Résumés

Abstract

In this paper, we study the reverse U-shaped relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and firms’ use of equity capital. Using a large sample of U.S. publicly listed companies, we provide strong evidence that CSR is positively associated with the use of equity capital when CSR practices are below a certain level. Once the CSR investment exceeds this level, the relationship between CSR and the equity financing becomes negative. Our findings are robust when we use the individual components of CSR, and several approaches to address endogeneity. Overall, our results enrich the debate about capital structure of high CSR firms and suggest that the CSR-capital structure relationship is more complex than what has been demonstrated in previous literature.

Keywords:

- Corporate Social Responsibility,

- Capital Structure,

- Corporate Governance,

- Agency Theory

Résumé

Nous étudions la relation en U inversé entre la responsabilité sociale des entreprises (RSE) et leur financement par capitaux propres. Nos estimations économétriques effectuées sur la base d’un large échantillon de sociétés américaines cotées montrent que la RSE est positivement associée à l’utilisation des fonds propres lorsque les pratiques RSE sont inférieures à un certain niveau. Quand l’engagement RSE dépasse ce niveau, la relation entre la RSE et le choix des capitaux propres devient négative. Nos résultats sont robustes lorsque nous utilisons les différentes dimensions individuelles de la RSE et plusieurs approches pour corriger une éventuelle endogénéité. Nos résultats contribuent au débat sur la structure du capital des entreprises socialement responsables et fournissent de nouvelles contributions empiriques et managériales.

Mots-clés :

- Responsabilité Sociale des Entreprises,

- Structure du Capital,

- Gouvernance d’Entreprise,

- Théorie d’Agence

Resumen

Estudiamos la relación en forma de U invertida entre la responsabilidad social corporativa (RSC) y su financiación mediante equidad. Nuestras estimaciones econométricas basadas en una gran muestra de empresas estadounidenses que cotizan en bolsa muestran que la RSC se asocia positivamente con el uso de equidad cuando las prácticas de RSC están por debajo de cierto nivel. Cuando el compromiso de RSC de las empresas supera este nivel, la relación entre RSC y la elección de la equidad como fuente de financiación se vuelve negativa. Nuestros resultados son sólidos cuando utilizamos las diferentes dimensiones individuales de la RSC y varios enfoques econométricos para corregir la posible endogeneidad. Nuestros resultados contribuyen al debate sobre la estructura de capital de las empresas socialmente responsables y proporcionar nuevas contribuciones empíricas y prácticas.

Palabras clave:

- Responsabilidad social empresarial,

- Estructura capital,

- Gobierno corporativo,

- Teoría de la Agencia

Corps de l’article

Research on capital structure of high Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) firms shows a linear relationship between CSR[1] and the use of equity capital over debt (e.g., Hong and Kacperczyk, 2009; Verwijmeren and Derwall, 2010; Benlemlih, 2017). However, very little attention is paid to the non-linear relationship that may exist between the two variables. In this paper, we fill this gap in the literature. We argue that the economic intuition indicates a non-linear link between CSR and the use of equity capital. Our study offers insights into the potentially important role of a non-linear relationship to explain the link between CSR and firms’ characteristics.

There are several reasons a firm’s CSR involvement may affect its financing decisions. First, as outside monitors, lenders and investors may discriminate between firms with superior CSR activities and those with lower CSR engagement. For instance, Hong and Kacperczyk (2009) highlight the existence of societal norms against operations addressed to finance “sin activities”. Second, a firm’s CSR activities may be viewed from a risk management perspective. A firm with higher CSR activities could have lower risk (e.g., Benlemlih and Girerd-Potin, 2017; Benlemlih and Peillex, 2019; Peillex et al., 2019; Viviani et al., 2019). Consequently, firms with positive private information about their future risk and credit ratings will signal that information to the market by financing their activities with more equity capital as they have access to low cost of equity capital. Finally, Godfrey (2005) discusses the possibility of overinvestment issues related to CSR i.e., corporate insiders might overinvest in CSR to improve their own reputation. Debt is likely to play a monitoring role, as firms have to disclose information about all their activities. Thus, when CSR activities exceed a certain level, it is likely to become a source of conflict between insiders and outsiders, and investors are likely to divest such firms. Accordingly, CSR activities could eventually be negatively associated with the use of equity.

Based on the above-mentioned arguments, we expect a reverse U-shaped relationship between firms’ CSR activities and the use of equity capital. To investigate this reverse U-shaped relationship, we obtain firms’ CSR data from MSCI ESG STATS, the most extensive database on firms’ CSR activities that has been widely used in prior literature (e.g., Bae et al., 2011; Bae et al., 2018; Di Giuli and Kostovetsky, 2014; Hillman and Keim, 2001; Servaes and Tamayo, 2013; Sharfman, 1996).

We mobilize a sample of 21,116 firm-year observations, representing more than 2,000 individual US firms between 1998 and 2012, and after controlling for previous determinants of firm’s capital structure and industry and year fixed effects, we provide strong evidence on a reverse U-shaped relationship between CSR and the use of equity capital. An increase of one standard deviation in the CSR score increases the use of the ratio of shareholders’ equity to total asset by 0.5%. Whereas, an increase of one standard deviation in the CSR score squared reduces the use of equity to total assets by 1.3%.

One might argue that the control variables included in the regression model moderate the relationship between CSR and firms’ financing decision. The analysis of our research question through different sub-samples provide complementary findings and shows that, overall, the CSR-capital structure relationship is not driven by the control variables included in the regression models.

Further, our study’s results may suffer from endogeneity. On the one hand, the use of an OLS regression does not take into consideration that firms are likely to choose their level of long-term debt and shareholders’ equity simultaneously. On the other hand, it is possible that reverse causality or omitted firm-level factors that affect both firm’s capital structure and the CSR strategy are driving our results. To remedy this issue, we first use a system of two simultaneous equations, recognizing that long-term debt is determined endogenously with shareholders’ equity. Second, we re-estimate the regressions from our main analysis using an instrumental variables approach. Third, we employ a Heckman self-selection approach that correct for self-selection bias. All these specifications’ results indicate that our main findings are not driven by the simultaneous choice of equity and long-term debt nor reverse causality or omitted firm-level factors.

Our work contributes to the existing literature in several ways. First, this is the first attempt to investigate the reverse U-shaped relationship between CSR and firm’s use of equity capital. Prior studies in the field mainly focus on the linear relation between CSR and capital structure and argue that CSR is either positively or negatively related to the use of equity capital (e.g., Hong and Kacperczyk, 2009; Verwijmeren and Derwall, 2010; Bae et al., 2011; Cheng et al., 2014). Our work goes a step further and highlights the complexity of this relationship. Second, our study’s findings corroborate, to a certain extent, those of Nollet et al. (2016). Nollet et al. (2016) provide evidence of a U-shaped relationship between CSR and the accounting-based measures of financial performance. The authors argue that CSR expenditures pay off only after a threshold of CSR activities has been reached. While Nollet et al. (2016) focus on the link between CSR and financial performance either from an accounting or a market perspectives as opposed to our work that treats capital structure, our respective findings clearly show that studies on CSR should focus more on the non-linear set up. Further, the respective findings also confirm our claims on the existence of a relevant level of CSR that determines the CSR-capital structure (respectively, the CSR-financial performance) relationship. Finally, our paper significantly complements corporate finance literature. Previous studies focusing on firms’ characteristics that affect capital structure have mainly addressed largely studied factors such as information asymmetry (e.g., Fulghieri and Lukin, 2001), national culture (Zheng et al., 2012), and corporate governance (Granado-Peiró and López-Gracia, 2017). The extent to which CSR affects financing choices remains, however, an ongoing debate that needs further investigation. Our findings thus fulfil this gap in the literature and shows that social activities could play an important role in determining firm’s capital structure.

Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

Firm’s capital structure is one of the most studied topics in corporate finance. It aims to show the optimal particular combination of debt and equity used to finance the overall operations growth. We propose to briefly discuss capital structure theories relevant to our study before presenting our hypothesis discussion.

Theories of Financing

Modigliani and Miller (1958) argue that, in a capital market that does not include imperfections but rational investors, capital structure has no impact on firm value. Nevertheless, it is likely that the financial market shows some imperfections, and investors some irrationality. That’s being said, prior literature considers the financial market frictions, and research on capital structure has provided insights for new financing theories, including, pecking order and trade-off theories.

In a market with information asymmetry, the use of debt and equity financings would be impacted by the information costs. Myers and Majluf (1984) argue that the adverse selection costs associated with information asymmetry are likely to prevent the equity issuance. Firms have tendency to issue securities that are less informationally sensitive. The pecking order theory consequently predicts the financing order: first, firms use internal funds, then issue debt (short-term followed by long-term debt), and finally equity as a last choice.

From a trade-off perspective, the firm identifies its optimal capital structure and makes the choice between leverage and equity financings by comparing the costs and benefits of an additional dollar of debt. Those benefits are multiple and mainly include tax savings and an optimal management of free-cash-flow to avoid agency problems. At the opposite, the costs of debt mainly consider the cost related to the firm’s financial distress on the one hand, and the agency conflicts between shareholders and bondholders on the other hand.

Hypothesis Development

The theoretical discussion of capital structure of high CSR firms has evolved tremendously in the last few years due to the large core of literature. Both the stakeholders’ theory and the resources-based theory predict that equity investors consider CSR activities to be relevant for firm’s value. The value-increasing effect of CSR would consequently create an additional demand from investors and would have a significant impact on the choice of equity financing over debt financing.[2] The equity market has recently shown a spectacular increase in investor demand for CSR investments (e.g., Peillex and Ureche-Rangau, 2016; Benlemlih and Cai, 2019; El Ouadghiri et al., 2019). Indeed, firms with high CSR performance adopt a proactive approach and disclose additional financial and extra-financial information. High CSR firms are likely to be honest, trustworthy and ethical in all their corporate practices. Their social involvement is expected to reflect ethical concerns and lead to more transparency through additional financial and extra-financial reporting. With lower information costs, a firm’s capital structure is expected to have more informationally sensitive securities as shown in the pecking-order theory earlier. Further, CSR firms are known to have a long-term business approach and are expected to generate low payoff on the short run. Thus, according to the trade-off model, high CSR involvement’s firms would give more importance to bankruptcy risk when setting their capital structure.[3] Taken together, high CSR firms are likely to use more equity over debt in their capital structure.

From an empirical perspective, prior studies also provide evidence that CSR firms are likely to use more equity over debt. Kim et al. (2012) empirically demonstrate that high CSR firms are less likely to be involved in earnings management, real operating activities manipulation, or subject to SEC investigations. Dhaliwal et al. (2011) also show that social and environmental information reduces errors in financial analysts’ forecast and increases firm’s transparency. Firms with low interest in CSR activities are also less likely to be followed by financial analysts as highlighted in the study of Hong and Kacperczyk (2009) who clearly state that “sin stock” are less closely followed by analysts and the media. Given that, high CSR firms are less likely to face information asymmetry (e.g., Dardour and Husser, 2016; Husser and Evraert-Bardinet, 2014), Baker and Wurgler (2002) state that they are likely to operate with more equity. Baker and Wurgler (2002)’s results are strengthened by recent literature on the link between CSR and the cost of equity capital. For instance, Sharfman and Fernando (2008) empirically demonstrate that firms with better environmental risk management have lower cost of equity capital. Investors are subsequently willing to accept low investment return when they are investing in environmentally firms. El Ghoul et al. (2011) provide additional support for these findings by using a large sample of U.S. publicly listed firms. Firms with better CSR ranking as measured by MSCI ESG STATS exhibit cheaper equity financing as measured by an ex ante cost of equity. El Ghoul et al. (2011)’ results are in accordance with those of Ng and Rezaee (2015) that use similar sample but different empirical approach and confirm that CSR performance reduces the cost of equity capital. Finally, Feng et al. (2015) mobilize an international sample from 25 countries and provide additional support for the negative relationship between CSR and the cost of equity. In summary, we expect that a firm’s CSR influences its capital structure which is consistent with our hypotheses:

H1: CSR is positively associated with the use of equity, i.e. ratio of shareholders’ equity to total assets.

Yet, the theoretical framework suggested previously is not conclusive and could be discussed from the agency view of CSR (Friedman, 1972). Indeed, most research on CSR only tests for a linear relationship between CSR and firm’s characteristics. However, recent developments in micro-economic theory rather suggest a non-linear set-up (e.g., García-Gallego and Georgantzis, 2009; Manasakis et al., 2013, 2014; Nollet, et al., 2016). Although a non-linear relationship between CSR and firm’s capital structure is in line with economic intuition, it has rarely been tested (Nollet et al., 2016). As in Barnett and Salomon (2012, 2006), firms that voluntarily engage in more CSR activities incur higher corresponding costs; therefore, firms with higher CSR scores have invested more financial resources in CSR comparing to those with lower CSR. CSR could thus be a source of value destruction as opposite to what has been stated in the first hypothesis. Barnea and Rubin (2010), Godfrey (2005) and Brown et al. (2006) argue that insiders may tend to increase firms’ social activities (and, consequently, financial expenditures related to social activities) to a level higher than that which maximizes firms’ value and reduce the cost of equity capital. This line of literature states that CSR activities are likely to be a source of value creation when the CSR investment does not exceed a certain level. However, once the CSR investment exceeds that level, it only benefits for insiders without creating any additional value for the firm. Barktus et al. (2002) show that shareholders tend to limit corporate philanthropy expenditures to certain level when they do not have certitude about the real motivation of management to invest in such activities. If we accept the above-mentioned arguments, we should expect a positive relationship between CSR and the use of equity capital up to a certain level of CSR, however, once the CSR activities exceed that level, investors are less interested in investing in those firms and the relationship between CSR and the use of equity capital becomes negative. Further, when the CSR involvement exceeds this certain level, outsiders consider it as a source of value destruction (Barnea and Rubin, 2010). In this case, corporate finance theory documents evidence for an increase of the fraction of the firm capital structure financed by debt over equity. As highlighted by Jensen (1986), debt commits the firm to pay out cash and thus, would reduce the amount of free cash available for managers to engage in CSR activities that are beyond those which are relevant for the firm and the society as a whole. Debt financing is likely to substitute equity financing in the case of overinvestment in CSR due to agency conflict between managers and outsiders. We thus extend the linear relationship discussed in hypothesis 1 and incorporate a quadratic relationship that may exhibit a reverse U-shaped. We formulate the second hypothesis as follow:

H2: A reverse U-shaped relationship is expected between firm’s CSR score and the proportion of shareholders’ equity in its capital structure.

Data and Research Design

Sample Selection

In order to study the capital structure of high CSR firms, our sample is drawn from two main databases: Compustat, which provides financial information, and MSCI ESG STATS (formerly known as KLD STATS), which we use to obtain CSR data. We first begin by considering all firms from Compustat with non-missing financial information. We next retain observations with sufficient available data to construct our dependent and control variables data. We exclude financial firms (Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codes between 6000 and 6999) because they have different investment behaviour due to regulation (e.g., Price and Sun, 2017). Finally, we match the Compustat sample with MSCI ESG STATS. The final sample contains 21,116 observations representing more than 2,000 US individual firms between 1998 and 2012. All industries are well represented with a strong concentration of manufacturing industries that represent 50% of our sample. Other industries such as services, transportation and communication or retail trade have also a good representation in the sample.

Regression Variables

CSR Data

To measure a firm’s CSR performance, our sample is based on MSCI ESG STATS, a database compiled by MSCI ESG Research and its forerunner, KLD Research & Analytics Inc.[4] MSCI ESG STATS has been extensively used in academic research on CSR (e.g., Bae et al., 2011; Bae et al., 2018; Di Giuli and Kostovetsky, 2014; Hillman and Keim, 2001; Servaes and Tamayo, 2013; Sharfman, 1996). MSCI ESG STATS aims to assess seven qualitative issue areas that include community, diversity, employee relations, environment, product characteristics, human rights, and corporate governance. Each dimension includes strengths and concerns with a binary system (0/1) for every strength and concern. We utilize these scores and compute an overall CSR score based on six different CSR areas, i.e. community, diversity, employee relations, environment, human rights, and product characteristics.[5] For each qualitative area, we calculate a score that is equal to the number of strengths minus the number of concerns. We next sum these scores to obtain the overall CSR score (CSR_NET). This approach is widely used in the CSR literature (e.g., Bae et al., 2018; Benlemlih and Bitar, 2016; El Ghoul et al., 2011).

Dependent Variable

To measure capital structure, we rely on studies on firm’s capital structure and use the ratio of shareholder’s equity to total asset (based on accounting variables) as our main dependent variable. First, the ratio is widely employed in the literature on firms’ capital structure (e.g., Rajan and Zingales, 1995; Verwijmeren and Derwall, 2010), using this variable helps us compare our findings with other studies on the relationship between CSR and capital structure. Second, as discussed in the theoretical section of our paper, our focus is on the link between CSR and the use of equity capital as CSR has been shown to reduce the cost of equity capital and this reduction would have an impact on the use of equity capital over debt by CSR firms. While this argument could also justify the use of the equity over debt ratio, we don’t think this is a relevant measure in our context as it would be difficult to distinguish between the effect of CSR on equity or debt financing.

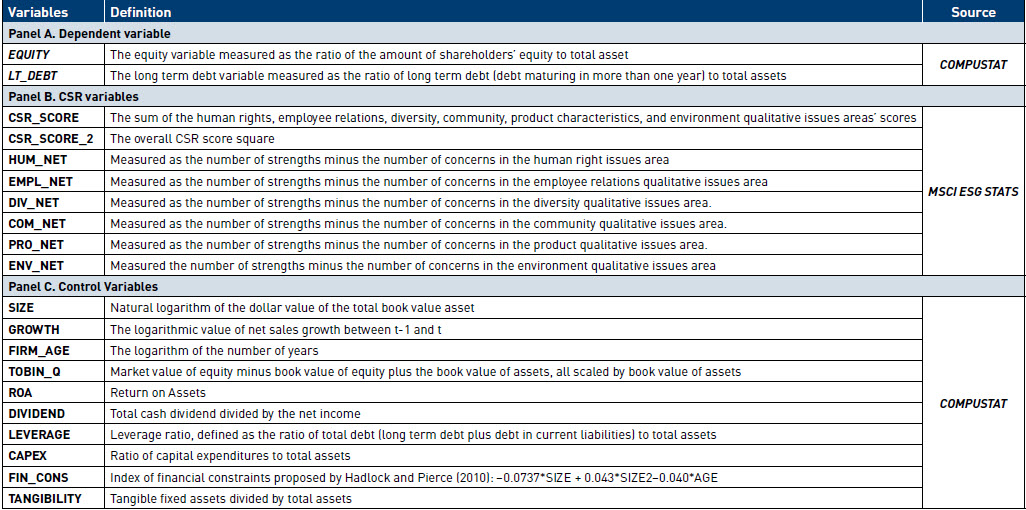

Control Variables

Following previous literature that has studied firm’s capital structure in similar context (e.g., Hong and Kacperczyk, 2009; Verwijmeren and Derwall, 2010; Bae et al., 2011; Barclay and Smith 1995; Johnson, 2003), we include control variables to better isolate the effect of CSR on firm’s capital structure. The control variables improve comparability with prior studies and reduce the possibility that capital structure is a function of correlated omitted variables. We consequently use as a proxy of firm size (SIZE) the natural logarithm of total book value of assets. Firm’s growth (GROWTH) is measured by the logarithmic value of net sales increase (log of sales at date t to sales at date t-1). Firm’s age (FIRM_AGE) is measured as the natural logarithm value of the number of years between fiscal year and Compustat listing year. We include Tobin’s Q (TOBIN_Q) as the market value of equity minus the book value of equity plus the book value of assets, all scaled by the book value of assets. We measure return on assets (ROA) by the ratio of EBITDA to total assets. We calculate dividend payout (DIVIDEND) as the ratio of cash dividend to net income. Firm’s leverage (LEVERAGE) is measured as the ratio of the book value of total liabilities and debt scaled by the book value of total assets. Capital expenditure (CAPEX) is measured as the ratio of capital expenditures to total assets. In accordance with Cheng et al. (2014) and Farre-Mensa and Ljungqvist (2016), we also include an index of financial constraints (FIN_CONS) as proposed by Hadlock and Pierce (2010)[6]: −0.0737*SIZE+ 0.043*SIZE2−0.040*AGE. We also control for asset tangibility (TANGIBILITY) calculated as the ratio of tangible fixed assets to total assets.

Finally, we include two additional dummy variables that control for the industry (based on the two-digit SIC codes) and year fixed effects: YEAR and INDUSTRY.[7]

Descriptive Statistics

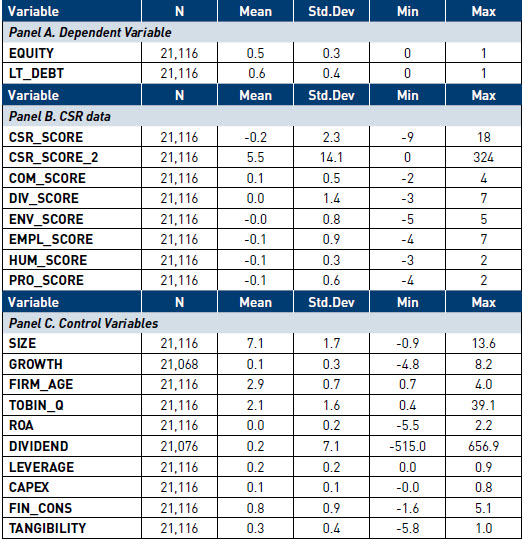

Panel A of Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics for the main dependent variables of the study while Panel B shows the descriptive statistics for the CSR variables.

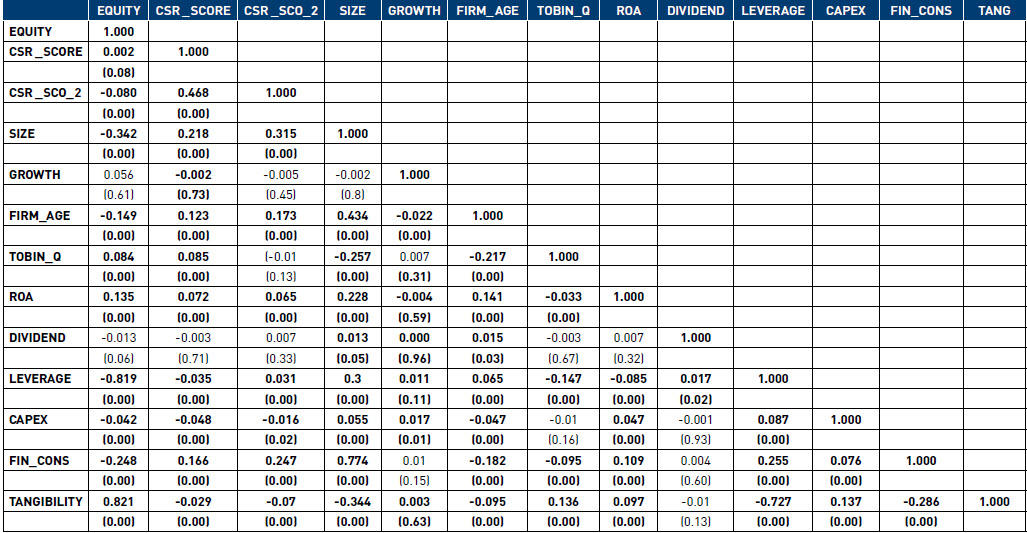

Table 2 shows the Pearson correlation coefficients between all the variables. As expected, the dependent variable is highly related to our explanatory variables, providing insurance about the relevance of these controls. More relevant for our purpose, the dependent variable is positively correlated with the overall CSR score and negatively correlated with the overall CSR score squared (at the 5% significance level or better). Finally, we do not find high correlation coefficients between the control variables from our study, and the VIF coefficient is around 1.20 providing insurance that multicollinearity is not a concern in our context.

Empirical evidence

The overall CSR Score and Firm Capital Structure

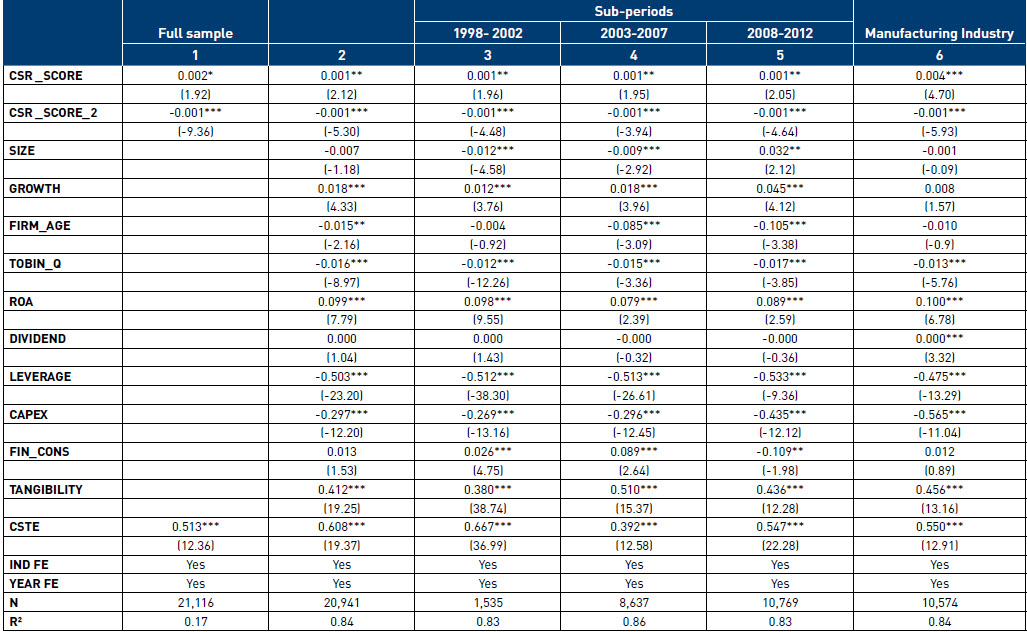

In this section, we establish the nonlinear relation between CSR and firms’ financing decisions. We regress the ratio of shareholder’s equity to total assets on CSR variables using ordinary least squares (OLS) without taking into account the control variables. Our results from Model 1 Table 3 shows that the overall CSR score coefficient is positively and significantly related to the dependent variable and the overall CSR score squared is negative and statistically significant providing support for our expectation in the hypotheses section.

Model 2 of Table 3 reports the results from the regression that includes all the control variables as suggested by the literature and discussed above. The CSR coefficient loads positive and statistically significant at the 5% significance level, while the CSR squared coefficient loads negative and statistically significant at the 1% significance level.[8] These results are consistent with our expectation from the hypotheses section. The relationship between CSR and firm’s capital structure is a reverse U-shaped relation: firms that have high CSR performance enjoy low cost of equity capital, which, consequently, leads to high use of shareholders’ equity. However, once the CSR performance exceeds certain level, the relationship between CSR and the part of capital financed by shareholder’s equity becomes negative.

Turning to the control variables included in the model, we document several significant relationships as found in previous literature. (e.g., Hong and Kacperczyk, 2009; Verwijmeren and Derwall, 2010; Bae et al., 2011). For instance, high profitable firms (ROA) with high access to cash (GROWTH), and high tangibility of asset (TANG) tend to use more equity over debt since the cost of equity is lower for those firms. On the other hand, older firms (FIRM_AGE), with high Tobin’s q (TOBIN_Q) and high capital expenditures (CAPEX) are negatively and significantly associated with the use of equity capital. Finally, the coefficient of leverage (LEVERAGE) loads negative and statistically significant providing evidence for the negative correlation between equity and debt financing.

The Overall CSR Score and Firm Capital Structure: on The Effects of the Control Variables

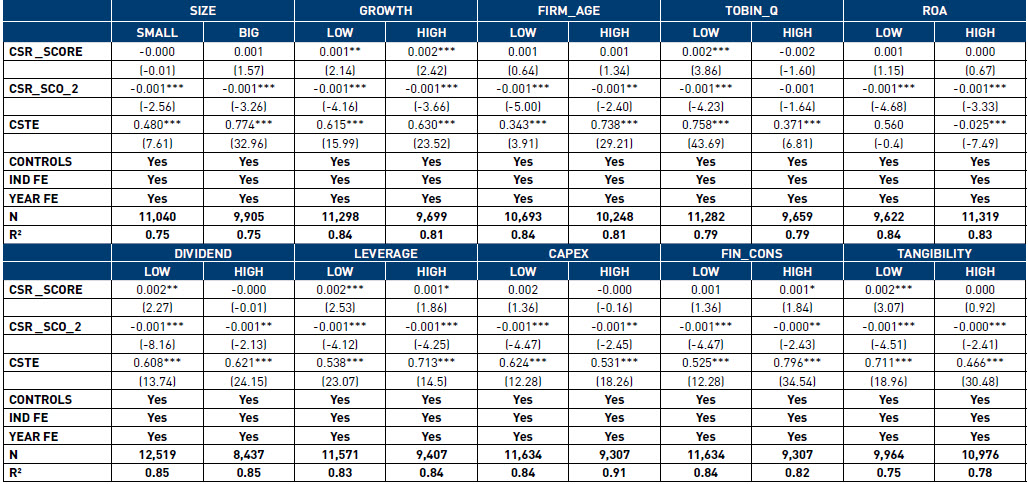

One might argue that the control variables included in the regression model moderate the relationship between CSR and firms’ financing decision. We thus extend the framework of our study by taking into account differences in firm’s characteristic, namely, size, growth opportunities, firms’ age, return on asset, dividend, firm’s leverage, capital expenditures, financial constraints and asset tangibility. More precisely, we run our analyses on the two sub-samples from each control variable as determined by the median of each.

Table 4 reports the results from this analysis. First, we notice that for most of the control variables (size, growth, firm’s age, return on assets, firm’s leverage and capital expenditures), there is no difference between the CSR (the CSR squared) coefficients through the two sub-samples either H1 and 2 are validated or not.

Second, for three control variables, we document the same findings as our main analysis only in one sub-sample. On the one hand, we document a non-linear relationship between CSR and the use equity capital in low Tobin’s Q firms. Low Tobin’s Q firms are likely to have less financial performance as compared to high Tobin’s Q. If this is true, low Tobin’s Q firms are expected to use their CSR activities in order to signal their quality and have access to the equity market. This is likely to explain why the relationship between CSR and the use of equity capital is only significant with low Tobin’s Q firms. On the other hand, in firms that pay fewer dividends, we document a reverse U-shaped relationship between CSR and the use of equity capital, whereas in high dividend payout firms we only document a non-linear relationship. Low dividend payout firms have high cash in place and the ability to invest in CSR activities based on management’s decisions. This is likely to explain the same behaviour as in our main analysis. On the other side, high dividend payout may be due to agency conflict as suggested by Easterbrook (1984). In this case, CSR activities are perceived as value destructive which explain the negative coefficient on CSR squared. Finally, we notice similar results with the tangibility of assets. We report a reverse U-shaped relationship between CSR and the use of equity capital in low tangibility of assets firms, whereas in high tangibility firms, we only found a non-linear relationship. Low tangibility firms are known to be more involved in CSR activities (service providing firms). CSR is expected to negatively affect the cost of equity and the excessive investment may have similar results as documented in our main analysis. High tangibility firms are less exposed to CSR pressure and high CSR involvement could be perceived as destructing firm’s value, which explains the negative association found between CSR squared and the use of equity capital.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics for regression variables

This table presents descriptive statistics for the variables of the 21,116 firm-year observations between 1998 and 2012. All the variables are defined in Appendix A.

Table 2

Correlation coefficients

The table presents the correlation coefficients between the variables. Figures between parentheses represent the p-values from the correlation study. Figures in bold are significant at the 5% significance level.

Table 3

Corporate social responsibility and the use of equity capital

This table reports results from regressing the equity variable on the overall CSR score and control variables over the 21,116 firm-year observations of the sample. The dependent variable is the amount of shareholders’ equity to total asset. The overall CSR score is calculated from the six individual CSR scores as provided by MSCI ESG. The control variables used in the regressions are described in the appendix. All the models include year and industry fixed effects. Appendix A outlines the definitions for all the regression variables. Robust t-statistics based on Newey-West standard errors are presented in parentheses.

* statistical significance at the 10% level ** statistical significance at the 5% level. *** statistical significance at the 1% level.

Taken together, this additional analysis tends to indicate that the relationship between CSR and capital structure documented in our main analysis is not substantially driven by differences in control variables.

Individual Components of CSR and Firm Capital Structure

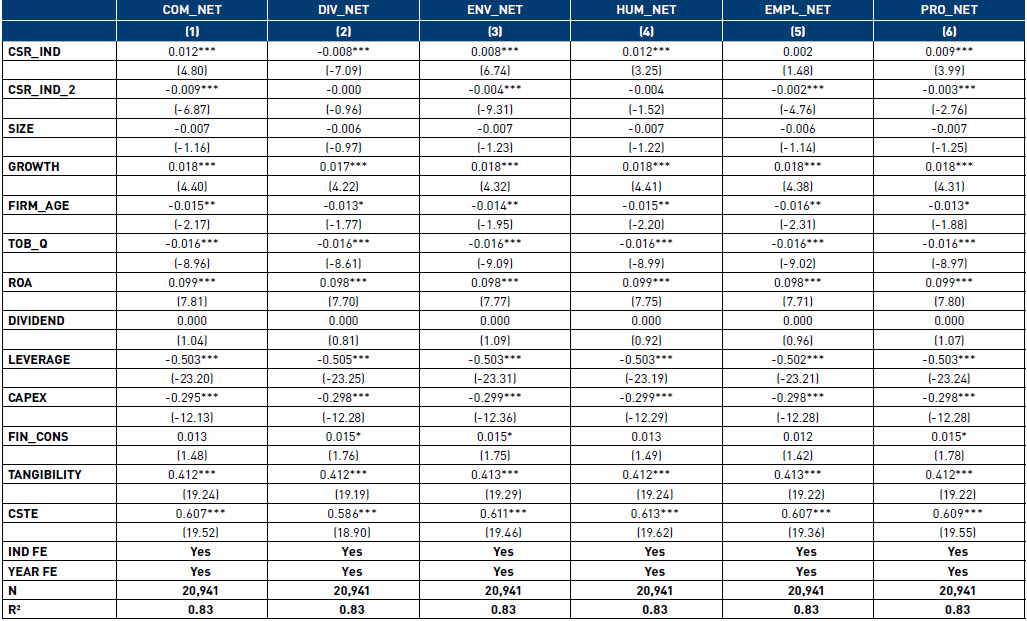

In this section, we study the relationship between individual components of CSR and firm’s capital structure as CSR is likely to be a multidimensional concept (Carroll, 1979). Carroll (1979) distinguishes between firm’s primary (stakeholders that affect or are directly affected by firm’s activities) and secondary (stakeholders that affect or are indirectly affected by firm’s activities) stakeholders. As discussed in prior literature (e.g., Attig et al., 2013, Benlemlih et al., 2018), the use of an aggregate measure of CSR may prevent a proper understanding of the CSR-Capital structure link. We thus use the same model as discussed previously and replace the overall CSR score by the six individual dimensions as provided by MSCI ESG STATS.

Table 5 presents the results and shows that the individual dimensions’ analysis provides strong support for the overall CSR score findings. The results of five out of six dimensions are completely in line with our expectation and show a positive and significant coefficient for the individual score (CSR_IND that reflects each time a specific dimension of CSR) and negative and significant coefficient for the individual score squared (CSR_IND_2). The only dimension that goes against our expectation is diversity with a negative and significant coefficient on the diversity score and insignificant coefficient on the diversity score squared.

Robustness Tests. Endogeneity[9]

The use of an OLS regression does not take into consideration that firms are likely to choose their level of long-term debt and shareholders’ equity simultaneously. To consider this issue, we use a system of two simultaneous equations, recognizing that long-term debt is determined endogenously with shareholders’ equity. The long-term debt and the shareholders’ equity equations contain the CSR score, the CSR score squared and the controls for the same variable as in our baseline model. We next estimate this system of equations using two-stage least squares. Overall, the results from this approach indicates that even when controlling for the simultaneous choice by firms for their level of long-term debt and shareholders’ equity the positive (negative) association continues to hold between CSR score (squared) and shareholders’ equity. These results confirm that the main evidence from our baseline model is not driven by the simultaneous choice of equity and long-term debt.

Robustness Tests. 2SLS Approach

Our study’s results may suffer from simultaneity and reverse causality. On the one hand, firm’s capital structure may be the source of firm’s decision to invest in CSR. On the other hand, it is possible that omitted firm-level factors that affect both firm’s capital structure and the CSR strategy are driving our results. To mitigate these concerns, we re-estimate the regressions from our main analysis using the instrumental variables approach. We use a two-stage least square analysis that includes (1) the initial CSR score of the firm (CSR_INI) and (2) the industry CSR score (CSR_IND) as instruments (Attig et al., 2013; El Ghoul et al., 2011; Benlemlih and Bitar, 2016). First, when the initial CSR score is positive, it is likely that the firm would maintain the same CSR involvement in the following years. Thus, the CSR initial score is likely to be exogenous to firm’s capital structure. Second, the industry CSR score is likely to affect firm’s involvement in CSR activity, however this instrument is expected to be exogenous to the firm’s capital structure. We subsequently perform the first stage regression of the CSR score on the two instruments and the full set of control variables from our main specification. The F-test in the first stage is positive and significant (64.01), and the coefficients load positive and statistically significant. In the second stage, we regress the financing decisions variable (shareholders’ equity to total asset) on the predicted CSR_NET and CSR_NET_2 and control variables. The result continues to indicate that CSR (squared) positively (negatively) affects the capital structure variable ad found previously.

Table 4

Corporate social responsibility and the use of equity capital. The moderated effect of the control variables

The table shows the results from regressing the equity capital variable on the CSR scores moderated by the control variables. The dependent variable is the amount of shareholders’ equity to total asset. The overall CSR score is calculated from the six individual CSR scores as provided by MSCI ESG. The control variables used in the regressions are described in the appendix. All the models include year and industry fixed effects. For the lack of space, we only include the coefficients on the CSR scores. Appendix A outlines the definitions for all the regression variables. Robust t-statistics based on Newey-West standard errors are presented in parentheses.

* statistical significance at the 10% level. ** statistical significance at the 5% level. *** statistical significance at the 1% level.

Table 5

Individual components of corporate social responsibility and the use of equity capital

This table reports results from regressing the equity variable on the overall CSR score and control variables over the 20,941 firm-year observations of the sample. The dependent variable is the amount of shareholders’ equity to total asset. The individual CSR dimensions analysed in this tables are community (Model 1), diversity (Model 2), environment (Model 3), human rights (Model 4), employees’ relations (Model 5) and product characteristics (Model 6). The control variables used in the regressions are described in the Appendix. All the models include year and industry fixed effects. Appendix A outlines the definitions for all the regression variables. Robust t-statistics based on Newey-West standard errors are presented in parentheses.

* statistical significance at the 10% level. ** statistical significance at the 5% level. *** statistical significance at the 1% level.

Robustness Tests. Heckman Self-Selection Method

To address the self-selection bias, we use Heckman (1979) two-stage self-selection model. The aim of this approach is to control for self-selection bias induced by firms choosing to increase their level of CSR activities. In the first step, we run a probit model and regress a dummy variable that takes 1 if the firm has a positive overall CSR score and 0 otherwise on all the control from the main specification of the study and the instrumental variables used in the previous section. In the second-stage regression, equity to total assets ratio is the dependent variable, the CSR scores are the interest variables, the control variables are those use in the main model, and we include the self-selection parameter (measured as the inverse Mills ratio) estimated from the first-stage regression.

Even after controlling for self-selection bias using the two-step estimation approach, this analysis continues to suggest for a reverse U-shaped relationship between CSR and the use of equity capital.

Conclusion

Very little attention is paid to the non-linear relationship that may exist between CSR and capital structure. This paper fills this gap in the literature. Using a large sample of more than 2,000 individual firms representing 21,116 firm-year observations, we find significant evidence on a reverse U-shaped relationship between CSR and the use of equity capital.

Our results support the argument that CSR investments may be considered as an agency conflict only if the firm’s involvement in such activities goes beyond certain level. An extremely high level of CSR is likely to signal agency conflict related to CSR overinvestment and leads to the use of less equity financing as opposite to moderate level of CSR that has been proven to significantly reduce the cost of equity financing and leads to the use of more equity financing. This conclusion is likely to provide insights for management regarding their practices towards firms’ stakeholders.

Our study shed the lights on a potential new determinant of a firm’s financing decisions. While previous literature emphasizes that agency costs affect firms’ capital structure; our findings clearly show that CSR practices are likely to determine, to a certain level, firms’ decision to finance their activity using equity capital over debt. This finding is of interest for management as CSR practices are likely to have an influence on the firm’s strategy, and the financing decisions. CSR practices also facilitate firm’s access to investors who care about the social and environmental impact of their investment.

Future studies may extend the framework of our work by examining the U-shaped relationship between CSR and the cost of equity or debt financing. In addition, it also could be relevant to explore the U-shaped relationship between CSR and firm’s capital structure in different geographic areas. Ben Larbi et al. (2019) and Girerd-Potin et al. (2017) recently demonstrate that the legal and cultural components are strong determinants of CSR activities and that firm’s institutional and cultural contexts are likely to influence the choice to be socially responsible. Future studies may explore to what extent these institutional factors moderate the CSR-capital structure relationship.

Parties annexes

Appendix

appendix a. The study’s variables

Biographical notes

Mohammed Benlemlih is an Associate Professor of Finance at EM Normandie where he teaches several courses related to corporate finance, financial markets and business ethics. Dr. Benlemlih research interests include corporate finance, corporate governance, nonfinancial information, and corporate social responsibility. His research has been presented in international conferences, and published in leading academic journals such

Mohammad Bitar is an Assistant Professor of Finance at Nottingham University Business School. Dr. Bitar research interests include banking, finance, and corporate social responsibility. His research has been presented in international conferences, and published in leading academic journals such as the Journal of Corporate Finance, Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Financial Stability, among others.

Elias Erragragui is an Associate Professor at the University of Picardie Jules Verne (UPJV). He also serves as the academic director of the Master in Islamic Finance at KEDGE Business School and teaches several courses related to corporate finance, financial markets and ethical finance. His main research axes focus on ethical finance, corporates’ environemental social and governance issues and ecological transition in emerging markets. His current works also target FinTech development and alternative forms of finance. He published several papers in internationally refereed journals and contributed to several collective books in the field of social and ethical finance.

Jonathan Peillex is Associate Professor at ICD International Business School. He is also Research Fellow at the University of Picardie Jules Verne, Amiens. He holds his PhD in Business Administration from the University of Picardie Jules Verne and his HDR from the University of Grenoble. His research focused on finance and business. Its recent research works have been published in academic journals such as Ecological Economics, Financial Analysts Journal, Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Comparative Economics and Management International.

Notes

-

[1]

In the paper, following Peillex and Comyns (2020), the term CSR refers to the degree of voluntary incorporation of social and environmental issues into business activities.

-

[2]

One might argue that capital structure refers to the choice between equity and debt, and that, CSR may also have a positive impact on the cost of debt which will make the decision to be financed by debt also favorable. As from previous literature, it has been shown that the impact of CSR on the cost of debt is not obvious. For instance, Goss and Roberts (2011) observed mixed reaction from lenders to the firms’ CSR involvement and show that low-quality borrowers that consider CSR practices face higher loans spreads, while lenders are different to CSR practices from high-quality borrowers. The authors conclude that CSR is a second order determinant of yield spreads, and that banks do not consider CSR as a source value enhancing or risk reducing for the firm. That said, equity choice is likely to be favored over debt financing in our context.

-

[3]

While the decrease of the bankruptcy risk would create an incentive for both equity and debt financing, we expect the impact to be more favourable for the equity financing. Indeed, as discussed in our first argument, lenders slightly consider CSR activities and the cost of debt do not systematically reflect the firms’ CSR involvement as opposed to the equity financing. This is likely to create an incentive for the equity financing over debt.

-

[4]

KLD data provider was acquired by MSCI ESG in 2012. Since this acquisition, the extra-financial rating agency has amended substantially its rating methodology. Hence, our sample period ends in 2012 i.e., the last year that KLD database used its initial methodology.

-

[5]

As in Servaes and Tamayo (2013), we do not consider that corporate governance as a part of CSR. While corporate governance concerns the mechanisms that allow shareholders to reward and exert control on agents, CSR deals with the social and environmental objectives of the company and stakeholders other than shareholders. We thus exclude corporate governance component when constructing our overall CSR score. Nevertheless, our findings remain unchanged when we include the corporate governance area in the calculation of our overall CSR measure.

-

[6]

The authors have used qualitative information to categorize financial constraints for a random sample firms and assessed logit models predicting constraints as a function of several quantitative factors. They found that firm size and age particularly predict financial constraint levels.

-

[7]

Our control variables are mainly motivated by previous literature as discussed above. However, one referee has mentioned that including financial constraints and leverage my affect our results. In order to ensure this is not the case, we run our main Model from the main analysis after excluding the leverage and financial constraints. The findings continue to show the documented relationship between CSR and the ratio of shareholder’s equity. These table are not reported in the paper for the lack of space but are available from the authors upon request.

-

[8]

With respect to the use of CSR square, our objective in this paper is to investigate the nonlinear relationship between CSR and the use of equity capital. As from prior literature, a quadratic relationship that includes a CSR square variable remains the most appropriate technique to investigate this relationship (e.g., Chang, et al., 2017; Nollet, 2016).

-

[9]

The tables from this section are not presented for the lack of space. They are available from the authors upon request.

Bibliography

- Al-Malkawi, H. A. N., Pillai, R., & Bhatti, M. I. (2014). Corporate governance practices in emerging markets: The case of GCC countries. Economic Modelling, 38, p. 133-141.

- Attig, N., Boubakri, N., El Ghoul, S. & Guedhami, O. (2016). Firm internationalization and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics 134(2), p. 171-197.

- Attig, N., El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O. & Suh, J. (2013). Corporate social responsibility and credit ratings. Journal of Business Ethics 117(4), p. 679-694.

- Bae, K.-H., Kang, J.-K. & Wang, J. (2011). Employee treatment and firm leverage: A test of the stakeholder theory of capital structure. Journal of Financial Economics 100(1), p. 130-153.

- Bae, K. H., El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., Kwok, C. C., & Zheng, Y. (2018). Does corporate social responsibility reduce the costs of high leverage? Evidence from capital structure and product markets interactions. Journal of Banking & Finance.

- Baker, M., Wurgler, J. (2002). Market timing and capital structure. Journal of Finance 57, p. 1-32.

- Barclay, M. J., & Smith Jr, C. W. (1995). The maturity structure of corporate debt. The Journal of Finance, 50(2), p. 609-631.

- Barnea, A., & Rubin. A. (2010). Corporate social responsibility as a conflict between shareholders. Journal of Business Ethics 97(1), p. 71-86.

- Barnett, M. L., & Salomon, R. M. (2006). Beyond dichotomy: The curvilinear relationship between social responsibility and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 27(11), p. 1101-1122.

- Barnett, M. L., & Salomon, R. M. (2012). Does it pay to be really good? Addressing the shape of the relationship between social and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 33(11), p. 1304-1320.

- Bartkus, B. R., Morris, S. A., & Seifert, B. (2002). Governance and corporate philanthropy: Restraining Robin Hood? Business and Society 41(3), p. 319-344.

- Ben Larbi, S., Lacroux, A., & Luu, P. (2019). La performance sociétale des entreprises dans un contexte international: Vers une convergence des modèles de capitalisme? Management International/International Management/Gestión Internacional, 23(2), p. 56-72.

- Benlemlih M, & Girerd-Potin I. (2017). Corporate social responsibility and firm financial risk reduction: On the moderating role of the legal environment. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 44, p. 1137-1166.

- Benlemlih, M. (2017). Corporate social responsibility and firm debt maturity. Journal of Business Ethics 144(3), p. 491-517.

- Benlemlih, M., & Bitar, M. (2016). Corporate social responsibility and investment efficiency. Journal of Business Ethics, p. 1-25.

- Benlemlih, M., Jaballah, J., & Peillex, J. (2018). Does it really pay to do better? Exploring the financial effects of changes in CSR ratings. Applied Economics, 50(51), p. 5464-5482.

- Benlemlih, M., & Peillex, J. (2019). Revisiter la question “Does it pay to be good?” dans le contexte européen. Recherches en Sciences de Gestion, (1), p. 243-263.

- Brown, W. O., Helland, E., & Smith, J. K. (2006). Corporate philanthropic practices. Journal of Corporate Finance 12(5), p. 855-877.

- Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate social performance. The Academy of Management Review 4(4), p. 497-505.

- Chang, Y. K., Oh, W. Y., Park, J. H., & Jang, M. G. (2017). Exploring the relationship between board characteristics and CSR: Empirical evidence from Korea. Journal of Business Ethics, 140(2), p. 225-242.

- Cheng, B., Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2014). Corporate social responsibility and access to finance. Strategic Management Journal, 35(1), p. 1-23.

- Dardour, A., Husser, J. (2016). Does It Pay to Disclose CSR Information? Evidence from French Companies. Management International/International Management/Gestión Internacional, 20, p. 94-108.

- Dhaliwal, D. S., Li, O. Z., Tsang, A. & Yang, Y. G. (2011). Voluntary nonfinancial disclosure and the cost of equity capital: The initiation of corporate social responsibility reporting. The Accounting Review 86(1), p. 59-100.

- Di Giuli, A., Kostovetsky, L. (2014). Are red or blue companies more likely to go green? Politics and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Financial Economics 111(1), p. 158-180.

- Easterbrook, F.H., (1984), Two agency-cost explanations of dividends, American Economic Review, 74 (4), p. 650-659.

- El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., Kwok, C. C. Y. & Mishra, D. R. (2011). Does corporate social responsibility affect the cost of capital? Journal of Banking & Finance 35(9), p. 2388-2406.

- El Ouadghiri, I., Guesmi, K., Peillex, J., & Ziegler, A. (2019). Public attention to environmental issues and stock market returns (No. 22-2019). Joint Discussion Paper Series in Economics.

- Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (2005). Financing decisions: who issues stock?. Journal of financial economics, 76(3), p. 549-582.

- Farre-Mensa, J., & Ljungqvist, A. (2016). Do measures of financial constraints measure financial constraints?. The Review of Financial Studies, 29(2), p. 271-308.

- Feng, Z. Y., Wang, M. L., & Huang, H. W. (2015). Equity financing and social responsibility: further international evidence. The International Journal of Accounting 50(3), p. 247-280.

- Frank, M. Z., & Goyal, V. K. (2003). Testing the pecking order theory of capital structure. Journal of financial economics, 67(2), p. 217-248.

- Freeman, R.E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman, Boston, MA.

- Friedman, M. (1970). The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. The New York Times Magazine, 13 September 1970.

- Fulghieri, P. & Lukin D. (2001). Information production, dilution costs, and optimal security design. Journal of Financial Economics 61, p. 3-42.

- Gallén, M. L., & Peraita, C. (2018). The effects of national culture on corporate social responsibility disclosure: a cross-country comparison. Applied Economics, 50(27), p. 2967-2979.

- García-Gallego, A., & Georgantzís, N. (2009). Market effects of changes in consumers’ social responsibility. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 18(1), p. 235-262.

- Girerd-Potin, I., Jimenez-Garces, S., & Louvet, P. (2017). L’influence de la culture nationale sur les politiques socialement responsables des entreprises. Management international/International Management/Gestiòn Internacional, 21(4), p. 146-163.

- Godfrey, P.C. (2005). The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: A risk management perspective. The Academy of Management Review 30(4), p. 777-798.

- Goss, A. & Roberts, G. S. (2011). The impact of corporate social responsibility on the cost of bank loans. Journal of Banking & Finance 35(7), p. 1794-1810.

- Granado-Peiró, N., And López-Gracia, J. (2017) Corporate Governance and Capital Structure: A Spanish Study. European Management Review, 14, p. 33-45.

- Hadlock, C. J., & Pierce, J. R. (2010). New evidence on measuring financial constraints: Moving beyond the KZ index. The Review of Financial Studies, 23(5), p. 1909-1940.

- Hovakimian, A., Hovakimian, G., Tehranian, H. (2004). Determinants of target capital structure: The case of dual debt and equity issues. Journal of Financial Economics 71, p. 517-540.

- Hillman, A. J. & Keim, G. D. (2001). Shareholder value, stakeholder management, and social issues: What’s the bottom line? Strategic Management Journal 22(2), p. 125-139.

- Hong, H. & Kacperczyk, M. (2009). The price of sin: The effects of social norms on markets. Journal of Financial Economics 93(1), p. 15-36.

- Husser, J., & Evraert-Bardinet, F. (2014). The effect of social and environmental disclosure on companies’ market value. Management International/International Management/Gestion Internacional, 19(1), p. 61-84.

- Jensen, M. C. (1986). Agency costs of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeovers. The American economic review, 76(2), p. 323-329.

- Johnson, S.A. (2003). Debt maturity and the effects of growth opportunities and liquidity risk on leverage. Review of Financial Studies 16, p. 209-236.

- Kim, Y., Park, M. S. & Wier, B. (2012). Is earnings quality associated with corporate social responsibility? The Accounting Review 87(3), p. 761-796.

- Manasakis, C., Mitrokostas, E., & Petrakis, E. (2013). Certification of corporate social responsibility activities in oligopolistic markets. Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d’économique, 46(1), p. 282-309.

- Manasakis, C., Mitrokostas, E., & Petrakis, E. (2014). Strategic corporate social responsibility activities and corporate governance in imperfectly competitive markets. Managerial and Decision Economics, 35(7), p. 460-473.

- Mishra, S., Modi, & S. B. (2013). Positive and negative corporate social responsibility, financial leverage, and idiosyncratic risk. Journal of Business Ethics 117(2), p. 431-448.

- Modigliani, F., & Miller, M. H. (1958). The cost of capital, corporation finance and the theory of investment. American Economic Review, 48(3), p. 261-97.

- Myers, S. C., & Majluf, N. S. (1984). Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. Journal of financial economics, 13(2), p. 187-221.

- Ng, A. C., & Rezaee, Z. (2015). Business sustainability performance and cost of equity capital. Journal of Corporate Finance 34, p. 128-149.

- Nollet, J., Filis, G., & Mitrokostas, E. (2016). Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: A non-linear and disaggregated approach. Economic Modelling 52, p. 400-407.

- Peillex, J., & Ureche-Rangau, L. (2016). Identifying the determinants of the decision to create socially responsible funds: An empirical investigation. Journal of business ethics, 136(1), p. 101-117.

- Peillex, J., Boubaker, S., & Comyns, B. (2019). Does It Pay to Invest in Japanese Women? Evidence from the MSCI Japan Empowering Women Index. Journal of Business Ethics, p. 1-19.

- Peillex, J., & Comyns, B. (2020). Pourquoi les sociétés financières décident-elles d’adopter les Principes des Nations Unies pour l’Investissement Responsable? Comptabilité-Contrôle-Audit, 2020.

- Price, J. M., & Sun, W. (2017). Doing good and doing bad: The impact of corporate social responsibility and irresponsibility on firm performance. Journal of Business Research 80, p. 82-97.

- Rajan, R.R., & Zingales, L. (1995). What do we know about capital structure? Some evidence from International data. Journal of Finance 50, p. 1421-1460.

- Servaes, H. & Tamayo, A. (2013). The impact of corporate social responsibility on firm value: The role of customer awareness. Management Science 59(5), p. 1045-1061.

- Sharfman, M. (1996). The construct validity of the Kinder, Lydenberg & Domini social performance ratings data. Journal of Business Ethics 15(3), p. 287-296.

- Sharfman, M. P., & Fernando, C.S., (2008). Environmental risk management and the cost of capital. Strategic Management Journal 29, p. 569-592.

- Verwijmeren, P., & Derwall, J. (2010). Employee well-being, firm leverage, and bankruptcy risk. Journal of Banking & Finance 34(5), p. 956-964.

- Viviani, J. L., Fall, M., & Revelli, C. (2019). The Effects of Socially Responsible Dimensions on Risk Dynamics and Risk Predictability: A Value-at-Risk Perspective. Management International/International Management/Gestión Internacional, 23(3).

- Zheng, X., El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., & Kwok, C. C. Y. (2012). National culture and corporate debt maturity. Journal of Banking & Finance 36, p. 468-488.

Parties annexes

Notes biographiques

Mohammed Benlemlih est professeur associé à l’EM Normandie où il enseigne des cours en finance d’entreprise, finance de marché, et finance éthique. Ses axes de recherche portent la finance d’entreprise, la gouvernance d’entreprise, l’information extra-financière et la responsabilité sociale de l’entreprise. Ses travaux de recherche ont été présentés dans des conférences internationales et publiés dans des revues académiques telles que le Journal of Business Ethics, le Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, entre autres.

Mohammad Bitar est professeur assistant à Nottingham University Business School. Ses axes de recherche portent sur la banque, la finance, et la responsabilité sociale de l’entreprise. Ses travaux de recherche ont été présentés dans des conférences internationales et publiés dans des revues académiques telles que Journal of Corporate Finance, Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Financial Stability, entre autres.

Elias Erragragui est maître de conférences à l’Université de Picardie Jules Verne (UPJV). Il est également directeur académique du Master en finance islamique à la KEDGE Business School et enseigne plusieurs cours liés au financement des entreprises, aux marchés financiers et à la finance éthique. Ses axes de recherche principal portent sur la finance éthique, les enjeux environnementaux et sociaux des entreprises et la transition écologique dans les marchés émergents. Ses travaux actuels visent également le développement FinTech et les formes alternatives de financement. Il a publié plusieurs articles dans des revues à comité de lecture international et contribué à plusieurs ouvrages collectifs dans le domaine de la finance sociale et éthique.

Jonathan Peillex est Enseignant-chercheur à l’ICD International Business School. Il est également Chercheur Associé à l’Université de Picardie Jules Verne à Amiens. Il a obtenu son doctorat en Sciences de gestion à l’Université de Picardie Jules Verne et son Habilitation à Diriger des Recherches à l’Université de Grenoble. Ses travaux de recherche portent sur la finance et le business. Ses travaux récents ont été publiés dans des journaux comme Ecological Economics, Financial AnalystsJournal, Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Comparative Economics et Management International.

Parties annexes

Notas biograficas

Mohammed Benlemlih es profesor asociado en EM Normandie, donde imparte cursos de finanzas corporativas, mercados financieros y finanzas éticas. Sus áreas de investigación se centran en finanzas corporativas, gobierno corporativo, información no financiera y responsabilidad social corporativa. Su investigación ha sido presentada en congresos internacionales y publicada en revistas académicas como Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, entre otras.

Mohammad Bitar es profesor en Nottingham University Business School. Sus áreas de investigación se centran en bancario, finanzas y responsabilidad social corporativa. Su investigación ha sido presentada en congresos internacionales y publicada en revistas académicas como Journal of Corporate Finance, Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Financial Stability, entre otras.

Elias Erragragui es profesor asociado en la Universidad de Picardie Jules Verne (UPJV). También se desempeña como director académico del Máster en Finanzas Islámicas en KEDGE Business School y enseña varios cursos relacionados con finanzas corporativas, mercados financieros y finanzas éticas. Sus ejes principales de investigación se centran en las finanzas éticas, las cuestiones ambientales y de gobernanza corporativas y la transición ecológica en los mercados emergentes. Sus trabajos actuales también apuntan al desarrollo FinTech y formas alternativas de financiación. Publicó varios artículos en revistas de referencia internacional y contribuyó a varios libros colectivos en el campo de las finanzas sociales y éticas.

Jonathan Peillex es Professor en ICD International Business School. También trabaja como investigador afiliado en la Universidad de Picardie Jules Verne, Amiens. Obtuvo su doctorado en Administración de Empresas en la Universidad de Picardie Jules Verne y su HDR en la Universidad de Grenoble. Su investigación se centró en la finanza y el business. Sus recientes trabajos de investigación se publican en revistas académicas como Ecological Economics, Financial Analysts Journal, Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Comparative Economics and Management International.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Descriptive statistics for regression variables

Table 2

Correlation coefficients

Table 3

Corporate social responsibility and the use of equity capital

This table reports results from regressing the equity variable on the overall CSR score and control variables over the 21,116 firm-year observations of the sample. The dependent variable is the amount of shareholders’ equity to total asset. The overall CSR score is calculated from the six individual CSR scores as provided by MSCI ESG. The control variables used in the regressions are described in the appendix. All the models include year and industry fixed effects. Appendix A outlines the definitions for all the regression variables. Robust t-statistics based on Newey-West standard errors are presented in parentheses.

* statistical significance at the 10% level ** statistical significance at the 5% level. *** statistical significance at the 1% level.

Table 4

Corporate social responsibility and the use of equity capital. The moderated effect of the control variables

The table shows the results from regressing the equity capital variable on the CSR scores moderated by the control variables. The dependent variable is the amount of shareholders’ equity to total asset. The overall CSR score is calculated from the six individual CSR scores as provided by MSCI ESG. The control variables used in the regressions are described in the appendix. All the models include year and industry fixed effects. For the lack of space, we only include the coefficients on the CSR scores. Appendix A outlines the definitions for all the regression variables. Robust t-statistics based on Newey-West standard errors are presented in parentheses.

* statistical significance at the 10% level. ** statistical significance at the 5% level. *** statistical significance at the 1% level.

Table 5

Individual components of corporate social responsibility and the use of equity capital

This table reports results from regressing the equity variable on the overall CSR score and control variables over the 20,941 firm-year observations of the sample. The dependent variable is the amount of shareholders’ equity to total asset. The individual CSR dimensions analysed in this tables are community (Model 1), diversity (Model 2), environment (Model 3), human rights (Model 4), employees’ relations (Model 5) and product characteristics (Model 6). The control variables used in the regressions are described in the Appendix. All the models include year and industry fixed effects. Appendix A outlines the definitions for all the regression variables. Robust t-statistics based on Newey-West standard errors are presented in parentheses.

* statistical significance at the 10% level. ** statistical significance at the 5% level. *** statistical significance at the 1% level.

10.7202/1060031ar

10.7202/1060031ar