Abstracts

Abstract

How can multicultural workgroups achieve synergy and become teams? To answer, we resorted to non-participant observation of six workgroups at university. The data were collected in 41 interviews and 14 meetings. Three types of workgroup were distinguished depending on the scope for individual singularities to assert themselves or for a shared identity to be developed. The principal findings are that a workgroup’s success depends on implementing self-regulation to move from personal to common interests and from toleration to tolerance. This is independent of its heterogeneous/homogeneous composition, which is a matter of perception and varies during the different stages of team-building.

Keywords:

- Team-building,

- heterogeneous workgroups,

- multicultural team,

- synergy,

- tolerance and toleration,

- common interest

Résumé

Comment les groupes de travail multiculturels peuvent-ils devenir des équipes synergiques ? Nous avons mené une observation non participante de six groupes de travail à l'université en appui sur 41 entretiens et 14 réunions. Trois dynamiques de groupes ont été distinguées variant en fonction de l’affirmation des individualités et de l’existence d'une identité collective. Selon nos résultats, la réussite d’une équipe dépend de l’émergence d’une autorégulation favorisant la focalisation sur les intérêts communs et un changement de conception de la tolérance. Elle est indépendante de l’hétérogénéité/homogénéité du groupe, qui relève des perceptions et varie au cours du développement de l’équipe.

Mots-clés :

- Team-building,

- Groupe hétérogènes,

- équipes multiculturelles,

- synergie,

- tolérance,

- intérêt commun

Resumen

¿Cómo pueden los grupos de trabajo multiculturales convertirse en equipos sinérgicos? Realizamos una observación no participante de seis grupos de trabajo en la universidad en apoyo de 41 entrevistas y 14 reuniones. Se han distinguido tres dinámicas grupales, que varían según la afirmación de las individualidades y la existencia de una identidad colectiva. De acuerdo con nuestros resultados, el éxito de un equipo depende de la aparición de la autorregulación que favorezca el enfoque en los intereses comunes y un cambio en la concepción de la tolerancia. Es independiente de la heterogeneidad/homogeneidad del grupo, que es la percepción y varía durante el desarrollo del equipo.

Palabras clave:

- Formación de equipos,

- Grupo heterogéneo,

- Equipos multiculturales,

- Sinergia,

- Tolerancia,

- Interés común

Article body

One of the consequences of the international context is the growing number of workgroups of people from different countries, commonly referred to as “multicultural teams”. The apparent difficulty that they encounter in implementing a collective project seems to stem from their heterogeneous composition, considered a handicap for really working in teams. Indeed, previous studies have highlighted the role played in workgroup performance by interpersonal congruence. They define this notion as the degree to which workgroup members see each other’s in the same way (Polzer et al., 2002). The heterogeneity of referents is a potential source of dysfunctions which can generate conflicts (Pelled, 1996), freeze the collective work (O’Reilly et al., 1993), and bring about the dissolution of the workgroup. However, numerous researchers in different fields have shown that the effect of shared action is greater than the sum of the effects to be expected if the actors had acted independently (Greco et al., 1995; Vignat, 2012). This designates the synergy process without a clear definition and with a confusion between the process itself and its result. The link between some workgroup dynamics and performance has been demonstrated (Ayub and Jehn, 2014; Mathieu et al., 2017; Peterson et al., 2003). The term synergy is “derived from the Greek sunergos, which means ‘working together’ […]”. It is frequently used to refer to “a gain in performance that is attribuTable in some way to group interaction” (Larson, 2010, p.2 and p.4). The object of research is not the factors of performance but the process leading to synergy. Without it, workgroups do not work as teams and their results are less good than when working individually. Then, the research questions addressed here are: How can workgroups achieve synergy and become teams? Is their specific heterogeneous composition an obstacle to working together and succeeding?

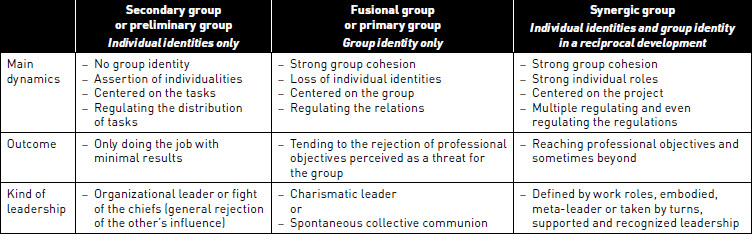

In this article, we first define the different concepts and our theoretical framework. Based on a literature review it is proposed to distinguish three types of workgroups: secondary, fusional and synergic, according to the scope for individual singularities to assert themselves or for a shared identity to be developed. In secondary workgroups, the members work together but as a coordination of individual activities and without added value. In fusional workgroups, the outcomes are collective and different from the sum of the individual productions. Only a synergic workgroup reconciles the existence of every member’s differences and a coherent whole. In such a team, everyone knows that regulation is necessary to avoid two pitfalls: the omnipotence of fusion or the fragmentation of the secondary workgroup. From this typology, four stages of team-building towards synergy are modeled. Further analysis of the literature is then presented to clarify the problematic of a specific heterogeneous workgroup: the multicultural one.

To answer the general research questions, the methodological approach is exploratory and qualitative. We resorted to non-participant observation of six workgroups of six to eight university students (executives). Each workgroup prepared a similar project with the same deadline. A comparative longitudinal study was carried out to identify each team’s process and the impact of the initial values formalized in a charter. Our data were collected through 41 non-directive interviews and 14 observed meetings. They were all recorded and complemented with a case report form. A content analysis was then performed based on criteria derived from our literature review or which emerged through the interviews.

The main contribution of the study is to identify in each workgroup the existence of a collective representation of heterogeneity/homogeneity, which evolves with the stages of team-building. To achieve synergy, the dynamic of the collective conceptions appears more important than the initial individual ones or the objective differences among people. Our findings contribute to fill a gap in multicultural team management theories and to clarify the concept of synergy. The problem of multicultural workgroups is not objective heterogeneity but the emergence of self-regulation, the coaching of which essentially defines the potential role of management. Homan et al. (2008) emphasized the importance of the recognition of differences in teams and of the members’ openness to experience of group work. But for those authors, facing up to differences with an open mind is a personal characteristic, which again refers to the issue of the workgroup’s composition. According to our findings, this characteristic is the result of workgroup dynamics and represents a collective capability of the synergic team. To identify it, our results led us to go back to the literature. Crick’s (1971) distinction between the concept of tolerance and the concept of toleration allows us to go further. The first, tolerance, is open and considers heterogeneity as a potential resource. For the second, toleration, homogeneity is the preferred state and differences are constraints and a source of unavoidable conflicts. In our study, synergy appears as a shared will to adopt an attitude of tolerance and to focus on what the workgroup members called “the common interest” of the workgroup. Then the modeling of workgroup dynamics towards and of synergy is complemented and discussed.

Theoretical Framework of Small Group Dynamics

Numerous studies have shown that the process operating within workgroups is much more than a good coordination of the individual efforts. It could even be something else. To specify the theoretical framework of this study the theories of small group dynamics were analyzed (Anzieu and Martin, 1982; Bales, 1951; Blanchet and Trognon, 2011; Forsyth, 2017, Homans, 1958; Rico et al., 2011). The starting point is the definition of the small group in 1950 by Homans (2017, p. 85) with the assertion that it is a group “each member of which is able to interact with every other member”. This positions the approach to the workgroup in the interactionist current. Bales (1951, p. 33) introduced, among other things, the role of “perception of each other member” and detailed a research method to study small groups through analysis of the interactions during their meetings. The contributions of other authors marked a decisive advance in knowledge. For example, Lewin introduced the concept of group dynamics: people behave differently with others than alone (Kaufmann, 1968). He showed the influence of social exchanges on individual representations. In particular, he explained as regards the interaction between two persons that “analyzing the two psychological (‘subjective’) fields gives the basis for predicting the actual (‘objective’) next step of behavior” (Lewin, 1947, p. 11). The theories of Kaës (1976) are also important: he considers that the group is an apparatus of connection and transformation of the psyches of its members, and that a shared psychic reality arises from this.

It appears from the literature review (Ashmore et al., 2004; Ellemers, 2012; Haslam and Ellemers, 2016; Roccas et al., 2008; Tajfel, 1974) that the emergence of a singular group identity is necessary to become a team and reach the professional objectives of the workgroup. Without it, there is no reason for doing the job with others and the results are better individually. In such dynamics, each one undertakes in the group to do things that he/she considers unthinkable when he/she is alone (Kurtzberg and Amabile, 2001). In management studies, researchers generally approach the notion of group identity through its effects on its members: their salient group membership, identified through terms such as “we”, or their efforts to avoid “letting down their team” (Babcock et al., 2015; Charness and Holder, 2018; Chen and Li, 2009; Coman and Hirst, 2015). While cohesion or a shared identity is needed to legitimate the collective work, its success also depends on the development of individual forms of influence (Hackman et al., 1986). This second point presupposes two ideas: first, not all members of the workgroup are similar; secondly, their differences are a resource for the team.

Proposal for a Typology of Workgroups

Regarding the scope for individual singularities to assert themselves or for a shared identity to be developed, three types of workgroup can be distinguished: secondary, fusional and synergic (Table 1). For the sociologist Cooley (2002), the fusional group is the primary stage of group dynamics. The secondary type is a preliminary stage: in this state, individuals are gathered to do something together, but the group does not really exist. Nothing is shared, and each member of the workgroup behaves according to the calculation of his/her personal gains or losses without considering the possibility of another individual factor of motivation (Meglino and Korsgaard, 2004), or the existence of collective dynamics. In secondary and fusional groups, the members must choose between their individual identities and the group identity, which are seen as threats to each other.

The synergic group transcends the individuals/group dilemma alternatives. Each is developed by the other (De Dreu, 2006; Spears, 2016) in an interdependent process (Kiggundu, 1983). The group identity of synergic teams does not represent either the sum of the individual identities, or their renunciation. It results from the reciprocal building of an ad hoc micro-identity which leads to the emergence of an evolving set of references and fundamental assertions, shared by all the group members. Like the organizational culture (Thévenet and Vachette, 1992; Karjalainen, 2010), the group identity allows them to work together. In these dynamics, everyone has a strong contribution which is supported and recognized by the group. In the literature, four distinct approaches to team regulation are defined: goal-setting, developing interpersonal relations, clarifying roles, and employing problem-solving techniques (Klein et al., 2009). In the synergic dynamic, the group members combine them all according to the needs of the project. Belbin (2010, 2012) identified nine team roles at work. They must be taken on to ensure successful group self-regulation (Cummings, 1978; Higgins and May, 2016) or efficient leadership. In this study, leadership is defined, according to the functional approach, as “a driving system required by and for the functioning of the group” (Maisonneuve, 2018, p. 61). Even in the case of a single leader, the other members continue to act in the process. With a conception close to Follett’s theory (Metcalf and Urwick, 1940), the role of the leader is to support their contribution and even their own leadership. The leader of a synergic group leads the leaders (Groutel et al., 2010) not as a “super-chief” but as a coach of leaders (Hackman, 2002) or a “meta-leader”. In previous studies (Davis and Eisenhardt, 2011; Forsyth, 2017; Gloor, 2006), in some synergic groups a phenomenon of rotating leadership was identified: the best positioned took the leadership and did not hesitate to pass it on if another member could do better, or to stop it when there was no more need. This defines a form of leadership taken by turns and involving accepting the influence of others.

In the same way, responsibility is not so much distributed and limited to a role as reciprocal. It is both individual and collective and covers everything that concerns the group (Pearce and Gregersen, 1991). Each team member is responsible for him/herself, for the others, the group, the dynamics, the results, and so on. Synergy is also a factor of performance, because members are aware that knowledge exchange processes are necessary, and they implement them. Indeed Hajro et al. (2017) showed the link between knowledge exchange and team effectiveness.

All studies conclude that synergic dynamics are the key to success. Even when the results demonstrated the role of transformational leadership, team-building emerged as a mediating factor and a condition of project success (Aga et al., 2016). For all these reasons, the performance of workgroups is characterized by their members’ search for a synergy (Batson et al., 2008; Hu and Liden, 2015). Various studies have shown that synergic groups are more effective (Mathieu et al., 2000; Mathieu et al., 2008). The search for synergy is never-ending and needs a permanent regulation of the group dynamics because, among other things, synergy wavers between juxtaposition and the fusion of individuals. Indeed, for Sartre (1960), groups are “totalization in progress”. In the same way, synergy is a state always “to be achieved”. From this perspective, the process of team-building has two first stages – 1) the secondary group and 2) the fusional group – and a final stage – the synergic group.

TABLE 1

Proposal for a typology of work teams

Modeling the Process Towards Synergy

Studies on the process towards synergic group dynamics have shown that conflicts are necessary for team-building (Anzieu and Martin, 1982; Behfar et al., 2008; De Dreu and Weingart, 2003; Jehn, 1995; Jehn and Mannix, 2001). They represent a useful stage in transforming the group dynamics from fusion to synergy. Indeed, the cohesion of a fusional group is an illusion. The return to the reality of the work with the injunction to reach the professional objectives and the realization that the group’s omnipotence is a danger both inevitably lead to disagreements.

Then a new stage emerges between fusion and synergy (Figure 1). This is a return to the secondary group dynamics with a lack of group cohesion and the assertion of the individual points of view, but there is a major difference from the preliminary group in which the members were in competition. After the fusion stage, the fragmentation of the workgroup is expressed in the emergence of conflicts. Competition and conflict have been distinguished by several studies (Schmidt and Kochan, 1972; Forsyth, 2017). In competition, the goal of the group’s work is common, and each member tries to reach it alone before anyone else or better than the others. In conflict, the justification of the collective activity and the possibility of accomplishing it are questioned by the group’s members, who become aware of their differences and the extent of their divergence. In this form of fragmentation dynamics, all the pretexts for quarreling are used, and the conflict is permanent for multiple reasons. This kind of secondary group corresponds to what Brett et al. (2006) call a “feuding team”.

Now a new stage has emerged between fusion and synergy: conflict and the return to the secondary group dynamics. Some workgroups are unable to emerge from conflict and remain stuck in this step. If the workgroup succeeds in going beyond the ordeal of conflict, it can implement a new dynamic which reconciles the existence of every member’s differences and a coherent whole. For Simmel (1964, p. 14), “conflict is designed to resolve divergent dualisms”. It is an important vehicle for social regulation (Pastor and Bréard, 2007). The double experience of both fusion and secondary group dynamics makes every member know that regulation is necessary to avoid two pitfalls: omnipotence or fragmentation.

The Specific Problem of Multicultural Workgroups

The term “multicultural teams” designates a form of workgroup made up of people from different countries brought together to manage a professional project. Is their specific heterogeneous composition an obstacle to working together and succeeding? More precisely, does the multiplicity of nationalities block the workgroup in the secondary stage? What kind of difference among group members is involved? The notion of national cultural differences has been extensively covered since the founding works of Hofstede (2003) in the 1980s. Several studies have attempted to classify national cultures according to different dimensions (Schwartz, 1999; House et al., 2004; Moalla, 2016) and to propose an objective measure of their level of differentiation, called cultural distance. In this study, the notion of cultural distance is investigated through the individual perceptions. The problem of the incidence of multiculturality on the workgroup dynamics is addressed through the question of the impact of the teams’ composition on the representation of the collective as heterogeneous or homogeneous. It was possible to define the group’s heterogeneity as strong cultural distances among its members. However, two arguments lead us to adopt another approach. First, some authors, such as Mayrhofer and Roth (2007), have shown that cultural distances can be less explanatory than the nature of cultural specificities. Secondly, the cultural distance conception aims to establish some universal norms to evaluate cultures and practices. It obscures their permanent evolutions and the role of context (Adler, 1994; Pichault and Nizet, 2013). We consider that multiculturality defines the objective composition of the workgroup, but that cultural heterogeneity depends on the subjective perception of its members’ characteristics in a specific situation.

Some studies conclude that certain individual characteristics can potentially affect the virtuous group processes (Brandstaetter and Farthofer, 1997). Cultural differences are considered one of them (Watson et al., 1998). According to these studies, cultural heterogeneity hinders the group dynamics, impedes their effectiveness (Chevrier, 2004, Haas and Nüesch, 2012) and produces, in the short term at least, a low level of satisfaction (Milliken and Martins, 1996). Brett et al. (2006) identified four barriers inherent to cultural differences and leading the workgroup into a stalemate: using direct versus indirect communication; trouble with accent and fluency in the team’s dominant language; different attitudes towards hierarchy; conflicting decision-making norms. Relationships can suffer, or some members can be underestimated. In the same way, and even if they found that people worldwide share some basic beliefs about the leader’s qualities (moral, inspirational, visionary, team-oriented, etc.), House et al. (2004), in support of the results of the Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE) research project, explained that the conception of leadership is not common to all cultures. For example, individuals who lived in cultures marked by hierarchical power structures and greater levels of elitism were more tolerant of self-centered leaders who were status-conscious and formalistic. According to the GLOBE results, not everyone in a multicultural workgroup will values all forms of leadership similarly (Dorfman et al., 2004). Barmeyer (2004) found representative and significant differences of learning styles between French, German and Quebec students too, and concluded on the difficulties in interacting they can generate and the need to take them in account in cross-cultural training. In contrast, for other authors, multiculturalism brings innovation into firms (Johansson, 2001), and multicultural teams are better able to solve problems and achieve group work (Ely and Thomas, 2001; Barmeyer and Franklin, 2016). The relevance of our research question is confirmed: How can a multicultural workgroup meet the challenge of individual cultural differences and manage to become a team and achieve synergy?

FIGURE 1

Modeling of the four steps towards synergy

This article highlights that the conception of heterogeneity is not an initial theoretical viewpoint but depends on group dynamics. The concept of heterogeneity is defined here as referring to perceived differences between individuals (Williams and O’Reilly, 1998). It may concern “any possible dimension of differentiation” (Knippenberg and Schippers, 2007, p. 517). Based on the typology of diversity of Harrison and Klein (2007), two perceptions can be identified. The first considers differences in culture as a negative factor with a conception of heterogeneity as separation or disparity. For the second perception, multiculturality is a source of complementarities and new resources (Barmeyer and Franklin, 2016), with a conception of heterogeneity as variety.

In this study, the problem of heterogeneity/homogeneity is dealt with at the interactional level of group dynamics. It should be distinguished from the dialectic of divergence/convergence. Some studies have shown that both divergence and convergence are necessary for a virtuous exchange process (Cramton and Hinds, 2014; Maznevski and Chudoba, 2000; Stahl et al., 2010). The divergence of points of view is a condition, for example, of the production of knowledge or the evaluation of decisions.

Research Design: A Study of Six Multicultural Workgroups

To answer our research question, we resorted to non-participant observation of six teams of six to eight university students. The case-study method appears to us to be the most relevant to identify workgroup dynamics. According to Miles and Huberman (2003), this method allows the development of new conceptualizing drawn from detailed descriptions of phenomena. The aim is to capture all the dimensions of the complexity of the situation, and the case-study favors this (Giroux and Tremblay, 2002; Barmeyer and Franklin, 2016). Finally, the construction of a professional collective in an international context is a contemporary organizational concern. This research approach, by definition, processes conjointly the phenomena and the contexts in which they emerge (Yin, 1994).

The students were all executives studying in France for a master’s degree in management through continuing education. The six groups were selected among the whole population of a larger study on team dynamics because they were all made up only of members of different cultures. The groups’ composition was intentionally heterogeneous regarding the criteria of sex, age and nationality. This was a choice of the trainers and forced on the students. The project to be prepared and its deadline were the same for each group.

For six months, we performed a comparative longitudinal study to identify each team’s process from the project’s launch to its completion. In this research, we consider that reality does not exist independently of the perception that people have of it (Grix, 2004). The researcher’s goal is “to grasp what is significant for the actors” using mainly his/her resources of empathy (Giordano, 2003, p. 20). The methodology aims “first and foremost to understand meaning rather than frequency and to grasp how meaning is constructed within and by interactions, practices and discourses” (Allard-Poesi and Perret, 2014, p. 17). The validity of such studies (Denzin, 1984) emerges from intersubjectivity. It is considered to be attained when researchers have performed a triangulation of their data by collection through various sources or confrontation of different interpretations. In this study, triangulation was provided by three sources of data. First, the contents were collected through 41 non-directive interviews of 30 to 45 minutes, and 14 observed meetings lasting one to three hours (Table 2). They were all recorded and complemented by a case report form. All the groups wrote a charter at the beginning of their activity. This was an exercise requested by the trainers to define their shared values. The charters constituted an additional source of data. The secondary data were complemented by gathering all the information available on the workgroups, supplied from the trainers (evaluations, group papers, group presentation materials).

TABLE 2

The six groups in the study

A content analysis with a coding protocol was carried out in two phases. The first one was done manually by strata of reading (Bardin, 1983) and distribution of extracts of utterances collected by interviews, into two types of categories: a) based on the literature (deduction) and b) emerging from the thematic content analysis with deeper analysis of the verbatims and the emergence of new classifying criteria (induction). In this first phase, the main structure of our coding grid was built (Figure 2). In the second phase, we used the software NVivo 11 and carried out an analysis of all the contents: 1) collected by interview and during the meetings; 2) complemented with the case report forms and various documents. Our unit of analysis was the paragraph of meaning. We then made an analysis by case (intra-case) and cross-compared the results (inter-case).

Results: A Difficult Process Towards Synergy Independently of Multiculturality

In this part, only the findings from the inter-case analysis are presented. The results confirm the pertinence of our modeling of group dynamics to make comprehensible the process towards synergy. Although it was not the purpose of the research, our results provide additional evidence that teams are more successful in a synergic state than in a secondary or fusional state. They better reach their goals, are more creative in their regulating modes and produce more innovative proposals. Another finding is that the perception of the group as heterogeneous/homogeneous depends on the group dynamics. Principally, the analysis contributed to enhance the modeling of group dynamics towards synergy. Our findings show that the process consists in shifting from toleration to tolerance and from particular interests to common interests.

Analyzing of the Stages of Team-Building Towards Synergy

First, we carried out an intra-case analysis. Group A had medium/good results (13/20) with mediocre contributions except one excellent one, which was clearly claimed by one group member: “On my part I could have got 18/20” (Group A, Chinese, woman, age 37). The distribution of tasks was made on a “first come, first served” basis: the most responsive got the easiest or the most interesting: “My father called me and by the time I answered, I had no more choice. I understand: this thing is unfeasible” (Group A, Tunisian, man, age 31). Group members did not share their information or help each other. The rare meetings served to juxtapose the individual work in a single document.

Group B had medium results (12/20). The name “le ciel est bleu” was quickly given to the workgroup, who decided from the first days of its constitution to “do everything together without having to talk about it” (Group B, Russian, woman, age 37). The members became inseparable: “we do not leave even for eating and soon for sleeping” (Group B, Algerian, man, age 39). A month before the deadline, the group exploded: “The day before, everyone was enthusiastic and bing, the big bang” (Group B, French, man, age 37). There were many reproaches: “Nothing has been done yet”; “I spend more time with you than with my family”; “I am demanding and organized, and this way of working does not suit me at all”; “I can’t stand your childishness any more: I am here to work not to play” (Group B, interaction, observed meeting).

Group C had the best results (16/20). After two weeks of “cockfighting because everybody wanted to be the leader and nobody the follower” (Group C, Tunisian, woman, age 42), the workgroup decided to eat together during a meeting: “I don’t know who had the idea, but it was unanimously welcomed” (Group C, Moroccan, man, age 38); “something happened… the birth of ‘the big eight’… we were all talking at the same time and decisions were taken without discussion… we applauded” (Group C, Chinese, woman, age 34). Then, the members of group C realized that nobody was taking care of important parts of the project and blamed each other: “The gaps came out. Who spoke first? Me? If it was not me, I was ready. We had all noticed that a lot of things were wrong, and we did them… but the ambiance was so good… we wanted to avoid spoiling it” (Group C, Romanian, man, age 45). Many disagreements were expressed, and the members of Group C decided to stop the meetings and to work individually: “It was too bad, and I was worried that this would jeopardize the project and my diploma. That’s why I took the initiative to send an email to the group, probably too long. I was arguing about what to decide collectively and I was proposing different ways to work together” (Group C, French, man, age 41). After an email exchange, Group C resumed meetings and decided to speak about its difficulties and solutions to overcome them: “Group work is not [self-]evident. We each have our own idea of what to do and how to do it. P. is right: we must just explain rather than fighting. I may be right, and I may be wrong, or I may not have understood. The same for others. I think that it is by mixing all our brains that we’ll avoid misleading us and even that we can make a success” (Group C, Romanian, age 45).

FIGURE 2

Extracts from the classifying criteria grid used for the content analysis

Group D, named “Chary & Co.”, had good results (14/20). The workgroup moved relatively quickly from internal competition among the group members to external competition with the other groups. The unifying event was the initial difficulty of understanding some of the documents provided by the trainers and the conviction that: “In the other groups, they had finished the stage of reading the doc for a long time” (Group D, Chinese, man, age 36). To clarify several points, two members (Group D, Belgian, man, age 39; Tunisian, man, age 31) contacted a trainer who found that some data was missing and provided it with a request to transmit it to all the workgroups. Group D failed to pass the missing data on to the other groups: “We did not really talk about it, but we all agreed” (Group D, Senegalese, man, age 34). The day after, the trainer sent an email to all the workgroups, which weren’t penalized: “It was like a time bomb. Several weeks later, F. said he found unbearable that we didn’t transmit the missing data. I said I was not especially proud of it either, and the blame game started. Nobody was responsible, and everyone was offended” (Group D, French, man, age 32). The workgroup continued to meet laboriously: “Exhausting! Not one listened to others. The project was going in all directions. Luckily, someone said: we’re going right into the wall, guys. It was macho but this time I let go. A. answered: Sure, and not only the guys, the girl also” (Group D, Algerian, woman, age 33). Then the members’ contributions were mutually recognized as complementary and as “an inspiration to progress” (Group D, Chinese, man, age 36). The workgroup became aware of its strengths and weaknesses: “It’s like a good meal prepared with friends, nobody does the dishes and me neither. That’s our principal problem” (Group D, Belgian, man, age 39).

Group E, the “coeur vaillants”, had bad results (09/20) and did not understand why: “What does that mean: irrelevant? For who, irrelevant?” (Group E, Moroccan, man, age 33). They did not follow instructions and finished their work late: “Our team worked perfectly. We had no conflict. The decisions have always been consensual, which is a feat for a group of eight people with six nationalities and a range of 30 to 48 years old” (Group E, Russian, man, age 37).

Group F got just the “pass mark” (10/20). Its members divided the work to be done during a single group meeting, and then worked exclusively individually: “No need to waste our time” (Group F, French, man, age 46).

The four stages of group dynamics emerged from the data. The dynamics specific to each workgroup were distinguished and positioned (Table 3). Only two teams (C and D) reached the synergic state. Their results were clearly better than those of the others. Group B remained stuck in the third stage, that of conflict and the return to secondary dynamics. Group E worked in fusion until the deadline of the project. Two workgroups (A and F) did not get beyond the preliminary state and the secondary dynamics.

TABLE 3

Dynamics and final states of the six workgroups studied

Highlighting of the Decision Processes Faced with Differences in Points of View

In the six workgroups including secondary states, the emergence of consensus was observed. For Group F, the only but very important consensus was, during the first and unique meeting, the unanimous decision not to meet any more. Paradoxically, this team kept the conviction that no group is able to share the same decision. Its members were convinced they were the most efficient and that teamwork is unrealistic, “a utopia for academics” (Group F, Tunisian, woman, age 38). In the other secondary groups, consensus was only functional and concerned the minimal running processes. For example, they all agreed to make decisions by majority vote. They did not even try to reach a consensus on the content of the decision, but they agreed to adopt it when there was a majority: “They are wrong. […] They head straight for disaster […] That’s the game […] I have to accept the collective decision” (Group A, Moroccan, man, age 29). In the fusional group, the consensus on the content was permanent but illusory: “That’s fantastic. Without talking, we all think the same thing in the same way. I didn’t choose my group but, as luck would have it, we always agree” (Group E, Senegalese, man, age 42). In the synergic groups, members looked for consensus on the content but wanted a real consensus that resulted from discussion. They knew how difficult it is to obtain this. They were able to abandon unanimity for urgent or minor decisions. Group C tried new processes of decision when there was a lack of consensus on the content according to the situation: on the toss of a coin, delegating to the most expert, by secret ballot, and so on. Group D tended to postpone decisions which were not totally consensual. The team explored the reasons for the disagreements and repeatedly decided to complement its data to clarify the different points of view.

Emergence of Tensions from a Perceived Heterogeneity Not Stemming from Multiculturality

Except for the fusional group, team-building is perceived by the members as “a very difficult challenge” (Group F, Chinese, woman, age 34). They are confronted with a twofold conflictual tension with two components: the conflictual tension of similarities/differences brought about by the perceived heterogeneity/homogeneity in the situation, and the conflictual tension of inclusion/exclusion, which defines the relation to the conflict. The two components are interrelated and evolve with the group dynamics (Table 4).

It emerges from the analysis of our findings that nationality is one difference among others. For most of the workgroups, this characteristic of the members was not the principal difference indicated. In three groups (A, E, F), it was mentioned neither during the interview nor in the meetings that were observed. All the participants stated that individual differences were an obstacle to working together at least in the first stage of team-building. But for the three groups which were stuck in secondary dynamics, the incompatibilities came from initial education, level of diploma, or nature and length of professional experience. If these multicultural groups got entangled in divergence, it was not their cultures that made their members diverge.

In Group B, the cultural difference only appeared in situations of conflict during the last meeting of the group, which marked its explosion: “For a Senegalese, you are very aggressive” (Group B, French, woman, age 36); “Just because you are Russian you don’t have to be dishonest” (Group B, Tunisian, man, age 42). The differences between the single persons and the married persons or parents were more problematic in all the workgroups. The former adopted the student lifestyle while the latter wanted to keep their professional and adult habits. This differentiation between ways of life does not concern nationality but the context and the work. The contribution of our study is to show that the perception of the workgroup as heterogeneous or homogeneous depends on the group dynamics and not on objective characteristics. The emergence of multiculturality as a source of conflicts is the indicator of a specific stage of team-building: the phase of conflicts, when each member looks for confrontation and asserts his/her differences.

The Quest For Synergy as a Common Will for tolerance and Focus on Common Interests

In secondary or fusional dynamics, individual differences were perceived as an inescapable obstacle or a threat to unity. Only the teammates in synergic dynamics (C, D) considered that differences can be a resource for achieving the collective project. To reach synergy, the workgroups in the study had to transcend the lack of understanding which results from their culture, but also from their initial careers, education and all their social conditioning. The content analysis showed that this move towards synergy corresponds to a change in self-conception, in the conception of the other, and the conception of relations with the other. To clarify what made the difference between the two synergic workgroups and the four others, a return to the literature was necessary. In Groups C and D, a high-level process of learning or “high learning” as defined by Foldy (2004) could be identified. Their members discovered that they could grow and progress in their exchanges with the others. They managed to confront their negative attribution to a cultural belonging and their hampering limiting beliefs. As the verbatims show (Table 5), they spoke about the discomfort which results from the experience of their individual differences in the secondary stages, after the illusion of complete similarity during the fusional stage. The synergic groups differed from the other four groups which got stuck in “low learning” according to Foldy’s definition (2004) and considered these discussions to be taboos offering no possible contribution.

TABLE 4

The twofold conflictual tension of team-building and shared perceived heterogeneity

The goal of this study is to clarify these dynamics by analyzing more deeply the two workgroups in which they appeared (Table 5). A change of approach between the secondary and fusional stages and the synergy was identified. The distinction between “tolerance” and “toleration” helped us to analyze our findings. According to the philosopher Bernard Crick (1971), toleration is a matter of values and ethics and consists in embracing things one does not agree with. Toleration supposes a limit to what can be accepted. Toleration and intolerance are similar in the relationship with others who disturb and are tolerated up to a certain point. Toleration indicates that intolerance can happen. Tolerance “rather means lack of prejudice, open-mindedness, and rejection of any dogmatism” (Lacorne, 2016, p. 15). Regarding the verbatims (Table 5), toleration characterizes the relationship to others in fusional or secondary stages: “A lot is to be suffered in group work with others” (Group C, competition-secondary stage, Chinese, woman, age 36); “It’s normal for the group to close on itself. Interacting between us is easier and safer” (Group D, fusion, Senegalese, man, age 34). Statements of tolerance only appear in the synergic stage: “I’m lucky to have the opportunity to interact with people from different backgrounds” (Group C, synergy, French, woman, age 31); “This guy I could no more stand him, and you know, now, it’s crazy how much I learned with him” (Group D, synergy, Belgian, man, age 36).

Another shift emerged from our results: it is in the orientation of the concerns. The members of Groups C and D used the term “common” associated with the words “good” or “interest” but without a clear definition of what the notion referred to: “Our common interest is what we are doing together, and which unites us. It is good for each of us. It’s good because that’s the reason why we are going to make it. It’s good also for Chary & Co.… I mean: for what we are…. Good for future promotions… a message to say: yes, you can! [laughter]…It’s not only the scores or to complete our training… not only” (Group D, French, man, age 32). The notion of “common interest” which Group C and D members used seems to be close to the Commons as defined by Ostrom (1990). In the synergic stage of Groups C and D, every member uses the group’s resources, which are not depleted but enhanced. What they called “common interest” is interrelated to the notion of the common good defined by Sison and Fontrodona (2012, p. 23) for a firm: “first and foremost a network of activities, a host of practices; it is work in common”.

TABLE 5

Workgroup dynamics towards synergy

Groups C and D moved from the conflict stage towards synergy, because they realized that the project was at risk (Figure 3). Their shared interest was to achieve it. A common concern appeared and replaced the personal concerns. Then the members of Groups C and D recognized the contributions of the other members and toleration became tolerance: “We were fighting, and H. said ‘I quit. That’s dead’. And S. said: ‘No. If that’s dead, I lost my job’. It was an electroshock. The deadline, the stakes. We made a follow-up review. Everyone began to indicate what he/she could do. And instead of denigrating them or blaming them for their defects, I thought about their capacities and tried to reinforce their contributions” (Group C, Canadian, man, age 32). Regarding the results of the study, the move towards synergy is a move from toleration to tolerance and from personal interests to “common interest”. Tolerance and common interest converge with synergy, and vice versa.

A Necessary Permanent Regulation and The Ineffectiveness of Charters

Our results show that the synergic groups permanently oscillated between a secondary trend and a fusional trend. One of the regulations of the synergic dynamic was to bring the group back to synergy. The orientation on particular interests or the slide from tolerance to toleration are the indicators which alert the group’s members to the fact that regulation is necessary. Synergy is never acquired once and for all. It is a state always to be aimed at.

By contrast, the charters did not help team-building. At the time of their composition, the workgroups were eager to define a charter. The goal was to identify the values that they shared. “Respect for others” or “Listening” were terms posted by the six groups. Only four groups mentioned “Tolerance” in their charter (A, B, C, F) and two of them ended the project in the first state with a secondary dynamic. During the interviews, some members explained that the problem was due to the level of the group’s heterogeneity: “We can’t agree with each other. The only solution was to coexist and finish the work the best way we can” (Group A, Canadian, woman, age 41). Their definition of “tolerance” corresponded to “toleration”. They thought that a minimum of discrimination at work is inescapable in order to constitute a homogeneous team able to perform: “The trainers did exactly the contrary of what a reasonable manager would do: they mixed us. Of course, we weren’t in the right working conditions to succeed” (Group F, Romanian, man, age 38). Some students explained that they are tolerant, but with people so different from them, “meetings are a challenge for the nerves” (Group F, Moroccan, man, age 45). During the last stage of Group B’s dynamics, a violent argument broke out, more specifically between two members who accused each other of betraying the group’s charter: “How could you applaud when we wrote ‘tolerance’ in the charter and then be so aggressive because I need to read all the documents before we make a decision?” “It’s the limit! You are incapable of accepting any other way of working than yours and you lecture me about toleration?” (Group B, interaction, observed meeting). Regarding the synergic groups, Group C’s dynamics were not easier than Group D’s. Our results tend to show that charters are not useful and can even make conflicts more bitter in the third stage of team-building.

Discussion: The Question of Multiculturality as Perceived Heterogeneity

In our study, a team’s success is independent of its multicultural composition. The designation of the workshop as heterogeneous or homogeneous is a matter of perception. It varies according to the stages of group dynamics. The finding that cultural differences are not obstacles in themselves for workgroups is one of our principal contributions. It should not hide the major difficulty which collective work represents in an international context or in all situations. In this part, we discuss the scope and the limits of the results obtained by the study of the six workgroups in an executive training program at the university.

FIGURE 3

The process from conflict towards synergy (typical verbatims - interviews - Groups C and D)

While some recent studies show that previous experience of others’ differences facilitates multicultural teams’ activities, others have argued that, in an increasingly multicultural and global society, no such universal principle can exist (Keys, 2006). Therefore, Holtbrügge and Engelhard (2016, 2017) tested the impact of bicultural individuals on team performance. People who have been deeply socialized and operate fluidly within and between two distinct cultural meaning systems better manage the success of a multicultural team. This observation suggests that multiculturalism is easier when people are bicultural and consequently that homogeneous workgroups are preferable. It does not solve the question of work with diverse people. By contrast, this argument also indicates a limit of our study: our population was composed of students who were studying in a foreign country or, for the French ones, were attending an international program. Did they not share the same multicultural mindset? Regarding culture, were the teams objectively heterogeneous? In this light, it would not be surprising to find that the main perceived differences concerned other characteristics.

However, in accordance with approaches different from ours (Hofstede, 2003; Schwartz, 1999; House et al., 2004), the cultural distances among the members of each workgroup were important. For example, the composition of Group C was: 2 French, 1 Canadian, 2 Chinese, 1 Moroccan, 1 Romanian and 1 Tunisian. Yet the findings of the GLOBE research program showed that Chinese people have “a strong tendency towards formalizing their interactions with others, […] being orderly, […], formalizing policies and procedures, establishing and following rules […]”, in contrast to people from Eastern European countries who are “more informal” (House et al., 2004, p. 6). In that workgroup, more similarities or fewer differences were not observed in the two pairs of members with the same nationality than among the other members.

Furthermore, the report form included a specific research question on the possible emergence of a dominant group. No subgroup was established either in Group C or in any of the other groups. Millikan and Martins (1996) underline that the absence of dominant cultural groups facilitates the management of multiculturality. It could be deduced from this that the composition of groups with high cultural heterogeneity is a factor of success. Above all, the difficulty in collective work is not so much heterogeneity as social domination, translated by the hierarchical organization of the differences. Dijk and Engen (2013) consider that competence/status emerge in workgroups when the members differ in their characteristics. Then the status differences lead to the formation of an informal social order. In the groups studied, it was the fear of the attribution of a status to a difference and the rejection of the associated social order that prevented the teams from going beyond the stage of the secondary group and adopting an attitude of tolerance.

The two previous statements of the conditions favoring success in which the workgroups were placed bring us to another limit of our study. Three arguments can be added in this regard: 1) the number of members is considered a favorable condition for team-building (Wheelan, 2006); 2) the context was a win-win situation. The distribution of rewards among the members was the same and the collective results served their personal interests. Rose (2002) underlines that this is not always the case in firms; 3) The executives were in a training situation without hierarchy and so without expectations of the formal leader. Their level of English or French was similar in each group and was not a difficulty. At least two of the four barriers to effective teamwork inherent to cultural differences (Brett et al., 2006) were missing.

Nevertheless, the members of the six workgroups in the study had to face difficulties due to their differences. The findings demonstrate that synergy is particularly difficult to reach. They show that the move from the secondary stage to the synergic stage is above all a recognition of the other as a different person with his/her own characteristics. This is true for multicultural characteristics, as several researchers have shown (Dupriez and Vanderlinden, 2017). It is true in general for all kinds of differences. This is especially as the obstacles identified in the multicultural teams (leadership conception, decision process, communication mode, etc.) are found in teams with the same nationality. As Barmeyer (2004, p.578) explained for learning styles, “every person has his or her own individual way of gathering and processing information, which means ways of learning and solving problems in day-to-day situations”. In this sense, our results converge with the assertion of Brett et al. (2006, p.89): “The challenge in managing multicultural teams effectively is to recognize underlying cultural causes of conflict, and to intervene in ways that both get the team back on track and empower its members to deal with future challenges themselves”. But se also find that conflict is a stage in the group dynamics and the underlying cause is not always difference of nationalities. It may be difference of education or experience. So, regarding our results, it can be asserted that the challenge in managing workgroups is to recognize the differences among their members and to promote self-regulation.

TABLE 6

Permanent regulation of the synergic dynamic (Verbatims – observed meeting – Groups C and D)

Conclusion

In conclusion, how can multicultural workgroups achieve synergy and become teams? The group dynamics of six workgroups in an executive training program at the university were studied to answer this research question. The findings show that the challenge for heterogeneous teams is to move from toleration to tolerance, and from particular to common interests. So, within the limits of the study, their first contribution concerns theories on workgroup dynamics and the definition of synergy and self-regulation (Cooley, 2002; Cummings, 1978; De Dreu, 2006; Ellemers, 2012; Higgins and May, 2016; Homans, 2017). We have deepened and complemented them and consolidated our model of the four stages of group dynamics: competition stage of secondary groups, fusional stage, conflict stage of secondary groups, and synergic stage. Two associated contributions can be highlighted: one is methodological, with the confirmation of the pertinence of case studies in the multicultural research field (Giroux and Tremblay, 2002; Barmeyer and Franklin, 2016); the other is practical, with the recommendation to implement team management by projects. Indeed, the will to make a success of the project to which they adhere seems to be crucial for overcoming the conflict stage and focusing on common interests. Conversely, the initial values posted in the charters are not determining factors for synergy. In the third stage of team-building, some conflicts in the name of tolerance were even observed.

Is the specific heterogeneous composition of multicultural teams an obstacle to working together and succeeding? Although the discussion shows that they were placed in favorable conditions to work in groups, only two workgroups out of six managed to reach the synergic stage. However, regarding our results, nationality difference was not perceived as a factor of heterogeneity by the group members in the study. Their representation of their group’s heterogeneity versus homogeneity depends on other characteristics and varies throughout the process of group dynamics. The findings of the study suggest two assertions which contribute to enrich two debates: one on the role of group composition in a team’s success (Bell et al., 2011; Harrisson et al., 2002); the other on the approach to multiculturality as a constraint or a resource (Harrison and Klein, 2007; Barmeyer and Franklin, 2016). First, the nature and the level of heterogeneity or homogeneity of the group appear not only as non-objective but as a shared perception in each workgroup, interrelated with their stage of group dynamics. In this light, all the teams can be considered potentially heterogeneous or homogeneous, and our findings are not specific to multicultural teams but concern every workgroup, whatever its composition. Secondly, divergence is not a negative effect of heterogeneity, and convergence is not the team management objective. They are two processes where the identification of coexistence in the workgroups studied contributed to defining the synergic dynamics. The dual approach of Barmeyer (2007, p.17), opposing convergence (“differences will disappear”) and divergence (“differences persist or increase”) as the only two possible conceptions of multiculturality, corresponds to the two stages of fusional and secondary group dynamics respectively. As regards the final modeling of synergy, it is proposed to add a third way. This considers convergence and divergence not as alternatives, but as potential virtuous conjoint processes with the perception of similarities and differences as necessities or resources for working together. So, for multicultural team management, the question is: how can divergence and convergence both emerge in the workgroup dynamics in order to achieve synergy? The challenge is to move from a shared conception either of heterogeneity as separation or the transitory illusion of homogeneity to a synergic conception. This conception consists in moving beyond the alternatives of convergence and divergence and adopting a realistic and positive point of view. It implies recognizing group members’ differences and considering that their underlying causes result not only from cultural shaping (Brett et al., 2006) but from all the social conditionings, of which membership in a workgroup is part. This defines the synergic self-regulation, which is constantly renewed by a mutual redefining of similarity and difference.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

The first findings of this study were presented at the international conference “Responsible Organizations in the Global Context,” held on 15 to 16 June 2017 at Georgetown University (Washington DC) in partnership with the University of Versailles St-Quentin-en-Yvelines. I am grateful to the reviewers of the scientific committee and the chairman and participants of Workshop 9, “Culture, Diversity and Responsibility” for their comments and questions. I also thank the three reviewers of International Management, whose pertinent and precise remarks helped to improve this article; and Richard Nice for his linguistic revision.

Biographical note

Martine Brasseur is Professor of Universities at Paris Descartes University / University of Paris (France), where she has created a specialty of Master Management, Ethics and Organizations. She is attached to the Center for Studies in Business and Management Law (CEDAG), where she is responsible for the Management, Ethics, Innovation and Society axis. She is editor-in-chief of the academic journal RIMHE (Management and Human Enterprise). Co-founder and Vice-President of the academic association ARIMHE, she has set up an annual research grant to support research projects on humanistic management of companies.

Bibliography

- Adler, Nancy J. (1994), Comportement organisationnel: une approche multiculturelle, 1ère édition 1986, Ottawa: Reynald Goulet.

- Aga, D. Assefa; Noorderhaven, Niels; Vallejo, Bertha (2016), “Transformational leadership and project success: The mediating role of team-building,” International Journal of Project Management, Vol. 34, N° 5, p. 806-818.

- Allard-Poesi, Florence; Perret, Véronique (2014), “Fondements épistémologiques de la recherche,” in Thietart, R-A. (Ed.), Méthodes de recherche en management, 4ème édition, Paris: Dunod, 656 p., p. 14-46.

- Anzieu, Didier; Martin, Jacques-Yves (1982), La dynamique des groupes restreints, Paris : PUF.

- Ashmore, Richard D.; Deaux, Kay; McLaughlin-Volpe, Tracy (2004), “An organizing framework for collective identity: articulation and significance of multidimensionality,” Psychological bulletin, Vol. 130, N° 1, p. 80-114.

- Ayub, Nailah; Jehn, Karen (2014), “When diversity helps performance: Effects of diversity on conflict and performance in workgroups,” International Journal of Conflict Management, Vol. 25, N° 2, p. 189-212.

- Babcock, Philip; Bedard, Kelly; Charness, Gary; Hartman, John; Royer, Healther (2015), “Letting down the team: Evidence of social effects of team incentives,” Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 13, N° 5, p. 841–870.

- Bales, Robert F. (1951), Interaction Process Analysis: A Method for the Study of Small Groups, Cambridge: Addison-Wesley - https://archive.org/stream/interactionproce00bale#page/32/mode/

- Bardin, Laurence (1982), L’analyse de contenu, 1ère édition 1977, Paris: PUF, Coll. le psychologue.

- Barmeyer, Christoph I. (2004), “Learning styles and their impact on cross-cultural training: An international comparison in France, Germany and Quebec,” International Journal of Intercultural Relations, Vol. 28, N° 6, p. 577-594.

- Barmeyer, Christoph I. (2007), Management interculturel et styles d’apprentissage: étudiants et dirigeants en France, en Allemagne et au Québec, Laval: Presses Université Laval, 277 p.

- Barmayer, Christoph I.; Franklin, Peter (2016), “Introduction. From otherness to Synergy. An alternative approach to Intercultural Management,” in Barmeyer C., Franklin P. (Eds), Intercultural Management. A Case-Based Approach to Achieving Complementary and Synergy, New York: Macmillan International Higher Education, 360 p., p. 1-12.

- Batson, C. Daniel; Ahmad, Nadia; Powell, Adam A.; Stocks, Eric L. (2008), “Prosocial motivation,” in J.Y. Shah, W.L. Gardner (Ed.), Handbook of Motivation Science, New York: Guilford Press, p. 135-149.

- Behfar, Kristin J.; Peterson, Randall S.; Mannix, Elisabeth A.; Trochim, William M.K. (2008), “The critical role of conflict resolution in teams: a close look at the links between conflict type, conflict management strategies, and team outcomes,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 93, N° 1, p. 170-188.

- Belbin, R. Meredith (2010), Team Roles at Work, 1st edition 1993, New York: Routledge.

- Belbin, R. Meredith (2012), Beyond the Team, New York: Routledge.

- Bell, Suzanne T., Villado, Anton J., Lukasik, Marc A., Belau Larisa, Briggs Andrea L. (2011), “Getting Specific about Diversity Demographic Variable and Team Performance Relationships: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Management, Vol. 37, N° 3, p. 709-743.

- Blanchet, Alain; Trognon, Alain, (2011), La psychologie des groupes, 2ème édition, Paris: Armand Colin, 128 p.

- Brandstaetter, Hermann; Farthofer, Alois (1997), “Personality in social influence across tasks and groups,” Small Group Research, N° 28, p. 46-163.

- Brett, Jeanne; Behfar, Kristin; Kern, Mary C. (2006), “Managing Multicultural Teams,” Harvard Business Review, p. 85-97.

- Charness, Gary; Holder, Patrick (2018), “Charity in the Laboratory: Matching, Competition, and Group Identity,” Management Science, Online Articles in Advance - https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2017.2923

- Chen, Yan; Li, Sherry X. (2009), “Group identity and social preferences,” American Economic Review, Vol. 99, N° 1, p. 431-457.

- Chevrier, Sylvie (2004), “Le management des équipes interculturelles,” Management International, Vol. 8, N° 3, p. 31-40.

- Coman, Alin; Hirst, William (2015), “Social identity and socially shared retrieval-induced forgetting: The effects of group membership,” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, Vol. 144, N° 4, p. 717-722.

- Cooley, Charles N. (2002), “Groupes primaires, nature humaine et idéal démocratique,” Revue du MAUSS, Vol. 1, N° 19, p. 97-112.

- Cramton, Catherine Durnell; Hinds, Pamela J. (2014), “An embedded model of cultural adaptation in global teams,” Organization Science, Vol. 25, N° 4, p. 1056-1081.

- Crick, Bernard (1971), “Toleration and Tolerance in Theory and Practice,” Government and Opposition, Vol. 6, N° 2, p. 143-171.

- Cummings, Thomas G. (1978), “Self-regulating work groups: A socio-technical synthesis,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 3, N° 3, p. 625-634.

- Davis, Jason P.; Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. (2011), “Rotating leadership and collaborative innovation: Recombination processes in symbiotic relationships,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 56, N° 2, p. 159-201.

- De Dreu, Carsten K.W. (2006), “Rational self-interest and other orientation in organizational behavior: A critical appraisal and extension of Meglino and Korsgaard (2004),” The Journal of Applied Psychology, N° 91, p. 1245-1252.

- De Dreu, Carsten KW, Weingart Laurie R. (2003), “Task versus relationship conflict, team performance, and team member satisfaction: a meta-analysis,” Journal of applied Psychology, Vol. 88, N° 4, p. 741-749.

- Denzin, Norman K. (1984), The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods, Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice Hall, 306 p.

- Dijkvan, Hans; Engenvan, Marloes (2013), “A status perspective on the consequences of work group diversity,” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 86, p. 223-241.

- Dorfman, Peter W.; Hanges, Paul J.; Brodbeck, Felix C. (2004), “Leadership and cultural variation: The identification of culturally endorsed leadership profiles,” in R.J. House, P.J. Hanges, M. Javidan, P.W. Dorfman, V. Gupta, Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBEStudy of 62 Societies, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 848 p, p. 669-719.

- Dupriez, Pierre; Vanderlinden, Blandine (Eds.) (2017), Au coeur de la dimension culturelle du management, Paris: Harmattan, 673 p.

- Ellemers, Naomi (2012), “The Group self,” Science, Vol. 336, N° 6083, p. 848-852.

- Ely, Robin J.; Thomas, David A. (2001), “Cultural diversity at work: the effects of diversity perspectives on work group processes and outcomes,” Administrative Science Quarterly, N° 46, p. 229-273.

- Foldy, Erica G. (2004), “Learning from Diversity: A Theoretical Exploration,” Public Administration Review, Vol. 64, N° 5, p. 529-538.

- Forsyth, Donelson R. (2017), Group dynamics, 7th edition, Boston: Cengage Learning Custom Publishing, 752 p.

- Giordano, Yvonne (2003), “Chapitre 1 - Les spécificités des recherches qualitatives,” in Y. Giordano (Ed.), Conduire un projet de recherche, une perspective qualitative, Paris: Editions EMS, Collections Management & Société, p. 11-25.

- Giroux, Sylvain; Tremblay, Ginette (2002), Méthodologie des sciences humaines: la recherche en action, Saint-Laurent, Montréal: Editions du Renouveau Pédagogique / Pearson ERPI, 300 p.

- Gloor, Peter A. (2006), Swarm Creativity: Competitive Advantage through Collaborative Innovation Networks, New York: Oxford University Press, 224 p.

- Greco, William R.; Bravo, Gregory; Parsons, John C. (1995), “The search for synergy: a critical review from a response surface perspective,” Pharmacological Reviews, Vol. 2, N° 47, p. 331-385.

- Grix, Jonathan (2004), The Foundations of Research, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 200 p.

- Groutel, Emmanuel; Carluer, Frédéric; Le Vigoureux, Fabrice (2010), “Le leadership follettien: un modèle pour demain?” Management & Avenir, Vol. 6, N° 36, p. 284-297.

- Haas, Hartmut; Nüesch, Hartmut (2012), “Are multinational teams more successful?” The International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 23, N° 15, p. 3105-3113.

- Hackman, J. Richard (2002), Leading Teams: Setting the Stage for Great Performances, Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 336 p.

- Hackman, J. Richard; Walton, Richard E. (1986), “Leading groups in organizations,” in P.S. Goodman (Ed.), Designing Effective Work Groups, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, p. 72-119.

- Hajro, Aida; Gibson, Cristina B.; Pudelko, Markus (2017), “Knowledge exchange processes in multicultural teams: linking organizational diversity climates to teams’ effectiveness,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 60, No 1, p. 345-372.

- Harrison, David A.; Klein, Katherine J. (2007), “What’s the difference? Diversity constructs as separation, variety or disparity in organizations,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 32, p. 1199-1228.

- Haslam, S. Alexander; Ellemers, Naomi (2016), “Social identification is generally a prerequisite for group success and does not preclude intragroup differentiation,” Behavioral and Brain Sciences, Vol. 39 - https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X15001387

- Higgins, E. Tory; May, Danielle (2016), “Individual Self-Regulatory Functions: It’s Not “We” Regulation, but It’s Still Social, in C. Sedikides, M.B. Brewer (Eds), Individual Self, Relational Self, Collective Self, London and New-York: Routledge, 358 p., p.47-70.

- Hofstede, Geert (2003), Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations, 1st edition 1980, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Holtbrügge, Dirk; Engelhard, Franziska (2017), “Biculturals as facilitators of multicultural team performance: an information-processing perspective,” European Journal of Cross-Cultural Competence and Management, Vol. 4, N° 3-4, p. 236-262.

- Homan, Astrid C.; Hollenbeck, John R.; Humphrey, Stephen E.; KnippenbergVan, Daan; Ilgen, Daniel R.; Kleef Van, Gerben, A. (2008), “Facing differences with an open mind: openness to experience, salience of infragroup differences, and performance of diverse work groups,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 51, N° 6, p. 1204-1222.

- Homans, George C. (2017), The Human Group, New York: Routledge, International Library of Sociology, Vol. 7.

- House, Robert J.; Hanges, Paul J.; Javidan, Mansour; Dorfman, Peter W.; Gupta, Vipin (2004), Culture, Leadership, and Organizations: The GLOBEStudy of 62 Societies, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 848 p.

- Hu, Jia; Liden, Robert C. (2015), “Making a difference in the teamwork: linking team prosocial motivation to team processes and effectiveness,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 58, N° 4, p. 1102-1127.

- Jehn, Karen A., (1995), “A Multimethod Examination of the Benefits and Detriments of Intragroup Conflict,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 40, N° 2, p. 256-283.

- Jehn, Karen A., Mannix, Elisabeth A., (2001), “The Dynamic Nature of Conflict: A Longitudinal Study of Intragroup Conflict and Group Performance,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 44, N° 2, p. 238-251.

- Johansson, Frans (2001), “Masters of the Multicultural,” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 83, N° 10, p. 18-19.

- Kaës, René (1976), L’appareil psychique groupal, Paris: Dunod.

- Karjalainen, Helena (2010), “La culture d’entreprise permet-elle de surmonter les différences interculturelles?”, Revue Française de Gestion, N° 204, p. 33-52.

- Kaufmann, Pierre (1968), Kurt Lewin. Une théorie du champ dans les sciences de l’homme, Paris: Vrin.

- Keys, Mary M. (2006), Aquinas, Aristotle and the Promise of the Common Good, New York: Cambridge University Press, 272 p.

- Kiggundu, Moses N. (1983), “Task interdependence and job design: Test of a theory,” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, N° 31, p. 145-172.

- Klein, Cameron; DiazGranados, Deborah; Salas, Eduardo; Le, Huy; Burke, C. Shawn; Lyons, Rebecca; Goodwin, Gerald F. (2009), “Does team building work?” Small Group Research, Vol. 40, N° 2, p. 181-222.

- Knippenbergvan, Daan; Schippers, Michaéla C. (2007), “Work Group Diversity,” Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 58, p. 515-541.

- Kurtzberg, Terri R.; Amabile, Teresa M. (2001), “From Guilford to creative synergy: Opening the black box of team-level creativity,” Creativity Research Journal, Vol. 13, N° 3-4, p. 285-294.

- Lacorne, Denis (2016). Les frontières de la tolérance, Paris: Gallimard, 256 p.

- Larson, J.R. (2010), In Search of Synergy in Small Group Performance, New York/London, Psychology Press, 427 p.

- Lewin, Kurt (1947), “Frontiers in Group Dynamics: Concept, Method and Reality in Social Science; Social Equilibria and Social Change,” Human Relations, N° 1, p. 5-41.

- Maisonneuve, Jean (2018), La dynamique des groups, Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, Coll. Que sais-je?, 128 p.?

- Mathieu, John; Heffner, Tonia S.; Goodwin, Gerald F.; Salas, Eduardo; Cannon-Bowers, Janis A. (2000), “The influence of shared models on team process and performance,” The Journal of Applied Psychology, N° 85, p. 273-283.

- Mathieu, John; Maynard, M. Travis; Rapp, Tammy; Gilson, Lucy (2008), “Team effectiveness 1997-2007: A review of recent advancements and a glimpse into the future,” Journal of Management, N° 34, p. 410-476.

- Mathieu, John E.; Hollenbeck, John R.; Knippenbergvan, Daan; Ilgen, Daniel R. (2017), “Century of Work Teams in the Journal of Applied Psychology,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 102, N° 3, p. 452-467.

- Mayrhofer, Ulrike; Roth, Fabrice (2007), “Culture nationale, distance culturelle et stratégies de rapprochement: une analyse du secteur financier,” Management international, Vol. 11, N° 2, p. 29-40.

- Maznevski, Martha L.; Chudoba, Katherine M. (2000), “Bridging space over time: Global virtual team dynamics and effectiveness,” Organization Science, Vol. 11, N° 5, p. 473-492.

- Meglino, Bruce M.; Korsgaard, Audrey (2004), “Considering rational self-interest as a disposition: organizational implications of other orientation,” The Journal of Applied Psychology, N° 89, p. 946-959.

- Metcalf, Henry C.; Urwick, Lindall F. (Eds.) (1940), “Dynamic administration: The collected papers of Mary Parker Follett,” in K. Thompson (Ed.) (2014), The Early Sociology of Management and Organization, New York: Harpers Bros Publishers, Volume III, 320 p.

- Miles, Matthew B.; Huberman, A. Michael (2003), Analyse des données qualitatives: recueil de nouvelles méthodes, 2ème édition, Bruxelles: De Boeck Supérieur, 626 p.

- Milliken, Frances J.; Martins, Luis L. (1996), “Searching for common threads: Understanding the multiple effects of diversity in organizational groups,” Academy of Management Review, N° 21, p. 402-433.

- Moalla, Emna (2016), “Quelle mesure pour la culture nationale? Hofstede vs Schwartz vs Globe,” Management International, N° 20 (spécial), p. 26-37.

- O’Reilly, Charles A.; Snyder, Richard C.; Boothe, Joan N. (1993), “Effects of executive team demography on organizational change,” in P.H. Huber, W.H. Glick (Eds.), Organizational Change and Redesign: Ideas and Insights for Improving Performance, New York: Oxford University Press, 464 p., p. 147-175.

- Ostrom, Elinor (1990), Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 280 p.

- Pastor, Pierre; Bréard, Richard (2007), Gestion des conflits: La communication à l’épreuve, Paris: Editions Liaisons.

- Pearce, Jone L.; Gregersen, Hal B. (1991), “Task interdependence and extrarole behavior: A test of the mediating effects of felt responsibility,” The Journal of Applied Psychology, N° 76, p. 838-844.

- Pelled, Lisa H. (1996), “Demographic diversity, conflict, and work group outcomes: An intervening process theory,” Organization Science, Vol. 7, N° 6, p. 615-631.

- Peterson, Randall S.; BehfarKristin J. (2003), “The dynamic relationship between performance feedback, trust and conflict in groups: a longitudinal study,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, N° 92, p. 102-112.

- Pichault, François; Nizet, Jean (2013), “Le management interculturel comme processus de traduction. Le cas d’une entreprise béninoise,” Management International, Vol. 17, N° 4, p. 50-57.

- Polzer, Jeffrey T.; Milton, Laurie P.; Swarm Jr, William B. (2002), “Capitalizing on Diversity: Interpersonal Congruence in Small Work Groups,” Administrative Science Quarterly, N° 47, p. 296-325.

- Rico, Ramón; De La Hera Carlos M. A.; Tabernero Carmen (2011), “Work team effectiveness, a review of research from the last decade (1999-2009),” Psychology in Spain, Vol. 15, N° 1, p. 57-79.

- Roccas, Sonia; Sagiv, Lilach; Schwartz, Shalom; Halevy, Nir; Eidelson, Roy (2008), “Toward a unifying model of identification with groups: Integrating theoretical perspectives,” Personality and Social Psychology Review, Vol. 12, N° 3, p. 280-306.

- Rose, David C. (2002), “Marginal productivity analysis in teams,” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, Vol. 48, N° 4, p. 355-363.

- Sartre, Jean-Paul (1960), Critique de la raison dialectique, Paris: Gallimard, 760 p.

- Schmidt, Stuart M.; Kochan, Thomas A. (1972), “Conflict: Toward Conceptual Clarity,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 17, N° 3, p. 359-370.

- Schwartz, Shalom H. (1999), “A theory of cultural values and some implications for work,” Applied Psychology, Vol. 48, N° 1, p. 23-47.

- Simmel, Georg (1964), Conflict and the Web of Group Affiliations, Glencoe, Illinois: The Free Press.

- Sison, Alejo J.G.; Fontrodona, Joan (2012), “The Common Good of the Firm in the Aristotelian-Thomistic Tradition,” Business Ethics Quarterly, Vol. 22, N° 2, p. 211-246.

- Spears, Russell (2016), “The Interaction Between the Individual and the Collective Self: Self-Categorization in Context, in C. Sedikides, M.B. Brewer (Eds), Individual Self, Relational Self, Collective Self, London and New-York: Routledge, 358 p., p. 171-198.

- Stahl, Günter K.; Maznevski, Martha L.; Voigt, Andreas; Jonsen, Karsten (2010), “Unraveling the effects of cultural diversity in teams: A meta-analysis of research on multicultural work groups,” Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 41, N° 4, p. 690-709.

- Tajfel, Henri (1974), “Social identity and intergroup behavior,” Social ScienceInformation, Vol. 13, N° 2, p. 65-93.

- Thévenet, Maurice; Vachette, Jean-Luc (1992), Culture et comportements, Paris: Vuibert.

- Vignat, Jean-Pierre (2012), “Le travail en synergie avec les autres soignants,” L’information psychiatrique, Vol. 88, p. 361-364.

- Watson, Warren E.; Johnson, Lynn; Merritt, Deanna (1998), “Team orientation, self-orientation, and diversity in task group: Their connection to real performance over time,” Group and Organization Management, N° 23, p. 161-188.

- Wheelan, Susan A. (2009), “Group size, group development, and group productivity,” Small Group Research, Vol. 40, N° 2, p. 247-262.

- Williams, Katherine Y.; O’Reilly, Charles (1998), “Demography and diversity in organizations: a review of 40 years of research,” Research in Organizational Behavior, N° 20, p. 77-140.

- Yin, Robert K. (1994), Case Study Research, Design and Methods, 2nd edition, Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, 171 p.

Appendices

Note biographique