Résumés

Abstract

The study of the multilingual character of multinational companies has grown into a legitimate field of research in international business. This paper provides a conceptualization of one of the central notions in this field: language diversity. We do this by relating the notion of language diversity to the concept of diversity in three dimensions: variety, separation or disparity. Our theoretical contribution is illustrated and further elaborated through a case study of multilingual team collaboration in the software industry. This paper explores the theory-building potential of stronger connections between diversity scholarship and the language research stream in international business.

Keywords:

- Diversity,

- Language,

- Language diversity,

- Language management,

- Multilingualism,

- Multinational Corporation

Résumé

L’étude de la nature multilingue des entreprises internationales est devenue un champ de recherche reconnu au sein du management international. Cet article propose une conceptualisation d’une notion centrale dans ce champ: la diversité linguistique. Celle-ci y est analysée sous les trois dimensions du concept de diversité: la variété, la séparation et la disparité. Cette contribution théorique de l’article est illustrée et développée plus en profondeur à travers l’étude de cas d’une équipe de travail multilingue dans l’industrie du développement de logiciels. Cette recherche explore les liens entre les recherches sur la diversité et sur le langage afin d’en consolider les fondements théoriques en management international.

Mots-clés :

- Diversité,

- Langues,

- Diversité linguistique,

- Management linguistique,

- Multilinguisme,

- Entreprise multinationale

Resumen

El estudio del carácter multilingüe de las empresas internacionales se ha convertido en un reconocido tema de investigación en el management internacional. Este artículo propone una conceptualización de una noción central en este ámbito: la diversidad lingüística. Este concepto es analizado bajo las tres dimensiones del concepto de diversidad: la variedad, la separación y la disparidad. Esta contribución teórica del artículo está más profundamente ilustrada y desarrollada a través del estudio del caso concreto de un equipo de trabajo multilingüe en la industria de desarrollo de programas informáticos. Esta investigación explora las relaciones entre las investigaciones sobre la diversidad y sobre el lenguaje a fin de consolidar los fundamentos teóricos del management internacional.

Palabras clave:

- Diversidad,

- lenguas,

- Diversidad lingüística,

- Management lingüístico,

- Multilingüismo,

- Empresa multinacional

Corps de l’article

“Dans les nouvelles problématiques nécessaires pour faire sortir la théorie des organisations de sa crise, …la réflexion sur le langage devrait être centrale.”

Jacques Girin, 2005, p.184

Workplace diversity has received increasing attention in the last four decades as a subject of research in management and organizational studies (Joshi & Roh, 2009). Much of this scholarship aims to improve our knowledge of the relationship between diversity and performance, which is to say, the relationship between differences in personal attributes among members of a work group – as well as people’s perceptions about them – and the processes and work outcomes in those units (Chanlat et al., 2013). The connections that researchers have been able to make between diversity and performance are tenuous, often contradictory, and moderated by organizational context (Bruna & Chauvet, 2013; Jackson et al., 2003; Kochan et al, 2003). There has been a call for closer study of the various types of diversity, based on the premise that different types of diversity may influence teamwork differently. Some types of diversity such as gender, racio-ethnicity and age have received considerable attention in the literature (Jackson et al., 2003) while other types of diversity, such as religion, social class, and language are only beginning to be studied in more detail (Jonsen et al., 2011; Gebert et al, 2014).

One of these types of diversity, language diversity, has been the focus of a growing area of scholarship in international business, in which multinational corporations have been described as inherently multilingual communities (Luo & Shenkar, 2006). Brannen and colleagues state that “as firms internationalize and enter new markets, whether as ‘born globals’ or more traditionally, they must navigate across countless language boundaries including national languages” (2014: 495). Language diversity is a particularly complex type of diversity in that it is profoundly anchored in both what people do (issues of skill and performance) and who they are (identity). A growing field of study has developed around this issue in the last 20 years (Piekkari et al., 2014). Case studies have brought to light some of the ways in which multinational companies have approached language management that multinational companies, ranging from a laissez-faire approach which allows employees to adapt their choice of language to the task at hand (Barmeyer & Mayrhofer, 2009) to the policy of adopting a common (national) language. The implementation of such policies can constitute a complex process of organizational change which fundamentally influences the institutional context and the relationships within it (Vaara et al, 2005; Neeley, 2013). A summary of the state of the art can be found in the recent editorial introduction to the special issue of the Journal of International Business Studies (Brannen et al., 2014).

Despite advances, this area of research faces several challenges. The field as a whole has been characterized as “a-theoretical and fragmented” (Harzing & Pudelko, 2013: 88). Scholars have pulled from a wide range of theoretical frameworks and disciplines to examine phenomena, and the field remains fragmented in terms of some of its central concepts: common language, language proficiency, corporate language, and language diversity. Precise definitions for these concepts are rarely given or compared, and close examination of the meaning that scholars denote with these terms reveals a certain degree of ambiguity. When the conceptualization of a notion such as language diversity varies from one study to the next, it is difficult to compare results and build a cumulative knowledge base. It hinders the debate of issues such as the costs and benefits associated with adopting a common national language in a multilingual work setting. When studying other kinds of diversity, scholars have developed nuanced conceptualizations and theoretical frameworks which are useful for analyzing the connections between diversity and organizational effectiveness. As of yet, the connections between diversity scholarship and the language research stream in international business have not been fully explored. We argue that there is potential here for theory-building that can enrich both streams. The language research stream in IB can benefit from the transposition of concepts and analytical frameworks that have already been developed about gender, racial, and ethnic diversity. For diversity scholarship, the case of language provides a particularly interesting type of diversity for testing existing theory. It is an interesting case because, as we assert here, the connections between diversity as skill, identity, and a power-conferring resource are particularly strong and salient.

We aim in this paper to clarify, specify, expand, and illustrate the concept of language diversity. The question driving our inquiry is: what is language diversity? To answer this question, we first look closely at the various meanings of the term “language diversity”. Then we examine the concept of language diversity in relation to a key conceptualization of diversity—the differentiation between three constructs: variety, separation, and disparity—and the related notions in language literature in IB: skills, identity, and power. This conceptualization is then illustrated and further elaborated by a case study of a multilingual marketing team in the business software development industry. Finally, we outline implications that this conceptualization of language diversity has for language management research and practice, and we discuss the limits of our approach and avenues for future research.

Conceptualization of Language Diversity

Definitions of “language” differ according to discipline and school of thought. For the purpose of this article, we consider in language to be a system for communicating thoughts and feelings that is understood by a particular community. Language can be considered one of the many human, material and symbolic resources that an organization mobilizes strategically in pursuit of its objectives (Girin, 2005). Language can be examined according to the different functions it serves (Jakobson, 1960) and, as applied to the case of organizations, consists of different dimensions (Tietze, 2008). In its descriptive dimension, language provides a symbolic sign system linking signs and meanings allowing categories and abstractions to be transferred across contexts. Language also serves a social function, establishing and maintaining relationships through social language acts. In this phatic dimension, the way in which things are said and the fact that they are said at all outweighs the importance of the verbal content. In its performative dimension, language does things; through its symbolic character promises are made, contracts are formed. Finally, language use normalizes certain practices and ideas, giving it a hegemonial dimension, a dimension of particular interest when considering the power dynamics in organizations (Tietze, 2008: 30).

Language Diversity and Layers of Language

Much of the research on language diversity in international business focuses on differences with respect to national languages. “National” languages are formally recognized and distinct semantic and lexical systems, such as English, Japanese or Swedish. (Of course, the boundaries of national languages rarely coincide neatly with political borders of nation-states.) In many articles, the concept of language diversity is equated with and limited to differences in national language. It is relevant and necessary to focus on national languages. However, if we are to fully understand the complex nature of language differences in a work setting, we argue in line with Welch et al. (2005) and Brannen et al. (2014) that it is also necessary to include other layers of language in the concept of language diversity. As a starting point, we adopt the following categorization of language layers proposed by Welch and colleagues (2005).

Closely linked to the notion of national language, everyday spoken and written language is the social language employed for interpersonal, interunit, and external communication (Welch et al., 2005). This layer of language, which would be readily understood by someone outside of the organization, has been shown to be crucial in building trust in teams (Kassis Henderson, 2005).

Company speak or corporate language is the language (vocabulary, meaning units, and pronunciation) used within a particular organization both among employees and with customers (De Vecchi, 2014). The day-to-day language of companies often results in idiosyncratic, firm-specific usages of words, phrases, acronyms, stories, or examples (Brannen & Doz, 2012). Such corporate language is used in strategy formation and in statements of strategic intent and corporate values (Brannen & Doz, 2012). Because this layer of language is not easy for newcomers and outsiders to understand, it may serve, whether intentionally or inadvertently, to distinguish members of the ingroup from members of the outgroup (De Vecchi, 2014). (This definition of corporate language differs from the notion that corporate language is the national language adopted by a company for internal and external communication.)

Like corporate language, technical or profession-related language is shared by a community of people, a group whose common denominator is not the organization for which they work but the job that they do or the profession they practice (Welch et al., 2005).

While language diversity is rarely defined explicitly in the literature, the conceptualizations used in international management research are often implicitly consistent with one or both of Lauring and Selmer’s (2010) definitions: ‘related to the number of languages spoken in the organization’ (p. 270) and ‘the presence of a multitude of speakers of different national languages in the same work group’ (p. 269). In other words, language diversity, or the language-related differences among people in a particular group or organization, can be defined in terms of 1) the language skills that each person in the unit individually possesses or 2) the languages actually utilized in the work environment. These definitions focus solely on national languages.

Conceptualizing language diversity as including but not limited to national language is important for several reasons. In the multinational organizational settings that are often the focus of research in IB, focusing only on diversity of national languages masks other language differences that could be salient and significantly influence work relationships. In the case of an international merger, for example, actors may deal with the confrontation of various sets of language practices that involve both national language and corporate language (Karamustafa, 2012). Taking both of these into consideration allows for a more precise analysis of where the challenges lie.

Moreover, by extending the concept of language diversity to include various layers of language, the knowledge developed through the theoretical and empirical work on language diversity in international business can also be seen as relevant to organizational contexts which may be ‘monolingual’ or low in diversity in terms of national language but in which actors may be dealing with differences in the other layers of language that may influence work relationships and performance. For example, one study has linked the experience of status loss to self-assessed levels of national language fluency (Neeley, 2013). This finding could be tested in a monolingual situation and might contribute to understanding the connection between employees’ sense of status and their mastery of the company’s corporate language.

A parallel can be drawn here between types of language and cultural spheres (Schneider et al., 2014) or layers (Chevrier, 2012). In the same way that cultural layers have been described as national/political, culture related to one’s profession, and corporate culture (Chevrier, 2013), language differences are not limited to differences in national language and layers of language are intricately connected. Commonality and difference among the different spheres may present not only barriers but also sources of leverage for teams and organizations. Scholars have asserted that organizational culture differences tend to be more disruptive than national culture differences (Sirmon & Lane, 2004), that a common organizational culture can be a source of leverage for overcoming national cultural differences (Chevrier, 2013), and that knowing how to navigate cultural differences and leverage benefits from them constitutes a valuable competency (Bartel-Radic, 2009). The same may be true for language. That is to say, a common organizational language, focusing less on national language per se than on the way in which things are said, such as in Brannen and Doz’s characterization of corporate language (2012), might be a source of leverage for overcoming communication barriers related to national language.

Language Diversity Constructs

Within diversity research, the conceptualization of interpersonal differences in a work group has evolved, leading the way for more precise studies on the relationships between diversity, team processes, and performance (Jackson et al., 2003; Joshi & Roh, 2009; Stahl et al., 2010). Studies of diversity have used a wide and varied range of constructs, types of research questions and empirical settings, and Harrison and Klein’s (2007) distinction between three specific diversity constructs – variety, separation, and disparity – has brought an important clarification to the field.

Key issues raised by IB scholars relate to various aspects of language, including: 1) skill - the notion of proficiency as a difference and its impact on how we communicate, 2) identity - the idea that language differences influence how we see the world and consider others to be similar or different from us, and 3) the issue of language as a resource which confers power and status.

We argue in this paper that these three issues are each related to one construct of diversity and that, therefore, language diversity can be conceptualized as any one of these constructs. In the current literature on language diversity, scholars consider language diversity from all three perspectives, often addressing more than one. Despite this, there is little discussion of how different the constructs and conceptualizations of language diversity under examination can be and what implications these differences might have for research and practice. By distinguishing these constructs, we intend to bring more clarity to the understanding of language diversity, allowing for closer examination of the interactions between them.

Language use and Skill Configuration: Language Diversity as Variety

The diversity as variety construct focuses on the composition of differences in kind, source, or category of relevant knowledge or experience among unit members (Harrison & Klein, 2007). The degree of diversity of a unit in terms of variety is defined by the diversity in the kinds of knowledge and experience present among unit members. This conceptualization of diversity as variety is generally adopted in studies of multifunctional or multicultural teams. Research has shown that a high degree of variety leads to outcomes like higher creativity and innovation but also higher task conflict (Adler, 2002). Moderate diversity has a tendency to lead to factions. Several studies on team diversity consider that diversity helps the team deal with the demands of greater complexity (Jackson et al., 2003; Lane et al., 2004). Scholars have drawn on the “law of requisite variety” (Ashby, 1956) to question ideal team composition, meaning an optimal diversity configuration and degree of diversity for a particular task (Bartel-Radic & Lesca, 2011).

In the field of international business, Lauring and Selmer’s (2010) definitions of language diversity (focusing on the number of different languages spoken / mastered in a unit) are consistent with a conceptualization of diversity as variety. Beyond the number of different languages, “language variety” includes differences in individuals’ language proficiency and experience. Language proficiency can be considered as a kind or source of relevant knowledge, whether the language be national language, corporate language, or the other layers of language mentioned above.

Minimum diversity in terms of variety would mean that individuals have a similar profile in terms of their language proficiency and experience. This could mean, for example, that they all speak the same native language, have a similar level of experience speaking a second language, and also are aligned in their use and understanding of the corporate language of the organization and the professional language of their job or function. Maximum diversity would exist in a group of people with very different language profiles, each with a different native language, each coming from different corporate and professional backgrounds and with different levels of experience working in language-diverse environments, as might be the case in an international and inter-organizational endeavor. When each person in the team has a different native language, the use of a common national language becomes a quite necessary option. However, in the case of moderate diversity, when several members of a group share a native language, there is a strong tendency to code-switch, using a common language with the larger group but reverting to one’s first language when the composition of a subgroup allows it. This practice that can hinder trust formation among team members (Harzing & Feely, 2008; Tenzer et al., 2014).

An analysis of the language diversity of a particular work group in terms of variety can serve in the process of taking stock of the various skills present and examining how those skills facilitate or hinder the accomplishment of common objectives.

Language, Identity, Attitudes, and Values: Language Diversity as Separation

The construct of diversity as separation focuses on the composition of differences in position or opinion among unit members, primarily of value, belief, or attitude (Harrison & Klein, 2007). Minimum diversity in terms of separation occurs when group members share attitudes and values about a particular issue – in other words, when group members share, at least to some extent, a common culture or sense of identity. Maximum diversity is a polarization between two groups with conflicting values. Such diversity has been shown to be significant in terms of team and organizational work. Organizational culture, including the values that are communicated to employees through practices and espoused values, has been found to moderate the relationship between diversity and group and organizational outcomes (Ely & Thomas, 2001; Van Dick et al., 2008).

We propose that language diversity can be conceptualized as separation in two ways. First, language is values-laden and can itself be both an artefact pointing to cultural values as well as a vehicle for transferring them. One way of understanding an organization’s identity is by examining its language, both the official and formalized language such as might be found in an official statement of corporate values and the language of day-to-day strategizing and decision-making (Rentz & Debs, 1987; Brannen & Doz, 2012). The language for describing a particular quality or value may have a positive connotation in one language and cultural context and a negative one in another (Brannen, 2004). Language related to branding and corporate values is often culturally embedded which makes the task of translating language from one national language context to another extremely challenging (Barmeyer & Davoine, 2013). The differences in language experience, whether it be national language or one of the other layers of language, inform the attitudes employees bring to a work context and may constitute a source of diversity.

A second way to conceptualize language diversity as separation lies in the diversity of attitudes and values about language. Individuals may differ in the values, beliefs, and attitudes they hold about language and language use, including attitudes towards accents and varying levels of proficiency (Lauring & Selmer, 2012) and individual affinity or aversion related to foreign language use. Several contributions have been made towards understanding how team members’ attitudes about language use affect collaboration. The use of particular languages may be experienced as a constraint and a source of stress, anxiety, or frustration (Vaara et al., 2005; Tenzer et al., 2014). Affinity for language-diverse work contexts can be part of an individual’s general attraction for the diversity found in international business environments (Stahl & Brannen, 2013). The degree of frustration experienced by expatriates in not being able to use their first languages and the pleasure derived from their competency in a home country language has been shown to be correlated to the length of expatriate stays (Usunier, 1998). Scholars have defined concept of ‘openness to linguistic diversity’ as individuals’ acceptance of each other’s varying language proficiency, vocabulary, and accents (Lauring & Selmer, 2012). This characteristic is positively associated with group knowledge processing (Lauring & Selmer, 2013).

The choice of which national language or languages to use in a particular setting can be seen as a negotiation motivated by underlying and sometimes conflicting values (Steyaert et al., 2011). For example, it might be considered ‘normal’, preferable, or inevitable to use a language associated with a particular geographical space or professional context. It might be judged polite to either adjust to the language of one’s conversation partner or to choose a third common language to avoid the imbalance of some speakers using their first language and other’s a foreign one. Some might advocate for inter-comprehension, allowing each person to speak and be understood in his or her own language (Barmeyer, 2008; Steyaert et al., 2011). The feasibility of these options depends on the language composition of the team, but also on the attitudes, values, and norms of individual teams members about language diversity. Skills and attitudes do not always coincide, a gap which can result, for example, in apologies for one’s lack of language proficiency, a sense of shame for an inability to perform what one considers to be ‘normal,’ desirable, or polite language behavior for a particular context.

An analysis of the language diversity of a work group in terms of separation can contribute to a greater understanding of the culture of the group with respect to language, that is to say, the values and attitudes motivating their practices.

Language, Power, and Status: Language Diversity as Disparity

The construct of diversity as disparity focuses on differences in proportion of socially valued assets or resources held among unit members (Harrison & Klein, 2007). Minimum disparity is an equal distribution of resources such as salary, bonuses, promotions, or other forms of power and status. Maximum disparity occurs when one unit member possesses considerably more of these resources with respect to his or her colleagues. Even though some scholars have looked at the degree to which power is shared with “diverse” individuals (ex. Ely & Thomas, 2001), studies treating diversity as disparity remain rare in the organizational literature (Harrison & Klein, 2007). However, in IB, power dynamics related to diversity of national languages have been the subject of considerable research (ex. Davoine, Schröter & Stern, 2014; Hinds, Neeley & Cramton, 2014; Neeley, 2013; Piekkari et al., 2005; Vaara et al, 2005).

To understand the language diversity of a team or organization in terms of disparity, it is necessary to understand not only the various language skills that members of those groups possess but also the value of those skills in that particular context (Blommaert et al., 2005). The very same combination of language skills may be essential to a person’s professional success in one context and yet, in another, may not only be of very little value but may even be a hindrance. In terms of professional language, we can give the example of the academic research language in business. Mastery of specific vocabulary and stylistic conventions is a precious resource for being accepted by research communities. On the other hand, the same linguistic prowess may not only have less value but may even be considered an obstacle to communicating one’s research findings to some readers who are turned off by language they consider to be too abstract or theoretical to be relevant or useful (Kelemen & Bansal, 2002).

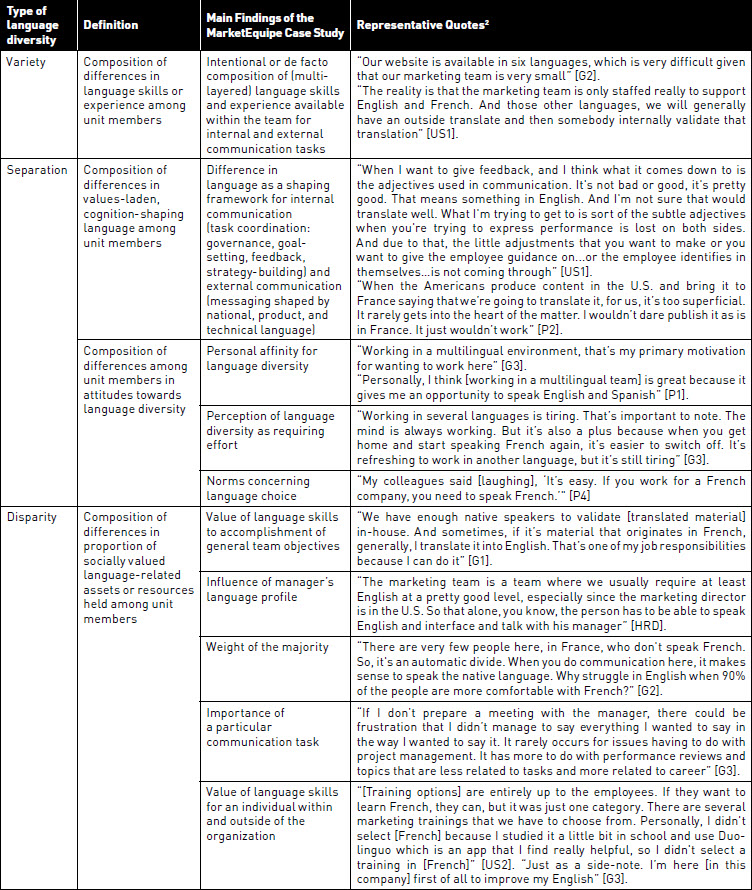

Table 1

Diversity constructs of variety, separation, or disparity applied to language diversity

Table 2

Role and Geographical Location of Interviewees

Minimum disparity in terms of language diversity would consist of low differentiation in language-related status among individuals in a group or organization either because individuals have similar language skills or because differing levels of language proficiencies in that particular work context do not result in increased power or status for the people who have them. Maximum disparity would be strong differentiation among members in the distribution of power and status related to language proficiency. Rapidly changing language contexts, such as in the case of some mergers and acquisitions, show the connections between language and power with particular clarity. Individuals may have the same national and corporate language skills before and after the merger, but the change in context significantly affects the power and resources available to them as a function of their language skills. Attention to language diversity as disparity can lead to a better understanding of the language-related power dynamics in a group.

A summary of this section is presented in Table 1. The conceptualization of language diversity as it has been developed in the first part of this paper is further illustrated and elaborated through the case study presented in part two.

Method: Qualitative Case Study Research

This study was conducted in the context of a research project on the management of language diversity in teams and organizations. For the purpose of this paper, we adopt single case study methodology as a way of illustrating and further elaborating the conceptualization above concerning types of language diversity. Case study methodology allows for examining a phenomenon in its naturalistic context with the purpose of confronting theory with the empirical world (Piekkari, Welch, & Paavilainen, 2009). This research can be characterized as “intermediate theory research” as it draws from prior work and separate bodies of literature to propose new constructs and provisional theoretical relationships (Edmondson & McManus, 2007: 1165).

Focusing on a single case allows for an up-close examination of the language diversity of one team in an international company and for concentrating on rich description of the context (Dyer & Wilkins, 1991). The team chosen, referred to hereafter as MarketEquipe, presents a rich exemplary case due to its multilingual characteristics both in the composition of national and other layers of language and due to its function in the company of generating marketing messages and content, an activity in which the role of language is particularly central.

Data was collected in 2014 through interviews and observation. In-depth, semi-structured interviews of approximately one hour were conducted with nine of the ten team members. An interview with the director of human resources provided additional insight into language dynamics at the broader organizational level. The careful consideration of these ten perspectives on the marketing team’s language diversity allowed for data source triangulation (Denzin, 1978).

The MarketEquipe team is located three different sites, in Grenoble and Paris in France, and in San Francisco, California. Interviews with team members of the Grenoble office were conducted on-site which allowed for observation of that work environment and informal exchanges with team members. The other interviews were conducted by videoconference. Participation in an off-site team event three months after the interviews was helpful for confirming and further orienting our initial findings. The roles and geographical location of the employees interviewed as well as the language in which the interviews took place is given in Table 2.

Recorded and transcribed, interview data was coded using content analysis and the Atlas.ti software as an interface. The interview data was first coded according to the two conceptualizations developed above: layers of language and the diversity constructs of variety, separation, and disparity. A second phase of analysis aimed to more closely examine both the contents of the data classified into each of one of these categories and the overlap and relationships between them (Dumez, 2013; Dubois & Gadde, 2002).

The Market Equipe Case

“MarketEquipe” is the ten-member marketing team of a French tech start-up in business software development industry. Its function within the organization, as described by the team’s manager, is to build demand for the product and identify potential customers for the sales team. Team members contribute to this common goal in various capacities (see Table 2), including technical product expertise, regional specialization, website development, and graphic design. The team is geographically dispersed with two colleagues in San Francisco, California, one of them being the team’s manager (the company’s marketing vice president), both of U.S. nationality, three colleagues in Grenoble, France (one U.S. American expatriate, one Indian expatriate, one French national), and five colleagues in Paris (one Chinese expatriate, one Spanish expatriate, and three French nationals). The case study is presented here following the structure of the theoretical framework, in terms of variety, separation / identity and disparity / power.

Language Variety in MarketEquipe: a Multi-layered, Multilingual Composition of Differences

MarketEquipe is diverse in terms of the “native” languages represented (French, English, Mandarin Chinese, Spanish, and English/Hindi). Through their educational and professional experiences, team members have acquired various degrees of fluency in other national languages. The languages that team members actually utilize in this work environment are primarily limited to French and English, with Spanish used occasionally among some members.

Corporate Language Policy

The company’s language policy for external communication defines English, French, and Spanish as ‘priority one’ languages; communication with customers in these languages is fully supported. German, Italian, and Portuguese are considered ‘priority two’ languages. Some marketing content and customer training are provided to a lesser extent in these languages. In addition to the fact that there are no native speakers of these ‘priority two’ languages on the marketing team, the native Spanish speaker, a graphic designer, was hired for his visual arts talents. His skill profile and job focus are not considered to be well-adapted to translating or generating written language content in Spanish. Consequently, the national language capacity of the team as is does not allow for fulfilling the language needs generated by the policy for external communication in six languages.

MarketEquipe fills this gap by externalizing some of the content translation and localization work, an approach which comes with its own set of challenges. As the team’s manager says “the nature of language makes translation hard” [US1]. The complexity and specificity of the product language requires investment in the relationship with the translation service provider. “We’ve committed to one [translation agency] at this point because we’re trying to spend a lot of time with them to get them up to speed, build a term base, a knowledge base and really educate them on how to use phrasing for our market and our software” [US1]. Translations are then validated internally, either by marketing team members when the translations are in English or French or by staff members outside of the marketing team, often sales representatives, for the other languages.

Communication within the team

In terms of internal communication within the team, the use of English and/or French varies according to the people involved in the interaction. When the monolingual English manager needs to take an active role in the interaction, English is generally chosen. However, for communication that only involves native French-speakers in the team, French is used. What becomes a bit more complex is the choice of language among native French speakers and the members of the team who have varying levels of proficiencies in French. As one team member described it, “When [US1] and [US2] are not there, but [G2] involved, it’s English. If [G2]’s not involved, it can be in French. Sometimes I request that it be in English, but if the native English speakers are not involved and they start in French, we continue in French” [G1]. The choice of language adopted seems to depend on the language composition of the sub-group, individuals’ level of skill and comfort, and personal preferences, as will be discussed in the following section on diversity as separation.

Even if most team members of MarketEquipe located in France are comfortable with the use of English, language variety can cause misunderstandings. As one interviewee in this study mentioned, “Where [the meaning] gets lost in language is in the nuance, the fine-tuned nuance. I’ve had employees tell me that they’re mad at me. Ok, you know...I’m not sure you’re really mad at me. I think there’s probably a more complex phrasing of that, but it’s lost in the language barrier.” [US1]. To bridge communication barriers, at the time of the interviews, MarketEquipe was testing a shared dashboard tool to facilitate communication about task progress and workload. Team members mentioned that the visual representation provided support for better communication.

Language Separation in MarketEquipe: Language and Identity

In the MarketEquipe case, we see evidence of language differences in connection with issues of identity in the two aspects of language diversity as separation described above. First, value- and concept-laden language serves to both express ideas and shape cognition in the team. Secondly, differences with respect to team members’ attitudes and values toward language diversity influence team collaboration.

Value-laden Language and tTam Cognition

In this case, national and corporate languages shape cognition and influence team practices, particularly with respect to governance, communicating objectives, and strategy-building. At the time of the interviews, MarketEquipe was testing a new flat management approach to governance called holacracy. With this managerial initiative came new language for team coordination, based on “circles,” or sub-groups within the team to which particular responsibilities were assigned, as opposed to a more traditional top-down hierarchy and designation of individuals responsible for specific marketing functions. Language is a vehicle for communicating values; here, they are the values of democratic functioning and abundant communication to which the manager subscribed. The language of the new organization is audible in the way team members describe their tasks, mentioning how they worked before and after holacracy was implemented. The lack of clarity and assurance with which team members described their new roles indicates that the language of the new organization has not yet been fully adopted. (We later learned that the team returned to a more traditional system of governance within six months after the interviews.)

Language diversity can be considered to be both a facilitator and a hindrance in terms of strategy development. Crossing language boundaries sometimes slows the communication process and necessitates increased attention to language. One advantage of this, as cited by one team member [G3], is the increased time that allowed everyone to contribute their point of view by email. On the other hand, there is a concern that the language diversity is a barrier to the development of sophisticated marketing strategy. “One of my fears […] is that we’re not having as advanced and complex conversations as we should be having and that it’s dumbing down what we’re challenging ourselves to do on the marketing team because we feel like we’re blocked by a language barrier” [US1].

Values about language(s) and team collaboration

Concerning our second approach to language diversity as separation, a variety of attitudes about language diversity were expressed by members of the MarketEquipe team. Attitudes concerning three themes were particularly salient, including: 1) personal affinity for language diversity, 2) perception of language diversity as requiring effort, 3) norms concerning language choice.

In terms of identity and interpersonal similarity as a cohesive force in the formation of groups and sub-groups, national and corporate language are influential. However, team members’ attitudes toward language also seem to serve as a strong force. An appreciation for the necessity of language diversity in accomplishing business tasks can be an aligning force among team members, independent of whether their language profiles are monolingual or multilingual.

Language Disparity in MarketEquipe: Power and the Value of Language Skills

MarketEquipe’s task, generating clear and compelling marketing messages, is very much a language-dependent activity. A high level of language skills in French and English is recognized by the manager and by team members as a valuable component for task accomplishment. This importance is also reflected in the HR department’s recruitment process. Interviews take place in English as well as French for the employees who are not native English-speakers.

A closer look reveals nuances as to which language skills are considered most valuable and actually confer status and power in this particular context. These nuances are related to 1) the value of language skills in accomplishing general team objectives, 2) the influence of the manager’s language profile, 3) the weight of the majority in geographical subgroups, 4) the importance of the particular communication task, and 5) the added value of the language skills for individual team members beyond the immediate team collaboration.

First of all, the manager’s language profile heavily influences the language dynamic. In this case, a monolingual English-speaker with a high level of expertise in the professional language of marketing for business software was hired as the manager of this multilingual team. MarketEquipe differs from the other teams and departments in the company in that it is the only one with a native English-speaker as a manager. This influences the language dynamics of the team considerably. It pushes English as a default choice of national language for interaction in any situation in which the manager is actively involved.

When interactions do not involve the manager directly, the weight of the majority is a significant influence in according value to language skills. This is seen in the choice of language for the geographical subgroups of the MarketEquipe. In Paris, among the three native French speakers and two non-native French speakers, French is generally used. In Grenoble, among the two native English speakers and one native French speaker, English is used.

With the general context of the team, the value of language skills also depends on the stakes of a particular task being performed. For example, in the interviews, several team members mentioned the annual performance review as a moment when mastery of the manager’s national, business management and everyday negotiation language is particularly valuable.

Finally, the value that team members place on certain language skills and their motivation for improving their individual proficiency in that language seems to be dependent on the perceived added value of those skills beyond the immediate team collaboration, such as for future professional opportunities. Several native French-speakers described working in English as a valuable opportunity to practice and hone their business English skills. Non-native French-speakers in the Paris and Grenoble offices described opportunities to improve their French in a similar way. However, for the two native English-speakers in the U.S. office, increasing their French skills was not viewed as an opportunity in which they were seeking to invest.

Table 3

Summary of Case Study Findings

These findings about MarketEquipe’s language diversity as variety, separation and disparity are summarized in Table 3.

Discussion

The findings from the MarketEquipe case study contribute to the conceptualization of language diversity by highlighted and illustrating three points: 1) the need to consider supplementary layers of language, 2) the interconnected nature of the three types of language diversity (variety, separation and diversity), and 3) the potential for diversity scholarship contributing to a better understanding language management as diversity management.

A Need for the Consideration of Supplementary Language Layers

With respect to language layers, we have seen some examples in this study of how the notion of national language is connected to corporate and professional layers of language. Our results also suggests that this conceptualization might need to be expanded to include other layers of language that are not already mentioned by Welch et al. (2005), notably language for discussing emotions, visual language, and meta-language for communication management.

Language for discussing emotions, referred to as “talk” by Von Glinow and colleagues, can be particularly challenging for multilingual teams (2004). It has been suggested that one way for multilingual teams to overcome language barriers, including barriers related to the expression of emotion, is to find ways to supplement, or even bypass, word-based communication through a more intentional use of other forms such as visual representation (Kostelnick, 1988; Von Glinow et al., 2004). This approach can be seen in the MarketEquipe manager’s habit of following up a conversation or meeting with an email summary. Although still word-based and still in English, utilizing written communication provides a visual complement to support the oral exchange. Additionally, visual representation, such as MarketEquipe’s shared dashboard, can contribute to bridging verbal communication barriers.

Finally, meta-communication (Bateson, 1972), “communication about communication”, is a layer of language that appears from this study to merit inclusion. In describing the processes used by the team for working across language barriers, several interviewees mentioned the phrases and questions used to clarify meaning, such as, “I don’t understand. Could you repeat that?” or “Is this what you mean…?” or “How can I say this in English?” [G3]. Proficiency in meta-communication enhances a person’s intercultural competence, meaning the ability to deal with cultural diversity (Bartel-Radic, 2009). Likewise, it seems to be an indicator for a team’s ability to manage language diversity. Training in this layer of language might provide support for teams facing language challenges. As studies on language diversity more systematically include various layers of language as objects of study, more knowledge will be generated as to what these layers are and how they interact.

The Interconnected Nature of Diversity Types

The findings of the study also bring to the forefront the interconnected nature of different types of language diversity. In fact, the exact boundaries between them can be blurry and challenging to discern. (For example, an employee’s description of language skills as valuable for a particular work context involves the notion of separation as well as disparity. It involves an attitude about language use as well as the notion of status.) It is precisely at these boundaries and intersections, however, where we see theory-building potential and a promising research agenda. In our experience with various teaching and training organizations in international management and in our contact with practitioners, we have seen that the focus on language is all too often limited to skills at the individual level, what we have described in this paper as variety. If we limit our understanding of language diversity in organizations to variety, we could be missing some important, game-changing elements. To explain this further, we give three examples of the interaction of language diversity constructs as they might occur in a work setting. 1) If a company, when hiring new employees, pays attention only to applicants’ national language abilities and not to their affinity for or willingness to use foreign languages in the workplace, team performance might end up being hindered by employees who are able but reluctant to communicate in a particular language. 2) If managers of international teams are not aware of the power dynamics associated with adopting and/or imposing a particular language for a team interaction, whether it be a national or corporate language, they may risk alienating certain team members who are less proficient in that language, employees who might then disengage and contribute less to the organization. 3) The value that an organization explicitly and implicitly places on certain language skills might also influence employees’ motivation for increasing their individual proficiency in those languages. These examples indicate a necessity for a nuanced and comprehensive approach to language management that goes beyond language diversity as variety.

Welch and Welch (2015: 3) have recently developed the concept of “Language Operative Capacity” (LOC), defined as “language resources that have been assembled in a form that the multinational enterprise can apply, in a productive, context-relevant manner, as and when required throughout its global network”. We argue that building this capacity depends on a comprehensive understanding of language diversity as variety, separation, and disparity. Language management entails not just managing skills but managing language diversity. As we explain in the section below, diversity scholarship can further contribute to building theory on language management as diversity management.

Language Management as Diversity Management: Mutual Enrichment of Two Research Streams

We consider that diversity scholarship, through its concepts and its models, can contribute to a better understanding of language management as diversity management. We outline these here as a way of extending the contribution of this article and proposing avenues for future research.

First, theory on language in IB can be further developed by transposing concepts from diversity scholarship. As an example of this transposition, Dotan-Eliaz and colleagues (2009) have applied the notion of ostracism to language in order to articulate the concept of linguistic ostracism — how a group of people intentionally uses a national language in which other people in the unit have low or no proficiency — as well as its opposite, linguistic inclusion. Below are four concepts that we think could be transposed to language in particularly compelling ways: 1) double standard (Abrams et al., 2013: 799) in which people’s threshold for acceptable language proficiency may vary according to which language is being spoken, their own or a “foreign” language, or who is speaking it, 2) discrimination (Ely & Thomas, 2001) in which an employee might be treated unfairly due to his or her language profile as a personal characteristic, 3) “requisite variety” of an intercultural team (Bartel-Radic & Lesca, 2011), which we can apply to language to investigate whether there is an ideal diversity configuration for a team or organization, depending on its tasks, and 4) intercultural competence (Bartel-Radic, 2009), the notion that a person’s ability to successfully negotiate language differences in interpersonal interactions constitutes what we might refer to as interlingual competence.

Secondly, several models have been proposed in diversity scholarship to better understand the relationships between diversity, diversity management, and organizational effectiveness (ex. Kochan et al., 2003; Van Dick et al., 2008; Tran, Garcia-Prieto & Schneider, 2011). Transposing these models to the specific case of language diversity might generate new insight into what constitutes effective language diversity management. It might also serve to test and further develop the initial models in diversity scholarship. For example, diversity scholarship encourages the examination of the ways in which the value that diversity brings to teams or organizations is moderated by employees’ attitudes and beliefs about diversity (van Dick et al., 2008). Our findings in this study point to the need to decouple language skills from language attitudes and examine the precise relationships between them. It is possible for an employee to have a monolingual language profile, appreciate the value of national language diversity for team effectiveness, and implement language management practices that support communication in a language-diverse environment. (Multilingual team members might find this somewhat contradictory, however, and believe that if an organization really values language diversity, it would hire multilingual managers into top positions.) As a corollary to this argument, the ability to speak several national languages, in itself, provides no guarantee of sensitivity and know-how with respect to language issues in business. Future research might investigate precisely what characteristics and skills in a manager are associated with successful leadership of a multilingual team.

To summarize, we suggest that the transposition of diversity concepts and models to the specific case of language constitutes a potentially fruitful way forward for theory-building in both the language research stream in IB and in diversity scholarship.

Conclusion

The primary contribution of this paper is a more comprehensive conceptualization of language diversity. By examining the notion of language differences against the backdrop of the key diversity constructs of variety, separation, and disparity, we propose the following definition of language diversity: differences among members of a work unit that are related to various layers of language (i.e. national, corporate, technical/professional, visual, language for expressing emotions, meta-communication). These differences can be considered in terms of 1) skills within that particular system of communication, 2) identity- and cognition-shaping frameworks, and 3) resources of varying social usefulness about which people may hold differing attitudes and values. This conceptualization is illustrated and elaborated through a case study of the language diversity of one particular team. This methodological choice allows for a close-up view of the intricacies of language diversity but can be seen as a limit to our approach. Future studies comparing examples of language diversity configurations in teams and organizations (and their respective effectiveness) could certainly be beneficial for developing a more fully illustrated typology.

On our effort to separate out and distinguish the three types of language diversity from one another, we can see the extent to which they are interconnected and, at times, overlapping, a point which could be considered a limitation to the proposed framework. As suggested above, we believe that it is precisely at the points of overlap and interconnectedness where it would be interesting for future studies to focus and where diversity scholarship can be valuable to the IB research stream.

In terms of managerial implications of this work, the conceptualization developed here constitutes a framework for managers and consultants investigating the language dynamics of a team or organization. One can understand the language diversity in a work context, not just in terms of language skills but also in terms of identity and power, thereby arriving at a more fine-tuned and comprehensive inventory of the language dynamics at play.

Parties annexes

Biographical notes

Amy Church-Morel is a teacher at the IAE University Savoie Mont Blanc and a PhD candidate at the IREGE research center in France. Her doctoral research focuses on language diversity and the coordination of international teams. She is a member of the GEM&L board of directors (Groupe d’Etudes management & Langage) and has presented papers at this association’s annual conference as well as at ATLAS-AFMI and AIMS.

Anne Bartel-Radic is a full professor in business administration at Institut d’Etudes Politiques of Grenoble, and a researcher at CERAG, Université Grenoble Alpes, France. As a German living in France, she has been interested for years in management of cultural diversity, and in intercultural competence of people and organizations. Her research in the field of intercultural management has been published, among others, in Management International, Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, Management International Review and Recherches en Sciences de Gestion.

Bibliography

- Abrams D, De Moura GR, Travaglino GA (2013) A Double Standard When Group Members Behave Badly: Transgression Credit to Ingroup Leaders. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 105 (5), 799–815.

- Adler N (2002) International dimensions of organizational behavior. Cincinnati, South-Western.

- Ashby WR (1956) Introduction to cybernetics. London, Chapman and Hall.

- Barmeyer C (2008) La gestion des équipes multiculturelles. In Waxin MF & Barmeyer C, Gestion des Ressources Humaines Internationales. Rueil-Malmaison, Editions Liaisons, 249-290.

- Barmeyer C, Davoine E (2013) ‘Traduttore, Traditore?’ La réception contextualisée des valeurs d’entreprise dans les filiales françaises et allemandes d’une entreprise multinationale américaine. Management international, 18 (1): 26–39.

- Barmeyer C, Mayrhofer U (2009) Management Interculturel et Processus d’Intégration: une Analyse de l’Alliance Renault-Nissan, Management & Avenir, 22: 2, 109–131.

- Barner-Rasmussen W, Aarnio C (2011) Shifting the faultlines of language: A quantitative functional-level exploration of language use in MNC subsidiaries. Journal of World Business, 46 (3), 288–295.

- Bartel-Radic A (2009) La compétence interculturelle: état de l’art et perspectives. Management International, 13 (4), 11-26.

- Bartel-Radic A, Lesca N (2011) Requisite Variety and Intercultural Teams: To What Extent is Ashby’s Law Useful? Management International, 15 (3), 89-104.

- Bateson G (1972) Steps to an ecology of mind, New-York: Ballantine.

- Blommaert J, Collins J, Slembrouck S (2005) Spaces of multilingualism. Language & Communication, 25 (3), 197–216.

- Brannen MY (2004) When Mickey Loses Face: Recontextualization, Semantic Fit, and the Semiotics of Foreignness. Academy of Management Review, 29 (4), 593-616.

- Brannen MY, Doz YL (2012) Corporate Languages and Strategic Agility: Trapped in your Jargon or Lost in Translation? California Management Review, 54 (3), 77-97.

- Brannen MY, Piekkari R, Tietze S (2014) The multifaceted role of language in international business: Unpacking the forms, functions and features of a critical challenge to MNC theory and performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 45 (5), 495–507.

- Bruna MG, Chauvet M (2013) La Diversité, un Levier de Performance: Plaidoyer pour un Management Innovateur et Créatif, Management International, 17 (special issue), 70-84.

- Chanlat JF, Dameron S, Dupuis JP, de Freitas ME, Özbilgin M (2013) Management et Diversité: lignes de tension et perspectives, Management International, 17 (special issue), 5-13.

- Chevrier S (2012) Gérer des Equipes Internationales: Tirer Parti de la Rencontre des Cultures dans les Organisations, Quebec: Presses de l’Université de Laval.

- Chevrier S (2013) Managing Multicultural Teams. inChanlat JF, Davel E & Dupuis JP, Cross-Cultural Management: Culture and Management across the World, New York: Routledge, 203–223.

- Davoine E, Schröter OC, Stern J (2014) Cultures régionales des filiales dans l’entreprise multinationale et capacités d’influence liées à la langue: une étude de cas. Management international, 18 (special issue): 165–177.

- De Vecchi D (2014) Company-Speak: An Inside Perspective on Corporate Language. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 33 (2), 64–74.

- Denzin NK (1978) The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Dotan-Eliaz O, Sommer KL, Rubin YS (2009) Multilingual Groups: Effects of Linguistic Ostracism on Felt Rejection and Anger, Coworker Attraction, Perceived Team Potency, and Creative Performance. Basic & Applied Social Psychology, 31 (4), 363–375.

- Dubois A, Gadde LE (2002) Systematic combining: an abductive approach to case research. Journal of Business Research, 55 (7): 553–560.

- Dumez H (2013) Méthodologie de la recherche qualitative: les 10 questions clés de la démarche compréhensive. Paris: Vuibert.

- Ely RJ, Thomas DA (2001) Cultural diversity at work: The effects of diversity perspectives on work group processes and outcomes. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46 (2), 229–273.

- Gebert D et al. (2014) Expressing religious identities in the workplace: Analyzing a neglected diversity dimension. Human Relations, 67 (5), 543–563.

- Girin J (2005) La Théorie des Organisations et la Question du Langage, in Borzeix A, Fraenkel B, Langage et Travail: Communication, Cognition, Action, Paris: CNRS Editions, 167-183.

- Harrison DA, Klein KJ (2007) What’s the difference? Diversity constructs as separation, variety, or disparity in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32 (4), 1199–1228.

- Harzing AW, Feely AJ (2008) The language barrier and its implications for HQ-subsidiary relationships. Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 15 (1), 49–61.

- Harzing AW, Pudelko M (2013) Language competencies, policies and practices in multinational corporations: A comprehensive review and comparison of Anglophone, Asian, Continental European and Nordic MNCs. Journal of World Business, 48 (1), 87–97.

- Hinds P, Neeley T, Cramton C (2014) Language as a lightning rod: Power contests, emotion regulation, and subgroup dynamics in global teams. Journal of International Business Studies, 45 (5), 536–561.

- Jackson SE, Joshi A, Erhardt NL (2003) Recent Research on Team and Organizational Diversity: SWOT Analysis and Implications. Journal of Management, 29 (6), 801–830.

- Jakobson R (1960) Closing statements: Linguistics and Poetics, Style in language. New-York: T.A. Sebeok.

- Jonsen K, Maznevski ML, Schneider SC (2011) Diversity and its not so diverse literature: An international perspective. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 11 (1), 35–62.

- Joshi A, Roh H (2009) The role of context in work team diversity research: A meta-analytic review. Academy of Management Journal, 52 (3), 599–627.

- Karamustafa G (2012) Learning through mergers and acquisitions: the processes during post-merger integration. PhD thesis: Université de Genève.

- Kassis Henderson J (2005) Language diversity in international management teams. International Studies of Management and Organization, 35 (1), 66–82.

- Kelemen M, Bansal P (2002) The conventions of management research and their relevance to management practice. British Journal of Management, 13 (2), 97–108.

- Kochan TK et al. (2003) The Effects of Diversity on Business Performance: Report of the Diversity Research Network. Human Resource Management, 42 (1), 3-21.

- Kostelnick C (1988) A systematic approach to visual language in business communication. Journal of Business Communication, 25 (3), 29–48.

- Lane HW, Maznevski ML, Mendenhall M, McNett J (2004) Handbook of Global Management. A Guide to Managing Complexity. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Lauring J, Selmer J (2010) Multicultural organizations: Common language and group cohesiveness. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 10 (3), 267–284.

- Lauring J, Selmer J (2012) International language management and diversity climate in multicultural organizations. International Business Review, 21 (2), 156–166.

- Lauring J, Selmer J (2013) Diversity attitudes and group knowledge processing in multicultural organizations. European Management Journal, 31 (2), 124–136.

- Luo Y, Shenkar O (2006) The multinational corporation as a multilingual community: Language and organization in a global context. Journal of International Business Studies, 37 (3), 321–339.

- Neeley T (2012) Global Business Speaks English. Harvard Business Review, 90 (5), 116–124.

- Neeley T (2013) Language Matters: Status Loss and Achieved Status Distinctions in Global Organizations. Organization Science, 24 (2), 476–497.

- Piekkari R, Vaara E, Tienari J, et al. (2005) Integration or disintegration? Human resource implications of a common corporate language decision in a cross-border merger. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16 (3), 330–344.

- Piekkari R, Welch D, Welch, L (2014) Language in International Business: The Multilingual Reality of Global Business Expansion. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Rentz KC, Debs MB (1987) Language and Corporate Values: Teaching Ethics in Business Writing Courses. Journal of Business Communication, 24 (3), 37–48.

- Schneider SC, Barsoux, JL, Stahl GK (2014) Managing across cultures. London: Pearson.

- Sirmon DG, Lane PJ (2004) A model of cultural differences and international alliance performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 35 (4), 306-319.

- Stahl GK, Brannen MY (2013) Building Cross-Cultural Leadership Competence: An Interview with Carlos Ghosn. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 12 (3), 494–502.

- Stahl GK, Maznevski ML, Voigt A, Jonsen K (2010) Unraveling the effects of cultural diversity in teams: A meta-analysis of research on multicultural work groups. Journal of International Business Studies, 41 (4), 690-709.

- Steyaert C, Ostendorp A, Gaibrois C (2011) Multilingual organizations as ‘linguascapes’: Negotiating the position of English through discursive practices. Journal of World Business, 46 (3), 270–278.

- Tenzer H, Pudelko M, Harzing A-W (2014) The impact of language barriers on trust formation in multinational teams. Journal of International Business Studies, 45 (5), 508–535.

- Tietze S (2008) International Management and Language. London / New York: Routledge.

- Tran V, Garcia-Prieto P, Schneider SC (2011) The role of social identity, appraisal, and emotion in determining responses to diversity management. Human Relations, 64(2): 161–176.

- Usunier JC (1998) Oral pleasure and expatriate satisfaction: an empirical approach. International Business Review, 7 (1), 89–110.

- Vaara E, Tienari J, Piekkari R, et al. (2005) Language and the circuits of power in a merging multinational corporation. Journal of Management Studies, 42 (3), 595–623.

- Van Dick R, van Knippenberg D, Hagele S, et al. (2008) Group diversity and group identification: The moderating role of diversity beliefs. Human Relations, 61 (10), 1463–1492.

- Von Glinow MA, Shapiro DL, Brett JM (2004) Can we talk, and should we? Managing emotional conflict in multicultural teams. Academy of Management Review, 29 (4), 578–592.

- Welch D, Welch L (2008) The importance of language in international knowledge transfer. Management International Review, 48 (3), 339–360.

- Welch D, Welch L, Piekkari R (2005) Speaking in tongues: the importance of language in international management processes. International Studies of Management and Organization, 35 (1), 10–27.

- Welch, D., Welch, L (2015) Developing multilingual capacity: A challenge for the multinational enterprise, Journal of Management, in press.

Parties annexes

Notes biographiques

Amy Church-Morel est enseignante à l’IAE Savoie Mont Blanc et doctorante au sein du laboratoire IREGE. Sa recherche porte sur la diversité linguistique et la coordination des équipes internationales. Elle est membre du conseil d’administration du GEM&L (Groupe d’Etudes Management et Langage), et a présenté ses travaux aux colloques annuels de cette association, ainsi qu’à ATLAS-AFMI et à l’AIMS.

Anne Bartel-Radic est professeur des universités en Sciences de Gestion à l’Institut d’Études Politiques de Grenoble et chercheur au CERAG, Université Grenoble Alpes, en France. Allemande vivant en France, elle s’intéresse depuis des années au management de la diversité culturelle et à la compétence interculturelle des personnes et des organisations. Ses recherches dans le champ du management interculturel ont été publiées, entre autres, dans Management International, Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, Management International Review et Recherches en Sciences de Gestion.

Parties annexes

Notas biograficas

Amy Church-Morel es profesora en el IAE de la Universidad Saboya Mont Blanc y prepara su Doctorado en el laboratorio IREGE. Su tema de investigación trata sobre la diversidad lingüística y la coordinación de equipos internacionales. Es miembro del consejo de administración del GEM&L (Grupo de estudios de gestión y lenguas), y ha presentado sus trabajos en coloquios anuales de esta asociación así como en ATLAS-AFMI et à l’AIMS.

Anne Bartel-Radic es profesora en administración de empresas del Institut d’Etudes Politiques de Grenoble, e investigadora en el CERAG (Universidad de Grenoble). De origen alemán, actualmente radicada en Francia, sus principales centros de interés por años han sido la gestión de la diversidad cultural, y la competencia intercultural de personas y organizaciones. Sus investigaciones en el campo de la gestión intercultural han sido publicadas, entre otras, en Management International, Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, Management International Review y Recherches en Sciences de Gestion.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Diversity constructs of variety, separation, or disparity applied to language diversity

Table 2

Role and Geographical Location of Interviewees

Table 3

Summary of Case Study Findings

10.7202/038582ar

10.7202/038582ar