Abstracts

Abstract

As were other regions of Russia’s North, Chukotka (Chukotskii avtonomnyi okrug) was subjected to dramatic changes during the last century. Among the major long-lasting impacts for the Chukchi and Siberian Yupik Indigenous populations was a state-implemented village relocation policy that deemed dozens of historic settlements “unprofitable”, thus subject to forced closure and resettlement. Traumatic loss of homeland, the curbing of native patterns of (maritime) mobility, and the vanishing of traditional socioeconomic structures sent devastating ripples through the fabric of Indigenous communities, with disastrous results on societal health. To explore the intricate relationships between state-enforced resettlement and landscape interaction, particularly the perception and utilization of the environment, it is critical to look closely at Chukotka’s coastal environment. The article argues that the unique coastal landscape of Chukotka has influenced—while mitigating—the effects of the forced relocations. Improvised design and the reclaiming of formerly closed settlement sites play a paramount role here, with the reoccupation of old settlement niches representing a reconnection with a lost relationship to the littoral environment. The contemporary inhabitation and utilization of formerly closed villages show how the coastal landscape represents not only a “reservoir” in an ecological sense, but also a littoral reserve by providing the space for alternatives outside the congregated communities. Displacement destroys the sense of community, but in a reverse logic, a sense of community can also be established through renewed emplacement. The creation of autonomous social spaces is therefore part of an ongoing spatial resistance that actively uses the ecological niches of a coastal landscape to counter the long-lasting and detrimental effects of state-enforced resettlement policies.

Keywords:

- Chukotka,

- Chukchi,

- Siberian Yupik,

- settlements,

- displacement,

- resistance,

- mobility,

- hunting camps,

- coastal landscape

Résumé

Comme d’autres régions du nord de la Russie, la Tchoukotka (Čukotskij Avtonomnyj Okrug) a subi des changements spectaculaires au cours du siècle dernier. Parmi les principaux impacts durables pour les populations autochtones Tchouktches et Yupik de Sibérie figure une politique de relocalisation des villages mise en oeuvre par l’État, qui a jugé que des dizaines des hameaux historiques n’étaient pas « rentables » et qui devaient donc être fermés et relocalisés de force. La perte traumatisante du territoire d’origine, la limitation des modèles autochtones de mobilité (maritime) et la disparition des structures socio-économiques traditionnelles ont eu des effets dévastateurs sur le tissu social des communautés autochtones, avec des conséquences désastreuses sur la santé de la société. Pour explorer les relations complexes entre la réinstallation forcée par l’État et l’interaction avec le paysage, en particulier la perception et l’utilisation de l’environnement, il est essentiel d’examiner de près l’environnement côtier de la Tchoukotka. Cet article soutient que le paysage côtier unique de la Tchoukotka a influencé, tout en les atténuant, les effets des relocalisations forcées. La conception improvisée et la récupération de sites de peuplement autrefois fermés jouent ici un rôle primordial, la réoccupation d’anciennes niches de peuplement représentant une reconnexion avec une relation perdue avec l’environnement littoral. L’occupation et l’utilisation contemporaines de villages autrefois fermés montrent comment le paysage côtier représente non seulement un « réservoir », au sens écologique du terme, mais aussi une réserve littorale en offrant un espace pour des alternatives en dehors des communautés rassemblées. Le déplacement détruit le sens de la communauté, mais dans une logique inverse, un sens de la communauté peut également être établi par un nouvel emplacement. La création d’espaces sociaux autonomes fait donc partie d’une résistance spatiale permanente qui utilise activement les niches écologiques d’un paysage côtier pour contrer les effets durables et néfastes des politiques de réinstallation imposées par l’État.

Mots-clés:

- Tchoukotka,

- Tchouktche,

- Yupik de Sibérie,

- peuplements,

- déplacement,

- résistance,

- mobilité,

- camps de chasse,

- paysage côtier

Аннотация

Как и другие регионы Севера России, Чукотка (Чукотский автономный округ) за последнее столетие претерпела кардинальные изменения. Среди основных долгосрочных последствий для чукчей и сибирских эскимосов-юпик была проводимая государством политика переселения, в соответствии с которой десятки исторических поселений были признаны «нерентабельными» и поэтому подлежали принудительному закрытию, а их жители – переселению. Травматическая потеря родины, сдерживание местных моделей морской мобильности и исчезновение традиционных социально-экономических структур стали причинами разрушительных изменений повседневности общин коренных народов, что привело к катастрофическим последствиям для здоровья общества. Для изучения сложных взаимосвязей между принудительным переселением со стороны государства и взаимодействием с ландшафтом, особенно с восприятием и использованием окружающей среды, крайне важно внимательно изучить прибрежную среду Чукотки. В статье утверждается, что уникальный прибрежный ландшафт Чукотки повлиял на последствия вынужденного переселения – смягчил их. Импровизированная структура и рекультивация ранее закрытых поселений играют здесь первостепенную роль, при этом повторное занятие старых поселений представляет собой восстановление связей с локальной прибрежной средой. Современное заселение и использование ранее закрытых деревень демонстрируют, что прибрежный ландшафт представляет собой не только «резервуар» в экологическом смысле, но и прибрежный заповедник, предоставляя пространство для альтернативных социальных практик за пределами Собранных сообществ. Переселение разрушает чувство общности, но в обратной логике чувство общности также может быть установлено посредством нового заселения. Таким образом, создание автономных социальных пространств является частью продолжающегося пространственного сопротивления, которое активно использует экологические ниши прибрежного ландшафта для противодействия долгосрочным и пагубным последствиям государственной политики переселения.

Ключевые слова:

- Чукотка,

- чукчи,

- сибирские эскимосы-юпик,

- поселения,

- перемещение,

- сопротивление,

- мобильность,

- охотничьи стоянки,

- прибрежный ландшафт

Article body

Chukotka’s seashore is a coast gone lonesome. The after effects of various imperial boom and bust cycles—triggered by the restless hunt for fur, ivory, baleen, tin, gold, and blubber—are sedimented into a coastal landscape that had sheltered maritime cultures for millennia. The seismic political shifts of the twentieth century, the Sovietization of the Russian North, and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union left behind their very own void. Infrastructural investment was trailed by collapse and devolution, with its inevitable corresponding “impact on the notions of speed, distance and space” (Schweitzer, Povoroznyuk, and Schiesser 2017, 60). As other regions of Russia’s North, Chukotka (Chukotskii avtonomnyi okrug) was subjected to dramatic changes during the last century. Among the major long-lasting impacts for the Chukchi and Siberian Yupik Indigenous populations was a state-implemented village relocation policy that deemed dozens of historic settlements “unprofitable”, thus subject to forced closure and resettlement.

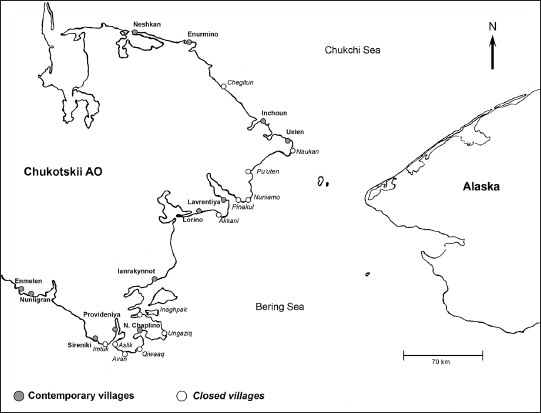

As a result, on the Chukchi Peninsula (Chukotskii poluostrov) alone, more than 80 settlements were abandoned or closed during the twentieth century (Bogoslovskaia 1993). The state-enforced resettlement of Indigenous communities peaked during the 1950s and 1960s and led to the depopulation of a coastline whose intricate settlement history traces back for thousands of years. The detrimental effects of these relocations have been thoroughly recorded for the village of Nuniamo by Boris Chichlo (1981), who witnessed its closure first-hand in 1976, and by Igor Krupnik and Mikhail Chlenov (2007) for the main Yupik settlements of Naukan, Ungaziq (Old Chaplino) and Aslik (Plover). A once densely populated coast lost most of its intermediate settlement sites. (Fig. 1).

Figure 1

Map of contemporary and historic settlements

Traumatic loss of homeland, the curbing of native patterns of (maritime) mobility, and the vanishing of traditional socioeconomic structures sent devastating ripples through the fabric of Indigenous communities, with disastrous results on societal health (Holzlehner 2012; Krupnik, and Chlenov 2013, 284–286). The early to mid-twentieth century transformations of the Yupik population of Chukotka are well documented (Csonka 2007; Krupnik and Chlenov 2013), complemented by valuable oral histories (Krupnik 2000) and fascinating micro-historical studies (Schweitzer and Golovko 2007; Chlenov and Krupnik 2016).

Sovietization as well as relocation cast their long shadows into present times, from a changed food culture (Kozlov, Nuvano, and Vershubsky 2007, 106–107) to transformed ideas of natural resources (Yamin-Pasternak 2007), unfortunately leaving few aspects of Indigenous life untouched. The history of village resettlements and the effects on local communities reveal the central role of landscape in forced relocation events in respect to both the Soviet rationales for the village closures and the detrimental outcomes for the relocated populations. The present article aims to complement existing ethno-historic studies of the Yupik and Chukchi communities of Chukotka with a contemporary perspective on what it means to live in “contested landscapes” (Tilley and Cameron-Daum 2017, 10).

In the course of the last century, differing perceptions and utilizations of Chukotka’s coastal landscape collided: Indigenous sea mammal hunters saw prime subsistence sites in the shallow bays and coves adjacent to their historic settlements, whereas Soviet planners, challenged with the task of supplying the remote settlements, saw infrastructural obstacles in implementing what they perceived to be a smooth economic structure. In both cases, differing forms of mobility were embedded in the specific relationship with the landscape. Indigenous, close-to-shore maritime hunt and travel depended on a dense network of coastal camps and settlements with swift access to the sea. In contrast, the Soviet supply of centralized settlements relied on a few embarkation points with accessible unloading facilities with deep-water ports.

To explore the intricate relationships between state-enforced resettlement and landscape interaction, particularly the perception and utilization of the environment, it is critical to look closely at Chukotka’s coastal environment. The specific characteristics of coastal zones, despite ever-changing outside historic forces, have the capacity to buffer the impacts of upheavals and disasters on local communities. I argue that the unique coastal landscape of Chukotka has influenced yet mitigated the effects of the forced relocations. Improvised design and the reclaiming of formerly closed settlement sites hereby play a paramount role, with the reoccupation of old settlement niches representing a reconnection with a lost relationship to the littoral environment.

The material for the present article was gathered from multiple ethnographic fieldwork seasons in Chukotka during 2008, 2009, and 2013, mostly in the communities of Lorino, Lavrentiya, Uelen, and Inchoun. It consists of a variety of multi-source data generated through multiple methods: Interviews with contemporary sea mammal hunters and traders; oral history interviews with relocatees; structural/architectural documentations; site maps (abandoned settlements); documentation of contemporary hunting practices and cooperatives at hunting camps; coastal ecology documentation; material studies; and archival work. In addition, my methodology highlights specific forms of interaction with the (ruined) landscape through map (landscape) interviews, interviews whilst walking, and a specific form of ethnographic interaction I refer to as re-visitations, i.e., on-site interviews with relocatees at their former, now abandoned settlement sites; a form of conjuration of the past’s spectral quality, residing in and evoked by the remnant built environment.

Destruction of (littoral) space: Relocation

The Indigenous coastal population of Chukotka was subjected to a twofold loss in the twentieth century, namely, the large-scale, state-induced, and enforced closures of many Indigenous villages combined with the subsequent resettlement of the population to centralized villages, and the following collapse of the Soviet economy and infrastructure. Chukotka truly represents a “shatter zone” (Scott 2009, 7–8), a region at the periphery of a nation-state characterized and shaped by the effects of state making and unmaking. Village resettlements on the Chukchi Peninsula during the 1950s and 1960s coincided with Khrushchev’s new economic policy that had as its central goal the strengthening and centralization of local economies (Grant 1995, 240). Reduction of individual villages and their amalgamation with larger economic units were an intrinsic part of that strategy. Economic consolidation (ukrupnenie) was the operative key term; a policy-driven concept focused on the transformation of many collective farms (kolkhosy/kolkhozes) into larger economic units in the form of state-owned enterprises (sovkhosy/sovkhozes).

Soviet industrialization of the Russian North was yet on another level: a process of double ruination. Next to the destruction and reordering of Indigenous space were accompanying processes of “cognitive enclosure” (Habeck 2013) that profoundly changed Indigenous life worlds. Collectivization of local economies and the industrialization of sea mammal hunting fundamentally transformed and replaced traditional subsistence practices in the Russian North. The traditional mixed economies of Indigenous people, who used the different resources in seasonal cycles over much larger territories, were rigidly centralized and their pastures or hunting grounds allotted to the state collective farms. Shift work in processing plants and predetermined catch quotas replaced traditional subsistence activities. Indigenous reindeer herders and sea mammal hunters were incorporated into collective farms, where social ties based on kinship were replaced by economic relationships (Schindler 1992). Industrial space therefore encroached on Indigenous space, and village relocations were an intrinsic part of the plan. For example, the introduction of coal-fired heating plants in coastal villages severely disrupted walrus rookeries in the vicinity of historic settlements, and village closures not only removed many villagers from their traditional hunting and fishing grounds but also relocated them to locations where direct subsistence resource access was often limited or scarce.

These new economic practices thus led to an antagonistic use of littoral space based on a different logic of space usage that regularly collided with local senses of place during the Sovietization and industrialization of Indigenous Siberia (Ssorin-Chaikov 2003). In Chukotka, for example, Indigenous coastal settlements were located close to preferred subsistence sites. Having maximum access to subsistence resources such as drinking water, sea mammal migration routes, salmon runs, and plant gathering sites was traditionally crucial when choosing the optimal site for a settlement. The Soviet era thus brought a diametrically opposed spatial logic to the region.

For the Soviet economic planners and engineers, maximum maritime infrastructural access to villages and state enterprises was one of the prime motivators for concentrating Indigenous populations in centralized villages (Krupnik and Chlenov 2013, 251). The proximity of deep-water ports or servicing facilities for barges and trawlers and a suitable terrain for house constructions were dominant factors in the choice for new settlements. Indigenous economic space was thus replaced by an economy that was based on a fundamentally different utilization of space (Holzlehner 2011).

Hence, the Sovietization and industrialization of the Russian North basically changed the very constitution of Indigenous societies, with village relocations at the forefront of this mission. Relocated villagers suddenly found themselves in an urbanized environment that lacked the qualities and opportunities of their former settlement sites. Access to traditional subsistence sites was, in most cases, severely impeded, and the forced submission of Indigenous economies into the overarching Soviet economy led to deep-seated changes in work conditions, occupational structures, and systems of mobility. Regrettably, despite the idealistic developmental ideas and strategies of Soviet planners, social and economic marginalization of the Indigenous population and the loss of traditional culture were among the unintended results.

Other forms of altering accompanied the spatial reorganization of Indigenous life-worlds that supplemented the village relocations. Indigenous identity networks were replaced by an array of Soviet institutions (boarding schools, house of culture, etc.) and Indigenous economic networks were replaced by working brigades to create a new “difference of productive relations” (Koester 2003, 275). Many implemented Soviet policies were characterized by “differential access to different kinds of mobility” (Gray 2005, 119). Village relocations, temporary forced resettlement of Indigenous children into boarding schools (internaty), and the movement of workers and administrators from the Russian heartland represented various aspects of a new Soviet-made spatial mobility that was at the same time largely unequal in terms of the possibilities for individuals to influence their own movement in space.

Resettlement and sedentarization policies and programs were not solely a Soviet phenomenon. During the twentieth century, many remote regions of the circumpolar North experienced a consolidation of state structures paired with an expansion of state powers into Indigenous and local communities. Underscored by logistic, economic, and strategic rationales, dozens of Indigenous villages were labelled “unprofitable”, subsequently closed, and their inhabitants relocated to more centralized settlements. With the possible exception of Fennoscandia, communities throughout the North experienced state-induced relocations in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Schweitzer and Marino 2006). For example, relocations in the Canadian Arctic in the 1940s to 70s, with their rational design of social order, show a similar “high-modernist ideology” (Scott 1998, 4) at work—with equally detrimental effects on the societal health of the affected communities. As in the Soviet case, the Canadian government’s resettlement program, run under the auspices of humanitarian aid to elevate Indigenous life standards, ultimately sought to ascertain the country’s sovereignty along its remote Arctic margins (Tester and Kulchyski 1994, 102–104). That said, one striking difference is how contemporary governments have dealt with and acknowledged the mistakes of the past: While the Canadian government has officially acknowledged and apologized for the relocations—with numerous social and economic programs existing today in Canada and the US to somehow alleviate the dire situation—the Russian state has never publicly denounced or addressed the resettlements. On the contrary, Indigenous activism and land claims in Chukotka have been actively curtailed by the Russian state (Gray 2007; Nielsen 2007).

Landscapes of resettlement

The double impact of state building and state collapse on Indigenous cultures left its traces in the memories and practices of coastal villagers. When traveling through the uprooted landscape of relocation with local informants, conflicting stories of the Soviet period regularly surfaced. Whether passing by boat or tracked vehicle past old settlements or abandoned Soviet military sites, my interlocutors often balanced memories of the negative effects of resettlements with remembrances of a working infrastructure and affluent transport possibilities. Although contradictory discourses in themselves, the uniting trope of movement through space, forced—and interrupted—by the Soviet state, surfaced in both perspectives. Stories of a golden age of transport and recounts of long-distance travels complemented stories of the lack of free movement, the coping with distance, and the negative effects of relocations on Indigenous traditions.

During ethnographic fieldwork in Chukotka in 2008, 2009, and 2013 on the topic of the relocations, I interviewed close to 30 people who were personally affected by the resettlements in the Chukotskii Raion (district) and around Provideniya. Most of the interviewees, who were already adults during the resettlements, remembered and emphasized the traumatic effects that period had had on their former life. The slightly younger generation, who were mostly in their teens during the resettlement period, had in general slightly more positive memories, recalling new opportunities and improved facilities in the larger villages.

In light of these different perceptions, three main themes emerged from the conversations I had with people who were directly or indirectly affected by the relocations. First, the Soviet state is obviously strongly associated with the relocations. Despite a commonly understandable idea of infrastructural improvement, the local perception of their execution first and foremost reflects the infrastructural failure of an ill-prepared move. Second, the collapse of the Soviet state is seen as a total collapse of economic and transport infrastructure, although the (physical) presence and absence of state agents (e.g., border security) in different locations along the coast has notable practical consequences on the everyday life of local sea mammal hunters. Third, still today, the Russian state is perceived as continuing to exert a strong and regulating influence on local subsistence practices (e.g., through hunting quotas). Therefore, concentrating on village resettlements as a forced move from one settlement to another, fails to acknowledge the fact that the life world of coastal villagers expands far beyond the confines of the village. Subsistence and travel space includes the coastal landscape in its totality; consequently, the memory of forced resettlements and the nostalgia for a Soviet age of intact infrastructure fuses in a local discourse in which the memory of an age of unrestricted movement through the coastal landscape plays a paramount role.

Production of (Littoral) Space: Re-settlement

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the abandoned coast breathes anew. Freshly established and revitalized relations to the coastal landscape of Chukotka are once again key to understanding the long-lasting effects of the relocations and provide answers to pathways of healing in a ruptured landscape. Some of the former closed and relocated villages have become new mooring points to escape the predicament of the post-Soviet disintegration. For example, the former Chukchi settlement and Soviet boat repair station of Pinakul (closed in the 1970s) is almost permanently re-inhabited by an extended family and individual hunters from Lavrentiya (Fig. 2); the former village of Akkani (closed in the 1960s) is used today as a permanent hunting base for both the members of the sea mammal hunting collective in Lorino and individual hunters (Yashchenko 2020); and Chegitun (closed in 1958), a former historic village and prime subsistence site, is now regularly visited by hunting parties from Uelen.

Thus, the ruins of former settlements are not only places of the Soviet past, but also play a role in present-day lives, as some individuals have moved back into the formerly abandoned villages and actively use these sites for a variety of subsistence activities. Embedded in the landscape and local ecology, these reoccupied sites therefore enable some people to escape the shattered utopia of Soviet modernization.

Figure 2

Pinakul, 2013

That said, not all closed and abandoned settlements provide equal prospects. Only a few sites (e.g., Pinakul, Nuniamo, and Inaghpak) actually offer substantial building materials that could be reused. Other seasonally occupied hunting camps, such as Chegitun, Pu’uten, Qiwaaq, and Imtuk, exist without larger permanent structures. The two largest former Siberian Yupik villages of Naukan and Ungazik (Old Chaplino), as well as Aslik (Plover) and Avan remain abandoned and are only occasionally visited by travelers, hunters, or mushroom pickers. Multiple factors thus determine the prospects of a re-settlement of a closed villages site: ecology, distance to a permanent settlement, and prevalence of building materials, as well as attached memories, emotions, and previous kinship ties.

The specific microecology of these sites—proximity to sea mammal congregations and migrations, sheltered bays and polynyas, access to freshwater—make them attractive places for subsistence-based lifestyles beyond the confines of the centralized villages. These newly established camps share several characteristics. Located at prominent capes or lookouts along the coast, with close access to migrating sea mammals, these sites also feature protected coves for small watercraft landing. In addition, prevalent currents keep the surroundings of the capes ice-free early and late in the hunting season, thereby favoring the seal hunt that depends on open water or slush ice.

Another common characteristic of the re-settled camps is their relative proximity (up to 10 km) to larger settlements. As gasoline consumption is an important factor in the planning and execution of contemporary sea mammal hunts, certain sites with equally good subsistence conditions have not been chosen for hunting camps due to their distance to permanently inhabited villages. One of the unanticipated side effects of the abandonment or closure of ecologically affluent places is the unequal accumulation of resources at these sites, as some of these locations have turned into hidden ecological reservoirs. For example, the historic settlement and former coastal reindeer herder camp of Pu’uten, abandoned in the 1940s, is known for its warm microclimate, wild onions, fishing and seal hunting (Fig. 3). Although a hunting cabin there, providing basic shelter, is sometimes used as a storm shelter for boat parties traveling along the coast, Pu’uten is visited only occasionally by fishing and hunting parties due to its relatively long distance to larger villages. According to local hunters, the absence of human subsistence activities has led to an astonishing increase in fish and seal populations in the bay that shelters the former settlement.

Figure 3

Pu’uten, 2013

For hunter-gatherers, building is a part of everyday life (Ingold 2000, 180) and formerly abandoned or closed settlement sites along Chukotka’s coast are once again places of construction activities. New houses and sheds have been built in close proximity, yet are spatially removed from formerly relocated settlements, and building materials are extensively salvaged from the adjacent sites. The building and creation of a new home are indeed powerful and meaningful strategies of re-settling the old places (Bolotova and Stammler, 2008). Mainly used as hunting camps, the re-inhabited places are being filled with contemporary activities—from house construction to work on traditional skin boats—that tie people to each other and to the place they co-inhabit. The architecture of these new camps, characterized by the creative re-usage of artifacts and building materials from the destroyed village, represents a case in point for the widespread use of “proximal design” (Usenyuk, Sampsa, and Whalen 2016), namely, a phenomenon of creative, local adaptation of imported technologies in the constraining environment of the North (Fig. 4).

Figure 4

Improvised fish smoker, Akkani, 2008

To invest a place with significance is an integral part of placemaking (Feld and Basso 1996, 5–8). Thus, the formerly abandoned and now partially resettled places not only play a central role in the restructuring and revitalization of hunting traditions, but also provide space for alternative life concepts outside of the centralized villages. Ecologically embedded, these places also offer an emotional anchorage for the formerly displaced population. As physical places, hunting camps “sit between the remembered past and the lived present” (McIlwraith 2012, 100) and function as homes in both an emotional and sentimental way, reflecting historically deep and enduring relationships with animals and the landscape. Anna, who, during the 1990s, moved with her husband and young children to the abandoned settlement of Pinakul, across the Bay of Lavrentiya, expressed this notion:

We had free reign (svoboda deistvii) in Pinakul. Hunting, fishing and all these things were possible. We had not experienced such a household economy before. I really liked that. It was very interesting when we moved to Pinakul. We built for example a greenhouse. At that time I did not work and we grew cucumbers and even raised chickens. We started slowly to build. First, we stayed there only at the weekends, and then we lived there permanently during the winter… When you are retired, you can settle in there, you only have to return to town for supplies, well this is at least how we have planned it. The atmosphere is good there, and the fishing and the hunt. It is good there.

Anna, Lavrentiya, interview with author 2008

For some hunters and their families, the hunting camp’s exceptional qualities extend beyond exclusive subsistence utilization. These places represent an escape from the predicament and pressures of village life and a cultural space contrasting the more urban settlements. Nadezhda, a native of Naukan and long-term resident of Uelen, explained this contrast:

I always feel a certain pressure (davlenie) in town. You always have to run around on errands, and everything is far away from each other. I only lived for a year in Pinakul and it is such a different place. There is something special about this place.

Nadezhda, Uelen, interview with author 2009

Subsistence activities at former inhabited village sites are also part of a strategy to stay active and occupied past the working age. Slava, a life-long hunter from Lorino who had moved permanently to the closed and subsequently re-settled hunting camp of Akkani, communicated this sentiment:

I am on pension now, but why should I sit back home in Lorino, it is boring there. If I would stay in town, I would become an alcoholic and die soon. Here in Akkani, the seal hunt is very good, I am occupied, and berries and plants are very close.

Slava, Akkani, interview with author 2008

In a double sense, these hunting camps have become sites of “material and social reconstruction” (Oliver-Smith 2005, 51). Revitalization of old hunting technologies, subsistence camps, and traditional forms of cooperation allow for alternative life concepts that are diametrically opposed to the realities in the villages. Marked by the absence of alcohol in the camps, family and friendship groups cooperate in hunting, building, and gathering in communal work dictated by an individual timeline. Hunting camps are therefore places of active cultural reproduction, where a younger generation is practically introduced to the intricacies of maritime hunting. In the case of Akkani, strong family networks or associative relationships through hunting cooperatives appear to be a pre-requisite for the successful reclaiming of a lost settlement site that enables its inhabitants to “finally feel home again” (Yashenko 2020).

In addition, due the spatial distance from regional centers, the camps are situated beyond the practical control of border guards, whose strict management of coastal boat traffic is viewed by most of the hunters as a serious interference in their day-to-day hunting activities. The absence of the state and its local representatives has therefore created new opportunities for a self-determined life beyond the strict supervision of state agents. Remoteness has thus been transformed into a valuable resource (Schweitzer and Povoroznyuk 2019).

Nuniamo: A place destroyed and rebuilt

Zhenia and I stared with binoculars into the hazy blue of a mirror-like Bering Sea. I met Zhenia, a native hunter with a mixed Siberian Yupik and Chukchi heritage, in 2008 in Lavrentiya when I was conducting a series of interviews on the effects of village relocations on the Indigenous population of coastal settlements in northeastern Chukotka. As the brother of an old acquaintance of mine from previous visits to the region, he not only agreed to extensively talk about the relocations and the changing subsistence practices, but also took me on a multi-day trip to a hunting camp several miles north of town.

August had arrived with a spell of hot and calm days—perfect conditions for a walrus hunt. We were sitting on a steep bluff located in the northwestern corner of the former settlement of Nuniamo, in a makeshift shelter, a wooden bench with a small roof that resembled a bus stop somewhere in the Russian countryside. Altitude above sea level matters a lot for maritime hunters, as sea mammal hunting depends heavily on the visual signs made by the breathing fountains and partial appearance of walruses and whales above the waterline. Hours of inactivity, consumed by ocean gazing, is then suddenly interrupted by a rush of activity when animals are sighted and the controlled panic of the hunt is channeled into the ensuing chase, kill, hauling, and butchering procedures.

Five cabins (balki) were built at this place during the 1990s (Fig. 5). Using old building materials salvaged from the abandoned houses of Nuniamo, the cabins are spacious and comfortable and can sleep an entire family or hunting party. Two cabins belong to Zhenia and his extended family. Below the bluff were the remains of a former Soviet sea mammal blubber processing factory that was built over a prehistoric settlement. Surrounded by traditional meat caches and scores of gasoline drums, the ruin of the village’s economic backbone had faded back into history.

Figure 5

Contemporary hunting camp, Nuniamo, 2008

The adjacent settlement of Nuniamo was closed in 1976 (Chichlo 1981). Zhenia, then ten years old, was relocated with his family to Lorino, a settlement 20 km south along the coast. As an adolescent, he later moved to Lavrentiya, the regional center, where he works today as a marine boat inspector. In the last years, he had been frequently visiting his former village during the summer months. It had become home to him again.

Nuniamo, a historic settlement site, was refitted with Soviet-style housing around 1958 when the Siberian Yupik village of Naukan, located at Chukotka’s East Cape, was closed. As in other relocation cases, multiple rationales were brought forward by the Soviet authorities to close Russia’s easternmost Yupik settlement: too steep for modern housing, too close to the border with Alaska, or too small to be economically viable. Despite or probably because of Naukan’s unique location on a steep slope surrounded by tall cliffs and in visual distance to Alaska—topographic characteristics that protected Naukan like a natural fortress and gave it importance, historically, as a Trans-Beringian trade hub—the predominantly Siberian Yupik population was scattered to several other villages, Nuniamo being one of them. Local sentiments and sense of place were secondary, as Zhenia remarked:

It was very hard for the older generation to resettle. Especially the people from Naukan missed their place very much. Naukan was a very special place, it was very hot in the summer and the people around considered it an island. For instance, people traveling North along the coast carried their boats overland from Dezhnevo to Uelen, rather than passing by Naukan and around East Cape.

Zhenia, Nuniamo, interview with author, 2008

Chukchi from the small settlements and camps of Pinakul and Chini and Siberian Yupik from Naukan were first resettled to Nuniamo, although the move was ill-prepared and the houses, still unfinished (Krupnik and Chlenov 2013, 275). A newly build meat- and blubber-processing factory that supplied walrus meat to the reindeer herders inland provided some work for the recent relocatees. But it was a different occupation and thus a different rhythm dominated the resettlers’ lives, compared to the community-based sealing, walrus, and whale hunting activities at the closed locations. In addition, in so-called combined farms, where reindeer herding, sea mammal hunting, and fox fur production were part of the same enterprise, the Soviet planners tried to amalgamate different subsistence activities under one economic framework. Zhenia began working at the Arctic fox farm and later, in the local sea mammal hunting collective of Lorino, a job he vividly remembered as being exceedingly exhausting:

Compared to traditional hunting, where you work as a team on your own schedule, in the kolkhoz seven to eight people worked each shift and had to bring in an equal amount of walrus. And each person worked individually on one of the animals. These were often very long shifts, lasting up to three o’clock in the morning. It was very strenuous work.

Zhenia, Nuniamo, interview with author 2008

Some of these enterprises were nothing more than flimsy economic experiments. As part of the economic consolidation that began under Khrushchev during the 1950s, individual settlement sites in the region were identified to host so-called combined farms (sovkhozy) that mimicked industrial factories. They were often planned without considering local ecological knowledge and the long-term sustainability of locally available marine resources.

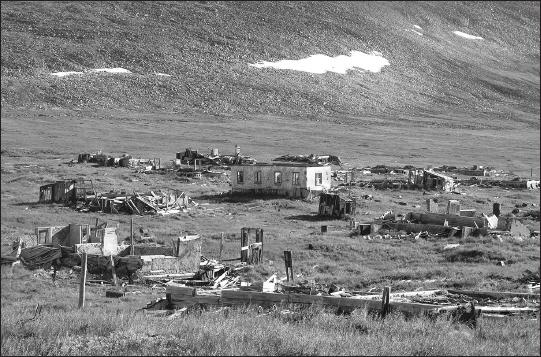

Another detrimental result was the drastic reduction of walrus populations along the coast (Demuth 2019, 129). This was apparently also the case with Nuniamo, as this village’s economic viability and the sea mammal hunter collective Lenin’s Path (Leninskii put’) lasted only several years until its final closure 19 years later. And once again, the people were displaced. From our vantage point above the former settlement, we could see the remains of Nuniamo’s houses, neatly arranged along several rows, still attesting to the geometry of its Soviet planners (Fig. 6). Zhenia pointed out the different buildings of his past village to me: the school, the commons, the bakery, the store, the warehouse, and the house where he was born. Partially looted by the last generation, the houses had crumbled down to their foundations. Single support beams, pale from the salty and glaring sun, reached up like erected whale ribs into the immaculate blue sky. Abode chimneys and rusty heating pipes, still connecting individual buildings, reminded of the former human inhabitation, with rusty bed frames, tea kettles, glass bottles, and vinyl wallpaper as the scant remains of their interior architecture. At the east end of the village were the collapsed remains of a former fox farm. Once, the farm with its hundreds of small cages was sitting on tall wooden poles to raise the floor level above the winter’s snowdrifts. Everything was now crumbled into a scattered mass of weathered wood and wire. Close by, a large pile of whale bones spread out across the tundra, demarcating the end of the village. Wild dogs and ground squirrels were now the former village’s sole inhabitants.

Figure 6

Closed and abandoned village, Nuniamo, 2008

Walking through the remnants of the former settlement marks a stark contrast between the utopian discourse of Soviet modernization—expressed through a civilizational agenda that stressed the explicit development of infrastructure, housing, education, and health—and the on-the-ground reality of the destruction of a native settlement. Strolling with Zhenia through what remained of his former village, our “conversations in place” (Anderson 2004, 255) were inspired and evoked by individual objects and framed by the architectural vestiges of the derelict buildings we crossed in our wandering path. Immersed in the disrupted texture of his former village life, the materiality of relocation became hauntingly tangible. Razed by chains that were pulled by bulldozers, the wood framed houses showed little resistance. The remaining ochre-colored trunks of brick stoves and rusted heating pipes that once connected the individual houses remind us of the complex challenges of artic housing—destroyed by its own creators. Aside from the bodily experience of walking through a field of material excess spread out on the shores of the Bering Strait and producing a rich place narrative, the ghost town go-along provided material evidence of the forceful destruction of the village following its closure. The derelict site triggered a sense of “critical awareness” (Edensor 2008, 138) that brought Zhenia’s memories of the forced relocation to the surface:

They officially closed the village in 1976; we were the last who left in 1979. We were the last ones who stayed behind, when they came with the helicopter and told us: Faster, you are disturbing the plan! First, they could chase us out, we couldn’t leave that fast, we had dogs to take care of. During this summer, the helicopter came and landed over there and picked us up, only a caretaker of the dogs remained. We later moved them too.

Zhenia, Nuniamo, interview with author 2008

And yet, Zhenia still harbored a sense of nostalgia for the place where he had spent a good part of his childhood. He especially remembered climbing on the cliffs and comparing the surrounding landscape of Nuniamo with that of Lorino, the place he was moved to with his family after the closure of Nuniamo: “Do you see this?” pointing to the steep cliff on the other side of the small natural harbor below the settlement. “There are no cliffs like that in Lorino. I really missed that. As a child, I used to climb a lot in those cliffs.”

Bluffs and cliff sites overlooking capes and bay entrances are preferred sites for hunting camps. Here, hunters sit for hours at a time and scour the horizon for the scant reflections or breathing fountains of surfacing game. It is no coincidence that the remains of prehistoric settlements are located at these very same places. Nuniamo’s elevated location is an ideal place to spot migrating sea mammals. Moreover, walrus seek shelter from the fierce fall storms in the adjacent bays that offer a natural stop for the animals in their annual migration along the coast, and the prevalence of local polynyas—areas of open water in sea ice—create perfect conditions for late fall or early spring hunt.

Later in the evening, we were sitting on the small porch of his cabin (outfitted with chairs salvaged from the movie theatre of the village’s former House of Culture), still scanning the horizon for walrus. The two young men who came with us to the camp had earlier spotted three adult walruses, but the ensuing hunt was abandoned as the team lost sight of the animals when they passed further north around Nuniamo Cape and a sudden wind had picked up and made any further chase futile.

Looking directly at his young fellow hunters, Zhenia told a story about how he drank heavily in his former life: “I drank straight for three weeks and couldn’t remember anything afterwards…” He then snuck in some advice for the attentively listening young hunters: “You really have to want it by yourself! The people in former times didn’t drink either!”

In his opinion, a place like Nuniamo, a former historic settlement first rebuilt and subsequently abandoned by Soviet planners, had the inherent capacity to heal the wounds sustained in the new settlements where people were relocated: “Here, at this place, you can draw energy from nature. In the village, all you do is drink. If I am able to bring my children and grandchildren here to Nuniamo, everything will be fine.”

Conclusion: Dwelling in littoral niches

Reclaiming, building, and creating new homes—powerful and meaningful re-settling strategies of forcefully abandoned places—also entail a creative engagement with the landscape and the abandoned objects of a surrounding world. Landscape, technology, infrastructure, and building design are part of an intricate meshwork that has shown high degrees of adaptivity and resilience. Thus, “human-thing entanglements” (Hodder 2011) become visible through infrastructural and technological changes as part of new maritime adaptations.

The permanent settlement structures of Siberian Yupik and Chukchi sea mammal hunters along the Bering Strait coastline date back at least 2,500 years. Chukotka’s rugged coast is dotted with the remains of numerous historic and prehistoric settlements that are clearly discernible by their mound-shaped house ruins and protruding whalebones. For centuries, subsisting mostly on a sea mammal and fish diet supplemented by land game and birds, the Indigenous population has chosen semi-subterranean house constructions to protect them from the harsh winters and fierce Bering Sea storms. The use of whale bones, driftwood, and other marine mammal bones are well documented in historic and prehistoric dwellings along the Chukchi Peninsula, as well as on St. Lawrence Island and Punuk Island (Lee and Reinhardt 2003, 131–138).

The creative and adaptive (re-)usage of drift objects extends into the Soviet and post-Soviet era. Bricolage-type machines (e.g., trikes with low-pressure tires) are a common sight in the small settlements of the Russian North, not to mention the new, post-Soviet flotsam and jetsam in the form of shipping containers. Chukotka’s coastal settlements are almost exclusively supplied by ship with indispensable goods, heating fuel, and coal. Maritime transport along the Pacific east coast to Kamchatka and Vladivostok connects Chukotka to the Asian-Pacific market and beyond. In the last twenty years, large amounts of this signature vessel of global capitalism have been abandoned along the beaches and settlements of Chukotka. Their versatile design features (lightweight and easily customizable) make them vessel and dwelling at the same time. As in other transition economies in the world, where the shipping container has emerged as an element of a global commodity architecture, these modern-day drift objects play an increasing role in Chukotka as auxiliary construction elements that are utilized for boat sheds, house additions, storages, stores, and even administrative buildings. Improvised design is not only a question of technical adaptation but encompasses a strategy of dwelling in a world of wounded infrastructure. In the examples showcased here, do-it-yourself strategies and practices thus represent, creative and effective ways of place-making in a disrupted world.

Chukotka’s resettlement history is set in a contested landscape, where “local theories of dwelling” (Feld and Basso 1996, 8) collided with governmental ideas of proper housing and settlement structure. Today, the inhabitation of formerly abandoned villages sites has created conflicts of interest with respect to land and subsistence rights between individual family groups and municipal authorities. With no official title to land, the new temporary inhabitants operate in a legal grey zone, often at the mercy of local authorities with their own agenda.

T. Ingold juxtaposes two essentially different forms of human dwelling, expressed by distinctive relations to the environment (Ingold 2000, 186). The distinction between a “building perspective,” where worlds are made before they are lived in, and a “dwelling perspective,” where buildings arise through human activity and interaction with the environment, sheds light on the fundamental differences between dwelling and environment in the case of Indigenous coastal cultures and the Soviet state.

With the coastal village resettlements and economic consolidations, the Soviet development strategy imposed a building and settlement plan on Chukotka’s society with little regard for local sentiments, traditional knowledge, and subsistence strategies. Indeed, economic and infrastructural changes were planned and implemented from “outside”, with local communities forced to comply with the newly-made world. In contrast, the settlement and building structure of traditional villages evolved in close interaction with the environment, its coastal topography, and subsistence opportunities. The unique littoral culture of coastal villages—where proximity to the sea and its resources were paramount in the location of a particular settlement—was superseded by a coastal culture of maximum infrastructural access and economic output implemented by the Soviet state.

The history of Arctic maritime cultures can be seen as a series of shifting adaptations, in which populations actively adjust to changing ecological conditions, with alternating growth and decline periods (Krupnik 1993). Various adaptation strategies hereby play an important role by minimizing risk and uncertainty, optimizing flexibility of choice, maximizing energy extraction, and rotating among seasonal procurement strategies. In the course of these shifts, long-term settlements were regularly abandoned and “uninhabited lands, lands belonging to migratory communities, or abandoned settlements together with their resource territories, played the role of unique temporal reservoirs” (ibid., 268).

The contemporary inhabitation and utilization of formerly closed villages show how the coastal landscape represents not only a “reservoir” in an ecological sense, but also a littoral reserve by providing the space for alternatives outside the congregated communities. Displacement destroys the sense of community, but in a reverse logic, a sense of community can also be established through renewed emplacement. The creation of an autonomous social space at these contemporary hunting camps is therefore part of an ongoing spatial resistance that actively uses the ecological niches of a coastal landscape to counter the long-lasting and detrimental effects of state-enforced resettlement policies.

Closed villages that have become contemporary hunting camps represent places that are generative and regenerative at the same time (Casey 1996, 26). Active participation in the creation of a new inhabitable environment and family-based subsistence activities combined with the exceptional qualities of these places has changed these littoral niches into social and economic spaces that bear the potential for community regeneration. After the failed experiment of large-scale social and cultural engineering, the depopulated coastal landscape, with its abandoned settlements, is reborn as new points of anchorage for partial re-settlements and revitalization movements. The coastal landscape of Chukotka is thus not only a location where state forces inscribed their social and economic blueprint, but also a regenerative space where hidden forms of resistance to state-enforced resettlement policies can find their very own place.

Appendices

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful for the generous support, friendship, and exceeding hospitality of the people of Chukotka. My special thanks go to all the members of the Eineucheivun family, the late Gena Inankeuyas, and the late Yasha Vukvutagin. This work would not have been possible without their shared stories, insights, and comments. I am also indebted to the logistical assistance provided by the Chukotka Science Support Group. The research was supported by the US National Science Foundation under the grant “Moved by the State: Perspectives on Relocation and Resettlement in the Circumpolar North” (Grant No. 0713896; PI Peter Schweitzer) and by the National Science Foundation, Arctic Social Science under the grant “Far Eastern Borderlands: Informal Networks and Space at the Margins of the Russian State” (Grant No. 1124615; PI Tobias Holzlehner). I also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful and valuable comments.

References

- Anderson, John, 2004 “Talking Whilst Walking: A Geographical Archaeology of Knowledge.” Area 36 (2): 254–261.

- Bogoslovskaia, Liudmila, 1993 “List of the Villages of the Chukotka Peninsula (2000 B.P. to Present).” Beringian Notes 2, no. 2 (December): 1–12.

- Bolotova, Alla, and Florian Stammler, 2008 “How the North Became Home: Attachment to Place Among Industrial Migrants in Murmansk Region.” In Migration in the Circumpolar North: New Concepts and Patterns, edited by C. Southcott and L. Huskey, 193–220. Edmonton, Canada: Canadian Circumpolar Institute Press.

- Casey, Edward S., 1996 “How to Get from Space to Place in a Fairly Short Stretch of Time: Phenomenological Prolegomena.” In Senses of Place, edited by S. Feld and K. H. Basso, 13–52. Santa Fe, CA: School of American Research Press.

- Casey, Edward S., 2001 “Between Geography and Philosophy: What Does it Mean to be in the Place-World?” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 91, no. 4 (December): 683–93.

- Chlenov, Mikhail A., and Igor I. Krupnik, 2016 “Naukan: Glavy k istorii [Naukan: Chapters Towards History].” In Kul’turnoe nasledie Chukotki: problemy i perspektivy sokhraneniia [Save and Preserve: The Cultural Heritage of Chukotka: Problems and Prospects for Conservation], edited by M. M. Bronshtein, 38–73. Moscow—Anadyr: Gosudarstvennyi muzei Vostoka.

- Chichlo, Boris, 1981 “Les Nevuqaghmiit ou la fin d’une ethnie.” Études Inuit Studies 5 (2): 29–47.

- Csonka, Yvon, 2007 “Le peuple yupik et ses voisins en Tchoukotka: huit décennies de changements accélérés.” Études Inuit Studies 31 (1-2): 7–23.

- Demuth, Bathsheba, 2019 Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- Edensor, Timothy J., 2008 “Walking Through Ruins.” In Ways of Walking: Ethnography and Practice on Foot, edited by T. Ingold and J. L. Vergunst, 123–142. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate.

- Feld, Steven, and Keith H. Basso, eds., 1996 Senses of Place. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.

- Grant, Bruce, 1995 In the Soviet House of Culture: A Century of Perestroika. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Gray, Patty, 2005 The Predicament of Chukotka’s Indigenous Movement: Post-Soviet Activism in the Far North. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gray, Patty, 2007 “Chukotka’s Indigenous Intellectuals and Subversion of Indigenous Activism in the 1990s.” Études Inuit Studies 31 (1-2): 143–162.

- Habeck, J. Otto, 2013 “Learning to Be Seated: Sedentarization in the Soviet Far North as a Spatial and Cognitive Enclosure.” In Nomadic and Indigenous Spaces: Productions and Cognitions, edited by J. Miggelbrink, J. O. Habeck, P. Koch, and N. Mazzullo, 155–179. Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

- Hodder, Ian, 2011 “Human-Thing Entanglement: Towards an Integrated Archaeological Perspective.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 17, no.1 (March): 154–177.

- Holzlehner, Tobias, 2011 “Engineering Socialism: A History of Village Relocations in Chukotka, Russia.” In Engineering Earth: The Impacts of Megaengineering Projects, edited by S.D. Brunn, 1957–73. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer Science+Business Media.

- Holzlehner, Tobias, 2012 “‘Somehow, Something Broke Inside the People’: Demographic Shifts and Community Anomie in Chukotka, Russia.” Alaska Journal of Anthropology 10 (1-2): 13–28.

- Ingold, Timothy, 2000 The Perception of the Environment: Essays in Livelihood, Dwelling, and Skill. London: Routledge.

- Koester, David, 2003 “Life in Lost Villages: Home, Land, Memory and the Sense of Loss in Post-Jesup Kamchatka.” In Constructing Cultures Then and Now: Celebrating Franz Boas and the Jesup North Pacific Expedition, edited by L. Kendall and I. Krupnik, 269–283. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Kozlov, Andrew, Vladislav Nuvano, and Galina Vershubsky, 2007 “Changes in Soviet and Post-Soviet Indigenous Diets in Chukotka.” Études Inuit Studies 31 (1-2): 103–121.

- Krupnik, Igor, 1993 Arctic Adaptations: Native Whalers and Reindeer Herders of Northern Eurasia. Hanover: University Press of New England.

- Krupnik, Igor, 2000 Pust’ govoriat nashi stariki: Rasskazy aziatskikh eskimosov-iupik, sapisi 1975–1987 [Let our Elders Speak: Stories of the Siberian Yupik Eskimo, Recordings 1975–1987]. Moscow: Russian Institute of Cultural and Natural Heritage.

- Krupnik, Igor, and Mikhail A. Chlenov, 2007 “The End of ‘Eskimo Land’: Yupik Relocations in Chukotka, 1958–1959.” Études Inuit Studies 31 (1–2): 59–81.

- Krupnik, Igor, and Mikhail A. Chlenov, 2013 Yupik Transitions: Change and Survival at Bering Strait, 1900–1960. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

- Lee, Molly, and Gregory A. Reinhardt, 2003 Eskimo Architecture: Dwelling and Structure in the Early Historic Period. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press.

- McIlwraith, Tad, 2012 “A Camp is Home and Other Reasons Why Indigenous Hunting Camps Can’t be Moved Out of the Way of Resource Developments.” The Northern Review 36, no. 2 (June): 97–126.

- Nielsen, Bent, 2007 “Post-Soviet Structures, Path-Dependency and Passivity in Chukotkan Coastal Villages.” Études Inuit Studies 31 (1-2): 163–182.

- Oliver-Smith, Anthony, 2005 “Communities after Catastrophe: Reconstructing the Material, Reconstituting the Social.” In Community Building in the Twenty-First Century, edited by S. E. Hyland, 45–70. Santa Fe, CA: School for Advanced Research Press.

- Schindler, Debra L., 1992 “Russia Hegemony and Indigenous Rights in Chukotka.” Études Inuit Studies 16 (1-2): 51–74.

- Schweitzer, Peter P., and Evgeniy V. Golovko, 2007 “The ‘Priests’ of East Cape: A Religious Movement on the Chukchi Peninsula During the 1920s and 1930s.” Études Inuit Studies 3 (1-2): 39–58.

- Schweitzer, Peter P. and Elizabeth Marino, 2006 Coastal Erosion Protection and Community Relocation Shishmaref, Alaska: Collocation Cultural Impact Assessment. Seattle, WA: TetraTech, Inc.

- Schweitzer, Peter P. and Olga Povoroznyuk, 2019 “A Right to Remoteness? A Missing Bridge and Articulations of Indigeneity Along an East Siberian Railroad.” Social Anthropology / Anthropologie Sociale 27, no. 2 (May): 236–252.

- Schweitzer, Peter P., Olga Povoroznyuk, and Sigrid Schiesser, 2017 “Beyond Wilderness: Towards an Anthropology of Infrastructure and the Built Environment in the Russian North.” The Polar Journal 7, no. 1 (June): 58–85.

- Scott, James C., 1998 Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Scott, James C., 2009 The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Ssorin-Chaikov, Nikolai V., 2003 The Social Life of the State in Subarctic Siberia. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Tester, Frank J., and Peter Kulchyski, 1994 Tammarniit (Mistakes): Inuit Relocation in the Eastern Arctic 1939–63. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Tilley, Christopher, and Kate Cameron-Daum, 2017 An Anthropology of Landscape: The Extraordinary in the Ordinary. London: UCL Press.

- Usenyuk, Svetlana, Hyysalo Sampsa, and Jack Whalen, 2016 “Proximal Design: Users as Designers of Mobility in the Russian North.” Technology and Culture 57, no. 4 (October): 866–908.

- Yamin-Pasternak, Sveta, 2007 “An Ethnomycological Approach to Land Use Values in Chukotka.” Études Inuit Studies 31 (1-2): 121–142.

- Yashchenko, Oksana E., 2020 “Nakonets-to ia doma: vozvrashchenie v rodnoi Akkani [Home at Last: Return to our Native Akkani].” In Prikladnaia etnologiia Chukotki: Narodnye znaniia, muzei, kul’turnoe nasledie [Applied Anthropology in Chukotka: Indigenous Knowledge, Museums, Cultural Heritage], edited by O. P. Kolomiets and I. I. Krupnik, 74–94. Moscow: PressPass.

List of figures

Figure 1

Map of contemporary and historic settlements

Figure 2

Pinakul, 2013

Figure 3

Pu’uten, 2013

Figure 4

Improvised fish smoker, Akkani, 2008

Figure 5

Contemporary hunting camp, Nuniamo, 2008

Figure 6

Closed and abandoned village, Nuniamo, 2008

10.7202/019713ar

10.7202/019713ar