Abstracts

Abstract

Drawing on rural, biotechnological, and environmental history, this article examines how farmers, corporations, and the state deployed developments in silviculture and agriculture to reshape Norfolk County, Ontario. It traces the emergence of a relatively vibrant flue-cured tobacco sector during the Great Depression, a sector that both broke from and drew on earlier reforestation efforts that had emerged at the start of the twentieth century. In this context, tobacco and trees can best be viewed as biotechnologies connected to a continental flow, rather than simply as natural products. The article also argues that raising both trees and tobacco drew on ideas of conservation and resource management that were tightly bound to the development of rural capitalism, but highlights how the soil and environment influenced the capitalist objective of profitable rural development in ways that frustrated the idea of nature being manageable. It ends by noting that despite the ascendency of capitalist-informed ideas about rural development in Norfolk, other ways of understanding soil and the environment persisted.

Résumé

S’appuyant sur l’histoire rurale, environnementale et de la biotechnologie, le présent article examine comment les fermiers, les entreprises et l’État ont mobilisé diverses avancées en sylviculture et en agriculture pour changer le visage du comté de Norfolk, en Ontario. Il relate la naissance d’un secteur relativement dynamique du tabac jaune durant la crise de 1929, secteur qui à la fois rompait avec les efforts de reboisement entamés au tournant du XXe siècle et s’en inspirait. Dans ce contexte, le tabac et les arbres peuvent être vus comme des biotechnologies liées à un mouvement continental au lieu de simples produits de la nature. L’article avance que la culture à la fois d’arbres et du tabac se fonde sur des notions de conservation et d’aménagement des ressources qui étaient étroitement liées à l’essor du capitalisme rural, mais il fait ressortir la façon dont les sols et l’environnement ont influencé l’objectif capitaliste d’un développement rural rentable qui allait à l’encontre de l’idée que la nature pouvait être gérée. Il termine en notant que, malgré la montée d’idées inspirées du capitalisme entourant l’aménagement rural de Norfolk, d’autres façons de voir les sols et l’environnement ont persisté.

Article body

During the depths of the Great Depression, Norfolk County, Ontario, underwent a dramatic transformation. Flue-cured tobacco, the tobacco suited for the burgeoning cigarette trade, grew in an increasing number of farms in the area. Between 1928 and 1932, flue-cured tobacco production in Ontario increased from approximately 8,726,000 pounds to 27,615,000 pounds, and Norfolk County was at the forefront of that growth. By 1938, the so-called ‘New Belt’ of tobacco production that centred in Norfolk, stretching into Elgin and Oxford counties, contained 52,600 of the approximately 58,000 acres of flue-cured tobacco planted in Ontario.[1] Farmers and the tobacco industry altered the Norfolk Sand Plain, which foresters had condemned as ‘wasteland,’ unfit for cultivation, into the centre of a relatively prosperous agricultural industry. As The Simcoe Reformer enthused in 1932, “Tobacco has blossomed like the rose in the desert on this land.”[2] While flue-cured tobacco did not guarantee returns — as fights over the marketing and prices of tobacco during the 1930s indicated — it nonetheless became one of the more prosperous sections of Canadian agriculture during a tumultuous period. Thousands of unemployed people came to the tobacco towns of Delhi, Simcoe, and Tillsonburg during the harvest season looking for work, buoyed by exaggerated stories of paying work for prosperous farmers.[3] The formation of a stable flue-cured tobacco sector in Norfolk seemed a testimony to the capacity of human ingenuity and technology to manage nature and create prosperity — at the long-term expense of human health as people consumed the product that bloomed in the desert.[4]

Flue-cured tobacco emerged late as a means to solving the problem concerning the presence of a ‘wasteland’ in Ontario’s fertile southwest. Prior to the development of flue-cured tobacco production in the mid-1920s, the government had slated much of the same soil as a prime location for efforts to begin restoring southern Ontario’s long beleaguered forest. Indeed, the sand-swept plains of Norfolk represented human avarice and folly; desolate, dead land stood where farmers and foresters had taken what fruits of nature they could claim. Through the photographs of Edmund Zavitz, the forester who spearheaded Ontario’s forests, the destruction became well known. His 1908 pamphlet, Report on the Reforestation of Waste Lands in Southern Ontario, contained a remarkable collection of photos selected to illustrate the harm of removing trees in the sand plain, and was circulated by Ontario’s Department of Agriculture. Discussing a shot taken in Charlotteville township, he noted that the tree’s “dwarfed scrubby appearance is owing to poor soil conditions caused from frequent ground fires, and also owing to the fact that as soon as a tree reaches three or four inches in diameter it is cut for fuel wood.”[5] For Zavitz, the solution to save the sand plains was to launch a comprehensive program of tree planting, beginning with the creation of a hundred acre nursery near St. Williams, where foresters could test different varieties of trees for viability in the area, and share information on the best varieties for windbreaks and woodlots with landowners. He called for the government to classify such land as unfit for agriculture and designate the land to be “permanently managed for forest crops.”[6] From these beginnings, Norfolk County had the most trees planted of any southern Ontario county during the 1920s.[7]

Taking these two developments that reshaped the Norfolk landscape, this article focuses on the relationship between tobacco and forestry in the Norfolk Sand Plain. Tobacco interests remade the agricultural wasteland of foresters, but they also drew on the insights of forestry to advance a program of planting windbreakers during the 1930s, when soil erosion and storms began to threaten yields. Tobacco experts drew on a language of conservation and ecological restitution similar to that employed by forestry officials. However, this restitution largely differed from the ideas represented by John Muir’s Sierra Club, inspired by the desire to preserve nature, or Jack Miner’s bird sanctuary, shaped by a religious and lived sense of humanity’s dominion over nature.[8] Their increased calls for windbreakers and attentiveness to the trees of the farm emerged from an intellectual context bound to modern capitalism, a context that cast both tree and plant as technologies that humans could manage. The context was ‘modern’ insofar as farmers increasingly relied on technology (including the kilns necessary for flue-cured tobacco) and gradually produced less of what they consumed themselves.[9] It was capitalist owing to the emergence of tobacco plantations and other farms that orientated towards profit-maximizing specialized production and because that production was powerfully influenced by the Imperial Tobacco Company of Canada, which demanded a light tasting flue-cured tobacco. As tobacco cultivation proliferated, conservation persisted, but connecting conservation to profit and long term economic returns meant that it appealed to homo economicus more than to the ecological human. This is not to suggest that economic motives and conservation are fundamentally antithetical, but that economic motives essentially shaped conservation efforts in this case as in many others.[10] Thus, the interaction of tobacco and trees in the Norfolk Sand Plain is an interaction of technologies intimately connected to modern capitalism.

The technological aspect of this argument is particularly influenced by Barbara Hahn, who recently noted that Bright tobacco, the variety most associated with flue-curing and cigarettes, is primarily a technology: “This distinctive cultivar is an artifact of [a] specific cultivation system, [and belongs to] these technological processes whose result is a marketable product.”[11] I also draw on a recent article by Robert Gardner who argues that the windbreakers planted in the Great Plains were themselves a form of technology. “From the first efforts of individual settlers in the 1800s to large scale government programs in the 1930s, the shelterbelts planted on the Great Plains were human-built technological systems designed to solve specific environmental and social problems.”[12] These histories connect to a growing scholarship that asserts organic industrial innovation had as great a role in reshaping the rural countryside as did mechanization, collapsing easy distinctions between environment and technology.[13] Edmund Russell suggests that we use the term biotechnology to refer to living technology, such as trees or tobacco. More specifically, he proposes referring to the selection of particular varieties through experimentation and breeding at the plant level as macrobiotechnology, as opposed to molecular, genetically-based engineering (or, microbiotechnology) that proliferated in the postwar era.[14]

While casting trees and tobacco as biotechnologies, it is also vital to impress that, as organic technologies, they were tied to the soil they grew in. Land played a foundational role in the cultivation of flue-cured tobacco, literally setting the terrain for its cultivation. Flue-cured tobacco destined for cigarettes grew best on a sandy, well-draining soil that simultaneously provided the plant with sufficient water and nutrients without receiving too much nitrogen or other nutrients that would cause the leaf to have a strong flavour unsuited for commercial cigarettes.[15] An article by Lawrence Niewójt ably assesses the important role of the land and soil in shaping the cultivation of flue-cured tobacco and windbreakers in Norfolk, tying the cultivation of flue-cured tobacco to a long history of landscape change that was shaped and managed by farmer and government intervention. His article draws attention to the dual patterns of tobacco cultivation and forestry but deals more explicitly with people and technology than landscapes.[16] The connection between agriculture and land also integrates the observations of environmental historians who see agricultural landscapes as not simply ‘natural’ or ‘human,’ but as a hybrid landscape not readily distilled back to its human and natural progenitors.[17] When we discuss trees and tobacco as human technologies, we cannot lose sight of the environment’s agency in their deployment. As we will see, while modern capitalism shaped the relationship between trees and tobacco, there remained some elements of the relationship that were not entirely within capitalist logic.

A Brief Sketch of the Norfolk Sand Plain

Figure 1

Southern Ontario, with Haldimand-Norfolk highlighted. Note that the sand plain is predominately in Norfolk, which is the western side of the county.

The Norfolk Sand Plain, covering some 3,150 km² predominantly in Norfolk but stretching into Elgin, Oxford, and Brant, is the remnant of a delta of the glacial Lake Whittlesey, which covered the area approximately 13,000 years ago. Large amounts of coarse Plainfield sand — defined by a variety of landforms from dunes to level plains — and some finer, well-draining sands belonging to the Fox series characterize the region.[18] Soil scientists established these classifications in the 1920s during an Ontario government project.[19] The sand found there bore considerable similarity to the sandy soil in the Piedmont region of North Carolina where flue-cured tobacco farmers worked since the 1890s.[20] Further, the climate of the plain was amenable to tobacco production. To be brought to maturation, tobacco for flue-curing requires approximately 100 to 125 frost free days and warm, bright summers; the region typically provided both of those conditions.[21] Nevertheless, frosts, droughts, and hail offered challenges for farmers; as N.T. Nelson — at one point head of the federal Tobacco Division — noted, between 1933 and 1943, the average yield ranged from 700 to 1400 pounds of tobacco per acre, and weather (including storms, as we shall see) was the chief cause of this wide range in potential crop yields.[22]

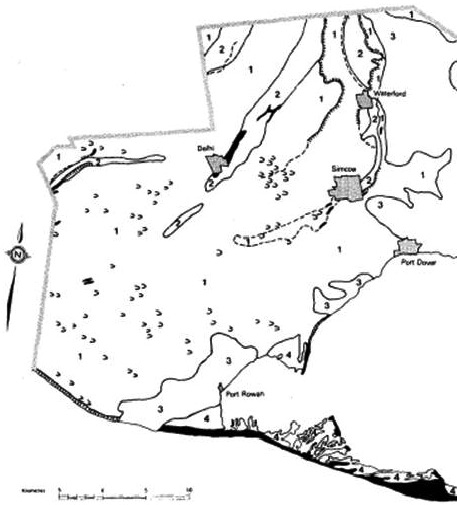

Figure 2

The Norfolk Sand Plain is represented by the number 1 scattered in the map, located just off the shore of Lake Erie and to the north of Long Point.

Before European arrival, the area was part of the Attawandaron (Neutral) territory where these people raised the Nicotiana rustica fundamental to their trade, ceremonies, and position as intermediaries between the Haudenosaunee and the Wendat. The Attawandaron were no longer in the area when British surveyors began to cast their eye over the region in the late eighteenth century, for the Haudenosaunee dispersed them along with the Wendat by 1652.[23] Despite early settler’s impressions of a landscape of largely untouched plains dotted with oak and small pine, the artefacts unearthed by later tobacco farmers revealed that people had indeed occupied the area, beginning a long history of tobacco production.[24] Later accounts of tobacco farmers reclaiming the Norfolk Sand Plain generally (though not always) overlooked this history.

The fine yields from the easily cleared lands pleased early European settlers but by 1815, the thin layer of humus had largely been exhausted. William Pope, a naturalist and artist, described the area in 1834 as “the most miserable poor land I ever saw.”[25] The impoverishment of the soil for agricultural purposes would acquire almost mythical status in the later articles of the 1920s and 1930s that celebrated the role of tobacco farmers in overcoming these challenges. For much of the rest of the nineteenth century, the plain became noted for having a large number of abandoned farms and as a source of wood for the large number of sawmills in Norfolk County.[26] It was this continued forestry work that led to the sand-swept plains catalogued by Zavitz in 1908. While the Norfolk Sand Plain was hardly the only part of Southern Ontario subject to significant deforestation, its barren landscapes were among the most dramatic.

Reforestation

Forestry in Ontario developed considerably over the course of the early twentieth century, contributing to the preservation and expansion of forest cover in the province following a nadir in 1911, when human activity led to the clearance of about 94 percent of upland woodland in southern Ontario.[27] Recently, John Bacher made a lively case for considering Edmund Zavitz’s role in encouraging the revitalization of forests as a sort of Canadian parallel to the conservationist achievements of Gifford Pinchot, the first head of the U.S. Forest Service. Zavitz studied forestry at Yale, attending the school created through Pinchot’s efforts. Mark Kuhlberg’s overview of the Forestry Department at the University of Toronto highlights the complex tapestry of factors that shape the aims of forestry, as foresters find themselves pulled between ecological, economical, and recreational views of the forest.[28] We see the mixture of these factors at play in the early writing on forestry. For instance, in arguing that farmers needed to pay more attention to their woodlots, Zavitz noted, “The price of lumber and fuel and the necessity of providing for the future have caused many in Ontario to think of the question of reforesting denuded lands.”[29] Likewise, his pamphlet arguing for the necessity of planting trees in Southern Ontario wastelands appealed to economic sensibilities, for it devoted considerable space calculating the estimated expenditures and returns on reforestation projects in Norfolk County, while referring to the planting of white pine in South Walsingham Township as an ‘investment.’ In his formulation, the management of forest crops was fundamentally linked to the supply of hardwood for timber in the province.[30] However, Zavitz was also concerned about the aesthetic and recreational value of woodlands, noting that they “should be preserved for the people of Ontario as recreational grounds for all time to come.”[31] The establishment of the hundred-acre nursery on the site of an abandoned farm at St. Williams in 1908, stood as a key achievement of Zavitz’s appeal to both conservation and economics, for it grew into an impressive stand of white and red pine, and functioned as a model for the network of provincially-run forestry stations that gradually expanded in the 1920s, particularly during the United Farmers of Ontario administration led by E.C. Drury.[32]

Figure 3

The ‘wasteland’ in Walsingham Township, Norfolk County.

The reforestation project had a considerable impact on Norfolk. In 1910, Jason Duff, Ontario’s Minister of Agriculture, reported that the department slated some 1300 acres of soil “of a light, sandy nature, unsuitable for agricultural purposes,” for reforestation.[33] Planting proceeded through into the 1920s; the Ontario Department of Agriculture representative for Norfolk, F.C. Paterson, reported in 1927 that pines and evergreen trees were popular for planting on, “of course,” light sandy areas.[34] According to Helen E. Parson, by 1931 Norfolk County had the “highest woodland proportions in Southern Ontario,” for 20 percent of the former farmland was wooded.[35] Today, a trip through the county reveals attractive strands of evergreen forest lined along the concession roads.

Far from being a restoration of a natural landscape, the reforestation of Norfolk was the product of a biotechnological intervention. As the pamphlets and reports on reforestation make clear, foresters and farmers alike selected many of the trees that shape Norfolk today. The exception to this is the Backus Woods, a beautiful stand of forest that the Backus family cut “only modestly” and that contains some trees dating back to the 1700s.[36] Benhard Fernow, the first dean of the University of Toronto’s forestry department, laid out the ambitions that underpinned the biotechnical intervention in a series of lectures given in Kingston in 1903. He asserted in his opening lecture, “The natural forest resource as we find it, consists of an accumulated wood capital lying idle and awaiting the hand of a rational manager to do its duty as a producer of a continuous highest revenue.” As he understood it, the forest was not only a resource for specialists to manage, but also to manipulate and control through the application of technical knowledge. He defined silviculture as, “The technical art of forest crop production … calls for knowledge of botany and especially dendrology … as well as a knowledge of soil physics and chemistry to make the area an improvement on nature’s methods producing the best form and largest quantity of wood in the shortest time possible.”[37] While forestry was slower than other natural fields to delve into sustained exploration of the genetic composition of tree varietals, foresters in North America and Europe had experimented with seeds to determine the relationship between different varieties, in conjunction with soil and climate conditions since the late nineteenth century.[38]

The forestry stations headed by Zavitz followed along these lines, experimenting with methods for selecting and planting particular types of trees and spreading that knowledge to nearby farmers. The stations experimented with varieties of trees to determine the best strains for use in local woodlots and shelter beds. Farmers were encouraged to use woodlands as a source of fuel and income, but Zavitz also impressed the importance of trees acting as windbreakers for orchards and other crops. He recommended the planting of white spruce or Norway spruce for this purpose, using planting techniques similar to those employed for reforesting woodlots.[39] Government- sponsored forestry experiments took a step back during the Great Depression, as both provincial and federal foresters found themselves without jobs following sharp cutbacks. The crisis compelled the University of Toronto’s forestry department to re-orientate towards a ‘practical’ curriculum based on logging.[40] Nevertheless, the development and application of silviculture, paired as it was with an economic imperative, set an important precedent for the deployment of the specialized technical knowledge in managing and reshaping landscapes utilized by growers of flue-cured tobacco, even as foresters deemed that much of the soil that tobacco later grew on as unsuited for agricultural production.

Making the Desert ‘Bloom’: Flue-Cured Tobacco

The first flue-cured tobacco farms emerged in Norfolk County not long after provincial forestry stations expanded in Ontario. The exact origins of flue-cured tobacco in the area are debatable; several sources credit a plantation established in 1923 by Henry A. Freeman and William Pelton as the first in the region.[41] Freeman had previously worked for the federal Tobacco Division, a branch of the Dominion Experimental Farm system that devoted a few stations in Ontario, Québec, and British Columbia to tobacco experimentation. A 1915 Tobacco Division survey reported that the sand plain was suited for flue-cured tobacco, and noted that some tobacco experiments had taken place in the county, though they do not seem to have been particularly successful.[42] Regardless of the precise origin, Norfolk flue-cured tobacco production expanded, overtaking the total tobacco production of Essex and Kent (the so-called ‘Old Belt’ counties) by 1931, in part due to Freeman and Pelton’s efforts, coupled with the interest of Imperial Tobacco buyer Francis Gregory.[43]

Early flue-cured production was closely bound to the formation of plantations that created a system of shares reliant on managers and tenant farmers. For instance, the Norfolk Tobacco Plantations, established in 1927, held 1800 acres and sold shares at one hundred dollars each, with a total market capitalization of $500,000.[44] Many of these tenant farmers were immigrants from Belgium and Hungary who would greatly influence the culture of the region over the decades. While not all tobacco grew on plantations — one estimate held that the percentage of tobacco grown on plantations fell from 40 to 29 percent between 1928 and 1932 — the presence of the capitalized plantations with their managerial structure indicates that capitalism significantly shaped the cultivation of flue-cured tobacco in Norfolk County.[45]

The reclamation of ‘wasteland’ for flue-cured tobacco production became a source for a celebration of (capitalist) human ingenuity and its power to overcome natural obstacles. Henry Freeman and William Pelton featured largely in these accounts. A young John Kenneth Galbraith wrote one such narrative during his last days as a reporter for the St. Thomas Times Journal. Galbraith foregrounded the grave risks and just rewards of the flue-cured pioneers (Pelton and Freeman both became rather wealthy men). According to him, the pair became interested in raising flue-cured tobacco in the area after tests on the Norfolk sand found that it would be eminently suited for that type of tobacco. Galbraith’s paean of their success lauded their ability to use the sand in the face of adversity and scorn: “They bought the farms at a price that did not even represent the value of the buildings thereon, but nevertheless neighbouring residents laughed and said they paid too much. The laughter continued when the men started to build kilns and greenhouses … Probably Messrs. Pelton and Freeman were none too confident themselves, but the disparaging attitude of nearby residents only goaded them on.”[46] The technical knowledge and the capital to build the specialized kilns and greenhouses required for the endeavour played a fundamental role in the story. As another account reveals, Pelton and Freeman also encouraged the use of new technologies, such as kilns and steamers. “Both men had an important role in mechanical and equipment developments down through the years.” The same source monetized the impact of the creation of the flue-cured tobacco landscape, celebrating the fact that land “in the blow sand area of Norfolk County” that they purchased for less than twenty dollars an acre in the late 1920s sold for $1500 an acre 50 years later.[47] By grace of the metrics of real estate, the results of human ingenuity were easily measured.

The narrative of agricultural triumph transcended the annual vagrancies of weather and prices. Of course, there were bad years, punctuated by frost, hail, drought, or miserly buyers. The broad upward trajectory of flue-cured tobacco was likely a cold comfort for a farmer who did not make back their significant capital outlay, which happened to many farmers in the years before the creation of the Ontario Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers’ Marketing Board in 1934. This body brought together farmers and industry buyers (including the Imperial Tobacco Company of Canada) to negotiate an average minimum price for tobacco crops.[48] Even after the creation of the Board and its successor, the Flue-Cured Tobacco Marketing Association of Ontario, risk remained a part of the equation; even a rosy profile of the industry in the Toronto Daily Star written in 1939 described the industry as lucrative, but chancy. Nevertheless, it celebrated the role of farmers who overcame perceptions of Canada as a “land of ice and snow” and were able to find “‘Brown Gold’ in Sandy Fields.”[49] As Lyal Tait, tobacco farmer and first historian of tobacco in Canada pithily summarized, “One-time worthless sand became the highest price soil in the area.”[50] This singular fact mattered more to historical memory of flue-cured tobacco’s impact than did the vicissitudes of annual production.

The creation of this newly enriched region relied on several technological interventions, including experiments with the tobacco plant itself. For instance, in 1935, one tobacco manual listed no fewer than eight different varieties of flue-cured tobacco grown in Ontario, with Bonanza being the most popular.[51] Other widespread varieties included White Stem Orinoco, Virginia Bright, and Yellow Mammoth. The flavour produced by these different varieties of flue-cured leaves was reasonably similar, if cured correctly; agricultural commentators asserted that farmers should base the choice of which variety to use on soil conditions, and whether or not the plant could be readily primed (harvested leaf by leaf). Rigorous testing at the federal experimental farms of Harrow and Delhi assessed the relationship between variety and soil during the 1930s.[52] Farmers abandoned one of the first varieties of tobacco used for flue-curing in Ontario, Warne, because it was said to produce a “heavy-bodied” leaf that was not suitable for the light taste demanded by cigarette manufacturers.[53] While there was concern over classification of tobacco varieties, the industry generally used ‘flue-cured’ as a catchall term that could encompass all of the popular varieties grown. As Barbara Hahn impressed, “tobacco types are essentially the same … Tobacco types are legal distinctions.”[54] Indeed, a key result of the development of different categories for tobacco was less agricultural advancement, and more an enhanced measure to subject the farmer’s tobacco to more stringent grading. The actual efficacy of biotechnological experiments with flue-cured tobacco cultivation is thus questionable, since the many varieties with which the Tobacco Division and the industry experimented were actually genetically almost indistinct. Nevertheless, the fact that tobacco interests sought to select and cultivate particular tobacco varietals in a ‘waste land’ does speak to the general theme of trees and tobacco as technologies.

Chemical fertilizers were another key technology for this transformation. The widespread use of chemical fertilizers, and the elaborate methods employed by both industry and farmers to ensure that they contained the correct mix of nutrients, bears all the hallmarks of modern agriculture.[55] Francis Gregory, the aforementioned Imperial buyer, also sold Ober brand fertilizer as a side business; Ober, based in Baltimore, Maryland, had been selling specialized tobacco fertilizer since the late nineteenth century. Gregory’s interest in fertilizer sales led to some farmer complaints that Imperial treated those who bought his fertilizer preferentially, though this allegation was difficult to prove.[56] In 1930, industry buyers, plantation owners, and state agricultural workers formed the Ontario Tobacco Fertilizer Committee. The committee aimed to bring together expertise from state and industry, drawing on chemical testing of soils and experiments with different ratios of nitrogen, phosphorous, and potassium, and bring that expertise to bear on the practices of farmers.[57] They reached farmers through newspaper announcements and through offers of soil testing.[58] Much as the flue-cured districts of the Piedmont before them, Norfolk farmers became known as prolific purchasers of fertilizer. Using numbers from the 1941 Census, we find that Norfolk farmers spent an average of $234.82 on fertilizer (n=2443), compared to a provincial average of $70.84 a farm.[59] This tendency came across in other reports, and influenced other crops. As the Norfolk Agricultural Representative noted in 1935, “A very great amount of commercial fertilizer is used in Norfolk County on tobacco, orchards, small fruits, vegetables, and increasingly so on farm crops. The Manager of one of the largest fertilizer companies made the statement recently that 20% of all the fertilizer sold in Ontario was used in Norfolk County.”[60] The capital outlay and deployment of chemical fertilizer, following recommendations of a state-industry committee, indicate how deeply modern capitalism penetrated the sand plain.

The creation of the tobacco-yielding sand plain relied on a steady influx of Americans with specialized knowledge. Freeman was from South Carolina, Pelton from Wisconsin. During the late 1920s and into the 1930s, the annual migration of curers from North Carolina and Kentucky — highly specialized workers who ensured that the tobacco in the field dried in the kilns into a bright yellow, pliable, and marketable product — became a key moment in the local calendar.[61] Their work was the capstone of an agricultural regime based on chemical fertilizers and greenhouse raised seedlings. Barbeques celebrating the work and departure of the workers emphasized this fact, as did the wages — curers could make twenty-five to thirty-five dollars a week in 1933 while field workers only made one or two dollars a day.[62] Their work was so fundamental to the success of the Norfolk tobacco crop that the federal government continued to allow them to enter as temporary workers during the height of the Depression, even as the government barred almost all other agricultural labourers.[63] Several hundred curers crossed the border each year; for example, in 1936, 850 curers arrived in Ontario, with many ending up in Norfolk.[64] The annual movement of American curers created a human tie between the Norfolk Sand Plain, the sandy soils of the Piedmont, and the technology and curing techniques developed in that region to construct bright tobacco in the sand.

The Desert Returns

Farming lands previously deemed unsuited for agriculture owing to soil and dryness through use of new techniques and technologies was hardly without precedent in Canada. The driest section of land stretching across southwestern Saskatchewan and southeastern Alberta, known as Palliser’s Triangle, saw a nine-fold expansion in population between 1906 and 1916.[65] The expansion into the dry areas of the Canadian prairie occurred because of demand for land, of course, but it was also a by-product of a sentiment that technology and management, such as summer fallowing and the use of binders, threshers, and steel ploughs could overcome ecological obstacles. As the American dry farming enthusiast John A. Widtsoe enthused, “the desert will be conquered.”[66] David C. Jones poignantly illustrated the ramifications of boosterism in his account of abandoned Carlstadt, Alberta, a town that, in his telling, stood testament to the folly of human vanity and the culpability of the boosters of dry farming. He also casts blame on agricultural experts, people who, in his estimation, should have known better. Recent commentators have added more nuance to this account. John Varty notes that the expansion into the dry areas was also driven by the correlation between the brown chernozemic soil, the lower yields of those soils, and the higher protein content wheat yielded from those soils; for his part, Peter A. Russell argues that since there was hardly consensus among agricultural experts over the best methods for dry farming, there is no homogenous ‘expert’ opinion to blame. Further, Rod Bantjes has argued that many ecological difficulties emerged from the practices of farmers themselves, farmers who were “too modern” in maintaining that a wheat monoculture could be sustained in the dry belt.[67] The dry belt of the prairies serves as an important precedent for the enthusiasms and limits of expert and farmer management of soils previously deemed unsuited for agriculture. Tobacco farmers in the Norfolk Sand Plain faced similar challenges, though they were fortunate not to experience the oppressive droughts that plagued the farmers who lived through the worst Dust Bowl years.

Sandstorms soon came to vex the flue-cured tobacco farmer. A sandstorm striking a farm could be devastating, since farmers relied on having a large leaf without holes to cure and sell — a broken leaf was a junk leaf. Tobacco plants were particularly susceptible to sandstorms during June, not long after they were transplanted into the fields from the greenhouses where they germinated. In 1938, the federal Tobacco Division reported that sandstorms destroyed some 5,000 acres of tobacco and damaged another 5,000 acres. While farmers salvaged some of the crop by planting new seedlings from the greenhouse, losses were substantial.[68] A particularly bad sandstorm hit farmers in June of 1939. An evocative passage in the St. Thomas Times Journal captured the damage, which inverted the narrative of progress: “Fields that flowed over hilly land, with six inch high, waving green tobacco plants Sunday morning were bare as a desert at noon Monday when the blow finally subsided ... The sand shifted like drifting snow.”[69] The need to protect the crops from winds began to occupy the attention of farmers and experts alike, particularly as the decade wore on.[70] As sharecropper, farmer, and plantation owner alike sought to maximize returns from the substantial investment of kilns, greenhouses, and fertilizers, the years of cropping tobacco on sandy soil, often several years in a row, began to take their toll.

The demand for wood engineered by curing flue-cured tobacco further complicated matters. In order to heat the kilns, significant amounts of fuel were required, and wood served as one ready source of fuel. In 1934, agricultural representative G.G. Bramhill reported, “There has been quite a slashing of the woodlots of Norfolk County during the past few years for the purpose of obtaining fuel for tobacco kilns and a vigorous reforestation policy is needed for this County.”[71] Woodlot timber was cheaper than coal or other fuel sources, a particularly important factor during the early Depression prior to the creation of the tobacco boards, when prices were especially low. As was reported in The Simcoe Reformer, fuel costs were difficult to estimate on a countywide basis, because “some operators owning a good wood lot use it for fuel at a very little outlay.”[72] A provincial forestry official, Frank Newman, estimated that tobacco farmers used some 40,000 cords of timber for their kilns, which he feared undid much of the earlier reforestation efforts.[73]

While the rise of the tobacco industry and the declining number of government forestry workers meant that reforestation took a decided back seat in the Norfolk Sand Plain, the effort had not been abandoned altogether, despite the use of woodlots for kiln fuel. For one, all ‘waste land’ had not been converted to agriculture. Under the auspices of the provincial Counties Reforestation Act, Norfolk had some 1,000 acres under a municipal reforestation scheme, and in 1924, the province established a second forest station in the county at Turkey Point.[74] According to another report, foresters planted Carolina Popular trees on sandy soil in low-lying areas, which did not drain well.[75] Zavitz was also able to encourage several landowners in the county to participate in a demonstration woodlot program, and he reported that the St. Williams station remained a popular tourist attraction, which helped strengthen the case for conservation.[76]

As conservation efforts continued in a somewhat diminished form during the Depression, economic appeals functioned as the core method of cajoling the growing number of tobacco farmers to plant trees, such as conifers like Scotch pine and white pine. Approximately five hundred farmers set out some 1.5 million young trees for woodlots and windbreakers in 1935, one of the more extensive planting years of the decade. Many of the young trees came from the provincial forests, connecting the initiative to the program of varietal selection and management. A report from the federal Tobacco Division made it clear that commercial viability shaped this initiative. “Norfolk tobacco farmers are not planting trees as a matter of sentiment. They are planting wind-breaks and woodlots because they believe it pays.”[77] Reforestation advocates like Newman also targeted plantation managers in the hopes that their adoption of planting windbreaks would encourage other farmers. He won a convert in E.C. Scythes, the manager of the extensive Vittoria Plantations, who declared in 1936 that he had “awakened” to the problems of insufficient wind cover and would endeavour to ensure that the plantation had more cover.[78] Henry Fair, who had managed plantations before becoming the owner of the Norfolk Leaf Tobacco Co., also became an advocate for windbreakers. Perhaps he was convinced by Freeman’s anecdote that one farmer told the forestry worker that he saved some $2,000 from his windbreakers (how exactly the farmer arrived at this number remains unclear). During the same meeting when Fair publically called for more tree planting, Freeman reported that some 3 million trees had been distributed to tobacco growing counties, a living testament to the increased popularity of windbreakers.[79]

The directives of the Flue-Cured Tobacco Marketing Association also encouraged tree planting. Large tobacco plantations and managers used their influential position in the Association to pressure smaller farmers to plant windbreaks. The Association, which distributed acreage allowances in an effort to manage supply and enforce quality standards amongst its members, announced in 1938 that planting of windbreakers would be a factor in determining the tobacco acreage allotted to a farmer.[80] One editorial praised this initiative, evoking the memories of the sand plain as a ‘waste land.’ Without tree planting and crop rotation, the editorial argued, “the area in less time than we imagine will become a desert, fit neither for tobacco-growing nor for any other branch of agricultural activity.”[81] Such a sentiment impressed the fact that the nature of the land continued to haunt the people who sought to make the desert bloom. In some contradiction to the idea that the desert could be “conquered,” commentary on the relationship between forest and soil suggests that “manage” might be a more accurate keyword for their views. By virtue of the activities of the forestry stations and the Association, windbreakers became increasingly widespread by the end of the 1930s. However, more work was needed; Tobacco Division worker H. Murwin noted at the end of the decade, “Had we all taken as much interest in windbreakers in the last ten years as we will have to take in the next ten years, we would not have had so much tobacco blowing out of the ground this summer.”[82] We can take the end of the 1930s as a sort of transition; as Niewjót suggests, the various conifers planted as wind breaks continue to exist as visible manifestations of farmer and government activity on the plain.[83]

A Limit to the Focus on Human Technology and Capitalism

The looming threat of the ‘desert’ returning speaks to an element of reforestation not fully captured by the emphasis on trees and tobacco as technology. For one, ‘desert’ can be a moral term as much as a physiological descriptor. Reclaiming land from the desert has Biblical implications; it was the lot of man (and the fault of woman) to make the desert bloom after being cast from Eden. As Carolyn Merchant observes, “The initial lapsarian moment (i.e., the lapse from innocence) is the decline from garden to desert as the first couple is cast from the light of an ordered paradise into a dark, disorderly wasteland.” Capitalism, with its ordering and utilization of nature, was the palliative to the fall, the promise of a restored, usable garden.[84] The emphasis on Eve’s role in the fall obfuscates the fact that women’s work was fundamental to the transformation of the Sand Plain. Likewise, the work of women in the fields and the barns, cultivating and tying the leaves, tended to get lost in narratives of male farmers making the Sand Plain bloom.[85] Nevertheless, using the lens that emphasise religious mission, we find that when a local paper celebrated the fact that tobacco “bloomed like the rose in the desert,” it was doing more than celebrating the economic potential of the crop. It drew on a broader narrative where improvement was a religious imperative, and capitalism, with its concomitant technologies, functioned in the service of this imperative.

Secondly, as the editorial on linking acreage rights to wind breaks makes clear, people were aware that the land itself functioned as an agent that shaped the context. W.H. Porter, of the Farmers’ Advocate, made this point clear when he gave a speech to tobacco growers near Delhi: “You can’t rob the land of its trees and continue to grow tobacco. It is not a political panacea that we need here but to make restitution to the land. We owe it to our land to make such restitution, to give them back some of the forest growth it once had. Go back into your communities and do your bit in saving the trees.”[86] The Ontario government’s tobacco expert, R.J. Stallwood, made a similar point when he argued, “we have been short changing our soils.”[87] These statements point to a space beyond seeing tobacco cultivation in purely instrumental terms. ‘Rob the land,’ ‘making restitution,’ and ‘short changing’ are terms loaded with moral meaning. They are comments that gesture towards seeing the Norfolk Sand Plain and tobacco soils more generally as participants in the cultivation of flue-cured tobacco. They also speak to an anxiety around the stability and the place of rural society in the midst of urbanization, an uncertainty founded upon a tradition that saw mixed farming and soil conservation as fundamentally moral acts because they ensured the long-term stability of rural society.[88] Such comments indicate a certain conviction about the limits of technology, even in this most technological of agricultural areas.

The role of the sandstorms in encouraging the planting of wind breaks also points to how the Norfolk Sand Plain emerged as what environmental historian Mark Fiege has called a ‘hybrid landscape.’ His use of the term developed when he examined the irrigated landscape of the Snake River valley, and argued, “what is human in the irrigated landscape, and what is natural, cannot be easily teased apart, if at all.”[89] This is evident in the Norfolk Sand plain today, where the windbreak trees have also become important habitats for woodland species.[90] Observations like these lead me to part ways to some degree with Barbara Hahn, who very much emphasizes the role of human choices and agency behind the technology of tobacco. As she argued in an essay on sources, “Putting nature so near the center of history has tended to reduce human agency.”[91] However, pitted against the losses farmers suffered during sandstorms or the uncertainty expressed by commentators like Murwin and Stallwood, this reduction seems justified. When we see rhetorical shifts from ‘conquering’ deserts and making them bloom, to arguing that the land needed to be ‘managed’, we see an acknowledgment of the power of the environment in shaping the context in which trees and tobacco operate. Tobacco growing in the Norfolk Sand Plain created a sort of hybrid landscape where the ‘natural’ sand and the climate intersected with human-selected trees and tobacco, and it is this very process that shaped and constrained the deployment of those selected plants.

Conclusion

Regardless of the precise role that environmental agency has in the formation of the Norfolk Sand Plain as a flue-cured tobacco centre, the broad point remains that the trees and tobacco were used as a result of capitalist-orientated and human-developed technologies. Planting them facilitated the creation of a relatively vibrant sector of agriculture in the midst of the Depression. The emphasis on technology allows us to connect the creation of tobacco lands in the Norfolk Sand Plain as part of a flow of ideas and techniques from the tobacco producing regions of the United States, and understand how they were connected to the formation of the modern, capitalist countryside. Encouraging the desert to bloom in Norfolk meant relying on the skill, capital, and chemicals of Americans, who formed human links between the two countries. Casting trees and tobacco as technology has allowed for consideration of the existence of an overlap between the methods and goals of forestry and tobacco cultivation, despite the fact that Edmund Zavitz, representing the former, had deemed the Norfolk Sand Plain to be a ‘wasteland.’ The work of forester Francis Newman, who drew on the insights of forestry conservation and pitch them to tobacco farmers, stands as a useful example of this overlap. The planting of windbreakers had fortunate effects, including the increase in forest cover in the sand plains, which came to mitigate the worst effects of soil erosion. However, these technologies were fundamentally bound to a modern, capitalist context, measured by land values, returns, and a movement towards specialized farming. Such a context both opened and limited space for conservation — ultimately, something valuable needed to bloom.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Mark Kuhlberg and Michael Commito for organizing the CHA panel ‘Blending Boundaries’ that started me thinking about links between forestry and tobacco. I also greatly benefited from helpful comments by Elizabeth Jewett on an earlier draft of this paper, from earlier discussions with the Toronto Environmental History Network, and from the feedback of the anonymous reviewers.

Biographical note

JONATHAN MCQUARRIE is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at the University of Toronto.

Notes

-

[1]

“Annual Report of the Statistics Branch,” Ontario Sessional Papers, Vol. LVX, Part V, No. 22 (1933), 3; ‘Progress of the Canadian Tobacco Crop,’ The Lighter Vol. VIII, no. 3 (July 1938): 6.

-

[2]

‘Southern Tobacco Experts Enthused About Norfolk,’ The Simcoe Reformer (29 September 1932).

-

[3]

See, for instance, “Influx of Transients Presents Problem,” The Tillsonburg News (11 August 1938).

-

[4]

The impact of cigarette smoking on human health will not be addressed directly here; some useful overviews of the topic for North America are found in Rob Cunningham, Smoke and Mirrors: The Canadian Tobacco War (Ottawa: International Development Research Centre, 1996); Allan M. Brandt, The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall, and Deadly Persistence of the Product that Defined America (New York: Basic Books, 2007); Jarrett Rudy, “Unmaking Manly Smokes: Church, State, Governance and the First Anti-Smoking Campaign in Montreal, 1892–1914” in The Real Dope: Social, Legal, and Historical Perspectives on the Regulation of Drugs in Canada, ed. Edgar-André Montigny (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011); and Sharon Anne Cook, Sex, Lies, and Cigarettes: Canadian Women, Smoking, and Visual Culture, 1880–2000 (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2012).

-

[5]

Edmund Zavitz, “Report on the Reforestation of Waste Lands in Southern Ontario,” in Fifty Years of Reforestation in Ontario, Ontario Department of Lands and Forest, (1960), 8.

-

[6]

Ibid., 5.

-

[7]

Mark Kuhlberg, “Ontario’s Nascent Environmentalists: Seeing the Foresters for the Trees in Southern Ontario, 1919–29,” Ontario History Vol. 88, no. 2 (1996): 138.

-

[8]

Char Miller, “A Sylvan Prospect: John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, and Early Twentieth–Century Conservationism,” in American Wilderness: A New History, ed. Michael L. Lewis (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 131–147; Tina Loo, States of Nature: Conserving Canada’s Wildlife in the Twentieth Century (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2006), chpt. 3.

-

[9]

These definitions draw primarily from two articulations of rural modernity: Ronald R. Kline, Consumers in the Country: Technology and Social Change in Rural America (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), 8; and Colin Duncan, The Centrality of Agriculture: Between Humankind and the Rest of Nature (Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1996), 26.

-

[10]

H.R. McMillian’s rapid transition from government forester to head of a major lumber company speaks to this interconnection as powerfully as any example. See Mark Kuhlberg, One Hundred Rings and Counting: Forestry Education and Forestry in Toronto and Canada, 1907–2007 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009), 60–2; Graham D. Taylor and Peter A. Baskerville, A Concise History of Business in Canada (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1994), 306.

-

[11]

Barbara Hahn, Making Tobacco Bright: Creating an American Commodity, 1617– 1937, (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011), 7.

-

[12]

Robert Gardner, “Trees as technology: planting shelterbelts on the Great Plains,” History and Technology Vol. 25, no. 4 (December 2009): 325.

-

[13]

There is a considerable historical literature on this organic industrial innovation, occasionally referred to as ‘Envirotech’, even when confining oneself to works on North America. See, for instance, Susan R. Schrepher and Phillip Scranton, eds., Industrializing Organisms: Introducing Evolutionary History (New York: Routledge, 2004); John Varty, “Growing Bread: Technoscience, Environment, and Modern Wheat at the Dominion Grain Research Laboratory” (Ph.D. diss., Queen’s University, 2006); Alan L. Omstead and Paul W. Rhode, Creating Abundance: Biological Innovation and American Agricultural Development (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008); Jonathan W. Silvertown, An Orchard Invisible: A Natural History of Seeds (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009); Martin Reuss and Stephen H. Cutcliffe, eds., The Illusionary Boundary: Environment and Technology in History (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2010); Margaret E. Derry, Art and Science in Breeding: Creating Better Chickens (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012).

-

[14]

Edmund Russell, “The Garden in the Machine: Towards an Evolutionary History of Technology,” in Industrializing Organisms, eds. Schrepher and Scranton, 7.

-

[15]

Omstead and Rhodes, Creating Abundance, 216.

-

[16]

Lawrence Niewójt, “From waste land to Canada’s tobacco production heartland: Landscape change in Norfolk County, Ontario,” Landscape Research Vol. 32, no. 3 (2007): 355–77.

-

[17]

One of the most influential works that assesses this phenomenon remains Mark Fiege’s Irrigated Eden: The Making of an Agricultural Landscape in the American West (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1999).

-

[18]

L.P. Chapman and D.F. Putnam, The Physiography of Southern Ontario, 3rd ed. (Ontario, Ministry of Natural Resources, 1984), 27, 153–5; Niewójt, “From waste land to Canada’s tobacco production heartland,” 355–8. Fox series soils are defined by their well-drained and rapidly permeable nature, with a Ap horizon (ploughed top soil) of 20 to 25 centimetres underlain by about 20 to 80 centimetres of a sandy or loamy subsoil. Plainfield sand is notable particularly for its low organic content and somewhat high acidity. See E.W. Presant and C.J. Acton, “Soils of the Regional Municipality of Haldimand-Norfolk,” Vol. 1, Report No. 57 of the Ontario Institute of Pedology, Research Branch, Agriculture Canada (Guelph, 1984), 36.

-

[19]

J.A. McKeague, History of Soil Survey in Canada, 1914–1975, (Ottawa, Canada Department of Agriculture, 1978), 10.

-

[20]

Hahn, Making Tobacco Bright, 116–7; Tom Lee, “Southern Appalachia’s Nineteenth-Century Bright Tobacco Boom: Industrialization, Urbanization, and the Culture of Tobacco,” Agricultural History Vol. 88 (Spring 2014): 175–206.

-

[21]

R.J. Stallwood, “Tobacco Topics: Climate Data,” The Tillsonburg News (12 May 1938).

-

[22]

N.T. Nelson, “Tobacco Growing,” The Tillsonburg News (23 December 1943).

-

[23]

While scholars have recently and substantially recast the meaning of dispersal for the Wendat people, pointing to their continuation in other territories, I am unaware of similar work for the Attawandaron at this point. See Abraham Rotstein, “The Mystery of the Neutral Indians,” in Patterns of the Past: Interpreting Ontario’s History, eds. Roger Hall et al. (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1988); Kathyrn Magee Labelle, Dispersed but not Destroyed: A History of the Seventeenth-Century Wendat People, (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2013).

-

[24]

Lyal Tait, The Petun: Tobacco Indians of Canada, (Port Borwell, Ont.: Erie Publishers, 1971), 117; John L. Riley, The Once and Future Great Lakes Country: An Ecological History (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2013), 212–3.

-

[25]

Quoted in Riley, The Once and Future Great Lakes Country, 213. On farm abandonment, see Chapman and Putnam, The Physiography of Southern Ontario, 154–5.

-

[26]

In 1851, Norfolk had one sawmill for every 217 people, compared to the provincial average of one for every 608. J. D. Wood, Making Ontario: Agricultural Colonization and Landscape Re-creation before the Railway, (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000), 6.

-

[27]

Riley, The Once and Future Great Lakes Country, 154.

-

[28]

John Bacher, Two Billion Trees and Counting: The Legacy of Edmund Zavitz (Toronto: Dundurn, 2011); Kuhlberg, One Hundred Rings and Counting.

-

[29]

Edmund Zavitz, “Farm Forestry,” Ontario Department of Agriculture Bulletin No. 155 (February 1907), 19.

-

[30]

Zavitz, “Report on the Reforestation of Wastelands,” 20.

-

[31]

Ibid., 25.

-

[32]

Edmund Zavitz, “Recollections,” (Ontario, Department of Lands and Forests, 1966), 6; Bacher, Two Billion Trees and Counting, 85–8.

-

[33]

“Report of the Minister of Agriculture, for the Year Ending October 31st, 1910,” Ontario Sessional Papers, Vol. LXII, Part VII, No. 26 (1911).

-

[34]

“Annual Report, Norfolk County, 1927–28,” Agricultural Representative Reports, Norfolk County, RG16-66, B266739, Archives Ontario.

-

[35]

Helen E. Parson, “Reforestation of Agricultural Land in Southern Ontario before 1931,” Ontario History Vol. 86, no. 3 (September 1994): 245.

-

[36]

Riley, The Once and Future Great Lakes Country, 192.

-

[37]

B.E. Fenrow, “Lectures on Forestry” (Kingston: The British Whig, 1903), 11 15.

-

[38]

William Boyd and Scott Prudham, “Manufacturing Green Gold: Industrial Tree Improvement and the Power of Heredity in the Postwar United States” in Industrializing Organisms, eds. Schrepher and Scanton, 110–6.

-

[39]

Zavitz, “Farm Forestry,” 29–30.

-

[40]

Kuhlberg, One Hundred Rings and Counting, chpt. 4.

-

[41]

Lyal Tait, Tobacco in Canada (Tillsonburg: Ontario Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers’ Marketing Board, 1967), 68; Niewójt, “From waste land to Canada’s tobacco production heartland,” 363; “The Story of Norfolk’s Flue-Cured Tobacco Industry,” pamphlet from the Delhi Tobacco Museum and Heritage Centre.

-

[42]

“Report from the Tobacco Division for the Year Ending March 31, 1915” (Ottawa: Dominion Experimental Farms, 1916), 1206.

-

[43]

Canada, Dominion Bureau of Statistics, ‘Tobacco Crop Report,’ Monthly Bulletin of Agricultural Statistics Vol. 31, no. 359 (July 1938): 222–6.

-

[44]

“Big Transaction in Tobacco Land,” Leamington Post and News (20 October 1927); advertisement in The Simcoe Reformer (24 November 1927).

-

[45]

J.K. Perrett, ‘Report of Field Work Accomplished During 1932 in Norfolk Tobacco District,’ Agricultural Representative Reports, Norfolk County, RG16-66, B266739, Archives Ontario.

-

[46]

John Kenneth Galbraith, “William L. Pelton was First to Grow Tobacco in Norfolk” in “Does it Pay?,” ed. Jenny Phillips (Dutton, Ont,: Village Crier, 2010), 647.

-

[47]

“The Story of Norfolk’s Flue-Cured Tobacco Industry.”

-

[48]

After the Supreme Court declared the Natural Products Marketing Act, which the Board formed under ultra vires, the Board reorganized as the Flue-Cured Tobacco Marketing Association of Ontario, which largely continued the core activities of the original Board. Tait, Tobacco in Canada, 135–41.

-

[49]

“‘Brown Gold’ in Sandy Fields,” reprinted in The Simcoe Reformer (7 September 1939).

-

[50]

Tait, Tobacco in Canada, 68.

-

[51]

N.A. MacRae, “Tobacco Growing in Canada,” Dominion of Canada, Department of Agriculture, Bulletin No. 176 (Ottawa, 1935), 5.

-

[52]

H. Murwin, “Varieties of Flue-Cured Tobacco,” The Lighter, Vol. III, no. 2 (March 1933): 2–3; “Tobacco Topics: Tobacco Varieties,” Tillsonburg News (14 April 1938).

-

[53]

“Flue-Cured Tobacco,” Tillsonburg News (12 February 1931).

-

[54]

Hahn, Making Tobacco Bright, 6.

-

[55]

On earlier uses of fertilizer in the United States, see Lee, “Southern Appalachia’s Nineteenth-Century Bright Tobacco Boom,” 192.

-

[56]

‘Ober’s Fertilizer,’ Leamington Post and Times (7 February 1924); “Report of the Tobacco Inquiry Committee, March, 1928,” 81-82, RG 17, Vol. 3228, File 164-3-2, Libraries and Archives Canada; Jeffrey Kerr-Ritchie, Freedpeople in the Tobacco South: Virginia 1860–1900, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999), 110–2.

-

[57]

For a summary of the formation of the committee, see Tobacco Division, ‘Report of the Officer in Charge, N.T. Nelson, for the Year 1930’ (Ottawa, 1931), 22–3.

-

[58]

Some farmers did indeed take advantage of this; in 1938, the provincial tobacco expert R.J. Stallwood reported having soil samples from some 350 farms in his lab. “Testing Soils,” Tillsonburg News (17 November 1938).

-

[59]

Dominion Bureau of Statistics, Eighth Census of Canada, 1941: Ontario Census of Agriculture (Ottawa, 1946).

-

[60]

“Annual Report for the Year Ending 1935” Agricultural Representative Reports, Norfolk County, RG16-66, B266739, Archives Ontario. The use of chemical fertilizers in orchards is also in line with the tendency of orchard farmers, who were also heavily capitalized, to enthusiastically adopt new agricultural methods. See Jason Patrick Bennett, “Blossoms and Borders: Cultivating Apples and a Modern Countyside in the Pacific Northwest” (Ph.D. diss., University of Victoria, 2008).

-

[61]

This migration was hardly unique to Norfolk; for instance, American Southerners forged a cultural identity based on their knowledge of tobacco in China. See Nan Enstad, “To Know Tobacco: Southern Identity in China in the Jim Crow Era,” Southern Cultures, Vol. 13, no. 4 (Winter, 2007): 6–23.

-

[62]

J.K Perrett, “Report of Tobacco Field Work Accomplished in 1933 Season in Norfolk District,” Agricultural Representative Reports, Norfolk County, RG16-66, B266739, Archives Ontario.

-

[63]

‘Southern Workers Curtailed,’ Leamington Post and News (26 February 1931); see also ‘Influx of Tobacco Help to be Greatly Curtailed,’ Tillsonburg News (20 February 1931).

-

[64]

“Annual Report for Year Ending March 31st, 1937,” Agricultural Representative Reports, Norfolk County, RG16-66, B266739, Archives Ontario.

-

[65]

Gregory P. Marchildon, “The Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration: Climate Crisis and Federal-Provincial Relations during the Great Depression,” The Canadian Historical Review Vol. 90, no. 2 (June 2009): 280.

-

[66]

Quoted in Peter A. Russell, “The Far-From-Dry Debates: Dry Farming on the Canadian Prairies and the American Great Plains,” Agricultural History Vol. 81, no. 4 (October 2007): 506.

-

[67]

David C. Jones, Empire of Dust: Settling and Abandoning the Prairie Dry Belt, 2nd ed. (Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2002), especially chpt. 8; John F. Varty, “On Protein, Prairie Wheat, and Good Bread: Rationalizing Technologies and the Canadian State, 1912–1935,” The Canadian Historical Review, Vol. 85, no. 4 (2004): 721–53; Rod Bantjes, Improved Earth: Prairie Space as Modern Artefact, 1869–1944 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005); Russell, “The Far-From-Dry Debates.” A similar problem emerged in the light soils of the Palouse region, where farmers tended not to employ soil conservation methods. See Andrew P. Duffin, Plowed Under: Agriculture and Environment in the Palouse (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2007).

-

[68]

“Progress of the Canadian Tobacco Crop,” The Lighter Vol. VIII, no. 3 (July 1938): 5–6.

-

[69]

“Thousands Loss for Tobaccomen in Gale,” St. Thomas Times Journal (13 June 1939).

-

[70]

For other storms, see Bert Hudgins, “Tobacco Growing in Southwestern Ontario,” Economic Geography Vol. 14, no. 3 (July 1938): 227; “Tobacco Damaged by Wind,” Tillsonburg News (1 June 1933); Niewójt, “From waste land to Canada’s production heartland,” 367–8.

-

[71]

“Annual Report Norfolk County, 1933–1934,” Agricultural Representative Reports, Norfolk County, RG16-66, B266739, Archives Ontario.

-

[72]

“Pay Out Millions Annually for Labour and Supplies,” The Simcoe Reformer (26 October 1939).

-

[73]

“Cutting of Young Woodlots Scored at Joint Meeting,” The Simcoe Reformer (24 September 1936).

-

[74]

“Cutting of Young Woodlots Scored at Joint Meeting;” E.J. Zavitz, Fifty Years of Reforestation in Ontario, 1.

-

[75]

“Annual Report, Norfolk County, 1927–1928,” Agricultural Representative Reports, Norfolk County, RG16-66, B266739, Archives Ontario.

-

[76]

Bacher, Two Billion Trees and Counting, 148–50.

-

[77]

“Tree Planting for the Sandy Soils of the Norfolk Tobacco Belt,” The Lighter Vol. VII, no. 3 (July 1937): 1.

-

[78]

“Cutting of Young Woodlots Scored at Joint Meeting.”

-

[79]

“Gathering of Tobacco Men Draws 2,000,” The Simcoe Reformer (27 July 1939).

-

[80]

As Tait notes, the Board was vulnerable to criticisms that it favoured large, well-capitalized growers, and that the relationship between buyer and grower representatives became rather cozy. Tobacco in Canada, 146–7.

-

[81]

“Sane Advice,” Tillsonburg News (28 July 1938).

-

[82]

“Crop Rotation and Soil Rejuvination Tobacco Area Needed,” St. Thomas Times Journal (16 July 1938).

-

[83]

Niewójt, “From waste land to Canada’s production heartland,” 370.

-

[84]

Carolyn Merchant, “Reinventing Eden: Western Culture as a Recovery Narrative” in Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature, ed. William Cronon (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1996). See also Doug Owram, Promise of Eden: The Canadian Expansionist Movement and the Idea of the West (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1980), chpt. 7.

-

[85]

The number of women interviewed for the Delhi Tobacco Belt Project — undertaken by the Multicultural History Society of Ontario — who recalled working in the flue-cured tobacco fields is testament to this fact. See the Multicultural History Society of Ontario Papers, Delhi Tobacco Belt Project Papers, F1405, B440614, Archives Ontario.

-

[86]

“Crop Rotation and Soil Rejuvination Tobacco Area Needed,” St. Thomas Times Journal (16 July 1938).

-

[87]

“Tobacco Topics: Short-Changing Our Soils,” The Tillsonburg News (8 February 1940).

-

[88]

Steven Stoll, Larding the Lean Earth: Soil and Society in Nineteenth-Century America (New York: Hill and Wang, 2002); Bantjes, Improved Earth, chpt. 3.

-

[89]

Fiege, Irrigated Eden, 8–9.

-

[90]

Niewójt, “From waste land to Canada’s production heartland,” 370.

-

[91]

Hahn, Making Tobacco Bright, 226.

Appendices

Note biographique

JONATHAN MCQUARRIE est doctorant au département d’histoire de l’Université de Toronto.

List of figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

The Norfolk Sand Plain is represented by the number 1 scattered in the map, located just off the shore of Lake Erie and to the north of Long Point.

Figure 3