Résumés

Abstract

In the spring of 1959 the City of Winnipeg ordered the removal of fourteen families, mostly Métis, from land needed for the construction of a new high school in south Winnipeg. For at least a decade, the presence of Rooster Town, as the squatters’ shantytown was known, had drawn complaints from residents of the new middle-class suburbs who objected to the proximity of families of mixed ancestry who seemed indolent, immoral, and irresponsible and whose children brought contagious diseases into the elementary school. Suburban anxieties gave expression to a much deeper municipal colonialism that since the incorporation of Winnipeg had denied Aboriginal people a place in the city. Various agencies of municipal governance and the processes of urban development dispossessed indigenous peoples and pushed them farther onto the edges of the city until no space remained for them. The removal of Rooster Town erased the last visible evidence of a continuing Métis community that had survived in the area since the nineteenth century and that at its peak in the 1930s had numbered several hundred residents.

Résumé

Au printemps 1959, la Ville de Winnipeg a ordonné l’éviction de quatorze familles, principalement Métis, pour libérer les terrains nécessaires à la construction d’une nouvelle école secondaire dans le sud de Winnipeg. Depuis au moins une décennie, ce quartier défavorisé, connu sous le nom de Rooster Town, a attiré des plaintes de la part des résidants de la nouvelle banlieue environnante en raison de la proximité de ces familles d’ascendance mixte qui donnait une image indolente, immorale et irresponsable et dont les enfants transmettaient à l’école primaire des maladies contagieuses. Les angoisses exprimées par les habitants des banlieues ont ainsi donné lieu à un colonialisme encore plus important que lorsque la constitution de la ville de Winnipeg avait donné lieu au refus de reconnaître aux autochtones une place dans la ville. Plusieurs instances municipales, de pair avec le développement urbain, ont évincé la population autochtone et l’ont repoussé vers la périphérie de la ville, jusqu’à ce qu’elle n’y trouve plus de place. Le démantèlement de Rooster Town a effacé les dernières témoins visibles de la continuité de la communauté Métis, qui y avait survécu depuis le dix-neuvième siècle et qui à son apogée dans les années 1930, comptait plusieurs centaines d’habitants.

Corps de l’article

In late December 1951 the Winnipeg Tribune asked its readers, “Heard of Rooster Town?” The answer: “It’s our lost suburb.”[1] The question was provoked by the school board’s investigation of complaints from parents sending their children to Rockwood Public School.[2] New housing development had made the school, built in 1940, the most overcrowded in the city, much to the concern of parents.[3] Middle-class suburbanites who had purchased homes in the developing tracts between Corydon and Grant Avenues west of Pembina Highway had complained that at school their children were exposed to contagious diseases carried by the poor children from nearby Rooster Town. Earlier in the month, fourteen children who had come to school with the skin disease impetigo were sent to the hospital for treatment. Contagious diseases had been an ongoing problem among Rooster Town’s children that fall and early winter. Since September, a public health nurse had visited one family twenty-one times, and in October city authorities sent twenty-three children to hospital for whooping cough and chicken pox.[4]

In presenting parental concerns, school trustee Nan Murphy described the homes in Rooster Town as “a picture of squalor and filth.”[5] The problem to her was that “the parents have no moral responsibility … They are shiftless and even when clothes and things are given to them they sell them.” Her solution would be “to condemn the area and move the families out.”[6] Her equation of poverty with laziness and moral irresponsibility sadly was also consistent with racial stereotypes about the Métis ancestry of most, though not all, of Rooster Town’s inhabitants. More sympathetic was Winnipeg Tribune reporter Bill MacPherson, who covered the story. He wrote that suburban parents warned their children, “‘Whatever you do …, don’t touch the Rooster Town children. You might get a skin disease.’ So the teacher calls for a group game and tells the children to join hands. Nobody would dare join hands with Rooster Town children.” MacPherson wondered, “Just what those little episodes can do to youthful personalities can be left to the imagination.”[7] Concerned as he was about the effect on the children, he had no remedy. Nor, as events unfolded over the next few years, was any alternative considered, and in 1959 the residents of Rooster Town were forced out to make way for the construction of a new high school.

Schools, which brought together students of different social backgrounds, became sites of anxiety and conflict, especially in the suburbs. Young families sought refuge from the older decaying areas of the city in new housing developments,[8] but for some, hopeful dreams contended with unsettling fears and unhappiness, as Veronica Strong-Boag has reminded us.[9] The spatial segregation of work and home rested on a gendered separation of family responsibilities that gave primary responsibility for the well-being of children to stay-at-home mothers. A suburban environment that could be isolating for married women also could harbour threats to their children. In the case of Rooster Town, suburban anxiety was reinforced by a deeply embedded sense that Aboriginal people did not belong in the city and by a history of municipal efforts, from the city’s incorporation, to remove their visible presence.[10]

Figure 1

Rooster Town, March 1959

Rapid suburbanization after two decades or more of housing shortages dramatically reconfigured the spatial distribution of poverty in Winnipeg’s modernizing urban landscape.[11] Cheap land on the urban fringes, which previously had been nearly worthless in market terms, appreciated in value as real estate companies assembled extensive tracts for housing development. Those who had been living there—that is, the poor, who could afford nothing else, and those whose racialized identities, Aboriginal people, made them unwelcome through much of the city—were displaced. Nor could they expect much help from a municipal government that preferred clearing slums to investing in public housing or dealing with the social problems associated with poverty and racism.[12] As upwardly mobile middle-income families left older areas of the city in pursuit of their suburban dreams, those they displaced on the outskirts moved into deteriorating inner-city neighbourhoods. By the 1950s the land occupied by Rooster Town was much too valuable to remain a refuge for the poor and unwanted (see figure 1).

Rooster Town in Context

Across Canada during the 1950s and 1960s, historians tell us, planners, architects, and politicians attempted to exercise a control, never achieved before, over the city. The fate of Rooster Town, though a small project in comparison with other episodes in Canadian urban renewal, and indeed on a smaller scale than other initiatives in Winnipeg, did present several of the contentious issues that other scholars have debated about suburbanization. But Rooster Town also offered a variant of what Jordan Stranger-Ross has termed “municipal colonialism”: that is, the city itself was a force colonizing Aboriginal peoples.[13] With suburban development, no place remained for shantytowns on the edges of cities, but the virulence of suburbanites’ reactions to the presence of Rooster Town’s Métis residents, and the non-Métis residents who lived like them, expressed a long-standing conviction that the city was no place for Aboriginal people.

Cities like Winnipeg have been on the “edge of empire” well into the twenty-first century as the gateways to new spaces to be incorporated into capitalist production and metaphorically as cultural spaces where waves of outsiders have been subjected to programs of liberal bourgeois assimilation.[14] Relentless as the processes of colonization have been, they have been uneven, ongoing, and iterative, as boundaries shifted, as new groups have come under surveillance, and as the colonized resisted.

As Jane M. Jacobs has argued,[15] the relations of power and difference that are imperialism have been and continue to be articulated and enforced in and through the organization of space and the meanings assigned to space. Within cities that have engaged in imperialist enterprises, the space needed for living and working has been allocated—won or lost—through the contention of differing claims from settlers and the colonized to “home.” The expropriation of autochthonous groups from their soil has been not just an exertion of physical force, it also has been a cultural process whereby colonizers have distinguished their self from the colonized and racialized other and have claimed their own greater beneficial, scientific, and moral use of space otherwise wasted, despoiled, and defiled by prior inhabitants.

Colonialism has been more complex in practice than might be assumed from the construction of the binary identities that have been at its core. In studying British Columbia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Renisa Mawani has pointed out that colonial spaces created proximities within which a variety of different groups came into contact and interacted with one another. “These colonial proximities disturbed the self/other divide, creating opportunities for affinities, friendships, and intimacies that jeopardized the quest for interracial purity.” The multiple cultural and racial hybridities created through interaction disturbed the order of things with which the colonizers felt comfortable, produced anxieties, and provoked colonizers to refine their differentiations of groups through new interracial taxonomies. Mawani has argued that anxious colonizers implemented “state racism,” the juridical application of their new knowledge of human categories, to regulate the unclean, immoral, and even degenerate bodies that threatened their safety and the safety of their children.[16] Of particular relevance for this study has been Mawani’s investigation of those she has termed “half-breeds,” to apply the category of the time. In British Columbia, from the late nineteenth century, racial knowledge conceived of people of mixed ancestry as morally and physiologically weak, and their drunkenness, licentious sexuality, and proclivity for crime made them a danger to both Europeans and Aboriginals.[17] Being “half-breed,” in-between and not quite white or “Indian,” also rendered it possible to deny their Aboriginal connection to the land and so to consider them propertyless and squatters on land that was judged not their own. On these grounds, for example, the courts decided in the 1920s in authorizing the expulsion of mixed families from Stanley Park in Vancouver.[18]

Jean Barman, herself the author of a study of Stanley Park, has reminded us that the creation of the park was only one struggle in the ongoing colonialist campaign to absorb a number of reserves across British Columbia and to erase “indigenous Indigeneity.” A rather awkward term, it nonetheless distinguishes the identities lived by Aboriginal people themselves from the replacement, “sanitized Indigeneity” created by white British Columbians to conceal the unsettling of Aboriginal people under an illusion of friendly relations.[19] The postures of friendly relations, according to Victoria Freeman, became critical tropes in the articulation of Toronto’s history at its half-century commemoration in 1884. In the celebratory procession of that year, the association of First Nations people with a past before history, along with their presumed deferential and subservient acceptance of British rule, imagined a progressive and amicable character for the colonialism achieved in the founding of Toronto.[20]

As Toronto’s celebration demonstrated, cities were not just “mechanisms within the colonial project,” but were, in Jordan Stanger-Ross’s words, “sites where colonialism was expressed and experienced.”[21] As he and Penelope Edmonds have contended, urban institutions and practices could be inherently colonial and constituted a “municipal colonialism” that was not just in the city, but of the city. In examining Victoria, British Columbia, in the late nineteenth century, Edmonds has argued that the creation of property in the city, and its individualized possession justified by claims of its creative use, impelled settlers to engross ever more space at the expense of nearby reserves. They imposed their understandings of order upon that space and strove to eliminate the bedlam that had been Indigenous occupation. By-laws, regulations, and services defined proper uses of space, while also sanctioning undesirable urban types—“vagrants,” “nuisances,” and “prostitutes”—most commonly applied to Aboriginals who did not have a place in the settler city of enterprise, wage labour, and home-making.[22]

Making Aboriginal people disappear from the city, Stanger-Ross has maintained, required the “ongoing affirmation” of the “incongruity between urban and Aboriginal,” that they did not belong. The location of reserves within Vancouver continued to be an affront, yet an opportunity to civic authorities. Stanger-Ross has convincingly shown that as times changed, so did the tools available to municipal colonialism for the removal of First Nations. From the 1920s into the 1940s the urban planning movement, with its conception of the city as an organism and its claims for the recuperative effects of city beautification, employed the most modern of scientific analyses and means to condemn Aboriginal land uses. If properly “cleaned up,” reserve land, wasted for decades, promised to restore “nature” to urban life. The irony of reclaiming nature from people earlier considered too much a part of nature to fit into civilized society escaped those planners and civic authorities beset with “deep misgivings about progress” and anxious about the health of urban living.[23] Their anxieties, expressed in different ways, had been a constant from the establishment of the city, however.

Following Stanger-Ross, municipal colonialism must be seen as a constant through Canadian urban experience. His work helps to correct the misconception that, as Evelyn J. Peters has stated, “City Indians” have seemed to be relatively recent urban-dwellers, arriving in the 1950s.[24] Nor have historians, with the exception of those studying Halifax’s Africville, considered the possible associations of race with suburban development.

Richard Harris has argued that suburbanization, especially after the Second World War but in planned suburbs even earlier, suppressed the diversity of neighbourhoods on the edges of Canadian cities. The desire to maintain property values and to imprint an aesthetic of orderly space disciplined developers and then homeowners, so that from place to place home-buying was limited to more specific and relatively narrower income strata.[25] But even then, distance from the centre of the city constrained the ability of developers to limit diversity through planning. In Winnipeg, for example, Crescentwood, promoted from 1902, was just across the Assiniboine River from the central district and was not far from older elite neighbourhoods. Its developer, as Randy Rostecki has argued, could enforce restrictive covenants stipulating the value of houses to be constructed on the lots sold.[26] On the other hand, the elite suburb of Tuxedo Park, which came on the market not long after Crescentwood, lay too far west of Winnipeg’s suburban edge to attract the upper-middle-class buyers who were its targeted market and, as James Pask has explained, “for many years, Tuxedo’s population was made up of working class people and farmers.”[27] Elsewhere in Winnipeg—Elmwood, for example, as Harris noted—suburban industrialization attracted working-class families to areas where planning went little further than the registration of a survey and the advertising of lots for sale. Such unplanned suburbs were the most common type in Winnipeg, as they were throughout Canada, according to Harris.[28] By the post–Second War period, planned housing tracts caught up with the unplanned suburb and, where building had stalled in unplanned suburbs like Winnipeg’s south Fort Rouge, urban renewal and redevelopment attempted to erase disorderly blots of self-built housing, as in Rooster Town.

Historians have argued that proponents of urban redevelopment, downtown or on the fringes, too often equated the quality of housing with the character of residents. Kevin Brushett has noted that “Toronto’s modern assault on the slums” was also an assault on low-income residents who were treated dismissively by property owners, developers, and politicians.[29] Similarly Sean Purdy has explained how media presentations promoting Toronto’s Regent Park Housing Project in the 1950s and 1960s stigmatized the inner city as an “outcast space,” and the people who lived there “were portrayed as dirty, disreputable and prone to various pathologies.” Once their image had been imprinted on the public mind, it was difficult to erase.[30]

Jill Wade has reminded us that the marginal housing that so upset planners and politicians after the Second World War included not downtown neighbourhoods, but also shacks in “jungles” along railroad tracks and on the city’s edge, on the “foreshore” in the case of Vancouver.[31] Even before the Second War, self-built housing on the urban edge contradicted more refined notions of the proper use of space. In their study of Hamilton’s “boathouse community” along Burlington Bay, Nancy B. Bouchier and Ken Cruikshank have pointed out that the stigmatization of squatters facilitated their removal in the late 1930s to make way for parkland and nature preservation.[32] Indeed, as Harris noted, a fringe area, the Kingston shacktown of Rideau Heights, was targeted as Canada’s first government-sponsored urban renewal project, a consequence of the outward expansion of suburban housing and commercial development.[33]

The problem of which came first—the stigmatization of neighbourhoods and residents or the impulse to redevelop—has been debated by scholars interested in Canada’s most infamous renewal project, Africville in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Jennifer J. Jackson has recently maintained that discourses about African-Canadian family pathologies, their criminal proclivities, and general deviancy had racialized and “fundamentally, discursively, and materially defeated [the community] from the outset,” long before the late 1950s and the 1960s when urban reformers sought to remove an area perceived as blight and to remedy a “culture of poverty.”[34] Nelson’s interpretation rejected the earlier arguments of Donald H. Clairmont and Dennis W. Magill, whose research, beginning shortly after the completion of the relocation, attributed injustice to a complex of factors: the liberal-bureaucratic and social activist emphasis on relocation as a necessary step to integration and improved race relations was naive in failing to appreciate class, power, and racism as obstacles to progress. Moreover, as Clairmont subsequently responded to Nelson, the residents of Africville accounted for only 10 per cent of the population displaced by redevelopment in Halifax, making racial stigmatization alone an incomplete explanation.[35]

Tina Loo most recently has taken Clairmont’s reminder about the larger context of re-development, but has asked what significance this had for Africville’s residents. Halifax officials, she contended, considered Africville as a welfare problem for the liberal state to solve, rather than a racial problem: “Racism might have been the reason Africvillers were disadvantaged …, but solutions liberals offered were aimed at meeting Africvillers’ needs—education, employment, adequate housing, and access to capital—rather than eliminating racial prejudice directly.” Attentive to these public needs of the individual, officials, social workers, and planners neglected private needs, in particular the individual’s need for community belonging, for “friends and fellowship—the things that made home.”[36]

Africville with its approximately four hundred residents was larger than many of the racialized “Indian” and “Métis” communities that attracted government attention in Manitoba around the same time. In 1956 the Manitoba government hired Jean H. Lagassé to study the province’s Aboriginal population. His report three years later identified twenty-six “fringe settlements,” including Rooster Town, inhabited by people of “Indian ancestry.” Unable to obtain services or opportunities in rural areas, many Métis had moved to the urban edges, where they squatted on unserviced land and took what work they could find it. Poor living conditions and the absence of any social pressure to promote ambition or acceptable moral behaviour created a “slum mentality,” Lagassé observed. In words not unlike those of Rooster Town’s critics, he contended that slum-dwellers believed that “efforts for betterment of self and family are not likely to succeed” and that happiness should be found in “easily attainable goals.” Slum practices, circumstances, and lifestyles provoked racial prejudice in the minds of the public who derived “their concept of what a Metis home looks like from fringe settlements.” Given that racism, Lagassé found some benefits to such settlements: they did provide some shelter from racism as places midway between Aboriginal and white cultures, where residents might progressively learn the skills needed for integration.[37]

For Lagassé the solution was in community development. Born in Gravelbourg, Saskatchewan, he had moved to St. Boniface, Manitoba, where he completed his undergraduate education. The recipient of a master of arts degree from Columbia University in 1956, he had been head of the Winnipeg office of the Citizenship Branch of the Department of Citizenship and Immigration from 1952 to 1956. After the completion of the report, the Manitoba government appointed him director of Indian and Métis services and then director of community development services. About 1963 he returned to the Citizenship Branch as chief of the liaison branch. By 1965 he was the director of the branch and was credited as being “the founder of the community development philosophy in Canada.”[38] In his provincial and federal careers, and through his work with ethnic groups and Aboriginal people, Lagassé was deeply involved in the citizenship project that equated Aboriginal people with immigrants as targets for assimilation through a unifying citizenship based on middle-class gender and family standards and capitalist values. As Heidi Bohaker and Franca Iacovetta have argued, treating Aboriginal people as immigrants denied their history and the special responsibilities that the Canadian state has had for them.[39]

In an appendix to the Lagassé report, anthropologists W. E. Boek and J. K. Boek elaborated on the ways that slum behaviours, necessary for survival, compromised the ability to integrate into white urban society.[40] Aboriginal slum-dwellers frequently depended on friends and relatives for gifts, food, loans, shelter, and help in finding work. Assistance willingly given was expected to be reciprocated, since situations could be quickly reversed and a benefactor might easily become the aid-seeker. This co-operative support system, Boek and Boek concluded, reduced the chances that Aboriginal people would succeed in white urban society. Those who were getting ahead and had some savings soon found their surplus dispersed among the larger group of those not doing so well: “To retain one’s resources, it would be necessary to reject former friends and kin while taking on the urban values of a capitalistic society. In the face of prejudice, this is a difficult transference because if the gamble of not being accepted in a dominant society is lost, there is not much to fall back on.”[41] Generosity might compromise longer-term survival.

The awareness of Rooster Town as a fringe settlement was part of a larger and growing concern in the postwar era about slums, urban renewal, and suburbanization. But the fears that it provoked among suburbanites were also consistent with much older convictions that Aboriginal people were unsuited to, and undesirable in, urban settings.

Locating Rooster Town

According to reporter John Dafoe in 1959, Rooster Town “began life as an Indian settlement on the southern fringes of Winnipeg. How long ago no one is sure—30 years anyway.”[42] Discovering just “how long ago” is a genealogical problem of sorts, tracing the antecedents of the neighbourhood and the people who lived in it.

In the 1950s, when suburban complaints about it were particularly vehement, Rooster Town occupied a fringe of the south Fort Rouge area of Winnipeg between the Canadian National Railway’s mainline on the south and its Harte subdivision line on the north and roughly bounded on the east and west by Wilton and Cambridge Avenues respectively (see map 1). Earlier self-built housing had been widely distributed on or beyond the fringes in south Winnipeg. Intermittently in the 1920s and 1930s, and steadily in the 1940s and 1950s, contract and speculative builders built more and more houses in the area, and property values appreciated. Those who owned the land on which their self-built houses stood were absorbed into more densely developed neighbourhoods. But many Métis were squatters, and they moved their shacks farther out, and farther out again, as new building encroached (map 2).

Rooster Town first received municipal attention in the latter years of the Second World War as the city struggled to deal with Winnipeg’s deteriorating housing stock and the shortage of decent shelter. Early in 1944 the city’s health officer informed council that the proliferation of outhouses, especially in Fort Rouge, presented a “serious menace to the health and welfare of the city.” Alderman William Scraba asked, “Is it in Rooster Town?” Not exclusively, he was informed; many of the properties that the city had acquired for non-payment of taxes, and that were being sold, did not have sewer connections.[43] Journalists outside Winnipeg picked up on the issue. Not long after, an article in the 22 April 1944 issue of Flash, a Toronto magazine, proved especially offensive to civic pride. The article contended, “Winnipeg can lay claim to the dubious distinction of the being the most backward city in Canada in regard to housing and sanitary conditions.” Exemplifying Winnipeg’s worst was Rooster Town. Alderman Scraba, among others on City Council, took umbrage at the slur, but, revealing his limited familiarity, he admitted, “If it’s as bad as it says, we should do something about it!”[44] The city did nothing for Rooster Town.

Map 1

Population density of Winnipeg, 1946 (with Rooster Town area circled)

Scraba’s question presumed an earlier awareness of the area. In his autobiography, Stephen Casey, who grew up in south Winnipeg in the 1920s and 1930s, located the Rooster Town of his youth about one kilometre north of its 1950s location. He remembered that then there were “many Métis” in St. Ignatius Catholic School. They lived in Rooster Town, which was past the corner of Corydon Avenue and Wilton Street “on what was then open prairies, rough grass punctuated by a few willows and scrub oaks” and also in “Turkey Town a little farther east. These Métis spoke French … They were desperately poor in those days and most lived in tar paper shacks.”[45] With time and the pressure of residential development, Rooster Town residents gradually moved south, a few more each year, and Turkey Town inhabitants relocated farther west, so that the two communities merged under the name of the former. Free Press reporter John Dafoe explained, “As the city moved south, the rooster towners loaded up their scrapwood shacks and moved on, farther onto the prairie.” According to a city official, at its peak in the 1930s Rooster Town was home to several hundred residents.[46]

Before the 1930s and before it was named Rooster Town, a Métis community existed in Winnipeg south of the Assiniboine River, in Fort Rouge. Known at the beginning of the twentieth century as “the French settlement,” it was home to Métis people who had lived there prior to 1870 and more who had moved into the area thereafter from rural areas.[47] Not all Manitoba Métis had been dispersed from the Red River Valley in the 1880s, even if many had been dislocated from their lands by government failure to honour its commitments, as Douglas Sprague and Philippe Mailhot have argued, or by economic factors, as Gerhard Ens has countered.[48] By the 1890s agricultural land in the parishes to the west and south of Winnipeg was too expensive and insufficient to provide farms for the children of those Métis families who had remained in Manitoba after the transfer of the west to the Dominion of Canada. A redundant rural population drifted to the cities or moved farther west.

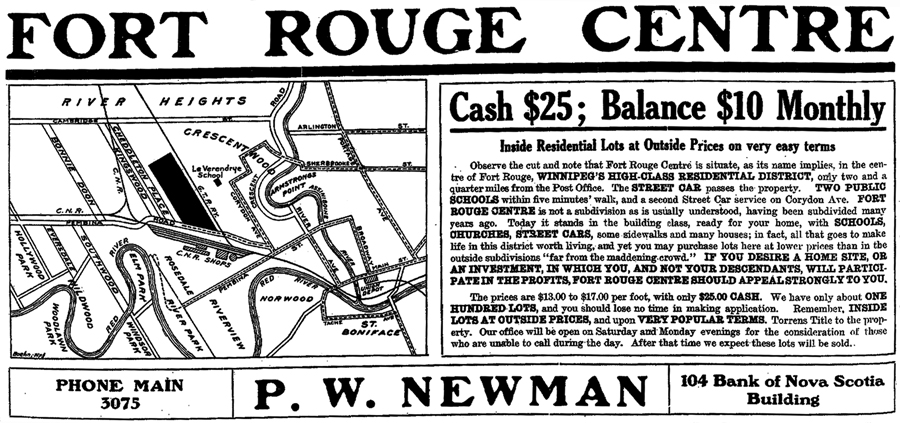

Arriving in south Winnipeg from the 1890s and into the 1930s and 1940s, they found extensive tracts of land left vacant from failed real estate promotions. Before the First World War, south Fort Rouge had excited real estate speculation, since the new Canadian Northern Railway’s shops and yards were adjacent to the east. As the promoters of Fort Rouge Centre—which was more peripheral than central—proclaimed, “Lots in this new subdivision are selling cheaper than adjoining properties. Owing to the proposed C.N.R. shops in Fort Rouge, these lots are now in great demand”[49] (see figure 2). Or not, as it turned out. The recession of 1913, the Great War, lingering postwar recession, and then the Great Depression of the 1930s ended speculative interest and prospects for significant industrial or residential development in south Fort Rouge.[50] Even at greatly reduced prices, demand was limited, and in the 1920s and 1930s the city seized vast tracts of land in the area for tax arrears. From time to time the city sold a few lots, but not until the post–Second War period was the city able to unload its substantial land holdings to corporate developers.[51] Since little development resulted until the 1940s and 1950s, especially on the southern and western margins, squatting remained uncontested for at least fifty years.

Map 2

Location of Rooster Town, ca. 1900 to 1960

Note: The ovals do not exactly define Rooster Town. Rather, they identify an area within which Métis families resided at different periods and show the movement south and concentration of residences over time. Not all Métis families in Fort Rouge were located within these boundaries, and other ethnic groups lived in these areas.

Figure 2

Advertisement for lots in Fort Rouge Centre, 1911

Being Métis in Winnipeg

Through its history Winnipeg has seldom been hospitable to Aboriginal people, either those whose presence predated the city’s incorporation in 1874 or those attracted afterwards by its opportunities. Being Métis in the city through much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries meant being subject to racism and even violence. Wealth and status bought invisibility or acceptance as a French and Catholic hybrid. If one was poor and visible, retreating to marginal spaces and being inconspicuous brought some peace and safety. Regardless of class, family provided shelter, security, and identity. For many Métis, identity has not been simply a matter of mixed ancestry, but instead it is genealogical and involves descent, relations, and connections to place and community. History has been expressed in personal and family terms, and family histories have been means to discover historical communities whose existences have been denied, oppressed, and erased.

The incorporation of the City of Winnipeg in 1874 initiated municipal colonialism that gave institutional expression to the ambitions of settler-colonizers who had supported the acquisition of the North West by the Dominion of Canada and had violently opposed the indigenous Métis who had tried to negotiate their place in the new order.[52] The presence of Métis was a serious affront to the settler sense of order because, unlike First Nations, they had made Winnipeg and the area around it their permanent home. During the “Reign of Terror” that had followed the arrival of the Red River Expeditionary Force until the provincial government’s approval of the Winnipeg Charter, Canadian militiamen had beaten and murdered Métis men and harassed and sexually assaulted Aboriginal women.[53] First Nations people were no more welcome. While they never settled permanently there, the Saulteaux and Cree Nations of southern Manitoba area regularly visited the forks of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers.[54] Their seasonal encampments, religious ceremonies, and trading in and around Winnipeg in the 1860s and 1870s were sufficiently common for settlers to consider “the Fort Garry Band,” numbering about five hundred in 1871, a nuisance and, until they signed Treaty One, a potential danger.[55]

After incorporation, the regulation of Aboriginal people was pursued through the exercise of civic powers, principally the police, but also health authorities. Not only had Aboriginal space been appropriated, but settler colonialists also judged Aboriginal people inappropriate in the city and constructed their bodies culturally to represent dangers to be controlled and eliminated. Into the 1880s, as Megan Kozminski discovered, the nationality most often recorded for those arrested was “half breed,” a not surprising result, since the police regularly patrolled those areas of the city inhabited by Aboriginal people, on the lookout for men who were “vagrants,” women who were “prostitutes,” and “drunks” who were both.[56]

A frequent target, as Christine Macfarlane has reported, was Marie Trottier, a Métis woman described in the press as a drunken vagrant and “half breed prostitute.” Regularly in and out of court and jail for various charges from the mid-1870s to the mid-1880s, Trottier was brought into court in May 1881 on a hospital stretcher to give testimony in an abortion case against a local doctor, J. Wilford Good. Police alleged that one month earlier Trottier, just out of prison and seven months pregnant and pressured by her lover, had purchased an abortifacient from Good. After miscarrying, Trottier suffered serious haemorrhaging and sought medical attention from her regular doctor, who refused to treat her. A friend informed the police. In court, seven doctors, other than Good, testified to Trottier’s immoral character, and the judge concluded that there had been no abortion. She was reprimanded and ordered to leave the city within forty-eight hours or face time in jail.[57]

Trottier, who had been living in a shack on “the flats” below the forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, moved to a Métis settlement just outside the western limits of the city. The following year she again ran afoul of local authorities. Having contracted varioloid, a modified and mild form of smallpox, during a local outbreak of the disease, she was quarantined under the authority of the city medical officer in the smallpox hospital. During her confinement, she was paid to attend to the sick and dying internees and was described by the undertaker as “the only real Christian” among the staff. Conditions in the hospital were appalling (and provoked a subsequent inquiry), and Trottier escaped three or four times. Brought back the last time, she was shackled to a twenty-five-pound ball-and-chain to prevent her from again seeking freedom and possibly spreading the disease. Quarantine, even forced, might have been a necessary response to the contagion—local authorities certainly thought so. But Marie Trottier’s escape attempts are also understandable, given her previous experience with medical authorities, her confinement with patients sicker than she was, and the lack of appreciation of her services by authorities. To them her body, made potentially lethal by her immorality and cohabitation with others of her sort who might also spread the disease, was a danger they had to control, even to the point of using chains.[58]

As Sylvia Van Kirk demonstrated, just prior to Winnipeg’s establishment, among families who were better off, the efforts to control the bodies of children of mixed European and Aboriginal ancestry took the form of proper education, an acceptance of the prevailing standards of cultural refinement, and a rigorous concern for propriety.[59] The identities of the most successful Métis families were probably less fragile than Van Kirk and Frits Pannekoek have argued, since, as Brian Gallagher has shown, the marriage prospects and social prominence of several generations of people from mixed families, even after 1870, did not appear to suffer from the growing racism, although depending upon their resources families on occasion must have had to choose which child to favour.[60] At the very least, they were able, as David T. McNab has described it, “to hide in plain sight” and not to draw attention to their heritage.[61]

At the same, when they did come out to engage in identity organizations, the social status of some gave respectability to their activities that sanitized their indigeneity. The officers of the francophone organization Union nationale métisse Saint-Joseph du Manitoba (founded in 1887) impressed the Manitoba Free Press in 1923: “There is … a vast difference between the rude, almost Indian-like Métis of days gone by and that of the honorary president … Roger Goulet, inspector of public schools for the province, or that of Samuel A. Nault, estate manager of the Winnipeg Trustees Company,” who was president.[62] The separation of the respectable Métis from their Aboriginal heritage, at least in the perception of English and French Canadians, was further promoted by the assimilation of Métis claims within the larger campaign for French rights.[63] At the unveiling of a plaque at the St. Boniface Cathedral commemorating Louis Riel in 1944, historians Lionel Groulx and A. R. M. Lower agreed that the Métis leader had been right to defend French national rights. No mention was made of the rights of Métis as an indigenous people or the protection of economic futures of their children.[64]

On the other hand, those of mixed ancestry lacking class respectability were perceived more critically. In language that now startles, given its wartime context, the Winnipeg Free Press in 1941 described the Métis as having “the instincts of the Indian thinly coated over by certain sophistications of the Aryan. He is difficult of assimilation into white culture. He stagnates in hovels on the fringes of little urban centres.”[65] It is hardly surprising that Lagassé found that fewer than 1 per cent of the people interviewed for his 1958 study admitted to being Métis, even though he estimated that between one-eighth and one-quarter of all Manitobans had some degree of Aboriginal ancestry. In fact, he opined, “It is no longer possible to identify, as Métis or Half-Breed, all those who are of mixed White and Indian background, for this presupposes a knowledge of individual genealogies.” To consider them in his study, he relied upon the judgements of “White informants” who maintained that “there exists a certain way of life in Manitoba, which in addition to physical characteristics, identifies one as a Métis or Half-Breed.”[66]

Family histories document not just the indigenous origins of people whose presence settler-colonizers wanted to deny or erase, but also the survival of a community, supported by kinship ties across several generations. For these reasons genealogy has been the central and necessary tool in reclaiming Métis identity and securing rights. Knowledge of individual genealogies is possible for many inhabitants of Rooster Town.[67]

Reconstructing the life histories of members of an underclass remains fraught with uncertainties and at times intuitive leaps. Even the poorest, however, from time to time fell under surveillance and left traces in routinely generated records, including city directories, newspaper obituaries, and crime reports, and in earlier years census and land claim records. Working backwards, some Rooster Town residents could be found in city directories. Their listings were irregular and incomplete, and street numbers might differ from year to year, as canvassers often had to guess at the approximate address on what were little more than trails through the bush.[68] With names and addresses, searches of the Winnipeg Free Press and its predecessor, the Manitoba Free Press, found obituaries and other articles, including a considerable number of police reports.[69] Less numerous were the unrestricted vital statistics certificates for births, marriages, and deaths in the Province of Manitoba.[70] The manuscript schedules for the Canadian censuses of 1881, 1891, 1901, 1906, 1911, 1916, and 1921 revealed unexpected connections between Rooster Town and Métis residents in south Winnipeg and nearby parishes in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[71] Useful in determining family relationships were the Métis Scrip Records.[72] The result has been to connect with reasonable certainty the antecedents and kin relations of several families who lived in Rooster Town.

Tracing the movements and experiences of three extended Métis families—the Bérard family, the Smith/Dunnick/Parisien/Laramee families, and Henry/Hogue/Logan families—reveals the range of experiences associated with being Métis in Winnipeg from the late nineteenth into the mid-twentieth century.

Among the more successful of the Fort Rouge Métis were the Bérards, several of whom occupied river lots before 1870 and stayed in Winnipeg after leaving the land. François Bérard was born in the Red River Settlement about 1838 of a father from Quebec and a Métis mother. François occupied a river lot on the Assiniboine River in St. James Parish in 1871, near to his younger brother, Daniel. An elder brother, Jean-Baptiste, farmed land fronting on the Red River. Near him was another brother, Pierre, who in the 1880s was the proprietor of the Fort Rouge Hotel. No longer on his land in 1881, François worked as a labourer and lived with his wife Marguerite and eight of their children south of the Assiniboine River. Ten years later he and his family had moved into the city and resided in a rented house on Notre Dame Avenue, east of Main Street. Besides working as a house carpenter, he earned extra income as a porter at the American Hotel on Main Street. Living on the same street in 1901, though in a different house, Bérard at age sixty-three years had slowed down at his carpenter’s trade and earned only $300 for eight months at work; his wife earned as much from taking in laundry. His sons Florent and Frederick, employed respectively as a labourer and a teamster, added another $850 to the family income, which gave the Bérards a comfortable amount to live upon for a time. But as they aged and could no longer work, François and Marguerite depended more upon their children, who were embarking on their own adult lives.

By 1911 François and Marguerite Bérard had moved to Westview Avenue in the Kingswood subdivision on Winnipeg’s southern edge—not far from where François’s brothers had lived earlier. Son Fred and daughter Nellie were still at home and supporting their parents, while Florent, now a fireman on the Canadian Northern Railway, lived with his wife Marie Louise and family nearby at 907 Carlaw (renamed Carter) Avenue. Not far away, at the corner of Scotland Avenue and Wilton Street, lived another branch of the family, two sons of François’s nephew.[73] Members of the Bérard family continued living in Fort Rouge into the 1930s, but not in Rooster Town. As well, they took pride in the French-Canadian side of their heritage. For example, in 1937 eleven-year-old Dulcie Bérard belonged to La Lignée Lagimodiere, a family association dedicated to tracing the heirs of Jean-Baptiste Lagimodiere and his wife Marie-Anne Gaboury, the first French-Canadian married couple to settle in western Canada. Later in life, Florent and Marie Louise Bérard moved across the river to St. Boniface to live in that francophone community.[74]

Unlike many Métis, the Bérards did not move farther west after they left the land. Instead François and his sons found wage labour and for much of the time were able to live in the same area of Winnipeg. Established members of “the French settlement” before the First World War, they were well enough off not to need refuge in Rooster Town as that community grew in the 1930s, but instead they identified more with franco-manitobains.

The interrelated Smith, Dunnick, Parisien, and Laramee families were among the earliest in-migrants to “the French settlement,” and several remained in and around Rooster Town into the post–Second War era. Her 1932 obituary described Kathrine (or Catherine) Parisien as “a pioneer of the west.”[75] Born in St. Norbert Parish, south of Winnipeg, in 1857 to Métis parents, Pascal Parisien and Catherine Courchene, Catherine moved to a farm in St. James Parish after her marriage to William H. Smith, an English Métis. Smith had received scrip, but he farmed land owned by his father, John. The farm was part of the area annexed by the City of Winnipeg in 1882. Into the 1890s the eight-member Smith household lived in a one-storey, two-room house on the western edge of the city. By 1901 they had moved to a one-storey, six-room wooden house on Cambridge Avenue near Fleet Street, on the southern edge of the city. William reported to the census enumerator that year that he had worked for seven months as a labourer and earned $300. But he probably gardened a bit, since the assessment roll for 1902 lists his occupation as farmer. By 1906 Catherine Smith was on her own, still on Cambridge, but now with her five children, daughter-in-law, and two grandchildren. Shortly thereafter she married Harry Parisien, who moved in with her. In 1911 the couple shared the house with her son, William Jr., and his wife, Marie. Son Alex, his wife Agnes, and their six children lived next door on one side, while on the other side lived daughter Mary Jane and her husband William Dunnick, who was not Métis. Dunnick and his brother-in-law Alex Smith worked together as teamsters, while Harry Parisien and William Smith laboured at odd jobs. Five years later Louis Parisien, who probably was a relative, joined them on the street.[76]

By the early 1920s, as real estate development approached their original location, the Smith, Parisien, and Dunnick families had moved about two kilometres farther west, to the wooded area at southern ends of Ash, Oak, and Waterloo Streets, close to the Canadian National tracks.[77] Over the next few years seven or eight families, Métis and others, built houses nearby. Dunnick did well enough in his hauling business to operate a truck in the 1930s and to hire additional labour, several of whom lived close by. His son, William Jr., married Agnes Lepine, the daughter of Ernest Lepine, a labourer, and Marie Julia Lepine, who had moved to 916 Ash from St. Norbert.[78] In the late 1930s the Dunnicks moved back to the area on Cambridge Street, where they had resided earlier. Sometime after her husband’s death in 1939, Mary Jane Dunnick married Phileas Laramee and moved to 937 Lorette Avenue. There she was close to her son, William Jr., at 819 Ebby Avenue, while her brother, William Smith, lived nearby on the corner of Lorette and Wilton Street.[79]

In the 1920s and 1930s the Laramee brothers had been neighbours of the Dunnicks—Phileas had boarded with them—and probably from time to time they worked for Dunnick. Paul, Phileas, and Joseph Laramee had moved with their parents from Yamaska, Quebec, to St. Norbert Parish in 1876. The Laramee boys were farm labourers before coming to the city after the First World War.[80] Paul, his wife Marie Julie (who was Métis), and their children lived at 916 Ash Street in 1935, very near William Dunnick, for whom he worked. Their daughter, Josephine, married Adolphe Pilon, a labourer, and in 1935 lived at 916 Ash Street. Sometime in the 1950s—several years after his wife died in 1943—Paul moved in with his son Joseph and family at 1023 Weatherdon Avenue. Joseph Laramee, who worked for the city, owned the house, as did his brother Archie, a landscaper, who lived across the street at 1022 Weatherdon, and his other brother Basil, a plumber, who lived just up the street at 996 Weatherdon. Owning property placed them outside, but near, Rooster Town and, as with the Smith/Dunnick family, coming to the city brought some success.

The family connections of the Smiths, Parisiens, Dunnicks, and Laramees were complicated and confusing to follow, but their interrelationships of marriage, work, and residential location created a web of interdependence and support that provided the basis for community. As one or the other moved, friends and family followed and, as they became established, they were joined by kin who came from farther away. The extent of their connections demonstrated the generalizations of Boek and Boek about Aboriginal survival strategies: even though some possessed steady work, they were reluctant to give up the security of their kin and friends.

The Henry, Hogue, and Logan families also developed an extensive kin network, but never achieved comparable security. Some time before 1901, John Baptiste and Mélanie Henry moved from St. Norbert to the western edge of the bush in Fort Rouge, not far from the Smiths. In 1891 John Henry had worked as a farm labourer. Neither his nor his wife’s father had any claim to a river lot acknowledged after 1870. Even if they had secured land, their families were too large to provide all sons with viable farms. John did apply for Métis scrip in 1875, but his form does not indicate that it was granted. In 1901 the ten-member Henry family lived in a two-room shack, assessed by the city at just $50. Unoccupied land made it possible for the Henrys to pasture two cows and two horses. John hired himself and his team out, but earned little, just $120 in 1901, suggesting that he found steady employment difficult to secure. Nonetheless, he reported to the census enumerator in 1901 that he owned his house, a stable, and three lots, although the 1902 city assessment role recorded no land ownership for him.[81] After John’s death, Mélanie (or Minnie) married Fidime Gagnon, a self-employed teamster who had been born in Quebec and had lived in St. Vital earlier. With children from both of their former marriages, they squatted in a four-room house on Fleet Avenue in 1916 and 1921.[82]

Of the twelve children of John and Mélanie Henry, four daughters lived in “the French settlement” and then Rooster Town nearly all their adult lives. Early in the century Mathilda moved away after marrying Patrick Conway, who was Métis, but they had returned by 1916 and lived first at 1019 Dudley Avenue and in 1921 farther west near the corner of Dudley Avenue and Rockwood Street. Living in a two-room wooden shack stretched the very modest income of $700 that he earned as a labourer in 1921. After her husband’s death, Mathilda continued to live on Dudley Avenue until at least 1940.[83]

Her elder sister, Mary Cora, and her husband, Joseph Arcand, had lived nearby on Fleet Avenue in the 1920s but then moved next door to Mathilda in the 1930s.[84] Another sister, Marie Josephine, lived at 1147 Weatherdon Avenue in the 1930s. She had married Joseph Edward Parisien, a widower thirty-six years her elder, in 1923. Parisien, a labourer, had lived in St. Norbert prior to moving to south Fort Rouge about 1914 and lived with his first wife in a two-room shack at Lorette Avenue and Rockwood Street in 1921.[85]

A fourth daughter of the Henrys, Marie Julienne, was, with her sister Mathilda, among the last residents of Rooster Town. Julia was born in St. Norbert Parish, south of Winnipeg, in 1881. In 1901 she married Pierre Hogue, a Métis born in 1877 in St. Charles Parish, west of the city. For a short time, the young couple lived with Pierre’s mother, Betsy Degagné, in the town of St. Boniface, while Pierre found work as a farm labourer.[86] Soon the couple moved to south Fort Rouge, where both had relatives.

Pierre’s elder sister, Marie Adele Wendt, lived at 577 Jessie Avenue and took in their mother.[87] Another sister, Julia, had moved to south Fort Rouge with her husband, Charles Logan, and his parents, John and Marie Logan, some time before 1901. The Logans had been neighbours of the Henry family in St. Norbert at least since the 1870s. In “the French settlement” the Logans lived in the bush, but they were one of Winnipeg’s “first families.”[88] John Logan’s grandfather, Robert, the leading businessman in Red River from the 1820s to the 1850s, had two families, the first with his Saulteaux wife, and, after her death, with an English widow. The fortunes of his two sets of children differed significantly.[89] Alexander Logan, from the second family, became Winnipeg’s mayor and one of the city’s wealthiest men in the 1880s. A Métis daughter and granddaughter married white businessmen,[90] but the men moved away from the city. Son Thomas became a farmer in St. Norbert, but his son, John, was landless in 1881 and a labourer.[91] He still worked as a labourer while in south Fort Rouge. After his wife died, sometime between 1906 and 1911, and getting older, John moved in with his sister, Margaret, the widow of wealthy businessman William Gomez Fonseca. John’s son and daughter-in-law, Charles and Julia, lived not far away on Corydon Avenue in 1911.[92] Later John did acquire a farm in Narcisse, Manitoba, which Charles operated. John Logan spent some time at the farm, but he passed his last fourteen months before his death in 1922 in the Middlechurch Old Folks Home, a charitable care facility.[93]

After Pierre Hogue and his sisters settled in Fort Rouge, their Aunt Isabella moved there from the centre of the city. Born in the Métis community of Baie St. Paul in 1859, she had lived near Prince Albert, North West Territories, in 1880s with her Aboriginal husband. After the deaths of her husband and son, she returned to Manitoba in 1887 and in 1891 was living in Winnipeg with her new husband, Fred Savage, a clerk born in England.[94]

Pierre and Julienne Hogue remade their identities after their move to “the French settlement”: they anglicized their names, becoming Peter and Julia Hogg and naming their sons Mark and James. Peter also became active in the Liberal Party, hosting political meetings at their home.[95] He worked as a labourer and farmed near their house at the end of Mulvey Avenue, where they lived until at least the First World War.[96] Their marriage broke down and, when Peter volunteered for military service in 1915, he declared himself unmarried and gave Isabella Savage as next of kin.[97]

After military service, Peter did not return to Fort Rouge immediately. In 1921 Julia and son Mark were living on their own, still on Mulvey Avenue, in a three-room shack. Both worked, Julia doing housework for which she received $300 in the past year, while Mark earned $400 as a labourer.[98] Peter came back to Rooster Town sometime in the 1930s. He was living at 1003 Weatherdon Avenue in 1939 when he was struck and killed by a train as he walked along the Canadian National Railway mainline near his home.[99] For a time in the 1940s Julia lived at 1141 Lorette Avenue. She probably moved in with son Mark and daughter-in-law Alice at 1145 Weatherdon Avenue until the former’s death on Christmas Day 1951 and the latter’s a month later.[100] Thereafter, Julia resided at 1155 Weatherdon with Frank Gosling, originally from St. Norbert, until his death in 1958.[101] She stayed in the house and her widowed sister, Mathilda, moved in with her. Prior to their eviction in 1959 the two sisters, with their nine cats and a shaggy dog, were visited by a Free Press reporter, who observed photographs on the wall showing “a young and pretty” Julia with her “dapper husband,” Peter.[102]

Family connections drew the Henrys, Hogues/Hoggs, Logans, and others to south Fort Rouge at the end of the nineteenth century when no place remained on the land for the second Métis generation after Manitoba joined Canada. Some, like the Bérards, found decent wage labour and a lifestyle that distracted from their ancestry. Others stayed within “the French settlement” and then Rooster Town, aided by friends and kin, like the Smiths and Dunnicks, and picked up labouring or hauling work when they could. Others drifted on, leaving behind the elderly, like the Henry sisters, who had lived and raised their families there through much of their adult lives. What these three family histories exemplified, however, was the extensive web of relationships that connected Métis people to one another, but also that linked the impoverished residents of mid-twentieth-century Rooster Town to an earlier generation of Métis who had been promised in 1870 that their children were entitled to land.

Living in Rooster Town

Living in Rooster Town, as in the French settlement earlier, offered residents inexpensive shelter and, for the vast majority who were Métis, the support of extended kin and friends. Some families, though not all of their members, stayed for several generations. For others, residence was temporary and transitional, until they found work or other accommodation in the city or until they moved on. All were economically marginal and, in the opinion of many within the white community, socially undesirable as well.

American sociologist Nels Anderson observed in the 1920s that a slum “always remains the habitat of the socially and economically impotent folks; a retreat for the poverty-ridden and a last resort for the maladjusted.” Anderson was sympathetic to “the socially and economically impotent,” and his identification of behaviours judged unacceptable by the dominant culture as “maladjustment” was his description rather than his judgment. Some people did not fit into the mainstream. An aversion to the time-discipline of wage labour or the failure of lifelong monogamy or the need to seek respite in alcohol might at best be among the very few options presented to those who confronted generations of poverty and racism. As Judith Fingard contended in her study of the underclass of Victorian Halifax, the behaviours of the marginal might manifest pathologies provoked by “family violence, poverty, lovelessness, interdependence, persistence and state intervention.”[103] Anderson’s identification of two slum populations, one suffering economic hardship and the other exhibiting behaviour unacceptable to outside society, does help to describe the ways in which residents of Rooster Town were perceived.

Over its lifetime Rooster Town and its residents became increasingly marginalized, and it became less of a transitional community and more a locale of last resort and refuge. Some families did live there through several generations, but given the typically large families of Rooster Towners, a significant number of even the persistent families left for locations unknown. The first generation of Métis families in south Winnipeg in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was probably better off than those who lived there from the 1930s. The Canadian Northern Railway was hiring for its Fort Rouge car shops and yards and on its construction crews. As well, working-class immigrants and Canadians acquired houses along Pembina Highway close to the rail shops and yards, creating demand for labour of various kinds.

François Bérard and his sons, for example, all reported steady employment to the census enumerator in 1901 and 1911. François found work as a carpenter in both years, as did his son Frederick in 1911, who had been a teamster at the time of the earlier census. In 1911 Frank Jr. and Ernest worked as a teamster and a water boy on a construction crew respectively. Son Florent, a labourer in 1901, had become a fireman with the CNR in 1911. Also employed by the CNR, as a switchman, was Edward Villburn. Other Métis men, Bernie Butchart, Alfred Coyle, and Alex Morrisette, were labourers in 1911, but they were able to find work for the whole year, as was carpenter Alex Parisien. Being outside the city’s pound limits allowed residents to let their livestock roam freely and feed where they could. That was helpful for those with horses who, like William Smith, became teamsters and hired their relatives and neighbours for labouring. As late as the 1930s, reporter John Dafoe recalled, “Everybody had a horse. There were horses everywhere.”[104]

The Great Depression brought harder times. A city official recalled that during those years every family, several hundred people in total, received municipal relief, at least in the winter months.[105] The rest of the year labouring work, landscaping in particular, could be found, but in the cold weather it was back on relief. That employment pattern continued into the 1940s and 1950s. Word of work spread among neighbours, one telling another when jobs were available. In the 1950s, for example, several men worked for the same employers: Metropolitan Construction, J. H. From’s landscaping, and the city.

Some residents could not work. By the 1950s, for example, a number of the elderly, including Julia Hogg and Mathilda Conway, survived on their old age pensions. Some of those who worked had to live in Rooster Town because their wages were attached to cover past debts. Jim Halchaker, who was not Métis, earned $200 a month in 1959 as a city garbage man, while his wife Rose received $36 a month in family allowance for their five children. But he had been seriously ill and the city withheld payments to cover long-standing hospital bills.[106]

Uncertain employment was accepted as something to deal with as best one could. When there was work, one worked hard; when there was no work, one got by. One Métis man whose family moved in the early fifties to a house on the edge of Rooster Town recalled looking for work after quitting school: “I went into the construction trade, because it was ‘manly’ and I didn’t want my father to say I was weak and stupid. I come from a cowboy family where no one was ever allowed to say he was tired, hurting or just couldn’t cope.”[107]

But coping was difficult and meant securing shelter as best one could. Houses in Rooster Town were often self-built shacks, constructed from lumber scavenged around the tracks and elsewhere or ripped at night from the inside walls of boxcars parked on nearby rail sidings. Sometimes a small house or shack in the area that was becoming more desirable for development was dragged away to Rooster Town. Some shacks had shed roofs with the interior divided into two or perhaps three rooms; some had peaked roofs, which permitted a sleeping loft entered by a ladder from the main floor.

Not all residents owned their homes; there was a rental market in Rooster Town. Some built another house for larger personal accommodation, or moved into more established neighbourhoods and rented out their former dwelling; others built a shack for rental. Occasionally an owner fell on hard times and sold a shack to another resident who rented it back. By the 1950s rents were between $15 and $20 a month, and Rooster Town’s major landlord, “Jimmy” Parisien, owned several shacks besides his own home at 1145 Weatherdon Avenue[108] (see figure 3).

Families were large and houses crowded. Albert and Louisa Tanguay and their eleven children moved into Rooster Town from St. Adolphe, Manitoba, in 1947. Their home at 1092 Hector Avenue, set off in the woods, was later described as a “crude one and a half storey shack” with no services. The ground floor was a single room with a stove, a table, two chairs, and a bed. The parents and three children slept there, while the other eight children huddled together for warmth in the tiny attic, which was reached by a rickety ladder.[109]

A few years later, a Tribune reporter visited the shack in which Archie Cardinal and his wife Belva lived with their eight children, aged nine months to fourteen years. Just two rooms, its six-by-eight-foot kitchen contained a stove and two water barrels. The living/bed room was a bit larger, with a couch and a cot. The exterior walls were clad on the inside with cardboard. The health problems brought to school were symptomatic of the difficulties that mothers confronted in keeping their overcrowded homes clean without running water and sewer connections.[110]

Families had to haul water three-quarters of a mile from a standpipe at the corner of Cambridge Street and Dudley Avenue. Those who could afford it bought water at eighty cents a barrel from a resident who hauled it in his truck. Others sent their children. One mother confided that fetching water in winter was hard on her sons: “Last night they were pulling the sleigh home and crying with the cold and somebody on the way asked them in to get warm. The nine-year-old walked right in but the seven-year-old wouldn’t—he’s proud. When he got home his mitts were frozen stiff”[111] (see figure 4).

The absence of services revealed the city’s ambivalent attitude. Officials were reluctant to locate a standpipe any closer, since they feared that people would never move away if life’s daily routines were too easy in Rooster Town.[112] On the other hand, they occasionally encouraged the poor to move there. In 1959 Ernest Stock, who was not Métis, revealed to a reporter, “The city told us to move here. We had a place on Ellice Avenue but we had to move because the plumbing was no good. A city man suggested we move out here. I didn’t have any money to buy any land then.”[113]

Similarly, the city was ambivalent about collecting taxes. It could assess taxes against squatters for the value of their shacks, even though they did not own the land. Collecting taxes was another matter. After city assessors had gone through the area, residents sometimes hitched their shacks to teams of horses and dragged them to another location.[114] Even when an assessment notice could be delivered, collecting proved difficult. William Roussin of 1259 Carter Avenue, an address almost a half-mile beyond the road’s end, was a test case. He bought the house in 1948 for $130 and paid no taxes, despite their assessment, through 1954 when the city seized his shack. The city then attempted to charge him rent, again with no success. Despite authorization to evict the family of five, the city continued to hope that Roussin would pay rent but admitted that it had little to gain by forcing them out.[115] One thing that city government disliked more than Rooster Town was the prospect of finding housing for low-income families that it dislocated.[116] As well, if it collected taxes from shanty dwellers, it might be asked to provide services.

Figure 3

Winnipeg Free Press reporter outside 1145 Weatherdon Avenue in Rooster Town, March 1959

James and Mary Parisien lived at 1145 Weatherdon Avenue in 1959. They had lived there for only a year or two but had resided in south Fort Rouge since the 1920s. Before them, the house had been occupied by Ernest and Julia Lepine, who earlier had lived on Ash Street. The house number provided the reference point from which the addresses of the unnumbered houses could be reckoned. Despite their simple construction, the shanties displayed some variations in status. The wooden shingle siding of the Parisien residence distinguishes it from the tar-paper cladding of some of its neighbours. Beside 1145 Weatherdon is a home with painted trim and sashes.

In some instances officials did intervene. In June 1947, just a month after her family moved into Rooster Town, Louisa Tanguay was fatally burned when the coal oil stove that she was refilling exploded. Her eldest daughter, Margaret, quit school to look after the family. Five months later her father, Albert, was killed when a sewer that he was digging collapsed and buried him. The orphaned children were taken into care and separated from each another. The six daughters were placed in homes operated by Roman Catholic nuns, three boys entered orphanages, while two others were sent to the Manitoba School for Mental Defectives in Portage la Prairie.[117]

The city was prepared to act aggressively in response to complaints from suburban taxpayers. After the Rockwood School controversy in 1951, the city found rental accommodation for six or seven families elsewhere. As the Winnipeg Tribune reported, “Some of the Rooster Town families are on relief, and over those the city has some control.”[118]

Control over Rooster Town and its residents reflected current prejudice about the Métis and the poor. As Lagassé argued in his 1959 report, authorities had limited expectations about their behaviour, accepting their satisfaction with poor living conditions, their apparent unwillingness to work, their weakness for alcohol, and their tendency to engage in petty crime.[119] “The discouraging thing to welfare workers,” a Tribune reporter wrote, “is that they are not sure the people of Rooster Town want anything better … Basically, there is nothing to prevent the men from improving their families’ housing.”[120] Along with a certain tolerance for people who were thought not to want or to know better went strict enforcement, when apparently incorrigible behaviour was judged to have gotten out of hand.

What was experienced in Rooster Town as good times, authorities treated as disorderly behaviour and “vice.” Living in close quarters with friends and kin promoted conviviality and celebration. People made their own fun and entertainment. The assistant director of Winnipeg’s welfare department, Gerald W. O’Brien, explained, “They would all party together and some of the parties got pretty rough. The police were always being called out after the parties.”[121] Some of the residents gained notoriety as a result.

In 1952 the newspapers had reported one affray at 1144 Weatherdon Avenue at the home of Rose Cardinal, who was the daughter of Julia Hogg’s sister, Mary Smith.[122] Off and on from the late 1930s through the 1950s, when they were not in jail or residing downtown, Rose and her husband, John Cardinal, had lived together or separately on Weatherdon Avenue. In 1952 Rose had recently moved back after finishing a six-month jail term for stealing $16 from a hotel room.[123] Her thirty-nine-year-old husband, not long out of jail for stealing a purse, was living downtown at 216 James Avenue, but visited his wife.[124] During “a drinking party” at Rose’s house, John got into an argument with one William Bell. John grabbed Bell around the neck and beat him, while his wife rifled through Bell’s pockets, taking $90, a watch, and a cigarette lighter from him. Pleading guilty, they were sent to prison, this time for fifteen months.[125] Neither of the Cardinals was long out of prison before again getting into trouble with the law. The following year Rose, then “of no fixed abode,” was sentenced to eight months in jail for stealing $48 from a man during a drinking bout.[126] In 1955 John Cardinal and Eugene Archie Parisien, with whom he shared a Rooster Town shack at 1207 Hector Avenue, were convicted of auto theft. The two men had stolen a twenty-five-year-old car that had been left for two years on a vacant lot.[127]

For the most part, the exploits of the Cardinals typified the petty crime that attracted attention to Rooster Town, and regular readers of the city’s newspapers would have recognized the recurring names and addresses from that part of town. Carter Avenue resident Patrick Parisien, who was reported to have a criminal record, received a six-month sentence in 1945 for stealing a bicycle.[128] Three years later, the fifty-seven-years-old Parisien pled guilty, and received a month in jail, for stealing a $3 snow shovel. He and an accomplice had been looking for work shovelling snow; after a Montrose Avenue householder declined their services, they took a shovel that had been left outside the house.[129] Hubert Rene Laramee, age twenty-one years, of 1023 Weatherdon Avenue was found guilty in 1957 of stealing two hubcaps worth $18 from a parked car and was fined $50.[130] A few years later, up on charges for driving without a licence and drunk driving, the prosecutor described Laramee as having “one of the worst driving records I have ever heard.” Imposing a $500 fine or three months in jail, the magistrate lectured him, “You just can’t flout the law continually … It means something to every citizen, in Manitoba and Canada.”[131]

Truly serious crime was rare, but when it did occur, it revealed the role of alcohol in exacerbating tense domestic relations. On the night of Friday 15 December 1911, Edward Vilburn of 865 Scotland Avenue shot his wife, Jessie, because he suspected her of infidelity. The police knew Vilburn as “a bad character” who drank heavily and had physically abused his wife in the past. Charged with attempted murder, his trial (strangely) was suspended after the couple reconciled. The judge, however, did warn him not to carry a revolver.[132]

Figure 4

Mrs. Belva Cardinal and Children, 1951

Two of the Cardinal children are standing beside the water can and sled that they used to fetch water in the winter. The short length of the planks that clad the house suggests that they might have been removed from rail boxcars parked nearby or that they had been scavenged from various locations. The building is raised above ground to keep it above the spring run-off; it also facilitated moving the structure.

A second violent incident occurred in 1935. On 12 July John Nolin, an unemployed Métis agricultural labourer, beat his neighbour, Walter Henry Arthur of 908 Ash Street, to death. Nolin had been drinking heavily for two weeks since leaving his wife, Alice, the daughter of William and Mary Jane Dunnick. Nolin had sought Arthur’s advice concerning his marital problems while the two were drinking homebrew late at night in the bush. Too drunk to remember what happened, Nolin claimed he had killed Arthur after an argument turned violent. Nolin was found guilty of manslaughter and received an eight-year sentence. Later he and his wife reconciled.[133]

Newspaper reports on life in Rooster Town and its residents reflected and reinforced prejudices against the socially marginal. Rather than the consequences of racism and poverty, observers saw unacceptable behaviour. Missing was sensitivity to the strength of ties to family and friends and their willingness to help when relations and acquaintances were in need. Also undocumented were the small and daily triumphs, as there surely were, against the challenges of everyday life.

Figure 5

Grant Park Plaza development announced, 1953

The area enclosed in the black rectangle had been part of Rooster Town in the 1940s and early 1950s. With the development of the shopping centre, Rooster Town residents moved west onto adjacent vacant land.

The End of Rooster Town

Through the 1950s commercial and residential development intensified in south Winnipeg. Developers, seeking to assemble land for new housing or for shopping centres, received sympathetic hearings from a municipal government that wanted to reduce the inventory of land seized for non-payment of taxes. Land became too valuable to leave for Métis squatters.

To facilitate development in south Winnipeg the city negotiated with the Canadian National Railways to remove tracks that obstructed automobile access. In June 1953 the CNR announced its plans to tear up its infrequently used Harte subdivision branch line and sell its right-of-way to the city for a major east-west transit corridor, Grant Avenue, which would run right past Rooster Town.[134] Negotiations between the city and the railroad dragged on for another two years, and several more years elapsed before plans for the new thoroughfare were approved.[135]

The delay frustrated property firms who in the summer of 1953 had announced their intentions to develop the area. The city had finalized an agreement with Arle Realty giving that firm the option to purchase 58 acres of land south on the southern edge of that corridor for $175,000. The developers proposed to build Winnipeg’s first shopping centre—a $10 million complex of stores and offices, anchored by the Canadian head office of an American financial institution, a multi-storey department store, medical centre, and hotel. As well, the developers were given right of first refusal to purchase another 60 acres to the west of their project.[136] The roughly 120 acres under consideration was Rooster Town. Arle Realty lost the race to develop the city’s first shopping centre, but Grant Park Shopping Centre, occupying about half of the space projected, still became a major commercial area.[137] The rest of the optioned land was turned over for residential construction. The remaining 60-acre tract was Rooster Town’s last refuge (see figure 5).

Figure 6

Ernest and Elizabeth Stock were evicted from Rooster Town in 1959

Suburban development continued through the 1950s, and pressure on the schools continued. By the end of the decade another high school was needed in the southern part of the city. In 1959 the city sold fifty acres south of Grant Avenue to the Winnipeg School Division No. 1 as the site for Grant Park High School. In response to pressure from the division to remove squatters before the beginning of the school year in September, the city agreed to share the expense of offering fourteen Rooster Town families cash payments of $75 to move by 1 May or $50 by 30 June or face eviction proceedings. The residents could move their shacks to land not owned by the city if they wanted, and if they could find any; if not, their shacks were to be burned.[138]