Abstracts

Abstract

Historians of children’s reading highlight how the voices, opinions and ideas of actual children, are missing from most institutional archives. Contemporary scholars have an opportunity to change that situation for the future by co‑producing research with children. This paper examines how a class of ten‑year‑old schoolchildren in England engaged with a multidisciplinary arts project involving creative writing, digital game‑making and reading research activities. The paper builds upon scholarship that emphasizes the importance of conceptualizing research projects about children’s reading with reference to transliteracies, multimodality and creative reading. It argues that, by offering the children different forms and media of expression and various means of documentation, the project enabled them to articulate vernacular as well as schooled ways of reading. Significantly, the children’s perspectives on their own reading acts and habits offer valuable insights into the qualities of their reading experiences as child readers navigating a twenty‑first‑century transmedia environment.

Keywords:

- Child readers,

- twenty‑first century,

- arts‑based methods,

- multimodality,

- leisure reading

Résumé

Les historiennes et historiens de la lecture chez l’enfant soulignent le fait que la voix, les opinions et les idées des enfants se font rares dans la plupart des archives institutionnelles. Il est toutefois possible, pour les chercheuses et chercheurs, de remédier à la situation par la coproduction d’études avec des enfants. L’article propose l’exemple d’une classe, en Angleterre, dont les élèves de dix ans se sont investis dans un projet artistique multidisciplinaire alliant création littéraire, conception de jeux vidéos et activités de recherche sur la lecture. La littérature sur laquelle il s’appuie fait valoir l’importance de conceptualiser les projets de recherche portant sur la lecture chez l’enfant en se référant à la translittératie, à la multimodalité et à la lecture créative. Le projet cité en exemple offrait aux enfants des moyens diversifiés de documenter leurs idées au sujet de la lecture, par l’entremise de différents médias. L’article soutient que c’est ce foisonnement de formes d’expression qui leur a permis d’articuler des pratiques de lecture, tant les pratiques plus informelles que celles préconisées par l’école. Plus particulièrement, les perspectives des enfants sur leurs propres actes et habitudes de lecture jettent un éclairage précieux sur la nature de leurs expériences en tant que jeunes lectrices et lecteurs se frayant un chemin dans l’environnement transmédiatique du xxie siècle.

Mots-clés :

- Enfants lecteurs,

- xxie siècle,

- méthodes de recherche basées sur l’art,

- multimodalité,

- lecture de détente

Article body

Figure 1

When I read aloud walking around my bedroom I felt unstoppable!

Bryn’s notebook, Babbling Beasts project archive

For ten‑year‑old Bryn, reading is his superpower.[1] He recorded this insight during a series of experiments involving reading out loud in different physical positions. These experiments formed one set of explorative activities that I invited him and his classmates to undertake as researchers of their own reading. Their responses to my prompts and their ideas about reading far exceeded my expectations: the students were, in fact, “unstoppable” in terms of their imagination, creativity, and curiosity. Encouraging the children to be researchers of reading was only one element of “Babbling Beasts,” which was a collaborative, arts‑based research project involving reading, creative writing, and digital game‑making with a class of 30 ten‑year‑old children.[2] They had a lot of fun as they wrote and created stories together, inventing personalities and adventures for their “beasts,” whose material existence took the form of a furry pencil case, with simple technology enabling each beast to “babble” (or talk) using scripts that the children had audio‑recorded themselves. The children’s enthusiasm about making the beast story‑games was predictable, perhaps, but the eagerness that some of them showed in taking up the role of researcher was less expected and their observations about their reading habits were perceptive and intriguing.

As an adult researcher of reading, I learned from this class of 30 ten‑year‑olds that children can and should be co‑researchers and co‑creators of knowledge about reading. Moreover, the students convinced me that working alongside children and making something with them is a generative method for contemporary reading studies and book history research. Both the process (the actions of “making with”) and the products (an archive of documents and media objects including the beast stories) enabled the children to articulate schooled and vernacular ways of reading.[3] In other words, the children’s report on and expressions of their own reading acts and practices referred both to the proscribed materials and formalist techniques associated with their educational training and also to the eclectic range of texts they encountered throughout their daily lives, some of which they decoded in more personalized or idiosyncratic ways. As I will demonstrate below, the children’s perspectives on their own reading acts and habits offer valuable insights into the qualities of their reading experiences as child readers navigating a twenty‑first‑century transmedia environment. Before elaborating on those insights, I want to examine the significance of encouraging children to share their perspectives and the scholarship that inspired Babbling Beasts.

Why Researching Reading with Children Matters

My role as a co‑designer of the Babbling Beasts project was directly influenced by the work of two Canadian library science scholars, Lynn McKechnie and Margaret Mackey. McKechnie argues for including the perspectives of children in her research about “the intersection of children, reading and public libraries,”[4] and all her projects have done just that, even when the children involved have been babies.[5] Her focus on creative reading rather than on “schooled” reading, which involves specific reading techniques designed to boost children’s literacy levels, informed the emphasis of the Babbling Beasts project on creative reading as a resource that can fire the imagination.[6] Meanwhile, as Kimberly Reynolds points out, Mackey was “among the first established children’s literature scholars to recognize that computer games are forms of narrative.”[7] Mackey’s innovative investigations into children’s transliteracies—that is, how children learn about narrative through and across their engagements with different media—encouraged me to collaborate with two arts practitioners with expertise that I did not possess myself: John Sear, a games developer, and Roz Goddard, a poet.[8] We co‑designed a project that involved children employing different types of creative expression—writing, reading and game‑making—in our effort to answer our over‑arching research question about how digital media might offer a pathway into pleasure reading as a resource for life.

The analysis of children as readers and researchers of reading that I present below is also in dialogue with Kimberly Lenters’s research as a scholar of elementary education, work that I encountered after the Babbling Beasts project had ended. Lenters advocates for the arts as a field that offers creative modes of “making” as a research method in the classroom. She also argues for the involvement of arts practitioners such as comedians and actors as collaborators in the classroom. Significant to my own observations of the children’s reading practices is Lenters’s conceptualization of multimodality, which goes beyond children’s co‑extensive uptake of print and e‑books to consider how “affect, embodiment and place can enhance both multimodal literacy instruction and children’s engagement with literacy.”[9] While the design of our Babbling Beasts project as a whole focused more on children’s creative engagement with different creative practices, forms, and technologies, the design and implementation of the children’s reading research activities in particular resonates with Lenters’s critical thinking about multimodality because of the emphasis we placed upon feelings and the visceral experience of reading, and our attention to the sites or situatedness of reading acts.

My analysis of Babbling Beasts illustrates some of the reasons why children should be co‑researchers in contemporary investigations about reading in a transmedia age. Some compelling reasons why participatory research with children is crucial to producing nuanced analyses of children’s texts are addressed by Justyna Deszcz‑Tryhubczak.[10] She notes “the unpredictability of children’s responses to literature” that are often omitted from adults’ textual analyses.[11] As she points out, adult critics construct their own ideas about how or if a text addresses social justice issues or how engagingly it represents early life experiences, and this is to the detriment of our collective understanding of how to effect social change. She challenges literary critics “to revise our often undaring thinking about children,”[12] and to adapt models from educational settings that would enable “adult‑ and child‑led reader response research.”[13] My discussion of Babbling Beasts indicates some possible methods for this, while it is also a case study that contributes to an imagined future history of children’s reading where there could be a wide‑ranging and dynamic archive that has been co‑produced by and with children.

Such an archive would address some of the constraints identified by historians of children’s reading.[14] As Matthew Grenby notes in his study of the eighteenth‑century British child reader, where he combines methodologies from book history with those from literary studies, “genuine accounts of historical children’s actual activities and attitudes are notoriously difficult to come by.”[15] The problem continues with a different inflection into studies of late nineteenth‑century children’s reading in North America. Kathleen McDowell explains how the “actual voices of child readers” are often missing from historical and educational studies.[16] This absence exists in part because the librarians, teachers, and educators conducting the surveys that elicited children’s opinions had authority over them, and the children were thus put in a position where they “described their reading experience to adults who were concerned with training [them] in good reading habits.”[17] I cannot claim to have entirely resolved these issues of power and ideological skew through the design and process of Babbling Beasts. After all, I worked with the children in my professional capacity as a university‑employed researcher with an explicit investment in the notion that reading for pleasure is a valuable pursuit. I believe, however, that the children’s multimodal expressions of their reading lives at home and at school, written, drawn, and verbalized in notebooks, on cardboard boxes, and in sound files strongly suggest how, when offered multiple means and modes of expression, children can articulate their ideas and opinions about reading with less pressure to offer adults the “right” answers.[18] Babbling Beasts thus represents one attempt or experiment in working with children on a creative project that elicited their attitudes and experiences of reading in both expected and unexpected ways.

Situating Babbling Beasts: “Reading is Cool” at Old Hill School

BB is fun. You can use your imaginations as freely as you want, so be prepared. You use phones, special cards and boxes. Don’t worry ‑ they buy them.

Year five student, “Message to other children,” Project Evaluation

“Babbling Beasts” refers to both a process and a product: children used “phones, special cards and boxes” to make tangible objects, but they also engaged in an imaginative process as part of a multidisciplinary arts project. The Babbling Beast as product is a story‑game that has been composed and audio‑recorded by the player‑participants using an old smartphone, bespoke software, and some Near Field Communication (or NFC) cards. When the beast, a furry pencil case containing the smartphone, is held up to an NFC card, the animal character starts to talk and the story begins. The story that the participants have made is recorded in several parts stretching across several cards, typically between five and eight. These cards can be stuck on objects or dotted around a space or throughout a series of rooms. Simple objects like cardboard boxes can also serve as “stations” for the Babbling Beasts story‑games—as they did during a Celebration event for families held at the end of our workshop series in April 2018.

Figure 2

Figure 3

The frame for the process of making the Babbling Beasts was a workshop of six two‑hour sessions for a class of ten‑year‑old school children, which involved John Sear, Roz Goddard and me spending time with them in their classroom during their school day. The 30 students were in year five at Old Hill Primary School in the West Midlands (England), and the workshops were scheduled across four months, January to April 2018. In the academic year 2017–18, year five consisted of 20 boys and 10 girls: approximately 30% were Caucasian; about 30% were descended from people who left India and Pakistan in the 1940s and 1950s; and the rest of the class were the children of immigrants from Turkey, Bulgaria, Singapore and Poland, or were themselves recent immigrants from Russia, Ghana and Hungary. When the school schedule permitted it, we used the school hall for the workshops rather than the cramped confines of year five’s classroom, which resulted in half of the Babbling Beasts workshops taking place in each space.

Each workshop in the Babbling Beasts project combined creative writing, reading research activities, and digital story‑game making. During each in‑class session, the children engaged in warm‑up games with words, story‑making, and, when space allowed, physical movement. Using prompts created in advance of each workshop by our team, the children wrote dialogue, poems, and story fragments; discussed their investigations into different types of reading; and worked in groups of three on their Babbling Beasts stories, rehearsing, recording, and playing back their sound files. They used large blank‑paged notebooks that we gave them to write, draw, cartoon, scribble, decorate, glue in their homework activity instructions, and note down any thoughts about their evolving Babbling Beast story. We encouraged them to use the notebooks outside the workshops, and most children did. We also invited them to use the notebooks as a means of recording their research findings about reading while they were doing the research activities at home.

Most students, like the child quoted above, thought the workshop format was “fun.” When asked to prepare a short message that could be sent to a future class of school children about to embark on the Babbling Beasts project, one student created a short poem that articulated both the enjoyment (“the fun ride”) of doing activities that “will make you use your imagination,” and the affect (“the fun inside”) that they experienced during the process. They wrote, “Babbling Beasts will make you use your imagination, get ready you’re in for a mad creation. BB [sic] will take you on a fun ride. Also, they will make it really fun inside.” This child’s creative articulation and analysis of the Babbling Beasts experience accords with Lenters’s conceptualization of multimodal reading as involving embodiment and affect. Their poem identifies what was stimulating about the “mad creation” both imaginatively and emotionally. But, as another student indicated, the mix of activities was also intellectually demanding and tiring. They advised future students:

Make sure you have a good night’s sleep, because the warm‑up exercises get your brain full of ideas. They also have beasts which you can make your very own game about. Also, you get your own BB notebook. Hope you enjoy it because you can really make a difference with your reading.

How the project could “make a difference with your reading” goes unexplained here, and it is possible that this participant is simply reiterating the team’s aim as it was represented to the class through written and verbal communications about the project. Significantly, the tagline we created for Babbling Beasts—“Explore Reading. Tell a Story. Make a Game.”—was visible on the colourful banner that we set up and displayed at each workshop (see Figure 2). However, the idea that “get[ting] your brain full of ideas” might be connected to ways that a student can improve or change their reading is linked to other children’s expressions of and about reading that emerged across the project: what they think it is, what it does for them, and what they like and do not like about it. For example, as part of the final Celebration event, the children worked in their Beast teams to decorate a large cardboard box which was to serve as a “station” for the NFC cards. Several children wrote and/or drew their ideas about reading. One girl made an illustration of a human figure inside the pages of a book and added the words “Blasting into space with imagination” beside it. Another child wrote on their box, “when you read, you are taken to another dimension of paradise.” These children conceptualized reading as a powerful and inspirational force, capable of transporting the reader out of their everyday realm, and generative of pleasure, while a third child copied out what appeared to be a quotation, “If you are going to get anywhere in life, you have to read, read, read!”

The first two children are vividly describing their experiences of “creative reading,”[19] while the third child is directly referencing the culture of reading at Old Hill Primary School, where their teachers read aloud to them, and time was set aside for silent reading every day.[20] Reading—especially the reading of fiction—is an integrated, not an “add‑on,” activity at the school.[21] For the staff, these daily practices of reading are thus about much more than implementing curriculum requirements and improving literacy, because they also enact an ideology of reading as socially transformative. While showing us around the school before the project began, the Head Teacher Sally Fenby told me, “Reading is the children’s pathway out of poverty.”[22] The demographics of the pupils at Old Hill Primary School help to contextualise Fenby’s remark, since they hit every marker used in the education system of the United Kingdom to identify low socio‑economic factors: over 80% of the pupils have free school dinners, there is a breakfast club before school begins, and free toast is offered as a mid‑morning snack. The teachers, supported by several excellent classroom assistants, understand training students to read a range of texts, including adapted Shakespeare and science writing, as essential preparation for secondary school. Once there, the children will be expected to study various genres and styles of written communication, and they will mix with children who have more cultural capital than they do.

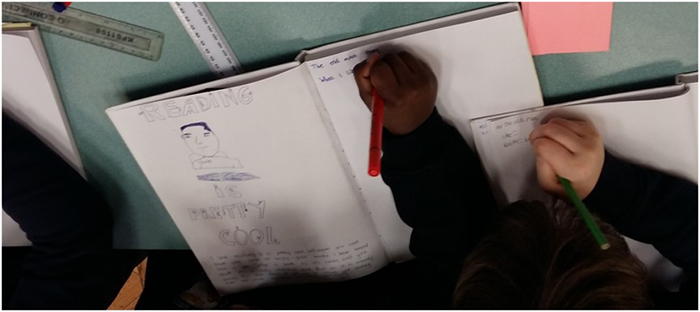

Subsequently it is not surprising that the physical environment of the school manifested an overtly positive approach to book reading through colourful displays on classroom walls, including an evocation to “Read, read, read!” in year five’s room, wall‑to‑wall shelves of books in spite of limited classroom space, and a vibrant Harry Potter‑themed banner in the school’s multipurpose hall, declaring “No story lives unless someone wants to listen.” Several members of year five were avid readers who were clearly benefitting from the school’s culture of reading and regarded it as a pleasurable and relaxing activity as well as part of their learning. Tommy drew a self‑portrait of himself reading a book in his Babbling Beasts notebook and wrote beside it, “I love reading. It is pretty cool because you can have free time to enjoy your books.”

Figure 4

Three other children also drew codex books or pictures of a child reading. Other children resisted the “conscripted” reading required of them by the school curriculum,[23] noting that “I hate reading when I have to do it.” Given the emphasis that their teachers placed on reading together every day, it is understandable that some members of year five were very receptive to the invitation to explore aspects of their reading lives as researchers, while other students were reluctant to think about a habit that was so firmly embedded within their school day. Giving the children a choice about whether or not to undertake the reading research aspect of the project was not only an ethical decision in keeping with the voluntary ideal of qualitative research, but also one way of respecting their agency and capacity to make a decision about which activities they liked and disliked. Their parents were aware of the project as a whole and gave their formal consent for their children to participate in it, and for the team to use the notebooks, Beast stories, and photographs in our analyses and publications. The parents who attended the launch event were told about the “at‑home” activities, and the information sheets (one for parents and one for the children) that accompanied the consent forms also described these activities. Consequently, about half of the class undertook one or more of the five “at‑home” research worksheet tasks. Their observations are discussed below.

“At‑Home” Research Activities: Acrobatic Reading and Other “Dynamic” Results

“I read aloud to my brother while bouncing on the bed. He fell off!”

Jake’s notebook, Babbling Beasts project archive

As the outcome of this particular experiment suggests, the children who pursued the “at‑home” research activities produced some dynamic results! Prompted by the first research worksheet to read aloud to a pet, family member, or friend from a book of their choice, they also explored how it felt to read aloud in different physical positions such as sitting, lying down, and walking around. Another boy also found that his attempt at social reading with a sibling had a propulsive effect: “I read to my little brother. He ran away!” A further important discovery was that doing backflips on a trampoline while reading means it is very difficult to hold on to the book! Such “acrobatic reading” contrasts to the children’s observations that reading aloud to yourself while lying down felt “calm,” “relaxed,” “peaceful,” and “comfortable.” Notably, grandparents, siblings, and mums were all “read aloud to” but only one dad was mentioned. Evan read to his dad and his mum, and his shared reading appeared to be both pleasurable and sociable. He recorded in his notebook that he “felt happy and chilled because it was fun to talk and have conversations with my mum.”

The five “at‑home” activity worksheets that prompted students to become researchers of reading were co‑designed with DeNel Rehberg Sedo. We drew on our previous experiences of working with adult readers in terms of understanding reading as a social practice, by which we mean a situated act that takes place in a specific time and space and that is supported by a “social infrastructure,” including access to reading materials and formal literacy education.[24] Our previous research projects had foregrounded some of the reasons that adult readers value leisure reading, including its capacity to remove them from their everyday world, to teach them about different realities, and to produce a feeling of relaxation.[25] These ideas about reading arise from what I have referred to elsewhere as “vernacular” practices of reading, in the sense that they are mundane, everyday actions.[26] Vernacular ways of interpretation do not require specialist vocabulary or scholarly training. With reference to year five, vernacular acts of reading can be differentiated from the proscribed reading they do for school and the “schooled” ways of reading which require specific literacy skills and interpretative techniques.[27] Our design of the children’s research activities deliberately emphasised vernacular reading; the idea that reading materials could be anything from a printed book to text messages to a cereal box, and the notion that reading is an embodied act that produces physical and affective effects as well as emotional responses. Thus, the first “at‑home” worksheet invited the children to “explore how reading feels in your body when you read out loud in different postures,” and the fourth one asked them to investigate “the different types of reading we do and where we do it.”

In taking this approach we were (unknowingly) echoing Kimberley Lenters’s recognition of “the body as a site of multimodal literacy” which responds to texts viscerally and emotionally as well as cognitively.[28] She notes that what attracts students to a text is often something that “they are not able to name or identify through words,” so offering children different ways of expressing how a text (whether it is a book, poem, or game) appeals to them can be a useful strategy for any project that is examining what students learn “as they produce or consume multimodal texts.”[29] During the Babbling Beasts workshops, we encouraged the children of year five to write, speak about, perform, and record not only aspects of their Babbling Beasts story‑games, but also to draw, write, and discuss their reading research and ideas about reading. For their “at‑home” research activities, they were given options to draw as well as write, and the second worksheet explicitly invited them to ask for and listen to oral stories—to “collect some of the different types of stories that surround us”—by engaging in conversation with adults at home or with friends. The worksheet prompted the children to write down the key elements of the stories that they had heard, and several children orally retold a story using their notes during the subsequent workshop.

Year five’s choices of favourite and least favourite reading spaces and environments were initially explored as part of the first “at‑home” activities worksheet and then discussed as part of the following workshop. These preferences indicate what, in their experience, makes for optimum reading conditions. Kaden noted, “I like to read when I’m at home,” and “I don’t like to read when I’m with my little brother.” Similarly, Kegan reported that “I don’t like reading when my brother annoys me.” While reading to friends, siblings, or other family members was variously described as “joyful” and made several children feel “happy,” others emphasised their requirement for quieter, more private reading spaces. Shared living rooms and busy areas of dwellings were not popular with the children. Declan wrote, “I don’t like reading downstairs,” and Khalid volunteered that he enjoyed reading “in bed” because it influences his dreams. During the in‑class discussion, several children confirmed that “upstairs”, “in bed,” and even “on the stairs” were the best places to read if you shared a bedroom. In the latter case, “comfy couches” and “fluffy carpet” also offered some students a relaxed and relatively undistracting place to read when at home.

Preferred reading spaces were also a topic featured in the fourth “at‑home” worksheet. We asked the children to record all the different types of reading material that they encountered in one day, to identify where they were for three of the examples, and to select their favourite space or place from those three. The children who responded checked off at least five items in the list, demonstrating extensive reading habits. They sometimes distinguished between where they like to be when they are reading for information—in Amalya’s case, “at my nan’s house”—versus for pleasure, such as reading comics while “lying down” (Amalya) or “in bed” (Khalid). In Andy’s case, he identified three different types of reading material that he associated with reading acts in different spaces: “news… in the kitchen,” “comics … I was in a chair,” and “fiction … in school.” He cited the latter as his favourite because “it is quiet.” Aidan listed texting while “on the couch” as one of his favourite modes of reading alongside reading a book in bed or reading comics on the floor, because being “warm” or “comfy” while reading is important to him. Sophie noted her favourite type of reading as “texting because I get to talk to people,” suggesting the embeddedness of read‑write communications in her daily life.

What emerges from year five’s commentaries on their own reading acts and preferred reading spaces produces an incomplete yet compelling portrait of their vernacular practices. Like the children in Lynn McKechnie’s research studies, year five children have opinions about the different reading materials they like to read and where best to do a particular type of reading. Moreover, they may be children who grew up in an era of smartphones, tablets and computers—all devices that they reported using when asked about this during a class discussion—but they also enjoy paper comics and print books. More than a decade on from Margaret Mackey’s important analyses of the transliteracies that children develop, the students of year five wrote about and discussed how they move among media almost constantly as they read—from cereal box to X‑box—every day.[30] How this intensification of multi‑device use, multimedia engagement, and extensive reading might inform their transliteracies was beyond the scope of the Babbling Beasts project, but the children’s observations indicate that they could have had more to say about it. Something that the children made very clear to me as a researcher, for example, was that their transliteracies also involved and were inflected by the languages that they knew how to speak, write and/or read.

The fourth of the five “at‑home” research worksheets enquired about the languages the children could read in, and this resulted in one of the liveliest classroom conversations of all. Khalid reported reading in English and Arabic—using Arabic mainly at the mosque. Another boy, Tarek, could speak Arabic, English, Punjabi, and Urdu, but he commented that he could not read well in all these languages so considered Arabic and English as his reading languages. Ruth read the Bible in Italian, did her school reading in English, and watched television using subtitles in Akan. Bryn explained how year five were learning Spanish in school, so he tried to practice reading in Spanish at home, looking up things to read online. Sophie read English, Cantonese, and could speak a language from Hong Kong the name of which she didn’t know. She shared with us that her reading in Cantonese was limited because she was less familiar with it. Sasha noted that he could read in Romanian, Russian, and English: he read fiction in Russian and obtained those books from the public library. Karolina read in Bulgarian, Russian, and English: she also got books in Bulgarian and Russian from the local library. She reported that it did not matter to her what type of reading material it was—she would read all types in all languages. These insights into the children’s multi‑lingual reading habits suggested other ways in which their vernacular reading might bring them pleasure and enjoyment. For some children the ability to read in more than one language meant that they could connect to multiple generations of their immediate family and to a linguistic community that is both local and diasporic in its geography. For others, being able to read the sacred text of the religion that they practiced enabled them to be part of a faith‑based reading community. Meanwhile, the high‑energy discussion that this research activity prompted suggests that the children would have been enthusiastic about investigating these issues and this aspect of their reading lives still further.

Even when aspects of their reading research felt “weird,” such as reading aloud while walking around a room which made one girl feel “dizzy” and another “uncertain,” the children proved adept observers of their embodied reading practices and environments. About a third of the class thoroughly embraced the role of researcher, diligently completing four of, or all five of, the “at‑home” activity sheets, and including both drawings and text in their responses. These same students asked clarifying questions when I introduced the worksheets at the end of a workshop such as “does reading football results on Google count?” or “can I do this with my sister?” As a class group, the children demonstrated great enthusiasm whenever their ideas, research findings, or opinions were sought. Arms shot into the air, bodies bounced in seats, and when our independent evaluator gave out a feedback sheet about the project for them to fill in, the children burst into spontaneous applause. This sense of fun and joy was inspiring for the Babbling Beasts team, and the children’s energy for the project gave us confidence to continue even when our ambitious attempts to integrate the creative writing, reading, and game‑making elements into each workshop proved challenging. Until the Babbling Beasts games were completed and the notebooks handed in for me to copy, I did not realize how effective these media were as alternative ways for the children to express their ideas about reading.

Alternative Media and Modes of Reading Research: Notes, Drawings, and “Beasts”

I like reading in my calm room

It feels good

My favourite book is Minecraft

I hate reading Harry Potter

Andy’s notebook, Babbling Beasts project archive

Nearly every child’s notebook had a version of Andy’s written responses quoted above because, during the first in‑class workshop, I asked year five to write down when they like to read, when they don’t like to read, what their favourite thing is to read, and what they hate about reading. These prompts were deliberately provocative but were also intended to encourage the students to identify negative as well as positive reading experiences. In response Liam wrote, “I like reading when I’m bored. My favourite thing to read is Minecraft books. I don’t like reading when I’m downstairs. I hate reading girl books.” In common with Andy and at least two other boys, Liam’s preferred book choice is informed by his love of an online game (Minecraft). Tarek offered another perspective on his relationship with gaming and reading when he noted: “I like to read at night. I don’t like reading when on PS4. My favourite thing to read is The World According to Clarkson. I hate reading game instruction manules [sic].” His aversion to instruction manuals and “reading when on PS4 [Playstation]” may suggest a desire for immersion in the world of an online game uninterrupted by textual narrative and information.

A minority of children favoured nonfiction genres such as instruction manuals, and sacred texts such as the Bible and the Qu’ran were also important to about half of the class. Tarek was one of very few students who chose a nonfiction book, and one aimed at an adult readership and written by a television celebrity—a book that perhaps belonged to an older member of his household. He used his notebook extensively outside class, filling it with stick figure drawings, research notes from the “at‑home” activities, and cut out photos of a small table that he made with this grandfather on a rare English “snow day” when the school was shut. Using his notebook as a type of diary, he chose to record that event, alongside other glimpses into his family life and situation, such as the following entry: “My dady brought a PS4 out of the blue. I don’t know what reson he bought it for. However, me and my brother were very surprised and happy.” These examples all suggest how co‑extensive these boys’ reading is with other hobbies and media, as well as hints of intriguing differences in their relationships to games and books.

Meanwhile, Declan’s strong reaction against “girl books” perhaps reflects the binary gendering of popular culture products (including colour palettes used on book covers) for his age group, although, unfortunately, there was no opportunity to ask if he had specific genres or titles in mind when he wrote this in his notebook. Girls in the class did not reference online games in their preferred book choices, although when we asked during a workshop, some of the girls did report that they enjoyed playing online games. Sophie and Amalya both listed Dork Diaries as their favourite thing to read—a middle‑grade fiction series by American writer Rachel Renee Russell, which has achieved international bestselling success. Russell’s series, written in diary format and including doodles, cartoons, and comic strips, is accompanied by a lively and interactive website.[31] Featuring a 14‑year‑old girl protagonist and a multi‑racial group of friends, the series is clearly marketed to preteen girls, so perhaps this is the type of book that elicited disdain from Declan. Other favourites nominated by girls in the class included another series, Rose Muddle Mysteries by Imogen White. These books (also categorized as middle grade) are set in the south of England and described by their publisher Usborne as “thrilling Edwardian adventure(s).”[32] Meanwhile, avid reader Karolina wrote down a genre description for her favourite thing to read: “adventure magical stories.”

The Babbling Beasts notebooks offer other glimpses of books that students liked to read: bestselling children’s fiction series such as Diary of a Wimpy Kid (written and drawn by Jeff Kinney) and Horrid Henry (written by Francesca Simon and illustrated by Tony Ross) received multiple mentions, alongside Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, a “classic” novel in the canon of British children’s literature which year five had read together in class the previous school year. Notably, all these titles have been adapted into at least one other medium, and it is possible that the children had discovered Wimpy Kid and Horrid Henry through television, or that they had recommended these books to each other. Both book discovery methods are highlighted by David Kleeman in his discussion of challenges the book industry faces “getting books into kids’ hands” during the second decade of the twenty‑first century.[33] Kleeman also notes that in data from the United States and the UK, “almost 60% [of the children] want to share books they loved, especially primary‑aged children.”[34] It is also possible that some of the titles were available to borrow from the school library, although none of them had been selected as “class reads” or for study. Recommending books, having teachers and friends suggest books to read, and borrowing paperback books were certainly practices that were all familiar to these year five children. During the discussion about favourite and hated books, several children mentioned visiting the public library to borrow books, and their own school classroom had a small selection of paperbacks for leisure reading.

While the children were explicitly asked to list books they liked and did not like, they were only invited (not requested) to draw in their notebooks; it was a suggestion which carried less obligation to the Babbling Beasts team, since they were not required to report back on it or to discuss it. The children’s drawings thus offer a less coaxed perspective of their attitudes and opinions. For example, a few of the children’s Babbling Beasts notebooks contained images that articulated a strong connection to printed books. Four children drew a picture of a reader or a codex book. There were some real reading enthusiasts like Tommy, who drew a self‑portrait entitled “reading is cool,” and Karolina, who drew a girl (maybe herself) reading. More of the children (both boys and girls) indicated their enthusiasm for and knowledge of comics and graphic books, as well as animation and online games, through their style of drawing. Figures inspired by Japanese anime recurred, while imagery from the game Fortnite was especially popular with some of the boys. Kaden, who was a talented artist as demonstrated by the many cartoons and drawings he made in his notebook, wrote, “I hate reading when I don’t see pictures.” Both multimodal texts and multimodal reading practices were evident in the pages of the “Beast books” that the children created. The children expressed their various passions for drawing, bestsellers, comics, and gaming through cartooning, sketching, doodling, and fragments of writing. Their “actual voices” and perspectives about media, books, and reading are present in the pages of these semi‑private notebooks, just as much as they were articulated verbally during in‑class discussions.

Finally, the Babbling Beasts story‑games that the children made can also be understood as another medium through which their reading preferences and media practices were expressed—albeit subtly. Their story‑games contained genre and plot elements that suggested the influence of the online games, television shows, books, and genres that they enjoyed. Magical portals or gateways into alternative universes were especially popular, echoing, perhaps, the world building aspects of Minecraft as well as the “adventure magical stories” that Karolina had identified as her favourite genre to read. The material form of the Beasts (furry pencil cases representing different animals) and our invitation to the children to create a story that involved a journey featuring some challenges for their Beast are also factors that informed their genre and narrative choices.

Figure 5

Aliens, monsters, and spaceships were part of three Beast stories, again indicating the children’s interest in other universes and alternate realities commonly found in various media forms of fantasy and science fiction. The influence of games like Fortnite and animation featuring “Battle Royale” scenarios emerged in the propensity of the Beast team threesomes to craft scenes where their Beast had to slay an opponent or shoot their way out of an ambush. A couple of teams introduced violent murders early on in their stories, suggesting a love for dramatic plot twists and a knowledge of sudden death that is common to television melodrama, crime dramas, and thrillers, but is also sometimes a component of fantasy and science fiction across media and platforms. Team “Quacker the Duck,” for example, pitched a drive‑by gang‑style shooting as their starting point, until we persuaded them that extinguishing your main character at the beginning of the story‑game was somewhat counterproductive!

In common with the notebooks, the Beast stories suggest how reading, gaming, television watching, and film viewing are not only co‑extensive media practices for the children of year five, but also that the students used a fairly sophisticated set of transliteracies. When asked to use their imagination, the children created artefacts that drew upon topics that were important to them, like family, and used familiar narrative styles that they enjoyed as media consumers and as readers. Some aspects of their creations also indicated how the children’s attitudes to social identities were commensurate with progressive ideas about gender. These expressions were in tension with the gendering of “girls’ books” cited above. For instance, most teams gendered their Beast in binary terms as male or female, but the qualities they ascribed to them did not necessarily align with sexist stereotyping or gender binaries, reflecting perhaps the children’s familiarity with reading about and viewing heroes and central protagonists who could be boys or girls. Felicity the Fox, for example, was female and had attributes commonly associated in the United Kingdom with foxes—she was clever and quick‑witted, but also thoughtful and contemplative. Meanwhile, Angry Andrew, the male name given, perhaps somewhat predictably, to the Beast with sharp teeth, spent his Friday nights “at biting classes,” but also “loved his family.” Angry Andrew’s story‑game was crafted by his team into a coming‑into‑your‑identity type narrative: his adventure taught him to use his biting abilities only in extreme, life‑threatening situations. Some teams did not adhere to binary roles for their Beast names and attributes: Olive the Owl, for example, was assigned “he/him” pronouns by his team, while Frankie the Frog alternated in the recorded story between “him” and “they.”

I have no evidence to suggest whether these were deliberate choices or grammatical errors, but it is possible that some of the children had gained awareness about gender‑neutral pronouns from popular culture, or from friends and family. Certainly, the ability for a gamer to create an avatar who was nonbinary, gender fluid, or transgender was limited to a very few online games in 2018, and middle‑grade fiction in English was only slowly catching up to the notion of fluid or multiple genders.[35] It is also possible that the children’s choices for their Beasts reflected their own lived experience; for example, identifying as a boy or girl in public, but understanding themselves as nonbinary or gender fluid. Perhaps what the children’s characterisations of their Beasts most strongly demonstrates is how the multimodal format of the project enabled some of the children to experiment with ideas about gender and gender expression, even as some of the books they read and other media they enjoyed pulled them in different, and sometimes contradictory, directions.

Concluding Discussion: Making Archives and Messiness

The children’s notebooks, drawings, and Beast story‑games indicate their knowledge of specific genres, plotting, and gendered protagonists learned from various media, while their findings as researchers of reading offer glimpses into how they feel when they read, where they like to read, when they don’t like to read, and intergenerational reading practices. For researchers of reading this small archive of media objects goes some way to address the concerns raised by scholars such as Matthew Grenby and Kathleen McDonald about the absence of children’s perspectives and voices from much of the historical record of children’s reading. Meanwhile, the children’s uptake of the multimodal forms of expression that they could employ to represent their opinions about and experiences of reading resonates with Lynn McKechnie’s creative project designs, Margaret Mackey’s early insights about children’s abilities as interpretive users of multiple media, and Kimberly Lenters’s dynamic conceptualisation of multimodality as embodied, situated, and involving affect. In these respects, Babbling Beasts builds upon extant scholarship about children as readers and extends it to indicate that “making with” children can be a generative way of encouraging them to be researchers and commentators on their own reading experiences. The opportunity for in‑class group discussions about reading as well as the explicit connections we made between aspects of the optional reading research activities and the hands‑on “making” elements of the Beast story‑games undertaken in class time were important to facilitate the children’s reading researcher role. For example, we deliberately linked the recurring topic of reading spaces to the task of imagining the spaces that their Beast inhabited at different story stages. The multidisciplinary arts‑based design of Babbling Beasts encouraged children to reflect on their reading habits, write poems, draw in various styles, and record a simple digital story‑game. The team’s emphasis on using your imagination across all the project elements took the children on a “wild ride” that most of them enjoyed, which suggests that having fun was just as important as being taken seriously.

Figure 6

Nevertheless, it was not all fun and games. The team’s attempts to weave together creative writing, reading, and game‑making also produced incompleteness, messiness, and dissatisfaction. Many pages of the notebooks were left blank. Glue ran out. Scribbles and half‑finished sentences adorned both notebooks and the cardboard boxes. Some story‑games were confusingly plotted in spite of a workshop on editing. There were surprised looks on the faces of some family members who came to the Celebration event when the homework activities were mentioned, which suggested that some children had ignored or thrown away the worksheets. The class teacher for year five felt that the standard of writing shared by the children at that event was below their usual level. Students proudly instructed visitors on how to activate their Babbling Beast story by guiding their caregivers around the cardboard boxes in the school hall, but one student wrote (anonymously) in their final evaluation: “Some parts of BB are fun. Most of it isn’t. There isn’t actually a lot about reading or writing. You don’t get to put in many of your own ideas. Don’t get your hopes up. It can be extremely boring at times.”

This child’s comment suggests that “making with” children as a mode of research for reading studies and book history needs to involve more co‑production and co‑design than we achieved with Babbling Beasts. More input from the children about the type of activities they wanted to pursue with our help would have made it more organic and ground‑up in terms of process and with regards to “what” got made. Their teacher’s disappointment indicates that closer collaboration with her, perhaps through a much longer lead‑in time prior to the workshops, would have given us useful information about the children’s scholarly abilities and additional insights into the school’s expectations of year five as writers and readers. As it was, we were only able to meet with her and a small group of teachers before the run of workshops began. Their demanding work schedules meant that brief email communications, snatched moments of conversation at the end of workshops, and written responses to some interview questions constituted their involvement in Babbling Beasts. The class teacher for year five was only able to be present for some of the workshops during which she would participate by joining the team in helping the children. The time‑pressed aspects of a primary schoolteacher’s job emerged very clearly when the rigours of a curriculum that involves near‑constant testing resulted in children being taken out of one of the workshops by their teacher for about ten minutes each for individual reading tests. With more time and more conversations with teachers, we might have found different ways of working that would have enabled the class teacher, in particular, to bring her expertise and ideas into the co‑design of the project.

Finally, the material messiness that was produced deserves some consideration. The messiness I’m referring to here ranges from the scrunched‑up sticky notes identified above to paper‑strewn workshop spaces, from the children’s unfinished creative writing assignments to the scribbles and freeform design of the cardboard box stations. How can we understand such messiness as part of the children’s expressive actions? Is it a sign of resistance to “schooled” ways of reading and doing creative projects, or a reluctance to entertain adults’ desires for them (for example, those of their teachers who often display their students’ best work triple‑mounted on classroom walls)? Or should messiness be conceptualized as a type of hacking of adults’ instructions that children often use to derail or reimagine the well‑intended ideas of their elders? I would suggest that the untidy and incomplete aspects of Babbling Beasts were themselves a valuable part of a research process that produced an archive that should not be forced to make coherent sense. Intriguingly, Margaret Mackey makes a parallel point in her most recent study of space and place in the reading lives of a group of young adult readers. Mackey draws attention to “the inherent messiness of reading” as an internalized and imaginative series of acts,[36] and, in her conclusion, underlines the point that “messiness is not a deficit but a feature.”[37] While we are referring to different manifestations of messiness, the ways that the year five children’s material messiness might also relate to, or be influenced by, their experiences of reading suggest another potential pathway for future investigation.

Messiness, or rather everyone making a bit of a mess, certainly provided as much of a creative environment during workshops as the warm‑up games and the team’s instructions for specific tasks. It reminded us all—children and adults alike—that using your imagination and creativity requires playfulness, getting it wrong, and, at times, abandoning what you are making. The example of Babbling Beasts suggests to me, as a scholar of reading as a social practice, that “making with” children as researchers of reading is a mode of engagement that requires further experimentation and theorization. In the case of Babbling Beasts, the children of year five at Old Hill Primary School co‑produced an archive of their reading practices that is multimodal, and multimedia: an archive that expresses both their ideas about reading and its imbrication in their daily lives. Their work also articulates the “fun ride” of a creative project alongside the “unstoppable” sensations that reading may bring a child.

Appendices

Biographical note

Danielle Fuller is a Full Professor in the Department of English and Film Studies and an Adjunct Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Alberta on Treaty 6. Before emigrating to Canada in 2018, she worked at the University of Birmingham, UK, for 21 years. Her interest in lived experience as a form of knowledge threads through diverse research that takes up a range of methods. Publications include two monographs, Writing the Everyday: Atlantic Women’s Textual Communities (2004), and, with DeNel Rehberg Sedo, Reading Beyond the Book: The Social Practices of Contemporary Literary Culture (2013). They co-edited “Readers, Reading and Digital Media,” a themed issue of Participations (May 2019). They are also co‑authors of the minigraph Reading Bestsellers: Recommendation Culture and the Multimodal Reader (Cambridge University Press, 2023). Danielle is currently collaborating on a SSHRC‑funded project about the uses of memoir reading and social media.

Notes

-

[1]

All the children’s names have been changed to protect anonymity in accordance with the research ethics approval received for the project.

-

[2]

The full project title was “Babbling Beasts: Telling Stories, Making Digital Games. Investigating Creative Reading and Writing for Life.” Funding was provided via an Arts Council England Grant for the Arts award and the Impact Fund at the University of Birmingham, UK, 2017–18.

-

[3]

Danielle Fuller, “Listening to the Readers of ‘Canada Reads,’” Canadian Literature 193 (Summer 2007): 11–34; Elizabeth Long, Book Clubs: Women and the Uses of Reading in Everyday Life (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003).

-

[4]

Lynne (E.F.) McKechnie, “‘I Readed It!’ (Marissa, Four Years). The Experience of Reading from the Perspective of Children Themselves: A Cautionary Tale.,” in Plotting the Reading Experience: Theory, Practice, Politics, ed. Paulette M. Rothbauer et al. (Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2016), 250.

-

[5]

Catherine Sheldrick Ross, Lynne McKechnie, and Paulette M. Rothbauer, Reading Still Matters: What the Research Reveals about Reading, Libraries, and Community (Libraries Unlimited, 2018), 96–98.

-

[6]

McKechnie, “‘I Readed It!,’” 258.

-

[7]

Kimberly Lenters, “Multimodal Becoming: Literacy in and Beyond the Classroom,” The Reading Teacher 71, no. 6 (May 2018): 643–49, https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1701.

-

[8]

Margaret Mackey, Literacies across Media: Playing the Text, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 2007).

-

[9]

Ibid., 643.

-

[10]

Justyna Deszcz‑Tryhubczak, “Using Literary Criticism for Children’s Rights: Toward a Participatory Research Model of Children’s Literature Studies,” The Lion and the Unicorn 40, no. 2 (2016): 215–31, https://doi.org/10.1353/uni.2016.0012.

-

[11]

Ibid., 217.

-

[12]

Ibid., 218.

-

[13]

Ibid., 222.

-

[14]

An example of an open‑access archive that includes some accounts of childhood reading in the UK during the eighteenth‑ and nineteenth‑centuries, with a few examples of child‑authored records, is the Reading Experience Database (RED). “UK Reading Experience Database—Home,” accessed January 14, 2022, http://www.open.ac.uk/Arts/reading/UK/.

-

[15]

Matthew Grenby, The Child Reader, 1700‑1840 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 11.

-

[16]

Kathleen McDowell, “Toward a History of Children as Readers, 1890‑1930,” Book History 12 (2009): 243, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40930546.

-

[17]

Ibid., 243–44.

-

[18]

On the importance of offering children and young people different ways of responding to research about reading, see Evelyn Arizpe and Morag Styles, Children Reading Picturebooks: Interpreting Visual Texts, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 2016), 186; Evelyn Arizpe et al., Young People Reading: Empirical Research across International Contexts (London: Routledge, 2018), 7.

-

[19]

McKechnie, “‘I Readed It!,’” 259.

-

[20]

This practice is partly a legacy of the “Literacy Hour,” which was introduced into the National Curriculum at the turn of the millennium. See Holly Anderson and Morag Styles, Teaching through Texts: Promoting Literacy through Popular and Literary Texts in the Primary Classroom (London: Routledge, 2000), 1–3.

-

[21]

Jacqueline McBurnie, “Re‑Culturing to Treasure Reading,” English 4‑11 66 (Summer 2019): 15–16.

-

[22]

Alice Sullivan and Matt Brown, “Reading for Pleasure and Progress in Vocabulary and Mathematics,” British Educational Research Journal 41, no. 6 (December 2015): 971–91, https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3180; Diana Smart et al., “Social Mediators of Relationships between Childhood Reading Difficulties, Behaviour Problems, and Secondary School Noncompletion,” Australian Journal of Psychology 71, no. 2 (June 2019): 171–82, https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12220.

-

[23]

Grenby, The Child Reader, 9.

-

[24]

Danielle Fuller and DeNel Rehberg Sedo, Reading beyond the Book: The Social Practices of Contemporary Literary Culture, Routledge Research in Cultural and Media Studies (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2013), 27–43.; Long, Book Clubs, 8.

-

[25]

Fuller and Rehberg Sedo, Reading beyond the Book; Danielle Fuller and DeNelRehberg Sedo, “‘Boring, Frustrating, Impossible’: Tracing the Negative Affects of Reading from Interviews to Story Circles,” Participations: Journal of Audience and Reception Studies 16, no. 1 (2019): 622–55; https://www.participations.org/16-01-29-fuller.pdf. Danielle Fuller, “‘It’s Not on My Map!’: A Journey Through Methods in the Company of Readers,” in Ueber Buecher Reden: Literaturrezeption in Lesegemeinschaften, ed. Doris Moser and Claudia Durr (Amsterdam: Vanenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2021), 217–30, https://www.vr-elibrary.de/doi/pdf/10.14220/9783737013239.

-

[26]

Fuller, “Listening to the Readers,” 15.

-

[27]

William McGinley and Katanna Conley, “Literary Retailing and the (Re)Making of Popular Reading,” Journal of Popular Culture 35 (2001): 219, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3840.2001.00207.x.

-

[28]

Lenters, “Multimodal Becoming,” 648.

-

[29]

Ibid., 645–46.

-

[30]

Mackey, Literacies across Media.

-

[31]

See: https://dorkdiaries.com/.

-

[32]

See: https://www.booktrust.org.uk/book/t/the-rose-muddle-mysteries-the-amber-pendant/.

-

[33]

David Kleeman, “Books and Reading Are Powerful with Kids, but Content Discovery Is Challenging,” Publishing Research Quarterly 32, no. 1 (March 2016): 38, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109‑015‑9442‑3.

-

[34]

Ibid., 42.

-

[35]

See, for example, the National Literacy Trust UK report on children and young people’s reading from 2020 which noted, “the issue of representation was particularly salient for children and young people who describe their gender not as a boy or girl, with 44.3% of these children and young people saying that they struggle to see themselves in what they read compared with 32.7% of boys and 32.5% of girls.” Christina Clark and Irene Picton, “Children and Young People’s Reading in 2020 before and during the COVID‑19 Lockdown” (London: National Literacy Trust, July 2020), 10, https://literacytrust.org.uk/research‑services/research‑reports/children‑and‑young‑peoples‑reading‑in‑2020‑before‑and‑during‑the‑covid‑19‑lockdown/.

-

[36]

Margaret Mackey, Space, Place, and Children’s Reading Development (London: Bloomsbury, 2022), 27, https://www.bloomsbury.com/ca/space‑place‑and‑childrens‑reading‑development‑9781350275959/.

-

[37]

Ibid., 214.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Holly, and Morag Styles. Teaching through Texts: Promoting Literacy through Popular and Literary Texts in the Primary Classroom. London: Routledge, 2000.

- Arizpe, Evelyn, Gabrielle Cliff Hodges, Lucia Cedeira Serantes, Osman Coban, Laura Guerrero Guadarrama, Nayla Aramouni, Erin Spring, et al. Young People Reading: Empirical Research across International Contexts. London: Routledge, 2018.

- Arizpe, Evelyn, and Morag Styles. Children Reading Picturebooks: Interpreting Visual Texts. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2016.

- Clark, Christina and Irene Picton. “Children and Young People’s Reading in 2020 before and during the COVID‑19 Lockdown.” London: National Literacy Trust, July 2020. https://literacytrust.org.uk/research-services/research-reports/children-and-young-peoples-reading-in-2020-before-and-during-the-covid-19-lockdown/.

- Deszcz‑Tryhubczak, Justyna. “Using Literary Criticism for Children’s Rights: Toward a Participatory Research Model of Children’s Literature Studies.” The Lion and the Unicorn 40, no. 2 (2016): 215–31. https://doi.org/10.1353/uni.2016.0012.

- Fuller, Danielle. “‘It’s Not on My Map!’: A Journey Through Methods in the Company of Readers.” In Ueber Buecher Reden: Literaturrezeption in Lesegemeinschaften, edited by Doris Moser and Claudia Durr, 217–30. Amsterdam: Vanenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2021. https://www.vr-elibrary.de/doi/pdf/10.14220/9783737013239.

- Fuller, Danielle. “Listening to the Readers of ‘Canada Reads.’” Canadian Literature 193 (Summer 2007): 11–34.

- Fuller, Danielle and DeNel Rehberg Sedo. “‘Boring, Frustrating, Impossible’: Tracing the Negative Affects of Reading from Interviews to Story Circles.” Participations: Journal of Audience and Reception Studies 16, no. 1 (2019): 622–55. https://www.participations.org/16-01-29-fuller.pdf.

- Fuller, Danielle and DeNel Rehberg Sedo. Reading beyond the Book: The Social Practices of Contemporary Literary Culture. Routledge Research in Cultural and Media Studies. New York: Taylor and Francis, 2013.

- Grenby, Matthew. The Child Reader, 1700‑1840. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Kleeman, David. “Books and Reading Are Powerful with Kids, but Content Discovery Is Challenging.” Publishing Research Quarterly 32, no. 1 (March 2016): 38–43. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12109-015-9442-3.

- Lenters, Kimberly. “Multimodal Becoming: Literacy in and Beyond the Classroom.” The Reading Teacher 71, no. 6 (May 2018): 643–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1701.

- Long, Elizabeth. Book Clubs: Women and the Uses of Reading in Everyday Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

- Mackey, Margaret. Literacies across Media: Playing the Text. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2007.

- Mackey, Margaret. Space, Place, and Children’s Reading Development. London: Bloomsbury, 2022. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/58882.

- McBurnie, Jacqueline. “Re‑Culturing to Treasure Reading.” English 4‑11 66 (Summer 2019): 15–16.

- McDowell, Kathleen. “Toward a History of Children as Readers, 1890‑1930.” Book History 12 (2009): 240–65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40930546.

- McGinley, William and Katanna Conley. “Literary Retailing and the (Re)Making of Popular Reading.” Journal of Popular Culture 35 (n.d.): 207–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3840.2001.00207.x.

- McKechnie, Lynne (E.F.). “‘I Readed It!’ (Marissa, Four Years). The Experience of Reading from the Perspective of Children Themselves: A Cautionary Tale.” In Plotting the Reading Experience: Theory, Practice, Politics, edited by Paulette M. Rothbauer, Kjell Ivar Skjerdingstad, Lynne (E.F.) McKechnie, and Knut Oterholm, 249–61. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2016.

- Reynolds, Kimberley, and M. O. Grenby. Children’s Literature Studies : A Research Handbook. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

- Ross, Catherine Sheldrick, Lynne McKechnie, and Paulette M. Rothbauer. Reading Still Matters: What the Research Reveals about Reading, Libraries, and Community. Libraries Unlimited, 2018.

- Smart, Diana, George J. Youssef, Ann Sanson, Margot Prior, John W. Toumbourou, and Craig A. Olsson. “Social Mediators of Relationships between Childhood Reading Difficulties, Behaviour Problems, and Secondary School Noncompletion.” Australian Journal of Psychology 71, no. 2 (June 2019): 171–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12220.

- Sullivan, Alice, and Matt Brown. “Reading for Pleasure and Progress in Vocabulary and Mathematics.” British Educational Research Journal 41, no. 6 (December 2015): 971–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3180.

- “UK Reading Experience Database ‑ Home.” Accessed January 14, 2022. http://www.open.ac.uk/Arts/reading/UK/.

List of figures

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6