Résumés

Abstract

The Business Model is a buzzword that appeared with the famous start-ups. The authors adopt a conventionalist approach to explain its nature. They show that a convention implies a movement that brings into being the entrepreneurial phenomenon, and with it, the seeds of an organization. In real terms, the entrepreneur must go prospecting to convince the owners of the resources he needs for his project to bring them to him, so that he can make an offer of value to the market. They will only join him if they can identify a potential remuneration (both for the offer as a whole and for their own efforts). In other words, the Business Model (BM) is a social artifact that explains organizational impetus, for resources can only be obtained (and hence organized) if a convention is born between the partners. In so doing, the convention makes the entrepreneurial phenomenon observable. In the context of business creation, the BM is this convention. It is, in some ways, a medium for expressing the shared world view of the various stakeholders who will constitute the firm.

Keywords:

- Business Model,

- entrepreneurship,

- Business Creation,

- Organizational Emergence,

- Convention theory,

- Stakeholders theory,

- Resource Based View

Résumé

Le Business Model est un buzzword apparu avec les fameuses start-up. Les auteurs adoptent une perspective conventionnaliste pour expliquer sa nature. Ils montrent que la convention implique un mouvement faisant apparaître le phénomène entrepreneurial, c’est-à-dire la genèse de l’organisation. En effet, l’entrepreneur doit se déplacer pour convaincre les possesseurs des ressources nécessaires au projet d’apporter ces dernières afin de pouvoir fournir une offre de valeur au marché, ce qu’ils ne feront que s’ils perçoivent des perspectives de rémunération (celle de l’offre et la leur). Autrement dit, le Business Model est un artefact social expliquant l’impulsion d’une organisation puisque les ressources ne se réunissent (donc ne s’organisent) que si une convention naît entre les partenaires. Ce faisant, la convention rend le phénomène entrepreneurial observable. Dans le cadre de la création d’une firme, le BM est cette convention. Il est, en quelque sorte, le medium de l’expression de la vision du « monde commun » aux multiples parties prenantes que devrait constituer l’entreprise.

Mots-clés :

- Business Model,

- entrepreneuriat,

- création d’entreprise,

- émergence organisationnelle,

- théorie des conventions,

- théorie des parties prenantes,

- Resources Based View

Resumen

El Business Model es un buzzword que apareció con las famosas start-up. Los autores adoptan una perspectiva convencionalista para explicar su naturaleza. Muestran que la convención implica un movimiento que hace aparecer el fenómeno emprendedor, es decir la génesis de la organización empresarial. De hecho, el emprendedor debe desplazarse para convencer a los que detienen los recursos necesarios al proyecto para que los aporten con el fin de poder introducir una propuesta de valor en el mercado, lo que harán únicamente si perciben perspectivas de remuneración (la de la propuesta y la de ellos). En otras palabras, el Business Model es un artefacto social que explica la impulsión de una organización ya que los recursos se reúnen (y entonces se organizan) solamente si una convención nace entre los socios. Así, la convención vuelve el fenómeno emprendedor observable. En el marco de la creación de una empresa, el BM es esta convención. Es, de una cierta manera, el médium de la expresión de la visión del “mundo común” compartido por los múltiples stakeholders que deberían constituir la empresa.

Palabras clave:

- Modelo de negocios,

- emprendimiento / emprendedorismo,

- creación de empresas,

- surgimiento organizacional,

- teoría de las convenciones,

- teoría de los grupos de interés,

- Resource Based View

Corps de l’article

Entrepreneurship draws upon the multiple meanings of the term « enterprise », which can mean the action of being enterprising, or its business result. Researchers in this domain are interested in both interpretations but they seem to place the emphasis more on the dynamic than on the result, inasmuch as this second meaning need not necessarily take the form of an enterprise as it is commonly understood, ie. a business. There are in fact multiple nascent forms of the entrepreneurial phenomenon: a business, an association, a subsidiary, and even a political party, etc. One can consider these forms, whatever their type, as the organization of resources at the service of a generally collective vision (with reference to Penrose, 1959), even when one actor embodies the project by being the one who carries it forwards. In this paper, our proposition regards the phenomenon that leads the way to the creation of a business.

Thus, to be enterprising is a dynamic or a movement. It is about a collective action that is committed to a process of long or short duration, at the heart of which the resources captured are organized to help a project progress. If the researcher is interested in the organization that springs from the entrepreneurial phenomenon, and so that he might emphasize its dynamic nature, he will treat the question using another term with multiple meanings, notably the one concerning the organization of combined resources. For the term “organization”, as it refers to the enterprise, is ambiguous. According to Desreumaux (1998), the organization designates an entity created to bring about a collective action, the arrangement of this entity and the processes involved having produced simultaneously both the entity and its arrangement. Particular attention is paid to interactions between levels of an organization where individuals are not neglected (Belhing, 1978; Chanlat, 1990). The problems associated with these interactions, and the solutions that are brought to them, are of interest to numerous disciplines and here we adopt a managerial perspective by considering, along with David et al. (2000) that management sciences find their being in the study of collective action; and that this might even be qualified as the science of entrepreneurship (Verstraete, 2000, 2007).

In fact, the action of entrepreneurship is a dynamic collective that holds within it the seeds of an organization. This is a useful terrain to navigate when seeking to realize a vision, the performance of which is measured, on the one hand, by meeting the objectives outlined in a business plan; and, on the other hand, by the clear satisfaction of all the stakeholders concerned (if any one of them is not satisfied, then they will no longer bring their resources to the project). To understand entrepreneurship, one must understand these origins. This paper contributes to such an understanding.

One cannot say that literature on entrepreneurship has neglected to study this theme. For example, with the concept of organizational emergence, Gartner (1985) demonstrates that the act of creation cannot be assimilated into business creation, a topic to which entrepreneurship is sometimes reduced. With reference to the work of Weick (1979), Gartner shows that an organizational dynamic is set in motion before the entity even exists. The aim is to understand how an organization can come into existence. For Gartner (1995), a researcher of entrepreneurship must focus on factors that enable him to answer the following questions: how does an organization start? How, why, where and when do organizations come into existence? Who is involved in this appearance? The final question does not just concern the enterprising individual or team, for it includes the collectivity of people who have undertaken to construct a reality together. This symbolic interaction describes the influence between players and the process of elaborating meaning that comes out of it. The expression Gartner chooses is « emergence », which explains things that become manifest and visible. At the core of the French-speaking community, Verstraete (1997b, 2003, 2005) signs up to the same vein of thinking. He is equally inspired by Weick’s propositions (1979). Verstraete prefers to use the term “impetus”, which encompasses emergence and enables him, on one hand, to insist on the importance of a trigger event and, on the other hand, to consider the development that follows, for the phenomenon can be sustained in a form of unceasing entrepreneurship. This impetus can arrive ex nihilo or it can come from an existing entity. The second case invokes at least two scenarios, namely certain forms of business recovery/take-over or succession that have already been consensually termed “intrapreneurship”, whereby an individual who is not the head of a business takes on an entrepreneurial role for the pre-existing entity that employs him. Remaining within the perimeter of entrepreneurship, the phenomenon emerges on the initiative of an entrepreneur (or an entrepreneurial team). This player is in a symbiotic relationship with the organization for which he provides the impetus, and which precedes the institutionalization of the nascent dynamic entity. The author recalls the theory of conventions to explain the construction of a meaning that comes out of a collective representation shared by the stakeholders who have provided the resources that the project needs (the entrepreneur, the clients, the financers, the employees, etc.).

Here we propose, in a certain way, to give flesh to this convention that is born, develops, and even regenerates itself. Our work is situated at a very “micro” level, as close as possible to the nub of the co-ordination described by Eymard-Duvernay (2006) in a publication devoted to conventions theory.

It is difficult to get any closer to the grain without taking into account the business plan, which could indeed be the flesh, or body, we describe earlier. The business plan is tangible because it is visible, and palpable, given that it takes the form of words laid out on paper for thirty or so pages. It is a document that consecrates all the work undertaken to bring the project this far. It presents the idea, reveals the market, explains the strategy and plans the activity so as to then translate into financial terms both the resources the project needs and the earnings estimates, without neglecting to anticipate the legal institutionalization of the entity, for the business plan proposes a judicial structure for this body corporate that will soon join the world. It allows its readers to understand the conditions in which the project will emerge, by recalling a whole series of elements including, for instance, the motivations of the entrepreneur. The business plan also presents various development scenarios. It often determines the likelihood of the entity taking form because its presence is demanded by certain partners, most notably financers who, without the business plan, would not commit their funds. Despite this, it is no more than a written document that demonstrates, without doubt, a praise-worthy effort made to formalize the project and of which one must recognize the virtues, despite the criticisms of which it can be the object[1]. Even if its writing began precociously early, the business plan still constitutes the completion of a process of continuously updating a business, and not its source. What is more, it is just a physical entity, at the heart of which one must find the economic and social artifact on which the convention is founded. This paper proposes to consider the BM as this artifact. Suffice to declare that some businesses start without presenting a business plan, to confirm that the genesis we are looking for must lie elsewhere.

We can reveal the truth of this statement. Right from the first businesses imagined online, those famous start-ups, one hears of funds that have been raised before the presentation of a business plan. We are really talking about a group interest that comes together around the business proposed, and that witnesses a convention emerge. The real world has given a name to this thing that gives meaning to businesses: it is the Business Model. This terminology has spread widely and rapidly as a buzzword. Neither in research nor in education can the teacher-researcher ignore a concept that has been appropriated in real usage. Our efforts at conceptualization lead us to see the BM as the convention at the heart of both the entrepreneurial project and the business. We will show that the BM constitutes the convention around which a momentum gets under way and develops, and that it is a medium for expressing the “shared world view” of the multiple stakeholders who make up the business. The problem consists therefore – on the one hand – in updating the nature of the BM and, on the other, in showing that it is an integral part of the entrepreneurial phenomenon. The inseparable questions presented in this paper are therefore the following: What is the nature of the BM? When does an entrepreneurial phenomenon appear?

The first part explains that the BM, at its origin, is a search for meaning undertaken jointly by agreement between partners who need to understand the heart of a project before committing to it. This necessity rests primarily on three essential elements, which are the building blocks of the BM: generating value, drawing remuneration from it, and sharing its success with a network of partners by establishing win-win relationships with them. The second part presents the theoretical justifications for the propositions in the first part. If common sense tells us that every project needs partners to bring resources to it so that an offer can be generated and profits can be made, then two theoretical approaches serve to explain the building blocks of the BM: stakeholder theory and the resource-based view. The BM seems to result from a collective crystallizing around a project, at the heart of which is a shared representation of the emerging business. It is then possible to posit a further proposition regarding the nature of the BM. The third part shows that the BM is a convention around which a group of partners will bring the resources that the project needs. Conventions theory is mobilized to explain that this is the nature of the BM. In the last part, we present some theoretical and practical perspectives that follow from the propositions of this paper, without forgetting to point out some of its limitations[2].

The origin and building blocks of the BM

The academic world has studied the BM a great deal in the context of new technologies (Open Source, Peer-to-peer, etc.), as is clear in the work of Gordijn (2002/2003) and Osterwalder et al. (2005); only to move beyond it, to a very large extent. In the first section, we remind readers how the BM appears to sustain a quest for meaning. The next three sections draw on the literature to trace the outline of the BM by identifying its component parts.

The BM: at its origin, a search for meaning

Desmarteau and Saives (2008) cite the first use of the term BM in a text written by Bellman et al. (1957) where it refers to the mathematical modeling of revenue sources in a business simulation tool. The real world took up the expression in a spectacular way with the arrival of the start-ups in the new I.T. and communications sector, and turned BM into a buzzword. Its original accepted meaning, relatively fluid as for all buzzwords, remained attached to the revenue model. We must point out that would-be partners in a project need to understand how revenues will be captured, especially when certain uses of the offer proposed do not necessarily find people to pay for them. According to the principle of market disassociation as summarized by Benavent et al. (2000), it was for instance possible to respond to this problem by enabling one part of a service to be free, whilst another part had a price tag. This is the case with mobile telephones, which are almost free but are linked to a paid subscription service. It was equally possible to resort to policies of versioning as Shapiro and Al Varian (1998) propose; whereby certain clients finance dearly the initial version of a product, making it more accessible and capable of reaching a wide user base.

Upstream of the remuneration of the offer, it is clear that the offer itself must be understood. The offer is what literature on entrepreneurship calls the business opportunity, that is to say the meeting between a business idea and its market. This search for meaning was required by would-be partners of a project who, without understanding the offer and all it could bring them, would obviously not commit their resources to it. An extra effort was therefore asked of the entrepreneur to make the project intelligible where previously it had not been, largely due to the fact that it had no track-record. It was necessary to help partners, in a certain way, to “see” the project. And for that, it was necessary to come up with a model.

Modelization is the exercise by which an object of study is rendered intelligible thanks to a system that enables the object to be seen. The object can be a phenomenon, a situation, an artifact, etc. The model enables a visualization of the object by generating, in the mind of the viewer, a mental image or a representative diagram. The language used to give it its meaning is adapted accordingly. It could take the form of a drawing, a mathematical formula, a text, etc. or it could combine multiple forms. The model is hence a key to the intelligibility of the object. The educational system and researchers rely heavily on this exercise. In the framework of enquiry that interests us here, what must be made clear is the business, and to do that, we need to model it. “Modèle d’affaires” in French, Business model in English, the meaning is simply common sense…

But, more fundamentally, the BM is attached to another usage of the word “meaning”, and that is, its search for sense. It is about understanding the heart of a business and its possible development (the pathway or the direction that the project will take in time). The model must help people to see the project, that is, to see the organization before it exists as a legal entity, as well as its possible evolutions.

We propose to consider the BM as a way for a firm to make its business comprehensible to its various stakeholders. The BM creates meaning through the exercise of modeling.

Seeing as real world usage had taken up the expression, the academic community seized it to conceptualize it and make it intelligible. In other words, it had become necessary to modelize the model itself. For what should one reply to a novice entrepreneur who, over the course of his training, asks his tutor what a BM is, because some of the potential stakeholders he has met have asked him what his was?

The next three sections will take up certain elements from the literature to trace the outline of the BM.

Understanding the revenue model

The previous section evokes the question of remuneration starting with the problem of who are the people who pay. It is not then surprising to see that texts written on the BM are concerned with the revenue model, which goes further than identifying just the sources of revenues. From one author to another, the expressions vary and thus it is sometimes a question of approach (Maitre et Aladjidi, 1999), or of logic (Linder and Cantrell, 2001; Morris et al. 2005), or of mechanisms (Chesbrough, 2003) or of a plan (Kumar et al., 2003) that enable the production of revenues. The variety of terminologies used by these authors hides, in reality, a certain homogeneity of concept. The generic question is the following: how does the business make money? (Petrovic et al., 2001; Magretta, 2002; Morris et al., 2005). Osterwalder places this question in the purchase-sale cycle of the business, the BM being a “representation of how a firm sells and buys good and services and earns money” (2004, p.14), a notion that Warnier et al. (2004) formulate otherwise: “how is the sale or the use of resources remunerated?”. Once the sources of revenue are identified (Timmers, 1998; Morris et al. 2005), to take up the proposal of Dubosson-Torbay et al. (2002), the end result of the BM is to “generate revenue flows that are positive and sustainable” (p.7). It is therefore not only about explaining today’s revenues but also to show how the offer is remunerated in time and how profits are possible, thus reassuring stakeholders about the durability of the project (Rappa, 2000; Afuah et Tucci, 2001; Petrovic et al., 2001). This durability is equally assured by profitable revenues and it is consequently not surprising that the literature reveals the structure of costs and margins as a composite of the revenue model.

We propose to integrate the dimension, “remuneration of value” into the BM. This remuneration is the price paid by markets that are interested in the goods or services proposed. It integrates, as a minimum, the revenue sources, their volumes and an estimation of profits.

To understand the BM, it is all the more necessary to understand the offer. It would be simplistic to assimilate just the remuneration of value into the BM.

Understanding the offer

The literature on the BM speaks of the “value proposition”. The BM must answer some basic questions, such as: who are the consumers (demograhic and geographic) to whom the business offers this value? (Afuah et Tucci, 2001); who is the client? (Magretta, 2002); what is the market segment and to whom will the service, the product or the technology be useful? (Chesbrough, 2003); for whom does the business create value? What is the nature and the size of the market in which the business will enter in competition? (Morris et al.,2005). The BM therefore explains why the targeted client base finds the value proposition interesting and why the business, on this basis, is likely to seize a competitive advantage. Maître et Aladjidi (1999) take up the expression “value proposition” to recognize, from the point of view of the offer, the need to find a client for whom the usage value of the product is higher than the price he pays for it. Osterwalder (2004) opts for the same expression. To take this further, the value proposition must be both understood and acquired. This acquisition relies on the offer being manufactured and effectively proposed by an actor (unique or plural in the case of an entrepreneurial team) who is recognized as legitimate by the system, particularly in his capacity to keep his promise (and so to manufacture what he is offering).

We propose to integrate the dimension, “generation of value” into the BM. This generation unites the entrepreneur (be it one or multiple individual(s), or a business) with the value proposition and the manufacturing of this value.

This generation of value is made possible by the participation of a network that brings its resources to the project.

Chrystalising a network

To believe in the BM, financers need to understand its revenue model and how it generates value. They will ask themselves if the business is capable of inspiring commitment from the resource-holders it needs: in particular from the clients, because they are traditionally the first to participate in the remuneration of value; and more generally from all the people who pay, if we refer to the models of some start-ups; and indeed from all the stakeholders, because of the need to gather resources of various kinds to manufacture the value needed for the offer to be delivered to the market. The creator who does not own all the resources personally must meet resource-holders and convince them to join him. This vision of an organization is not new. Desreumaux (1998) attributes a model of “organizational balance” to Barnard (1938) and Simon (1947). This model places an organization in a dependent relationship with a whole body of partners who receive some kind of reward from the organization, in exchange for what they bring it (eg. a salary that remunerates an employee’s work, a product as payment for clients, etc.). The relationships are sustainable if each partner is satisfied in accordance with his own system of evaluation.

A BM is never conceived independently of the relationships the project needs, i.e. the business network contributes to the manufacture of the offer by the resources it brings. The literature on the BM refers to a value network (Shafer et al., 2005) that contributes to the manufacture of value. The BM evolves through expectations that are met, without ever believing it can integrate them all. Depending on the ambition of the project, during launch as well as in the long-term, what matters is to make a sufficient number of stakeholders commit. Ideal partners do not always commit, but this does not necessarily place the project in danger. However, the quality of the network assembled has an impact on the BM under construction because of the resources it makes accessible. The BM depends therefore on both a consideration of the stakeholders’ expectations and the quality of the resources obtained or promised.

Commitment from the stakeholders invokes a third dimension of the BM, because a potential stakeholder will not hand over his resource unless it is in return for what he can obtain from the relationship of exchange. This sharing dimension requires an exercise of conviction because one cannot expect the resource-holder to have a spontaneous understanding of the model.

We propose to situate the BM in a partner-based vision of value that recognizes a “Sharing” dimension to the BM, meaning that the firm (or another institutional form that has arisen from the entrepreneurial act) shares its success with its partners by convincing them to develop durable “win-win” relationships with it.

The next sections provide the theoretical bases that support the previous propositions.

Using an exercise of conviction with the resource holders

Our propositions lead us to consider that the BM creates meaning for a business and that it comprises three dimensions: the generation of value (entrepreneur, promise and manufacture), the remuneration of this value (sources, volumes, profits) and the sharing of the project’s success with its stakeholders by an optimization of the relationships held with them (exchange and conviction). In so doing, so that the stakeholders, who at the beginning are just resource-holders, commit to the project by bringing exactly the resources expected, it is even more important that they support the model under development. They will not come without demands, and if their needs are not integrated into the BM, then it will have little chance of gaining collective support.

The first section considers that the point of entry of a collectively accepted business rests in a partner-based vision of value. The second section is interested in the core of this conception: namely, the resources concerned.

Entrepreneurship: a partner-based conception of value

A business creator, spearheading an ambitious project, will almost never have all the resources he needs to be entrepreneurial, and he will have to approach the people who own the ones he needs, to try to obtain them. To this end, he uses an exercise of conviction with a view to getting the owner of resources to commit and, in so doing, he transforms him into a stakeholder. One could, here, differentiate between partners who need convincing for the business to launch, and partners who need convincing to ensure its durability. The literature on stakeholders, because it is primarily concerned with established businesses, studies principally the second category, and supports the definition given by Freeman and Reed (1983, p. 91): “Any individual or group on which the survival of the organization depends … any individual or group identified as being able to affect an organization’s realization of its objectives or that is affected by the organization’s realization of its objectives”. Other categorizations have been proposed. For example, Clarkson (1995) defines, in the first instance, the primary stakeholders. They are, in conformity with Freeman and Reed’s definition, necessary to the survival of the organization: employees, shareholders, clients, suppliers, etc. They are held in place by the relationships that the firm establishes between them and by the satisfaction that it knows how to bring them in the long term. In the second instance, Clarkson speaks of secondary stakeholders, which regroups groups of actors who are influenced by decisions made by the firm, or who influence those decisions: pressure groups, media, etc. One could, up to a certain point, interpret his proposition by distinguishing, on the one hand, between the shareholders directly implicated in the cycle of purchase-manufacture-sale and, on the other hand, shareholders who intervene on a more macro level, or who are less directly engaged in the creation of value, even though they can affect it.

The previous proposition maintains one single conception of value, namely that which is proposed to the market. But the literature on stakeholders presents those conceptions as being shaped also by personal goals that might, in part, be reached by their relations with the firm (Donaldson et Preston, 1995). This view considers the firm as a constellation of co-operations and interests combining individual and collective motivations. It holds together by the long-term value that the business knows how to bring to each group (even to each shareholder). If one of the groups is no longer satisfied, then the system can no longer hold together (Clarkson, 1995).

To bring this proposition back to the context of business creation, the inherent dynamic in impelling an organization requires an energy that is nourished by the resource-holders, who must be satisfied in the long term if they are to be maintained in relation to the system that has been built on their energy. The birth and the development of the organization depend on the long-term commitment of these shareholders, and hence on the value that has been – just as sustainably – brought to them. In fact, if the generic value produced needs to meet a market, a value should be singularly brought to the shareholder whose resources are required. The organization is in a relationship of value exchange with each shareholder. A resource with value for the project is expected from the shareholder who will expect, in return, a resource that has value to him. He will even be likely to come back to his partners to offer them more value, just as the business creator does with his stakeholders. Beyond any natural exchange between two partners (eg. a supplier expects a payment for the goods he has delivered), one should be able to optimize the value exchanged to capture the resource needed for the project in a sustainable way (ex. the distributor makes a positive contribution to the image of the goods delivered by the supplier). In other words, one must make the value specific to each category of shareholders (even to each shareholder) and not restrict oneself to the value brought to the market, even if it is a sine qua non condition. This position takes us back to a partnerial conception of value because the genesis of the organization requires relations of exchange with the partners and it is not, concretely, the financer of capital who is at the basis of this network of relationships, even if he contributes to it[3].

A business model built around the value of the resources exchanged

The exchanges between partners rely on the resources that are needed or desired, and their value will condition what one partner expects, compared to what he brings another partner. It should be possible to employ the resource dependency theory of Pfeffer and Salancik (1978) who explain that each actor in an inter-organizational network is in a relationship of power and dependency with the others. His need for resources (work, funds, raw materials, etc.) places him in a situation of dependency with regard to his environment and he must develop strategies to become, himself, the supplier of resources that others need, and thus gain a certain power over them. The strategies are diverse: advertising to make the consumer dependent or at least to influence his buying behavior, diversification of suppliers, etc. This vision of the relations of exchange is deterministic even though the actor can navigate his way through it by understanding the network and hence by managing his relations with it.

The literature reveals other types of theoretical approaches to the question of resources. Efforts at theorization in this domain are heavily nuanced[4] and any attempt to articulate the concepts is a perilous exercise, notably when explaining how a business seizes and develops a competitive advantage. This is not our objective, nonetheless it is possible to retain some elements which have been updated by the authors and which smack of good sense. For example, when it comes to qualifying resources so as to identify them better (and one can only advise an entrepreneur to list the resources necessary for his project), Wernerfelt (1984) speaks of tangible assets (ex. machines for production) and intangible assets (eg. the managerial talent of the decision-makers). Penrose (1959) distinguishes between physical and human resources[5].

Penrose (1959) considers businesses as bodies of resources and services that were formed by these same resources, which condition their evolution. For a business to grow, it must, on the one hand, fix a goal and, on the other hand, organize the resources it holds to reach that goal. We rediscover here the distinction made by Chandler (1962) between strategy and structure. Structure corresponds to the arrangement of resources, whereas strategy is concerned with their capture. Drawing inspiration from the propositions of Barney (1991) and transferring them into a context of business creation, an entrepreneur picks the best resources (resources-picking) so that he can construct the best offer (capacity-building), which constitutes in itself a resource for those who acquire or use it. It is this last element that the shareholders have bet on above all. They have been convinced by the promise of value and by the capacity of the creator-organization to know how to manufacture it. In other words, the shareholders have at the same time understood and committed to the generation of value. They also commit to the remuneration that can be drawn from it (which is obviously a resource in itself, as well) and they expect a resource in return for the one they bring to the project. The durability of the business then depends on the coordination of these resources and the relations of exchange with its shareholders[6]. Finally, the project can only actually take off and survive if the sources do not dry up and the different types of partnership can reach agreement on the business which they are driving forward together.

A conventionalist perspective of Business

The crystallization of stakeholders around a project of business creation is linked to a collective representation that can reach agreement on a way of conceiving the business in its launch phase, i.e. the dynamic sense of the term ‘business’. Various theoretical bodies propose to shed light on collective representations. Without making an inventory of them all, this is the case, for example, with the theory of social representation, which provides an explanation for the construction of a consensual vision of reality that links a subject and an object of representation (see for example, Jodelet, 1989). Closer to our discipline, and more specifically concerned with organizations, is the case of neo-institutional theory, most notably in its expression of sociological inspiration, whereby institutions are seen as cognitive systems combined with regulatory and normative systems (Scott and Christensen, 1995). It is likewise the case with conventions theory, which we have mobilized and which since 1989 has known an important infatuation in the French scientific context. This theory criticizes part of the neo-classical economic theory by revisiting some of its axioms, but it is not our purpose here to redeploy arguments presented in published texts that had that as their objective[7], but rather, in a first section, to retain the most salient elements of the theory that permit us, in a second section, to shed light on both the impetus of an organization and, in a third section, its artifact (the BM).

Conventions theory: an interdisciplinary project for economics

Depending on the researcher’s discipline, the convention can be given a variety of accepted meanings that are semantically linked but which lead to an articulation that can be excessively eclectic. One could start with Law, which creates conventions (eg. in commerce), which themselves create laws (eg. the obligation to execute contracts in good faith). Philosophy offers another perspective, notably with the contribution of Lewis (1969) who relies on game theory to conceive the convention as a co-ordination or balance between agents with more or less divergent interests. Our objective being to get closer to business, our starting point is the discipline of Economics, most precisely in the March 1989 number of the Revue Economique, which places the markers for a research program on the convention. There, the convention is reduced not to a co-ordination that is by nature informative, but to a co-ordination of relationships. One can draw the following elements from this special issue (in particular from its introduction, Dupuy et al., 1989):

The conventionalist approach discusses the neo-classical current in Economics, notably the point at which any actions studied diverge from a framework of pure and perfect competition. It takes positions that are sometimes the strict inverse of this, for example when the exchange of merchandise is not possible without a common framework or a founding convention; whereas neo-classical theory considers that contracting individuals do it of their own free will, without any exterior reference. This common framework relies on some cognitive bedrock which, without rejecting the hypotheses of methodological individualism, considers that free will and what it produces, assimilate a normative strength that authorizes individual actions whilst nevertheless maintaining their subservience to a constraining collective framework. The convention is alterable because the framework can be reviewed. The “micro” and “macro” levels, used by managers in strategic analysis, can also be articulated, and the perspective offered by conventions theory goes beyond the confrontation between Holism and methodological individualism. Individuals take action for themselves or as representatives of a collective or institution in the exchange of essentially collective goods. The corresponding conventions are made up of other forms of coordination that are alien to a market that increases in non probabilistic uncertainty and is incompatible with the principle of utility calculation. So, a first level of conventions (called Conventions2 in Favereau, 1986) permits us to regulate the relationships between individuals, and to coordinate, in so doing, their actions within a limited space of interpretation (Eymard-Duvernay and al., 2006). The choice of these Conventions2 is bound to the context within which the relations are situated (de Larquier and Salognon, 2006). A second level of conventions, Conventions1, exists, which operate in a much larger framework. They are more than rules and constitute evaluation models: they permit us to evaluate Conventions2 and they constitute the most legitimate means of coordination.

For the purposes of our work, it comes out again more widely from a revue of the literature that conventions theory rests on the idea that the actors in a space-time share a common base of knowledge that influences their behavior. This behavior is expressed through the role-playing of an actor who makes a decision in function of a situation not devoid of rules, notably when the situation reproduces itself. This same recurrence permits, through the interactions of the actors, the emergence of a collective representation, inevitably shared, which offers the actor the possibility of interpreting his own action in the context of a reference of behaviors that are commonly accepted in the space-time studied. In fact, at the heart of recurrent situations, the coordination of actors is regulated by beliefs about the behavior of others (Orléan, 1994). Their coordination relies on that which Munier and Orléan (1993) qualify as collective cognitive models. Seen in this way, the convention constitutes a way of adjusting intersubjective behaviors (Gomez, 1994). It is the result of a comparison between individual actions, within which it evolves, and the framework that constrains the subjects (Dupuy et al., 1989). In other words, the actor also decides by mimicry, for this framework, by which he can prejudge the behavior of others, guides him all the more when the situation is less certain and he is undecided.

It is thus that this theory responds to the management of incertitude by leaving to the actor the possibility of determining his own behavior by a combination of motivations or idiosyncratic cognitive capacities, and a more collective and regulated representation; precisely by these comings and goings between individual and system of which his behavior is, as other theoretical positions have no doubt already shown, as much the product as the cause. If the convention is economic, it is also social “because it only exists concretely by the accumulation of imitative behaviors, to which it gives – like a social mirror – their meaning.” (Gomez, 1996, p.145). Behavior is here considered as an action that generates meaning as much for the individual as for those with whom he coordinates (Ughetto, 2006). We find ourselves in that which – along with Weick (1979) – is called symbolic interactionism, but here it has a foundation and a scientific project that is clearly guided by economics, even if the discipline must open up to others to sustain its research program. An interdisciplinarity is required to update the common framework that brings agreement between individuals who are acting out the constitutional convention, the paradigm, the shared meaning, the cognitive model, etc. (Eymard-Duvernay, 2006) so as to understand the coordination of human behavior (Eymard-Duvernay et al., 2006).

The common framework creates the business

This is about understanding how a common framework is born around the way a business is construed, and how, with the support of an action group, such a framework can give birth to a business. The individual, filled with intentions and with a social history imbued in the rules that have forged his life experiences, is aware of the conventions surrounding him. Appreciating this implies understanding that the actors who he meets will commit to his project in function of the conventions that influence their own behavior. In other words, his project must provide meaning, and this meaning takes flesh in the convention that he will bring to life with the convinced actors who join him. This style of convention must deal with other conventions that are already in play in the situations he encounters. One can identify at least three, within which, to a certain extent, the business convention fits:

those that one could qualify as the world of business creation (for example, what must be considered a business plan, in form and content, is a part of this world).

those relative to the career or status of the partner one has met (for example rules relating to the decision-making criteria of a capital risk financer);

those of the sector of activity into which the business is launched (for example, the values of the business leaders of that sector).

With regard to the last point, without necessarily subscribing to conventions theory, the literature has fairly broadly updated the representations, conceptions or values that guide the business leaders of various sectors (for a synthesis, see Desreumaux, 1995). This is to say also that the more the project lends itself to a radical innovation, the longer it will take for the convention inherent in the business to be born. It must, likewise, be easier to witness the birth of a convention around a non-innovative project to which a partner will commit more easily, if only by maintaining his existing behavior. In all cases, the creator will not nourish the illusion that all the parties he meets will commit. More realistically, it is enough for him to unite a sufficient number of partners, even if for some innovative projects the perimeter of the BM should be widened, in particular by integrating actors with sufficient legitimacy to make a norm apparent.

For most projects, the phenomenon of mimicry is expressed in a sort of domino effect with regard to a certain number of representations about what the business is. The first stakeholder in the project is the creator himself, who – as far as his interactions with the actors in the environment around him go – carries the emerging convention and forges it by integrating their expectations so that the business has meaning for its partners. The potential stakeholders he meets are more easily convinced when other parties, before them, have already committed to the project for, beyond a phenomenon of mimicry that should not automatically be trusted, it is these other parties who give meaning to the project. For example, when a capital-risk financer gives his support to a project, his involvement brings meaning for the banker who accordingly grants the loan more easily. Consequently, the nascent convention, by becoming stronger, seems to reduce the perceived incertitude. With regard to the point of departure of this domino effect, it will above all depend on the capacity of the idea to meet its market, that is to say the capacity of the project to meet its clients. This category of stakeholders is obviously essential as it is the closest one to the notion of the market, the offer and business deals.

The business model seen as the convention of a firm

We previously presented mimicry as a sort of training effect which, through new encounters, fine-tunes the shared model of representation around which a network of partners crystallizes. The progressive and iterative process of commitment to a conventional style is handled by the entrepreneur (or the entrepreneurial team). He starts with an idea that he considers has business potential. This business opportunity can only, with reference to a resource-based approach, respond to an offer if the organization of the assembled resources transforms those resources into capacities to do things well, from which point they will be built into real competences. To capture the resources, the entrepreneur convinces their owners that their transfer into an appropriate organization constitutes a good usage of them. This organization, as soon as it is institutionalized by Law (for example in the French context: drawing up the statutes and declaring their existence in an official journal), becomes what is commonly known as a business; but the conventionalist perspective shows that the dynamic was already present upstream (see the emergence and more largely the impetus for business creation presented in the introduction of this paper), in accordance with the multiple meanings of the term, “organization” (see again the introduction of this paper).

But the parties demand counterparty to what they have brought, and they are equally aware of the business’ potential. The BM is formulated from such demands. Not taking them into account isolates the unconvincing entrepreneur and the convention will not take form, or it will dilute. On the other hand, if from the moment the offer is conceived, the entrepreneur integrates and combines it with the expectations of his stakeholders, then they will, as an action group, participate in the effort of creation (Verstraete et Saporta, 2003). In the same vein, the business is what conventionalists call a « convention of effort ». It is not new to review these efforts in the literature. For example, Leibenstein (1982) proposes to view them as a choice of subscription to a collective behavior that has come about from a certain form of peer pressure. The convention hence interprets the participation of one party in a collective effort, his behavior being the likely result of a combination of coercion and mimicry (see Véran, 2006). In addition to the prospect of proposing a convention of effort that promises a certain value to the market, he must keep the promise that he knows how to manufacture this value, that is to say, by developing relevant capacities and competences. This manufacture is only conceivable by the gathering of the resources owned by future partners to whom he must offer something in exchange; and the more value this thing has for them, the higher the chances that they will bring him their resources. Value is relative and the convention of effort resides equally on the marketing of relations of all sorts between the categories of actors committed to this negotiation of exchanges, who have normal behavioral traits that are known and shared, to which each person refers before taking action, in the expectation that the other actors in the market will do the same. Hence the level of uncertainty diminishes. Alongside the conventions of effort, the notion of “conventions of qualification” defines the nature of the relationships between qualified actors (Gomez, 1997). The BM can be integrated into a first convention to which the entrepreneur must ensure the commitment of the partners who own the various resources that are useful or necessary to his project (organisms, institutions or individuals). This convention constitutes the stable but evolving base of the emerging organization. In other words, the entrepreneur creates, initiates or imagines a convention, which is undeniably theoretical at the start, around which the owners of resources will come to agreement as seeing it as a good way to do business, by betting that the project will regulate the exchanges of value in an optimal way, which all the different stakeholders are counting on. A network crystallizes around the BM proposed, which is now a convention, the entrepreneur being the one who impels the corresponding organization that becomes the visible manifestation of the nascent business.

Discussion and research perspectives

To the first question posed by this paper, concerning the nature of the BM, we answer that it is conventional. This convention concerns the use of resources negotiated with stakeholders.

All newborn organizations develop a conventional style progressively. They share this with their whole body of stakeholders, the organization emerging or being impelled by the exchanges of resources established between qualified actors (convention of qualification) who enable the realization of the project (convention of effort). The potential partners of a project of business creation will commit if they can grasp:

How the value is generated, by the understanding of a promise of value realized by the capture and the good usage of resources in an organization conceived for this purpose. The practical questions posed are the following: Who proposes this value? What is it and to whom is it addressed? How is it manufactured?

How this value is remunerated, at least by an explanation of the sources or channels by which revenues come into the business, also by the ambition of the project in announcing the volumes of revenue coveted, and by an estimation of the potential profits (this calculation will require the calculation and structuring of costs). The practical questions posed this time are: how does the remuneration come into the project? In what proportion? For what profit?

How the business will share its success with its partners. Success is not limited to the sharing of financial profits, even though this aspect will interest at least one category of stakeholders (the shareholders). It is, more broadly, the sharing of value at the heart of a convinced network of value. The questions are: Of what nature are the win-win relations between actors and business network? How is the global value singularly shared with each category of stakeholder, and even with each individual stakeholder?

The main theoretical difficulty is in the use of the resource-based view, for at least three reasons. The first lies in the existence of multiple approaches to the question of resources, each of which has its own nuances. The second is in the ambiguity of the term resource, which is sometimes considered as an input positioned with other inputs, to which organizational capacities add value; and sometimes considered as the competences which have been built on this know-how. The third is not specific to the RBV and concerns the three theories which – like nearly all general theories – have been conceived for existing firms and not for the context of their emergence. All researchers in entrepreneurship face this difficulty, which becomes more important when faced by a new object of research.

Despite those difficulties, our propositions (see part 1) and the theoretical bases we chose (see part 2) permit us to propose the following definition, which sums up our theory of the BM:

The business model is a convention that relates to the generation of value, the remuneration of this value and the sharing of the success of the firm.

Our conception leads us to speak of the GRS model (Generation, Remuneration, Sharing).

One of the theoretical contributions of the above definition is to situate value within the analysis of conventions, as a positive response to Eymard-Duvernay (2006). Value is central to our conception of the BM. For discussion about the value at the heart of the BM, see Verstraete et Jouison-Laffitte (2009) whose point of departure is a conference led by the philosopher Comte-Sponville, at a Management congress in Nantes in 1998 (Comte-Sponville, 1994, 1998). When it comes to the “S”, it should equally be possible to speak of the sharing of value from the point that it is made relative to each shareholder, that is to say to that which he expects from his relationship with the firm. Entrepreneurship is fundamentally partner-based; businesses that are focused on shareholder value would do well to remember that the origins of business lie in enterprise.

To the second question posed by this paper (When does an entrepreneurial phenomenon appear?), according to the perspective offered by the biological metaphor of the life cycle, some authors maintain that the starting point for creating a business is the important risk taken by the individual initiating the project. This could relate to the renting of a factory or offices, or resigning from a job to devote himself to the project, etc. (Adizes, 1991). In this last case, one can speak of trigger events, which might be positive – for example the identification of an opportunity which the creator then wants to exploit, or negative – for example being fired from a job and so becoming interested in starting a business to reintegrate into professional life (Cooper, Dunkelberg, 1986; Feeser, Dugan, 1989; Amit, Muller, 1994). This trigger event leads to a significant change in the life path of the individual (Bruyat, 1993) or that which Shapero (1975) calls displacement/dislodgement. In our view, this movement is essentially made manifest by the would-be entrepreneur’s meeting with the actors who own the resources needed by the entrepreneurial project, in which we include those useful for fine-tuning it (for example the cognitive resources offered by an advisor or by a training program). It is by these means that the phenomenon emerges or, more broadly, that it is impelled. Seen like this, the phenomenon is only eventually visible, observable and made manifest by the actions driven forwards by the would-be entrepreneur, who uses an exercise of conviction to bring the resource-holders with him. In doing so, he nourishes a convention that is coming to life between the project’s partners. The BM is the artifact of this movement, this engaging of the phenomenon and, as he goes on his way, of this fine tuning of the entrepreneurial project by an intersubjectif adjustment, and the creation of a common framework between the partners. The expression BM is welcome because it expresses, from a real world point of view, this search for meaning that is fundamental to a business.

The theoretical contributions arising from the questions asked in this paper open the way to an exploration of other problems, which they do not solve. Here are some examples that could lead to some action-research initiatives that link theory to practice.

We are interested in the appearance of an entrepreneurial phenomenon that corresponds to the birth of a business, which is to say to the birth of an organizational dynamic and its result. It is therefore tempting to post another generic question that distinguishes between the end of the dynamic, and the end of its result. It is not the object of this paper to consider it but we would also like to invite future reflections on the dilution of a convention or its replacement by another. This questions more precisely two aspects of the possible or certain end of a business. First, does the mimetic phenomenon express itself in the same way when the shareholders disengage, and if so, how? In some cases, one could study the behavior of stakeholders who continue to sustain a project in which they find something to gain, despite its apparent difficulties. Secondly, is it possible to regenerate the BM to, in some way, bring the convention back to life? The response to this second question asks a third one. Upstream of any eventual difficulties, does the development of a business require anticipating and integrating the regeneration of the BM[8]? The competitive game, at the heart of which a mimetic phenomenon can become manifest, imposes rules on which the conventionalist approach can shed light. Other theoretical approaches have exposed this, notably in the context of particularly high-speed environments. In this case, according to Moorman and Miner (1998), one must be able to demonstrate organizational improvisation, notably, this time with Yoffie et Cusumano (1999), when the environment is very volatile and when the potential for business growth is high. This improvisation is expressed by a particular talent for knowing how to lay out resources differently to prepare for the unexpected. Thus, any changes are cadenced. They are not provoked by constraining events or alarming declarations (eg. a drop in earnings, a new competitor, etc.) but are anticipated and made rhythmic by a tempo (Brown et Eisenhardt, 1997). In the context that interests us, the entrepreneur is the actor who sets the tempo, on the basis of his capacity to improvise, and to configure resources in a relevant way, and so to regenerate the BM (Benavent et al., 2000). Any experience in accompanying entrepreneurial projects reveals that, in all cases, that is to say even in environments that are less unpredictable, it is not unusual for the BM to evolve, notably when new projects are imagined and the resulting diversification leads the organization to regroup a portfolio of activities. It seems to us, without having worked on it directly, that we are here touching on the limits of the BM. It is relevant on the level of activity (secondary strategy) but perhaps less so on the level of primary strategy, from the moment when the business’ portfolio of activities regroups its diversified activities. This is a problem for strategy researchers to tackle. The BM must not run the risk of becoming a hold-all concept, and as is often the case, being flayed by conservatives for whom caution is quite understandable, given the fashions that sweep through strategic management. But it would be a shame not to benefit from contributions with a broader managerial perspective, as we noticed in the context of business creation where a doctoral thesis has permitted an awareness of its operationality (Jouison, 2008).

Concerning possible managerial contributions, research on the BM offers many possibilities and we would like to present some of the ones developed by our research team, which shares a praxeologic vision of management science. It is a matter of showing that the BM is not a fashion. Its conceptualization turns out in fact to be operationally transferable, establishing thus a bridge between strategy and operations.

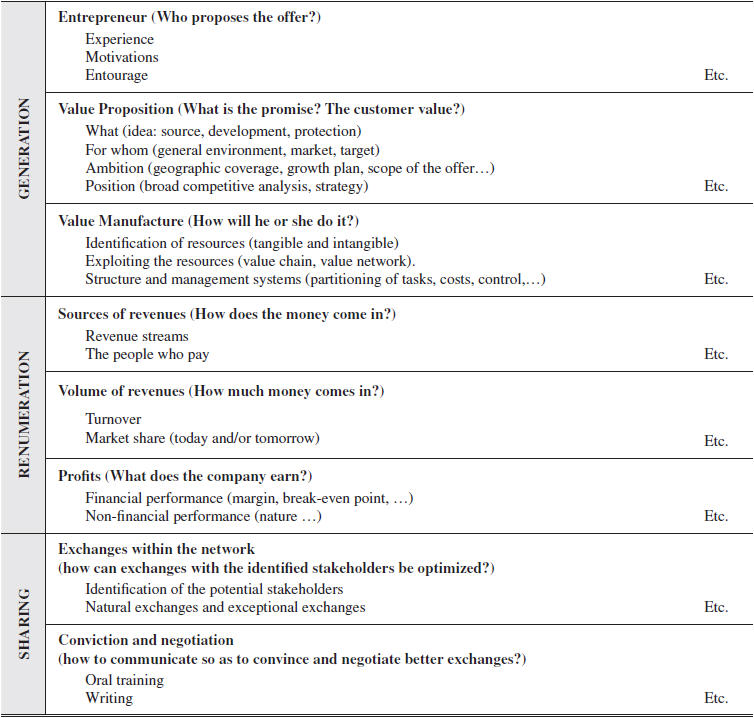

Our initatives in the context of accompanying business creation, in cooperation with organisms like the business incubators and technopoles, led us to propose Table 1. It picks up broad sections of interest to all the disciplines of management science, along with points that need working on to optimize the chances of a project becoming this convention without which the would-be entrepreneur remains isolated. The representation which allows us to ‘see’ a BM is based on the various categories of table 1, in accordance with the papers we have published, and others in progress, and using the case study method. It is particularly important for a pedagogical exercise (explanation of the concept to students or to entrepreneurs) or for an exercise of conviction (presentation of a project to a financer, for example to raise funds) to show the BM concretely (text, graphic, etc.).

Table 1

The themes to work on in the development of a BM

To the extent that the business convention includes a share of agreements between actors, the business creator will gain by preparing his project based on categories for which he must more or less explicitly find harmony with his partners. Table 1 can help him. This table is the point of departure for the valorization of our research work for the advisor in business creation. The advisor will encourage his clients to fill out the categories in this generic grid by using the right tools, at the right moment[9]. He is equally well placed to complete the specific details of the project (hence the “etc.” in each cell of the table where the content is not complete). Software is being conceived which will enable the creator and his advisor to keep in touch, online, during the fine tuning of the project. This effort to formalize things constitutes the premise of all that will be written in the business plan, but above all it enables users to benefit precociously from the emancipatory character of writing.

The word ‘emancipatory’ is here used in the sense of Audet (1994), who used it to discuss the possibilities offered by cognitive mapping (in summary, the map helps ‘see’ and, in doing so, suggests ideas). This technique could aid reflections on the BM, just as other research has shown its potential in the development of the strategic vision of the manager in a cognitive, strategic approach (Laroche and Nioche, 1994; Cossette, 1994; Verstraete, 1997a; Cossette, 2003). One must distinguish here between the BM and its representation in the entrepreneur’s mind. One way of producing a graphic representation of the BM would be to conceive of a composite map (cf. Bougon et Komocar, 1994), which identified common elements in the different representations made by participants in a social movement. The entrepreneur’s representation could take the form of a mental map, i.e. a diagram corresponding to the idiosyncratic vision he has of his BM. Of all the stakeholders participating in the construction of a BM, the entrepreneur is the one with the most complete representation of it (often after a stage of maturity). This does not mean he has a complete representation (but he nearly does). There is a difference between the BM and the entrepreneur’s representation of it. The chart in Table 1 categorises these concepts and analyses the map, and even compares different maps.

This grill is at the heart of various other works that have been realised or are in progress.

One of these works is a research-intervention in established businesses. It is about revealing the BM in businesses run by young leaders in the buildings sector. In the framework of a University Chair - one of the donators of which is the French Buildings Federation (la Fédération Française du Bâtiment) - once awareness has been spread about the concept of the BM and its usage, the project consists more precisely of working on the regeneration of the BM with a sample group of young business leaders who are ambitious for their firms. In the diagnostic phase, a research team was divided into three commissions to gather the appropriate materials for completing the respective dimensions G, R and S. For example, for the R dimension (remuneration), whilst remaining focused on the sources of revenues, their quantity and associated profits, and without falling into a financial audit so as to keep to a model that would be accessible to a non-expert in finance, precisely what information should be collected (aside from information on the turnover and profit)? In this sector, with regard to non-financial performance, what criteria should one be aware of (this can have relevance in the context of responses to invitations to tender)? Then, each of the six pairs of researchers worked with the leader of the firm, on the one hand, to make the BM apparent (a completed research stage) and, on the other hand, to imagine its regeneration (a stage of research in progress).

Another program dealing with business recovery or takeover is being led by an ongoing Doctoral thesis. Numerous people wanting to sell their business cannot find buyers, and too many buyers do not find sellers. The reasons are various but, according to Bouchikhi (2008), this assertion is essentially the result of an asymmetry of information that renders the conditions for recovering SME’s opaque. The concept of the BM seems to us to be able to play a key role in reducing the asymmetry of information, if one manages to put the buyer and seller in relation with one another, around it. This involves working on one question: how can the entrepreneurial potential of an SME that is for sale, be maintained and developed?

A fourth channel of research, equally compelling, concerns the use of the BM in the relationship between a business leader and her advisor. Here, the thesis in progress examines the search for the recovery of meaning. This search appears most obviously in entrepreneurship pedagogy, which is difficult to present so near the end of this paper, except to detail that a method based on our conceptualization has been developed, and that more than 6000 students have so far been trained in the campus of Aquitaine.

Even if the BM was not at the heart of her research, Servantie, in her thesis presented in July 2010, mobilized the concept to understand the precocity and the velocity of internationalization in what literature calls INV (international new ventures), Born global, etc. She speaks about Early and Fast Internationalized Firms (EFIF) to include the various conceptions without confusing them. The GRS grill was used as a methodological tool to collect, analyze and report the cases of EFIF in a systematic way. The results gave explanations on the precocity and the velocity of the internationalization through the propositions formulated for each dimension of the BM.

This list of research propositions is evidently not exhaustive.

We can add here a study of the relations between a particular nascent business convention and a convention that is tending to become more general. For example, in the domain of music, what is the relationship between the BM of a business like Deezer.com or Jiwa.fr (no longer active) and the model (or models) for diffusing music? In another domain, that is to say digital libraries, what is the relationship between the BM of Cyberlibris and the book sector[10]? Then, when it comes to a company diffusing music, should it continue to burn and distribute CDs? Should it consider charging for downloads? Should it distribute music for free, from a website? … It is as if the BM for one company needs to deal with a more general model about how to do business.

Sometimes, this happens by dint of propositions, notably innovative ones. In any case, the BM, when seen as a convention, fits into other conventional styles that should be taken into account, because the actors evolving there are susceptible to taking part in the business envisaged. In this sense, the BM is made up of a body of rules, whilst being a collectively built business convention. Sometimes, it must incorporate specifications that are largely imposed. This is the case when the model developed is submitted to larger conceptions of how business should be done, because of the market leaders’ values and behaviors, or because of the technologies available, or changes in consumption habits, etc. (the concepts of conventions 1 and conventions 2 may be used here).

Conclusion

The Business Model (BM) is a social artifact that explains organizational impetus, for resources can only be obtained (and hence organized) if a convention is born between the partners. In so doing, the convention makes the entrepreneurial phenomenon observable. In the context of business creation, the BM is this convention. It is, in some ways, a medium for expressing the shared world view of the various stakeholders who will constitute the firm. The entrepreneur is the architect of the BM. He combines the knowledge and the materials (the resources) necessary to build it.

Conventions theory has brought a great deal to the conceptualization of the BM which, in return, shows how this theory possesses a praxeological character that one might not have immediately guessed. Management sciences have the virtue of wanting to serve an action, and so take part in showing theories of organizations, equally, that the non-integration of the genesis of organizations will amputate the understanding of an organization’s evolution. Without believing that the BM is a sort of DNA of the organization, and without lapsing into a determinism that is often contradicted by research into entrepreneurship, it can explain the inertia that is characteristic of businesses’ evolution. The BM also takes part in a theory of entrepreneurship, where the theory joins the practice of individuals searching, with reason, for the intelligibility or fundamental sense of the business they are driving forwards, which they create and about which they ask themselves questions. Finally, the theory has reached the heart of the matter, it is enough to reach out and grasp the theory from the people studied, and the things they are looking for. The BM is this theory, that is to say, this meaning. For its business is meaning about the meaning of business.

Parties annexes

Biographical notes

Thierry Verstraete is full Professor at the University of Bordeaux. He is the Chairman of the Entrepreneurship Chair/Department (see the website http://www.bmpe.net) of this University where he is also the Director of the research team in Entrepreneurship. He is in charge of various pedagogical programs in this domain.

Estèle Jouison-Laffitte is Professor at the University of Bordeaux. She is a member of the research team in Entrepreneurship of this University. Her research is on Business Model. She is interested in qualitative methods (action research). She teaches various subjects: entrepreneurship, accountancy, marketing...

Notes

-

[1]

For a full discussion of the business plan, see Gumpert (2002); see also the recent synthesis of Dondi (2008).

-

[2]

French version of this paper : Verstraete, Jouison-Laffitte, 2010.

-

[3]

A bridge can be built here between the domain of entrepreneurship and the field of business governance, where the creation of value is an important theme, and where it has been recognised that history leads us towards a partnerial conception of value (Hirigoyen and Caby, 1998; Caby, Hirigoyen, 2005; Charreaux and Desbrières, 1998; Barredy et al. 2008).

-

[4]

To take this further, the reader may consult, for example, Priem and Butler (2001), and a chapter that Desreumaux and Warnier (2007) dedicate to Barney where they construct – more broadly – a reflection on the Resource-Based View (RBV).

-

[5]

In one particular conception of resources, Barney (1991, 1995) adds organizational resources to these (see also Barney and Hesterly, 2006). Resources in this sense constitute capacities for doing things well, and the firm will define itself, precisely, by what it knows how to do (Grant, 1991).

-

[6]

This will be the role of management policies in the day-to-day running of the business (a buying policy to optimize relationships with suppliers, a salary policy with employees, etc.). It is clear that our use of the word optimize (and its declensions) moves substantially away from conceptions that permit the calculation of probablized risk, or the belief in an optimizing behaviour in the neo-classical use of the term.

-

[7]

See the special edition of the Revue Economique of March 1989, or, in the English language, Gomez et Jones (2000) in Organization Science, or, further, the two volumes recently coordinated by Eymard-Duvernay (2006).

-

[8]

The regeneration of the BM can also relate to cases of business recovery.

-

[9]

For example, if the environment appears fixed then an approach using Key Success Factors would be relevant, but in a changing environment one might use the resource-based view.

-

[10]

Laifi (2009), from another research laboratory, explores this case from a neo-institutional perspective, and uses the concept of legitimacy to understand how Cyberlibris manages to legitimise its innovative BM (for not all BMs are innovative). In our team, we remain with the conventionalist approach.

Bibliography

- Adizes, I. (1991), Les cycles de vie de l’entreprise – diagnostic et thérapie, Paris : Les éditions de l’organisation.

- Afuah, A. et C.L. Tucci (2001), Internet Business Model and Strategies: text and cases, Boston : McGrawHill.

- Amit, R. et E. Muller (1994), “Push and pull entrepreneurship”, Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research.

- Audet, M. (1994), Plasticité, instrumentalité et reflexivité, in Cossette (dir), Cartes cognitives et organisations, Presses de l’Université de Laval, Ed Eska (réédité en 2003 aux éditions de l’ADREG, http://www.adreg.net).

- Barnard C.I. (1938), The functions of the executive, Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

- Barney, J.B. (1991), “Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage”, Journal of Management, 17: 1, p. 99-120.

- Barney, J.B. (1995), “Looking inside for competitive advantage”, Academy of Management Executive, 4, p. 49-61.

- Barney J.B.et W.S. Hesterly (2006), Strategic management and competitive advantage, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Barredy C. Boucher T, Verstraete T. (2008), « Le contrôle de l’entreprise naissante par son créateur : un regard par les théories de la gouvernance d’entreprise », Revue du Financier, 170, mars-avril, p. 9-18.

- Belhing, O. (1978), “Some problems in the philosophy of science of organizations”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 3, n° 2, p. 193-201.

- Bellman R., Clark C.E., Malcolm D.G., Craft C.J., Ricciardi F.M. (1957), “On the Construction of a Multi-Stage, Multi-Person Business Game”, Operations Research, Vol. 5, n° 4.

- Benavent C., Verstraete T. (2000), « Entrepreneuriat et NTIC - construction et régénération du Business-model », dans Verstraete T. (dir.), Histoire d’entreprendre – les réalités de l’entrepreneuriat, Caen : Editions Management et Société.

- Bougon M.G., Komocar J.M.,(1994), Façonner et diriger la stratégie. Approche holistique et dynamique, in Cossette P. (dir), Cartes cognitives et organisations, Presses de l’Université de Laval, Ed Eska (réédité en 2003 aux éditions de l’ADREG, http://www.adreg.net).

- Bouchikhi H. (2008), « Vers l’émergence d’un marché de la PME », in Bouchikhi H. (dir.), L’art d’entreprendre – des idées pour agir, Les Echos – Pearson – Village Mondial.

- Brown, S.L., et K.M. Eisenhardt (1997), “The art of continuous change: linking complexity theory and time-paced evolution in relentless shifting organizations”, Administrative Science Quaterly, Vol. 42, 1997, p. 1-34.

- Bruyat, C. (1993), Création d’entreprise : contributions épistémologiques et modélisation, Thèse de doctorat en Sciences de Gestion, Université de Grenoble.

- Caby, J., et G. Hirigoyen (2005), Création de valeur et gouvernance de l’entreprise, Paris: Economica.

- Chandler, A.D. (1962), “Strategy and structure: chapters in the history of the industrial enterprise”, Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Chanlat, J.-F. (1990), Vers une anthropologie de l’organisation, in Chanlat, J.-F. (éd.), L’individu dans l’organisation, Québec : Les Presses de l’Université Laval, St Foy, p. 3-30.

- Charreaux, G., et P. Desbrières (1998), « Gouvernance des entreprises : valeur partenariale contre valeur actionnariale », Finance Contrôle Stratégie, 1: 2, p. 57-88.

- Chesbrough, H.W. (2003), Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology, Boston: Harvard Business School Press Books.

- Clarkson M.B.E. (1995), “A Stakeholder Framework for Analysing Corporate Social Performance”, Academy of ManagementReview, Vol. 20, n° 1, p. 92-117.

- Comte-Sponville A. (1994), Valeur et vérité, Paris: Presses Universitaire de France.

- Comte-Sponville A. (1998), Philosophie de la valeur, dans Bréchet J.-P. (dir), Valeur, marché, organisation, Actes des XIVe Journées nationales des IAE, tome 1, Nantes.

- Cooper, A.C. et W.C. Dunkelberg (1986), “Entrepreneurship and paths to business ownership”, Strategic Management Journal, n° 7.

- Cossette P. (dir) (1994), Cartes cognitives et organisations, Presses de l’Université de Laval, Ed Eska (réédité en 2003 aux éditions de l’ADREG, (www.adreg.net).

- Cossette P. (2003), « Méthode systématique d’aide à la formulation de la vision stratégique : illustration auprès d’un propriétaire dirigeant », Revue de l’Entrepreneuriat, Vol. 2, n° 1.

- David, A., A. Hatchuel, et R. Laufer (2000), Les nouvelles fondations des sciences de gestion, Paris : Vuibert, p. 193-213.

- Desmarteau A.H., Saives A.L. (2008), Opérationnaliser une définition systémique et dynamique du concept de modèle d’affaires : cas des entreprises de biotechnologie au Québec, XVIIe Conférence de l’AIMS, Nice-Sofia-Antipolis.