Abstracts

Abstract

This paper aims to explore the international development of network organizations. Our analysis is based on an in-depth case study on ONLYLYON, an organization promoting the city of Lyon worldwide through a network of more than 27,000 members. Based on 36 interviews with ONLYLYON members and 103 participant observations realized over two years and a half, our research explores the way ONLYLYON develops its network in Italy. The results show that the Uppsala model partially applies to network organizations and underline the role of interaction between the micro- and meso-levels in the process of network development.

Keywords:

- Networks,

- International development,

- International organizations,

- Case study,

- ONLYLYON

Résumé

Cet article analyse le développement international des organisations en réseau grâce à une étude de cas approfondie sur ONLYLYON, une organisation qui promeut la ville de Lyon dans le monde à travers un réseau de plus de 27 000 membres. Basée sur 36 entretiens avec des membres d’ONLYLYON et 103 observations participantes réalisées sur deux ans et demi, notre recherche analyse le développement du réseau d’ONLYLYON en Italie. Les résultats montrent que le modèle d’Uppsala s’applique partiellement aux organisations en réseau et soulignent le rôle de l’interaction entre les niveaux individuel et organisationnel dans le processus de développement du réseau.

Mots-clés :

- Réseaux,

- Développement International,

- Organisations internationales,

- Etude de cas,

- ONLYLYON

Resumen

Este artículo analiza el desarrollo internacional de las organizaciones en red por medio de un estudio de caso profundizado de ONLYLYON, una organización que promueve la ciudad de Lyon en todo el mundo a través de una red de más de 27.000 miembros. A partir de 36 entrevistas con miembros de ONLYON y 103 observaciones participantes realizadas a lo largo de dos años y medio, nuestra investigación analiza el desarrollo de la red de ONLYLYON en Italia. Los resultados muestran que el modelo Uppsala es parcialmente aplicable a las organizaciones en red y destaca el papel de la interacción entre los niveles individual y organizativo en el proceso de desarrollo de la red.

Palabras clave:

- Redes,

- Desarrollo Internacional,

- Organizaciones Internacionales,

- Estudio de caso,

- ONLYLYON

Article body

In a rapidly changing context, organizations need to develop new strategies to face a complex international environment. Although new opportunities arise from global changes, an increasing level of complexity, uncertainty and risk can be observed. Therefore, organizations need to adapt and evolve faster than they did before to develop their international activities. The Uppsala school proposes a model to explain the way companies evolve in the international environment (Vahlne & Johanson, 2013, 2017)the preeminent theoretical tool applied in studies of the multinational enterprise (MNE and in this model networks play a key role (Meier et al., 2010). However, the model focuses on companies only, whereas many organizations are facing the new challenges of the global economy. This is the case for organizations such as “non-governmental organizations, multi-government organizations and, of course, the regional and national authorities involved directly or indirectly in this process” (Lemaire et al., 2012, p. 11). These are international network organizations, namely organizations that develop internationally through networks (Butera, 1991) as companies do, in line with the business network view (Forsgren et al., 2006).

Although organizations can develop networks to internationalize, they behave differently than companies. As they are not profit-oriented, their presence in foreign countries, which is real and can be assessed, is not established through the traditional mechanisms used to evaluate the degree of internationalization of a company. In addition, even though they do not directly establish a business abroad, they can have a strong impact on business in the long term by attracting people and companies or developing entrepreneurship in a specific area. This issue indicates a first literature gap. According to our knowledge, the international evolution of network organizations has not been studied through the Uppsala model yet. Our analysis of ONLYLYON, an organization promoting the city of Lyon through a network of more than 27,000 ambassadors around the world, aims to fill this gap.

Concerning the level of analysis, the Uppsala model focuses on the meso-level (the company level) and considers the micro-level (the individual level) as a black box (Vahlne & Johanson, 2017). Scholars have recently called for an integration of multiple levels of analysis in the model (Coviello et al., 2017; Galkina & Chetty, 2015) in order to open the black box, in line with the micro-foundation theory that aims to “reduce the use of explanatory black boxes” (Contractor et al., 2019, p. 7). This led us to a second literature gap concerning the role individuals play in the network development processes of organizations.

According to the previous consideration the following research question can be formulated: How do organizations develop their network in foreign countries thanks to their members? From this general question we developed two sub-questions reflecting the two literature gaps we mentioned above:

How do organizations develop networks in foreign countries?

What is the role played by individuals in the international development of a network organization?

In order to answer this question, our paper analyzes the way ONLYLYON develops its network abroad through the actions implemented by its members, called the “ambassadors”. Ambassadors are individuals acting as network entrepreneurs (Burt, 2009) within the organization, establishing concrete actions to develop its international network and brokering opportunities within it. To be more precise, our analysis concerns the creation of an ambassador network in Italy. To meet this goal, we performed a qualitative single case study based on 36 interviews with ONLYLYON members, 103 observations realized over two years and a half and secondary data.

Our results present in detail the three steps of international network development, focusing on the main process and mechanisms from the organizational and individual perspectives. The two levels of analysis are deeply linked and allow us to integrate the micro-level within the Uppsala model, and not just outside, as previous versions of the model did (Coviello et al., 2017; Vahlne & Johanson, 2017). Our article shows that individuals play a key role at each step of the network evolution process and not just in some of them, as the organization does. Finally, after presenting the main contributions and limitations of our analysis, we identify several research perspectives for further studies.

Literature Review

This study focuses on the processes of evolution of organizations in international networks deriving from their members’ actions. In the social sciences, a network is defined as a set of connected exchange relationships between actors (Cook & Emerson, 1978)exchange theory has focused largely upon analysis of the dyad, while power and justice are fundamentally social structural phenomena. First, we contrast economic with sociological analysis of dyadic exchange. We conclude that (a. Moreover, Butera (1991) explains that two additional elements should be considered: structures and operational properties. Network structures can be defined as the configurations of nodes and ties, and they are regulated by operational properties, the rules of the game that make the network work. These properties include elements related to culture, such as a common language, objectives, values and codes, and systems for planning, monitoring and rewarding or sanctioning actors depending on their behaviors.

The concept of network is large, and its field of application is broad. In this paper, we use social exchange theory (Cook & Emerson, 1978)exchange theory has focused largely upon analysis of the dyad, while power and justice are fundamentally social structural phenomena. First, we contrast economic with sociological analysis of dyadic exchange. We conclude that (a to focus on networks that are developed for business purposes. In this context, our paper takes into consideration two different and complementary levels of analysis: the organizational and the individual levels. At the organizational level, social exchange theory is the foundation of the business network view (Forsgren et al., 2006) in which the Uppsala model (Vahlne & Johanson, 2017) is rooted, which enables us to analyze network evolution at the organizational level. Similarly, at the individual level of analysis, social exchange theory represents the theoretical standpoint for our vision of individuals as network entrepreneurs (Burt, 2000). In our literature review, we first focus on the organizational level of analysis before examining its micro-foundations and our conceptualization of the individual level.

Internationalization and Evolution of Companies in Networks

The International Business literature has paid scant attention to the process of network development of organizations, which are facing the same challenges as firms and entrepreneurs are in the international context (Lemaire et al., 2012). Hence, one of the goals of this paper is to provide a framework to study the evolution of international networks in this specific context, by moving from existing literature.

The network approach, also called the business network view, is currently the most prominent theoretical framework used to look at network issues in International Business literature. All the models that incorporate the concept of network, such as the Uppsala evolution model (Vahlne & Johanson, 2013, 2017)the preeminent theoretical tool applied in studies of the multinational enterprise (MNE, entrepreneurship models (Coviello, 2006; Mort & Weerawardena, 2006) and headquarters-subsidiaries relation frameworks (Ghoshal & Bartlett, 1990), just to make some examples, are based upon the principles of the business network view.

Originally developed to integrate the network dimension within the Uppsala model (Forsgren & Johanson, 1994), the business network view considers companies and organizations as networks within networks (Forsgren et al., 2006). In the external context, organizations develop links with political, economic and social actors (Vahlne & Johanson, 2013)the preeminent theoretical tool applied in studies of the multinational enterprise (MNE. In the same way, networks develop within the organization as the result of interaction between different units such as subsidiaries, departments and employees. The network approach is a theory aiming to define the relational nature of companies and organizations; however, it does not explain how networks develop and evolve.

The models relying on the theoretical standpoints of the business network view integrate the network dimension at different levels, such as the inter- or intra-organizational level (Ghoshal & Bartlett, 1990). They also view it as one of the relevant factors to take into account in examining the development of a company, as in the case of entrepreneurship models (Coviello, 2006). However, only the Uppsala evolution model aims to explain the underlying mechanisms of network development (Vahlne & Johanson, 2013, 2017). Originally designed to explain internationalization by looking at the progressive development of knowledge and market commitment in foreign countries (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977), the model has evolved over the years, first incorporating the concept of network from the business network view as a key element of internationalization (Angué & Mayrhofer, 2010; Forsgren et al., 2006; Johanson & Mattsson, 1987), and then focusing on evolution in networks (Vahlne & Johanson, 2013, 2017).

By drawing attention to the importance of networks, the Uppsala model stresses the difference existing between insiders and outsiders (Cheriet, 2015; Johanson & Vahlne, 2009). Insiders can leverage a wide set of existing ties with clients, suppliers, political actors and, sometimes, competitors. Outsiders need to establish links with those actors by investing time and resources in processes of mutual commitment and knowledge development to establish their network position (Blankenburg Holm et al., 1999; Vahlne & Johanson, 2013). As a consequence, insiders perform better than outsiders, who are affected by the homonymous liability (Almodóvar & Rugman, 2015).

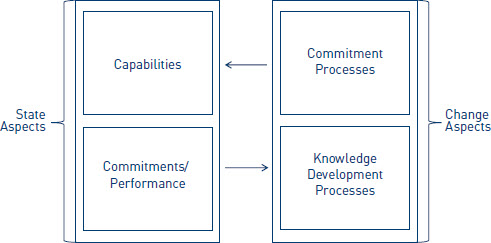

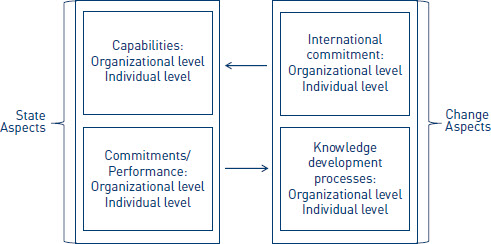

The Uppsala evolution model, represented in Figure 1, explains the mechanism that determine evolution in networks in general and “not only characteristics of the internationalization process in a narrow sense” (Vahlne & Johanson, 2017, p. 1087).

Figure 1

The Uppsala model to study evolution in networks

In the updated model, change and state aspects always interact with each other. The first variable is represented by commitment processes, including those of reconfiguration and change of coordination (Vahlne & Johanson, 2013)the preeminent theoretical tool applied in studies of the multinational enterprise (MNE that occur both inside and outside the firm. These processes are managed under conditions of uncertainty by individuals inside the organization (e.g., managers and entrepreneurs). Another change variable is represented by the knowledge development processes, which include learning, creating and trust building. Those processes, which take place within network structures, can be both inter- or intra-organizational (Vahlne & Johanson, 2013)the preeminent theoretical tool applied in studies of the multinational enterprise (MNE.

Whereas the change variables show the dynamism of the evolution process, the state variables (capabilities and commitments/performance) represent the outcomes of change at a specific time. The model makes a distinction between operational and dynamic capabilities. Operational capabilities depend on the operating mode of the organization, whereas dynamic capabilities allow the company to develop, integrate and reshape competencies to successfully face changes in the network. The second state aspect is labeled “commitments/performance” (Vahlne & Johanson, 2017). In this case, commitments indicate the distribution of assets and resources within different units of the organization (e.g., business units, subsidiaries, and local offices) and include the organization’s relationships and the quality of those relationships. The term performance “refers to what has been achieved already” (Vahlne & Johanson, 2017, p. 1097). Performance can be evaluated in the context of a specific study, in terms of network position, power or profitability (Vahlne & Johanson, 2013, 2017).

This model enables scholars to conduct theoretical and empirical studies on the process of network evolution. Its mechanisms have been used to study companies only, but other typologies of organizations that are less studied in current literature (Lemaire et al., 2012) are developing networks to retrieve information and exploit opportunities. To achieve their goal, they coordinate and link many actors within their own structure. In this context, according to the micro-foundations theory (Contractor et al., 2019; Felin & Foss, 2005), the main actors to consider are individuals, aggregating in meso-level entities such as organizations and companies.

The Role of Individuals in Networks

As previously mentioned, the concept of network was originally introduced in Management from the field of social sciences (Cook & Emerson, 1978) and scholars relying on the Uppsala model have mainly considered network-related issues at the organizational level. In recent years, however, a call for studies concerning the role individuals play in networks emerged. For example, Felin & Foss (2005, p. 441) state that “to fully explicate organizational anything – whether identity, learning, knowledge or capabilities – one must fundamentally begin with and understand the individuals that compose the whole, specifically their underlying nature, choices, abilities, propensities, heterogeneity, purposes, expectations and motivations”. Similarly, Galkina & Chetty (2015) and Coviello et al. (2017) call for studies putting individuals at the heart of networking processes and Vahlne itself (2020, p. 246) asserts that “there are opportunities to improve and apply the Uppsala model, potentially leading to interesting new findings. I outline a few suggestions. One is to take a closer look at the micro-foundations of global strategy”.

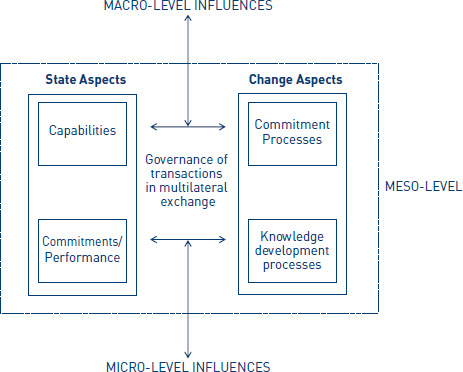

Hence, there is a call for re-discovering the role individuals play in the processes of network development. Those processes “exist on multiple levels. The Uppsala model operates at the level of the individual firm […]. When we record changes at the micro-level, they are to a large extent the aggregate outcomes of processes at the milli-micro level […]. We have mostly treated the mille-micro level as a black box, although we have occasionally looked into the milli-micro foundations of the model” (Vahlne & Johanson, 2017, p. 1089). Scholars have responded to this questioning concerning the level of analysis, and a multi-level approach has been integrated in the Uppsala model (Coviello et al., 2017), as Figure 2 shows.

Moving from the model of Vahlne & Johanson (2017), Figure 2 reproduces the Uppsala evolution model in the meso-level dotted box, to which the micro- and macro-levels of analysis are added. The macro-context includes information technologies and digitalization as the main factors that influence and are influenced by the meso-level (Coviello et al., 2017). In the same way, micro-level factors are pictured outside the dotted box. Table 1 shows an overview of the main levels of analysis, harmonizing the terms employed by Coviello et al. (2017) and in the micro-foundations literature (Contractor et al., 2019) with those one used by Vahlne & Johanson (2017).

Figure 2

The Uppsala evolution model between macro-context and micro-level influences

In this study, we focus on two of the three levels of analysis identified in Figure 2 and Table 1: the organizational and the individual levels, which we call respectively meso and micro-levels, following the tradition of micro-foundations literature.

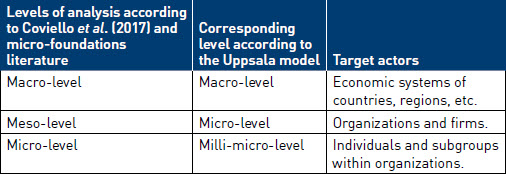

Table 1

Definitions of the levels of analysis

As we already presented the approach of the organization to network development, we now focus on individuals. Kano & Verbeke (2015) argue that individual actions should be viewed as key elements for creating and strengthening management theories. This is in line with Coviello et al.’s (2017) view of micro-level factors, which affirm that ultimately, “it is the individual who, through entrepreneurial action, connects various parts of the organization and the environment, and transforms opportunities into outcomes” (Coviello et al., 2017, p. 1156).

In this study, we rely on studies on structural holes that define an individual as “a person who adds value by brokering connections between others. […] Such people are inherently network entrepreneurs in the sense of building bridges across structural holes” (Burt, 2000, p. 354). From an individual perspective, networks represent opportunity-development pools (Kano & Verbeke, 2015). Network entrepreneurs develop opportunities to achieve both individualistic and common goals within the network (Burt, 2009; Kano & Verbeke, 2015). Thus, individuals may create opportunities for the group, company, or organization they belong to (Shane, 2003). Information and opportunities are detected by network entrepreneurs within the network and organizations leverage individuals to develop those processes.

Moreover, individuals develop behaviors about networks. They may feel they are members of a group or not and compare different networks (Tajfel, 1970). This can create a sense of inclusion and belonging whereby members feel part of an in-group, or it can generate a sense of exclusion and isolation whereby individuals do not feel part of the group (out-group). In the first case, network entrepreneurs exchange information and develop opportunities with each other (Burt, 2009). In the second case, information flows are restricted and opportunities arising within the in-group do not include outsiders (Burt, 2007; Tajfel, 1970).

Regarding the role of individuals in networks, various levels of analysis need to be considered as there is an interplay between the organization and its members. In this context, our paper can contribute to answer the questions raised by international business scholars concerning the role of micro-foundations in network development processes (Contractor et al., 2019; Coviello et al., 2017; Galkina & Chetty, 2015). Our research field fits well with those questionings as the organization we study develops its network thanks to the contribution of its members.

Methodology

Our research methodology is based on the principles of intervention research (Plane, 2000) that enable the researchers to combine managerial innovation and theoretical development. Intervention research “is a special model for designing and steering change, in which design and implementation of new elements are managed simultaneously” (David, 2013, p. 238). The common project between the researcher and the actors of the organization is oriented towards developing knowledge around specific topics and contributing to the evolution of the organization itself (Avenier & Schmitt, 2007; Le Moigne, 2013). In our case, the organization was interested in understanding how the ambassador network could be developed in Italy, and the researcher was chosen to analyze this process because of his participation in the network and his close links with that country.

This methodology is rooted in a pragmatic constructivist epistemological framework as it is defined by Le Moigne (2013) and Avenier (2011). The principles of pragmatic constructivism fit well with intervention research, since they postulate an interaction between subject and object in the research process and the co-construction of reality (Le Moigne, 2013). To better manage our intervention research process, we used an abductive methodology (Atocha Aliseda, 2006)in the second part (section 2 continuously moving between the theoretical framework and the research field, hence constructing knowledge progressively.

Our research is based on a single case study (Yin, 2009) concerning ONLYLYON, an international network organization with its headquarters in France, aiming to promote the city of Lyon through a network of more than 27,000 individuals (called ambassadors) around the world who perform various actions for the organization. In the same way, ONLYLYON provides its ambassadors with the opportunity to meet each other and to develop business opportunities. The decision to focus on a single case study stems from the nature of our research field. The ambassador network of ONLYLYON represents a very specific case (Dyer & Wilkins, 1991; Siggelkow, 2007), and even if many organizations around the world are in charge of promoting a region or a city, no one is doing that through an ambassador network.

The first notable item is that, although ONLYLYON offers its support to its founding members, such as the local chamber of commerce, the tourist office, and the University of Lyon, it has a wider mission then them and is structured differently. Second, ONLYLYON is not fully comparable to other actors of city-regional development such as Barcelona Global. As an independent and non-profit organization, Barcelona Global brings together private organizations, without the leading role and financial contribution of local institutions. In addition, its development is based upon local partners’ initiatives rather than on an international and open ambassador network.

Single case studies are not oriented to provide general conclusions but rather to perform in-depth analysis, which lead a deep understanding of specific phenomena and to the exploration of new research avenues. Following the main guidelines of intervention research, a knowledge project was co-constructed with the organization concerning the development of the ambassador network in Italy. Moreover, in intervention research, the researchers need to participate in organizational change; hence, they need to be viewed as insiders (Plane, 2000). As illustrated in our literature review, insiders perform better than outsiders (Almodóvar & Rugman, 2015); thus, we acted as a member of ONLYLYON, working on a project that was useful for the organization to understand how to further develop the ambassador network in foreign countries.

Our study is based on a wide set of primary data, completed by secondary sources. We collected primary data mainly through participant observations and semi-structured interviews. A total of 103 participant observations were realized over a period of two years and a half. They were collected in different formal and informal contexts related to our research project such as ambassador meetings, ONLYLYON events and activities concerning the organization itself. An observation report was realized within 24 hours from data collection in a standardized grid designed to capture both what happened during observation by using texts and pictures, and the researcher’s interpretation of events.

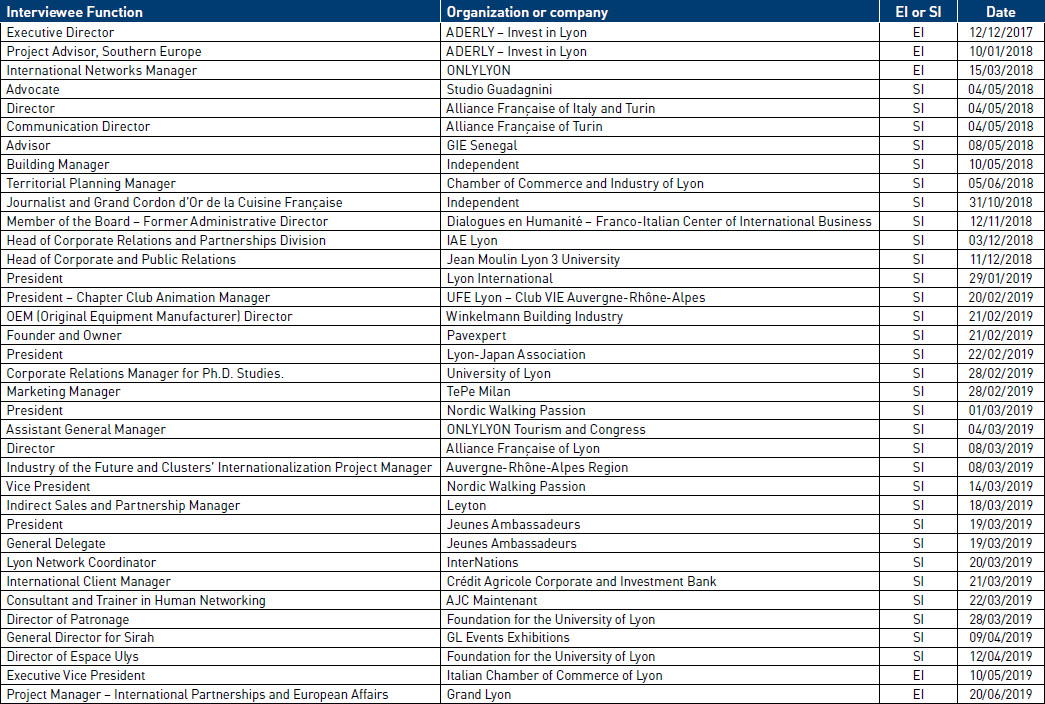

In addition, we conducted 36 interviews, including 5 exploratory interviews (EI) performed before and during the main data collection phase and 31 semi-structured interviews (SI) with an average duration of one hour and 20 minutes each. Interviewees are members of the ONLYLYON ambassador network in Italy and in France, and details concerning the interviews are provided in Table 2.

A content analysis was used to examine the collected primary and secondary data. This kind of analysis fits well with qualitative data, especially with those collected through semi-structured interviews. The coding phase first requires a preliminary analysis. In our study, this step was particularly important because it helped us develop a deeper knowledge of our data, simplifying the analytic process (Bardin, 2007). Coding also requires defining the unit of analysis before breaking the text into units. Although there are many units of analysis that can be chosen for the coding process (e.g.: words, meanings of words, sentences, parts of sentences, and paragraphs), we focused on sentences as the basic units. During the coding phase, we established the process of categorization.

In this study, to ensure greater reliability through a rigorous method of analysis, we used computer-aided qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS). This system supports researchers in the process of defining and validating categories, standardizing classifications, and facilitating a comparative analysis (Allard-Poesi et al., 2001). We used the professional software NVivo to manage our sources, extracting concepts from the and develop categories. We conceived this process as an iterative path and performed this activity through several rounds to enrich our knowledge and understanding of the dataset.

An example may be useful to show how the categorization process was conducted. Here is a verbatim from an ambassador of ONLYLYON we interviewed: “I receive some messages about Lyon… about events in Lyon, but it is not possible for me to participate in those events as I live in Turin. And I have not received any invitation for activities in Turin so far” (Advisor, GIE Senegal). As the unit of analysis is the sentence, two codes were given to the two main sentence. The first sentence was coded with the label “receiving information and news from ONLYLYON”, and the second was labeled as “ONLYLYON does not organize events in Italian cities”. Both are free nodes which are part of a tree node or parent node labeled as “Information collection and opportunity development for ambassadors”, which is logic as the sentences are related: the ambassador receives news from the organization, but this news does not relate to an event taking place in the city where the ambassador lives. This example shows that coding led us to a set of free nodes that were aggregated in tree nodes following a sense-making process. After creating categories, we placed each unit of analysis in the appropriate group. Finally, the different categories and themes identified were used to develop our analysis of results.

Table 2

The exploratory and semi-structured interviews for our study

ONLYLYON: A Network Organization Developing Internationally

In this study, we focus on ONLYLYON, an organization gathering more than 27,000 members worldwide, which is in charge of creating a network to develop opportunities for the city of Lyon in France. ONLYLYON was founded in 2007 to coordinate the efforts of many actors in the region working on the development of Lyon. According to the international networks manager of ONLYLYON: “Those actors were previously establishing independent actions in different fields but without any form of coordination between them”. For example, the tourist office was promoting the city to attract people, and the chamber of commerce was working towards attracting companies, but they were working separately.

The activities of ONLYLYON are managed by an operational team of 10 people. The team is guided by a program coordinator, in charge of harmonizing the actions of the team, which are mainly oriented to network and community management, communication, partnerships and public relations. Within the team, the international networks manager plays a key role, as the position entails developing the ambassador network of the organization in France and abroad. Two other members of the team are in charge of event planning and organization, and the communication director coordinates two community managers and a press and public relations manager. The team is completed by a partnership manager and an assistant in charge of providing support to the other members of the organization.

The core competence of ONLYLYON is managing relations and networks as the specificity of this organization is that it establishes its presence and creates links in many countries thanks to its ambassadors. Ambassadors are individuals who join the organization to promote the city in various ways and who can develop contacts and opportunities for themselves within the ambassador network. Anyone can join the network by invitation from an existing member or by sending an application through the website of the organization. It is noteworthy that people join the network as individuals and not as representatives of their company. Once they have become members, people enter their details, including their contacts, location and job, on the ONLYLYON website. Thus, ONLYLYON owns a large database that can be used to propose specific missions to its ambassadors and that is open to all members, so that individual links can easily be established between ambassadors.

Ambassadors decide how to contribute to the development of the network, and they are free to develop individual and joined actions in line with their competences and preferences. For instance, ambassadors may help attract foreign companies by offering them contacts to help start a business in Lyon, establish partnerships with foreign institutions, promote international exhibitions, welcome tourists, supply information on the local culture and traditions, and recruit other ambassadors. Most of the time, ambassadors are not appointed for specific actions by the organization, but this can happen if there is a specific need on a project or in a geographic area.

Many ambassadors are based in Lyon, but 5,000 members live outside France. In countries like China and Australia, the network is organized in communities, and members meet several times during the year for networking events. In other countries, ambassadors promote ONLYLYON on their own; there are no events enabling them to come together. ONLYLYON ambassadors are coordinated by an operational team and rewarded for their actions. Each member is considered either active or non-active. All active ambassadors have undertaken and declared at least one action to promote and develop Lyon and they receive rewards from the organization such as invitations to exclusive networking events, VIP entrance to international tradeshows, a city pass to visit the most important museums in Lyon, ONLYLYON-branded items and other rewards.

Networking events for active ambassadors take place every month and enable ambassadors to discover new places or popular locations in Lyon, collect information, meet institutional and private partners of the organization and other ambassadors. An ambassador explains that the “main goal of those meetings is to talk about business and about ONLYLYON with other ambassadors. Moreover, each ambassador, by using the ambassador intranet, can retrieve the personal or professional e-mail of other ambassadors and contact them” (Member of the Board, Dialogues en Humanité and FormerAdministrative Director, Franco-Italian Center of International Business).

During our exploratory meeting, we understood that Italy represents an important target for the development of the ONLYLYON ambassador network for several reasons. First, Italy is the second largest trading partner of the region of Lyon in both imports and exports, which shows reciprocity in exchanges. Second, there is a strong cultural, economic and institutional link between Lyon and two major Italian cities, Turin and Milan, which are the main targets for the development of the ONLYLYON network. Lyon and Milan have been twinned since 1966, and a strong institutional cooperation between Lyon and Turin exists since 1991. Every year, missions are organized in these cities to reinforce cooperation. Third, both Italy and France are considered as network friendly contexts, and relationships play a key role in both cultures (Davel et al., 2008).

For those reasons, the development of the ambassador network in Italy was considered a priority for ONLYLYON. However, only a few ambassadors lived in Italy and even fewer in the main target cities of Turin and Milan. Moreover, the organization has not proposed networking events in Italy. In this context, the cooperating with the researcher on the development of the ONLYLYON network in Italy represented a worthwhile project for the organization, which consequently actively supported the study.

Analysis and Discussion of Results

In order to understand how ONLYLYON develops abroad through its members’ activities we will first present the creation of the ambassador network in Italy. In this part we will analyze the main steps to develop a network for ambassadors in a country where nothing was in place, from the establishment to the structuration and the growth of the network. Second, we will discuss our results with reference to our literature review, by paying specific attention not only to the steps of international network development but also to the underlying mechanisms that plays a key role in that process both at the organizational and at the individual level of analysis.

The Creation of the Ambassador Network in Italy

The network of ONLYLYON develops in Italy in different ways. At the organizational level, the operational team of ONLYLYON supports its partners in developing institutional, economic and cultural relationships and events such as the European final of the Bocuse d’Or, a renowned gastronomy competition that recently took place in Turin. In this context, ONLYLYON leveraged the support of local ambassadors. For example, one of them, an Italian journalist, participated in the Bocuse d’Or as the official photographer for ONLYLYON.

Indeed, ONLYLYON develops direct actions, but it also leverages ambassadors to establish its network in Italy. Ambassadors’s actions take place at different levels and each ambassador can decide how to contribute. For example, the president of Nordic Walking Passion explains that he organizes “a trip in Lyon with more than 50 Italian walkers”, thus actively boosting tourism in Lyon. Another example concerns the director of Alliance Française of Italy and Turin who is supporting cultural cooperation between Turin and Lyon: “I already organize some activities such as competitions, and people can win a one week stay in Lyon! […] Then, to help the city of Lyon, we created a guide for French professors who want to organize a school trip to Lyon […] And we participated in a call for projects of the city of Lyon, as we proposed an exhibition with 25 testimonies of people who were living between Turin, Chambery and Lyon”.

However, when we look at the ambassador network of ONLYLYON, we quickly notice some differences between members living in Lyon (local members) and in Italy. Local members are part of a large network and can participate in local events, developing opportunities together and being rewarded for their actions. In contrast, our interviews show that Italian members cannot meet each other as the organization does not establish events in their country. An ambassador explains that “there is nothing in Italy. Nothing is in place. I think that for the international ambassadors, it is important to live the same experiences ambassadors in Lyon can live” (Head of Corporate Relations and Partnerships Division, IAE Lyon). Hence, Italian members may launch relevant actions for the organization, but entirely on their own. Without the opportunity of meeting each other, ambassadors experience a sense of isolation in the network, reinforced by the fact that, as the entire operational team of ONLYLYON is based in Lyon, Italian members usually have not met them since they joined the organization.

Concerning the relationship between the organization and its members, communication and information flows are poor. The ambassadors do not know the main development goals of the organization and sometimes do not feel empowered to act. As the rewarding system, based on events, is missing, ambassadors do not declare their actions and ONLYLYON does not know what ambassadors need and what kind of initiatives they are developing. This result in a sort of liability of outsidership for the organization and its members (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009).

In Italy ONLYLYON can leverage single ambassadors but does not have a structured network. The creation of an ONLYLYON ambassador network Italy represents a case of international network development both at the organizational and individual levels. The elements we considered show that the development of the ambassador network in Italy depends on the commitment (Cook & Emerson, 1978)exchange theory has focused largely upon analysis of the dyad, while power and justice are fundamentally social structural phenomena. First, we contrast economic with sociological analysis of dyadic exchange. We conclude that (a of the Italian ambassadors, with the active support of the ONLYLYON operational team.

According to our ambassador interviews, the network in Italy could be established by organizing events in local cities. The Marketing Manager of TePe Milan, explains that events must occur regularly, following a progressive path:

first, it may be important to organize events in a single city in Italy. […] At the beginning, at least, I think that it may be important to have someone organize the network in Turin or in Milan, with a strong link with Lyon. […] we can also organize that with some volunteers who are put in charge of the organization of events to promote Lyon. Creating meetings between ambassadors may also help create this dynamism. It is a sort of virtuous circle, with people who want to participate and organize. […] We should start gradually and increase the level each time.

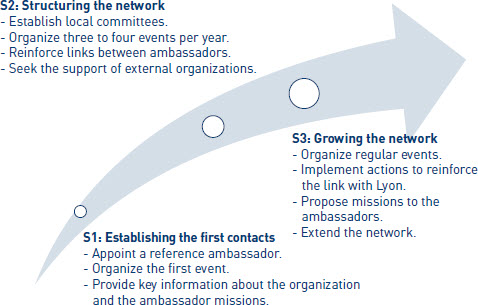

According to the data we collected from observations and interviews, we proposed a three-step path to develop the network in Italy (Figure 3).

In the context of our intervention research project (David, 2013; Plane, 2000), which is oriented towards the development of both theoretical and managerial outcomes, we elaborated a set of propositions for each step. By pointing out the main elements to develop for each step, we provide ONLYLYON with a useful tool to manage the creation of the Italian network.

Figure 3

Establishing the Italian network: A progressive path

Establishing the First Contacts

The first step (S1) involves establishing the firsts contacts. Through this step, a first link is created between: (1) the Italian ambassadors, (2) the Italian ambassadors and the operational team of the organization. The process begins by appointing a reference ambassador in charge of the Italian members. It is important for ambassadors “to know who the person to talk to is when you have a question or a proposal for ONLYLYON” (Indirect Sales and Partnership Manager, Leyton). The reference ambassador should establish a link between the Italian members of the operational team. From a multi-level perspective, the reference ambassador should play the role of agent of ONLYLYON to reinforce the relationship between the organization and its members in Italy (Vahlne & Bhatti, 2018). From a micro-level perspective, that person need to meet the ambassadors in Italy to establish links between them. Based on the assumption that individuals act as network entrepreneurs (Burt, 2000, 2009), creating personal relationships among the Italian ambassadors plays a key role in the networking process. The reference ambassador should also meet the ambassadors in Lyon in order to link the Italian network with the local one.

The reference ambassador should also actively contribute to the organization of the first event in Italy that creates an opportunity for the members to meet each other, thus developing insidership (Blankenburg Holm et al., 2015). Events represent a context for developing communication and information exchanges between ambassadors and between the ambassadors and the organization. Organizing the first event is a way for the organization to demonstrate its commitment to Italy and to develop trust, start the process of learning from one another, and reinforce relationships. According to our interviewees, Turin or Milan should be the first cities to develop ambassador meetings.

Learning processes, information sharing and mutual commitment (Brass et al., 2004) should be encouraged by providing ambassadors with key information about ONLYLYON and the missions ambassadors can develop. Italian members would like to learn more about priority actions to undertake, as they have not been connected to the organization for a long time. By providing this information, the organization develops the foundations for a long-term relationship and exchange with its ambassadors in the sense of Cook & Emerson (1978). Once the first contacts have been established, the network needs to be structured.

Structuring the Network

The second step involves structuring the Italian network. It is important to note that from this point onwards, we consider that the Italian network exists as the key elements outlined by Butera (1991) are developed. Individuals are now linked by ties, relationships take place in a network structure and interaction is shaped by operational properties. In this second step, we present four proposals to structure the network.

To establish the network in Italy should not be difficult for the organization, as ambassadors propose to participate in the organizational processes. In other words, they propose being the (micro-)foundations for the development of the organization: “We can establish local committees in foreign countries, and committees of different countries can meet during the year” (Member of the Board, Dialogues en Humanité and Former Administrative Director, Franco-Italian Center of International Business). Local committees are given the specific mission of developing the network in their cities with the support of the organization and the reference ambassador: “It is important to have many people doing that, so if one of them is not available, another one is around” (Lyon Network Coordinator, InterNations).

The creation of a local committee in each city allows the local network to develop further. As interactions become stronger, relationships are built at the organizational (Johanson & Mattsson, 1987) and the individual levels (Burt, 2009; Cook & Emerson, 1978). In this phase, three or four events per year may be organized in Italy. In this way, new relationships may develop between ambassadors and existing links can be reinforced through multiple contacts.

From an individual viewpoint, the existence of a network enables participants to exchange information and develop opportunities. As the International Client Manager of Crédit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank explains, “it is very important to have a moment in each event for networking. In this way, we can exchange with participants and think about how we can establish cooperation. In the same way, it is important to have new contacts”. The social context of ONLYLYON events leads to the development of business opportunities embedded in the network (Burt, 2007, 2009). By establishing new connections and reinforcing existing links, individuals can detect structural holes and fill them through brokerage activities.

Once the organization has developed its own network, it may consider not only organizational issues such as the coordination of its members, but also relationships with external actors (Vahlne & Johanson, 2013)the preeminent theoretical tool applied in studies of the multinational enterprise (MNE. The presence of ONLYLYON in a specific context implies interactions with the organizations that are established in that context. Through the support of other organizations, ONLYLYON can further develop and better meet the needs of its members. For example, as the rewarding system does not exist in Italy, partners may offer some advantages to the Italian ambassadors. In addition, a partner can offer a space to welcome ambassadors for meetings and events. Partners can be public or private organizations, such as the Alliance Française, the French Chamber of Commerce, or GL Events.

Growing the Network

The third step involves growing the network. This step aims to reinforce the links among ambassadors and between ambassadors and ONLYLYON, through the creation of a strong relationship improving the sense of belonging to the organization (Burt, 2009; Tajfel, 1970).

The first proposition concerns the further development of the network, including the organization of regular events and the implementation of actions that reinforces the link with Lyon. From a micro-level perspective (Contractor et al., 2019), this link depends on the relationship between the ambassadors in Italy and those in Lyon. By establishing joint actions, individuals in Italy can reinforce their contacts with the local network, where the majority of the members are based. Joint actions can include twinned events, videoconferences during events in both cities, and projects that enable members in Italy to travel to Lyon and vice versa.

Once the network is well-established and growing, the organization can propose specific missions to its ambassadors. This is our third proposition for this step. Ambassadors are ready to propose innovative projects, develop twinning programs and invite new ambassadors to join the network. However, they also want to receive specific missions together with a mandate (e.g., a certificate for ambassadors or business card) from the organization to develop strategic actions. Proposing missions can help the organization implement strategic development goals, and a mandate can provide Italian ambassadors with the legitimacy they are looking for. In management research, this corresponds to the need to feel part of a structured relationship with the organization (Blankenburg Holm et al., 1999).

In this phase, mutual commitment, knowledge development and trust are strong (Vahlne & Bhatti, 2018), and Italian members can play a key role in developing the network. This issue is noteworthing as the international network can grow within a specific context only when it is well-established. For example, many ambassadors explained that to invite people to join the network, the network must already exist in Italy. The further development of the Italian network consists of extending the network, attracting new ambassadors and establishing new partnerships with organizations. Regarding the people who can join the network in Italy, the targets should be individuals who have lived in Lyon previously and are now living in Italy. At an inter-organizational level (Vahlne & Johanson, 2013)the preeminent theoretical tool applied in studies of the multinational enterprise (MNE, ONLYLYON can establish partnerships with other organizations. By coordinating the network with those organizations, it can improve its degree of insidership and develop its network faster (Blankenburg Holm et al., 2015).

Discussion of Results: The Development of the Italian Network, the Ambassadors and the Uppsala Model

Our analysis shows that network development and evolution in a foreign country is represented as a virtuous circle and an expanding process, in which “the interplay between knowledge development and commitments is the driving force” (Vahlne & Bhatti, 2018, p. 1). Originally developed to study the process of international network evolution in companies, the main mechanisms of the Uppsala evolution model (Vahlne & Johanson, 2013, 2017)the preeminent theoretical tool applied in studies of the multinational enterprise (MNE can also be found in the context of a network organization, but with several differences. Figure 4 represents, within the context of an organization and by specifically looking at the role of individuals, the main elements of the network development process that can be linked to the theoretical framework of the Uppsala model. We will first present each aspect of the model proposed in Figure 4 before focusing on the main differences with the original framework and on the answers to our research questions.

Figure 4

International network evolution of organizations based on the Uppsala model

The commitment of an organization in a foreign country is a process that includes reconfiguration and change of coordination in the existing networks (Vahlne & Johanson, 2013)the preeminent theoretical tool applied in studies of the multinational enterprise (MNE. However, the reconfiguration process does not take place at the organizational level only but implies a relationship commitment decision (Vahlne & Bhatti, 2018) concerning local ambassadors. This point differs from the original Uppsala model in which the commitment usually concerns an external market or external entity. Our findings demonstrate that this commitment concerns primarily the members of the organization, as the relationship among and with them can be affected by a sort of internal liability of outsidership (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009) known at the individual level as intergroup discrimination (Tajfel, 1970).

The change of coordination concerns the whole network of an organization. Establishing a community in a foreign country leads to the extension of the whole network and improves coordination between members in that country so “they can serve better the common organizational purpose” (Vahlne & Johanson, 2017, p. 1093). However, that process requires an effort of coordination at an individual level (the reference person and the members of local committees in the present case). Individuals who perform coordination actions need to commit developing specific opportunities for the organization (Shane, 2003) through entrepreneurial action (Burt, 2007). They must also be rewarded for their efforts, and the best reward for ambassadors consists in having access to an existing network that enables them to collect information and broker opportunities (Burt, 2007, 2009). Thus, the commitment of the organization in establishing and developing a foreign network depends on the commitment of its members.

Together with the commitment decision, the knowledge development processes influence the evolution of the organization’s international network (Vahlne & Johanson, 2013, 2017)the preeminent theoretical tool applied in studies of the multinational enterprise (MNE. Organizations continuously conduct processes such as learning, creating, and trust-building, which are deeply linked to relationship development and commitment (Vahlne & Bhatti, 2018). To develop its network abroad, the organization needs to build trust with its members and between its members. In this context, learning is also important. In our case study, the ambassadors need to receive information about Lyon and their missions from the organization. Then, they learn what the organization is developing and what it is looking for, and they identify useful information and opportunities. Moreover, the organization needs to better know its members in foreign countries and understand the contributions they can provide and the rewards they expect to develop something new (creation of links, opportunities, actions etc.).

In this respect, the model we propose in Figure 4 differs from the Uppsala model, as knowledge development processes do not take place between meso-level actors only (Vahlne & Johanson, 2017) or in the context of a customer-supplier relationship (Vahlne & Bhatti, 2018). Instead, they are multi-level processes that take place between the organization and its members (meso-micro) and among its members (micro-micro). By establishing contacts in the network, individuals exchange information, establish informal rules for interaction, identify opportunities and decide whether to exploit the latter together.

The Uppsala model posit that the interplay between commitment and knowledge development processes results in the gain of new capabilities. The study shows that operational and dynamic capabilities, including opportunity development, networking and internationalization capabilities are developed at both the organizational and the individual level through network-entrepreneurial actions (Burt, 2009). At the organizational level, reinforcing the foreign network means strengthening the whole network and increasing the number of opportunities that can be developed. At the individual level, this results in a larger and dynamic network promoting the development of new opportunities (Burt, 2009)

The “commitments/performance” state aspect of the Uppsala evolution model represents “the outcome of the change process” (Vahlne & Johanson, 2017, p. 1097). The changes in the network configuration are linked to the performance of the initiatives that were developed in target country and influences the future commitment of the organization. By establishing a network in a foreign country, the organization affirms its commitment towards the international members who need to meet each other and feel that the organization cares about their community. This commitment can be progressively increased, thus reinforcing the presence of the organization in the country (Johanson & Vahlne, 2009). Organizational commitments affect individual commitments, which results in a more dynamic network.

Whereas commitments have a strong forward-looking connotation, performance focuses on results (Vahlne & Johanson, 2017). In our case study, by developing the network, ONLYLYON can improve its performance, meet the ambassadors’ needs and encourage them to improve the quality and quantity of the actions they perform without investing significant resources. ONLYLYON just need to “put the ambassadors at the heart of the project” (Consultant and Trainer in Human Networking, AJC Maintenant). In that way, an organization can improve performances at the individual level too.

Figure 4 shows the modifications made to the models of Vahlne and Johanson (2017) and Coviello et al. (2017), represented in Figures 1 and 2, as a result of our investigations. The structure of the Uppsala evolution model is preserved, but several differences are in evidence.

First, the scope of the Uppsala model is enlarged. The amended version we propose is designed to depict network evolution processes within the context of an organization. The original Uppsala model focused on the internationalization of companies (Johanson & Vahlne, 1977). When the business network view was integrated in this theoretical framework (Forsgren & Johanson, 1994), the goal of the model became to describe the international network development of companies. When the Uppsala school proposed to extend the scope of the model from international development to network evolution (Vahlne & Johanson, 2013, 2017)the preeminent theoretical tool applied in studies of the multinational enterprise (MNE, the focus was still on companies. Our analysis opens a new research path by showing that the main mechanisms of network evolution processes proposed in the new model can be relevant not only for companies but for organizations at large. This new focus can provide scholars who are interested in the international network development of organization with a solid framework to look at a research object that was neglected in the past (Lemaire et al., 2012).

Second, the individual level black box was opened, and the micro-level of analysis is not simply taken into account, such as the macro-context, as an external element influencing the Uppsala model as proposed by Coviello et al. (2017). Instead, it is included in the model itself as an internal key factor. Now, every single dynamic or state aspects of the model clearly shows that the process of network development and evolution is implemented both by the organization and its members through continuous interplay. The micro-level is finally internalized within the model and considered as foundational in the original sense of the word (Contractor et al., 2019).

Linking the two levels is particularly relevant as a network exists, develops and grow only if both the organization and its members commits to the process presented in Figure 4. For example, in the initial situation, ONLYLYON assumes that the network exists in Italy as several members live in that country. However, individuals, who are not linked to each other yet do not feel part of a network, experience a sense of intergroup discrimination (Tajfel, 1970) and are affected by a sort of liability of outsidership (Blankenburg Holm et al., 2015). Indeed, according to the definition of Butera (1991), in Italy the network does not exist yet. Ambassadors live there, and they are linked to the organization, but in the Italian context, there is a lack of connections at the individual level, the network is not structured, and the operational properties are not established. In this context, structural holes (Burt, 2009) cannot be exploited by ambassadors neither to develop and broker opportunities for themselves (Burt, 2007; Kano & Verbeke, 2015), nor to establish joint actions for ONLYLYON.

Third, as the micro-level enters the Uppsala model, we can further expand the scope of this theoretical framework that is now oriented to examine not just the evolution of an organization, but also the behavior of network-entrepreneurs within an organization. General characteristics of individuals such as their entrepreneurial attitude (Burt, 2009), brokerage and development of opportunities (Burt, 2007), bounded rationality and reliability (Kano & Verbeke, 2015) have already been investigated at the individual level. In these studies, the network represented the context for information exchange and opportunity development. Our analysis shows how individuals can contribute to the development of the network itself.

Conclusions

Moving from the gaps underlined in our literature review, the goal of this paper was to answer the following research question: how do organizations develop their network in foreign countries thanks to their members? This was detailed in two sub-questions: How do organizations develop networks in foreign countries? What is the role played by individuals in the international development of a network organization? Thus, our analysis presents several academic and managerial contributions.

First, it allows scholars to investigate the mechanisms of the international network development process in organizations. Our analysis shows that the Uppsala model (Vahlne & Johanson, 2013, 2017)the preeminent theoretical tool applied in studies of the multinational enterprise (MNE, designed to analyze the evolution of companies, seems relevant to explain the interaction between change and state aspects in organizations. Even though the reasons for internationalizing are not the same for companies and organizations, the process of network evolution looks somehow similar and shows a progressive development of relationships. In this context, further studies following a comparative approach may help bring out the differences and similarities of network evolution in companies and organizations.

Second, as we conceived our study as a multi-level analysis (Brass et al., 2004; Contractor et al., 2019)2019, focusing on both the micro- and meso-levels, our contributions also concern the role of individuals in organizations. Our study internalized the micro-level of analysis in the Uppsala model, thus providing an answer to many recent calls for studies oriented to opening the individual black box (Contractor et al., 2019; Coviello et al., 2017; Felin & Foss, 2005; Galkina & Chetty, 2015). In this context, our analysis establishes a link between the individual and the organizational levels, internalizing the micro-level in every aspect of the Uppsala model. Our investigation has shown that the process of network development is implemented at the same time by the organization and its members. In other words, it seems that the network is created and developed through the interaction between the meso- and micro-levels. This finding represents a major contribution to the debates concerning micro-foundations and opens new avenues for researches following a multi-level approach.

Previous studies shows that people act as network entrepreneurs, characterized by bounded rationality and reliability (Kano & Verbeke, 2015), develop bridges across structural holes and broker information and opportunities (Burt, 2007, 2009). Our analysis brings to light the role of a specific kind of network entrepreneurs: the ambassadors. Of course, ambassadors develop opportunities in their own interest, but they also commit to a specific mission: growing and contributing to the improvement of the organization’s network. Developing an analysis specifically oriented to understanding the behavior of network ambassadors may be of great value to scholars in management as well as in the social sciences at large.

At the same time, our paper provides important managerial contributions to ONLYLYON. We have proposed a progressive path to develop the ambassador network in Italy, and each step includes a set of managerial propositions for ONLYLYON. After conducting our research, we presented our results to the organization and several of our propositions, including the creation of the first ambassador event in Turin, the search for a reference ambassador and a local committee, are currently being implemented. We plan to continue this common project with ONLYLYON regarding the development of the Italian network, which will also enable us to enhance our longitudinal analysis.

Together with contributions, our study presents some limitations as well. First, a single case study (Siggelkow, 2007) conducted on a very specific organization, is not oriented to develop generalizable results, but rather to develop new theories. As our goal was to explore new research avenues and open theoretical black boxes, this approach has enabled us to perform an in-depth analysis of a unique network organization. Following a multiple case study approach (Eisenhardt, 1989), future investigations could extend the scope of the research within ONLYLYON or other organizations. In this context, it will be possible to combine qualitative and quantitative data and perform comparative analyses.

Second, the context of our study was restraint to a French organization developing its network in a neighboring country: Italy. Future studies may look into different kinds of organizations, following a qualitative approach. Also, further researches must focus on different contexts and different countries, considering elements such as cultural and geographical distance. Third, it would be worth comparing the development of organizations and companies in order to understand how they build local networks differently to overcome the liability of outsidership.

Finally, from a multi-level perspective we need to stress that, even though our paper introduces the role of individuals in the Uppsala model, as recommended by scholars (Contractor et al., 2019; Coviello et al., 2017), further studies must also take into account the role the macro-context plays in this model. Keeping the focus on the multi-level approach, the quest for a model investigating the interaction between different levels of analysis in the processes of network development needs to continue.

Appendices

Biographical note

Stefano Valdemarin is a permanent professor of International Management and Strategy at ESSCA School of Management. He obtained a Ph.D. in Management Sciences at the University of Lyon, a master’s degree in international economics at the University of Turin (Italy) and a master’s degree in International Management at IAE Lyon. His research and teaching activities focus on international development strategies and on the creation of opportunities in relationship networks. On these topics, he cooperates with multinational companies, universities and international organizations to develop projects establishing a bridge between theory and practice.

Bibliography

- Allard-Poesi, Florence; Drucker-Godard, Carole; Sylvie, Elhinger (2001). “Analyzing representations and discourse”, in R-A. Thietart et al., Doing Management Research, London, SAGE, p. 351-372.

- Almodóvar, Paloma; Rugman, Alan M. (2015). “Testing the revisited Uppsala model: Does insidership improve international performance?”, International Marketing Review, Vol. 32, N° 6, p. 686-712.

- Angué, Katia; Mayrhofer, Ulrike (2010). “Le modèle d’Uppsala remis en question: Une analyse des accords de coopération noués dans les marchés émergents”, Management International, Vol. 15, N° 1, p. 33-46.

- Atocha Aliseda, Llera (2006). “What is abduction? Overview and proposal for Investigation”, in L. Atocha Aliseda, Abductive Reasoning. Logical Investigation into Discovery and Explanation, Dordrecht, Springer, p. 27-50.

- Avenier, Marie-José (2011). “Les paradigmes épistémologiques constructivistes: Post-modernisme ou pragmatisme”, Revue Management et Avenir, Vol. 43, N° 3, p. 372-391.

- Avenier, Marie-José; Schmitt, Christophe (2007). “Élaborer des savoirs actionnables et les communiquer à des managers”, Revue Française de Gestion, Vol. 174, N° 5, p. 25-42.

- Bardin, Laurence (2007). L’analyse de contenu, Paris, PUF, 291 p.

- Blankenburg Holm, Désirée; Eriksson, Kent; Johanson, Jan (1999). “Creating value through mutual commitment to business network relationships”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 20, N° 5, p. 467.

- Blankenburg Holm, Désirée; Johanson, Martin; Kao, Pao (2015). “From outsider to insider: Opportunity development in foreign market networks”, Journal of International Entrepreneurship, Vol. 13, N° 3, p. 337-359.

- Brass, Daniel J.; Galaskiewicz, Joseph; Greve Henrich R., Tsai Wenpin (2004). “Taking stock of networks and organizations: A multilevel perspective”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 47, N° 6, p. 795-817.

- Burt, Ronald S. (2000). “The network structure of social capital”, Research in Organizational Behavior, Vol. 22, p. 345-423.

- Burt, Ronald S. (2007). Brokerage and closure: An introduction to social capital, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 290 p.

- Burt, Ronald S. (2009). Structural holes: The social structure of competition, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 325 p.

- Butera, Federico (1991). La métamorphose de l’organisation: Du château au réseau. Paris, Éditions d’Organisation, 245 p.

- Cheriet, Foued (2015). “Est-il pertinent d’appliquer le modèle d’Uppsala de l’internationalisation des entreprises à l’analyse des nouvelles implantations des firmes multinationales?”, Management International, Vol. 19, N° 4, p. 121-139.

- Contractor, Farok; Foss, Nicolai J.; Kundu, Sumit; Lahiri, Somnath (2019). “Viewing global strategy through a microfoundations lens”, Global Strategy Journal, Vol. 9, N° 1, p. 318.

- Cook, Karen S.; Emerson, Richard M. (1978). “Power, equity and commitment in exchange networks”, American Sociological Review, Vol. 43, N° 5, p. 721-739.

- Coviello, Nicole; Kano, Liena; Liesch Peter (2017). “Adapting the Uppsala model to a modern world: Macro-context and microfoundations”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 48, N° 9, p. 1151-1164.

- Davel, Eduardo; Dupuis, Jean-Pierre; Chanlat, Jean-François (2008). Gestion en contexte interculturel: Approches, problématiques, pratiques et plongées, Laval, Presses de l’Université Laval, 472 p.

- David, Albert (2013). “Intervention methodologies in management research”, in A. David, A. Hatchuel and R. Laufer, New foundations of management research: Elements of epistemology for the management sciences, Paris, Presses des Mines, p. 227-249.

- Dyer, William Gibb; Wilkins, Alan L. (1991). “Better stories, not better constructs, to generate better theory: A rejoinder to Eisenhardt”, The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 16, N° 3, p. 613-619.

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. (1989). “Building theories from case study research”, The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14, N° 4, p. 532-550.

- Felin, Teppo; Foss, Nicolai J. (2005). “Strategic organization: A field in search of micro-foundations”, Strategic Organization, Vol. 3, N° 4, p. 441-455.

- Forsgren, Mats; Holm, Ulf; Johanson, Jan (2006). Managing the embedded multinational: A business network view, Cheltenham, Edward Elgar, 239 p.

- Galkina, Tamara; Chetty, Sylvie (2015). “Effectuation and networking of internationalizing SMEs”, Management International Review, Vol. 55, N° 5, p. 647-676.

- Johanson, Jan; Mattsson, Lars-Gunnar (1987). “Interorganizational relations in industrial systems: A network approach compared with the transaction-cost approach”, International Studies of Management & Organization, Vol. 17, N° 1, p. 34-48.

- Johanson, Jan; Vahlne, Jan-Erik (1977). “The internationalization process of the firm-A model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 8, N° 1, p. 23-32.

- Johanson, Jan; Vahlne, Jan-Erik (2009). “The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 40, N° 9, p. 1411-1431.

- Kano, Liena; Verbeke, Alain (2015). “The three faces of bounded reliability: Alfred Chandler and the micro-foundations of management theory”, California Management Review, Vol. 58, N° 1, p. 97-122.

- Le Moigne, Jean-Louis (2013). “Épistémologies constructivistes et sciences de l’organisation”, in A.C. Martinet and Y. Pesqueux, Epistémologie des sciences de gestion, Paris, Vuibert, p. 81-140.

- Lemaire, Jean-Paul; Mayrhofer, Ulrike; Milliot, Eric (2012). “De nouvelles perspectives pour la recherche en management international”, Management International, Vol. 17, N° 1, p. 11-23.

- Meier, Olivier; Meschi, Pierre-Xavier; Dessain, Vincent (2010). “Paradigme éclectique, modèle Uppsala… Quoi de neuf pour analyser les décisions et modes d’investissement à l’international?”, Management International, Vol. 15, N° 1, p. VX.

- Plane, Jean-Michel (2000). Méthodes de recherche-intervention en management, Paris, L’Harmattan, 256 p.

- Shane, Scott A. (2003). A general theory of entrepreneurship: The individual-opportunity nexus, Cheltenham, Edward Elgar, 356 p.

- Siggelkow, Nicolaj (2007). “Persuasion with case studies”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 50, N° 1, p. 20-24.

- Tajfel, Henri (1970). “Experiments in intergroup discrimination”, Scientific American, Vol. 223, N° 5, p. 96-102.

- Vahlne, Jan-Erik; Bhatti, Waheed A. (2018). “Relationship development: A micro-foundation for the internationalization process of the multinational business enterprise”, Management International Review, Vol. 59, N° 2, p. 126.

- Vahlne, Jan-Erik; Johanson, Jan (2013). “The Uppsala model on evolution of the multinational business enterprise – from internalization to coordination of networks”, International Marketing Review, Vol. 30, N° 3, p. 189-210.

- Vahlne, Jan-Erik; Johanson, Jan (2017). “From internationalization to evolution: The Uppsala model at 40 years”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 48, N° 9, p. 1087-1102.

- Yin, Robert K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods, 4th edition, Thousand Oaks, SAGE, 240 p.

Appendices

Note biographique

Stefano Valdemarin est professeur permanent en Management international et Stratégie à l’ESSCA School of Management. Il a obtenu un doctorat en Sciences de Gestion à l’Université de Lyon, un master en économie internationale à l’Université de Turin (Italie) et un master en Management international à l’IAE Lyon. Ses activités de recherche et d’enseignement se concentrent sur les processus d’internationalisation et sur la création d’opportunités stratégiques dans les réseaux relationnels. Sur ces sujets, il coopère avec des multinationales, des universités et des organisations internationales en développant des projets établissant un pont entre la théorie et la pratique.

Appendices

Nota biográfica

Stefano Valdemarin es profesor permanente de Gestión Internacional y Estrategia en la ESSCA School of Management. Es doctor en Ciencias de la Gestión por la Universidad de Lyon, tiene un máster en Economía Internacional por la Universidad de Turín (Italia) y un máster en Gestión Internacional por el IAE Lyon. Sus actividades de investigación y docencia se centran en los procesos de internacionalización y en la creación de oportunidades estratégicas en las redes relacionales. En este tema, colabora con empresas multinacionales, universidades y organizaciones internacionales, desarrollando proyectos de investigación-intervención.

List of figures

Figure 1

The Uppsala model to study evolution in networks

Figure 2

The Uppsala evolution model between macro-context and micro-level influences

Figure 3

Establishing the Italian network: A progressive path

Figure 4

International network evolution of organizations based on the Uppsala model

List of tables

Table 1

Definitions of the levels of analysis

Table 2

The exploratory and semi-structured interviews for our study

10.7202/045623ar

10.7202/045623ar