Résumés

Abstract

This paper presents the results of the first empirical reception study on the deliberate non-subtitling of L3s in the multilingual TV series Breaking Bad. Multilingual films and TV series are on the increase both in terms of success and penetrating wider audiences in a global market. This puts the focus on how multilingualism is conveyed to the audience and how audiences respond to it. While the translation strategies used in multilingual productions have received some attention, audiences’ reactions to them have only been investigated through an analysis of comments posted on an online movie message board. This study presents the results of a survey on the perception of and response to non-translation of L3 segments in a multilingual prestige TV series among hearing viewers. It shows that audiences are not only acutely aware of deliberate non-translation but also actively seek to identify motivations for it, which are context-sensitive and largely coincide with the filmmakers’ motivations for this practice. On the translation-theoretical side, this paper suggests that Corrius and Zabalbeascoa’s (2011) framework for the translation of L3s in dubbing would benefit from a supplement for other translation modes. On the applied side, the findings of this empirical reception study can inform agents in the international film and TV industry about audiences’ viewing preferences and potentially change AVT practices.

Keywords:

- audiovisual translation,

- multilingualism,

- subtitling,

- non-translation,

- reception study

Résumé

Cet article présente les résultats des premières recherches empiriques sur la réceptivité du public de la non-traduction délibérée de L3 dans la série télévisée multilingue Breaking Bad. Les films et séries multilingues connaissent un succès grandissant et touchent des publics de plus en plus larges sur le marché mondial. Ceci permet de mettre l’accent sur la façon dont le multilinguisme est transmis au public et la réaction de celui-ci. Alors qu’il existe quelques études sur l’utilisation de stratégies de traduction dans les productions multilingues, les réactions du public relativement à ces stratégies ont seulement été observées par l’analyse de commentaires postés sur un forum de discussion cinéphile en ligne. L’étude qui suit présente les résultats d’un sondage sur la perception de la non-traduction de passages en L3 dans une série télévisée multilingue de prestige auprès des spectateurs de même que la réponse qui lui est faite. Elle montre que le public est non seulement conscient de ces non-traductions délibérées, mais qu’il cherche aussi activement à en identifier les motivations, qui sont contextuelles, et coïncident en grande partie avec les motivations des réalisateurs. D’un point de vue théorique, cet article laisse supposer qu’étendre le modèle de Corrius et Zabalbeascoa (2011) pour la traduction des L3 dans le doublage à d’autres modes de traduction serait bénéfique. Du point de vue de l’application, les résultats de ces recherches empiriques sur la réceptivité du public permettent d’informer les agents de l’industrie cinématographique et télévisuelle internationale des préférences des spectateurs, et de potentiellement changer les pratiques de TAV.

Mots-clés :

- traduction audiovisuelle,

- multilinguisme,

- sous-titrage,

- non-traduction,

- réceptivité du public

Resumen

Este artículo presenta los resultados del primer estudio de recepción empírico sobre la no subtitulación de L3 en la serie de televisión multilingüe Breaking Bad. Las películas y series de televisión multilingües tienen cada vez más éxito y están llegando a un público cada vez mayor en el mercado mundial. Esto permite centrar la atención en cómo el multilingüismo se transmite al público y cómo el público reacciona frente a él. Mientras que existen algunos estudios sobre las estrategias de traducción utilizadas en las producciones multilingües, las reacciones del público frente a estas estrategias se han estudiado únicamente a través de un análisis de comentarios publicados en un foro de discusión cinematográfico en línea. El estudio presentado en este artículo analiza los resultados de una encuesta sobre la percepción de y la respuesta frente a la no traducción de partes en L3 en una serie de televisión multilingüe de prestigio por parte de espectadores oyentes. El estudio muestra que el público no solamente es consciente de estas no traducciones intencionadas, sino que también trata de identificar activamente las razones, las cuales generalmente dependen del contexto y coinciden con la decisión de los cineastas. En cuanto a la teoría de traducción, este artículo sugiere que sería beneficioso que el modelo de Corrius y Zabalbeascoa (2011) de la traducción de L3 en el doblaje se hiciera extensivo a otros modos de traducción. Con respecto a la aplicación práctica, los resultados de este estudio empírico permiten informar a los agentes de la industria cinematográfica y televisiva sobre las preferencias de los espectadores, y potencialmente cambiar las prácticas de TAV.

Palabras clave:

- traducción audiovisual,

- multilingüismo,

- subtitulación,

- no traducción,

- estudio de recepción

Corps de l’article

Es gibt dreierlei Arten Übersetzung. Die erste macht uns in unserm eigenen Sinne mit dem Auslande bekannt; […] weil sie uns mit dem fremden Vortrefflichen mitten in unserer nationellen Häuslichkeit, in unserem gemeinen Leben überrascht und, ohne daß wir wissen, wie uns geschieht, eine höhere Stimmung verleihend, wahrhaft erbaut.

Goethe 1820/1960: 307[1]

1. Introduction

Although recent years have seen an increase in research on the translation of multilingualism in audiovisual (AV) texts (Heiss 2004 and 2014; Bartoll 2006; Bleichenbacher 2008 and 2012; Corrius and Zabalbeascoa 2011; O’Sullivan 2011; de Higes Andino, Prats Rodríguez, et al. 2013; de Higes Andino 2014; Zabalbeascoa and Voellmer 2014; Sanz Ortega 2015), research on the more specific subject of non-translation/non-subtitling[2] is still limited (Mingant 2010; Bréan 2011), despite its topicality and relevance. The same is true for reception studies (Díaz Cintas and Neves 2015: 5), whose number and coverage is equally limited (Karamitroglou 2000; Fuentes Luque 2001; Antonini, Bucaria and Senzani 2003; Remael, de Houwer and Vandekerckhove 2008; Antonini and Chiaro 2009; Pablos Ortega 2015), even though the need for them has long been recognized (Gambier 2003; 2006). This need arises from the fact that audiovisual products are made for an audience, and audiovisual translation (AVT) is a service (Chiaro 2008) in which the source and target audiences should receive (roughly) the same quality of service. The development towards more precise audience targets furthermore has consequences for language transfer (Gambier 2006) in that more viewers with more varied socio-demographic backgrounds have varying expectations that should be met. The importance of reception studies thus lies in achieving a high-quality AV product that meets the expectations and needs of increasingly differentiated groups of viewers.

The present study thus addresses two research gaps: first, AVT research on multilingualism, and second, audiences’ reception of multilingualism in AVT products. The only study we are aware of that targets the same gaps is Bleichenbacher’s (2012) investigation of the reactions of viewers to multilingualism in movie dialogues as expressed on an online message board. Unlike Bleichenbacher’s, the present study is based on empirical data collected through an online survey including responses to 12 multilingual scenes from the TV series Breaking Bad[3] (henceforth BB).

The aim of this study is to produce the first systematic analysis of hearing[4] viewers’ opinion on, and perception of, the (non-)translation of multilingualism, using BB as an example. More specifically, we focus on the viewers’ perception of deliberate non-subtitling, and their opinion on why filmmakers implement this practice. With this aim in mind, the following research questions are addressed:

What is the audience’s attitude towards non-subtitling?

How does non-translation affect the way viewers experience multilingual AV texts?

Why do viewers think passages are left untranslated?

Information on these core questions is supplemented with background information on

the importance viewers attribute to multilingualism in AV texts;

their awareness of how it can be/is rendered;

interrelations between viewers’ awareness of how multilingualism is rendered in AV texts and individual factors (such as preferred translation mode, multilingualism) and national viewing practices (e.g. dubbing vs. subtitling country).

This article is divided into six sections. Section 2 surveys the literature on translation strategies available for multilingual AV products. Section 3 describes the study design and the rationale behind it. Section 4 presents the results of the empirical reception study, which are then discussed in Section 5. The final section presents a conclusion and outlines ideas for further research to be conducted in this emerging area.

2. The translation of multilingualism in audiovisual texts

2.1. Languages and agents involved in the production of multilingual audiovisual texts

The languages used in a multilingual AV text are:

L1 – Source language (SL), the main language of the AV source text (ST).

L2 – Target language (TL), i.e. the language the ST is translated into.

L3 – Any ST language in addition to L1 that makes the AV ST a multilingual one.

We define an L3 as any variety of a language that is not intelligible to L1 speakers who are not bilingual in L1 and L3.

Filmmakers who choose to include dialogue in more than one language in their AV text are faced with the issue that any dialogue in L3 is potentially incomprehensible for part of the audience (Bleichenbacher 2008: 173). A decision then has to be made (between the filmmakers, scriptwriters, dialogue directors, translators, distribution companies, etc.) (Sanz Ortega 2015) on how to deal with these L3 dialogue sections. The available options include: self-translation, liaison interpreting, voice-over, full or part intra- or interlingual subtitles, and non-translation with or without indicating the L3 in brackets. L3 dialogues in the original version of BB are part-subtitled (O’Sullivan 2011), i.e. some utterances are subtitled, and some are not.

When translating a multilingual film, there are two basic translation options available for conveying the multilingual character of the ST: to mark language diversity or not to mark it (Bartoll 2006). Linked to Venuti’s (1995) concepts of domestication and foreignization, which capture the effect of the translation strategy, de Higes Andino, Prats Rodríguez, et al. (2013: 139) summarize the translation techniques available for subtitled multilingual AVT products as follows.

Figure 1

Continuum of translation techniques for subtitled multilingual films

In most cases, whether or not to provide a translation for a given L3 ST utterance is a decision made by the filmmaker or distributor (Mingant 2010: 718; de Higes Andino 2014: 135-136). If no instructions are given by the filmmaker/scriptwriter, the decision on whether and how to mark the multilingual character of the ST can be subjective (or driven by economic considerations) and down to the individual dialogue writer/director, the translator, or the distribution company (Chaume 2012: 42; Sanz Ortega 2015: 168). In practice, this means that the same issue can – and most likely will – be resolved differently for each multilingual AV product (de Higes Andino, Prats Rodríguez, et al. 2013; Heiss 2014). One of the advantages of this study is that the authors have explicit evidence of the instructions provided by the creators of the series and how they were dealt with by the German subtitling company that adapted BB for the German market[5],[6]. In the next section, we discuss how and why multilingualism can be marked or neutralized in AV products.

2.2. Unmarked and marked language diversity

Not marking multilingualism means that all L3 ST utterances are translated into an L2. This is generally assumed to render L3s invisible in the translated AV text. We present a more differentiated analysis below.

For dubbed AV texts, marking L3s could be done by providing subtitles, together with the original soundtrack. Language diversity in a film can also be marked through liaison interpreting or self-translation, and the use of words and expressions that can be easily understood (e.g. cognates). With regard to subtitling, language diversity can be marked using one of the following techniques: through the use of intralingual subtitles; interlingual subtitles with marked font types, e.g. colour or italics; or non-subtitling (Bartoll 2006).

Non-translation, i.e. leaving L3 passages untranslated, can either be seen as a translation strategy (de Higes Andino, Prats Rodríguez, et al. 2013: 136), as the absence of a mode of translation (de Higes Andino 2014: 135), or as a translation operation which leaves the L3 ST unchanged (Corrius and Zabalbeascoa 2011: 120). For dubbing, which is the main translation mode the latter two authors consider in their systematic survey of translation strategies/operations for L3s in multilingual AVT products,[7] this means that non-translation of L3 ST sections becomes a case of unmarked language diversity if the L3 of the ST coincides with the language of the target text (TT) (e.g. L3 ST = Spanish and L2 = Spanish; Operation 8: L3 ST/TT = L2; L3 TT status lost; possible results/effects: L3 invisibility/standardization; ibid.: 126). If the L3 in the ST does not coincide with the language of the TT, the multilingualism in the ST remains marked in the TT (e.g. L3 ST = Spanish and L2 = Chinese; Operation 6: repeat L3 ST = L3 TT, L3 TT status kept; ibid.). We would like to argue that in subtitled AV texts, by contrast, the “standardizing” effect of non-translation is weaker if the L3 of the ST coincides with the L2 of the TT, because the viewers of the subtitled AV text can be reasonably expected to appreciate language variation (L1 vs. L3 in the original and L2 vs. L3 in the translated version) through the audio track. If the ST L3 does not coincide with the language of the TT (L3 ST ≠ L2), non-subtitling of L3 ST segments retains the other-language status of the L3.

The literature on this topic, though sparse, mentions various reasons for non-translation. Not translating an L3 ST utterance can, for example, be a decision made for quantitative reasons, that is, the language in question is not frequently used in the ST (Díaz Cintas 2011: 220), or the L3 utterance is of short duration (Bleichenbacher 2008). Kozloff (2000: 81), Şerban (2012: 45), Mingant (2010: 717) and Bleichenbacher (2008 and 2012) have pointed out that this can emphasize the otherness of the L3 characters, and potentially generate a negative image of them. Another reason for untranslated dialogue can be the lack of importance of the L3 for plot development (Baldo 2009; Díaz Cintas 2011: 220). An utterance may furthermore be left untranslated if its meaning can be deduced from other semiotic systems available in multimodal texts, e.g. from the information conveyed through the image (Díaz Cintas 2011: 220). Further motivations for non-translation are the linguistic similarity between one or more L3 expressions and their equivalent in L1 (ibid.), or the target audience’s perceived ability to understand the untranslated utterance due to their L3 knowledge (Vermeulen 2012: 299).

Non-translation in both the ST and the TT can, however, also be an artistic option, i.e. a choice deliberately made by the filmmaker for a specific purpose, or with the aim of creating a certain effect. One such purpose might be to create suspense (de Higes Andino 2014: 108; Sanz Ortega 2015). Deliberate non-translation of L3 utterances can also give rise to the situational realism of a true-to-life communication situation, or a form of emotional realism (Wahl 2005; Mingant 2010: 717-718). If a film or scene is narrated from the perspective of characters who do not understand the ST L3(s), non-translation puts the viewers in the position of these characters. They understand as little as they do and have to guess the meaning of the L3 utterances by interpreting facial expressions, gestures, context, and other semiotic devices. A possible consequence is that viewers will empathize with those fictional characters who cannot understand the L3 (Bleichenbacher 2008: 181; Mingant 2010: 717; de Higes Andino 2014: 108). Paulsen (see note 5) calls this a “subjective camera” effect.

The absence of subtitles may also reflect the filmmaker’s ideological point of view and his or her attempt to ideologically position the audience. For instance, non-translation may aim to make the corresponding utterance comprehensible only for certain sections of the audience and to create “a layer of intimacy in the film to which only the initiated are admitted” (Longo 2009: 106). Similarly, as pointed out by Mingant (2010: 717), non-translation is often used to create exoticism.

In the following section we present a reception study that investigates viewers’ opinion on, and perception of, the (non-)translation of multilingualism in BB.

3. Reception study: the (non-)translation of multilingualism in Breaking Bad

3.1. Corpus description

This study is based on the third season of BB because for this season, the original scripts with the authors’ instructions regarding part- vs. non-subtitling are available on the Internet. BB is a US crime drama television series created by Vince Gilligan, who is also the head writer and executive producer of the show and directed five of its 62 episodes[8]. Set in Albuquerque, New Mexico, BB is about the descent of man (Olmstead 2012: 5). With emotional realism it tells the story of Walter White, a chemistry teacher who, in a desperate attempt to secure his family’s financial future after being diagnosed with advanced lung cancer, decides to team up with his former student Jesse Pinkman to produce and sell methamphetamine. BB portrays the cat-and-mouse game between Walt, Jesse, and their mostly Spanish-speaking adversaries. Although generally referred to as crime drama, the series also includes elements of the thriller, contemporary western, and black comedy genres[9].

BB was originally broadcast on American Movie Classics (AMC) between 2008 and 2013. While still a local, non-mainstream show by the time the third season was about to air in 2011, BB has won numerous awards, and is now considered to be the highest-rated show of all time (Segal 2011[10]; see also note 9).

The language used in the show is mostly informal and colloquial. Style and register, however, vary considerably, depending on the social and educational background of the characters[11]. One of the series’ linguistic characteristics – and that of most interest for the purpose of this study – is its multilingual nature. Apart from English, the show’s main language, BB includes dialogues in Spanish, German, and Chinese. The series’ multilingualism is related to its setting, a region where Hispanic influence is particularly strong, and the role that organisations of Hispanic origin play in the international drug trade. The Chinese- and German-speaking characters in BB are also involved in the production and distribution of the chemicals that make up methamphetamine.

For the purpose of this study, 12 multilingual scenes in their original English version were extracted from the seven episodes of season three that contain instances of multilingualism. Out of these 12 scenes, five are of particular interest for the present study because they contain instances of non-subtitling; they are located in SE03E01[12] (‘No Mas’), SE03E07 (‘One Minute’), SE03E08 (‘I See You’), SE03E11 (‘Abiquiu’), and SE03E13 (‘Full Measure’). The clips used in the survey were taken from the last four scenes and complemented with one scene from ‘Sunset’ (SE03E06).[13] ‘No Mas’ was excluded because it was considered too long. With the exception of ‘Full Measure’ (SE03E13), where one of the ST L3s used is Chinese, all non-English utterances in the multilingual scenes of the corpus are in Spanish. In the corpus material used in this study, the only AVT mode is subtitling, and all instances of non-translation are cases of deliberate part-subtitle use (O’Sullivan 2011). For the focus of this paper it is important to highlight that the English original and German target version of BB are identical with regard to the central aspect under investigation; those parts of L3 passages which are deliberately not subtitled in the original are also left unsubtitled in the target version. In O’Sullivan’s (2011) terms, those utterances that have no pre-subtitles in the original do not have post-subtitles in the target version for the German-speaking audience either. This is why we can treat responses from English- and German-speaking participants alike.

All clips were made available on the cloud storage platform Google Drive via a link in the survey (see note 13). A table summarizing the duration of the multilingual scenes, characters involved, subtitling instructions from the original scripts, and assumed motivations for non-subtitling can be found under the same URL.

3.2. Research method and study design

This empirical study is based on an online survey. Respondents were asked to answer 18 questions made available on a website, four of which were linked to the clips discussed in the previous section. This method was chosen for three reasons.

First, questionnaires are suitable to collect data for initial explorations of new topics, such as the main issue under investigation in this study, i.e. viewers’ perception of and opinion on the practice of deliberate non-subtitling in multilingual AV texts.

Second, surveys allow for a mixed-methods design in which quantitative data can be collected through closed questions while more in-depth qualitative information is gathered through open-ended questions. In 12 of the questions (3, 3.a, 4-7, 9, 11, 12, 13, 13.a, and 13.b) respondents could choose among several options suggested by previous research (see Section 2.2). For the central research question, the motivations for deliberate non-subtitling, this quantitative approach was combined with two open-answer questions (8 and 10, see section 3.3 for questionnaire design). The free-text responses were analyzed using thematic analysis (Boyatzis 1998; Clarke and Braun 2013). All open-answer questions were independently analyzed by both authors of this paper using qualitative data analysis software (NVivo). This software supports qualitative and mixed-methods research through flexible management, retrieval, and comparison of thematic coding/codes, i.e. conceptual labels relevant to the research questions and applied to sections of data.

Third, online surveys are cost-efficient means of collecting accurate data rapidly and on a large scale. The questionnaire was implemented via the Bristol Online Surveys platform and completed anonymously. The link to the survey was published on forums for BB fans and on Facebook, and sent by email to potential viewers of the series. 81 questionnaires were returned within 14 days. All 81 questionnaires were complete and thus valid for data analysis. Since sufficient socio-demographic information about the target audience of BB is available (e.g. age, educational level; see Section 4.3), careful conclusions regarding a broader audience can be drawn from the survey results.

The following section describes the way the online survey was designed and the rationale behind its structure.

3.3. Questionnaire design

The idea behind the survey design was for respondents to start completing the questionnaire with a “clear mind,” i.e. without preconceived ideas about the topic, and have them think about the use of deliberate non-subtitling as they go through the questions.

The questionnaire (which can be found under the same URL as the clips, see note 13) is composed of five thematic groups: 1) you [i.e. the respondent] and BB, 2) the (non-)translation of multilingualism, 3) motivations for non-subtitling, 4) dubbing vs. subtitling, and 5) personal data, comments and feedback.

Question 1 establishes how familiar the respondents are with BB, which enables us to weight the participants’ background knowledge about the series and its multilingual character. Questions 2-7 and 14 (thematic group 2) deal with the subject of (non-)translation of multilingualism, both in general terms and with regard to different clips showing instances of multilingualism and non-subtitling in BB. This set of questions aims to establish respondents’ opinion on the importance of multilingualism and its rendering in the series. The last question in this block (Q 14) rounds up the topic of non-translation and captures the respondents’ thoughts “under the spell” of the clips they have just watched and the questions they have just answered.

Closed question 9 and open-answer questions 8 and 10 form the core of the questionnaire, as they address the main research question of why viewers think certain parts of multilingual scenes are not translated. In question 9, respondents are asked to rate seven possible reasons for non-subtitling in terms of likeliness. Potential motivations were sourced from the literature (see Section 2.2). In questions 8 (based on the clips used in questions 3, 4, and 7) and 10 (based on two new clips) respondents are asked to state why they believe the creators of BB chose not to provide subtitles for certain parts of scenes involving L3s. Questions 8 and 10 ask the same question before (Q 8) and after (Q 10) the respondents are confronted with potential motivations for non-translation sourced from the literature review (Q 9). The rationale behind this structure was to first encourage respondents to generate reasons for non-subtitling of their own accord (based on the clips they had just watched; Q 8), before they are presented with stimuli from the literature. The comparison between participants’ answers to questions 8 and 10 allows us to assess whether the motivations provided in question 9 triggered new ideas, and how much participants’ responses depended on the context, i.e. on the different clips.

Questions 11 to 13 centre on the topic of dubbing/subtitling. Personal data about the respondents’ gender, age, and linguistic knowledge is collected in questions 15 to 17. In the optional question 18, participants have the opportunity to provide feedback on the questionnaire and make additional comments.

The survey investigates participants’ attitudes towards (non-)translation of multilingualism and their understanding of motivations for non-subtitling through mixed-methods research. It does so against background information about participants’ socio-demographic profile, their familiarity with BB, their personal preferences in terms of translation modes, and how they were shaped by national traditions. The design of the questionnaire thus covers the main research questions and relevant background information (for potential limitations, see Section 6). Hence the results, i.e. the information provided by the respondents (see Section 4), provide a first systematic picture of an audience’s preferences of and opinions on deliberate (non-)translation of L3s in an AV text.

3.4. Profile of survey respondents

The survey generated a total of 81 responses. 55/81 (67.9%) respondents were familiar with the series. Out of these, 43 (53.1%) had watched the entire series, two (2.5%) had watched most of it, and ten (12.3%) had viewed one or more episodes. 26 (32.1%) respondents had watched the clips from the series included in the survey. All responses were considered, but the focus of our discussion is on the 55 responses from BB viewers; they are assumed to provide more informed views because of their background knowledge about the series and its multilingual nature (see Section 3.3).

The majority of the survey respondents are female (58%). Respondents’ ages range from 19 to 66. The largest group is between 20 and 29 (44.4%); 37% are between 30 and 39, 3.7% 40 to 49, 8.6% 50 to 59, and 4.9% 60 years or older. One respondent (1.2%) is younger than 20. The audience targeted by the channel that originally broadcast BB (AMC) consists of adults between 25 and 54 years of age (Downey 2008).[14] Downey, however, notes that the median age has gone down to just under 50 years with shows like BB. The age profile of our participants therefore closely matches that of the general BB viewer.

Another important aspect of the survey respondents’ profile is their linguistic knowledge and biography. Dewaele and Wei (2014) have shown that people who speak more than one language and have grown up or work in an ethnically diverse environment have significantly more positive attitudes towards code-switching, a change in language within a conversation as illustrated in the clips. We therefore assume that respondents with this linguistic profile will have more positive attitudes towards multilingualism and non-translation than monolinguals. Respondents are speakers of Spanish, Catalan, Chinese, Croatian, English, German, Hungarian, Italian, Japanese, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, and Swedish. The vast majority of the survey respondents (92.6%) speak at least one additional language besides their mother tongue. 47 (58%) speak more than one second language, which indicates a generally high level of education. Beck (2013)[15] points out that BB and other “prestige TV” series differ from more traditional shows in that their distributors target educated professionals, rather than the largest possible audience. In Germany, BB was broadcast on ARTE, a channel “whose mission is to provide cultural programming”[16] – a rather uncommon choice for a popular American TV series. These observations are furthermore supported by Erik Paulsen (see notes 6 and 11), dialogue director of the German dubbed version of BB, who confirmed that the show was primarily addressed to a well-educated audience. The educational level of our participants thus also matches that of the target audience of BB.

The following section, a presentation of our survey results, shows that our findings are very much in line with these observations and developments. We will discuss the implications of our results and how they relate to previous research in more detail in Section 5.

4. Results

This section presents the survey findings in thematic groups. Comparisons are made between related results from different thematic groups. Conclusions and possible implications that can be drawn from them are discussed in Section 5.

The most important aspect of this study is the participants’ perception of and opinion on the practice of deliberate non-subtitling against the background of (a) the most common AVT mode in their country of origin, and (b) their personal preferences. This information will therefore be presented first.

4.1. National traditions and personal preferences: dubbing vs. subtitling

According to Table 1, nearly two-thirds of the total number of respondents (50/81 or 61.7%) come from a country where the prevalent translation mode is dubbing. 24 (29.6%) come from subtitling countries, and four (4.9%) from voice-over countries. Three participants named specific combinations of AVT modes, such as dubbing with occasional foreign accents, under “Other.”

Table 1

Prevalent translation mode in respondents’ country of origin (Q 11, no. (%))

Considering that the majority of respondents come from dubbing countries, such as Germany, France, Italy, and Spain, it is noteworthy that an overwhelming majority of 68/81 (84%) respondents prefer subtitling, while only 13/81 (16%) favour dubbing. More specifically, as can be seen from Table 2 below, 80% of respondents from dubbing countries prefer subtitling, but of the 24 respondents from subtitling countries, only two (8.3%) prefer dubbing.

Table 2

Personal preferences (Q 2) vs. national translation traditions (Q 11)[17]

Respondents’ general preference for subtitling over dubbing may also be reflected in question 13.a. (Table 3), where they agree (96.3%) that it makes the series more realistic and/or the characters more authentic if the multilingualism of the original is kept and non-English parts are subtitled instead of dubbed. While not as clear-cut as the responses to question 13.a., a large majority (79%) is of the opinion that untranslated L3 parts enhance the series’ realism and/or the authenticity of the L3 characters (Q 13.b.).

Table 3

Impact of (non-)subtitling on realism of series/authenticity of characters (Q 13.a. and b., no. (%))

These results suggest that the use of multiple languages and the marking of this language diversity through non-subtitling is not only accepted but even appreciated by a large proportion of the target audience. They furthermore support Bleichenbacher’s (2012) and Heiss’ (2004) suggestions that viewers of a certain educational and linguistic background particularly disapprove of the loss of plausibility/realism caused by linguistic homogenization. What these results potentially tell us about the survey respondents and comparable audiences is placed in its wider context in Section 5.

4.2. Non-subtitling of L3s

Questions 2 to 7 and 14 address multilingualism in BB, how multilingualism is rendered in the series, and what viewers think of it.

Table 4 shows that of the 55 participants who were familiar[18] with BB, 25 (30.9%) think that multilingualism plays a very important role in the series, 23 (28.4%) believe it plays an important one, and eleven (13.6%) think it is at least somewhat important. Nobody considered multilingualism to be unimportant for the series.

Table 4

The importance of multilingualism in BB (Q 2, no. (%))

Question 3 explores whether the respondents want the multilingualism of the original to be kept in AV texts, or if they think that all L3 utterances should be dubbed or subtitled (Table 5). The question is linked to a 35-second clip (306_Sunset_Scene 1; see note 13 for a full listing of details on which clip is associated with which question and the URL under which they can be accessed), which features a conversation between two English (L1)-speaking and two Spanish (L3)-speaking characters in a restaurant. The first part of the conversation is in English (L1); when the bilingual restaurant owner addresses the Spanish (L3)-speaking characters in L3, the conversation is subtitled. Table 5 presents the quantitative results of question 3.

Table 5

Keep the multilingualism of the original or translate all L3 utterances (Q 3, no. (%))?

A large majority of 64 respondents (79%) prefer the multilingual character of the ST to be retained in the TT. That is, they prefer translation strategies that maintain the multilingual character of AV source texts. For dubbed AV products these strategies include subtitles with the original soundtrack, self-translation or liaison interpreting, and the use of words and expressions that can be easily understood. With regard to subtitling, language diversity can be retained through inter- and intralingual subtitles or non-translation (see Section 2.2). All participants who are in favour of maintaining language diversity in multilingual AV products prefer L3 utterances to be subtitled rather than dubbed (Q 3.a.). If we compare the responses to questions 3 and 12 (Table 6), we notice an interesting discrepancy: 11 of the 13 respondents who generally (i.e. without the context of a clip) prefer dubbing over subtitling are in favour of keeping the multilingual character of the original when asked in the context of a clip. This means that, in context, 11/13 respondents are willing to accept subtitles and/or non-subtitling for the L3 ST utterances, instead of having all dialogue dubbed. One possible reason for this discrepancy may be that, because of national traditions and/or personal viewing preferences, traditional dubbing audiences are not usually confronted with the choice between “all dubbed” and original soundtrack with/without subtitles. Only when pulled out of the dubbing comfort zone and confronted with marked language diversity through a “foreignizing” translation strategy (Venuti 1995; see Figure 1) can and do viewers make an informed choice between foreignizing and domesticating translation strategies, i.e. marked and unmarked language diversity. If this hypothesis is correct, this finding presents the first concrete empirical evidence that distributors may underestimate what dubbing viewers are willing to accept in the case of multilingual AV texts (de Higes Andino 2014), and that the “widespread practice of trying to meet the presumed expectations of the target audience [with regard to “easy viewing,” not reading subtitles, linguistic homogenization] is misguided consideration of the target audience on part of the AVT industry” (Heiss 2004: 213). We will return to this point in Sections 5 and 6.

Table 6

Keep multilingualism/translate everything (Q 3) vs. personal translation preference (Q 12)

Question 3.a addresses only those respondents who prefer to have everything translated. When asked what kind of translation they prefer for the L3 ST utterances, they could choose between the following options:

All dubbed: All L3 ST utterances should be fully dubbed into the TL (L2).

All subtitled: All L3 ST utterances should be subtitled, including those that were not pre-subtitled (O’Sullivan 2011) in the original version.[19]

All dubbed + foreign accent: All L3 ST utterances should be fully dubbed into the TL (L2), but L3 characters are dubbed into L2 with a non-L2 accent.

The result was unanimous – all respondents selected “All subtitled” (Q 3.a); even the two participants who generally prefer dubbing to subtitling (Q 12) agreed. The results of subquestion 3.a thus tie in with those presented in Table 6 to show that, in the context of a clip, our respondents are willing to accept subtitles for L3 ST utterances, instead of having all dialogue dubbed. A more detailed discussion and interpretation of these combined findings is presented in Section 5.

Question 4 addresses the core question of this study as it deals with the absence of subtitles and the respondents’ opinion on it. This question is related to a clip (311_Abiquiu_Scene 1) that features a conversation between two bilinguals, a young woman and her grandmother, in the presence of one of the monolingual main characters, who does not actively take part in the interaction. The first part of the conversation is in English; when the girl’s grandmother gets visibly upset and switches to Spanish, this part of the dialogue is not subtitled. When participants were asked what they thought of the absence of subtitles (Q 4), the vast majority selected “I like it” or “I think it’s OK” (64/81 or 79%); only 17/81 (21%) did not like it (see Table 7).

Table 7

Attitudes towards non-subtitling (Q 4, no. (%))

Table 7 shows that 79% of the participants either liked the complete absence of subtitles for L3 utterances or found it acceptable; only 21% would have preferred a translation. This finding supports the idea that audiences with a similar profile to our respondents are positively inclined towards non-subtitling and thus in favour of maintaining linguistic diversity in multilingual AV products.

Table 8 compares participants’ attitudes towards non-subtitling (Q 4) with their preferred translation mode (Q 12).

Table 8

Non-subtitling (Q 4) vs. personal translation preference (Q 12)

Table 8 shows that participants who generally prefer subtitling to dubbing either like or accept the absence of subtitles (51/68 or 75%). In the group that generally prefers dubbing, slightly more than half of the respondents (7/13 or 53.8%) like the absence of subtitles. The rest of that group think it is okay. The answers to question 4 thus again tie in with the more general results presented in Tables 6 and 7 and show that even respondents who generally prefer dubbing over subtitling are in favour of keeping the multilingual character of the original when asked in the context of a clip (Table 8).

Questions 5 and 6 seek to establish whether respondents think L3 ST parts should be dealt with differently depending on the duration and importance of a given scene. With regard to the duration of a scene (Q 5), 40/81 (49.4%) chose “Yes,” while 41/81 (50.6%) chose “No.” Opinions are less divided with regard to the importance of a scene involving an L3 (Q 6). 51/81 (63%) respondents think that the importance of a scene to the plot should influence the translation strategy adopted for multilingual sections involving an L3; 30/81 (37%) do not think so. The illustration provided for question 6 in the questionnaire furthermore suggests that scenes involving main characters should be fully translated, whereas parts of scenes that only involve supporting characters could be left untranslated. This result is the first in our series of findings that highlights the importance of main characters and the plot for audiences of multilingual AV products. We will return to this point in the discussion and conclusion.

Question 7 addresses what de Higes Andino (2014: 447) explicitly identified as a gap in the research paradigm: which cinematographic codes in subtitled multilingual films help viewers deduce the meaning of untranslated scenes.

This question (Q 7) is linked to video clips from two different episodes containing four non-subtitled utterances each. The first clip (308_I See You_Scene 2) features a telephone conversation in English between two bilingual characters. When the sound of people intruding into his house distracts one of them, he switches to Spanish. His nervous shouts in Spanish are left unsubtitled. The second clip (313_Full Measure_Scene 1_2) involves a monolingual English (L1)-speaking hitman, a Chinese (L3)-speaking woman and the bilingual (L1 + L3) owner of the chemical plant where the scene takes place. Two turn sequences in L3 are left unsubtitled: when the Chinese-speaking woman apparently begs the English-speaking hitman for her life, and when the bilingual owner of the chemical plant has to ask the Chinese woman on behalf of the hitman if she is still there. The whole question-answer sequence in Chinese between the owner of the chemical plant and the Chinese woman is left unsubtitled.

66/81 (81.5%) of the survey respondents claim they were able to tell what the non-subtitled L3 ST parts are about. This is remarkable, given that only 37 (45.7%) of the respondents list Spanish as a language they are familiar with, and only one respondent speaks Chinese (Q 17). This means that 35% of our respondents state they were able to tell what the untranslated utterances in the clips are about without having any knowledge of the L3s involved in the scenes. We will discuss the implications of this finding in relation to the literature (Sanz Ortega 2011) in Sections 5 and 6.

Those participants who are able to follow the untranslated scenes are then asked to identify what helped them to deduce their meaning. Respondents can select multiple answers to this follow-on question (7.a.). The available options are situational “context” (e.g. plot), “visual clues,” “linguistic knowledge,” and “other (please specify)” (Figure 2).

Figure 2

What helped viewers deduce the meaning of untranslated utterances (Q 7.a., no. (%))

The most interesting result of question 7.a. is that only 28 (42.4%) of the 66 respondents who claim to have understood what the unsubtitled L3 ST utterances in clips 308_I See You_Scene 2 and 313_Full Measure_Scene 1_2 are about selected linguistic knowledge. This is particularly notable given that 38 respondents indicate active knowledge of Spanish or Chinese, i.e. the ST L3s used in these clips (Q 17). Consequently, 10 respondents (only three of whom qualify their knowledge of Spanish with “little”) do not think their knowledge of the ST L3s used in the clips facilitates their understanding of the unsubtitled utterances. These respondents predominantly select context (5) and other sources (e.g. tone (respondent (henceforth R) 7), visual elements (R 12)). One participant (R 77) stresses that she understands one of the ST L3s (Spanish), but notes that she would have understood the general idea of the scene even if she did not speak the language. Overall, a total of 63/88 (95.5%) of the survey respondents state that the context of the scene helped them understand what the unsubtitled sequences are about. Context is thus selected more than twice as often (63 vs. 28) as an aid to understanding unsubtitled sections than linguistic knowledge.

What is even more surprising is that in question 7, seven participants who speak Spanish (Q 17) indicate they cannot tell what the untranslated L3 turns in these scenes are about. The results on linguistic knowledge and its role in deducing the meaning of untranslated turns are so surprising that they are in dire need of an explanation, which we will offer in Section 5.

Furthermore, 34 (51.5%) respondents selected visual clues; this number includes the three respondents who name aspects related to facial expression and gesture in the open-answer section of this question. Participants’ responses to question 7 thus suggest that both context and visual clues are more helpful for construing the meaning of untranslated sequences in clips 308_I See You_Scene 2 and 313_Full Measure_Scene 1_2 than linguistic knowledge. The finding on visual clues goes in the direction of studies that suggest that up to 93% of meaning is conveyed through non-verbal channels (Mehrabian 1972). The findings of this study are currently under scrutiny and the role of non-verbal information for meaning-making clearly also requires further investigation in the context of non-translation in multilingual AV products (Taylor 2013; Pérez-González 2014).

The free-text responses to question 7.a. also emphasize the importance of non-verbal clues (13), context (5), and plot (3) for deducing what the unsubtitled parts of the clips are about. Two respondents furthermore feel that non-translation adds to the humour of these scenes.

The last question in the block on (non-)subtitling (Q 14) seeks to establish what difference it would make to viewers if all ST scenes involving an L3 were translated (the translation mode and ST/TT were deliberately left unspecified in Q 14). More than half of the respondents (43/81) point out that the series would be less realistic and/or the characters less authentic if all multilingual scenes were translated. This result suggests that certain viewer groups disapprove of the loss of plausibility/realism caused by linguistic homogenization. This issue will receive more attention in the discussion. Nearly a quarter (20/81) claim they would enjoy the series more, as they would be able to understand everything, and 11/81 state that for them it would not make any difference.

Three free-text responses to question 14 support the “I would enjoy the series more, if everything was translated” closed-answer option but add limitations, such as: it depends on the translation mode and/or the context/scene; it would be less distracting; not at the expense of suspense (“ruining scenes by overtranslating elements that give away the plot” (R 51)); or that translating everything would blow the empathy-creating effect of non-subtitling. The majority of open answers (4) evoke (non-)translation as an artistic/stylistic device: to engage the audience with the plot (1), to change the “tone” of the story (1), and/or to create the realistic experience “of not being able to understand most of the languages of the world” (1, R 12).

4.3. Motivations for non-subtitling

As previously stated, audience response to and perception of motivations for non-subtitling is the core subject of this study. Possible or assumed reasons given by the participants regarding why the creators of BB chose not to provide subtitles for certain parts of the script involving L3s are dealt with in questions 8, 9, and 10.

The free-text responses to question 8 were independently coded in NVivo by both authors. They achieved between 97.1% and 100% agreement.

In relation to the four clips (306, 308, 311, and 313) question 8 is based on, 107[20] responses mention that the creators of the series had chosen not to provide a translation because it was not necessary/important (32), since the context (31) or non-verbal clues (17) provided sufficient evidence for the understanding of the scenes, or because “exact” translations were not important for understanding the plot (27). Eight participants list quantitative reasons (e.g. L3 utterances were too short, or the use of subtitling would be more expensive).

The vast majority of participants, however, think that in the clips question 8 is based on non-subtitling is a narrative or stylistic device (266) deployed by the creators of the series to, for example, create empathy with the characters who do not understand the L3s (57) (e.g. “it’s a device deliberately used by the director to put the viewer in the position of the characters” (R 3); “to make the viewer empathize with the non-multilingual characters” (R 56)), for humorous purposes (35), to engage the audience with the plot (24), to make the scene real/authentic (48) or more interesting (12), to create suspense (39), mystery/intrigue (17), exoticism (10) or a certain atmosphere (8) (e.g. “to establish and maintain the otherness of the cartel, and sound out the unknown world that White has unwittingly stumbled into” (R 72)), or for character description (1).

It is important to recall that, at this point in the survey (Q 8), participants have not been confronted with the notion that non-subtitling could be a deliberate stylistic device; it is only in question 9 that respondents are presented with motivations for non-translation sourced from the literature. These are presented below:

Table 9

Motivations for non-subtitling according to the survey respondents (Q 9, no. (%), row total 81; see questionnaire Q 9 for definitions of the motivations)

Table 9 illustrates that, according to our respondents, the most likely reasons why subtitles are not provided for the scenes involving L3s in clips 308, 311, and 313 are: (d.) the meaning of L3 parts can be deduced from non-verbal channels, (f.) the creation of suspense, and (g.) empathy. Less likely reasons for non-subtitling are (b.) the relevance of the L3 utterances to the plot, (c.) the duration of the L3 turns, and other (a.) quantitative reasons. The least likely reason for non-subtitling according to our participants is (e.) linguistic similarity between L3 and L1.

These results are similar to the findings that emerged from the thematic coding of question 8. Participants mostly rule out linguistic similarity as a reason for non-subtitling. Relevance of the L3 dialogue to the plot is considered important, as are non-verbal clues that render a translation of the L3 sections unnecessary. The duration of the scene emerges as one of the most important quantitative reasons for non-subtitling from question 9. Among the stylistic motivations for non-subtitling, suspense ranks high in both questions. Finally, empathy, i.e. non-subtitling as a deliberate device to put the viewer in the position of characters who do not understand the L3, is considered to be the most likely motivation for non-subtitling in both questions 8 and 9. The comparison of viewers’ responses to open-ended question 8 and closed question 9 shows a) that both methods of data collection yield similar results, b) that the participants can identify reasons for non-subtitling with (Q 9) and without (Q 8) prompts, and c) that they agree to a large extent on why certain turns in L3 are left untranslated. For the clips questions 8 and 9 are based on, the most important narrative reasons for non-subtitling are clearly considered to be the creation of empathy and suspense.

Open-ended question 10 is identical to question 8, but based on different clips (307_One Minute_Scene 1 and 313_Full Measure_Scene 1_1). As pointed out in Section 3.3, the rationale behind the use of different clips is to identify how much participants’ responses depend on the context. Question 10 was again independently coded by both authors, who achieved between 95.36% and 100% agreement. The free-text responses to question 10 are quite different from those to question 8. Answers are less detailed and fall into fewer thematic categories, which supports interpretation c) above, i.e. that participants largely agree on why no subtitles are provided for certain turns in L3, and illustrates that the motivations the respondents attribute to non-subtitling are context-sensitive. 181 comments state that a translation for the clips used in question 10 is not necessary because the scenes are not relevant to the plot (71), because enough contextual information (50) and non-verbal clues (13) are available to interpret the L3 turns, or because they are simply not important (47), although it is not specified why. 78 responses attributed different stylistic motivations/effects to the non-subtitling of L3 passages in the clips used for question 10: most participants think the main aim of non-subtitling in these clips is to create suspense (28) or authenticity/realism (17). Nine responses suggest that maintaining the multilingualism of the ST creates a certain atmosphere or aids the character description (5). Audience engagement, the creation of mystery/intrigue, and empathy/connection with the characters are each named as possible motivations for non-subtitling in four responses, and exoticism in three. Eleven comments reflect on the linguistic similarity between L3 and L2.

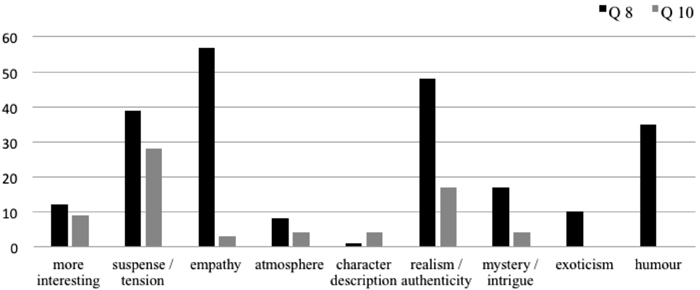

A comparison of non-stylistic reasons for non-subtitling in questions 8 and 10 (Figure 3) shows that more survey participants feel that translation is not important or necessary in the clips question 10 is based on, because the L3 turns are not relevant to the plot.

Figure 3

Comparison of Q 8 and Q 10: non-stylistic reasons

Question 10 also produced fewer types (8 vs. 10) and tokens (78 vs. 266) of stylistic devices than question 8 (see Figure 4). All motivations for non-subtitling suggested in the literature (Q 9) also feature in the answers to question 10. The most noteworthy results in Figure 4 are that – with one exception (character description) – all stylistic motivations for non-subtitling are mentioned less frequently in question 10 in comparison with question 8. We attribute this to the different clips these questions are based on, e.g. the fact that those used for question 10 – unlike the clips referred to in question 8 – do not show the perspective of a non-L3 character. The creation of suspense/tension, realism/authenticity, mystery/intrigue, and especially empathy are considered to be less likely reasons for non-subtitling in the clips question 10 is based on than in those question 8 refers to; only character description scored higher in question 10 than it did in question 8.

Figure 4

Comparison of Q 8 and Q 10: stylistic device

The results of questions 8-10 indicate that viewers are able to identify deliberate non-subtitling as a narrative device with clearly specified functions (Q 8), that the motivations for non-translation discussed in the literature to date are also independently recognized by viewers (Qs 9 and 10), and that participant responses are highly context-sensitive, i.e. they attribute motivations for non-subtitling depending on individual scenes/clips (Qs 8 and 10).

The results presented in section 4 are discussed and contextualized in the next section.

5. Discussion and implications

Previous studies have suggested that some sections of the viewing public are critical of the linguistic homogenization of multilingual AV products (Heiss 2004 and 2014; Bleichenbacher 2008) and that the “widespread practice of trying to meet the presumed expectations of the target audience” (Heiss 2004: 213) is a misguided consideration on the part of the AVT industry. Other studies have presented some evidence (from messages on the Internet Movie Database [IMDb]) that replacement strategies are “far from being welcomed or even accepted at least by some members of the audience” (Bleichenbacher 2012: 167). Furthermore, Heiss (2014: 14) and Bleichenbacher (2012: 167) suggest that it is the unrealistic reflection of multilingual sociolinguistic realities that viewers are averse to and claim that it is particularly viewers with above-average education and interest (Heiss 2004: 215) or specific linguistic biographies (Bleichenbacher 2012: 167) who disapprove of the loss of plausibility/realism caused by linguistic homogenization.

The results of this first reception study among hearing viewers provide empirical evidence that the use of multiple languages and the marking of this language diversity through non-translation is not only accepted but even appreciated by large parts of the target audience, both in subtitling and dubbing countries. A majority of respondents (60%) consider multilingualism an important element of BB (Q 2), and three out of four participants (79%) favour maintaining the multilingualism of the original in the TT version (Q 3). These findings are in line with the popularity, high rating, and commercial and artistic success of some recent multilingual productions, such as BB. They also support Bleichenbacher’s conclusion that viewers generally present a favourable reaction to “a rich and balanced depiction of multilingual phenomena” (2012: 155) on online message boards.

Even those participants who preferred a complete translation of L3 utterances unanimously voted for L3 parts to be subtitled instead of dubbed. On the one hand, this is in line with the survey results on dubbing vs. subtitling, which show a clear preference for subtitling among survey respondents (84% vs. 16%). On the other hand, this is remarkable if we bear in mind that approximately two-thirds of the respondents come from countries where the majority of (mainstream) foreign-language AV productions are dubbed, and subtitling is largely restricted to documentaries and art-house films. This might be partly due to the fact that the target audience of BB (and other “prestige TV” series) is different from that of “average” TV shows in that BB targets educated professionals (Beck 2013; see also notes 6 and 11). The results of this survey therefore support the conclusion that “knowledge of foreign languages and university studies encourage citizens to choose subtitling rather than dubbing” (Media Consulting Group 2011, cited in Pym, Malmkjaer, et al. 2013: 20; Heiss 2004).

From the survey, it has become evident that there is a broad acceptance of not just preserving multilingualism (e.g. through intralingual transcription or interlingual subtitling) but even highlighting it through non-translation/non-subtitling. The results, however, also show that non-translation is not supported at all costs. Almost two-thirds of the respondents prefer subtitles when a scene is important to the plot, or if either context or visual information do not clarify what the unsubtitled passages are about (Qs 6 and 14). Both questions indicate that when it comes to translation, the relevance of an L3 scene or utterance to the plot is of great importance to many viewers.

The vast majority of respondents claim they are able to follow the untranslated scenes in the clips related to Q 7, although more than half of them do not speak the unsubtitled languages. This shows that language is not always a barrier to understanding and that instances of non-translation are not necessarily “incomprehensible turns” (Bleichenbacher 2008: 182).[21] The context of a scene as well as visual clues are of particular importance for the viewers’ understanding. Both factors are rated higher than linguistic knowledge.

There are at least two possible interpretations of these results: a) the linguistic knowledge of the respondents in question is not enough to understand the untranslated utterances, or b) viewers rely more on the context and/or visual clues of an unsubtitled scene because their linguistic knowledge of the L3 is deactivated when watching an L1 film (Grosjean 1998). The first interpretation seems unlikely, because 45.7% of the survey respondents list Spanish (the main L3 in BB) as one of the languages they speak and only three qualify this with “little.” The psycholinguistic explanation b) therefore seems more likely. Literature on bilingual processing and, specifically, Grosjean’s notion of language mode suggest various levels of activation of the bilingual’s two languages (A and B) and language processing mechanisms, at a given point in time (Figure 5).

Figure 5

Bilinguals’ language modes (Grosjean 1998: 136)

According to Grosjean (1998), when viewers are in monolingual mode, Language A/L1 or L2 is highly active, while language B/L3 is only very slightly active. Language B/L3 can be activated, but if untranslated L3 scenes are very short, the bilinguals’ L3 processing mechanisms may come online too late for the viewer to process these sequences, i.e. they “miss” these turns. This may lead to viewers in monolingual (L1 or L2) mode being unable to linguistically process short L3 sequences, even if they are fluent in L3. As a result, they rely on context and non-verbal clues instead. Here, the interaction between visual and acoustic codes in AV texts becomes particularly evident. These results also highlight the primary role multimodality plays in translation (O’Sullivan 2013a: 123; 2013b: 2), especially in the translation of multilingual AV texts.

In terms of motivations for non-subtitling (Qs 8 to 10), our survey has shown that dramaturgical/stylistic reasons are considered more likely to be possible motivations for non-subtitling than factors that are not immediately related to the narrative side of an AV text. This empirical reception study thus shows that most respondents understand that the directors/authors of the original script pursue a particular purpose by not providing subtitles and are able to attribute specific motivations to their absence. These motivations furthermore coincide with what authors/directors report using deliberate non-translation for (de Higes Andino 2014; Sanz Ortega 2015), as well as academic analyses of the narrative functions of non-translation (Heiss 2004; 2014; Wahl 2005; Bleichenbacher 2008; 2012; Mingant 2010; de Higes Andino, Prats Rodríguez, et al. 2013; de Higes Andino 2014; Sanz Ortega 2015).

This finding is encouraging for filmmakers who have used deliberate non-translation to create specific effects, such as Jean-Luc Godard in Film Socialisme (2010)[22] and Quentin Tarantino in Inglourious Basterds (2009).[23] With respect to BB, Erik Paulsen, dialogue director of the German dubbed version of BB, confirms that the original scripts contain instructions on whether or not L3 utterances are to be subtitled (both in the English and non-English versions; see also notes 5 and 6). Paulsen (see note 6) further affirms that the authors’ decision not to provide subtitles clearly served a specific purpose; in many cases, evoking the audience’s empathy with the non-L3 characters by creating a subjective camera effect (2014b). The different free-text responses to questions 8 and 10, which are identical but based on different clips, show that viewers are sensitive to these differences. Empathy features less prominently in the open-ended answers to question 10, which we attribute to the fact that the clips used for question 10 – unlike those referred to in question 8 – do not show the perspective of a non-L3 character.

These nuanced responses furthermore support the view that the other-language status of a ST L3 is retained in the TT when ST L3 ≠ L2 (Corrius and Zabalbeascoa 2011: 22, Operation 6[24]). In cases when the ST L3 coincides with the language of the TT, it seems that a meaningful distinction has to be made between subtitling and other forms of AVT (e.g. dubbing). In dubbed AV texts, the ST L3 will be difficult to differentiate from the main language of the TT, because it blends into the TT (ST L3 = TT L2). In subtitled AV texts, however, this standardizing effect is weaker, because the viewer of the subtitled AV text can be reasonably expected to appreciate language variation (L1 vs. L3) through the audio track. Deliberate non-subtitling seems to have a foreignizing[25] (Venuti 1995) effect because the contrast between the “full” audio track and the “blank” subtitling space draws particular attention to the absence of a translation and thus highlights the multilingual sociolinguistic reality of the AV product, as indicated in Figure 1. This observation needs to be accounted for in a theoretical framework of translation operations for subtitled AV texts.[26]

6. Summary and conclusion

Multilingualism in films and TV series, as well as (non-)translation in AV texts, is a subject of great topicality. Not only is this evident from films like Inglourious Basterds – a film that not only includes four languages, but is, in fact, “all about language and translation in the cinema”[27] – and the recent trend of multilingual films in Hollywood (Mingant 2010: 712), it is also apparent from the popularity, high rating, and commercial and artistic success of some recent multilingual TV series, such as BB. These productions demonstrate that multilingualism and non-subtitling are no longer features exclusively belonging to the domain of art-house productions. Instead, they have become more common cinematographic practices that can also reach and be successful among a mainstream audience, not only in subtitling countries, but also in countries with a dubbing tradition.

This first empirical study of hearing viewers’ opinion on, and perception of, the (non-) translation of multilingualism has shown that the multilingualism of the TV series used as an example, Breaking Bad, is (very) important to its target audience. Our participants express a clear preference for the multilingualism of the original to be maintained and for subtitling as a translation mode. They furthermore express a generally positive attitude towards non-translation and feel that translating all turns in L3 would make the series less realistic. They use contextual information, non-verbal clues (such as paralanguage and kinesics), and linguistic knowledge (in this order) to deduce the meaning of untranslated utterances. Without being confronted with the notion that non-subtitling could be a stylistic device with specific functions, viewers are clearly able to identify deliberate non-subtitling as such.

The results of this empirical reception study thus compare well with Bleichenbacher’s analysis of viewers’ reactions to multilingualism in mainstream movie dialogues on IMDb. In particular, they corroborate Bleichenbacher’s (2012: 171) findings that viewers “draw on their everyday or specialist knowledge of linguistic facts, relate what they see to […] their own experiences, negotiate differences between fiction and reality” and identify possible narrative functions of different kinds of dialogue. Most importantly, our findings support his conclusion that “there is a general acceptance of, and even a frequent enthusiasm about instances of multilingual diversity” (Bleichenbacher 2012: 172) in AV products.

Together, these findings contribute to the academic discussion of the translation of multilingualism in AV texts by showing that untranslated sequences are not entirely “uninterpretable.” Linguistic knowledge of the L3(s), however, seems to play a tertiary role in deducing what untranslated passages are about. This was attributed to viewers’ L3s being only weakly activated while watching an L1/L2 AV product and the activation of L3 linguistic processing mechanisms taking too long for short untranslated sequences. This study also suggests that a meaningful distinction has to be made between different forms of AVT with respect to the effect of non-translation. In dubbed AV productions an L3 can become invisible/inaudible if it coincides with the main language of the TT; in subtitled AV texts, on the other hand, the language variation in the ST remains appreciable through the audio as part of the AV communication experience. Non-subtitled L3 sequences may thus draw particular attention to the multilingual character of the AV product.

The results of this study may therefore not only be of interest to the translation research community, but also to various agents in the international film and AVT industry. The fact that both multilingualism and non-subtitling in one of the most popular and highest-rated TV series is appreciated by viewers both in subtitling and dubbing countries could be a particularly interesting insight for film distributors in different countries.

The limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size and its focus on one multilingual TV series. This and other reception studies (Antonini and Chiaro 2009; Pablos Ortega 2015) furthermore suggest that more detailed information on participants’ educational and linguistic background would be useful to gain a better understanding of the expectations of more precise audience targets.

Following on from this exploratory project, future surveys could, for example, use a more qualitative approach and pursue one of the aspects covered here in more depth. One option would be to include dubbing as a mode of AVT to complement the results that have been obtained in this study. Furthermore, future surveys could make use of a more extensive corpus with clips that represent a wider variety of scenes with different characteristics. More information on participants’ multilingual competences would also be useful to establish the influence of viewers’ linguistic background on their viewing preferences and experience.

A detailed comparison between filmmakers/producers’ motivations for non-translation to those identified by the target audience might be another interesting option for future research. We furthermore intend to experimentally test the psycholinguistic explanation proposed for the findings on the (limited) role L3 knowledge seems to play in the semantic decoding of untranslated sequences.

Even though the results of this study can, of course, not be generalized in every respect and with regard to any audience, they can still be interpreted as an encouragement for film distributors and TV stations not to be afraid of “making” viewers watch multilingual films or TV series – including and especially those who are used to dubbing. Or, in view of the findings on subtitling/dubbing and some comments made by survey respondents from dubbing countries, the results can be understood as an incentive to further increase the number of films or television programmes presented in the original version with subtitles in the TL.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang (1820/1960): Berliner Ausgabe. Poetische Werke [Berlin Edition. Poetic Works]. Vol. 3. Berlin: Aufbau Verlag.

-

[2]

We use “non-translation” as an umbrella term for any type of non-translation, and “non-subtitling” in the specific context of subtitled productions.

-

[3]

Season 3 (21 March-13 June 2010). In: Breaking Bad (20 January 2008 to 29 September 2013). United States of America. Created by Vince Gilligan. Produced by High Bridge Productions, Gran Via Productions, and Sony Pictures Television. Distributed by Sony Pictures Television. Released by AMC.

-

[4]

Szarkowska, Zbikowska, et al. (2013) conducted an online survey that investigated the subtitling of multilingual films for the deaf and hard of hearing.

-

[5]

Paulsen, Erik (15 August 2014): personal communication, email.

-

[6]

Paulsen, Erik (13 August 2014): personal communication, email.

-

[7]

Zabalbeascoa (personal communication) stresses that Corrius and Zabalbeascoa (2011) do not explicitly cover non-translation in subtitled AV products and that Operations 6 and 8 require a different treatment depending on the translation mode.

-

[8]

IMDb contributors (2008. ): Breaking Bad - Full Cast & Crew. Internet Movie Database (IMDb). Visited 28 August 2014, <http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0903747/fullcredits?ref_=tt_ov_st_sm>.

-

[9]

Wikipedia contributers (Last update: 17 July 2018): Breaking Bad. In: Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Visited July 19 2018, <https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Breaking_Bad&oldid=863538881>.

-

[10]

Segal, David (6 July 2011): The Dark Art of ‘Breaking Bad.’ The New York Times. Visited 28 August 2014, <https://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/10/magazine/the-dark-art-of-breaking-bad.html?page%20wanted=all&_r=0>.

-

[11]

Paulsen, Erik (22 August 2014): personal communication, email.

-

[12]

Episode numbers are composed of the number of the season (SE) and the number of the episode (E), e.g. SE03E01 = season 03, episode 01.

-

[13]

306_Sunset_Scene 1_EN no subs.wmv (Q 3); 311_Abiquiu_Scene 1_EN subs.wmv (Q 4);

308_I See You_Scene 2_EN subs.wmv, 313_Full Measure_Scene 1_2_EN subs.wmv (Q 7);

307_One Minute_Scene 1_EN subs.wmv, 313_Full Measure_Scene 1_1.wmv (Q 10). Available at <https://drive.google.com/folderview?id=0B7MIrO07F2khVS0xdkVwcEg4UlE&usp=sharing>.

Only the first author had full access to the videos. Survey respondents could view the clips, but could not edit or download them.

-

[14]

Downey, Kevin (2008): For AMC, a well-laid path of originals. Media Life Magazine. Visited 23 August 2014. <http://www.medialifemagazine.com/for-amc-a-well-laid-path-of-originals/>.

-

[15]

Beck, Richard (2013): Myths of the Golden Age. Prospect. Visited 23 August 2014, <http://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/arts-and-books/myths-of-the-golden-age-richard-beck-prestige-tv>.

-

[16]

ARTE (last update: 20 June 2018): ARTE at a glance. Consulted on 30 June 2018, <https://www.arte.tv/sites/en/corporate/who-we-are/?lang=en>.

-

[17]

Significance tests were performed on all correlation analyses; none of them reached significance at the 0.05 level.

-

[18]

Respondents who had not watched a full episode of BB were expected to select “N/A”; four of them didn’t, which resulted in 4.9% of uninformed answers in Table 4.

-

[19]

The survey does not consider the option of having part-subtitles in a dubbed version because the focus of the study is on subtitling.

-

[20]

The number of responses can be higher than the number of respondents because some open-ended answers contained several statements.

-

[21]

Although Bleichenbacher repeatedly refers to untranslated utterances as “incomprehensible turns,” he acknowledges that “if the context of the conversation […] is clear enough, even longer utterances do not necessarily prevent the viewer from understanding what’s going on” (2008: 179).

-

[22]

Film Socialisme (2010): Directed by Jean-Luc Godard. Vega Film. France.

-

[23]

Inglourious Basterds (2009): Directed by Quentin Tarantino. A Band Apart and Studio Babelsberg. United States of America.

-

[24]

For Corrius and Zabalbeascoa’s Operation 6 it would be interesting to learn if “repeat” for subtitled AV products includes only intralinguistic subtitles or also deliberate non-subtitling.

-

[25]

Foreignizing is described as “pressure [on the viewers] to register the linguistic and cultural difference of the foreign text, sending the reader abroad” (Venuti 1995: 20).

-

[26]

Corrius and Zabalbeascoa (personal communication) intend to follow up their 2011 paper with a publication on subtitling in which Operations 6 and 8 will receive differential treatment for dubbing and subtitling.

-

[27]

O’Sullivan, Carol (2010): Tarantino on language and translation. MA Translation Studies News. Visited 23 August 2014, <http://matsnews.blogspot.com/2010/02/tarantino-on-language-and-translation.html>.

Bibliography

- Antonini, Rachele, Bucaria, Chiara and Senzani, Alessandra (2003): It’s a priest thing, you wouldn’t understand: ‘Father Ted’ goes to Italy. Antares Umorul-O Nouă Stiinta. VI:26-30.

- Antonini, Rachele and Chiaro, Delia (2009): The Perception of Dubbing by Italian Audiences. In: Jorge Díaz Cintas, ed. Audiovisual Translation: Language Transfer on Screen. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 97-114.

- Baldo, Michela (2009): Dubbing multilingual films: ‘La terra del ritorno’ and the Italian-Canadian immigrant experience. Intralinea. 8 p. Visited 28 February 2016, http://www.intralinea.org/specials/article/Dubbing_multilingual_films.

- Bartoll, Eduard (2006): Subtitling multilingual films. In: Mary Carroll, Heidrun Gerzymisch-Arbogast and Sandra Nauert, eds. Audiovisual Translation Scenarios. (MuTra: Audiovisual Translation Scenarios, Copenhagen, 1-5 May 2006). Visited 9 February 2016, http://www.euroconferences.info/proceedings/2006_Proceedings/2006_proceedings.html.

- Bleichenbacher, Lukas (2008): Multilingualism in the Movies: Hollywood Characters and Their Language Choices. Tübingen: Francke.

- Bleichenbacher, Lukas (2012): Linguicism in Hollywood movies? Representations of, and audience reactions to multilingualism in mainstream movie dialogues. Multilingua - Journal of Cross-Cultural and Interlanguage Communication. 31(2):155-176.

- Boyatzis, Richard E. (1998): Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Thousand Oaks/London/New Delhi: Sage Publications.

- Bréan, Samuel (2011): godard english cannes: The Reception of Film Socialisme’s “Navajo English” Subtitles. Senses of Cinema. 60. Visited 1 August 2014, http://sensesofcinema.com/2011/feature-articles/godardenglishcannes-the-reception-of-film-socialismes-navajo-english-subtitles/.

- Chaume, Frederic (2012): Audiovisual Translation: Dubbing. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing.

- Chiaro, Delia (2008): Issues of quality in screen translation: Problems and solutions. In: Delia Chiaro, Christine Heiss and Chiara Bucaria, eds. Between Text and Image: Updating research in screen translation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 241-256.

- Clarke, Victoria and Braun, Virginia (2013): Teaching thematic analysis: Overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. The Psychologist. 26(2):120-123.