Résumés

Abstract

This paper explores how Canada’s full commitment to the Inter-American Human Rights System (IAS) could provide a further recourse for monitoring, protecting and promoting Indigenous rights in Canada. Presenting the Americas as a united continent, it emphasizes how reconceptualising what it means to “be American” can help Canadians think about their connection, comprehension and acceptance of this regional system. This paper examines the Canadian government’s historical disinterest in the IAS and establishes this as the primary reason for its current lack of commitment. It argues that Canada’s ratification of the American Convention on Human Rights and recognition of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights jurisdiction would positively impact the rights of Indigenous peoples living within its borders. It concludes by highlighting a Canadian initiative that is working towards making Canada a better player in the IAS and contends that the Canadian government should follow their lead.

Résumé

Cet article explore comment le plein engagement du Canada envers le Système interaméricain des droits humains (SIDH) pourrait fournir un recours supplémentaire pour surveiller, protéger et promouvoir les droits des peuples autochtones au Canada. Présentant les Amériques comme un continent uni, il met l’accent sur la façon dont la reconceptualisation de ce que signifie « être Américain » peut aider les Canadiens à réfléchir à leur lien, à leur compréhension et à leur acceptation de ce système régional. Cet article examine le désintérêt historique du gouvernement canadien pour le SIDH et établit qu’il s’agit de la principale raison de son manque d’engagement actuel. Il soutient que la ratification, par le Canada, de la Convention américaine relative aux droits de l’Homme et la reconnaissance de la compétence de la Cour interaméricaine des droits de l’Homme auraient un impact positif sur les droits des peuples autochtones vivant à l’intérieur de ses frontières. Il conclut en soulignant une initiative canadienne qui vise à faire du Canada un meilleur joueur dans le SIDH et soutient que le gouvernement canadien devrait suivre leur direction.

Resumen

Este artículo explora cómo el compromiso total de Canadá con el Sistema Interamericano de Derechos Humanos (SIDH) podría proporcionar un recurso adicional para monitorear, proteger y promover los derechos de los pueblos indígenas en Canadá. Al presentar las Américas como un continente unido, enfatiza cómo reconceptualizar lo que significa “ser americano” puede ayudar a los canadienses a pensar sobre su conexión, comprensión y aceptación de este sistema regional. Este artículo examina el desinterés histórico del gobierno canadiense en el SIDH y plantea este último como la razón principal de su actual falta de compromiso. Argumenta que la ratificación por Canadá de la Convención Americana sobre Derechos Humanos, así como el reconocimiento de la jurisdicción de la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos, tendrían un impacto positivo en los derechos de los pueblos indígenas que viven dentro de sus fronteras. Concluye destacando una iniciativa canadiense que está buscando hacer de Canadá un mejor protagonista en el SIDH, y sostiene que el gobierno canadiense debería seguir su dirección.

Corps de l’article

What does it mean to be “American”? In English, this word often refers to the United States (US), rather than to the continent whose name it derives from. In Spanish, the word takes on a different meaning. While some associate it with being born in the US, others view it as all-encompassing: being “American” is a commitment to the history that shaped this continent. Being “American” ties them to the larger global community. Being “American” is an expression of solidarity. Being “American” implies belonging to a shared hemispheric identity.

Some believe the continent needs no label - the term “American” loses its legitimacy in an increasingly globalized world. Others do not associate with the term at all. In a continent that was invaded, and not discovered, it is difficult to imagine how any institution could reconcile the interests of the colonizers with those of the colonized, especially when it comes to questions of human rights. How could a single system be willing or competent enough to deal with the various legal systems and traditions that make up the Americas?[1] However, in the context of human rights monitoring, such a system does exist. The American Convention on Human Rights (Convention or ACHR)[2] exemplifies the historically-rooted desire to create an inclusive legal framework for the Americas. This is illustrated in its Preamble which reaffirms the “intention to consolidate in this hemisphere […] a system based on respect for the essential rights of man.”[3] The Inter-American System (IAS) emerged from a shared commitment to monitor, promote and protect human rights among the peoples of the Americas.[4] This is accomplished through the region’s two principal human rights entities: the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (Commission or IACHR) and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (Court or IACtHR).[5]

Although Canada is often globally perceived as a champion of human rights, it is not immune to human rights violations, especially those experienced by Indigenous peoples within its own borders. Despite an existing legal framework and policy initiatives that protect of Indigenous communities, there is a wide gap in well-being between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada.[6] Troubling socio-economic conditions, education barriers, inadequate housing, lack of access to health services, limited justice and safety, and intrusions on Indigenous land rights are all examples of how Indigenous peoples’ rights are not respected or guaranteed in Canada. The story of Indigenous peoples in Canada resembles those of their Latin American counterparts: they share similar colonial histories of dispossession, exploitation and oppression.

Indigenous communities in Latin America are increasingly relying on international law to enforce their human rights, especially when there is a lack of political will and/or widespread distrust in domestic alternatives.[7] Many groups have turned to the IAS as a forum to enforce their rights.[8] Could Indigenous communities in Canada do the same? Indigenous groups in Canada know about the Commission. For example, the Commission held a hearing on the “The Situation of Aboriginal Women and Girls in Canada” at the request of organizations such as the Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) and the Canadian Feminist Alliance for International Action (FAFIA).[9] However, Indigenous groups’ mobilization is limited by the fact that Canada has not signed the Convention or recognized the jurisdiction of the Court.[10]

This paper argues that Indigenous peoples in Canada can benefit from Canada’s ratification of the Convention and recognition of the jurisdiction of the Court. Ratification would allow for the country’s full commitment to the IAS and provide a further recourse for monitoring, protecting and promoting Indigenous rights in Canada.

This paper is divided into four sections. Section I presents the Americas as a united continent and illustrates how this understanding can help Canadians think about their connection to and comprehension and acceptance of the IAS. Section II examines Canada’s historical relationship with the IAS. It begins by detailing Canada’s connection to the IAS before and after 1990, which marks the year Canada joined the Organization of American States (OAS). It then explains the functioning of the IAS’ two principal human rights bodies. Section III dissects the core question asked in this paper and reflects on the impact of Canada’s full commitment to the IAS on Indigenous peoples within its borders. The paper concludes by highlighting a Canadian initiative that is working towards making Canada “a better player” in the IAS: the Université du Québec à Montréal’s (UQAM) “S’ouvrir aux Amériques” project (SOAA).[11] Ultimately, Canada has this optional legal avenue to supplement internal Indigenous justice.[12] This paper demonstrates why it should be used.

I. Somos Americanos?

In Spanish, “Somos Americanos” means “we are all American.” In order to better understand the impact of Canada’s adherence to the IAS, it is crucial to first examine what it means to be “American.” This section highlights the history that underlines this question and discuss how communities in Canada, as “Americans”, can create linkages between their identities and the regional system.

The idea of a united continent can be traced back to 1826 when Simón Bolívar convened the Congress of Panama, inspired by his vision of uniting the states of the Western hemisphere.[13] The struggle for independence from European colonial rule in several Latin American states, combined with similar struggles for independence in the US, gave rise to Pan-Americanism, a movement that calls for greater cooperation between America’s nations.[14]

Carol Hess describes Pan-Americanism as a “congeries of economic, political and cultural objectives that first peaked in the late nineteenth century and [that is] based on the premise that the Americas were bound by geography and common interests.”[15] In the US, this idea was first expressed by Thomas Jefferson when, in a famous letter to Alexander von Humboldt, he stated that “America has a hemisphere of its own.”[16] This idea quickly took political form. In 1823, the country’s fifth President, James Monroe, introduced the “Monroe Doctrine” — a key US foreign policy which opposed European control in the Americas.[17] While there are many more parts to the Pan-American story that could be discussed, this paper focuses only on how this concept has been used as an underlying framework for the IAS.[18]

Pan-Americanism served as a symbol of political resistance for independence from colonial powers, but it was paradoxically also viewed as a symbol of imperialism. For Arthur P. Whitaker in 1954:

the idea of the congruity of the several parts of America was one which, until the Europeans invented it and propagated it with their maps, had never occurred to anyone in all the agglomerations of Indigenous societies sprinkled over America from Alaska to the Tierra del Fuego. To this day the surviving remnants of those societies have never accepted the idea; to them, Pan Americanism is gibberish.[19]

Whitaker advances a valid critique. Pan-Americanism was a way for those who came to the “New World” to finally dissociate themselves from being European. It was an opportunity for those living in the “New World” to claim the continent as their own. However, this was accomplished at the expense of Indigenous peoples already living on the continent, through dispossession, exploitation and oppression. For this reason, many Indigenous peoples may not consider themselves “American” or citizens of the countries where their territories are located today.[20] This is definitely the case in Canada, where most of its cities are located on traditional and unceded Indigenous territories.[21]

However, it is possible to reconceptualise what it means to be a citizen living on the territory that makes up this continent. Jimmy Ung, who travelled from Montreal to Ushuaia by motorcycle redefined Pan-Americanism as a “civil movement”, a sense of “unity” between citizens of the Americas, which implies first and foremost solidarity, a cultural union, rather than a political one.[22] However, the idea of a cultural union does imply acknowledging the existence of cultural, social, political and legal diversities on the continent. Canada’s participation in the IAS would allow for communities within its borders to be exposed to and learn from other communities. This exposure would help different communities create the unity which would surpass traditional limitations of Pan-Americanism and create the foundation for Ung’s interpretation of the term. Ultimately, even if one does not call oneself “American”, Canada’s participation would provide a forum for this unity to be initiated, not only to redress one’s own past, present and future injustices, but to see those shared injustices redressed across the continent.

II. Canada’s Relationship to the Inter-American System

Before discussing how Canada’s full participation in the IAS could advance Indigenous rights in Canada, it is important to situate it within the system. This historical overview examines Canada’s wavering commitment to comprehensive integration before and after 1990, which marks the year Canada joined the OAS, of which the IAS forms a part.[23] This discussion is followed by a short explanation of the principal entities that make up the IAS: the IACHR and the IACtHR.

A. Canada and the Inter-American System: Before 1990

As established in Section I, Pan-Americanism is a movement that calls for greater cooperation between America’s nations. Few Canadians know about this.[24] They know even less about the institutions that evolved out of this shared desire for regional cooperation, like the ones created to protect human rights such as the IACHR or the IACtHR. This ignorance is likely rooted in Canada’s historical disinterest in Latin America.

Peter McKenna examined the origins of this disinterest in great detail. He identified the 1890 First International Conference on American States as the initial historical event that exemplifies Canada’s limited involvement in Inter-American affairs. At this event, nations came together to create the International Union of American Republics, which eventually became the Pan-American Union (PAU) in 1910.[25] As Canada depended on Great Britain for all matters related to international relations, it was not invited, and missed out on what is considered as one of the first examples of clear action centered on the pursuit of regional solidarity and cooperation.[26]

McKenna highlights how the “psychological distance between Canada and the southern part of the hemisphere” is exemplified in several early 20th century events.[27] In 1910, US Secretary of State Elihu Root eagerly asked Canada to commit to full hemispheric cooperation and even called for “a chair with ‘Canada’ inscribed on the back [to be put to use] at the council table […].”[28] Over the years, it came to be referred to as the ‘empty chair’ given Canada’s shaky commitment to hemispheric political life.[29] This lack of engagement might have been the reason why Canada was never formally invited to join the PAU.[30] Further, while many Latin American countries were eager to develop diplomatic relations with Canada, others showed less enthusiasm as they wanted to avoid English dominance within the union. Finally, Canada did not view the Western hemisphere as the key arena in which to express its international priorities.[31]

Canada’s general complacency towards the Americas shifted during World War II. It realized that closer ties with Latin America might benefit its economy and sense of national security.[32] Despite this, it remained aloof. Lester B. Pearson, who was at the time Under Secretary of State for External Affairs, even stated that the government’s position was to be outside of PAU membership as it believed that it did not need to be part of the hemisphere’s principal institution to have positive relations with the Americas.[33] After World War II, Canada focused on the United Nations and on the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), with the latter better corresponding to Canada’s predominant English and French identities of the late 1940’s and 1950’s.[34]

While the OAS was founded in 1948[35], Canada remained detached until 1972, when it became a permanent observer at the organization.[36] While there were periods where Canada’s foreign policy focused more on Latin America, this interest was never sustained. This all changed in the summer of 1989, when Canada’s Department of External Affairs recommended joining the OAS.[37]

B. Canada and the Inter-American System: After 1990

After 18 years of observation, Canada became a full member of the OAS on January 8, 1990.[38] Canada’s entry into the organization demonstrated its international commitment “to respect human rights as provided for in the [OAS] Charter and in the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man.”[39] It listed its priorities to be in the areas of democracy, human rights and security.[40] National interest in Canadian membership was a result of the government’s conviction that greater ties with Latin America would respond to increased Canadian public awareness in the region and allow the government to pursue its political and economic interests.[41]

Shortly after its admission, Canada announced that it would likely ratify the Convention by the following spring.[42] At first, it seemed as if Canada was finally ready to become a full player in the system. This assertion was strengthened when Canada tried to elect retired Supreme Court Justice Bertha Wilson to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.[43] Canada quickly learnt that it could not present her as a candidate as it had not signed the ACHR. While government officials did manage to convince Venezuela and Uruguay to present her candidacy, she was defeated by one vote.[44] Given her recognized competence in the field of human rights, as well as the fact that a former foreign minister of Nicaragua’s Somoza government, which had demonstrated questionable concern for human rights, was elected in her place, this loss was especially devastating.[45] After Justice Wilson’s unsuccessful candidacy, Canada demonstrated less enthusiasm for ratifying the Convention.[46]

By 1999, Canada had still not ratified the Convention. When questioned about this inaction in the House of Commons, Minister of Foreign Affairs Lloyd Axworthy responded:

Before Canada can ratify a human rights convention, we must ensure that we are in a position to live up to the commitments we would undertake by ratifying it. Since 1991, consultations have been conducted with federal, provincial and territorial officials to assess compliance of federal and provincial legislation with the convention. The review process has been complicated by the vague, imprecise and outdated language used in the convention. Many provisions in the convention are ambiguous or contain concepts which are unknown or problematic in Canadian law. More importantly, many provisions of the convention are inconsistent with other international human rights norms, making it difficult for us to comply with both the ACHR and those norms […].

Canadians are already entitled to bring petitions to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights alleging human rights violations. Therefore, even without ratification of the ACHR, Canadians already benefit fully from the Inter-American human rights system.[47]

In 2003 and 2005, the Canadian Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights recommended that Canada adhere to the Convention in order to enhance Canada’s role in the OAS. The report clearly explained the IAS to a Canadian audience. It also highlighted the results of discussions with government and non-governmental actors in areas of concern within the Convention. The 2003 report highlighted why Canadian government officials were reluctant to ratify the ACHR. Many believed that the ratification of the Convention would have little impact on Canadians; that ratification would raise the issue of the jurisdiction of the Inter-American Court, and that Canada was already subjected to the jurisdiction of the Inter-American Commission.[48] The 2003 report set July 18, 2008 as the deadline for Canadian ratification of the Convention. By 2005, the second report was issued as the deadline was approaching and no action had yet been taken. By 2008, the Convention still had not been signed.

In the 2000s, Canadian government officials indicated their clear interest in regionally collaborating on economic issues, rather than on human rights. On his first trip to Latin America in 2007, Stephen Harper said that the Americas was a “critical international priority for our country [and] that Canada is committed to playing a bigger role in the Americas and to doing so for the long term.”[49] But Canada’s interest was specifically catered to the many Canadian companies that work in the region to extract non-renewable natural resources on a large-scale (and who are often critiqued for disregarding the rights of Indigenous peoples in the region).[50] Canada’s commitment to the IAS remains uncertain. As of May 2022, Canada has not signed the Convention.[51] Canada’s possible adherence remains a low public priority. Many Canadians remain unaware of the system’s existence.

C. Two Principal Entities for Human Rights in the Americas: The Inter-American Commission and the Inter-American Court

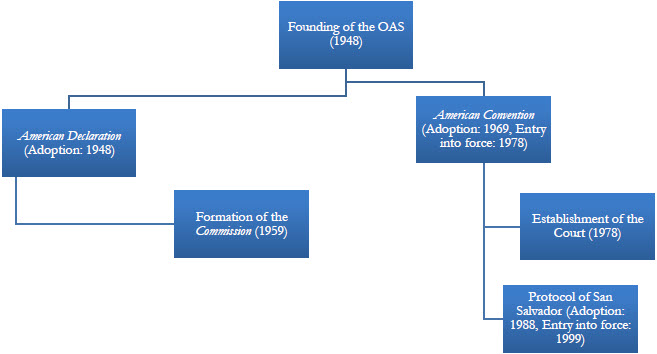

The IACHR and the IACtHR are the two monitoring bodies that make up the IAS and safeguard human rights in the region. They are responsible for ensuring the implementation of human rights set out in the 1948 American Declaration on the Rights and Duties of Man (ADRDM or American Declaration)[52] and in the 1969 Convention.[53] The IAS also derives authority from the Charter of the OAS[54] and several additional conventions and protocols that constitute the basic documents of the IAS.[55]

Figure 1

Organizational Chart of Relevant IAS Entities and Documents

Reference: “Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR): Basic Documents in the Inter-American System” (2011), online: OAS <www.oas.org/en/iachr/mandate/basic_documents.asp>.

D. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

The IACHR is responsible for ensuring that OAS Member States respect human rights.[56] The principal work of the Commission is accomplished through “the individual petition system; [the] monitoring of the human rights situation[s] in the Member States, and the attention devoted to priority thematic areas.”[57] The Commission can assess everyone – including non-signatories to the Convention. This is because it was created before the ACHR,[58] which obligates it to evaluate non-signatories in light of the American Declaration.[59]

The Commission is not a victim’s first stop. Before filing a complaint with the IACHR, the applicant[60] must have sought out competent judicial or administrative remedies within their states, as well as exercised all available rights of appeal.[61] If the petition is deemed admissible, and no friendly settlements can be reached, the Commission then files a report which provides recommendations to resolve the conflict.[62] If the conflict is not resolved, and the State respects the jurisdiction of the IACtHR, the case is referred to the Court.[63]

As Canada is a non-signatory, it is only subject to petitions rooted in the American Declaration.[64] Few petitions against Canada have been filed before the Commission. For example, in 2017, the Commission received 5 petitions against Canada, whereas it received 536 against Colombia and 819 against Mexico.[65] Duhaime rationalizes this difference in “the probable fact that fewer violations are committed in Canada than in most other member states and by the likely fact that the Canadian judicial system is comparably more capable to remedy violations internally, or at least appears to be perceived so.”[66] The low number of filed petitions may also be due to the lack of awareness amongst Canadians of the Commission as a recourse.

E. The Inter-American Court of Human Rights

The Inter-American Court was established in 1978 in accordance with article 33 of the Convention.[67] It is headquartered in San José, Costa Rica, although sessions are occasionally held away from its seat. It is composed of seven judges, all whom are representatives of Member States. Judges can be nationals of non-signatory states, however “only State Parties to the Convention may present candidates and elect judges.”[68] A Canadian has never served as a judge.

The Court serves three functions. First, it can issue an order or judgment on a contentious matter, “which is binding for states as a matter of public international law.”[69] Second, at the request of the Commission or any Member State, it can “adopt advisory opinions regarding the interpretation of the Convention, [the compatibility of one of its laws with the Convention] or [on] any other instrument related to human rights in the Americas.”[70] Finally, the Court can adopt provisional measures in serious and urgent cases. Claims can be brought by individuals against states, or by states against other states, although the latter is uncommon.

III. Canada’s Ratification of the Convention and Recognition of the Court’s Jurisdiction as a Supplementary Recourse for Indigenous Justice in Canada

This paper has explained how one’s interpretation of “being American” should center around the promotion of solidarity and mutual concern for the welfare of communities living on this continent. A historical account of Canada’s relationship with the IAS was presented in order to understand its relationship to the Americas. These sections have provided the necessary background to allow readers to understand the following analysis of whether Canada’s full commitment to the IAS would positively impact the rights of Indigenous peoples living within its borders.

This section is divided into five sub-sections. First, the current status of Indigenous rights in Canada will be overviewed. This section discusses how Indigenous peoples’ rights are not being respected despite the existence of a well-established political and legal framework. The second section examines how communities across the continent are increasingly relying on international law to enforce their human rights, especially when there is lack of political will and/or absence of domestic options. Third, the benefits of Canada’s full commitment to the IAS for Indigenous peoples within its borders are highlighted. Fourth, the IAS’s limitations on Indigenous rights in Canada are discussed. The final section concludes by stipulating that regardless of the system’s constraints, the more options, the better, and that the IAS should remain an available option for Indigenous peoples in Canada, if they wish to use it.

A. Indigenous Rights in Canada: The Challenges

Canada’s decision to not fully commit to the IAS negates another opportunity for Indigenous peoples to access recourses for the human rights violations experienced within the country’s borders.[73] Distressing socio-economic conditions, education barriers, inadequate housing, lack of access to health services, limited justice and safety and intrusions on Indigenous land are all examples of the ways Indigenous peoples rights are being violated in Canada.

Before summarizing the challenges to Indigenous rights in Canada, it is important to note how Canada’s legal framework is, in many ways, protective of Indigenous peoples’ rights.[74] These are succinctly outlined in the 2014 report issued by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, James Anaya:

[First], Canada’s 1982 Constitution [“CA, 1982”] was one of the first in the world to enshrine Indigenous peoples’ rights, recognizing and affirming the aboriginal and treaty rights of the Indian, Inuit and Métis people of Canada.[75] Those provisions protect aboriginal title arising from historical occupation, treaty rights and culturally important activities. [Second] Canada’s courts have developed a significant body of jurisprudence concerning aboriginal and treaty rights.[76] [Third] Canada is a party to the major United Nations human rights treaties, and in 2010, reversing its previous position, it endorsed the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. [Fourth] in 2008, Canada made a historic apology to former students of some Indian residential schools, in which it expressed a commitment to healing and reconciliation […] some action has been taken in this regard, including the ongoing implementation of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement […] and the creation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.[77]

While the Canadian government has taken many actions to maintain positive relations with Indigenous peoples, many challenges remain.[78] Indigenous peoples face constant barriers in Canada and are consistently disadvantaged as compared to non-Indigenous peoples.

1. Distressing socio-economic conditions

Canada is considered to be a developed country.[79] Despite its high standard of living, many Indigenous peoples in Canada live in distressing socio-economic conditions. In his 2014 report, James Anaya highlighted that “of the bottom 100 Canadian communities on the Community Wellbeing Index, 96 are First Nations, while only one of the top 100 communities are First Nations communities.”[80] In a 2010 Report (CHRC Report) on Equality Rights of Aboriginal Peoples, the Canadian Human Rights Commission (CHRC) showed that “regardless of age and sex, the proportion of Aboriginal adults in low-income status is much higher than those of non-Aboriginal adults.”[81]

2. Education barriers

Education is closely correlated to socio-economic well-being. It is also used to measure a country’s level of human development on an international scale.[82] Indigenous children face barriers in educational enrolment and attainment. One reason for this discrepancy is the jurisdictional confusion that arises from Indigenous peoples falling under federal jurisdiction while education is under provincial jurisdiction. Poverty, discrimination and a history of colonialism also explain why “at every level of education, Indigenous peoples continue to lag far behind the general population.”[83] The lack of culturally relevant education also contributes to these unsettling discrepancies.

3. Inadequate housing

An estimated 20,000 peoples in First Nations communities across Canada have no running water or sewage.[84] One in five Indigenous peoples live in a dwelling that is in need of major repairs.[85] Anaya describes the housing situation in Inuit and First Nations communities as a “crisis”, especially in the North, where extreme weather intensifies housing problems.[86]

4. Lack of access to health services

Canada’s federal government has jurisdiction over Indigenous peoples through section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867 (CA 1867).[87] Canada’s provinces have jurisdiction over certain matters such health services through s.92 (8) of the CA 1867.[88] Regional authorities might also have jurisdiction over the provision of health services to their citizens. These overlapping jurisdictions can result in grave consequences, as different orders of government rely on each other to act.[89] Oftentimes, Indigenous peoples will be the first to slip through the system’s cracks.[90]

5. Limited justice and safety

Indigenous peoples are overrepresented in the Canadian criminal justice system. The CHRC Report demonstrates that “regardless of sex, the proportion of Aboriginal offenders incarcerated is substantially higher than that of non-Aboriginal offenders.”[91] Furthermore, Indigenous peoples comprise of 24 percent of Canada’s prison population, while only making up 4 percent of the general population.[92]

In addition, Indigenous peoples, and specifically Indigenous women and girls, are vulnerable to higher levels of domestic abuse and crime. Over the past twenty years, NWAC has documented “over 660 cases of women and girls across Canada who have gone missing or been murdered.”[93]

6. Intrusions on Indigenous land

In Canada, many communities have been fighting for years to assert their rights to their lands. Anaya underscores a chilling contradiction that Indigenous peoples live with daily: “so many live in abysmal conditions on traditional territories that are full of valuable and plentiful natural resources.”[94] Much like their Latin American counterparts, the land of Indigenous peoples in Canada has been exploited by their colonizers.[95] Anaya draws attention to the many proposed or implemented development projects that have posed great concern to Indigenous communities in Canada,[96] including the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain pipeline twinning project and the Site C hydroelectric dam on the Peace River affecting Treaty 8 nations.[97]

It appears evident that the status of Indigenous rights in Canada is still abysmal. While there are many Indigenous and domestic mechanisms through with to assert Indigenous rights, Indigenous communities in Canada might find international law to be yet another tool to denounce these injustices.

B. Indigenous Rights and International Law

International law is an avenue where Indigenous communities are increasingly asserting their rights. When there are no laws that recognize Indigenous rights, or such laws exist but there is no political will to enforce them, or when communities are simply looking for a supplementary recourse, they turn to parallel human rights systems like the IAS.[98]

A case at the Commission shows how an Indigenous person in Canada asserted their rights on an international stage, and notably within the IAS.[99] Grand Chief Michael Mitchell of the Mohawk First Nation presented a petition against Canada to the Commission in 2001, alleging that Canada violated the right to culture in Article XIII of the American Declaration.[100] The petitioners (Mitchell and his representation - Hutchins Caron & Associés in Montréal) contended that “Canada had incurred international responsibility for denying Grand Chief Mitchell’s right to bring goods, duty free, across the U.S./Canada border dividing the territory of the Indigenous community.”[101] Canada rejected the petitioners’ contention and responded that the “Canadian courts recognized an aboriginal claim to duty-free trade during the domestic proceedings.”[102] Further, they raised a tension that will be eventually discussed in the sub-section on the IAS’ limitations. The Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) had already ruled on this matter, so they said that “it [was] not the role of the Commission to re-assess findings of fact made by the Supreme Court.”[103]

While the Commission eventually rejected the petitioners’ claims[104], this claim remains a notable example of an Indigenous person mobilizing to get their rights recognized in a non-Canadian forum. The next section examines how more actions like this could better monitor, promote and protect the human rights of Indigenous peoples in Canada.

C. The Inter-American Human Rights System as a Mechanism to Protect Indigenous Rights in Canada

In 2003 and 2005, the Canadian Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights recommended that Canada adhere to the Convention in order to play a greater role in the OAS. Canadian scholarship has recently addressed the benefits of Canada’s full participation in the IAS.[105] While these discussions have briefly touched on the impact of Canada’s complete adherence for human rights in Canada, few have focused on how this decision could impact Indigenous rights in Canada. This section proposes four ways in which Canada’s ratification of the Convention and recognition of the Court’s jurisdiction could better protect Indigenous rights in Canada.

1. It is a supplementary recourse for protecting Indigenous rights in Canada

A previous section highlighted the numerous gaps that exist between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada. Should Canada sign the Convention, Indigenous peoples could use the applicable law to uphold the rights that are currently being violated.

First, the Convention calls for the protection of certain rights that relate to previously discussed issues, including rights of the child, to life, humane treatment, personal liberty, fair trial, privacy, property, equal protection, judicial protection, freedom of movement and residence, and freedom from slavery.[106] Article 26 even calls for State Parties to fully commit to the realization of economic, social, educational and cultural rights in their countries.[107]

Of particular interest is Article 21 given that it protects the right to property, which is a right that is not enshrined in Canada’s Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms (Charter).[108] This provision may be especially relevant in cases related to the exploitation of Indigenous land. In the 2003 Senate Report, questions were raised about the provision’s potential incompatibility with Canadian law due to its focus on individual (rather than collective) property rights.[109] This critique was quickly rebutted by a judgment of the IACtHR which includes Indigenous communities’ collective property rights as part of Article 21.[110] As a result, the Senate Committee decided that there was no incompatibility between the provisions of Canadian law respecting Aboriginal title to land, including section 35 of the CA, 1982, and article 21 of the Convention.[111]

Second, the Court has issued a multitude of decisions that address the human rights violations that Indigenous peoples are currently experiencing in Canada. Indigenous groups could certainly refer to these. This is especially relevant in cases of femicide, which is also occurring in Canada in the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.[112] Campo Algodonero (or “Cotton Field” in English) is one of the Court’s most famous cases on femicide.[113] In this case, three young women disappeared after leaving work in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. Their families received no help from law officials, as they dismissed their claims saying that these young women were “probably with their boyfriends.”[114] They were eventually found murdered in the cotton fields of Ciudad Juárez. Their bodies displayed clear signs of physical abuse, torture, mutilation and sexual abuse.[115] The case eventually made it to the Court. The repercussions of the Court’s ruling were monumental for Inter-American case law as the judgment “became a point of reference for many judicial and quasi-judicial bodies dealing with cases of violence against women (“VAW”), […] the relations between discrimination and VAW, and the scope of States’ obligations.”[116] While this judgment did not specifically address the disappearance of Indigenous women, it clarified how reparations for gender-based violence are understood.

Other judgments have dissected the Court’s standards for situations where Indigenous women experience violence. For example, Fernández Ortega touched on the difficulties encountered by Indigenous women in accessing justice, especially when raped and/or tortured by government authorities.[117] Similarly, Rosendo Cantú highlighted the special needs of women, minors and Indigenous communities after surviving sexual violence.[118] These decisions set precedents which may be useful to groups advocating for Indigenous rights in Canada, especially with regard to missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

Third, Canada’s full commitment to the IAS would provide for greater and broader international human rights protection for Indigenous communities. This point is succinctly explained by Duhaime:

Currently, persons alleging violations of their human rights who are unable to obtain a remedy domestically may only refer their claims internationally to the United Nations Human Rights Committee (alleging violations of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights) or to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (alleging violations of the American Declaration). While both institutions provide for a valid international remedy, neither the UN Committee nor the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights allows for a full trial, during which oral arguments are made, witnesses and experts can be examined, and exhibits can be presented. The Inter-American Court provides for such a process, which allows for a fuller, more complete procedure, more visibility for issues and victims, as well as greater procedural judicial guarantees for states willing to defend themselves.[119]

The Senate Committee also highlights other benefits of ratifying the Convention which could in turn, positively impact Indigenous communities in Canada. Ratifying the Convention would make it possible for Canada to ratify the San Salvador Protocol on Social, Economic and Cultural Rights (an additional protocol to the Convention), which would give communities access to IACHR cases on trade union rights, the right to education, the right to health, the right to a healthy environment, the right to food and more.[120]

2. It is an opportunity to facilitate sharing strategies

Even though every country is bound by its own history and political context, there are common issues that are dealt with in the IAS. Canada’s adherence to the Convention would ultimately result in Canada’s greater participation in the myriad of opportunities and events that make up Inter-American culture. Adhesion would allow for Indigenous groups in Canada to participate in the system’s activities. This could result in their construction of greater linkages with other Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups in the Americas. Integration in the IAS would facilitate networking between Indigenous communities which would allow them to share ideas and strategies across international boundaries. Canada’s provision of this type of network would be in line with this paper’s definition of “being American” as this would be an example of communities working with others towards the mutual objective of promoting the well-being of peoples in this continent. While not only catered to Indigenous groups, SOAA is an example of a project that seeks this very purpose, as it is a space for Canadians “to better understand, share and propose solutions drawn from the Latin American experience of human rights violations claims and denunciations” in order to find solutions to encourage states to better promote and protect human rights.[121]

3. Canada’s submission to international scrutiny increases its credibility

Canada is certainly not doing human rights “better” than everyone else. International checks and balances are necessary with regards to Canada’s commitment to human rights. Canada’s full participation in the IAS would allow for its promise to improve relations with Indigenous peoples to be scrutinized on an international stage.

Canada has already been scrutinized in the IAS, such as through the Commission’s 2014 report on missing and murdered Indigenous women in British Columbia.[122] The report sought to turn international and regional attention to this issue in Canada. Inquiries such as that report could encourage domestic and international mobilization in support of state practices that correspond to Canada’s responsibility to uphold Indigenous rights. Canada’s adhesion to the IAS would allow for it to be fully evaluated. Further, it would be hypocritical for Canada to publicly denounce the actions of other IAS Member States if it did not care for bolstering its own human rights reputation.[123] Ultimately, some scrutiny would be helpful in ensuring that Canada fulfills its human rights obligations towards Indigenous peoples.

4. More cases about Canada in the IAS would enrich the system’s case law and could support Indigenous justice across the continent

This paper’s view is that “being American” means being willing to learn from each other. Canada’s ratification of the Convention would allow for it to contribute and learn from IAS case law. As Canada’s judiciary is autonomous, independent and efficient, it “is reasonable to assume [that] most cases brought against Canada before the Inter-American Commission and later to the Court would likely have exhausted all domestic remedies, including Canadian Supreme Court processes, and would essentially deal with controversial, complex, and sophisticated issues of law and policy.”[124] Canada’s adhesion to the Convention would allow it to take part in debates over greater hemispheric questions, which could potentially impact Indigenous peoples in Canada.

D. The Limitations of the Inter-American Human Rights System for Indigenous Rights in Canada

The next section highlights the limitations of the IAS in protecting Indigenous rights in Canada.

First, Indigenous peoples in Canada already have many domestic options for recourses in cases of human rights violations. In some instances, they can turn to their communities for guidance. They can bring a case to Canada’s domestic courts. They are protected under section 35 of the CA, 1982, as all levels of government, including federal, provincial, territorial, municipal and Indigenous must uphold Indigenous and treaty rights.[125] Individuals or communities can file a complaint with the CHRC or any of the provincial human rights commissions. Would another legal opinion be the most effective solution?

Second, the Commission and the Court’s effectiveness has been scrutinized, and with reason. Delays are one of the IAS’s greatest limitations. There is a constant backlog of cases and petitions waiting to be processed. At the Commission, it takes an average of six and a half years from the initial submission of a petition to the final decision on the merits.[126] In 2017, it was determined that the average time required to process cases before the Court was approximately 24,7 months.[127] Delays between the first complaint and the Court’s decision have stretched more than 20 years. These significant delays stretch far beyond the 18-month deadline instituted by the Supreme Court of Canada in R v Jordan (2016).[128] The delays are mostly due to the system’s lack of resources. Both the Commission and the Court lack the necessary human resources to provide timely responses. These institutions are heavily dependent on a temporary workforce, mostly comprised of students and visiting professionals. This constant 3-4-month turnover can greatly impact productivity. Could it even be guaranteed that Indigenous peoples in Canada would receive timely justice through the IAS?

Third, the system has been criticized for the observed low levels of compliance with its rulings. In a 2010 study, Basch et al researched states’ degree of compliance with decisions adopted within the framework of the system of petitions of the Convention. They show, that on average, total compliance is found in 47% of the cases and partial compliance in 13%.[129] Many reasons explain these numbers, which include the general rule of law climate in some Member States, or a state’s commitment to human rights and the standards set out in the IAS. Regardless of the reason, it is important to consider that even if Canada did adhere to the Convention, it may not respect the decisions of the Commission or the Court if it is not entirely convinced of their legitimacy. Would the system therefore have any impact for Indigenous human rights protection in Canada?

Fourth, few Indigenous peoples may even know about the system as a recourse. Duhaime explains Canada’s low participation in the IAS is mostly due “to a lack of knowledge of the system in general among Canadian victims and the Canadian legal community.”[130] How could the system be a supplementary recourse for Indigenous justice, if communities do not know about it?

Finally, Indigenous peoples in Canada may view the IAS as incompatible with their circumstances. Is a Commission or Court really the best avenue through which to express their human rights concerns? International judicial action may not be the recourse they need.[131] It was already established that the system can be ineffective and inefficient, which may deter some from participating. In addition, Indigenous communities in Canada may perceive the IAS-established human rights norms as inapplicable to their conditions and “to reflect a model of relationships between Indigenous populations and the state based on a variety of Latin American realities that are radically different from those in English-speaking North America.” [132] Ultimately, Indigenous peoples may feel that this regional system is not preferable given that the borders that define its jurisdiction are those of a colonial state. Why would they submit themselves to a jurisdiction they do not consider to be theirs?

E. The More, the Better: An International Option for Indigenous Peoples in Canada

It is important to understand the IAS’s limitations in order to have realistic expectations of its capabilities. Regardless of the system’s constraints, it should still remain an available option for Indigenous peoples in Canada.

The IAS human rights protection should be available if communities wish to use it. It should not replace existing human rights mechanisms but instead provide an alternative option. The 2003 Senate Report persuasively summarizes this point:

Although it is true that Canadians already enjoy protection under the Charter as well as federal and provincial human rights legislation, this Committee believes that human rights norms and complaint mechanisms are developed for the benefit of individuals, not the State. It cannot be said that people have so much protection that they do not need any more. In addition, ratification of international treaties and recognition of the jurisdiction of the bodies created to oversee their implementation give another level of protection not afforded by domestic courts, especially in Canada where the absence of legislation implementing international treaties seriously limits the possibility of invoking them before the courts.[133]

As such, Canada’s full commitment to the IAS would not radically alter existing domestic frameworks.[134] Instead, it might reinforce the government’s commitment to reconciliation as it would be allowing itself to be submitted to scrutiny on the international stage. A third party with no history of abuse towards Canada’s Indigenous peoples would be able to scrutinize Canada’s regard for their rights, which may mobilize an increased number of state policies and practices that uphold Indigenous rights.

***

It is time for Canada to become a better player in the Inter-American system. If Canada considers itself “a country of the Americas” and places “great value on building and nurturing relationships with partners in the Americas”, it should sign the Convention and recognize the Court’s jurisdiction.[135] If Canada claims to be “committed to achieving reconciliation” it should not negate a supplementary opportunity for Indigenous justice in Canada.[136]

This paper has demonstrated that Canada’s full commitment to the IAS would provide a further recourse for monitoring, protecting and promoting Indigenous rights in Canada. Although Canada claims to be “a champion of human rights”, Indigenous peoples are often most adversely affected by inequities in this country.

Other individuals and organizations understand how full participation in the IAS could benefit Indigenous peoples in Canada. Bernard Duhaime, a professor of international law at the UQAM and one of the only Canadian specialists on the Inter-American system, leads the “S’ouvrir aux Amériques” project.[137] This initiative is an example of Canadians connecting to their continental identity in order to promote human rights within their country. It is now up to the Canadian government to follow their lead.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

Philip Alston, “Against a World Court for Human Rights” (2014) Ethics and International Affairs, NYU School of Law, Public Research Paper No. 13-71 1 at 8.

-

[2]

For a list of acronyms, please see Appendix I.

-

[3]

American Convention on Human Rights, 22 November 1969, O.A.S.T.S. No. 36, 1144 UNTS 123 at Preamble (entered into force 18 July 1978) [Convention].

-

[4]

Ibid.

-

[5]

Ibid.

-

[6]

James Anaya, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, UNHRC, UN Doc A/HRC/27/52/Ad 2 (2014) 1 at 1 [Anaya].

-

[7]

Jo M Pasqualucci, “The Evolution of International Indigenous Rights in the Inter-American Human Rights System” (2006) 6:2 Hum Rts L Rev 281 at 282 [Pasqualucci].

-

[8]

Ibid.

-

[9]

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women in British Columbia, Canada” (2014) 1 at 18, online (pdf): Inter-American Commission on Human Rights <www.oas.org/en/iachr/reports/pdfs/Indigenous-Women-BC-Canada-en.pdf> [MMIW BC Report].

-

[10]

A state party must ratify the Convention and submit to the Court’s jurisdiction in order to have contentious cases heard or be brought against them. Nevertheless, non-signatory members can still request advisory opinions from the Court.

-

[11]

See “Our Project” (2018), online: SOAA: S’ouvrir aux Amériques <soaa.uqam.ca/project/> [SOAA, “Our Project”].

-

[12]

In this paper, Indigenous justice means the monitoring, protection and promotion of Indigenous rights.

-

[13]

Canada, Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights, Enhancing Canada’s Role in the OAS: Canadian Adherence to the American Convention on Human Rights (Ottawa: The Senate, 2003) (The Honourable Shirley Maheu) at 8 [2003 Senate Report].

-

[14]

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary, online, sub verbo “Pan-Americanism”.

-

[15]

Carol Hess, Representing the Good Neighbor: Music, Difference, and the Pan American Dream (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013) at 1-2.

-

[16]

Arthur P Whitaker, “The Origin of the Western Hemisphere Idea” (1954) 98:5 Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 323 at 323 [Whitaker].

-

[17]

“Monroe Doctrine” (last modified 26 April 2017), online: The Library of Congress – Virtual Services Digital Reference Section <www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/ourdocs/monroe.html>.

-

[18]

Whitaker, supra note 16 at 323.

-

[19]

Ibid.

-

[20]

For example, in Latin America many refer to the American continent as Abya Yala. See Penny A Weiss, ed, Feminist Manifestos: A Global Documentary Reader (New York: NYU Press, 2018) at 519. In North America, many refer to North America as Turtle Island. See “Turtle Island – where’s that?” (2018), online: CBC Kids <www.cbc.ca/kidscbc2/the-feed/turtle-island-wheres-that>.

-

[21]

Territorial acknowledgement is now common practice at many universities in Canada. See Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT), “CAUT Guide to Acknowledging Traditional Territory” (2006), online: Canadian Association of University Teachers <www.caut.ca/content/guide-acknowledging-first-peoples-traditional-territory>.

-

[22]

Jimmy Ung, Americano: Photo Stories (Montreal, 2016) at 1.

-

[23]

Bernard Duhaime, “Canada and the Inter-America Human Rights System: Time to Become a Full Player” (2012) 67:3 Intl J 639 at 639 [Duhaime, “Time to Become a Full Player”].

-

[24]

Bernard Duhaime, “Strengthening the Protection of Human Rights in the Americas: A Role for Canada”, in Monica Serrano, ed, Human Rights Regimes in the Americas (Tokyo: United Nations University Press, 2010) 84 at 87 [Duhaime, “Strengthening the Protection of HR”].

-

[25]

“2003 Senate Report”, supra note 13 at 8.

-

[26]

Peter McKenna, “Canada and the Inter-American System, 1890-1968” (1995) 41:2 Australian J Politics and History 253 at 254 [McKenna].

-

[27]

Ibid at 253.

-

[28]

Ibid at 254.

-

[29]

Ibid.

-

[30]

“2003 Senate Report”, supra note 13 at 8.

-

[31]

Laurence Cros, “Canada’s Entry into the OAS: Change and Continuity in Canadian Identity” (2012) 67:3 Intl J 725 at 727 [Cros].

-

[32]

“2003 Senate Report”, supra note 13 at 9.

-

[33]

McKenna, supra note 26 at 263.

-

[34]

Cros, supra note 31 at 732.

-

[35]

“Canada and the Organization of American States” (last modified July 13 2018), online: Government of Canada <www.international.gc.ca/world-monde/international_relations-relations_internationales/oas-oea/index.aspx?lang=eng#a2> [“Canada and the OAS”].

-

[36]

“2003 Senate Report”, supra note 13 at 10.

-

[37]

Ibid.

-

[38]

“Department of International Affairs: Order of Entry” (2018), online: OAS <www.oas.org/en/ser/dia/perm_observers/entry.asp>.

-

[39]

Duhaime, “Time to Become a Full Player”, supra note 23 at 639.

-

[40]

“Canada and the OAS”, supra note 35.

-

[41]

“2003 Senate Report”, supra note 13 at 11.

-

[42]

William A Schabas, “Substantive and Procedural Hurdles to Canada’s Ratification of the American Convention on Human Rights” (1991) 16:3 Nethl QHR 315 at 316 [Schabas].

-

[43]

Ibid at 320.

-

[44]

“2003 Senate Report”, supra note 13 at 23.

-

[45]

Schabas, supra note 42 at 320.

-

[46]

Schabas, supra note 42 at 321.

-

[47]

“2003 Senate Report”, supra note 13 at 6.

-

[48]

Ibid at 40-41. The Senate Report also expressed concern about Article 4(1) of the Convention which guarantees the right to life “in general from the moment of conception.” At the time of the report’s writing, many women’s associations voiced their concerns that the provisions of article 4(1) could be used to prohibit abortions or access to contraceptives in Canada.

-

[49]

Andrew F Cooper, “Canada’s Engagement with the Americas in Comparative Perspective: Between Declaratory Thickness and Operational Thinness” (2012) 67:3 Intl J 685 at 695.

-

[50]

Working Group on Mining and Human Rights in Latin America, “The Impact of Canadian Mining in Latin America and Canada’s Responsibility: Executive Summary” (2014) at 20, online (pdf): DPLF – Fundación para el debido proceso <www.dplf.org/sites/default/files/report_canadian_mining_executive_summary.pdf>.

-

[51]

A 2019 publication by Honourable Marie Deschamps, former justice of the Supreme Court of Canada, points out many issues with Canada’s possible accession to the ACHR. See Marie Deschamps, “L’approche Canadienne: assurer la protection des droits de la personne de façon distinctive” (2019) 49 RGD 29 [Deschamps].

-

[52]

The American Declaration, alongside the Convention, is one of the two main OAS instruments that outlines states’ human rights obligations. See American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, 30 April 1948 (entered into force 30 April 1948) [American Declaration].

-

[53]

Convention, supra note 3.

-

[54]

The Charter is the document that sets out the creation of the OAS. See Charter of the Organization of American States (A-41), 30 April 1948 (entered into force 13 December 1951).

-

[55]

“Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR): Basic Documents in the Inter-American System” (2011), online: OAS <www.oas.org/en/iachr/mandate/basic_documents.asp>.

-

[56]

“Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR): Statute of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights” (2011) at art 18, online: OAS <www.oas.org/en/iachr/mandate/Basics/statuteiachr.asp>.

-

[57]

“Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR): What is the IACHR?” (2011), online: OAS <www.oas.org/en/iachr/mandate/what.asp>.

-

[58]

The Commission was created in 1959 whereas the Convention entered into force in 1978.

-

[59]

Schabas, supra note 42 at 317-318; “Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR): Rules of Procedure of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights” (2011) at art 51, online: OAS <www.oas.org/en/iachr/mandate/basics/rulesiachr.asp> [“IACHR Rules of Procedure”].

-

[60]

The applicant can be a state, non-governmental organizations or individuals.

-

[61]

Bernard Duhaime, “Le système interaméricain et la protection des droits économiques, sociaux et culturels des personnes et des groupes vivant dans des conditions particulières de vulnérabilité” (2007) 44 Can YB Intl Law 95 at 115-116.

-

[62]

“IACHR Rules of Procedure”, supra note 59 at art 47.

-

[63]

Ibid at art 45.

-

[64]

Duhaime, “Time to Become a Full Player”, supra note 23 at 641.

-

[65]

“Statistics by Country”, (2016), online: Inter-American Commission on Human Rights <www.oas.org/en/iachr/multimedia/statistics/statistics.html>.

-

[66]

Duhaime, “Time to Become a Full Player”, supra note 23 at 642.

-

[67]

“2003 Senate Report”, supra note 13 at 23.

-

[68]

Ibid.

-

[69]

Duhaime, “Time to Become a Full Player”, supra note 23 at 640.

-

[70]

Ibid.

-

[71]

Ibid.

-

[72]

Ibid at 644.

-

[73]

Anaya, supra note 6 at 1.

-

[74]

Ibid at 5.

-

[75]

See Constitution Act, 1982, s 35 being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11.

-

[76]

Delgamuukw v British Columbia, [1997] 3 SCR 1010, 153 DLR (4th) 193; Haida Nation v British Columbia (Minister of Forests), [2004] 3 SCR 511, 245 DLR (4th) 33.

-

[77]

Anaya, supra note 6 at 5-6.

-

[78]

In Canada, “reconciliation” is the term used by the Government of Canada to highlight its work in rebuilding its relationship with Indigenous peoples. The Canadian government’s approach to reconciliation is guided by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action, constitutional values and collaboration with Indigenous peoples as well as provincial and territorial governments. See: “Principles respecting the Government of Canada's relationship with Indigenous peoples” (last modified 14 February 2018), online: Government of Canada – Department of Justice <www.justice.gc.ca/eng/csj-sjc/principles-principes.html> [Department of Justice]. Note that reconciliation is not the preferred term for some Indigenous peoples. For example, some prefer to use the word “rebuild” instead of “reconciliation”. See: “Reconciliation isn’t dead. It never truly existed” (29 February 2020), online: The Globe and Mail <www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-reconciliation-isnt-dead-it-never-truly-existed/>.

-

[79]

“Top 25 Developed and Developing Countries” (last modified 21 November 2019), online: Investopedia <www.investopedia.com/updates/top-developing-countries/>.

-

[80]

Anaya, supra note 6 at 7.

-

[81]

“Report on Equality Rights of Aboriginal People” (2013) at 17, online (pdf): Canadian Human Rights Commission <www.chrc-ccdp.gc.ca/sites/default/files/equality_aboriginal_report.pdf> [CHRC Report].

-

[82]

CHRC Report, supra note 81 at 34.

-

[83]

Anaya, supra note 6 at 7.

-

[84]

“Americas: Sacrificing Rights in the Name of Development: Indigenous Peoples Under Threat in the Americas” (2011) at 4, online (pdf): Amnesty International <www.amnesty.org/en/documents/AMR01/001/2011/en/>.

-

[85]

Statistics Canada, “The Housing Conditions of Aboriginal People in Canada”, Catalogue No 98-200-X2016021 (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2016) at 1.

-

[86]

Anaya, supra note 6 at 8.

-

[87]

Constitution Act, 1867 (UK), 30 & 31 Vict, c 3, s 91(24), reprinted in RSC 1985, Appendix II, No 5.

-

[88]

Ibid at s 92(8).

-

[89]

Anaya, supra note 6 at 10.

-

[90]

Government of Canada, “Honouring Jordan River Anderson” (last modified August 8 2019), online: Gouvernment of Canada <www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1583703111205/1583703134432>.

-

[91]

CHRC Report, supra note 81 at 54.

-

[92]

Anaya, supra note 6 at 10.

-

[93]

Ibid at 11.

-

[94]

Ibid at 17.

-

[95]

Eduardo Galeano, Open Veins of Latin America (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1997); Pamela Palmater, “Decolonization is taking back our power” in Peter McFarlane and Nicole Shabus, eds, Whose Land is it Anyway? A Manual for Decolonization (Vancouver: Federation of Post-Secondary Educators of BC, 2017) at 74.

-

[96]

Ibid at 18-19.

-

[97]

Ibid.

-

[98]

Pasqualucci, supra note 7 at 282.

-

[99]

See Grand Chief Michael Mitchell v Canada (2008), Inter-American Comm HR, No 61/08, Annual Report of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights: 2008, OEA/Ser L/V/II 134/doc 5, rev 1 [Grand Chief Mitchell].

-

[100]

American Declaration, supra note 52 at Article XIII.

-

[101]

The Akwesasne territory encompasses portions of the Canadian provinces of Quebec, Ontario and the State of New York in the United States; Grand Chief Mitchell, supra note 99 at para 3.

-

[102]

Ibid at para 48.

-

[103]

Ibid; See Mitchell v MNR, [2001] 1 SCR 911, 199 DLR (4th) 385.

-

[104]

Grand Chief Mitchell, supra note 99 at para 84.

-

[105]

See Nelson Arturo Ovalle Diaz, “Introduction“ (2019) 49 RGD 1 at 10.

-

[106]

See Convention, supra note 3 at arts 4-8, 11, 16, 19, 21, 22, 24 and 25.

-

[107]

Convention, supra note 3 at art 26.

-

[108]

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Part 1 of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), c 11.

-

[109]

“2003 Senate Report”, supra note 13 at 47.

-

[110]

Ibid; Mayagna (Sumo) Community of Awas Tingni (Nicaragua) (2001), Inter-Am Ct HR (Ser C) No 79 at paras 148-149 [Mayagna], Annual Report of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights: 2001, OEA/Ser L/V/III 54 Doc 4 (2002).

-

[111]

“2003 Senate Report”, supra note 13 at 47.

-

[112]

For examples of decisions that address human rights violations experienced by Indigenous peoples that are not femicides see Mayagna, supra note 110 and Norín Catrimán et al. (Leaders, Members and Activists of the Mapuche Indigenous Peoples) v Chile (2014), Inter-Am Ct HR (Ser C) No 279.

-

[113]

González et al (“Cotton Field”) (Mexico) (2009), Inter-Am Ct HR (Ser C) No 205, Inter-American Yearbook on Human Rights: 2009, Vol: 25 (2013).

-

[114]

Ibid at para 147.

-

[115]

Ibid at para 125.

-

[116]

Lorena PA Sosa, “Inter-American Case Law on Femicide: Obscuring Intersections” (2017) 35:2 Nethl QHR 85 at 85.

-

[117]

Fernández Ortega et al (Mexico) (2010), Inter-Am Ct Hr (Sec C) No 215, Inter-American Yearbook on Human Rights: 2010, Vol: 26 (2014).

-

[118]

Rosendo Cantú et al (Mexico) (2010), Inter-Am Ct Hr (Sec C) No 216, Inter-American Yearbook on Human Rights: 2010, Vol: 26 (2014).

-

[119]

Duhaime, “Time to Become a Full Player”, supra note 23 at 649.

-

[120]

“2003 Senate Report”, supra note 13 at 56-57; Additional Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights in the Area of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights “Protocol of San Salvador”, 17 November 1988 (entered into force 16 November 1999).

-

[121]

SOAA, “Our Project”, supra note 11.

-

[122]

“MMIW BC Report”, supra note 9.

-

[123]

“2003 Senate Report”, supra note 13 at 56.

-

[124]

Duhaime, “Time to Become a Full Player”, supra note 23 at 651.

-

[125]

“MMIW BC Report”, supra note 9 at 60-61.

-

[126]

“Maximizing Justice, Minimizing Delay: Streamlining Procedures of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights” (2011) at 4, online (pdf): Human Rights Clinic – The University of Texas School of Law <law.utexas.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2015/04/2012-HRC-IACHR-Maximizing-Justice-Report.pdf>.

-

[127]

“Annual Report 2017” (2018) at 60, online (pdf): Inter-American Court of Human Rights <www.corteidh.or.cr/tablas/informe2017/ingles.pdf>.

-

[128]

Deschamps, supra note 51 at 40.

-

[129]

Fernando Felipe Basch, “The Effectiveness of the Inter-American System of Human Rights Protection: A Quantitative Approach to Its Functioning and Compliance with Its Decisions” (2010) 7:12 Sur - Intl JHR 9 at 18.

-

[130]

Duhaime, “Strengthening the Protection of HR”, supra note 24 at 87.

-

[131]

Martha Minow, “Law and Social Change” (1993) 62:1 UMKC L Rev 171 at 173.

-

[132]

Paolo Carozza, “The Anglo-Latin Divide and the Future of the Inter-American System of Human Rights” (2015) 5:1 Notre Dame J Intl & Comparative L 153 at 165.

-

[133]

“2003 Senate Report”, supra note 13 at 40 [emphasis added].

-

[134]

Canada’s federalist system should not be considered to be an obstacle to Canadian ratification of the Convention as other federal states such as Mexico, Brazil and Argentina have successfully implemented the Convention.

-

[135]

“Canada and the OAS”, supra note 35.

-

[136]

Department of Justice, supra note 78.

-

[137]

SOAA, “Our Project”, supra note 11.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Organizational Chart of Relevant IAS Entities and Documents

Reference: “Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR): Basic Documents in the Inter-American System” (2011), online: OAS <www.oas.org/en/iachr/mandate/basic_documents.asp>.