Résumés

Abstract

This article proposes a new conceptual framework for parent-child and adult relationships in the Civil Code of Québec based on the theory of relationships of economic and emotional interdependency. It puts forward a new théorie générale for relationships in Quebec civil law. It argues that the Code should concentrate on relationships of economic and emotional interdependency, irrespective of their form or of their fulfillment of formalities. Their content and qualities should be the law’s object, hence allowing for a functional account of families and personal lives. Doing so would require a recodification of economic and emotional relationships in the Code, to provide a more meaningful legal framework addressing families and personal lives. Fundamentally, the hope is to shift the normative content of family law in Quebec private law from “the family” to relationships, and to take a stance against family law exceptionalism.

Résumé

Cet article propose une nouvelle approche conceptuelle pour penser les relations parents-enfants et les relations entre adultes dans le Code civil du Québec. Cette approche s’inspire de la théorie des relations d’interdépendance économique et émotionnelle, et met de l’avant une nouvelle théorie générale des relations en droit civil québécois. Cette théorie générale soutient que le Code devrait se concentrer sur les relations d’interdépendance économique et émotionnelle, indépendamment de leur forme ou de l’accomplis-sement de formalités. Le contenu et les qualités des relations devraient être au coeur de l’analyse, permettant ainsi d’adopter une approche fonctionnelle dans la régulation des familles et des relations personnelles. Cette théorie générale nécessiterait une recodification des relations d’interdé-pendance économiques et émotionnelles dans le Code, afin de fournir un cadre juridique adapté à la réalité des familles et des relations personnelles. Fondamentalement, l’espoir est de déplacer le contenu normatif du droit de la famille en droit privé québécois de « la famille » vers les « relations », et de prendre position contre l’exceptionnalisme en droit de la famille.

Corps de l’article

Introduction

In 1955, the province of Quebec launched an ambitious recodification project.[1] An important aspect of this reform was the complete rethinking of family regulation. Law once conceived and regulated the family as a unitary entity despite its legal inexistence per se. The family was homogeneous in the eyes of the law, under the power of a single individual (the husband), and existed in the private domain; there was no Book on the Family in the Civil Code of Lower Canada (CCLC). Under this paradigm, the CCLC minimally addressed the family as a unit. ‘The family’ was not a legal notion in the CCLC, which dealt with one relation of power: the unilateral relationship between the husband and his belongings, which could be humans or property.[2] Through time, this paradigm has significantly changed. Now, one can hardly consider the family as unitary, homogeneous, or as a single unilateral relationship. Yet, whether the family is a ‘legal entity’ in the Civil Code of Québec (Code or CCQ) remains unresolved from a theoretical perspective.

In recent decades, the family began to hold a special place in Quebec civil law. The enactment of a Book on the Family in the Civil Code of Québec in 1980 and the inclusion of mandatory mechanisms to protect married spouses in a heteronormative paradigm in 1989 distorted the perception of ‘the family’ in the Code, making it flirt with legal personality – the family patrimony being a notable illustration of this statement.[3] However, the Code projects a misleading image of ‘the family’ in law, considering both the entity and its members. Rights, duties, and obligations have been included in the Book because they gravitated around ‘the family’, yet insufficient attention was devoted to their inscription in civil law, and in the Code. The fact that family law in the Code has been reformed almost every decade since the eighties signals that Quebec society is changing, but that the law, in its current state, lacks the required flexibility to adapt.

Steps taken since 1980 highlight how the family unit supersedes the relationships within that unit. The Code should go back to its essence and consider relationships rather than focusing on a non-legal entity identified as ‘the family’. Most importantly, the Code still hopes to channel behaviour, to be normative, and to rely on a formal account of the family. ‘The family’ in the Code, given its history and the values it has promoted, bears a strong normative content that is no longer in line with the current needs of citizens nor with basic legal principles. In the context of a long-awaited reform of family law,[4] it is essential to think conceptually about the family, relationships, and civil law.[5] It is necessary to explore alternative readings of ‘the family’ and to include, in addition to its formal rules, a functional approach to regulating ‘families’ and relationships of economic and emotional interdependency in the Civil Code of Québec.

First, this article proposes a functional approach to the family, families, and relationships in the Civil Code of Québec. This approach aims to shift the normative content from ‘the family’ to meaningful relationships—more precisely, relationships of economic and emotional interdependency. The theory of relationships of economic and emotional interdependency attaches legal effects to relationships based on functional criteria rather than formal ones.[6] It focuses on the content of relationships and proposes a formal, organized, and flexible scheme to address relationships. It also allows relationships meeting formal criteria but not sharing the meaningful content and qualities to withdraw from the scheme. Old and new relationships can be included in the Code in a consistent manner which respects the principles of the law of persons (status), obligations, property, and more. Law should concentrate on intimate[7] or privileged[8] relationships of emotional and economic interdependency[9] and their effects. This article specifically argues that the Code should target relationships of emotional and economic interdependency rather than, for example, the presence of a child or the fulfillment of formalities (solemnization of marriage). Such an approach would challenge the Civil Code of Québec’s understanding of ‘the family’ on many grounds and would provide a strong theoretical basis for the family in Quebec civil law, something that was not considered in the legislator’s most recent family law reforms.[10] By including a theory of relationships of economic and emotional interdependency in the Code, law holds the potential to evolve with time, to adapt to other mechanisms regulating the family, and to embrace fluctuating state objectives and citizen needs.

Second, this article offers a recoding of relationships of economic and emotional interdependency in the Code. With this recoding, there is no need for a Book on the Family; rather, mechanisms affecting intimate relationships should be included in other books, in line with their nature and functions. It is not about eliminating the normative project of the regulation of families, but about shifting it toward a different one, one where ‘the family’ is one of many ways to be interdependent and one where the qualities of relationships matter more than their form. The proposed model challenges the paradigm of choice and autonomy and suggests engaging with a combination of freedom, autonomy, solidarity, and protection, while acknowledging the issues promoting this combination of values imported in the scheme. Protection limits freedom, and solidarity impedes autonomy. The idea is not to think about these as antipodal, binary, or exclusive. It is rather about striking a balance that best meets the needs and expectations of citizens: a balance between protection and freedom, between solidarity and autonomy. Focusing on relationships allows one to move away from a logic of channelling, a logic of form, a logic where formalities (some could say contract) are the only bases of conjugal status and where title is the most important element when it comes to parent-child relationships. This novel approach has the potential to clarify the underlying elements—functions, nature, status, interdependency—regarding the establishment of adult and adult-child relationships.[11]

I. Toward a Theory of Relationships in the Civil Code of Québec

A strong theory of relationships for family law in Quebec can provide a way to infuse the regulation of families and intimate relationships with a functional approach while respecting the Code’s preference for formalism. The Code should regulate specific relationships performing certain identified functions, whether they are formal or not. This would be a move toward a functionally defined ‘family’ and would challenge the dominant understanding of ‘formalism’. Relationships have multiplied in family law since 1955,[12] but have rarely been analyzed on the basis of their content. Relationships have been regulated based on their form, but this is only one of various options available in the toolbox of civil law. Form performs functions. As Justice Abella wrote in her dissenting opinion in Quebec (Attorney General) v. A: “the history of modern family law demonstrates [that] fairness requires that we look at the content of the relationship’s social package, not at how it is wrapped.”[13] This article builds on her advice. A different way to mobilize the notion of status in family matters can reinforce a functional approach to family law. ‘Status’ does not have to be triggered by formal elements only. Status could be triggered by functional elements, or by a situation juridique rather than by the accomplishment of formalities. The approach is not flawless and “it reflects the difficulties inherent in building a theory (and practice) that adequately reflects both the social and the individual nature of human beings.”[14] It is also compatible with civil law and not a common law theory.

Family law is not just about formal unions and formally recognized offspring as current family law in Quebec is written. Rather, it is about persons, and in particular, relationships that the state decides to promote, foster, and protect. ‘The family’ of the Code does not currently reflect the lived experiences of citizens.[15] The relationships that are included in the Code have increased over the years to include same-sex marriage, civil union, blood relations, adoption, and assisted procreation. Yet, numerous other relationships are still absent, notably unmarried spouses, step parenting, and romantic or platonic polyamory.[16] It is time for the Code to reach further and address relationships of economic and emotional interdependency based on their content and qualities.

A.Relationships of Economic and Emotional Interdependency in the Civil Code: Adult Relationships

Quebec being in the midst of reforming the family sections of the Civil Code is an ideal context to offer a new theoretical approach to familial relationships.[17] What are the essential elements of these relationships? What values should animate the regulation of intimacy? In common law, Brenda Cossman, Bruce Ryder, John Eekelaar, and the Law Commission of Canada provided frameworks, albeit in different contexts, to alternatively approach intimate relationship regulation.[18] How can these ideas inspire Quebec civil law?

Despite the present variety of forms of intimate relationships, family law has systematically relied on a formal account of the family to evaluate whether a legal relationship between adults or between adults and children exists. Broadening the conditions d’existence of ‘familial’ relationships and evaluating what substantive qualities comprise them is necessary. Adequately codified rules have the potential to evolve with time and to adapt to society’s needs. A theory of relationships of economic and emotional interdependency would integrate family law rules in the Code in a consistent and flexible way and allow for a paradigm shift as to what matters in the regulation of intimate life.

Proposed Framework

To move beyond the current rules-heavy reliance on formality and narrow understanding of what triggers conjugal or adult interdependent status, it is necessary for the proposed framework to predominantly evaluate the qualitative aspects of relationships. The Code should not grant family status and protections based solely on formalities.[19] This is, to some extent, in line with what the Comité consultatif sur le droit de la famille proposed in its 2015 report. Indeed, the Comité proposed[20] to use the definition found under section 61.1 of the Interpretation Act (CQLR c I-16) to broaden the spectrum of conjugal relationships in family law. Such a definition allows for the recognition of de jure and de facto spouses and includes the duration of the relationship between spouses and the presence of a common child as triggering elements for conjugal status. This is a potential option to step away from the superior status traditionally allocated to de jure relationships. It suggests that what private law conceives as ‘conjugal’ should revolve around formalities and some qualities of relationships (such as length, presence of a child, residency). However, expanding the definition of conjugality does not account for the multitude of interdependent adult relationships. In fact, conjugality may or may not materialize in an interdependent relationship.

To use the Law Commission of Canada and Cossman & Ryder’s terminology, an alternative is to put forward a scheme of ‘ascribed status,’[21] albeit ‘modified ascribed status,’ for the CCQ. Per the Commission, “[a]scription refers to treating unmarried cohabitants as if they were married, without their having taken any positive action to be legally recognized.”[22] Formal conjugal relationships would still trigger status, but they would not be the only way to trigger ‘privileged’ status. Furthermore, such relationships would not necessarily trigger status and produce effects without regard to the actual qualities of the relationships. The modified ascription scheme would not attempt to destroy or undermine habitual religious, cultural, or societal relationships. It is rather about bringing consistency to the regulation of intimate relationships and building upon what is already in the Code.

The conditions juridiques set forth in section 61.1 of the Interpretation Act need to be expanded and modified. Formal unions—marriage and civil union—should create an interdependent status. De facto conjugal relationships meeting certain qualities (such as length, sharing a community of life, sharing a dwelling, etc.) should also create such status. The qualities set forth in section 61.1 of the Interpretation Act are a starting point, but social debate and empirical data are essential to determine how interdependency should be legally codified. Furthermore, these relationships would not account for the presence of children. This is not because children do not create interdependency, but rather because interdependency occasioned by the presence of a child should be dealt with through refining the legal status of relationships between adults and children, as I will explain below.

The interdependency status would be presumed for both de jure and de facto relationships, but the presumption would be rebuttable. The spouses would thus have an ascribed interdependency status. The presumption of interdependency is a legislative choice aimed toward assisting the party likely to be less powerful in proving interdependency. While it may restrict autonomy and freedom, it promotes protection. Interdependency status would thus be automatically recognized. But this would not address the actual content of the relationship. As such, it would be possible to prove a spouse was not in a relationship of economic and emotional interdependency, despite the fact that they were in a conjugal union (de jure or de facto). To rebut the presumption, the spouse would have to prove, on a balance of probabilities, that the test determining interdependency does not apply to their situation.

The test has two steps. First, if the relationship were to end today, would the emotional and economic well-being of the spouse—assuming they were included in a privileged relationship—be jeopardized? The notion of ‘emotional and economic well-being’ would need to be refined and developed in consultation with specialists of other disciplines; [23] courts, to some extent, could also shape it, like they have done in the common law for ‘marriage-like’ relationships.[24] If the answer to this first step is no, the interdependent status does not apply. However, if the answer is yes, the test proceeds to the second step, asking: would a spouse in a similar situation have reasonable expectations that the relationship was one of emotional and economic interdependency? The constitutive elements of economic and emotional interdependency could rely on classical civilian concepts such as tractatus (treatment), fama (reputation), and actions. The idea here is to suggest a new way to apprehend relationships in the Code, shift how society thinks about them, and determine how to best include them in private law. The approach and the test would need to remain flexible and rely on abstract notions to adapt to the changing needs of families and evolve with societal transformations. The approach and the two-step test represent a balance between solidarity and protection, and autonomy and freedom.

Most situations of adult interdependency would be covered with this proposed test. However, if the qualities and content of relationships are what matter, it is essential not to exclude relationships of emotional and economic interdependency between adults that are not living conjugally. Doing so would defy the purpose of looking at the qualities and the content of relationships, and of focusing on the substantive elements of relationships. As such, adults in relationships of emotional and economic interdependency that are not necessarily perceived as such—because they are not conjugal—could claim interdependency status. The test would allow for ‘non-conjugal’ adult relationships of economic and emotional interdependency to be considered equivalent to conjugal ones. The same two-step test would be used, but differently. For conjugal relationships, the test is used to rebut a presumption. For non-conjugal relationships, the test is used to claim a status. As such, the person claiming an interdependent status would have to prove, first, that if the relationship were to end or transform, their emotional and economic well-being would be jeopardized. Second, they would have to prove that a person in a similar situation would have reasonable expectations that the relationship was one of emotional and economic interdependency.

The aims of this model are to engage in a much-needed paradigm shift in Quebec family law, increase consistency in the Code and with rules found beyond the Code, attune law to citizens’ expectations, and provide the flexibility necessary in an ever-changing field of law.

Applying the Proposed Framework

The following provides some concrete examples of how such an approach would apply to different relationships. Other examples could have been proposed—polyamorous relationships, friends cohabiting—but are not in the interest of concision. The facts of Quebec AG v. A are the source of the first example. As summarized by the Supreme Court:

A and B met in A’s home country in 1992. A, who was 17 years old at the time, was living with her parents and attending school. B, who was 32, was the owner of a lucrative business. From 1992 to 1994, they travelled the world together several times a year. B provided A with financial support so that she could continue her schooling. In early 1995, the couple agreed that A would come to live in Quebec, where B lived. They broke up soon after, but saw each other during the holiday season and in early 1996. A then became pregnant with their first child. She gave birth to two other children with B, in 1999 and 2001. During the time they lived together, A attempted to start a career as a model, but she largely did not work outside of the home and often accompanied B on his travels. B provided for all of A’s needs and for those of the children. A wanted to get married, but B told her that he did not believe in the institution of marriage. He said that he could possibly envision getting married someday, but only to make a long‑standing relationship official. The parties separated in 2002 after living together for seven years.[25]

In the proposed framework, A and B are de facto spouses, so they would be presumed to be in a relationship of emotional and economic interdependency. For my purposes, let’s assume that B tries to withdraw from the relationship of emotional and economic interdependency. Thus, we would begin the analysis by asking the question: should the relationship end, would the emotional and economic well-being of A be jeopardized? B would have the onus of demonstrating these questions are answered in the negative. For example, B could prove that A has a place to live and minimal income to fulfill her basic needs, that she would have moved to Canada anyway, that she could maintain a standard of living, etc. If B’s arguments are sufficiently persuasive, the parties would be deemed strangers toward one another in private law. In other words, there would be no interdependency status resulting from their relationship.

However, if A’s socio-affective or economic well-being are found to be jeopardized by the relationship’s termination, it would be necessary to consider step two by examining the reasonable expectations of the parties. Did A have reasonable expectations that the relationship was one of economic and emotional interdependency? Here too, a presumption would exist in the affirmative, and B would have to negate it. Once again, the criteria would need to be determined after consultation with experts and stakeholders, as should be done with all legislative amendments, but could include questions such as: did the parties have a ‘life plan’ or shared access to a bank account? The criteria should be functional, flexible and not necessarily chosen in reference to married unions. Some should emanate from the legislature, but judges would adapt these as circumstances go. The parties themselves would adapt these in their dispute resolution negotiations. The idea is to determine the nature of the parties’ interdependence and how it affects their economic and emotional decisions. For example, B could demonstrate—using tractatus, fama, and actions—that the parties were not interdependent. The threshold to meet the test’s requirements should not be impossibly high; otherwise, the freedom and autonomy of the parties would be curtailed. However, solidarity between the spouses and the protection of interdependent parties would necessitate that the threshold is in line with the expectations of citizens, mirroring the message sent in other regulatory frameworks and considering the ever-growing privatization of support combined with the shrinking of the welfare state.

Let’s now repeat the exercise using another situation of interdependency. C and D are ‘DINK’s (double income, no kid). They behave as a couple, share a place they rent, have similar incomes and pension plans, split bills pro-rata, have always seen themselves as financially independent, and more. They have been together for seven years in a situation of intimacy and share economic and emotional aspects of their lives. As de facto spouses, the presumption of interdependency would apply to them. However, they may not be legally interdependent where the transformation of the relationship would jeopardize their well-being and where they had legitimate expectations that the relationship was one of economic and emotional interdependency. The parties may agree as to their apparent interdependency status; however, they may also agree that their well-being would not be jeopardized by the termination of the relationship, which entails that they are not interdependent according to the test proposed. C and D will continue their life separately. Ideally, they would share their belongings amicably and make an agreement.

This scheme would also apply to relationships outside of the ‘conjugal’ paradigm. For these relationships, no presumption of interdependent status would be available. The test would remain the same, but the burden would fall on the person claiming to be in such a privileged relationship. The Beyond Conjugality Report provides an example that has been adjusted to which the test may be applied:

We are thirty-six-year-old twin sisters who have never been married or had children and who live together … Our lives are inextricably linked: aside from being related and having known each other all of our lives, we have co-habited continuously for the last seventeen years (since leaving our parental home), rely on each other for emotional support, and are entirely dependent on each other financially – we co-own all of our possessions and share all of our living expenses. … Yet, because we are sisters, rather than husband and wife, and because we are not a couple in a presumably sexual relationship, we are denied … advantages constructed upon sexist and heterosexist ideas about what constitutes meaningful relationships.[26]

Considering how the proposed approach applies only to private law and in the Civil Code,[27] in the event that the twin sisters foresee their partnership ending, would it be possible for them or one of them to claim interdependent status? Obviously, it is not an issue if, despite the transformation of their partnership, they remain on good terms and agree to continue supporting each other, given their expectations that their relationship would continue working that way. But, if the sisters’ understanding of what they reasonably expect from one another diverges, then the test could help.

We would first apply step one: should the relationship end (and not transform in nature) now, would the emotional and economic well-being of the sister claiming interdependent status be jeopardized? Given the situation they described to the Law Commission, it is likely that the answer to this first question would be yes. Assuming both sisters see the description of their partnership as accurate, elements such as cohabitation (having nowhere to live), explicit emotional support (emotional distress), and financial dependency (economic difficulties) would weigh strongly in favour of answering the first question in the affirmative. If these elements were negatively impacted, the well-being of the sister claiming interdependency status would be jeopardized. Next, we would apply step two: did the claimant have a reasonable expectation that the relationship was one of economic and emotional interdependency? Based on their collaboration, the actions of the parties, their expressed intentions and other criteria still to be determined, the claimant would have to prove on a balance of probabilities that her expectations were reasonable. The interdependency status would thus rely on qualitative elements of relationships, rather than the fulfillment of formalities or their resemblance to an idealized and apparently homogeneous ‘conjugal status’. This reframing puts forward a different understanding of relevant intimate statuses in the Code. Such a way of conceptualizing relationships—focusing on function over form in regulating adult relationships and de-centring conjugality as a marker of interdependence—allows for more relationships to be meaningfully recognized and regulated.

B. Relationships of Economic and Emotional Interdependency Expanded: Adult-Child Relationships

What about adult-child relationships? Possibilities for parent-child relationships have also multiplied in recent years. Despite this blooming of possible legal relations between adults and children, Quebec family law remains formal and under-inclusive in its approach to meaningful relationships between adults and children. In some ways, it relies on the fulfillment of formalities.[28] In others, formalities may be lacking.[29] The binary logic underlying filiation also displays a preference for a formal rather than a functional account of meaningful relationships in law. While the status/contract debate plays out quite differently when it comes to parent-child relationships, there is a theoretically inconsistent fear of the ‘contractual’ filiation that is absent when it comes to adult relationships.[30] This fear contributes to making the principles animating the titles of the Code’s Book on the Family inconsistent: for adult interdependency, the law operates according to a strong contractual understanding of the union, but contractualizing filiation is unthinkable. This subpart of the article proposes a different approach to regulating parent-child relationships, rooted in a functional account of meaningful relationships and in the importance of recognizing interdependency when it comes to ascribing status. As with adult relationships, it builds on pre-existing principles, but indicates how qualities of relationships should matter over their form, or rather, over the fulfillment of formalities.

To be clear, the claim is not that relationships between adults are similar to those between adults and children, or that the State should regulate adult-child relationships in the same way that it regulates adult interdependency. Scholars have rightly expressed concerns about such an amalgamation.[31] For example, John Eekelaar notes how “[u]nlike intimate partners, children have no choice in the relationship; it is not a relationship between equals.”[32] My work claims that parent-child relationships are also relationships of emotional and economic interdependency, that they could operate on the basis of a ‘modified ascription model’, and that, in some cases, a functional account of relationships would be desirable. In short, relationships between adults and between adults and children are different, yet they can be regulated on the basis of coherent and consistent principles.

Inconsistencies in the Current Framework

Different foundations for filiation

The CCQ still relies on distinct frameworks for maternal and paternal filiation,[33] despite both parties having similar rights, powers, duties, and obligations. The fundamental element underlying paternal filiation, now called filiation by acknowledgement, is volonté (will or intent), while a particular understanding of biology underlies maternal filiation, now referred to as filiation by blood.[34] Quebec’s civil law framework focuses on giving birth—i.e. delivery—as the materialization of biology. Biology could be premised on a genetic connection to the child, for instance, but it is not, and is instead in line with the Latin maxim mater semper certa est (the mother is always certain). These different foundations for filiation are largely left unquestioned by mainstream legal scholarship and the legislature.[35] The gender biases of these codal rules are demonstrated in various ways, two of which are the most relevant for present purposes: the different paths of arriving at the act of birth and the possibility for a woman to declare who is the ‘father.’ Since June 6, 2023, these gender bias rules are even codified at article 523, paragraph 1 of the CCQ.

When it comes to filiation by birth, which was formerly known as filiation by blood and through assisted procreation, as per articles 111 CCQ and following, the birth mother (or parent) needs to be identified as such by a third party and her information needs to be transmitted alongside the declaration of birth to the Registrar of Civil Status. This is necessary for an act of birth to be drawn. In the event where no attestation is available, the Registrar of Civil Status can authorize officers to inquire, request health documents, require a letter explaining the reasons why certain documents may not be available, ask for testimonies under oath of two witnesses, and more.[36] Since June 6, 2023, there is even an obligation for the mother or person who gave birth to declare their filiation at article 113.1 CCQ. This demonstrates the importance of the attestation matching the declaration and reflecting ‘biology,’ and is also disproportionate compared to what is asked for paternal filiation (filiation by acknowledgement). Indeed, the father (or parent) field on the act of birth relies on the declaration of the father, or rather, of the man declaring his paternal filiation to the State. He may or may not be the biological father, and the law disregards this fact. Paternal filiation relies mostly on the intent to be a father. This betrays an important problem regarding how filiation is conceived and operates in Quebec family law. Paternity is a legal construct that may or may not match a biological situation. However, there is no place for ‘filiation as a legal construct’ when it comes to maternal filiation. Maternal filiation must mirror certain biological facts.[37]

The requirement that the attestation and declaration of birth correspond as it pertains to maternal filiation, now labelled filiation by blood but anchored in birth, is relatively new. Yet, since 1991, the entrapment of women in their biological functions has only gained momentum. This is paradoxical, to say the least, given the efforts of the Minister of Justice and French Language Simon Jolin-Barrette to degender the Books on Persons and Family in the Code and the tendency to use the term ‘parents’ instead of fathers and mothers. The requirement was introduced with the reform of the Registrar of Civil Status and the Civil Code of Québec in 1991. Before, such correspondence was not necessary and attestations of birth were under the purview of public health law.[38] Attestations of birth had a different weight. Germain Brière flagged this issue in 1986. Indeed, when it was proposed that the attestations of birth produced under the Loi sur la protection de la santé publique be transferred to the Registrar of Civil Status, Brière noted that

[l]es déclarations de naissance … faites en vertu de la Loi sur la protection de la santé publique acquerraient ainsi une autorité qu’elles n’ont pas actuellement ; exigées essentiellement pour des fins démographiques, ces déclarations constitueraient désormais, vu leur intégration partielle au registre de l’état civil, des moyens de preuves de l’état des personnes. Dans la situation actuelle, ces déclarations ne constituent certainement pas … un mode normal de preuve de l’état civil[.][39]

The attestation of birth was statistical[40] and demographic. It now curiously produces effects on the law of persons which are disproportionate for women or birthing parents. I suggest that the attestation of birth should be abolished as an element of the law of persons, because it is one reason why the foundational elements of filiation (biology for women, will and intention for men) still differentiates between the parents and is informed by biological ideals. Only the declaration should be relevant for establishing filiation. This is not what the reform did, further entrenching differences between filiation bonds. Indeed, filiation by birth is now either by blood or by acknowledgement, making the issue salient.

There is a second related issue pertaining to the difference between rules for maternal and paternal filiation. It is possible for a man or other parent not to declare their filiation, and, unlike mothers, they have no obligation to do so. In this case, between 1980 and 2022, if the parents were unmarried, the mother could elect not to declare the man as the father of the child.[41] This has been modified by Bill 2. The mother can now declare on behalf of the other parent,[42] but there remains no obligation for mothers, fathers, or parents to do so. Such rules do not mean that the mother has no recourse to see paternity established, yet it means that there are hurdles to having it recognized. In contrast, it would be difficult for a birth mother (or person) not to declare her filiation toward the child,[43] and if she wanted to, she would now be in contravention of article 113.1 CCQ. Also, some fields on the declaration of birth and acts of birth may be left blank by choice. For example, single motherhood by choice is an option when it comes to filiation. Moreover, these gender-biased rules may be a reason why Quebec family law refuses to adopt the language of ‘parent’ exclusively, rather than mother/father/parent,[44] despite the fact that they entail the same effects.

Different rules for different conjugal statuses

Another difference in the nature of filiation rules is directly related to the overreliance on formalities and formal rules in the Second Book of the Civil Code of Québec. Between 1980 and 2022, de facto partners were not provided with the same rules to see their filiation established as de jure partners. This manifested in two ways and could have negative consequences for certain parents and children. First, in the law of persons, while married parents could declare filiation for one another, unmarried parents could not declare filiation but for themselves.[45] This difference has been attenuated by article 114, paragraph 2 of the Code, but extra steps are still required for de facto spouses to prove their union. Second, there was traditionally no presumption of paternity or parentage for unmarried parents—though this has changed with Bill 2.[46] To a certain extent, not only does the Civil Code rely on a formal understanding of relationships when it comes to relationships between parents and children, it also structures filiation depending on which parent you are (the birthing parent or the other) and according to the type of conjugal relationship you are in.

These examples are not the only ones where a formal understanding of the family prevails despite the lived experiences and the actual relationships at play. De facto parents differ from de facto partners. While the former label applies to adults acting in fact as parents—such as step-parents or significant adult figures—the latter refers to unmarried couples. De facto parents are almost completely left out of the Second Book, except for one provision about the adoption of an adult child and one provision about parental authority.[47] This does not mean that they are absent from the Code,[48] yet they are not formally recognized and have little to no rights and obligations, even if they may voluntarily assume some.[49]

Different rules for different types of filiation

There is a second broad category of issues showcasing the inconsistencies of filial rules. The Civil Code of Québec has gradually recognized other possible relationships between adults and children. While at first, the only desirable option was legitimate filiation—the quintessence of a formally accounted-for family—the Code has gradually added filiation by blood, filiation of children born of assisted procreation, and adoption. Since 2023, new categories have been introduced in the Code: filiation by birth and filiation by acknowledgement.[50] Yet, until now, while some elements of filiation flirt with a functionalist account of relationships (possession of status being an obvious example), relationships in the Code between adults and children continue to rely on a formal account of the family. Most importantly, the nature of filial rules varies depending on the ‘type’ of filiation, as do the underlying principles animating filiation. Some rules are status oriented—status being understood as ‘meeting formal requirements’ or being ‘natural’—and other rules are based on intent.[51] These competing underlying principles animating filial rules highlight the artificial typology of relationships in the Code, which are even more apparent with the amendments made in 2023 by Bill 12.[52]

The history of filial relationships in the Code demonstrates the absence of a consistent conceptual model for filial relationships. Once possible relationships between parents and children started multiplying, the Code became disorganized. Elements underlying filiation by blood became mostly biology for women and mostly intent for men. In some cases, biology matters for men too.[53] While there is a common sense belief that contractualizing filiation is problematic,[54] it is how the Code understands filiation of children born of assisted procreation.[55] When reforming ‘family law’, rules about adoption are rarely addressed and their reform happens separately. This inconsistency in the underlying elements of filiation rules should not be left unaddressed by reformers and scholars.

The evolution of the structure of the Code is also puzzling because it suggests a lack of a solid foundation to the edifice of filiation. The structure of the Code has fluctuated not because of actual changes in the nature of relationships, but because of changes in political views on the family and its members in law. For example, it is sometimes believed that the parental project provided for by article 538 CCQ and assisted procreation were introduced in the Code in 2002. However, the Code included the parental project as early as 1994,[56] and articles dealing with assisted procreation were found in the 1980 version of the Book on Family.[57] At that time, it was clear that assisted procreation was included under the regime of filiation by blood as it was only available in situations mimicking ‘natural’ reproduction. As such, the parental project did not appear in 2002, but rather the legal imaginaire was struck by the political fight ‘won’ in 2002 by people resorting to non-heterosexual reproduction to create their families. Given the differences between this form of reproduction and the ‘natural’ model, this type of filiation has been removed from the Chapter ‘Filiation by blood’ and included in a chapter of its own.[58] It is now back under the Chapter about filiation by birth,[59] but the entire typology of filiation was turned upside down by Bill 12.

Proposed Framework and Examples

Until 6 June 2023, there were three types of filiation in the CCQ: filiation by blood,[60] filiation of children born of assisted procreation,[61] and adoption.[62] Paternal and maternal filiations were dichotomized and there was ‘second parent’ filiation in the hypothesis of assisted reproduction. Bill 12 muddied the typology of filiation,[63] but a child can nonetheless only have one or two parents, and the Code continues to assume that a child is part of a conjugal family.[64] However, all these ties are filial, have a similar role in law, and share qualities. To the law, these bonds have the same content and produce like effects, and therefore should operate according to consistent principles. Filiation should not be reliant on overly complex typologies[65] or invested with anxieties about how families are conceived. What is important for codified rules is to have a certain level of abstraction, flexibility and consistency. Relationships of emotional and economic interdependency provide these features.

Filiation is a status of interdependency. Instead of favouring types of filiation—maternal, paternal, by birth, by blood, by acknowledgment, of children born of assisted procreation, and adoption—the Code should provide a spectrum with two predetermined categories: reproduction or procreation, and adoption.[66] The Code’s emphasis should depart from who reproduces and how in favour of the fact that there is a child with a relation to a parent. With this approach, no distinction is necessary between maternal and paternal filiation. The law of filiation provides for legal constructs and not for mere biological facts. There is no sound reason to propose opposite foundational elements, such as ‘biology’ for mothers and intent for fathers; the focus should be primarily on parents. Intent/volonté should be the fulcrum for all, and biology can be an element to look at when there are questions surrounding intent. The opposite—i.e. an emphasis on biology—is harder to justify, both theoretically and practically. If ‘biology’ was the core element promoted, the law would be of limited use and numerous situations where there is a functional parent-child relationship without a biological component would be excluded. One can think of adoption or assisted reproduction as examples.

How would this filiation anchored in intent[67] materialize? As it has been suggested in 2015 by the Comité consultatif sur la réforme du droit de la famille (Comité), proof of filiation should be renamed modes d’établissement. These modes d’établissement would remain mostly the same, namely: the act of birth, the possession of status, presumption, and acknowledgement.[68] Some modifications to the rules in the Code for filiation anchored in intent would be necessary. First, the requirement of corroboration between the attestation of birth and the declaration of birth should disappear. This would allow for the declaration of birth—presumably the manifestation of intent for all parents—to be the basis of filiation under the Chapter ‘filiation by reproduction/procreation/birth’. If the State wants to keep an attestation of birth for statistical or demographic purposes as was done before, doing so should not have an influence on relations in private law. In addition, the possibility to declare the other parent should be available to all.[69] Possession of status would remain roughly the same device. It is probably a good idea to suppress the name requirement in the evaluation of what constitutes adequate possession of status, in line with both what the Comité proposes and with what the courts are already doing,[70] because spouses and children do not automatically share a common last name anymore. Contrary to what is now suggested in Bill 2 and what was done with Bill 12,[71] the length of the possession of status should remain flexible and be evaluated by judges, on a case-by-case basis. Care could be added to the constitutive elements of tractatus. More importantly, a reflection on the important qualities of possession of status should be introduced. To be meaningful, possession of status must be understood as a period of time during which a relationship with particular characteristics emerges. Filiation does not crystallize at birth; it is the result of many things including intention, a formal status (act of birth) and behaviour between an adult and a child. Administratively, it can be seen as crystallizing at birth to facilitate interactions with the State (regarding matters such as health, taxes, and social benefits), but not in private law, and not if the functional approach to relationships is taken seriously. Sadly, most of these elements were overlooked in Bill 12.

Presumptions available to heterosexual and non-heterosexual non-birthing de jure spouses should be extended to de facto spouses; this was done with Bill 2. However, it should be clear that a ‘conjugal union’ between the parents is not mandatory, nor relevant, for filiation to ensue. There would be a new feature to the modes d’établissement: both voluntary and involuntary acknowledgement would be contemplated. Voluntary acknowledgement was abrogated in 2023; it was limited in scope and probably overlapped with the “tardy declaration” found at article 130, paragraph 2 CCQ. The tardy declaration is a declaration made more than 30 days after the birth of a child. Voluntary acknowledgement did not need to be abrogated and there should be an inclusion of involuntary acknowledgement as a mode d’établissement. This mechanism could be inspired by former article 540 CCQ and allow for responsibility and identity, without parental authority. This mode d’établissement would include DNA testing and negative inferences (535.1 CCQ) and it could be relied on to tie an adult to a child in the absence of intent. Further, the lock of filiation found in article 530 CCQ would remain relevant; if possession and title match, no claim or contestation can be made. In some cases (such as a parental project), the lock of filiation should apply even if there is only one parent on the act of birth. As I later describe, civil law should aim to reach beyond biparentality when it is necessary, such as when there are multiple relationships of interdependency.

Second, relying on these new imperatives and rules, the structure of the Title on Filiation should be modified. Categorizing the types of filiation depending on how a child was conceived is useless, since established legal ties have the same effects. Indeed, a child could have a ‘blood/natural’ filiation combined with an ‘assisted’ one. Categorization based on conception method confuses the foundational elements of filiation by distinguishing them depending on the gender of the parents or the means by which they elected to procreate. As such, civil law should start working with a different dichotomy: filiation by procreation/reproduction/birth[72] and filiation by adoption. How the child is conceived is irrelevant. Assisted reproduction used to be part of filiation by blood, and the theoretical foundations of this choice were stronger back then. In this alternative dichotomy, reproduction would be a residual category. In civil law, a residual category is a way to include all possible situations but for one in a category.[73] As such, reproduction would become a residual category including both all relationships of interdependency that are not adoption and assisted reproduction regardless of its type (medical, home insemination, sexual intercourse). This is a choice based on an opposition that has animated Quebec civil law since the eighties. Recognizing that adoption is a form of reproduction—social reproduction—it appears impossible to have only one type of filiation for now. This does not mean it is not what civil law should aspire to, since the content, qualities, functions, and effects of adoption and other filial bonds are similar.

The third essential element of this approach to filiation is that reproduction/procreation/birth and adoption trigger an interdependency status. Other meaningful relationships between adults and children could also lead to an interdependency status. Indeed, if relationships share the same content, functions, and qualities, they should have similar legal effects.

There are obvious differences to highlight regarding relationships between adults and relationships between adults and children, so some nuances are in order. David Archard identifies a few of these differences: a relationship between a parent and a child “is one between an independent superior and a dependent subordinate” [74] and “lovers and friends are chosen, whereas a child does not choose her parents.”[75] While these differences may oversimplify choice and dependency—for example, the circle of life may render older parents as vulnerable as children—they do resonate more in public and social law than in private law.[76] As John Eekelaar explains, the biggest difference between adult relationships and adult-child relationships is that children are dependent and vulnerable. He writes how “[a]ll actions between parents and children must in principle be open to scrutiny because of children’s vulnerability to harm and exploitation.”[77] Here again, even if these differences are also part of private law, exploitation and harm resonate with the logic of public law. In private law, adults—especially in a scheme where intention is central—choose, through their actions, to have or build relationships with children. Sometimes, adults do not have a choice. Children likely never choose, but there are mechanisms to protect their interest beyond private law. When relationships are catastrophic and detrimental to the well-being of children, social and public law come into play. The State intervenes and tries to prevent harm to vulnerable minors. This does not mean that relationships between adults and children are automatically disqualified from private law and from interdependency status. These relationships, from a private law perspective, remain relationships of interdependency or dependency with emotional and economic aspects.

As with adult interdependency, the proposed scheme builds on existing rules and allows for parties to claim an interdependency status. It is possible to assume that the current formal scheme fulfills some functions, such as certainty, but that other relationships could be included in the Code on the basis of reproducing similar characteristics. In contrast with adult relationships, it would not be possible to opt-out. As previously explained, the rules of filiation differ depending on the types of filiation and on whether the parent is a birthing person or not. However, generally speaking, the ‘regular’ rules rely on a mixture of title and possession. Title relies on the act of birth. I propose to have title rely on the declaration of birth and to allow conflicting declarations to be adjudicated by a judge.[78] Detailed modifications to the rules governing the establishment of filiation are suggested above, but what is innovative here is that it would be possible to claim a parent-child or adult-child interdependency status on the basis of functional similarity with these rules. While form and rules remain important, other relationships could be included on the basis of being functionally equivalent to current recognized relationships of economic and emotional interdependency.

It is important to point out that interdependency status can develop over the course of a relationship, too. As such, interdependency status would be triggered by the classical dyad of title and possession of status. However, in the event where there is no title, a person could, by relying on modified possession of status, claim interdependency status. To claim this status, the child or the adult (or both) in the relationship would need to demonstrate that they meet the requirements for modified possession of status. Modified possession of status would differ from possession of status on several accounts. Traditional possession of status relies on tractatus, fama and nomen (name). It generally must begin at birth and continue uninterrupted. Its length is variable, but it normally ranges between 16 and 24 months, the latter being what Bill 12 codified at article 524 CCQ.[79] Modified possession of status would not include nomen—as is recognized by leading case law—and would not necessarily begin at birth, with some exceptions aimed at addressing parents trying to exclude other parents. It could start before birth of after birth in specific scenarios, such as in the case of a parental project or step-parenting. The duration of possession of status would need to be informed by data and expertise about meaningful relationship formation. Once modified possession of status is established, the same test as the test to recognize adult interdependency could apply. However, given the fact that the child is likely always the vulnerable party to the relationship, the test should be applied from their standpoint. First, should the relationship end (or transform), would the socio-affective (emotional) and economic well-being of the child be jeopardized? Second, if the answer to the question is yes, would a child in a similar situation have reasonable expectations that the relationship was one of emotional and economic interdependency? Let us apply the test to examples.

The first example is the ‘mainstream’ hypothesis. The filiation of a child born of a man and a woman in an intimate relationship would be established using mostly existing rules. Both the man and the woman would fill a declaration of birth and would send it to the Registrar of Civil Status. The Registrar would draw an act of birth. One can assume for the purposes of this example that the parents would meet the requirements for possession of status. This child’s filiation could not be contested or claimed. As will be explained later, this does not mean another relationship of interdependency could not arise. All in all, for the vast majority of situations, the proposed rules would not change anything.

Relationships with a child born through a surrogacy agreement is the second example. The example has two sub examples: a scenario where everyone agrees as to who are the child’s parents, and one where someone disagrees. In a scenario where everyone agrees, the intended parents would both declare birth and meet the requirements for possession of status, with the consequences it entails. In a scenario where the surrogate and the intended parent(s) disagree as to who will be the parent of the child, the surrogate, and the intended parent(s) would declare birth specifying that there is a contestation as to the filiation of the child.[80] The Registrar of Civil Status would not issue an act of birth until the filiation is established through a court declaration. Nothing under these proposed rules would prevent more than two parents from declaring birth, and if these declarations are non-contentious, plurifiliation would easily be included in the Code. If plurifiliation remains excluded from the edifice of filiation, it should be done explicitly.

The third example is when a step-parent or child claims interdependency status. While more careful consideration is required for this scenario, different rules would apply depending on who claims the status. A presumption of interdependency for adult-child relationships should play in favour of a child. A step-parent would need to demonstrate modified possession of status. To do so, they would need to prove that, during a period of time to be determined, they treated the child as if it were their own (tractatus) and third parties believed or knew that this person assumed the role of parent to the child (fama). Once modified possession of status is demonstrated, the test evaluating interdependency would apply. Should the relationship end (or transform), would the emotional and economic well-being of the child be jeopardized? Second, if the answer to the question is yes, would a child in a similar situation have reasonable expectations that the relationship was one of emotional and economic interdependency? If so, interdependency status exists and the relationship between the adult and the child should be understood as a parent-child relationship akin to filiation by reproduction. This relationship could be established while one of the parents of the child and the step-parent are still together and it would not exclude the other parent. The duration of and criteria for modified possession of status should be carefully selected as relationships of interdependency would provide a status and entail legal effects. Special awareness should be given to family violence and coercive control before granting such statuses.[81] These effects will be considered in greater detail in the following part.

II. Recoding Relationships: Locating Status and Allocating Effects

The Book on the Family was a historical and contextual necessity. Political choices were made. To ensure family law survives beyond the contemporary period of socio-political changes, it must be better integrated in private law and in the Civil Code of Québec. Where do relationships and interdependency statuses fit in the Code? And what are their effects? This section proposes to recode relationships of interdependency and their effects in the Civil Code of Québec.

For a theory of relationships of emotional and economic interdependency to work, some recoding is necessary. Recoding is important. In a civil code, structure can send a message as strong as the rules. Recoding can counteract ideas that are currently prevalent[82] and criticized in family law theory, such as family law being “peripheral to the heart of law,” “the periphery of private law,” “ambiguously situated in an area that is neither entirely private nor entirely public,” and of a “policy-oriented essence, which makes [it] local and contingent.”[83] Carefully inscribing relationships and families in the Code can show that ‘family matters’ are an integral part of private law in Quebec and that family law is not exceptional.[84] This section is about locating statuses coherently in the Code and allocating their effects (rights, duties, obligations, responsibilities, and powers).

Recoding the CCQ is further required, because principles now found in the Book on the Family are inconsistent with principles elsewhere in the Code and are overly reliant on a formal understanding of family ties. The Book on the Family bends rules to make them look like they are integrated in the edifice of the Code, but they do not respect basic civil law principles. For example, the family patrimony is not truly a patrimony and rules surrounding marriage contracts are inconsistent with general rules on obligations. Most importantly, the rules are not about actual relationships and their qualities, but about the requisite entry criteria to have a relationship legally recognized, regardless of the actual qualities and content of the relations.[85] This means that citizens in the exact same situation when it comes to the qualities and nature of their relationships are treated differently in private law, despite being similarly treated in other contexts.[86] Family law principles should be flexible and abstract enough to evolve with time, to adapt to new realities, and to be consistent with other fundamental principles found in the Civil Code of Québec. Even in the eighties, the members of the Committee on the Law of Persons and Family Law were aware of the risk of inconsistency in the Book on the Family.[87] Relationships— as opposed to just marriage, for example—should be better integrated in the Code, from elements that are so fundamental that they cannot be contracted out, to elements that can be the object of a contract, to limitations on ownership rights or claims/créances, and more.

A. Locating Status

In Quebec family law, statuses have consistently been triggered by formalities and by a formal account of how relationships can be integrated in the Civil Code. The law of persons is undeniably associated with the notion of status. A status entails certain effects a legal subject is not free to contract out of. However, status does not have to depend solely on the accomplishment of formalities, on contractual logic, or on an institution. All this, and more, could trigger a status. Nothing prevents a factual situation from triggering a status. A status—here, one of interdependency—could be triggered by the qualities of a relationship, since a civil status is the “[e]nsemble des qualités inhérentes à la personne, que la loi prend en considération pour y attacher des effets,”[88] or, “[d]ans une acception large, l’état de la personne s’entend de l’ensemble des qualités de la personne que la loi prend en considération pour y attacher des effets juridiques.”[89] Status is inherently about qualities. The relationship itself, and not its form, should grant the law capacity to regulate it.

This recoding does not claim to be exhaustive. It represents a starting point to launch a discussion as to how intimate and personal relationships of economic and emotional interdependency could be included in the Civil Code to provide abstraction, inclusivity, flexibility, and consistency. The best way to highlight the proposed modifications to the structure of the Code is through tables. When explanations are necessary, they can be found under the tables. Modifications are provided in italics.

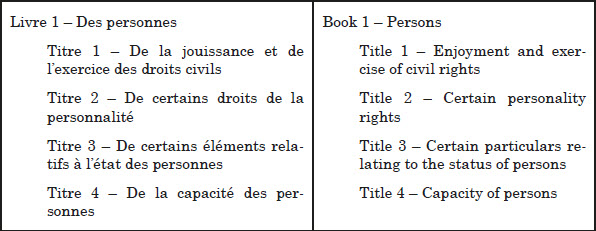

Figure 1

Nothing would change when it comes to the titles of the First Book of the Code, reproduced by figure 1. In terms of structure, it is logical to include interdependency statuses here, as it is the part of the Code concerned with the status of persons. Including family relations in the First Book is not a radical idea, as it would be consistent with what was done prior to the eighties in Quebec[90] and what is done today in the French Civil Code.[91]

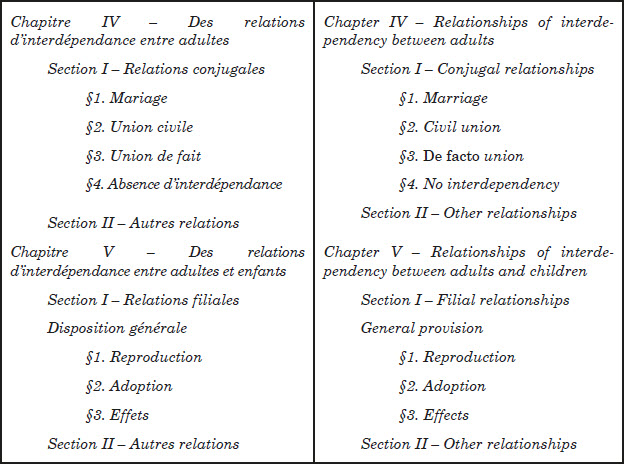

Modifications would take place in Title 3 of Book 1 and would look like this:

Figure 2

Except for the new chapters provided in italics, this is in line with the former structure of the Code. It is logical to include these relationships in the Book on Persons, as they include some elements which one cannot contract out of. These elements are both noncommercial and extrapatrimonial in nature, and are profoundly intertwined with the self, the legal subject, and the legal person. Moreover, the family is neither a legal entity nor a legal person, and it is therefore misleading to have a Book on the Family with legal consequences attached to ‘the family.’[92] This proposed structure makes it clear that the family is not a legal entity.

The breakdown of the two new chapters of Book 1 would look like this:

Figure 3

In Chapter IV, under Section I, the subsection on marriage would include the current articles about marriage and the solemnization of marriage, proof of marriage, nullity of marriage, and extrapatrimonial rights and duties of spouses. It would also include separation from bed and board. Similarly, the rules on the formation, effects, and dissolution of civil unions would be found under the second subsection. The inclusion of the institution of civil union in the Code should be questioned now that marriage is open to same and opposite sex couples and since the proposed framework would include de facto unions, but this is beyond the scope of this article.

The third subsection would provide a definition of de facto unions and would make clear that this kind of union is similar to marriage and civil unions, and thus triggers an interdependency status. The fourth subsection would contain the test explained earlier. It would provide for spouses whose conjugal unions are not relationships of economic and emotional interdependency to contest the interdependency status. The second section (Section II – Other relationships) would allow for adults in a relationship of economic and emotional interdependency that is not conjugal to claim interdependent status.

Chapter V, Relationships of Interdependency between Adults and Children, would open with a general provision about the equality of children regardless of their circumstances of birth, but it would not include a right to have one’s filiation established, as this can hardly be framed as a right and is not enforceable.[93] The rules explained in part I.B. of this article would be found under these subsections and would look like this:

Figure 4

The second subsection (see figure 3), on adoption, would mostly use the current rules, which were modified in 2017.[94]

The third subsection of Chapter V, Section 1 (see figure 3)—the section on the effects of filial relationships—would include the mandatory effect of filiation: maintenance. Maintenance does not need to be understood as an attribute of parental authority, and can instead be seen as a patrimonial effect of filiation. It could also arise without parental status. The second section of Chapter V would target other adult-child relationships and would allow claims for interdependency status. It would also include an article on how reproduction is a residual category. The rules about the act of birth found in Book 1 would need to be modified to make clear that there is no need for corroboration between the attestation of birth and the declaration of birth, and to anchor the act of birth in the declaration of birth for all parents.

The Book on Persons would contain three final chapters, two of which would be moved from the former Book on the Family, and one of which is already in the Book on Persons. Chapter VI would be on parental authority, Chapter VII on the obligation of support associated with interdependent statuses (which will be considered in greater detail in the next section), and the last chapter, Chapter VIII, “Register and Acts of Civil Status”, would remain unchanged but for the modifications to the articles on the act of birth.

B. Allocating Effects

While integrating relationships of economic and emotional interdependency in the Code would be a welcome change, their recognition must entail legal effects for the status to be meaningful. This subpart first allocates the effects of interdependency statuses and includes them in the current mechanisms found in the Code. To begin, mandatory effects are explored, and effects one can opt in or out of are described after. Second, this subpart considers the consequence of such an understanding on four accounts: consistency within the Code, the shift in the normative project of the regulation of intimate life, consistency with the law outside of the Code, and other practical and theoretical advantages.

Effects

In terms of recoding the effects, some would be found in the Book on Persons, making them mandatory. Mandatory effects would include, in addition to the extrapatrimonial rights and duties associated with interdependency statuses, the obligation of support, parental authority, prior claims on identified property (family patrimony), compensatory allowance, and restrictions to ownership rights or lease agreements (family residence). Other effects or legal mechanisms would be integrated in the book in which they belong. For example, the current effects of marriage or civil union contracts would become part of the Book on Obligations and the Title on Nominate Contracts. To be consistent, it should, at least, be renamed a conjugal contract.

The first group of mandatory effects of relationships of economic and emotional interdependency concern both parent-child and adult-child relationships. Parental authority would roughly remain untouched, but would be moved to the Book on Persons. It makes sense to have parental authority and tutorship in the same book, as they are, to a certain extent, two sides of the same coin. Maintenance, as mentioned above, should be seen as a mandatory effect of filiation. This would clarify that even if parental authority is withdrawn, maintenance obligations continue to exist.

While moving parental authority to the Book on Persons may seem questionable, it is justifiable when one analyzes the current articles on parental authority and its nature. The current Title on Parental Authority contains sixteen articles. These articles mostly concern extrapatrimonial elements of the relationship between a child and an adult. For example, articles 597, 598, and 602 provide for illustrations of the extrapatrimonial nature of parental authority. They read as follows:

Respect, in article 597 CCQ, is undoubtedly extrapatrimonial, as is the authority found in article 598 CCQ and the possibility to leave the domicile (art 602 CCQ). In addition, it is impossible to ‘opt out’ or contract out of parental authority. Such authority used to be found in the First Book of the CCLC, at a time when it was seen as a puissance paternelle. A puissance amounted to authority granted by the State to an individual so that this individual had powers over other human beings, children, or women. While it has changed today, it remains, in nature, extrapatrimonial and attached to the status of persons. It should be noted that a power is generally a prerogative used to act in the interest of another.[95] In terms of its nature, parental authority is about powers and duties.[96]

The second group of mandatory effects is related to relationships of economic and emotional interdependency between adults. As the proposed structure of the First Book shows, conjugal unions should now be comprised of both de jure and de facto unions. The definition of de facto spouse could be in line with definitions outside of the Code for consistency. The effects of marriage, civil union, and de facto union would be found in the First Book of the Code. This would include: rights and duties of spouses (art 392 CCQ), name (art 393 CCQ), moral and material direction [of the family] (art 394 CCQ),[97] choice of residence (art 395 CCQ), and contributions to the expenses [of the household] (art 396 CCQ). Article 397 CCQ, which provides that

would probably need to be included in the Book on Obligations or in the Title on the Common pledge of creditors (arts 2644 CCQ and ff). Articles 398 and 399 CCQ, concerned with the mandate or representation powers, fit nicely in the current chapter on the mandate, which is Chapter IX of the Second Title (nominate contracts) of the Fifth Book (obligations). Article 400 CCQ, discussing the possibility for spouses to apply to the court when they “disagree as to the exercise of their rights and the performance of their duties,” could be inserted in different parts of the Code, but the First Book could be good fit. Finally, the compensatory allowance rules should be integrated into the section on unjust enrichment.

When it comes to the family residence and the family patrimony, it is important to ask what exactly articles 401 to 426 CCQ are about and who they should apply to. Does their subject matter concern limitations to the right of ownership? Claims? Prior claims? Limitations to leases? The answer is likely all the above. First, the articles on the family residence limit the legal prerogatives of an owner concerning the family home and movable property serving for the use of the household. Specifically, it prevents one spouse from, “without the consent of the other, alienat[ing], hypothecat[ing] or remov[ing] from the family residence the movable property serving for the use of the household.”[98] It would be logical to include these provisions in the Book on Property. There is also an article preventing subleasing or lease termination without the consent of the other spouse.[99] This provision could be integrated within the law of obligations, in the Title on Nominate Contracts and the section about special rules for leases of dwellings.

Second, scholars in Quebec have critiqued the nature and qualification of the family patrimony. While it is essential to balance economic disadvantages at the end of a conjugal relationship, it should not be done through the family patrimony in its current form, because this device does not respect basic civilian principles related to the law of persons, the law of obligations, debtor/creditor law, and property law. The articles on the family patrimony specify how to determine the value of a group of assets, assumed to be common to most couples, and share them in value “regardless of which [of the spouses] holds a right of ownership.”[100] For Ernest Caparros, the family patrimony was a créance égalisatrice, a claim at the end of the marriage or a matrimonial regime; specifically, an imperative secondary regime (Régime matrimonial légal impératif).[101] He was theoretically opposed to the family patrimony and qualified it as a “virus décodificateur.”[102] He wrote that “une connaissance et une compréhension insuffisantes de notre ordonnancement juridique codifié permettrait d’expliquer que le législateur ait senti le besoin de créer une nouvelle section dans ce livre II du Code civil du Québec.”[103] If the family patrimony is a claim, it should be codified accordingly. If it is a matrimonial regime, it should be codified as such and be found in the Book on Obligations. While one can be ideologically opposed to Caparros, his legal analyses of the nature and qualification of the family patrimony are accurate. It demonstrates an incredible richness for civil law to be abstract, flexible, and coherent enough so that conservative (Caparros’, for example) and liberal views (my own) of the family can be found in the analysis of the same legal devices.

The last mandatory effects are obligations of support. The obligation of support generally targets both adult-child and adult-adult relationships. I suggest extending it to all relationships of economic and emotional interdependency. The possibility of claiming an obligation of support would thus be available to all, though not everyone would be entitled to support. Support would remain subject to guidelines when it comes to children and would rely on a means and needs analysis for other relationships. It would be moved to the First Book, the Book on Persons. While the nature of the obligation of support tends to be under-documented and under-analyzed in civil law—especially since the new Code came into force—Michel Tétrault writes, “[l]’obligation alimentaire est l’expression du concept d’interdépendance et de solidarité entre certains membres de la famille.”[104] Now that the contours of the family in law have expanded, and since this work proposes to move family law’s basis toward relationships of interdependency, what makes an obligation alimentary? Ethel Groffier, citing French author Jean Pélissier, suggested in 1969, “[c]e n’est pas l’origine familiale ou non d’une obligation qui donne à l’obligation un caractère alimentaire. C’est sa destination. Sont alimentaires toutes les prestations qui ont pour but d’assurer à une personne besogneuse des moyens d’existence.”[105] Obligations of support sustain individuals’ situations of interdependency. They originate from relationships based on solidarité and interdépendance. There are some conceptual hurdles to the analysis of support obligations originating from France and published before divorce was possible. Support obligations used to materialize in a different context with a different scope.[106] The nature of support obligations is complex, but nothing prevents them from attaching to interdependency status when and if need be. Support obligations are attached to the person. They are rooted in a specific type of relationship. The form of these relationships should matter less (now) than their content (proposed framework). While they raise policy and social concerns, from a private law perspective, it is sound to attach them to relationships of economic and emotional interdependency. Support obligations should be seen as something one cannot contract out of, at least not before or during the relationship. This mandatory effect of interdependency statuses should be located in the First Book of the Code.