Résumés

Abstract

While censorship is an external constraint on what we can publish or (re)write, self-censorship is an individual ethical struggle between self and context. In all historical circumstances, translators tend to produce rewritings which are ‘acceptable’ from both social and personal perspectives. The translation of swearwords and sex-related language is a case in point, which very often depends on historical and political circumstances, and is also an area of personal struggle, of ethical/moral dissent, of religious/ideological controversies. In this paper we analyse the translation of the lexeme fuck into Spanish and Catalan. We have chosen two novels by Helen Fielding—Bridget Jones’s Diary (1996) and Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason (1999)—and the translations into the languages mentioned. Fielding’s acclaimed first novel has given rise to a distinctive genre of popular fiction (chick lit), which is mainly addressed to young cosmopolitan women and deals unconventionally with love and sex(uality). Historically, sex-related language has been a highly sensitive area; if today, in Western countries at least, we cannot defend any form of public censorship, what we cannot prevent (nor probably should we) is a certain degree of self-censorship, along the lines of an individual ethics and attitude towards religion, sex(uality), notions of (im)politeness or (in)decency, etc. Translating is always a struggle to reach a compromise between one’s ethics and society’s multiple constraints—and nowhere can we see this more clearly than in the rewriting(s) of sex-related language.

Keywords:

- censorship,

- self-censorship,

- translation,

- sex-related language,

- “fuck”

Résumé

La censure est une contrainte externe de ce que nous pouvons publier ou (ré)écrire, et l’auto-censure est une lutte morale individuelle entre soi-même et le contexte. Dans toutes les circonstances historiques, les traducteurs ont tendance à produire des réécritures qui sont « acceptables » non seulement du point de vue social mais aussi personnel. La traduction de jurons et du langage sexuel est un exemple paradigmatique, qui dépend très souvent des circonstances historiques et politiques et qui est aussi un espace de lutte personnelle, de dissension éthique/morale, de controverses religieuses/idéologiques. Dans cet article nous analysons la traduction du lexème « fuck » en espagnol et catalan. Nous avons choisi deux romans de Helen Fielding – Bridget Jones’s Diary (1996) et Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason (1999) – et leurs traductions dans les langues mentionnées. Le premier roman fait naître un genre spécifique de fiction populaire (la chick lit), qui est principalement adressé aux jeunes femmes cosmopolites et qui traite, d’une façon peu conventionelle, de l’amour et du sexe (ou de la sexualité). Historiquement, le langage sexuel est un espace social très sensible; aujourd’hui, il est évident que dans les pays occidentaux nous ne pouvons pas approuver toute forme de censure publique, cependant, nous ne pouvons pas non plus éviter un certain degré d’auto-censure, en fonction de l’éthique individuelle de l’auteur, de son attitude envers la religion ou la sexualité, ou de ses notions de la politesse ou de la décence. La traduction est toujours une lutte pour atteindre un compromis entre l’éthique individuelle et les contraintes multiples de la société – et c’est dans les réécritures du langage sexuel que nous le distinguons le plus nettement.

Mots-clés:

- censure,

- auto-censure,

- traduction,

- langage sexuel,

- « fuck »

Corps de l’article

1. Censorship and (Self)Censorship(s) in Translation: Between the Social and the Individual

Theory of translation seriously warns us that translating any text faithfully is, by definition, an imposible task—“a utopian task”, as Ortega y Gasset (1937, p. 93) put it. In the same vein, the daily practice of translation only confirms—less romantically and more cruelly—that the distance separating the source from the target texts is a gap impossible to bridge. Beyond the lesser or greater skills of the translator, or even the uneven correspondence between languages, there seems to be an imprecise middle ground, an abyss which is monopolized by a variety of ‘censorship(s)’ and ‘self-censorship(s)’.

While censorship can be considered “the suppression or prohibition of speech or writing that is condemned as subversive of the common good” (Allan and Burridge, 2006, p. 13) and constitutes an external constraint on what we can publish or (re)write, self-censorship is an individual ethical struggle between self and context. In all historical circumstances, translators tend to censor themselves—either voluntarily or involuntarily—in order to produce rewritings which are ‘acceptable’ from both social and personal perspectives.[2]

Throughout history there have been official ‘censorships’ which were supported by specific political or religious projects. In periods of political unrest and of fierce dictatorships (Italy or Spain under Fascist dictators Mussolini and Franco, or Nazi Germany under Hitler), they imposed strict control over all forms of mass communication and imposed tight censorship measures, such as pre-publication or editorial censorship and favoured the systematic exercise of self-censorship. Favourite issues for censorship were sexual morality, political orthodoxy, religion and racist considerations (see Rabadán, 2000, for a study of literature, film and theatre censorship under Franco’s regime). As a prototypical example, during Franco’s dictatorial regime, only literature by minor and/or harmless foreign-language authors were extensively published, such as Richmal Crompton’s Just William series or Agatha Christie’s detective stories. Plots involving extramarital affairs, divorce, suicide or alcoholism were carefully avoided, both in fiction and in films, as they were likely to constitute a threat to the model of society advocated by the Francoist regime (Vega, 2004; Gallego, 2004).

However, there are a series of ‘censorships’ whose exercise does not depend upon forceful imposition by an external ‘institution’ but rather upon ideological, aesthetic or cultural circumstances. Even in historical periods of political stability, there are institutions, hierarchies or schools which manage to impose their cultural criteria and, what is more, what is acceptable or unacceptable to translate. More often than not, it is the translators themselves who consider their options and, accordingly, exercise an indeterminate series of ‘self-censorship(s)’, which are not explicitly imposed, but that the translators find necessary to safeguard their professional status or their socio-personal environment. What is striking is that these self-censorship(s) are applied both in periods of unrest (whether political, ideological or religious) and in periods where translators’ professional autonomy is apparently respected. It must be acknowledged that the translators’ profession has always been prone to minor betrayal(s) in the form of hurried renderings, pressure imposed by customer or the cultural or political environment. Nowadays, more specifically, media groups, political parties, religious institutions and a large number of other pressure groups favour predictable and unpredictable forms of self-censorship, ranging from blatant political partisanship[3] to sudden and violent prudishness in reactions towards sexual language, blasphemy[4] or religious satire.[5]

Most probably, the history of translation is the history of its infidelities, which are much more visible that its successes. A translator’s success becomes—paradoxically—the best guarantee of his/her own invisibility. The long list of infidelities throughout the history of translation is shared by both official censorships and the endless self-censorships which are enacted daily. Human behaviour—whether individual or collective—has always seemed to be governed by some sort of underlying moral limit or taboo. We feel the—it seems—anthropological need to ban and punish, in order to impose a moral or ideological project we are identified with.

In the field of official censorships, innumerable examples of mutilated film dubbings of American films released in Spain under Franco’s dictatorship are documented (Rabadán, 2000). State censorship, for an authoritarian regime, was a first-order ideological instrument for moral indoctrination, and “controlling information and filtering cultural products were deemed of utmost importance” (Merino and Rabadán, 2002, p. 126). And besides these mutilated scenes, which probably contained religious or sexual references, we observe a wider phenomenon—that of endless texts that a government, through its repressive instruments, has prevented from being published or released. We cannot but be highly surprised by the non-translation of authors like Fay Weldon, Joanna Trollope, Jeannette Winterson or even Barbara Cartland. A key trait of this period is the absence of translations of erotic literature; a case in point is Fanny Hill (see Cleland, 2000), as this novel embodies the prototypical accusation of ‘obscenity’—i.e. a visual/verbal act(ion) which offends readers/viewers and defeats their moral expectations.[6] Toledano analyzes thoroughly the phenomenon of the translation of obscenity, which she identifies as one of the most powerful methods of public or state censorship. Fanny Hill was—along with a handful of other novels—not translated until 1976, as it most probably advocated natural morality and religion-free sexuality (Toledano, 2003, p. 242).

Self-censorships may include all the imaginable forms of elimination, distortion, downgrading, misadjustment, infidelity, and so on. There are blunt and unrefined instances of self-censorship, whose ideological design is pretty obvious—i.e. The Second Sex (1952), the first (and only) English translation of Simone de Beauvoir’s groundbreaking essay Le deuxième sexe (1949), carried out by Howard Parshley, who “deleted fully one-half of one chapter on history, a fourth of another, and eliminated the names of seventy-eight women” (Simon, 1996, p. 90). The procedure had a clear ideological aim: to minimise women’s significance in history. Much less visible, but all the more surprising, is an example of self-censorship we have found in Maggie ve la luz (2003), the Spanish translation of Marian Keyes’ Angels (2002), one of the most successful and well-known novels of the decade. There may be a certain pattern in the elimination of certain sentences such as sexually explicit “It’d be like licking a mackerel” (Keyes, 2002, p. 169), “lick someone’s mackerel” (ibid., p. 319), “you’re a lickarse” (ibid., p. 395), “narky bitch” (ibid., p. 452); or in the elimination of certain explicit references to lesbianism; or of certain uses of fuck as emphatic intensifier. All this could suggest a certain self-imposed control when translating, or maybe some reservation about the explicit expression of certain sexual behaviours. However acceptable this may be, what is really significant is the omission of a long 1006-word passage where Marian Keyes develops a satirical, and even parodic, comparison between an “LA style” mass (ibid., p. 427)—almost a TV or cinema show where “we ended up practically having sex with the people around us” (ibid., p. 429)—and a mass as experienced in the arch-Catholic Ireland—“My clearest memory of Mass in Ireland was of a miserable priest droning at a quarter-full church, ‘Blah blah blah, sinners, blah blah blah, soul black with sin, blah blah blah, burn in hell…’.” (ibid., p. 428). As to the reason(s) for this self-censorship, we can only speculate: the translator may have felt uncomfortable when dealing with religious feelings, or she may have judged the passage irrelevant or difficult, or she may have wished to object to an unrespectful literary treatment of religious ceremonies.

Among the least obvious types of self-censorship—which can, however, be revealed through rigorous linguistic analysis—are partial translation, minimisation or omission of sex-related terms. For example, Karjalainen (2002) documents the systematic elimination of insults, blasphemies and taboo words (goddam, damn, hell, bastard, sonuvabitch, for Chrissake, for God’s sake, Jesus Christ) in two translations of J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (1951) into Swedish. Similary, the Spanish translation of the same book is also a moral product—a catalogue of omissions and reductions. El guardián entre el centeno (1978) deprives the original from most of its colloquial traits, such as blasphemies or sex-related expletives. The short passage below illustrates perfectly what we mean:

|

|

The Spanish passage is unusually shorter than the original in English. The underlined words or phrases indicate the emotional elements in this short conversation. As we can see, the Spanish translation has practically eliminated all of them and is rendered at times a colourless exchange, devoid of the irreverent, blasphemous tone of Salinger’s characters. Self-censorships—whether done deliberately or unwittingly—seem not only unavoidable but also necessary. They constitute sometimes the most intimate indicators of the translator’s attitude towards the topics, the style or the ideology of the original text. They may be, besides many other things, a site of struggle or resistance. It is only with difficulty that one can imagine a rewriting which is free from biases, prejudices or ideological positions; and in this sense self-censorships have to be accepted as part of the game, as the nuclei upon which the real traslation project is based. Translating is not a transparent activity—it is only human. And human activities tend towards betrayal, misunderstanding and difference. In Krebs’ words:

Every choice made by the translator is a potential act of (self-)censorship. But it is impossible to argue that self-censorship is the only form of choice made by a translator. As we know, a multitude of cultural, historical and ideological factors, personal or socially-determined, can account for any number of choices made.

2007, p. 173

2. The Translation of Sex

The translation of swearwords or of sex-related language is a case in point, which very often depends on historical and political circumstances,[7] but which is also an area of personal struggle, of ethical/moral dissent, of religious/ideological controversies, of systematic self-censorship (Bou and Pennock, 1992).

When translating sex, what is at stake is not only grammatical or lexical accuracy. Besides the actual meanings of the sex-related expressions, there are aesthetic, cultural, pragmatic and ideological components, as well as an urgent question of linguistic ethics. Eliminating sexual terms—or qualifying or attenuating or even intensifying them—in translation does usually betray the translator’s personal attitude towards human sexual behaviour(s) and their verbalization. The translator basically transfers into his/her rewriting the level of acceptability or respectability he/she accords to certain sex-related words or phrases. Analyzing the translation of sexual language into (a) specific language(s) helps draw the imaginary limits of the translators’ sexual morality and, perhaps, gain insights into the moral fabric of a specific community at a specific historical moment.

Elsewhere (Santaemilia, 2005b) I analyzed the trends—very subtle sometimes—which govern the translation of sex-related terms or of sexual innuendoes. I identified “a more or less general axiom at work that prescribes that translation of sex, more than any other aspect, is likely to be ‘defensive’ or ‘conservative’, tends to soften or downplay sexual references, and also tends to make translations more ‘formal’ than their originals, in a sort of ‘hypercorrection’ strategy” (Santaemilia, 2005b, p. 121). Another trend can be added: all translations, in spite of appearances, do respond to a systematic ideological design, as “rewriters adapt, manipulate the originals they work with to some extent, usually to make them fit in with the dominant, or one of the dominant ideological and poetological currents of their time” (Lefevere, 1992, p. 8). The translation of sex, then—with the exception of those periods following authoritarian regimes, where a newly-regained freedom is likely to justify frenziness in translation—,[8] is usually subordinated to perceived notions of political and ideological correctness.

We believe that translating sex-related language may constitute a fertile ground for the articulation of both official ‘censorships’ and the multiplicity of ‘self-censorships’. In the 21st century, there is no apparent state censorship—thousands of books are translated every year and erotic or pornographic literature is distributed without apparent interference. An erotic classic like Fanny Hill is normally found in bookshops, with new editions appearing regularly since the late 1970s,[9] and a fair number of collections of erotic literature are distributed.[10]

Thus, there seems to be no formal ‘censorship’ of those works with explicit or implicit sexual content. We could, however, hypothesize more subtle and imperceptible forms of self-censorship(s), which would affect the territories of religious beliefs, moral attitudes or, ultimately, personal ethics. These self-censorships are difficult to catalogue or spot, quite often involuntarily produced, and focus equally on both significant and insignificant aspects of the source texts. If insignificant, then the translation options can be accounted for in terms of stylistic (ideolectal) variation; in the case of significant changes, they will mostly revolve around contentious ideological, political, religious or social aspects of the target society. And we are trapped within the walls of a paradox: on the one hand, an incomplete or biased translation undermines our right to enjoy a faithful and complete—whatever these grand terms mean—translation of any work; on the other hand, the translator’s right to produce an incomplete or biased translation is a consequence of his/her right to objection on political, religious, moral or even philosophical grounds.

3. The Translation of Sex-Related Terms: The Case of Fuck

In this paper we analyse the translation of the lexeme fuck into Spanish and Catalan. We have chosen two novels by Helen Fielding—Bridget Jones’s Diary (1996) and Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason (1999); henceforth BJ and BJER—and the translations into the languages mentioned. Fielding’s acclaimed first novel has given rise to a distinctive genre of popular fiction (chick lit[11]), which is mainly addressed to young cosmopolitan women and deals unconventionally with love and sex(uality). Among the main features of chick lit we can distinguish a constant reference to sex-related matters and a liberal use of sex-related terms. This is a common feature shared by best-selling authors like Candace Bushnell, Helen Fielding, Marian Keyes, Wendy Holden or Meg Cabot.

In the Bridget Jones books, Helen Fielding has created a new icon of contemporary femininity: Bridget is impulsive, independent and… foul-mouthed. At times she seems to have been designed to counter the traditional female stereotype. Jespersen, for instance, asserts that “[a]mong the things women object to in language must be specially mentioned anything that smacks of swearing” (1922, p. 246); while Lakoff affirms that women “speak around women in an especially ‘polite’ way in return, eschewing the coarseness of ruffianly men’s language: no slang, no swear words, no off-color remarks” (1975, pp. 51-52). Bridget and her friends liberally use swearwords, blasphemies and make bold references to their sex lives. Certainly, a display of sex-related language or a focus on sexual encounters is not the only remarkable discursive feature in Fielding’s novels, but it is not a negligible one either. The chick lit phenomenon goes far beyond that—it offers an attractive stylistic, moral and sexual project to women around the world. Freedom and consumerism go hand in hand, as well as a hunger for independence and glamour. And in this fashionable universe, it seems that part of Helen Fielding’s stylistic project in BJ and BJER depends on the use of sex-related terms and, more specifically, on the (ab)use of the lexeme fuck. Using sexual language is fashionable, perhaps as part of a (larger) picture of the stylization of feminine heterosexuality. We believe it is well worth exploring how all this travels in translation into Romance languages.

McEnery and Xiao (2004) found the word fuck one of the most versatile in the English language, as it is variously used as a general expletive, a personal insult, an emphatic intensifier, an idiom or a metalinguistic device—just to cite a few examples. In this paper we will analyse all the occurrences of the word (fuck) and its morphological variants (fucking, fucked and so on), in order to identify their main pragmatic meanings and implications.

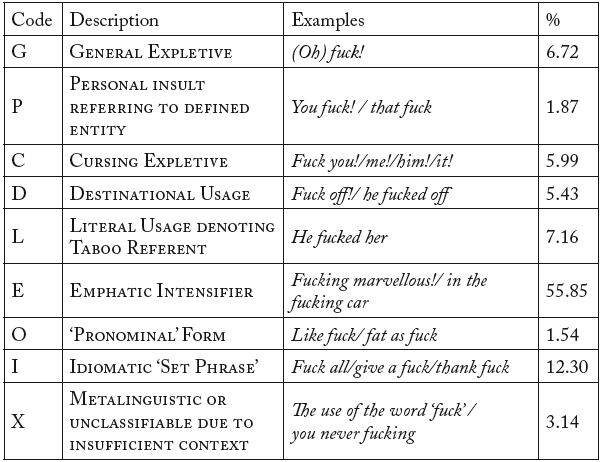

Figure 1

Main usages of the lexeme ‘fuck’ in the BNC

For many, the use of fuck and similar terms can be interpreted as a sure sign of impoliteness or of lack of respect. The picture, however, is not a neat one. Sexual language is at times a fashionable discourse which strengthens personal or group connection, and at times a moral scapegoat which justifies all social or political evils. There is a widespread tendency, however, to catalogue sexual language as impolite, which constantly demands apologies and justifications (Braun, 1999), for sex-related language possesses an intense emotional quality and can contaminate other words and areas of experience.

For McEnery and Xiao (2004), the fundamental usages of fuck in the British National Corpus are:

Table 1

Main usages of the lexeme “fuck” in the BNC (adapted from McEnery and Xiao, 2004)

This study is based on the British National Corpus,[12] a 100-million-word corpus of written and oral texts, where fuck is fundamentally used as an ‘emphatic intensifier’ (55.85% of occurrences)—i.e. its main aim is to add emotional values to the words or phrases it accompanies. Other significant values of the term are related to exclamative or figurative usages—as idiomatic ‘set phrase’ (12.30%), as a general expletive (5.72%), as cursing expletive (5.99), in a destinational usage (5.43%). What is most striking, perhaps, is that the denotative sexual meaning of fuck (‘to copulate’) is rarely used (7.16% of cases), as opposed to 92.84% of non-sexual usages. This seems to indicate an obvious process of de-semantization—and even of de-sensitization—of the lexeme fuck in English across settings and genres, and a marked preference for emotive and emphatic values. In spite of this difference, however, we cannot help perceiving a certain ‘sexualization’ of the communicative events in which the lexeme fuck is used. The shocking capacity of this term permeates the whole language and a certain sexual(ised) flavour is inescapable.

In fact, it may well be that the enormous emphatic potential (55.85%) of the term is mostly attributable to its sexual nature. If we encounter the word fuck or any of its morphological variants, we will give them a primarily sexual meaning, as it is a term which is socially sanctioned as ‘obscene’, vulgar or inappropriate in most contexts, and has been subject to legal censorship (see Rembar, 1968; or Sunderland, 1982 for a history of the obscenity trials D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928) went through in the US and UK)[13] or for social stigmatisation.[14] The English language has codified this social stigmatisation into the euphemism ‘four-letter word’ or even ‘the f-word’.

For this paper we have collected a corpus with 65 examples where the term fuck (and its morphological variants fucking, fucked and others) is used, and we have analyzed the commercial translations into Spanish and Catalan. All the morphological variants of fuck and the number of occurrences we obtained are as follows:

Fuck (v. & n.) |

28 |

Fucking |

17 |

Fuckwittage |

11 |

Fuckwit |

5 |

Fuck-up |

2 |

Fucked |

1 |

Fuckety |

1 |

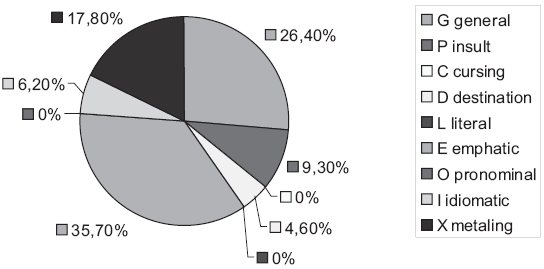

If we use the same categories proposed by McEnery and Xiao (2004), we have the diagram below, which shows statistics from BJ and BJER:

Table

Main usages of the lexeme ‘fuck’ in Bridget Jones’s Diary (1996) and Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason (1999)

Figure 2

Main usages of the lexeme ‘fuck’ in BJ and BJER

We are well aware that this paper offers a limited—though, we believe, significant—corpus. Sex-related language cannot—we believe—be measured along the same quantitative lines as other, more neutral linguistic items.

Our corpus confirms that the most widespread usage of fuck is that of emphatic intensifier, with a somewhat smaller 35.70% of all the examples collected. The most common pattern is attributive adjective fucking + noun, with a derogatory or insulting meaning (“A qualification of extreme contumely”, according to the O.E.D.):

Some of the examples, especially in BJER, resort to a playful repetition of the attribute adjective fucking, which is a basic characteristic of colloquial language:

7

‘That is why everything is such a fucking, fucking, fucking …’

BJER 688

‘… he still hasn’t fucking, fucking, fucking well rung’

BJER 729

‘Fucking fucking mini-cab …’

BJER 165Examples (1) to (9) evince one of the main traits of sex-related expletives: a combination of euphonic pleasure and ritual transgression. For some social groups, using blasphemies, insults or sex-related terms are, possibly, ancestral urges. The target of these terms is not so much individual persons (the exceptions being Bridget and Jerome, in examples (5) and (6)), but rather objects, facts or even unmentioned circumstances, which shows/confirms that sex-related emphatic intensifiers are basically about one’s emotions and not about external objects or subjects.

Phrases like ‘where the fuck’ or ‘what the fuck’ are routinely repeated, thus intensifying emotions like anger, annoyance or despair:

10

‘… where the fuck…?’

BJ 21511

‘What the fuck are you doing?’

BJ 22312

‘where the fuck are you off to?’

BJ 26913

‘Where the fuck is mini-cab?’, etc.

BJER 164Let us have a look at the translations we have used. How do they convey the emotional, euphonic or irrational overtones associated with fuck as an emphatic intensifier? Most of the examples in our corpus are usually translated, in Spanish and Catalan, as sex-related terms though with non-sexual meanings. The Spanish translation resorts somewhat mechanically to the attribute adjective jodido/a, which is defined by Seco et al. (1999) as a contemptuous or derogatory term referring to people or things.[15]

1a

‘está teniendo una jodida aventura’

BJ 1162a

‘jodido bastardo adúltero’

BJ 1163a

‘el jodido capó’

BJ 1164a

‘Absolutamente y jodidamente brillante’

BJ 2205a

‘La jodida Bridget’

BJER 276a

‘jodido Jerome, jodido, jodido Jerome’

BJER 1477a

‘es tan jodidamente, jodidamente, jodidamente …’

BJER 788a

‘Joder, joder, joder, no puedo creer que todavía no haya llamado’

BJER 829a

‘Jodido, jodido taxi …’

BJER 177The Catalan translation avoids a mechanical rendering of the term, and explores more natural options:

1b

‘Té una aventura, cony!’

BJ 1242b

‘ets un cony de malparit adúlter’

BJ 1243b

‘aquest cony de capó’

BJ 1254b

‘Absolutament genial, cony’

BJ 2345b

‘La Bridget dels collons’

BJER 256b

‘Jerome, ets un cabró, un cabró, Jerome’

BJER 1557b

‘tot plegat és una puta, puta, puta …’

BJER 828b

‘No puc creure que encara no m’hagi fet ni una puta, puta, puta trucada’

BJER 879b

‘Cony de minitaxi dels collons …’

BJER 187While the Spanish translations sound to us like a ready-made translation cliché, the ones in Catalan are much more natural and risky, and they present us with three of the key taboo terms in the language, the main building blocks of colloquial or vulgar texts, and which demand a great deal of tact when used in any context. The three words (cony, puta and collons) are strictly banned in many contexts, and are likely to add a high level of linguistic violence or social transgression. Besides, these are words which are profoundly sexist, especially offensive with regard to women and female sexuality. Words like cony [Eng. ‘cunt’] or puta [Eng. ‘whore’] give rise to an open series of phrases which emphasize negative traits associated with women and femininity, such as boredom, inadequacy, shamelessness, and so on.[16] The term collons [Eng. ‘testicles’], however, is projected metonymically into a series of expressions emphasizing the strength and bravery which are traditionally associated with masculinity.[17] Many everyday usages of sex-related language reveal a profoundly sexist attitude.

In the set phrases ‘where the fuck…?’ or ‘what the fuck…?’, the translations in our corpus offer nearly identical options:

10a

‘¿dónde coño …?’

BJ 22510b

‘¿on collons?’

BJ 23911a

‘¿Qué coño estás haciendo?’

BJ 22311b

‘¿Què cony fots?’

BJ 24812a

‘¿adónde coño vas?’

BJ 27712b

‘¿… on cony vas?’

BJ 29613a

‘¿Dónde coño está el taxi?’

BJER 17613b

‘¿On cony és el minitaxi?’

BJER 186A significant feature is the systematic (over)exploitation of feminine genitals (Sp. coño and Cat. cony) (see footnote 15), the only exception being (1b), where the idiomatic phrase ‘¿on collons?’ is preferred.

The abundant repetition of fuck as a general interjection in our corpus and particularly in BJER, is quite remarkable:

14

‘Oh fuck, oh fuck.’

BJ 19615

‘Oh my fuck, wind it up, wind it up!’

BJER 1616

‘Fuck, fuck, telephone again.’

BJER 3517

‘Oh fuck, oh fuck.’

BJER 8118

‘Oh fuck, where are keys?’

BJER 16519

‘Oh fuck, oh fuck. Oh fuck, oh fuck.’

BJER 169Surely this excessive repetition—if excessive means anything in language use—of an interjection deprives it of some of its values. It might reveal a certain de-sensitization, a sort of trendy linguistic game. The Spanish translations are again seized with the same drowsiness of the original, and the Spanish translator yields to the easiest temptation: the use of the verb joder (see footnote 14), a vulgar term widely used in colloquial conversations to express, basically, protest and surprise (Seco et al., 1999, p. 2735). The Catalan translator, again, explores other options:

14a

‘Oh joder, oh joder.’

BJ 20514b

‘Ai, cony.’

BJ 22015a

‘¡Oh joder, cortad, cortad!’

BJER 2715b

‘Ai collons, mateu-ho, mateu-ho!’

BJER 2616a

‘Joder, joder, otra vez el teléfono.’

BJER 4516b

‘Merda, merda, un altre cop el telèfon.”

BJER 4617a

‘Oh joder, oh joder.’

BJER 9117b

‘Merda, merda, merda.’

BJER 9618a

‘Joder, ¿dónde están las llaves?’

BJER 17718b

‘Ai, merda, ¿on tinc les claus?’

BJER 18719a

‘Oh joder, oh joder. Oh joder, oh joder.’

BJER 18119b

‘Ai, merda, ai, merda. Ai, merda, ai, merda.’

BJER 192Besides the use of cony and collons (see footnotes 15 and 16), there is a preference—typically Mediterranean—for the term merda [Eng. ‘shit’], which has a long tradition in the popular culture of Catalan-speaking countries.[18] Speakers of Catalan themselves—maybe due to the fact that they belong to a minority culture, or maybe as a prejudice—consider that “[w]e Valencians are much more foul-mouthed [than Spanish-speaking people],” and find a certain pride in coprology and scatology (Santaemilia, 2008, p. 24).

The metalinguistic usage is present in ten examples (17.80% of the corpus) found in Helen Fielding’s novels, particularly in Bridget Jones (1996), a novel which inaugurated a clearly recognisable literary genre for women, and where we collected nine examples. In the first chapters of BJ there is a conscious effort to coin a trendy, attractive and unprejudiced term to identify an independent, cosmopolitan female attitude to life. BJ’s author was well aware that she was creating a product for women, a serious and systematic attempt to depict new gender and sexual relations. In order to achieve this, a new term was needed to account for the emotion vs. sex struggle or—in more general terms—for the men vs. women struggle. This linguistic experiment revolves around the words fuckwit[19] and fuckwittage. In the first chapter of BJ we are given almost a manifesto of what has come to be known as chick lit:

20

‘We women are only vulnerable because we are a pioneer generation daring to refuse to compromise in love and relying on our own economic power. In twenty years’ time men won’t even dare start with fuckwittage because we will just laugh in their faces’, bellowed Sharon.

BJ 21It’s a newly-coined term which poses a direct problem to translators, as it strives to reflect the complexity of a type of literature which tries to be fresh and ingenious, free of gender bias, and offering a site for women’s self-affirmation.

21

A siren blared in my head and a huge neon sign started flashing with Sharon’s head in the middle going, ‘fuckwittage, fuckwittage’.

I stood stock still on the pavement, glowering up at him.

‘What’s the matter?’ he said, looking amused.

‘I’m fed up with you’, I said furiously. ‘I told you quite specifically the first time you tried to undo my skirt that I am not into emotional fuckwittage. It was very bad to carry on flirting, sleep with me then not even follow it up with a phone call, and try to pretend the whole thing never happened. Did you just ask me to Prague to make sure you could still sleep with me if you wanted to as if we were on some sort of ladder?’

‘A ladder, Bridge?’ said Daniel. ‘What sort of ladder?’

‘Shut up,’ I bristled crossly. ‘It’s all chop-change with you. Either go out with me and treat me nicely, or leave me alone. As I say, I am not interested in fuckwittage’.

BJ 76The options adopted by both translators are disparate though consistent throughout the texts: while fuckwittage is translated as ‘sexo sin compromiso’ [Eng. ‘non-committed sex’] in Spanish, in Catalan we are left with the incomprehensible ‘subnormalitat’ [Eng. ‘mental handicap’]. We cannot but wonder at the Catalan translation, as it makes no sense and, especially, distorts Helen Fielding’s metalinguistic effort. By contrast, the Spanish translation is a coherently descriptive rendering, though somewhat feeble, as it avoids altogether a marked term like fuck.

Helen Fielding coins a new term (fuckwittage) which is central to repositioning feminine agency into a contemporary discourse of love and sex but, through the use of self-parody, manages to counter the initial effects and we, as readers, are landed with a sense of ambiguity, of oddness, of self-mockery. Interestingly, Bridget Jones’s Diary incorporates the basic elements of a self-parody:

22

Had it not been for Sharon and the fuckwittage and the fact I’d just drunk the best part of the bottle of wine, I think I would have sunk powerless into his arms. As it was, I leapt to my feet, pulling up my skirt.

‘That is just such crap,’ I slurred. ‘How dare you be so fraudulently flirtatious, cowardly and dysfunctional? I am not interested in emotional fuckwittage. Goodbye’.

It was great. You should have seen his face. But now I am home and I am sunk into gloom. I may have been right, but my reward, I know, will be to end up all alone, half-eaten by an Alsatian.

BJ 33It may well be that a fundamental trait of the new, independent woman advocated by BJ is her verbal creativity—a woman who is able to pun on her own feelings and passions, and who transforms sex (a passion which takes up every minute of her conversations) into a verbal artifice.

As an extension of the metalinguistic effort in BJ and BJER, we found several examples in which fuckwit is employed as a personal insult, along with one example with fuck-up:

23

‘misogynists, megalomaniacs, chauvinists, emotional fuckwits or freeloaders, perverts’.

BJ 224

‘Tell him to bugger off from me. Emotional fuckwit.’

BJ 6825

‘The one time someone seems a nice sensible person such as approved of by mother and not married, mad, alcoholic or fuckwit, they turn out to be gay bestial pervert.’

BJER 6726

‘ … exactly the same but feeling even more of a fuck up than last time.’

BJER 7227

‘If grounds are deemed unreasonable, then you have to declare yourself a Fuckwit.’

BJER 198Fuckwittage is a negative concept, mainly used to challenge men’s attitude towards love and sexual relations, which is stereotypically considered as sexually aggressive and devoid of emotional commitment. Fuckwit is, in essence, a ‘feminine’ term of abuse addressed at men.

As to the translation of fuckwit, a peculiar phenomenon can be observed. In the passages belonging to BJ, the Spanish rendering is consistent with that of fuckwittage:

23a

‘misóginos, megalómanos, chovinistas, sexistas, gorrones emocionales, pervertidos.’

BJ 924a

‘Mándalo a la mierda. Es un practicante de sexo sin compromiso emocional.’

BJ 74But in the passages from BJER, the translator seems to have forgotten the options adopted in the first book, and there is a surprising twist to a term completely unrelated to the metalinguistic effort present in examples (20), (21) and (22):

25a

‘… no está casado ni está loco, ni es alcohólico ni gilipollas …’

BJER 7726a

‘ … sintiéndote incluso más jodida que la última vez.’

BJER 8227a

‘… entonces tienes que declararte un gilipollas.’

BJER 211We cannot understand the sudden change in register. ‘Gilipollas’ [Eng. ‘jerk’] would be a much weaker rendering than fuckwit, where all wordplay is certainly lost. The metalinguistic dimension, which practically occupied the whole of BJ, now seems to be simply abandoned in the Spanish version. The Catalan rendering, though incomprehensible to us, remains the same:

23b

‘misògins, megalòmans, xovinistes, deficients o gorrers emocionals, pervertits.’

BJ 1324b

‘Digue-li que el donin pel cul de part meva. És un subnormal emocional.’

BJ 8025b

‘… no és alcohòlic ni subnormal emocional, …’

BJER 8126b

‘… amb la sensació de ser encara molt més fracasada que abans’

BJER 8727b

‘… llavors l’individu s’haurà de declarar Subnormal Emocional’

BJER 222Both McEnery and Xiao’s (2004) destinational (4.60% of examples) and idiomatic ‘set phrase’ (6.20%) usages have an idiomatic character:

28

‘Listen, Bridge, I’m really sorry, I’ve fucked up’

BJ 7529

‘Oh, go fuck yourselves.’

BJ 8430

‘… every week I had to try out a different profession then fuck it up in an outfit’

BJER 3231

‘‘Fuck off, everyone, this is my personal space’’

BJER 4432

‘‘Oh fuck off, Jeremy’’

BJER 211The translations are symptomatic of the two cultures, Spanish and Catalan:

28a

‘Escucha, Bridge, de verdad que lo siento, la he jodido’

BJ 8228b

‘Escolta, Bridge, em sap molt de greu, l’he cagada.’

BJ 8929a

‘Oh, que os jodan’

BJ 9229b

‘Aneu-vos-en a la merda!’

BJ 9830a

‘… tenía que probar cada semana una profesión diferente y joderla, fastidiarla vestida con el uniforme correspondiente a cada profesión’

BJE 4230b

‘… volien que provés de fer cada setmana una professió diferent perquè la cagués disfressada de mil maneres diferents’

BJER 4231a

‘‘Jodeos todos, éste es mi espacio personal’’

BJER 5431b

‘‘Feu-vos fotre, tot plegats, això és el meu espai personal’’

BJER 5632a

‘‘Oh Jeremy, que te jodan’’

BJER 22332b

‘‘Ai, vés-te’n a la merda, Jeremy’’

BJER 235The Spanish translator resorts, more or less mechanically, to phrases with joder (see footnote 14), whereas the Catalan translator prefers expressions with merda (see footnote 17), which again reinforces the daily presence of scatology in the Catalan culture.

We have found no instance of fuck as a cursing expletive, ‘pronominal’ form or with a literal meaning. This last usage deserves a comment—there is no single example, in BJ or BJER, of the verb fuck with a literal meaning (“to copulate”, O.E.D.); the verbs shag and sleep are used instead. Curiously, in spite of the fact that BJ and BJER revolve incessantly around love, new sexual relations and a new role for women, there are very few examples where actual sexual relations are explicitly mentioned. All is indirection, figurative meanings, idiomatic expressions. All in all, however, and this is the paradox, Helen Fielding’s novels smell of a hyper-sexualized narrative.

4. By Way of Conclusion(s)

What are the dangers of self-censorship(s)? Firstly, the main danger lies probably in its own invisibility. Self-censorship is usually a muted phenomenon, highly individual, highly unpredictable, sometimes with no overt logic. In the case of SL, (unconfessed) feelings of uneasiness, embarrassment or disgust may be apt explanations.

The Spanish translations of BJ and BJER deal with the lexeme fuck in a somewhat mechanical way, as if translating sexually-loaded terms were a mere routine. When sex is reduced to a lexical or even grammatical category, with stable translations which ignore the specific pragmatic contexts and co-texts, its expressive potential and level of transgression diminishes importantly. Translating sex-related terms cannot be a mechanical exercise in standard equivalences. The translations into Catalan reproduce more fully the emotional and idiomatic overtones which sex-related language has in Helen Fielding’s novels. Fielding does not use sex (in this case, the word fuck) in its literal sense—there is no single reference to fuck meaning ‘to copulate’—but rather as a semantic field from which the author derives important narrative and emotional advantages: we are left with a fresh and informal story, far removed from a tedious prudish tale, where a woman is in command of the marginalised languages which had hitherto been a preserve of male characters. But both translations into Spanish and into Catalan trivialize a highly sensitive resource such as sex-related language. Excessive repetition and a mechanical rendering of equivalents may help de-semantize and de-sensitize the use of sex-related language in literature.

However minor self-censorships are, and however unnoticed they may go, it is worth investigating the manipulatory mechanisms projected onto source texts in order to alter their meaning or their contents, pervert their identity or divert their ideological messages. Self-censorship does not usually threaten the existence of the whole source text, but constitutes a subtler and less aggressive threat: the temptation of a rewriting based on moral, religious or purely personal reasons. Through translation, sex-related references may be downgraded, sweetened or turned into a mechanical device (Toledano, 2003, Santaemilia, 2005b); religious satire ignored (Keyes, 2003); or blasphemies merely eliminated (Salinger, 1983; Schmitz, 1998; Karjalainen, 2002). Sexual innuendo, in particular, becomes diffused, shaded, tamed or—in a word—more palatable for the editorial machinery.

While in the 21st century Western societies, translation is not threatened by traditional state censorships, subtler constraints are in operation. Publishing houses, media groups or administrations exercise a sometimes not-so-subtle ideological censorship. Political, religious, ideological or economic interests are among today’s most important sources of self-censorship(s), in some cases fostering fierce, fundamentalist attitude towards all type of dissidence and of the freedom of expresssion (see footnote 3). Older methods of censorship have been replaced by less explicit ones, which aim at whole rewriting of reality, whether in political, religious, ideological or economic terms.

The translation of sex-related language is prone to being censored by several pressure groups; also translators themselves are likely to transform sexually-loaded terms into merely mechanical renderings. Translating sex-related language is not simply a lexical matter, but rather a pragmatic and emotive challenge.

While explicit state censorship can be traced, the range of self-censorship phenomena cannot. In many cases, self-censorship can pass off as the translator’s own ethics, whether out of religious beliefs, an ideological position or even a personal stylistic project. Although we live, at least in the Western world, in a period with no official censorship, we must be as generous towards the translator’s right to objection on political, religious, moral or even stylistic grounds, as we must be on the alert for the (in)significant threats of manipulation coming from a variety of pressure groups.

Sexual language is a privileged area to study the cultures we translate into—it is a site where each culture places its moral or ethical limits, where we encounter its taboos and its ethical dilemmas. Historically, sex-related language has been a highly sensitive area; if today, in Western countries at least, we cannot defend any form of public censorship, what we cannot prevent (nor probably should we) is a certain degree of self-censorship, along the lines of an individual ethics and attitude towards religion, sex(uality), notions of (im)politeness or (in)decency, etc. Translating is always a struggle to reach a compromise between one’s ethics and society’s multiple constraints—and nowhere can we see this more clearly than in the rewriting(s) of sex-related language.

Parties annexes

Author

José Santaemiliais Associate Professor of English Language and Linguistics at the University of Valencia, as well as a legal and literary translator. His main research interests are gender and language, sexual language and legal translation (English-Spanish). He has edited several volumes on gender and translation (Género, lenguaje y traducción, Valencia University Press, 2003; Gender, Sex and Translation: The Manipulation of Identities, St. Jerome, Manchester, 2005) and (with José Pruñonosa) is author of the first critical edition and translation of Fanny Hill into Spanish (Editorial Cátedra, 2000).

Notes

-

[1]

I wish to thank the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación for their support in this research, in particular for the research project ‘Género y (des)igualdad sexual en las sociedades española y británica contemporáneas: Documentación y análisis discursivo de textos socio-ideológicos’ (FFI2008-04534/FILO).

-

[2]

When dealing with the linguistic effects of censorship and self-censorship, Allan and Burridge draw a distinction between the censorship of language—which refers to “institutional suppressions of language by powerful governing classes, supposedly acting for the common good by preserving stability and/or moral fibre in the nation”—and the censoring of language—which “encompasses both the institutionalized acts of the powerful and those of ordinary individuals” (2006, p. 24). The second is a broader phenomenon which includes both censorship and self-censorship.

-

[3]

The Spanish daily El Mundo or the radio station COPE are today paradigms of partisan and exclusive mass media, which blindly follow the dictates of extreme right-wing ideological positions.

-

[4]

The Spanish translation of J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (1951)—El guardián entre el centeno (Madrid, Alianza, 1983 [1978])—offers abundant examples of omissions when it comes to translating blasphemies like Chrissake, goddam, damn or hell. An example will be provided below.

-

[5]

In the Spanish translation of Marian Keyes’ Angels (2002), a whole passage where Catholic Church rituals are made fun of is completely eliminated. An example will be provided later.

-

[6]

For Toledano (2003, p. 74) “obscenas son las actuaciones humanas, de naturaleza verbal o visual, llevadas a cabo en espacios públicos y percibidas como una ofensa por el receptor en tanto en cuanto suponen la violación y transgresión de unas normas—de naturaleza moral—cuya observancia se considera necesaria para asegurar el respeto de los principios ideológicos de una sociedad.”

-

[7]

See Rabadán, 2000, for a comprehensive research project on state censorship under Franco’s dictatorial regime in Spain, 1939-1975, or Vega, 2004, for a description of the hardships publishers and translators went through during this period.

-

[8]

See Toledano (2003) or Santaemilia (2005b) for some examples in Spain, just when the Francoist regime had ended.

-

[9]

See Cleland (2000, 2001, 2006) as examples of recent repritings and/or editions.

-

[10]

Several reputable publishers in Spain offer collections of erotic literature: examples are the Editorial Tusquets (‘Colección La Sonrisa Vertical’) or the Editorial Fapa (‘Colección Relatos Ardientes’).

-

[11]

The debate on chick lit is interesting in itself, as it points to two main differing interpretations: (i) the fact that young women’s experiences—basically, love and sex(uality)—are the centre of a ‘new’ literary and commercial genre; and (ii) the fact that the term chick lit is coined as a slang term, denoting a by-product, a cliché.

-

[12]

See BNC webpage http://www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk.

-

[13]

Not surprisingly, at the 1955 trial at the Old Bailey “the prosecutor produced as significant for the statistic that the novel container: 30 ‘fucks’ or ‘fuckings’, 14 ‘cunts’, 13 ‘balls’, 6 each of ‘shit’ and ‘arse’, 4 ‘cocks’ and 3 ‘piss’” (Sunderland, 1982, p. 15).

-

[14]

Although sex-related profanity is becoming commonplace in television and advertising, Bob Geldof, the famous pop singer and pro-human rights activist, an icon of British popular culture, was heavily reprimanded by the Sunday Express for using the ‘f-word’ in a TV programme in 2003. See Santaemilia (2005a, 2006).

-

[15]

Seco et al. (1999, p. 2736) define jodido/a as: “Se emplea para calificar despreciativamente a la persona o cosa expresada en el nombre al que se refiere. A veces con intención humorística y afectiva.” Jodido/a is the past participle of the verb joder [Eng. ‘to copulate’], a taboo term which, for some people, is rapidly losing its offensive potential, as it is universally used in phrases like a joderse tocan [denoting passive acceptance], joderla [Eng. ‘screw things up’] or ¡hay que joderse! [indicating surprise, indignation, etc.]. Sanmartín (2001) maintains that a verb like joder is used dysphemistically as an interjection indicating the speaker’s annoyance or surprise, and that it emphasizes the interlocutors’ argumentative disagreement.

-

[16]

There are several idiomatic phrases with Cat. cony and Sp. coño, as can be seen in Sp. el quinto coño [Eng. ‘a faraway place’], Sp. coña and Cat. conya [Eng. ‘joke’], Sp. coñazo [Eng. ‘annoying person or thing’], or quin cony de … [“Qualificació despectiva donada a una persona o una cosa”, DLC], etc. (Seco et al. 1999, p. 1245). Phrases with puta are Cat. and Sp. mala puta [Eng. ‘a bad, foxy person’], Cat. passar-les putes and Sp. pasarlas putas [Eng. ‘go through a terrible situation’], Cat. and Sp. putada [Eng. ‘dirty trick’] or Cat. la puta que et va parir o Sp. la puta que te parió [lit. ‘the whore that bore you’, but pragmatically denoting the speaker’s annoyance at something or someone] (Seco et al., 1999, p. 3758; DCVB online).

-

[17]

Examples are phrases like Cat. de collons or Sp. de cojones [Eng. ‘very good’], Cat. passar(li) pels collons o Sp. salir(le) de los cojones [figurative expression denoting bravery and unlimited freedom to do something], and Cat. tenir collons or Sp. tener cojones [Eng. ‘being extremely brave’] (see Seco et al., 1999, pp. 1101-1102; and DLC online).

-

[18]

Colloquial expressions are Cat. ves-te’n a la merda o Sp. vete a la mierda [indicates strong rejection], Cat. haver trepitjat merda [Eng. ‘being extremely unlucky’] or Sp. cubrirse de mierda [Eng. ‘make a fool of oneself’] (see Seco et al., 1999, pp. 3066-3067; DLC and DCVB online). No figurative expression with merda or mierda has sexual connotations. Though both Catalan and Spanish use plenty of expressions with merda/mierda, one has the impression that Catalan resorts to them more often.

-

[19]

Fuckwit appears in the O.E.D. as “[a] stupid or contemptible person; an idiot.”

References

- CLELAND, John (2000). Fanny Hill : Memorias de una mujer de placer. Eds. and trans. José Santaemilia and José Pruñonosa. Madrid, Cátedra.

- CLELAND, John (2001). Fanny Hill : Memorias de una cortesana. Trans. Enrique Martínez Fariñas. Barcelona, Tusquets.

- CLELAND, John (2006). Fanny Hill : Memorias de una mujer de placer. Introd. by Graciela Guido. Trans. by TMT. Madrid, Edimat Libros.

- FIELDING, Helen (1996). Bridget Jones’s Diary. London, Corgi Books.

- FIELDING, Helen (1998). El diari de Bridget Jones. Trans. Ernest Riera. Barcelona, Edicions 62.

- FIELDING, Helen (1999). El diario de Bridget Jones. Trans. Néstor Busquets. Barcelona, Plaza & Janés.

- FIELDING, Helen (1999). Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason. London, Picador.

- FIELDING, Helen (2001). Bridget Jones perd el seny. Trans. Ernest Riera. Barcelona, Edicions 62.

- FIELDING, Helen (2005). Bridget Jones : Sobreviviré. Trans. Néstor Busquets. Barcelona, De Bolsillo.

- KEYES, Marian (2002). Angels. Harmondsworth, Penguin Books.

- KEYES, Marian (2003). Maggie ve la luz. Trans. Matuca Fernández de Villavicencio. Barcelona, DeBolsillo.

- SALINGER, J.D. (1983 [1951]). The Catcher in the Rye. Penguin, Harmondsworth.

- SALINGER, J.D. (1983 [1978]). El guardián entre el centeno. Trans. Carmen Criado. Madrid, Alianza Editorial.

- ALLAN, Keith and Kate BURRIDGE (2006). Forbidden Words: Taboo and the Censoring of Language. Cambridge, C.U.P.

- BEAUVOIR, Simone de (1952). The Second Sex. Trans. H.M. Parshley. New York, Bantam.

- BOU, Patricia and Barry PENNOCK (1992). “Método evaluativo de una traducción : aplicación a Wilt de Tom Sharpe.” Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada, 8, pp. 177-185.

- BRAUN, Virginia (1999). “Breaking a Taboo? Talking (and Laughing) about the Vagina.” Feminism and Psychology, 9, 3, pp. 367-372.

- DCVB (Diccionari Català-Valencià-Balear. Accessible online at: http://www.dcvb.iecat.net/

- DLC (Diccionari de la Llengua Catalana). Accessible online at: http://www.grec.net/home/cel/dicc.htm

- DRAE (Diccionario de la Real Academia Española de la Lengua), 22nd edition. Accessible online at: http://www.buscon.rae.es/draeI/

- GALLEGO ROCA, Miguel (2004). “De las vanguardias a la Guerra Civil.” In F. Lafarga and L. Pegenaute, eds., Historia de la traducción en España. Salamanca, Editorial Ambos Mundos, pp. 479-526.

- JESPERSEN, Otto (1950 [1922]). “The Woman.” In Language. Its Nature, Development and Origin. London, George Allen & Unwin.

- KARJALAINEN, Markus (2002). Where Have All the Swearwords Gone? An Analysis of the Loss of Swearwords in Two Swedish Translations of J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye. Unpublished ‘Pro Gradu thesis’. University of Helsinki, Finland.

- KREBS, Katja (2007). “Anticipating Blue Lines: Translational Choices as Sites of (Self)-Censorship: Translating for the British Stage under the Lord Chamberlain.” In F. Billiani, ed., Modes of Censorship and Translation: National Contexts and Diverse Media. Manchester, St. Jerome, pp. 167-186.

- LAFARGA, Francisco and Luis PEGENAUTE, eds. (2004). Historia de la traducción en España. Salamanca, Editorial Ambos Mundos.

- LAKOFF, Robin (1975). Language and Woman’s Place. New York, Harper Torch Books.

- LEFEVERE, André (1992). Translation, Rewriting, and the Manipulation of Literary Fame. London and New York, Routledge.

- LEÓN, Víctor (1984). Diccionario de argot español y lenguaje popular. Madrid, Alianza Editorial. 4th ed.

- McENERY, Tom and Zhonghua XIAO (2004). “Swearing in Modern British English: The Case of Fuck in the BNC.” Language and Literature, 13, 3, pp. 235-268.

- MERINO, Raquel and Rosa RABADÁN (2002). “Censored Translations in Franco’s Spain: The TRACE Project–Theatre and Fiction (English-Spanish).” TTR, 15, 2, pp. 125-152.

- O.E.D. (Oxford English Dictionary). Accessible online at: http://www.oed.com

- ORTEGA Y GASSET, José (1992 [1937]). “The Misery and the Splendor of Translation.” Trans. Elizabeth Gamble Miller. In J. Biguenet and R. Schulte, eds., Theories of Translation: An Anthology of Essays from Dryden to Derrida. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, pp. 93-112.

- RABADÁN, Rosa, ed. (2000). Traducción y censura inglés-español: 1939-1985. Estudio preliminar. León, Universidad de León.

- REMBAR, Charles (1968). The End of Obscenity. New York, Random House.

- SANMARTÍN, Julia (2001). “El cuerpo, la sexualidad y sus imágenes: una aproximación lingüística.” In J.V. Aliaga et al., eds., Miradas sobre la sexualidad en el arte y la literatura del siglo XX en Francia y España. Valencia, Universitat de València, pp. 253-270.

- SANTAEMILIA, José (2005a). “Researching the Language of Sex: Gender, Discourse and (Im)Politeness.” In J. Santaemilia, ed., The Language of Sex: Saying & Not Saying. Valencia, Universitat de València, pp. 3-22.

- SANTAEMILIA, José (2005b). “The Translation of Sex, The Sex of Translation: Fanny Hill in Spanish.” In J. Santaemilia, ed., Gender, Sex and Translation: The Manipulation of Identities. Manchester, St. Jerome, pp. 117-136.

- SANTAEMILIA, José (2006). “Researching Sexual Language: Gender, (Im)Politeness and Discursive Construction.” In P. Bou, ed., Ways into Discourse. Granada, Editorial Comares, pp. 93-115.

- SANTAEMILIA, José (2008). “Gender, Sex, and Language in Valencia: Attitudes toward Sex-Related Language among Spanish and Catalan Speakers.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 190, pp. 5-26.

- SCHMITZ, John Robert (1998). “Suppression of Reference to Sex and Body Functions in the Brazilian and Portuguese Translations of J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye.” Meta, 43, 2, pp. 242-253.

- SECO, Manuel et al. (1999). Diccionario del español actual. Madrid, Aguilar. 2 vols.

- SIMMS, Karl, ed. (1997). Translating Sensitive Texts: Linguistic Aspects. Amsterdam/ Atlanta, Rodopi.

- SIMON, Sherry (1996). Gender in Translation. London and New York, Routledge.

- SUNDERLAND, John (1982). Offensive Literature: Decensorship in Britain, 1960-1982. London, Junction Books.

- TOLEDANO, Carmen (2003). La traducción de la obscenidad. Santa Cruz de Tenerife, La Página Ediciones.

- VEGA, Miguel Ángel (2004). “De la Guerra Civil al pasado inmediato.” In F. Lafarga and L. Pegenaute, eds., Historia de la traducción en España. Salamanca, Editorial Ambos Mundos, pp. 527-578.

Primary Sources

Secondary Sources

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Main usages of the lexeme ‘fuck’ in the BNC

Figure 2

Main usages of the lexeme ‘fuck’ in BJ and BJER

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Main usages of the lexeme “fuck” in the BNC (adapted from McEnery and Xiao, 2004)

Table

Main usages of the lexeme ‘fuck’ in Bridget Jones’s Diary (1996) and Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason (1999)

10.7202/004046ar

10.7202/004046ar