Abstracts

Abstract

The Indo-Pacific concept grew out of a movement to refocus and redefine the Asia-Pacific region to include the Indian Ocean and South Asia, largely as a result of China’s rise. Over the past 10 years, an increasing number of Indo-Pacific strategies have been officially released in the region and beyond. The first question this article tackles is the following: What are the key drivers behind the rise of Indo-Pacific strategies? We argue that Indo-Pacific strategies have become a fast-moving experimenting space for countries searching for adjustment strategies to at least two concurrent deep trends in a changing global order: the great recent shift in the balance of power most vividly characterized by an increasingly assertive China, and the peaking of the liberal globalization experiment and the return of economic security to the fore. We are also concerned with the comparative angle to this question. In particular, how do Indo-Pacific strategies vary among key countries? And finally, how does the Canadian strategy fit within the broader landscape of Indo-Pacific strategies? In answer to these questions, the article develops a typology of existing Indo-Pacific strategies and how they each insert themselves in the current transitionary stage. Finally, we turn to Canada’s own Indo-Pacific strategy and its key features and drivers, including a discussion of Canada’s approach vis-à-vis China. We argue that this represents a touchstone in how Canada is responding to great power shifts and the erosion of the liberal international order.

Keywords:

- Indo-Pacific,

- strategy,

- power transition,

- economic security,

- Canada,

- China,

- Japan

Résumé

Le concept indo-pacifique est né d'un mouvement qui visait à recentrer et redéfinir la région Asie-Pacifique afin d'y inclure l'océan Indien et l'Asie du Sud, en grande partie en raison de la montée en puissance de la Chine. Au cours des dix dernières années, un nombre croissant de stratégies indo-pacifiques ont été officiellement publiées dans la région et au-delà. La première question abordée dans cet article est la suivante : Quels sont les principaux facteurs à l’origine de l'essor des stratégies indo-pacifiques ? Nous soutenons que les stratégies indo-pacifiques sont devenues un espace d'expérimentation en rapide évolution pour les pays à la recherche de stratégies d'ajustement à au moins deux tendances profondes simultanées dans un ordre mondial en mutation : la grande transformation dans l'équilibre des pouvoirs à l’échelle mondiale, caractérisée par une Chine de plus en plus affirmée, et la fin de l'expérience de la mondialisation libérale et le retour de la sécurité économique. Nous nous intéressons également à l'aspect comparatif de cette question. En particulier, comment les stratégies indo-pacifiques varient-elles d'un pays à l'autre ? Enfin, comment la stratégie canadienne s'inscrit-elle dans le paysage plus large des stratégies indo-pacifiques ? En réponse à ces questions, l'article élabore une typologie des stratégies indo-pacifiques existantes et explique comment chacune d'entre elles s'insère dans la phase de transition actuelle. Enfin, nous nous penchons sur la stratégie indo-pacifique du Canada et ses principales caractéristiques, y compris une discussion sur l'approche du Canada vis-à-vis de la Chine. Nous soutenons que cette stratégie représente l'une des pierres angulaires de la réaction du Canada au rééquilibrage mondial des grandes puissances et à l'érosion de l'ordre international libéral.

Mots-clés :

- Indo-Pacifique,

- stratégie,

- rééquilibrage mondial,

- sécurité économique,

- Canada,

- Chine,

- Japon

Article body

01. Introduction

The Indo-Pacific concept grew out of a movement to refocus and redefine the Asia-Pacific region to include the Indian Ocean and South Asia, largely as a result of China’s rise and a subsequent desire to counterbalance China with India in the region. The earliest manifestations of this concept—the undercurrents as it were—can be traced back to India’s Look East (1991) and Act East (2014) policies and continued to ferment through interactions between Japanese, Indian, and Australian foreign and defence policy circles in the late 2000s. Prime Minister Abe's 2007 speech in New Delhi entitled "At the confluence of two oceans" captures the origin of the Indo-Pacific vision quite well, although the context was mainly bilateral at the time. [1] As such, it is at least in part the result of entrepreneurship and innovation from Japan and Prime Minister Abe in particular. The Australian government was one of the first to set out a formal vision for the Indo-Pacific in its 2012 white paper on 'The Asian Century.' Shortly thereafter, in 2015, India published its Maritime Security Strategy, which identified 'the shift from a Euro-Atlantic to an Indo-Pacific worldview and the repositioning of global economic and military power towards Asia' (Ensuring Secure Seas: Indian Maritime Security Strategy, 2015, p.ii).

Still, we really have to wait until 2016-2017, with the formulation of Japan’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) strategy under Prime Minister Abe and the subsequent US adoption of the concept in 2017 during the Trump administration, to see a proliferation of Indo-Pacific strategies (IPS) among most Western nations and nations in the large Indo-Pacific area (except China). The doubling down and rearticulation of a strong U.S. Indo-Pacific approach under President Biden firmly established the dominance of the concept.

The first key questions for the field of global political economy and security studies are these: What explains the rise of Indo-Pacific strategies over the last 5-10 years? What are the key drivers? And what is the aggregate impact on the regional and global order? In terms of causal analysis, does the spread of Indo-Pacific strategies mark the reimposition of realist security calculations over traditional liberal beliefs in the stability of liberal interdependence (Mearsheimer, 2019; Friedberg, 2012)? Does it represent a general balancing strategy by a large group of countries in the region and from the G7 to counter the rise of a new and increasingly assertive potential hegemon (Allison, 2017)? Is it simply the result of the rise of India and the gradual connection of South Asia into larger regional security and economic networks? Or is it rather a case of isomorphic convergence or mimicking by legitimacy-seeking actors in the context of changing incentives generated by the U.S. and allies (Meyer, Boli, Boli, et al., 1997)?

We are also concerned with the comparative angle to those questions. In particular, how do Indo-Pacific strategies vary among key countries, and what explains such differences? Why do some countries articulate the concept of national economic security as part of their Indo-Pacific strategies and others do not? And finally, how does the Canadian strategy fit within the broader landscape of Indo-Pacific strategies?

In this article, we argue that Indo-Pacific strategies have become a fast-moving experimenting space for countries searching for adjustment strategies to at least two concurrent deep trends in a changing global order: the profound recent shift in the balance of power most vividly characterized by an increasingly assertive China, and the peaking of the liberal globalization experiment. In other words, the IPS space has also become a space to rethink the link between power and security on the one hand and the global economy on the other. It is part of the growing securitization and weaponization of interdependence. And it is a space with variable geometry and rapidly changing initiatives, as noted by recent scholars (Goin 2021, Köllner, Patman, and Balazs Kiglics 2021, Martin 2019).

Since this is still an ongoing process , Indo-Pacific strategies tend to articulate unique and partial recognition of both deep trends—that security concerns of various kinds must be addressed, and that liberal interdependence is retrenching. These responses are incomplete and uneven among countries, as policy elites struggle with the process of gradual abandonment of hitherto dominant paradigms. As a consequence, the IPS space is a very dynamic and interactive space, with dynamics of learning, competition, emulation, reaction, and dissonance. Indeed, many countries have updated and adjusted their respective IPS over time.

The broader strategic context on the security side is coherent with debates around the decline of U.S. hegemony (Ikenberry 2018, Mearsheimer 2019, Wolf 2020, Chu and Zheng 2021, Tiberghien 2022) and the emergence of a polycentric world (Acharya 2017). On the economic side, it fits within the trend of weaponization of interdependence (Drezner et al., 2021; Farrell and Newman, 2019; Leonard, 2021), in contrast to the paradigms of liberal international order and interdependence of the last few decades (Ikenberry, 2018, 2011, 2001). To be sure, the pattern of IPS diffusion is part of a tit-for-tat game of institutional innovation in a time of competition for the new global order. In this way, it can be seen as a proximate response to the Belt and Road Initiative by China (after 2013). It is also not the only game in town. In reshaping the mega-regional order and global order, the IPS effort coexists with BRI, RCEP, new security alliances like AUKUS, U.S.-South-Korea-Japan trilateralization, soft security grouping of QUAD, BRICS+, but also G20, EAS-ASEAN, and APEC. The process is chaotic, competitive, and uncertain. Players like India or ASEAN are present in all these games at the same time.

The methodology used involves the qualitative comparison of Indo-Pacific strategies via the analysis of official IPS documents or key speeches considered as significant in the articulation of a country’s Indo-Pacific posture, complemented by interviews with policymakers involved, where possible. We acknowledge that the realm of foreign policy behaviour and narratives is broader, and refer to external elements at times, but the goal here is to evaluate and compare official Indo-Pacific strategies.

It is worth noting that given the fact that this is an ongoing process with fast-moving parts, that governments have not fully wrestled with shifting paradigms yet, that a new equilibrium has not been found, as well as the reality of foreign policy policymaking in different contexts, we observe daylight between published IPS and foreign policy narratives and behaviour. This can also be explained by the fact that the actors involved in the formulation of IPS and the actors involved in the concrete practice of engagement in the region do not overlap perfectly, and also because some time has passed since the publication of various IPS already (and the situation is evolving quickly, or there may have been a change of government).

To help conceptualize how various Indo-Pacific strategies tackle these concurrent global security and economic disruptions, we develop a typology of existing Indo-Pacific strategies. This is a first step in building the foundations for a more systematic study of the rapid rise of Indo-Pacific strategies and how they reflect deeper drivers of geopolitical and geoeconomic transformation.

These questions are particularly relevant for Canada in the wake of the unprecedented release of its IPS in November 2022, after years of preparation. The publication of Canada’s IPS, we argue, is notable in the evolution of Canadian foreign policy. First, the Canadian government has not traditionally published regional foreign policy strategies. This public exercise is the first since the publication of "Canada's International Policy Statement,” presented in April 2005 by Minister Pettigrew under the Martin Liberal government. Second, and given this context, the fact that this rare effort to publicly articulate Canadian policy objectives concerns the Indo-Pacific is particularly striking. Indeed, the Indo-Pacific, despite its political, human, and economic weight, has not historically been seen as a Canadian priority. Finally, in relation to other strategies, we argue that the Canadian strategy presents as a combination of a hard balancing exercise on the traditional security front and a return of security concerns on the economic front to some extent. However, we argue that the Canadian IPS has continued to distinguish itself from the U.S. approach in the Indo-Pacific on this front by retaining support for a more multilateral and inclusive approach to international economic engagement.

The reminder of this article proceeds through three sections. Section 1 introduces our evaluation of the strategic drivers of the “Indo-Pacific turn.” It includes a focus on the concept of geostrategic rebalancing as well as the broader geoeconomic fracture leading to a return of economic security to the fore. Section 2 develops a typology of existing Indo-Pacific strategies and how they each manifest themselves in the current transitionary stage. Part 3 turns to Canada’s own Indo-Pacific strategy and its key features and drivers, including Canada’s focus on China. We argue that this represents a touchstone in how Canada is responding to great power shifts and the erosion of the liberal international order.

02. Deep Drivers of Post-2016 Wave of Indo-Pacific Strategies

We see the formulation and acceleration of Indo-Pacific strategies as adjustment strategies by states to respond to several crises in the Liberal International Order (LIO) that had served countries like Canada well for decades. At the level of power rebalancing and security concerns, the IPS effort is an effort to structurally connect East Asia and South East Asia with South Asia, and for some, East Africa, and possibly parts of the Middle East. The key driver behind this strategy is to constrain China—a counter-hegemonic move—through new partnerships and cross-regional connections. China is now a significant player in all these regions, and its rise has destabilized existing patterns of engagement. As such, at its core, IPS has been primarily driven by security rather than economic considerations. At the same time, we are seeing deep disruptions in the dominant orthodox hyperglobalization paradigm, which has been visibly eroding at least since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. This profound crisis of neoliberal capitalism intersects in important ways with the concurrent geopolitical crisis.

In some countries, there is a deeper acknowledgement of the current crises. But many countries have not fully and realistically expressed the range of challenges they face in the IPS documents we study here. This is why the current batch of IPS is best seen as a transitory responses that express themselves to different degrees along the two axes of profound disruption (security and economic), and that will be followed by other articulations or new iterations in the coming years. We unpack the larger global context below.

2.1 Deep power shifts

Between 2000 and 2022, we have experienced the greatest shift in economic power since the 1850s: a full 22% of global GDP has shifted hands from developed to emerging economies. [2] China alone saw its share go from 4% to 18% (nominal) during this period. Such a shift has a great impact on military capabilities as well. Accompanying this shift are growing pains around the integration of China into the LIO as it turns more authoritarian and confrontational.

Parallel to this, we have witnessed the rise of the Global South as a whole, accompanied by a lack of true understanding of that reality in the West due to the asymmetric perceptions of colonial legacies. Global South countries are increasingly calling for more power-sharing and voice in all global institutions (including the UN and G20), and the U.S. has mostly stalled on such power-sharing since the 2011 deal as part of the G20 in Korea.

This power shift and associated security dilemmas are feeding a dynamic of tit-for-tat securitization that manifests itself in different parts of the global arena. Institutions of global management and global governance are all struggling, and necessary governance innovation is mostly failing at the moment (except in the environmental sphere and, to some extent, the G20). The U.S.-China confrontation is now entrenched at the heart of global governance.

On the security side, two important regional flashpoints have risen in importance to become two of the world’s most pressing security issues: Taiwan and the South China Sea. Of course, the history of both predates the current Indo-Pacific era, but a combination of rising assertiveness on behalf of China and heightened risk perception and political salience in the U.S. have led to heightened tensions. On Taiwan, this has manifested itself as creeping encroachment and grey zone operations on behalf of China (Blanchette and Glaser, 2023; Kardon and Kavanaugh, 2024) and a series of presidential comments marking a departure from long-standing U.S. policy on Taiwan (Wertheim, 2022) and high-level visits on behalf of the U.S. (Haenle and Sher, 2022). Indo-Pacific strategies take note of heightened tensions on these fronts to varying degrees. The U.S. and Canadian strategies both mention Taiwan 8 times, whereas the UK’s integrated defense and foreign policy document “Global Britain in a Competitive Age” does not, for instance. Where tensions around the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea occupy a significant place in Indo-Pacific strategies, as they do for Canada, they provide a central anchor for discussions around the rise of great power competition in the region.

The rise of new security alliances like AUKUS, the elevation of U.S.-South-Korea-Japan defense collaboration, and the rise of soft security groupings such as the QUAD provide a backdrop to Indo-Pacific strategies as countries in the region adjust to the rise of China as a dominant military force in the region.

2.2 Profound Economic Disruptions and Contestation of Neo-Liberal Globalization

On the economic side, the crisis of the Liberal International Order consists of the peaking and contestation of (hyper)globalization, especially in the U.S. and Europe (Lighthizer, 2020, May 11; Irwin, 2020; Rodrik, 2018; King, 2017). Globalization has been defined since the late 1980s as international economic integration encompassing trade, finance, foreign direct investment, bank flows, and digital flows. With such economic integration came increased adjustment pressures on domestic macro- and microeconomic policies and a loss of national autonomy. Hyperglobalization has been used by scholars such as Dani Rodrik to depict the extremely high impact of integrated global market forces on domestic wages, social cohesion, welfare states, and urban-rural gaps. It has been accompanied by rising protest movements and has increasingly fed into support for populist anti-trade parties from both the right and the left.

One way of diagnosing the problem is to say that for the past 40 years or so, choices made around market (de)regulation and (re)distribution of the benefits of globalization created asymmetrical market power relationships and large pockets of discontented citizens. Another way of saying it is that negative externalities of the hyperglobalization experience were left largely to accumulate, whether on the climate front or the inequalities front, and this has led to a backlash that is taking many forms, including the withdrawal of support for globalization at the polls in the United States. As Rodrik explains, “what some decry as protectionism and mercantilism is really a rebalancing toward addressing important national issues such as labor displacement, left-behind regions, the climate transition, and public health” (Rodrik, 2023). Rodrik (2024) argues that globalization simply pushed the logic of global markets too far for society to accept the cost and for the state to accept the security risks. What is needed is an orderly adjustment to address both dimensions. Alas, given the reality of international relations, managing a limited retrenchment from global integration is very hard to do. What is more likely to happen are tit-for-tat measures among states that may go beyond the initial goals of policy-makers.

During the hyper-globalization era, we were not able to resolve the unbalanced outcome engendered by a globalized economy, which led to hyperconcentration of benefits in the hands of a few, fragmented sovereignty in the hands of the state, and more dispersed distribution of costs. Globalization requires cooperation over the rules of the game among systemic powers. To get that licence, governments need domestic support in key countries (especially the U.S.). With the rise of inequality and alienation, especially in the wake of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, these key conditions have become unstuck. Pushed by public opinion, key countries have multiplied protectionist measures that have generated great uncertainty in the global trade and financial system. A key battlefront for this has been the U.S.

Since 2017, the U.S. has increasingly resorted to strong trade and economic measures against China to push back against perceived unfair practices, but also to slow the economic power transition. The IPS can be seen as part of this broader approach that increasingly frames China’s economic rise and economic policy as a security risk that warrants very strong countermeasures. The broadly defined Indo-Pacific strategy and other parallel strategies marshal assets and instruments in the service of politically-defined goals. [3] In the U.S., these goals now include a degree of containment of China. While the language and tools in various IPS deployed by U.S. allies and partners may show some convergence, the actual goals pursued by these countries vary from those of the U.S.

In turn, this growing security dilemma and contestation for the rules of the economic order also play a role in the eroding support for globalization visible particularly in the U.S. and Europe (as analyzed below).

An amplifying force at the moment is the rise of systemic risks (risks threatening the entire global economy, global eco-system, or global order) and existential risks (risks deemed capable of putting human survival in danger), such as climate change, the governance of artificial intelligence (AI), and pandemics. They mostly result from unmanaged connectivity, the imbalanced advancement of the global economy, and the unregulated progress of the technology frontier relative to planetary constraints and the realities of human development. The inability of current global governance mechanisms to generate decisive responses adds to the sense of risk and uncertainty. We also witness an acceleration of competition around green technology and AI, two game-changing industrial revolutions that will shape economic competitiveness and power relations in the coming decades.

These profound economic disruptions are rendered even more intractable because they are happening against the backdrop of the geopolitical shifts mentioned in the previous section. Citizens in North America and Europe increasingly see the excesses of globalization as associated with the rise of China and Chinese reliance on industrial policy and asymmetric economic measures. These dual crises of geopolitics and geoeconomics reinforce each other. The difficulties created by one interfere with any effort to make headway on the other, at the national and global levels.

03. Variety of Indo-Pacific Strategies: Unequal Adjustments to Power and Economic disruptions

3.1 Indo-Pacific strategies as a Geopolitical Rebalancing Device

At a certain level, the Indo-Pacific concept is regional and marks an expansion of the traditional view of an Asia-Pacific space to an Indo-Pacific space. The Indo-Pacific concept embeds deep variations in geographical zones. For example, Japan, Korea, and France include East Africa, but Canada, the U.S., and most other Europeans do not. Despite this variation, the reconfiguration remains driven by political and security calculations in the context of China’s rise. And at its core, the concept is a response to the deep geopolitical shifts that have occurred over the past two decades.

For first-movers such as Japan, Australia, the U.S., and some European countries, the rise of Indo-Pacific strategies marks an implicit acknowledgement that the distribution of power that gave rise to the liberal international order was at a turning point and that strategic adjustments were necessary in order to adjust their exposure in the Indo-Pacific region.

Given the ongoing nature of these shifts and the profound uncertainties that permeate the current tensions, we argue here that the Indo-Pacific strategic “wave” is an intermediary point rather than an end point. The moment translates into a transitory position, an early and imperfect attempt to wrestle with a profound set of transitions that are still ongoing and whose end point remain unknown.

One of the earliest published official policy documents to reference the concept of the Indo-Pacific was Australia’s 2012 white paper, 'The Asian Century', which presented a vision more focused on economic opportunity at the time. But it was Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s government’s 2013 Defence White Paper that redefined the strategic theatre of the Indo-Pacific and became quite explicit about its positioning vis-à-vis China. It stated: "The continued rise of China as a global power, the growing economic and strategic weight of East Asia, and the emergence... of India as a global power are key trends that... are shaping the emergence of the Indo-Pacific as a unique strategic arc" (Defence White Paper, 2013, p. 2).

In the same year, the Indonesian Foreign Minister delivered a speech in Washington, D.C., entitled “An Indonesian Perspective on the Indo-Pacific” (Natalegawa, 2013). In a way that would foreshadow ASEAN’s more restrained posture towards China’s rise, the speech emphasized the importance of connectivity, peace, and stability between the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

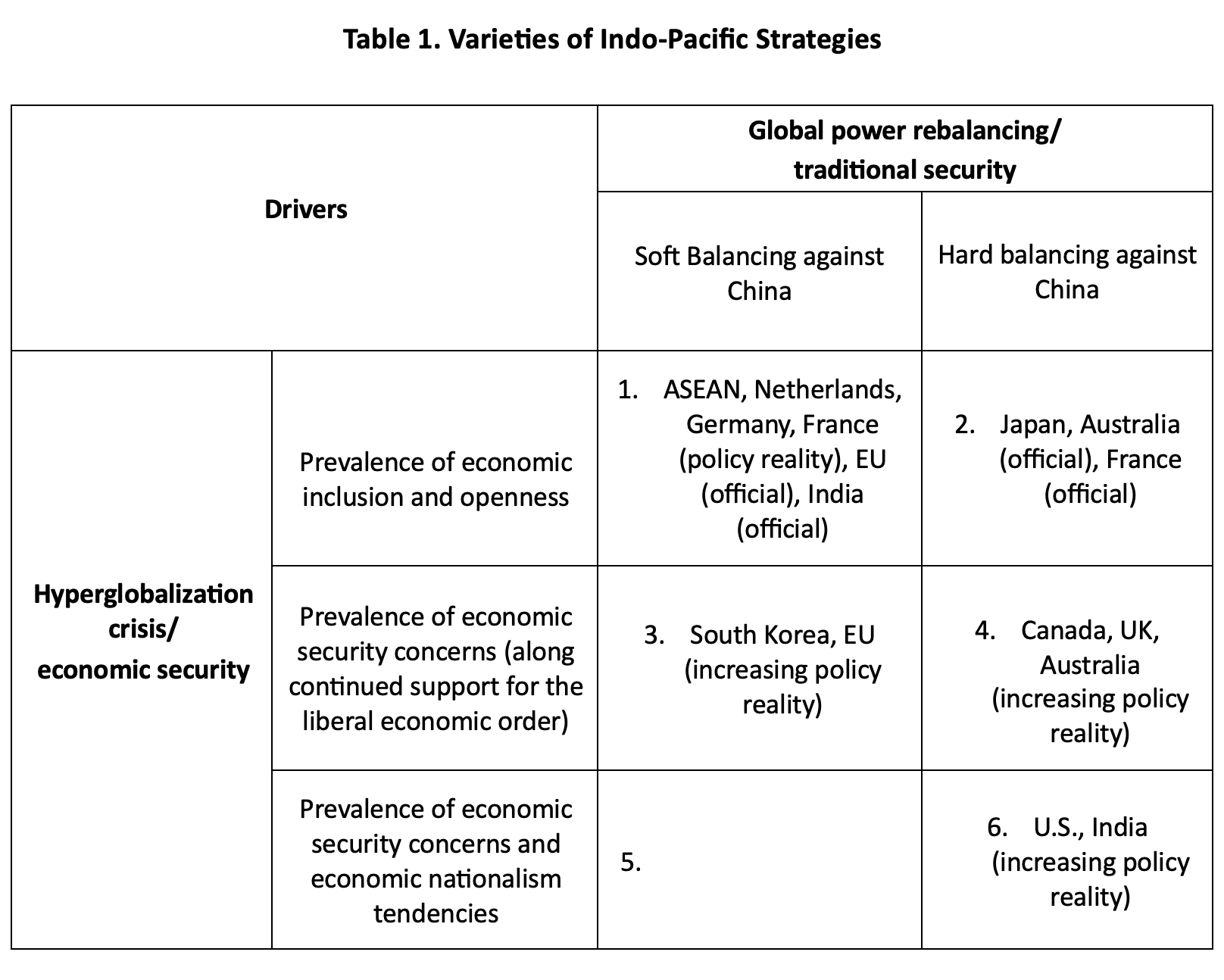

In the typology we develop below (see Table 1.), on the geopolitical and security axis, we identify strategies that are, like ASEAN’s, adopting a more restrained posture towards China’s rise, and maintain a desire, at least on paper, to figure out a way forward that includes an adequate space afforded to China. At the other end, we find strategies that adopt a harder balancing approach towards China, emphasizing the security risks posed and the necessary measures that need to be taken to mitigate these geopolitical changes in order to preserve the status quo.

3.2 The Rise of Economic Security

The other substantive driver of the emergence of the Indo-Pacific concept and wave of Indo-Pacific strategies we have seen over the past decade goes to the heart of the global political economy paradigm shifts we described above. China’s rise is a key element of both deep shifts we identify as key drivers in this article—the geopolitical or security shift and the geoeconomic or economic security shift—but it does not subsume all of them.

The centrality of the Chinese economy in the world economy is a recent feature of the post-1995 and especially post-2001 world (when China joined the WTO). As a result of massive foreign investment in China since the mid-1990s and large outward Chinese investments since the mid-2000s, China has built a formidable position at the heart of global supply chains. This was not so much the result of specific country strategies but more the result of Chinese state-driven developmental economic policies, coupled with the decentralized strategies of multi-national corporations in their search for efficiency and profitability. But as we described above, China’s rise is a key component but not the only component of the deep economic disruptions experienced at the global level since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. The crisis of hyperglobalization has roots that go deep into the economic models of the developed world.

Given the nature of these economic disruptions and the speed at which they have evolved over the past 5 years, it is to be expected that Indo-Pacific strategies will only imperfectly take stock and handle this paradigm shift. This is especially evident for strategies that were published earlier. The more recent strategies, such as South Korea’s “Strategy for a Free, Peaceful, and Prosperous Indo-Pacific Region,” published in December 2022, have more candidly addressed it.

To be clear, most IPS embed at minimum an emerging discussion of the topic, if not an explicit discussion of economic security. The UK foreign policy, security, and development integrated review published in 2021, which contains the UK’s Indo-Pacific “Tilt,” does squarely address these challenges: “Liberal democracies must do more to prove the benefits of openness – free and fair trade, the flow of capital and knowledge – to populations that have grown sceptical about its merits or been inadequately protected in the past from the downsides of globalisation. This means tackling the priority issues–health, security, economic well-being, and the environment – that matter most to our citizens in their everyday lives” (Global Britain in a Competitive Age, 2021, p. 12). While the South Korean strategy also has one of the most explicit sections on economic security and Japan has its own separate law on the topic (2021), the U.S.-led Indo-Pacific Economic Forum (IPEF) launched in 2022 specifically encompasses a significant dimension of economic security, even though the fair and resilient trade pillar eventually faltered (Murphy 2023). It is worth noting that the G7 nations made a detailed statement on the concept at the May 2023 Hiroshima G7 meeting. [4]

Nevertheless, for many strategies, we detect a dissonance between the language adopted in official documents and the rapidly evolving global reality. For instance, most strategies continue to use “open markets” or “free-trade” frames, despite the general retreat of globalization and the re-emergence of economic nationalism and industrial policies, including via the de-risking paradigm (Speech by President von der Leyen, 2023). This leads to the paradoxical situation where, for instance, the U.S. strategy mentions that the U.S. government will continue to “promote free, fair, and open trade and investment” (Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United States, 2022), while at the same time, the Biden administration was signing the Inflation Reduction Act into law (in August 2022), an act that many have argued contains provisions that run counter to WTO principles (Scheinert, 2023).

In many cases, the concept of economic security is a hybrid one. It is about securing key nodes, strategic economic supply chains, and technologies with potential dual military use while still operating within a globalized and deeply interconnected economy. It is about selected state intervention and partial disconnection (“fencing”). It requires a dialogue between security experts and political economy experts, and it remains a work in progress. For Canada, even though the country is well endowed with energy resources, geography, and access to the U.S. market, the concept of national economic security is still an uncomfortable space. Another dimension of economic security relates to pushing back against economic coercion, a plight endured by Canada in the wake of the arrest of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou in December 2018 on a U.S. extradition request.

On the economic security front, all G7 countries’ IPS, as well as the Australian and South Korean strategies, contain a simple feature. They all try to reduce their high dependence on the Chinese economy for aggregate trade, but also critical technologies, medical supplies, and critical minerals in the green transition. In the post-pandemic world and the more securitized environment of the current U.S.-China competition, most IPS seek to diversify trade toward other parts of Asia, especially Southeast Asia and South Asia. That includes Canada’s own approach.

In the typology we present below, on the economic security front, we distinguish between strategies that tackle issues of economic security and economic vulnerabilities while recognizing the need for continued multilateralism, global trade, and openness and those that recognize those same issues and take a more explicitly economic nationalist perspective (for instance, the U.S.).

3.3 Varieties of Indo-Pacific Strategies

The realm of Indo-Pacific strategies is an interactive environment, as the moves taken by one country in the name of economic security, for instance, have a negative security impact on others, and this can lead to a reaction. It is not an equilibrium. It is a dynamic process driven more by geopolitics and domestic politics than any global script or global set of rules. Despite similar inspiration and a degree of convergence, we can distinguish significant variations among Indo-Pacific strategies . Two dimensions are particularly salient: the degree of focus of the IPS on security-driven balancing against (or even the containing of) China and the degree of emphasis on economic security as opposed to a more liberal concepts of multilateralism, inclusivity, and openness.

We propose six clusters or types (see Table 1.) based on these two variables. Admittedly, all countries are positioned on a spectrum of positions rather than in clear categories. To make matters more complex, some countries remain relatively generic and open in their official IPS but more security-focused in the reality of their policies (the cases of Japan and India, in particular). In other cases, there can be officials that deploy very strong economic security language and others that continue to support open economic relations (Canada). Therefore, we present this table as a broad evaluation, taking into consideration primarily the official wording of the strategy and to a secondary degree only, the policy reality. Positions are evolving fast.

Figure

Type 1 groups Indo-Pacific strategies that, on the economic security side, have continued to focus on prosperity, development, public goods, and inclusiveness and refrain from taking a markedly protectionist approach to current global economic challenges. On the security side, these approaches tend to minimize security considerations and adopt a more conciliatory approach towards China. It is exemplified by ASEAN’s strategic vision document (ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific, 2019). To some extent, the EU vision (The EU strategy for cooperation in the Indo-Pacific, 2021), along with German and Dutch strategies (Policy Guidelines for the Indo-Pacific: Germany-Europe-Asia Shaping the 21st Century Together, 2020; Indo-Pacific: Guidelines for Strengthening Dutch and EU Cooperation with Partners in Asia, 2020), fit in this category as well. The EU strategy came together among advisers that sit outside of the traditional security establishment, and it is heavily tilted toward inclusivity pillars [5] . Six out of seven of its key pillars concern the provision of global public goods and are drafted in an inclusive language: sustainable and inclusive prosperity, green transition, ocean governance (with a mention of UNCLOS), digital governance and partnerships, digital connectivity, and human security, while there is one security and defence pillar (which emphasizes “open and rules-based regional security architecture”) (EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific, 2022).

We include in this category the 2021 French IPS (France’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, 2022). The document itself carves a sizeable place to the French government’s military presence in the region, but it is framed as a “contribution to regional security and stability” (p. 24) and “on the path of multilateral cooperation based on law and respectful of all sovereignties.” (p. 5), with a particular focus on cooperation with ASEAN. Recent positions taken by President Macron (Anderlini and Caulcutt, 2023) indicate a strategic desire for an autonomous, comprehensive approach that is not driven by strict security competition led by the U.S. These remarks are in line with the broader EU approach outlined above (even if the EU has indicated its intentions to take a stronger policy course on economic security in recent months). That said, because of the gap between the more security-oriented IPS document and the more balanced policy reality pursued by the President, we include France in two boxes (official Indo-Pacific strategy vs. policy reality).

One may include here India’s IPS, as enunciated in two key milestones we are relying on in this instance. The first one is Prime Minister Modi’s Shangri-La Speech in June 2018 (H.E. Modi, 2018), and the second one is his subsequent speech at the East Asia Summit held in Bangkok in November 2019 entitled Indo-Pacific Oceans’ Initiative (IPOI) (H.E. Modi, 2019). India’s IPS has emerged from its earlier “Act East” strategy and has emphasized in these speeches the concepts of inclusivity, openness, and adherence to “a common rules-based order.” Prime Minister Modi’s 2018 speech centers around seven elements: a free, open, and inclusive region; ASEAN centrality; a rules-based order; the Blue Economy; an open trading regime; connectivity; and cooperation. Based on the text of these key speeches, we classify India here alongside other more “inclusive” and “globalist” approaches, such as that from the EU. Prime Minister Modi explains in his 2018 speech that “all of this is possible if we do not return to the age of great-power rivalries. I have said this before: an Asia of rivalry will hold us all back; an Asia of cooperation will shape this century.” (H.E. Modi, 2018). As in other cases, however, we would be remiss to omit the daylight that is present between the language of the two documents and some of the Indian government’s behaviour in the region. Among other things, after the border clash with China in Spring 2020, India has accentuated its security cooperation with the U.S., Japan, and Australia (QUAD members) while keeping the general broad IPS approach. In addition, despite the lofty rhetoric, the Indian government did in the end opt-out of RCEP (in late 2019).

Type 2 covers strategies that, while squarely addressing the China challenge, embed both security-inspired deterrence and avenues of cooperation with China on the public goods and economic fronts. These strategies are ambitious, covering legal, security, economic, development, and environmental pillars.

The best example of this cluster is Japan’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific approach. Japan played a key role in the formulation and dissemination of the Indo-Pacific concept, starting in 2007 with Prime Minister Abe's "At the confluence of two oceans" speech. The Japanese strategy was formally launched in 2016 with Prime Minister Abe’s speech on Japan’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) at the Sixth Tokyo International Conference on African Development in Kenya. As this became one of the top priorities of Prime Minister Abe, he pursued it systematically and relentlessly, including with the Trump and Biden administrations. Japan’s FOIP strategy has undergone multiple additions and enhancements since 2016. It is also very sophisticated, with complex maps of priority corridors . The strategy does include an emphasis on inclusiveness as a positive nod to ASEAN, and the language remains restrained. For instance, the 2016 speech does not mention China at all. Of course, “FOIP was presented as a broad concept with inclusive emphasis, not a strategy against China. The door was open to all. But the reality was a bit different, it was our counterargument to BRI.” [6]

For Japan, the concept encompasses two pillars meant to push back against China’s challenges to the rules-based order (maritime rule of law related to UNCLOS and security), while the economic pillar keeps the door open for cooperation with China, including on development projects. Admittedly, however, while China and Japan had very positive discussions on the possible partnership of FOIP and Belt and Road in 2019 on the margins of the Osaka G20, such cooperative partnerships have mostly failed to materialize so far. [7] Japan’s FOIP strategy also has a large focus on security partnerships such as the Quad and is big on quality infrastructure investment in the region (rivaling China’s).

Under Prime Minister Kishida (October 2021-present), Japan has gradually emphasized the security dimensions of FOIP. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Japan has seen its security policy increasingly aligned with that of G7 and NATO countries. Japan has committed to doubling its defense budget as a percentage of GDP (from 1% to 2%) over a 5-year period (2022-2027), which represents the most dramatic transformation of Japan’s military posture since the 1950s. Japan has also taken more and more direct positions in favor of the defense of Taiwan and the Philippines. However, the Japanese economy remains deeply interconnected with the Chinese economy, and economic officials have continued to work on routine economic engagement with China. The trilateral summit between China, Japan, and Korea in Seoul in May 2024 is a marker of quiet continuity of economic interdependence in parallel to the security hardening. This is why we keep Japan in the Type 2 group at this time.

In March 2023, in the lead-up to the G7 Summit in Hiroshima, Prime Minister Kishida announced an improved version of FOIP in the context of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and other global changes (Prime Minister Kishida, 2023). The new FOIP retains the same spirit and vision but now includes four pillars. The rule of law (pillar 1, now called “principles for peace and rules for prosperity,” including IPEF, WTO and CPTPP) and security pillars (pillar 4) are retained and expanded. But the former second economic pillar is now split into two broader pillars: addressing [global] challenges in an Indo-Pacific way (pillar 2) and multi-layered connectivity (pillar 3).

Type 3 includes strategies that, while adopting a softer balancing approach towards China’s rise on the traditional security side, have given a prevalence to economic security concerns. The South Korean IPS would fit here as a targeted, innovative conceptualization of international economic relations and national economic security. South Korea’s IPS is structured around the new vision of Korea as a global pivotal state with the duty and capability to invest in shaping outcomes and processes in the region and with the willingness to invest significant resources. On the security front, the South Korean strategy frames its relationship with China in the following way: “With China, a key partner for achieving prosperity and peace in the Indo-Pacific region, we will nurture a sounder and more mature relationship as we pursue shared interests based on mutual respect and reciprocity, guided by international norms and rules.” (Stategy for a Free, Peaceful, and Prosperous Indo-Pacific Region, 2022). Here, it is important to note that whereas the Korean document fits under a softer balancing approach, President Yoon has been leaning into a harder balancing narrative in various speeches. On the economic front, the South Korean strategy is more explicit than most: “We will participate actively in multilateral cooperation to establish an early warning system and resilient supply chains of key industries and items. We will also increase bilateral and minilateral communication and cooperation to diversify our economic ties and ensure stable supply chains. In order to stabilize supply chains of strategic resources, we will seek cooperation with partners with whom we share values.” (p.30) It is important to note that the South Korean strategy states that it does not want to let security concerns overwhelm economic decision-making, especially when it comes to global public goods: “While helping to build stable and resilient supply chains, we will take the lead in promoting a free and fair economic order. We will also work with other countries to ensure that security concerns do not trump economic issues” (Stategy for a Free, Peaceful and Prosperous Indo-Pacific Region, 2022, p. 10).

Type 4 represents strategies that are driven by both national security priorities and the securitization of economic concerns. The Canadian IPS fits here, as it presents harder-balancing language against China and includes a vigorous security pillar. The document includes multiple instances of discussion of economic security issues, for instance: “Emerging patterns of protectionism and economic coercion are of significant concern to Canada.” (p.16). At the same time, it is balanced by remaining elements of a commitment to global trade: “new and existing trade and investment agreements” (p. 16), support for global public goods discourse, and engagement, especially with regards to development or global environmental priorities. We cover the Canadian case more in depth in the final section below.

In 2021, the UK published a foreign policy, defense and development review, “Global Britain in a Competitive Age: Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy,” which contained a section entitled “The Indo-Pacific tilt: a framework.” In it, the UK also uses sharp language to describe the evolving strategic environment and the role of China in it as one that will be “defined by: geopolitical and geoeconomic shifts, such as China’s increasing international assertiveness and the growing importance of the Indo-Pacific; systemic competition, including between states, and between democratic and authoritarian values and systems of government” (p. 17). On the economic security front, the document had this to say: “China also presents the biggest state-based threat to the UK’s economic security.” (p. 62).

However, the UK document continues to refer to international trade agreements, including the CPTPP, and the importance of supporting the WTO. This is why the Canadian and UK cases do not rise to the level of Type 6, which sees a more marked departure from commitment to multilateralism and global trade.

Finally, Type 6 includes cases that have shown the highest level of strategic balancing against China, as well as the prevalence of economic security concerns accompanied by a higher degree of economic nationalism (including a lack of commitment to trade agreements and economic multilateralism), in this case the U.S. strategy (2022). The goal of building allied partnerships to constrain or contain the Chinese threat is stated more explicitly. The emphasis is on deterrence, new rules that constrain China, extended security, and diplomatic presence and a heightened focus on the securitization of economic relations. For instance, the U.S. strategy limits economic cooperation ambitions with like-minded partners: “We will also stand shoulder-to-shoulder with regional economic partners who are playing leading roles in setting rules that govern 21st-century economic activity” (p. 12). It is important to note that the U.S. strategy continues to include some language that reflects legacy liberal principles, such as references to open markets and free trade, but the momentum and funding are targeting security-driven dimensions and the securitization of certain economic relationships. The U.S.’s 2022 IPS articulates certainly the most forceful diagnostic of China’s intent and behaviour internationally among existing Indo-Pacific strategies: “The PRC’s coercion and aggression spans the globe, but it is most acute in the Indo-Pacific. From the economic coercion of Australia to the conflict along the Line of Actual Control with India to the growing pressure on Taiwan and bullying of neighbors in the East and South China Seas, our allies and partners in the region bear much of the cost of the PRC’s harmful behavior. In the process, the PRC is also undermining human rights and international law, including freedom of navigation, as well as other principles that have brought stability and prosperity to the Indo-Pacific.” (p.5). The document also puts forward an assertive U.S. security posture in the region: “The United States is enhancing our capabilities to defend our interests as well as to deter aggression and to counter coercion against U.S. territory and our allies and partners. Integrated deterrence will be the cornerstone of our approach. We will more tightly integrate our efforts across warfighting domains and the spectrum of conflict to ensure that the United States, alongside our allies and partners, can dissuade or defeat aggression in any form or domain.” (p.12).

04. Making Sense of the Canadian Indo-Pacific Strategy

The Canadian Indo-Pacific strategy of November 2022 represents the culmination of a multi-year process and is also a tipping point in the approach to the region (Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, 2022). It was eagerly awaited, as the government had formally announced the intention to publish such a strategy in Foreign Minister Joly’s mandate letter, following her appointment in 2021. None of the mandate letters of preceding Trudeau government ministers since 2015 contained any mention of the Indo-Pacific region. The letter, issued in December 2021, explicitly mentioned the mandate to "develop and implement a new comprehensive Indo-Pacific strategy to strengthen diplomatic, economic and defence partnerships and international assistance in the region” (Minister of Foreign Affairs Mandate Letter, 2021).

Canada’s IPS is also a response to changing global geopolitical realities and is the first strategic effort on behalf of the Canadian government to respond to these emerging dislocations at the level of strategic foreign policy. It comes with $2.3B in immediate funding commitments, new programs, and initiatives spread across 17 departments and agencies. The intended message is: Canada is in the Indo-Pacific area to be a full-spectrum stakeholder and reliable partner. Government leaders have indicated a new level of ambition and sustained presence in the region. Several features stand out.

First, the Canadian strategy arguably represents a real effort at strategic thinking, that is, an effort to address the challenges of the 21st century over the medium term and to provide tools for Canada to adapt to them—and perhaps even to shape them. It is the only regional strategy officially published by the Canadian government since 2015 (these documents are rare occurrences in the Canadian context). Like South Korea, Canada identifies economic security as a new strategic driver in the region. Like the U.S., Canada identifies China as a key strategic challenge and “an increasingly disruptive global power” (p. 7). The Canadian IPS states that “China’s assertive pursuit of its economic and security interests, advancement of unilateral claims, foreign interference, and increasingly coercive treatment of other countries and economies have significant implications in the region, in Canada, and around the world.” (p. 3), but it also situates the China challenge amongst a series of other strategic issues, including “instability on the Korean Peninsula as a result of North Korean provocations; rising violence in Myanmar following the recent military coup d’état; clashes on the India-China and India-Pakistan borders” (p. 3).

Like the EU, Canada highlights the importance of global public goods and continued cooperation (even) “with China to find solutions to global issues such as climate change, biodiversity loss, global health and nuclear proliferation.” (p. 7) Like Japan’s, the Canadian IPS seeks to combine credible security deterrence and lower economic risks with some investment in the stability of the global system.

It is a broad-spectrum strategy across 5 domains (security, trade, human connectivity, environment, and partnerships) and all sub-regions. The 5 overarching strategic objectives are:

-

A/ Promote peace, resilience, and security. It is an explicit choice here by the government to emphasize that stability is the condition for prosperity. This includes a sizeable commitment of over $500 million over 5 years to defense contributions, naval presence, and military capacity-building; national security enhancements; and cyber security.

-

B/ Expand trade, investment, and supply chain resilience. On this front, the strategy recognizes at once the importance of the continued diversification of Canada’s trading relationships as well as the strategic competition now underlying the future of trade and technology developments. An openness to trade agreements and rules-based global economic interaction remains firmly rooted (which distinguishes the strategy from its U.S. counterpart), while an emphasis on the resilience of global supply chains is given a lot of space, including on the subject of critical minerals.

-

C/ Invest in and connect people. This objective centers around the facilitation of human connections between the region and Canada, whether it concerns visa capacity increases, increasing Canada’s international student programs from the region (and 1000 scholarships), and deepening expertise. It includes a commitment to feminist international assistance and human rights.

-

D/ Build a sustainable and green future. On the global fight against climate change, this objective supports a transition to a green future, including via a major investment of $750 million in sustainable infrastructure through FinDev Canada (which will support the development of clean infrastructure and technologies).

-

E/ Canada as an active and engaged partner in the Indo-Pacific. Finally, this objective seeks to position Canada as a more reliable partner in the region. This includes the appointment of a special envoy to the Indo-Pacific, increasing the country’s diplomatic presence in the region, including via a new mission in Fiji. The Government of Canada subsequently came to an agreement with the Member States of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to establish a Strategic Partnership between Canada and ASEAN (Prime Minister of Canada, 2023).

The Canadian strategy intends to be a collaborative one. It focuses on working with partners, whether Japan, South Korea, the U.S., Australia, or New Zealand on security issues; ASEAN for green infrastructure, trade, or development; or the Pacific Islands for development, human security, and climate change dimensions. In this context, the Canadian strategy is acutely aware of a developing zero-sum game dynamic. Southeast Asia (and even South Asia) feels pushed in the direction of making a choice. Canada is not asking these countries to make a choice. It recognizes that “key regional actors have complex and deeply intertwined relationships with China. Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy is informed by its clear-eyed understanding of this global China.” (p.7). In the IPS, Canada seeks to develop relationships and offer new opportunities for cooperation to partners. The strategy actually embeds specific articulations of its strategy when it comes to China, India, ASEAN, and the North Pacific.

When it comes to the two areas of global disruptions covered in this article, on the economic front, the strategy is coming to grips with the securitization of economic ties and the de-risking paradigm. Like South Korea, Canada’s IPS discusses national economic security, specifically through the lens of competition (including standards), diversification, and global supply chains’ resilience, most notably when it comes to securing critical technologies (including semi-conductors) and the critical inputs for green technologies, chiefly critical minerals.

Nevertheless, for a country such as Canada that is deeply committed to the liberal international order, concepts like economic security, industrial policy, and security-driven economic alliances represent an uncomfortable space. Canadian economic and policy elites still hold the belief that the liberal order can be repaired, and many see the IPS as a complement or a patch to continuing liberal policies. The Bretton Woods era of the 1950s-1960s may have involved a stronger role for the state and stronger recognition of national economic sovereignty, but that era is largely forgotten in Canada. Since the end of the Cold War and the 1990s, the dominant paradigm in Canada has coalesced around a strong support for Francis Fukuyama’s “end of history” exposition (Fukuyama, 1992), support for Bretton Woods institutions, including the WTO, and low political support for state guidance of the economy (with exceptions in the health care space). Traditionally, Canada has had to worry about overreliance on the U.S. (a reality that became all too painful when President Trump threatened Canada of “ruination” in 2018 if Canada did not accept to revamp NAFTA to benefit the U.S. more) (Brewster, 2018). Since the settlement of the USMCA and the Covid-19 pandemic, Canadian fears have shifted to China and its dominant position in global supply chains.

So, on the economic front, the Canadian strategy remains at a point of transition. While committing to adjustments seen as necessary from the perspective of de-risking or economic resilience, it remains wedded to a liberal conceptualization of the global economy, multilateralism, open markets, and free trade. However, given the relentless acceleration of industrial policy measures in China, but also in the U.S., Japan, South Korea, Southeast Asia, and gradually in Europe, Canada is also shifting its discourse as we speak. We already see the precursors of such a future policy through subsidy programs for investments by allies such as Korea, Japan, and Germany in batteries, EVs, and technology.

Finally, one of the distinctive aspects of the Canadian strategy is the space it allocates to China in the text. Indeed, the Canadian strategy is one of the only ones (if not the only one) in the world to include a standalone section on China. In the 23- page document, the China section is over 2 pages long, the longest section allocated to any country or group of countries in the text. The publication of Canada's Indo-Pacific strategy marks a turning point in its approach to China. Indeed, the strategy embeds a recalibrated “realistic and clear-eyed assessment of today’s China” (p. 7). As mentioned above, it labels China “an increasingly disruptive global power,” a tone that marked a departure from earlier characterisations. The strategy goes on to say that “China’s rise, enabled by the same international rules and norms that it now increasingly disregards, has had an enormous impact on the Indo-Pacific, and it has ambitions to become the leading power in the region. (…) For the Canadian government, China is looking to shape the international order into a more permissive environment for interests and values that increasingly depart from ours.” (p. 7) This language is the most forceful recognition to date on behalf of the Canadian government of the profound strategic rift that has opened between China and the West.

Importantly, however, in the strategy, the official Canadian discourse on China also employs a level of complexity, a certain transversality even, that did not exist to the same degree before. First, the government’s characterisation of the relationship has broadened, from the traditionally predominantly bilateral lens to a wider aperture. The Canadian IPS explicitly conceptualises Canada-China relations through a four-dimensional prism, from the national level to the bilateral, regional, and multilateral levels.

In addition, the Canadian strategy emphasises the global (as opposed to the bilateral) nature of most of the challenges that are brought to the fore by China’s rise. Indeed, the strategy mentions that “Canada will work closely with its partners to face the complex realities of China’s global impact and continue to invest in international governance and institutions.” (p.8) This recognition leads the government to articulate a modular approach to China, more affirmative in areas of deeper strategic rift and more open in areas where global cooperation is necessary: “In areas of profound disagreement, we will challenge China, including when it engages in coercive behaviour—economic or otherwise—ignores human rights obligations or undermines our national security interests and those of partners in the region. (…) We will cooperate with China to find solutions to global issues such as climate change, biodiversity loss, global health and nuclear proliferation” (p. 7).

So, while signifying a shift in approach and a harder line towards China, the Canadian approach to China falls within a broader framework based on the continued commitment to international rules of the game, including on the trade front (see the Ottawa Group on WTO reform), a commitment to a stable and open global economic system, necessitating the continued functioning of multilateral groups such as the G20 or APEC, and, therefore, China’s continued role in them. The Canadian IPS states that “China’s sheer size and influence makes cooperation necessary to address some of the world’s existential pressures, such as climate change and biodiversity loss, global health and nuclear proliferation.” (p. 7) (a point that U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken made in his key China speech in the spring of 2022 (Secretary of State Blinken, 2022). As a case in point, Canada hosted the biodiversity talks in December 2022 in Montreal that led to the adoption of the global biodiversity framework with 23 targets and related human rights commitments (Convention on Biological Diversity, 2022).

In the light of the broader comparative approach proposed in this article, how can we evaluate the Canadian IPS? We argue that on the global security and rebalancing front, the Canadian IPS has positioned itself quite firmly. The strategy has a strong security dimension and signals an important recalibration of the Canadian approach to China. It involves increased security commitments and naval presence in the Indo-Pacific and highlights needed cooperation with NATO and the Five Eyes. It also includes a reiteration of Canada’s policy stance on Taiwan, stating it “will oppose unilateral actions that threaten the status quo in the Taiwan Strait” (p. 9), while at the same time focusing on new areas of cooperation with Taiwan on the economic, health, or democratic governance fronts, for instance on IPETCA, the Indigenous Peoples Economic and Trade Cooperation Arrangement involving Australia, New Zealand, and Taiwan alongside Canada (p. 17).

On the global economic front, the strategy also reckons with the securitization of global economic relations. It highlights the need for diversification and the building of resilient supply chains. Yet, it clearly also continues to conceive of the global economy at least in part as a global public good and from an inclusive prosperity angle, with the recognition of the importance of the G20, “global rules that govern global trade” (p. 7), trade and investment agreements including the CPTPP, joint development goals, and the importance of global cooperation on climate change and biodiversity goals.

Canada’s IPS is a broad-ranged strategy that seeks to adjust to a fast-changing international geopolitical and geoeconomic environment and interpret the road ahead for Canada while balancing Canada’s relationship with the U.S. and its commitment to multilateralism and open trade. The two deep shifts driving the emergence of Indo-Pacific strategies around the world are at work in the Canadian case, with security considerations, both traditional and economic, as key drivers. Yet the Canadian IPS provides only a first step and a partial solution to these changing global realities. Challenges remain in terms of delivery and implementation, as many have pointed out (Nossal, 2024). To be sure, tensions are already present, for instance between security and climate change considerations, Canada’s IPS’s 1 st and 4 th strategic objectives, as the government tries to find its policy footing on issues such as electric vehicles and battery supply chains in the context of deepening China-U.S. tensions.

05. Conclusion

At some level, John Meyer is right (Meyer, Boli, Thomas, et al., 1997): the wave of Indo-Pacific strategies we have seen is a story of legitimacy and isomorphism [8] . But an important aspect of Meyer et al.’s argument is that convergence may well be accompanied by internal decoupling. Indeed, intrinsic to their model is the feature of isomorphism from the outside but decoupling domestically, given that, as the authors explain, “many external elements are inconsistent with local practices, requirements, and cost structures. Even more problematic, world cultural models are highly idealized and internally inconsistent, making them in principle impossible to actualize” (p. 154). As we identify in the text, this manifests, among other things, via the presence of dissonances between stated policy objectives in line with other Indo-Pacific strategies and international behaviour, or, still, between legacy concepts from a recent era such as open trade and the emerging economic security paradigm. This space thus remains a necessarily imperfect, transitional space, a journey, an experimentation without a clear sense of destination.

Nevertheless, this global experimentation driven by deep power-based and economic shifts is creating new relations and new connections, reviving frames that were out of fashion (economic security, industrial policy), and creating complications for frames that are still enshrined in global institutions (open trade). This highly interactive testing ground is leading to concrete innovations and real-world consequences. It is a battle for interests under shifting ideational models.

There may be no single clear institutional pathway to emerge at this point, but this could actually be the telling marker of this transitory era, as a multiplicity of minilaterals is emerging (for instance, the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) (Singh, 2023), as part of the G7-sponsored Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) (Partnership for Global Infrastructure, 2023) on the margins of the G20 in India). This trend demonstrates a new pluralistic (or fragmented, for some) dynamic in international relations. It may be the best that can be done under the crushing encumbrance of U.S.-China tensions: in the shadow of geopolitical competition, varied minilateral coalitions advancing global governance progress on an issue-based logic.

Appendices

Notes

-

[1]

Source: Interview by one of the authors with a senior official in Tokyo, December 21, 2023.

-

[2]

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook database, authors’ calculations.

-

[3]

See the useful definition of Grand Strategy by Gray: “Grand strategy is the direction and use made of any or all the assets of a security community, including its military instruments, for the purposes of policy as decided by politics” (Gray, 2010: 28). We are grateful to one anonymous reviewer for the helpful suggestion to separate strategy from the political goals pursued.

-

[4]

The White House. 2023. "G7 Leaders’ Statement on Economic Resilience and Economic Security." https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/05/20/g7-leaders-statement-on-economic-resilience-and-economic-security/.

-

[5]

Source: Interviews by one of the authors with senior EU and French officials in Paris for background only. April and December 2023.

-

[6]

Source: Interview by one of the authors with a senior official in Tokyo, December 21, 2023.

-

[7]

Source: Interview by one of the authors with a senior official in Tokyo, December 21, 2023.

-

[8]

Meyer, Boli, Thomas and Ramirez’s 1997 argument “explains why our island society, despite all the possible configurations of local economic forces, power relationships, and forms of traditional culture it might contain, would promptly take on standardized forms and soon appear to be similar to a hundred other nation-states around the world.” (p.152)

Bibliography

- Allison, Graham. 2017. Destined for War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides's Trap? Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Anderlini, Jamil, and Clea Caulcutt. 2023. Europe must resist pressure to become ‘America’s followers,’ says Macron. Politico . https://www.politico.eu/article/emmanuel-macron-china-america-pressure-interview/

- ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific. 2019. June 23. https://asean.org/speechandstatement/asean-outlook-on-the-indo-pacific/

- Blanchette, Jude, and Bonnie Glaser. 2023. "Taiwan’s Most Pressing Challenge Is Strangulation, Not Invasion." War on the Rocks, November 9.

- Brewster, Murray. 2018. Trump warns Congress to keep out of NAFTA talks with Canada. CBC News , September 1. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/nafta-canada-trump-trudeau-twitter-1.4807836

- By 2030: Protect 30% of Earth’s lands, oceans, coastal areas, inland waters; Reduce by $500 billion annual harmful government subsidies; Cut food waste in half. 2022. Convention on Biological Diversity , December 19. https://www.cbd.int/article/cop15-cbd-press-release-final-19dec2022

- Canada’s Indo-Pacific Strategy. 2022. Global Affairs Canada: Ottawa. Accessed August 1, 2023, https://www.international.gc.ca/transparency-transparence/assets/pdfs/indo-pacific-indo-pacifique/indo-pacific-indo-pacifique-en.pdf

- Chu, Yun-han, and Yongnian Zheng, eds. 2021. The Decline of Western-Centric World and the Emerging New Global Order: Contending Views. New York and London: Routledge.

- Defence White Paper. 2013. Australia Department of Defence . https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1516/DefendAust/2013

- Drezner, Daniel W., et al., eds. 2021. The Uses and Abuses of Weaponized Interdependence. Washington DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Ensuring Secure Seas: Indian Maritime Security Strategy. 2015. Naval Strategic Publication (NSP) 1.2 . https://www.indiannavy.nic.in/sites/default/files/Indian_Maritime_Security_Strategy_ Document_25Jan16.pdf

- EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific. 2022. February 21 https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eu-indo-pacific_factsheet_2022-02_0.pdf

- FACT SHEET: Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment at the G7 Summit. 2023. The White House, US Government , May 20. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/05/20/fact-sheet-partnership-for-global-infrastructure-and-investment-at-the-g7-summit/

- Farrell, Henry, and Abraham L. Newman. 2019. Weaponized Interdependence: How Global Economic Networks Shape State Coercion. International Security 44 (1):42-79.

- France’s Indo-Pacific Strategy. 2022. Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs of the French Republic: Paris. https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/en_dcp_a4_indopacifique_022022_v1-4_web_cle878143.pdf

- Friedberg, Aaaron. 2012. A Contest for Supremacy: China, America, and the Struggle for Mastery in Asia: Norton and Company.

- Fukuyama, Francis. 1992. The End of History and the Last Man . New York: Free Press.

- German Federal Foreign Office. "Policy Guidelines for the Indo-Pacific: Germany-Europe-Asia Shaping the 21st Century Together." https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/blob/2380 514/f9784f7e3b3fa1bd7c5446d274a4169e/200901-indo-pazifik-leitlinien--1--data.pdf.

- Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy. 2021. Cabinet Office. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/global-britain-in-a-competitive-age-the-integrated-review-of-security-defence-development-and-foreign-policy

- Goin, V. (2021). L’espace indopacifique, un concept géopolitique à géométrie variable face aux rivalités de puissance. Géoconfluences, 4 oct., http://geoconfluences.ens-lyon.fr/informations-scientifiques/dossiers-thematiques/oceans-et-mondialisation/articles-scientifiques/espace-indopacifique-geopolitique

- Gray, Colin S., 2010. The Strategy Bridge: Theory for Practice . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Haenle, Paul, and Nathaniel Sher. 2022. "How Pelosi’s Taiwan Visit Has Set a New Status Quo for U.S-China Tensions." Cargegie Endowment for International Peace, August 17.

- H.E. Modi, S. N. 2019. Prime Minister's Speech at the East Asia Summit: Indo- Pacific Oceans’ Initiative (IPOI). East Asia Summit . https://mea.gov.in/Portal/ForeignRelation/ Indo_Feb_07_2020.pdf

- H.E. Modi, Shri Narendra. 2018. 17th Asia Security Summit Keynote Address. Shangri-La Dialogue, International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), June 1. https://www.iiss.org/globalassets/media-library---content--migration/images-delta/dialogues/sld/ sld-2018/documents/narendra-modi-sld18.pdf

- Ikenberry, G. John. 2001. After victory : institutions, strategic restraint, and the rebuilding of order after major wars, Princeton studies in international history and politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Ikenberry, G. John. 2011. Liberal leviathan : the origins, crisis, and transformation of the American world order, Princeton studies in international history and politics. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Ikenberry, G. John. 2018. The end of liberal international order? International Affairs 41 (1):7-23.

- "Indo-Pacific: Guidelines for Strengthening Dutch and Eu Cooperation with Partners in Asia." Government of the Netherlands, https://www.government.nl/documents /publications/ 2020/11/13/indo-pacific-guidelines.

- Indo-Pacific Strategy of the United-States. 2022. The White House , February. https://whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/U.S.-Indo-Pacific-Strategy.pdf

- Irwin, Douglas A. 2020. Free Trade under Fire Fifth Edition. Princeton: Princeton University Press,. Accessed Access Date, Project Muse. Restricted to UCB IP addresses. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/73029/.

- Joint Communication to the European Parliament and the Council: The EU strategy for cooperation in the Indo-Pacific. 2021. European Commission: Brussels. Accessed August 22 2023, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/jointcommunication_2021_24_1_en.pdf

- Kardon, Isaac, and Jennifer Kavanagh. 2024. "How China Will Squeeze, Not Seize, Taiwan: A Slow Strangulation Could Be Just as Bad as a War." Foreign Affairs, May 21.

- King, Stephen D. 2017. Grave New World: the End of Globalization, the Return of History . New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- Köllner, Patrick, Robert G Patman, and Balazs Kiglics. 2022. "From Asia–Pacific to Indo-Pacific: Diplomacy in an Emerging Strategic Space." In From Asia-Pacific to Indo-Pacific: Diplomacy in a Contested Region: Palgrave Macmillan. 1-27.

- Leonard, Mark. 2021. The Age of Unpeace: How Connectivity Causes Conflict . London: Penguin Random House.

- Lighthizer, Robert E. 2020, May 11. The Era of Offshoring U.S. Jobs Is Over: the pandemic, and Trump’s trade policy, are accelerating a trend to bring manufacturing back to America. The New York Times . Accessed May 16, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/11/opinion/coronavirus-jobs-offshoring.html

- Martin, B. (2019). Cartographier les discours sur l’Indo Pacifique. Carnets de Recherche, Sciences-Po, 18 déc., https://www.sciencespo.fr/cartographie/recherche/cartographier-les-discours-sur-lindo-pacifique/

- Mearsheimer, John J. 2019. Bound to Fail: The Rise and Fall of the Liberal International Order. International Security 43 (4):7-50.

- Meyer, John W. , et al. 1997. World Society and the Nation State. American Journal of Sociology 103 (1):144-181.

- Meyer, John W., et al. 1997. World Society and the Nation-State. American Journal of Sociology 103 (1):144-181.

- Minister of Foreign Affairs Mandate Letter. 2021. Prime Minister of Canada Mandate Letters , December 16. https://www.pm.gc.ca/en/mandate-letters/2021/12/16/minister-foreign-affairs-mandate-letter

- Murphy, Erin L. 2023. "Ipef: Three Pillars Succeed, One Falters." Center for Strategic & International Studies, November 21.

- Natalegawa, H.E. Marty M. 2013. An Indonesian Perspective on the Indo-Pacific. Speech delivered at the conference on Indonesia in Washington, D.C. , May 16. https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/legacy_files/files/attachments/130516_MartyNatalegawa_Speech.pdf

- Nossal, Kim R. 2024. "The Power of Inertia: Understanding Canada’s “Easy Riding” in the IndoPacific." In Charting New Waters: Assessing Canada's Indo-Pacific Strategy One Year On, edited by Jeremy Paltiel and Bijan Ahmadi. The Institute for Peace and Diplomacy, 37-42.

- Prime Minister Kishida, Fumio. 2023. The Future of the Indo-Pacific , Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Accessed August 22, 2023. https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/100477791.pdf

- Prime Minister of Canada. 2023. Joint Leaders’ Statement on ASEAN-Canada Strategic Partnership. September 6. https://www.pm.gc.ca/en/news/sta tements/2023/09/06/joint-leaders-statement-asean-canada-strategic-partnership

- Rodrik, Dani. 2018. Straight Talk on Trade: Ideas for a Sane World Economy . Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Rodrik, Dani. 2023. The Global Economy’s Real Enemy is Geopolitics, Not Protectionism. Project Syndicate , September 6. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/global-economy-biggest-risk-is-geopolitics-not-protectionism-by-dani-rodrik-2023-09?barrier=accesspaylog

- Rodrik, Dani. March 2024. “Addressing Challenges of a New Era: Against Rule-of-Thumb Economics.” IMF Finance & Development . https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2024/03/Point-of-view-addressing-challenges-of-a-new-era-Dani-Rodrick?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery

- Scheinert, Christian. 2023. EU’s response to the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Briefing requested by the ECON Committee of the European Parliament . https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2023/740087/IPOL_IDA(2023)740087_EN.pdf

- Secretary of State Blinken, Anthony. 2022. The Administration’s Approach to the People’s Republic of China. U.S. Department of State , May 26. https://www.state.gov/the-administrations-approach-to-the-peoples-republic-of-china/

- Singh, Rishika. 2023. India-Europe Economic Corridor: What is the Partnership for Global Infrastructure Investment that is behind the project? The Indian Express . https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/everyday-explainers/india-europe-economic-corridor-pgii-explained-8933335/

- Speech by President von der Leyen on EU-China relations to the Mercator Institute for China Studies and the European Policy Centre. 2023. European Commission , March 30. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_23_2063