Résumés

Abstract

This study examines workplace corruption from the perspective of individual psychological processes. Existing literature has shown how corrupt behaviours can emerge from various kinds of motivations, including manipulation, retaliation, and conformity. This research suggests yet another path, where corruption stems from a motivation to preserve resources that individuals perceive to be threatened by their professional environment. As such, the study is grounded in conservation of resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989, 2001).

We put forward an original model that introduces the notion of resource signals. An enrichment of original COR theory, resource signals correspond to individuals’ perceptions that the work environment is supportive, or, otherwise, of their need for resource development and preservation. Specifically, the study tests a moderated mediation model where a sense of mastery, a personal resource, moderates the impact of resource signals, including distributive justice, procedural justice, and interpersonal trust, on occupational corruption.

Results are drawn from a sample of French public sector employees (n = 575). They validate the hypothesized mediating role of trust between both facets of organizational justice and measures of corruption, including bribery and property deviance. An indirect negative effect, however, is strongest between procedural justice and workplace corruption. As hypothesized, a sense of mastery significantly moderates the link between trust and both corruption types.

This research contributes to both theory and practice. By integrating resource signals within a COR framework, it shows that corrupt behaviours are to be gauged against interacting motivations for preserving psychological resources. Consequently, this study also suggests that organizations should go beyond ethics and procedures, and to consider workplace corruption as a potential symptom of organizational signals perceived as threats to individuals’ valued resources.

Keywords:

- workplace behaviour,

- organizational justice,

- interpersonal trust,

- sense of mastery,

- conservation of resources theory

Résumé

Cette étude examine la corruption au travail sous l’angle des processus psychologiques individuels. La littérature démontre que les comportements de corruption découlent de diverses motivations, tels la manipulation, les représailles et le conformisme. Cette recherche, fondée sur la théorie de la conservation des ressources (CDR, voir Hobfoll, 1989, 2001), propose une nouvelle voie, où la corruption résulte de la motivation des individus à préserver leurs ressources lorsqu’ils les jugent menacées par leur environnement professionnel.

Nous proposons un modèle original qui introduit la notion de « signaux de ressources » (resource signals en anglais). Ce concept, qui vient enrichir la théorie CDR, correspond à la perception des individus quant au soutien offert dans leur milieu de travail ou, sinon, au besoin de développer des ressources et de les préserver. Plus précisément, cette étude teste un modèle de médiation modérée dans lequel le sentiment de maîtrise, une ressource personnelle, modère l’impact des signaux de ressources (justice distributive, justice procédurale, confiance interpersonnelle) sur la corruption au travail.

Les résultats proviennent d’un échantillon d’employés du secteur public français (n = 575). Ils valident l’hypothèse du rôle médiateur de la confiance entre les différentes facettes de la justice organisationnelle et les mesures de la corruption, notamment le soudoiement et la déviance de propriété. Cependant, l’effet négatif indirect de la justice procédurale sur la corruption au travail est plus marqué. Conformément aux hypothèses formulées, le sentiment de maîtrise modère significativement le lien entre la confiance et les deux types de corruption.

Les apports de cette recherche sont théoriques et pratiques. L’intégration des signaux de ressources dans un modèle CDR montre la nécessité d’évaluer les comportements corrompus selon les motivations à préserver les ressources psychologiques. Corollairement, cette étude suggère aux organisations de dépasser le cadre de l’éthique et des procédures afin d’envisager la corruption comme un éventuel symptôme de la perception de signaux organisationnels menaçants pour les ressources individuelles.

Mots-clés:

- comportement au travail,

- justice organisationnelle,

- confiance interpersonnelle,

- sentiment de maîtrise,

- théorie de la conservation des ressources

Resumen

Este estudio examina la corrupción en el lugar de trabajo desde la perspectiva de los procesos sicológicos individuales. La literatura demuestra que los comportamientos corruptos pueden surgir de diversos tipos de motivaciones, como la manipulación, las represalias y el conformismo. Esta investigación, basada en la teoría de la conservación de los recursos (CDR) (Hobfoll, 1989, 2001), sugiere una vía adicional, en la que la corrupción surge de una motivación para preservar recursos que las personas perciben como amenazados por su entorno profesional.

Proponemos un modelo original que introduce el concepto de señales de recursos, lo que constituye un enriquecimiento de la teoría original de la CDR. Las señales de recursos corresponden a las percepciones individuales del ambiente de trabajo, considerándolo favorable o desfavorable a sus respectivas necesidades de desarrollo y preservación de sus respectivos recursos individuales. Más específicamente, este estudio evalúa un modelo de mediación moderada donde un sentido de control, un recurso personal, modera el impacto de las señales de recursos (justicia distributiva, justicia procesal, confianza interpersonal) en la corrupción ocupacional.

Los resultados provenientes de una muestra de empleados del sector público francés (n = 575) validan la hipótesis del rol mediador de la confianza entre ambas facetas de la justicia organizacional y las medidas de corrupción como el soborno y apropiación indebida. Sin embargo, el efecto negativo indirecto de la justicia procesal en la corrupción ocupacional es más pronunciado. De acuerdo con las hipótesis formuladas, la sensación de control modera significativamente el vínculo entre la confianza y ambos tipos de corrupción.

Los aportes de esta investigación son teóricos y prácticos. Con la integración de las señales de recursos en un modelo de CDR se demuestra que los comportamientos corruptos deben ser medidos tomando en cuenta las motivaciones de preservación de los recursos sicológicos y sus interacciones. Como corolario, este estudio también sugiere que las organizaciones deberían ir más allá del marco de la ética y los procedimientos, y considerar la corrupción ocupacional como un síntoma potencial de las señales organizacionales percibidas como amenazas a los recursos individuales valorizados.

Palabras claves:

- comportamiento en el trabajo,

- justicia organizacional,

- confianza interpersonal,

- sensación de control,

- teoría de la conservación de recursos

Corps de l’article

Introduction

Most recent management surveys have indicated that corruption in business matters is viewed as a key `challenge` for companies (Kemp, 2013). For instance, the cost of bribery, a form of corruption, has been estimated to be about $1 trillion worldwide every year (Nobel, 2013) and a serious challenge to democratic processes (Montero, 2018). Furthermore, in addition to the sheer economic burden, corrupt behaviours within organizations have been revealed to directly impact employee morale, productivity and innovation (Serafeim, 2014).

Authors have generally acknowledged organizational corruption as a focused category of workplace deviance (Hollinger and Clark, 1982; Robinson and Bennett, 1995). Also classified as a form of counter-productive work behaviour (CWB), corruption embraces practices that include embezzlement, payment of bribes, kickbacks, graft, and cronyism. These are volitional behaviours on the part of an organization member to extract personal advantages detrimental to the legitimate interests of an organization (Bashir et al., 2011, 2012; Gruys and Sackett, 2003; Mangione and Quinn, 1975). Each one of them is an occupational crime, since they are motivated by a personal benefit illegally obtained from the employer, or from the customer (Clinard and Quinney, 1973).

Standards have been proposed to help and guide organizations in responsible and ethical management (Lindgreen, 2004; Transparency International, 2017; White and Montgomery, 1980). That said, there also remains a need for a better understanding of corruption mechanisms. The following research question is thus proposed: “Why, in full awareness of adverse professional and legal consequences, do individuals choose to engage in malevolent corrupt behaviour?”.

Research on corruption is difficult because the phenomenon is multifaceted, secretive and potentially embarrassing. However, there are cognitive studies that frame workplace corruption within theories such as planned behaviour theory (Gorsira et al., 2018; Rabl, 2011), attraction-retention-attrition theory (Robinson and O’Leary-Kelly, 1998), social information processing theory (Lange, 2008; Robinson and O’Leary-Kelly, 1998), attribution theory (Martinko et al., 2002), social learning theory (Chappell and Piquero, 2004) and, more recently, moral disengagement theory (Moore, 2008, 2009, 2015). Contrasting with these individual approaches, there is research that theorizes corruption from a societal perspective that includes economic, legal, moral, and cultural considerations (Akers, 1988; Fan, 2002; Gopinath, 2008; Judge et al., 2011; Luo, 2008).

The objective of the present study is to bridge both research streams and to develop a perspective of corrupt behaviour that draws from both individual and environmental levels of analysis. The expected theoretical contribution is to integrate corruption within a model that incorporates individuals’ internal dynamics and the working environment [internal world versus meso-world; Dimant and Schulte (2016)]. Specifically, we suggest that corruption corresponds to individuals’ motivation to survive the perceived misfit between valued personal goals and the occupational environment. Following the path of recent developments that link self-preservation to counterproductive behaviours (Mitchell et al., 2018), our study analyzes corruption within a theoretical framework proposed by the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989, 2001), a motivational approach to dysfunctional behaviours in organizations. It explores corruption as determined by an interplay between personal motivational resources and perceived organizational resources signals, including organizational justice and interpersonal trust.

The road(s) to corruption

Corruption relates to serious property mishandling at the organizational level (Robinson and Bennett, 1995). Corruption fits the definition of counterproductive work behaviours (CWB, see Bowling and Gruys, 2010; Gruys, 1999; Kwok et al., 2005; Mangione and Quinn, 1975), which have been defined as a willingness “to acquire or (to) damage the tangible property or assets of the work organization without authorization” (Hollinger and Clark, 1982: 333). Corrupt behaviours include kickbacks, bribes, embezzlement, and nepotism (Bashir et al., 2012; Pearce and Huang, 2014).

In line with accepted CWB taxonomies (Ashforth et al., 2008; Bowling and Guys, 2010; Pinto et al., 2008; Sackett and DeVore, 2001; Spector et al., 2006; Sackett and DeVore, 2001), organizational corruption has been investigated according to the nature of antecedents, e.g. individual and environmental. At an individual level, CWB and corruption have thus been considered an outcome of personality factors (Boes et al., 1997; Salgado, 2002) and negative attitudes (Lefkowitz, 2009). At a macro level, corrupt behaviours have been related to situations associated with a firm’s business and economic environment (Baucus, 1994), job and work-group characteristics (Ashforth and Anand, 2003), organizational climate (Darley, 2005; Stachowicz-Stanusch and Simha, 2013), and organizational control systems (Lange, 2008).

As with other CWB types, corruption involves complex multi-level interplays of personal, social, cultural, and economical factors. Nevertheless, we observe a number of limitations in corruption studies. First, most of them are inscribed within a common stressor-emotional (SE) model (Spector and Fox, 2005). Specifically, corruption is set as an outcome of a cognitive process that integrates interactions between straining situational antecedents and personal emotional reactions (Aghion et al., 2010; Gualandri, 2012). This stimulus-response perspective, however, still leaves open the question of interpersonal variations in appraising the nature of situations, such as the perception difference between men and women with regard to failure of organizational support (Siller, Baden and Hochleitner, 2016). Second, the SE model leaves little room for understanding an individual’s motivation to consciously engage in reprehensible acts. Third, research commonly assumes that corruption is dysfunctional and unethical. Yet, authors have recently challenged what they consider to be too decontextualized and too normative perspective (Pearce, 2015). Advances in evolutionary-based psychology, for example, show that ethically (normatively) sanctioned acts can reveal symptomatic outcomes of adaptive individual strategies (Del Giudice, 2016). In short, individuals feel it is legitimate to engage in corruption when such behaviour does not violate their own ethical norms.

Following from the above, we propose a motivation-based approach for understanding corrupt behaviour. Specifically, we suggest corruption is an outcome of interactions between determinants that correspond to both adverse contextual signals and valued motivational resources.

Model and hypotheses

COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989, 2001) explains human motivation from the perspective of a drive for preservation. Fundamentally, the theory proposes that individual motivation is constrained by the conservation of valued factors, otherwise known as resources, including individual, social, tangible, and symbolic. Consistent with this framework, we propose that the backdrop of organizational corruption corresponds to a conservation strategy. Specifically, corruption corresponds to the fear of losing control of valued motivational resources. For instance, in a context of real, or perceived, job insecurity, we assume that individuals engage in corruption to protect themselves against an anticipated onslaught of potential aggressions such as downsizing and technical unemployment. Corruption is thus considered as a tool for “buying” stability and securing one’s turf.

Valued motivational resources, however, should also be considered within the context of necessary adjustments within the environment. Recent theoretical developments have suggested the relevance of organizational mechanisms that signal opportunities for resource development, or risks for deprivation. Resource signals correspond to individuals’ perceptions that the work environment is supportive and considerate of their need for resource development and preservation (Halbesleben et al., 2014; Valcour et al., 2011). Signals are not personal resources, as their control lies outside of the person. Signals provide environmental cues, favourable or adverse, upon which individuals adjust their strategies to invest for resource development or preservation. Interpersonal trust (Halbesleben and Wheeler, 2015) and organizational justice (Campbell et al., 2013) have thus been tested as resource signals in relation to social support. In the present study, we propose a model (Figure 1) where (dis)trust and feelings of (in)justice are perceived as resource signals that determine an orientation toward corrupt behaviours.

Furthermore, our model enriches the COR-based approach to corruption by exploring the role of motivational resources in relation to resource signals. Specifically, we control for the impact of trust and organizational justice on corruption with a sense of mastery, a prominent personal resource that provides individuals with a sense of control and responsibility over desired outcomes (Antonovsky, 1987). A sense of mastery is expected to moderate the link between resource signals and corruption.

Organizational justice

Organizational justice refers to an individual’s perception of how justly they are treated at work (McCardle, 2007). Empirical findings have highlighted a significant relationship between perceptions of unfair treatment from colleagues and supervisors and unethical behaviours, including corruption and workplace deviance (Ambrose, Seabright and Schminke 2002; Aquino, Lewis and Bradfield, 1999; Skarlicki and Folger, 1997). Individuals who are not satisfied with the perceived fairness of organizational procedures show greater inclination toward violation of organizational norms and subsequent acts of deviance and corruption (Aquino, Lewis and Bradfield, 1999; Lim, 2002).

Organizational justice, however, is a multidimensional construct that includes dimensions of distributive, procedural, interactional and informational justice (Cohen-Charash and Spector, 2001; Colquitt et al., 2001). With regard to the specific issue of corruption, we chose to limit our focus to distributive and procedural justice types. Fundamentally, perception of interactional justice, with which informational justice has been associated (Cropanzano and Molina, 2015), can be understood as an element of procedural justice. Yet, procedural justice refers to explicit policies, practices and procedures, whereas interactional justice relates to more informal and subjective relationships (Simons and Roberson, 2003). Moreover, research has stressed the greater relevance of distributive and procedural justices with corruption (Ambrose, Seabright and Schminke, 2002; Abu Elanain, 2010). We recall that distributive justice refers to the perceived gains, or loss, of organizational resources such as financial rewards, promotions, and training opportunities (Fitz-Gerald, 2002; Nirmala and Akhilesh, 2006). Procedural justice relates to the perception of organizational policies and procedures (Forret and Love, 2008; Greenberg, 1990).

Within a COR-framed analysis, organizational justice corresponds to a perceived state of the organizational environment. An illustration of the internal/meso-world interface model (Dimant and Schulte, 2016), this view signals the extent to which occupational procedures are respected, and allow for the preservation of organizational fairness, a motivational resource. As two specific examples of organizational justice, we propose distributive and procedural justice as resource signals that determine workplace corruption:

Hypothesis 1: Distributive justice correlates negatively with workplace corruption.

Hypothesis 2: Procedural justice correlates negatively with workplace corruption.

Trust

Trust has been defined as “positive expectations regarding another’s conduct” (Lewicki, McAllister, and Bies, 1998: 439). It is an example of a resource signal that facilitates cooperation among team members. It is expected to fuel greater bonding between individuals and, in turn, to create a greater sense of responsibility toward others (Kimmet et al., 1980; Kong, Dirks and Ferrin, 2012). Conversely, a lack of trust can induce perceptions of risk and uncertainty, and trigger behaviours of self-interest (Kelley and Thibault, 1978; Thau et al., 2007). Violation of trust has therefore serious negative implications for the ethical conduct of organizations (Williams, 2006), with direct effects on a collection of counterproductive behaviours, such as fraud and corruption (Thau et al., 2007).

With regard to corruption matters, organizational trust surfaces as a symptom of relationships. Put differently, perceived organizational justice has been identified as a significant predictor of trusting interpersonal attitudes and subsequent organizational performance (Ambrose and Schminke, 2009; Farndale, Hope-Hailey and Kelliher, 2010; Krot and Lewicka, 2012; Saunders and Thornhill, 2003). For instance, organizational justice and good relations between employees were found to facilitate interpersonal trust, with a resulting positive impact on reducing risks and operating costs (Krot and Lewicka, 2012; Saekoo, 2011).

Coherent with our overall COR-based modelling, we consider that the relationship between perceived organizational justice and workplace corruption corresponds to individual perceptions that the working environment ensures, or not, the preservation of interpersonal trust, a valued motivational resource. Consequently, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: As a resource signal, interpersonal trust mediates the negative relationship between organizational justice, including distributive and procedural justice, and workplace corruption.

Sense of mastery

High levels of personal mastery have been found to lead to a broader and deeper sense of responsibility in the workplace (Senge, 2010). Conversely, a depleted sense of mastery fuels organizational deviance (Bennett and Robinson, 2003; Pablo et al., 2007). A lower sense of mastery correlates positively with corrupt acts and unethical behaviours, while lower intentions to cheat correlate with increased mastery perceptions (Sengupta and Mukhopadhyay, 2012; Vohs and Schooler, 2008).

A sense of mastery is fundamentally a socially-dependent motivational resource. It involves a relational risk constrained by the extent to which individuals feel secure about their own social environment (Nooteboom, Berger and Noorderhaven, 1997). Thus, in a context of adverse perceptions, i.e. negative resource signals, a sense of mastery as a personal resource is expected to mitigate effects of deleterious outcomes. Following COR theorizing, a sense of coherence acts as a resource that is expected to alter the negative impact of adverse resource signals. Specifically, we suggest that a sense of coherence attenuates the de-motivational process that leads to corruption. Consequently, we enrich our mediated model of corruption with the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4: A sense of mastery moderates the relationship between trust and workplace corruption.

Figure 1

Theoretical Model of Workplace Corruption

Methodology

Procedure and sample

The focus of this research is corruption in public organizations. The nature of public and private sectors is different. Private organizations pursue a single goal of profit (Farnham and Horton, 1996); public organizations have relatively intangible, vague and multiple goals (Allison, 2012). In public organizations, a large part of corrupt behaviours concerns the delivery of public services and spreads throughout bureaucratic hierarchies. Therefore, we selected our sample from several public sector organizations in randomly different hierarchical positions.

A self-report questionnaire was sent to 2000 public sector employees in France. We know of no study like this in this country while, at the same time, public sector employment stands at one of the highest levels in Europe (88.5/1000 inhabitants; Deschard and Le Guilly, 2017), with a nationwide Perceived Corruption Ranking of 72 out of 100 surveyed countries (World Rank 21/180; Transparency International France, 2018). Individuals were selected in several organizations to complete a questionnaire. Some questionnaires were sent by mail and the rest were handed-out during working hours. Subjects were thoroughly briefed and reassured that the data they provided would be kept confidential. Specifically, completed questionnaires were the sole property of independent researchers, and data, in either aggregated or disaggregated form, were not provided to employers.

The final sample was 575, a return rate of 29%. This response rate stands favourably with regard to the 8 to 37% range for self-report questionnaires on less sensitive topics than workplace corruption, or disseminated through more user-friendly electronic approaches (Schuldt and Totten, 1994; Schaefer and Dillman, 1998). The majority of respondents (55%) were male, with an average seniority of six years in their current organization. Respondents’ age ranges from 25 to 68 years, with a mean age of 39.5 (SD = 10.51). The final sample covers a range of occupations, including accountants (12%), auditors (12%), managers (27%), administrative officers (40%), and supervisors (10%).

Measures

`Workplace corruption` is difficult to measure for two main reasons (Svensson, 2005). First, due to the ethical onus, corruption is most often a taboo issue that thrives under the garb of secrecy. Second, corruption takes different forms. It is an umbrella-notion that covers a number of deviant workplace behaviours (Spector and Fox, 2005). In the present research, we focus on two types of mischief, including reward deviance, i.e. bribery, and property deviance. These illustrate two levels of corrupt behaviours. The former operates at an interpersonal level of exchange, with the target of corruption clearly identified by the perpetrator. In these circumstances, the target refers to an impersonal organization that overpowers the individual. This dichotomy reflects a double ethical standard, where cheating the system is established as subordinate to acting in a way consistent with one’s personal values.

Also dubbed “the essence of corruption” (Andvig et al., 2001: 8) bribery, or reward deviance, is a form of corruption that is most prominent in the literature (Bayart, Ellis and Hibou, 1997; Gorsira et al., 2018; Stachowicz-Stanusch, 2010). It is referred to variously as “kickbacks”, “gratuities”, “pay off”, “sweeteners”, “palms greasing”, “back scratching”, “facilitation payment” (Bayart, Ellis and Hibou, 1997; UK Bribery Act, 2010). Overall, bribery corresponds to payments of some kind with the intention of impressing the recipient in a way favourable to the briber. Bribery is corruption because the recipient knows that such a payment is undue and violates accepted rules and norms. It is, therefore, hidden, not advertised. Granted that what is considered bribery also depends on cultural contexts. A practical distinction between a gift and bribery can be blurry. For example, the line is thin between corruption and meanings of `blat` (also “a favour”, in Russian), and guanxi (that also refers to “networking” in Chinese, see Michailova and Worm, 2003; Yang, 1989). That said, the basic rule of thumb is that there is bribery when individuals knowingly engage in socially/legally reprehensible acts.

For this study, we chose Gbadamosi and Joubert’s (2005) instrument to evaluate reward deviance/bribery for it conveniently, i.e. indirectly, solicits answers on sensitive issues. Sample items on a four-item scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” include: “It is common that individuals pay some irregular additional payments (bribes or tips) to get things done”, “It is common for organizations to pay bribes and tips to get things done”, “If a public official acts against rules, help can be obtained elsewhere”, and “Bribery and corruption is common in your organization”.

Property deviance refers to abuses and the waste of organizational resources. It materializes when individuals obtain and benefit unduly from what the organization makes available. Organizational advantage is sought after through illegitimate entitlement. Embezzlement is a form of property deviance. In the present study, we measure property deviance using a six-point (from never to always), three-item scale developed by Peterson (2002), and further tested in relation to organizational justice by Syaebani and Sobri (2011). Scale items include: “Padded an expense account to get reimbursed for more money than you spent on business expenses”, “Accepted a gift/favour in exchange for professional treatment”, and “Taken property from work without permission.”

`Organizational justice` measurement offers a choice of instruments (Colquitt, 2001; McFarlin and Sweeney, 1997). In our case, we use the scale developed by Moorman et al. (Moorman, 1991; Niehoff and Moorman, 1993), since it has been applied to corruption situations (Allameh and Rostami, 2014). `Distributive justice` corresponds to five items that assess the fairness of different work outcomes, including work schedule, pay level, job responsibilities, and workload. A sample item is, “I think that my level of pay is fair.” `Procedural justice` is evaluated by six items on individuals’ perceptions of fair and unbiased information. As for `distributive justice`, the scale ranges from 1 (“strongly agree”) to 5 (“strongly disagree”). A sample item is, “To make job decisions, my general manager collects accurate and complete information.”

`Trust` was measured using a unidimensional scale developed by Cook and Wall (1980). It comprises twelve items, of which two are reversed, graded from 1 (“strongly agree”) to 5 (“strongly disagree”). The scale evaluates individual opinions on the level of trust and confidence that can be placed in workplace colleagues and management. Specifically, six items assess faith in peers’ and management’s intentions, while six other items assess confidence in peers’ and management’s actions. A sample item is, “Most of my workmates can be relied upon to do as they say they will do.”

`Sense of mastery` refers to a perception of control and expertise, a personal psychological resource. To evaluate a sense of mastery, we use the seven-items scale validated by Pearlin and Schooler (1978). Originally developed to study coping behaviours, it assesses the extent to which individuals generally feel personal mastery over important life outcomes. It comprises seven items ranging from 1 (“strongly agree”) to 5 (“strongly disagree”), five of which are reversed. A sample item is, “I have little or no control over the things that happen to me.”

Results

Preliminary statistics

Means, reliability, and correlation coefficients are presented in Table 1. Cronbach’s alphas validate the internal reliability of all measurement scales, from highest (.87 for procedural justice and trust) to lowest (.68 for property deviance). Correlation results reveal that workplace corruption relates negatively to all independent variables. Conversely, inter-correlations between resource variables are all positive, with a particularly strong significant association between trust and sense of mastery (r = .45, p < 0.01). A lack of significant relationships between property deviance and procedural justice, and between property deviance and trust can also be noted.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics and Variable Inter-Correlations / Sample (n = 575)

Hypotheses testing

We conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to test the measurement model. Reliability and validity of study constructs were tested using Analysis of Moment Structures, on AMOS 21 (Arbuckle, 2012). AMOS Structural Estimates for Proposed Structural Equation Model (Maximum Likelihood), Factor Loadings and Relationship Coefficients of Proposed Structural Equation, all show statistically significant relationships for each variable with respect to latent construct (Table 2). The maximum likelihood method was adapted for estimation. The Goodness of Fit Statistics of Proposed Structural Equation Model are as follow; Chi Square/df (df = 12, D2 = 42.30), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA = .06), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI = .97), Adjust Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI = .95), Normed Fit Index (NFI = .97), Root Mean Square Residual (RMR= .04) and Comparative Fit Index (CFI= .97). The relatively high level of the Goodness of Fit Statistics Indices indicates that relationships among variables are statistically significant. Composite reliability values were also calculated that showed good reliability coefficients of between .70 and 0.90 (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994).

Table 2

Measurement and Structural Model Fit

Further analyses ran bootstrapping to confirm the mediation effect of trust, a “most powerful and reasonable method of obtaining confidence limits for specific indirect effects under most conditions” (Preacher and Hayes, 2008: 13). Statistical mediation, moderation, and conditional process analyses were all performed following the PROCESS procedure (Hayes, 2013) for testing moderation and mediation effects.

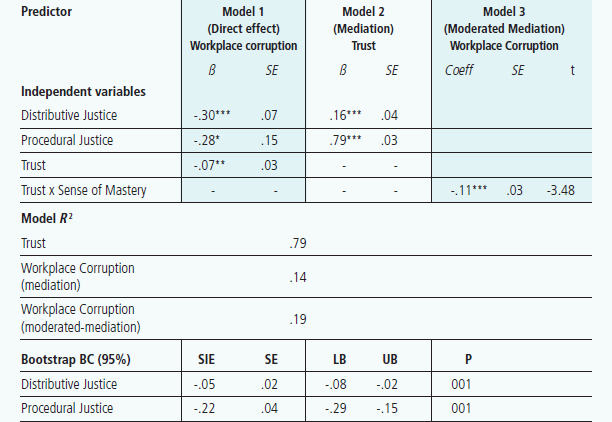

Table 3 presents results for Hypotheses 1 to 4. Three nested models were examined. The first model illustrates the direct effects of organizational justice variables on corruption. The second model corresponds to the mediation analysis. The third model tests the moderated mediation using Preacher and Hayes’ (2008) bootstrapping procedure.

Supporting Hypotheses 1 and 2, both distributive justice and procedural justice negatively predict workplace corruption, as indicated by their respective standardized regression coefficient (ß = -.30, p < .001, for distributive justice; ß = -.28, p < .05, for procedural justice).

Hypothesis 3, which predicted a trust mediation effect between measures of organizational justice and workplace corruption, is also validated. Specifically, and with regard to distributive justice, there is a significant effect on trust (.16, p = .001). Similarly, for procedural justice, results show a significant direct effect on trust (.79, p = .001), and a direct effect of trust on workplace corruption (-.07, p = .01). Results, however, indicate partial mediations, as both procedural and distributive justice paths to workplace corruption remain significant. Specifically, partial mediation is suggested because distributive and procedural justice impact directly on corruption while they also impact on corruption through interpersonal trust.

Further bootstrapping analysis was conduct in order to confirm the mediation effect of trust. Based on the results in Table 3, it is found that the Standardized Indirect Effects (SIE) value for both procedural justice [(-.22, p = .001, with confidence interval CL 95% (-.29, -.15)] and distributive justice [(-.05, p = .001, with confidence interval, CL 95% (-.08, -.02)] are between Lower Bounds (LB) and Upper Bounds (UB), with significant p values inferior to .05. This confirms a significant mediating effect of trust between organizational justice (distributive and procedural) and workplace corruption.

Table 3

Mediation and Moderated Mediation Results for Workplace Corruption

Table 3 also presents results for Hypothesis 4. These indicate that the cross-product coefficient between trust and a sense of mastery is significant (ß = -.11, t = -3.48, p < .001). The moderated mediation hypothesis on work corruption is thus validated. Comparisons between models indicate that a moderated mediation model adds explained variance to the mediation model (DR2 = .05).

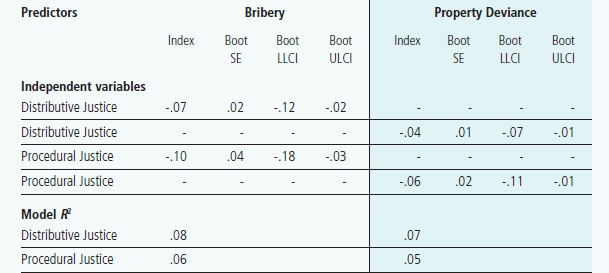

To enrich our understanding of workplace corruption mechanisms, we further tested the moderated mediation model with bribery and property deviance as dependent variables. Results thus highlight a greater negative impact of procedural justice than distributive justice on bribery and property deviance (Table 4).

Table 4

Moderated Mediation Results for Bribery and Property Deviance

Discussion

This study draws from COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989, 2001). As such, it identifies corruption as a strategy to secure valued motivational resources and corrupt behaviour as a response to the perceived threat to one’s occupational assets. At this point, corrupt acts are considered legitimate, as the corrupting individual considers himself a victim who fights for professional survival (Gardiner and Olson, 1974). Consequently, we examined an integrated moderated mediation model that tests a negative relationship between selected determinants, including perceived organizational signals related to organizational justice and interpersonal trust, and individual perception of occupational mastery and the emergence of corrupt acts, including bribery and property deviance.

Results provide support for our moderated-mediation model and shed new light on the determining mechanisms of workplace corruption. That is, for individuals whose interpersonal trust on the job is affected by feelings of unfair treatment, a reaction in the form of corrupt behaviours is all the more likely when it coincides with a sense of loss in controlling the work situation. Specifically, bribery and property deviance are found to be significant responses to combined states of distrust and occupational estrangement that arise mostly from perceptions of procedural injustice. These findings call for attention, as they contribute to the literature at various levels that we now review.

A main contribution is to go beyond the empirical experience of workplace corruption to provide an explanatory framework that enriches the micro level of personal dynamics (Dimant and Schulte, 2016). As such, we have proposed conceptualizing corruption as an interaction process between individual and organizational stakes. Specifically, this study envisions corruption as a way to manage motivational needs for organizational justice and interpersonal trust. Negative perceptions of the organizational environment send adverse signals to individuals who seek protection from potential losses (Vermunt and Steensma, 2016). Consequently, this threat leads to the selection of corrupt behaviours, e.g. bribery and property deviance, as the most appropriate strategy for stalling negative spirals of resource depletion. A contribution of the present study is thus to integrate COR theory (Hobfoll, 2001; Hobfoll et al., 2018) and metamotivational research (Scholer and Miele, 2016; Scholer, et al., 2018), whereby workplace corruption relates to self-regulation for achieving the goal of resource preservation.

Within this overreaching framework, our results offer conceptual and modelling contributions. First, this research highlights complex interactions between psychological determinants of corruption. We thus found that a perceived depletion of an individual sense of mastery, a motivational resource, can be linked to a perceived lack of a favourable environment materialized by organizational justice and interpersonal trust, two resource signals. For instance, the impact of organizational justice on corruption depends on the type of perceived justice. As compared to distributive justice, procedural justice emerges as a signal of significance that strongly relates to the occurrence of corrupt outcomes. This result is in line with recent investigations on the differential value of psychological resources in relation to outcomes (Morelli and Cunningham, 2012; Pines et al., 2002). Our results suggest corruption as a form of resistance to a perceived unfair change in organizational arrangements. This unfairness is gauged relative to referent determinants among which procedural justice emerges as more valuable than distributive justice.

Second, this research adds support for considering corruption as a trust-determined retaliatory process at the social/interpersonal level (Niehoff and Paul, 2000). Fuelled by a perceived breach of social contract, bribery and property deviance emerge as reactions against organizational rules that are, or are about to be, broken or used unfairly against one’s interests. Consequently, individuals who feel deprived of a fair resource allocation process question others’ trustworthiness, while trust relates precisely to procedural transparency and retributive justice (Frazier et al., 2010; Khiavi et al., 2016; Ruder, 2003). Furthermore, our results corroborate the mediating role of trust between feelings of justice and a favourable outcome pertaining to workers’ attitudes (Lewicki et al., 2005). Lower trust reduces perceived legitimacy, an instrumental mode of obedience to rules and norms. The recourse to corruption thus finds legitimacy in a de-legitimization of the organizational environment. Bribery and property deviance are adaptive answers for protecting assets when confronting a poorly regarded and distrusted environment.

Finally, an interesting result of our research is about how resources combine between themselves. Our moderated mediation model validates the differential role of trust and a sense of mastery on corruption. In the same vein, increased corruption is found to contribute significantly to a unique combination of weaker perceived procedural justice and lower trust. This suggests that the feeling of being in charge can buffer the deleterious impact of crippled trusting relationships, as individuals hope to be able to compensate for, or to restore, lost resources (Hobfoll, 2001; Stets, 1995). This result can also suggest that procedural justice acts as a “surrogate for trust” in regulating investment quality in social relationships.

Conclusion: limits and perspectives

Our results highlight the role of both distributive justice and procedural justice in the conditioning mechanism of corruption. The question remains, however, as to the role of other facets of organizational justice. Though not specifically applied to corruption, it has been noted that both interpersonal and informational justice relate to negative organizational reactions (Colquitt et al., 2001; Colquitt and Rodell, 2011). Fairness of interpersonal communication can thus be expected to impact on the perceived reliability of the psychological contract that frames organizational social exchange (Kingshott and Dincer, 2008). With regard to corruption, future research can explore the conditioning role of interactional justice as an interpersonal resource to be preserved and developed.

As presented above, corruption is not limited to bribes and property deviance. Accordingly, we suggest that resources involved in the corruption process extend beyond those presented in this study. Nepotism and cronyism have thus been related to a need for secure cooperation, an interpersonal resource, between individuals of common kin (Colarelli, 2015). Likewise, it has been suggested that graft can be considered “honest” by the perpetrator when appraised as a legitimate protective answer to the perceived threat on valued tangible assets, including money, electors, or customers (Riordan, 1974). Our study paves the way for more investigations that consider corruption from the perspective of an interaction between selected corrupt outcomes and specific resources.

Concerning its methodology, our study raises the issue of the possible effects of response style and common method variance (CMV). Indeed, a cross-sectional design such as ours on such a sensitive topic as corruption can induce measurement error from respondents’ answers. To attenuate this potential bias, we have controlled results in both procedural and statistical ways (Podsakoff et al., 2003). First, the questionnaire created a psychological separation by differentiating between measurements related to organizational perceptions, i.e. impersonal answering mode for resource signals and dependant corruption variables, and the interpersonal trust variable, i.e. first-person answering mode. Second, a post-hoc statistical Harman’s Single Factor Test yielded a 27% variance of first factor unrotated principal component factor analysis, well below the 50% cap defined by the literature (Henseler, Ringle and Sarstedt, 2015).

With regard to psychometrics, it should also be noted that Cronbach’s alpha measurement of property deviance of .68 is relatively low. That said, this near .70 coefficient remains acceptable, keeping in mind the difficulty of obtaining high alpha scores on scales with few items (Cortina, 1993; Nunnally, 1978). We suggest future research explores possible scale expansion for increasing measurement robustness.

Finally, future research using a COR framework can apply corruption to the context of cultures and values. First, possible contrasting results could be tested on samples from private sector organizations. Differences in the work context may indeed affect individual strategies and interpersonal relationships. Second, organizational corruption is a global issue that challenges national and personal norms of conduct (Bierstaker, 2009; Hooker, 2009). Based on an indiscriminate sample, our findings beg for replication while controlling for the cultural environment. We suggest closer attention to the relevance of conservation values (Schwartz et al., 2012) could add significant understanding to the corruption motivation process.

Parties annexes

References

- Abu Elanain, Hossam M. (2010) “Testing the Direct and Indirect Relationship between Organizational Justice and Work Outcomes in a Non-Western Context of the UAE.” Journal of Management Development, 29 (1), 5-27.

- Aghion, Philippe, Yann Algan, Pierre Cahuc and Andrei Shleifer (2010) “Regulation and Distrust.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125 (3), 1015-1049.

- Akers, Ronald L. (1988) Social Structure and Social learning, Los Angeles: Roxbury.

- Allameh, Sayyed Mohsen and Najib Abbasi Rostami (2014) “Survey Relationship between Organizational Justice and Organizational Citizenship Behavior.” International Journal of Management Academy, 2 (3), 1-8.

- Allison, Graham T. (2012) “Public and Private Management: Are They Fundamentally Alike in All Unimportant Respects?” In Jay M. Shafritz and Albert C. Hyde (eds.), Classics of Public Administration (17th edt), Boston: Wadsworth.

- Ambrose, Maureen L, Seabright Mark A. and Marshall Schminke (2002) “Sabotage in the Workplace: The Role of Organizational Injustice.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89 (1), 947-965.

- Ambrose, Maureen L. and Marshall Schminke (2009) “The Role of Overall Justice Judgments in Organizational Justice Research: A Test of Mediation.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 94 (2), 491-500.

- Andvig, Jens Chr., Ode-Helge Fjeldstad, Inge Amundsen, Tone Sissener and Tina Søreide (2000) Research on Corruption, A Policy Oriented Survey. Bergen: Christian Michelsen Institute and Norwegian Institute of International Affairs.

- Antonovsky, Aaron (1987) Unravelling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Aquino, Karl, Margaret U. Lewis and Murray Bradfield (1999) “Justice Constructs, Negative Affectivity, and Employee Deviance: A Proposed Model and Empirical Test.” Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20 (7), 1073-1091.

- Arbuckle, James L. (2012) IBM SPSS AMOS 21– User’s Guide. Amos Development Corporation.

- Ashforth, Blake E. and Vikas Anand (2003) “The Normalization of Corruption in Organizations.” Research in Organizational Behavior, 25, 1-52.

- Ashforth, Blake E., Spencer H. Harrison and Kevin G. Corley (2008) “Identification in Organizations: An Examination of Four Fundamental Questions.” Journal of Management, 34 (3), 325-374.

- Bashir, Sajid, Misbah Nasir, Saira Qayyum and Ambreen Bashir (2012) “Dimensionality of Counterproductive Work Behaviors in Public Sector Organizations of Pakistan.” Public Organization Review, 12 (4), 357-366.

- Bashir, Sajid, Zafar M. Nasir, Sania Saeed and Maimoona Ahmed (2011) “Breach of Psychological Contract, Perception of Politics and Organizational Cynicism: Evidence from Pakistan.” African Journal of Business Management, 5 (3), 884-888.

- Baucus, Melissa S. (1994) “Pressure, Opportunity and Predisposition: A Multivariate Model of Corporate Illegality.” Journal of Management, 20 (4), 699-721.

- Bayart, Jean-François, Stephen Ellis and Beatrice Hibou (1997) Criminalization of the State in Africa (African Issues), Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Bennett, Rebecca J. and Sandra L. Robinson (2003) “The Past, Present, and Future of Workplace Deviance Research”. In Jerald Greenberg (Ed.), Organizational Behavior: The State of the Science. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Second Edition, p. 247-281.

- Bierstaker, James (2009) “Differences in Attitudes about Fraud and Corruption across Cultures: Theory, Examples and Recommendations.” Cross Cultural Management: An International Journal, 16 (3), 241-250.

- Boes, Jennifer O., Callie J. Chandler and Howard W. Timm (1997) Police Integrity: Use of Personality Measures to Identify Corruption-Prone Officers. Monterrey, CA: Defense Personnel Security Research Center Monterey CA.

- Bowling, Nathan A. and Mellisa L. Gruys (2010) “Overlooked Issues in the Conceptualization and Measurement of Counterproductive Work Behavior.” Human Resource Management Review, 20 (1), 54-61.

- Campbell, Nathanael S., Sara Jansen Perry, Carl P. Maertz, D. G. Allen and R. W. Griffith (2013) “All You Need Is … Resources: The Effects of Justice and Support on Burnout and Turnover.” Human Relations, 66 (6), 759-782.

- Clinard, Marshall Barron and Richard Quinney (1973) Criminal Behavior Systems: A Typology. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Cohen-Charash, Yochi and Paul E. Spector (2001) “The Role of Justice in Organizations: A Meta-Analysis.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86 (2), 278-321.

- Colarelli, Stephen M. (2015) “Human Nature, Cooperation and Organizations.” Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 8 (1), 37-40.

- Colquitt, Jason A. (2001) “On the Dimensionality of Organizational Justice: A Construct Validation of a Measure.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 86 (3), 386-400.

- Colquitt, Jason A. and Jessica B. Rodell (2011) “Justice, Trust, and Trustworthiness: A Longitudinal Analysis Integrating Three Theoretical Perspectives.” Academy of Management Journal, 54 (6), 1183-1206.

- Colquitt, Jason A., Donald E. Conlon, Michael Wesson, Christopher O. Porter and K. N. Ng (2001) “Justice at the Millennium: A Meta-Analytic Review of 25 Years of Organizational Justice Research.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 86 (3), 425-445.

- Cook, John and Toby Wall (1980) “New Work Attitude Measures of Trust, Organizational Commitment and Personal Need Non-Fulfillment.” Journal of Occupational Psychology, 53 (1), 39-52.

- Cortina, Jose M. (1993) “What is Coefficient Alpha? An Examination of Theory and Applications.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 78 (1), 98-104.

- Cropanzano, Russel and Molina, Agustin (2015) “Organizational Justice”. In James D. Wright (Ed.), International Encyclopaedia of the Social and Behavioural Sciences, 2nd edition, Vol 17. Oxford: Elsevier, p. 379-384.

- Darley, John M. (2005) “The Cognitive and Social Psychology of Contagious Organizational Corruption.” Brooklyn Law Review, 70 (4), 1177-1194.

- Del Giudice, Marco (2016) “The Evolutionary Future of Psychopathology.” Current Opinion in Psychology, 7, 44-50.

- Deschard, Flore and Marie-Françoise Le Guilly (2017) Tableau de bord de l’emploi public – Situation de la France et comparaisons internationales. Available at: https://www.strategie.gouv.fr/sites/strategie.gouv.fr/files/atoms/files/tdb-emploi-public-20-12-2017.pdf.

- Dimant, Eugen and Thorben Schulte (2016) “The Nature of Corruption: An Interdisciplinary Perspective.” German Law Journal, 17 (1), 53-72.

- Fan, Ying (2002) “Questioning Guanxi: Definition, Classification and Implications.” International Business Review, 11 (5), 543-561.

- Farndale, Elaine, Veronica Hope-Hailey and Clara Kelliher (2010) “High Commitment Performance Management: The Roles of Justice and Trust.” Personnel Review, 40 (1), 5-23.

- Farnham, David and Sylvia Horton (1996) Managing the New Public Services. London, UK: Macmillan International Higher Education.

- Fisher, Ronald and Peter B. Smith (2004) “Values and Organizational Justice: Performance and Seniority-Based Allocation Criteria in the UK and Germany.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35 (6), 669-688.

- FitzGerald, Michael Robert (2002) Organizational Cynicism: Its Relationship to Perceived Organizational Injustice and Explanatory Style. PhD Thesis, University of Cincinnati, USA.

- Forret, Monica and Mary Sue Love (2008) “Employee Justice Perceptions and Coworker Relationships.” Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 29 (3), 248-260.

- Frazier, Lance M., Paul D. Johnson, Mark Gavin, Janaki Gooty and Bradley D. Snow (2010) “Organizational Justice, Trustworthiness and Trust: A Multifoci Examination.” Group and Organization Management, 35 (1), 39-76.

- Gardiner, John A. and David J. Olson (1974) Theft of the City. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Gbadamosi, Gbolahan and Patricia Joubert (2005) “Money Ethic, Moral Conduct and Work Related Attitudes: Field Study from the Public Sector in Swaziland.” Journal of Management Development, 24 (8), 754-763.

- Gopinath, C. (2008) “Recognizing and Justifying Private Corruption.” Journal of Business Ethics, 82 (3), 747-754.

- Gorsira, Madelijne, Adriaan Denkers and Wim Huisman (2018) “Both Sides of the Coin: Motives for Corruption among Public Officials and Business Employees.” Journal of Business Ethics, 151 (1), 179-194.

- Greenberg, Jerald (1990) “Employee Theft as a Reaction to Underpayment Inequity: The Hidden Cost of Pay Cuts.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 75 (5), 561-568.

- Gruys, Mellisa L. (1999) The Dimensionality of Deviant Employee Performance in the Workplace. PhD Thesis, University of Minnesota, Minnesota, USA.

- Gruys, Mellisa L. and Paul R. Sackett (2003) “Investigating the Dimensionality of Counterproductive Work Behavior.” International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 11 (1), 30-42.

- Gualandri, Mario (2012) Counterproductive Work Behaviors and Moral Disengagement. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy.

- Halbesleben, Jonathon R. B., Jean-Pierre Neveu, Samantha C. Paustian-Underdahl and Mina Westman (2014) “Getting to the `COR`: Understanding the Role of Resources in Conservation of Resources Theory.” Journal of Management, 40 (5), 1334-1364.

- Halbesleben, Jonathon R. B. and Anthony R. Wheeler (2015) “To Invest or Not? The Role of Coworker Support and Trust in Daily Reciprocal Gain Spirals in Helping Behavior.” Journal of Management, 41 (6), 1628-1650.

- Henseler, Jörg, Christian M. Ringle and Marko Sarstedt (2015) “A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43 (1), 115-135.

- Hobfoll, Stevan E. (1989) “Conservation of Resources: A New Attempt at Conceptualizing Stress.” American Psychologist, 44 (3), 513-524.

- Hobfoll, Stevan E. (2001) “The Influence of Culture, Community, and the Nested-Self in the Stress Process: Advancing Conservation of Resources Theory.” Applied Psychology: An International Review, 50 (3), 337-421.

- Hobfoll, Stevan E. (2002) “Social and Psychological Resources and Adaptation.” Review of General Psychology, 6 (4), 307-324.

- Hobfoll, Stevan E. (2011) “Conservation of Resources Caravans in Engaged Settings.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84 (1), 116-122.

- Hobfoll, Stevan E., Jonathon R. B. Halbesleben, Jean-Pierre Neveu and Mina Westman (2018) “Conservation of Resources in the Organizational Context: The Reality of Resources and their Consequences.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 103-128.

- Hollinger, Richard and John Clark (1982) “Employee Deviance: A Response to the Perceived Quality of the Work Experience.” Work and Occupations, 9 (1), 97-114.

- Hooker, John (2009) “Corruption from a Cross-Cultural Perspective.” Cross-Cultural Management: An International Journal, 16 (3), 251-267.

- Judge, William Q., Brian D. McNatt and Weichu Xu (2011) “The Antecedents and Effects of National Corruption: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of World Business, 46 (1), 93-103.

- Kelley, Harold H. and John W. Thibault (1978) Interpersonal Relationships: A Theory of Interdependence. New York: John Wiley.

- Kemp, Harriet (2013) “The Cost of Corruption is a Serious Challenge for Companies.” The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/corruption-bribery-cost-serious-challenge-business.

- Khiavi, Farzad Faraji, Kamal Shakhi, Roohallah Dehghani and Mansour Zahiri (2016) “The Correlation between Organizational Justice and Trust among Employees of Rehabilitation Clinics in Hospitals of Ahvaz, Iran.” Electronic Physician, 8 (2), 1904-1910.

- Kingshott, Russel P. J. and Oguzhan C. Dincer (2008) “Determinants of Public Service Employee Corruption: A Conceptual Model from the Psychological Contract Perspective.” Journal of Industrial Relations, 50 (1), 69-85.

- Kong, Dejun Tony, Kurt T. Dirks and Donald L. Ferrin (2012) “Interpersonal Trust within Negotiations: A Meta-Analytic Evidence, Critical Contingencies, and Directions for Future Research.” Academy of Management Journal, 57 (5), 1235-1255.

- Krot, Katarzyna and Dagmara Lewicka (2012) “The Importance of Trust in Manager-Employee Relationships.” International Journal of Electronic Business Management, 10 (3), 224-233.

- Kwok, Chi-Ko, Wing Tung Au and Jane M. C. Ho (2005) “Normative Controls and Self-Reported Counterproductive Behaviors in the Workplace in China.” Applied Psychology: An International Review, 54 (4), 456-475.

- Lange, Donald (2008) “A Multidimensional Conceptualization of Organizational Corruption Control.” The Academy of Management Review, 33 (3), 710-729.

- Lefkowitz, Joel (2009) “Individual and Organizational Antecedents of Misconduct in Organizations: What Do We (Believe that We) Know, and on What Bases Do We (Believe that We) Know it?” In Ronald J. Burke and Cary L. Cooper (Eds.), Research Companion to Corruption in Organizations. Cheltenham UK: E. Elgar, p. 60-91.

- Lewicki, Roy J., Carolyn Wiethoff and Edward C. Tomlinson (2005) “What is the Role of Trust in Organizational Justice?” In Jerald Greenberg and Jason A. Colquitt (Eds.), Handbook of Organizational Justice. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, p. 247-270.

- Lewicki, Roy J., Daniel J. McAllister and Robert J. Bies (1998) “Trust and Distrust: New Relationships and Realities.” Academy of Management Review, 23 (3), 438-458.

- Lim, Vivien KG. (2002) “The IT Way of Loafing on the Job: Cyber Loafing, Neutralizing, and Organizational Justice.” Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23 (5), 675-694.

- Lindgreen, Adam (2004) “Corruption and Unethical Behavior: Report on a Set of Danish Guidelines.” Journal of Business Ethics, 51 (1), 31-39.

- Luo, Yadong (2008) “The Changing Chinese Culture and Business Behavior: The Perspective of Intertwinement between Guanxi and Corruption.” International Business Review, 17 (2), 188-193.

- Mangione, Thomas W. and Robert P. Quinn. (1975) “Job Satisfaction, Counterproductive Behavior, and Drug Use at Work.”Journal of Applied Psychology, 60 (1), 114-116.

- Martinko, Mark J., Michael J. Gundlach and Scott C. Douglas (2002) “Toward an Integrative Theory of Counterproductive Workplace Behavior: A Causal Reasoning Perspective.” International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 10 (1), 36-50.

- McCardle, Jie Guo (2007) Organizational Justice and Workplace Deviance: The Role of Organizational Structure, Powerlessness, and Information Salience. PhD Thesis, Central Florida University, Orlando, USA.

- McFarlin, Dean B. and Paul D. Sweeney (1997) “Process and Outcome: Gender Differences in the Assessment of Justice.” Journal of Organizational Behavior, 18 (1), 83-98.

- Mitchell, Marie S., Michael D. Baer, Maureen L. Ambrose, Robert Folger and Noel F. Palmer (2018) “Cheating under Pressure: A Self-Protection Model of Workplace Cheating Behavior.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 103 (1), 54-73.

- Montero, David (2018) Kickback: Exposing the Global Corporate Bribery Network. New York, NY: Viking.

- Moore, Celia (2008) “Moral Disengagement in Processes of Organizational Corruption.” Journal of Business Ethics, 80 (1), 129-139.

- Moore, Celia (2009) “Psychological Perspectives On corruption”. In David De Cremer (Ed.), Psychological Perspectives on Ethical Behavior and Decision Making. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, p. 35-71.

- Moore, Celia (2015) “Moral Disengagement.” Current Opinion in Psychology, 8 (1), 199-204.

- Moorman, Robert and Philipe M. Podsakoff (1992) “A Meta-Analytic Review and empirical Test of the Potential Confounding Effects of Social Desirability Response Sets in Organizational Behavior Research.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 65, 131-149.

- Moorman, Robert H. (1991) “Relationship between Organizational Justice and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: Do Fairness Perceptions Influence Employee Citizenship?” Journal of Applied Psychology, 76 (6), 845-855.

- Morelli, Neil A. and Christopher J. L. Cunningham (2012) “Not all Resources Are Created Equal: COR Theory, Values and Stress.” The Journal of Psychology, 146 (4), 393-415.

- Niehoff, Brian P. and Robert H. Moorman (1993) “Justice as a Mediator of the Relationship between Methods of Monitoring and Organizational Citizenship Behavior.” Academy of Management Journal, 36 (3), 527-556.

- Niehoff, Brian P. and Robert J. Paul (2000) “Causes of Employee Theft and Strategies that HR Managers Can Use for Prevention.” Human Resource Management, 39 (1), 51-64.

- Nirmala, Christine A. and K. B. Akhilesh (2006) “An Attempt to Redefine Organizational Justice: In the Rightsizing Environment.” Journal of Organizational Change Management, 19 (2), 136-153.

- Nobel, Carmen (2013) “The Real Cost of Bribery.” Forbes. Retrieved from http://onforb.es/HEkSbH.

- Nooteboom, Bart, Hans Berger and Niels G. Noorderhaven (1997) “Effects of Trust and Governance on Relational Risk.” Academy of Management Journal, 40 (2), 308-338.

- Nunnally, Jum C. (1978) Psychometric Theory, New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Nunnally, Jum C. and Ira H. Bernstein (1994) “The Theory of Measurement Error.” Psychometric Theory, 3, 209-247.

- Pablo, Amy L., Trish Reay, James R. Dewald and Anne L. Casebeer (2007) “Identifying, Enabling and Managing Dynamic Capabilities in the Public Sector.” Journal of Management Studies, 44 (5), 687-708.

- Pearce, Jone L. (2015) “Cronyism and Nepotism Are Bad for Everyone: The Research Evidence.” Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 8 (1), 41-44.

- Pearce, Jone L. and Laura Huang (2014) Workplace Favoritism: Why it Damages Trust and Persists. Merage School of Business Working Paper, University of California, Irvine.

- Pearlin, Leonard I. and Carmi Schooler (1978) “The Structure of Coping.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 19 (1), 2-21.

- Peterson, Dane K. (2002) “Deviant Workplace Behavior and the Organization’s Ethical Climate.” Journal of Business and Psychology, 17 (1), 47-61.

- Pines, Avala M., Adital Ben-Ari, Agnes Utasi and Dale Larson (2002) “A Cross-Cultural Investigation of Social Support and Burnout.” European Psychologist, 7 (4), 256-264.

- Pinto, Jonathan, Carrier R. Leana and Frits K. Pil (2008) “Corrupt Organizations or Organizations of Corrupt Individuals? Two Types of Organization-Level Corruption.” Academy of Management Review, 33 (3), 685-709.

- Podsakoff, Philip M., Scott B. MacKenzie and Jeong-Yeo Lee (2003) “Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 88 (5), 879.

- Preacher, Kristopher J. and Andrew F. Hayes (2008) “Contemporary Approaches to Assessing Mediation in Communication Research”. In Andrew F. Hayes, Michael D. Slater and Leslie B. Snyder (Eds.), The Sage Sourcebook of Advanced Data Analysis Methods for Communication Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, p. 13-54.

- Rabl, Tanja (2011) “The Impact of Situational Influences on Corruption in Organizations.” Journal of Business Ethics, 100 (1), 85-101.

- Riordan, William L. (1974) “Honest Graft”. In John A. Gardiner and David J. Olson (Eds.) Theft of the City. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, p. 7-9.

- Robinson, Sandra L. and Anne M. O’Leary-Kelly (1998) “Monkey See, Monkey Do: The Influence of Work Groups on the Antisocial Behavior of Employees.” Academy of Management Journal, 41 (6), 658-672.

- Robinson, Sandra L. and Rebecca Bennett (1995) “A Typology of Deviant Workplace Behaviors: A Multidimensional Scaling Study.” Academy of Management Journal, 38 (2), 555-572.

- Ruder, Gary J. (2003) The Relationship among Organizational Justice, Trust and Role Breadth Self-Efficacy. PhD Thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Virginia, USA.

- Sackett, Paul R. and Cynthia J. DeVore (2001) “Counterproductive Behaviors at Work”. In Anderson, Neil, Deniz Ones, Handan K. Sinangil and Chockalingam Viswesvaran (Eds.), Handbook of Industrial, Work and Organizational Psychology. London, UK: Sage, p. 145-164.

- Saekoo, Areerat (2011) “Examining the Effect of Trust, Procedural Justice, Perceived Organizational Support, Commitment and Job Satisfaction in Royal Thai Police: The Empirical Investigation in Social Exchange Perspective.” Journal of Academy of Business and Economics, 11 (3), 229-237.

- Salgado, Jesus F. (2002) “The Big Five Personality Dimensions and Counterproductive Behaviors.” International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 10 (1), 117-125.

- Saunders, Mark N. K. and Adrian Thornhill (2003) “Organizational Justice, Trust and the Management of Change: An Exploration.” Personnel Review, 32 (3), 360-375.

- Schaefer, David R. and Don A. Dillman (1998) “Development of a Standard E-Mail Methodology: Results of an Experiment.” Public Opinion Quarterly, 378-397.

- Scholer, Abigail A., David B. Miele, Kou Murayama and Kentaro Fujita (2018) “New Directions in Self-Regulation: The Role of Metamotivational Beliefs.” Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27 (6), 437-442.

- Scholer, Abigail A. and David B. Miele (2016) “The Role of Metamotivation in Creating Task-Motivation Fit”. Motivation Science, 2, 171-197.

- Schuldt, Barbara A. and Jeff W. Totten (1994) “Electronic Mail vs. Mail Survey Response Rates.” Marketing Research, 6 (1), 3-7.

- Schwartz, Shalom H., Jan Cieciuch, Michael Vecchione, Eldad Davidov, Ronald Fisher, Contanze Beierlein, Alice Ramos, Markus Verkasalo, Jan-Erik Lönnqvist, Kursad Demirutku, Ozlem Dirilen-Gumus and Mark Konty (2012) “Refining the Theory of Basic Individual Values.” Personality Processes and Individual Differences, 103 (4), 663-688.

- Senge, Peter M. (2010) The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. London: Century Business.

- Sengupta, Jaideep, Anirban Mukhopadhyay and Gita V. Johar (2012) Care Enough to Cheat: Self-Mastery and Decision-Making. New York: Columbia University.

- Serafeim, George (2014) Firm Competitiveness and Detection of Bribery. Harvard Business School, Working Paper 14-012.

- Siller, Heidi, Angelika Bader and Margarethe Hochleitner (2016) “Support for Female Physicians at a University Hospital: What Do Differences between Female and Male Physicians Tell Us?” In Roxane L. Gervais and Prudence M. Millear (Eds.), Exploring Resources, Life-Balance and Well-Being of Women who Work in a Global Context. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, p. 109-125.

- Simons, Tony and Quinetta Roberson (2003) “Why Managers Should Care about Fairness: The Effects of Aggregate Justice Perceptions on Organizational Outcomes.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 88 (3), 432.

- Skarlicki, Daniel P. and Robert Folger (1997) “Retaliation in the Workplace: The Roles of Distributive, Procedural, and Interactional Justice.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 82 (3), 434-443.

- Spector, Paul E. and Suzy Fox (2005) “The Stressor-Emotion Model of Counterproductive Work Behavior (CWB)”. In Suzy Fox and Paul E. Spector (Eds.), Counterproductive Work Behavior: Investigations of Actors and Targets. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, p. 151-174.

- Spector, Paul E., Suzy Fox, Lisa M. Penney, Kari Bruursema, Angeline Goh and Stacey Kessler (2006) “The Dimensionality of Counterproductivity: Are All Counterproductive Behaviors Created Equal?” Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68 (3), 446-460.

- Stachowicz-Stanusch, Agata (2010) “Corruption Immunity Based on Positive Organizational Scholarship towards Theoretical Framework.” In Agata Stachowicz-Stanusch (Ed.), Organizational Immunity to Corruption: Building Theoretical and Research Foundations. IAP, p. 35-62.

- Stachowicz-Stanusch, Agata and Simha Aditya (2013) “An Empirical Investigation of the Effects of Ethical Climates on Organizational Corruption.” Journal of Business Economics and Management, 14 (1), S433-S446.

- Stets, Jane E. (1995) “Role Identities and Person Identities: Gender Identity, Mastery Identity and Controlling One’s Partner.” Sociological Perspectives, 38 (2), 129-150.

- Svensson, Jakob (2005) “Eight Questions about Corruption.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19 (3), 19-42.

- Syaebani, Muhammad I. and Sobri Riani (2011) “Relationship between Organizational Justice Perception and Engagement in Deviant Workplace Behavior.” The South East Asian Journal of Management, 5 (1), 37-49.

- Thau, Stephan, Craig Crossley, Rebbeca J. Bennett and Sabine Sczesny (2007) “The Relationship between Trust, Attachment, and Antisocial Work Behaviors.” Human Relations, 60 (8), 1155-1179.

- Transparency International (2017) Corruption Perception Index 2017. Available at: https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2017.

- Transparency International France (2018) L’indice de perception de la corruption 2018 montre que la lutte contre la corruption est au point mort dans la plupart des pays. Available at: https://transparency-france.org/actu/indice-de-perception-de-la-corruption-2018/.

- UK Public General Acts (2010) UK Bribery Act. Available at: www.opsi.gov.uk/acts/acts2010/ukpga_20100023_en_1.

- Valcour, Monique, Ariane Ollier-Malaterre, Christina Matz-Costa, Marcie Pitt-Catsouphes and Melissa Brown (2011) “Influences on Employee Perceptions of Organizational Work-Life Support: Signals and Resources.” Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79, 588-595.

- Vermunt, Riël and Herman Steensma (2016) “Procedural Justice”. In Clara Sabbagh and Manfred Schmitt (Eds.), Handbook of Social Justice and Research. New York: Springer, p. 219-236.

- Vohs, Kathleen D. and Jonathan W. Schooler (2008) “The Values of Believing in Free Will: Encouraging a Belief in Determinism Increases Cheating.” Psychological Science, 19 (1), 49-54.

- White, Bernard J. and B. Ruth Montgomery (1980) “Corporate Codes of Conduct.” California Management Review, 23 (2), 80-87.

- Williams, Lauren L. (2006) “The Fair Factor in Matters of Trust.” Nursing Administration Quarterly, 30 (1), 30-37.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Theoretical Model of Workplace Corruption

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics and Variable Inter-Correlations / Sample (n = 575)

Table 2

Measurement and Structural Model Fit

Table 3

Mediation and Moderated Mediation Results for Workplace Corruption

Table 4

Moderated Mediation Results for Bribery and Property Deviance