Résumés

Abstract

In Letitia Elizabeth Landon’s The Improvisatrice, the physical body of the book puns on the female body. The erotics of poetess poetry is anchored in the sensuality of "embellishments," including the elaborate chirographic renditions of the initials “L.E.L.” Landon capitalizes on by eroticizing / embellishing all kinds of writing already in circulation. Moreover, The Improvisatrice enacts a kind of viewing that L.E.L. wants readers to participate in as they read. The poem encourages readers to engage in an "onanistic poesaphilia," to witness and participate in thinly-veiled pornographic scenes of indulgence in poetic sensibility. Landon presumes that being entertained consists in reading about people writing erotically. L.E.L.'s heroines are less passive sentimental victims than the proponents of "safe sex," an eroticism that is both bookish and solitary.

Corps de l’article

Critics have alternately lauded, berated, lionized, and condemned Letitia Elizabeth Landon as the paragon of poetic sensibility since the 1824 publication of The Improvisatrice; and Other Poems. Landon’s first major collection included thirty-six poems, but it was the title work that garnered the most attention and stimulated readers’ conflation of the writer with her Corinne-inspired eponymous heroine. From the unnamed reviewer for The Literary Magnet, who commented, “[Landon] appears to be the very creature of passionate inspiration; and the wild and romantic being whom she describes as the Improvisatrice seems to be the very counterpart of her sentimental self” (McGann, ed., 295) to twentieth-century critic Anne Mellor, who argues that “Both [Landon’s] life and her poetry finally demonstrate the literally fatal consequences for a woman in the Romantic period who wholly inscribed herself within Burke’s aesthetic category of the beautiful” (1993, 123), readers have been quick to identify Landon as the improvisatrice herself, “a real-life, and therefore more tawdry, Corinne” (Leighton 45). Recent critical interventions, such as those by Isobel Armstrong, Harriet Linkin, and Tricia Lootens have offered a refreshing counterpoint to the predominant critical position that “L.E.L. thought of herself as an improvisatrice” (Greer 16), but a nearly two-hundred-year-old legend dies hard. As recently as September 2000, Cynthia Lawford offered a biographical reading of Landon’s poetry in the London Review of Books, although she acknowledges that “[the poet’s] talk of ‘the broken heart, the wasted bloom, /The spirit blighted, and the early tomb’ should not be taken too literally” (36).

The quivering heroine and her props—weeping roses, mournful harps, and dewy boughs—that appear in so many of Landon’s poems are certainly compelling figures, whether we appreciate or disparage them, and, they merit our attention and a closer look. However, rather than approaching these conventions of sensibility as signs of Landon’s personal subscription to the “Burkean-Rousseauian categories of the beautiful and domestic” (Mellor 1993, 110), I propose we perceive them as manifestations of Landon’s sophisticated—often staged—manipulation of poetic forms and tropes that display her own canny ability to capitalize on literary rhetoric.

Indeed it is the very excessiveness of these figures that points to a radically new reading of Landon’s poetry. If “The Improvisatrice” is Landon’s signature poem (and her signature heroine), I would like to challenge its most popular interpretation, which claims that because Landon wrote a lengthy first-person poem about a woman who writes wildly popular, extemporaneous, free-flowing verse, but loses her artistic power and dies after suffering rejection by her lover, the author, like the Improvisatrice herself, must believe that romantic heroes and erotic love are dangerous to women, often fatally so.[1] Even this brief gloss, however, suggests an alternative reading of the work: erotic pleasures are contingent on the power of literature, and women, Landon suggests, find pleasure and power in reading and writing erotic narratives. This lesson becomes even clearer when we read “The Improvisatrice” in the context of a few of the other poems that accompanied its initial appearance.[2]

The collection, The Improvisatrice; and Other Poems, speaks volumes about the power of language and displays Landon’s prodigious creative gifts, her ironic self-consciousness, and her savvy marketing skills. If the text offers one version of the poet as the suffering sentimental heroine in the person of the title poem, it also proffers an image of a clever, self-aware, literary capitalist who creates, addresses, and fulfills her early nineteenth-century audience’s desires and inspires her readers to yearn for more. When we read more of Landon’s poetry than her signature piece, we are able to appreciate another facet of her poetics: the ability to display and to capitalize on the narcissistic pleasures of reading. I would like to offer a new reading of Landon’s work—not as the product of “a charming innocent girl overflowing with spontaneous feeling” or of a “money-grubbing cynic dedicated only to exploiting the too tender sensibilities of gullible readers” (Blain 43)—but as the work of a woman poet well versed in literature, whose art complicates our conceptions of the conventions of sensibility.[3] When we read across the volume of The Improvisatrice; and Other Poems, we see that Landon shows her readers that “love” is about erotics, that erotics is about literature, and that women can only safely explore erotics in literature, and in her literature in particular.

The front matter of the original volume serves as a visual introduction to and a fitting emblem of the text to follow. As a poetic package marketed for consumption, the visuals reflect the rhetorical operations within the poems themselves. The frontispiece, a full page engraving, in form and content, evokes Eve’s temptation, while an epigraph from one of the many “sub-poems” of “The Improvisatrice” appears beneath it (See figure 1). The diaphanous-clad woman reaches for “unholy herbs” from a sinister-looking man whose lack of clothing is compensated for by the presence of a large serpent. Elements of Charles Heath’s engraving come straight out of gothic literature: the angelic heroine, the evening setting, the nearly hidden owl, the partially clothed male. The caption below the illustration reads:

lines 650-653, McGann, ed., 64-5THE IMPROVISATRICE

He heard her prayer with withering look;

Then from unholy herbs he took

A drug, and said it would recover

The lost heart of her faithless lover.

When we come to the poetic passage again within the volume, the “wizard of the dell” is rendered quite differently from the engraving. Landon writes:

640-647, McGann, ed., 64. . . On that face

Was scarcely left a single trace

Of human likeness: the parched skin

Shewed each discoloured bone within;

And but for the most evil stare

Of the wild eyes’ unearthly glare,

It was a corpse, you would have said,

From which life’s freshness long had fled.

Heath may have accurately captured “the wild eyes’ unearthly glare,” but he ignores “the parched skin,” “discoloured bone,” and general corpse-like nature of the figure. The engraver (following a drawing by T.M. Wright) misrepresents the scene in the poem (itself only a brief moment in one of several songs that the Improvisatrice sings) to present an erotic gothic image.

Figure 1

With all of the scenes available—many of them more important than this one—why is this the frontispiece? Two possibilities come to mind: either the printer recognizes the popularity of gothic literature and sells Landon’s volume as an example of it; or the image interprets or rewrites the passage. While the epigraph indicates that the woman is purely motivated, the illustration puts her in a more compromising position. The engraving suggests that “The Improvisatrice” is a gothic re-telling of Paradise Lost, the familiar story of feminine temptation given a new twist, piquing the reader’s interest with the confusion of provocation.

Although the title of the work is clearly presented on the page facing the frontispiece, the letters “L.E.L.” dominate the page. Positioned to sell the volume, the three letters of the author’s name are lavish, delicate, excessively curlicued.[4] The codes evoked by the typestyles and the engraving anticipate the text proper, showing that the tales that follow are gothic, erotic, feminine, and allusive. Just as importantly, they introduce “L.E.L.” herself as another “type,” a “poetess” who “personifies a femininity of such single purpose that she appears almost to collude in her own objectification” (Blain 41).[5]

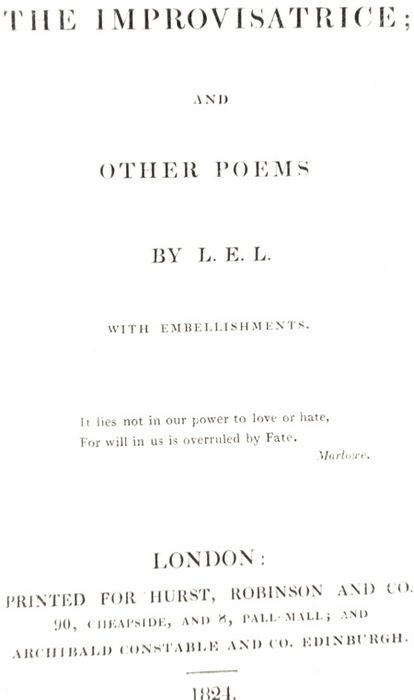

The title page that follows the first is less ornate, and again emphasizes Landon’s status as the volume’s creator and the title work’s status as a poem, one of many literary productions (See figure 2). Both title pages underscore that the literary works are products of “L.E.L”’s imagination. Yet the presentation of the author’s initials differs, for if the first “L.E.L.” is a charming poetess of Eros, the second offers another identity for the writer as a professional poet of letters, anticipating the twentieth-century debate about what a woman poet is.[6] In any case, “L.E.L.”—no modest anonymous “lady”—is clearly presented as the volume’s creator.

Figure 2

Indeed the page even proffers of a visual echo of the author’s name in the words under the title, “With Embellishments.” These “embellishments”—afterthoughts or additions—might be supplemental images or words, but the phrase aptly characterizes the signature mark of “L.E.L.”—itself a symmetrical formulation that exudes artifice and a sense of constructedness. “Embellishments” might refer to the engravings, to the epigraphs, or to the shorter poems that are embedded Chinese-box style within the title poem, and “L.E.L.” thus invites us to see her poems as carefully crafted, embellished, allusive works of art; but through this poetics of embellishment Landon spells out the romantic codes at work in her text and in the world, at the same time that “L.E.L.” underscores their marketability.

The first embellishment that appears on the page is an epigraph by Christopher Marlowe (named for the reader) from the epic poem “Hero and Leander” (unidentified): “It lies not in our power to love or hate, / For will in us is overruled by Fate.” Throughout Landon’s volume, many of the female characters fall in love with their ethical inferiors, and Marlowe’s epigraph might be chosen to highlight that the women are not to blame for falling in love with men unworthy of them; yet knowing readers would recognize that the epigraph is from a lengthy erotic poem that concludes in a blissful post-coital morning; Landon cleverly evades naming Marlowe’s title. So if on one level the epigraph appears to commiserate with women who are powerless in the face of love and fate, on another level it slyly alludes to a sixteenth-century celebration of sex. Landon, the guileless poetess and the witty, well-versed writer, fishes with two rods here.

The collection’s front matter thus illuminates the collective lesson of The Improvisatrice; and Other Poems: an appreciation—naïve or sophisticated—for literature, especially erotic literature, especially by Landon; indeed, Landon’s text functions as a promotion for the unparalleled powers and joys of poetry. So it is not altogether surprising then that Landon prefaces her volume with an “Advertisement.” She writes:

Poetry needs no Preface: if it do not speak for itself, no comment can render it explicit. I have only, therefore, to state that The Improvisatrice is an attempt to illustrate that species of inspiration common in Italy, where the mind is warmed from earliest childhood by all that is beautiful in Nature and glorious in Art. The character depicted is entirely Italian,--a young female with all the loveliness, vivid feeling, and genius of her own impassioned land. She is supposed to relate her own history; with which are intermixed the tales and episodes which various circumstances call forth. Some of the minor poems have appeared in The Literary Gazette.

Once again, Landon does not pass up the opportunity to sign “L.E.L.” The advertisement is the only introduction given to the volume. In addition to referring elliptically (and perhaps ironically) to Wordsworth’s 1802 “Preface to Lyrical Ballads,” Landon also alludes to Madame de Staël’s Corinne; Landon treats the novelist just as she treats the poet, echoing their ideas without acknowledging the writers themselves.[7] Landon thus presents herself as au courant writer entirely conversant with literary tradition, and she implicitly flatters her readers by assuming they do not need literary names identified for them either. Nonetheless, the poet emphasizes her own creation’s originality as well as her inspiration: “the mind of [the Improvisatrice] has been warmed by all that is beautiful in nature and glorious in Art. The character depicted is entirely Italian,--a young female with all the loveliness, vivid feeling, and genius of her own impassioned land.” Landon combines her natural imagination with de Staël’s art to create a new heroine, even as the passive voice belies the poet’s role in the act of creation. But the frequency with which the letters “l” and “e” occur in this passage suggest she is playing a signatory sound game with the reader; “L.E.L.,” a new literary character, hovers at the margins, the homophonics allowing the poet to assert her own presence quietly.

Landon reasserts her authority in the concluding sentence: “Some of the minor poems have appeared in The Literary Gazette.” If the verb tense suggests the poems have somehow magically appeared by themselves, the announcement of the very real Literary Gazette implies something different: poems are not ethereal phantasmagoria but concrete objects—commodities that people have seen, bought before, and can buy again.[8] So, the literary project for Landon is explicitly self-promoting (if reliant on the work of others); Landon consistently hints that literature is a business with multiple products for sale that can tantalize and satisfy while she also positions herself as an “honest” (because overt) marketer of verse.

In the complex and multi-layered The Improvisatrice; and Other Poems, Landon not only borrows literary characters, styles, and images from Marlowe, Wordsworth, and de Staël but from Sappho, Milton, Shakespeare, Dryden, Pope, Smith, Byron, Shelley, and, of course, herself as well.[9] Landon employs these echoes to encourage the reader to keep reading that which the reader recognizes and likes and so to keep the writer in business; the poet’s gift lies in her recognition of the power and pleasure of literary codes and her capitalizing on their applications.[10] She is a woman of letters who capitalizes (literally) on her literary culture, by embellishing various forms of writing already in circulation.

Thus when we begin to read “The Improvisatrice,” and do so in the light of even of a few of her other poems, we see that Landon sells her audience on a safely self-indulgent reading practice: she suggests that her readers seek gratification in the intimacies of a book’s words. Through the display of the erotic signs of physical bodies, the poems show readers that desire can be fulfilled by reading literature even as literature constructs those desires. Landon’s tome serves two purpose: to provide her readers with a safe mode of erotic gratification and to keep them desiring more poetry (keeping the poet’s own work in demand): by warning her readers against interpersonal erotic relationships, she serves them sensuality in a monitory package.

To appreciate Landon more fully, we must recognize her literary devices as rhetorical maneuvers conscientiously employed and not mistake them for her own earnest assertions. The suffering woman may not be a sign of Landon’s despair or of her belief in the veracity of the literature of sensibility, but a figure she uses as a means to an end. While critics have generally focused on Landon’s submission to literary codes, I read Landon as manipulating those codes and figures—their ubiquitousness is a mark of Landon’s self-consciousness of her status as a writer. Landon’s heroines are not “powerless to prevent . . . suffering [caused by men]” (Mellor, 1993, 117), but they have been seduced by the powers of literature, and while Landon celebrates those powers in her verse, she also warns her readers not to read romance as reality. Stephenson correctly observes that “despite the alleged speaking from the heart, the feelings of which [Landon] speaks seem just as likely to have been appropriated from other literary texts” (1995, 122). Indeed the intertextual appropriation acts to inspire desire in Landon’s readers and to tell them where they can look for it to be fulfilled: the satisfaction is not in real life, but in letters, which in Landon’s world promise expectations that life can never meet. Landon further underscores that artifice is valuable, desirable, and pleasurable with the number of artists—poets, musicians, and painters—that populate the volume.

The most important of these figures is of course “The Improvisatrice,” who, unlike her creator, never names herself. She narrates 102 of the 105 pages of the poem, singing no fewer than six songs about women who die shortly after falling in love with men, but not before their desire, at least momentarily, incarnates, empowers, and memorializes them; before her own death, the Improvisatrice too falls in love with a man who unwittingly betrays her. But while her own story echoes those of the women of whom she sings, we must be careful to distinguish the characters the Improvisatrice creates from the Improvisatrice herself (a maneuver we must studiously observe in our analysis of Landon as well).

When the Improvisatrice introduces herself at the beginning of the poem, she establishes her identity as an artist and a performer:

1-5, McGann, ed., 51I AM a daughter of that land,

Where the poet’s lip and the painter’s hand

Are most divine,--where the earth and sky,

Are picture both and poetry—

I am of Florence.[11]

The loyal daughter values her homeland not for its political history but its creative legacy;[12] it is Florence that deifies its poets and painters, and its poets and painters, in turn, make the nation-state—its earth and sky—the subject of their work.[13] This symbiosis underscores the importance of artistic production; earth and sky are valuable not in and of themselves but because they serve as subjects for “picture both and poetry”: nature, thus, serves as inspiration for art, which embellishes and surpasses its source.[14] The Improvisatrice’s appreciation of artifice is partially self-serving, since she, too, is an artist and if “songs whose wild and passionate line /Suit . . . a soul of romance like [hers]” (23-24, McGann, ed., 52), she creates similar songs, which instill in her audience a desire for romance and for art, not for the humdrum (natural) vagaries of daily life, but for fantastic pleasures that only art can portray.

“Pour[ing] forth [her] full and burning heart / In song” and making her “dreams of beauty visible” on canvas (28-30, McGann, ed., 52) gives the Improvisatrice great pleasure, but, as she relays to the reader, it is when others recognize her talent that her excitement grows most heated: “Oh, yet my pulse throbs to recall, / When first upon the gallery’s wall / Picture of mine was placed, to share / Wonder and praise from each one there” (33-36, McGann, ed., 56). The Improvisatrice is an artist before she is a heroine of sensibility; it is art that is crucial to her pleasure. In portraying the Improvisatrice as titillated by her artistic creations and others’ reactions to them, Landon explores the voyeuristic erotic pleasures of art; through her heroine, the poet shows her readers how to view and to react to her own artistic productions.

The Improvisatrice’s subjects are chosen carefully: Petrarch and Sappho reign over her imagination and her canvas. Landon writes of a woman who paints poets, whom she memorializes as the great teachers of love; by painting Petrarch and Sappho, the Improvisatrice pays homage to the poets’ production, but through her own medium. Through her own valorization of other literary works—her embellishment of them—Landon teaches her audience to valorize literature; the next step for the reader is to valorize Landon. By playing with genres, by writing a poem about a woman who paints poets, Landon subtly aggrandizes her own art. With her paintings of Petrarch and Sappho, the Improvisatrice displays Landon’s insight that art can inspire and fulfill desire. As the poem continues, the Improvisatrice will also come to embody Landon’s warning: do not go looking for the romance of literature in real life. A figure like Petrarch appears in the Improvisatrice’s dreams and her demise will come when she believes that she encounters such a man in actuality. Romance, Landon underscores, is the stuff of art.

Sappho inspires the first distinct shorter poem in the greater narrative as well as the Improvisatrice’s painting. As Sappho, the Improvisatrice sings:

149-52, McGann, ed., 56It was my evil star above,

Not my sweet lute, that wrought me wrong;

It was not song that taught me love,

But it was love that taught me song.

“Sappho’s Song” is original to the Improvisatrice; but if love teaches her Sappho to sing, it is Sappho’s songs that have taught the Improvisatrice to love—or so the Improvisatrice thinks at least. For before she meets the object of her affections, she is painting pictures and singing songs of artists who longed for love and suffered when they couldn’t obtain it. Rendering these artists’ erotic feelings stimulates the Improvisatrice. If her “pulse throbs to recall” the display of her first painting, she grows more excited yet after narrating Sappho’s song:

185-90, McGann, ed., 57As yet I loved not;--but each wild,

High thought I nourished raised a pyre

For love to light; and lighted once

By love, it would be like the fire

The burning lava floods that dwell

In Etna’s cave unquenchable.

Stimulated by Sappho’s and Petrarch’s poems, the Improvisatrice mistakes these erotic feelings for the imminence of love. While the heroine believes that literature has taught her love, her body displays a different lesson: literature has taught her desire. Literature has scripted the Improvisatrice’s physical reactions, and Landon’s poetry metaphorically spells out the graphic manifestations of desire. Although the Improvisatrice thinks she is ready for love, Landon suggest her character is ready for more erotic literature. Indeed the heroine needs no seducer; catalyzed by her own reading in love letters, she already experiences autoerotic pleasures, the kinds that keep both purveyors of pornography and producers of poetry in demand.

Desire is also, for the Improvisatrice, oddly fruitful; her sensuality inspires her to song, which in turn treats desire. She sings four songs alone and two in public, and while the public performances indicate the Improvisatrice’s desirability (for others are attracted to her explorations of sensuality), the private performances suggest that desire can be a solipsistic pleasure. Landon’s reader spies on the heroine’s narcissistic sensuality, and in this voyeuristic act learns to stimulate herself, just as the Improvisatrice does.

For example, as the Improvisatrice meditates alone one night, the scents “from rose and lemon tree” (200, McGann, ed., 57) inspire her to compose extemporaneously “A Moorish Romance,” the second distinct poem included in the narrative. The heroine of the poem is imprisoned by her father who wants her to marry a man of his choosing, although she is already in love with someone else. To avoid the arranged marriage, she runs away with her lover; the two embark on a ship before drowning in a storm.[15] The heroine’s name, “Leila,” is the most interesting element of the Improvisatrice’s tale. Like Petrarch and Sappho, “L.E.L.” also appears in the Improvisatrice’s verse; but unlike the earlier poets, the embellished L.E.L. does not appear as herself (a young English woman), but as an exotic, daring lover (and as an echo of one of Byron’s literary creations). It is not just literature, but desire that links “Leila” to the Improvisatrice’s other models, Petrarch and Sappho, whom the Improvisatrice had earlier memorialized as victims of love. By appearing to privilege the desire of Petrarch and Sappho over their literary work, Landon does not appear as self-promoting as the grouping “Petrarch, Sappho, and ‘Leila’” actually suggests.

Although the Improvisatrice begins to sing the song of Leila to herself, by the time she stops, a number of captivated fans have collected to listen to her. Among them is the beautiful young Lorenzo, silent and spellbound by the Improvisatrice who in turn is fascinated by him. His beauty, however, does not move her to approach him, but, somewhat strangely, to approach herself:

463-76, McGann, ed., 70I heard no word that others said—

Heard nothing, save one low-breathed sigh.

My hand kept wandering on my lute,

In music, but unconsciously

My pulses throbbed, my heart beat high,

A flush of dizzy ecstasy

Crimsoned my cheek; I felt warm tears

Dimming my sight, yet was it sweet

My wild heart’s most bewildering beat,

Consciousness, without hopes or fears,

Of a new power within me waking,

Like light before the morn’s full breaking.

I left the boat—the crowd: my mood

Made my soul paint for solitude

Following her readings in and representations of Petrarch and Sappho, the Improvisatrice encounters Lorenzo, and she responds to him the same way she does to erotic literature: sublimating her desire in song. Instead of running off with Lorenzo (as Leila would have done), the Improvisatrice leaves the crowd because her mood “made [her] soul pant for solitude.” Our heroine is more caught up in her own exploration of sensuality (her wandering hand, her throbbing pulse, her beating heart, her crimsoning cheek, her warm tears, her panting soul) than in its immediate catalyst.[16] Since the premise of traditional love poetry (including Petrarch’s) is longing for one’s object of desire (also the first law for successful capitalism), then it is imperative that the beloved retreats from the lover. Landon’s scene spells out the irony of the romance tradition: love affairs blossom when the characters only see each other from afar and through the lenses of literature.

Rather than pursuing Lorenzo, the Improvisatrice retires to sing love songs to herself. With this portrayal of the composing process, Landon explores how love poetry celebrates behavior that is on one level inherently narcissistic. The Improvisatrice proceeds to compose a poem about love, infidelity, and death.[17] And just as she does not see the irony in her own treatment of her “love,” neither does she see the irony of her songs. On seeing Lorenzo, she is not inspired to epithalamions, but to songs of unfaithfulness; even so, she fails to realize that Lorenzo may be guilty of the same flaws her heroes are. The Improvisatrice is as naïve as her heroines.

But the Improvisatrice’s lack of self-consciousness points to Landon’s possession of it. Landon’s heroine sings of love lost with no insight into her own situation because she is so enchanted with romance that she does not see the object of her affections clearly. Through the example of the Improvisatrice, Landon shows her readers that they too can get caught up in the pleasures of literature, but that literature warns them of the very real dangers of love. Reading literature, Landon implies, is a safer pleasure than the ones men offer; but even though real-life “love” is dangerous, writers offer pleasure that does not kill. She advocates onanistic poesaphilia as a prophylactic against real-life ruin.

Deaf to the lesson, the Improvisatrice claims that although she and Lorenzo do not exchange words,

965-68, McGann, ed., 71I loved him as young Genius loves,

When its own wild and radiant heaven

Of starry thought burns with the light,

The love, the life, by passion given.

Certainly by this point in the poem we must entertain the idea that Landon is creating a parody of conventional love poetry. “Love,” for the Improvisatrice, is a solipsistic experience: it demands a literary catalyst, and is then self-sustaining. Whereas the Improvisatrice makes the mistake of abandoning literature and trying to love in her own life, Landon reveals “love” to be a self-delusive desire for erotic gratification scripted by poets. Landon shows that if one abandons literary lovers, she will suffer the fate of naïve heroines: readers are better off with books.

Careful readers cannot therefore be surprised when in a lonely stupor the Improvisatrice heads to a cathedral at night and witnesses the wedding of Lorenzo to another young woman, a scene McGann and Riess omit. Unlike the reader, the heroine is shocked. For the Improvisatrice has carefully scripted her fate—that of literary heroines who dare to love. The denouement is once again upon us. Despondent, the Improvisatrice relays:

1321-24, McGann, ed., 77Rust gathered on the silent chords

Of my neglected lyre,--the breeze

Was now its mistress: music brought

For me too bitter memories!

In spite of her angst, she claims, “I pleased me in this desolateness, / As each thing bore my fate’s impress,” savoring her self-destructiveness (1327-28, McGann, ed., 77). Moved by her own plight, the Improvisatrice sketches herself as Ariadne:

13333-42, McGann, ed., 77-8I drew her on a rocky shore:--

Her black hair loose, and sprinkled o’er

With white sea-foam:--her arms were bare

Flung upwards in their last despair.

Her naked feet the pebbles prest;

The tempest-wing sang in her vest:

A wild stare in her glassy eyes;

White lips, as parched by their hot sighs;

And cheek more pallid than the spray,

Which, cold and colourless, on it lay:--.

Capitalizing on cultural codes to make the most out of her own rather pathetic story and overwrought grief, the Improvisatrice aligns herself with the classic tragic figure of abandonment. Just as literature has taught her love, so has it taught her despair, scripting her demise. For although Ariadne was eventually rescued by Bacchus, in the Improvisatrice’s post-classical world, there is no savior. And perhaps because of this, the description of Ariadne’s bare arms, naked feet, and wild stare is loving, lingering; the Improvisatrice knows the part that she wishes to play and she gives vent to her emotions in a creative project that is a testament to them at the same time that she ennobles herself as a mythical heroine.

After a long absence, Lorenzo returns to the Improvisatrice, claiming, “I’ll only tell thee that the line / That ever told Love’s misery, / Ne’er told of misery like mine!” (1444-46, omitted from McGann, ed.,). The reader knows otherwise—after all, the Improvisatrice has been telling of love’s misery since the poem began. Lorenzo’s tale is not surprising: betrothed since childhood to a family friend, he falls in love with the narrator after hearing her improvise. Committed to honor, he marries Ianthe, who conveniently falls sick; after the death of his bride, Lorenzo returns to the Improvisatrice, imploring her to “Smile, sweet love! [For] our life will be / As radiant as a fairy tale! / Glad as the sky-lark’s earliest song-- / Sweet as the sigh of the spring gale” (1485-88, omitted from McGann, ed.). He is correct on a few counts. Their affair will resemble the skylark’s song and a spring breeze, but only in terms of longevity. Like the Improvisatrice, Lorenzo is misled, confusing reality with fiction. Landon shows that real-life experiences will inevitably leave one longing for the safe pleasures of literature, the pleasures that books such as The Improvisatrice; and Other Poems can supply.

Soon after Lorenzo returns, the Improvisatrice dies, but not before pronouncing,

1517-1530, McGann, ed., 79It is deep happiness to die,

Yet live in Love’s dear memory.

Thou wilt remember me,--my name

Is linked with beauty and with fame.

The summer airs, the summer sky,

The soothing spell of Music’s sigh,--

Stars in their poetry of night,

The silver silence of moonlight,--

The dim blush of the twilight hours,

The fragrance of the bee-kissed flowers;--

But, more than all, sweet songs will be

Thrice sacred unto Love and me.

Lorenzo! Be this kiss a spell!

My first!—my last! Farewell!—Farewell!

On her deathbed, our heroine continues to savor narcissistic pleasure; her only thought for Lorenzo is that he remember her name. Her assurance in this fact distinguishes her from her creator, who knows that it is the one lesson the reader cannot possibly remember since she never learned it in the first place (although the last two lines—“spells” and “farewells”—echo their meta-textual creator’s name). The sentimental heroine is dying once again, leaving the reader trembling, and the echoes of “L.E.L.” hanging in the air.

With the Improvisatrice’s death, of course, a new speaker must take over the narration of the poem. Like the Improvisatrice, this speaker is not named. In a smart, convincing reading, Harriet Linkin argues that the anonymity of the second speaker coupled with the lack of “logical framework that accounts for the improvisatrice’s portion of the narration” (178) is a daring move on Landon’s part in which she “seizes authorial control to contrast her subversive efforts with the improvisatrice’s adherence to conventional ‘woman’s power’. . . . Landon as poet frames her construct to reveal it as construct” (179). Landon uses the Improvisatrice to expose love poetry as a lesson in self-infatuation. This new speaker’s sex is not revealed to us, though we learn the canny traveler is wandering “through Italia’s land,” and happens upon refuge one night at the home of a despondent Lorenzo:

1545-48, McGann, ed., 80. . . . he was young,

The castle’s lord, but pale like age;

His brow, as sculpture beautiful,

Was wan as Grief’s corroded page.

A self-indulgent depressive, he has strangely incorporated the techniques of the Improvisatrice, actually becoming the stuff of art (“as sculpture beautiful”) and of literature (“as Grief’s corroded page”). Lorenzo’s body, a living memorial, displays how literary and artistic codes have shaped his existence.

The new narrator stays in Lorenzo’s home taking stock of his art collection, examining one portrait in particular:

1571-76, McGann, ed., 80She leant upon a harp:--one hand

Wandered, like snow, amid the chords;

The lips were opening with such life,

You almost heard the silvery words.

She looked a form of light and life,--

All soul, all passion, and all fire;

Is it Sappho? The Improvisatrice? The Improvisatrice as Sappho? Whether or not Lorenzo has painted the portrait himself or has commissioned it (and it is unclear in the text), he has recognized the power of the artist to use another’s work as a catalyst for his own production, for next to the picture stands a funeral urn,

1582-86, McGann, ed., 80-81. . . on which was traced

The heart’s recorded wretchedness;--

And on a tablet, hung above,

Was ‘graved one tribute of sad words—

‘Lorenzo to his Minstrel Love.’

Lorenzo has not so much remembered the Improvisatrice’s name, as he has learned from her how to refer to artists, and to take credit for their work. He has ignored her dying wish, another example of the irony rife within this “love” poem, defying her self-representation as Ariadne to paint her as a triumphant beauty, and naming himself but not his beloved in the tablet. In championing a deceased woman, he has adopted the position of romantic authority by championing his own love for her. His own vessel is empty though, containing only the ashes of the Improvisatrice. Unlike the Improvisatrice, who used Petrarch and Sappho as inspiration for her own work, Lorenzo cannot actually create a narrative; he may attempt to tell a fairy tale, but falls short when it comes to telling the full story, ending with the title, where the title would actually begin.

Landon concludes the poem with those words, that title, “‘Lorenzo to his Minstrel Love.’” By ending the poem with a title, she refers back to the beginning of the poem and suggests that the entire work is Lorenzo’s tale. But if the title also refers to the Improvisatrice’s ashes, then Landon may comment that all poetry is ashes—remnants of others’ work. “The Improvisatrice,” as Linkin observes, is ironically self-conscious about the power of reading and the power of writing.[18] For with the poem’s elusive ending, Landon forces her readers out of mere emotional identification with the characters into the realm of puzzlement, wondering what exactly they have just read and what lies ahead. Since the first poem in the volume underscores its own artifice, Landon implicitly asks that we see the subsequent poems as allusive, embellished, artistic productions.

The section immediately following “The Improvisatrice,” “Tales and Miscellaneous Poems,” includes eleven poems spanning over one hundred pages. Five of the eleven poems (“Rosalie,” “Roland’s Tower,” “the Bayadere,” “The Minstrel of Portugal,” and “The Basque Girl and Henri Quatre”) treat the now-familiar subjects of abandoned or dying lovers. Rosalie elopes with Manfredi who abandons her; she returns home to find her mother dead. Roland accidentally kills his lover’s father in battle; she joins a convent and dies; he dies shortly thereafter. Aza is in love with a god masquerading as a human who dies; she performs suttee, but joins him after death in godhead status. The Minstrel of Portugal is in love with Princes Isabel; her father banishes him; Juan dies in exile; Isabel never marries and dies at the same hour Juan does. The Basque Girl is in love with Prince Henri who abandons her; she carves “Adieu Henri” on a tree and drowns herself.

Plot aside, the most remarkable feature of this group is that each poem contains a poet or poetess figure: Rosalie plays a mandolin; Isabelle of “Roland’s Tower” plays the lute and sings; the Bayadere is a musician; the Minstrel of Portugal immortalizes his love for Princess Isabel in song; even the Basque girl inscribes her love for Prince Henri into a tree. All of the characters recognize the lures of artistry and of narrativizing their love. No behind-the-scene stage managers, Landon’s artists are creators and star attractions both. The production of poetry is romantic and glamorous, and being entertained, for Landon’s audience, consists in reading about people writing erotically.

Thus we see again the mark of Landon’s literary self-consciousness. She highlights this awareness by playing with the narrators of the poems. As in the play with narrators in “The Improvisatrice” (beginning with one but ending with another), so in “Tales and Miscellaneous Poems” does Landon often begin with one narrator who introduces the poem and then disappears, not to be heard from again. This device once again emphasizes the artifice of Landon’s production: at the same time that she creates characters who speak passionately and eloquently from the heart, she announces that they are literary characters.

For example, the first poem in “Tales and Miscellaneous Poems,” “Rosalie,” begins,

1-9’Tis a wild tale—and sad, too, as the sigh

That young lips breathe when Love’s first dreamings fly;

When blights and cankerworms, and chilling showers,

Come withering o’er the warm heart’s passion-flowers.

Love! Gentlest spirit! I do tell of thee,--

Of all thy thousand hopes, thy many fears,

Thy morning blushes, and thy evening tears;

What thou hast ever been, and still will be,--

Life’s best, but most betraying witchery!

“’Tis a wild tale” announces a literary venture, and Landon underscores the literariness of her project through images and metaphors. “Blights and cankerworms, and chilling showers” are the stuff of literary love as are “morning blushes” that turn to “evening tears.” If we find such objects in our own lives, we hardly describe them in so lyrical a fashion. Love’s “witchery” is due to language, to literature. For Landon, words create love in spite of the overwrought “Oh, silence is / Love’s own peculiar eloquence of bliss” (43-44); her own work says differently. Rosalie’s after all, “is a common tale:-- / She trusted, --as youth ever has believed; -- / She heard Love’s vows—confided—was deceived” (136-38). Landon does not include a transcription of the events between Manfredi and Rosalie because readers already know what happened. What is important for Landon is stressing the literariness of their love, with two ends in mind: to warn of the dangers of real-life love and to sing of the pleasures of literary love. If turning to Manfredi in real life will being sorrow to a young woman, than turning to Landon’s Manfredi (or to Byron’s Manfred) will bring pleasure.

Landon makes similar interventions throughout the other poems. In “Roland’s Tower,” she notes, “I do love violets: / They tell the history of women’s love” (18-19); the inspiration for “The Bayadere,” she tells us, “was a poem of Goethe’s” though she is ignorant of German herself; in “The Minstrel of Portugal,” she claims “a poet’s love / Is immortality!” (66-67); and after narrating in third person the story of “The Basque Girl and Henri Quatre,” she claims, “I learnt the history of the lovely picture” (58). This vacillation in voices might appear clumsy because it is an unusual poetic device, but it also indicates Landon’s self-promotion not as a heroine of sensibility but as a candid, savvy reader and writer of literature, who needs to comment, to make her presence known. She has created these poems, just as she created “The Improvisatrice.”

Furthermore, Landon exposes conventions as conventions in the notes that accompany two of the poems of the penultimate section of the volume, “Fragments.” “Manmadin” portrays “The Indian Cupid” as he floats down the Ganges and proclaims the power of love in a poem so effusive it could have been penned by the Improvisatrice. Yet the poem’s power changes when we read the note that accompanies it: “Camdeo, or Manmadin, the Indian Cupid, is pictured in Ackermann’s pretty work on Hindostan in another form.” Love is a fantastic, literary enterprise, and the “Hindostans” are just as deluded by its cultural representations as the British are. The poet draws readers’ attention to artistic representations of love, showing how such representations influence our own perception of the emotion. Indeed the literary codes of love might shape our experience so much that we only recognize its embellishments.

Landon makes a similar move in “The Female Convict,” which, the author’s note tells us, was “Suggested by the interesting depiction in the memoirs of John Nicol, mariner, quoted in the Review of the Literary Gazette.” Once again Landon borrows the kernel of an idea from another writer and embellishes it to create her own work. “The Female Convict” is the subject of the poem, but the speaker is another character, an “I” who is not identified, perhaps John Nicol. The two characters are on a ship and the convict calls to the narrator, pleading, “Take this long curl of yellow hair, /’And give it my father, and tell him my prayer, /’My dying prayer, was for him’” (53-55). If such an event did occur, Landon capitalizes on it. Not only will the father know the daughter’s dying prayer (she is dead by the next morning), but so will all the readers of The Improvisatrice; and Other Poems and of The Literary Gazette (where the poem was first published). Landon turns the prayer into a poem, trading in on the prayers of the dead. Such an action is that of an eager capitalist, and one who recognizes the literary potential of the girl’s deathbed scene.

But the poem in this section that seems the most ironically self-conscious about the profit in literary trade is “Lines Written Under a Picture of a Girl Burning a Love Letter” (McGann, ed., 81). Once again the poet appropriates a piece of art to create her own narrative. The speaker of the poem is a reader who is angry that her lover’s words are lies, and in order to guarantee that they are never read by another, she burns them. Love’s effusions, as Lorenzo also learned, are merely ashes. Although the love letter was filled with “the impassioned heart’s fond communing,” the speaker sees that the words themselves are empty—vehicles to be picked up and used by others. This new speaker represents the space between naïve readers, like the Improvisatrice, and sophisticated ones who appreciate artifice as artifice. Landon’s creation recognizes the writer’s poetic design: to produce love letters that individuals assume are addressed directly to them. Landon herself warns her readers that love letters and love poems should not be interpreted as sincere effusions, but as erotic rhetoric that all can buy, read, recognize, and that some can master.[19]

The poem that concludes the volume and the briefest section of it, “Ballads,” is called “When Should Lovers Breathe Their Vows?.” It is a fitting finale to the volume for it encapsulates the collection’s poetic project. The poem offers readers a list of erotic conventions in the call and response form of the Sunday school primer. The lesson in eroticism claims that there is an appropriate time for lovers to “breathe their vows” and, following the conventions of love poetry, that time is the secrecy of night, in the magic of moonlight. Landon blatantly proffers a manual of literary love. The outright acknowledgment of her text’s purpose borders on the parodic. Love, Landon suggests, is a literary game. What we believe are the signs of love is only the poetic rendering of erotics (“dew[y]” “boughs,” “cold” and “pale” moonshine, “weeping roses,” “bright stars”).

The critical reader recognizes that Landon is ironically exposing the codes that poets have manipulated for centuries. If one’s lover practices particular acts, uses particular props, then one should recognize that that lover is merely following love’s literary handbook, that he has learned the codes Landon and other literary lovers have taught. But the realization that love is a literary game need not be a disheartening one. If love is just erotics masquerading under another name, Landon shows that one can happily, safely, and satisfyingly read love poetry: erotics can be a pleasurable, solipsistic experience; reading and writing embellishments are wonderful pleasures in and of themselves. To avoid ruin, one is better off looking (and paying) for erotic fulfillment not in people but in books.[20] Indeed the only safe lover is a literary lover, one whom the reader can swoon over in ecstasies of conversation, or one whom the reader can shut the book on.

Landon’s contemporaries took her up on her offer. Droves of women (and men) bought Landon’s creations—some perhaps naively and others with a more “experienced” realization of their reading practices. Reading may have provided Landon’s audience with an element of control and an element of pleasure that they lacked in their daily lives and possibly in their erotic relationships. Removed from its original package, taken out of context, “The Improvisatrice” appears to imply that women are doomed to the fates of sentimental heroines. But, if we read it in the context of even a few of its accompanying poems, we recognize Landon’s powerful legacy, not one of capitulation to current stereotypes, but one that smartly employs, plays on, and critiques rhetorical conventions, offering us an example of how at least one early nineteenth-century woman writer could critique literary tradition, explore erotics, and create a demand for her work.

Parties annexes

Remerciements

I am grateful to Tricia Lootens, Laura Mandell, and Yopie Prins for their meticulous critiques of this essay.

Notes

-

[1]

With William Jerdan as her first public advocate, the poet engineered the association between herself and her creation, saying, “I wrote the Improvisatrice in less than five weeks and ruing that time I often was two or three days without touching it. I never saw the MS till in proof sheets a year afterwards, and I made no additions, only verbal alterations” (Watts 21).

-

[2]

I do not have the space here to devote to an extended analysis of the accompanying poems, but many are fascinating and merit further exploration.

-

[3]

Jerome McGann offers a crucial insight in The Poetics of Sensibility where he argues that twentieth-century readers do not know how to read literature of sensibility. I propose that Landon offers a way into appreciating the tradition.

-

[4]

Directly under “L.E.L.” is a small engraving of a European city with the words, “Florence! Fair city of the land / Where the Poets lip and the Painter’s hand / Are most divine.—” [sic], which also serves to distinguish the romantic metropolis from the publisher’s tawdry town. The epigraph is actually a misquotation of the beginning lines of the title poem. Someone is taking a few liberties with “The Improvisatrice.”

-

[5]

Whether Landon herself had control over the production of the volume once it left her hands is doubtful. Therefore, it is much more likely that the publisher chose how the front matter would be presented. Nevertheless, the presentation of the poet here confirms the writer’s self-presentation in the poems that follow.

-

[6]

I would argue that the presentation of Landon in the title pages and the poems that follow deconstructs the dichotomy that Anne Mellor sets up in her article “The Female Poet and the Poetess.”

-

[7]

Various critics have already pointed out Landon’s debt to de Staël. For example, see Greer, Mellor, and Stephenson. Daniel Riess persuasively argues that Landon modifies de Staël’s work to make it more palatable to a conservative English audience by eliminating the crucial scene of Corinne’s coronation.

-

[8]

Riess reads Landon’s “commodity-poems” as a response “to the growing commercialism of the world of art in the late Regency period” (808).

-

[9]

Early reviewers also noted this tendency of Landon’s and did not regard it positively. For example, John G. Lockhart, reviewing the volume in Blackwood’s Magazine noted, “I really could see nothing of the originality, vigour, and so forth, they all chatter about. Very elegant, flowing verses they are—but all made up of Moore and Byron” (299). In 1947, Lionel Stevenson observed, “[Landon] had picked up all the obvious traits from the work of Byron and Keats and Leigh Hunt—ornate descriptions of highly Italianate scenes, tragic episodes in vaguely medieval and renaissance palaces, a morbid enjoyment of melancholy and self-pity” (358). More recently and more approvingly, Daniel Riess commented that Landon’s “poetry is [one] of pastiche, a second-order, synthesized Romanticism carefully shaped and blended” (818).

-

[10]

Byron is certainly Landon’s precursor here in terms of self-promotion and mass marketing fantasies.

-

[11]

The epigraph on the title page beneath the engraving of Florence is a variation on these lines.

-

[12]

The self-proclamation “I AM” recalls the great Romantic male ego (see Mellor and Ross), but the speaker’s power is quickly mitigated with the words “ daughter,” a move not in keeping with the powerful figures created by male poets.

-

[13]

See Sandra Gilbert for an illuminating analysis of the importance of Italy to nineteenth-century women writers.

-

[14]

The appreciation for artifice speaks to McGann’s and Riess’s arguments regarding second-order Romanticism.

-

[15]

Running away with one’s lover generally leads to death for heroines of sensibility. This poem does not appear in McGann and Riess, eds.

-

[16]

Stephenson astutely observes, “the individual male lover is always rather unimportant for Landon’s women; it is the feelings he elicits from the women that are most valued” (1995, 61).

-

[17]

“The Charmed Cup” is the poem that was illustrated so oddly in the frontispiece.

-

[18]

Linkin notes, “Landon’s refusal to station herself as narrator, or to fix the improvisatrice’s narration, opens an unmarked space within which she reserves the right and means to critique the project of masculinist Romantic aesthetics” (180).

-

[19]

I agree with Stephenson that “words are suspect” but not, as the critic claims, “because of their association with men” (1995, 97).

-

[20]

Stephenson notes that in Landon’s work, “men are shown to be nowhere near as exciting, or as satisfying, as words” (1995, 99).

Works Cited

- Armstrong, Isobel. Victorian Poetry: Poetry, Poetics and Politics. London: Routledge, 1993.

- Blain, Virginia. “Letitia Elizabeth Landon, Eliza Mary Hamilton, and the Genealogy of the Victorian Poetess.” Victorian Poetry 33.1 (Spring 1995): 31-51.

- Gilbert, Sandra. “From Patria to Matria: Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Risorgimento.” PMLA 99.3 (March 1984): 194-211.

- Greer, Germaine. “The Tulsa Center for the study of Women’s Literature: What We Are Doing and Why We Are Doing It.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 1.1 (Spring 1982): 5-26.

- “The IMPROVISATRICE, and other POEMS. By L.E.L.” Literary Magnet 2 (1824): 106-109. Rpt. In McGann and Reiss. 294-299.

- Landon, Letitia Elizabeth. The Improvisatrice; and Other Poems. London: Hurst, Robinson, and Co., 1824.

- ———. Selected Writings. Jerome McGann, Daniel Riess, eds. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, 1997.

- Lawford, Cynthia. “Diary.” London Review of Books. 21 September 2000: 36-37.

- Leighton, Angela. Victorian Women Poets: Writing Against the Heart. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1992.

- Linkin, Harriet K. “Romantic Aesthetics in Mary Tighe and Letitia Landon: How Women Poets Recuperate the Gaze.” European Romantic Review 7.2 (Winter 1997): 159-188.

- Lockhart, John G. “Noctes Ambrosianae, no. XVI.” Blackwood’s Magazine 16 (August 1824): 237-38. Rpt. In McGann and Reiss. 298-303.

- Lootens, Tricia. Lost Saints: Silence, Gender, and Victorian Literary Canonization. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996.

- ———. “Receiving the Legend, Rethinking the Writer: Letitia Landon and the Poetess Tradition.” In Romanticism and Women Poets, Opening the Doors of Reception. Ed. Harriet Kramer Linkin and Stephen C. Behrendt. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1999, 242-259.

- McGann, Jerome. The Poetics of Sensibility, A Revolution in literary Style. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.

- Mellor, Anne K. “The Female Poet and the Poetess: Two Traditions of British Women’s Poetry, 1780-1830.” Studies in Romanticism 36.2 (Spring 1997): 261-276.

- ———. Romanticism and Gender. New York: Routledge, 1993.

- Riess, Daniel. “Laetitia Landon and the Dawn of English Post-Romanticism.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900 36.4 (Autumn 1996): 807-827.

- Ross, Marlon B. The Contours of Masculine Desire: Romanticism and the Rise of Women’s Poetry. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Stephenson, Glennis. “Letitia Landon and the Victorian Improvisatrice: The Construction of L.E.L.” Victorian Poetry 30.1 (Spring 1992): 1-17.

- ———. Letitia Landon: The Woman Behind L.E.L. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995.

- Stevenson, Lionel. “Miss Landon, ‘The Milk-And-Watery Moon of Our Darkness,’ 1824-1830.” Modern Language Quarterly 8 (1947): 355-363.

- Watts, Alaric. Alaric Watts, A Narrative of His Life. London: Bentley, 1884.

- Wordsworth, William. William Wordsworth. Ed. Stephen Gill. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Figure 2