Résumés

Abstract

This paper examines the impact of investor sentiment on merger outcomes, in particular on bid premiums. Using international data from 54 countries between 2000 and 2021, our results show that investor sentiment has a positive effect on bid premiums. Our findings also suggest that the association between investor sentiment and bid premiums is more pronounced in countries culturally prone to herd-like behavior and overreaction. However, this effect is reduced both in countries with highly efficient institutions and in serial deals. Our results are robust to several checks.

Keywords:

- Investor sentiment,

- M&A,

- bid premium,

- cultural and institutional factors,

- serial acquisitions

Résumé

Cet article étudie l’impact du sentiment des investisseurs sur les primes d’acquisition payées lors des opérations de fusions et acquisitions (F&As). Notre étude porte sur un échantillon international qui couvre les opérations initiées dans 54 pays sur la période 2000-2021. Nous trouvons que le sentiment des investisseurs du pays de l’acquéreur influence positivement la prime d’acquisition. L’effet du sentiment de l’investisseur sur la prime d’acquisition est plus prononcé dans les pays les plus culturellement enclins à des comportements de sur-réaction ou grégaires. Cet effet se révèle plus faible dans les pays qui se caractérisent par un cadre institutionnel efficient, et pour les entreprises ayant déjà effectué des acquisitions successives. Nos résultats restent stables à l’utilisation de plusieurs tests de robustesse.

Mots-clés :

- sentiment des investisseurs,

- F&A,

- prime d’acquisition,

- facteurs institutionnels et culturels,

- acquisitions successives

Resumen

Este artículo examina el impacto del sentimiento de los inversores en los resultados de fusiones, en particular en las primas de oferta. Utilizando datos internacionales de 54 países entre 2000 y 2021, nuestros resultados muestran que el sentimiento de los inversores tiene un efecto positivo en las primas de oferta. Nuestros hallazgos también sugieren que la asociación entre el sentimiento de los inversores y las primas de oferta es más pronunciada en países culturalmente propensos a comportamientos gregarios y a la sobrerreacción. Sin embargo, este efecto se reduce tanto en países con instituciones altamente eficientes como en acuerdos sucesivos. Nuestros resultados se mantienen estables tras varias pruebas de robustez.

Palabras clave:

- sentimiento de los inversores,

- fusiones y adquisiciones,

- prima de adquisición,

- factores institucionales y culturales,

- adquisiciones en serie

Corps de l’article

There is extensive literature discussing the determinants of the premium paid to acquire potential targets (Hayward and Hambrick, 1997; Eckbo, 2009; Jost et al., 2022). If investors are rational, in line with the expectations of the efficient markets hypothesis (Fama, 1970), the bid premium should reflect the value of potential synergies. Those Synergies may arise in M&A transactions for different raisons such as the gain from the increased efficiency in the form of improved target asset utilization, management efficiency or from wealth transfers as a result of the business combination. This paper relaxes the view of strict investor rationality and consider that investors’ cognitive biases can influence the bid premium. Investor sentiment is expected to influence investor perception of potential synergies and risks involved in the acquisition, leading to a non-rational component of the bid premium (Danbolt et al., 2015). Almost no scholarly attention has been devoted to a direct accurate proxy of individual investor sentiment in the context of M&A. This article contributes to the existing literature by empirically examining the effect of investor sentiment, proxied by the non-rational part of the consumer confidence index (CCI), on bid premium using an international sample of M&A data.

The offer price is often affected by optimistic views and beliefs about the expected synergies of the deal. Individuals are indeed prone to sentiment and make decisions based on non-rational inputs. Sentiment can be viewed as non-rational beliefs that are not consistent with a fundamental approach. Evidence of the influence of sentiment on the financial markets has been gathered (see for instance, in the context of the stock market: Baker and Wurgler, 2007; for bond markets: Piñeiro-Chousa et al., 2021; for crypto-assets: López-Cabarcos et al., 2021). Thus, sentiment has something to do with the pricing of securities and the valuation of companies. Danso et al. (2019) find that sentiment influences firms’ investment decisions in the United States. They underline that there is a large literature providing evidence of the effect of behavioral biases on investing and financing decisions made by CEOs. They show, using a survey-based measure of sentiment, namely the Michigan Consumer Confidence Index, that sentiment has a positive effect on firms’ capital expenditures.

This is of particular importance in the context of M&A, as the premium paid may be influenced by investor sentiment. Some form of mispricing the initial bid price may impede the acquirer’s future performance. Some theoretical papers study the issue of investor sentiment in the context of M&A (Shleifer and Vishny, 2003; Rhodes-Kropf and Viswanathan, 2004). The studies generally use market valuation as a proxy for investor sentiment and do not explicitly address the direct influence of sentiment on the premium paid by the bidder. Bouwman et al. (2009) examine the performance of acquirers in high-valuation markets and low-valuation markets. They find that acquisitions announced in a booming market generate high short-run performance but underperform in the long run. Baker et al. (2009) find that foreign direct investment, which often consists of cross-border M&A, is positively associated with the current aggregate of market-to book ratio of the home country’s stock market (i.e. high investor sentiment) and is inversely related to subsequent market returns.

Otherwise, some studies suggest that media news contains information relevant to M&A performance (Yang et al., 2019; Liao et al., 2021). These studies examine the effect of financial media sentiment on deal premium paid to target firm and find conflicting results. Liao et al. (2021) show that acquirers with high media optimism tend to pay a higher premium to target firms. They argue that those acquirers either have better growth opportunities or can pay for the target with more overvalued shares. However, Yang et al. (2019) find the opposite result showing that a more pessimistic media attitude leads to higher bid premiums. They argue that when the shareholders of target firms are influenced by pessimistic news, acquirers have to boost their bid prices to compensate them. We further develop those findings by relying on a robust; longstanding and established measure of investor sentiment based on the consumer confidence index (Lemmon and Portniaguina, 2006; Danso et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021). This index has the advantages of being common to many countries allowing for international comparison and, having a long track record that allows testing our sentiment hypothesis over a long period of time.

The heterogeneity and diversity of countries of our sample are particularly propitious to an extension of the previous analyses and allow for investigation of the influence of institutional factors and national culture on the relationship between investor sentiment and bid premium. Culture and institutions tend to moderate the impact of investor sentiment on financial behaviors (La porta et al., 1998. Schmeling, 2009; Wang et al., 2021). We provide evidence of the moderating effects of national culture and of market integrity on the association between investor sentiment and the bid premium.

Our results show that investor sentiment exerts a strong and positive effect on M&A premium, i.e., the higher the sentiment surrounding the acquirer, the higher the premium paid by the bidder. In line with the literature, we find that the effect of the sentiment is higher in countries with a culture prone to overreaction and herding. Moreover, we show that the effect of sentiment is exacerbated in countries with low market integrity and weak institutions. To extend our behavioral story, we examine serial bidding. If CEOs behave in the same way as retail or non-financially educated investors, we should observe no learning effect, i.e., premiums paid by serial bidders inflate with both investor sentiment and transactions. If executives are learning from their experience, the impact of sentiment should be smaller over time and transactions. Our results show that managers benefit from their experience and are less influenced by investor sentiment as they conduct M&A transactions.

Our paper contributes to the literature in several ways. First, our paper contributes to the emerging literature on the determinants of bid premiums (Eckbo, 2009; Jost et al., 2022). We supplement these studies by identifying a new determinant of the bid premium in M&A transactions consistent with a behavioral approach to financing decisions. This adds to the behavioral finance literature that examines the impact of investor sentiment on firms’ decisions (Bergman and Roychowdhury, 2008; Liao et al., 2021). Second, the introduction of culture and institutions as moderators of the impact of the investor sentiment on premiums provides a better understanding of corporate decisions. Third, our paper contributes to the literature on CEO behavior (Huang et al., 2022; Aktas et al., 2011) by showing that while CEOs are subject to investor sentiment, a learning behavior counteracts this tendency to be led by instincts. Last, our study expands the growing literature examining the effect of country-level factors, such as trust (Ahern et al., 2015), culture (Stahl and Voigt, 2008), leadership style (Rouine, 2018) and economic policy uncertainty (Nguyen and Phan, 2017), on bidder’s decisions making.

Our paper is structured as follows. Section 2 develops our hypotheses. Section 3 details our data and our variables. Section 4 presents our empirical strategy. Section 5 details and discusses our results. Section 6 provides some robustness checks. The last section concludes.

Hypotheses development

Bid premium and investor sentiment

M&A are one of the most important decisions companies have to make. As Hayward and Hambrick (1997) point out, a large part of the corporate finance literature offers rational explanations for these decisions (poor target company management, empire building, and synergies). Another strand of the literature, based on the concept of hubris (exaggerated pride), has emerged by Roll (1986). He argues that firms prone to hubris pay too much for targets because managers overestimate their own ability to realize value from non-organic growth operations.

Along similar lines, but from a behavioral perspective, Malmendier and Tate (2005, 2008) show that CEOs’ behavioral characteristics influence investment decisions in the context of M&A. Baker and Wurgler (2007) define investor sentiment as “a belief about future cash flows and investment risks that is not justified by the facts at hand.” Jiang et al. (2019) argue that CEOs’ decisions may be guided by their unrealistic beliefs about fundamentals, i.e., their sentiment. Dicks and Fulghieri (2021) develop a theoretical model that predicts a positive relationship between investor sentiment and firm valuations. Thus, CEO can be influenced by the general investor sentiment surrounding their decisions. Those authors apprehend sentiment as the “investor attitude toward investment in risky assets.” Conducting an M&A transaction is an investment in a risky asset. This line of reasoning suggests that investor sentiment can play a role in understanding M&A activity.

Huang et al. (2022) show that investor sentiment influences the decision to exercise stock options and the decision to engage in M&A activity. CEO exercise options more quickly during periods of high sentiment. They find that firms engage more often in M&A transactions when sentiment is high. Danbolt et al. (2015) highlight a positive (negative) market reaction to M&A announcements during periods characterized by high optimism (pessimism). The authors argue that investor sentiment influences their perception of the potential synergies and risks of M&A. During periods of high enthusiasm, investors tend to overestimate the positive benefits of M&A and underestimate the risks associated with this type of transaction. We can reasonably expect CEOs to propose higher bids during periods of high sentiment. This leads us to formulate the following hypothesis:

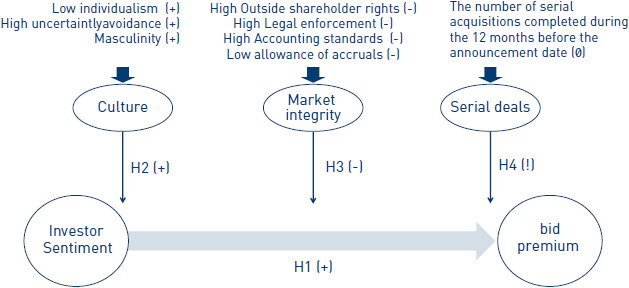

H1: The bid premium is positively associated with investor sentiment

National culture

Academic research did not deeply explore the role of national culture in determining the financial behavior of individuals. The pioneer model of the link between national culture and financial markets is that of Hofstede (1980). This author defines culture as “the collective programming of the mind distinguishing the members of one group or category of people from others”. Hofstede (2001) argues that culture can be captured by six dimensions: power distance, individualism, uncertainty avoidance, masculinity, long-term orientation and indulgence. While there are critiques of Hofstede’s framework (McSweeney, 2002; Ailon, 2008), it is the most comprehensive approach with national culture, as evidenced by its cumulative impact on research generally and in finance specifically. Reuter (2011), in his review of the literature on culture and finance, finds that over 80% (24/29) of the articles considering a dimensional approach to culture in finance rely on the framework developed by Hofstede. Similarly, Beugelsdijk et al. (2015) point out that Hofstede’s approach dominates quantitative research in strategic management and that Hofstede’s individual dimension scores are not outdated and are rather stable over time. Furthermore, Kaasa (2021) finds high correlations between Hofstede’s cultural items and other items developed by other authors (Schwartz,1994; Inglehart, 1997). This leads us to use Hofstede’s approach in this work. In the financial literature, three dimensions are particularly retained in empirical studies working on the link between culture and financial markets: individualism, uncertainty avoidance and masculinity (Chui et al., 2010; Schmeling, 2009; Lucey and Zhang, 2010). Data on cultural dimensions are collected from Hofstede et al. (2001)[1].

Individualism determines the extent to which the identity is defined by personal choices or by the collective. In countries where the degree of individualism is high, people care more about themselves than others. On the contrary, countries with a high level of collectivism relate to societies where individuals are well integrated into a strong, cohesive group and in which consensus is the rule. According to Hofstede (1980), a high level of collectivism is synonymous with a tendency to herd behavior. This herding behavior can be interpreted as the result of correlated behavioral tendencies between individuals. The actions of noise traders are correlated because they replicate the actions of other traders based on overly optimistic or pessimistic expectations. This propensity to invest with the group is exactly what is supposed to guide the relationship between investor sentiment and stock return. As a result, we can expect that the impact of investor sentiment on bid premium will be weaker in countries where the degree of individualism is high.

The uncertainty avoidance represents the most appropriate cultural dimension to justify a behavioral explanation of stock returns (Lucey and Zhang, 2010). According to Hofstede (1980), uncertainty avoidance can be defined by the degree to which members of a culture can react to equivocal, unknown and unexpected situations. In countries with higher uncertainty avoidance index, individuals prefer predictable situations, are wary of risky situations and are more emotional than in countries with lower uncertainty avoidance index. The uncertainty avoidance is thus used in the financial literature as a proxy to the tendency of individuals to overreact. As a result, we can expect that the impact of investor sentiment on bid premium will be stronger in countries with high degree of uncertainty avoidance.

Masculinity refers to a preference for assertiveness, heroism and material rewards for success. Psychological studies show that in different fields, men tend to overestimate their real abilities and have unwarranted certainty in the accuracy of their beliefs compared to women. In finance field, overconfident men overreact when investing in stock markets (Daniel et al., 2001). Eilnaz et al. (2020) point out masculine culture and masculinity are linked to overconfidence. Picone et al. (2014) notice that hubris and overconfidence are used as synonymous in the management literature. A masculine culture could increase both overconfidence and hubris of CEO and thus enhance the effect of investor sentiment on their decision. Thus, we can except that the impact of investor sentiment on bid premium is stronger in countries where the degree of masculinity is high.

In this context, several studies find strong influence of investor sentiment on stock returns in countries that are more likely to demonstrate herding behavior or overreaction (Schmeling, 2009; Wang et al., 2021). Similar to these studies, we use individualism, uncertainty avoidance, and masculinity as proxies for herding behavior and for the tendency of investors to overreact across countries. We assume that behavioral biases are proxied by low levels of individualism, high uncertainty avoidance and masculinity. These findings lead to the following hypothesis:

H2: The impact of investor sentiment on deal premium is stronger when the acquirer is based in countries which are culturally prone to behavioral biases.

Market integrity

Market integrity means that financial markets with a higher level of institutional sophistication are characterized by a better flow of information and are consequently more efficient. The efficiency of an economy and capital markets is based on how well the legal system protects outside investors. The market integrity indicators used in our study can be found in La porta et al. (1998) and include: outside investor rights, legal enforcement and accounting standards index. Outside investors’ rights are proxied by the anti-director rights index which captures how strongly the legal system favors minority shareholders over dominant shareholders. Legal enforcement is measured by two legal variables: the efficiency of the judicial system and the corruption index. The accounting standards index measures the quality of the financial reporting across countries. Our last market integrity indicator is similar to Hung’s (2001) index. A high index value in a particular country indicates that higher use of accruals accounting is permitted. This indicator assesses the extent of accruals accounting in various countries by evaluating the extent to which the accounting systems depart from a cash method. Hung (2001) show that higher use of accruals accounting decreases the quality of accounting information and the efficiency of capital markets.

McLean et al. (2012) find that stronger investor protection leads to accurate stock prices and efficient investment. In line with this finding, Wang et al. (2021) expect that high-quality institutions will help improve information flow and make stock markets more efficient. Thus, investor sentiment should have a lower impact on stock prices in countries with highly efficient institutions and higher market integrity. The reason behind this is that a high market integrity helps rational investors to offset the effects of noise trader’s sentiment. The empirical results of Wang et al. (2021) and Schmeling (2009) support this view.

In our study, we use a cross-section of countries to determine if there is evidence that impact of investor sentiment on bid premium is related to the level of development of financial institutions and the level of sophistication of stock markets. We argue that high market integrity is identified by strong outside shareholder rights, a high legal enforcement, a high quality of accounting standards and low allowance of accruals. Thus, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H3: The impact of investor sentiment on deal premium is weaker when the acquirer is based in countries with high market integrity.

Serial deals

Serial bidding is frequent in M&A transactions. Through their internationalization strategy, bidders mostly adopt serial corporate acquisition programs to seize new markets, to obtain new skillsets and competitive technologies, and to keep and strength their market position in the world. However, the imperative to select appropriate targets and then execute the relevant transactions successfully is far greater in a serial acquisition strategy context (Smit and Moraitis, 2010). Execution of a serial acquisition strategy is vulnerable to the biases of managers’ judgment manifested in their strategy and how they perceive risks and losses. Moreover, serial deals lead to empire building where overconfident managers overpay for targets (Malmendier and Tate, 2008). Following hypothesis H1, we expect that the higher the investor sentiment surrounding the serial acquirer, the higher the premium paid. However, it can be argued that serial auctions are special events that conduct to the emergence of a learning effect. Aktas et al. (2011) develop this view and propose a hypothesis that serial acquirers benefit from their experience and tend to adjust their bids according to market expectations without being influenced by investor sentiment. Aktas et al. (2013) further develop their model and provide evidence that the time elapsed between successive deal announcements demonstrates a learning behavior. They argue that serial acquisitions allow even hubristic CEOs to learn by experience and regulate their valuation process. Thus far, the ability of investors to learn from their past experience is still a matter of debate in the literature. Chang et al. (2015), in the context of Taiwan’s options and futures markets, find that investors do not learn by doing and that investor sentiment exacerbates mistakes. Chiang et al. (2011), in the context of IPOs, document that investors’ abilities decline with experience. However, in the M&A context, firms develop knowledge and expertise regarding target selection, valuation assessment, negotiation strategy, and integration (Collins et al., 2009). Using cross-border mergers, Pandey et al. (2021) provide evidence of acquirer learning in acquisitions of private and public targets from less competitive takeover markets. These elements lead us to the following nondirectionally hypothesis:

H4: The impact of investor sentiment on deal premium is associated with serial acquirers.

Figure 1 in Appendix 1 summarizes the hypotheses developed in this article.

Figure 1

Conceptual model

Data and variables

M&A data

Our sample consists of all announced M&A between 2000 and 2021. Our initial sample is obtained from Thomson SDC. Following previous studies, we include only significant deals (valued at U.S. $1 million or more). We place no restrictions on the public status of the target or the bidder. We identify 369,727 deals during the period 2000–2021. Investor sentiment data come from various sources (national banks, international organizations, etc.)[2] while the M&A premiums are obtained from SDC. Firm-year observations with missing data are excluded from our sample. Merging our M&A data with investor sentiment data yields a final sample of 44,697 M&A transactions released by 25,752 firms in 54 countries for which M&A premium data are available in SDC.

Bid premiums

The main dependent variable is the M&A premium which is defined as the percentage increase (decrease if negative) of the bid price over the closing market price four weeks prior to the announcement, [(offer price - previous 4 weeks’ closing market price)/previous 4 weeks’ closing market price] × 100% (Surendranath et al., 2016). 28 days before the announcement date is a relevant window to avoid the informational leakage, the influence of run-up effect on the stock price of the target prior to the announcement.

Investor sentiment

Investor sentiment can be defined as a belief about future cash flows and investment risks that is not warranted by fundamentals (Baker and Wurgler, 2006; Lemmon and Portniaguina, 2006). In the literature, several studies have attempted to quantify investor sentiment[3]. Nowadays, a universally accepted measure of investor sentiment has not yet been identified. Given our international setting, we choose the consumer confidence index that offers significant advantages over others sentiment indexes. First, the financial literature highlights a positive and significant relationship between consumer confidence and investor sentiment. Qiu and Welch (2006), for example, show that the alternative candidate, consumer confidence index, is a reasonable proxy of investor sentiment. They find that consumer confidence changes correlate strongly with changes in the direct UBS/Gallup investor sentiment survey data. They conclude that (p.26) “Consumer Confidence can be validated as a proxy for investor sentiment.” Second, the consumer confidence index is a direct accurate proxy of individual investor sentiment because it is based on a monthly survey of a large number of households about their current and expected financial situations and their beliefs about the economy. Because the consumer confidence index captures individual beliefs, it reflects the philosophy of behavioral finance by including the opinions of imperfect people who have social, cognitive and emotional biases (Shleifer, 2000). Third, our selection is the result of the well documented established relationship between the consumer confidence index and the equity market. Many studies use the consumer confidence index as the main proxy of investor sentiment and show that this sentiment indicator seizes stock market aspects not already contained in rational macroeconomic indicators (Lemmon and Portniaguina, 2006; Antoniou et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2021). Fourth, the data on consumer confidence index are available for several international markets for long and regular periods of time, including the emerging market, giving an international dimension to the validity of our results. Finally, and most importantly, the nature of this paper examining international M&A transactions including both developed and emerging markets requires consistency across all sample markets. Thus, the investor sentiment measure used in an international study should be applied in all countries of our sample. The consumer confidence index offers such wide availability in all 54 countries of our study. Form this view, several studies have used the consumer confidence index in international setting as a relevant proxy for investor sentiment (Schmeling, 2009; Wang et al. 2021).

The raw consumer confidence index encompasses a psychological component related to sentiment and a rational component related to economic fundamentals. As noted by several studies, consumer confidence index varies in part for entirely rational reasons related to the macroeconomic conditions. Isolating sentiment consists precisely of identifying investors’ optimism (pessimism) although there is not a good (bad) valid economic reason for being so. In order to properly measure sentiment, we estimate equation (1) and take the residuals (εj,t) from it as a measure of investor sentiment.

CCIj,t is the consumer confidence index for each country j at time t, αj is the constant, and ![]() are the parameters to be estimated.

are the parameters to be estimated. ![]() is the set of fundamental variables representing rational expectations based

on risk factors of every country. These variables include growth of industrial production,

inflation, term spread, and growth in durable, nondurable, and services consumption. The

fitted values of equation (1) capture the rational component, and the residual

(εj,t) (captures the

psychological component (Sentj,t = εj,t). To ensure comparability across countries, CCI and fundamental

variables were standardized in each country with zero expectation and unit

variance.

is the set of fundamental variables representing rational expectations based

on risk factors of every country. These variables include growth of industrial production,

inflation, term spread, and growth in durable, nondurable, and services consumption. The

fitted values of equation (1) capture the rational component, and the residual

(εj,t) (captures the

psychological component (Sentj,t = εj,t). To ensure comparability across countries, CCI and fundamental

variables were standardized in each country with zero expectation and unit

variance.

Bidder and deal characteristics

The vector of control variables includes the following bidder and deal characteristics. Acquirer_size measures the natural logarithm of the acquirer’s total assets the fiscal year before the deal announcement. Managers of large firms might be more prone to overconfidence; thus, larger acquirers pay larger premiums (Moeller et al., 2004). Relsize is the relative size of the target. This variable is measured by the ratio of deal value divided by the acquirer’s total assets the fiscal year before the deal announcement. The smaller the target, the higher the offer premium (Betton et al., 2008). Acquirer_profitability is the acquirer’s return on assets over the last 12 months. The performance of acquirers and targets does not seem to have a significant effect on the premium (Mpasinas, 2007). Acquirer_leverage is the ratio of the acquirer’s total debt to total assets. Highly leveraged bidders are less likely to engage in negative net present value projects and are less likely to overpay in acquisitions (Black, 1989). Acquirer _public is a dummy variable that equals 1 if the acquirer firm is a public company and 0 otherwise. Public target shareholders receive higher premiums when the acquirer is a public firm rather than a private equity firm (Bargeron et al., 2008). Toehold corresponds to the percentage of equity of the target held by the bidder firm before the announcement. Simonyan (2014) shows that holding a substantial proportion of shares in the target prior to the deal provides the bidder with substantial control. Thereby, the bidder firm may induce target firm shareholders to accept a lower premium. Relatedness shows the effect of activity relatedness of the acquirer and the target on premium. According to Bae et al. (2002), unrelated deals are sometimes motivated by private benefits enhancing the amount of premiums. However, premiums are more associated with related acquisitions due to higher synergies. Cash is used to control the method of payment. A dummy variable equals 1 if the acquisition is entirely paid in cash and 0 otherwise. Simonyan (2014) reported that cash-offers are associated with large premiums. Number_bidders is the number of entities (including the acquirer) bidding for the target. Competition in the takeover market can increase the amount of premiums. Therefore, this variable can control for the effect of the winner’s curse on premiums. The winning bid premium overstates the value of the expected takeover gain (Varaiya, 1988). Cross-border is a dummy variable that is equal to one whether target’s and bidder’s nations differ. According to the hypothesis that idiosyncratic synergies for foreign acquirers exist, cross-border transactions offer higher premiums (Harris and Ravenscraft, 1991). Hostile is a dummy variable that equals 1 if the bid is classified as unsolicited and 0 otherwise. Control contests are likely to drive up premiums, thus, hostile targets have the highest premiums (Eckbo, 2009). Tender_offer is a dummy variable that equals 1 if the acquisition technique is a tender offer and 0 otherwise. Tender offers are more costly than mergers or other types of acquisitions. Premiums will then be higher in tender offers than in mergers (Offenberg et al., 2015). M&A waves is a dummy variable that equals 1 if the bid is announced during the periods 1985–1989, 1993–2000, 2002–2007 and 0 otherwise. During M&A waves, managers displayed less over-optimism and offer significantly lower premiums (Alexandridis et al., 2012). Appendix 2 presents the definition of the variables used in this study and their expected effect on bid premium.

Empirical strategy

There is wide literature (e.g., Eckbo, 2009; Aktas et al., 2009) discussing the relation of acquirer- and deal-specific characteristics with deal premium. To assess the effect of investor sentiment on premium, we run regression of the bid premium on the investor sentiment measure. Specifically, we employ the following econometric specification:

Where is the premiumi,t for deal i at time t. Bidder and deal characteristics’ control variables were discussed in the previous subsection. We also include, as a control variable, the annual real GDP rate in the regression. We use lagged explanatory variables to mitigate the endogeneity problem. A country’s M&A market is impacted by the legal business environment for investors (Ciobanu, 2015). Therefore, we also controlled for country, year and industry fixed effects. υC, υI, and υt are respectively the country fixed effect, industry fixed effect and the time fixed effect. Finally, we computed standard errors clustered by firm because standard errors may be underestimated in panel data sets.

Summary statistics and empirical results

Descriptive statistics

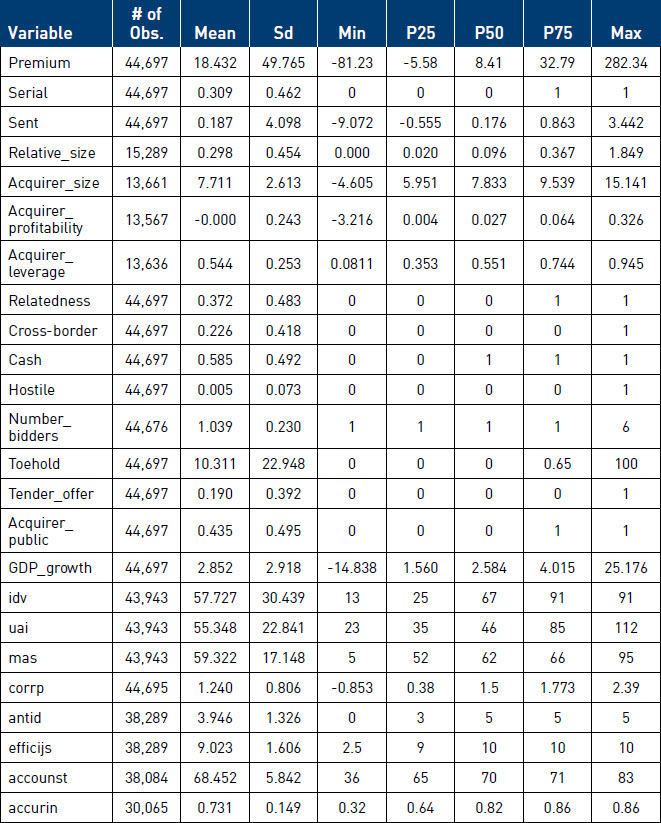

Table 1 reports the descriptive statistics for all the variables used in our study. The bid premium averages 18.432%. The average investor sentiment is equal to 0.187 with a standard deviation of 4.098, where the range is from -9.072 to 3.442. This suggests that the investor sentiment for each bidder’s country varies from one to another and some countries may have lower consumer confidence. Table 1 also provides additional information about M&A deals (37.2% of the firms are in the same industry, 22.6% of the deals are cross-border, more than half of the deals (58.5%) are all-cash offers, 30.9% of acquirers are serial bidders and 5% of the deals are hostile). The average bidder size is 7.711, which is about 2232.7 million USD. The average leverage ratio of sample firms is 0.544, with a minimum ratio of 0.0811 and a maximum ratio of 0.945 during the sample period.

Table 2 presents the distribution of the average deal value and average premium during the sample period. This table shows that global M&A activity has increased substantially around the world and firms expand internationally through non-organic growth operations. As reported in this table, the aggregate deal value decreased dramatically after the global financial crisis of 2008 from an aggregated dollar value of 1,005.83 million in 2006 to an aggregated dollar value of 234.85 million in 2009, before increasing again in 2014. M&A activity reached its highest number of deals (3,112 M&As) in 2009 with the lowest aggregate volume of $234.85 million. The financial crisis has significantly altered the global M&A market, where a significant number of M&As involving financially distressed firms are carried out. The highest average premium is about 30.21% observed during the internet bubble of 2000.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics

This table summarizes the descriptive statistics of the variables used in our empirical analysis. Premium is winsorized at the 1% level. Variables are defined in Appendix 2.

Table 2

Summary statistics by year

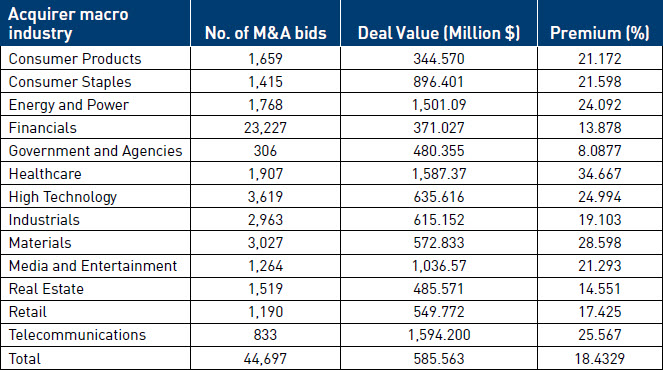

Table 3 illustrates the distribution of M&A premiums by acquirer macro industry. Among them, the healthcare and materials industries have the highest bid premiums. Finally, table 4 provides the distribution of bid premiums across 54 countries. These countries are classified by geographic zone and from the highest level to the lowest level of investor sentiment. Amongst these countries, Colombia, Argentina, Ireland, and Canada offer the highest premiums.

Table 3

Summary statistics by acquirer macro industry

This table provides the number of observations, average deal value, and average premium per acquirer macro industry.

Table 4

Summary statistics by acquirer nation

This table provides the number of observations, average deal value, and average premium per acquirer nation.

Multivariate tests

Baseline regression analysis

To examine the effect of investor sentiment on deal premiums in an international setting, we run an OLS panel regression by including the bid premium as our dependent variable and the investor sentiment measure as our independent variable. The results of this first regression are reported in Table 5.

The results in column 1 are consistent with our first hypothesis and show that investor sentiment has a positive and statistically significant impact on bid premiums. As suggested by Dicks and Fulghieri (2021), market sentiment influences the firm’s valuation and investment decisions. During high sentiment periods, CEOs incorporate the expectation of future profitability into their strategic decisions (Danso et al., 2019). Following this reasoning, CEOs are prone to hubris, and therefore they tend to overpay for a potential target because they overestimate the long-term growth of this investment (Roll, 1986). In terms of economic significance, a one standard deviation increase in sentiment is associated with an increase of about 2% in deal premiums.

In model 2, we include only control variables. The coefficients associated with Acquirer_size, Acquirer_leverage, Hostile, Cross-border, Tender_offer and GDP_growth are significant. According to the previous studies, large acquirers use to pay high premiums (Moeller et al., 2004); high levels of debt discourage acquirers to pay excessive amount of premiums (Black, 1989); and Cross border deals (Harris and Ravenscraft, 1991), hostile takeovers (Eckbo, 2009) and tender offers (Offenberg et al., 2015) enhance the bid premium.

In model 3, we also include the Sent variable, and we note that the significance of the control variables is not affected by the inclusion of our variable of interest. Similarly, we find that Sent variable remains highly significant and that the explanatory power of the model increases to 24%, representing a 0.178-point improvement in the R² adjusted. This last model shows that, after controlling for several variables, the acquirer country’s investor sentiment still has a significant and positive effect on the deal premium. In unreported tests, we use other measures of the bid premium (1-day premium; 1-week premium) and the results remain the same.

Overall, our evidence supports the hubris hypothesis (H1). This effect is economically significant. Influenced by investor sentiment in their country, bidders are more likely to make non-rational decisions by overpaying for the target firm. Estimates show that during periods of high investor sentiment, CEOs of bidder firms are more optimistic about creating synergies and, therefore, tend to overvalue the target firm by paying a high premium. They are willing to pay high premiums to complete deals in periods characterized by excessive investor euphoria. Our results are in line with previous studies that argue that investor sentiment proxied by the non-rational part of CCI affects the firm’s strategic decisions and policies (Bergman and Roychowdhury, 2008). We confirm that investor sentiment is a real determinant of target selection process which can play a crucial role in M&A synergies and risks valuation (Bouwman et al., 2009; Danbolt et al., 2015).

Table 5

Effect of Investor Sentiment on the Deal Premium

Cultural and institutional factors

To test the moderating effects of culture or market integrity on the association between investor sentiment and bid premium, a new model is estimated including the variable investor sentiment, the moderating variable (culture or market integrity), the control variables and the interaction variable (culture variable × Sent variable or market integrity variable × Sent variable).

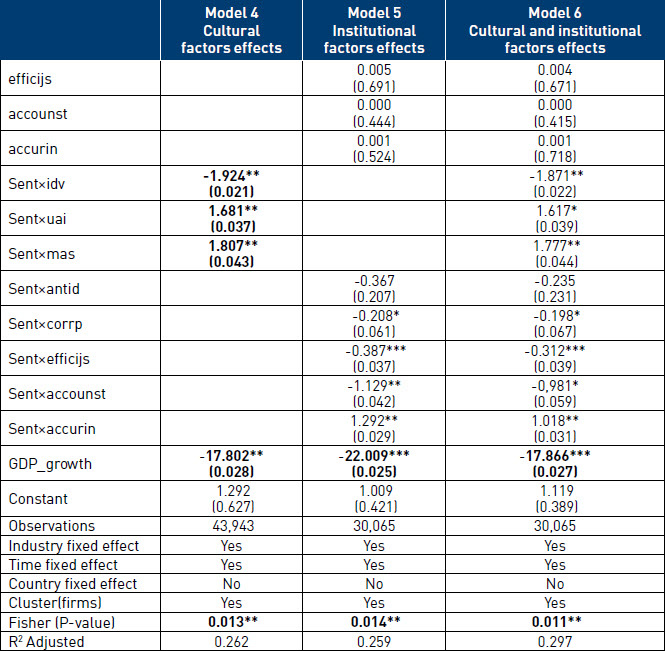

Table 6

The moderating role of institutional and cultural factors

This table presents the result of estimation of the fixed-effects model regression (sectors and years). The dependent variable (Premium) is the deal premium in percentage. All independent variables are defined in Appendix 2. Model 4 is used to test the moderating role of the cultural factors. Model 5 is used to test the moderating role of institutional factors whereas model 6 includes both the cultural and institutional factors. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively, computed from standard errors that are clustered at the firm level.

Table 6 presents the regression results incorporating the cultural and institutional dimensions. Model 4 focuses on cultural factors such as collectivism (vs. individualism), uncertainty, and masculinity. These three dimensions significantly accentuate the positive effect of the Sent variable on premiums (see coefficients of interaction terms). This confirms H2. The effect of investor sentiment on the bid premium is enhanced when the acquirer is based in a country culturally prone to herd behavior. According to Schmeling (2009) and Wang et al. (2021), national cultures that promote herding enhance the effect of investor sentiment. In a such environment, a CEO of a bidder firm is more likely to be overconfident about her expectations and tend to overpay. She can also just replicate an excessive behavior of other bidders based on overly optimistic takeover market. This finding supports the idea that bidders’ CEO in different cultures have different biases. Furthermore, our result confirms the fundamental role of the three cultural dimensions (individualism, uncertainty avoidance and masculinity) to justify a behavioral explanation of international stock markets[4].

To capture the incremental effect of investor sentiment resulting from the institutional context, we introduce interaction terms between the Sent variable and institutional variables such as the anti-director rights index, corruption index, efficiency of the judicial system index, accounting standards index, and accruals index. Model 5 shows a negative and significant impact of three interaction terms on bid premiums. The corruption index, efficiency of judicial system index, and accounting standards index reduce the positive impact of investor sentiment on bid premiums. High-quality institutions like judicial system and accounting standards system improve information flow and reduce herding behavior associated to market sentiment.

The interaction with the accruals index shows a positive and significant impact on bid premiums. The impact of investor sentiment on bid premiums is stronger in countries with allowance for accrual accounting. Market institutions influence the effect of investor sentiment as advanced institutions improve information circulation and thus make stock markets more efficient. A high accruals index value indicates that extensive use of accruals accounting is permitted in the country, making this index a poor indicator of an efficient institutional system. These results are in line with H3 and with those of Schmeling (2009) and Wang et al., (2021) find that investor sentiment has less influence in countries with highly efficient institutions and greater market integrity.

Serial deals

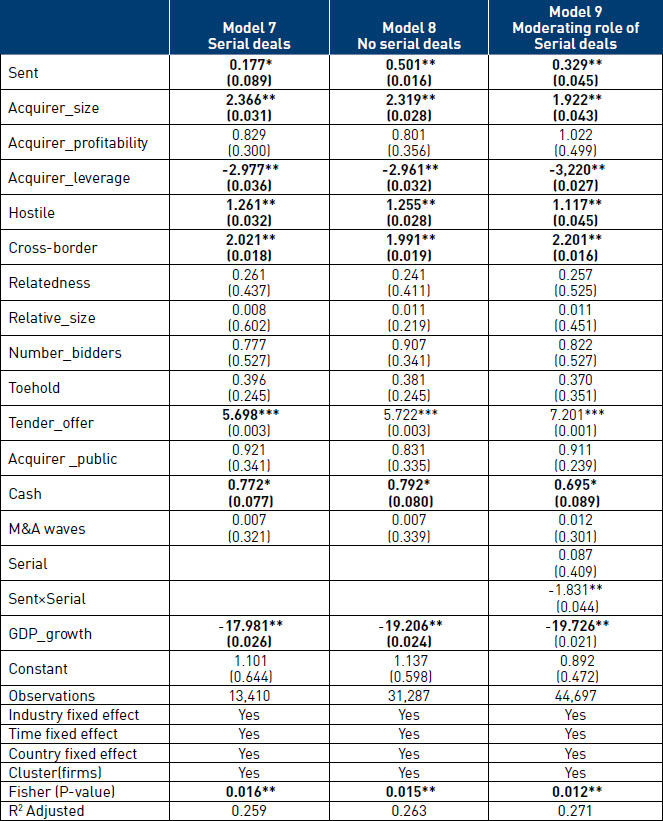

Table 7 examines the effect of serial deals on the relationship between investor sentiment and bid premiums. The first column of the table focuses on bidders announcing more than one deal in the past 12 months while model 8 deals with bidders announcing only one deal. Investor sentiment has a positive effect on bid premiums in both models, but the coefficient for serial acquirers is lower (0.177 versus 0.501).

To test the moderating role of serial deals, we use an interaction term between the Sent variable and the Serial variable. The coefficient of the interaction term in model 9 is negative and statistically significant. The relationship between investor sentiment and the bid premium is attenuated as follow-up deals occur. This result supports the learning effect hypothesis (Aktas et al., 2011). As bidders develop knowledge and expertise across their serial M&A, learning can lead acquirers to develop additional skills in M&A activity. They can select appropriate targets, negotiate better the integration strategy and assess expected synergies more accurately (Collins et al., 2009). Thus, CEOs of serial acquirers are less influenced by market investor sentiment.

Table 7

The moderating role of the serial deals factor

This table presents the result of estimation of the fixed-effects model regression (countries, sectors and years). The dependent variable (Premium) is the deal premium as a percentage. All independent variables are defined in Appendix 2. Specifically, deals are allocated to one of the two groups depending on whether deals are serial or not. Model 7 is used to test the impact of investor sentiment on premium in the serial deals case. Model 8 is used to test the impact of investor sentiment on premium with no serial deals. Model 9 is used to test the moderating role of the serial deals factor. The dependent variable Serial is the number of serial acquisitions completed during the 12 months before the announcement date. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively, computed from standard errors that are clustered at the firm level.

Robustness Tests

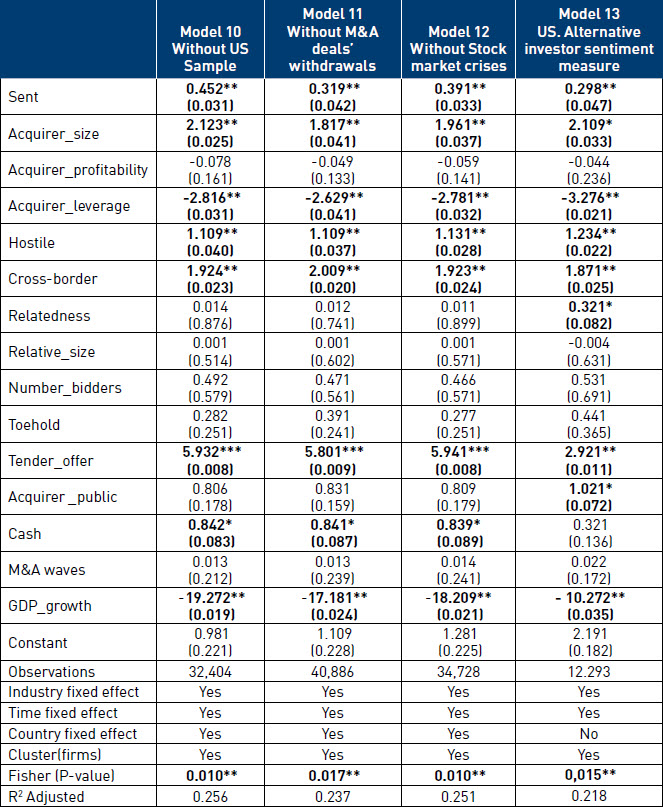

In the following, we perform a battery of robustness checks. The results are presented in Table 8 below.

U.S is considered one of the most individualistic cultures in the world. According to Hofstede (1980), individualistic countries tend to exhibit less herding behavior and the impact of the sentiment is lower in these countries. As a result, the effect of investor sentiment on the bid premium is less pronounced when the acquirer belongs to an individualistic country. As a relatively large proportion of M&A deals took place in the US market, our results can be driven by U.S effects. For this robustness test, we exclude from our sample all U.S bidders during the period 2000-2021 and we re-estimate our model as previously specified. We display the results in column 1 of Table 8. The coefficient associated to investor sentiment measure is still significant and the effect of investor sentiment on the bid premium becomes more pronounced.

Further, we re-estimate our model by removing the withdrawn deals from our sample. According to Jacobsen (2014), CEOs exhibit restraint and cancel a deal when it becomes too expensive. Therefore, the deal status can drive our results. The results tabulated in column 2 of Table 8 confirm that deal status is unlikely to influence the results on the relationship between investor sentiment and bid premium.

We check whether our results are affected by the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 crisis. Crises often trigger M&A waves. For instance, the 2008 financial crisis results into the third wave of bank mergers, when several financial banks acquired failing firms because of their inability to secure funding. During the Covid-19 pandemic, some other merger waves occurred at the aggregate and industry level. As a result, the takeover premiums paid during these crises can drive our results. The results in model 12 reveal that our findings persist. The effect of investor sentiment on bid premium is positive and significant and such effect appears to be even stronger when we exclude deals during the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 crisis from our sample. The reason is that the bidder undervalues a target with high information uncertainty (Li and Tong, 2018) and, therefore, doesn’t tend to overpay for target firms. Excluding announced deals during the crises accentuates the effect of the investor sentiment on bid premium.

Lastly, we also carry out an additional robustness test using the widely-used Baker and Wurgler (2006) sentiment index[5] as an alternative measure of investor sentiment. We limit our analysis to the U.S sub-sample as this sentiment index is only available for the US market. We find that the U.S. consumer confidence index is strongly correlated with Baker and Wurgler sentiment indicator over our study period 2000–2021. The Pearson correlation coefficient is 0.421 and statistically significant at 1%. This finding explains why the consumer confidence index has acquired a solid reputation as a measure of investor sentiment (Lemmon and Portniaguina, 2006; Schmeling, 2009; Antoniou et al., 2013). We also re-estimate the model (2) using the Baker and Wurgler (2006) sentiment index on the U.S sub-sample. The results in model 13 show that our conclusion remain unchanged across this robustness test.

Table 8

Robustness tests

This table reports results from multivariate regression of investor sentiment on bid premium and control variables. Model 10 is used to test the effect of investor sentiment on bid premium for a large sample of M&A data without U.S deals. In model 11, we re-estimate Model 3 without withdrawn deals. Model 12 reports the results obtained from re-estimating Model 3 without stock market crises. Model 13 reports the results using the sentiment measure of Baker and Wurgler (2006) based on U.S sample of M&A data. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively, computed from standard errors that are clustered at the firm level.

Conclusion

This paper provides international confirmation that investor sentiment is an important determinant of bid premiums and plays a role in understanding bidding behavior. A large part of literature offers rational explanation of overpayment phenomenon such as private benefits of control, poor target management and overvaluation of synergies. We adopt a behavioral perspective, and we use a longstanding and established measure of investor sentiment based on the consumer confidence index available for several international markets for long and regular periods of time. Our results indicate that investor sentiment affects significantly and positively bid premiums. High investor sentiment induces CEOs to be more optimistic about creating synergies and tend to overvalue the target expectations and pay high premiums. Thus, this paper joins other studies revealing the effects of behavioral market biases on investing and financing decisions made by CEOs. This is of particular importance in the context of M&A because mispricing the initial bid price may impede the acquirer’s future performance.

The international dimension of our sample allows for investigation of the influence of institutional factors and national cultures on the relationship between investor sentiment and bid premium. Cultural factors such as collectivism, uncertainty and masculinity accentuate the effect of investor sentiment on premiums. Thus, bidders in countries culturally prone to herd-like behavior use to replicate an overpayment behavior when the takeover market is overly optimistic. Furthermore, we find that the investor sentiment has less influence in markets with stronger market institutions than in those with relatively weaker market institutions. Market integrity leads to high level of institutional sophistication characterized by more efficient flows of information. Lastly, we find that managers benefit from their previous experiences and are less influenced by investor sentiment as they conduct M&A transactions. Our results are robust to several checks (alternative measures of bid premium and investor sentiment, respective exclusion of US deals, withdrawal deals, and deals announced during crises).

This paper offers a set of recommendation and important implications for academics and practitioners. Managers and analysts should take into consideration the risk of investor sentiment during target synergies valuation and negotiation process. They should bear in mind that periods of high optimism are followed by excessive bid premiums. Firms undertaking serial corporate acquisition programs may hire experienced managers in M&A field who can be less influenced by market investor sentiment. Lastly, regulators are invited to improve the institutional system (e.g., reducing corruption, enhancing minority shareholder rights, improving judicial system integrity and accounting standards system quality). This can help to avoid target overpayment behavior. Future research might further develop the effects of the investor sentiment on other characteristics of M&A activity.

Parties annexes

Appendices

Appendix 1. Descriptive statistics of the consumer confidence index

This table presents descriptive statistics of the consumer confidence index for each country. The sample periods vary for all sample countries as the starting month depends on data availability, but the ending month is invariably September 2021. The monthly CCIs are obtained from various sources, e.g., national banks, international organizations, and economic development research centers. For some countries (Hong Kong, India, Malaysia, Norway, Russia and Switzerland), the consumer confidence surveys are conducted at quarterly intervals. For these countries, we converted the quarterly CCIs into monthly values.

Appendix 2. Description of variables used in the study

Biographical notes

Pr. Fabrice Herve is full professor of Finance at IAE DIJON University of Burgundy School of Management in France. He is a member of the research laboratory CREGO (EA 7317). His research fields are behavioral finance, investor sentiment, crowdfunding, green finance and entrepreneurial finance.

Ibtissem Rouine: Graduate with a Ph.D. of Finance, Dr. Ibtissem Rouine is a research professor of finance at IDRAC Business School (Lyon Campus, France). Dr. Ibtissem Rouine holds a PhD in Finance from Lille University. He published several articles in well-known journals. Ibtissem Rouine ’s current research is dedicated to mergers and acquisitions, corporate governance, corporate social responsibility & CEO behavior.

Mohamed Firas Thraya is an associate professor of finance at IDRAC Business School (Lyon, France). He holds his PhD from the University of Grenoble Alpes in 2012. He published several articles in academic ranked journals. These articles focus mainly on corporate governance, mergers and acquisitions and corporate social responsibility.

Dr. Mohamed Zouaoui is an associate professor at School of Business Administration (IAE DIJON), University of Burgundy School of Management in France. He is a member of the research laboratory CREGO (EA 7317). His research fields are behavioral finance, asset pricing, investor sentiment and corporate social responsibility.

Notes

-

[1]

Data are available here: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison-tool

-

[2]

See Appendix 1.

-

[3]

See Brown and Cliff (2006) for a detailed discussion of investor sentiment measures.

-

[4]

We also examine the other three cultural dimensions of Hofstede’s framework: the power distance index, long term orientation, indulgence. The results obtained (not reported here but available on request) show that these cultural dimensions do not moderate the relationship between investor sentiment and bid premium. This result is consistent with the literature on investor sentiment as these three cultural dimensions have no link with the behavioral biases of investors.

-

[5]

The and Wurgler (2006) sentiment index is the first principal component of the following six sentiment proxies suggested by prior research: the closed-end fund discount, market turnover, number of IPOs, average first day return on IPOs, equity share of new issuances, and the log difference in book to-market ratios between dividend payers and dividend non-payers. The data are available on http://people.stern.nyu.edu/jwurgler.

Bibliography

- Ahern, K., Daminelli, D., and Fracassi, C. (2015), Lost in Translation? The Effect of Cultural Values on Mergers around the World, Journal of Financial Economics, 117, 165-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2012.08.006

- Ailon, G. (2008). Mirror, mirror on the wall: Culture’s consequences in a value test of its own design. The Academy of Management Review, 33(4), 885-904. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2008.34421995

- Aktas, N., de Bodt, E., and Roll, R. (2009). Learning, hubris and corporate serial acquisitions. Journal of Corporate Finance, 15(5), 543-561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2009.01.006

- Aktas, N., de Bodt, E., and Roll, R. (2011). Serial acquirer bidding: An empirical test of the learning hypothesis. Journal of Corporate Finance, 17(1), 18-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2010.07.002

- Aktas, N., de Bodt, E., and Roll, R. (2013). Learning from repetitive acquisitions: Evidence from the time between deals. Journal of Financial Economics, 108, 99-117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2012.10.010

- Alexandridis, G., Mavrovitis, C.F., and Travlos, N.G (2012). How have M&As changed? Evidence from the sixth merger wave. European Journal of Finance, 18(8), 663-688. https://doi.org/10.1080/1351847X.2011.628401

- Antoniou, C., Doukas, J. A., and Subrahmanyam, A. (2013). Cognitive dissonance, sentiment, and momentum. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 48(1), 245-275. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109012000592

- Bae, K.-H., Kang, J.-K., and Kim, J.-M. (2002). Tunneling or Value Added? Evidence from Mergers by Korean Business Groups. Journal of Finance, 57(6), 2695-2740. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6261.00510

- Baker, M., Fritz F.C., and Wurgler, J. (2009). Multinationals as arbitrageurs: the effect of stock market valuations on foreign direct investment. Review of Financial Studies, 22, 337-369. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhn027

- Baker, M., and Wurgler, J. (2006). Investor sentiment and the cross-section of stock returns. Journal of Finance, 61(4), 1645-1680. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2006.00885.x

- Baker, M., and Wurgler, J. (2007). Investor Sentiment in the Stock Market, Journal of Economic Perspectives 21, 129-151. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.21.2.129

- Bargeron, L., Frederik P., Schlingemann, R.M., Stulz, M., and Zutter, C. (2008). Why do private acquirers pay so little compared to public acquirers? Journal of Financial Economics, 89(3): 375-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2007.11.005

- Bergman, N.K., and Roychowdhury, S. (2008). Investor sentiment and corporate disclosure. Journal of Accounting Research, 46, 1057-1083. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2008.00305.x

- Black, B.S. (1989). Bidder Overpayment in Takeovers, Stanford Law Review, 41(3), 597-660.

- Betton, S., Eckbo, B.E., and Thorburn, K. S. (2008). Corporate takeovers. Handbook of corporate finance. Empirical corporate finance, 2, 291-429 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53265-7.50007-X

- Beugelsdijk, S., Maseland, R., and Van Hoorn, A. (2015). Are Scores on Hofstede’s Dimensions of National Culture Stable over Time? A Cohort Analysis. Global Strategy Journal, 5(3), 223-240. https://doi.org/10.1002/gsj.1098

- Bouwman, C., Fuller, K., and Nain, A. (2009). Market Valuation and Acquisition Quality: Empirical Evidence. Review of Financial Studies. 22. 633-679. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhm073

- Brown, G.W., and Cliff, M.T. (2004). Investor Sentiment and the Near-term stock market, Journal of Empirical Finance 11, 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jempfin.2002.12.001

- Chang, C.C., Hsieh, P.F., and Wang, Y.H. (2015). Sophistication, sentiment, and misreaction. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 50(4), 903-928. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109015000290

- Chiang, Y.M., Hirshleifer, D., Qian, Y., and Sherman, A.E. (2011). Do investors learn from experience? Evidence from frequent IPO investors. The Review of Financial Studies, 24(5), 1560-1589. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhq151

- Chui, A.C.W., S. Titman, and K.C.J. Wei. (2010). Individualism and momentum around the world, Journal of Finance, 65, 361-392. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2009.01532.x

- Ciobanu, R. (2015). Mergers and Acquisitions: Does the Legal Origin Matter? Procedia Economics and Finance, 32, 1236-1247. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)01501-4

- Collins, J.D., Holcomb, T.R., Certo, S.T., Hitt, M.A., and Lester, R.H. (2009). Learning by doing: Cross-border mergers and acquisitions, Journal of Business Research, 62, 1329-133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.11.005

- Danbolt, J., Siganos, A., and Vagenas-Nanos, E. (2015). Investor sentiment and bidder announcement abnormal returns. Journal of Corporate Finance, 33, 164-179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2015.06.003

- Daniel, K.D., Hirshleifer D., and Subrahmanyam, A. (2001). Overconfidence, Arbitrage, and Equilibrium Asset Pricing, Journal of Finance, 56, 921-965. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00350

- Danso, A., Lartey, T., Amankwah-Amoah, J., Adomako, S., Lu, Q., and Uddin, M. (2019). Market sentiment and firm investment decision-making. International Review of Financial Analysis, 66, 101369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2019.06.008

- Dicks, D., and Fulghieri, P. (2021). Uncertainty, investor sentiment, and innovation. The Review of Financial Studies, 34(3), 1236-1279. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhaa065

- Eckbo, B.E. (2009). Bidding strategies and takeover premiums: A review, Journal of Corporate Finance, 15(1), 149-178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2008.09.016

- Eilnaz, K-P., Amini, S., Moshfique, U., and Darren, D. (2020). Does Cultural Difference Affect Investment Cash flow Sensitivity? Evidence from OECD Countries. British Journal of Management, 31(3), 636-658. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12394

- Fama, E.F. (1970). Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work Author(s): Eugene F. Fama Source: The Journal of Finance, 25(2) 383-417. https://doi.org/10.2307/2325486

- Harris, R.S., and Ravenscraft, D. (1991). The role of acquisitions in foreign direct investment: Evidence from the US stock market. Journal of Finance, 46(3), 825-844. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1991.tb03767.x

- Hayward, M.L., and Hambrick, D.C. (1997). Explaining the premiums paid for large acquisitions. Evidence of CEO hubris. Administrative Science Quarterly, 103-127. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393810

- Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills, CA. ISBN 0-8039-1444-X

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequence (2nd ed.), Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA. ISBN: 9780803973244

- Huang, S.X., Keskek, S., and Sanchez, J.M. (2022). Investor Sentiment and Stock Option Vesting Terms. Management Science, 68(1), 773-795. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2020.3845

- Hung, M., (2000). Accounting standards and value relevance of financial statements: An international analysis. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 30, 401-420. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-4101(01)00011-8

- Inglehart R. (1997). Modernization and postmodernization: Cultural, economic and political change in 43 societies. Princeton University Press. ISBN: 9780691011806

- Jacobsen, S. (2014) The death of the deal: Are withdrawn acquisition deals informative of CEO quality? Journal of Financial Economics. 114(1): 54-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2014.05.011

- Jiang, F., Lee, J., Martin, X., and Zhou, G. (2019). Manager sentiment and stock returns. Journal of Financial Economics, 132(1), 126-149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2018.10.001

- Jost, S., Erben, S., Ottenstein, P., and Zülch, H. (2022). Does corporate social responsibility impact mergers & acquisition premia? New international evidence. Finance Research Letters, 46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2021.102237

- Kaasa, A. (2021). Merging Hofstede, Schwartz, and Inglehart into a single system. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 52(4), 339-353. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220221211011244

- La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., and Vishny, R.W. (1998). Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy, 106, 1113-1155. https://doi.org/10.1086/250042

- Lemmon M., and Portniaguina, E. (2006). Consumer confidence and asset prices: Some empirical evidence. Review of Financial Studies, 19, 1499-1529. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhj038

- Li, L., and Tong, H.S. (2018). Information uncertainty and target valuation in mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Empirical Finance. 45(C), 84-107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jempfin.2017.09.009

- Liao, R., Wang, X., and Wu, G. (2021). The role of media in mergers and acquisitions. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 74. 101299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2021.101299

- López-Cabarcos, M.Á., Pérez-Pico, A.M., Piñeiro-Chousa, J., and Šević, A. (2021). Bitcoin volatility, stock market and investor sentiment. Are they connected? Finance Research Letters, 38, 101399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2019.101399

- Lucey, B. M., and Zhang, Q. (2010). Does cultural distance matter in international stock market comovement? Evidence from emerging economies around the world. Emerging Markets Review, 11, 62-78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2009.11.003

- Malmendier, U. and Tate, G. (2005). CEO overconfidence and corporate investment. The Journal of Finance, 60(6), 2661-2700. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00813.x

- Malmendier, U. and Tate, G. (2008). Who makes acquisitions? CEO overconfidence and the market’s reaction. Journal of Financial Economics, 89(1), 20-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2007.07.002

- McLean, R.D., Zhang, T., and Zhao, M. (2012). Why does the law matter? Investor protection and its effects on investment, finance, and growth. The Journal of Finance, 67(1), 313-350. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01713.x

- McSweeney, B. (2002) Hofstede’s Model of National Cultural Differences and their Consequences: A Triumph of Faith—A Failure of Analysis. Human Relations, 55, 89-118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726702551004

- Moeller, S.B., Schlingemann, F.P. and Stulz, R.M. (2004). Firm size and the gains from acquisitions. Journal Financial Economics. 73, 201-228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2003.07.002

- Mpasinas, A. (2007). The Premium Paid. for M&A: The NASDAQ Case, Corporate Ownership & Control, 4(2), 145 -154.

- Nguyen., N.H., and Phan., H.V. (2017). Policy Uncertainty and Mergers and Acquisitions. Journal Of Financial and Quantitative Analysis. 52(2), 613-644. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109017000175

- Offenberg, D., and Pirinsky, C. (2015). How do acquirers choose between mergers and tender offers?, Journal of Financial Economics, 116(2), 331-348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2015.02.006

- Pandey, V.K., Sutton, N.K., and Steigner, T. (2021). Learning in serial mergers: evidence from a global sample. Journal of Business, Finance and Accounting, 48: 1747-1796. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbfa.12548

- Picone, P.M., Dagnino, G.B., and Minà, A. (2014). The origin of failure: A multidisciplinary appraisal of the hubris hypothesis and proposed research agenda. Academy of Management Perspectives, 28(4), 447-468. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2012.0177

- Piñeiro-Chousa, J., López-Cabarcos, M. Á., Caby, J., and Šević, A. (2021). The influence of investor sentiment on the green bond market. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 162, 120351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120351

- Qiu, L., and Welch, I. (2006). Investor Sentiment Measures, Working paper, Brown University and NBER. https://doi.org/10.3386/w10794

- Reuter, C. (2011). A survey of ‘culture and finance’. Finance, 32(1), 75-152. https://doi.org/10.3917/fina.321.0075

- Rhodes-Kropf, M., and Viswanathan, S. (2004). Market valuation and merger waves. The Journal of Finance, 59(6), 2685-2718. Rhodes-Kropf, M., and Viswanathan, S. (2004). Market valuation and merger waves. The Journal of Finance, 59(6), 2685-2718. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2004.00713.x

- Roll, R. (1986). The hubris hypothesis of corporate takeovers. Journal of Business, 59(2), 197-216. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2353017

- Rouine, I. (2018). Target country’s leadership style and bidders’ takeover decisions. International Review of Financial Analysis. 60, 17-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2018.08.004

- Schmeling, M. (2009). Investor sentiment and stock returns. Some international evidence. Journal of Empirical Finance, 16(3), 394-408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jempfin.2009.01.002

- Schwartz S. H. (1994). Beyond Individualism-Collectivism: New Cultural Dimensions of Values. In Kim U., Triandis H. C., Kagitcibasi C., Choi S.-C., Yoon G. (Eds.), Cross-cultural research and methodology series, Vol. 18. Individualism and collectivism: Theory, method, and application (p. 85-119). Sage. ISBN: 0803957637

- Shleifer, A. (2000). Inefficient Markets: An Introduction to Behavioral Finance, in inc. Oxford University Press, ed (New York). ISBN: 0198292279

- Shleifer, A., and Vishny, R.W. (2003). Stock market-driven acquisitions. Journal of Financial Economics, 70(3), 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(03)00211-3

- Simonyan, K. (2014). What determines takeover premia: An empirical analysis. Journal of Economics and Business, 75, 93-125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconbus.2014.07.001

- Smit, H., and Moraitis, T. (2010). Playing at Serial Acquisitions. California Management Review, 53(1), 56-89. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2010.53.1.56

- Stahl, G., and Voigt. A. (2008). Do Cultural Differences Matter in Mergers and Acquisitions? A Tentative Model and Examination. Organization Science, 19(1): 160-176. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1070.0270

- Surendranath, R.J., Thann, N.N., and Wang, D. (2016). Credit ratings and the premiums paid in mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Empirical Finance, 39, 93-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jempfin.2016.09.004

- Varaiya, N.P. (1988). The “Winner’s Curse” Hypothesis and Corporate Takeovers. Managerial and Decision Economics, 9(3), 209-219. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.4090090306

- Wang, W., Su, C., and Duxbury, D. (2021). Investor sentiment and stock returns. Global evidence. Journal of Empirical Finance, 63, 365-391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jempfin.2021.07.010

- Yang, B., Sun, J., Guo, J., and Jiayi Fu, J. (2019). Can financial media sentiment predict merger and acquisition performance? Economic Modelling, 80, 121-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2018.10.009

Parties annexes

Notes biographiques

Fabrice Herve est Professeur en sciences de gestion à l’IAE DIJON – Ecole Universitaire de Management. Il appartient au laboratoire de recherche CREGO (EA 7317). Il est l’auteur ou co-auteur de plusieurs articles portant sur la finance comportementale, le sentiment des investisseurs, la finance entrepreneuriale, la finance verte et le crowdfunding.

Ibtissem Rouine : Diplômée d’un doctorat en Finance, Dr. Ibtissem Rouine est enseignante-chercheuse en finance à l’IDRAC Business School (Campus de Lyon, France). Ibtissem Rouine est titulaire d’un doctorat en Finance de l’Université de Lille. Il a publié plusieurs articles dans des revues de renommée internationale. Ses recherches actuelles sont dédiées aux fusions et acquisitions, la gouvernance d’entreprise, la responsabilité sociale des entreprises et le comportement des dirigeants.

Mohamed Firas Thraya est professeur associé en finance à l’IDRAC Business School (Lyon, France). Il a eu son doctorat de l’université de Grenoble Alpes en 2012. Il est l’auteur de plusieurs articles dans des revues académiques classées. Ces articles portent principalement sur la gouvernance de l’entreprise, les fusions-acquisitions et la responsabilité sociétale des entreprises.

Mohamed Zouaoui est maître de conférences en sciences de gestion à l’institut d’administration des entreprises de DIJON (IAE DIJON) – Ecole Universitaire de Management. Il appartient au laboratoire de recherche CREGO (EA 7317). Il est l’auteur ou co-auteur de plusieurs articles portant sur la finance comportementale, l’évaluation des actifs financiers, le sentiment des investisseurs et la responsabilité sociale des entreprises.

Parties annexes

Notas biograficas

Pr. Fabrice Herve es profesor de Ciencias de la Gestión en el IAE DIJON - Escuela Universitaria de Administración. Es miembro del laboratorio de investigación CREGO (EA 7317). Es autor y coautor de varios artículos sobre finanzas comportamentales, sentimiento de los inversores, finanzas corporativas, finanzas verdes y crowdfunding.

Graduado con un doctorado en Finanzas, el Dr. Ibtissem Rouine es profesor investigador de finanzas en la IDRAC Business School (Campus de Lyon, Francia). El Dr. Ibtissem Rouine tiene un doctorado en Finanzas de la Universidad de Lille. Publicó varios artículos en revistas de renombre. La investigación actual de Ibtissem Rouine está dedicada a fusiones y adquisiciones, gobierno corporativo, responsabilidad social corporativa y comportamiento de los directores ejecutivos.

Mohamed Firas Thraya es profesor asociado de finanzas en el IDRAC Business School (Lyon, Francia). Se doctoró en la Universidad de Grenoble Alpes en 2012. Ha publicado varios artículos en revistas de rango. Estos artículos se centran en el gobierno corporativo, las fusiones y adquisiciones y la responsabilidad social de las empresas.

Mohamed Zouaoui es Profesor de Gestión en el Instituto de Administración de Empresas (IAE) de Dijon. Es autor o co-autor de varios artículos sobre las finanzas del comportamiento, la valoración de los activos financieros, sentimiento de los inversores y la responsabilidad social corporativa.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Conceptual model

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Descriptive statistics

Table 2

Summary statistics by year

Table 3

Summary statistics by acquirer macro industry

Table 4

Summary statistics by acquirer nation

Table 5

Effect of Investor Sentiment on the Deal Premium

Table 6

The moderating role of institutional and cultural factors

This table presents the result of estimation of the fixed-effects model regression (sectors and years). The dependent variable (Premium) is the deal premium in percentage. All independent variables are defined in Appendix 2. Model 4 is used to test the moderating role of the cultural factors. Model 5 is used to test the moderating role of institutional factors whereas model 6 includes both the cultural and institutional factors. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively, computed from standard errors that are clustered at the firm level.

Table 7

The moderating role of the serial deals factor

This table presents the result of estimation of the fixed-effects model regression (countries, sectors and years). The dependent variable (Premium) is the deal premium as a percentage. All independent variables are defined in Appendix 2. Specifically, deals are allocated to one of the two groups depending on whether deals are serial or not. Model 7 is used to test the impact of investor sentiment on premium in the serial deals case. Model 8 is used to test the impact of investor sentiment on premium with no serial deals. Model 9 is used to test the moderating role of the serial deals factor. The dependent variable Serial is the number of serial acquisitions completed during the 12 months before the announcement date. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively, computed from standard errors that are clustered at the firm level.

Table 8

Robustness tests

This table reports results from multivariate regression of investor sentiment on bid premium and control variables. Model 10 is used to test the effect of investor sentiment on bid premium for a large sample of M&A data without U.S deals. In model 11, we re-estimate Model 3 without withdrawn deals. Model 12 reports the results obtained from re-estimating Model 3 without stock market crises. Model 13 reports the results using the sentiment measure of Baker and Wurgler (2006) based on U.S sample of M&A data. *, **, and *** indicate statistical significance at the 10%, 5%, and 1% levels, respectively, computed from standard errors that are clustered at the firm level.