Résumés

Abstract

This paper explores the relationship between the words and images in the drawing Interior, Lavender Bay by the Australian artist Brett Whiteley (1939-1992). This artwork combines the depiction of the artist’s home with a written element composed of the title, date, artist’s monogram, and a brief inscription. By examining Whiteley’s use of words and images in this drawing, the verbal/visual synergy that underpins his language is emphasized as a key aspect of his communicative appeal. The interpretive lens used in order to analyze Interior, Lavender Bay is interlingual translation. Translating Whiteley’s words from English into Italian allows not only to decipher the literal meaning and comprehend the symbolic function of his words, but also to highlight the relation between art and language. From this perspective, drawing on W. J. T. Mitchell’s Picture Theory (1994), the paper aims to discuss the functioning of images and the way in which interlingual translation might bring out latent connections in the source, opening a window on the interdisciplinary encounter between creative processes in the visual art and translation theory and practice.

Keywords:

- Brett Whiteley,

- interlingual translation,

- imagetext,

- word and image,

- self-representation

Résumé

Cet article explore la relation entre les mots et les images dans le dessin Interior, Lavender Bay de l’artiste australien Brett Whiteley (1939-1992). Cette oeuvre artistique associe la description de la maison de l’artiste à un élément écrit constitué par le titre, la date, le monogramme de l’artiste et une brève inscription. À travers l’examen de l’usage que fait Whiteley des mots et des images dans ce dessin, la synergie verbale et visuelle qui sous-tend son langage est soulignée comme un aspect essentiel de sa capacité communicative. L’instrument interprétatif utilisé pour analyser Interior, Lavender Bay est la traduction interlinguistique. Traduire les mots de Whiteley de l’anglais à l’italien permet non seulement de déchiffrer le sens littéraire et de comprendre la fonction symbolique de ses mots, mais aussi de mettre en évidence la relation existant entre l’art et le langage. Dans cette perspective, en s’appuyant sur la Picture Theory de W. J. T. Mitchell (1994), cette étude vise à examiner le fonctionnement des images et la façon dont la traduction interlinguistique peut faire ressortir des connexions latentes présentes dans le « texte » de départ, en ouvrant une fenêtre sur la rencontre interdisciplinaire entre les processus de création dans les arts visuels et la théorie et la pratique de la traduction.

Mots-clés :

- Brett Whiteley,

- traduction interlinguistique,

- imagetext,

- mot et image,

- autoreprésentation

Corps de l’article

This paper explores the relationship between the words and images in the drawing Interior, Lavender Bay by Australian artist Brett Whiteley (1939-1992). This artwork combines the black and white depiction of the artist’s home with a written element composed of the given title, the date, the artist’s monogram, and a brief inscription in verses. By examining Whiteley’s use of words and images in this drawing, the verbal/visual synergy that underpins his language is emphasized as a key aspect of his communicative appeal.

The method used in order to analyze Interior, Lavender Bay is interlingual translation, which thus becomes an interpretive lens. Translating Whiteley’s words from English into Italian—the author’s native language and culture—allows not only to decipher the literal meaning and comprehend the symbolic function of his words, but also to highlight the relation between art (regarded as the range of activities performed towards the creation of aesthetic objects, environments, or experiences that are appealing to our senses and emotions) and language (conceived as a dynamic set of visual, auditory, and tactile symbols of communication regulated by a system). From this perspective, drawing on the concept of “imagetext” as expressed in W. J. T. Mitchell’s Picture Theory (1994), the paper aims to discuss the functioning of images and the way in which interlingual translation might bring out latent connections in the source, opening a window on the interdisciplinary encounter between creative processes in the theory and practice of visual art and translation.

The goal of this enquiry is not so much to identify the parallelism between the words and the images as to explain how and why their relationship is an aspect inherent to Whiteley’s self-representation. Since this self-representation is constructed by blending heterogeneous signs that activate different channels, modes, and intellectual and emotional responses, Whiteley’s self-depiction can be regarded as a composite phenomenon, which entails various media and stimulates multiple sensory and cognitive reactions.

In recent times, the relations between translation and art have inspired a young and emerging field and a flourishing range of creative and academic experimentations.[1] Like these studies, this contribution is aimed at inspiring debate and knowledge about translation as a heuristic and imaginative process. The approach utilized is pluralistic and reflects the hybrid nature of the topic, allowing the concept of translation to open a window onto “the relations between images and texts so as to allow them the relative autonomy that benefits from their distinctive forms and practices” (Venuti, 2010, p. 149).

The paper is structured in four main parts. The first part presents Interior, Lavender Bay as a particularly significant example of Whiteley’s interartistic, intermodal, and intertextual self-representation. The second part illustrates the methodology adopted to analyze Whiteley’s self-representation as expressed in Interior, Lavender Bay, namely, interlingual translation. The third part contains the analysis of the drawing, oriented by the translation process. The fourth part synthesizes the observations that emerge throughout the analysis, suggesting that Whiteley’s poetics of excess not only represents him as a total artist, but also reflects his failed endeavour to exert control on reality, seen as an all-embracing realm.

1. Interior, Lavender Bay and Whiteley’s Self-Representation

Born to a well-off family and educated at two of the most elite schools in New South Wales, Brett Whiteley manifested his artistic talent very early in life. His first significant painting is considered to be The Soup Kitchen (1958), produced while he was still a young student (Hilton and Blundell, 1996, pp. 15 and 40-69). Since then and until his premature death, Whiteley created a substantial number of works: not only paintings, drawings, and sculptures, but also writings. His artist’s studio in Sydney was posthumously converted into a museum of paintings, sculptures, photographs, drawings, catalogues, diaries, letters, and films, managed by the Art Gallery of New South Wales. This varied collection emphasizes the connection between Whiteley’s images and words, calling attention to the role that words played in the development and reception of his work.

Autobiography is not only one of the most pervasive themes in Whiteley’s production of the 1970s,[2] but also one of the aspects that best display the connection between verbal element and visual element in his work. Noteworthy is not so much the quantity of Whiteley’s self-depictions as the fact that this self-representation is expressed and determined by the combination of words and images. Inscriptions often accompany and complement his self-portraits, enriching his visual self-representation with a verbal element that integrates and hybridizes his pictorial work. In this sense, the verbal and the visual are inseparable components of a complex phenomenon.

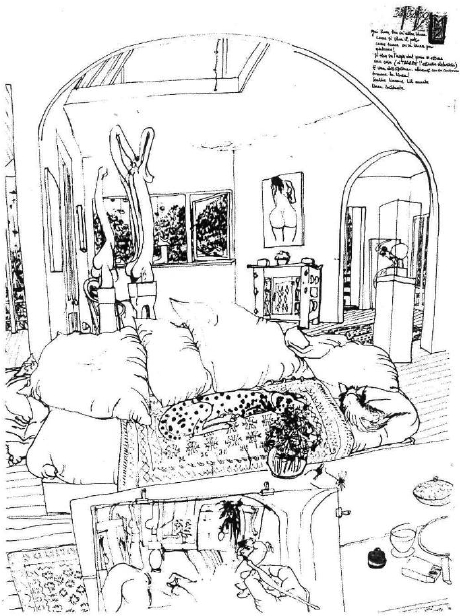

Nowadays, Whiteley is regarded as one of Australia’s most prolific, talented, and expressionistic artists of the 20th century, and the drawing Interior, Lavender Bay (1976) (Figure 1) belongs to the most successful period of his career. While living and working in Sydney, his native town, in the late 1970s, Whiteley achieved widespread popularity with a series of paintings and drawings representing his home and studio in Lavender Bay, on the north shore of Sydney. These autobiographical works, depicting the most intimate part of the artist’s world—his domestic and work environment—can be considered Whiteley’s artistic and spiritual manifestos.

Figure 1

Brett Whiteley, Interior, Lavender Bay

Pen and ink on paper, 76 x 57 cm. Private collection.

Among this series of works, Interior, Lavender Bay is a particularly clear example of Whiteley’s self-representation, produced by the juxtaposition of images and words. As in the European landscape draughtsmanship of the 18th and 19th centuries (i.e., William Turner, John Ruskin and Samuel Palmer) (Wettlaufer, 2000) as well as in the Asian tradition,[3] this artwork juxtaposes the physical depiction of Whiteley’s hand drawing the interior of his house and a short poetic composition located in the upper right corner of the drawing, near his monogram and the date. Indeed, the act of self-representing is not only explicit, in that his right hand is depicted, but also interartistic and intermodal, because a poetic inscription accompanies the artwork. Moreover, the references to other authors and their works add to the intertextual dimension of Whiteley’s self-depiction.

First and foremost, cross-references, thematic affinities, and points of divergence across Whiteley’s visual work and writing show how, through the use of different artistic practices, Whiteley seeks to represent himself not only as a painter, but also as a writer. From this viewpoint, the first way to investigate Interior, Lavender Bay is to analyze the literary dimension of his visual work and the pictorial references in his writing. This implies comparing writings (such as letters, statements, diaries, poems) and paintings as parallel and complementary expressive forms. Through the analysis of the narrative and poetic forms in which Whiteley’s images are reflected and transformed, we can understand the cultural topoi related to them, the mythology that they display.

As the Italian scholar Michele Cometa suggests, investigating the link between words and images means not only studying their similarities and differences, but also the modifications that images produce on literary language, as well as their cultural significance (Cometa, 2004, pp. 16-17).

Furthermore, the relationship between the words and the images in Interior, Lavender Bay needs to be understood as a key feature of Whiteley’s intermodal self-representation. Because this self-representation is constructed by a blend of signs that activate different cognitive and emotional responses, it must be regarded as a polylogic phenomenon (Sarapik, 2009, p. 277), which entails different media and stimulates complex sensory and intellectual reactions.

From this perspective, drawing upon Mitchell’s theory, I consider Interior, Lavender Bay as an “imagetext”(Mitchell, 1994, p. 89), i.e., a composite work that combines image and text.[4] This entails paying attention not only to images, or to images and words separately, but to words and images in a relationship. Reading the words embedded in Interior, Lavender Bay implies not only decoding their literal meaning, but also perceiving their layout, position, interaction with the composition, and extratextual implications. Verbal and visual appear inextricably intertwined.

The concept of Whiteley’s self-representation as an intermodal phenomenon echoes Mitchell’s seminal proposition that every art is composite and every medium is mixed, regardless of the more or less evident relationship among different disciplines and techniques. In this regard, Mitchell writes:

The image/text problem is not just something constructed “between” the arts, the media, or different forms of representation, but an unavoidable issue within the individual arts and media. In short, all arts are “composite” arts (both text and image); all media are mixed media, combining different codes, discursive conventions, channels, sensory and cognitive modes.

ibid., pp. 94-95

In agreement with the scholar, I deem it necessary to account for the image-word relationship in Interior, Lavender Bay as a dynamic intrinsic to Whiteley’s intermodal self-depiction.

The third dimension of Whiteley’s self-representation is intertextuality. This fundamental notion—introduced by Julia Kristeva (1969) and re-elaborated by Gérard Genette (1997) as “transtextuality,” or literature of second degree—is that no text, much as it might like to appear so, is original and unique in itself. Rather, it is a network of inevitable and unconscious references to and quotations from other texts. Other texts condition the meaning of each text. The text is an intervention in a cultural system.

As shown in the analysis of Interior, Lavender Bay, the intertextual dimension of Whiteley’s work is extraordinary. On the one hand, it is possible to identify a series of links between different works by Whiteley, which call attention to recurrent themes and features in his work. On the other, his references to other artists bring to excess an established tradition in Western art history, according to which artists appropriate from other works.

His work refers not only to Australian visual art and literature, but also to the European artistic tradition, including French post-impressionism, symbolism, surrealism, cubism, Dada; and international currencies and practices such as modernism, abstract expressionism, pop art, and conceptual and performance art. This eclectic range of intertextual references makes his self-representation an act of multiple appropriation.

It is worth remembering that Whiteley’s intertextual links are not limited to painting, but include also literature, although this relationship remains an object of debate. Whiteley’s biographers Margot Hilton and Graeme Blundell claim that although Whiteley always showed curiosity in poetry and literature, he never deepened his literary knowledge in a consistent way (Hilton and Blundell, 1996, p. 107). According to Sandra McGrath (1979, p. 126), by contrast, his interest in poetry was among the most significant sources of inspiration for his pictorial work. In particular, McGrath explores the mythical presences of Baudelaire and Rimbaud in Whiteley’s work, delving into the personal and the emotional elements filtering his comprehension of French poetry.

Whiteley’s eclectic range of pictorial and literary references reflects his tendency to appropriate, adapt, and transform different sources into original recreations, which express a unique, yet fragmented self. An assembled combination of imports and remakes transfers and re-elaborates an all-inclusive patchwork of intertextual identities.

2. Employing Translation as a Hermeneutic Tool

Investigating Interior, Lavender Bay as an example of Whiteley’s interartistic, intermodal and intertextual self-representation necessarily leads to a discussion invoking perspectives from a variety of disciplines: a discussion which moves beyond narrowly defined pictorial analysis to broader research paradigms. The practical consequences of this approach are visible in the analysis of the drawing, where I employ interlingual translation as a tool to reach a better understanding of Whiteley’s verbal-visual self-representation. In this sense, the primary goal of translation is not to create an artwork that will circulate in Italian or to communicate with a new audience: the translation is ephemeral and serves strictly to deepen the analysis of Whiteley’s work. Rather than as a final product, translation is seen as a hermeneutic process—what George Steiner would call a phenomenon of cultural production (Steiner, 1975, p. 437; Torop, 2000, p. 71).

My method encompasses four main phases: the imagetextual analysis, the translation process, the re-elaboration of the observations stimulated by translation, and the final Italian translation. The first step encompasses the painterly analysis and the literary explanation of the imagetext under scrutiny. After examining the visual elements of Interior, Lavender Bay, I will investigate the semantic, phonic, graphic, and prosodic characteristics of the words comprised in this artwork drawing on the method illustrated by Cragie et al. (2000), and Nord (2005). The first aim is to show that Whiteley’s words complete and sometimes clarify his visual representation, adding biographical, conceptual, or symbolic elements that affect our understanding. The second suggestion is that the combination of signs and sounds is as meaningful as the choice of vocabulary—repetitions, alliterations, anaphors, and onomatopoeias emphasize particular aspects of Whiteley’s self-representation, conveying a sense of obsession, solitude, and void. Furthermore, the medium, shape, colour, size, and position of his words are analyzed as technical and symbolic choices that affect the viewer’s understanding. Finally, the length of verses, their shape, rhythm, and space organization are explored as features that strongly contribute to convey meaning.

The second phase implies turning Whiteley’s words from English into Italian. Why do I translate? Obviously, translation allows me to grasp the literal meaning of Whiteley’s words, and makes these words accessible to an Italian-speaking audience, with plenty of potential implications on the reception, interpretation and understanding of his work. Accessibility, however, is only a vital and noteworthy consequence. More importantly, translation serves a deep hermeneutic purpose: it facilitates the exploration of a series of multi-leveled meanings, deepens the textual analysis, and stimulates a new critical interpretation of Whiteley’s visual art, which emphasizes the link between his literal use of other artists’ imageries and his symbolic self-image. Thus, translation is an interpretive act, echoing a form and meaning of the source text “in accordance with values, beliefs and representations in the translating language and culture” (Venuti, 2007, p. 28).

When translating, my physical involvement with the source produces a performance that expresses spontaneous associations and unworked possibilities. In particular, because his words are immersed in a drawing, their physical position, texture, dimension, proportion, and handwriting are as significant as their literal meaning: therefore, I instead use typographic variants, colour, and repetitions of patterns as tangible ways to render Whiteley’s intermodal self-depiction.[5]

The reflections stimulated by translation are recorded, by writing down as much as possible the reasoning that has accompanied the translation process. This procedure draws upon think-aloud protocols (TAP), a much-discussed empirical and experimental method that has been used by translation experts since the 1980s to study translation as a cognitive process (see Ericsson and Simon, 1993; Kussmaul and Tirkkonen-Condit, 1995; Bernardini, 1999; Danks et al., 1997, p. 139; Tymoczko, 2007, p. 167). In fact, my partial recording does not aim to analyze the cognitive implications of my analysis, but rather to document some details of the mental images stimulated by the source, shifting the attention from the final result (my Italian translation) to the process (the translation-oriented analysis).

Finally, the observations raised by the translation process prompt a reflection on the interartistic, intermodal, and intertextual dimensions of Whiteley’s self-depiction. These reflections eventually lead me to produce a final Italian translation. During the translation process, two languages—English and Italian—meet, generating unexpected outcomes. The mixture of Italian and English underpinning my discussion can at times render the results unusual or disturbing.[6] However, it is programmatically offered as a tangible reflection of the cross-cultural process of analysis. Indeed, in the co-presence of at least two languages, the conference of the tongues (Hermans, 2007) expands the source, inserting new images, associations, and meanings. As Hermans suggests, the translator’s “agency, subjectivity, intentionality, [and] management of discourse” (Hermans, 2007b, p. ix) retraces and multiplies the creative impulse of the original.

This methodology is devised as an experimental model that could be replicated on other artworks that incorporate image and text, including other art forms, such as visual poetry or graphic novels. My suggestion is that translation into languages other than Italian would yield similar insights on the relationship between words and images in this particular artwork, or on others, although each translation-based analysis of the literary and pictorial references included in the artwork under scrutiny would be shaped and enriched not merely by the translator’s linguistic and cultural background, but also his/her multisensory and synesthetic consciousness.

3. Theory in practice: Interior, Lavender Bay [Interno, Lavender Bay]

Let us start from the analysis of the visual elements. Interior, Lavender Bay represents Whiteley while he is drawing the interior of his home in Lavender Bay, in Sydney. The work depicts the artist’s hand and notebook, the house’s interior, and the view outside the window. In the upper right corner is located a poetic inscription, the date of composition, and the artist’s monogram “BW.”

The image is a black and white sinuous depiction of Whiteley’s house, which evokes tranquility, beauty, and intimacy. It portrays the most intimate portion of Whiteley’s visible world: his private house. The house is populated with architectural elements (arches, a door, a chimney, and two open windows), artworks (some sculptures on the left side, and a drawing hung on the furthest wall), furniture (a bed, cushions, a pot with flowers, a coffee table, rugs, a chair, a plinth surmounted by a sculpture under glass), animals (two dogs, a bird out of the window), human presence (Whiteley’s right hand, the nude in the drawing on the wall, and the female figure that he is drawing in his notebook), and landscape (the view on the Sydney Harbour from the window in the background—an allusion to Lloyd Rees’ work).[7] As in Matisse’s Red Studio,[8] everything expresses a sense of harmony, calm, sensuality, comfort, and domesticity.

The interplay of black and white calls attention to the lines shaping the objects. We perceive the scene precisely because we see these lines: the lines of the arches, the lines of the sculptures, the lines of the timber floor, and the lines drawn on Whiteley’s notebook jointly compose the imagetext. We see the Interior, because we distinguish lines.

Having examined the visual elements, we can turn to the semantic, phonic, graphic, and prosodic characteristics of Whiteley’s words. As mentioned above, in Interior, Lavender Bay, the black and white depiction of the artist’s home is combined with a written component, consisting of the given title, the date, the artist’s monogram, and a brief inscription in verses. While in other works such as Remembering Lao-Tse (Shaving off a Second) words and images express similar concepts (Zanoletti, 2011), in this drawing the contrast between the serenity of the images and the melancholic anguish of words is particularly strong. In this sense, this work appears contradictory, evocative, and ambiguous.

The thematic[9] title Interior, Lavender Bay [Interno, Lavender Bay] simply describes what can be seen in the picture, i.e., the interior of Whiteley’s house. The toponym “Lavender Bay” cannot be translated, however it is essential to notice that “Lavender” is not only the name of the area where Whiteley lived, but also the name of a plant (lavender) and a colour (lavender corresponds to a pale to light purple/violet). The referential contrast between the last meaning of the polysemous word lavender and the drawing, which is black and white, produces an unsettling oxymoronic effect.

While the drawing is rather large (it measures approximately 76 x 57 cm), and occupies almost the entire paper surface, Whiteley’s written lines concentrate in the upper right corner, where the wall is white and empty. Only by moving closer (as if we are in front of the original artwork) or by using a magnifying glass (as if we are observing its printed reproduction), can we read the twelve-line text.

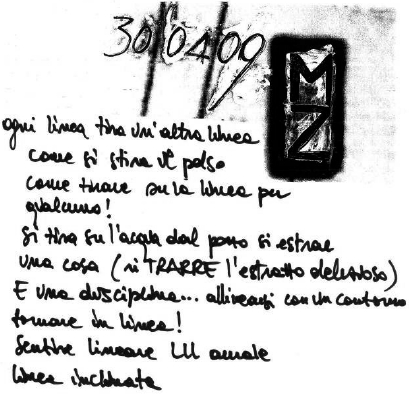

These verses can be interpreted in terms of a brief comment of the very process of producing the image, or as the poem that this drawing illustrates. Below is my transcription in Times New Roman of the inscription:

22/Nov/76

BW

all lines lead to other lines

how the wrist twists

like doing a line for

someone!

You draw water from the well you draw

Something out (to DRAW delicious extraction)

Its a discipline … get in line with an out line

line up!

listen linear LLL in ear

lean line

Here, as in other works, Whiteley writes in vers libre or free verse. Poetry allows him to break sentences into short phrases, is visually more seductive, and accounts for his self-representation as a poet-painter, that underpins his use of alter egos like Charles Baudelaire, Arthur Rimbaud, Dylan Thomas, and Bob Dylan.[10] Alliterations (especially the sound [l]), repetitions (the word line appears eight times; draw is repeated three times), parallelisms (someone/Something), figures of speech (the internal rhyme wrist twist; the epanalepsis LLL) (Zanoletti, 2007, pp. 200-203), rhythm (the use of short verses; the enjambments “draw/Something out and for/someone”), and emphatic punctuation (the suspension “…”; the use of exclamation marks; the parenthesis), they all work as emotive devices. Rather than stimulating an intellectual response, they excite our senses, overwhelming us with sinuous sounds.

In parallel, while shaping a sonic wave that allures our emotions, Whiteley plays with the semantics of words in such a way that their seductive sound and metaphorical meaning array more profound and dramatic implications. The key word line literally refers to the poetic lines contained in the inscription and the black lines constitutive of the drawing. However, doing a line also means injecting heroin, and can refer to Whiteley’s drug addiction, which in the 1970s became particularly strong, interfering with his artistic activity.[11] Another allusion to heroin informs the expression “draw water from the well,” a metaphor for drawing liquid heroin from the syringe, and “DRAW delicious extraction,” which refers to the pleasurable derangement of the senses produced by drugs.

Before translating, it is useful to compare the inscription with Whiteley’s own definition of drawing, as expressed in a notebook annotation written during his sojourn in Morocco in 1967 (McGrath, 1979, pp. 79-81). In this definition there is in nuce the problematic link between creation and addiction at the core of the inscription:

Drawing is the art of being able to leave an accurate record of the experience of what one isn’t, of what one doesn’t know. If one of the purposes of life is to know oneself, then a great deal of time is spent investigating things one already knows. So a great drawing is either confirming beautifully what is commonplace, or probing authoritatively the unknown.

ibid., p. 216

The relationship between the drawing process, experience, and knowledge is at the heart of Whiteley’s reflection. This connection becomes the main theme of the inscription embedded in Interno, Lavender Bay, where Whiteley plays with the concept of “drawing a line” as in producing a drawing and “drawing a line” as expanding consciousness by altering the mind with heroin. This idea can be related to the symbolists’ and surrealists’ conception of alcohol, drugs and dreams as the gates to the transcendent realm of art.

My Italian translation of the transcription aims to echo the emotive effect of sounds and rhythm and, at the same time, seeks to account for the multiplicity of meanings hidden in Whiteley’s lines. A first rendering of the inscription, interlined with the record of the translating process, reads:

22/Nov/76

BW

Ogni linea tira un’altra linea

[letteralmente, tutte le linee conducono ad altre linee]

come prilla il polso

[come gira il polso, but prilla alliterates [l]; polso is depicted in the drawing, it is Whiteley’s hand]

come tirando una linea per

qualcuno!

[doing a line = tirare una linea = disegnare = DRAW]

tirare fuori l’acqua dal pozzo si tira

[here I lose the graphic alliteration of w, the initial of Whiteley; well means pozzo but also bene = properly/good, and reminds of the opposition good/evil, where the well and the evil is the drug]

qualcosa fuori (DISEGNARE deliziosa estrazione)

[estrarre qualcosa = decipher meaning from Whiteley’s lines]

e una disciplina… stai in linea con una linea

[e (and) should be è (is), but e emulates Whiteley’s spelling mistake—its instead of it’s—in line refers to conformism, out line means graphic outline, but also the marginal status of a junkie, being out of the mainstream]

allineati!

[Futuristic punctuation and preposition, and military term, which matches “disciplina”]

odi LLL lineari nell’orecchio

[the repetition LLL alludes to obsession, compulsion, routine]

linea esile

[life is a lean line, art is made of lean lines, a lean line separates art and life]

The key word is line, which refers to drawing lines in the first verse (“all lines lead to other lines,” also translated literally (letteralmente) in notes as “tutte le linee conducono ad altre linee”) in “doing a line,” and “lean line” (Whiteley is using a fine line in this work), while it is used in a metaphorical sense in “get in line,” “out line” (used instead of outline, so that the word out is repeated) and “line up.”[12] Also the words all, lead, like, well, delicious, linear, listen, LLL, and lean echo the sound [l] and the l shape of line. The Italian linea is the closest translation of the English line. The sound [l] is lost in tutte, pozzo and come, but is retrieved in le, prilla, and polso. In fact, “come prilla il polso” has been chosen instead of “come gira il polso” for phonetic reasons.

An interesting linguistic analogy is the parallel between “doing a line” not only as making a drawing, but also as inhaling cocaine and the Italian expressions “fare una riga” (“draw a line”) and “farsi una riga” (“snorting a line [of cocaine]”).[13] Thus the concept of drawing is associated with the idea of taking narcotics, with an ambiguous and disquieting effect.

Another noteworthy cross-cultural correlation is the link between the word allineati! (“line up!”) and Italian Futurism. As the founder of Futurism, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti wrote in 1909, in his manifesto titled Uccidiamo il chiaro di luna [Let’s Murder the Moonshine],

Guardate laggiù, quelle spiche di grano, allineate in battaglia, a milioni.... Quelle spiche, agili soldati dalle baionette aguzze, glorificano la forza del pane, che si trasforma in sangue, per sprizzar dritto, fino allo Zenit. Il sangue sappiatelo, non ha valore nè splendore, se non liberato, col ferro o col fuoco, dalla prigione delle arterie!

Marinetti, 1983 [1909], p. 17

Look down there, those ears of grain lined up for battle by the million… those ears, agile soldiers with sharp bayonets, glorify the power of bread that is transformed into blood and shoots straight up to the Zenith. Blood, as you know, has no value or splendour until it is freed from the prison of the arteries with iron and fire!

Marinetti, 1991 [1909], p. 55

Whiteley’s exclamation marks (“line up!”), a trademark of his writing (James, 2000), suggest dynamicity and vitalism, two ideas strongly evoked by Futurists. Moreover, Marinetti’s image of blood that sprizza (spurts) suggests the image of shooting drugs into one’s vein (although Marinetti uses the word arterie).

The connection between Whiteley and the father of Italy’s best known vanguard tradition is certainly very compelling, far beyond the fact that the artists are free-associated based upon some comparable imagery. The principles of excess, on which Italian Futurism is founded, can be related to Whiteley in a more thoroughgoing comparison, as some excerpts from Marinetti’s Manifesto suggest (cited in Zanoletti, 2012, pp. 182-183):

1. Noi vogliamo cantare l’amor del pericolo, l’abitudine all’energia e alla temerità. [...]

4. Noi affermiamo che la magnificenza del mondo si è arricchita di una bellezza nuova: la bellezza della velocità. Un’automobile da corsa col suo cofano adorno di grossi tubi simili a serpenti dall’alito esplosivo... Un’automobile ruggente, che sembra correre sulla mitraglia, è più bello della Vittoria di Samotracia. [...]

7. Non v’è più bellezza, se non nella lotta. Nessuna opera che non abbia un carattere aggressivo può essere un capolavoro.1. We intend to sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and fearlessness. [...]

4. We affirm that the world’s magnificence has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing car whose hood is adorned with great pipes like serpents of explosive breath—a roaring car that seems to ride on machinegun fire is more beautiful that the Victory of Samothrace. [...]

7. Except in struggle there is no more beauty. No work without an aggressive character can be a masterpiece.

The text of Marinetti’s decalogue is gravely solemn, almost religious. In both the Italian version and the English rendition, the lexicon utilized comprises numerous abstract nouns, and the chain of sentences resembles an antiphonic psalm. Not only does the repetition of the personal pronoun we (Noi) at the beginning of the sentence add intensity, but also the poet pushes the emphasis to the extreme through the onomatopoeic images of the “racing car” (“automobile da corsa”), the “roaring car” (“automobile ruggente”), and the “machinegun fire” (“mitraglia”).

Marinetti’s celebration of velocity, virility and aggression is echoed by Whiteley’s obsessive and bombastic style. Whiteley’s “inclination for extremes,” “the desire to do as one pleases, without much sense of responsibility,” and “the fascination with chaos, power and violence” (Olsen, 1996) are reflected in his excessive, redundant, repetitive, pleonastic, and almost tautologic language, which always entails a sense of rhetorical excess.

It must be considered that in Whiteley’s work the themes of burning life and excess are not only an allusion to Baudelaire’s and Rimbaud’s bohemian lifestyle, but also to his chemical addiction (be it pure coincidence, in the English version of the Manifesto, the words speed and pipes also recall the semantic realm of altering substances). Whiteley himself discussed his relationship with drugs not only in terms of excess and sentience, but also artistic inspiration. To him, they were not only a form of freedom, but also an artistic stimulus.[14]

In Whiteley’s inscription, the repetitions of verbal and visual lines emphasize the continuity between the ink used to write the words and the images, stressing the interartistic dimension of his self-representation. The inscription reinforces the self-references contained in the drawing, by calling attention to the artist’s self-depiction. In the drawing there are many sexual and sensual references and the artist is depicted at work, while he is composing the drawing itself. At the same time, these repetitions are symptomatic of Whiteley’s tendency to overload, by insisting on the same idea in an emphatic, often excessive way.

I have tried to maintain the double meaning of draw as in “draw a line” and “draw water” using the Italian tirare/tirare su, and emphasising riTRARRE (“to portray”) in capital letters as a key word of the drawing.

The final translation of the transcription not only transposes the sound quality of Whiteley’s use of words, but also accounts for the underlying reference to heroin.

22/Giu/09

BW

Ogni linea tira un’altra linea

come si stira il polso

come tirare su la linea per

qualcuno!

Si tira su l’ acqua dal pozzo si estrae

una cosa (ri TRARRE l’estratto delizioso)

E una disciplina …allinearsi con un contorno

tornare in linea!

sentire lineare LLL aurale

linea inclinata

This translation aims not only to reproduce the alliteration of the sounds [s], and [t], but also at evoking the act of injecting heroin. This is why I have changed prilla into si stira, and “deliziosa estrazione” into “l’estratto delizioso.” Moreover, “to DRAW” has become “ri TRARRE,” which mirrors tirare/trarre, meaning draw. The final image of “linea inclinata” is meant to evoke the idea of imbalance.

The interaction with the source has produced a further version of the inscription (Figure 2, next page), which imitates Whiteley’s writing. The illustration corresponds to the Italian translation of the inscription as it appears in the drawing. The inscription is handwritten, and reciprocates Whiteley’s handwriting. By replacing his handwriting with my own, I physically interact with the source imagetext, and respond to Whiteley’s self-representation by making my gestural performance visible. I have also replaced Whiteley’s monogram with my initials, so as to translate the communicative function of the source, and to make it evident that mine is a creative transposition, and not a fake remake (this final translation has transformed the source more radically than the first version).

Figure 2

My Italian translation of Whiteley’s handwritten inscription

Finally, the date has changed: it is the date of production of the translation. This emphasis on autobiographism intends to highlight Whiteley’s insistence on the theme of the fugacity and instantaneity of drawing, as expressed in some of his writings.[15]

When inserting the handwritten translation into Whiteley’s image (Figure 3), the rest of the image remains untouched, but the imagetext as a whole has changed, provided that we move closer to the words or look to the inscription through a magnifying glass. The intervention of the translator has prolonged Whiteley’s “open work,” entering “into something which always remains the world intended by the author” (Eco, 1989, p. 19).

Figure 3

Brett Whiteley, Interno, Lavender Bay. Italian translation Brett Whiteley’s Interior, Lavender Bay

4. A Translation Studies Approach to Art

An interdisciplinary approach that has considered Whiteley’s Interior, Lavender Bay as an imagetext combined with an innovative perspective on translation has yielded new insights into the interpretation of his work, highlighting a series of complex issues inherent in his self-representation that up until now had not been adequately considered. The translation process has facilitated identifying and highlighting the link between the words and the images in Interior, Lavender Bay, suggesting that they jointly contribute to Whiteley’s interartistic, intermodal, and intertextual self-depiction. This appears to be the result of the combination of a verbal element and a visual element that are spatially contiguous, intratextually linked, and yet medially heterogeneous.

To begin with, the translation of Whiteley’s words has entailed a careful examination of Whiteley’s visual self-depiction. This scrutiny has shown that through his pictorial self-representation, Whiteley calls attention to the intellectual and the technical qualities of his artistic personality. To this end, he represents himself by drawing his right hand, while the rest of his body remains implicit. Furthermore, the joint analysis of Whiteley’s images and words through translation has highlighted two major features: his overloaded style, and his self-representation as a total artist. The first feature is a symptom of Whiteley’s poetics of excess, i.e., his tendency to overload his work with a myriad of different signs, so as to reinforce his message. The second feature is realized through the combination of words and images whereby Whiteley aims at representing himself not only as a painter, but also as a poet.

First, in Interior, Lavender Bay, the co-presence of words and images produces an overload of signification, which draws attention to Whiteley’s poetics of excess. The title and the date are conventional yet crucial components of Whiteley’s self-representation. The combination of paratexts and images produces a complex ensemble of signs, in which the words reiterate or clarify the images, diverting, attracting, or guiding our understanding. In this sense, Whiteley’s rhetorical overplay can be seen as a fetishistic practice, and the repetition of the same ideas through verbal and visual signs highlights his tendency to represent himself in a bombastic and even buffoonish way. Worth noting, the title, the date, and the inscription have different roles in relation to Whiteley’s self-depiction. The title Interior, Lavender Bay clarifies the subject and highlights some aspects of his artwork, so that the viewers feel guided in their reading of the drawing. In this sense, the function of the title is not only to identify and clarify the piece of art, but also to establish some contact between the artist and the public. The date serves as a biographical element that alludes to Whiteley’s physical presence, thus implying his historical intervention. The inscription also contributes strongly to define Whiteley’s self-depiction, by adding information about the artist, evoking his presence, or more importantly, verbalizing the meaning of the artwork. In fact, the inscription serves as a metonym, which in praesentia of the artist multiplies his presence.

Secondly, as the inscription is neatly separated from the images, it is evident that Whiteley represents himself not only as a painter, but also as a poet. The separation between the drawing and the writing has the effect of representing Whiteley as a double artist. Whiteley’s tendency to perform as a total artist can be viewed as a compensatory and fetishistic mechanism aiming for control, that lies halfway between a great Gesamtkunstwerk, an all-embracing work of art that makes use of all or many art forms, and an unwitting pastiche similar to a commedia. As in a commedia, Whiteley’s performance is based on archetypes (i.e., the artist, the muse/model, the alter ego), repetition—verbal and pictorial—and largely improvised format (i.e., use of the line as a virtuoso exercise), which call attention to his addiction to drugs. From this perspective, Whiteley’s compulsion to incorporate literary and pictorial references in his work suggests the artist’s failed attempt to exert power on reality, seen as an all-inclusive realm.

Whiteley’s self-depiction has been accounted for and reciprocated by my translation, through a deliberate and liberal appropriation of his work, in which author and translator become two composite writing subjects (Karalis, 2007, p. 231). My translation has freed the text from its hic et nunc, opening its modality to the questioning of another linguistic pattern and another cultural tradition. The co-presence of English and Italian has produced unforeseen associations, observations, and discoveries. Through the dialogue between the author and the translator, different historical perspectives, cultural agendas, and geographical dislocations have provided the setting to a new interpretive path.

One of the major challenges of this approach has been the attempt to merge visual, linguistic and literary analysis drawing upon fields as diverse as translation studies, comparative literature, semiotics, and art historical visual analysis. Different disciplines have provided a rich theoretical framework to analyze Whiteley’s self-representation in all its complexity. The shift from textual to imagetextual can hopefully stimulate further reflections on transdisciplinarity as the locus to contribute actively to a new understanding of cultural phenomena. Indeed, going beyond established frameworks is a way to take part in the ever-evolving dynamics of art.

Parties annexes

Biographical note

Margherita Zanoletti completed a PhD in Translation Studies at the University of Sydney (2010), with a thesis on the Australian artist Brett Whiteley (1939-1992), and currently serves as subject and reference librarian at the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore in Milan. Her monograph on the Aboriginal writer Oodgeroo Noonuccal (written with Francesca Di Blasio), which includes the first Italian translation of the collection of poems “We are Going” (1964), was published in 2013 (University of Trento Press).

Notes

-

[1]

In this sense, this article sits comfortably with other cotributions in translation theory (see Torop, 1995), visual studies (see Mitchell, 1994), semiotics (see Eco, 1989; Genette, 1997), and art history (see Smith, 2009) which engage with this relationship to different degrees. The themes discussed in this paper also refer to recent contributions to cultural translation, such as Emily Apter’s discourse on translatability in the global market and Deborah Cherry’s current investigation on the ways in which images, genres and visual forms are transformed by exchanges within and between cultures.

-

[2]

A careful observation of the two major publications about Whiteley’s work—the catalogue of the retrospective Art and Life (Pearce, 1995) and the monograph compiled by McGrath (1979)—reveals that he produced not only a prolific amount of self-portraits, but also a substantial number of paintings and drawings that are not self-portraits but do include Whiteley’s physical depiction. For this reason, his tendency to self-represent has been often criticized as one of the most obsessive leitmotifs of his production (see Maloon, 1983; McDonald, 1995).

-

[3]

I am referring here to the Chinese and Japanese tradition of juxtaposing a painting and a poetic inscription, accompanied by the name of the artist (Perniola, 2006, pp. 129-134). On the influence of Asian art on Whiteley’s work, see also Zanoletti (2011).

-

[4]

Mitchell defines the imagetext in various ways, using typography to distinguish its variants (ibid.): “the typographic conventions of the slash to designate image/text as a problematic gap, cleavage, or rupture in representation. The term ‘imagetext’ designates composite, synthetic works (or concepts) that combine image and text. ‘Image-text,’ with a hyphen, designates relations of the visual and verbal.”

-

[5]

This approach, recently discussed by Clive Scott (2010), hinges on the phenomenological assumption that we perceive the universe with our entire body, and encourages regarding translation as physiological involvement with a text instead of a cognitive activity.

-

[6]

In order to facilitate the reading, when appropriate, I have added footnotes with the English translation of the annotations recorded in Italian.

-

[7]

The Australian modernist painter Lloyd Rees (1895-1988) was particularly renowned for his landscape paintings, in particular his depictions of the Sydney Harbour (see Duyker, 2008, pp. 34-53).

-

[8]

Whiteley’s admiration for Matisse, and the Matissean influence on his series of works produced in the 1970s are discussed by McGrath (1979, pp. 180-182).

-

[9]

The reference to thematic and rhematic—namely, titles that refer to the subject (thematic) and those that refer to the genre (rhematic)—draws on Genette’s study of the descriptive function of titles (Genette, 1997, p. 89).

-

[10]

As previously mentioned, Whiteley’s use of alter egos is a major mechanism of self-depiction in absentia. This mechanism is particularly evident in works such as Rembrandt (Pearce, 1995, Plate 117), Fiji Head—To a Creole Lady (ibid., Plate 82), and Portrait of Baudelaire (ibid., Plate 123).

-

[11]

As discussed above, Whiteley’s drug addition lasted from the end of the 1960s until his death from overdose. On the relationship between Whiteley’s work and drugs, see also the criticism by Adams (1973) and Olsen (1996).

-

[12]

The rambling nature of Whiteley’s inscription suggests the Swiss artist Paul Klee’s famous aphorism about drawing as “taking a line for a walk.” On Klee’s work and thought, see Franciscono (1991).

-

[13]

In English, the specific “line” word associated with heroin use is the verb to mainline, which means to inject heroin.

-

[14]

In an interview with the ABC journalist Andrew Olle (1990), Whiteley commented: “I find it very difficult to dismantle… my addiction from my talent. Part of having gift is… in a way there’s something spiritually and physically and mentally sort of immoderate about me or about it… [...] You know there are certain areas of the imagination that can be deliciously opened up with alcohol or with chemicals, and I was petrified that I wouldn’t be able to reach those areas. And it’s delusion of course, because one’s talent or what one is, is central, and the best way to allow that to truly operate is to be clean… but I do miss it occasionally, I do miss the abstraction…”

-

[15]

In an undated diary, Whiteley wrote: “To collect back glances in the early hours is my job / Crystalline sobriety / Points to point in nature where the conservings of old chinamen, older by living / Know when to place at the feet of your mind / The sight, as accurately seen. / (now) not withstanding the myriad (butchering of difference to sameness… with you too of course. One hopes you will fly in aspirational air + forget or land in human care + remember.”

Bibliography

- BERNARDINI, Silvia (1999). “Using Think-Aloud Protocols to Investigate the Translation Process: Methodological Aspects.” In J. N. Williams, ed. RCEAL Working Papers in English and Applied Linguistics 6. Cambridge, University of Cambridge, pp. 179-199.

- COMETA, Michele (2004). Parole che dipingono [Words that Paint]. Roma, Meltemi.

- CRAGIE, Stella et al. (2000). Thinking Italian Translation. London, Routledge.

- DANKS, Joseph H. et al. (1997). “Cognitive Processes in Translation and Interpreting.” Applied Psychology: Individual, Social and Community Issues, 3, pp. 137-160.

- DUYKER, Edward (2008). “Lloyd Rees: Artist and Teacher.” The Journal of the Sydney University Arts Association, 30, pp. 34-53.

- ECO, Umberto (1989). The Open Work. Cambridge MA, Harvard University Press.

- ERICSSON, K. Anders and Herbert A. SIMON (1993). Protocol Analysis: Verbal reports as Data. Cambridge, MIT Press.

- FRANCISCONO, Marcel (1991). Paul Klee: His Work and Thought. Chicago, The University of Chicago Press.

- GENETTE, Gérard (1997). Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- HERMANS, Theo (2007). The Conference of the Tongues. Manchester, St. Jerome Publishing.

- HERMANS, Theo (2007b). “Foreword.” In M. Perteghella and E. Loffredo, eds. Translation and Creativity. London, Continuum, pp. ix-x.

- HILTON, Margot and Graeme BLUNDELL (1996). Whiteley: An Unauthorised Life. Sydney, Pan Macmillan.

- KARALIS, Vrasidas (2007). “On Transference and Transposition in Translation.” Literature & Aesthetics, 17, 2, pp. 224-236.

- KRISTEVA, Julia (1969). Séméiôtiké: Recherches pour une Sémanalyse. Paris, Edition du Seuil.

- KUSSMAUL, Paul and Sonja TIRKKONEN-CONDIT (1995). “Think-Aloud Protocol Analysis in Translation Studies.” TTR, VIII, 1, pp. 117-199.

- MARINETTI, Filippo Tommaso (1983). Teoria e invenzione futurista [Futurist Theory and Invention]. L. De Maria, ed. Milan, A. Mondadori.

- MARINETTI, Filippo Tommaso (1991). Let’s Murder the Moonshine: Selected Writings. Trans. R.W. Flint and Arthur A. Coppotelli. R.W. Flint, ed. Los Angeles, Sun & Moon Classics.

- MCGRATH, Sandra (1979). Brett Whiteley. Sydney, Bay Books.

- MITCHELL, William J. Thomas (1994). Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

- NORD, Christiane (2005). Text Analysis in Translation. Theory, Methodology, and Didactic Application of a Model for Translation-Oriented Text Analysis. Amsterdam/New York, Rodopi.

- PEARCE, Barry (1995). Brett Whiteley: Art & Life. London, Thames & Hudson.

- PERNIOLA, Mario (2006). “The Japanese Juxtaposition.” European Review, 14, 1, pp. 129-134.

- SARAPIK, Virve (2009). “Picture, Text, and Imagetext: Textual Polylogy.” Semiotica, 174, pp. 277-308.

- SCOTT, Clive (2000). Translating Baudelaire. Exeter, University of Exeter Press.

- SCOTT, Clive (2006). Translating Rimbaud’s “Illuminations.” Exeter, University of Exeter Press.

- SCOTT, Clive (2010). “Intermediality and Synaesthesia: Literary Translation as Centrifugal Practice.” In I. Boyd Whyte, ed. Special Issue of Art in Translation. Oxford, Berg, pp. 153-170.

- SMITH, Terry (2009). What is Contemporary Art? Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

- STEINER, George (1975). After Babel: Aspects of Language & Translation. Oxford, Oxford University Press, third edition.

- TOROP, Peeter (1995). Total’nyj Perevod [Total Translation]. Tartu, Izdatel’stvo Tartuskogo Universiteta.

- TOROP, Peeter (2000). “Intersemiosis and Intersemiotic Translation.” European Journal for Semiotic Studies, 12, 1, pp. 71-100.

- TYMOCZKO, Maria (2007). Enlarging Translation, Empowering Translators. Manchester, St Jerome Publishing.

- VENUTI, Lawrence (2007). “Adaptation, Translation, Critique.” Journal of Visual Culture, 6, 1, pp. 25-43.

- VENUTI, Lawrence (2010). “Ekphrasis, Translation, Critique.” In I. Boyd Whyte, ed. Special Issue of Art in Translation. Oxford, Berg, pp. 131-152.

- WETTLAUFER, Alexandra K. (2000). “The Sublime Rivalry of Word and Image: Turner and Ruskin Revisited.” Victorian Literature and Culture, 28, 1, pp. 149-169.

- ZANOLETTI, Margherita (2007), “Figures of Speech | Figure Retoriche: Verbal and Visual in Brett Whiteley.” Literature and Aesthetics, vol. 17, no 2, pp. 192-208. [http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:http://ojs-prod.library.usyd.edu.au/index.php/LA/article/download/4945/5639].

- ZANOLETTI, Margherita (2011). “Translating an Artwork: Words and Images in Brett Whiteley’s Remembering Lao-Tse.” In R. Wilson and B. Maher, eds. Words, Sounds and Performances in Translation. London, Continuum, pp. 7-25.

- ZANOLETTI, Margherita (2012). “Marinetti and Buvoli: A Translation Studies Approach to Italian Art and Culture.” In P. Arancibia et al., eds. Shaping an Identity. Adapting, Rewriting and Remaking Italian Literature. New York, Legas.

- ADAMS, Bruce (1973).“Whiteley Rampant.” Sunday Telegraph, 14 January.

- MALOON, Terence (1983). “Maloon on Whiteley on Van Gogh.” TheSydney Morning Herald, 23 July.

- MCDONALD, John (1995). “What If Brett Whiteley Was Just Very, Very Overrated?” The Sydney Morning Herald, 9 September.

- OLSEN, John (1996). “Whiteley.” The Sydney Morning Herald, 29 June.

- OLLE, Andrew and Brett WHITELEY (1990). Sydney. Unpublished interview.

Critical works

Newspaper articles

Interviews

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Brett Whiteley, Interior, Lavender Bay

Figure 2

My Italian translation of Whiteley’s handwritten inscription

Figure 3

Brett Whiteley, Interno, Lavender Bay. Italian translation Brett Whiteley’s Interior, Lavender Bay