Résumés

Summary

The McDonald’s labour management strategy is widespread in the fast food industry. Literature that is critical of the approach often portrays the work as low paid, unchallenging and uninteresting. Others argue that industry jobs provide an enhanced resume, training opportunities, and the possibility of a career. Rather than being inherently disadvantageous or beneficial, it is possible that fast food employment addresses the needs and aspirations of some more than others. This article proposes such a view in relation to teenagers. It poses the question: what are the characteristics of those who are suitable for industry work? Surveys are used to develop a statistical profile of ideal workers. Findings have implications for stakeholder decision making and offer an empirical perspective of a contentious issue that attracts opinion and speculation. Results indicate that developmental change and an overt inclination to choose a fast food career are key considerations in determining employee suitability.

Keywords:

- teenagers,

- paid work,

- fast food careers,

- employee suitability,

- Australia

Résumé

Le travail dans la restauration rapide : une vision empirique des employés exemplaires

La stratégie des relations du travail chez McDonald est largement répandue dans l’industrie de la restauration rapide. Les écrits de nature critique sur les employeurs de ce secteur mettent en évidence le caractère d’exploitation propre au travail ou ses caractéristiques de précarité. Les élites universitaires qui reconnaissent l’exploitation font souvent remarquer que ce sont des adolescents qui se partagent les emplois dans le secteur. Elles laissent souvent entendre que ces salariés font preuve d’une naïveté face à leurs droits; ils font partie de la main-d’oeuvre active pour la première fois; ils ne sont pas sûrs d’eux ou ils sont incapables d’arriver à un jugement correct sur leurs propres intérêts. Dans de telles circonstances, on observe trois types de résultats possibles : l’épuisement professionnel, l’endoctrinement ou le départ prématuré (roulement).

Les travaux de recherche sur l’exploitation signalent deux choses : ou bien les adolescents ne sont pas aptes au travail de la restauration, ou, si quelques uns le sont, ceci serait dû au fait qu’ils manquent de créativité et d’innovation, qu’ils acceptent la direction sans esprit critique et qu’ils sont vulnérables face à la manipulation des directions d’entreprise ou à l’adulation empreinte de mauvaise foi. Une telle vision (décrite ainsi comme de l’endoctrinement) subit l’influence de l’idée marxiste de fausse conscience.

Les écrits qui traitent de la précarité sont moins critiques à l’endroit des employeurs de l’industrie de la restauration rapide. Tout en considérant les emplois du secteur d’une manière négative, ils ne vont pas jusqu’à affirmer qu’ils causent du tort en longue période. Au contraire, une perspective de la précarité d’emploi considère le travail comme un moyen de gagner un revenu modeste sans implication dans le développement d’habiletés; elle voit le travail comme ennuyant et répétitif. Cette manière de raisonner caractérise ces emplois comme étant avant tout de court terme et n’indiquent pas qui seraient aptes à poursuivre des carrières dans l’industrie ou qui serait susceptibles de réussir dans un milieu de restauration rapide.

Ceux qui ont une vision plus positive de l’emploi dans l’industrie de la restauration rapide adoptent souvent une perspective de gestion ou de développement du commerce. Les écrits de ce type nous incitent à penser que le travail est source d’un curriculum vitae bonifié, d’occasions de se perfectionner et d’une possibilité de faire carrière. Ces arguments font valoir que tous ou presque tous les adolescents bénéficieraient d’un emploi dans la restauration rapide. Une telle vision théorique ne cherche pas à minimiser les perspectives alternatives de carrière et l’intelligence de ceux qui sont considérés comme de bons employés. Au contraire, c’est là une perception des travailleurs exemplaires, ceux qui font preuve d’initiative, d’optimisme et d’une bonne capacité relationnelle.

Des vues opposées concernant les bons emplois dans la restauration rapide arrivent à des conclusions différentes quant à la nature des personnes qui constituent la meilleure fournée d’employés du secteur. Ce sujet fait l’objet de discussions qui ne s’appuient pas souvent sur des données empiriques. Au contraire, les visions des caractéristiques des travailleurs exemplaires tirent leur origine des perceptions distinctes des emplois eux-mêmes. Elles ont tendance à retenir comme base les éléments suivants : des inférences tirées de conclusions de recherche quelque peu pertinentes, ou bien et également d’opinions et de controverses.

On retrouve trois raisons qui invitent à en savoir davantage sur ce qui caractérise un bon employé dans le secteur de la restauration rapide et qui convient à la poursuite d’une carrière dans l’industrie. Premièrement, une telle vision offre une possibilité de bonifier les politiques et les pratiques d’un employeur dans le domaine des relations du travail. Les dirigeants du secteur considèrent le roulement et l’inaptitude des salariés comme des défis clefs d’ordre opérationnel. Deuxièmement, les employés, au stade de l’adolescence, qui sont par conséquent à une étape critique de leur développement personnel et social, peuvent bénéficier d’une meilleure appréciation quant à savoir s’ils trouveront dans ce secteur un emploi valable et enrichissant et s’ils pourront faire carrière dans la même foulée. Troisièmement, comme on l’a déjà signalé, le statut d’étudiant est assailli par des opinions et des conjectures invitant à se demander si quelqu’un peut vraiment ou non être apte à poursuive une carrière dans la restauration rapide et présenter différents profils d’employés exemplaires.

Ce projet de recherche analyse la situation d’adolescents à l’emploi de restaurants McDonald en Australie. Il met en évidence le fait que l’industrie offre un type d’activité qui satisfait les besoins et les aspirations de certains individus plutôt que d’autres. La question de recherche se pose ainsi : quels sont les caractéristiques de ceux qui seraient aptes à travailler dans ce secteur ? Des enquêtes structurées en conjugaison avec des données tirées de l’analyse de régression et d’inférence statistique paramétrique ont servi à établir un profil du travailleur idéal. Nos conclusions indiquent qu’un changement au niveau du développement personnel et une tendance visible à choisir de faire carrière dans la restauration rapide deviennent des éléments importants au moment d’établir la compatibilité d’un employé. Dans les faits, ceci implique que la plupart des adolescents, ceux qui ont 14 ou 15 ans, se réjouissent de leur expérience de travail dans un établissement de restauration rapide. Cependant, seulement quelques adolescents plus âgés, par exemple ceux qui ont 17 et 18 ans, se disent aussi satisfaits. Il est donc possible d’établir une distinction entre celui qui est susceptible de continuer à apprécier son travail et celui qui ne l’est pas en posant la question suivante : souhaitez-vous poursuivre une carrière dans l’industrie ? Des observations démontrent que, lorsque les jeunes répondent à une telle question, ils ne le font pas de façon arbitraire. Au contraire, ils envoient un signal à l’effet qu’ils vont continuer à travailler dans le secteur et faire partie par la suite de la cohorte de travailleurs plus âgés qui se sont adaptés au milieu et qui sont heureux. De plus, les réponses à cette question peuvent servir à repérer la présence de caractéristiques distinctes. Par exemple, ceux qui donnent une réponse affirmative à la question indiquent également qu’ils préfèrent un travail simple et répétitif, qu’ils s’accommodent de l’attitude de leur employeur et de la culture du milieu de travail.

De telles observations viennent appuyer certains aspects d’une vision négative (en particulier, l’orientation à l’endoctrinement ou à l’exploitation) dans les commentaires sur la compatibilité des travailleurs avec le secteur. Cependant, à cause du penchant vers le travail de type McDonald associé à une vision personnelle de leurs aptitudes et de leurs préférences, un phénomène du genre « le travailleur débile de la restauration rapide est l’Homme de McDonald » peut induire en erreur.

Les observations, qui découlent de ce projet, comportent des effets pour la prise de décision des gestionnaires dans le secteur et présentent une vision empirique des points litigieux. Les résultats remettent en cause les stéréotypes négatifs à l’endroit de l’emploi dans la restauration rapide parce qu’ils mettent en évidence le fait que les adolescents à l’aise avec le secteur sont capables de réfléchir d’une manière stratégique et peuvent tirer des conclusions sur leur carrière.

Mots-clés:

- adolescents,

- travail rémunéré,

- emplois dans la restauration rapide,

- employé approprié,

- Australie

Resumen

Trabajo en la industria de comida rápida: una perspectiva empírica de los empleados ideales

La estrategia de gestión laboral de McDonald es generalizada en la industria de comida rápida. La literatura que critica este enfoque identifica este tipo de trabajo al empleo mal pagado, sin retos e ininteresante. Otros argumentan que los empleos de esta industria procuran buenas experiencias de trabajo, oportunidades de aprendizaje y posibilidades de carrera. En lugar de ser inherentemente desventajoso o benéfico, es posible que el empleo en la comida rápida corresponda a las necesidades y aspiraciones de algunos más que otros. Este artículo propone esta óptica respecto a los adolescentes. Se plantea la pregunta: cuáles son las características de las personas adecuadas al trabajo de esta industria? Se utiliza una encuesta para desarrollar un esbozo estadístico de los trabajadores ideales. Los resultados tienen implicaciones para la toma de decisión de los interesados y ofrece una perspectiva empírica de una cuestión litigiosa que atrae opiniones y especulaciones. Los resultados indican que el cambio evolutivo y una inclinación evidente a escoger una carrera en la comida rápida son consideraciones claves para determinar la adecuación del empleado.

Palabras claves:

- adolescentes,

- trabajo remunerado,

- carrera en la comida rápida,

- adecuación de los empleados,

- Australia

Corps de l’article

Introduction

The fast food industry gives many their first experience of paid work (Robinson, 1999: 4). McDonald’s is the largest firm in the sector. In Australia, where data for this study was collected, in 2007 it provided jobs for 56,000 people in its 730 stores.[1] Other Australian fast food industry firms have a combined national workforce of at least another 50,000 (Lyons, 1999: 4). They often adopt a McDonald’s-type approach to outlet operations, and aspects of labour management. Where practicable, multi-national fast food employers conduct operations similarly throughout the world (Love, 1995: 115). In certain countries, such as Germany and the United Kingdom, fast food workers may be older people who are drawn from the adult atypical labour market. Elsewhere, for example in Australia where this research was undertaken and in New Zealand, the majority of McDonald’s outlet workers are teenagers (Robinson, 1999: 4). In general, throughout the world including Australia, McDonald’s workers are not unionized. In this article, fast food restaurants will continue to be referred to as “outlets” and their non-management employees as “crew.”

There is conjecture in literature about who is suited to fast food employment (Kincheloe, 2002: 84). Some argue that those who thrive in the industry and/or show enthusiasm for their job are content with routine and simplicity, extraverted, compliant, and willing to do tasks uncritically (Royle, 2000: 67; Kincheloe, 2002: 84). They often do poorly at school, are shallow in their dealings with others, and are prone to engage in superficial conversations and relationships (Kincheloe, 2002: 84–85). By contrast, Schlosser (2002: 82) and Kincheloe (2002: 85) suggest that those who are “unsuitable” are disposed to question authority, analyze and discuss social issues and favour complexity and ambiguity over routine and simplicity. In the longer term, these crew are unlikely to be appointed to management positions at McDonald’s or to establish a career in the industry. This study analyzes the differences between teenagers who are suitable for fast food careers and those who are not. It identifies the characteristics of each group, considers how these develop, and proposes ways that current and prospective crew may be assessed as well matched for industry employment.

There are three reasons why it is important to gain a better appreciation of which individuals, amongst teenagers, may be suited to fast food work. First, such insight may assist outlet managers to improve appointment and promotion policy and practice. This is relevant because industry employers indicate that their principal employment relations concerns are high labour turnover and the possibility that many crew are de-motivated or unsuited to the work (McDonald’s, 1998: 2). Second, enhanced knowledge of who is suitable for fast food employment may assist prospective crew to better assess whether they will find a job in the sector fulfilling and worthwhile. This potentially allows teenagers to make decisions about how to allocate time and resources during a crucial phase of their social and educational development. Third, insofar as scholarship is concerned, the debate about suitability for fast food work is somewhat underdeveloped, rife with opinion and polemic, and, often not based on sufficient evidence, be it qualitative or quantitative. This project’s data and conclusions assist to remedy such problems.

Literature Review

One perspective of fast food crew suitability can be gleaned from considering two generic bodies of literature. The first addresses employee motivation and the second, non-standard/contingent work (Kalleberg, 2000: 341). Of the key contemporary ideas about motivation,[2] expectancy theory offers special insight into worker compatibility because it proposes individual difference in response to a job environment (House, Shapiro and Wahba, 1974: 481–506). Typically, this genre emphasizes that the potency of a desire to act in a certain way depends on the strength of an expectation that the act will be followed by a given outcome, and the attractiveness of that outcome. Job suitability is a key component of this conceptualization because “outcome attractiveness” is somewhat dependent on idiosyncratic perceptions (Robbins, 1997: 57–58). Insofar as the fast food industry is concerned, application of an expectancy theory perspective is influenced by varied teenaged motivations for working. Because crew jobs are typically part-time/casual, worker conceptions of job-reward, performance-reward linkage, and effort-performance-linkage[3] are modulated by competing priorities and interests such as study, social and sporting engagements, and recreational pursuits.

Insofar as fast food specific literature is concerned, discussion about crew compatibility with their outlet environment is mostly embedded in commentary about the nature of the work itself. Broadly, there are two views on this matter: negative and positive. In the remainder of this section, I present key themes in each of these genres and emphasize what each indicates about suitability for fast food employment. By way of summary, literature that is classed as “negative” generally indicates either that no one is especially suited to fast food work or, implies that those who are have moral and/or intellectual limitations. On the other hand, literature that is “positive” typically does not highlight a distinction between industry compatible crew and others and therefore does not cast aspersions on the sophistication of the former group. Rather, positive commentary on fast food labour management practices often indicates that all or most teenagers would benefit from a stint as a crew person.

Industrial sociology literature mostly presents negative perspectives of fast food labour management practice. The idea of exploitation is prominent in this genre. Those who emphasize that the employment is exploitative typically view crew jobs through the prism of scientific management. Such authors suggest that fast food work organization is subject to criticism that is also directed towards production-line factory employers. In particular, crew jobs are viewed as repetitive, intellectually unchallenging, boring and tedious (Ritzer, 1993: 8). Because it involves teenagers, the work may also have longer-term social consequences. For example, it may contribute to class inequality because it distracts young people from school and study commitments and mostly does not lead to a career or useful skill acquisition (Schlosser, 2002: 80). Employers prefer to use teenagers as crew because such workers typically have had limited experience with paid employment and cannot adequately assess whether they are being treated fairly and reasonably (Robinson, 1999: 9). Generally, they are prepared to toil in ways that older and more experienced workers would find unacceptable (Royle, 2000: 67; Schlosser, 2002: 68). Another, exploitation-related, advantage of employing teenagers is that, in many jurisdictions, younger people receive lower wages than adults doing equivalent work (Allan, Bamber and Timo, 2002: 164).

Authors who view fast food work as exploitative speculate about crew reactions to their employment and outlet environments. For example, crew may resign from their job after a short time (Royle, 2000: 70). Schlosser (2002: 75) suggests that such turnover is, at least partly, contrived by managers to ensure that unions do not infiltrate the workplace. On the other hand, there are three categories of exploitation-type arguments that account for crew who do not resign. First, employers may burn out their workforce. In practice, this means that young people commence their job with an enthusiasm that compels them to continue. Eventually they come to dislike the work because they are tired, frustrated and/or believe that they have been duped and misled by managers who promise benefits, including promotion and advancement, which are not delivered. In these circumstances, teenagers become confused about the merits of their vocation and display anxiety/stress reactions. Second, crew believe that their jobs are somewhat exploitative but are convinced by their employer that fast food work is coveted and worthwhile (Garson, 1988: 12; Leidner, 1993: 44, 55; Royle, 2000: 59; Schlosser, 2002: 76–81). Such a conception has its origins in the Marxist idea of false-consciousness (Caplow, 1964: 199). Third, some people are content with routine and simplicity and are inclined to do tasks and work in ways that fit with a McDonald’s culture (Kincheloe, 2002: 85). By inference, such crew are, somewhat patronizingly, viewed as unable to assess their own interests.

According to the exploitation perspective, of the four possible reactions that crew may have towards their job—exit (turnover), burnout, indoctrination and compatibility—only the latter emphasizes a distinction between suitable and non-suitable crew. This distinction appears to be influenced by the views of Ray Kroc, the founder of McDonald’s, who favoured especially compliant workers. He believed that certain young people are inclined to be conformist, uninterested in higher education, shallow, uninformed and content to accept the surface meaning of things they encounter (Royle, 2000: 67; Kincheloe, 2002: 84). Crew at McDonald’s should “keep their noses clean”, “look straight ahead” and “not question the avalanche of corporate rules that all McDonald’s managers and executives must follow” (Kincheloe, 2002: 85). Elsewhere, it is argued that crew who do well are unfailingly pleasant, cheerful, smiling and courteous (Royle, 2000: 63–64; Solomon, 1997: 42–43). Kroc originally proposed the idea of the “McDonald’s man” or “the guy with ketchup in his veins” as an ideal fast food employee (Kroc, 1987: 98).

Another negative view of fast food employment, the stop-gap perspective, categorizes crew jobs as having features of scientific management but does not go so far as to label them exploitative. These arguments typically suggest that the work is the embodiment of a trade-off between repeatedly doing a few mundane tasks and one’s immediate material needs and wants. Stop-gap work is short term and unlikely to culminate in a career (Tannock, 2001: 4–10). Many crew do not rely on an income for a livelihood, have part-time or causal employment contracts, have multifaceted lives involving education sporting and social commitments and, are less likely than those in other industries to view their job as integral to a sense of identity or as a source of self-esteem (Mortimer et al., 1996: 1405; Smith and Wilson, 2002: 121; Tannock, 2001: 110). Some conceive of these types of employment arrangements as a “coincidence of needs” (Lucas and Curtis, 2001: 41). In practice, this means that if, in an employee’s judgment, work provides money and is not overly burdensome or disruptive to their lifestyle, they will indicate a short-term commitment to it. This view implies that labour turnover is higher when employment displays “stop-gap” characteristics. Commentary that takes a stop-gap perspective generally does not present a distinction between suitable and not suitable employees. Because the genre assumes that such work is short-term, at least insofar as it relates to teenagers, notions of organizational compatibility are less relevant.

In contrast to the negative view, authors emphasizing employer or commercial-development perspectives argue that all or most teenagers would benefit from a stint as a crew person. In this article, such literature is referred to as the positive view of industry jobs. For example, some argue that the opportunity to be employed at a fast food outlet can be a career advantage (Daniels, 2004: 137; Feder, 1995: 46; Smith and Wilson, 2002: 128). This reasoning has several themes. First, it is suggested that many teenagers find it difficult to access the job market other than through fast food employment (Allan, Bamber and Timo, 2002: 166). The Industry is comprised of large multinational employers and their employees might be in a position to observe cutting-edge management practice and possibly develop effective work habits and attitudes towards employment (Feder, 1995: 46; Morse, 1997: 19). Such a chance to see the way McDonald’s runs its outlets may have positive consequences for a teenager’s self-development and future employability (DiNome, 2001: 25; Goldeen, 2004: 2). Fast food employment may provide crew with career paths. For some, it is possible to commence employment in a menial role and rise through a hierarchy without conventional forms of education or a diverse work history (Cantalupo, 2003: 21). For example, the former Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of McDonald’s in North America, Charlie Bell, started his career as a 15 year old crew person in suburban Sydney. Although anecdotes of this kind make no explicit distinction between suitable and unsuitable crew, they do imply that those who thrive in the industry are self-motivated, career-orientated, positive thinking, and with good communication skills.

Positive-view literature about fast food labour management offers a different interpretation of crew turnover. Rather than being contrived by outlet managers, turnover is viewed by them as a key operational problem and as an incentive to make the work more attractive (McDonald’s, 1998: 14). This genre appears to be influenced by generic theory which portrays the phenomenon of untimely worker exit as an employer problem and as a manifestation of poor employee/organizational compatibility. For example, if an employer’s values, attitudes and aspirations are incongruent with those of an employee, the employee may engage in workplace withdrawal behaviour, including resignation (Fields, 2002: 89).

In this article, I present data that indicates that fast food employment suits certain teenagers more than others. I argue that most who work in the industry when they are in their early teens will experience, at least, a brief period of fondness for their job. For some, this will be sustained and associated with benefits. For others, it will be replaced by adverse perceptions and disadvantages. This phenomenon cannot be completely reconciled with negative view literature which often suggests that the industry generally, and in all or most cases, has a detrimental effect on its workforce. Rather, I propose an alternative conception. The research question is: How can one differentiate between those crew who are suitable for fast food employment and others who are not?

Methodology

The study used a mix of qualitative and quantitative strategies. McDonald’s Australia gave the researcher permission to enter company-owned outlets, and to ask crew and managers to participate in focus groups and to complete questionnaires. McDonald’s had no editorial control over the project.

Research Design

Three methods were used to identify crew who may be suitable for fast food work and to distinguish between these individuals and their non-suitable peers. The techniques were focus groups, observation and structured surveys and quantitative analysis of data. The first two techniques were used to generate hypotheses about who may be suitable for fast food work. The last technique, which formed the substance of the analysis, was used to test hypotheses. Figure 1 depicts the study’s design.

Figure 1

Design of the Study

Instruments and Measures

Focus groups. Two 45-minute crew focus groups with six to eight participants were used to formulate hypotheses about who may be suitable for crew work. Participants were asked open-ended questions about aspects of their work. Focus group sessions mostly involved initial and supplementary questions, for example:• What’s the best thing(s) about working in a fast food outlet? What’s the worst thing(s) about the work?• What do you think about the way your work is organized? If you were in charge, would you do things differently?• Can you tell me about the benefits and entitlements you get with the job? What’s good and bad about these?• What do you know about the way unions operate at McDonald’s? Do you think there should be any changes to this?

Focus group questions were mostly intended to establish if participants viewed their employment with positive or negative sentiment and whether they were satisfied or dissatisfied with the job. Other focus group questions asked participants about themselves. These queries were general in nature. They encouraged discussion of interests, hobbies, ambitions and personalities. Examples included: Could you tell me about yourself? Do you go to school? What are your interests and hobbies? What would you like to be doing in five years’ time? Focus group results were recorded on audiotape.

Participant observation. In addition to focus groups, participant observation was used to create hypotheses about who is suitable for fast food work. The researcher worked at a suburban Brisbane McDonald’s outlet for two weeks during March 2003. The researcher made notes about those who liked their job and seemed adapted to the experience. During break times, the researcher spoke with crew about aspects of their lives and employment.

Surveys. A structured survey was developed[4] and administered to a sample of McDonald’s crew throughout Australia. The sample was intended to be representative of those employed in Australia by multinational fast food chains. Survey items mostly used Likert scales and assessed crew orientation towards work-related variables and established whether crew would like to be employed at McDonald’s in the longer term.

Analysis

Focus groups and participant observation. Prior to the main part of the study, focus group results were analyzed. Each time a participant said something about crew compatibility with fast food work or about the kind of person who would be likely to stay and develop a career in the fast food industry, this was noted. Subsequently, ideas were organized according to themes. A similar approach was taken to the participant observation exercise, although without a recording device. Focus groups and participant observation themes were later compared with those in literature.

Surveys. Crew survey data was used to test hypotheses that were generated using qualitative methods. A stratified random sampling strategy was used to administer surveys. This involved defining urban and regional areas of the Australian mainland and randomly sampling from within these. The objective was to obtain completed surveys from 1000 McDonald’s crew, a statistic that represents about two percent of the overall workforce. Survey data was analyzed using regression analysis and parametric inferential procedures including analysis of variance (ANOVA), bi-variate correlation, and t-tests.

Limitations

Focus groups and participant observation. Focus groups were small and limited to 45-minute sessions. Crew initially appeared uncomfortable about talking to the researcher. It is possible that crew may have believed that their comments would be perceived negatively by their peers or outlet managers. This criticism may also be made, although to a lesser extent, about the participant observation exercise.

Surveys. Inferences were made throughout the study. The key ones were: 1) a disparity between how a job is perceived and how a worker would prefer it to be, is evidence of dissatisfaction;[5] and 2) job satisfaction is a substitute measure of job compatibility. Conjecture of this kind has face-validity but requires a researcher to infer the presence of a primary phenomenon from knowledge of an index factor. A further survey design limitation was that, in general, only one item was used to address each element of work and employment. This meant that techniques such as factor analysis could not be used to verify the presence of underlying constructs. In this regard, a decision was made to trade-off content for methodological rigour.

Results

Data were collected from 812 crew and 55 outlets. Hypotheses were tested using results from the structured survey. The following hypotheses were established a priori:Hypothesis 1: Crew who want to have a career with McDonald’s can be distinguished from those who do not.Hypothesis 2: Crew who want to have a career with McDonald’s maintain enthusiasm for their employer whereas crew who do not want to have a career with McDonald’s show diminishing enthusiasm for their employer over time.

Hypothesis 1

Analysis. A bimodal distribution was obtained for crew frequency data for the survey proposition: “In five years’ time, I would still like to be employed at McDonald’s.” These data are represented in Figure 2.

Underlying data in Figure 2 are two kinds of crew: those who want to have a career with McDonald’s and those who do not. Logistic regression was used to predict each of these categories. To undertake this analysis, data were recoded to reflect the binary nature of the distinction suggested in Figure 2’s histogram. Recoding was done by combining: strongly disagree and disagree categories; agree and strongly agree categories; and, excluding from consideration the neutral category. This resulted in 72 percent of participants indicating that they do not want a career at McDonald’s (n = 362) and 28 percent indicating that they do (n = 261).[6]

Figure 2

Crew Preference for a Career at McDonald’s, McDonald’s, May 2003 (preference, number)

The following variables were predictors for logistic regression.[7]1.1 I like doing complicated tasks at work: Ntotal = 779 {(sd = 12.6% (n = 18); d = 5.6% (n = 44); n = 45.3% (n = 353); a = 27.0% (n = 21); sa = 19.8% (n = 154)}1.2 Whilst on shift, I enjoy talking a lot with other crew: Ntotal = 791 {(sd = 6.8% (n = 54); d = 8.6% (n = 68); n = 17.8% (n = 41); a = 28.8% (n = 22); sa = 37.9% (n = 300)}1.3 I enjoy the challenge of dealing with unusual situations at work: Ntotal = 778 {(sd = 2.3% (n = 18); d = 11.6% (n = 90); n = 18.3% (n = 140); a = 49.2% (n = 383); sa = 18.9% (n = 147)}1.4 I prefer to deal with problems without asking my manager: Ntotal = 773 {(sd = 12.8% (n = 99); d = 24.5% (n = 189); n = 23.0% (n = 178); a = 22% (n = 172); sa = 15.5% (n = 135)}

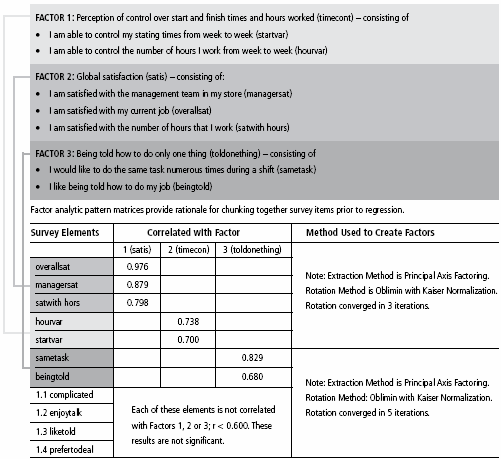

In addition to the above mentioned single-element items, factor analysis was used to combine conceptually related survey statements into single orthogonal factors. Figure 3 indicates how the categories of “perception of control over start and finish times,” “global satisfaction” and, “being told how to do one thing” were created in this way. A pattern matrix, shown in the lower half of the figure, indicates how survey items correlate with each factor created by the analysis. For independent variables (predictors) entered into the equation, inter-correlations are low and not significant. Hence, multicollinearity is within acceptable limits.

Figure 3

Combining Survey Items into Factors Prior to Factor Analysis(Items are combined because they are correlated and appear to be indexing the same underlying idea)

Logistic regression is a derivative of standard regression[8] and predicts category membership. As with standard regression, R and R2 statistics measure the aggregate predictive ability of the equation.[9] A regression model which establishes factors 1, 2 and 3 and survey items 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, and 1.4 as independent variables predicts 68 percent of the variance of crew scores when wanting to have a career with McDonald’s was established as the dependent variable. An F-test (ANOVA) indicates that this was a significant result and therefore, that findings may be generalized to McDonald’s, and possibly to other fast food crew throughout Australia.[10]

The classification table presented in Table 1 indicates the regression analysis’ predictive capacity. Factors established in Figure 3 as non-correlated independent variables have predicted with approximately 99 percent accuracy who wants to work at McDonald’s in five years’ time and with 86 percent accuracy who does not. This result represents a mean prediction rate of approximately 94 percent.

Table 1

Classification Table for Regression Addressing Who, amongst Crew, Would Like to Work at McDonald’s in FiveYears Time, McDonald’s, May 2003 (observed, predicted)

Observed |

Predicted |

|||

Wanting a career recoded to binary |

Percentage correct |

|||

|

Do not want career (n - predict = 366) |

Do want career (n - predict = 226) |

|

||

"Want a career" recoded to binary |

Do not want career (n-o = 362) |

|

|

362/366 = 99% (approx) |

|

Do want career (n-o = 261) |

|

|

226/261 = 86% (approx) |

Overall Percentage |

|

|

|

94 percent (approx) |

a The cut value is .500; Percentages are calculated by making the smaller number the numerator and the larger number the denominator.

Data presented in Table 2 indicate the unique contribution made by individual independent variables to the prediction of who, amongst crew, wants to work at McDonald’s in five years’ time. Wald’s statistics were used to assess significance in each case using an alpha value of 0.05 (α = 0.05).[11] The following conclusions are conservative interpretations of Table 2’s data.* Crew who report they cannot control their start and finish times and the number of hours that they work are very slightly and non-significantly likely to indicate that they do not want to work at McDonald’s in five years’ time.* Crew who indicate that they enjoy doing complex tasks at work are very slightly, and non-significantly, likely to indicate that they do not want to work at McDonald’s in five years’ time.* Crew who are generally satisfied with their employer, like talking to others whilst on duty, enjoy the challenge of dealing with unusual situations at work, prefer to deal with problems without asking their manager and, enjoy doing the same thing repeatedly are significantly likely to report that they want to work for McDonald’s in five years’ time.

Table 2

Variables Used to Predict Who Wants to Work at McDonald’s in Five Years Time, McDonald’s, May 2003(significance statistics)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

95.0% C.I. for EXP (B) |

|

|

|

B |

S.E. |

Wald |

df |

Sig. |

Exp(B) |

Lower |

Upper |

Step 1(a) |

Timecont |

-.140 |

.142 |

.971 |

1 |

.324 |

.869 |

.658 |

1.148 |

Satis |

.951 |

.215 |

19.573 |

1 |

.000 |

2.587 |

1.698 |

3.942 |

|

Complicate |

-.124 |

.183 |

.457 |

1 |

.499 |

.884 |

.617 |

1.265 |

|

Talkalot |

.957 |

.145 |

16.993 |

1 |

.000 |

1.817 |

1.368 |

2.414 |

|

Unusual |

1.077 |

.180 |

35.893 |

1 |

.000 |

2.937 |

2.064 |

4.177 |

|

Withoutask |

.781 |

.135 |

33.400 |

1 |

.000 |

2.184 |

1.676 |

2.846 |

|

Toldonething |

1.006 |

.178 |

32.109 |

1 |

.000 |

2.736 |

1.931 |

3.875 |

|

Constant |

-15.196 |

1.410 |

116.151 |

1 |

.000 |

.000 |

- |

- |

a Variable(s) entered on step 1: TIMECONT, SATIS, COMLICATE, TALKALOT, UNUSUAL, WITHOUT, TASKSIMP.

Conclusion. McDonald’s outlets employ crew who do want to work there in five years’ time, and others who do not. Compared with crew who indicate that they do not want to be employed by McDonald’s in five years’ time, those who seek long term employment are: generally more satisfied with their employer and embrace the McDonald’s culture; satisfied, in particular, with the number of hours they work and their start and finish times; like talking to others whilst on duty; enjoy the challenge of dealing with unusual situations; and, prefer to deal with problems without asking their manager. People who want to work at McDonald’s in five years’ time also like doing fewer and less complex tasks. These findings are obtained from crew of all ages, irrespective of their length of service or gender.[12] Provided a crew person indicates that they would like to have a career with McDonald’s, they will be significantly more likely to fit the aforementioned profile, irrespective of their other circumstances.

Hypothesis 2

Analysis. Crew who do and do not want to have a career with McDonald’s were separated from their peers based on a binary response to the proposition: “In five years’ time I would still like to work at McDonald’s”[13] (see Figure 2). The two groups were then separately examined in analyses that considered the relationship between six global and specific measures of satisfaction[14] as a dependent variable, and age as an independent variable. This analysis is depicted in Tables 3 and 4, which provide correlation coefficients between age and measures of embrace of aspects of employment relations at McDonald’s.

Table 3

Correlation between Crew Age and Crew Views about Aspects of Employment Relations, McDonald’s,May 2003 (correlation and significance statistics)

Human Resource Management Variable |

Survey Statements |

Type of Crew |

Correlation Coefficient with age |

Significance |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

For Coefficient with Age |

Between type of Crew |

||||

Embrace of Culture Measure |

Embrace of organizational- culture as measured through factor created from high correlation between quality, service, value and cleanliness |

Crew who want to have a career |

r = 0.05 |

Signif (α = 0.05) |

Between subjects ANOVA analysis signif (α = 0.05) |

Crew who do not want to have a career |

r = -0.02 |

Signif (α = 0.05) |

|||

Embrace of Global Satisfaction Measure |

Satisfaction measure created from factor analysis Items used to create the factor are: "Overall I'm satisfied with my current job", and "Overall, I'm satisfied with the management team in my store" |

Crew who want to have a career |

r = 0.6 |

Signif (α = 0.05) |

Between subjects ANOVA analysis signif (α = 0.05) |

Crew who do not want to have a career |

r = -0.7 |

Signif (α = 0.05) |

Table 3a presents response data (raw scores and percentages) for the survey items that were used to create the two factors presented in Table 3.[15]

Table 3a

Frequency Data and Percentages for Survey Items Used to Produce Analysis in Table 3(all n values are less than 812 due to missing data)

Survey Element |

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

McDonald's only sells quality products |

3.6% |

11.8% |

20.6% |

27.3% |

36.7% |

(n = 787) |

(n = 28) |

(n = 93) |

(n = 162) |

(n = 215) |

(n = 289) |

McDonald's stores always have high standards of service |

3.7% |

9.1% |

15.7% |

30.4% |

41.2% |

(n = 784) |

(n = 29) |

(n = 71) |

(n = 123) |

(n = 238) |

(n = 323) |

McDonald's stores are always very clean |

2.4% |

12.1% |

18.9% |

27.1% |

39.5% |

(n = 794) |

(n = 19) |

(n = 96) |

(n = 150) |

(n = 215) |

(n = 314) |

Overall, I am satisfied with my current job |

2.7% |

10.2% |

18.8% |

32.0% |

36.3% |

(n = 787) |

(n = 21) |

(n = 80) |

(n = 148) |

(n = 252) |

(n = 286) |

Overall, I am satisfied with the management team in my store |

2.8% |

10.7% |

18.4% |

28.8% |

39.3% |

(n = 787) |

(n = 22) |

(n = 84) |

(n = 145) |

(n = 227) |

(n = 309) |

Conclusions from Table 3’s data are:

Crew who indicated that they wanted to have a career with McDonald’s embrace elements of the organizational culture as they become older.[16] Crew who indicated that they do not want to work at McDonald’s in five years’ time show lesser growth in commitment to and compatibility with organizational culture as they became older. These effects are small but significant.

Crew who indicated that they wanted to have a career with McDonald’s showed increasing satisfaction with their employer as they became older. This effect is also apparent for crew who indicated that they do not want to have a career with McDonald’s.

Between-subjects ANOVA analyses indicate that, for both “embrace of culture” and “global satisfaction”, those who do not want a McDonald’s career are significantly more compatible with the outlet environments than those who do.

In addition to global measures of culture and satisfaction, some discrepancy measures are compared for crew who do and do not want to have a career with McDonald’s. These are documented in Table 4. Discrepancy assessed age-related trends for specific aspects of satisfaction with McDonald’s work.

Table 4

Correlation between Crew Age and Crew Views about Aspects of Labour Management, McDonald’s,May 2003 (discrepancy score, significance statistics)

Variable |

Type of Crew |

Survey Statements Used to Calculate Discrepancy* |

Correlation between discrepancy and Age |

Signifcance |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

For Coefficient with Age |

Between types of Crew |

||||

Task Sameness |

Those who want a career |

I do exactly the same task through my shift - I would like to do the same task through my shift = discrepancy score variable |

r = 0.1 |

Not signif (α = 0.05) |

Between subjects ANOVA analysis signif (α = 0.05) |

Those who do not want a career |

I do exactly the same task through my shift - I would like to do the same task throughmy shift = discrepancy score variable |

r = 0.2 |

Not signif (α = 0.05) |

||

Task Complexity |

Those who want a career |

The tasks I do at work are complicated - I like doing complicated tasks at work = discrepancy score variable |

r = 0.0 |

Not signif (α = 0.05) |

Between subjects ANOVA analysis signif (α = 0.05) |

Those who do not want a career |

The tasks I do at work are complicated - I like doing complicated tasks at work = discrepancy score variable |

r = 0.4 |

Signif (α = 0.05) |

||

Dealing with Problems |

Those who want a career |

When a minor problem occurs at work I deal with it without taking it to my manager - When a problem occurs at work I would prefer to deal with it without taking it to my manager = discrepancy score variable |

r = 0.1 |

Not signif (α = 0.05) |

Between subjects ANOVA analysis signif (α = 0.05) |

Those who do not want a career |

When a minor problem occurs at work I deal with it without taking it to my manager - When a problem occurs at work I would prefer to deal with it without taking it to my manager = discrepancy score variable |

r = 0.3 |

Not signif (α = 0.05) |

||

Unusual Situations |

Those who want a career |

Whilst on shift I am expected to find ways of dealing with unusual situations - I enjoy the challenge of dealing with unusual situations at work = discrepancy score variable |

r = 0.6 |

Signif (α = 0.05) |

Between subjects ANOVA analysis signif (α = 0.05) |

Those who do not want a career |

Whilst on shift I am expected to find waysof dealing with unusual situations - I enjoythe challenge of dealing with unusual situationsat work = discrepancy score variable |

r = 0.0 |

Not signif (α = 0.05) |

*: Dissatisfaction is inferred from discrepancy.

Table 4a presents response data (raw scores and percentages) for the survey items that were used to create the two factors presented in Table 4.[17]

Table 4a

Frequency Data and Percentages for Survey Items Used to Produce Analysis in Table 4(all n values are less than 812 due to missing data)

Survey Element |

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

I do exactly the same task through my shifts |

7.0% |

13.7% |

14.6% |

13.9% |

50.8% |

(n = 786) |

(n = 55) |

(n = 108) |

(n = 155) |

(n = 109) |

(n = 399) |

I would like to do the same task during a shift |

16.8% |

27.6% |

17.9% |

33.4% |

4.3% |

(n = 782) |

(n = 131) |

(n = 216) |

(n = 140) |

(n = 261) |

(n = 34) |

The tasks I do at work are complicated |

21.5% |

37.8% |

32.6% |

5.1% |

3.0% |

(n = 800) |

(n = 172) |

(n = 302) |

(n = 261) |

(n = 41) |

(n = 24) |

I like doing complicated tasks at work |

2.3% |

5.6% |

45.3% |

27.0% |

19.8% |

(n = 779) |

(n = 18) |

(n = 44) |

(n = 353) |

(n = 210) |

(n = 154) |

When a minor problem occurs at work, I deal with it without taking it to my manager |

12.7% |

18.2% |

17.3% |

32.7% |

19.1% |

(n = 790) |

(n = 100) |

(n = 144) |

(n = 137) |

(n = 258 |

(n = 151) |

When a problem occurs at work, I would prefer to deal with it without asking my manager |

12.8% |

24.5% |

23.0% |

22.3% |

15.5% |

(n = 773) |

(n = 99) |

(n = 189) |

(n = 178) |

(n = 172) |

(n = 135) |

Whilst on shift, I am expected to find ways of dealing with unusual situations |

15.4% |

15.5% |

24.0% |

40.8% |

4.2% |

(n = 779) |

(n = 120) |

(n = 121) |

(n = 187) |

(n = 318) |

(n = 33) |

I enjoy the challenge of dealing with unusual situations at work |

2.3% |

11.6% |

18.3% |

49.2% |

18.9% |

(n = 778) |

(n = 18) |

(n = 90) |

(n = 140) |

(n = 383) |

(n = 147) |

Conclusions from Table 4 are:

Crew who do not want to have a career with McDonald’s, as they get older, become slightly less satisfied with the extent to which they have to do the same task. Older crew, who do not want to have a career with McDonald’s, increasingly indicate a discrepancy between the way they perceive work and their ideal state vis-à-vis task sameness. This discrepancy is consistently in the direction of wanting a greater range of tasks to do at work. Such a pattern is the same but slightly less pronounced for crew who do want a career with McDonald’s: for this group, there is a greater tendency towards enduring satisfaction with task sameness.

As they get older, crew who want to have a career with McDonald’s remain satisfied with the extent to which tasks are complex. Discrepancy scores for career-committed crew indicate a systematic tendency for such individuals to view their work as close to ideal with respect to task-complexity, irrespective of their age. This trend contrasts sharply with equivalent data for crew who do not want to have a career with McDonald’s. As non-career orientated crew get older, they come to be increasingly dissatisfied with work-task complexity.

Crew who do want a career with McDonald’s, irrespective of their age, indicate minimal discrepancy between perception and preference about independently dealing with workplace problems. Over this issue, discrepancy between perception and preference for those who do not want a career with McDonald’s increases markedly as crew get older.

There is an age-related growing discrepancy between perception of and preference for dealing with unusual circumstances for crew who do not want to have a career with McDonald’s. No such systematic increase in this disparity is revealed for crew who do want to have a career. This data is ambiguous and therefore is not accorded great importance. For example, it could indicate either: that crew deal with unusual situations more than they would like to, or that they do not deal with unusual situations as much as they would like to.

For each of the four analyses presented in Table 4, between subjects ANOVA results were significant indicating that, for each discrepancy measure examined, those who want to have a career are significantly more likely to indicate higher preference alignment than those who do not want a career.

Conclusion. Crew who do want to have a career with McDonald’s maintain enthusiasm for their employer and satisfaction with several aspects of their job. Crew who indicate that they do not want to have a career with McDonald’s show diminishing enthusiasm for, and satisfaction with, their job over time. These effects are particularly apparent for age, indicating that crew who want to work for McDonald’s in the long term, irrespective of how old they are, maintain enthusiasm for their job. Conversely, older crew who do not want to work for McDonald’s in five years’ time indicate a more jaundiced view of their work. The trend could not be replicated when length of service was the independent variable. Because the phenomenon seems mostly to be age-related, it is likely to indicate the presence of a type of person who responds to a McDonald’s work experience throughout their teen years. Such individuals want to work for McDonald’s in the long term. Crew who indicate that they do not want to work for McDonald’s will, if they are younger, show relatively high levels of enthusiasm and commitment but, as they become older, systematically indicate less. Age related data about “unusual situations” is somewhat ambiguous.

Discussion

Focus groups and the participant observation exercise revealed that some crew are happy with aspects of their job. Often participants expressed a positive view of the way work is organized, and most indicated that they are treated well and have access to training and human resource-related advantages. The majority of those who are unhappy are older, about 18. Some of these less content crew indicated that their job was boring, overly rountinized and intellectually unchallenging. This group mostly believed that they were treated well by their employer. However, they often seemed engrossed in their schoolwork, concerned about future study goals or preoccupied with the next phase of their life.

In this discussion, I present a model of crew compatibility with McDonald’s-type work (Figure 4) and contrast this with a representation of negative-view industrial sociology literature (Figure 5). Each of these schematics establishes a different independent variable as crucial to understanding: the former emphasizes age and, the latter, length of service. Age is defined as a person’s chronological age. For analytic purposes, it typically means 14 through to 19 years old, measured in months. Length of service is the number of months a crew person has been employed. In the fast food industry, crew age and length of service typically have a low correlation.[18] This is because the sector is beset with high labour turnover and when a crew worker leaves, they may be replaced with an older person.

Some McDonald’s crew indicate that they want to work for the firm in the long term and others do not. Those in the former category typically manifest high levels of enthusiasm and positive sentiment towards their job when they are young and, as they become older, maintain such keenness. Crew not seeking a career in the fast food industry typically are content with their job when they are younger but, with age, become less so. In practice, this means that 14 or 15 year olds may indicate that they do not want to have a fast food career but mostly enjoy the experience of outlet work. However such crew, when they reach 17 or 18, are unlikely to judge their work as enhancing their lives but rather are inclined to see it as negative. On the other hand. those who are 17 or 18, and who indicate that they would like to have a fast food career, are typically content with aspects of their job. This pattern of findings about who enjoys McDonald’s-type work gives rise to the idea of divergence, depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Divergence View of Crew Change in Attitude / Orientation to Fast Food Work: Age as the IndependentVariable and Career-Committed Crew Maintaining Satisfaction

The divergence view of crew suitability emphasizes an employee’s age rather than their length of service. This means that a person in their late teens who has recently commenced at McDonald’s and does not want a career with the firm is as likely to indicate job dissatisfaction as someone who has been in the industry for several years and also does not want a fast food career. Such a phenomenon suggests development as a cause rather than, for example, attitude changes that are caused by learning. A mainstream psychological definition of learning is a permanent change in behaviour that comes as a consequence of experience (Vaughan and Hogg, 2002: 478). This is to be distinguished from developmental/maturational changes that are independent of a person’s experience.

This study’s findings are at odds with views that indicate that fast food crew attitudes and orientation towards employment are substantially influenced by the work environment. Certain of these learning-oriented perspectives, such as burnout and indoctrination, were referred to in the introduction as belonging to the negative view/exploitation genre of fast food work. Such views de-emphasize age as the reason crew change their perception of fast food work. Instead, they propose learning or the influence of experience as causing worker dissatisfaction. As noted in the literature review, burnout and indoctrination often downplay the role of individual differences and mostly conclude that McDonald’s work will disadvantage all crew. I have summarized the ideas of negative view/exploitation literature in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Negative View of Crew Work: Length of Service as the Independent Variable and all Crew BecomingLess Satisfied and / or Disadvantaged

This study’s results cannot be reconciled with developmental change alone, but reflect a tendency for some people to be the “right type” for a crew person. Consistent with the view presented in Figure 5, I interpret findings through proposing that some possess an enduring set of “industry-suitable” characteristics. This implies an inherent difference between those who are well matched to fast food work and their peers who are not. Such a difference is not apparent in late childhood, but rather is evident in late adolescence.

The idea of developmental change in attitude and orientation is common in literature addressing aspects of adolescent psychology. A prominent theorist in this area is Erickson who uses the term psychosocial development to identify immutable life stages through which one passes. Each of these gives rise to a qualitatively different state with respect to interests, affiliations and psychological orientation (Erikson, 1963: 25). Erickson views adolescence as a time when teenagers struggle to form a sense of personal identity, in particular. This view allows for the possibility of individual difference, and accommodates the prospect of a spectrum of distinct ways of developing.

The study’s results have implications for fast food outlet managers. They suggest that, in a general sense, younger teenagers are more inclined to enjoy the experience of working in the industry. To the extent that satisfaction with one’s work leads to enhanced productivity,[19] this finding proposes that, 14 to 15 year olds will be more suited to the work than 17 or 18 year olds. This result alone can not be used to address labour turnover. Fifteen year olds, despite perhaps being satisfied with their job, will probably soon turn 16 and, when this happens, may start to lose interest in fast food employment. The outlet manager needs to know who, amongst 15 year olds, will remain committed and enthusiastic about their work. The study’s data provides an important insight here. A feature of the divergence model presented in Figure 4 is that, irrespective of an employee’s age, if a crew person says that they would like to be employed at McDonald’s in five years’ time, they are likely to be satisfied with the work and remain content. The regression analysis undertaken for hypothesis 1 supports this conclusion because, as previously noted, it indicates that age is not significant in predicting who wants to be employed at McDonald’s in five years’ time.

A more subtle management implication of this study’s findings concerns the reliability of asking young persons if they would like a career in the fast food industry or are interested in working at McDonald’s in five years’ time. Whilst working in an outlet, I found that many managers are skeptical about whether this would yield useful information. They thought that teenagers will either attempt to give an answer that makes a good impression, not have thought about the issue and make up an arbitrary response or, appear to be confused and non-committed. These perceptions of teenagers suggest that they are not capable of thinking strategically about their future or possibly not able to make thoughtful career choices. This project’s findings suggest a different view. In particular, regression modeling indicates that young people from their early teens appear to have insight into whether they will be suited for their fast food job in the long term. Whilst they are not necessarily inclined to say that, over the course of the next few years they will maintain or lose satisfaction with the job, they can reveal if they are compatible with the work.

Conclusion

This study presents two conclusions about crew compatibility with fast food work which add to what is known about crew compatibility with their outlet environment and employer’s approach to labour management. First, for each crew age group (within the teenaged years), there appears to be consistently a high proportion who do not want a fast food career and a lesser—but still large—minority who do. Second, teenaged views about this are not arbitrary but represent a good predictor of compatibility with the fast food approach. These insights suggest that young crew are capable of making sound career choices and their decisions will endure through time. Hence, whilst all or most younger teenagers may enjoy a fast food work experience, it is only those who want a career who manifest long-term compatibility with their employer’s approach.

Parties annexes

Note biographique

Anthony M. Gould

Professor at the Industrial Relations Department, Université Laval, Québec, Québec.

Notes

-

[1]

See McDonald’s website: <http://www.mcdonalds.com.au/HTML/inside/company.asp>.

-

[2]

For example, three needs theory (McClelland, 1975), goal-setting theory (Locke and Latham, 1990), reinforcement theory (Luthans and Kreitner, 1984), equity theory (Mowday, 1991), etc.

-

[3]

Key concepts in expectancy theory (Robbins, 1997: 57–58).

-

[4]

Steps in development were drafting items, pre-testing items and piloting the survey.

-

[5]

Although the survey also included items that have a more direct association with job satisfaction.

-

[6]

Percentages calculated after excluding 143 neutral cases.

-

[7]

Ntotal refers to the total number of crew who responded to the item. Data in parentheses refers to variable percentage values and raw scores for items measured using an ordinal Likert-scale semantic-differential with five categories ranging from strongly disagree (sd) to strongly agree (sa). For ease of interpretation, means and standard deviations are not reported (ordinal data).

-

[8]

Regression with one continuously scaled (interval or ratio) dependent variable.

-

[9]

R is a measure of the fit of the regression model or the extent to which the independent variables have been effective in predicting scores on the dependent variable. R2 is a measure of the model’s predictive capacity or the extent to which knowledge of scores on the independent variable can be used to predict scores on the dependent variable.

-

[10]

To the extent that work is done in the same way in different multinational fast food chains.

-

[11]

Type-1 error rate.

-

[12]

Age, length of service, and gender were not significant in the analysis.

-

[13]

Advantage is taken of the bimodal nature of the distribution. Continuous scores were recorded into binary “do” and “do not” responses, to undertake this analysis.

-

[14]

With some of these elements, satisfaction is inferred from positive sentiment.

-

[15]

For ease of interpretation, means and standard deviations for each variable are not presented (ordinal data).

-

[16]

Factor analysis was used to establish that culture is a construct embracing survey items addressing planned elements of the McDonald’s image such as quality, service, value, and cleanliness and perception of the way one is treated by managers.

-

[17]

For ease of interpretation, means and standard deviations for each variable are not presented (ordinal data).

-

[18]

In this study it was found to be r = 0.2 for the sample of 812.

-

[19]

This relationship is controversial. It may be that satisfaction occurs because employees have the chance to be more productive (Robbins, 1997: 32). However, it is likely that employers would regard both being satisfied and being productive as desirable employee attributes.

References

- Allan, C., G.J. Bamber and N. Timo. 2002. “Employment Relations in the Australian Fast Food Industry.” Labour Relations in the Global Fast Food Industry. T. Royle, ed. London: Routledge.

- Cantalupo, J. 2003. “Supersize Insult to Industry Workers: Dictionary Needs to Improve Degrading “McJob” Definition.” Nation’s Restaurant News, 37 (44), 18–45.

- Caplow, T. 1964. The Sociology of Work. London: McGaw Hill.

- Daniels, C. 2004. “50 Best Companies for Minorities.” Fortune, 149 (13), 136–142.

- DiNome, T. 2001. “Eat Your McMuffin.” Restaurant Business, 100 (15), 24–30.

- Erikson, E. 1963. Childhood and Society. New York: Norton.

- Feder, B.J. 1995. “Dead-End Jobs: Not for These Three.” New York Times, July 4, 45–50.

- Fields, D.L. 2002. Taking the Measure of Work: A Guide to Validate Scales for Organisational Research and Diagnosis. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Garson, B. 1988. The Electronic Sweatshop: How Computers are Transforming the Office of the Future into the Factory of the Past. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Goldeen, J. 2004. “Teens Struggle to Land First Job in Tight Labour Market.” Night Rider Tribune Business News, June 6, 1.

- House, R.J., H.J. Shapiro and A. Wahba. 1974. “Expectancy Theory as a Predictor of Work Behavior and Attitudes: A Re-evaluation of Empirical Evidence.” Decision Sciences, January.

- Kalleberg, A. 2000. “Nonstandard Employment Relations: Part-time, Temporary and Contract Work.” Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 341–365.

- Kincheloe, J.L. 2002. The Sign of the Burger. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Kroc, R. 1987. Grinding it Out. Chicago: St. Martin’s Paperbacks.

- Leidner, R. 1993. Fast Food Fast Talk: Service Work and the Routinisation of Everyday Work. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Locke, E.A., and G.P. Latham. 1990. A Theory of Goal Setting and Task Performance. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

- Love, J.F. 1995. McDonald’s: Behind the Arches. London: Bantam Press.

- Lucas, R., and S. Curtis. 2001. “A Coincidence of Needs? Employers and Full-Time Students.” Employee Relations, 23 (4), 38–54.

- Luthans, F., and R. Kreitner. 1984. Organizational Behavior Modification and Beyond: An Operant and Social Learning Approach. Glenview: Scott-Foresman.

- Lyons, K. 1999. “Fast Food Franchising and the Future.” Franchising Magazine, 12 (5), 2–7.

- McClelland, D.C. 1975. Power: The Inner Experience. New York: Irvington.

- McDonald’s. 1998. Operations and Training Manual. Sydney: McDonald’s Corporation.

- McDonald’s. 2001. MacPac. Sydney: McDonald’s Corporation.

- Morse, P. 1997. “In Defence of a Diverse Workforce: Good Mix Helps Small Firms Succeed.” The Denver Business Journal, 49 (5), 19.

- Mortimer, J., E. Pemental, S. Ryu, K. Nash and C. Lee. 1996. “Part-time Work and Occupational Value Formation in Adolescence.” Social Forces, 74 (4), 1405–1419.

- Mowday, R.T. 1991. “Equity Theory Predictions of Behavior in Organizations.” Motivation and Work Behavior. 5th ed. R. Steers and L.W. Porter, ed. New York: McGaw-Hill, 111–131.

- Robbins, S. 1997. Essentials of Organizational Behavior. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

- Robinson, L. 1999. The Effects of Part-Time Work on School Students. Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research.

- Ritzer, G. 1993. The McDonaldization of Society. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Royle, T. 2000. Working for McDonald’s in Europe: The Unequal Struggle? London: Routledge.

- Schlosser, E. 2002. Fast Food Nation. New York: Harper Collins.

- Smith, E., and L. Wilson. 2002. “The New Child Labour: The Part-time Student Workforce in Australia.” Australian Bulletin of Labour, 28 (2), 120–137.

- Solomon, C.M. 1997. “Case Study: McDonald’s Serves Up HR Success in 91 Countries around the World.” Management Development Review, 10, 42–43.

- Tannock, S. 2001. Youth at Work: The Unionised Fast Food and Grocery Workplace. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Vaughan, G., and M.A. Hogg. 2002. Introduction to Social Psychology. Sydney: Prentice-Hall.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Design of the Study

Figure 2

Crew Preference for a Career at McDonald’s, McDonald’s, May 2003 (preference, number)

Figure 3

Combining Survey Items into Factors Prior to Factor Analysis(Items are combined because they are correlated and appear to be indexing the same underlying idea)

Figure 4

Divergence View of Crew Change in Attitude / Orientation to Fast Food Work: Age as the IndependentVariable and Career-Committed Crew Maintaining Satisfaction

Figure 5

Negative View of Crew Work: Length of Service as the Independent Variable and all Crew BecomingLess Satisfied and / or Disadvantaged

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Classification Table for Regression Addressing Who, amongst Crew, Would Like to Work at McDonald’s in FiveYears Time, McDonald’s, May 2003 (observed, predicted)

Observed |

Predicted |

|||

Wanting a career recoded to binary |

Percentage correct |

|||

|

Do not want career (n - predict = 366) |

Do want career (n - predict = 226) |

|

||

"Want a career" recoded to binary |

Do not want career (n-o = 362) |

|

|

362/366 = 99% (approx) |

|

Do want career (n-o = 261) |

|

|

226/261 = 86% (approx) |

Overall Percentage |

|

|

|

94 percent (approx) |

a The cut value is .500; Percentages are calculated by making the smaller number the numerator and the larger number the denominator.

Table 2

Variables Used to Predict Who Wants to Work at McDonald’s in Five Years Time, McDonald’s, May 2003(significance statistics)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

95.0% C.I. for EXP (B) |

|

|

|

B |

S.E. |

Wald |

df |

Sig. |

Exp(B) |

Lower |

Upper |

Step 1(a) |

Timecont |

-.140 |

.142 |

.971 |

1 |

.324 |

.869 |

.658 |

1.148 |

Satis |

.951 |

.215 |

19.573 |

1 |

.000 |

2.587 |

1.698 |

3.942 |

|

Complicate |

-.124 |

.183 |

.457 |

1 |

.499 |

.884 |

.617 |

1.265 |

|

Talkalot |

.957 |

.145 |

16.993 |

1 |

.000 |

1.817 |

1.368 |

2.414 |

|

Unusual |

1.077 |

.180 |

35.893 |

1 |

.000 |

2.937 |

2.064 |

4.177 |

|

Withoutask |

.781 |

.135 |

33.400 |

1 |

.000 |

2.184 |

1.676 |

2.846 |

|

Toldonething |

1.006 |

.178 |

32.109 |

1 |

.000 |

2.736 |

1.931 |

3.875 |

|

Constant |

-15.196 |

1.410 |

116.151 |

1 |

.000 |

.000 |

- |

- |

a Variable(s) entered on step 1: TIMECONT, SATIS, COMLICATE, TALKALOT, UNUSUAL, WITHOUT, TASKSIMP.

Table 3

Correlation between Crew Age and Crew Views about Aspects of Employment Relations, McDonald’s,May 2003 (correlation and significance statistics)

Human Resource Management Variable |

Survey Statements |

Type of Crew |

Correlation Coefficient with age |

Significance |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

For Coefficient with Age |

Between type of Crew |

||||

Embrace of Culture Measure |

Embrace of organizational- culture as measured through factor created from high correlation between quality, service, value and cleanliness |

Crew who want to have a career |

r = 0.05 |

Signif (α = 0.05) |

Between subjects ANOVA analysis signif (α = 0.05) |

Crew who do not want to have a career |

r = -0.02 |

Signif (α = 0.05) |

|||

Embrace of Global Satisfaction Measure |

Satisfaction measure created from factor analysis Items used to create the factor are: "Overall I'm satisfied with my current job", and "Overall, I'm satisfied with the management team in my store" |

Crew who want to have a career |

r = 0.6 |

Signif (α = 0.05) |

Between subjects ANOVA analysis signif (α = 0.05) |

Crew who do not want to have a career |

r = -0.7 |

Signif (α = 0.05) |

Table 3a

Frequency Data and Percentages for Survey Items Used to Produce Analysis in Table 3(all n values are less than 812 due to missing data)

Survey Element |

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

McDonald's only sells quality products |

3.6% |

11.8% |

20.6% |

27.3% |

36.7% |

(n = 787) |

(n = 28) |

(n = 93) |

(n = 162) |

(n = 215) |

(n = 289) |

McDonald's stores always have high standards of service |

3.7% |

9.1% |

15.7% |

30.4% |

41.2% |

(n = 784) |

(n = 29) |

(n = 71) |

(n = 123) |

(n = 238) |

(n = 323) |

McDonald's stores are always very clean |

2.4% |

12.1% |

18.9% |

27.1% |

39.5% |

(n = 794) |

(n = 19) |

(n = 96) |

(n = 150) |

(n = 215) |

(n = 314) |

Overall, I am satisfied with my current job |

2.7% |

10.2% |

18.8% |

32.0% |

36.3% |

(n = 787) |

(n = 21) |

(n = 80) |

(n = 148) |

(n = 252) |

(n = 286) |

Overall, I am satisfied with the management team in my store |

2.8% |

10.7% |

18.4% |

28.8% |

39.3% |

(n = 787) |

(n = 22) |

(n = 84) |

(n = 145) |

(n = 227) |

(n = 309) |

Table 4

Correlation between Crew Age and Crew Views about Aspects of Labour Management, McDonald’s,May 2003 (discrepancy score, significance statistics)

Variable |

Type of Crew |

Survey Statements Used to Calculate Discrepancy* |

Correlation between discrepancy and Age |

Signifcance |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

For Coefficient with Age |

Between types of Crew |

||||

Task Sameness |

Those who want a career |

I do exactly the same task through my shift - I would like to do the same task through my shift = discrepancy score variable |

r = 0.1 |

Not signif (α = 0.05) |

Between subjects ANOVA analysis signif (α = 0.05) |

Those who do not want a career |

I do exactly the same task through my shift - I would like to do the same task throughmy shift = discrepancy score variable |

r = 0.2 |

Not signif (α = 0.05) |

||

Task Complexity |

Those who want a career |

The tasks I do at work are complicated - I like doing complicated tasks at work = discrepancy score variable |

r = 0.0 |

Not signif (α = 0.05) |

Between subjects ANOVA analysis signif (α = 0.05) |

Those who do not want a career |

The tasks I do at work are complicated - I like doing complicated tasks at work = discrepancy score variable |

r = 0.4 |

Signif (α = 0.05) |

||

Dealing with Problems |

Those who want a career |

When a minor problem occurs at work I deal with it without taking it to my manager - When a problem occurs at work I would prefer to deal with it without taking it to my manager = discrepancy score variable |

r = 0.1 |

Not signif (α = 0.05) |

Between subjects ANOVA analysis signif (α = 0.05) |

Those who do not want a career |

When a minor problem occurs at work I deal with it without taking it to my manager - When a problem occurs at work I would prefer to deal with it without taking it to my manager = discrepancy score variable |

r = 0.3 |

Not signif (α = 0.05) |

||

Unusual Situations |

Those who want a career |

Whilst on shift I am expected to find ways of dealing with unusual situations - I enjoy the challenge of dealing with unusual situations at work = discrepancy score variable |

r = 0.6 |

Signif (α = 0.05) |

Between subjects ANOVA analysis signif (α = 0.05) |

Those who do not want a career |

Whilst on shift I am expected to find waysof dealing with unusual situations - I enjoythe challenge of dealing with unusual situationsat work = discrepancy score variable |

r = 0.0 |

Not signif (α = 0.05) |

*: Dissatisfaction is inferred from discrepancy.

Table 4a

Frequency Data and Percentages for Survey Items Used to Produce Analysis in Table 4(all n values are less than 812 due to missing data)

Survey Element |

Strongly Disagree |

Disagree |

Neutral |

Agree |

Strongly Agree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

I do exactly the same task through my shifts |

7.0% |

13.7% |

14.6% |

13.9% |

50.8% |

(n = 786) |

(n = 55) |

(n = 108) |

(n = 155) |

(n = 109) |

(n = 399) |

I would like to do the same task during a shift |

16.8% |

27.6% |

17.9% |

33.4% |

4.3% |

(n = 782) |

(n = 131) |

(n = 216) |

(n = 140) |

(n = 261) |

(n = 34) |

The tasks I do at work are complicated |

21.5% |

37.8% |

32.6% |

5.1% |

3.0% |

(n = 800) |

(n = 172) |

(n = 302) |

(n = 261) |

(n = 41) |

(n = 24) |

I like doing complicated tasks at work |

2.3% |

5.6% |

45.3% |

27.0% |

19.8% |

(n = 779) |

(n = 18) |

(n = 44) |

(n = 353) |

(n = 210) |

(n = 154) |

When a minor problem occurs at work, I deal with it without taking it to my manager |

12.7% |

18.2% |

17.3% |

32.7% |

19.1% |

(n = 790) |

(n = 100) |

(n = 144) |

(n = 137) |

(n = 258 |

(n = 151) |

When a problem occurs at work, I would prefer to deal with it without asking my manager |

12.8% |

24.5% |

23.0% |

22.3% |

15.5% |

(n = 773) |

(n = 99) |

(n = 189) |