Résumés

Abstract

This paper refines existing literature on supply chain integration (SCI) by exploring its possible adverse effects on higher levels of SCI on firm performance. Furthermore, we explain how trust offsets the negative effects of increased integration. Based on data gathered from 152 firms in the United States, our research reveals two important results: (1) an inverted U-shaped relationship exists between supplier integration and firm performance, (2) the levels of trust attenuate the effects of increased integration on firm performance. Finally, using the relational view and transaction costs theory, we discuss the theoretical and managerial implications of our research results.

Keywords:

- External Integration,

- Supply Chain Integration,

- SCI,

- Trust,

- Relational View,

- Transaction Costs Economics,

- Non-linear Relationship

Résumé

Ce papier affine la littérature existante sur l’intégration de la Supply Chain (SCI) en explorant ses effets potentiellement négatifs possibles sur les niveaux supérieurs de SCI sur les performances d’entreprise. Nous montrons également comment la confiance peut atténuer ces effets négatifs. Sur la base des données recueillies auprès de 152 entreprises aux États-Unis, notre recherche révèle deux résultats importants : (1) une relation en forme de U inversée existe entre l’intégration des fournisseurs et les performances d’entreprise, (2) des niveaux de confiance plus élevés atténuent les effets négatifs de l’intégration accrue sur les performances d’entreprise. Enfin, en utilisant la perspective relationnelle et la théorie des coûts de transaction, nous analysons les implications théoriques et pratiques de nos résultats.

Mots-clés :

- Intégration externe,

- intégration de la Supply Chain,

- SCI,

- confiance,

- perspective relationnelle,

- économie des coûts de transaction,

- relation non linéaire

Resumen

Este documento refina la literatura existente sobre la integración de la cadena de suministro (SCI) al explorar sus posibles efectos negativos en los niveles superiores de SCI en el rendimiento de la empresa. Además, explicamos cómo la confianza contrarresta los efectos negativos de la integración aumentada. Basado en datos recogidos de 152 empresas en los Estados Unidos, nuestra investigación revela dos resultados importantes: (1) existe una relación en forma de U invertida entre la integración del proveedor y el rendimiento de la empresa, (2) los niveles de confianza atenúan los efectos de la integración aumentada en el rendimiento de la empresa. Finalmente, utilizando la visión relacional y la teoría de costos de transacción, discutimos las implicaciones teóricas y de gestión de nuestros resultados de investigación.

Palabras clave:

- Integración externa,

- Integración de la cadena de suministro,

- SCI,

- confianza,

- visión relacional,

- economía de costos de transacción,

- relación no lineal

Corps de l’article

Supply chain integration (SCI) refers to the level whereby a business integrates with its Supply Chain (SC) partners in order to achieve efficient and productive information flows, goods, decisions, money, and documentation that are high in value, fast, and low in cost (Zhao et al., 2008). Integration of the SC has been demonstrated to be positively correlated with company performance (Yu et al., 2013). Although research on SCI has gained momentum, its effect on firm performance has produced contradicting results (Chang et al., 2016; Leuschner et al., 2013; Mackelprang et al., 2014). Prior research has demonstrated how investing in SCI will lead to positive operational performance (cost, quality, flexibilities) (Flynn et al., 2010; Frohlich and Westbrook, 2001; Yu et al., 2013), but it is not conclusive on the direct effect of SCI on firm performance (Flynn et al., 2010; Huo, 2012).

A few studies have explored the adverse effects of SCI (Das et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2015), meaning that the effects of increased integration imply the existence of an inverted U-shaped relationship between SCI and firm performance. That is, pursuing higher levels of SCI might generate negative externalities such as redundancy, rigidity, inertia, and dangerous dependence (Swink et al., 2007; Terjesen et al., 2012). By investigating possible negative effects of SCI, we answer the call of previous authors (Mackelprang et al., 2014; Sacristán-Díaz et al., 2018)the sequence in which these dimensions should be implemented and some possible mediating effects are investigated. Then, relationships are examined more closely to observe whether they present more complex non-linear forms than those usually analysed. Design/methodology/approach: Required information was gathered from a sample of 477 Spanish industrial companies (23.4 per cent response rate, the heterogeneity of SCI results is explained by the existence of possible non-linear relationships between SCI and performance, and that future research in SCI should alter the way it looks at the link between SCI and performance as only direct one. We adopt a multi-theoretical perspective (i.e., a combination of one or more theoretical lenses), as suggested by several scholars, to integrate theoretical approaches from organizational and strategic management to study SCI (Autry et al., 2014). Thus, building on the theoretical rationale of Relational View (RV) and Transaction Cost Theory (TCE), we argue that SCI leads to positive effects on firm performance when kept at a moderate level.

By combining RV and TCE in our theoretical discussion, we propose a model that integrates economic and relational aspects of SCI, allowing us to enhance the predictability of assessing the impact of SCI on firm performance using insights from the RV of competitive advantage and TCE to explain that high levels of SCI will diminish firm performance. The RV concentrates on illustrating how a firm can achieve greater performance through boundary-spanning interactions but fails to mention the economic costs associated with buyer-supplier interactions. As a result, we supplement our analysis of the effect of SCI on firm performance by examining the transaction costs associated with a hybrid governance structure. We deem important the combination of the two different yet complementary lenses to understand the mechanisms underlying the non-linear effects of SCI on firm performance. RV is a theory that explores the role played by inter-organizational links in generating relational rents, thus, it focuses mainly on explaining the positive outcomes of investing in relations with SC partners. However, it does not allow us to explain the conditions under which SCI or inter-organizational relations might lead to negative effects. To study the latter effects, we used TCE to go beyond the positive and linear relation between SCI and firm performance, by analyzing and explaining the effects of extensive integration with partners on transaction costs. Finally, we integrate trust as a moderator in the relationship between SCI and firm performance.

Prior research has shown the positive effects SCI might have on supply chain performance. SCI has been positively associated with operational performance (Flynn et al., 2010; Wong et al., 2011), customer satisfaction (Swink et al., 2007), and financial performance (Flynn et al., 2010; Vickery et al., 2003). However, the effect of SCI on firm performance is not a straightforward relationship and, hence, empirically subject to mixed findings. Firm performance as an outcome is used to measure both market effectiveness, including sales growth and market share, and financial effectiveness, including ROA, ROE, and profitability (Mackelprang et al., 2014). While some prior research has found an insignificant direct relationship between SCI and firm performance (Flynn et al., 2010; Leuschner et al., 2013), others have demonstrated mixed findings. For instance, Vickery (2003) found that customer service fully mediates SCI’s effect on firm performance. Rosenzweig (2003) found that SCI was positively and directly associated with ROA and revenues of new products, while the association between sales growth and customer satisfaction was insignificant. Huo (2012) found no significant direct relationship between firm performance and the two dimensions of SCI (supplier and customer integration). To address this gap, the following two research questions are asked in this study:

RQ1: Does supply chain integration generate only positive performance outcomes?

RQ2: How do relational factors such as trust reinforce the impact of supply chain integration on performance outcomes?

To answer these questions, our study suggests that SCI’s impact on firm performance is an inverted U-shaped instead of a linear one. To do so, we test and validate the non-linear relationship between SCI and firm performance using theoretical insights from RV and TCE. Hence our manuscript offers two important contributions to the literature on SCI. First, we empirically validate the non-linear relationship between SCI and firm performance. By doing so, we offer an alternative explanation for the mixed findings of the SCI-Firm performance link. Extant literature on SCI has mainly investigated a linear and positive relationship with firm performance. Despite conflicting results on the nature and effect of SCI on firm performance, the negative effect and non-linear effect have seldom been explored. Our results indicate that engaging in SCI activities generates positive returns to a certain point, after which the returns will decline. Second, we validate the moderating effect of trust on the relationship between SCI and firm performance. The role of trust as an antecedent has been explored as a major variable that facilitated the implementation of SCI practices among SC partners. In our study, we hypothesize trust’s role in mitigating detrimental effects and empirically validate its positive role as a moderator. Thus answering the call of previous scholars (Mackelprang et al., 2014) to investigate unknown moderators between SCI and performance outcomes. Our study’s findings show that developing trust among partners offsets the negative effects of high SCI.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The next section presents a review of the related literature on the relation view, transaction cost economics, and their link to SCI, firm performance, and the moderator variable trust. Section 2 develops a research model and hypotheses. Section 3 describes the research methodology used, followed by a presentation of the study’s findings. We conclude the paper with the theoretical and practical implications of these findings.

Theoretical Background

In this study, we examine the positive and negative effects of SCI on firm performance and explain how trust can moderate this relationship. In the following subsections, we will present the positive and negative effects of SCI on firm performance; then we will describe SCI and trust as our central constructs from a RV and TCE perspective.

Supply Chain Integration and Firm performance

Based on (Flynn, Huo, and Zhao, 2010) definition, SCI is the extent to which a “manufacturer strategically collaborates with its SC partners and collaboratively manages intra- and inter-organization processes” (2010, p. 59). Two types of integration have been identified: internal integration (Swink and Schoenherr, 2015) and external integration (Flynn et al., 2010). Internal integration focuses on the in-house processes and aims to synchronize and connect the intra-organizational processes by overcoming the existing functional silos (Swink and Schoenherr, 2015). External integration is oriented toward external partners of the firm, namely suppliers and customers. It refers to the extent to which a firm collaborates with external partners through inter-organizational practices to synchronize and streamline processes and improve SC performance (Flynn et al., 2010). In our paper, we focus specifically on external integration since we are interested in investigating the relationship of inter-organizational trust with supplier and customer integration. Similar studies (Zhang and Huo, 2013) have adopted the same approach by limiting the scope of the analysis to the external integration dimension.

The question of SCI impact on performance outcomes has been studied for more than twenty-five years now (Fabbe-Costes and Jahre, 2008; Frohlich and Westbrook, 2001; Vickery et al., 2003); nonetheless, non-linear and negative outcomes have seldom been empirically investigated. Chang et al. (2016), found that supplier integration’s impact on firm performance is negative and direct; however, when operational and relation performance are included as mediators, the investment in supplier integration generates a positive firm performance. For customer integration, the authors found that it does not directly impact firm performance, only when mediating variables are considered. As a result, customer integration leads to a positive indirect effect on firm performance. Sacristán-Díaz et al., (2018)the sequence in which these dimensions should be implemented and some possible mediating effects are investigated. Then, relationships are examined more closely to observe whether they present more complex non-linear forms than those usually analysed. Design/methodology/approach: Required information was gathered from a sample of 477 Spanish industrial companies (23.4 per cent response rate focused on studying the relationship between SCI dimensions and provided empirical support for the existence of a sequence of implementation of internal, financial, physical and information flow integration. Using different conceptualizations of SCI, the authors found support for the existence of precedence of external integration of information flows over the other forms of external integration of flows (financial and physical). Although not hypothesized, the authors observed the existence of non-linear relationships between the studied SCI dimensions, but the impact on performance outcomes was not covered in their study. Qi et al., (2017)supply chain strategies (SCSs explored enablers of SCI and the impact of internal and external integration on financial performance. The authors did find empirical support for the link between internal integration and financial performance, whereas the positive and direct link between external integration and financial performance was not supported due to the potential existence of unknown moderators or mediators. Song et al., (2019) explored SCI dimensions as enablers of performance in Omni-channel retailing. Although the authors adopted different conceptualizations of SCI dimensions, their findings lend empirical support for the relationship between SCI dimensions and the performance of omnichannel retailing firms. All of these studies have reported a positive significant or non-significant relationship between SCI and performance outcomes. However, we are still observing that each paper conceptualizes SCI dimensions differently, as reported in Appendix-1. Also, these studies focus on explaining the positive and linear relationship between SCI and firm performance. To address the gap in the literature, we will investigate non-linear relationships and possible detrimental effects of SCI on firm performance. Hence, our current study seeks to go beyond the current orientation of the literature by exploring the risks and conditions that lead to a change in the impact SCI might exert on firm performance. In the next sub-section, we will mobilize RV and TCE theories to examine the positive and negative effects of SCI on firm performance.

The Polymorphism of SCI from the Relational View and Transaction Cost Economics

The major premise upon which the relational view is built, suggests that “idiosyncratic inter-firm linkages may be a source of relational rents and competitive advantage” (Dyer & Singh, 1998). In other words, trading partners may achieve jointly a supernormal profit that they cannot generate if they operate separately, thanks to the combination of their idiosyncratic contributions (Dyer and Singh, 1998; Zajac and Olsen, 1993). Previous studies demonstrated that SCI requires investment in relation-specific assets, such as tailoring information technology to the partner specificities (Klein, 2007)focusing on the performance impacts of (1 and investment in relationship commitment (Zhao et al., 2011). Moreover, SCI implementation necessitates the utilization of complementary assets to achieve its objectives (Narasimhan et al., 2010). Finally, integration with SC partners involves a socialization process based on trust and commonality of interests that constitute a form of informal safeguard (Dyer and Chu, 2003). Therefore, by using the relational view as a theoretical lens, we conceptualize SCI as a form of an alliance that is based on relational-specific assets, knowledge sharing, complementarities, and governance mechanisms (Dyer and Singh, 1998), which will lead to a higher level of performance.

TCE has been used as a suitable theoretical lens to study SC collaborative practices (Nyaga et al., 2010). In considering SCI, TCE states that firms should perform better if they appropriately adjust their governance mechanisms to underlying transactions (Williamson, 1975). In our study, we view SCI as a hybrid governance mechanism adopted by firms to protect their transaction-specific assets. A bilateral hybrid governance structure relates to alliances, partnerships, and collaborative relationships (Nyaga et al., 2010). As suggested by Swink, Narasimhan and Wang (2007), SCI can generate both positive and negative outcomes. From a TCE perspective, higher levels of integration will translate into rising costs of coordination and risks (Das et al., 2006; Williamson, 1985). Integrating tightly with SC partners exposes resource allocation decisions to external influence by other entities, which renders the boundaries of the firm blurry (Pillai et al., 2017). As a result, decision-making is negatively affected, leading to inefficient resource allocation and an inward focus and largely ignoring changes in external demand (Pillai et al., 2017). Being closely aligned with the SC partners affects flexibility and weakens the firm’s ability to achieve its targeted goals regarding cost and quality (Flynn et al., 2010; Wong et al., 2011).

The Role of Trust in the Relationship between SCI and firm performance

Williamson considers two main assumptions regarding human behavior for the TCE’s analytical framework: bounded rationality and opportunism. Under the condition of bounded rationality condition, actors will experience difficulty drawing comprehensive contracts to accommodate environmental uncertainty on an ex-ante basis and ensuring the partner is performing according to the contract on an ex-post basis (behavioral uncertainty) (Williamson, 1975). According to Zand, (1972), the existence of trust will allow exchange parties to share more accurate, timely, and comprehensive information, alleviate controls on parties, and enhance the disposition to influence others. As a result, trust is instrumental in lowering the impact of uncertainty (Zand, 1972), mitigating the impact of bounded rationality on the exchange relationship.

The other behavioral assumption of the analytical framework of TCE is opportunism. TCE considers opportunistic behavior as a probability that any actor will engage in some time; more importantly, this probability is boosted when the other party to an exchange invests in specific assets (Hill, 1990). The presence of trust in contractual relationships reduces the risk of opportunism and lowers contractual safeguards costs. As a result, transaction costs related to the implementation of these safeguards in the form of negotiation, contract drafting, and monitoring are incurred (Chiles and Mcmackin, 1996). Williamson (1985) contends that TCE’s primary focus is studying transaction cost management, yet, these costs should be investigated in the social context in which they are located. He considered that “trust is important and businessmen rely on it much more extensively than is commonly realized” (Williamson, 1975, p. 108). Trust is a central pillar in building a long-term relationship, ensuring business continuity and efficiency with partners, and the success of integration with partners is based on relational elements such as trust (Saikouk et al., 2021; Sambasivan and Yen, 2010). In addition to this, trust has been identified as a factor to offset the cost of opportunistic behavior by the exchange parties (De Ruyter et al., 2001). We define trust as the extent to which the company is confident that its key external partners (suppliers and customers) will not exploit its vulnerabilities (Dyer and Chu, 2003). Trust can be depicted along three aspects: reliability, fairness, and benevolence. From an economic perspective, the presence of trust (non-contractual) among exchange partners is valuable since it supersedes formal contracts, thus reducing significantly contract writing, monitoring, and enforcement. Subsequently, trust plays a significant role in reducing transaction costs. Thus, by introducing trust in our model, we expect the transaction costs related to managing the SC relationship to be attenuated. Next, we will present in “Figure 1” our theoretical model, then we will discuss the related hypotheses.

Figure 1

Research Model

Hypothesis development

Supply chain integration impact on firm performance

Close collaboration with SC partners is conducive to knowledge exchange (Singh and Power, 2014). Also, close collaboration with suppliers is positively associated with knowledge generation and innovation (Perols et al., 2013). SCI allows the firm to leverage complementary resources or capabilities of partners that will not be able to access it. By integrating with the suppliers and customers, a firm can create synergies among each party’s resources to generate superior relational rents. For example, if a manufacturing firm collaborates closely with a customer with specific expertise and know-how in distribution, the firm will be able to leverage its expertise in distribution by joining the resources of both SC partners to achieve a higher level of performance. By itself, SCI can be viewed as a form of governance mechanism to safeguard the partners against opportunism and engage them in value-creative initiatives (Dyer and Singh, 1998). Investing in relation-specific assets acts as collateral to the relationship (Dyer and Singh, 1998) that can warrant a commitment of the partners to achieve better performance. Also, SCI has been identified to be positively associated with relational antecedents such as commitment and reciprocity, which are considered the cornerstone of long-term oriented relationships (Chen et al., 2013). The existence of relationship commitment signals the parties’ preparedness to co-invest and collaborate to achieve sustained profits over time. It also deters opportunistic behaviors that might arise, which reduces the costs of coordination. Indeed, the existence of these relational antecedents can replace the formal safeguarding mechanism of agreements (Fattam et al., 2022). It translates into a reduction in the costs of building a long-term relationship, subsequently incentivizing firms to invest in relation-specific assets.

Based on TCE arguments, seeking higher levels of integration with upstream and downstream partners incurs higher costs that outweigh the benefits of SCI (Das et al., 2006; Swink et al., 2007). Aligning the processes of the firm with its suppliers and customers is resource-intensive and develops over time. It requires investment in relation-specific assets tailored to the current and foreseeable needs of the firm and SC partners. As a result, responding to shifts emanating from the market becomes challenging and costly, given the complexity and interconnectedness between the SC partners.

Consequently, instead of the adaption required of one entity, multiple inter-firm linkages, and processes will need to be readjusted, consuming more time and money. SCI is implemented by the SC partners to achieve a higher level of operational, financial, and firm performance, given the current convergence of objectives of the firm with its suppliers and customers. Although SCI has been proven to enhance operational performance regarding flexibility, delivery, quality, and cost-efficiency (Flynn et al., 2010), it becomes a liability when the partners’ goals are no longer aligned. Considering that invested resources in the relationship will lose value if the firm wants to redeploy elsewhere, the firm will become heavily dependent on its partners in its decision-making. Therefore, a high level of interdependence is established among the partners that lead the firm to be locked into the relationship, raising the costs of SCI consequently.

Furthermore, close integration with SC partners generates, over time, a reduction in the clash of ideas that creates a negative form of cohesiveness that obstructs the flow of information from entities outside the relationship. Hence, limiting the firm’s ability to be exposed to new information or learning opportunities is sensitively limited (Pillai et al., 2017). Accordingly, high levels of SCI require an investment of time, commitment, and resources. These factors might render the SCI an inertial force in the face of structural change. Considering the amount of time and commitment invested in SCI, the firm will be reluctant to operate changes and will prefer to postpone it, which will negatively affect its profitability.

Furthermore, integrated SC partners tend to focus on the internal necessities of the network, ignoring external variations in demand for products. This situation leads to an inefficient decision-making process and inadequate resource allocation of a firm’s resources. Finally, integration with suppliers and customers involves a long-term-oriented relationship that might lead to a risk of demotivation amongst the partners to continuously seek higher levels of performance (Swink et al., 2007). All these negative externalities will raise the costs of SCI activities, limiting the firm’s firm performance. Based on the argument developed from an RV and TCE perspective, we suggest that SCI is beneficial up to a certain point. Passing this threshold, higher levels of SCI will lead to a decrease in firm performance. As a result, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1: There is an inverted U-shaped relationship between supplier integration and firm performance

H2: There is an inverted U-shaped relationship between customer integration and firm performance

The Moderating Effect of Trust on the Link between Supply Chain Integration and Firm Performance

From a TCE perspective, the existence of trust in the relationship will drive transaction costs down. Trust is considered a strong signal for the SC partners’ willingness to sustain a long-term inter-firm relationship and reinforce confidence in the partnership. Hence the transactions are not limited to short-term gains (Johnston et al., 2004). Indeed, in the presence of high trust, SC partners will reduce the time and effort in negotiating contract terms. A relationship with SC partners, based on trust, requires less bureaucratic monitoring and contract rigidity. Subsequently, the firm will be able to ameliorate its flexibility and capability to adjust quickly to market changes without complex and costly procedures and contract adjustments. For instance, if a change in market conditions triggers a need for intra-organizational restructuring that will require a lot of contractual negotiations’, then high levels of SCI coupled with the possible reluctance of partners might act as an inertial force to adjust. The existence of trustworthy relationships among partners will endow the SC partners with the necessary confidence in the firm to act in the best interest of the partners and to divide future payoffs equitably.

Furthermore, considering the assumption regarding the bounded rationality of economic actors, the contracts are viewed as incomplete and non-comprehensive. In the presence of trust, SC partners will be confident in the benevolence of each other and will collaborate without spending additional resources to tighten contracts. Additionally, SC partners are willing to be vulnerable, given their trust in the other party, that it will not behave opportunistically. Thus, SC partners will not invest heavily in monitoring mechanisms, which will positively impact the total SC performance. Another recognized benefit of building a trusting relationship with SC partners is opportunism deterrence. Even though SCI generates varying levels of dependence among the SC partners, the existence of trust acts as a mechanism to deter opportunism from upstream and downstream partners. Indeed, prior studies indicated that informal safeguards such as trust are the most effective forms of safeguarding specialized investment and supporting complex exchange relationships (Uzzi, 1997). Therefore, instead of reducing their efforts to improve the overall firm performance of the supply chain, they will think of new ways to improve it, knowing that future rewards will be granted and shared. Furthermore, relationships characterized by higher levels of trust require less monitoring, writing, and enforcing, and less third-party monitoring (Hill, 1990). Thus coordination costs among the SC partners are reduced.

Another benefit of trust is related to enhancing information sharing. The SC partners will be more inclined to share sensitive and/or valuable information about costs, and process innovations thanks to the confidence stemming from the existence of trust. Since SC partners trust each other not to act opportunistically, they will be more inclined to share information regarding production costs or process innovation, thus improving SC performance. For instance, during an economic recession and based on the willingness to be vulnerable to the SC, a supplier might share product cost breakdown with downstream partners in order to find new ways to lower total costs, knowing and trusting that the other party will not exploit this opportunity to squeeze profits now or in the future. Thus, partners will willingly share this type of information since they believe the firm will divide the payoffs of such information fairly and not use it opportunistically. Klein (2007)focusing on the performance impacts of (1 has empirically demonstrated the positive impact of trust on information sharing, while several scholars have suggested that trust enhances coordination and mutual efforts to reduce inefficiencies.

Additionally, Johnston (2004) empirically demonstrated that trust is necessary for buyer-supplier activities to deliver improved performance. For instance, when a change in demand occurs, the downstream partner will be prone to share valuable and accurate information promptly, based on the confidence that the SC partners will use the information for the benefit of the group. Hence, SC partners are reassured by the nature of trust that future benefits and costs will be managed and divided fairly; also, the cost of up-front safeguards will be lowered given the benevolent nature of the trustees. Therefore, we can conclude that the higher the level of trust among SC partners, the lower the transaction costs incurred. Thus, using TCE arguments, we argue that trust will allow the company to strengthen supplier and customer integration on firm performance. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

H3a: Trust positively moderates the relationship between supplier integration and firm performance.

H3b: Trust positively moderates the relationship between customer integration and firm performance.

Methodology

Data Collection and Sampling

We used an online-based survey using Qualtrics to collect data from SC executives from the USA. We targeted top managers and executives working in SC management activities such as operations, purchasing, and SC management. These respondents are selected because they are knowledgeable about the activities of their company and its relationships with SC partners and can readily access information about the company (Liu et al., 2016). All scales in our survey were derived from previously verified studies (Please see next section). A preliminary version of the questionnaire was distributed for review to academics and SC managers/executives. Then, we used their suggestions to enhance the survey’s clarity. The revised questionnaire was subsequently pretested with fifteen SC specialists from a variety of industry sectors. A final version of the questionnaire was created based on feedback from SC managers.

We used a third-party online survey administration company to collect data from US SC managers and executives. Previous research has used Qualtrics Panels as a credible data collection instrument (Courtright et al., 2016). An online survey link was sent to an estimated pool of 842 participants identified randomly by Qualtrics, and 152 usable completed surveys were received, corresponding to an 18.05% response rate. A key informant approach was followed to develop the survey for this study. Key informants are commonly used in similar studies in the field of SC research (Swink and Schoenherr, 2015). In our survey, 40% of the respondents are SC directors and VPs, and 17.8% occupy a Manager or VP position in SC-related activities (materials handling and purchasing). In addition to this, more than 65% of the respondents are highly experienced professionals in SC activities, with at least nine years of experience in the field. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the sample and it reflects the diversity of the respondents’ profile by industry sector, number of employees, positional experience, and job title.

To address potential issues regarding the quality of our data, screening questions, and attention checks were used to eliminate and disqualify inadequate or fraudulent respondents. The company Qualtrics contacted posted the survey to an estimated pool of 842 participants. As the survey was posted to the panel through Qualtrics channels, 437 target participants did not answer the survey. From the targeted 842 participants, 405 individuals agreed to participate in the study, of which 240 responses were screened out (quality checks), from which 17 were not located in the US, 135 did not have the required experience in SC activities and 88 respondents do not work in SC related activities. An additional 13 responses were eliminated for speeding behavior. Finally, 152 responses were identified as complete and valid. As survey software and internet connectivity are expanding, the utilization of online panels is experiencing a surge, yet, researchers observed continuous diminishing response rates across all survey modes as the online surveys are proliferating, and respondents are excessively solicited (de Beuckelaer and Wagner, 2012)but small samples can limit the reliability and validity of empirical research findings. The purpose of this article is to analyze the status quo and provide a discussion of methodological issues related to the use of small samples in SCM research. An in-depth review of 75 small sample survey studies published between 1998 and 2007 in three journals in the field that frequently publish survey-based research papers (TJ, IJPDLM, and JBL. Subsequently, it is becoming more challenging to acquire a satisfying level of responses to perform a robust analysis of data (Schoenherr et al., 2015). Considering the aforementioned reasons, it is more convenient and interesting for researchers to have recourse to a pre-screened, pre-recruited panel of users who accept to participate in studies matching their profile in return for rewards (Callegaro et al., 2014). As an incentivized panel of respondents is increasingly utilized by researchers, supplementary data quality problems arise (Callegaro et al., 2014), and need to be addressed. Researchers (Schoenherr et al., 2015) have identified issues that might critically hinder the quality of data, such as fraudulent respondent behavior, speeding, and inattentive respondents. To operationalize the constructs (supply chain integration, firm performance, and our moderator variable trust), we employed multi-item scales.

Table 1

Sample characteristics

Measures

To determine the measures for our survey instrument, we surveyed existing literature to identify reliable and valid scales. All scales used in this study were adopted from existing literature (Malhotra and Grover, 1998). A seven-point Likert scale was used for all the constructs (where 1= Strongly disagree and 7= Strongly agree), except for SCI was measured on a seven-point Likert Scale (where 1= Not at all and 7= Extensively).

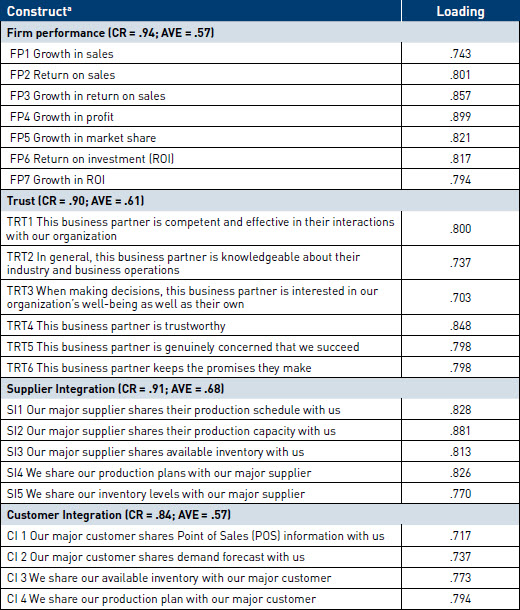

Dependent variable: Firm performance

To measure firm performance, we adopted the scale used by (Narasimhan and Kim, 2002)the competitive environment, and technological intensity\\nof the product, but also on product and market characteristics.\\nConsequently, supply chain integration (SCI. Respondents were required to evaluate the performance of their firm against the performance of their major competitor along seven items including sales growth, market share growth, ROI growth, and profit growth. The measure showed acceptable international consistency with a Composite Reliability (CR) of 0.94 and acceptable discriminant validity with an Average Variance Extracted (AVE) of 0.57.

Independent variables: Supply Chain Integration

We measured SCI in its supplier and customer dimension using scales adopted from (Flynn et al., 2010; Frohlich and Westbrook, 2001). In this study, we used items in our SCI scale that reflect the definition of SCI as external integration using items that measure the intensity of sharing and synchronizing SC processes with upstream and downstream partners through inter-organizational practices. We asked respondents to indicate the extent of integration or information sharing between their firm and the major supplier or customer. We used five items to measure supplier integration, including practices of production schedule sharing, production capacity sharing, and inventory levels sharing. To evaluate customer integration, we used four items, including sharing and integration of practices related to demand forecasts, Point of Sale (POS) data sharing with the firm, and production and inventory levels sharing. Both Supplier integration and customer integration measures displayed acceptable international consistency with a respective CR of 0.91 and 0.84 and acceptable discriminant validity with a respective AVE of 0.68 and 0.57.

Moderating Variable: Trust

The moderating variable trust was measured using the scale adopted from (Doney and Cannon, 1997; Klein, 2007)focusing on the performance impacts of (1. Trust items capture the three characteristics of trust: benevolence, integrity, and ability. Respondents were asked to indicate to which degree the statements reflect the level of their trust in their business partners along the supply chain. We used six items for trust including, trustworthiness, knowledge of the partner their operations and industry, and genuine concern for the well-being of the firm. The measure of trust displayed an acceptable internal consistency with a CR of 0.90 and an AVE of 0.61.

Control Variables

To account for the possible differences among organizations, we included relevant variables as controls in our research model. We controlled for firm size by measuring the number of employees to account for the difference in the level of SCI between small and large-sized companies (Chen et al., 2013). Also, long-establish relationships between partners will be characterized by a higher level of trust. Thus we include the supplier relationship duration as a control variable (Bode et al., 2011). We also controlled the industry sector of companies to account for possible variations among the various sectors in our study. To offset the effect of environmental uncertainty among different industries, we included environmental uncertainty as a control variable in our model. Finally, as trust and integration effects take time to develop, the perceptions of experienced managers in SC management will differ from the less experienced. To control for this effect, we included two relevant variables: SC experience and work experience inside the firm.

Common method bias

We collected our data from a single respondent, which renders common method bias a threat to the validity of our empirical interpretations (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Therefore, we decided to implement a set of measures to mitigate the risk of common method bias distorting the validity of our results. First, we have ensured our respondents of the anonymity and confidentiality of their answers to reduce social desirability that is closely linked to common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Second, we applied different Likert-type scales to our questions. Hence we used “Not at all” to “Extensive” for SCI dimensions, while the outcome variable was measured along the scale of “Much worse” to “Much better” (Grewal et al., 2010). Third, we shuffled the questions in our survey to avoid creating logical connections between the variables. Finally, no single factor emerged nor accounted for the majority of variance when we used Harman’s single factor test (Harman, 1976) to run a principal component factor on all our scale instruments simultaneously. Therefore, we can conclude that common method bias is not a major threat to the validity of our data.

Reliability and validity

To assess the unidimensionality, reliability, and validity of the measurement used in our model, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) see (Table 2). Overall, the results of the model fit indexes were good and ensured the unidimensionality of constructs: (χ² = 410 (df = 201,χ²⁄df = 2.04); comparative fit index (CFI)=.94; tucker-lewis index (TLI)=.93; incremental fit index (IFI)=.94; and the root mean square error of approximation index (RSMEA) =.06). These factors allow us to assess the fit of the proposed model to our data (Gerbing and Anderson, 1988). We included the correlations, means, and standard deviations in Table 3. To evaluate the convergent validity of the constructs, we have tested factors loading, composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE). All our factor loadings demonstrate a level higher than 0.5 and significant at (p < .001) (Hair et al., 2010), which establishes a high convergence of our measurement instruments. Besides, all CR values for our constructs are greater than 0.7 (Hair et al., 2010), thus assuring internal consistency and convergent validity. Additionally, the examination of the AVE results for all the constructs allowed us to ensure convergent validity, as the AVE for all measures was greater than 0.5. Finally, to establish discriminant validity, we verified if the AVE is exceeding the squared correlations of the remaining constructs (Hair et al., 2010). The analysis of these results demonstrated that our constructs do not violate this rule; thus, discriminant validity is supported.

Table 2

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The first item in each scale was fixed to a loading of 1.0 in the initial run to set the scale of the construct. Observed CFA fit statistics were: X2 (410) = 201; TLI = .933; incremental fit index = .944; comparative fit index = .943; root mean square error of approximation = .06

Table 3

Correlations Table

Results and analysis

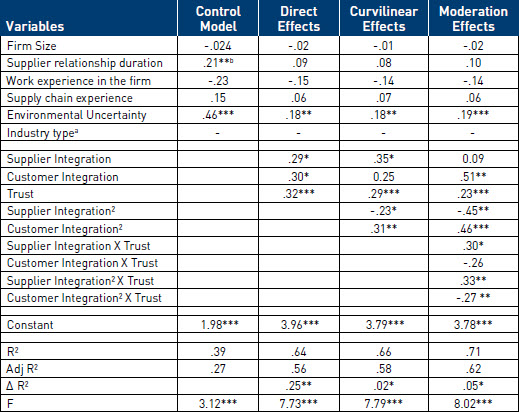

In our study, we hypothesize and test two inverted U-shaped relationships: first, we are examining the link between supplier integration and firm performance (H1), and second between customer integration and firm performance (H2). We also examine the moderation effect of trust on the hypothesized curvilinear relationships (H3a and H3b). To investigate the main effects and moderation effects separately, we build four models, as shown below. The results of the curvilinear hypotheses and moderation effects are presented in (Table 4). We ran multi-collinearity checks, and the results displayed a mean Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) of 2.33, which varies between 1.53 and 2.53 for all independent variables, since it is well below the suggested cutoff value of 10, we conclude that multi-collinearity is a not concern in this study.

Model 1 (Table 4) was used to include only control variables and shows an overall F = 3.12 at (p < .001), which can mainly be attributed to the significant effect of the controlled variable environmental uncertainty. In model 2, we add the main linear effects for the independent variables supplier integration, customer integration, and trust to the control model. The model was overall significant at F = 7.73 at (p < .001) and a significant increase in R² ∆R² =.25 at (p < .01). In model 3, we included the curvilinear terms of supplier integration squared and customer integration squared. The overall model was significant at F =7.79 at (p < .001) and a significant increase in R² ∆R² =.03 at (p < .05), which demonstrates a significant 3% increase compared to the main effects model after the consideration of the curvilinear effects. In the end, the interaction terms of supplier integration, supplier integration squared, customer integration, and customer integration squared, with trust. We found that the overall model was significant at F =8.02 at (p < .001) and a significant increase in R² ∆R² =.05 at (p < .05).

Table 4

Regression results for Firm performance

Sample size for all models, N = 152.

a Industry type was included as a dummy variable, but it was not included in the table for the sake of brevity.

b Standardized regression coefficients are shown: * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001

To demonstrate an inverted U-shaped relationship between two constructs, two conditions must be verified: the linear relationship between the two constructs must be positive and significant, and the quadratic relationship must be negative and significant (Wales et al., 2013). Our results demonstrate that supplier integration has an inverted U-shaped relationship with firm performance (std β = .35,ρ < .05) and supplier integration squared has a negative and significant relationship with firm performance (std β = -.23,ρ < .05); thus we find support for H1. Our second hypothesis, H2, suggested a curvilinear relationship between customer integration and firm performance. In model 3, the linear relationship between customer integration and firm performanceis not significant, and the squared customer integration link to the dependent variable is positive. Hence, we do not find support for H2. The last set of hypotheses examines the moderating effect of trust on SCI dimensions. The results of model 4 indicate that the interaction term of trust and supplier integration is positive and significant (std β = .33,ρ < .01), therefore we find support for H3a. Finally, H3b is not supported since the hypothesized curvilinear relationship between customer integration squared, and firm performance was not supported.

To investigate further the moderating role of trust on the curvilinear relationship between supplier integration and firm performance, we realized a plot of trust and supplier integration for two levels of each variable, namely low and high (mean ± 1 SD) against firm performance (Figure 2) (Aiken et al., 1991). The plot evidences visually the role played by high levels of trust in offsetting the negative effects of supplier integration on the firm performance. Hence, the difference between the level of firm performance between low and high levels of supplier integration is contingent upon trust level. The interaction graph shows that for all levels of trust, firm performance levels increase in hand with increasing levels of supplier integration until a certain point when it starts to decrease. The plot of the interaction presents two segments with firm performance levels increasing first and then decreasing afterwards as supplier integration raises. More importantly, the amelioration in firm performance related to increasing supplier integration (shown in the graph) is larger at a high level of trust than at low levels of trust. Also, the contraction of firm performance is associated with an increased level of supplier integration; however, the firm performance is greater at a low level of trust than at a high level of trust, consequently supporting H3a.

Figure 2

Interaction results of Supplier Integration with Trust

Discussion and Implications

This paper investigated the non-linear relationship between SCI and firm performance and the moderation effect trust might have on this relationship. Most of the published studies attempted to verify the linear effect SCI dimensions can exert on both operational and firm performance. However, the mixed findings reported in the previous studies (Ataseven and Nair, 2017; Leuschner et al., 2013; Mackelprang et al., 2014) suggest the existence of a non-linear relationship between supplier integration, customer integration, and firm performance. This finding is of the utmost importance, as it explains partially the reason behind the conflicting results concerning SCI and firm performance. Thus, by exploring the non-linear relationship between SCI and firm performance, we explained the benefits firms might derive from integrating with SC partners. More importantly, we added nuance to the literature by underlining that SCI will lead to lower firm performance if extensive integration is pursued.

To begin, our findings fully support our hypothesis that supplier integration has a detrimental effect on firm performance. Following that, our findings established that supplier integration has a linearly positive effect on firm performance. Additionally, our findings provide empirical support for the presence of a detrimental influence on supplier performance that extensive supplier integration may have. Our results are in line with previous studies that have explored possible negative effects of integration (Das et al., 2006; Zhao et al., 2015). The validation of this hypothesis shows that firms can reap positive benefits from integrating with upstream partners up to an optimal level, beyond which negative effects of additional integration will start diminishing firm performance. Highlighting the possible negative effects supplier integration might have on firm performance in the form of the inability to adapt quickly to market uncertainty due to costly adaptations to change renders the firm inflexible compared to agile supply chains. Thus, firms must consider the cost and benefit of additional investment and what it does add to the SC not only in terms of efficiency but also in terms of impact on further market share, ability to develop new products or services quicker than competing supply chains, etc. Second, our results did not empirically support the non-linear relationship between customer integration and firm performance. Nonetheless, we did surprisingly find a positive and direct link between customer integration and firm performance.

Previous studies (Huo, 2012; Vickery et al., 2003; Yu et al., 2013) examined the relationship between customer integration and firm performance, but they did not find support for a direct relationship between these two variables. These studies found that customer integration’s effect on firm performance is mediated by customer-based variables, such as customer service (Vickery et al., 2003), customer-oriented performance (Huo, 2012), and customer satisfaction (Yu et al., 2013). Since previous studies have failed to find empirical evidence for a direct relationship between this SCI dimension and firm performance, we sought to answer the call of (Mackelprang et al., 2014) to investigate the unclear link between customer integration and firm performance by studying a non-linear direct relationship between these variables.

Third, our sample data provided empirical support for our moderation hypothesis regarding the role of trust. Our results demonstrate the role trust can play in attenuating the negative effects of extensive integration with SC partners. At higher levels of trust, the firm performance outcomes from extensive integration with suppliers are sustained (Fig.2). Whereas, at low levels of trust, the adverse effects of greater integration with upstream partners will affect firm performance. The plotting of the moderation results further confirms our hypothesis. As a result, firms need to find a balance between the level of supplier integration and trust to maximize the benefits generated in terms of firm performance from extensive integration.

Theoretical Implications

Our findings regarding the effects of SCI on the firm performance, contribute to the literature on SC management and integration debate. We refine existing literature on SCI, by investigating non-linear relationships between SCI dimensions and firm performance and we answer the call of previous studies (Ataseven and Nair, 2017) to explain the inconsistent results of this relationship. Our findings show that SCI has an inverted U-shaped connection with firm performance. In line with earlier research (positive impacts), (e.g. (Terjesen et al., 2012) we claim that there is a linear positive relationship between supplier integration and company performance. However, we add to the existing research by empirically illustrating how excessive investment in upstream integration can harm company performance (please refer to Figure 2). So far, only a handful of studies have empirically explored this relationship (Das et al., 2006; Swink et al., 2007).

From a RV, integrating tightly with suppliers endows the firms with relational rents. When organizations develop collaborative partnerships (relational) with other SC stakeholders in order to gain a competitive edge, these partnerships may also be used to increase SC performance, growth and flexibility. Furthermore, integrating beyond an optimal level opens the firm to the risk of being locked up into a relationship where the possibility of taking advantage of better alternatives is reduced. As integration with suppliers increases, adaptation to environmental dynamism and changing market needs becomes too costly. As a result, instead of adapting quickly, a firm will need to readjust more processes and linkages. Hence, raising the costs of managing the relationship which will impede the firm performance of the firm. Our study partially confirms previous studies’ findings (Flynn et al., 2010; Narasimhan and Kim, 2002)which is the degree to which a manufacturer strategically collaborates with its supply chain partners and collaboratively manages intra- and inter-organizational processes, in order to achieve effective and efficient flows of products and services, information, money and decisions, to provide maximum value to the customer. The previous research is inconsistent in its findings about the relationship between SCI and performance. We attribute this inconsistency to incomplete definitions of SCI, in particular, the tendency to focus on customer and supplier integration only, excluding the important central link of internal integration. We study the relationship between three dimensions of SCI, operational and business performance, from both a contingency and a configuration perspective. In applying the contingency approach, hierarchical regression was used to determine the impact of individual SCI dimensions (customer, supplier and internal integration, concerning the positive effect of supplier integration on firm performance. Whereas the curvilinear relationship between supplier integration and firm performance refines existing knowledge about the integration with upstream partners.

However, our sample data did not support the assertion that customer integration had negative consequences. This can be explained by the difference in market proximity between customer integration and supplier integration. In other words, despite extensive consumer integration, the firm will be able to rapidly adapt to market uncertainty and changing client needs. Indeed, downstream partners represent a source of valuable and critical information that will enhance the performance of the firm (Hamdi et al., 2020). In contrast, being closely linked to suppliers leads to negative effects because of their distance from market information. Hence, our results unexpectedly confirm a positive direct relationship between customer integration and firm performance (Flynn et al., 2010; Huo, 2012), while our curvilinear hypothesis was not supported. We suspect the possible existence of contingencies under which this relationship might shift to curvilinear forms, such as the level of innovativeness and competitiveness of the supply chain.

Third, we posit in our study that the presence of higher levels of trust will offset the detrimental effects of supplier integration. When the market needs change, and coordination costs become higher, a firm can leverage the existence of high levels of trust to share knowledge and readapt the SC with lower monitoring and governance costs. Furthermore, upstream partners will be willing to share valuable and sensitive information given their belief in the firm’s intent not to behave opportunistically. Using arguments from TCE, we consider that developing higher levels of trust will enable firms to reduce transaction costs associated with extensive integration with suppliers. The presence of trust among SC partners allows firms to overcome the inflexibility, and rising costs of coordination, since partners will more readily share information, opportunistic behavior will be curbed and more importantly costs related to the governance of such extensive relationship will be significantly reduced. By investigating trust as a moderator, we do answer the call of Mackelprang et al, (2014) to investigate moderators of the relationship between SCI and performance.

According to Williamson’s (2008) queries addressed to SC management community, TCE is concerned with types of governance structures’ strengths and weaknesses and how they ensure coordination autonomously. This statement by Williamson (2008) principally answers a “What” question regarding types of SC configurations to adopt to minimize all production and transaction costs across the SC. Our study engages the TCE perspective and enhances its analysis of transactions by highlighting the underlying mechanisms that leads to both positive and negative outcomes in SCI as a hybrid structure. Our results, empirically demonstrate the role played by trust in offsetting the increasing transaction costs of adopting hybrid governance (SCI). Indeed, we contribute to the literature by explaining the positive role played by trust by going beyond the opportunism argument to explain the mechanisms that render trust a relational factor central in the management of SCI. Understandably, SC managers are aware of the importance of developing trusting relationships both at the interpersonal and inter-organizational levels to mitigate possible negative effects of increased transaction costs due to higher levels of SCI.

A brief discussion of the influence of control variables is warranted. The results of our control model, show that out of six control variables, environmental uncertainty and supplier relationship duration were found to have a significant impact on firm performance. Our results indicate that the longer the supplier relationship duration the more likely that SCI will generate a higher level of firm performance. This result is not surprising, since the effects of SCI on financial returns tend to be generated over time in the form of cost savings. Also, we found that in contexts characterized by a higher level of environmental uncertainty, firms will gain a higher level of firm performance via the implementation of SCI among its SC partners. Indeed, during uncertain times, information sharing, and joint problem-solving routines will enable SC partners to navigate turbulent times and enhance their firm performance. The effects of size, work experience of SC managers, SC experience, and industry type were found not significant.

Managerial Implications

The findings from this study have important implications for managers from a SC perspective. For instance, the findings imply that firms operating in the USA are more likely to better perform with SCI if they invest in integration with upstream partners to a moderate level. Effective supplier integration within supply chains is critical for some companies to achieve a competitive advantage and growing research demonstrates that the more integrated the SC is with suppliers and customers, the larger the potential benefits (Zailani and Rajagopal, 2005). Thus, demonstrating that SCI can lead at first to positive firm performance and extensive supplier integration will generate diminishing returns. The findings demonstrate the importance of SCI and let us suggest that before trying to increase the level of supplier integration, firms need to study how such level contributes to enhanced firm performance. Based on the data collected from US SC executives, our study recommends that managers consider the possible impact of increased integration with upstream partners on the firm’s behavior. In other words, they should look at the firm’s ability and upstream partners to readapt to changing needs without profoundly impeding the profitability and the firm’s returns. Additionally, as the levels of integration increase, managers should monitor whether all partners are contributing as planned to the SC efforts. For instance, SC partners may disregard certain behavior that would normally be considered unacceptable, such as free-riding but due to history and social harmony, it becomes increasingly difficult to identify since SC partners will eventually contribute to cover for the free-rider. Adding to this, the problem of clash of ideas will be reduced because of groupthink, which may lead the SC partners to miss opportunities to innovate or revamp the value chain operations. Furthermore, firms should consider including and renewing their SC network to keep the competition and the clash of new ideas enduring and beneficial.

Firms must engage in developing higher levels of trust, as it contributes to overcoming the possible rising costs of high levels of upstream integration. At low levels of trust, the costs of too much integration with suppliers will outweigh its benefits. Therefore, managers should seek to build trust. Being SC partners implies an inter-firm relationship. Although, trust precedes the implementation of SCI activities, its existence and nurturing are compulsory to hold the SC partners together, especially during highly uncertain and turbulent times, where speed and effectiveness of reaction is a key element to enhance the resilience of the SC. Supply chains that have lower levels of trust, will incur higher transaction costs to operate and react to such context. Trust acts as an incentive for partners to access accurate and valuable information seamlessly and timelessly and creates the necessary confidence for SC partners to not act opportunistically during hard times. The findings are significant for policymakers in developing countries to compare how in USA the role of trust can enhance both supplier and customer integration, which will result in effective firm performance. To maintain and boost firm performance amongst SC partners, policymakers may encourage proximity and socialization processes and events to support the development of trust and commitment that will be conducive to reducing transaction costs generated by opportunism. It can be realized by creating SC affinity groups which will work on joint operational problem-solving proactively and seamlessly, which will enhance further the financial performance of SC partners. The findings may be utilized to encourage managers in SC to develop trust at various levels by developing strong interpersonal, and inter-relational trust among the SC network.

Conclusion

Our study contributes to the ongoing debate about SCI in two essential ways. First, by anchoring our reasoning and arguments by combining two theoretical lenses RV and TCE, we investigated the positive and negative effects of SCI on firm performance. Our study is one of the few studies to consider studying the adverse effects of SCI on firm performance. We demonstrate how firms investing in SCI, particularly supplier integration, might lead to diminishing returns. Second, we offer a refinement to our findings on SCI and its link to firm performance, by investigating the condition under which firm performance might be sustained under extensive supplier integration. We empirically demonstrate how higher levels of trust positively moderate the inverted U-shaped effect of supplier integration on firm performance.

Our study does have a few limitations that are worth noting. First, we only have considered the effects of the external integration dimension on firm performance, without discussing investigating the effects of internal integration. Future studies should consider the effects of all three dimensions and possible interactions among these variables. Second, we used a single-respondent survey method to collect our data. Although we attempted to mitigate the risk of common method bias, this method will still lack the robustness offered by other methods. Consequently, our results should be understood by considering this limitation. Thus, future studies should attempt to collect data from different organizations and different respondents. Also, we measured the firm performance using subjective measures for the lack of availability of objective data about our sample. Finally, future studies should explore the different contingencies under which SCI might sustain its firm performance returns. For instance, we found that the control variables, relationship duration and environmental uncertainty were found to be significant, we may expect that these variables moderate the relationship between SCI and firm performance. Finally, SCI is a practice that crosses national boundaries and requires the orchestration of SC resources across different cultures. Hence, the influence of cultural dimensions such as uncertainty avoidance, collectivism, and future orientation (Wong et al., 2017), on SCI link to performance will differ between organizations located in the US and other countries. These dimensions will influence the perception of risks, safeguards of the contract, trust among partners. Similarly to the work of (Sacristán-Díaz et al., 2018; Som et al., 2019; Wong et al., 2017)national culture has been a critical component in supply chain management. Yet, our understanding on its role in affecting the performance outcomes of supply chain integration (SCI, future studies should empirically investigate the relationship between SCI and performance by exploring the effect of cultural dimensions and how they enrich the ongoing debate regarding the mixed findings between SCI and performance.

Parties annexes

Appendices

Appendix 1. Recent literature review on supply chain integration

Appendix 2. Constructs and Items

Biographical notes

Ahmed Hamdi (Ph.D): is an Assistant Professor at Rabat Business School of the International University of Rabat, Morocco. He has pursued his PhD from Rennes School of Business, Rennes, France, in Supply Chain Management. His research interests focus on studying supply chain resilience, supply chain integration and relational dynamics in buyer supplier relationships. He has published his work in several international peer-reviewed academic journals including International Journal of Logistics Management, European Business review, Economics Bulletin. Also, he presented his work in leading academic conferences such as Decision Science Annual Meetings, POMS meeting. His teaching interests are oriented towards supply chain management, sourcing and supplier relationship management, and costing issues in supply chain.

Tarik Saikouk is an Associate Professor of Supply Chain Management at Excelia Business School in La Rochelle, France. Professor Saikouk mainly works on issues related to mobilizing social capital, sustainable orientation, and Lean Management practices within the Supply Chain. His publications include research articles published in international journals such as European Management Review, Production Planning & Control, International Journal of Logistics Management, Expert Systems With Applications, and Technological Forecasting and Social Change. He is currently an Associate Editor of the French Journal of Industrial Management, etc.

Bouchaib Bahli is a full professor of Information Technology at the Ted Rogers School of Management, Toronto Metropolitan University, Toronto, Canada. Professor Bahli’s research expertise and interests are around the strategic management of digital transformation, business services automation, risk management of emerging technologies, business analytics and IT outsourcing. Professor Bahli has published in several international academic journals including Information and Management, Journal of Information Technology, Decision Support Systems OMEGA, the international journal of Management Science, International Journal of Production Research and, Transportation Research Part E.

Amitabh Anand is an associate professor at Excelia Business School, La Rochelle, France and an affiliate of Strategic Management Lab, Aalborg University Business School, Denmark, researching ethics and behavioural psychology in management, organization, and entrepreneurship. He has published papers in Journal of Business Venturing, British Journal of Management, Journal of Business Research, International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, Business Ethics, Environment, and Sustainability, etc.

Bibliography

- Aiken, L.S., West, S. G. and Reno, R.R. (1991), Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions.

- Ataseven, C. and Nair, A. (2017), “Assessment of supply chain integration and performance relationships: A meta-analytic investigation of the literature”, International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 185, p. 252-265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2017.01.007

- Autry, C.W., Rose, W.J. and Bell, J.E. (2014), “Reconsidering the Supply Chain Integration-Performance Relationship: In Search of Theoretical Consistency and Clarity”, Journal of Business Logistics, Vol. 35, Nº 3, p. 275-276. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbl.12059

- de Beuckelaer, A. and Wagner, S.M. (2012), “Small sample surveys: Increasing rigor in supply chain management research”, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, Vol. 42, Nº 7, p. 615-639. https://doi.org/10.1108/09600031211258129

- Bode, C., Wagner, S.M., Petersen, K.J. and Ellram, L.M. (2011), “Understanding Responses to Supply Chain Disruptions: Insights From Information Processing and Resource Dependence Perspectives”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 54, Nº 4, p. 833-856. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.64870145

- Callegaro, M., Baker, R., Bethlehem, J., Göritz, A.S., Krosnick, J. A. and Lavrakas, P.J. (2014), “Online panel research: history, concepts, applications and a look at the future”, Callegaro, M., Baker, R., Bethlehem, J., Göritz, A. S., Krosnick, J. A. and Lavrakas, P. J. Online Panel Research: A Data Quality Perspective, p. 1-22.

- Chang, W., Ellinger, A.E., Kim, K.K. and Franke, G.R. (2016), “Supply chain integration and firm financial performance: A meta-analysis of positional advantage mediation and moderating factors”, European Management Journal, Vol. 34, Nº 3, p. 282-295. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221091251

- Chen, D.Q., Preston, D.S. and Xia, W. (2013), “Enhancing hospital supply chain performance: A relational view and empirical test”, Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 31, Nº 6, p. 391-408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2013.07.012

- Chiles, T.H. and Mcmackin, J.F. (1996), “INTEGRATING VARIABLE RISK PREFERENCES, TRUST, AND TRANSACTION COST ECONOMICS”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 21, Nº 1, p. 73-99. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1996.9602161566

- Courtright, S.H., Gardner, R., Smith, T.A. and McCormick, B.W. (2016), “My Family Made Me Do It: a Cross-Domain, Self-Regulatory Perspective on Antecedents to Abusive supervision”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 59, Nº 5, p. 1630-1652. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.1009

- Das, A., Narasimhan, R. and Talluri, S. (2006), “Supplier integration-Finding an optimal configuration”, Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 24, Nº 5, p. 563-582. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2005.09.003

- Doney, P.M. and Cannon, J.P. (1997), “An Examination of the Nature of Trust in Buyer-Seller Relationships”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 61, Nº 2, p. 35. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299706100203

- Dyer, J. and Chu, W. (2003), “The role of trustworthiness in reducing transaction costs and improving performance: Empirical evidence from the United States, Japan and Korea”, Organization Science, Vol. 14, Nº 1, p. 57-68. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.14.1.57.12806

- Dyer, J.H. and Singh, H. (1998), “The Relational View: Cooperative Strategy and Sources of Interorganizational Competitive Advantage”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 23, Nº 4, p. 660-679. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.1255632

- Fabbe-Costes, N. and Jahre, M. (2008), “Supply chain integration and performance: A review of the evidence”, The International Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 19, Nº 2, p. 130-154. https://doi.org/10.1108/09574090810895933

- Fattam, N., Saikouk, T., Hamdi, A., Win, A. and Badraoui, I. (2022), “A new taxonomy of fourth-party logistics: a lexicometric-based classification”, The International Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-02-2022-0051

- Flynn, B.B., Huo, B. and Zhao, X. (2010), “The impact of supply chain integration on performance: A contingency and configuration approach”, Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 28, Nº 1, p. 58-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2009.06.001

- Frohlich, M.T. and Westbrook, R. (2001), “Arcs of integration: An international study of supply chain strategies”, Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 19, Nº 2, p. 185-200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(00)00055-3

- Gerbing, D.W. and Anderson, J.C. (1988), “An Updated Paradigm for Scale Development Incorporating Unidimensionality and Its Assessment”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 25, Nº 2, p. 186-192. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378802500207

- Grewal, R., Chakravarty, A. and Saini, A. (2010), “Governance Mechanisms in Business-to-Business Electronic Markets”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 74, Nº 4, p. 45-62. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.74.4.045

- Hair, J.F., Anderson, R. E., Black, W. and Babin, B. J. (2010), Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.

- Hamdi, A., Saikouk, T. and Bahli, B. (2020), “Facing supply chain disruptions: enhancers of supply chain resiliency”, Economics Bulletin, Vol. 40, Nº 4, p. 1-17.

- Harman, H. H. (1976), Modern Factor Analysis.

- Hill, C.W.L. (1990), “Cooperation, Opportunism, and the Invisible Hand: Implications for Transaction Cost Theory.”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 15, Nº 3, p. 500-513. https://doi.org/10.2307/258020

- Huo, B. (2012), “The impact of supply chain integration on company performance: an organizational capability perspective”, Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, Vol. 17, Nº 6, p. 596‑610. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598541211269210

- Johnston, D.A., McCutcheon, D.M., Stuart, F.I. and Kerwood, H. (2004), “Effects of supplier trust on performance of cooperative supplier relationships”, Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 22, Nº 1, p. 23-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2003.12.001

- Klein, R. (2007), “Customization and real time information access in integrated eBusiness supply chain relationships”, Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 25, Nº 6, p. 1366-1381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2007.03.001

- Leuschner, R., Rogers, D.S. and Charvet, F.F. (2013), “A Meta-Analysis of Supply Chain Integration and Firm Performance”, Journal of Supply Chain Management, Vol. 49, Nº 2, p. 34-57. https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12013

- Liu, H., Wei, S., Ke, W., Wei, K.K. and Hua, Z. (2016), “The configuration between supply chain integration and information technology competency: A resource orchestration perspective”, Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 44, p. 13-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2016.03.009

- Mackelprang, A.W., Robinson, J.L., Bernardes, E. and Webb, G.S. (2014), “The relationship between strategic supply chain integration and performance: A meta-analytic evaluation and implications for supply chain management research”, Journal of Business Logistics, Vol. 35, Nº 1, p. 71-96. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbl.12023

- Malhotra, M.K. and Grover, V. (1998), “An assessment of survey research in POM: from constructs to theory”, Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 16, Nº 4, p. 407-425. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(98)00021-7

- Montabon, F.L., Daugherty, P.J. and Chen, H. (2018), “Setting Standards for Single Respondent Survey Design”, Journal of Supply Chain Management, Vol. 54, p. 35-41. https://doi.org/10.1111/jscm.12158

- Narasimhan, R. and Kim, S.W. (2002), “Effect of supply chain integration on the relationship between diversification and performance: evidence from Japanese and Korean firms”, Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 20, p. 303-323. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(02)00008-6

- Narasimhan, R., Swink, M. and Viswanathan, S. (2010), “On decisions for integration implementation: An examination of complementarities between product-process technology integration and supply chain integration”, Decision Sciences, Vol. 41, Nº 2, p. 355-372. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5915.2010.00267.x

- Nyaga, G.N., Whipple, J.M. and Lynch, D.F. (2010), “Examining supply chain relationships: Do buyer and supplier perspectives on collaborative relationships differ?”, Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 28, Nº 2, p. 101-114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2009.07.005

- Perols, J., Zimmermann, C. and Kortmann, S. (2013), “On the relationship between supplier integration and time-to-market”, Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 31, Nº 3, p. 153-167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2012.11.002

- Pillai, K.G., Hodgkinson, G.P., Kalyanaram, G. and Nair, S.R. (2017), “The Negative Effects of Social Capital in Organizations: A Review and Extension”, International Journal of Management Reviews, Vol. 19, Nº 1, p. 97-124. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12085