical framework for better understanding how actors belonging to divergent logics manage, despite their differences, to collaborate and get along in specific situations. Many scholars (Brandl et al., 2014; Pernkopf-Konhäusner, 2014) have sought to strengthen our understanding of institutional logics through the economies of worth (Boltanski & Thévenot, 1991), belonging to the French pragmatic sociology tradition. Boltanski and Thévenot’s economies of worth provide insight into the interplay of relational dynamics by focusing on the relationship, cooperation, compromises and confrontational reactions between actors in negotiation who may have different, even opposing, logics and values. This approach posits the existence of seven distinct groups of values called “cities” or “worlds.” Shared and endorsed by a collective, each city refers to a particular vision of social reality and to corresponding discourse or order of justification. It implies a rationality that acts as an argumentative framework to confirm or refute the legitimacy of the discourse and the action of others. Appendix 1 illustrates the values promoted by the various worlds.

Cloutier, Gond, and Leca (2017) argue that economies of worth enrich institutional logics by further exploring issues of legitimacy (how they are resolved on a day-to-day basis) and issues of morality, which are central to institutional logics. Other reflections have also emphasized the relevance of combining these theoretical perspectives in order to better account for situations where divergent logics meet and clash (Pernkopf-Konhäusner, 2014). In this hybrid perspective, Demers and Gond (2020) observed how a company in the shale gas industry led its members to manage a situation of complexity linked to the adoption of a new sustainable development orientation. The authors emphasize the importance of moral judgments in the mechanisms for managing this complexity. Moreover, by drawing on this same hybrid theoretical perspective, Patriotta, Gond, and Schultz (2011) show how a controversy involving a nuclear incident in Germany led the actors to mobilize rhetoric of justification tied to various orders of worth or logics. Specifically, they show the role of orders of worth “as multiple modalities for agreement which shape stakeholders’ public justifications during controversies” (p. 1804). Finally, Dionne et al. (2019) analyze a public controversy in Quebec related to university students. In particular, they underline the relevance of Boltanski and Thévenot’s orders of worth to shed light on the evolution of an evaluation process occurring during a public controversy. Our article is precisely in line with the research that combines the view of institutional logics and the explanatory power of economies of worth in terms of legitimization and the moral foundations of controversies (Cloutier & Langley, 2013). The paper thus empirically illustrates the relevance of combining these two theoretical perspectives to better understand the dynamics surrounding controversies (see Patriotta et al., 2011). In the next section, we present our methodological choices.

Research setting and methods

Research design. This research relies on a qualitative methodology to explore actors’ perceptions and (de)legitimization dynamics around three controversial projects. More precisely, it builds on the historical turn in organizational and management theory (Kipping & Üsdiken, 2014; Maclean et al., 2016) in order to better understand SLO dynamics through the analysis of historical events that have marked the public and social debate. These events often represent turning points in social and institutional trajectories (Druckman & Olekalns, 2011; Putnam & Fuller, 2014). A multi-case approach is adopted (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007) to develop a theory well supported by the analysis of various contexts, which can favour the generalization of our theoretical insights.

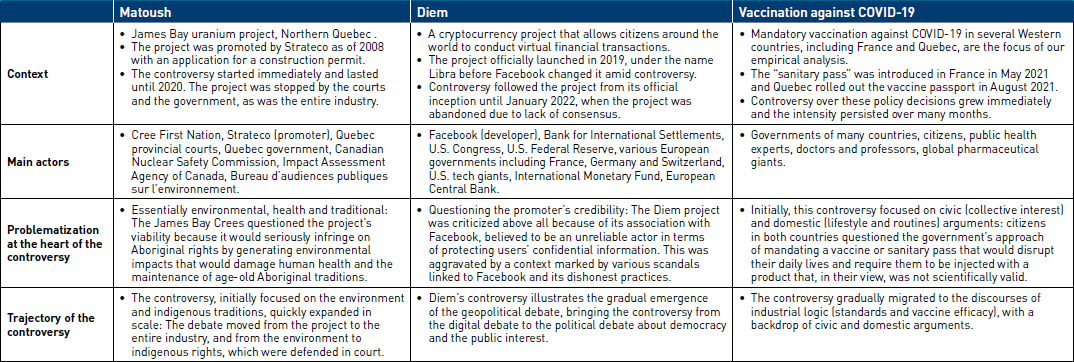

Choice and context of cases. Three case studies were selected to answer our research question following a theoretical sampling (Eisenhardt, 2021). Three selection criteria were used: 1) the context studied must present a situation of controversy that opposes a plurality of actors with divergent rationalities, 2) the controversies must concern various types of projects,[2] and 3) finally, consistent with our theoretical framework based on the economies of worth (Boltanski & Thévenot, 1991), we have chosen our three cases in such a way as to represent the deployment of various social worlds and orders of worth that embody them. Thus, the three controversies analyzed are the Matoush project (uranium exploration in Quebec), the Diem project (cryptocurrency proposed by Facebook) and the large-scale vaccination campaign (against COVID-19). Appendix 2 provides more details on the context of each controversy.

Data sources and collection. This research examined data available in the public domain. We ensured the quality and rigour of this qualitative research through data triangulation (Flick, 2018). Three complementary data sources were used and contrasted in order to understand and analyze the three cases selected. First, the electronic press was consulted to establish a chronology and identify the main actors, together with their interests and arguments. Both French (Le Devoir, La Presse, Radio-Canada, TVA Nouvelles, Le Point, Le Figaro, Les Echos) and English (The Guardian, BBC, The New York Times) electronic newspapers were consulted in detail. In-depth searches were carried out using French and English keywords for our three cases (“Matoush,” “Strateco,” “Moratorium on uranium & Quebec,” “Coronavirus,” “COVID-19,” “sanitary pass,” “Diem,” “Libra,” “Facebook scandal”). More than 150 articles were identified and analyzed, among the thousands of newspaper articles that have been published on the subjects examined. We limited the analysis to articles that corresponded to the selected keywords and that highlighted the issues of SLO and actors’ justification. No temporal or geographical tags applied, apart from the COVID-19 controversy being analyzed mainly in the Quebec and French contexts. Second, we viewed video clips, documentaries and expert interviews available on the Internet about the Matoush project and the Quebec uranium industry (approximately 1.5 hours), Facebook’s cryptocurrency (approximately 2 hours), and finally COVID-19 and its associated controversies (approximately 13 hours). Pertaining to the video clips, we favoured those that offered a general enough look to contextualize each controversy. This data collection phase began with a Web search to gather the plural perceptions of the actors involved in the three controversies. Third, these data were cross-referenced with other sources, notably works by experts and intellectuals as well as scientific articles on the management of the pandemic (Cheung & Parent, 2021; Koley & Dhole, 2021; Raoult, 2021; Tegnell, 2021), documents from the U.S. Senate (United States Senate, 2019) and the Bureau d’audiences publiques sur l’environnement (Francoeur, 2015).

Data Analysis. The data collected were analyzed abductively, by iteratively comparing data and theoretical insights (Timmermans & Tavory, 2012). The analysis proceeded in three steps performed recursively.

First, a timeline of key events was established for each case. In this way, we identified different intervals: 2006–2020 for the Matoush project, 2019–2021 for Facebook’s cryptocurrency, and 2020–2021 for the COVID-19 vaccination. We deliberately mapped the main actors involved in these controversies and identified the arguments they used to justify their respective positions. We were inspired in particular by Baba et al. (2021) work on problematization, i.e., the way in which the actors articulate the issues that concern them.

Next, we analyzed each of the controversies in more depth by mobilizing the seven social worlds developed in the economies of worth. This analysis determined that our three cases reflect different configurations in terms of the presence and confrontation of action logics. For example, the Matoush case clearly emphasizes environmental and traditional issues, i.e., the protection of the ancestral values of indigenous communities. The Diem case, in contrast, puts more emphasis on the issues of democracy and the protection of information and individual rights, which is more akin to the values of the civic world. By comparison, the case of vaccination conveyed the most sub-controversies owing to its complexity. The “industrial” dimension (debate around scientific standards and the vaccine development process) and the “civic” dimension of the controversy (individual freedoms, democracy, rights) predominated in this controversy. Thus, by contrasting the arguments mobilized by the actors and the lexical grammar of the economies of worth, we could better understand the essence of the controversies in question.

Lastly, to achieve a more aggregated conceptualization, we consolidate the different configurations of controversies around three pillars: symbolic (logics of opinion and inspiration), eco-traditional (domestic, civic and green logics) and technical (market and industrial logics). This triptych represents a typical ideal, rather than an impermeable distinction of action logics. To arrive at the nomenclature of the pillars, we were inspired by the reflections of Déry, Pezet, and Sardais (2020), who structured Boltanski and Thévenot’s worlds around three poles to conceptualize organizational identities: individuation, technicality and community. Note that these authors did not integrate the green logic in their conceptualization. Moreover, our nomenclature is also inspired by the classic work of Weber (1958), who recognizes three sources of legitimacy: traditional authority, rational-legal authority, and charismatic authority. Thus, in our analytical framework, the symbolic pillar refers to perceptions and symbols; the technical pillar refers to rationality and efficiency; and the eco-traditional pillar is concerned with the collective interest, the preservation of traditions in the broad sense, and the environment. Although these pillars are impermeable in our analytical model, they can also be viewed as being intertwined. For example, indigenous people refute the opposition between the green, civic and domestic logics because in their view there can be no social life or collective interest without a healthy environment (Fortin-Lefebvre & Baba, 2021).

Empirical analysis: the multiplicity of slo issues

Our empirical analysis underscores the plural nature of SLO issues surrounding high-impact projects. We show precisely how each situation involves a particular configuration in terms of problematization and justification in line with the worlds of Boltanski and Thévenot (1991). Table 3 provides a synthesis of the three cases analyzed.

The Eco-traditional Configuration: The Matoush project in James Bay Eeyou Istchee

The analysis of the Matoush uranium project highlights what we conceptualize as an eco-traditional configuration, in reference to the importance of environmental and traditional dimensions during this controversy. In this case, the local communities problematized the situation mainly by defending interests related to the environment and ancestral traditions. Accordingly, the project evaluation modalities adopted were largely inspired by the values promoted by the domestic and green worlds.

A problematization that primarily reflects the environment, health, and tradition. All of the arguments formulated by the Crees during the decade of controversy, between 2010 and 2020, underscore the consistency of their arguments and the values that drive their rejection of the project proposed by Strateco. Issues related to the environmental, human health and ancestral values are central to this argument. As the report of the Bureau d’audiences publiques sur l’environnement clearly indicates, “the opposition of the Crees, specified in numerous testimonies, can be largely explained by the special relationship they have with nature and their territory” (Francoeur, 2015: 368). During the hearings, many Cree participants stressed that “the land has been handed down for our care, and we are just borrowing it from future generations to come” (Mémoire déposé au BAPE, Neeposh, 2014: 1) or that the “[Cree] people have always depended on this land, rivers and lakes for their daily sustenance” (Mémoire, BAPE, Grand Chief de la Nation de Chisasibi, Bobbish, 2014: 3). These environmental concerns were shared by the Cree Youth Grand Chief Joshua Iserhoff, who emphasized the importance of preserving the sacred places where the Cree practise their traditional fishing activities: “One of our community’s favorite fishing spots, Gobanji, is located on Lake Mistissini, very close to Strateco’s Matoush project” (Rettino-Parazelli, 2014). The case of the Cree nation thus exemplifies a strong relationship between the problematization of environmental and traditional issues, in the sense that Cree ancestral practices are tied to a healthy environment. Problems related to animal and human health are also mentioned by the Grand Council of the Crees: “Waters contaminated by radionuclides and other heavy metals can have far-reaching consequences on our communities… Uranium and its decay products as well as other contaminants can also enter the local food chain of both animal predators and the local population” (Grand Council of the Crees of Eeyou Istchee, 2014c: 11).

From environmental issues to the question of Aboriginal rights. In the face of formal Cree opposition to the Matoush Project, the developer Strateco asserted the precedence of environmental authorizations it had obtained from the government. This led to politicization of the controversy by bringing it into the realm of Aboriginal rights. This gradual shift took place in two stages. First, the year 2013 marked a turning point when Strateco took legal action to “force the Ministère de l’Environnement du Québec to make a decision regarding authorization for the Matoush uranium mine advanced exploration project” (Radio-Canada, 2013). The trajectory of controversy thus took an unexpected turn when Strateco also attempted, through this legal recourse to the Quebec Superior Court, to “overturn a recommendation of the Comité provincial d’examen (provincial review committee, or COMEX) … [that] recommended that the government accept Strateco’s project, but with certain conditions, the first of which was to obtain written consent from the Crees” (Radio-Canada, 2013). Cree leaders viewed this judicialization of the controversy negatively and interpreted it as an attempt to narrow the scope of Aboriginal rights: “Strateco’s legal action represents a fundamental challenge to the principle of social acceptability, and to our treaty rights. We are committed to protecting our environment and our treaty rights, for current and future generations” (Grand Chef Matthew Coon Come, Grand Conseil des Cris, 2013). When the Court of Appeal definitively rejected Strateco’s legal challenge on January 16, 2020, the Grand Chief of the Crees once again recognized the highly political dimension of the controversy: “For the Cree Nation, this decision is about more than just the Matoush Project, this judgment upholds the integrity of the unique environmental and social impact review process established by the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. It is a significant recognition and reinforcement of our treaty rights…” (Grand Chef Abel Bosum, Cree Nation Government, 2020).

From a local issue to a provincial issue. The Matoush Project also illustrates an interesting spatial trajectory. Whereas the controversy initially had a significant territorial anchor in that it was limited to the traditional territory of the Crees in James Bay Eeyou Istchee, it gradually became a provincial issue. As early as 2012, “the James Bay Cree Nation declared a permanent moratorium on uranium exploration and mining in Eeyou Istchee, the James Bay Cree territory” (TVA Nouvelles, 2012). In March 2013, a few months after the Cree moratorium, the Government of Quebec also declared a temporary moratorium on uranium exploration and mining in the entire province, while the BAPE conducted an investigation. The inquiry began in May 2014, and several hearings were held on Cree territory, in James Bay Eeyou Istchee (Grand Council of the Crees of Eeyou Istchee, 2014b). The desire to make the Matoush project a “Quebec” affair and not just a “Cree” affair is evident in the statement of Grand Chief Matthew Coon Come: “We have always maintained that once Quebecers learned what the Cree Nation has come to know about uranium mining and radioactive waste, they would stand with us” (Grand Council of the Crees of Eeyou Istchee, 2014a). To form alliances beyond the traditional territory, the Crees then launched a media campaign on social networks: “The Crees are only one voice and so we are seeking allies” (Grand Chief Matthew Coon Come, CBC News, 2014). The local controversy thus became a provincial debate, which pro-mining lobbies joined after Strateco’s defeat at the legal level: “what message is the government, which is the manager of the resource, sending to small and medium-sized exploration companies with this judgment?” (Valérie Fillion, directrice générale de l’Association d’exploration minière du Québec, Radio-Canada, 2017)

Analytical synthesis. The analysis of the Matoush project controversy highlights three interesting dynamics. First, it is firmly anchored in a widespread configuration opposing environmental and traditional logics to the market logic. On the one hand, a First Nation seeks to protect its millennial traditional territory as well as its values and traditional lifestyle. On the other hand, a promoter wants to develop a project at all costs to satisfy the market demand. This configuration dominated the controversy throughout the project, from 2010 to 2020. The second dynamic of this case illustrates the presence of sub-issues peripheral to the dominant configuration. We have seen how the Crees have progressively oriented their argumentation toward considerations that are closer to the protection of Aboriginal rights, and thus to the civic logic of Boltanski and Thévenot (1991). This suggests that the presence of a dominant configuration in a controversy does not preclude the presence of other competing logics of action and argumentation. Third, the Matoush case also illustrates the evolving nature of SLO trajectories, thus raising the question of temporality. In this particular case, the judicialization and politicization of the controversy have considerably marked the evolution of the controversy; the Crees saw the legal proceedings launched by Strateco as a means of infringing on their Aboriginal rights. Further, the Matoush case reflects the spillover effect of controversy from a specific project to the entire uranium industry in Quebec.

The symbolic configuration: Diem, the Facebook cryptocurrency

The analysis of the controversy surrounding Diem reveals a symbolic configuration that centres on actors’ reputation and credibility. Our analysis highlights the extent to which the Diem project has been evaluated by several stakeholders in terms of the reputation of Facebook, its CEO Mark Zuckerberg, and the Diem association, of which Facebook is a major actor. Although the controversy is mainly rooted in values promoted by the opinion world, our analysis points to a peripheral issue related to the civic world, pertaining to the collective interest and democracy.

Problematization: Questioning the proponent's credibility. In the controversy around the Diem project, the main criteria of evaluation is the sponsor’s reputation, i.e., the world of opinion. In 2018, Facebook was involved in a scandal whereby it shared massive quantities of user data with corporations, without the users’ consent. Consequently, CNN argued that “Mark Zuckerberg has lost all credibility with Congress - and the rest of us” (Alaimo, 2018). This scandal concerns the exposure of mechanisms and consequences of advertising and political targeting (Lagos, 2020). According to the American polling company Harris Poll commissioned in 2018 by the newspaper Fortune to study the impact of the scandal on the reputation of Facebook, “Facebook [was then] at the bottom of the pack in terms of trust in hosting your personal data (…) Facebook’s crises continue to roll in the news cycle” (Vanian, 2018). In response to this breach of hosted data privacy, Facebook’s CEO had to explain himself to the U.S. Senate. To salvage his battered reputation, the Facebook CEO renamed his cryptocurrency and relocated the Diem Association to California. The Association maintained that these measures are part of a strategy “to distance the project from Facebook and, presumably, from its own troubled past. The name change is not just stylistic” (Dalton, 2020).

From a digital issue to an international political issue. In addition to the central issue of reputation, the controversy also highlights the peripheral issue of lingering regulatory barriers. There were fears that the future cryptocurrency might override government control, become autonomous, and blur civic accountability to society. If the digital issue refers to the civic world, it once again points out that the main dimension of the controversy is in the reputation of Facebook and its CEO, whose reputations governments believe have been tarnished by multiple scandals that call into question the company’s values. Thus, despite a name change from Libra to Diem in order to leave these reputational issues behind, the project “the project is still facing backlash [as] Germany’s finance minister called the cryptocurrency a ‘wolf in sheep’s clothing’ on Dec. 8, alleging that … currencies should remain under the control of states and governance” (Dalton, 2020).

Our analysis points out that the digital issue regarding governmental norms led to an international issue characterized by the emergence of a civic logic in the controversy. In addition to the basic reticence regarding the protection of private information, there was apprehension about criminal use of the parallel banking circuit; money laundering, tax evasion, and financing of crime have been evoked (Chenel, 2021). What worried governments, banks and world leaders in bank credit cards is the knowledge that this cryptocurrency may end up having, over time, its own use value, becoming a real private central bank and therefore free of any democratic obligation to account to citizens. Several countries, including Russia, France, Italy and Germany, opposed to the project. In response to this geopolitical controversy, Facebook is precisely asserting values promoted by the civic world, and primarily American collective interests. For example, in the fall of 2019, Mark Zuckerberg testified before the U.S. House Committee on Financial Services and stated that his cryptocurrency “will extend America’s financial leadership as well as our democratic values and oversight around the world… While we debate these issues, the rest of the world isn’t waiting. China is moving quickly to launch similar ideas in the coming months… If America doesn’t innovate, our financial leadership is not guaranteed” (Rodriguez, 2019)

From lack of credibility to breaking corporate alliances. The bold “blockchain” (a kind of ledger of transactions) technology on which Facebook’s cryptocurrency is designed allows instant, secure, and transparent exchange of information alongside the traditional banking network. Many high-profile collaborating organizations were contributing to the cryptocurrency project, including Shopify, PayPal, Uber, Visa, MasterCard and eBay. In the fall of 2019, as Marc Zuckerberg was asked by the U.S. House Financial Services Committee to clarify the independence of the association that was supposed to manage the cryptocurrency, the credibility issue reached its peak. During the same period, several organizations broke their alliance with the project and withdrew from the association. The British newspaper The Guardian pointed out that “PayPal has become the first company to drop out of … the embattled project (which) continues to face queries from regulators around the world” (Hern, 2019). That said, although PayPal did not explain the reason for its withdrawal, Visa discussed its choice more openly “our ultimate decision will be determined by a number of factors, including the Association’s ability to fully satisfy all requisite regulatory expectations. ” (Castillo, 2019)

Analytical synthesis. The analysis of the Diem Project controversy highlights three interesting dynamics. First, this controversy is firmly anchored in a configuration in which the logic of opinion predominates. Here, the promoter's reputation holds a central position, particularly regarding the technological aspects associated with safeguarding the confidentiality of digital data. Second, an additional controversy that ended up becoming central is that surrounding the geopolitical issue: states, banks, and global bank credit card leaders suspected that cryptocurrency could become self-sustaining, blurring civic accountability to citizens. We have seen how Facebook argued for the acceptability of its project by referring precisely to the values of the civic world in relation to maximizing public access to financial services. Third, the Diem case also illustrates the evolving nature of SLO trajectories, highlighting the importance of considering temporality. In this particular case, the trajectory of the Diem controversy notably illustrates an evolution from a “digital” and a priori impersonal controversy to a political debate, giving the controversy a new dimension related to democracy and the collective interest.

The technical configuration: vaccination against COVID-19

The third case analyzed, that of the vaccination against COVID-19, reveals a configuration of SLO involving issues of individual freedom, collective interests and scientific norms and standards related to vaccines. The vaccination campaign perceived as being “imposed from above” by many citizens around the world was thus evaluated first through the prism of the civic world because of the perception of a decrease in individual freedoms. In reality, these “civic” concerns focus primarily on the values promoted by the industrial world, namely standards, efficiency and scientificity surrounding the discovery of vaccines, their innocuousness and the duration of immunity. The precedence of the question of vaccine efficacy and safety is thus central to the technical configuration. Given local idiosyncrasies, our analysis focuses primarily on the situation in France and Quebec, where the “sanitary pass” (dubbed the vaccine passport in Quebec) became mandatory in May and August 2021 respectively, exacerbating public controversy.

An initially civic and domestic problematization. Note that the controversy surrounding vaccination did not begin with the administration of vaccines to the population, but rather with the crisis management preceding their development by the pharmaceutical industry (Hafsi & Baba, 2022). This controversy was mainly built around the civic world. It began with confinement, followed by curfews and preventive measures that some describe as impeding individual liberties. The controversy was also built around the domestic world with the disruption of citizens’ routines and habits. After the first cases of COVID-19 were detected in Wuhan, China, and the rapid rise in their numbers, the pandemic was soon declared. Governments then rushed to produce a vaccination plan and asked citizens to comply in the name of public health and the collective interest, a fundamental value of the civic world.

Assuming that the health emergency gave de facto legitimacy to their top-down approach, the public authorities forwent debate with other elected political parties or public consultation of any kind. Many citizens found fault with this approach, viewing it as being at odds with their conception of their democratic rights. Other members of the public, equally repulsed by this imposed approach, wanted to better understand the reasons for the unilateral health decisions that they perceived as arbitrary: “the calls for more transparency that we hear these days are not completely unfounded…” (Mercure, 2020). This point of view was shared by a part of the medical community. In January 2021, as vaccination was getting underway in Canada, the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians called on the government to be more transparent about the distribution of the first doses of vaccine and the precise characteristics of the groups of citizens to be given priority (Le Soleil, 2021). Regarding the disruption of habits and lifestyles (domestic world), “health indiscipline” drew media attention: “disobedience seems … to be rising in the face of restrictions… The premiers in the country and even the Pope have begged citizens not to go on vacation in the South…” (Baillargeon, 2021).

The arrival of vaccines and the evolution of the controversy toward the industrial logic. Although the controversy surrounding vaccination is anchored in a configuration that grants prevalence to the civic and domestic worlds, as explained above, it also presents an additional stake anchored in the industrial world. This will definitely shape the rest of the trajectory of this controversy. Thus, the SLO questions surrounding the epidemiological standards to meet and the fundamental characteristics of vaccines are among the elements concerned here. The speed with which vaccines have been developed has raised much doubt about the rigour of the scientific process, compliance with the usual standards, and consequently the efficacy and safety of the resulting vaccines. Describing vaccination as “the greatest health scandal of the 21st century” in his essay entitled Carnets de guerre COVID-19, Didier Raoult (a physician specializing in infectious diseases) questions the safety and efficacy of vaccines: “I said that vaccines are the stuff of science fiction to me … take the example of the flu vaccine, it took 15 years to stabilize it and even now it is not 100% reliable…” (Didier Raoult, Sud Radio, December 2020). The widespread suspicion about compliance with epidemiological standards in the development of vaccines or the concerns about the danger of the new RNA technology, show that the controversy is mainly rooted in the industrial world. The effect of this suspicion was reinforced because it has been shared by some world-renowned scientists. Moreover, it is interesting to note that if there were total confidence in vaccines, in terms of their properties and alignment with scientific standards, the civic dilemma would probably not have arisen with the same intensity. It is precisely the mistrust inspired by a rhetoric that mirrors the industrial logic that seems to raise civic questions about individual freedom to reject vaccines. A demonstrator in Bordeaux expressed this connection well: “We want to know what is being injected into our bodies… All we want is freedom” (France 24, 2021).

The complexity of the controversy and the advent of the “sanitary pass”. In the summer of 2021, the French government decided to accelerate the pace of vaccination by introducing a “sanitary pass” that citizens would require to access many areas of social life. The Quebec government quickly followed suit. In several regions, people vocally opposed these obligations, which were perceived as an infringement on individual freedoms. For example, in Quebec, as the vaccine passport was about to be tested in sports bars (August 2021), one politician called it undemocratic: “Quebec is about to adopt possibly the measure most antithetical to freedom in our lifetime since the war measures, and it will be done without debate, without a vote, without discussion, without dialogue among Quebecers, without modification, without amendment” (Radio-Canada, 2021b). This comment echoes that of another Quebec politician who describes the passport as “dangerous,” while stating that he was concerned about “seeing the premier engaging in demagogy with health measures.” In addition, he asked that the use of the passport be well supervised in order to avoid “abuses and discriminatory excesses” (Radio-Canada, 2021b). In France, despite the same concerns about the potential discrimination that the pass could cause, the country chose to implement the pass in a range of public places such as restaurants, cinemas, hospitals and transport (Marion, 2021).

Lastly, it is worth noting the market dimension of this controversy, which is less present in the analysis than are the other worlds. Epidemiologist Didier Raoult summarizes this dimension as follows: “they [the pharmaceutical companies] are salesmen … they are not salesmen of humanity” (IHU Méditerranée-Infection, 2021). Around the same time, the newspaper Libération denounced the industry’s staggering profits, explaining that “vaccine prices would have been artificially inflated by pharmaceutical companies taking advantage of their monopolies” and that said pharmaceutical companies “put their financial interest ahead of the general interest” (Quentin, 2021). These worries about the huge financial benefits of mass vaccination stoked widespread suspicion about pharmaceutical companies’ transparency regarding vaccines.

Analytical synthesis. The analysis of the COVID-19 vaccination controversy proposed above highlights three interesting dynamics. First, although it was initially civic and domestic, this controversy has progressively migrated toward the discourses of industrial logic, questioning the precipitous development of vaccines, compliance with scientific standards intended to ensure their safety, and their effectiveness in terms of immunity. The controversy, however, remained associated with the civic and domestic logics regarding the hindrance of democratic and individual liberties (civic world), the disruption of citizens’ routines and habits (domestic world) and the incessant obligation of the “sanitary pass” (civic and domestic worlds). Second, this case illustrates peripheral issues related to the market world. The controversy over conflicts of interest has led investigative journalists to highlight the huge profits of the pharmaceutical industry, suggesting that vaccination might serve the interests of the pharmaceutical giants first and foremost, who would then be willing to market vaccines at any cost. Third, this case also illustrates, as have the two previous ones, the evolving nature of SLO trajectories, and underlines the importance of considering the temporality and complexity of controversies in terms of the prevailing action logics. In this particular case, the industrial dimension of the controversy, linked to vaccine efficacy and safety, becomes a fundamental dimension that underlies even the arguments of a civic nature (individual freedoms and collective interest).

Discussion and conclusion

Our article suggests that the SLO of projects, be they tangible or intangible, is a contextualized construction that goes through a process of negotiated legitimization between various logics. Below, we discuss the implications of this article for research and practice.

Conceptualization of an analysis framework for SLO configurations

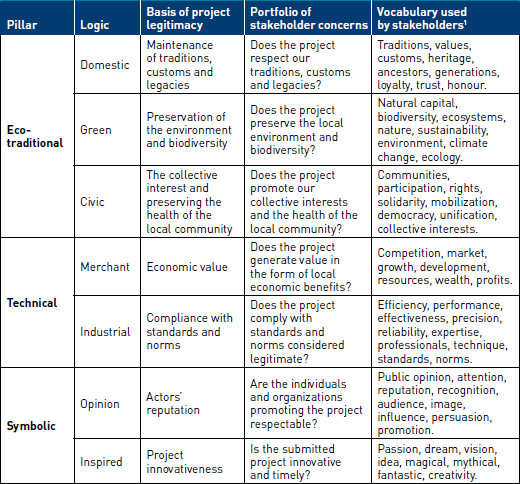

Our article conceptualizes a framework for analyzing SLO issues. This framework recognizes three pillars around which projects’ SLO is negotiated: eco-traditional, symbolic and technical. This framework can be construed as a repertoire of ideal types in that the complexity of the social fact can add nuances and subtleties. Moreover, the logics that make up these pillars can reinforce each other. Table 1 synthesizes these ideas, which we develop below.

Table 1

Analysis framework for project SLO issues

1. This vocabulary list draws on the empirical work of Patriotta, Gond, and Schultz (2011) and of Boltanski and Thévenot (1991).

The eco-traditional pillar. In general, the eco-traditional pillar concerns traditions, the collective interest and the environment. This pillar leads actors to evaluate projects submitted to them according to their norms and values, as well as higher collective interests. Three action logics are at the heart of the traditions pillar: the domestic logic, the civic logic, and the green logic.

First, the domestic logic involves the maintenance of traditions, customs and heritages. This is a crucial logic in so-called traditional societies that value the perpetuation of ancestral traditions, cultural activities and practices. In traditional societies such as indigenous communities, ancestral practices and knowledge are at the heart of actors’ identity (Fortin-Lefebvre & Baba, 2021). This explains why historically, First Nations and large-scale mining development projects have had conflicting relationships. The domestic logic can also manifest itself in non-Aboriginal contexts, when a project challenges actors’ habits and routines. Second, the civic logic advocates reflection on the collective interest and respect for the health of the stakeholders involved in the project. This logic thus emphasizes the impact of projects on individuals’ health, as well as on the higher interests of the collective. Notably, the health of individuals (both physical and psychological) and the collective interests are among the arguments raised by local stakeholders that oppose the project. Finally, there is also the green logic, historically at the forefront of the greatest social mobilizations and controversies linked to projects whose negative impact on the preservation of ecosystems, biodiversity and the environment is anticipated (Houck, 2010).

We have seen the deployment of this pillar in the controversy related to the Matoush uranium project, around which the Cree First Nation has mobilized arguments that are central to the green, domestic and civic logics.

The technical pillar. The second pillar of our analysis framework is called technical. It is mainly rational in the sense that its bases refer to the technical characteristics and quantified standards of the project. Economic rationality, cost-benefit calculations, financial benefits for shareholders, social and economic benefits for stakeholders, and the precedence of industrial standards and norms are recurring elements that promoters generally emphasize to obtain SLO for their projects.

The technical pillar mobilizes two institutional logics: the industrial logic, concerned with norms and standards; and the market logic, concerned with the socio-economic benefits of the project for the stakeholders. Stakeholders that adhere to the industrial logic, which is associated with compliance, evaluate the project by judging its ability to meet norms, industrial standards and certifications related to the ecological, safety or efficiency aspects of the field. Also inherent to the technical pillar, the market logic concerns the socio-economic value of a project and equity in the sharing of the benefits generated. Stakeholders thus expect the economic benefits of any project to be equitable and fair.

The technical pillar is well illustrated in the COVID-19 vaccination controversy, with a problematization focusing on the industrial logic (efficacy and scientific quality of vaccines).

The symbolic pillar. Finally, the symbolic pillar differs from the two previous ones in that it can focus not only on the project, but also on the actors (individuals and organizations promoting the projects). It offers actors two logics for evaluating the project: opinion and inspiration. The logic of opinion values reputation and credibility. Actors in this logic of action ask whether the individuals and organizations promoting the project are respectable and credible given their past accomplishments. When an organization whose reputation is tarnished by scandals proposes a project, it is often evaluated negatively because of its promoter’s weak credibility.

Further, the evaluation of projects with an inspiration logic focuses on their innovative character. Is the project innovative, in line with trends, or is it outdated? The evaluation of this innovativeness can be technical (how the project is done), symbolic (the values conveyed by the project) or visual (the aspect of the project and its tangible impacts, whether visual or geophysical).

Finally, the symbolic pillar takes on its full meaning in the controversy surrounding Facebook’s cryptocurrency. Rather than focusing on the standards or the efficiency of the project, the arguments mobilized by the opponents of the project have mainly concerned the credibility and reputation of its promoter, Facebook.

Implications for research on SLO and legitimacy

The journey to understand the antecedents and processes of the SLO is a prominent theme in the literature. While several conceptualizations have shed light on the processes that can lead actors with divergent interests to agree on a compromise (Boiral et al., 2019; Ofori & Ofori, 2019; Voyer & Leeuwen, 2019), the literature has not provided a convincing conceptualization of SLO that provides insight into the different possible trajectories of the issues that underlie the controversies. Our article has filled this gap by proposing an analysis framework based on a plurality of action logics and value systems, in order to better interpret and analyze any situation where SLO issues arise.

This conceptualization is a useful contribution to the literature on projects’ SLO in that it allows us to theorize a variety of possible trajectories according to three pillars: eco-traditional, symbolic and technical. This way of understanding the dynamics of SLO suggests that each controversial project must be analyzed in light of the action logics and the value systems conveyed by the actors involved. In other words, each configuration is distinctive in that the logics (or worlds) in confrontation diverge from one situation to another, from one project to another, and from one context to another. The resulting problematizations will therefore vary, which will greatly influence the trajectories of these controversies. Thus, the trajectories of SLO that allow actors with divergent interests to reach a compromise will naturally depend on their capacity to reconcile their respective value systems, considered to be the most durable form of collaboration between logics (worlds) by Boltanski and Thévenot (1991).

This conceptualization of the processes leading (or not) to SLO thus challenges the static and deterministic view whereby “variables” and “good practices” necessarily lead to the achievement of SLO (see Baba, Courcelles, & Dunn, 2022; Martinez & Franks, 2014; Prno, 2013). On the contrary, our conceptualization suggests that each situation subject to social debate regarding its SLO will be unique, depending on the action logics at play, which are notably conveyed by the stakeholders. More generally, this article is in line with several works on business-community relations that suggest that these relations are part of processual dynamics of permanent negotiation (Baba, Mohammad, & Young, 2021; Labelle, 2006; Pasquero, 2008). Identifying this plurality requires an in-depth analysis of the prevailing action logics, which our article precisely theorizes.

Our article also contributes to the legitimacy literature (Suddaby, Bitektine, & Haack, 2017). For example, it extends the work of Gond et al. (2016), which theorizes the role of power and (economies of worth-based) justification around the shale gas industry controversy in Canada. While the authors have shown how the use of justification arguments evolves over the course of a controversy, our analytical framework offers a more holistic heuristic approach to interpreting and making sense of the configuration of each social debate around a project. Similarly, our work enriches one of the few empirical texts that has combined the institutional perspective of legitimacy with an economies of worth-based perspective (Patriotta et al., 2011). In analyzing a nuclear energy controversy in Germany, the authors underline “the role of meta-level ‘orders of worth’ as multiple modalities for agreement which shape stakeholders’ public justifications during controversies” (p. 1804). Their contribution precisely consisted in theorizing a process of how actors could “repair” their loss of legitimacy. In this process, the multiplicity of justification arguments played a key role. Our conceptualization of the SLO framework complements the results of this research by further theorizing the plurality of justification arguments around the issues of high-impact project controversies. Moreover, although research on legitimacy is burgeoning (Suddaby et al., 2017) these theoretical developments have resulted in a strong focus on the legitimacy of traditional sustainable organizations. Our article thus redirects attention toward project legitimacy, an increasingly important issue.

Contributions for practitioners and policy makers

Our integrative framework offers two useful contributions for practitioners and policy makers. The first is related to the approach toward addressing SLO issues. Rather than treating these issues in a universal and standardized way, our paper suggests that each issue is distinctly shaped by the action logics and interests promoted by local stakeholders. By understanding the logics of action at work, organizations and decision-makers can put in place management strategies and approaches that foster SLO and compromise because they are adapted to the context. The second practical contribution follows from the first one: it pertains to the usefulness of the framework developed, which can serve as a heuristic to make sense of the controversies surrounding projects with high socio-environmental impacts. Although models and typologies for assessing the level of SLO have been put forth, the literature does not offer a framework for analyzing and mapping possible trajectories of SLO issues that considers the pluralism of action logics at work.

Parties annexes

Appendices

appendix 1. Presentation of the worlds of orders of worth

Given the relevance of the theoretical intersection of institutional logics and orders of worth (OW), below we explore the institutional logics through the orders of worth of Boltanski and Thévenot. As we explained earlier, OW focus on a grammar of justification and evaluation that is underpinned by several worlds.[3] First, the inspired world refers to the genius of the artist and the creative “daydream.” The worth of the inspired world refers to the state of grace, to creativity and to “that which is beyond measure, especially in its industrial forms” (Boltanski & Thévenot, 1991). In contrast, the domestic world deals with interpersonal and hierarchical relations, anchored in tradition and habits, especially in terms of rules of propriety. The worth of the domestic world is “a function of the position occupied in chains of personal dependencies…” (Boltanski & Thévenot, 1991). Third, the civic world is linked to the collectives endorsing common interests and uniting their efforts toward concerted actions. The worth of this world lies in equality and the common will to strive toward a socially noble and unifying cause that offers members dignity and frees them from their egoism. Fourth, the world of opinion informs and persuades. The worth of this world comes from the speaker’s recognized expertise. People are relevant in so far as they make up an audience whose “opinion prevails.” In this world, “worth is based on the recognition and credit of opinion given by others” (Breviglieri & Stavo-Debauge, 1999: 8). By comparison, the worth of the market world is derived from the possession of material goods, money and the profit attainable by being competitive. Wealth and luxury items are examples of objects that characterize this world. Sixth, the industrial world is one of effectiveness and efficiency. Linked to the technical and scientific vocabulary of productivity and time and motion analysis, it is turned toward the future, toward reengineering and continuous improvement. The worth of the industrial world is that of objectivity, expertise and technical skills. Finally, the green world emphasizes the protection of ecosystems and biodiversity. This world thus advocates the integration of nature in the orders of worth (Thevenot & Lafaye, 1993).

appendix 2. Background to the Three Case Studies

Matoush Uranium Project. Canada is the world’s second largest producer of uranium, accounting for nearly 13% of global production in 2018 (Government of Canada, 2020). This production comes mainly from two sites, McArthur River and Cigar Lake, Saskatchewan. In 2006, Strateco began uranium exploration in the Otish Mountains, north of Chibougamau and about 200 kilometres from the Cree community of Mistissini, Quebec. It was the largest uranium exploration project in the province. A major regional mobilization in the James Bay region strongly criticized the Matoush Project and emphasized the significant environmental risks. Several attempts by Strateco, including the creation of a permanent community relations position, failed to resolve the controversy: “Our message is clear: We have said no to uranium mining and exploration in Eeyou Istchee,” Youth Chairman Joshua Iserhoff noted (Grand Council of the Crees, 2013).

The Diem cryptocurrency project. As one of the web giants referred to by the acronym GAFAM (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft), Facebook had some 2.6 billion monthly active users and 1.73 billion daily active users in 2020. Since its founding in 2004, Facebook has become somewhat institutionalized by permeating the daily routine of billions of users. In June 2019, Facebook announced its desire to launch a cryptocurrency, initially called Libra, that will allow “its billions of users to make financial transactions across the globe, in a move that could potentially shake up the world’s banking system” (Paul, 2019). Despite its desire to offer “low-cost … and more inclusive” financial services, said (David Marcus, Head of Libra, Facebook, United States Senate, 2019: 1), the project has yet to be implemented due to a series of controversies and reservations shared by the authorities in several countries. These debates centre on issues of information security and the democratic risk linked to the hegemonic multinational, which, was notably concomitantly embroiled in several scandals about its use of confidential data and its role in democratic elections (Bouie, 2020; Criddle, 2020). The project was finally abandoned in January 2022 by Facebook, which sold the project to the bank Silvergate Capital for about $200 million (Roof, 2022).

Large-scale COVID-19 vaccination. Since the first cases of COVID-19 detected in Wuhan, China in December 2019, the global total as of December 2022 exceeded 660 million cases and some 6.6 million deaths. The complexity of the vaccine campaign in response to this pandemic is well documented (Muller, 2021). For the Montaigne Institute, which studies “the effectiveness of public action in France,” this pandemic involves, like those to come, logistical, digital and human issues, the latter being the most crucial in terms of building public trust. Faced with an unprecedented situation, several governments have tried the experimental approach, notably in a context marked by collective fear (Hafsi & Baba, 2022; Mercola & Cummins, 2021). From the generalized lockdowns, encouragement of large-scale vaccination despite an accelerated process of scientific testing of the impacts of vaccines, and mandating of the vaccine on employees of certain private companies and certain ministries to the imposition of a “sanitary pass” aimed at encouraging vaccination to deal with the multiple variants, the management of the pandemic generated major controversies (Kerkour, 2021; Koley & Dhole, 2021; Radio-Canada, 2021a).

Appendix 3. Analytical summary of the three controversies analyzed

Biographical notes

Sofiane Baba is Assistant professor of strategic management at the University of Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada. He holds a Ph.D. in strategy and organizational theory from HEC Montréal. His research focuses on the interface between organizations, society, and institutions, looking particularly at issues of change and strategic processes.

Jacqueline Dahan is Associate Professor of Management at the University of Sherbrooke, Quebec, Canada. She holds a Ph.D. in organizational theory from HEC-Montreal. Her recent research focuses on metaphors in strategic narratives and organizational annual reports.

Notes

-

[1]

We would like to thank Richard Déry, an outstanding thinker, for a stimulating discussion in 2013 which revealed the relevance of such a framework for understanding controversies in society.

-

[2]

The project management literature distinguishes between tangible (“hard”) and intangible (“soft”) projects (Crawfort and Pollack, 2004).

-

[3]

In their original theorization, Boltanski and Thévenot specify six worlds. Shortly thereafter, the green city was proposed by Thévenot and Lafaye (1993). In keeping with the argument of Patriotta, Gond, and Schultz (2011), we exclude the most recent of the worlds (project-based) because it is not yet theoretically established.

Bibliography

- Adkins, R. T. et Swan, J. E. (1982). Improving the Public Acceptance of Sales People Through Professionalization. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 2(1), 32-38. https://doi.org/DOI : 10.1080/08853134.1982.10754323

- Alaimo, K. (2018). Mark Zuckerberg has lost all credibility with Congress – and the rest of us. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2018/12/21/opinions/mark-zuckerberg-misled-congress-privacy-nyt-alaimo/index.html

- Alford, R. R. et Friedland, R. (1985). Powers of Theory: Capitalism, the State, and Democracy. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511598302

- Baba, S., Courcelles, R., & Dunn, M. (2022). Acceptabilité sociale : cinq bonnes pratiques à promouvoir. Gestion, 47(3), 39-42.

- Baba, S., Hemissi, O., Berrahou, Z., & Traiki, C. (2021). The Spatiotemporal Dimension of the Social License to Operate: The Case of a Landfill Facility in Algeria. Management International, 25(4), 247-266. doi:https://doi.org/10.7202/1083853ar

- Baba, S., Mohammad, S., & Young, C. (2021). Managing project sustainability in the extractive industries: Towards a reciprocity framework for community engagement. International Journal of Project Management, 39(8), 887-901. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2021.09.002

- Baba, S., & Raufflet, E. (2017). Acceptabilité sociale et projets de développement en Algérie: tendances, enjeux et expériences. In B. M’Zali, C. Hervieux, & M. M’Hamdi (Eds.), Un regard croisé d’experts et chercheurs sur la RSE: D’un contexte global au contexte de pays émergents (pp. 263-295). Montreal, Canada: Editions JFD.

- Baba, S. et Raufflet, E. (2014). Managing Relational Legacies: Lessons from British Columbia, Canada. Administrative Sciences, 4(1), 15-34.

- Baba, S., Sasaki, I. et Vaara, E. (2021). Increasing Dispositional Legitimacy: Progressive Legitimation Dynamics in a Trajectory of Settlements. Academy of Management Journal, 64(6), 1-46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2017.0330

- Baillargeon, S. (2021). Comment expliquer l’indiscipline sanitaire? . Le Devoir. https://www.ledevoir.com/societe/592772/coronavirus-comment-expliquer-l-indiscipline-sanitaire

- Baines, J. et Edwards, P. (2018). The role of relationships in achieving and maintaining a social licence in the New Zealand aquaculture sector. Aquaculture, 485, 140-146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2017.11.047

- Batellier, P. (2016). Acceptabilité sociale des grands projets à fort impact socio-environnemental au Québec: définitions et postulats. VertigO, 16(1). https://doi.org/DOI:10.4000/vertigo.16920

- Bobbish, D. (2014). Presentation on BAPE Hearings On Uranium. https://archives.bape.gouv.qc.ca/sections/mandats/uranium-enjeux/documents/MEM49.pdf

- Boiral, O., Heras-Saizarbitoria, I. et Brotherton, M.-C. (2019). Corporate sustainability and indigenous community engagement in the extractive industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 235, 701-711.

- Boltanski, L. et Thévenot, L. (1991). De la justification. Les économies de la grandeur. Gallimard.

- Bouie, J. (2020). Facebook Has Been a Disaster for the World. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/18/opinion/facebook-democracy.html

- Boutilier, R. G. et Thomson, I. 2011. The social license to operate. Dans P. Darling (Ed.), SME Mining Engineering Handbook: 673-690. Colorado: Society for Mining, Metallurgy, and Exploration.

- Boutilier, R. G. et Zdziarski, M. (2017). Managing stakeholder networks for a social license to build. Construction Management and Economics, 35(8-9), 498-513.

- Brandl, J., Daudigeos, T., Edwards, T. et Pernkopf-Konhäusner, K. (2014). Why French Pragmatism Matters to Organizational Institutionalism. Journal of Management Inquiry, 23(3), 314-318.

- Breviglieri, M. et Stavo-Debauge, J. (1999). Le geste pragmatique de la sociologie française. Autour des travaux de Luc Boltanski et Laurent Thévenot. Anthropologica, 7, 7-22.

- Bunnell, F. L. (1976). Forestry-Wildlife: Whither the Future. The Forestry Chronicle, 52(3), 147-149. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5558/tfc52147-3

- Castillo, M. d. (2019). Visa Exits Facebook’s Libra Cryptocurrency Group. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaeldelcastillo/2019/10/11/visa-exits-facebooks-libra-cryptocurrency-group/?sh=68fb683e275f

- CBC News. (2014, 28 octobre 2014). Cree leaders in Quebec use social media for campaign against uranium. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/cree-leaders-in-quebec-use-social-media-for-campaign-against-uranium-1.2809137

- Chenel, T. (2021). Les cryptomonnaies facilitent des activités criminelles et la fraude fiscale, insiste l’OCDE Business Insider France. https://www.businessinsider.fr/les-cryptomonnaies-facilitent-des-activites-criminelles-et-la-fraude-fiscale-insiste-locde-186754

- Cheung, A. T. M. et Parent, B. (2021). Mistrust and inconsistency during COVID-19: considerations for resource allocation guidelines that prioritise healthcare workers Journal of Medical Ethics, 47(2), 73-77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2020-106801

- Cloutier, C., Gond, J.-P. et Leca, B. (2017). Justification, Evaluation and Critique in the Study of Organizations: Contributions from French Pragmatist Sociology (vol. 52). Emerald.

- Cloutier, C. et Langley, A. (2013). The Logic of Institutional Logics: Insights From French Pragmatist Sociology. Journal of Management Inquiry, 22(4), 360-380.

- Costanza, J. N. (2016, Mar). Mining Conflict and the Politics of Obtaining a Social License: Insight from Guatemala [Article]. World Development, 79, 97-113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.10.021

- Crawford, L. et Pollack, J. (2004). Hard and soft projects: A framework for analysis. International Journal of Project Management, 22(8), 645-653.

- Cree Nation Government. (2020). Cree Nation Welcomes Court of Appeal’s Dismissal of Strateco’s Claim. https://www.cngov.ca/cree-nation-welcomes-court-of-appeals-dismissal-of-stratecos-claim/

- Criddle, C. (2020). Facebook sued over Cambridge Analytica data scandal. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-54722362

- Cruz, T. L., Matlaba, V. J., Mota, J. A. et Jorge, F. d. S. (2020). Measuring the social license to operate of the mining industry in an Amazonian town: A case study of Canaã dos Carajás, Brazil. Resources Policy. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101892

- Dalton, M. (2020). Facebook’s Diem: Will the Global Cryptocurrency Go Live in 2021? Bitrates. https://www.bitrates.com/news/p/facebooks-diem-will-the-global-cryptocurrency-go-live-in-2021

- Dave, A. (1972). Social Acceptability of the Systems Approach in Educational Planning Educational Technology, 12(2), 65-67. https://doi.org/https://www.jstor.org/stable/44417793

- Demers, C. et Gond, J.-P. (2020). The Moral Microfoundations of Institutional Complexity: Sustainability implementation as compromise-making at an oil sands company. Organization Studies, 41(4), 563-586. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840619867721

- Derakhshan, R. (2020). Building Projects on the Local Communities’ Planet: Studying Organizations’ Care-Giving Approaches. Journal of Business Ethics, 1-20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04636-9

- Déry, R., Pezet, A. et Sardais, C. (2020). Le management (2e éd.). Éditions JFD.

- Di Maddaloni, F. et Davis, K. (2018). Project manager’s perception of the local communities’ stakeholder in megaprojects. An empirical investigation in the UK. International Journal of Project Management, 36(3), 542-565. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2017.11.003

- Dionne, K.-E., Mailhot, C. et Langley, A. (2019). Modeling the Evaluation Process in a Public Controversy. Organization Studies, 40(5), 651-679. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840617747918

- Druckman, D. et Olekalns, M. (2011). Turning Points in Negotiation. Negotiation and conflict management research, 4(1), 1-7.

- Durand, R. et Thornton, P. H. (2018). Categorizing Institutional Logics, Institutionalizing Categories: A Review of Two Literatures. Academy of Management Annals, 12(2), 631-658. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.0089

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (2021). What is the Eisenhardt Method, really? Strategic Organization, 19(1), 147-160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127020982866

- Eisenhardt, K. M. et Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 25-32.

- Flick, U. 2018. Triangulation in Data Collection. Dans U. Flick (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection 527-544. London: SAGE.

- Fortin-Lefebvre, E. et Baba, S. (2021). Indigenous Entrepreneurship and Organizational Tensions: When Marginality and Entrepreneurship Meet. Management International, 25(5), 151-170. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7202/1085043ar

- Fournis, Y., Mbaye, O. et Guy, E. (2016). L’acceptabilité sociale des activités portuaires au Québec : vers une gouvernance territoriale? . Organisations & Territoires, 25(1), 21-30.

- France 24. (2021). Cinquième samedi de mobilisation en France contre le passe sanitaire. France 24. https://www.france24.com/fr/france/20210814-cinqui%C3%A8me-samedi-de-mobilisation-en-france-contre-le-passe-sanitaire

- Francoeur, L.-G. (2015). Les enjeux de la filière uranifèreau Québec: les enjeux de la filière uranifèreau Québec. https://archives.bape.gouv.qc.ca/sections/rapports/publications/bape308.pdf

- Galaway, B. (1984). A Survey of Public Acceptance of Restitution as an Alternative to Imprisonment for Property Offenders. Journal of Criminology, 17(2), 108-117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/000486588401700206

- Gehman, J., Lefsrud, L. M. et Fast, S. (2017). Social license to operate: Legitimacy by another name? Canadian Public Administration, 60(2), 293-317.

- Gendron, C. (2014). Penser l’acceptabilité sociale : au-delà de l’intérêt, les valeurs. Revue internationale Communication sociale et publique, (11), 117-129. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4000/communiquer.584

- Gond, J.-P., Cruz, L. B., Raufflet, E. et Charron, M. (2016). To Frack or Not to Frack? The Interaction of Justification and Power in a Sustainability Controversy. Journal of Management Studies, 53(3), 330-363.