Résumés

Abstract

This research investigates the motivations of counterfeit luxury consumption in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. Using a Means-End Chain approach, this research uncovers four dominant motivational patterns and complexities that drive affluent GCC consumers to purchase counterfeit luxury products: Value-Consciousness, Belonging, Hedonism and Self-esteem. Luxury brands and policy makers could use these main hidden final values to gain a holistic understanding of consumer motivations and develop stronger anti-counterfeiting strategies to discourage counterfeit consumption.

Keywords:

- Counterfeiting,

- Luxury brand,

- Means-End Chain,

- GCC consumers

Résumé

Cette recherche examine les motivations de la consommation de produits de luxe contrefaits dans les pays du Conseil de coopération du Golfe (CCG). En utilisant une analyse par chaînages cognitifs, cette étude révèle quatre modèles de motivation dominants qui poussent les consommateurs aisés des pays membres du CCG à acheter des produits de luxe contrefaits : la conscience de la valeur, l'appartenance, l'hédonisme et l'estime de soi. Les marques de luxe et les décideurs pourraient utiliser ces principales valeurs pour acquérir une compréhension des motivations des consommateurs et développer des stratégies de lutte contre la contrefaçon plus solides afin de décourager la consommation des contrefaçons.

Mots-clés :

- contrefaçon,

- marque de luxe,

- chaînages cognitifs,

- consommateurs du CCG

Resumen

Esta investigación estudia las motivaciones de consumo de productos de lujo falsificados en los países del Consejo de Cooperación del Golfo (CCG). Utilizando el modelo de Cadenas Medio-Fin, esta investigación descubre cuatro patrones motivacionales dominantes que llevan a los consumidores de CCG a comprar productos de lujo falsificados: Conciencia de Valor, Pertenencia, Hedonismo y Autoestima. Las marcas de lujo y los responsables políticos podrían usar estos principales valores finales ocultos para obtener una comprensión holística de las motivaciones de los consumidores y, así, desarrollar estrategias más fuertes contra la falsificación para, de este modo, desalentar el consumo de falsificaciones.

Palabras clave:

- falsificación,

- marca de lujo,

- cadenas Medio-Fin,

- consumidores CCG

Corps de l’article

Counterfeiting has grown drastically in the recent years and could reach the global economic value from USD 1.7 trillion in 2015 to USD 2.3 trillion in 2022 (International Trademark Association (INTA) and the International Chamber of Commerce). INTA (2017) holds counterfeiting responsible for the loss of US $4.2 trillion from the global economy and for putting 5.4 million legitimate jobs at risk. Luxury brand manufacturers are concerned about not only losses in revenues but also about the damage made to brands most valuable assets such as brand perception and reputation (Bian et al., 2016; Kapferer and Michaut, 2014). Taking into consideration the rapid growth of the counterfeit market it appears that anti-counterfeiting measures employed by governments and companies have not produced useful results. Given the dependence of the counterfeit market on consumers’ desire for such goods, it is crucial to analyze why consumers actually knowingly purchase them, despite social, economic or physical risks (Amaral and Loken, 2016; Bian et al., 2016; Pueschel et al., 2017; Rosenbaum et al., 2016).

Research about drivers of counterfeit consumption has grown in the past decade, with more academics attempting to identify motivation, antecedents of motivations and drivers of such consumption (Bian et al., 2016; De Matos et al., 2007; Eisend and Schuchert-Güler, 2006; Kaufmann et al., 2016). These studies are mostly conducted in Western and Asian countries (Eisend, 2016; Franses and Lede, 2015). Since counterfeit consumption is contingent on cultural contexts (Burgess and Steenkamp, 2006; Eisend, 2016; Eisend and Schuchert-Güler, 2006; Veloutsou and Bian, 2008), a deeper cultural research on the subject seems necessary. The present paper examines the counterfeit consumption by the local population in the United Arab Emirates. Several reasons drive this focus. First, because of the geographical position on a junction of trade routes between Europe, Asia and Africa, The UAE had become one of the major transit hubs for counterfeit goods around the globe (OECD, 2017). Second, the country faces increased problems with counterfeits. In 2018, the Department of Economic Development (DED) reported the seizures of counterfeit goods worth AED 332 million (USD 90.2 million) and shut down of 13,948 social media accounts selling fake items (The National, 2019). Third, the literature on counterfeiting names the low price of counterfeited products as the primary decision factor for the purchase (Ang et al., 2001; Bian et al., 2016; Sharma and Chan, 2011; Tom et al., 1998). Since the population of the UAE is among the most affluent in the world, scoring place 6 in GDP per Capita in terms of purchase power parity globally (World Bank, 2018), it appears surprising that individuals with sufficient financial means purchase counterfeits. Hence, we can assume that the obvious price advantage of counterfeits is not a primary motivation for such consumption. Fourth, the research on luxury counterfeiting is very scarce in the region (except for Fernandes (2013) and Pueschel et al. (2017), where a massive accumulation of wealth caused profound changes in the society and values. Consequently, the central premise of this research is that personal, social, cultural and religious aspects influence consumers’ motivations to consume counterfeits (Ronkainen and Cusumano, 2001; Santos and Ribeiro, 2006) and these motivations might differ from other countries. Specifically, the present research adopts a Means-End Chain analysis method that is appropriate for investigating consumers’ motivational patterns (Gutman, 1982; Reynolds and Gutman, 1988) and is widely used to uncover consumers’ covert cognitive structures i.e., the hierarchical constructs that are not instantly clear (Gengler and Reynolds, 1995; Guido et al., 2014; Lin, 2002; Wansink, 2000). The findings are of major interest for public policy makers and luxury brand managers fighting counterfeiting.

Conceptual Background

Counterfeit Consumption

Counterfeiting is a significant threat to brand reputation and company’s revenues (Kapferer and Michaut, 2014; Wilcox et al., 2009). Since supply is driven by demand, numerous studies have focused on the underlying factors that influence demand for counterfeit products. Four main influential drivers have been identified by Eisend and Schuchert-Güler (2006): product characteristics such as price (Ang, et al., 2001; Bian et al., 2016; Harvey and Walls, 2003; Sharma and Chan, 2011; Staake and Fleisch, 2008) and product attributes (Ang et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2005; Wee et al., 1995); consumers demographic and psychographic variables (Eisend and Schuchert-Güler, 2006; Jiang and Shan, 2016; Rutter and Bryce, 2008), especially ethical and lawfulness aspects (Cordell et al., 1996; Eisend, 2016; Martinez and Jaeger, 2016; Phau and Teah, 2009); mood and situational context (Eisend and Schuchert-Güler, 2006; Gentry et al., 2001); and social and cultural context (Wilcox, et al, 2009). Many factors that are considered in the literature as motivation, such as perceived risk, which is a type of perception, are in fact not a motivation itself, but it is an antecedent that motivated the individual to avoid risk (Bian et al., 2016). For that reason, the current stand advocates for further empirical support of more profound understanding of true motivation for counterfeit consumption (Tang et al., 2014).

Motivations and Counterfeit Consumption

Motivation signifies “psychological processes that cause the arousal, direction, and persistence of behavior” (Mitchell, 1992, p. 81). In general, a motivated person is “moved to do something” (Ryan and Deci, 2000). Hence, motivation is a goal-oriented behavior (Mowen and Minor, 1998). When a consumer feels the drive, urge or need to acquire a product, he goes shopping. In the context of consumer behavior, motivations are a function of many variables, which are not always related to the actual purchase of the products (Tauber, 1972). Consumers don’t merely buy products, they buy tangible or intangible benefits that are driven by two types of psychosocial motives: personal and social (Tauber, 1972).

When studying the motives of counterfeit consumption, scholars mostly refer to the price advantage of these goods over their legitimate counterparts (Wang et al., 2005). Consumers desire to optimize and gain more control over their economic resources (Jirotmontree, 2013; Perez et al., 2010) or to increase the number of items they purchase and possess and often view the counterfeit items they possess as a route to happiness and social recognition (Moschis and Churchill, 1978; Trinh and Phau, 2012). A social group can also influence consumer behavior regarding counterfeits (Ang et al., 2001; Phau and Teah, 2009; Tang et al., 2014). Another critical component in the counterfeit buying process is the variety-seeking, which incorporates the desire to seek novelty and variety (Phau and Teah, 2009; Wee et al. 1995) and be “in-vogue” (Bian et al., 2016).

When comparing purchase situation in the home country where the counterfeits are not widely available vs. the situation when consumers are on holiday, Eisend and Schuchert-Güler (2006) have discovered that in the latter situation, the counterfeit purchases fulfill surplus purposes such as “souvenirs” or “spending the last bit of money”. Furthermore, when people are in a holiday mood, they are more inclined to engage themselves in counterfeit consumption (Rutter and Bryce, 2008). The buying process of counterfeits and breaking the relevant law can urther trigger a “thrill of hunt” (Bian et al., 2016), heighten the sense of fun, augment the experience of adventure and enjoyment (Hamelin et al.,2013). Some consumers may experience a big deal of excitement of fooling others by telling them they own the original (Perez et al., 2010), others merely desire to try the product (Gentry et al., 2006; Sharma and Chan, 2011, 2016) and if this trial is successful, they might even opt for the original version (Gosline, 2010).

Investigation of consumers motivations to purchase counterfeits can offer valuable insight into factors that drive the purchase decisions, thus further complementing the existing literature. Of particular interest to this research is the exploration of the motivations that go beyond the price advantage. The study employs the laddering technique (Reynolds and Gutman, 1988) and Means-End Chain (MEC) analysis that allows the detailed analysis of the cognitive motive structures.

Methodology and Research Process

Means-End Chain Analysis

This research employs the Means-End Chain (MEC) approach to investigate consumers’ motivations for buying counterfeits, and more precisely their cognitive motives through the creation of linkages between pertinent attributes, utility components that result from them, and individuals’ values. MEC analysis has been applied widely through various research domains (Reynolds and Phillips, 2008), including cross-cultural studies (Baker et al., 2004).

The MEC approach was developed by Gutman (1982) to portray how consumers categorize information about products in the memory and to understand their purchasing choices. The central assumption of MEC is that the consumers’ decision-making process is represented through a hierarchical network of attributes, consequences and values. Therefore, the MEC is a model that pursues the explanation of how the attributes of a product or service (means) are linked to consequences that result from usage of the product which are linked to values (ends or desired end goals) (Gutman, 1982). The attributes relate to characteristics of the product (e.g., price, style). The consequences are understood as results that are provided to the consumer by the attributes (Reynolds and Gutman, 1988). Each consequence supports one or multiple values (ends) in the life of the individual (Gengler and Reynolds, 1995). So, the ends are “valued states of being such as happiness, security, accomplishment” (Gutman, 1982). This analysis is focusing specifically on the linkages between attributes, consequences and values, and allow researchers to identify the specific segments with explicit hierarchies while considering the hierarchical nature of the stimuli (the elements of A-C-V) (Valette-Florence, 1998).

The MEC analysis which is based on the in-depth interviews has the advantage of providing an exhaustive and deep insight through guiding the participants to construct a ladder by linking the attributes of the product their motivations and consequences and then reveal the final values that are related to consumer’ choice. Laddering is an efficient method to draw these links (Wansink, 2003). The ladders of each individual respondent are decomposed into direct and indirect components and filed into implication matrix. The results of MEC are visualized in a hierarchical value map (HVM) (Reynolds and Gutman, 1988). The present research uses the traditional laddering procedure (Reynolds and Gutman, 1988) to facilitate reflections on consumers’ personal buying motivations of counterfeit luxury goods and on the relationship among attributes-consequences-ends.

Procedure

In-depth interviews were initiated to understand more about the underlying mechanisms of luxury counterfeit consumption. 38 in-depth interviews were conducted with UAE national female consumers. This concentration on female population has two main reasons: females are more engaged in the shopping process, and as the interviewer was female, the access was more comfortable from the cultural point of view, where the big emphasis is put on gender separation. The help of Emirati national students was used to gain access to interviewees.

As counterfeit consumption is rather a sensitive topic due to high perceived social risk (Pueschel et al., 2017), there was no initial distinction between buyers and non-buyers of counterfeits. The recruitment process started with the direct network of the researcher, then the snowballing procedure was used to recruit further participants, others were recruited through social media sites. The interviews were conducted in English because it is considered the primary communication language in the UAE and even questions the position of Arabic as a first national language (Al-Issa, 2017). If some respondents didn’t feel confident in expressing their exact thoughts and opinions in English, the help of an interpreter was used to ensure the depth of the responses.

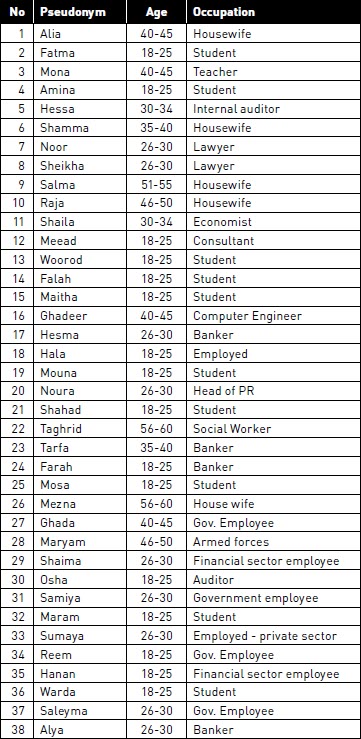

Table 1

Respondents

The interviews started with an extended small talk and general questions about shopping habits. Not surprisingly, when talking about these habits, respondents spoke predominantly about luxury brands. This process allowed the researcher to remain assured that all the respondents are real luxury consumers and have confirmed the ownership and habitually excessive consumption luxury products. Later, the researcher asked questions about the consumers’ experiences with counterfeits. The approach of delaying questions about counterfeit experiences has proven itself as effective, especially when dealing with a culture in which face consciousness is highly valued. When the respondents manifested avoidance behavior, the techniques proposed by Reynolds and Gutman (1988) were used to deal with blockages. When participants had difficulties identifying their motives, the “third person probe” was applied, whereby they were asked about how others they know feel about counterfeits in similar circumstances.

The interviews were conducted in different locations and lasted on average 37 minutes. The interviews were recorded and transcribed. The data had been analyzed using the three main steps: 1/ content analysis, 2/ construction of implication matrix, 3/ construction of hierarchical value map (HVM). A content analysis was carried out using Nvivo11 in which different types of elicited elements were identified. The codes were assigned using the Reynolds and Gutmans’ (1988) levels of analysis: attributes, consequences, and values. All the codes were revisited and revised, so some codes of the same hierarchical level were combined in summary codes. Based on the analysis of ladders, eight attributes appeared. These attributes relate to fifteen consequences, which in turn lead to six values.

In order to address the issue of intra-coder reliability (Miles et al., 2014) all the codes were triple-coded by the researcher at three different periods of time (Mirosa and Tang, 2016).

Following the content analysis presented in this section, the next section summarizes the results from ladders and MECs that were created for each respondent.

Results

The reasons for consumer purchase decisions are not always obvious (Wansink, 2003). Although a consumer might quickly respond to questions related to the product, these responses are often not the fundamental reasons for their decisions (Rokeach, 1973). Further, the attributes, consequences and values are reported to identify the main motivations for counterfeit purchases.

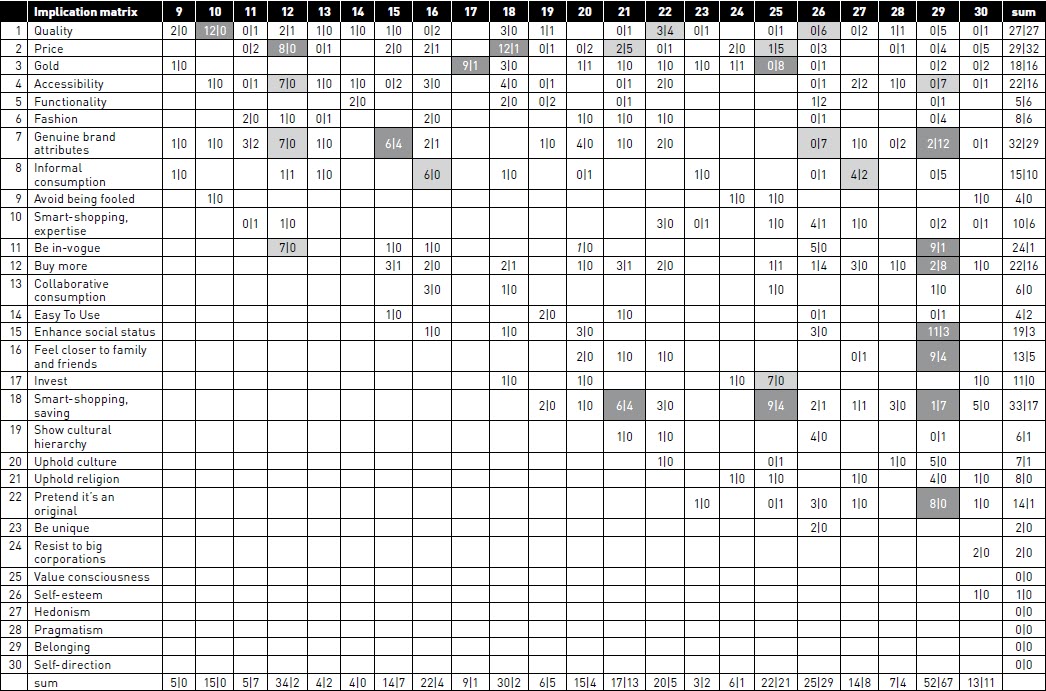

Implication Matrix

The ladders and elements were entered in LadderUX to produce a summary score matrix and to create an Implication Matrix and the Hierarchical Value Map (HVM), i.e., to perform the analysis of both direct and indirect relations (elements are related through another element) between adjacent elements. The HVM is constructed through computing the numbers of direct implications (A directly precedes B) and indirect implications (A indirectly precedes B). Whereby, the researcher selects the “significant” threshold value to define the meaningful implication between different levels of abstraction (Reynolds and Phillips, 2008).

The numbers in the matrix are expressed in a way, such that direct relations are represented to the left in the cell and indirect to the right. For instance, “Price” (2) leads to “Smart – Shopping - Saving” (18) 12 times directly and 1 time indirectly. It shows that the “Price” is 12 times directly connected to desire to feel smart about the purchase and save money; and 1 time because of another reason that is indirectly connected to smart-shopping feeling and desire to save.

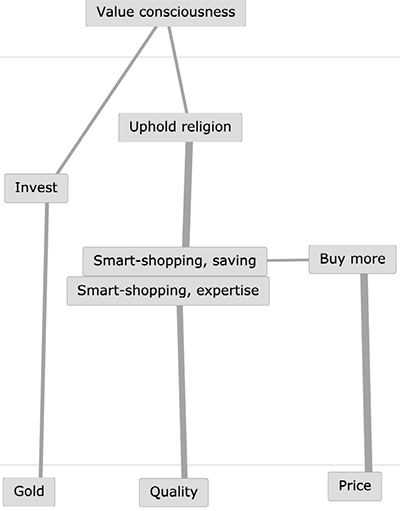

Hierarchical Value Map (HVM)

In the implication matrix the elements of the ladders are decayed into direct and indirect implications, while for HVM the “chains” from the data are constructed (Reynolds and Gutman, 1988). The HVM is a graphical representation of the A-C-V chains. For its construction, the researcher needs to set the “cut off” values. These are the minimum numbers of links between the elements that must be identified before the researcher considers the item. Only the concepts that have been mentioned at or above the cut off level were included in the HVM to produce the most informative and stable HVM (Gengler and Reynolds, 1995; Reynolds and Gutman, 1988). The cut off levels have been set at 5, the usual level as suggested by Reynolds and Gutman (1988). The complete set of data obtained in the in-depth interviews consists of 207 ladders, with an average of 5.4 ladders for each respondent.

Figure 1

Overview of Means-End Chain elements

Table 2

Implication matrix

FIGURE 2

Hierarchical Value Map

Based on the strength of associations and the count of direct and indirect links for the elements, “Belonging” and “Value Consciousness” appeared to be the strongest motives and “Enhance Social Status”, “Smart-shopping, saving” and “Smart- shopping, expertise” the dominant consequences, while “Price”, “Quality” and “Accessibility” are the major attributes of counterfeit products. Further, values such as “Self-esteem” and “Hedonism” can be identified.

Dominant Patterns

Value - Consciousness

It is not surprising that being exposed to the pressure to “excessively consume” luxury, the people are trying to cope with it. Although all of the respondents could afford genuine brands, they can buy probably many items of high luxury brands per year but have difficulties to keep up with the expectations to purchase plentifully every month.

“This AED 10,000 (USD 2,750), I can buy many things, fake, copy ones.”[...] Instead of spending all this money on one piece. Yeah, yeah.

Shaima

No, I didn’t actually buy anything above AED 20,000 (UDS 5,500), till now, except the watch…About 45,000 (USD 12,250). Other things like clothes and shoes and bags, I didn’t buy (anything) above 20,000.

Saleyma

“Price” is the most mentioned attribute of counterfeit luxury items. The obvious price advantage of counterfeits helps consumers to optimize their resources and lower acquisition price but, in the UAE, consumers give their preferences to certain types of counterfeits – trendy and of the “right” quality. Consequently, the monetary saving allows the consumers to increase the number of the goods they can obtain for the same amount of money (“Buy More”), feel smart about their decisions and satisfy the “Value Consciousness”.

I know a family and they are rich. They can afford like thousands of those bags, but they say, why should I pay like 20,000 (USD 5,500) on one bag where I can pay like 20,000 on like six different bags? Yes, we can afford it but why should we waste when we can get like more quantity?

Maram

Data shows that consumers allocate a budget for shopping, and although this budget is sufficient to purchase an original, it is still not sufficient to buy multiple trendy genuine items but counterfeits allow the consumers to satisfy the desire to own plenty of new items. Moreover, buying fakes, consumers experience the satisfaction of being a smart shopper (“Smart-shopping, saving” and “Smart-shopping, expertise”).

I don’t care about other what they say about me because this is my money and I buy what I want, and I prefer to use my money in other things like help others and buy gold, so it’s not important to buy (real) brands.

Warda

FIGURE 3

Value – Consciousness

Many participants explain their “Smart Shopping - Saving” by the desire to “Uphold religion”. They stress on their motivations to align with religion through their behaviors, views and also consumption, as the society in the UAE values Islamic religion and traditions. The ways to express these motivations are diverse. Some respondents describe their desire to help people in low-income countries by purchasing counterfeit products produced in these countries and not the real brands:

God told us to share our good, what he gave us. You must help people with your money. You might build a mosque, you might build a school in some poor country. There are so many good ways. But waste it on the brands - NO.

Alya

I can buy a AED 1,000 (USD 272) bag and instead of paying 10,000 I would take the 9,000 and give it to charity or do something good for the poor people. And, it’s not good to spend that much of money in one stuff that I can [/get]it for like half of the price.

Reem

Consumers are willing to live in accordance with the religious principles of Islam, preserving their culture and traditions. The notion of the copyright is not present in the culture or religion so, consumers view the counterfeits as a mean to make a “correct” or “smart” choice when deciding to buy counterfeit or highly priced original luxury goods. Interviewees enthusiastically report about their intentions to participate in charitable actions and opposing these actions to excessive consumption of material goods.

While talking about luxury brands, many participants mention luxury fine jewelry. Interestingly, even those participants who said that they rejected counterfeit items in general, proudly announced that they buy ready-made fake jewelry or would ask a jeweler to produce the exact copies of jewelry from luxury brands, including brand names and serial numbers.

It was real gold with real diamonds, but it was a fake one (Love bracelet). […] And the thing is, if you look at in the inside, it’s engraved with the laser “Cartier”.

Sheikha

My friend, her aunt, she goes to the gold shop and gives them a sample of Van Cleef. They copy the exact same thing and they do the necklace, bracelets and earrings.

Hanan

Overall in the sample money is better invested in precious materials such as gold, and since gold retains its value, unlike fashion items, respondents don’t view these items as counterfeits of a lower quality and don’t consider paying for the original item when the items along with a trademark can be easily and relatively cheap duplicated by any jeweler.

I prefer to buy this luxury accessories from gold shop because, also it looks the same as original accessories, and original accessories- it’s too expensive, so in the gold shop I can get it cheaper than the original accessories.

Warda

As we have seen, the attribute “Price” is still strongly represented in the data, despite the affluence of the respondents. But the consequences it is connected to and the end-value demonstrate the social pressure for over-consumption of luxury items. Next, value “Belonging” portrays in more detail the societal expectations.

Belonging

The desire to “Enhance social status” is the predominant consequence driving participants’ value “Belonging”. Consumers buy the goods that have the attributes of original brands such as the brands’ names or design to conform to social expectations. Participants describe the pressure they face on a daily basis to own and demonstrate branded luxury items.

Show off, yeah. It is to show off and as I told you, they think that it (buying counterfeits) is to show people that we have the money to buy it (luxury brands) and we have the style.

Mosa

People buy counterfeits to convey the image of luxury consumers as expected from them but would like to hide the fact that they own a counterfeited item and “Pretend it’s an original”.

They buy! People tend to buy the fake one, not to tell others that it’s fake. They buy it to convince you that this is an original one. Original brand. Luxury item.

Saleyma

FIGURE 4

Belonging

Furthermore, to be accepted in their society, respondents have to frequently buy many luxury items. They feel the pressure from their society to present the latest trends, continuously “Be in-vogue”, demonstrate that they know the trends and follow the fashion.

Some people say, why spend money when I can buy it for half the price […] because they want to show that they’re part of a certain community and they want to have a lot of options to change their bags all the time because with all this fashionista peep […] Now there’s this new trend of having 10,000 shoes and 10,000 bags and 100 outfits. Every day she’s wearing a new shoe and a new bag and a new outfit and new jewelry.

Nada

The attribute “Accessibility” refers to the fact that the counterfeits can be easily purchased, and “Genuine brand attributes” lead to consequences “Buy more” and “Be in-vogue”.

Sometimes the desired item of the original brand is not available in the country. Especially it applies to limited edition collections. Consumers still want to own these items faster than others, but collections are being sold out too quickly. It is astonishing how fast the counterfeiters react to these demands and supply the market with the latest “IT-items”. Shamka explains that she wanted to buy the original “IT-bag”, but it was not available in the legitimate store, and she subsequently found a counterfeit version. It was “Accessible” and gave her the possibility to “Be in-vogue”.

I say the truth. I have one [fake] bag Dolce and Gabbana - the rare one. I looked for it. For the original one here, they didn’t have it [...] I don’t know. Like, I don’t like waiting. If I want something, I want it now. I will go buy and have it NOW!

Shamka

Data reveals that “Belonging” can be divided into two segments. First, “Belonging” to society, supported by the consequences “Enhance social status” and “Pretend it’s an original”, and the second one is “Belonging” to immediate family circle and close friends, supported by consequence “Feel closer to family and friends”. Consumers don’t want to be identified as counterfeit buyers and refrain from sharing their experiences with counterfeits with the broader audience and normally keep those experiences as “little secret” within a family. This attribute refers to the “secret product” itself, as well as the often-adventurous circumstances under which the counterfeits are purchased or “best practices” about the places and best suppliers of fakes. Respondents have stated that when they buy counterfeits, they like to be accompanied by a family member. These shared experiences and “secret action” enable the consumers to perceive the consequence of “Feeling closer to family and friends”. Mona describes her network of counterfeit sellers and buyers within her family – an experience she could only share with people she trusts:

This lady with her husband went to China. So, in her mind it was to buy fakes and sell them again - like a business. She’s one of our family, you know. It’s like secret you know, because it’s illegal. …So, I told my sister: “common buy from them!” and I said [to sellers]: “she’s my sister!”

Mona

Like Mona, Worood is also describing how she wants to support her close friend who is trying to build a business with counterfeits and help her start-up company.

I have one of my friends with me, she’s my college-mate at college, she used to go to Thailand and buy the fake products, but it looks like original. She has her own business she used to sell them here. […] I would like to support my friend in her business, to help her.

Worood

Noura explains the necessity to keep counterfeit purchases as a secret with the fact that people who are not close to her might tease or judge her for buying counterfeits, so, they have to hide the fact that they engage themselves in such consumption from others.

But, people they don’t (tell others that they have a fake). They could ask me like, my sister for example my sister, they could ask me: this is of real or fake? Because it is really nice, how much? I want to buy it. Like this. Is it real or fake? I could tell my sister if it is fake or not.... But sometimes there comes a lady that she just wants to tease you. Okay?

Noura

Obviously, some consumers opt for counterfeits to cope with the pressure from society, but there are also those who enjoy the process of buying and consuming counterfeits, as the following sections demonstrate.

Hedonism

When referring to the places where respondents buy counterfeits, they mention markets (such as Dragon Mall, Karama market in Dubai or Madinat Zayed market in Abu Dhabi) or markets in Asian countries that remind the consumers of old traditional markets (souqs). Since the country had undergone a fast transformation and “westernization”, many, especially older consumers feel nostalgic about the old times and want to experience enjoyment during adventurous shopping with friends, places they can bargain and prove their negotiation skills, which are traditionally required when shopping on Arabic markets. It is not surprising to observe the link between the attribute “informal consumption” and value “Hedonism” as the purchase process and consumption of counterfeits have a ludic dimension to it. In modern luxury malls, they cannot experience the act of enjoyment while bringing the price of the item down or “hunting” and searching for the “best deal”. Mara describes with excitement her tactics in negotiating the price for counterfeit on the market when she had to leave the shop to demonstrate no interest and then come back to buy the item at a lower price.

Then I kept looking, looking, looking, and asking, and I touched the [item] [...] I asked them (the seller) to see the other, the watch. I wear it (tried it). Then, I kept dealing with them, how about this? Then I left, and then came back.

Mara

It was just one of the shops that we were randomly passing by, and I found the bag to be in very good shape actually, and I was surprised, so they welcomed us. They told us there’s a back place where they keep the secret door. So, when we went there, I saw this stuff, so I thought, why not?

Tarfa

FIGURE 5

Hedonism

Consumers not only experience the thrill when shopping and consuming counterfeits, but also enjoy utilizing the items to boost their self-esteem.

Self-esteem

Consumers have to ensure that the look of the item is the closest to the original, so, it is crucial to control the “Quality” of the items to be able to use them as a deceiving tool. Sometimes it is astonishing how much knowledge it requires to purchase a “good” fake item. Not only all the respondents were aware of different levels of quality of fakes such as A-Level, A-quality or number one fake. It did not seem to be a great challenge for the interviewees to pick the perfect fake, just out of the reason that they know the luxury products and their exact attributes very well (“Genuine brand attributes”) and are eager to apply this knowledge to evaluate the fake and make the right choice or discard the “non-fit”.

For example, Lady Dior, if it’s the original one, it comes hard and the fake - softer, because I compare it to Lady Dior because I have Lady Dior.

Fatma

I bought one time a watch, this one (Shows her real Cartier watch), but not this one. The bigger one… Doesn’t show it is copy… I know how to select the copy.

Mayam

Participants are ready to compromise on minor differences if the shortcomings of the copy are only known to them and are not visible to the others. The ability to clever choose a right item allows them to feel “smart” about their decisions and to demonstrate expertise in luxury (“Smart-shopping, expertise”) building their “Self-esteem”.

If no one will know this bag is fake, it’s okay for me to wear it… I will not take it (bag) because (if) it’s not look like an original. (If) It looks like original, I would take it, but if not, I will not accept it.

Warda

Remarkably, there is another group of consumers who are motivated to enhance their self-esteem through announcement to the broad audience that they buy fakes and are not afraid to admit it.

Honestly, I once heard a lady from a very well-known family, people who are really rich, and they can afford it. However, she says that, “I do buy fake bags.” And we told her, “How come? Like you’re from this family, how come you’re buying a fake bag?” She said, “Who would ever expect me not carrying a real bag?”

Samiya

Concluding it can be noticed that the value “Self-esteem” is linked to the attribute “Quality”. In fact, respondents refer to counterfeits as an inferior version of genuine items but love their own ability to assess the quality very precisely and feel smart about their purchase decisions.

FIGURE 6

Self-esteem

Conclusion and Implications

Theoretical Contribution

This article contributes to the nascent but expanding field of luxury counterfeit research and consumers’ motivations underlying such controversial behavior, and demonstrates that cultural aspects play an important role in such consumption proving that counterfeiting is not “culture free” (Eisend et al., 2017; Santos and Ribeiro, 2006). Despite having received attention from academia, the more profound understanding of motivations that underlie counterfeit consumption is still scarce.

This research demonstrates the importance of various motivations beyond the traditional monetary advantages. It confirms that in specific cultural settings, where the citizens have undergone a rapid cultural and economic change, even the affluent luxury consumers who possess enough means to purchase the original, turn to shadow markets (Pueschel et al., 2017). Consequently, the findings do not appear to validate the view that consumers who start having the income to afford the genuine brand, no longer purchase counterfeits (Eisend et al., 2017; Wee et al., 1995; Yoo and Lee, 2012).

This research had identified four dominant motives for luxury counterfeit consumption: “Value Consciousness”, “Belonging”, “Hedonism” and “Self-esteem”.

The identified motive “Value Consciousness” was rather unexpected, as the sample consisted of affluent luxury consumers. Although, the attribute “Price” is strong in the data, in contrast to previous findings that suggest that consumers buy fakes purely for their economic benefits (Dodge et al., 1996; Harvey and Walls, 2003; Prendergast et al., 2002; Yoo and Lee, 2012), this research demonstrated that affluent consumers purchase counterfeits for other reasons rather than purely monetary ones. Precisely, the results show that experiencing the pressure from their society to present new looks on a regular basis, consumers are unwilling or unable to spend the allocated amount on luxury goods every month. Thus, counterfeits allow them to increase the number of goods they can purchase. The diversity of fake goods and designs allow respondents to satisfy the desire for self-presentation as fashion forward and “in-vogue”, moreover, to own the pieces faster than the others in the reference group, demonstrate them either at work, at their traditional gatherings on Fridays, or in public places.

The present research has identified a new dimension in counterfeit consumption: desire to “invest”, and can expand our understanding of consumers’ needs and motivations. Consumers’ desire to “Invest” their money in gold jewelry that copies the design of luxury brands seems not to get enough attention from researchers yet. At this point, it is important to understand how this product category is perceived. The results have shown that consumers seem not to differentiate much between fashion and fine jewelry due to its “fashion factor” and changing collections of luxury fine jewelry. To them, the counterfeited versions of fine jewelry, when it is made out of real gold, are “recyclable”. This type of counterfeit items is widely available in gold markets (shopping malls dedicated to fine jewelry only) and not only looks like the original item from the outside, but also carries the necessary brand names and serial numbers of the genuine item, although, these details can only be seen in a very close examination. Furthermore, these fakes are extremely hard to identify as such, even by a specialist, and often require a gemologist who is specialized in luxury fine jewelry to detect the differences in stones and settings of the fake (Vogue, 2017). The respondents stressed the fact that gold retains its’ value over time and can be easily “recycled” into a new item when the piece has been already demonstrated in public for a certain period. As a consequence, consumers view this process as a creative way to update their looks according to the trends.

The strongest motive for counterfeit consumption that has thus been identified is “Belonging”. This result can be vindicated through societal structure and development since the country formation in 1971. The society in the UAE has had a very rapid transition. The discovery of oil has enabled a fast accumulation of wealth for the country and its’ citizens. Newer and bigger malls appear every year; new brands are constantly opening their shops in the region. Luxury brands are trying to overbid each other by offering consumers the latest trends, inviting them to purchase more and more. Among UAE nationals, luxury became a part of their daily life, and the society expects from its members to own and demonstrate the latest trends from best luxury houses. The results show the desire to uphold the expectations of the community (“Belonging”) through status-related motives (Cordell et al., 1996): “Enhance social status”. Demonstration of wealth in the UAE through highly visible social symbols is inevitable and allows better probabilities of climbing the social ladder. (Vel et al., 2011). This phenomenon can be also observed in other countries, where the economic development led to the formation of the “nouveau riche” class. Such is the case in China (Jiang and Cova, 2012), where the consumers experience similar pressure to present the luxury items in order to belong to the aspired group. For GCC consumers this desire of belonging is not easily satisfied purely with brand names or designs but rather through “overconsumption” of luxury goods: original or counterfeit.

Since counterfeits provide good value (Thaichon and Quach, 2016), consumers explain the possibility to use the difference they saved in more honorable ways: such as donating to a charity, building mosques or helping others and not splurging on overpriced luxury products, as “wasting” is considered as a sin in Islam. Nevertheless, the consequence “uphold religion” can be, in this context, regarded as a neutralization technique (Bian et al., 2016) or coping strategy to deal with moral risk (Pueschel et al, 2017), as it helps the consumers to deal with cognitive dissonance, gain social approval, or at least avoid social judgement, when reporting their counterfeit consumption or in case they are identified as a counterfeit consumer, through reference to “divine intentions” (Alserhan, 2010).

Further, since consumers in the present sample are purchasing counterfeits not to use them over a longer period but to adopt the “trendy look”, counterfeits seem to match perfectly the buyers’ needs (Tang et al., 2014; Thaichon and Quach, 2016). They are disposable, one the trendy item can be easily replaced by another. Furthermore, consumers feel smart about their ability not only to save money and update the wardrobes but also about their ability to utilize the knowledge of original brands to purchase the “perfect” fake.

Another surprising finding refers to the value “Self-Esteem”. Previous research has supported the idea that consumers acquire counterfeits to boost their self-esteem (Sharma and Chan, 2017; Stöttinger and Penz, 2015). Interestingly, it the case of GCC consumers, where almost everyone can buy originals and everyone can buy counterfeits, it comes to the fact that not everyone can have status and the confidence to talk about their counterfeit purchase to others and without the fear to be judged.

Furthermore, consumers fulfill their hedonic needs (value “Hedonism”) through shopping for fake items on markets where they can bargain and negotiate the prices like on old traditional Arabic souq. Similar experiences were reported by Gistri et al. (2009) and Hansen and Møller (2017) where consumers satisfy their ego by getting a discount and enjoy bargains which provide an additional source of psychological value (Darke and Dahl, 2003). Although the product is fake, the experience is real, especially when enjoyed with family and close friends.

Many academics have studied counterfeit consumers across various nations (Penz and Stöttinger, 2008; Rawlinson and Lupton, 2007; Teah et al., 2015; Veloutsou and Bian, 2008); however, there is still very little research exploring counterfeit consumers in Muslim countries (Riquelme et al., 2012).

Managerial Implications

The present research is the first exploratory investigation concerning the motives of affluent consumers in GCC countries to purchase counterfeits. Since consumer behavior has to be understood within a cultural context (De Mooij and Hofstede, 2011), the awareness of identified motivation patterns can help managers of luxury brands and policymakers to design effective brand protection strategies and foster the anti-counterfeiting campaigns.

This research has identified four main motivational patterns that are all strongly influenced by the culture in the UAE. It implies that brand managers could tailor their strategies to meet the needs of the ethnic minority segment (UAE nationals represent 15% of the population in the UAE) and might design unique formats to reach this segment. Since the GCC consumers are among major consumers of luxury goods (Bain & Company, 2017), luxury brands may consider strengthening communication with the consumers. The emphasis should be put on long-term investment in the originals versus short-term financial gratification from the purchase of the fakes. Luxury brands are not just selling goods, but creating stories, which in their turn create emotional connections. These stories make the brands and the items unique. By buying original items, consumers buy uniqueness and sometimes they need to overcome some cultural barriers to be able to enjoy the product (Kapferer and Bastien, 2009). Companies need to stress that along with the superior quality of the products and the craftsmanship comes the assurance that original goods are an investment, not only monetary one but also a cultural investment and the development of a good taste, something that no fake product can offer.

To elaborate on the fact that consumers still desire for a “chase of a good deal”, retail stores might offer private sale events. Although those should be offered very selectively, involving only specific products accessible only to specific customers, over a strictly limited period of time, in order not to destroy the worth of the brand (Keller, 2017). Besides, stressing on the fact that when consumers want to experience the “thrill” when buying counterfeits, luxury brands need to extend their experiential marketing strategies. These strategies might look beyond the traditional fashion shows, where the customer is a passive viewer, but at developing an interaction where the seller and the customer co-create the experience (Atwal and Williams, 2017). For instance, customers may experience the same fashion show running in Paris through the virtual reality device in Dubai or be “teleported” to another store around the world and experience the shopping in a different setting. Further, stressing on the value “Be in-vogue”, the approach “see now, buy now” that enjoys popularity among luxury houses recently (e.g., Burberry, Moschino, Ralph Lauren), and enables the consumers to purchase the collections fresh off-the-runway, could limit the immediate access of counterfeiters to the products.

As the value “Belonging” is linked to status consumption, policy makers can create an advertisement campaign “someone will spot a fake anytime” or “no saved money is worth the embarrassment”. Finally, since the government of the UAE strives to ensure sustainable development in the country, creating the balance between economic and social development (Vision 2021), policymakers may want to create a campaign signaling that “originals are cheaper in the long run” (Staake and Fleisch, 2008, p. 54).

Limitations And Further Research

The study is exploratory in nature and is purely based on qualitative methods. The data analysis used in this research was performed by a single researcher, which might affect the intra-coder reliability. It could be beneficial to test the motivational drivers employing quantitative survey and identify the controls of different motivations and their influence on counterfeit consumption choices. The replication of this research in other affluent Muslim countries could provide additional insights into cultural aspects influencing the motivations to purchase counterfeits.

Parties annexes

Biographical note

Julia Pueschel is Assistant professor of marketing at Neoma Business School. She was awarded a Ph.D. in management sciences at Université Paris Dauphine, PSL University, Paris. Prior to becoming an academic, she worked in business organizations in the United Arab Emirates as a member of higher management and had developed an interest in studying luxury brands and consumer behavior. Her primary research interest is in luxury counterfeit consumption, luxury consumption, consumer behavior and qualitative research methods.

Bibliography

- Al-Issa, Ahmad (2017). “English As a Medium of Instruction and the Endangerment of Arabic literacy: The Case of the United Arab Emirates,” Arab World English Journal, Vol. 8, N° 3, p. 3-17.

- Alserhan, Baker Ahmad (2010). “On Islamic Branding: Brands as Good Deeds,” Journal of Islamic Marketing, Vol. 1, N° 2, p. 101-6.

- Amaral, Nelson B.; Loken, Barbara (2016). “Viewing Usage of Counterfeit Luxury Goods: Social Identity and Social Hierarchy Effects on Dilution and Enhancement of Genuine Luxury Brands,” Journal of Consumer Psychology, Vol. 26, N° 4, p. 483-95.

- Ang, Swee Hoon; Cheng, Peng Sim; Lim, Elison A.C.; Tambyah, Siok Kuan (2001). “Spot the Difference: Consumer Response towards Counterfeits,” Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 18, N° 3, p. 219-35.

- Atwal, Glyn; Williams Alistair (2017). “Luxury Brand Marketing – The Experience Is Everything!” In J-N. Kapferer, J. Kernstock, T.Brexendorf, S. Powell (Eds) Advances in Luxury Brand Management. Journal of Brand Management: Advanced Collections. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, p. 43-57.

- Bain & Company (2017). “Global Personal Luxury Goods Market Expected to Grow by 2-4 Percent to €254-259bn in 2017, Driven by Healthier Local Consumption in China and Increased Tourism and Consumer Confidence in Europe.” Bain & Company. Retrieved December 15, 2018, from https://www.bain.com/about/media-center/press-releases/2017/global-personal-luxury-goods-market-expected-to-grow-by-2-4-percent

- Baker, Susan; Thompson, Keith E; Engelken, Julia; Huntley, Karen (2004). “Mapping the Values Driving Organic Food Choice,” European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 38, N° 8, p. 995-1012.

- Bian, Xuemei; Wang, Kai Yu; Smith, Andrew; Yannopoulou, Natalia (2016). “New Insights into Unethical Counterfeit Consumption,” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 69, N° 10, p. 4249-58.

- Burgess, Steven Michael; Steenkamp, Jan Benedict E.M. (2006). “Marketing Renaissance: How Research in Emerging Markets Advances Marketing Science and Practice,” International Journal of Research in Marketing, Vol. 23, N° 4, p. 337-56.

- Cordell, Victor V.; Wongtada, Nittaya; Kieschnick, Robert L. (1996). “Counterfeit Purchase Intentions: Role of Lawfulness Attitudes and Product Traits as Determinants.,” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 35, N° 1, p. 41-53.

- Darke, Peter R.; Dahl, Darren (2003). “Fairness and discounts: the subjective value of a bargain,” Journal of Consumer Psychology, Vol. 13, N° 3, p. 328-38.

- De Matos, Augusto Celso; Ituassu, Cristiana Trindade; ROSSI, Carlos Alberto Vargas (2007). “Consumer Attitudes toward Counterfeits: A Review and Extension,” Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 24, N° 1, p. 36-47.

- Dodge, Robert; Edwards, Elizabeth; Fullerton, Sam (1996). “Consumer Transgressions in the Marketplace: Consumers’ Perspectives,” Psychology and Marketing, Vol. 13, N° 8, p. 821-35.

- Eisend, Martin; Schuchert-Güler, Pakize (2006). “Explaining Counterfeit Purchases: A Review and Preview,” Academy of Marketing Science Review, Vol. 10, N° 12, p. 214-29.

- Eisend, Martin (2019). “Morality Effects and Consumer Responses to Counterfeit and Pirated Products: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 154, N° 2 p. 301-23.

- Eisend, Martin; Hartmann, Patrick; Apaolaza, Vanessa (2017). “Who Buys Counterfeit Luxury Brands? A Meta-Analytic Synthesis of Consumers in Developing and Developed Markets,” Journal of International Marketing, Vol. 25, N° 4, p. 89-111.

- Fernandes, Cedwyn (2013). “Analysis of Counterfeit Fashion Purchase Behaviour in UAE,” Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, Vol. 17, N° 1, p. 85-97.

- Franses, Philip Hans; Lede, Madesta (2015). “Cultural Norms and Values and Purchases of Counterfeits,” Applied Economics, Vol. 47, N° 54, p. 5902-16.

- Gengler, Charles E.;.Thomas J. (1995). “Consumer Understanding and Advertising Strategy: Analysis and Strategic Translation of Laddering Data,” Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 35, N° 4, p. 19-33.

- Gentry, James W.; Putrevu, Sanjay; Shultz, Clifford J. (2006). “The Effects of Counterfeiting on Consumer Search,” Journal of Consumer Behaviour, Vol. 5, N° 3, p. 245-56.

- Gistri, Giacomo; Romani, Simona; Pace, Stefano; Gabrielli, Veronica; Grappi, Silvia (2009). “Consumption Practices of Counterfeit Luxury Goods in the Italian Context,” Journal of Brand Management, Vol. 16, N° 5-6, p. 364-74.

- Gosline, Renee (2010), “Counterfeit Labels: Good For Luxury Brands?” Retrieved December 15, 2017, from www.forbes.com/2010/02/11/luxury-goods-counterfeit-fakes-chanel-gucci-cmo-network-renee-richardson-gosline.html#2cc430ea4f54

- Guido, Gianluigi; Amatulli, Cesare; Peluso, Alessandro M. (2014). “Context Effects on Older Consumers’ Cognitive Age: The Role of Hedonic versus Utilitarian Goals,” Psychology and Marketing, Vol. 31, N° 2, p. 103-14.

- Gutman, Jonathan (1982). “A Means-End Chain Model Based on Consumer Categorization Processes,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 46, N° 2, p. 60-72

- Hamelin, Nicolas; Nwankwo, Sonny; El Hadouchi, Rachad (2013). “‘Faking Brands’: Consumer Responses to Counterfeiting,” Journal of Consumer Behaviour, Vol. 12, N° 3, p. 159-70.

- Hansen, Gard Hopsdal; Møller, Henrik Kloppenborg (2017). “Louis Vuitton in the Bazaar: Negotiating the Value of Counterfeit Goods in Shanghai’s Xiangyang Market,” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, Vol. 30, N° 2, p. 170-90.

- Harvey, Patrick J.; Walls, David W. (2003). “Laboratory Markets in Counterfeit Goods: Hong Kong versus Las Vegas,” Applied Economics Letters, Vol. 10, N° 14, p. 883-87.

- INTA (2017). Global impacts of counterfeiting and piracy to reach US $4.2 trillion by 2022. Retrieved December 15, 2017, from https://www.inta.org/Press/Pages/Counterfeiting_Impact_Study_Press_Release.aspx

- Jiang, Ling; Cova, Veronique (2012). “Love for Luxury, Preference for Counterfeits –A Qualitative Study in Counterfeit Luxury Consumption in China,” International Journal of Marketing Studies, Vol. 4, N° 6, p. 1-10.

- Jiang, Ling; Shan, Juan (2016). “Counterfeits or Shanzhai? The Role of Face and Brand Consciousness in Luxury Copycat Consumption,” Psychological Reports, Vol. 119, N° 1, p. 181-99.

- Jirotmontree, Atthaphol (2013). “Business Ethics and Counterfeit Purchase Intention: A Comparative Study on Thais and Singaporeans,” Journal of International Consumer Marketing, Vol. 25, N° 4, p. 281-88.

- Kapferer, Jean-Noël; Bastien Vincent (2009). “The Specificity of Luxury Management: Turning Marketing Upside Down.” Journal of Brand Management, Vol. 16, N° 5-6, p. 311-22.

- Kapferer, Jean-Noël; Michaut, Anne (2014). “Luxury Counterfeit Purchasing: The Collateral Effect of Luxury Brands’ Trading down Policy,” Journal of Brand Strategy, Vol. 3, N° 1, p. 59-70.

- Kaufmann, Hans R. Petrovici, Dan A.; Filho, Cid G.; Ayres, AdriaN° (2016). “Identifying Moderators of Brand Attachment for Driving Customer Purchase Intention of Original vs Counterfeits of Luxury Brands,” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 69, N° 12, p. 5735-47.

- Keller, Kevin Lane (2017). “Managing the Growth Tradeoff: Challenges and Opportunities in Luxury Branding.” In Kapferer J-N., Kernstock J., Brexendorf T., Powell S. (Eds) Advances in Luxury Brand Management. Journal of Brand Management: Advanced Collections. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, p. 179-98.

- Lin, Chin-Feng (2002). “Attribute-Consequence-Value linkages: A new technique for understanding Customers’ Product Knowledge,” Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, Vol. 10, N° 4, p. 339-52.

- Martinez, Luis F; Jaeger, Dorothea S. (2016). “Ethical Decision Making in Counterfeit Purchase Situations: The Influence of Moral Awareness and Moral Emotions on Moral Judgment and Purchase Intentions,” Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 33, N° 3, p. 213-23.

- Miles, Matthew B.; Huberman, Michael A.; Saldana, Johnny (2014). Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. Sage Publications, 408 p.

- Mirosa, Miranda; Tang Sharon (2016). “An Exploratory Qualitative Exploration of the Personal Values Underpinning Taiwanese and Malaysians’ Wine Consumption Behaviors,” Beverages, Vol. 2, N° 1, p. 1-22.

- Mitchell, Vincent W. (1992). “Understanding Consumers’ Behaviour: Can Perceived Risk Theory Help?” Management Decision, Vol. 30, N° 3, p. 26-31.

- Moschis, George P.; Churchill, Gilbert A. (1978). “Consumer Socialization: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis,” Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 15, N° 4, p. 599-609.

- Mowen, John C.; Minor, Michael (1995). Consumer Behavior, Prentice Hall International, Inc. NJ, 5e, 595 p.

- OECD (2017). Mapping the Real Routes of Trade in Fake Goods, OECD Publishing. 154 p.

- Penz, Elfriede; Stöttinger, Barbara (2008). “Original Brands and Counterfeit Brands—do They Have Anything in Common?” Journal of Consumer Behaviour, Vol. 7, N° 2, p. 146-63.

- Perez, María Eugenia; Castaño, Raquel; Quintanilla, Claudia (2010). “Constructing Identity through the Consumption of Counterfeit Luxury Goods,” Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, Vol. 13, N° 3, p. 219-35.

- Phau, Ian; Teah, Min (2009). “Devil Wears (Counterfeit) Prada: A Study of Antecedents and Outcomes of Attitudes towards Counterfeits of Luxury Brands,” Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 26, N° 1, p. 15-27.

- Prendergast, Gerard; Chuen, Leung Hing; Phau, Ian (2002). “Understanding Consumer Demand for Non-Deceptive Pirated Brands,” Marketing Intelligence & Planning, Vol. 20, N° 7, p. 405-16.

- Pueschel, Julia; Chamaret, Cécile; Parguel, Béatrice (2017). “Coping with Copies: The Influence of Risk Perceptions in Luxury Counterfeit Consumption in GCC Countries,” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 77, p. 184-94.

- Rawlinson, David R.; Lupton, Robert (2007). “Cross-National Attitudes and Perceptions Concerning Software Piracy: A Comparative Study of Students From the United States and China,” Journal of Education for Business, Vol. 83, N° 2, p. 87-94.

- Reynolds, Thomas J.; Gutman, Jonathan (1988). “Laddering Theory, Method, Analysis and Interpretation,” Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 28, N° 1, p. 11-31.

- Reynolds, Thomas J.; Phillips, Joan M. (2008). “A review and comparative analysis of laddering research methods,” in Naresh K. Malhotra (ed.) Review of Marketing Research, Volume 5, p. 130-174.

- Riquelme, Hernan E; Abbas Mahdi S., Eman; Rios, Rosa E. (2012). “Intention to Purchase Fake Products in an Islamic Country,” Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues, Vol. 5, N° 1, p. 6-22.

- Rokeach, Milton (1973), The Nature of Human Value, Free Press, NewYork, NY, 438 p.

- Ronkainen, Ilkka A; Guerrero-Cusumano, Jose-Luis (2001). “Correlates of Intellectual Property Violations,” Multinational Business Review, Vol. 9, N° 1, p. 59-65.

- Rosenbaum, Mark S; Cheng, Mingming; Wong, Ipkin Anthony (2016). “Retail Knockoffs: Consumer Acceptance and Rejection of Inauthentic Retailers,” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 69, N° 7, p. 2448-55.

- Rutter, Jason; Bryce, Jo (2008). “The Consumption of Counterfeit Goods: ‘Here Be Pirates?” Sociology, Vol. 42, N° 6, p. 1146-64.

- Ryan, Richard M.; Deci, Edward L (2000). “Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being,” American Psychologist, Vol. 55, N° 1, p. 68-78.

- Santos, Freitas; Ribeiro, Cadima (2006). “An Exploratory Study of the Relationship between Counterfeiting and Culture,” Tékhne-Revista de Estudos Politécnicos, Vol. 3, No. 5-6 (June) p. 227-43.

- Sharma, Piyush; Chan, Ricky Y. K. (2011). “Counterfeit Proneness: Conceptualisation and Scale Development,” Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 27, N° 5-6, p. 602-26.

- Sharma, Piyush; Chan, Ricky Y. K. (2016). “Demystifying Deliberate Counterfeit Purchase Behaviour,” Marketing Intelligence & Planning, Vol. 34, N° 3, p. 318-35.

- Sharma, Piyush; Chan, Ricky Y. K. (2017). “Exploring the Role of Attitudinal Functions in Counterfeit Purchase Behavior via an Extended Conceptual Framework,” Psychology and Marketing, Vol. 34, N° 3, p. 294-308.

- Staake, Thorsten; Fleisch, Elgar (2008). Countering Counterfeit Trade: Illicit Market Insights, Best-Practice Strategies, and Management Toolbox, Springer, Berlin, 231 p.

- Stöttinger, Barbara; Penz, Elfriede (2015). “Concurrent Ownership of Brands and Counterfeits: Conceptualization and Temporal Transformation from a Consumer Perspective,” Psychology and Marketing, Vol. 32, N° 4, p. 373-91.

- Tang, Felix; Tian, Vane-Ing; Zaichkowsky, Judy (2014). “Understanding Counterfeit Consumption,” Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 26, N° 1, p. 4-20.

- Tauber, Edward (1972). “Marketing Notes And Communications,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 36, N° 4, p. 46-59.

- Teah, Min; Phau, Ian; Huang, Yu-an (2015). “Devil Continues to Wear ‘counterfeit’ Prada: A Tale between Two Chinese Cities,” Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 32, N° 3, p. 176-89

- Thaichon, Park; Quach, Sara (2016). “Dark Motives-Counterfeit Purchase Framework: Internal and External Motives behind Counterfeit Purchase via Digital Platforms,” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Vol. 33, p. 82-91.

- The National (2019). “Dubai Seizes More than Dh330 Million Worth of Fake Goods”. Retrieved March 20, 2019, from https://www.thenational.ae/uae/dubai-seizes-more-than-dh330-million-worth-of-fake-goods-1.819655

- The National (2019).”Dubai Shuts down 14,000 Social Media Accounts for Selling Fake Goods” Retrieved March 11, 2019, from https://www.thenational.ae/uae/dubai-shuts-down-14-000-social-media-accounts-for-selling-fake-goods-1.833516

- Tom, Gail; Garibaldi, Barbara; Zeng, Yvette; Pilcher, Julie (1998). “Consumer Demand for Counterfeit Goods.,” Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 15, N° 5, p. 405-21.

- Trinh, Viet-Dung; Phau, Ian (2012). “The Overlooked Component in the Consumption of Counterfeit Luxury Brands Studies: Materialism - A Literature Review,” Contemporary Management Research, Vol. 8, N° 3, p. 251-63.

- Valette-Florence, Pierre (1998). “A Causal Analysis of Means-End Hierarchies in a Cross-Cultural Context: Methodological Refinements.,” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 42, N° 2, p. 161-66.

- Vel, K Prakas; Captain, Alia; Al-Abbas, Rabab; Al Hashemi, Balqees (2011). “Luxury Buying in the United Arab Emirates,” Journal of Business and Behavioural Sciences, Vol. 23, N° 3, p. 145-60.

- Veloutsou, Cleopatra; Bian, Xuemei (2008). “A Cross-National Examination of Consumer Perceived Risk in the Context of Non-Deceptive Counterfeit Brands,” Journal of Consumer Behaviour, Vol. 7, N° 1, p. 3-20.

- Vogue (2017) The Fightback On Counterfeit Designer Goods. Retrieved June 10, 2018, from http://www.vogue.co.uk/article/fake-designer-goods-counterfeit-pieces

- Wang, Fang; Zhang, Hongxia; Zang, Hengjia; Ouyang, Ming (2005). “Purchasing Pirated Software: An Initial Examination of Chinese Consumers,” Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 22, N° 6, p. 340-51.

- Wansink, Brian (2000). “New Techniques to Generate Key Marketing Insights,” Marketing Research, Vol. 12, N° 2, p. 28-36.

- Wansink, Brian (2003). “Using Laddering to Understand and Leverage a Brand’s Equity,” Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, Vol. 6, N° 2, p. 111-18.

- Wee, Chow‐Hou; Ta, Soo‐Jiuan; Cheok, Kim‐Hong (1995). “Non‐price Determinants of Intention to Purchase Counterfeit Goods,” International Marketing Review, Vol. 12, N° 6, p. 19-46.

- Wilcox, Keith; Kim, Hyeong Min; Sen, Sankar (2009). “Why Do Consumers Buy Counterfeit Luxury Brands?” Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 46, N° 2, p. 247-59.

- World Bank (2018). Retrieved June 10, 2018, http://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/GNIPC.pdf

- Yoo, Boonghee; Lee, Seung Hee (2012). “Asymmetrical Effects of Past Experiences with Genuine Fashion Luxury Brands and Their Counterfeits on Purchase Intention of Each,” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 65, N° 10, p. 1507-15.

Parties annexes

Note biographique

Julia Pueschel est Professeur Assistant à Neoma Business School. Elle est titulaire d’un doctorat en Sciences de Gestion de l’Université Paris Dauphine, PSL, Paris. Avant d’entamer une carrière académique, elle a travaillé dans des postes de direction dans différentes entreprises aux Émirats Arabes-Unis et a développé un intérêt pour l’étude des marques de luxe et du comportement des consommateurs. Ses recherches portent principalement sur la consommation de produits de luxe originaux et contrefaits, le comportement des consommateurs et les méthodes de recherche qualitatives.

Parties annexes

Nota biográfica

Julia Pueschel es Profesor Adjunto en la Neoma Business School. Es Doctora en Ciencias Empresariales por la Universidad Paris Dauphine, PSL Universidad, Paris. Antes de dedicarse a esta carrera académica, ella ha trabajado para organizaciones empresariales de los Emiratos Árabes Unidos como miembro de dirección de empresa, dedicándose con especial interés a la investigación de las marcas de lujo y al comportamiento de los consumidores. Su interés primordial es la investigación del consumo y de los artículos de lujo, así como del comportamiento de los consumidores y de los métodos cualitativos de la investigación.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Overview of Means-End Chain elements

FIGURE 2

Hierarchical Value Map

FIGURE 3

Value – Consciousness

FIGURE 4

Belonging

FIGURE 5

Hedonism

FIGURE 6

Self-esteem

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Respondents

Table 2

Implication matrix