Résumés

Abstract

This paper examines the relationship between employee involvement programs and workplace dispute resolution using data from the Workplace and Employee Survey (WES) conducted by Statistics Canada. The results provide support for a link between employee involvement and lower grievance rates in unionized workplaces. This link existed for establishments in both the goods and service sectors, but the practices involved differed between industrial sectors. By contrast, in nonunion workplaces, results of the analysis provided support for a link between the adoption of employee involvement programs and formal grievance procedures, but not between employee involvement and lower grievance rates.

Résumé

Cet essai reprend les données de l’Enquête sur le lieu de travail et les employés (ELTE) de Statistique Canada pour vérifier la relation entre l’implication des salariés et le règlement des mésententes sur les lieux de travail. Le règlement des mésententes sur les lieux de travail fournit un ancrage à de nombreuses discussions sur l’implication des salariés. Les partisans de l’implication des salariés prétendent que ces programmes ont des effets bénéfiques sur la diminution des griefs et favorisent une solution plus rapide et plus efficace des règlements des conflits. Il existe plusieurs manières dont l’implication des salariés peut conduire à une diminution des conflits. Un niveau plus élevé de collaboration et de confiance entre les salariés et la direction sous l’égide de programmes d’implication peut contribuer à la réduction des conflits dans le sens d’une diminution des sources de griefs sur les lieux de travail. Un règlement de nature informelle peut aussi contribuer à réduire le nombre de griefs si les programmes d’implication permettent aux salariés de résoudre plus rapidement les problèmes sur une base informelle avant qu’ils se transforment en griefs officiels. Enfin, un effet de légitimation peut apparaître si l’implication des salariés incite ces derniers à accorder plus de légitimité aux décisions sur les lieux de travail et, par conséquent, ces décisions ont moins de valeur de contestation dans le cas d’un recours éventuel à la procédure de règlements des griefs. À l’opposé, les critiques de l’idée d’implication des salariés prétendent que ces programmes contribuent à l’intensification du travail et engendrent de nouvelles sources de conflits sur les lieux de travail. De plus, les programmes d’implication présentent des différences en termes de structure et d’impact et il peut arriver que l’effet de tels programmes sur la solution des conflits dépende de la nature du programme en question et du contexte dans lequel il est introduit.

Cet article analyse les données tirées de l’enquête de Statistique Canada sur des échantillons d’établissements au cours des années 1999 et 2000. Cette recherche est basée sur un échantillon représentatif à l’échelle nationale d’établissements du secteur privé, permettant de vérifier l’impact des programmes d’implication sur le règlement des mésententes sur les lieux de travail à travers un large éventail d’industries et comprenant des lieux de travail syndiqués et également non syndiqués. Étant donné les différences importantes entre les procédures de solutions des conflits au passage d’un secteur syndiqué à un autre non syndiqué, on a effectué une analyse séparée : une pour les établissements non syndiqués, une autre pour ceux syndiqués. Dans le cas de ces derniers, où la procédure formelle de règlement des griefs est universellement répandue, la variable clef dépendante comportant un intérêt certain était le taux de griefs. Dans le cas des établissements non syndiqués, où l’on observe de grandes variations au plan des modes de solution des mésententes, la variable dépendante incluait à la fois une procédure formelle de règlement et un taux de plaintes.

Les données observées dans le secteur syndiqué viennent confirmer la présence d’un effet des programmes d’implication dans le sens d’une réduction du taux de griefs. Des notes plus élevées sur un indice cumulatif mesurant la présence de programmes d’implication étaient accompagnées d’un taux plus faible de griefs. Également, une mesure d’un niveau plus élevé d’implication des employés dans la prise de décisions s’accompagnait d’un taux réduit de griefs. Des différences apparaissaient là où les données étaient ventilées par secteur industriel. Alors que, dans le secteur des biens, des équipes autogérées constituaient le type unique d’implication des salariés associées à de faibles taux de griefs, on constatait, dans le secteur des services, la présence de groupes de solution de problèmes comme l’unique type d’implication associé à un plus faible taux de griefs. La plupart des études existantes, s’intéressant à l’implication des salariés, renvoient à des travaux de recherche effectués dans le secteur des biens et elles font ressortir l’importance des équipes autogérées comme étant le seul type de programme comportant l’impact le plus prononcé. Au contraire, les conclusions de la présente étude sont à l’effet que, dans le secteur des services, les groupes de solution de problèmes ont un impact plus élevé.

Les résultats de la recherche dans le cas des établissements non syndiqués présentent une mosaïque variée au plan des effets des programmes d’implication. On constate une association assez marquée entre des programmes d’implication et la présence de procédures formelles de règlement de griefs dans les établissements non syndiqués. Des notes plus élevées sur l’indice d’implication étaient associées à des probabilités plus élevées de recourir à une procédure formelle de règlement. Parmi les types particuliers de programmes, ceux de rotation de postes et d’équipes autogérées s’accompagnaient de la présence de procédures formelles de règlement. Cependant, en opposition aux conclusions dans le cas des établissements syndiqués, on n’observait pas de liens significatifs entre les programmes d’implication et le taux de griefs dans les établissements non syndiqués. Une explication de ce phénomène est la présence possible d’effets compensateurs à l’oeuvre dans ces derniers établissements qui influencent le taux de griefs. Si l’effet de réduction des conflits observé dans les établissements syndiqués opère également dans ceux qui ne sont pas syndiqués, cela va alors contribuer à une réduction du taux de griefs. Cependant, il existe aussi un effet opposé qui origine dans les différences non constatées au plan de la qualité des procédures dans le secteur non syndiqué. Alors que les procédures de règlement sont relativement standard dans leur composition, qu’elles représentent de façon bien caractérisée des preneurs de décisions neutres et qu’elles reflètent également une représentation indépendante des employés dans le secteur syndiqué, on observe, dans les lieux de travail non syndiqués, que la composition des procédures de règlement et la garantie qu’elles offrent à l’endroit d’un traitement équitable varient énormément. Les salariés peuvent hésiter à recourir à des procédures de règlement dans le secteur non syndiqué à cause d’une absence de protection à l’endroit d’un traitement équitable et à cause d’éventuelles représailles qui peuvent être exercées contre eux. Si les établissements non syndiqués, où l’on retrouve des programmes d’implication, ont des procédures de règlement comportant des garanties plus élevées d’un traitement équitable et une protection contre des représailles découlant du recours à de telles procédures, cela peut accroître la probabilité que les salariés se servent de la procédure lorsqu’un problème se présente sur les lieux de travail. Cela peut alors faire en sorte que des programmes d’implication puissent produire un effet positif, compensant l’effet négatif de réduction de conflits qu’on a décrit plus haut.

Dans l’ensemble, les conclusions de l’étude fournissent un support aux arguments de ceux qui se font les défenseurs des programmes d’implication. Ces derniers s’accompagnent d’un taux plus faible de griefs dans les établissements syndiqués et d’une diffusion plus grande des procédures formelles de règlement dans les établissements non syndiqués. Cependant, ces conclusions permettent de constater quelques variations au plan de l’effet des programmes d’implication, à la fois entre les secteurs des biens et ceux des services, entre les lieux de travail syndiqués et non syndiqués.

Resumen

Este documento examina la relación entre los programas de implicación laboral y la resolución de conflictos en el centro de trabajo y se basa, para ello, en los datos de la Encuesta de centros de trabajo y empleados (Worplace and Employee Survey) llevada a cabo por Statistic Canada. Los resultados validan la existencia de un vínculo entre implicación laboral y nivel bajo de quejas en los medios laborales sindicalizados. Este vinculo existe en los establecimientos de los sectores de bienes y de servicios pero las practicas comprendidas difieren entre sectores industriales. En contraste, en los medios laborales no sindicalizados, los resultados del analisis validan la existencia de un vinculo entre la adopción de programas de implicación laboral y el tramite formal de las quejas más no así entre implicación laboral y nivel bajo de quejas.

Corps de l’article

This study uses data from the Workplace and Employee Survey (WES) to investigate the relationship between employee involvement programs and workplace dispute resolution. Debates over the impact of employee involvement programs have included contrasting claims as to whether these programs either lead to better relations between management and employees in the workplace and improved organizational performance, or alternatively represent a new form of work intensification that produces greater conflict in the workplace and employee dissatisfaction. Workplace dispute resolution provides a fulcrum upon which many of the questions posed by these debates turn. One of the areas where advocates of employee involvement programs have claimed their strongest effects is in reducing grievance rates and encouraging faster, more informal resolution of grievances to the benefit of both organizations and employees (Kochan, Katz and McKersie 1986; Cutcher-Gershenfeld 1991). In contrast, critics claim that employee involvement programs create new conflicts in the workplace and that use of grievance procedures to protect employee interests is undermined by labour-management cooperation (Parker and Slaughter 1988; Godard and Delaney 2000). This study investigates these contrasting claims using data from the Workplace and Employee Survey (WES) conducted by Statistics Canada. The WES provides a useful dataset to examine these questions by providing workplace level data on grievance procedures and activity from a large number of organizations with varying degrees and types of employee involvement practices in the workplace.

Theory and Literature Review

In research investigating the transformation of industrial relations at the workplace level, high grievance rates were seen as one of the key characteristics of traditional adversarial patterns of relations in the workplace (Kochan, Katz and McKersie 1986). Conversely, lower grievance rates and faster, more informal resolution of disputes were identified as part of transformed systems or patterns of industrial relations that were associated with improved organizational performance (Katz, Kochan and Weber 1985; Ichniowski 1986; Cutcher-Gershenfeld 1991). If lower grievance rates are part of such transformed patterns of industrial relations, then we would expect grievance rates to vary in conjunction with other practices and behaviours that form part of these workplace industrial relations systems (Katz, Kochan and Weber 1985; Kochan, Katz, and McKersie 1986).

There are three different ways in which high involvement work systems may lead to lower rates of usage of dispute resolution procedures. First, greater trust and cooperation between employees and management under high involvement work systems may lead to a reduction in the overall level of conflict in the workplace (Kochan, Katz, and McKersie 1986). This conflict reduction effect should reduce the number of underlying disputes in the workplace and thereby also reduce the overall rate of usage of dispute resolution procedures. Second, there may be an impact of high involvement work systems on how disputes are resolved in the workplace. To the degree that workers are able to resolve more problems and disputes informally through these other structures for participation in the workplace, we would expect usage of dispute resolution procedures to be reduced (Cutcher-Gershenfeld 1991). This informal resolution effect would predict a reduction in rates of usage of dispute resolution procedures even if the level of underlying conflict is not affected. Finally, the involvement of employees in decision-making in team-based production systems and greater labour-management trust resulting from these systems may also produce an effect in which decisions are seen as having greater legitimacy to employees. This legitimization effect would also lead to a prediction of a reduction in grievance rates under high performance work systems, apart from any effect on the underlying level of conflict in the workplace (Colvin 2003b).

Why should these effects of employee involvement on workplace dispute resolution matter for organizations? One direct effect on organizations comes from what Katz, Kochan, and Weber (1985) described as the displacement effect of grievance handling. This is the simple insight that the greater the time devoted by managers and employees to grievance handling, the less will be the time devoted to more productive activities in the workplace. Two more indirect effects are suggested by exit-voice theory and organization justice theory. As applied to the employment context, exit-voice theory suggests that when confronted with problems in the workplace, if employees are able to use ‘voice’ mechanisms such as grievance procedures to resolve problems, they are less likely to try to use the ‘exit’ mechanism of quitting to resolve the problem (Freeman and Medoff 1984). More effective voice mechanisms can benefit organizational performance by reducing costly turnover, which is likely to be especially important under high involvement work systems where the reliance on employee commitment and extensive training makes the organization more vulnerable to high turnover rates (Shaw et al. 1998; Batt, Colvin and Keefe 2002). Organizational justice theory suggests that effective voice mechanisms can also benefit organizations by helping induce high levels of job satisfaction and organizational commitment among the workforce (Sheppard, Lewicki and Minton 1992; Folger and Cropanzano 1998). Experimental research results indicate that access to a grievance system enhances the organization commitment of employees (Olson-Buchanan 1996).

Obtaining these positive organizational effects depends on the degree to which employee involvement actually produces the predicted improvements in workplace dispute resolution. Some have argued that, in fact, employee involvement programs may have the contrary effect of leading to greater conflict in the workplace and of undermining the effectiveness of traditional employee interest representation through structures such as grievance procedures (Godard and Delaney 2000). Among the criticisms of employee involvement programs is that they involve an intensification of work in which teams effectively serve as mechanisms for workers to become their own Tayloristic managers, developing new ways to maximize the pace of work (Parker and Slaughter 1988). Another line of criticism of work teams suggests that there is a disciplining effect of teams in which teams establish and monitor norms of behaviour and work performance (Barker 1993). If teams do serve this function of disciplining deviations from behavioural norms by team members, then it may be that implementation of self-managed work teams will lead to an increase in grievances resulting from intra-team conflicts.

Another possibility is that the effect of employee involvement may depend on the nature of the involvement practices used. From this perspective, it may be the case that some employee involvement programs involve empowerment of workers and reduced workplace conflict, whereas other programs are techniques for work intensification that produce heightened conflict. For example, Appelbaum and Batt (1994) argue that involvement programs in North American can be seen as following two contrasting models. Under the joint team production model, employee involvement involves worker empowerment and the use of self-managed teams, and is typically developed and implemented in collaboration between unions and management. By contrast, under the alternative lean production model, employee involvement occurs in a much more management-directed fashion, characteristically using off-line participation groups directed more narrowly at improving quality and productivity. Following this analysis, we might expect the joint team production model with its self-managed teams to lead to a reduction in workplace conflict, whereas the work intensification of lean production would lead to an increase in conflict. The key point here is that employee involvement may not be a unidirectional construct, but rather the effect of involvement can depend on the nature of the program. Therefore, it is important to investigate a number of different features of employee involvement programs in order to understand their effects on workplace conflict.

A complicating factor in understanding the effect of employee involvement on workplace conflict is the major differences that exist between dispute resolution in union and nonunion workplaces. In Canada, as in the United States, unionized workplaces virtually universally feature multi-step grievance procedures, generally culminating in binding arbitration. Although there have been some innovations, such as expedited arbitration and grievance mediation, what is striking about grievance procedures in unionized workplaces is the similarity of procedures across workplaces and their stability over time (Eaton and Keefe 1999). Given this relative similarity among union grievance procedures, in research on conflict in unionized workplaces it is possible to use common measures, such as the grievance rate, as a standard basis for comparison of conflict resolution across different workplaces (e.g., Katz, Kochan and Weber 1985; Ichniowski 1986). By contrast, when we turn to the nonunionized workplace, we have to deal with the added layer of complexity resulting from variation in the presence and structure of grievance procedures. In nonunion workplaces, introduction of grievance procedures is at the discretion of management, who may choose to have no procedure, only a simple informal procedure, or to develop a more elaborate formal procedure. Research in the United States has found wide variation in both the adoption and structure of nonunion grievance procedures (Feuille and Chachere 1995; Colvin 2003a) and there is no obvious reason to expect an absence of similar variation in Canada. This raises the possibility that in the nonunion workplace, employee involvement will be related to both the presence and the usage of grievance procedures. In research on the telecommunications industry in the United States, Colvin (2003a) found that employee involvement programs in the form of self-managed teams were positively related to the presence of nonunion grievance procedures, in particular procedures involving peer review panels. Subsequent research indicated that among nonunion workplaces with procedures, those that also had self-managed teams had lower grievance rates (Colvin 2003b). In that research, employee involvement programs had an additional effect in nonunion workplaces on the adoption and structure of grievance procedures, but holding the type of procedure constant, the effect on usage was similar to that for unionized workplaces. Although this study was based on a single industry in the United States, it is plausible that the same relationships may also be present for nonunion workplaces in Canada.

An additional factor to consider is that much of the research on employee involvement has focused on the manufacturing sector. Much less is known about the nature and impact of employee involvement in the service sector. Although there are not strong a priori reasons for expecting specific differences based on industrial sector, it is certainly possible that different types of employee involvement programs may be emphasized with different effects on the workplace in the service sector compared to the manufacturing sector.

In summary, the existing literature and theory suggest contrasting hypotheses that will be tested in this study. If advocates of employee involvement are correct, we would expect to find employee involvement programs to be associated with lower levels of workplace conflict. By contrast, if critics of employee involvement are correct, we would expect to find employee involvement programs to be associated with higher levels of workplace conflict. Alternatively, if those emphasizing variation in the nature of employee involvement are correct, then we would expect the direction of the relationship with workplace conflict to depend on the type of employment involvement program, with joint team based programs being associated with reduced conflict and more individualized lean production approaches being associated with higher conflict levels. Finally, given the variation in the incidence and structure of grievance procedures in nonunion workplaces, if the predictions of advocates of employee involvement are correct, we would expect to find in nonunion workplaces a positive association between employee involvement programs and the presence of formal grievance procedures as well as lower conflict levels, holding the type of procedure constant.

Data and Methods

This study analyzes data from the 1999 and 2000 samples of the Workplace and Employee Survey (WES) conducted by Statistics Canada. The WES is a nationally representative survey of establishments in the Canadian private sector that parallels similar government sponsored surveys conducted in the United Kingdom and Australia, albeit with some differences in methodology and focus (Godard 2001). A key strength of the WES is its breadth of coverage, including all industries except farming, fishing, trapping, and the public sector. An additional strength of the WES is its very high response rate, with over 95% of establishments responding in both 1999 and 2000 (96.5% and 95.8% respectively). Although the WES is designed to provide a broad set of information about the workplace, rather than for the testing of specific hypotheses (Godard 2001), it contains a number of questions on employee involvement practices and workplace grievance procedures relevant to the issues being examined in this study.

The sample for analytical purposes was restricted to establishments responding to the survey in both 1999 and 2000. Some questions in the WES are only asked every second year, in this case in the 1999 version of the survey, whereas others are asked each year. As described below, some variables are constructed based on the two-year responses, whereas others, generally structural or policy characteristics of the workplaces, are based on the 1999 responses. For analytical purposes, I also restricted the sample to establishments with at least 20 employees. The reason for doing this is to reduce the influence of high variability in annual grievance rates in small establishments arising from the small denominator in the equation for the grievance rate. For example, one additional grievance in a year in a workplace of only five employees would produce a seemingly very large 20 percentage point jump in the grievance rate.

The primary respondent for the employer portion of the WES is the human resource manager for large establishments and the owner/manager for small establishments. The survey was administered by a computer-assisted telephone interview. Although the WES is a particularly carefully designed and administered survey, it is worth noting that these are self-reported measures collected from individual managers with resulting potential biases.

Dependent Variables. The primary dependent variable of interest in this study is the annual grievance rate in the establishment. For purposes of analysis, the grievance rate is measured as the natural log of the annual number of grievances per 100 employees for both union and nonunion establishments. I constructed a two-year average grievance rate using the reported grievances from 1999 and 2000. The advantage of using a two-year time period to create an average annual grievance rate is that it reduces the influence of short-term fluctuations in grievance rates. The logged form is used to normalize the distribution of the dependent variable for analysis. The grievance rate here measures only the total number of grievances filed, not the level or speed of settlement. It may be that there are additional or even stronger relationships between employee involvement and the level or speed of settlement (see Cutcher-Gershenfeld 1991); however, the WES establishment level survey does not provide this data. A second dependent variable of interest for nonunion establishments is the presence of a formal grievance procedure. As noted earlier, whereas formal grievance procedures are virtually universal in unionized workplaces, many nonunion workplaces lack formal grievance procedures. As a consequence, a preliminary question to be examined for nonunion workplaces is whether or not they have a formal grievance procedure, which is measured by a simple dichotomous variable representing whether (1 = yes) or not (0 = no) the establishment has a formal grievance procedure. This question was only asked on the 1999 version of the WES, not on the 2000 survey, so the variable captures the responses in 1999.

Independent Variables. Three variables measure the presence of different types of employee involvement programs in the workplace, each captured by a single dichotomous variable indicating the presence (1 = yes) or absence (0 = no) of the program. These questions were only asked in 1999 and the variables are constructed from these responses. The survey questions included an extended description of each type of program for respondents. The first measures whether or not the workplace has self-managed teams (Description in survey: “Self-directed work groups. Semi-autonomous work groups or mini-enterprise work groups that have a high level of responsibility for a wide range of decisions/issues.”). The second measures whether or not the workplace has problem solving groups (Description in survey: “Problem-solving teams. Responsibilities of teams are limited to specific areas such as quality or work flow.”). The third measures whether or not the workplace has a job rotation program (Description in survey: “Flexible job design. Includes job rotation, job enrichment/redesign (broadened job definitions), job enrichment (increased skills, variety or autonomy of work).”). Although this last practice does not represent direct employee involvement, it is a practice that has been associated in past research with the general set of high involvement or high performance work practices. It is included here for consistency with past research in this area (e.g., Osterman 1994, 2000). Next, a simple high involvement work organization (HIWO) additive index sums the responses to these three questions to capture the overall incidence of employee involvement practices, following a similar approach by Osterman (1994, 2000).

Whereas the first four independent variables capture the simple presence or absence of programs, they do not indicate the intensity with which employee involvement is used in the workplace. Two additional variables provided a measure of the degree to which employees are involved in decision-making in the workplace. The first of these variables captures individual employee involvement through a four-item scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.790) measuring the degree to which individual employees make decisions with respect to: daily planning of individual work; weekly planning of individual work; follow-up results; quality control; purchase of necessary supplies; and maintenance of machinery and equipment. The second of these variables captures workgroup involvement through a four-item scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.795) measuring the degree to which work groups make decisions with respect to: daily planning of individual work; weekly planning of individual work; follow-up results; quality control; purchase of necessary supplies; and maintenance of machinery and equipment.

Three variables capture human resource (HR) practices supportive of employee involvement. Team training measures whether or not (1 = yes, 0 = no), the establishment provided its employees in 1999 or 2000 with classroom or on-the-job training in either “group decision-making or problem-solving” or “team-building, leadership, communication”. Gainsharing measures whether or not (1 = yes, 0 = no) the establishment’s compensation system in 1999 had a gainsharing program, which rewards employees based on “group output or performance”. Profitsharing measures whether or not (1 = yes, 0 = no) the establishment’s compensation system in 1999 had a profit sharing plan.

Additional independent variables were included to account for workplace characteristics likely to affect grievance rates. Workforce size was measured in hundreds of people employed at the location, calculated as a two-year average for 1999 and 2000. Workforce stability was measured by the proportion full-time and permanent of the workforce (e.g., if 75% of the workforce is full-time and permanent, the proportion full-time and permanent is 0.75). A dichotomous variable (1 = yes, 0 = no) captured whether there was one or more specialized human resource (HR) personnel in the workplace, measured in 1999. Average pay of employees was measured in thousands of dollars, constructed as a two-year average for 1999 and 2000. A single dichotomous variable captured whether the establishment was in the service sector or in the goods/manufacturing sector (1 = service sector, 0 = goods sector).

Two variables were included to control for grievance procedure characteristics that might affect grievance rates: whether the procedure included a labour-management committee (1 = yes, 0 = no); and whether the procedure included an outside arbitrator (1 = yes, 0 = no). Although the WES uses the common term “labour-management committee” in the question for both unionized and nonunion establishments, it is worth noting that this term may capture somewhat different types of procedures in these two contexts. In the unionized context, there may simply be a labour-management committee that jointly addresses grievance issues. By contrast, in the nonunion context, this question may be capturing the presence of peer review procedures, where both managers and employees who are peers of the grievant sit on a panel that decides grievances. Peer review procedures are used by a number of companies in the United States (Colvin 2003a, 2003b), but little is known about their presence or use in Canada. Finally, two variables were included to capture episodes of industrial conflict that often lead to temporary upsurges in grievance rates in unionized workplaces: whether the establishment had a strike or lockout in 1999 or 2000 (1 = yes, 0 = no); and whether the establishment had some type of other work action, including work-to-rule, work slowdowns and other labour actions, in 1999 or 2000 (1 = yes, 0 = no).

Results

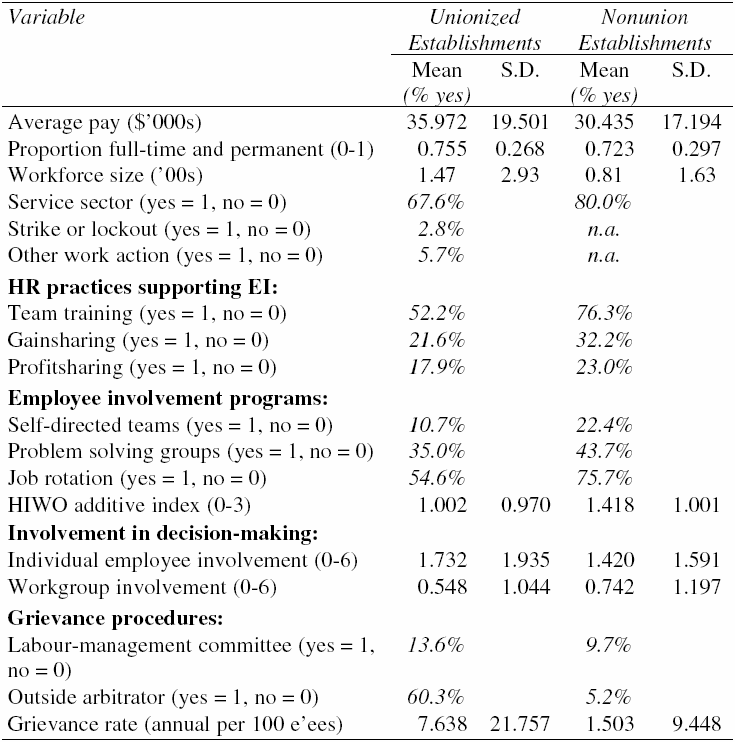

Descriptive statistics for the variables are reported in Table 1. Means and standard deviations are reported separately for union and nonunion establishments. As expected, average annual grievance rates are much higher in unionized establishments, 7.64 per hundred employees, than in nonunion establishments, 1.50 per hundred establishments. Overall, employee involvement programs are more common in nonunion than in unionized establishments. However, it is interesting to note that individual employee involvement in decision-making is higher in unionized establishments than in nonunion establishments.

Estimation equations for the dependent variables are reported in Tables 2-4. The first dependent variable, the logged grievance rate, has a distribution that is approximately normal (after the log transformation), but is truncated below at zero since grievance rates cannot be less than zero. As a result, tobit regressions are used for estimating this variable. The second dependent variable estimated, the presence of a formal grievance procedure in nonunion establishments, is dichotomous (1-0). Logit regressions are used for estimating this variable. All regressions are weighted based on the sampling design of the WES survey. Estimations for the grievance rate are conducted separately for nonunion and unionized establishments, given that the institutional structure and role of the grievance procedure in unionized workplaces may produce different dynamics and predictors of grievance rates than is the case in nonunion workplaces. In addition, separate regressions are estimated for unionized establishments in the goods and service sectors to see if relationships differed by industrial sector.

Table 1

Means and S.D. for Grievance Rate Estimation Sub-Samples of Union and Nonunion Establishments with Formal Grievance Procedures

Note: For dichotomous (yes = 1, no = 0) variables, the percentage of yes responses is reported under the “mean” column.

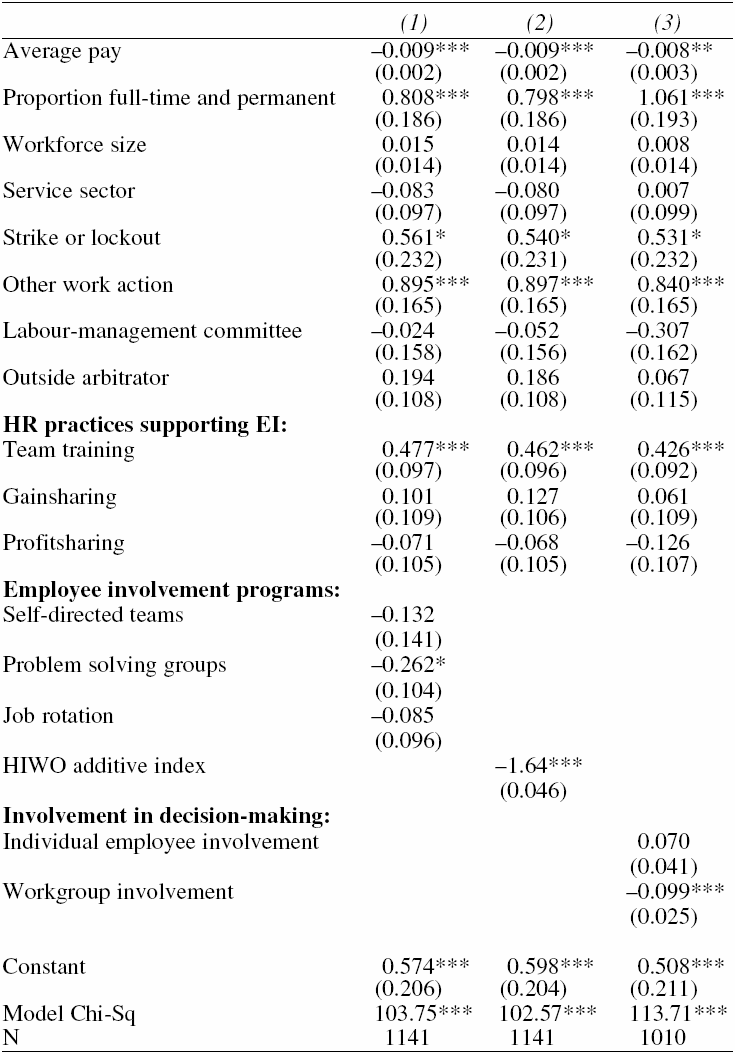

Results for three prediction equations for grievance rates for unionized establishments are reported in Table 2. In the first equation, employee involvement is represented by the three variables representing different types of employee involvement programs, i.e. self-directed teams, problem solving groups, and job rotation. Among the three types of EI program, problem solving groups have a statistically significant (p < .05) negative association with grievance rates. The coefficients for both self-directed teams and job rotation are negative, but neither is statistically significant. In the second equation, employee involvement is represented by the HIWO additive index, which also has a statistically significant (p < .001) negative association with grievance rates. The results for the first two estimation equations provide support for the conflict reducing effect of employee involvement. By contrast, the picture is a bit more complicated when we look at employee involvement as captured by the individual employee and workgroup involvement decision-making indexes. Workgroup involvement in decision-making has a statistically significant (p < .001) negative association with grievance rates, in accord with the prediction of a conflict reducing effect of employee involvement. However, individual employee involvement in decision-making was not significantly associated with grievance rates.

Table 2

Predictors of Grievance Rates: Unionized Establishments Tobit estimates for Natural Log of Annual Grievances per 100 employees

There are a few interesting results for other variables in the equations in Table 2. As expected, there are statistically significant positive associations in all three equations between grievance rates and the occurrence of strikes or lockouts (p < .05) and other work actions (p < .001). These results confirm traditional industrial relations wisdom that unions often use the filing of increased numbers of grievances as a technique to put pressure on management in conjunction with other types of labour action such as work slowdowns, work-to-rule, and strikes. More surprisingly, amongst the HR practices thought of as supportive of employee involvement, only team training has a statistically significant (p < .001) association with grievance rates, but in a positive direction rather than the negative direction predicted.

As noted earlier, most of the existing research on employee involvement and on grievance procedures has focused on the manufacturing or goods sector. To investigate whether there are differences in the relationships involved based on industrial sector, separate equations are estimated for the goods and service sectors in Table 3. The results suggest that differences do exist based on industrial sector. The first and third columns in Table 3 report estimation equations for unionized establishments, in the goods and service sectors respectively, with employee involvement represented by the three variables capturing the presence of individual types of programs. Whereas in equation one for the goods sector, self-directed teams are the only type of program with a statistically significant (p < .001) negative association with grievance rates, in equation three for the service sector, problem solving groups are the only type of program with a statistically significant (p < .001) negative association with grievance rates. There is a similar contrast in equations two and four which report estimation equations for unionized establishments in the goods and service sectors, respectively, with employee involvement captured by the two employee involvement in decision-making indexes. In the goods sector, in equation two, individual employee involvement in decision-making has a statistically significant (p < .01) positive association with grievance rates, whereas workgroup involvement is not significant. By contrast, in the service sector, in equation four, workgroup involvement in decision-making has a statistically significant (p < .001) negative association with grievance rates, whereas individual employee involvement is not significant. Overall, these results indicate that employee involvement programs are associated with lower grievance rates in unionized establishments, but that the type of involvement program that has this effect differs between goods and service sector establishments.

Table 3

Predictors of Grievance Rates for Goods and Service Sectors, Union Establishments Tobit estimates for Natural Log of Annual Grievances per 100 employees

Next we turn to the estimation equations for nonunion establishments, reported in Table 4. For nonunion establishments, there are two dependent variables of interest: first, whether the establishment has a formal grievance procedure; and second, for those nonunion establishments with a procedure, the grievance rate. Employee involvement is predicted to be associated with the presence of formal grievance procedures, but also with lower grievance rates for those establishments with procedures. The first two columns in Table 4 report logit regression estimates for the predictors of the presence of a formal grievance procedure in nonunion establishments. Supporting the predicted relationship, in the first equation there is a statistically significant positive association between the presence of formal grievance procedures and both self-directed teams (p < .001) and job rotation (p < .001). Having self-directed teams increases the odds of also having formal grievance procedures by 101% and having job rotation increases the odds of having procedures by 124%. Similarly, there is a statistically significant positive association in the second equation between the presence of formal grievance procedures and the HIWO additive index (p < .001). Among the supportive HR practices, formal grievance procedures have statistically significant positive associations with both gainsharing (p < .001) and profitsharing (p < .01). Gainsharing increases the odds of having a formal grievance procedure by 137% and profitsharing increases the odds by 50%. These results provide good support for the prediction that formal grievance procedures in nonunion establishments will be more likely where the establishments also have employee involvement programs and related supporting HR practices.

Results for two estimation equations for grievance rates for nonunion establishments with formal procedures are presented in the last two columns of Table 4. The results here did not show evidence of a relationship between employee involvement programs and the usage of nonunion grievance procedures. In the third equation in Table 4, none of the three types of employee involvement program examined had statistically significant associations with grievance rates. Neither of the variables measuring employee involvement in decision-making, tested in the fourth equation in Table 4, has a statistically significant association with grievance rates for nonunion establishments. Similarly, none of the supporting HR practices have statistically significant associations with grievance rates in either the third or fourth equations in Table 4. Overall, whereas there is strong evidence for a link between employee involvement and the presence of formal grievance procedures in nonunion establishments, there is a lack of evidence for an association between employee involvement and usage of these procedures for nonunion establishments.

Table 4

Nonunion Establishments: Predictors of Procedure Presence and Grievance Rates

Notes: Models (1) and (2) are logit regressions, models (3) and (4) are tobit regressions; for models (1) and (2), odds ratios are in square parentheses; standard errors are in round parentheses; * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

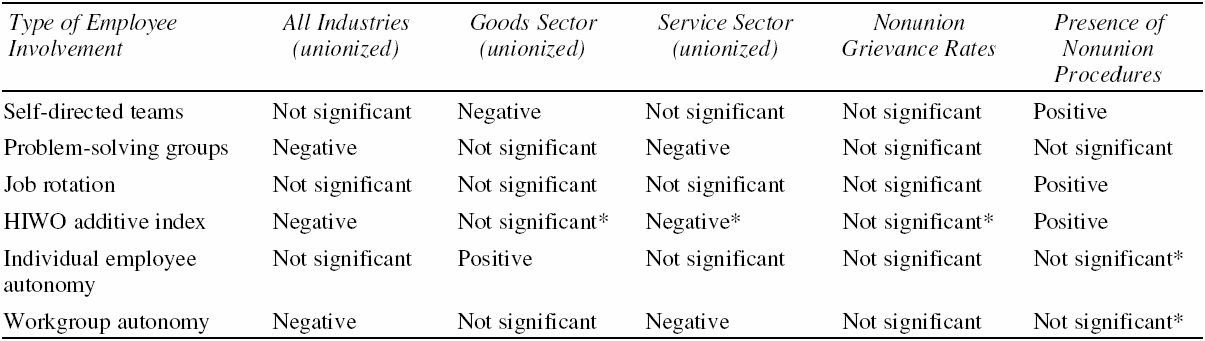

The results for the different measures of employee involvement are summarized in Table 5. Looking across the different results, there is reasonably good support in unionized workplaces for a negative relationship between grievance rates and employee involvement in the form of self-directed work teams, problem solving groups, an additive high involvement index and greater workgroup autonomy. These relationships are not present for grievance rates in nonunion workplaces, but greater employee involvement is associated with a greater likelihood of formal nonunion grievance procedures existing in the workplace. Lastly, similar relationships were not found for greater individual autonomy in workplace decision-making, suggesting that group level involvement is a key factor in the effects found.

Discussion and Conclusions

This study set out to examine the relationship between employee involvement and workplace dispute resolution. Research supporting high involvement work systems has suggested that greater employee involvement should be associated with reduced workplace conflict and lower grievance rates. By contrast, critics of employee involvement have argued that these programs often involve the intensification of work, rather than empowerment of employees and reduction of conflict. In general, the results of this study provide more support for the former view than the latter; however, they also suggest that the dynamics involved in the relationship between employee involvement and workplace dispute resolution are more complex than just a simple, generally applicable effect.

The results found in this study for unionized establishments generally support a link between employee involvement programs and lower grievance rates. Higher involvement practices, as represented by the high involvement work practice index, use of problem solving groups, and greater workgroup involvement in decision-making, were all found to be associated with lower grievance rates. These relationships support the predictions of advocates of employee involvement, that greater involvement will be associated with reduced workplace conflict.

When we break down the results by industrial sector, additional complexity in the relationship between employee involvement and workplace dispute resolution becomes evident. The type of employee involvement program that is most important varies by industrial sector. Whereas in the goods sector, where most past research has focused, self-directed teams had the larger effect, and in the service sector, problem solving groups had the greater effect. Research in the manufacturing setting has particularly emphasized the significance of self-directed teams as an employee involvement mechanism transforming the organization of work. However, the results here suggest that in the service sector, problem solving groups may be having a bigger impact in the workplace. Similarly, there are differences in the effect of different types of employee involvement in decision-making between sectors. Individual involvement in decision-making had an effect in the goods sector in increasing grievance rates, perhaps representing the situation of individualized workplaces in manufacturing. By contrast, workgroup rather than individual involvement in decision-making was important in the service sector, but in the opposite direction of lower grievance rates, which accords with the predictions of advocates of employee involvement.

Table 5

Summary of Relationships between Employee Involvement and Grievance Rates

Note: Predicted direction of relationship with employee involvement is negative for grievance rates, but positive for presence of nonunion procedures. Results marked * are from additional regression results not reported in tables 2-4.

Further layers of complexity are added to the picture when we turn from the more familiar setting of unionized grievance procedures to examine the findings for nonunion establishments. Before looking at grievance rates, an initial question to be examined for nonunion establishments was whether there was an association between the presence of employee involvement programs and the presence of formal grievance procedures. Whereas formal grievance procedures are virtually universal in unionized workplaces, many nonunion workplaces lack any formal procedures for employees to make complaints or grievances, or simply rely on informal or ad hoc handling of complaints by individual managers. If the hypothesized link between employee involvement and more effective workplace dispute resolution is true, then we might expect to find establishments that adopted employee involvement programs to have also adopted formal procedures to handle employee complaints and grievances. The results provided strong support for this proposed link, with nonunion workplaces having self-directed teams, job rotation, and higher scores on the high involvement additive index also being more likely to have adopted formal grievance procedures.

By contrast, when we turn to the usage of nonunion grievance procedures, there is a lack of evidence for a link with the presence of employee involvement programs. One explanation for the absence of findings for nonunion grievance rates may be that there are two opposing effects at work. Employee involvement programs could be exerting a negative effect on grievance rates for the reasons described for union procedures. However, there may be an opposing effect due to variations in the accessibility of nonunion procedures. Past research on nonunion grievance procedures has found that employees are more likely to use procedures that have stronger due process protections, such as procedures with more independent decision-makers (Colvin 2003b). Conversely, research has suggested that employees are likely to be discouraged from using procedures for fear of subsequent retaliation by supervisors, which appears often to be a well-founded fear (Boroff and Lewin, 1996; Lewin and Peterson, 1999; Lewin, 1999). If establishments with employee involvement programs also tend to have grievance procedures with stronger due process features and less retaliation for using them, then we would expect higher usage rates for these procedures. These unobserved characteristics of grievance procedures in high involvement workplaces could be producing an increase in grievance rates that offsets the decrease from reduced workplace conflict with employee involvement. Although the ability to address this possibility in the present study is limited by the data in the WES survey, future research could address this possibility by examining in greater detail the nature and structure of the nonunion grievance procedures and the dynamics of their usage by employees.

Overall, a limitation of this study is the restrictions in the set of questions posed in the WES survey. Although the WES does provide some useful information on grievance procedures and rates, as Godard (2001) has noted, it lacks information in certain areas, such as on the texture and processes of workplace relations. This may be a limitation inherent in large scale, publicly conducted national surveys, requiring supplement by more narrowly targeted studies to explore specific issues. At the same time, this data does give us a broad picture of what is going on in workplace dispute resolution across the Canadian economy, something that has not been available in the past. It is also worth recognizing that alternative interpretations of the reduction in grievance rates associated with employee involvement programs in unionized workplaces are possible. A critic of employee involvement could argue that the reduction in grievance rates really reflects the cooptation of unions and suppression of conflict under management driven lean production forms of employee involvement, which individualize employees and reduce the ability of workers to protect their interests collectively through using the grievance system. The data examined here do not allow a definitive exclusion of this alternative explanation. However, future research addressing this question could profitably address this possibility by examining in greater depth the quality of labour-management relations in these workplaces from the perspective of both management and workers.

Overall the results of this study indicate a need to move beyond a simple picture of a single, universal relationship between employee involvement and workplace conflict. The effects of employee involvement depend on the type of program that is used, and how and in what context it is implemented. There are important differences between union and nonunion workplaces in effects on workplace dispute resolution and between the goods and service sectors. Future research needs to recognize and explore these differences. It is also important to focus on the implementation of employee involvement in terms of how it affects decision-making in the workplace, rather than simply on the adoption of procedures. It would be useful, in addition, to examining overall grievance rates to look at the nature of the grievances being filed. Hopefully this type of future research could help increase our understanding of the range of different ways in which employee involvement can affect dispute resolution in the workplace, building on the findings that have been reported in this study.

Parties annexes

References

- Appelbaum, Eileen, and Rosemary Batt. 1994. The New American Workplace: Transforming Work Systems in the United States. Ithaca, NY: ILR Press.

- Barker, James R. 1993. “Tightening the Iron Cage: Concertive Control in Self-Managing Teams.” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 3, 408–437.

- Batt, Rosemary, Alexander J.S. Colvin and Jeffrey H. Keefe. 2002. “Employee Voice, Human Resource Practices, and Quit Rates: Evidence from the Telecommunications Industry.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 55, No. 4, 573–594.

- Boroff, Karen E., and David Lewin. 1996. “Loyalty, Voice, and Intent to Exit a Union Firm: A Conceptual and Empirical Analysis.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 51, No. 1, 50–63.

- Colvin, Alexander J.S. 2003a. “Institutional Pressures, Human Resource Strategies, and the Rise of Nonunion Dispute Resolution Procedures.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 56, No. 3, 375–392.

- Colvin, Alexander J.S. 2003b. “The Dual Transformation of Workplace Dispute Resolution.” Industrial Relations, Vol. 42, No. 4, 712–735.

- Cutcher-Gershenfeld, Joel. 1991. “The Impact on Economic Performance of a Transformation in Workplace Relations.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 44, No. 2, 241–260.

- Eaton, Adrienne E., and Jeffrey H. Keefe. 1999. “Introduction and Overview.” Employment Dispute Resolution and Worker Rights in the Changing Workplace. A.E. Eaton and J.H. Keefe, eds. Champaign, IL: Industrial Relations Research Association, 1–26.

- Feuille, Peter, and Denise R. Chachere. 1995. “Looking Fair or Being Fair: Remedial Voice Procedures in Nonunion Workplaces.” Journal of Management, Vol. 21, 27–42.

- Folger, Robert, and Russell Cropanzano. 1998. Organizational Justice and Human Resource Management. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Freeman, Richard B., and James L. Medoff. 1984. What Do Unions Do? New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Godard, John. 2001. “New Dawn or Bad Moon Rising? Large Scale Government Administered Workplace Surveys and the Future of Canadian IR Research.” Relations Industrielles / Industrial Relations, Vol. 56, No. 1, 3–33.

- Godard, John, and John T. Delaney. 2000. “Reflections on the ‘High Performance’ Paradigm’s Implications for Industrial Relations as a Field.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 53, No. 3, 482–502.

- Ichniowski, Casey. 1986. “The Effects of Grievance Activity on Productivity.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 40, No. 1, 75–89.

- Katz, Harry C., Thomas A. Kochan, and Mark R. Weber. 1985. “Assessing the Effects of Industrial Relations Systems and Efforts to Improve the Quality of Working Life on Organizational Effectiveness.” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 28, No. 3, 509–526.

- Kochan, Thomas A., Harry C. Katz, and Robert B. McKersie. 1986. The Transformation of American Industrial Relations. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Lewin, David. 1999. “Theoretical and Empirical Research on the Grievance Procedure and Arbitration: A Critical Review.” Employment Dispute Resolution and Worker Rights in the Changing Workplace. A.E. Eaton and J.H. Keefe, eds. Champaign, IL: Industrial Relations Research Association, 137–186.

- Lewin, David, and Richard B. Peterson. 1999. “Behavioral Outcomes of Grievance Activity.” Industrial Relations, Vol. 38, No. 4, 554–576.

- Olson-Buchanan, Julie B. 1996. “Voicing Discontent: What Happens to the Grievance Filer after the Grievance?” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 81, No. 1, 52–63.

- Osterman, Paul. 1994. “How Common is Workplace Transformation and How Can We Explain Who Does It?” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 47, 173–188.

- Osterman, Paul. 2000. “Work Reorganization in an Era of Restructuring: Trends in Diffusion and Effects on Employee Welfare.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 53, No. 2, 179–196.

- Parker, Mike, and Jane Slaughter. 1988. Choosing Sides: Unions and the Team Concept. Boston, MA: South End Press.

- Shaw, Jason, John Delery, G. Douglas Jenkins, Jr., and Nina Gupta. 1998. “An Organization-Level Analysis of Voluntary and Involuntary Turnover.” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 39, No. 5, 1–15.

- Sheppard, Blair H., Roy J. Lewicki, and John W. Minton. 1992. Organizational Justice: The Search for Fairness in the Workplace. New York: Macmillan.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Means and S.D. for Grievance Rate Estimation Sub-Samples of Union and Nonunion Establishments with Formal Grievance Procedures

Table 2

Predictors of Grievance Rates: Unionized Establishments Tobit estimates for Natural Log of Annual Grievances per 100 employees

Table 3

Predictors of Grievance Rates for Goods and Service Sectors, Union Establishments Tobit estimates for Natural Log of Annual Grievances per 100 employees

Table 4

Nonunion Establishments: Predictors of Procedure Presence and Grievance Rates

Table 5

Summary of Relationships between Employee Involvement and Grievance Rates