Abstracts

Abstract

This study examines the effects of French small- and medium-sized enterprises’ (SMEs) internationalization on these firms’ bank financing. Using exporting activity and internationalization through foreign subsidiaries as proxy variables, we empirically examine the consequences of these two modes of internationalization on these firms’ bank debt ratios. Based on a dataset of French SMEs, the results show that exporting SMEs have more difficulty obtaining bank debt than those with subsidiaries abroad, SME’s exporting intensity is negatively associated with their bank debt ratios and foreign subsidiaries’ geographic proximity to their home firms is positively associated with SMEs’ bank debt ratios. These results suggest that each mode of internationalization leads to different financing behaviors.

Keywords:

- SME,

- Internationalization,

- Exportation,

- Subsidiary,

- Bank Financing

Résumé

Cette étude examine l’impact de l’internationalisation des PME françaises sur leur financement bancaire. Plus spécifiquement, nous étudions empiriquement les conséquences de l’internationalisation par l’export et la filiale sur le ratio d’endettement bancaire. En s’appuyant sur un échantillon de PME, nos résultats montrent que les PME exportatrices ont plus de difficultés à obtenir des dettes bancaires contrairement à celles qui ont des filiales à l’étranger. Nous constatons également que l’intensité d’exportation des PME est négativement associée à leurs ratios d’endettement bancaire. En outre, nos résultats montrent aussi que la proximité géographique des filiales étrangères avec leurs maisons mères est positivement associée au ratio d’endettement bancaire. En fin, notre recherche suggère que chaque mode d’internationalisation conduit à des comportements de financement différents.

Mots-clés :

- PME,

- Internationalisation,

- Exportation,

- Filiale,

- Financement bancaire

Resumen

Este estudio examina los efectos de la internacionalización y la financiación bancaria de las PYMES francesas.Utilizando la actividad exportadora y la internacionalización a través de filiales extranjeras como variables proxy, examinamos empíricamente las consecuencias de estos dos modos de internacionalización sobre los ratios de endeudamiento bancario de estas empresas. Los resultados muestran que las PYMES exportadoras tienen más dificultades para obtener deuda bancaria que las que tienen filiales en el extranjero, la intensidad exportadora de las PYMES se asocia negativamente con sus ratios de deuda bancaria y la proximidad geográfica de las filiales extranjeras a sus empresas de origen se asocia positivamente con ratios. Estos resultados sugieren que cada modo de internacionalización conduce a diferentes comportamientos de financiación.

Palabras clave:

- PYMES,

- Internacionalización,

- Exportación,

- Filial,

- Financiación bancaria

Article body

For numerous French small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), international markets make it possible to achieve better sales margins (Bourcieu, 2012). Bpifrance (2018) underlines the fact that an international presence considerably reinforces a company’s appeal and that, in 2016, of France’s 124,000 exporting companies, 95% were very small businesses. While SMEs traditionally concentrate their activity on national markets, they are increasingly turning toward markets abroad. However, many studies indicate a lack of financing as an important obstacle to these firms’ internationalization. In addition, in most OECD countries, there has been an evolution in short-term versus long-term loan portfolios for SMEs (OECD, 2018). This situation is worrying to the extent that bank debt, often of short maturity, constitutes SMEs’ most commonly used source of external financing. SMEs depend on bank debt to meet their financing needs. According to Bpifrance (2018), French SMEs are reluctant to resort to the financial markets for funding (bonds, IPOs, etc.) and their investments are mainly 51% self-financed and 46% financed through bank debt. Moreover, unlike large firms, they cannot substitute short -with long-term financing (long-term debt, equity) as easily as large firms, due to the difficulties in obtaining long-term debt from banks (Maes et al., 2019). Finally, bank loans of shorter maturities mitigate the problems of borrower risk and information asymmetry that characterize SMEs (Ortiz-Molina and Penas, 2008).

This paper studies the relationship between limited access to bank financing and the internationalization of French SMEs through exporting and the establishment of foreign subsidiaries. First, it examines the effect of exports on French SMEs’ access to bank debt. Indeed, SMEs turn to external financing when financing exports, as they seek loans from banks first and foremost (Rahaman, 2011). Previous studies show both negative and positive relationships between financing or SMEs’ debt-to-equity ratios and their export activities. Several papers find a negative relationship between SMEs’ bank financing and their export intensity; specifically, they find that these firms’ export activities increase their credit risk and that their monitoring costs reduce banks’ incentives to finance exporting SMEs (Benkraiem and Miloudi, 2014; Pinto and Silva, 2021). However, some authors argue that exports increase SMEs’ access to bank financing by reducing their financial constraints (Greenaway et al., 2007; Bellone et al., 2010).

The second objective is to examine the impact of internationalization via the foreign subsidiary on the bank financing of French SMEs. In expanding internationally, these firms can establish themselves abroad by creating foreign subsidiaries. For example, in 2018, French multinational SMEs (excluding the banking and financial services) controlled nearly 17% of all French subsidiaries abroad (Insee, 2018). Subsidiaries are a more-advanced mode of internationalization; they facilitate better integration in host countries and require more resources (Slangen and Tulder, 2009). The French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies shows that, in 2013, the median number of countries in which French SMEs were located was three. Consequently, it seems to us that even though French SMEs internationalize through exporting, the creation of subsidiaries abroad has become an important mode of internationalization that deserves to be examined.

Internationalization requires acquiring knowledge about the targeted foreign markets and deploying new financial resources. It is therefore understandable that the willingness of SMEs to internationalize is likely to pose challenges for these firms in terms of accessing various sources of financing, including bank loans. In their quest for internationalization, SMEs are dependent on banks as the main providers of capital (De Maeseneire and Claeys, 2012) and international risk management (Benkraiem and Miloudi, 2014).

Through this enquiry, we analyze whether our results differ from those of previous studies. To our knowledge, no research has examined the impact of French SMEs’ internationalization, in the form of foreign subsidiaries, on their access to bank financing. Our article contributes to the literature by extending the criteria necessary for understanding the dimensions and processes of SMEs’ access to bank financing. Unlike existing works that study only the link between internationalization (measured by export intensity) and SMEs’ financing, we contribute to the literature by examining the relationship between internationalization (as measured by both exports and foreign subsidiaries) and bank debt. Previous research tested whether export intensity or being an exporter affects the capital structure or financing of SMEs. We consider that while SMEs certainly internationalize through export operations, foreign subsidiaries also play an important role here (Rugman and Oh, 2011). We measure this form of internationalization according to SMEs’ subsidiary ownership (one or more) abroad and the number of countries in which these subsidiaries are located (Rugman and Oh, 2011). We supplement the usual indicators of the intensity of French SMEs’ internationalization with further variables, such as the number of subsidiaries and their locations both inside and outside of Europe; thus, measuring the geographic scope of French SMEs’ internationalization.

This study also contributes to the literature by filling a gap in relation to the company size and the mode of internationalization. Indeed, even if several previous studies investigated the impact of internationalization on SMEs’ leverage (Lindner et al., 2018), most of these papers’ themes focused on large listed companies and very few recent studies investigated SMEs in relation to their leverage. SMEs’ choices regarding their mode of internationalization and financing differ from those of the listed firms studied. SMEs’ biggest internationalization challenge lies in their greater information opacity and higher risk of bankruptcy compared to larger enterprises. In fact, SMEs do not have the same specificities as large multinational companies nor do they incur the same types of risks or costs when they internationalize (Steinhäuser et al., 2020).

Using data on French SMEs for the period 2013 to 2018, our results show the existence of a negative and significant relationship between bank indebtedness and French SMEs’ exporting and exporting intensities. Our research also demonstrates the existence of a significant positive relationship between internationalization through having at least one subsidiary abroad, the intensity of this mode of internationalization, and the bank-debt ratio.

This article proceeds as follows. In the next sections, we present exporting and the subsidiary abroad as two distinct modes of internationalization before reviewing the literature on the links between internationalization and SMEs’ access to banking credit. We also present the theoretical foundations and hypotheses of our study, followed by our data and methodology and a discussion of our results. The final section concludes.

Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

Exporting and subsidiaries abroad: two distinct modes of internationalization

Internationalization is not an easy means of achieving business growth because it requires implementing a mode of internationalization that can effectively manage activities abroad (De Bonis et al., 2015). This approach should allow an enterprise to carry out export operations or production and marketing in a foreign country, either alone or in partnership with other enterprises through the subsidiary. Thus, to carry out activities abroad, SMEs may choose to export and/or establish subsidiaries (Lindstrand and Lindbergh, 2011).

Exporting is the first step in establishing a company abroad. This mode of internationalization is generally adopted by firms wishing to sell abroad while also limiting their restructuring costs (low organizational costs) and investing only moderately. According to Gkypali et al. (2021), SMEs employ exporting as a foreign market entry mode, during their first stage of internationalization, due to its relatively low risk, high degree of flexibility, and low commitment of resources.

Similar to many previous studies, we use two indicators of internationalization through exports: export intensity and an export dummy. A foreign subsidiary may be wholly owned; in which case the parent SME exerts full control over this entity. A foreign subsidiary can also take the form of a joint venture in which the capital is shared with one or more foreign partners (Slangen and Tulder, 2009). Previous studies considered the foreign subsidiary to be the most complete way to enter a foreign market (Pan and Tse, 2000; Lindstrand and Lindbergh, 2011; Bruneel and De Cock, 2016). The subsidiary is a more-advanced mode of internationalization as it allows the SME to establish a permanent presence in the foreign market. This enables it to better integrate into the host country but it also requires more resources to do so. To this end, our study measures internationalization through the subsidiary, using two main indicators: first, it uses a subsidiary dummy for internationalization and then it measures the extent of SME’s internationalization through the subsidiary.

The link between exportation and bank financing

The internationalization of SMEs is often studied only from an export perspective (Jean-Amans and Mahamat, 2014). The work on the link between exports and SME financing can be divided into two groups of studies that show contradictory results. Some studies find a negative relationship between the bank financing of SMEs and these firms’ export intensity (Abor et al., 2014; Benkraiem and Miloudi, 2014; Nagaraj, 2014; Chaney, 2016; Pacheco, 2016; Chandra et al., 2020; Pinto and Silva, 2021). By contrast, other authors argue that exports increase SMEs’ access to bank financing by reducing their financial constraints (such as Greenaway et al., 2007 and Bellone et al., 2010).

The first group of papers highlights the difficulties SMEs face in accessing financing when going international through exports. Exporting SMEs’ are less leveraged than their non-exporting counterparts. This is because these firms depend more on internal than external financing due to the deadweight costs to banks as a result of SMEs’ asymmetric information (Myers and Majluf, 1984). SMEs are characterized by a high level of informational asymmetry because their information systems are less sophisticated in terms of being able to provide all of the information banks require. For example, Abor et al. (2014) argue that export activities make SMEs’ governance more complex, relative to that of larger firms, because exporting increases these firms’ risk levels. Dell’Ariccia and Marquez (2004) show that SMEs have difficulty obtaining debt as banks consider SMEs to be riskier than large firms and thus apply high risk premiums that increase the cost of SMEs’ credit. Since the agency costs associated with internationalization are high, debt financing raises these types of costs for international SMEs because of their informational opacity (Doukas and Pantzalis, 2003).

Even if SMEs are able to obtain debt financing, as Park et al. (2013) argue, this debt is detrimental to international business investment. Moreover, financial theories suggest that high-risk firms prefer equity financing in order to not inhibit growth. Nagaraj (2014) and Chaney (2016) argue that exporting generates fixed costs that make it difficult to access financing and that only SMEs with sufficient internal financial resources are able to export. Egger and Kesina (2013) concur with this view and find a negative relationship between exporting and access to debt for Chinese firms. Using a sample of Taiwanese companies, Chen and Yu (2011) show that a firm’s greater export intensity induces a lower debt-to-equity ratio. Similarly, Benkraiem and Miloudi (2014) conclude that exporting negatively affects French SMEs’ access to bank credit. The same results are found for Portuguese SMEs (Pacheco, 2016; Pinto and Silva, 2021).

Exporting presents several risks that lead to lower debt levels. Indeed, export activity increases a firm’s operational complexity and this complicates local banks’ control of these firms’ selling activities which, in turn, leads these banks to anticipate an increasing risk associated with asset substitution (Myers, 1977). Similarly, subsidiaries of multinational firms operate in economic and institutional environments that differ from those of their parent firms’ home countries (Chen and Yu, 2011). According to Burgman (1996), this complexity increases the agency costs of debt. The higher costs of monitoring these firms means banks have less incentive to finance them and exporters find it difficult to access debt abroad (Pinto and Silva, 2021). We thus expect that a higher degree of exporting would lead to a lower bank-debt ratio. Hence, our first two hypotheses are as follows:

-

H1a. Exporting negatively affects SMEs’ bank-debt ratios.

-

H1b. The export intensity of SMEs is negatively associated with their bank-debt ratios.

The second research group argues that internationalization via exports reduces firms’ financial constraints and facilitates their access to bank financing (Abor et al., 2014; Bellone et al., 2010; Greenaway et al., 2007). Abor et al. (2014) argue that bank financing enables SMEs to cover the fixed costs that are associated with exporting and to meet the requirements of the higher quality standards that exist in foreign markets. Using a panel of manufacturing firms, Greenaway et al. (2007) argue that internationalization through exports improves the financial health of English firms. These authors show that, during their first export operations, exporting firms display the same financial health as non-exporting firms. However, by comparing firms that export for the first time with so-called permanent exporters, it appears the latter have a significant advantage in terms of financial health. Similarly, Manole and Spatareanu (2010) find that Czech exporting firms have fewer financial constraints than Czech non-exporting firms. Moreover, studies show that exporting firms can more easily obtain certain sources of financing (Tornell et al., 2003; Bellone et al., 2010). For example, in the context of information asymmetries, domestic investors view exporting as a sign of firm efficiency (Ganesh-Kumar et al., 2001). Moreover, export revenues enhance the diversification of firms’ earnings, making them less vulnerable to changes in demand (Tornell et al., 2003). Finally, exports help diversify sources of external financing as firms can access the capital markets of the destination countries (Bellone et al., 2010). Hence, our second hypotheses are as follows:

-

H2a. Exporting positively affects SMEs’ bank.

-

H2b. The export intensity of SMEs is positively associated with their bank-debt ratios.

The subsidiaries abroad and bank financing

Large companies and SMEs establish themselves abroad through the subsidiary to exploit and develop specific advantages in foreign markets. Dunning and Lundan (1993) point out that there are three motivations for companies to establish a subsidiary abroad: expanding their market share; finding resources at lower cost; and seeking out strategic investments. Several studies argue that large firms and SMEs are driven by the same motivations and that they encounter similar barriers when they undertake foreign direct investment (Dunning and Lundan, 1993). However, SMEs face more-intense financial constraints than large firms do. In addition, these firms must bear sunken costs when making foreign direct investments. These costs include the costs of analyzing foreign markets, accessing legal advice, and translating and adapting company documents (Bartoli et al., 2014). They also involve expenses related to adapting their products to the host markets, travel expenses, and the costs of setting up a foreign sales network (De Maeseneire and Claeys, 2012).

De Maeseneire and Claeys (2012) show that 78.3% of SMEs use external financing to meet the financing needs that are associated with internationalization via the subsidiary and that these firms also have a clear preference for bank financing. The authors note that 39.1% of SMEs that are established abroad obtain local bank financing in the host country, while 65.2% obtain this financing in their country of origin.

Bridges and Guariglia (2008) analyzed the link between the internationalization of companies via acquisition, the subsidiary being one such mode, and their financial health, in particular. They argue that lower levels of liquidity or higher levels of debt reduce the probability of survival for purely domestic firms but not for internationalized ones. They then conclude that companies’ internationalization helps alleviate their financial constraints. Internationalization through a subsidiary can protect firms from liquidity constraints by offering the possibility of accessing the financial markets of both the home and the host countries. This allows international firms to diversify their sources of financing and the associated risks (Desai et al., 2004). The authors explain that foreign-controlled subsidiaries can access credit via their parent companies and, thus, protect themselves from liquidity constraints. These subsidiaries are generally less risky and quickly adapt to international standards of product quality. As a result, they have easier access to host-country banks (Harrison and McMillan, 2003). Following up on this, and in line with previous studies (Chen and Yu, 2011), we hypothesize that the internationalization of the SME and its level of international activity can be associated with a higher bank-debt ratio. Hence, our last two hypotheses are as follows:

-

H3a. Internationalization through the subsidiary positively affects SMEs’ bank.

-

H3b. The extent of internationalization through the subsidiary is positively associated with SMEs’ bank-debt ratios.

Data and methodology

Data of the study

We obtained our data from the DIANE database developed by Bureau van Dijk. We selected SMEs that meet the European Commission’s definition of firms of this size. Thus, the companies in our sample have a total workforce of no more than 250 employees and an annual turnover of no more than €50 million or a balance sheet total of no more than €43 million. We also excluded financial institutions and banks from our sample. We retained only those SMEs that meet one of the two conditions for internationalization: SMEs with a non-zero percentage of their income attributable to exports and/or those having at least one subsidiary abroad in which they hold at least 50.01% of the capital. The final sample, after excluding observations with missing bank debt information, consists of 4,380 French SMEs, with 26,280 firm-year observations, over a period of six years, from 2013 to 2018.

The SMEs in our sample operate mainly in the industrial sector (36.12%), services (33.84%) and trade (28.81%). Only 1.23% of these SMEs are in the construction and civil engineering sectors. Moreover, the majority of the SMEs studied are unlisted (97.49%) and only 13.86% have the legal status of a public limited company. The main legal status held by the SMEs studied is that of a limited liability company or a simplified joint stock company. Our sample is made up of three groups of SMEs: the first comprises SMEs that exclusively export (66.18%), the second comprises SMEs that internationalize exclusively through foreign subsidiaries (8.23%), and the last group comprises SMEs that opted for both forms of internationalization (18.25%). For the rest of the study, we subdivided the sample into two groups of SMEs: those that export (73.4%) and those with foreign subsidiaries (26.5%). A comparison of the two sub-groups reveals certain differences. Indeed, the exporting SMEs span the three economic sectors: industry (38.46%), services (30.85%) and commerce (29.87%); whereas the SMEs that internationalize through subsidiaries abroad operate mainly in the industrial (36.77%) and services sectors (38.11%).

Empirical approach

We used a dynamic panel model in this study. As financing decisions may have dynamic characteristics, static panel models seemed inappropriate to explain this changing aspect of firm behavior. Moreover, static panel data would not be suitable for the unobserved heterogeneity in this study and using it could have risked obtaining biased results. For our study, this was an important issue because some unobservable firm-level characteristics can remain persistent over time and this could have affected the right-hand side variables in our models.

We used a two-step system generalized method of moments (GMM). This estimator enabled us to consider the dynamic nature of the leverage policy and to study the capital structure by lagging the dependent variable, which is used as an instrumental variable. As suggested by Wintoki et al. (2012), there can be an advantage to using lagged dependent variables as instruments because valid external instruments are difficult to construct. Comparing the different estimators used to deal with dynamic endogeneity, Li et al. (2021) support the outperformance of the system GMM estimators compared to the fixed effects estimation. The GMM is a particularly appropriate estimator in this case as it allows us to accommodate the “unobserved heterogeneity” present in the firm-level datasets, the heteroskedasticity, and the autocorrelation of the individual observations (Arellano and Bond, 1991; Arellano and Bover, 1995). We chose to use a system GMM model instead of a difference GMM because the system GMM predictor has a higher predictive ability for a small sample over a brief time period, as in our case (Roodman, 2009).

The GMM estimator has an additional advantage in that it controls for the problem of the joint endogeneity of the independent variables, the reverse causality, and the simultaneity of the right-hand side variables with the error term (Wintoki et al., 2012). A major issue in studying the relationship between debt financing and internationalization is the potential endogeneity of the independent variables. In our study, not only may internationalization influence the bank-debt-to-equity ratio but this ratio might also influence firms’ internationalization modes and their intensities. The use of the dynamic system GMM with the lagged dependent variable as the instrument helps control for the potential reverse causation between the dependent and predictor variables (Pinto and Silva, 2021).

Flannery and Hankins (2013) compared seven alternative methods for estimating dynamic panel models and concluded that Blundell and Bond’s (1998) system GMM estimator is the best option for dealing with endogeneity. So we used their GMM methodology to estimate a two-equation system of the regression in levels and first differences. The general form of our two models in levels is

where the subscripts refer to firm i at year t; Xi is a vector of the firm-specific determinants of bank loans ratios inspired by previous work (Table 1), namely, the SME’s age (AGE), size (SIZE), asset structure (GUARANTEE), liquidity ratio (LIQ), whether it is a listed firm (LISTED), and its profitability (PROFIT) and legal status (STATUS); Yt is the year-fixed effects included to account for the business cycle effects; and It is an industry fixed effect that was included to control for any common fixed effects across industries (industry, services, trade, construction, civil engineering).

When estimating equations (1) and (2), in the models, we used one-year lagged bank loan ratios as an instrument for the equations in differences. The variable INTER in equation (1) is our first explanatory variable, which measures internationalization using two proxies; namely, EXPORT and SUBSIDIARY. The variable EXT_INTER in equation (2) is our second explanatory variable, which measures the intensity of the internationalization using two factors; namely, the extent of the internationalization through the subsidiary (EXTSUB) and the extent of the exporting (TOEXPT).

To estimate our equations, we used the xtabond2 command in STATA, introduced by Roodman (2009). Following Windmeijer (2005), we also implemented a finite-sample correction in a two-step covariance matrix. Without this correction, the reported standard errors of the two-step estimator tend to be downward biased (Blundell and Bond, 1998). This correction can make two-step robust estimations more efficient than one-step estimations, especially for system GMMs. This procedure allowed us to derive consistent estimators using IV estimation with appropriate lags for the regressors and the lagged dependent variables as the instruments. An important aspect of the methodology is that it relies on a set of internal instruments that are contained within the panel itself: past bank debt ratios can be used as instruments for current bank loan ratios. This eliminated the need for external instruments. The internal instruments were collapsed to avoid their proliferation (Roodman, 2009).

As Arellano and Bond (1991) suggested, the consistency of the GMM estimator is based on two main hypotheses: the instruments are valid and the error terms are not serially correlated. To test the first hypothesis, we used the J-statistics of Hansen (1982), which tests for over-identifying restrictions in the instruments. It also tests the validity of the instruments by checking whether the orthogonality conditions are satisfied. The results of these tests indicated that the instruments used are appropriate and satisfy the orthogonality conditions (Table 4). For the second hypothesis, we used the Arellano and Bond (1991) to test for autocorrelation to examine the presence of serial correlation in the error term. The AR (2) test statistic for the differenced error terms shows no second-order serial correlation (Table 4).

Variables

Dependent variables

Following previous studies, we measured bank financing using the ratio between the firm’s total bank debt and its total assets (Benkraiem and Miloudi, 2014).

Independent variables

Export intensity. To measure the extent of the internationalization of French firms, we followed previous studies that adopted export sales as a percentage of total sales (Pinto and Silva, 2021; Bridges and Guariglia, 2008; Chen and Yu, 2011; Benkraiem and Miloudi, 2014; Nagaraj, 2014; Chaney, 2016; St-Pierre et al., 2018).

Export dummy. A second measure that we used for internationalization was a binary that took the value 1 for SMEs that are exporters and 0 otherwise (Benkraiem and Miloudi, 2014).

These two measures are complementary: The first indicates the company’s level of international activity and the second shows the existence of exporting activities. These two variables also measure French SMEs’ internationalization; that is, these SMEs’ growing involvement in international markets without their necessarily being physically established in these markets.

Internationalization by subsidiary dummy. Prior studies that examined firms’ internationalization used foreign sales as well as foreign income or foreign assets to distinguish between multinational (MNCs) and domestic corporations (DCs). We wanted a better measure of the extent of these firms’ internationalization, but we did not have access to information on these firms’ turnovers by branch or country. French SMEs are not obliged to communicate this information, but we obtained data on their export sales and their number of branches located abroad and within their host countries. Internationalization involves the company expanding beyond its domestic market and into foreign countries. Therefore, we followed prior studies (Chen and Yu, 2011) to define the internationalization of these SMEs and we chose a binary variable that took the value 1 for SMEs with at least one foreign subsidiary and 0 otherwise.

Extent of internationalization. To measure the extent of the internationalization, we followed Lu and Beamish (2004) and Chen and Yu (2011), who adopted Sullivan’s (1994) recommendation to use two measures of a firm’s international activities. The first is the firm’s number of overseas subsidiaries each year. The second is the number of countries in which a firm had overseas subsidiaries in a given year. Next, to change from firms’ counts to their ratios, we divided the first count measure by the maximum number of overseas subsidiaries in our sample and the second one by the maximum number of countries in which a firm had overseas subsidiaries in the study years. Then, we computed the average of the two ratio measures so that our final measure of internationalization took values that ranged from 0 to 1.

Control variables

Following similar studies, we used a number of relevant control variables in our investigation: firm age, size, liquidity, tangible assets, profitability, legal status and whether the SME is a quoted firm (Rajan and Zingales, 1995; Frank and Goyal, 2009; Chehade and Vigneron, 2009; Bonfim and Antão, 2012). Table 1 summarizes the operationalization of these variables.

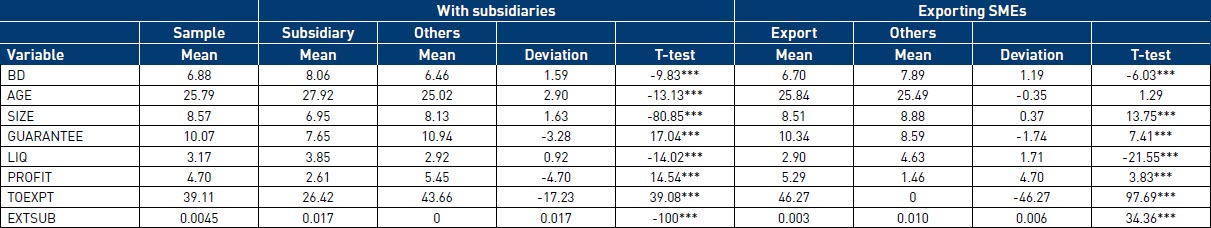

Table 1

Measures and descriptive statistics

Empirical Results and Discussion

In this section, we first analyze the descriptive statistics of our data. Then, we present and discuss the results, beginning with the variables we use to measure internationalization; namely exporting and foreign subsidiaries. As mentioned above, these two modes of internationalization are different from an organizational point of view and in terms of the financial resources required to operationalize them. Our study concludes that export activities have a different impact on the bank debt of French SMEs compared to that of internationalization through subsidiaries. Finally, we present the results for the control variables that are significantly related to bank debt.

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the study variables. It shows that, on average, the French SMEs in our sample have a bank indebtedness rate of around 6.88% of their total assets. Concerning the independent variables, the export turnover (TOEXPT) is, on average, 39.11% of total sales. The EXPORT variable shows an average of 84% of total sales being from exports. The descriptive statistics show that the average size of these SMEs, measured using the Napierian logarithm for the total assets, is more than 8.57%. These statistics also indicate that small- and medium-sized enterprises have an average rate of return of almost 4.70% (PROFIT) and a general liquidity ratio of 3.17%, on average. The SUBSIDIARY and EXTSUB variables measure French SMEs’ internationalization in terms of the extent of their physical establishment abroad. Our statistical results show that, on average, 26.48% of these SMEs own at least one foreign subsidiary.

The above statistical results allowed us to characterize and compare the two groups of SMEs in the sample on the basis of the research variables. To refine this comparison, we used a t-test to compare the means of the two groups on each of the research variables. The results of this test, presented in Table 2 below, show that the exporting SMEs have different levels of bank indebtedness compared to the SMEs with foreign affiliates. We also find that the averages of the other variables are significantly different. The exporting firms in our sample have higher averages for the variables SIZE, GUARANTEE and PROFIT, while the firms with at least one foreign subsidiary have higher averages for the variables AGE and LIQ.

Table 2

Comparison test of exporting SMEs versus SMEs with subsidiaries

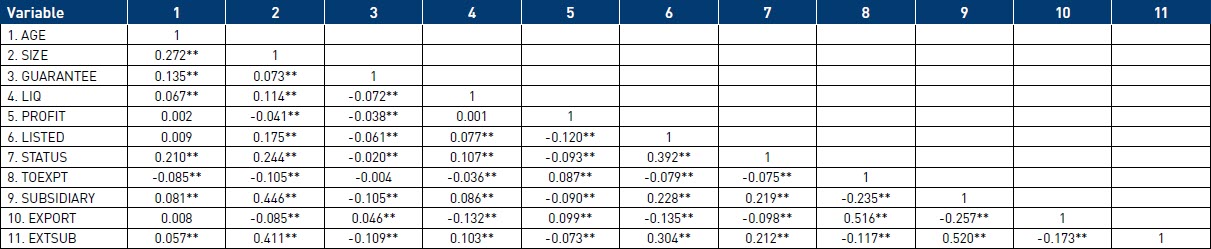

Table 3 shows the correlation coefficients among the variables used in our study. It can be seen that the correlation coefficient between the independent variables is not high. Therefore, we can use all independent variables in the same model without multicollinearity problems because the coefficients of all explanatory variables are very low.

Results and discussion

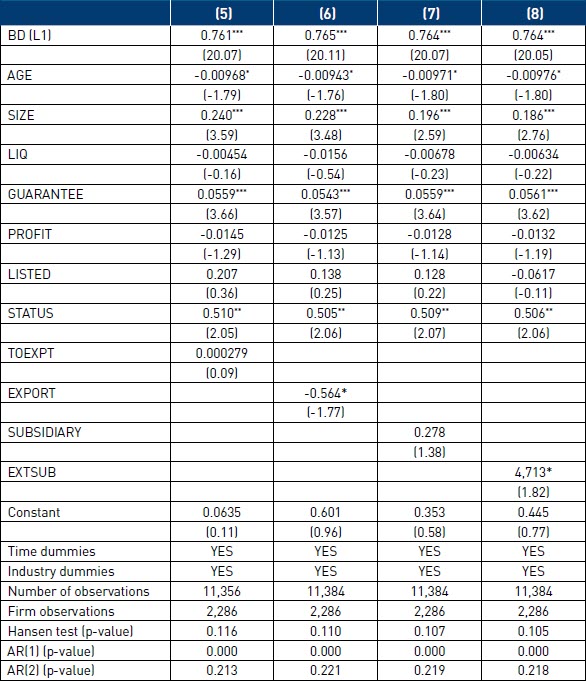

Our research reveals several interesting results; these are presented on Table 4. The first result is the negative relationship between internationalization through exports as measured by export status (EXPORT), export intensity (TOEXPT), and the bank-debt ratio. Thus, we find that the variables TOEXPT and EXPORT negatively and significantly affect SMEs’ bank leverage ratios, where (t = -3.30, p < 0.01) and (t = -2.54, p < 0.01), respectively. These results support our hypotheses 1a and 1b and are in line with those of the previous research that underlines the negative impact of exporting and export intensity on SMEs’ bank debt ratios (Benkraiem and Miloudi, 2014; Pinto and Silva, 2021). These results are also consistent with the literature that focuses on the link between export activity and the existence of financial constraints (Bellone et al, 2010; Abor et al., 2014; Nagaraj, 2014; Chaney, 2016).

The majority of previous studies that focused on the relationship between the capital structure and the internationalization strategies of multinational firms shows that these firms’ debt ratios are lower than those of domestic firms (Burgman, 1996; Chen and Yu, 2011). By studying mainly unlisted SMEs, our research complements previous works that focused mainly on large listed companies. Our results are also in line with the findings of Benkraiem and Miloudi (2014), whose study investigated a sample of French-listed SMEs. Although the results of our study converge with theirs, we did not adopt the same methodology. Rather, we focused on unlisted French SMEs, studied two modes of internationalization and chose a different model, a dynamic system GMM, allowing us to consider the endogeneity of our internationalization variables.

Table 3

Correlation Matrix

We find the same negative impact of export intensity on French SME’s debt ratios as that found by Pinto and Silva (2021) on a sample of unlisted Portuguese SMEs. However, unlike our research, their definition of the debt ratio is not limited to bank loans, they also studied SMEs’ total liabilities (long—and short-term liabilities, as well as leasing and trade credit).

The causes of this negative relationship between these SMEs’ debt ratios and their export activities and intensities are numerous. For example, these firms’ high fixed costs discouraged banks from financing them (Nagaraj, 2014; Chaney, 2016). When SMEs enter international markets through exporting activities, local banks find that they are unable to monitor these firms’ sales activities because of the complexity of these types of operations. International SMEs are more informationally opaque, due to their operational complexity, and this increases the agency costs of debt. SMEs’ asymmetric information is not readily available to banks. The problem of asymmetric information seems to be increasing, particularly among exporting SMEs, to the point where banks may restrict these firms’ access to credit (Dell’Ariccia and Marquez, 2004; Chaney, 2016). Along the same vein, Laveren and Bortier (2003) pointed out that some of the difficulties encountered by Belgian SMEs in their bank financing resulted from a lack of collateral.

SMEs with a higher degree of export intensity rely more on internal financing than on debt financing. This means exporting SMEs are less leveraged and this can be explained by the increase in these firms’ informational opacity and monitoring costs. These findings are consistent with previous work on the impact of export intensity on corporate leverage and are in line with the pecking-order theory (Pinto and Silva, 2021). According to this theory, exporting SMEs have less recourse to debt because, first and foremost, they use internal financing, notably due to the indirect costs of information asymmetry associated with external financing.

In addition, our results corroborate the argument that highlights the problem of debt financing for companies that choose to internationalize using exporting as a mode of entry into foreign markets. The agency costs of debt are more severe for international firms because they operate in different institutional and economic environments (Chen and Yu, 2011). In this context, creditors find it more difficult to monitor firms’ sales activities in international markets and they anticipate that the risk of asset substitution will be higher in these cases (Myers, 1977). Here, banks are less motivated to finance exporters and exporters face difficulties in accessing bank loans because of the high costs of monitoring. Following trade-off theory, we find that a higher degree of export intensity is associated with a lower debt ratio.

However, our results do not support hypotheses 2a and 2b. These hypotheses are motivated by studies in the literature that specify that export activities reduce SMEs’ financial constraints (Greenaway et al., 2007; Bridges and Guariglia, 2008; Manole and Spatareanu, 2010). Greenaway et al. (2007) found that British exporting firms have comparative advantages in terms of access to financial resources, over non-exporting firms. Along the same vein, Bridges and Guariglia (2008) pointed out that the internationalization of unquoted firms reduces the cost of financial constraints. Companies that export seem to have greater access to financing. According to these studies, these results can be explained by the fact that exporting reduces the information asymmetry between capital providers and borrowers insofar as exporting is perceived as a guarantee of these companies’ efficiency. In addition, opening up to international markets allows exporting companies to diversify their turnover, which tends to reduce their vulnerability. For example, Bridges and Guariglia (2008) and Greenaway et al. (2007) focused exclusively on firms’ short-term-debt-to-total-assets ratios (bank overdrafts, leasing, and other short-term loans), while Manole and Spatareanu (2010) focused only on long-term debt.

The definition of a debt ratio explains the divergence of our results from those found by this branch of the literature. While our study focuses on total bank debt to total net assets, Bridges and Guariglia (2008) and Greenaway et al. (2007) focused exclusively on firms’ short-term-debt-to-total-assets ratios (bank overdrafts, leasing, and other short-term loans), while Ganesh-Kumar et al. (2001) and Manole and Spatareanu (2010) focused only on long-term debt.

The second finding of our study is the positive and significant relationship between internationalization through subsidiaries as measured by the variables subsidiaries abroad (SUBSIDIARY), SMEs’ extent of foreign subsidiaries (EXTSUB) and bank-debt-to-assets ratios. As expected, the variable SUBSIDIARY is significant and positively related to firms’ bank debt ratios (t = 4.03, p < 0.01). This result is consistent with prior studies (Chen and Yu, 2011; Akhtar and Oliver, 2009; Singh and Nejadmalayeri, 2004) and offers support for hypothesis 3a. The variable EXTSUB also shows a significantly positive relationship with firms’ debt ratios (t = 1.88, p < 0.1). This result supports hypothesis 3b and is in line with the results of several previous studies (Chen and Yu, 2011). These results suggest that French SMEs that established abroad through subsidiaries benefitted from both financing through the host countries’ banks and from French banks that had established in the same foreign countries (Harrison and McMillan, 2003). These SMEs’ relationships with their home country’s banks existed long before these firms had set up abroad (Lindstrand and Lindbergh, 2011).

The so-called “follow-the-customer” hypothesis (Williams, 1997) explains the decision of French banks to establish a physical presence in French SMEs’ host countries to continue supporting these firms’ activities. In addition, in France, Bpifrance, a public investment bank whose responsibilities include supporting SMEs, provides these firms with guarantees and financing when they create or acquire foreign subsidiaries. To this end, French banks and the banks of French SMEs’ host countries can facilitate SMEs that express the need for this type of financing when they are investing in foreign subsidiaries, and if the host country’s bank finances this relationship, then it generally requests a guarantee from the SME’s French bank. Our analysis of the variance also shows a higher average firm age and liquidity ratio for French SMEs that locate abroad through a subsidiary. This could explain, among other things, the positive link between this form of internationalization and these SMEs’ bank debt ratios, especially for older SMEs that have acquired experience abroad. Establishment abroad is a tangible asset with more guarantees for banks than the SMEs’ export activities provide.

Increasing their amount of debt in foreign currencies may reduce the investment risk of an SME that is established in a foreign country. Banks in host countries can control the activities of SMEs more easily than banks in the home country because home monitoring reduces monitoring costs. Consequently, international SMEs may choose to raise more debt in a foreign currency to reduce the different risks associated with their investments, the exchange rate, and political and social risks (Kedia and Mozumdar, 2003). Our findings also reflect that international SMEs could be interested in taking advantage of tax shields that are associated with the increased use of debt due to host countries’ more-advantageous tax regimes (Chen and Yu, 2011). Paying interest on debt is an effective way to minimize local tax payments and to withhold taxes upon repatriation.

Table 4

Regression system GMM model results

Notes: The estimates are obtained using Blundell and Bond’s (1998) two-step system GMM. ***, **, * are statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively; the t statistics (in parentheses) are based on White’s heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors; p-values are reported for the AR (1), AR (2) and Hansen statistics.

Table 4 also shows the empirical results of our control variables. The results of Model 1 show a positive and significant relationship (t = 3.97 p < 0.01) between the bank debt ratios and the size of French SMEs, corroborating the results of Degryse et al. (2012), Benkraiem and Miloudi (2014), and Abor et al. (2014). Large SMEs are often more diversified, have more collateral available (Maes et al., 2019) and, thus, lower levels of bankruptcy risk. In this sense, firm size favors their access to debt. A high total asset size is a proxy for the physical collateral that is available to creditors (Benkraiem and Miloudi, 2014). Furthermore, we find that bank debt and guarantees, as measured by the proportion of tangible fixed assets in total assets (GUARANTEE), are positively correlated (t = 5.65 p < 0.01), confirming the results of previous studies (Steijvers and Voordeckers, 2009; Singh and Nejadmalayeri, 2004). The use of personal and corporate guarantees enables banks to secure their transactions with SMEs and, in the event of default, to obtain repayment of their claims. As a result, a large number of business assets, a significant portion of which are tangible assets, can provide potential creditors with an attractive guarantee of repayment. Indeed, financial institutions consider SMEs to be risky because of the lack of complete information on their repayment capacities and guarantees (De Maeseneire and Claeys, 2012). Because of the asymmetry of information, banks often ask SMEs for guarantees to reduce their financial losses in case of bankruptcy.

Additionally, as in several previous studies, our results show that profitability (PROFIT) has a significantly negative impact (t = -1.74 p < 0.1) on bank financing (Fauzi et al., 2013; Palacín-Sánchez et al., 2013; Lisboa, 2017; Maes et al., 2019). Profitable firms that are associated with the deductibility of financial interest are generally less likely to fail and more likely to benefit from the tax savings, unlike less-profitable firms (Rajan and Zingales, 1995). Furthermore, a high profitability ratio indicates that firms can generate more internal resources to finance their operations rather than seeking external debt financing. In contrast, our results contradict the predictions of the free cash flow and trade-off theories. The former theory states that debt and profitability are positively related; the second predicts that profitable firms have higher borrowing capacity. High leverage forces firms to use profits to pay their debts (interest and principal) and, thus, prevents them from investing in projects (Maes et al., 2019).

Our study also shows that firms’ legal status (STATUS) favors (t = 3.55 p < 0.01) French SMEs’ access to bank financing. Indeed, companies with “Société anonyme” status (public limited company) must publish their accounts and certified financial statements. This practice increases their transparency and reduces the informational opacity that characterizes SMEs (Chehade and Vigneron, 2009).

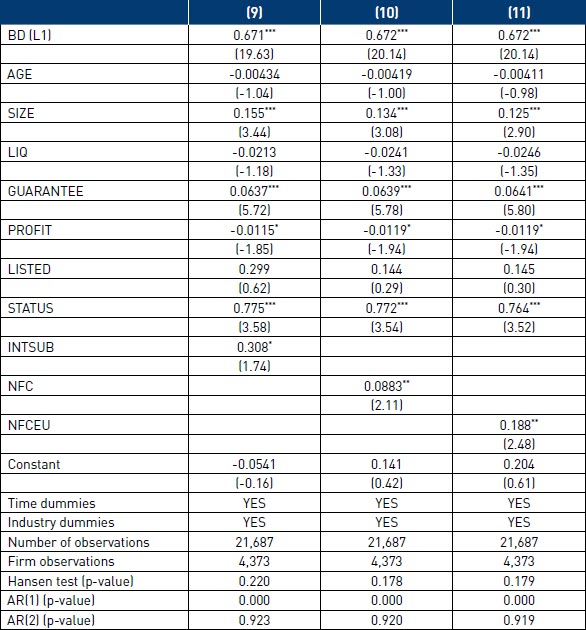

Further robustness checks

We performed several additional tests for robustness. First, our descriptive statistics show that in 30% of the observations in our sample the bank-debt-to-assets ratios are zero. Given that we are interested in the impact of the internationalization mode on the bank debt ratio, it was necessary to control for the potential impact of this level of debt on our results. Several previous studies left out their extreme leverage observations. Hovakimian and Li (2011) and Pinto and Silva (2021) left out the extreme leverage observations that were greater than 90% and less than 10% to avoid spurious results. Park et al. (2013) left out the firm years in which firms issued neither debt nor equity. Referring to these studies, we did not include observations with bank-debt-to-total-assets ratios that were equal to zero when we tested using our two models (Table 5). Again, the results show that exports (EXPORT) have a negative impact on SMEs’ bank debt ratios (BD), while internationalization through the establishment of foreign subsidiaries (SUBSIDIARY) has a positive but not more-significant impact. The results show the extent to which internationalization through subsidiaries (EXTSUB) has positive and significant effects on debt ratios (DB); but they also show that the impact of export intensity is not more significant.

Table 5

Robustness results using a sample excluding observations with a zero-debt ratio

Notes: The estimates are obtained using Blundell and Bond’s (1998) two-step system GMM. ***, **, * are statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively; the t statistics (in parentheses) are based on White’s heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors; the p-values reported for the AR (1), AR (2) and Hansen statistics.

Second, we followed previous research (Chen and Yu, 2011; Lu and Beamish 2004) to define the extent of internationalization through subsidiaries as a composite measure that includes the number of host countries and foreign subsidiaries. The internationalization metrics were divided into two broad types: scale metrics, including foreign to total sales; and scope metrics, including counts based on the number of foreign countries and foreign subsidiaries. To ensure that our measures did not drive our results, in equation 2, we also tested additional scope metrics that are the most widely used in the multinational literature (Rugman and Oh, 2011). These include the number of foreign subsidiaries (NFS), host countries (NFC), and the ratio of the number of foreign subsidiaries over the number of subsidiaries (INTSUB).

The results in Table 6 show that the ratio of the number of foreign subsidiaries over the number of subsidiaries (INTSUB) has a positive and significant impact on the bank debt ratio, which supports our first findings. Our results also report a positive impact of the proxy of the number of foreign countries (NFC), although this is not significant for the number of foreign subsidiaries (NFS). This supports the idea that geographic diversification allows better access to bank debt for SMEs that benefit from debt in a different foreign currency in addition to the tax savings associated with the deductibility of the interest on this debt.

Third, in our robustness tests, we considered additional proxies to measure SMEs’ intra-region internationalization through foreign subsidiaries. Indeed, numerous recent studies set limits on the scope measures. According to Rugman and Oh (2011), scope metrics do not effectively measure a firm’s foreign engagement. These authors noted that several studies recognize that multinational firms operate not globally but regionally. Rugman and Oh (2007) emphasized the importance of studying firms’ intra-region internationalization. Therefore, to examine the impact of intra-region internationalization on firms’ bank debt ratios, we introduced variables that represent the number of countries where SMEs had established a subsidiary both within Europe (NFCEU), which is intra-region for French SMEs, and outside Europe (NFCOUTEU). We also introduced the number of subsidiaries both inside Europe (NFSEU) and outside Europe (NFSOUTEU).

Our results, reported in Table 6, show that only the variable NFCEU has a positive and significant impact on SMEs’ bank debt ratios. These results suggest that these firms’ establishment in Europe, mainly the number of countries within which they became established via subsidiaries, helped reduce the risk associated with their internationalization (Desai et al., 2004). The geographical proximity of foreign locations, especially within Europe, has a positive effect on the indebtedness of French SMEs, since it reassures banks about these firms’ risk levels and also reflects a lower level of uncertainty. These results are in line with those of Pacheco (2016), who tested the “upstream-downstream” hypothesis in relation to exporting firms’ risk levels. According to this hypothesis, firms that export to riskier markets (“downstream”), meaning markets outside the European Union, have lower debt capacity. According to Pacheco (2016), firms that are more dependent and focused on markets outside the European Union face higher agency costs and will tend to present lower levels of leverage.

Our results corroborate the upstream hypothesis. When firms internationalize to safer markets, the European market in our case, their debt ratios increase due to risk diversification. The more internationalizing companies orient toward close geographical areas or comparable institutional environments, such as the European market, the lower are the levels of the agency costs associated with these SMEs. French banks have a better knowledge of the European environment and are themselves established on the continent. Thus, our results corroborate the work of De Maeseneire and Claeys (2012), who stated that access to domestic and foreign financial markets enables SMEs to diversify their sources of financing and reduce their associated risks. These results are in line with those found by Pacheco (2016) on a sample of Portuguese firms.

Table 6

Empirical results for robustness across various measures of internationalization through foreign subsidiaries

Notes: The estimates are obtained using Blundell and Bond’s (1998) two-step system GMM. ***, **, * are statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively; the t statistics (in parentheses) are based on White’s heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors; the p-values reported for the AR (1), AR (2) and Hansen statistics.

Conclusions and Implications

Our research examines the relationship between bank financing and the internationalization of French SMEs through both exports and foreign subsidiaries. In particular, we examine the relationship between bank financing and the ability of SMEs to export, as well as the relationship between the internationalization of SMEs through their subsidiaries and their access to bank financing. Our data covers 4,380 French SMEs, for the 2013 to 2018 period, that have export intensities other than zero and/or that own at least one foreign subsidiary. We apply an econometric model that is based on the system of the generalized method of moments to rectify the potential for endogeneity biases in regression models that are based on panel data.

A number of our results are noteworthy. In particular, we find that French SMEs that are established abroad through subsidiaries benefit from the “follow-the-customer” hypothesis of French banks that are established in the same foreign countries as these SMEs’ subsidiaries. This means that French banks physically establish themselves in the same countries as these SMEs in order to continue to support their business activities. The study also shows that the geographical dimension of internationalization favors bank financing. Finally, our results underline that the higher the export intensity, the more difficult it is for French SMEs to access bank financing. These difficulties may be associated with the informational asymmetry that results from insufficient guarantees for exporting SMEs to the extent that banks may restrict credit.

Our study provides some valuable insights for researchers and policy makers. First, by considering the foreign subsidiary as a mode of internationalization, this study contributes to the advancement of knowledge on the link between internationalization and SMEs’ access to bank financing. The research variables complement the study’s reference to the intensity of French SMEs’ internationalization, such as the number of total host countries and the number of host countries in Europe as measures of the geographical scope of these SMEs’ internationalization. Second, SMEs are key players in economic growth and innovation. Thus, our findings could inspire policymakers to develop initiatives concerning financing programs for these enterprises. More specifically, this study sheds new light on the financing that may be needed not only by exporting SMEs but also by those developing activities abroad through subsidiaries. Furthermore, our results will be of interest to policymakers and financial institutions and, thus, contribute to the public debate on the financing of SMEs seeking to expand abroad. Finally, our results will be useful for SMEs themselves and for organizations dedicated to the advocacy of small- and medium-sized enterprises. These organizations will be able to use our main findings to raise awareness of the importance of and challenges to internationalization for SMEs, entities that are key components of the French economy.

Our paper also opens up interesting avenues for future research. First, we analyze the impact of a mode of internationalization on the total bank debt ratio of French SMEs, which is still the main source of external finance for these kinds of firms. Unlike domestic corporations, large listed multinational firms, especially exporters, are more likely to depend on short-term debt financing (Maes et al., 2019). Thus, in future studies, investigators could analyze the impact of different modes of SMEs’ internationalization on different debt maturities.

Second, we were constrained by the availability of data and, thus, we did not test the impact of the destination country for SMEs’ exports on these firms’ bank debt ratios. However, we did study the impact of SMEs’ intra-region internationalization through foreign subsidiaries. We found that the number of countries where SMEs establish at least one subsidiary in Europe has a positive and significant impact on their bank debt ratios. Future research could incorporate variables that measure the characteristics of destination countries. Indeed, the bank debt ratios of international SMEs could be affected by the level of development of a financial system, the level of taxation, the geographical and cultural proximity, or the destination country’s level of risk.

Third, Goodell (2020) highlights the effect of macroeconomic shocks on firms’ capital structures. With the collapse of sales and the liquidity problems caused by the COVID-19 crisis, SMEs have seen their access to finance profoundly disrupted (OECD, 2020). In addition, governments have adopted various measures to specifically help SMEs cope with the consequences of COVID-19. Thus, taking into account the new post-pandemic situation, future research could examine the relationship between internationalization (exports, direct establishment abroad) and access to bank and non-bank financing for SMEs, during and after Covid-19, through a comparison of developed and emerging countries. Along the same line, we believe it would be useful to deepen and extend this research to an international study that examines the link between internationalization (exports, direct establishments abroad) and the capital structure of SMEs, during and after the Covid-19 pandemic, taking into account the risk of default.

Appendices

Biographical notes

Ghassen Bouslama is Associate Professor of Finance at NEOMA Business School. He holds a PhD in Management Sciences from the University of Reims Champagne-Ardenne. His main research interests are bank-SMEs’ relationship, the financing of high-growth SMEs and the capital structure of SMEs.

Hamadou Boubacar is a full professor of finance in the Faculty of Administration at the University of Moncton. Holder of a doctorate in Management Sciences from the University of Reims Champagne-Ardenne (URCA) in 2007, he taught for two years at URCA, before doing a four-month postdoctoral fellowship at the GIREF at the ESG of the University of Quebec in Montreal. His doctoral research interests focused on internationalization and banking performance. However, in recent years, he has also been interested in the impact of governance mechanisms on the performance of firms in general and microfinance institutions in particular.

Bibliography

- Abor, Joshua Y.; Agbloyor, Elikplim K.; Kuipo, R. (2014). “Bank finance and export activities of Small and Medium Enterprises”, Review of Development Finance, Vol. 4, N° 2, p. 97-103.

- Akhtar, Shumi; Oliver, Barry (2009). “Determinants of Capital Structure for Japanese Multinational and Domestic Corporations”, International Review of Finance, Vol. 9, N° 1-2, p. 1-26.

- Arellano, Manuel; Bond, Stephen (1991). “Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations”, Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 58, N° 2, p. 277-297.

- Arellano, Manuel; Bover, Olympia (1995). “Another Look at the Instrumental Variable Estimation of Error Component Models”, Journal of Econometrics, Vol. 68, N° 1 p. 29-51.

- Bartoli, Francesca; Ferri, Giovanni; Murro, Pierluigi; Rotondi Zeno (2014). “Bank support and export: evidence from small Italian firms”, Small Business Economics, N° 42, p. 245-264.

- Bellone, Flora; Musso, Patrick.; Nesta, Lionel; Schiavo, Stefano (2010). “Financial Constraints and Firm Export Behaviour”, The World Economy, Vol. 33, N° 3, p. 347-373.

- Benkraiem, Ramzi; Miloudi, Anthony (2014). “L’internationalisation des PME affecte-t-elle l’accès au financement bancaire?”, Management International, Vol. 18, N° 2, p. 70-79.

- Blundell, Richard; Bond, Stephen (1998). “Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models”, Journal of Econometrics, Vol. 87 N° 1, p. 115-143.

- Bonfim, Diana; Antão, Paula (2012). “The dynamics of capital structure decisions”, Banco de Portugal, Economics and Research Department.

- Bpifrance. (2018, 6 juillet). Communiqué du 6 juillet à propos du renouvellement et du renforcement du partenariat entre Bpifrance et de Business France pour accompagner les entreprises à l’export. Direction générale de la Caisse des dépôts. https://presse.bpifrance.fr/bpifrance-et-business-france-renouvellent-leur-partenariat-et-renforcent-leurs-actions-communes-pour-accompagner-les-entreprises-a-lexport/

- Bourcieu, Stephan (2012). “Les sept points faibles des PME françaises à l’export”, L’Expansion Management Review”, Vol. 2, N° 145, p. 84-91.

- Bridges, Sarah; Guariglia, Alessandra (2008). “Financial constraints, global engagement, and firm survival in the United Kingdom: Evidence from micro data”, Scottish Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 55, N° 4, p. 444-464.

- Bruneel, Johan; De Cock, Robin (2016). “Entry Mode Research and SMEs: A Review and Future Research Agenda”, Journal of Small Business Management, Vol. 54, N° S1, p. 135-167.

- Burgman, Todd A (1996). “An empirical examination of multinational corporate capital structure”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 27, N° 3, p. 553-570.

- Chandra, Ashna A; Paul, Justin; Chavan, Meena (2020). “Internationalization challenges for SMEs: evidence and theoretical extension”, European Business Review, Vol. 33, N° 2, p. 316-344.

- Chaney, Thomas (2016). “Liquidity constrained exporters”, Journal of Economic Dynamics Control, Vol. 72, p. 141-154.

- Chehade, Hiba; Vigneron, Ludovic (2009). “SMEs Choice of Main Bank and Organizational Structure: The Role of Soft Information and Credit Rationing”, Bankers, Markets & Investors, N° 102, p. 33-45.

- Chen, Chiung-J; Yu, Chwo-Ming J (2011). “FDI, export, and capital structure: an agency theory perspective”, Management International Review, Vol. 51, N° 3, p. 295-320.

- De Bonis, Riccardo; Ferri, Giovanni; Rotondi, Zeno (2015). “Do firm-bank relationships affect firms’ internationalization?”, International Economics, Vol. 142, p. 60-80.

- De Maeseneire, Wouter; Claeys, Tine (2012). “SMEs, Foreign Direct Investment and Financial Constraints: The Case of Belgium”, International Business Review, Vol. 21, N° 3, p. 408-424.

- Degryse, Hans; De Goeij, Peter; Kappert, Keter (2012). “The impact of firm and industry characteristics on small firms’ capital structure”, Small Economics Business, Vol. 38, N° 4, p. 431-437.

- Dell’Ariccia, Giovanni; Marquez, Robert (2004). “Information and bank credit allocation”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 72, N° 1, p. 185-214.

- Desai, Mihir A; Foley, C. Fritz; Hines, James (2004). “A Multinational Perspective on Capital Structure Choice and Internal Capital Markets”, The Journal of Finance, Vol. 59, N° 6, p. 2451-2487.

- Doukas, John A; Pantzalis, Christos (2003). “Geographical diversification and agency costs of debt of multinational firms”, Journal of Corporate Finance, Vol. 9, N° 1, p. 59-92.

- Dunning, John H; Lundan, Sarianna M (1993). Multinational enterprises and the global economy, Northampton, Massachusetts, in the USA, Edward Elgar Publishing, 920 p.

- Egger, Peter; Kesina, Michaela (2013). “Financial Constraints and Exports: Evidence from Chinese Firms”, CESifo Economic Studies, Vol. 59, N° 4, p. 676-706.

- Fauzi, Fitriya; Basyith, Abdul; Idris, Muhammad (2013). “The determinants of capital structure: An empirical study of New Zealand-listed firms”, Asian Journal of Finance & Accounting, Vol. 5, N° 2, p. 1-21.

- Flannery, Mark J; Hankins, Kristine Watson (2013). “Estimating dynamic panel models in corporate finance”, Journal of Corporate Finance, Vol. 19, p. 1-19.

- Frank, Murray Z.; Goyal, Vidhan K. (2009). “Capital Structure Decisions: Which Factors Are Reliably Important?”, Financial Management, Vol. 38, N° 1, p. 1-37.

- Ganesh-Kumar, A; Sen, Kunal; Vaidya, Rajendra R (2001). “Outward orientation, investment and finance constraints: A study of Indian firms”, Journal of Development Studies, Vol. 37, N° 4, p. 133-149.

- Gkypali, Areti; Love, James H; Roper, S (2021). “Export status and SME productivity: Learning-to-export versus learning-by-exporting”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 128, p. 486-498.

- Goodell, John W. (2020), “COVID-19 and finance: Agendas for future research”, Finance Research Letters, Vol. 35, 101, 512.

- Greenaway, David; Guariglia, Alessandra; Kneller, Richard (2007). “Financial factors and exporting decisions”, Journal of International Economics, Vol. 73, N° 2, p. 377-395.

- Hansen, Lars P. (1982). “Large sample properties of generalized method of moments estimators”, Econometrica, Vol. 50, N° 4, p. 1029-1054.

- Harrison, Ann E; McMillan, Margaret S (2003). “Does direct foreign investment affect domestic credit constraints?”, Journal of International Economics, Vol. 61, N° 1, p. 73-100.

- Hovakimian, Armen; Li, Guangzhong (2011). “In search of conclusive evidence: how to test for adjustment to target capital structure”, Journal of Corporate Finance, Vol. 17, N° 1, p. 33-44.

- Insee (2018). “Les petites et moyennes entreprises réalisent 17% des exportations”; Insee Première, N° 1692.

- Jean-Amans, Carole; Mahamat, Abdellatif, (2014). “Modes d’implantation des PME à l’étranger: le choix entre filiale 100% et coentreprise internationale”, Management International,Vol. 18, n° 2, p. 195-208.

- Kedia, Simi; Mozumdar, Abon (2003). “Foreign currency denominated debt; an empirical examination”, Journal of Business, Vol. 76, N° 4, p. 521-546.

- Laveren, Eddy; Bortier, Johan (2003). “Bank financing and SMEs: survey results and policy implications”. The 48th Conference of the International Council for Small Business, Belfast.

- Li, Jiatao; Ding, Haoyuan; Hu, Yichuan; Wan, Guoguang (2021). “Dealing with dynamic endogeneity in international business research”, Journal of International Business Studies volume, Vol. 52, p. 339-362.

- Lindner, Thomas; Klein, Florian; Schmidt, Stefan (2018). “The effect of internationalization on firm capital structure: A meta-analysis and exploration of institutional contingencies”, International Business Review, Vol. 27, N° 6, p. 1238-1249.

- Lindstrand, Angelika; Lindbergh, Jessica (2011). “SMEs’ dependency on banks during international expansion”, International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 29, N° 1, p. 65-83.

- Lisboa, Ines (2017). “Capital structure of exporter SMEs during the financial crisis: evidence from Portugal”, European Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 22, N° 1, p. 25-49.

- Lu, Jane W.; Beamish, Paul W. (2004). “International diversification and firm performance: the S-curve hypothesis”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 47, N° 4, p. 598-609.

- Maes, Elisabeth, Dewaelheyns, Nico, Fuss, Catherine; Van Hulle, Cynthia (2019). “The impact of exporting on financial debt choices of SMEs”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 102, p. 56-73.

- Manole, Vlad; Spatareanu, Mariana (2010). “Exporting, Capital Investment and Financial Constraints”, Review of World Economics, Vol. 146, N° 1, p. 23-37.

- Myers, Stewart C. (1977). “Determinants of corporate borrowing”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 5, N° 2, p. 147-175.

- Myers, Stewart. C; Majluf, Nicholas S (1984). “Corporate Financing and Investment Decisions When Firms Have Information That Investors Do Not Have”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 13, N° 2, p. 187-221.

- Nagaraj, Priya. (2014). “Financial constraints and export participation in India”, International Economics, N° 140, p. 19-35.

- Ocde (2018). “Le financement des PME et des entrepreneurs 2018: Tableau de bord de l’OCDE”. France.

- Ortiz-Molina, Hernan; Penas, Maria F. (2008). “Lending to small businesses: the role of loan maturity in addressing information problems”, Small Business Economics, Vol. 30, p. 361-383.

- Pacheco, Luis. (2016). “Capital structure and internationalization: The case of Portuguese industrial SMEs”, Research in International Business and Finance, Vol. 38, p. 531-545.

- Palacín-Sánchez, Maria J.; Ramírez-Herrera, Luis; di Pietro, Filippo (2013). “Capital structure of SMEs in Spanish regions”, Small Business Economics, Vol. 41, N° 2, p. 403-51.

- Pan, Yigang; Tse, David. (2000). “The hierarchical model of market entry modes”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 31, N° 4, p. 535-554.

- Park, Soon H.; Suh, Jungwon; Yeung, Bernard (2013). “Do multinational and domestic corporations differ in their leverage policies?”, Journal of Corporate Finance, Vol. 20, p. 115-139.

- Pinto, Joao M.; Silva, Catia S. (2021). “Does export intensity affect corporate leverage? Evidence from Portuguese SMEs”, Finance Research Letters, Vol. 38.

- Rahaman, Mohammad M. (2011). “Access to financing and firm growth”, Journal of Banking & Finance, Vol. 35, N° 3, p. 709-723.

- Rajan, Raghuram G.; Zingales, Luigi (1995). “What Do We Know About Capital Structure? Some Evidence from International Data”, Journal of Finance, Vol. 50, N° 5, p. 1421-1460.

- Roodman, David (2009). “A note on the theme of too many instruments”, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 71, N° 1, p. 135-158.

- Rugman, Alan M.; Oh, Chang H. (2007). “Multinationality and regional performance, 2001-2005”, Research in Global Strategic Management, Vol. 13, p. 31-43.

- Rugman, Alan M.; Oh, Chang H. (2011). “Methodological issues in the measurement of multinationality of US firms”, Multinational Business Review, Vol. 19, N° 3, p. 202-212.

- Singh, Manohar; Nejadmalayeri, Ali (2004). “Internationalization, capital structure, and cost of capital: Evidence from French corporations”, Journal of Multinational Financial Management, Vol. 14, N° 2, p. 153-169.

- Slangen, Arjen; Van Tulder, Rob (2009). “Cultural distance, political risk, or governance quality? Towards a more accurate conceptualization and measurement of external uncertainty in foreign entry mode research”, International Business Review, Vol. 18, p. 276-291.

- Steijvers, Teni.se; Voordeckers, Wim (2009). “Collateral and credit rationing: A review of recent empirical studies as a guide for future research”, Journal of Economic Surveys, Vol. 23, N° 5, p. 924-946.

- Steinhäuser, Vivian P; Paula, Fabio D; De Macedo-Soares, Teresia D (2020). “Internationalization of SMEs: a systematic review of 20 years of research”, Journal of international Entrepreneurship, Vol. 19, p. 164-195.

- St-Pierre Josée; Sakka, Ouafa; Bahri, Moujib (2018). “External Financing, Export Intensity and Inter-Organizational Collaborations: Evidence from Canadian SMEs”, Journal of Small Business Management, Vol. 56, N° 1, p. 6811-8712.

- Sullivan, Daniel (1994). “Measuring the Degree of Internationalization of a Firm”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 25, N° 2, p. 325-342.

- Tornell, Aaron A.; Westermann, Frank; Martinez, Lorenza (2003). “Liberalization, Growth, and Financial Crises: Lessons from Mexico and the Developing World”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Vol. 34, N° 2, p. 1-112.

- Williams, Barry. (1997). “Positive theories of multinational banking: eclectic theory versus internalization theory”, Journal of Economic Surveys, Vol. 11, N° 1, p. 71-100.

- Windmeijer, Frank. (2005). “A finite sample correction for the variance of linear efficient two-step GMM estimators”, Journal of Econometrics, Vol. 126, N° 1, p. 25-51.

- Wintoki, Babajide.; Linck, James S.; Netter, Jeffry M. (2012). “Endogeneity and the dynamics of internal corporate governance”, Journal of Financial Economics, Vol. 105, N° 3, p. 581-606.

Appendices

Notes biographiques

Ghassen Bouslama est Professeur associé en Finance à NEOMA Business School. Il est titulaire d’un Doctorat en sciences de gestion de l’Université de Reims Champagne-Ardenne. Ses recherches portent sur la relation banque-PME, le financement des PME à forte croissance et la structure de capital des PME.

Hamadou Boubacar est professeur titulaire de finance à la faculté d’administration de l’Université de Moncton. Détenteur d’un doctorat en Sciences de Gestion de l’Université de Reims Champagne-Ardenne (URCA) en 2007, il a enseigné pendant deux ans à l’URCA, avant d’effectuer un stage postdoctoral de quatre mois au GIREF à l’ESG de l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Ses intérêts de recherches doctorales portaient sur l’internationalisation et la performance bancaires. Cependant, ces dernières années, il s’intéresse aussi à l’impact des mécanismes de gouvernance sur la performance des entreprises en général et sur celle des institutions de microfinance en particulier.

Appendices

Notas biograficas

Ghassen Bouslama es profesor asociado de finanzas en NEOMA Business School. Es doctor en Ciencias de la Gestión por la Universidad de Reims Champagne-Ardenne. Sus principales intereses de investigación son la relación entre los bancos y las PYMES, la financiación de las PYMES de alto crecimiento y la estructura de capital de las PYMES.

Hamadou Boubacar es profesor titular de finanzas en la Facultad de Administración de la Universidad de Moncton. Doctor en Ciencias de la Gestión por la Universidad de Reims Champagne-Ardenne (URCA) en 2007, enseñó durante dos años en la URCA, antes de realizar una beca postdoctoral de cuatro meses en el GIREF de la Escuela Superior de Gestión de la Universidad de Quebec en Montreal. Sus intereses de investigación doctoral se centraron en la internacionalización y el rendimiento bancario. Sin embargo, en los últimos años también se ha interesado por el impacto de los mecanismos de gobernanza en los resultados de las empresas en general y de las instituciones de microfinanzas en particular.

List of tables

Table 1

Measures and descriptive statistics

Table 2

Comparison test of exporting SMEs versus SMEs with subsidiaries

Table 3

Correlation Matrix

Table 4

Regression system GMM model results

Notes: The estimates are obtained using Blundell and Bond’s (1998) two-step system GMM. ***, **, * are statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively; the t statistics (in parentheses) are based on White’s heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors; p-values are reported for the AR (1), AR (2) and Hansen statistics.

Table 5

Robustness results using a sample excluding observations with a zero-debt ratio

Notes: The estimates are obtained using Blundell and Bond’s (1998) two-step system GMM. ***, **, * are statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively; the t statistics (in parentheses) are based on White’s heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors; the p-values reported for the AR (1), AR (2) and Hansen statistics.

Table 6

Empirical results for robustness across various measures of internationalization through foreign subsidiaries

Notes: The estimates are obtained using Blundell and Bond’s (1998) two-step system GMM. ***, **, * are statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively; the t statistics (in parentheses) are based on White’s heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors; the p-values reported for the AR (1), AR (2) and Hansen statistics.