Abstracts

Abstract

Economic intelligence can be defined as a system of learning (logic of knowledge) and lobbying (logic of influence), largely based on access to information and interpersonal relationships. In the West, learning and lobbying are managed simultaneously, sequentially or separately. Can these systems, however, be developed in the same ways in Far Eastern countries, where messages are generally implicit and relations are usually gregarious? In particular, does knowledge depend on influence in these countries?

Using the People’s Republic of China as an example, and based upon a survey of 353 people, the work in this article illustrates the need for adapting economic intelligence to international operations, and underlines the relevance of guanxi in building such a system in this country.

Keywords:

- Guanxi,

- economic intelligence,

- lobbying,

- implicit communication,

- interpersonal networks

Résumé

Fondée sur l’accès à l’information et les relations interpersonnelles, l’intelligence économique peut être définie comme un système de connaissance (logique de savoir) et de lobbyisme (logique d’influence). En Occident, les logiques de savoir et d’influence sont gérées de manière indépendante, synchronisée ou séquentielle. Ce système peut-il être développé dans les mêmes conditions dans des pays extrême-orientaux où les messages sont généralement implicites et les logiques relationnelles traditionnellement grégaires ? Plus précisément, la logique de savoir est-elle - dans ces pays- dépendante de la logique d’influence ?

Utilisant la République Populaire de Chine comme exemple, à partir d’une enquête menée auprès de 353 personnes, cet article illustre le besoin d’adapter l’intelligence économique aux opérations internationales et souligne la pertinence des guanxi pour construire un tel système dans ce pays.

Mots-clés :

- Guanxi,

- intelligence économique,

- lobbyisme,

- communication implicite,

- réseaux interpersonnels

Resumen

La inteligencia económica puede definirse como un sistema tanto de aprendizaje (lógica del conocimiento) como de cabildeo (lógica de influencia), que se apoya principalmente en el acceso a la información y relaciones interpersonales. En los países occidentales, estas lógicas del conocimiento y de influencia se administran de forma independiente, de manera sincronizada o secuencial. ¿Puede este sistema ser desarrollado en las mismas condiciones en los países del Lejano Oriente, donde los mensajes llevan generalmente un significado implícito y las relaciones suelen adoptar un comportamiento gregario? ¿Específicamente, cabe preguntarse si la lógica del aprendizaje depende de la lógica de influencia en esta parte oriental del mundo? A partir de una encuesta realizada en la República Popular de China con 353 personas, este artículo ilustra la necesidad de adaptar la información económica a las operaciones internacionales, y subraya la importancia de los guanxi para la elaboración de un sistema de este tipo en este país.

Palabras clave:

- Guanxi,

- inteligencia económica,

- grupos de presión,

- comunicación implícita,

- redes interpersonales humanos

Article body

Developed in Occidental countries, economic intelligence is a global approach aiming at the mastery of strategic information, as defined by Chirouze and Moinet (2006, p. 2). Despite the focus on the term economic, this practice has a wide scope of analysis and is concerned with the Political, Regulatory, Economic, Social and Technological (PREST) dimensions of organizations’ external environments. These different categories of intelligence, from Lemaire’s work (2000 and 2013), correspond to the field of research considered in this article.

To better understand what economic intelligence is about, let us turn to a presentation of its key activities.

Larivet (2009) indicates that, in France, this practice combines three managerial missions: obtaining information for better understanding and reacting to the environment (1), protecting and controlling the diffusion of information (2), and influencing certain external targets through the use of specific messages (3). This definition, which associates learning (logic of knowledge [the first two missions]) and lobbying[2] (logic of influence [the final mission]), seems particularly interesting for studying how economic intelligence could be developed from Western to Far Eastern countries.

In the West, the strategies of learning and lobbying are managed independently or dependently. Indeed, intelligence systems are based on a single type of logic, either knowledge or influence, or upon the association of the two (synchronously or sequentially). But can such a system be as effective in countries where interpersonal networks are essential for conducting business? Instead, does the logic of knowledge depend upon the logic of influence in these countries?

In the West, economic intelligence is usually based on rather explicit communication and, theoretically, more easily-available and reliable information, including macroeconomic data, market data, comparative analyses, etc. Adapting this learning activity may be necessary, because the communication style and relational logic, two essential dimensions of economic intelligence, are very different in the Occident and the Orient. Can such a system, heavily based on quantifiable information, be used in cultures characterized by implicit communication and less accessible, less reliable information?

In order to answer these questions, the work of the American anthropologist Hall (1976) is of great interest. Studying communication styles on the international level, Hall offers a useful framework for adapting intelligence gathering and influencing methods to national cultures. To illustrate this point, we present the case of the People’s Republic of China, which is characterized by implicit communication. Emphasizing this cultural dimension, our research is focused on a type of interpersonal network known as guanxi (关系) and considered by Chen and Chen (2004, p. 317) to be the cornerstone of the Chinese society.

Analyzing guanxi in order to understand the stakes of adapting economic intelligence systems to the Chinese environment, as well as the necessary conditions for this adaptation, is a new research topic in international management. To present this topic, the following article is based upon Bhaskar’s (1975, 1979, etc.) critical realist epistemology, which transcends the recurrent debate between positivism (based on the principle of objectivity, with a weak emphasis on contextualization) and hermeneutics[3] (based on the principle of subjectivity, with a strong emphasis on contextualization). Bhaskar’s ontological perspective invites researchers to take into consideration the time-space context, so important in international business and management (Michailova, 2011), in order to identify and study causal claims (Welch et al., 2011).

This epistemological positioning, referring to abduction as a mode of logical inference (Bhaskar, 1975; Bertilsson, 2004), is essential in understanding the structure of this article. The first and second parts present a synthesis of the work on cultural differences in communication and interpersonal relationships (context). The third part introduces the survey and methodology, while the fourth analyses the specificities of Chinese business with respect to guanxi (from context to causal relationships). The last part seeks to define the role that guanxi can play in economic intelligence systems and presents the development of such systems adapted to the Chinese business environment (from causal relationships to context). Inspired by the critical realist epistemology, this structural pattern is based upon abductive reasoning. It illustrates the contextualized explanation research approach identified by Welch et al. (2011).

Communication and interpersonal relations: a literature review

Culture is a shared system of representations, values, beliefs and practices. According to Hofstede et al. (2010), culture is a collective programming of behavior and judgment which permits a community to analyze an event, treat a problem, establish choice criteria, interpret a message, etc. The cultural context therefore has a determining influence on the conception and implementation of economic intelligence. The use of the term context is, in Hall’s approach (1976), rather large. The term is defined with respect to the speaker (age, gender, status, etc.), to the place of the encounter (convivial/formal, public/private, professional/familial, etc.) and to the reason for the communication (political, commercial, social, etc.). Because context allows us to comprehend the cultural impact on the diffusion and interpretation of messages, Hall proposes to situate low-context and high-context on the extremities of a continuum (Figure 1).

Low-context

In certain cultures, the conditions of the discussion have a weak impact on the communication modes. The interlocutor, the setting and the reason for speaking have very little impact on the interpersonal communication style, which remains virtually the same in all situations. The cultures concerned by this type of context are unmarked or lightly marked by protocols, prejudices, symbols, etc. The system of message diffusion and interpretation is relatively simple, clear and standardized, and the information exchanged is explicit and rather precise.

If we use the relational styles identified by Parsons (1951), and further developed by Trompenaars (1993), low- context is characterized by a culture that is:

individualist with the valorization of the notion of independence, the prioritization of the need for personal realization, etc.,

universalist with the primacy of rules over relations, uniform societal obligations, etc., and

specific with a firm style of communication, inflexible ethical principles, etc.

FIGURE 1

The countries most concerned by this type of communication and interpersonal relationships are, in descending order, Germanic, Scandinavian, and Anglo-Saxon.

High-context

In high-context, the cultural framework conditions the manner of communicating. The importance of rituals, codes, status, and the like ensures that the style of expression and interpretation vary significantly with respect to the speaker, the place and the reason for communicating. The messages emitted in these cultures, characterized by a highly developed sense of community, are generally interwoven and implicit. One must analyze and decrypt them, according to a particular logic, in order to comprehend their true meaning. A specialist on Far East Asia, for example, estimates that the Japanese only fully understand their compatriots 85% of the time (Adams, 1991). Beyond the anecdotal nature of this estimation, we see that this type of cultural context requires a mastery of the silent language of nuance.

With respect to relational orientations, high-context exemplifies a culture that is (Parsons, 1951; Trompenaars, 1993):

collectivist with a strong interdependence between group members, the prioritization of gregarious interests, etc.,

particularist with the primacy of relationships over rules, variable obligations, etc., and

diffuse with a vague communication style, flexible ethical principles, etc.

This type of context characterizes many of the countries of the Far East, the Middle East and Africa.

The differences between high- and low-context types require an adaptation of the economic intelligence approach. While low-context cultures offer a framework that is relatively easy to identify, this is not at all the same for high-context cultures. High-context is characterized by information that is often coded, imprecise and incomplete and by networks of personal relations that are particularly important for functioning and lobbying. How, then, can one implement an effective economic intelligence system in these cultures?

In order to appreciate the specificities of high-context cultures, a study of the People’s Republic of China seems particularly interesting. This country, which occupies a key place in the world economy and which today welcomes a record level of foreign direct investment, illustrates the necessity of adapting the Western system of economic intelligence.

In addition to the attributes already mentioned for high-context cultures, China offers a business framework marked by the pivotal role of guanxi. Guanxi is an interpersonal network comprised of family ties (with relatives and close, trustworthy people), business ties (with distributors, suppliers, competitors and customers), community ties (with industrial associations and labor unions) and/or government ties (with officials and political leaders).

Advantages and disadvantages of guanxi: a literature review

In China, these bonds are essential for economic intelligence because they facilitate information accessibility and resource availability (Chen et al., 2015). Let us briefly present their potential consequences.

Main advantages of guanxi regarding economic intelligence

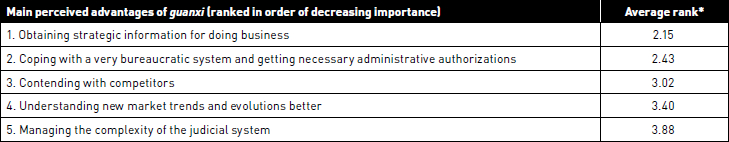

Five key benefits, presented in the literature, could help obtaining information, controlling intelligence diffusion and influencing certain external targets.

Managing the complexity of the judicial system. For more than 2,000 years, Chinese emperors had total authority over the country, with law existing mainly to punish crimes and to organize the bureaucracy to strengthen the rulers’ power and legitimacy (Yan and Hafsi, 2015). The Cultural Revolution changed nothing in regard to this situation, with the Chinese authorities waiting until 1979 to develop their laws (Tam, 2002; Ambler, Witzel and Xi, 2009). Today, the legal system is being restructured and contract enforcement is still uncertain (Yao and Yueh, 2009). Despite the development of the legal framework, personal networks are nevertheless still seen as implicit substitutes to formal regulation[4] As Lewis and Clissold summarize (2004, p. 12), China is subject to the rule of man rather than to the rule of law.

Kwock et al. (2013) go beyond the idea of substitution, observing that guanxi has been institutionalized into the legal system. Because contracts formalize a relationship based on trust and respect, strong guanxi can help the contracting parties avoid problems and disputes (Kwock et al., 2014).

Coping with a highly bureaucratic system and getting necessary administrative authorizations. In the Chinese business system, many operations require administrative authorizations which are sometimes time consuming and difficult to obtain. The bureaucratic system is not only complex, but also opaque. Certain administrative documents presenting governmental decisions, for example, are not always accessible to foreigners (Tung and Worm, 2001). This lack of transparency accords guanxi an important role, as it offers a way of getting around the difficulties in working with the political system, improving material conditions and ensuring the firm’s security. Even recently, this type of networks allows for the informal request of favors from political authorities who control numerous limited resources (Tsang, 1999).

Better understanding of new market trends and evolutions. The Chinese political and economic environment is undergoing important changes that create opportunities, but also generate turbulence that is particularly difficult to manage in a high cultural context. By facilitating the exchange of ideas and analyses, guanxi allows for a better response to the forces that structure the market (Cai and Yang, 2014). It nurtures an informal intelligence system, especially useful in a fast growing economy.

Obtaining strategic information for doing business. Information and trustworthy data are difficult to obtain in China (Gipouloux, 2003). Perhaps a consequence of the high-context culture, the data gathered are often partial and imprecise, or even contradictory and incorrect. Currently, companies implanted in China must be careful with the accounting and financial documents they receive, as organizations in this country cultivate secrecy (Radebaugh and Gray, 1997)[5] This notion of concealing information is in keeping with Hall’s conceptual framework.

More generally, the Chinese are accustomed to functioning with information that is fairly unstructured and not widely diffused. They regularly use their guanxi as an informal exchange system for attaining the desired data (Gu et al., 2008). The situation is the same for multinationals implanted in China: after having conducted a survey of forty European firms, Tung and Worm (2001) report that several business leaders consider access to necessary information as being very difficult without guanxi. Cai and Yang’s survey of 338 manufacturing companies (2014) offers further proof that strong guanxi generally facilitates finding information.

-

Contending with competitors. With increasing competitive intensity, networks are even more useful, having varying pertinence from one type of firm to another. According to Yeung and Tung (1996), guanxi is most important for structures having:

less than ten years of experience in China, and thus insufficient knowledge of the local context to allow them to be autonomous, and/or

a limited size because their sphere of influence are not large enough to allow them to be independent[6]

Furthermore, in a country strongly marked by industrial espionage and counterfeiting, one’s guanxi may offer protection. Lacoste, for example, used its relational network to reach a favorable compromise in the conflict with its competitor Crocodile Garment, who had imitated Lacoste’s logo for competing in Hong Kong and the People’s Republic of China.

Main disadvantages of guanxi regarding economic intelligence

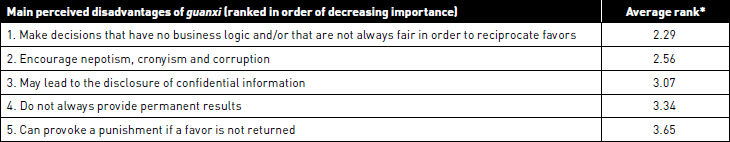

The use of a circle of friends is not, however, without danger as it creates an interdependence that may be detrimental in the long run. Here again, five main drawbacks have been identified in the literature.

-

Guanxi encourages nepotism, cronyism and corruption. Guanxi is sometimes the source of injustice and illegal practices, and can engender a sectarianism that may lead to nepotism, cronyism and corruption (Luo, 2008). Using guanxi and practicing corruption, however, offer clear differences:

a personal network does not require the immediate satisfaction of interests as corruption does (Tung and Worm, 2001); and

a personal network is focused on the relationship and not on the exchange, unlike in corruption (Vanhonacker, 2004).

Thus, even if bribery and special privileges are practiced, generalizations should be avoided.

Guanxi requires the reciprocation of favors. The principle of reciprocal obligations, at the heart of this system, can engender heavy constraints through compromises, special privileges, etc. Indeed, the return of favors explains a number of decisions that are a priori irrational. A supplier offering more expensive and/or lower-quality products, for example, could be chosen in order to reciprocate a favor. Sometimes a company, which benefited from its managers’ networks, is obliged to return a favor that it cannot offer (Gu et al., 2008).

Guanxi can provoke a punishment if a favor is not returned. Chen and Chen (2004, p. 317) state that, because guanxi is the cornerstone of the Chinese society, reciprocity of favor exchanges is the most pervasive rule guiding Chinese social and economic interactions. When a favor is not returned, the cooperating partner feels a sense of moral transgression, which could lead to the punishment of the disloyal partner (Yang, 1957; quoted by Yuan, 2013). As much as possible, firms should therefore associate with trustworthy people who, in exchange for their help, will not demand services that are difficult or illegal to perform.

Guanxi does not always provide permanent results. Favor can be rescinded when the people, who accorded it, no longer occupy their positions. McDonald’s, for example, was able to move into an extremely busy section of Beijing thanks to the help of the mayor. When he was replaced, the firm was obliged to move to a much less attractive area (Tung and Worm, 2001).

Guanxi may lead to the disclosure of confidential information. Guanxi is nebulous, by definition, without clear boundaries. An employee can therefore link with a direct competitor with no feelings of disloyalty, except if the established relations are strong. In this manner, a personal network can be used against the organization’s interests, without the knowledge and/or consent of other members (Liu and Gao, 2014). The informational capital of the firm should thus be protected, as guanxi can become a trap in the long run, with industrial espionage a problem facing many foreign firms in China.

The previous identification of the advantages and disadvantages of guanxi allows us to present the measures for developing a well-adapted economic intelligence approach in China.

Social networks in the People’s Republic of China: survey and methodology

To better understand Chinese network characteristics, we collected data through a questionnaire based on a thorough literature review. From April 2008 to November 2013, this questionnaire was sent to two groups: Chinese students and Chinese Master’s graduates from eight French business schools. For the graduates, the questionnaire was made available online by means of LimeSurvey software. With this data collection method, 133 surveys were returned, but only 61 were complete. Considering the low number of completed questionnaires, the study was limited to analyzing the Chinese students’ answers.

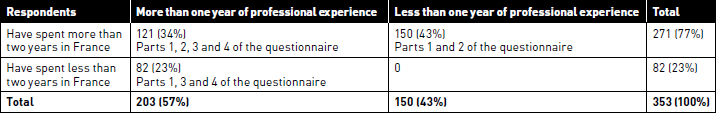

The questionnaire was administrated to 353 Chinese students preparing a Master’s degree in business administration in France. The respondents are characterized by their international mobility, high level of education and urban origins, with 88% coming from a city of more 100,000 inhabitants. Among the students, 57% have over one year of professional experience. With respect to the length of professional experience, the repartition of the sample is as follows: 64.53% have worked between one and three years; 28.57% between four and six years; 5.42% between seven and nine years; and 1.48% more than ten years

The characteristics of this population might raise questions about the representativeness of the sample. Studies about a country as large as China, however, should be considered as puzzle pieces that complete one another. The piece proposed in this article is about the perception of guanxi by (a) internationally-oriented, (b) highly-educated and (c) young Chinese. Because China is a country (a) which has opened its economy to foreign influence, (b) where education is highly respected and is a key asset in networking with influential people, and (c) where managers are quite young[7] the sample used for this study presents specific empirical interests.

To ensure research reliability and construct validity (Cook and Campbell, 1979), as well as to contain the instrumentation bias (Campbell and Stanley, 1963), we adopted the following protocol:

the questionnaire was submitted to a panel of experts for approval (composed of four Chinese professors, three French professors doing research in China, and six French managers who have lived in China for more than ten years);

next, the questionnaire was pre-tested with over one hundred Chinese students preparing a Master of Business Administration in France;

a researcher, either the author or a member of the expert panel, was present while the survey was being administered to answer queries and avoid any misunderstandings;

for most items in the questionnaire, respondents were invited to consider or reject the proposed entry (‘rank the responses that you agree with in order of importance’),

finally, the respondents were invited to propose additional options (‘other [please specify]’).[8]

-

The questionnaire was structured in four parts:

the meaning and image of guanxi in China,

the main perceived differences between Chinese guanxi and French personal networks concepts,

the perceived advantages and disadvantages of guanxi for economic intelligence, and

propositions for foreign managers and companies on creating guanxi in the People’s Republic of China.

All respondents were asked to answer Part 1 of the questionnaire. Only those who had been residing in France for more than two years were requested to complete Part 2. Finally, only those with more than one year of professional experience were invited to complete Parts 3 and 4 (Table 1).

Table 1

Because this study is exploratory, data were processed implementing a univariate analysis. This approach enables the presentation of frequency distributions and rankings. In the article, tables 3 to 5 propose percentages on perception of guanxi (meaning, image, and characteristics); tables 6 to 8 offer scores representing the average ranks (means) of selected propositions about guanxi’s advantages, disadvantages, and development (Table 2). As for the consistency of the univariate analysis, the methodological protocol presented above allowed for the making of a questionnaire avoiding item duplication or incongruity. (Table 2)

Table 2

Guanxi’s characteristics: results and analysis

Guanxi, an illustration of the gregarious dimension of high-context cultures, is a complex social phenomenon with no precise definition. Literally, the term guan means gate or door lock, and the term xi can be translated by relationship or system of links. Guanxi could therefore be defined as:

a gate to pass through in order to be connected (Lee and Dawes, 2005, p. 29), or

a gate that permits a person to open, or not, his system of links to another (Law, Wong, Wang and Wang, 2000, p. 753).

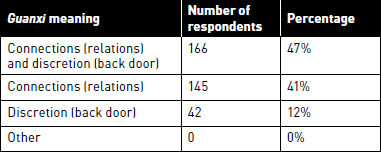

The study we developed seeks to better understand the perception of guanxi by internationally-oriented, highly-educated, young Chinese (Table 3). As shown by the results, the term has two complementary meanings: connections for 88% of the respondents (47% + 41%) and discretion for 59% (47% + 12%). No other terms were proposed by respondents to designate this type of interpersonal network. (Table 3)

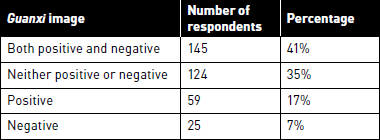

The responses also show that the image of guanxi is rather mixed (Table 4). For 41% of those interviewed, guanxi is simultaneously positive and negative, while for 35% guanxi is neither positive nor negative, but neutral. The unequivocal perceptions are less frequently represented, with 17% of the respondents considering this type of network to be positive and only 7% thinking they are negative. The reasons underlying these perceptions are presented in the next section, as pertaining to better understand the stakes and implementation conditions of an economic intelligence system. (Table 4)

The sixth century B.C. teachings of Confucius are probably at the origin of guanxi, which is deeply anchored in Chinese culture (Yeung and Tung, 1996; Standifird and Marshall, 2000; Rarick, 2010)[9]. These teachings offer a moral framework that values social order, hierarchical organization and loyalty to the family and the clan, and invite society members to develop relationships based on cooperation and social obligation[10].

Guanxi is an institution[11] in the Chinese world, with widespread use within the family, the business world, the educational system, the political sphere, etc. Braendle, Gasser and Noll (2005) underline this type of network’s importance in remarking that business peoples’ success is not measured by their wealth, as in most Western countries, but by the quality and breadth of their connections. In this cultural context, peoples’ relationships define them (Vanhonacker, 2004). If someone is linked to an influential and esteemed individual, for example, he or she will be that much more respected.

This strongly personalized system of links is based on common origins or shared experiences (families, clans, friends, professional networks, etc.) and is maintained through time by the use of gifts, invitations, information exchanges, influence and protection. Reciprocity and mutual obligation are at the heart of this relational logic. The notions of renqing (favor or resource exchange), mianzi (dignity or influence of face)[12] and ganqing (affection) are key elements for establishing long-term confidence and harmony within the network.

In the logic of Hall’s high-context cultures, these gregarious relationships are informal, unofficial, and complex to study, as they are largely characterized by an emotional and personal dimension which is difficult to formalize and measure. In addition to the fact that guanxi is individual and not organizational, it is diffused in the different spheres of a person’s life and is oriented toward the long term, sometimes even being transmitted to the younger generations (Dou and Li, 2013).

The depth of the relationships created depends on the type of guanxi. Yang (1994) identifies three types of relations.

The first circle is that of the jiaren. These people are family members, or are considered as such, with whom links are deep and in whom confidence is generally total.

The second circle is that of the shuren. In this case, the network is composed of friends, partners, colleagues, neighbors, and others, with whom relations are more or less developed and who are generally accorded much confidence.

The third circle is that of the shengren. These are strangers or distant acquaintances, with whom relations are calculated and who are generally mistrusted a priori.

Table 3

While the business world functions on all three of these levels of relationships, priority is given to the jiaren, then to the shuren, and finally to the shengren. The farther one moves from the first circle, the more guanxi becomes utilitarian and instrumental. In order for this system to be stable and effective, in principle one must pass from the status of shengren to shuren. Indeed, in colloquial speech, the term guanxi is generally reserved for shuren (Lee and Dawes, 2005).

For Saint-Charles (2005), irrespective of the cultural background, people refer to friendship networks in situations of ambiguity, underlining the importance of guanxi in a society characterized by implicit and coded communication. For Western firms working in China, the development of a circle of friends therefore seems essential for implementing and developing economic intelligence in a low-context society (Hall, 1976).

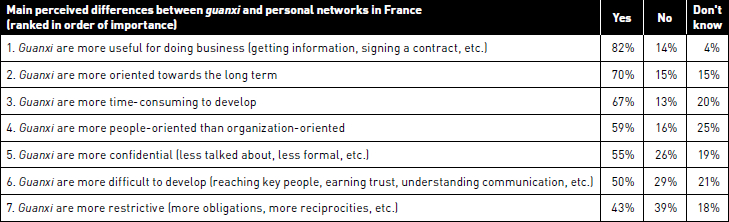

To more precisely identify the differences between guanxi and networks developed in Western countries, we asked respondents who have been in France for more than two years to confirm or refute seven proposals. All the proposed differences were validated by the majority of the participants, thus showing that the meanings and functional modes of guanxi are specific to the Chinese context (Table 5). This type of network is considered to be more useful for business, more long-term oriented, more personal[13] and more confidential than French networks. Furthermore, it is seen as more time-consuming and difficult to develop. (Table 5)

The fact that, in this study, French interpersonal networks are used to represent the Western world could be open to discussion. As seen in Hall’s work (1976), differences do exist in Occidental countries in terms of communication contexts and message types. Taking France as a benchmark, however, may provide for a degree of international transferability regarding the results of this study. Because France is closer to China than most Western nations in terms of interpersonal communication (figure 1), the main differences listed in table 4 could also be applicable to more distant cultures (e.g., Germanic or Nordic countries).

Table 4

Guanxi’s potential impact on economic intelligence: results and contributions

The importance of guanxi for developing a system of intelligence and influence in China can be more precisely understood in light of the survey results. The respondents, with more than one year of professional experience (57%), validated all five of the main advantages of guanxi identified from the literature review and expert discussions. These benefits are all related to the double goals of economic intelligence: gaining information and lobbying (Table 6).

Propositions of five main drawbacks related to economic intelligence, were also validated by the questionnaire results. These drawbacks point to the different types of costs associated with maintaining an interpersonal network (table 7).

The previous identification of the advantages and disadvantages of guanxi allows us to present the measures for developing a well-adapted economic intelligence approach in China.

As with many managerial practices, economic intelligence is partially conditioned by national culture (Adidam et al., 2009). The preceding developments, combined with Hall’s (1976) anthropologic study, allow us to say that, in high-contexts, the relationship is perceived as being more important than the transaction. Guanxi thus seems to be necessary for developing an efficient and durable economic intelligence system in the People’s Republic of China.

Of the nine implementation suggestions ranked in our study by respondents with more than one year of professional experience (57%), four of the five top propositions are linked to the development of trusted relationships with key people (Table 8). In a cultural context characterized by implicit messages, these results are not surprising. The limited availability and usefulness of external quantitative information invites the use of stable and well-informed relations to nurture managers’ thinking and decision-making. Let us develop these different propositions for creating an adapted economic intelligence system in China. (Table 8)

Table 5

Table 6

N = 182

* The scores presented are the mean of the responses on a scale of 1 (most important proposal) to 5 (least important proposal). Only 182 of the 203 questionnaires were used for this question, as the other 21 were incomplete.

Table 7

N = 183

* The scores presented are the mean of the responses on a scale of 1 (most important proposal) to 5 (least important proposal). Only 183 of the 203 questionnaires were used for this question, as the other 20 were incomplete.

Identify key people to contact

The respondents to our questionnaire consider the detection of key people (important leaders, senior officials, respected individuals, etc.) as being essential for developing guanxi and implementing an economic intelligence system. In order to contact key people, Tung and Worm (2001) observe that firms adopt the following procedures, in decreasing order of importance:

invite them to visit the firm’s sites in China and/or abroad, all costs paid;

entertain them through social events; and/or

offer gifts having little venal value, etc.

Be patient in gaining the trust of key people

Chinese are a long-term oriented people (Hofstede et al., 2010). Thus, it is wise to take the time to establish a sustainable relationship based on trust. To develop this trust in a high-context culture, managers must learn how to decode the communications logic that is used inside and outside of the network. This complex learning process cannot be achieved in a short period. In Tung and Worm’s study (2001), for example, 83% of respondents indicate that they needed at least one year to incorporate the targeted person into their guanxi. Chang and Lii (2005) note that interpersonal networks are particularly solid when relations are based on regular exchanges. Ramasamy, Goh and Yeung (2006) conclude that confidence and communication are the two principal vectors of knowledge transfer within guanxi, on the basis of a study of 215 Chinese firms.

Table 8

N = 180

* The scores presented are the mean of the responses on a scale of 1 (most important proposal) to 9 (least important proposal). Only 180 of the 203 questionnaires were used for this question, as the other 23 were incomplete.

Learn the communication styles and customs in China

Not surprisingly, respect of the communication and behavioral logic that characterizes Chinese culture is highly ranked by respondents. Foreigners must, for example, show consideration to the hierarchy, accept indirect or vague statements, decode nonverbal communication (silence, facial gazing, etc.), understand the importance of saving face, use famous quotes or proverbs, etc.

Be involved in a long-term relationship

The creation of a long-term network for implementing an economic intelligence system based on confidence and respect is important. As we already saw, unlike the majority of Westerners, Chinese are culturally oriented toward the long term (Hofstede et al., 2010). Very perseverant, they take time to know their partners before developing projects with them, in order to understand the implicit messages of the partners and to make themselves clearly understood.

Understand that ‘Who you know’ is more important than ‘What you know’

People seeking to create or improve economic intelligence systems should integrate the notion that, in Confucian societies, relationships (who you know) are more important than information (what you know). In keeping with this principle, the Chinese believe building a relation is necessary before beginning a transaction, as opposed to Westerners who concentrate on negotiating the transaction before establishing a true relationship, if ever.

Respect the principle of returning favors

As previously mentioned, the relationships that link guanxi members are largely based on the notion of mutual aid (Chen and Chen, 2004). If reciprocity is not respected, the network has no cement and therefore falls apart because non-reciprocity can make people lose face and break trust established in the past (Yang, 1957; quoted by Yuan, 2013).

Present oneself as a friend of the People’s Republic of China

Presenting oneself as a friend of the country is well-perceived in China. When Coca-Cola penetrated the Chinese market in 1979, for example, they encountered a certain amount of hostility because many believed that they would harm Chinese firms in the soda industry. After years of effort to establish relationships with local communities through the construction of primary schools, libraries, etc., Coca-Cola was finally able to negotiate good conditions for their implantation with government authorities. Because of their network, The Coca-Cola Company obtained the necessary authorizations for constructing factories more easily, allowing the group to dominate the Chinese carbonated soft drink business, with 63% market share in 2014 (Euromonitor quoted by Freifelder, 2015). PepsiCo offers a counter-example, as they invested less in their networks and, therefore, had more difficulty in establishing joint ventures. PepsiCo’s market share in this country, for the same products, is less than half of The Coca-Cola Company’s, with only 30% in 2014 (Deutsche Bank quoted by Freifelder, 2015).

Hire intermediaries

The use of intermediaries is a solution that is increasingly adopted by foreigners. Liu and Gao (2014) identified four types of guanxi boundary spanners:

Chinese locals working for foreign-owned companies in China as local managers, distributors, and brokers;

local business partners;

government officials; and

managers in Chinese-owned companies who connect their foreign clients with other contacts in their personal business networks.

A fifth type of boundary spanner refers to specialized consultants who propose using their networks to facilitate the implantation or development of foreign firms. By organizing meetings, searching for clients, and forwarding information, they help to save time, avoid pitfalls and acquire savoir-faire essential for creating and managing guanxi. The local reputation of these consultants, however, based on the respect of social norms, may limit the quantity and quality of information they are able to transmit to foreign clients.

Distinguish business-to-business from business-to-government guanxi

Many questionnaire respondents minimized the importance of distinguishing between the two types of guanxi, as they consider them to be linked. Because of differences between these types of networks, however, companies may benefit from making this distinction.

Business-to-business guanxi allows for the collection of information on business trends and opportunities in a given sector (Braendle, Gasser and Noll, 2005). It also gives access to information about partners or even competitors, which is difficult to obtain.

Business-to-government guanxi is generally used to take advantage of support and/or to facilitate the necessary authorizations for doing business in the country. This type of network also allows access to little-diffused information, most notably information presented in internal documents. For Fan (2002), the business-to-government guanxi is the most dangerous type of network as it can slide toward corruption.

The preceding recommendations for building an economic intelligence system are linked to the logic of influence, the key element for lobbying. They can be sorted into three subject categories.

Four recommendations are based on personal relationships (Identify key people to contact [1st], Be patient in gaining the trust of key people [2nd], Be involved in a long-term relationship [4th] and Understand that Who you know is more important than what you know [5th]).

Three others refer explicitly to communication and image (Learn the communication styles and customs in China [3rd], Respect the principle of returning favors [6th] and Present oneself as a friend of the People’s Republic ofChina [7th]).

The final two recommendations reflect the conditions for network development (Hire intermediaries [8th] and Distinguish between business-to-business guanxi and business-to-government guanxi [9th]).

In a high-context culture, the definition and implementation of economic intelligence systems are thus principally based on the logic of influence (table 7). Contrary to what is observed in the West, learning and lobbying are not independent: in China, the logic of influence determines the logic of knowledge. Because the quest for information is dependent upon influence, the Chinese cultural context encourages a sequential organization of economic intelligence systems (influence first, then information).

While these remarks aim to facilitate the development of guanxi in China, they do not offer an infallible process, as the contingency factors are too numerous to ensure success in a country with a high-context culture.

Conclusion

Kanter (1995) maintains that, in order to succeed in a globalized world, one needs three types of intangible assets: concepts, competence and connections (3 C’s). This formula indicates the bases necessary for economic intelligence. Evidently, these different assets have varying levels of importance in different industries and countries. As seen in the preceding discussions, connections (the third C) are particularly important in a high-context culture such as the People’s Republic of China.

Guanxi leads to increased visibility, better access to resources, the acceleration of certain operations, a reduction of transaction costs, better relationships with partners, and easier access to targeted markets. Source of competitive advantage, guanxi is essential for implementing economic intelligence systems in this type of culture.

Several studies have empirically demonstrated that the links established with managers from other companies and with government officials helped improve firms’ performance in China (Peng and Luo, 2000; Luo, Huang and Wang, 2012; Wang, Wang and Zheng, 2014; Chung, Yang and Huang, 2015). Certain specialists even believe that guanxi is a necessary formality, or a sine qua non condition, for the development of efficient economic action in this country (Bjorkman and Kock, 1995; Lee and Dawes, 2005, etc.).

Consistent with this body of literature, our study presents insights about the importance of guanxi for gaining access to information and developing influence in the People’s Republic of China. Inspired by Bhaskar’s critical realist ontology (1975, 1979, etc.), abductive reasoning was adopted, allowing the combination of two research focuses: contextualization and causal explanation (Welch et al., 2011). After identifying the potential consequences - both positive and negative - of using guanxi for doing business, the study presents nine propositions for developing economic intelligence in this country, ranked by importance. Furthermore, this work shows that guanxi involving key people may be a source of influence and that this influence is essential in facilitating access to information (logic of knowledge). This conclusion, however, calls for further research.

The People’s Republic of China is not culturally homogeneous: surveys about sub-cultures in different geographic areas, industries, etc. could lead to more detailed understanding.

The study is based on opinions expressed by highly-educated and internationally-oriented Chinese with limited professional experience: questioning senior managers could provide other recommendations.

The impact of guanxi on economic intelligence is a new topic of research: complementary studies could lead to additional insights.

The comparison between French interpersonal networks and Chinese guanxi cannot guarantee that the conclusions presented in this article are entirely applicable to other Western countries: a comparison of the results of this study with surveys conducted in different countries could be beneficial.

Indeed, further studies should be undertaken because - despite the development of the private sector in China, their growing commercial accessibility, and the training of their managers in Western management techniques - the subtle roles and functions of guanxi have yet to be studied. The deep-rooted nature of guanxi in Chinese culture would seem to indicate that it will remain an important part of the Chinese business world, as confirmed by the 60.7% of participants in our study who think that guanxi will be more important in the future.

Appendices

Biographical note

Eric Milliot is Associate Professor of Management Science, Head of the Department of Strategy and Marketing at the Institut d’Administration des Entreprises (School of Business) of the University of Poitiers. Vice-President of Atlas/AFMI (Association Francophone de Management International) and member of the research laboratory CEREGE, his studies concern principally the strategic and organisational systems developed by companies in the face of globalisation. On this topic, he has published three books and different academic articles. This field of research has led to his giving classes and seminars in several countries (University of California at Berkeley, University of Nanchang, Universidade de Fortaleza, Aïn Shams University, Thang Long University, Ecole supérieure des affaires de Beyrouth, INSCAE d’Antananarivo, etc.).

Notes

-

[1]

The author would like to thank Ulrike Mayrhofer, Shawna Milliot-Guinn, Nicolas Moinet, Fabrice Roubelat, Yves Roy and three anonymous reviewers, for their comments on the initial text. Further thanks go to the thirteen members of the expert panel, who helped improve the survey questionnaire. Parts of this work first appeared in an article published in French (Milliot, 2006). In addition to the language difference, the present article has a wider research question, proposes a more precise definition of economic intelligence, includes an empirical study and comes to additional conclusions.

-

[2]

A lobby is considered as a group of actors attempting to influence, more or less discretely, external stakeholders’ decision-making processes and/or operating modes. In accordance with the five domains of intelligence associated with the PREST model, this influence can be political (with government authorities, etc.), regulatory (with legislators, etc.) economic (with suppliers, etc.), social (with public opinion, etc.) and technological (with patent protection authorities, etc.).

-

[3]

We are referring to Heidegger’s philosophy (1927).

-

[4]

The substitution of a circle of friends for formal regulation confirms China’s positioning as a country with a high-context communication.

-

[5]

Bertin and Jaussaud (2003), however, remark that the audit function is being developed in China and that the government is implementing a system of rules that includes severe punishment for auditors who are not rigorous.

-

[6]

These conclusions are confirmed by the results of a study conducted by Hutchings and Murray (2002).

-

[7]

Because of its fast-growing economy, China is facing a managerial talent shortage (Barris, 2013). Thus, graduate students have opportunities to rapidly become managers.

-

[8]

This option was never used by the respondents who completed the final version of the questionnaire.

-

[9]

If the notion of network is essential in the People’s Republic of China, it is also equally so in other Confucian cultures characterized by a high-context, such as Japan and South Korea.

-

[10]

Fayol-Song (2004) points out that, while collectivism is largely respected in the People’s Republic of China on the ideological level, the Chinese are becoming increasingly individualistic.

-

[11]

In this research, the word institution is used to refer to a stable social structure.

-

[12]

Related to the notion of saving face, mianzi translates the need to be honored and respected by the interlocutor.

-

[13]

This networked system, a form of true social capital, is created between individuals and not really between organizations. Chen and Chen (2009) maintain that the personal nature of guanxi is causing negative externalities on organizations. If people leave their firms, for example, they take their guanxi with them (Gomez Arias, 1998).

Bibliography

- Adams, E. (1991). “Scaling the Tower of Babel”, World Trade, April, p. 42-45.

- Adidam, P. T.; Gajre, S.; Kejriwal, S. (2009). “Cross-cultural Competitive Intelligence Strategies”, Marketing Intelligence & Planning, Vol. 27, N° 5, p. 666-680.

- Ambler, T.; Witzel, M.; Xi, C. (2009). Doing Business in China, 3rd edition, New York: Routledge.

- Barris, M. (2013). “China Faces World’s Worst Managerial Shortage”, China Daily USA, August 2, p.10.

- Bertilsson, M. (2004). “The Elementary Forms of Pragmatism: On Different Types of Abduction”, European Journal of Social Theory, Vol. 7, N° 3, p. 371-389.

- Bertin, E.; Jaussaud J. (2003). “L’audit légal de l’entreprise en Chine”, Revue Française de Comptabilité, Mai, p. 38-41.

- Bhaskar, R. (1997 [1st edition, 1975]). A Realist Theory of Science, 2nd edition, London: Verso.

- Bhaskar, R. (1998 [1st edition, 1979]). The Possibility of Naturalism: A Philosophical Critique of the Contemporary Human Sciences, 3rd edition, New York: Routledge.

- Bjorkman, I.; Kock, S. (1995). “Social Relationships and Business Networks: The Case of Western Companies in China”, International Business Review, Vol. 4, N° 4, p. 519-535.

- Braendle, U.; Gasser, T.; Noll, J. (2005). “Corporate Governance in China – Is Economic Growth Potential Hindered by Guanxi?”, Business and Society Review, Vol. 110, N° 4, p. 389-405.

- Cai, S.; Yang, Z. (2014). “The Role of the Guanxi Institution in Skill Acquisition Between Firms: A Study of Chinese Firms”, Journal of Supply Chain Management, Vol. 50, N° 4, p. 3-23

- Campbell, D.; Stanley, J. (1963). Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research, Chicago: Rand-McNally.

- Chang, W. L.; Lii, P. (2005). “The Impact of Guanxi on Chinese Managers’ Transactional Decisions: A Study of Taiwanese SMEs”, Human Systems Management, Vol. 24, N° 3, p. 215-222.

- Chen, C.; Chen, X.-P. (2009). “Negative Externalities of Close Guanxi within Organizations”, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Vol. 26, N° 1, p. 37-53.

- Chen, M.-H.; Chang, Y.-Y.; Lee, C.-Y. (2015). “Creative Entrepreneurs’ Guanxi Networks and Success: Information and Resource”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 68, p. 900-905.

- Chen, X.-P.; Chen, C. (2004). “On the Intricacies of the Chinese Guanxi: A Process Model of Guanxi Development”, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Vol. 21, p. 305-324.

- Chirouze, Y.; Moinet, N. (2006). “Editorial”, RevueMarketing & communication (renamed Revue Communication & Management), Vol. 3, N° 3, p. 2-4.

- Chung, H.; Yang, Z.; Huang, P.-H. (2015). “How Does Organizational Learning Matter in Strategic Business Performance? The Contingency Role of Guanxi Networking”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 68, p. 1216-1224.

- Cook, T.; Campbell, D. (1979). Quasi-Experimentation: Design and Analysis Issues for Field Settings, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Dou, J.; Li, S. (2013). “The Succession Process in Chinese Family Firms: A Guanxi Perspective”, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Vol. 30, N° 3, p. 893-917.

- Fan, Y. (2002). “Questioning Guanxi: Definition, Classification and Implications”, International Business Review, Vol. 11, N° 5, p. 543-561.

- Fayol-Song, L. (2004). “C’est du Chinois: les difficultés de décoder les grandes caractéristiques de la culture chinoise”, dans P. Callot (sous la direction de), Les échanges commerciaux avec la Chine: aspects sociologiques et culturels, Paris: Hermès.

- Freifelder, J. (2015). “Beverage Battle in China Goes beyond Colas”, China Daily USA, May 12, (http://usa.chinadaily.com.cn/epaper/2015-05/12/content_20692838.htm)

- Gipouloux, F. (2003). “Projet en Chine, comment gérer l’information?”, Conférence du Club d’Intelligence Economique et Stratégique de l’IAE de Paris, 2 Juillet.

- GomezArias, J. (1998). “A Relationship Marketing Approach to Guanxi”, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 32, N° 1, p. 145-156.

- Gu, F., Hung, K., Tse, D. (2008). “When Does Guanxi Matter? Issues of Capitalization and Its Dark Sides”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 72, N° 4, p. 12-28.

- Hall, E. T. (1976). Beyond Culture, New York: Doubleday.

- Heidegger, M. (1962 [first edition, 1927]). Being and Time, San Francisco: Harper.

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J; Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, 3rd edition, New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Hutchings, K.; Murray, G. (2002). “Working with Guanxi: An Assessment of the Implications of Globalisation on Business Networking in China”, Creativity and Innovation Management, Vol. 11, N° 3, p. 184-191.

- Kanter, R.M. (1995). World Class, New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Kwock, B.; James, M.; Tsui, A. (2013). “Doing Business in China: What is the Use of Having a Contract? The Rule of Law and Guanxi when Doing Business in China”, Journal of Business Studies Quarterly, Vol. 4, N° 4. p. 56-67.

- Kwock, B.; James, M.; Tsui, A. (2014). “The Psychology of Auditing in China: The Need To Understand Guanxi Thinking and Feelings as Applied to Contractual Disputes”, Journal of Business Studies Quarterly, Vol. 5, N° 3, p. 10-18.

- Larivet, S. (2009). Intelligence économique - Enquête dans 100 PME, Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Law, K.; Wong, C.; Wang, D.; Wang, L. (2000). “Effect of Supervisor-Subordinate Guanxi on Supervisory Decisions in China: An Empirical Investigation”, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 11, N° 4, p. 751-765.

- Lee, D.; Dawes, P. (2005). “Guanxi, Trust, and Long-Term Orientation in Chinese Business Markets”, Journal of International Marketing, Vol. 13, N° 2, p. 28-56.

- Lemaire, J.P. (2000). “Measuring the International Environment Impact on Corporate Marketing and Strategy: the PREST model”, 16th IMP Conference, Bath, 7-9 September.

- Lemaire, J.P. (2013). Stratégies d’internationalisation: nouveaux enjeux pour les organisations, les activités et les territoires, 3ème édition, Paris: Dunod.

- Lewis, D.; Clissold, T. (2004). “A Disorderly Heaven”, The Economist, March 20, Special section, p. 10-13.

- Liu, A. H.; Gao, H. (2014). “Examining Relational Risk Typologies for Guanxi Boundary Spanners: Applying Social Penetration Theory to Guanxi Brokering”, Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice, Vol. 22, N° 3, p. 271-284.

- Luo, Y. (2008). “The Changing Chinese Culture and Business Behavior: The Perspective of Intertwinement between Guanxi and Corruption”, International Business Review, Vol. 17, N° 2, p. 188-193.

- Luo, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S. L. (2012). “Guanxi and Organizational Performance: A Meta-Analysis”, Management and Organization Review, Vol. 8, N° 1, p. 139-172.

- Michailova, S. (2011). “Contextualizing in International Business research: Why do we need more of it and how can we be better at it?”, Scandinavian Journal of Management, Vol. 27, N° 1, p. 129-139.

- Milliot E. (2006). “L’intelligence économique dans un pays à contexte culturel fort: cas de la République Populaire de Chine”, RevueMarketing & Communication (renamed Revue Communication & Management), Vol. 3, N° 3, septembre, 72-83.

- Parsons, T. (1951). The Social System, New York: Free Press.

- Peng, M.; Luo, Y. (2000). “Managerial Ties and Firm Performance in a Transition Economy: The Importance of Micro-Macro Links”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 43, N° 3, p. 486-501.

- Prime, N.; Usunier, J. C. (2015). Marketing international: Marchés, cultures et organisations, 2e édition, Paris: Pearson.

- Radebaugh, L.; Gray, S. (1997). International Accounting and Multinational Enterprises, 4th edition, New York: Wiley.

- Ramasamy, B.; Goh, K.W.; Yeung, M. (2006). “Is Guanxi (Relationship) a Bridge to Knowledge Transfer?”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 59, N° 1, p. 130-139.

- Rarick, C. A. (2010). “The Historical Roots of Chinese Cultural Values and Managerial Practices”, Journal of International Business Research, Vol. 8, N° 2, p. 59-66.

- Saint-Charles, J. (2005). “Les réseaux de conseil et d’amitié: une question d’incertitude et d’ambiguïté”, Management International, Vol. 9, N° 2, p. 51- 60.

- Standifird, S.; Marshall, R. (2000). “The Transaction Cost Advantage of Guanxi-Based Business Practices”, Journal of World Business, Vol. 35, N° 1, p. 21-42.

- Tam, O. (2002). “Ethical Issues in the Evolution of Corporate Governance in China”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 37, N° 3, p. 303-320.

- Trompenaars, F. (1993). Riding the Waves of Culture, New York: Irwin.

- Tsang, E. (1999). “Can Guanxi be a Source of Sustained Competitive Advantage for Doing Business in China?”, Academy of Management Executive, Vol. 12, N° 2, p. 64-73.

- Tung, R.; Worm, V. (2001). “Network Capitalism: The Role of Human Resources in Penetrating the China Market”, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 12, N° 4, p. 517-534.

- Vanhonacker, W. (2004). “Guanxi Networks in China”, The China Business Review, Vol. 31, N° 3, p. 48-53.

- Wang, G.; Wang, X.; Zheng, Y. (2014). “Investing in Guanxi: An Analysis of Interpersonal Relation-Specific Investment (RSI) in China”, Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 43, N° 4, p. 659-670.

- Welch, C.; Piekkari, R.; Plakoyiannaki, E.; Paavilainen-Mäntymäki, E. (2011). “Theorising from Case Studies: Towards a Pluralist Future for International Business Research”, Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 42, N° 5, p. 740-762.

- Yan, L.; Hafsi, Y. (2015). “Philosophy and Management in China: An Historical Account”, Management International, Vol. 19, N° 2, p. 246-259.

- Yang, K. (1994). Gifts, Favors, and Banquets: The Art of Social Relationships in China, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Yao, Y.; Yueh, L. (2009). “Law, Finance, and Economic Growth in China: An Introduction” World development, Vol. 37, N° 4, p. 753-762.

- Yeung, I.; Tung, R. (1996). “Achieving Business Success in Confucian Societies: The Importance of Guanxi (Connections)”, Organizational Dynamics, Vol. 25, N° 2, p. 54-65.

- Yang, L.-S. (1957). “The Concept of ‘Pao’ as a Basis for Social Relations in China”, in J. K. Fairbank (ed.), Chinese Thought and Institutions, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 291-309.

- Yuan, L. (2013). Traditional Chinese Thinking on HRM Practices: Heritage and Transformation in China, London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Appendices

Note biographique

Eric Milliot, maître de conférences HDR en sciences de gestion, est responsable du département Stratégie et marketing et du Master Commerce international à l’Institut d’administration des entreprises (IAE) de l’Université de Poitiers. Vice-président d’Atlas/AFMI (Association Francophone de Management International) et membre du laboratoire de recherche CEREGE (EA 1722), ses travaux portent essentiellement sur les logiques stratégiques et organisationnelles développées par les entreprises face à la globalisation de l’économie. Il a publié, sur cette thématique, trois ouvrages et différents articles académiques. Ce champ de recherche l’a amené à donner cours et séminaires dans une quinzaine de pays (University of California at Berkeley, University of Nanchang, Universidade de Fortaleza, Aïn Shams University, Ecole supérieure des affaires de Beyrouth, INSCAE d’Antananarivo…).

Appendices

Nota biográfica

Eric Milliot, Profesor Titular en Ciencias Empresariales, es Director del departamento de Estratégia y Marketing y del Máster en Comercio International en el Institut d’administration des Entreprises (IAE) de la Universidad de Poitiers. Vicepresidente de Atlas/AFMI (Asociación Francófona de Management Internacional) et miembro del laboratorio de investigación CEREGE (EA 1722), sus trabajos tratan esencialmente sobre las lógicas estratégicas y organizacionales que las empresas desarrollan para hacer frente a la globalización de la economía. Ha publicado, sobre esta temática, tres libros y diferentes artículos académicos. Este campo de investigación le ha dado la oportunidad de dar clases y seminarios en más de quince países (Universidad de California en Berkeley, Universidad de Nanchang, Universidad de Fortaleza, Aïn Shams University, Ecole supérieure des affaires de Beyrouth, INSCAE d’Antananarivo, etc.).

List of figures

FIGURE 1

List of tables

Table 1

Table 2

Table 3

Table 4

Table 5

Table 6

Table 7

Table 8

10.7202/1030398ar

10.7202/1030398ar