Résumés

Abstract

Following Dollerup’s (2000) classification of indirect and relay translation (here “T2”), this study locates both practices as translation taboos disparaged or tolerated depending upon cultural variables, shows its codification in translation organizations, and traces part of its aura of substandard practice to the doctrine of untranslatability; compiles the main reasons the phenomena have occurred, including extralinguistic factors; outlines some subclasses in a typology of ‘second-hand’ or intermediate translations (factoring in abridgements, adaptations, modernizations, lost originals, pseudotranslations, self-translations, triangulations, and transcreations); proposes ‘translative’ and ‘terminal’ relay, and overt and covert possibilities within retranslation, interlinear translation, plagiarism by translation, and support translation; considers the special case of sacred texts; and weighs new and future directions for study. The key factors of oral intermediation (the role of informants and collaborative translation) and the ‘intuiting’ of source languages without a working knowledge of them are brought into the equation. The work attempts to contribute a descriptive study to an area of research that has attracted visceral rejections of anything but source-to-target direct translation without such studies making allowances for the socio-historical conditions of production surrounding intermediary translation.

Keywords:

- indirect translation,

- relay translation,

- intermediate translation,

- support translation,

- overt translation,

- covert translation

Résumé

Suivant la classification de Dollerup (2000) de la traduction relais et de la traduction indirecte (« T2 »), la présente étude situe ces deux pratiques comme des tabous de traduction dépréciés ou tolérés selon des variables culturelles diverses, expose leur codification au sein d’organismes de traduction, et lie en partie le fait qu’elles soient considérées comme de mauvaises pratiques à la doctrine de l’intraduisibilité. L’étude établit les causes principales de ces phénomènes, y compris des éléments extralinguistiques. Elle définit certaines sous-catégories d’une typologie des traductions dites « de seconde main » ou intermédiaires (par exemple, abrégements, adaptations, modernisations, traductions dont les originaux sont perdus, pseudo-traductions, auto-traductions, triangulations et transcréations). Elle envisage un relais « traductif » et « terminal » et des possibilités de retraduction directe et indirecte, la traduction interlinéaire, le plagiat par traduction et la traduction par assistance. Elle se penche sur le cas particulier des textes sacrés. Enfin, elle évalue de nouvelles orientations et des voies futures pour la recherche. Les éléments essentiels de l’intermédiation orale (le rôle des informateurs et de la traduction collaborative) et l’« intuition » des langues sources en dehors d’une connaissance fonctionnelle sont également pris en considération. L’article se veut une étude descriptive dans un domaine de recherche qui a entretenu un rejet viscéral de tout ce qui n’est pas traduction directe du texte source au texte cible sans que de telles études puissent faire la lumière sur les conditions socio-historiques de la production entourant la traduction intermédiaire.

Mots-clés :

- traduction indirecte,

- traduction relais,

- traduction intermédiaire,

- traduction assistée,

- traduction directe,

- traduction indirecte

Corps de l’article

On the one hand, the world is presented to us as a collection of similarities; on the other, as a growing heap of texts, each slightly different from the one that came before it: translations of translations of translations.

Paz 1992: 154; translated by del Corral

1. Introduction

When Willis Barnstone quipped that a translation is “frequently a historical process for creating originals,” he was writing about a text’s artful concealment of its own status as a translation, and the suppression of an earlier source, a pre-text, allowing gods in a sacred text, for example, to appear “self-created” (Barnstone 1993:141). But unsuspected insight emerges from his playful observation in cases of translations of translation, that is, indirect translations (second-hand translations, second-generation translations, intermediate translations, or intermediary translations), which can be defined as translations, partial translations or adaptations that serve as an acknowledged or unacknowledged new source text. In this paper I wish to revisit Cay Dollerup’s (2000) distinction between indirect translations[1] (intermediate translations not intended for consumption), relay translations (intermediate translations for a readership), and support translations (consulted same-text translations into other target systems). In the process I wish to nuance a few of the interrelations, subtypes, and exceptions to his model, focusing especially on modern interliterary relations. Some fuller implications of the Dollerup model will be drawn out, including the political dimensions of multiple writers and languages in confrontation. Inextricably bound with these considerations is the issue of a relay translation’s status. It should follow from recent translation theory that if a translation is a further iteration of a text and not held to be the text’s ‘double,’ then a translation of a translation should not provoke the disquiet it does. I intend this study to be not an apologetics nor yet an enumeration of the practice’s drawbacks, but a descriptive approach to the modalities and channels of T2 (as I will call all forms of relay and indirect translation). Ultimately, with José Lambert, I aim to lend further credence to the idea that “the reduction [of translation] to bilateral relationships is an oversimplification” (Lambert 2006: 91, note 4). Secondary and tertiary translations, moreover, can raise our awareness of translated literary works as palimpsestic narratives.

2. Taboos of T2

Translation is beset by theoretical taboos that nevertheless are widespread practice. The polymorphous modes of directionality are a case in point: working into one’s non-native language, for instance, is maligned in some codes of practice as substandard, yet it happens routinely, and for different reasons. Relay translations are a practice built into workflows in international organizations (which also practice relay interpreting), publishing practices (devotional and literary texts), historical texts, audiovisual translation, and the global news industry. Pederson, for example, describes the advent of ‘Genesis’ files in DVD production, which are essentially intralingual subtitle files, and for TV, master template files in which the first-generation translation is used to seed second-generation titles without one having to re-do segmenting and cueing (Pederson 2011: 16-17). Nobel Prizes in Literature are awarded based on readings of relay translations (consider how few translators work Chinese>Swedish).[2] And Bielsa and Bassnett, writing on global news, describe what editor-in-chief Eric Wishart termed the “news-gathering procedure”:

The first news [of an explosion in North Korea] came through to the Agence France-Presse from the Chinese News Agency in Chinese and also in English. […] There was nothing from the North Korean News Agency, but stories then came from South Korean agencies, in Korean and in English. Translators in local bureaus worked on putting the Chinese and Korean versions into English, after which the texts were sent to a central editing desk. A French writer in Hong Kong was translating the English into French… [O]nce the story is sent round the world, it is translated again into other languages for local use.

Bielsa and Bassnett 2009: 14

Yet the aversion to translations of translations in literature, even the denial of their possibility, runs through Translation Studies, most famously in Walter Benjamin’s writings:

The transfer can never be total, but what reaches this region is that element in a translation which goes beyond transmittal of subject matter. This nucleus is best defined as the element that does not lend itself to translation.[3]

Benjamin 1968: 75, translated by Harry Zohn, cited in Rendall 2000: 24

The idea as expressed by Benjamin is difficult and often debated:

[T]he point here is surely that whatever aspect of the “wesenhafte Kern” is echoed in a translation (“an ihr” clearly refers back to “die Übersetzung” in the preceding sentence) cannot be translated again. This presupposes, of course, that the “wesenhafte Kern” can be translated a first time. The reason it cannot be translated again – that is, the reason a translation of a translation gives no access to this essential nucleus of language – is as Rodolphe Gasché’s reading of the essay suggests, that this “wesenhafte Kern” of language consists of communicability or translatability itself, that which within language exceeds any given use, situation – or “language” (Gasché 1986). A translation of the kind Benjamin is defining makes perceptible the element of “pure language” simultaneously hidden and designated in the text to be translated – and which is precisely its translatability.

Rendall 2000: 24

The doctrine of untranslatability, then, eventually is invoked in such discussions (though, curiously, back-translation survives, and is even codified, as a translation diagnostic in some sectors).[4] Many scholars, consciously or unconsciously, scorn T2 practices as not belonging properly to translation, as in Susan Bernofsky’s description of the drop in foreign language study in the early 1800s, resulting in many Greek, Latin, English and Spanish works being “translated” (the ironic quotes are the critic’s) into German (L3) from French translation (Bernofsky 2005: 5). In short, very few dispassionate studies on T2 have been carried out. Depending on the critic or reviewer, T2 is figured either as a cryptozoological curiosity or as a shameful pathology (see, for example, the website Twice removed [Anonymous 2003]).[5] Toury writes of how the phenomenon has long been characterized as ‘illness’ rather than the more accurate ‘symptom’ or ‘syndrome,’ a “juncture where systemic relationships and historically determined norms intersect and correlate” (Toury 1995: 129-30). L2 translation, in the former view, becomes the ‘pure’ pole in the pure-to-impure spectrum, and contagion is introduced from the ‘invasive species,’ the L3. Tellingly, everyday L2 translation has long been subjected to a similar parasitological discourse that marginalizes it as corrupt, degenerate. Who is afraid of mere translation when there are translations of translations – or even tertiary translations: translations of translations of translations (e.g. the Georgian version from the Armenian version of the Septuagint) (Wegner 1999: 243)?

In practice, no stated taboo (and this word is used for both its visceral and normative dimensions) inheres to the phenomenon; rather, Benjamin aside, the acceptability of T2 is bound to no absolutes. According to Theo Hermans: “[T]he rules permitting or forbidding translation from an intermediate language rather than from the original source language vary over time as well as cross-culturally and in relation to particular genres and source language” (Hermans 1999: 75). In this light we may position reception of these works as a bias or intolerance, despite their near-ubiquity. Marín Lacarta (2008) argues that T2’s very covertness suggests an intolerance. Yet the question of whether tolerance varies between specialized and lay readerships, lesson common languages and dominant languages, and professional codes and actual practice, remains to be elucidated, as does the matter itself of wherein the scandal lies for those that have objected to it. When T2 is explicitly normed, constraints on the practice stem from the assumptions that L1 is the default starting place for the act of translation, and that authors’ work cannot be used instrumentally, that is, cannot mediate between other texts without due credit. Two clauses from the UNESCO Recommendation on the Legal Protection of Translators and Translations and the Practical Means to Improve the Status of Translators read as follows:

V. TRAINING AND WORKING CONDITIONS OF TRANSLATORS

[…]

14. With a view to improving the quality of translations, the following principles and practical measures should be expressly recognized in professional statutes mentioned under sub-paragraph 7 (a) and in any other written agreements between the translators and the users:

[…]

(c) as a general rule, a translation should be made from the original work, recourse being had to retranslation only where absolutely necessary;

(d) a translator should, as far as possible, translate into his own mother tongue or into a language of which he or she has a mastery equal to that of his or her mother tongue.[6]

UNESCO 22 November 1976

Curiously, clause V. 14. (d) provides a loophole the authors of the document did not foresee: the translator should work into languages he or she masters, but no source language mastery is prescribed. This leaves the door open to collaborative translation from languages of which one has no knowledge (unless one reads V. 14. (c) to preclude the use of cribs). Let us also compare with the literary translator’s deontological code proposed by the Spanish association of writers (Sección Autónoma de Libros de la Asociación Colegial de Escritores de España [ACE-Traductores]) referring to the European Council of Literary Translators’ Associations (ECLTA):

When a translation cannot be made from the original text and the translator uses a ‘bridge-translation,’ he or she should secure the permission of the author and credit the translator whose work is consulted.[7]

ACE-Traductores n. d.; translated by the author

Two comments arise here. First, linguistic knowledge is not the only factor involved in T2 practices, as we will see. The high prestige of the pivot language often underlies the decision to use it as a new source. Toury (2002: xx-xxv, cited in Pérez Gonzáles 2003: 59) relates how in the Hebrew Enlightenment (1750-1850), German texts were translated into Hebrew even though L1 translations could have been carried out. Second, the well-exercised bridge meme above, ubiquitous in translation studies and interpreting studies alike, points metaphorically toward a mediating text that is dislocated, suspended, existing only to span two loci. Thus the mediating text – the indirect translation – maps onto the territory of no-man’s-land, exile, rootlessness, u-topia (no place), and a dubious nether geography, as ‘indirect’ contains the semantic field of deceit, of artful deviation from straightforwardness. The title page convention of “Translated directly from the [source language]” thus has the ring of restorative justice. Yet reception of T2 has shown that direct versions have co-existed with indirect, the indirect even appearing after the direct (e.g., the highly circulated Mardrus/Mathers Arabic>French>English version of The Book of the Thousand and One Nights) (See the blog entry entitled Cinderella: Conclusions [Translatology 30 December 2010][8]; see also Cheung 2003).

Differences in the acceptability or normativity of T2 may derive from a fundamental divide articulated in Bakhtin’s monologic and dialogic perspectives. For Bakhtin, according to his chapter on Discourse in the Novel (Bakhtin 1981), the monologic describes a conception of language as transparent, its meanings stable, shared, and intransitive, and the voice in its literary manifestations authoritative; he saw the dialogic, which he privileged, as a model of interactional, interdependent, contextual, and open relations between texts and people – a meaning-transforming, rather than meaning-preserving, paradigm. He writes: “Forming itself in an atmosphere of the already spoken, the word is at the same time determined by that which has not yet been said but which is needed and in fact anticipated by the answering word” (Bakhtin 1981: 280). If we carry this logic to the level of texts within systems, the same dialogic fluidity, this notion of language “overpopulated… with the intentions of others,” would characterize T2 (Bakhtin 1981: 294). Literature’s representational ethics (Chesterman 2001), in this light, recedes in favor of a communicating vessels conception of literature. Perhaps at bottom, T2 offers a window into the utopianism of the whole translation enterprise: the belief, or the pretense, that something stable lies within language and within texts. We might challenge ourselves to ask, moreover: Which is more egregious: L1>L2>L3 translation by expert writers and translators, or an incompetent L1>L2 translation?

3. Why indirect translation occurs

As completely as possible, let’s try to draw the contours of why T2 occurs or has occurred:

Lack of knowledge or lack of translators working in the pair (due to geography, politics, language learning policy, lexicographical resources, etc.);

Lack of access to a tangible original (Ringmar 2006: 6);

Relative distance between languages (St. André 2003b: 62: Chinese into “European” translation is qualitatively different from “intra-European” translation). This logic would seem to follow the syllogism: L1 and L3 are too distant; L1 and L2 have an affinity, and L2 and L3 have an affinity, therefore L1 can reach L3 through L2;

Relative prestige of the languages involved (generally following the paradigm of weak>strong polysystem through cribs or compensatory translation, stronger>weaker polystem) (Toury [1980, 1995] in Shuttleworth and Cowie 1997: 76), or in other terms, from peripheral or semi-peripheral through central languages (Heilbron 2000);

Relative prestige of the texts involved;

Relative prestige of the L2 translation (trusted translators versus the risk of unknown translators; Domínguez Pérez 2008: 180); thus L2>L3 translation may arise due to the familiarity or canonicity of the L2 translation (e.g., Schiller poems appearing in a Russian novel; Zhukovsky’s Russian L2 used for the Ukranian L3 rather than L1>L3 due to the familiarity of the Russian version for Soviet readers (Friedberg 1997: 172); or Adrián Recinos’ classic translation of the Popol Vuh into Spanish (1947), which then gave rise to translations into Italian, English, and Japanese (Lifshey 2010: 47);

The mediating language, L2, is perceived as more apt for onward translation. The concept is akin to that of the “universal donor” in blood transfusions;

Copyright and authorial control, e.g., Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris is no longer in the control of the author’s estate (Anonymous 2003; see note 5 below). Bellos (2011b) writes that the Albanian source texts of Ismail Kadare’s work has no international copyright, so a new source text ensures the work’s survival and a measure of authorial control;

Intermediate texts can provide an edit of the L1 that save L3 publishers the effort of re-editing (Marín Lacarta 2008);

Intermediate texts can serve a censorial purpose for political or religious ends (Ringmar 2006: 7; Gambier 2003: 59);

Dividing lines between translation and original writing in the past were blurred, bracketing the matters of textual status and acceptability (Toury 1995: 132-133); such an environment favors T2;

Intermediate texts using an L2trot uncouple translation from source language mastery;

Cost (Marín Lacarta 2008);

Author preference (Marín Lacarta 2008).

4. Variations of T2

Some variations of relay and indirect translation that can be traced in literary history include:

Translation to a vehicular language and new authorship; e.g., Odysseas Elytis’ Sappho into modern Greek, then Greek> Italian with Elytis as principle author (Loulakaki-Moore 2010: 289);

Self-translation to a vehicular language, followed by relay; e.g., Bernardo Atxaga’s Obabakoak, Basque>Spanish, then to other European languages: a ‘pivot source’ (L1>L2 that seeds new translations);

Translation into L3 based on triangulations of L21 and L22; e.g., Anatoly Lunacharsky’s comparison of two German versions translated from the Hungarian (Radó 1975: 57-59);

Indeterminate L1>L21 and L22>L3>modernized L4; e.g., Geoffrey Gaimar’s 12th-century rendition, Estoire des Engleis [French] and Le Lai d’Havelok [Anglo-Norman] into Havelock the Dane [Middle English] (Ellis 2008: 300-301), then onward to different modernized versions; a back-translation from Middle English to the Anglo-Norman may have produced Layamon’s Brut (Ellis 2008: 301);

Translation into L4 based on triangulations of L2 and L3 translations; e.g., Witold Gombrowicz’ Ferdydurke was first translated with the author and a collaboration team into Spanish (1947), then French and German (1960s); then from these two (or perhaps three), into English;[9]

Intergeneric indirect translation; e.g. L1>L21 prose>L22 poetry>L3: Edgar Allan Poe’s poem Israfel was translated by Mallarmé into prose, then by Artaud into poetry, and finally by Herberto Helder into Portuguese (Buescu and Ferreira Duarte 2007: 179); Aesop’s Greek (6th century) was translated into Latin by Phaedrus (1st century), then Greek verse by Babrius (2nd century), then Latin verse by Avianus (4th century), then prose paraphrases (5th century forward) (Miner 1972: 10-11);

Transcreation into L4 based on an L3 triangulation of an L1 and an L2 semi-pseudotranslation; Pacheco Pinto (2009/2010: 5) describes the first poetic translation of Chinese poetry into a European language: Le Livre de Jade by Judith Gautier was composed from Chinese classical sources, then rendered into European languages, including Antonio Fiejo’s Portuguese Cancionero Chinês, followed by Songs of Li-Tai-Pé – An Interpretation from the Portuguese by Jordan Herbert Stabler in 1922. The same critic calls the L1 source “virtual,” and the L2 source “real” – though according to Yu (2007: 220), only two-thirds of the French is attributable to Chinese authors – and the L3 Portuguese, “a cultural translation… an intercultural contact zone”;

L1>L21 and L3 (both partial texts)>L22>L2abridgement (from L22)>L4s (French and other European)>L23 (from L1)>L42 (from L23)>L43 (from L1)>L24 (from the L43) (Cheung 2003: 29-35; St. André 2003a: 43) (for the full publishing chronology see St. André 2003b: 61-63); from the 18th century to the early twentieth century, thus is the (simplified) history of the first Chinese novel to be translated into the West, Haoqiu zhuan; L1=Chinese, L2=English, L3=Portuguese, L4=French;

L1>L2 translation>L3 adaptation; e.g., Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid was adapted into Breton from its French translation from Danish (Quentel 2006: 10); this model suggests that L1>L2 adaptation>L3 adaptation>etc. likely occurs as well;[10]

L11 and L12>L2 (e.g., Chaucer’s compilation of “The Clerk’s Tale” from Petrarch’s Latin and an anonymous French version) (Lie 2000: 708);

Lost original L1>L2>L3>etc.; examples abound in sacred texts (e.g., the Vulgate) and philosophy (Averroes’ Long Commentary on the De Animaof Aristotle).[11] One reason secondary translations are valued in textual criticism is that they can help determine their text of origin; Old Latin texts, for example offer insight into the Septuagint since they were translated from “some form of it” (Wegner 1999: 243).

T2 shifts, it should be noted, may be not only linguistic, but structural, poetological or ideological (Domínguez Pérez 2008: 177).

As noted above, Dollerup (2000) proposed that the term indirect translation be used for intermediary texts with no audience, that is, texts not intended for consumption. In literature we can exemplify this category further with intralingual translation; team translation (informant + target text author using “trots,” “cribs,” or “ponies”); and interlingual plagiarism[12] (plagiarism by translation), which are documented in modern times at least as far back as Sir Richard Burton’s ransacking of John Payne’s The Arabian Nights for his own version, alleged by many scholars, most notably Gerhardt (1963). And other writers have been accused of appropriating via translation, including Louis Carroll, who was charged with lifting Jabberwocky from the German (Ackerman 2008: 78). William Butler Yeats’ celebrated When you are old and grey and full of sleep perches so ambiguously between translation and unacknowledged appropriation, the poet’s own editors have been uncertain about calling it an adaptation, a translation, or an original poem (Shvabrin 2007: 219). Vladimir Nabokov translated Ronsard from this pseudo-original, supported, perhaps, with Sergei Krechetov’s version (Shvabrin 2007: 219).

An outlier case even in a field of exceptional cases are the experiments in “cross-cultural intertextuality” (Buescu and Ferreira Duarte 2007: 174) conducted by Herberto Helder. The Portuguese poet-translator has produced volumes of indirect translations from every conceivable literary source, mixed with versions, “poems changed into Portuguese,” and even a Portuguese poem presented as a translation, verbatim in Portuguese, all in juxtaposition with his own works. His aesthetics consists of pure bricolage:

I don’t know languages. This is my advantage. It allows me to render poetry from Ancient Egypt into Portuguese not knowing the language. I take the Song of Songs in English or French as if it were an English or French poem, and boldly dare to turn it not only into a Portuguese poem but also into a poem by me. An indirect version, someone says. Personal recreation, someone says; idle dilettantism, someone says. I say nothing. If I did say anything, I would say pleasure. [13]

Helder 1968

Dollerup’s (2000) support translations (i.e., other target texts used as parallel texts) and legacy translations (re-use of phrasing, for example in TMs) have subtypes and variations worthy of discussion: retranslations; modernizations (intralingual and interlingual), also called intertemporal translations (Robinson 1998: 114-116); and back translations. We should be careful not to oversimplify intralingual modernizations; following Maronitis (2008: 368-9), interpretations diverge on the matter of whether one is dealing with a single language in its historical progression or with drastic shifts that complicate genealogy, as in the case of ancient and modern Greek. As for back translation, two sub-subtypes would include 1) editions based on their own translations (translations that influence their own source texts in subsequent editions; e.g., José Ignacio Diez Fernandez based his L1 edition of Gracián’s Oráculo on Christopher Maurer’s 1992 translation into English [Pajares n. d.]); and 2) source novel reconstructions from translations (e.g., the lost Chinese source text to Lao She’s [also Lau Shaw] The Drum Singers [1953] was rewritten from its English translation [Almberg 1995: 925-926]). Back translation has occurred in literature in such cases as Macpherson’s Ossian poems, which were quoted in Werther and later back-translated into English without them being matched to the original pseudotranslations (Gaskill 2002: 270). Or consider the limit case, the most scandalous reconstruction of all: James Macpherson died in 1796 while attempting to retrofit a Poems of Ossian, in the Original Gaelic, a back-translating act of literary fraud to legitimize the imposture he had perpetrated in English. His friends finally finished it in 1807, and included a literal Latin translation; notes Ruthvin (2001: 12-13), “[f]ar from solving the problem of origins, it merely complicated the textuality of the text by rendering it polyglot.”

5. Transitive and terminal translations, overt and covert

Relay translation to a language from which more translations occur constitutes a kind of repositioning of the source from the periphery into relative centrality. In other words, in Atxaga’s case (see the second classification in Section 4 above), translation from Basque to Spanish, from which multiple ‘onward’ translations were then carried out into other major tongues. These operations constitute a strategic re-centering of a text written in a marginal language to a position of visibility, not only as a translation, but authorized by the relatively auratic act of self-translation into a new source. Ringmar argues that Axtaga’s involvement amounts to an “authorisation of the MT [mediating, or vehicular, text]” (Ringmar 2006: 11). Such new sources we might call a pivot source: texts written for consumption in a given language, but also used to seed multiple new translations. Such transitive texts, transitive translations, may be classed as different cases from those that are terminal translations, for variance can be traced in the systemic functions that transitive and terminal translations perform. Almberg (1995: 926) reminds us of the unusual case of The Rubaiyat, whose status so far eclipsed that of its Persian source that it in essence became a new source, opening new channels of transmission. Further research in this line of inquiry could discover whether these pivot sources are written in such as way as to facilitate translation; in other words, a particular kind of writing for translation: translating for translation.

Naturally, then, the question of what we might call covert relay – camouflaged (Martín Lacarta’s term) T2 – and overt relay (visibly indebted T2) needs critical discrimination.[14] The term unacknowledged translation has been used to cover the broad category of covert translations that includes covert relay. A noted eighteenth century literary polemic centered on Jervas’ accusation (1742) that Shelton’s Quixote passed into English by way of Lorenzo Franciosini’s Italian version (Ardila 2009: 69); Hu Shi, to give another example, was accused of using Thomas Carlyle’s translation of a Goethe quatrain (Findeisen 2003: 559). L3 translations of an interlingual plagiarism (L1>L2 plagiarism>L3, to all appearances an L1>L2 translation) are among the most difficult translation provenances to sort out, as they are covert by design (whether economic or aesthetic), and not always verbatim but stylistic or strategic calquings. While covert translation may be transitive or terminal, the poor quality of pirate translations makes them overwhelmingly terminal. Translation plagiarism can even occur within a single interliterary community. Rónai (2005: 49-54) tells of the case of classic novels commissioned into Brazilian Portuguese in which the translator merely replaces the continental Portuguese syntax and pronouns with the Brazilian counterparts, labels the translation a revised translation, and omits all credit to the original translator. Pym’s notion of weakly marked translations (Pym 1998: 60, cited in Pieta 2010: 8) may be invoked in such cases. Yet no concept can help us where we cannot discern such translations, and who can say how many there are? And ethically, is an L3 translation of an L2 plagiarism, carried out in good faith, itself a plagiarism?[15] Moreover, what do we make of the ethically abhorrent work that is nevertheless aesthetically catalytic? The specter of mistrust, in short, hangs over covert translations even when they move in legitimate channels. Documents with equal authenticity (e.g., EU legislation) are mutual translations, to all legal effects identical in force; a source text cannot claim either historical precedence or legal priority. The covert act therein lies in concealing difference, markedness, not from one’s parentage but from one’s siblings. The idea of translations that seem spontaneously generated, like the relationship of clones to their progenitors, may seem unnerving, much like a pseudotranslation, which usurps the space and status of the parent (or dramatically, Oedipally, of the father).

5.1. Indirect and Interlinear: Intuition and ‘Translucencies’

Gentzler (2001: 31), writing about creative writers without foreign language proficiency, notes that “[l]icense has been given to allow translators to intuit good poems from another language without knowledge of the original language or the culture…” License here seems to mean in the reading, but does that extend to the writing? In other words, should a licensed translation understood to be based on intuition rather than source knowledge access be evaluated by different criteria than unlicensed ones? Following Apter (1987: 181), we can mark this historical shift from philological accuracy (Edwardian and Victorian translation) to the age of intuitive translation. The sea change to the latter sensibility is often attributed to Ezra Pound, who paradoxically marshalled the resources of other eras and cultures in order to represent his own poetics, seeing in the poems what he needed, not what was there. Steiner remarks that Pound’s Lament of the Frontier Guard “…penetrates beneath [the surface] to restore what [the gloss by Ernest] Fenollosa has missed or obscured” (Steiner 1975: 358). To Steiner, such “translucencies” (Steiner borrows Eliot’s term) betray a collusive ignorance on the part of the translators and readers (Steiner 1975: 359): we think we know what the remote source ought to sound like because we invent it with every such act, and source language knowledge would only be a hindrance:

The Western translator […] is viewing his source, often via an intermediate paraphrase, as a feature, almost non-linguistic, of landscape, reported custom, and simplified history. In Pound’s China, in Logue’s Homer, ignorance of the relevant language is a paradoxical advantage. No semantic specificity, no particularity of context interposes itself between the poet-translator and a general, cultural-conventional sense of “what the thing is or ought to be like.”

Steiner 1975: 361; the emphasis is mine

And yet translating from trots is translating; it is a critical error to consider L2trot>L2 operations to not be translations simply because they are intralingual. Whether L1>L2trot> L2 is the only model, or if L1>L2trot>L3 is practiced, remains to be more fully explored, as do the different production chains involved. For example, some translators work L1>informant’s oral rendering or commentary into L2>L22; an example would be the 17th-19th century Muslim Tamil translation processes that openly acknowledged Arabic or Persian consultants (Ricci 2011: 60-61). Cases are known, too, of informants offering lists of errata from L2 translations to a prospective L3 translator who has no knowledge of L1. It is no leap to imagine workflows involving unacknowledged direct translation from an oral interlinear text: a covert oral interlinear translation. Not all trots are inherently self-effacing, however. In 1975, Naapet Kuchak’s Armenian verse was brought out with both interlinear trots and a stylized version by Levon Mkrtchian (Friedberg 1997: 176). Some cribs, too, have been included not for the translator but for the reader as an aid to learning the source language. Parallel phenomena include, for example, the transliterated version of The Dream of the Red Chamber, which had phonetic symbols for Manchu readers (Chan 2009: 330).

5.2. Support Translation

Dollerup’s term support translation brings to light a class of texts that translators use as part of their research but that fall out of reach of critical consideration, especially if we compare artifacts whose use has proven easier to quantify and qualify, for example, parallel texts. More study (particularly data-driven, corpus-based study) is needed, though we can hypothesize that support translations are consulted not for micro-level legacy (re-use) of phrases (as retranslators might use earlier translations – scrupulously or unscrupulously) but for providing a potential repertoire of translation shifts or strategies; in sum, an instance of expert modeling. Support translations, in this light, actually are supporting the translation process rather than providing a harvestable translation product. Dollerup himself frames his coinage here as the use of the whole of another text (relay) in contradistinction to the use of isolated fragments (support) (Dollerup 2000: 24). So it may be useful also, in short, to stress translatorial action or intervention in considering this term: after all, the support translation only exists as such when it is consulted for support. This principle perhaps is most visible in the (theoretically common) cases of L1>L3 via L2 support translations:

Figure 1

L1>L3 translation mediated by support translation

Less extensive support would appear in, for example, an L24 production from the L1 based on the other L2s. Different support-pivot hybrid models may be possible, including consulting L2s and L3s to produce an L3 or even L4 translation. We should observe that the term support translation is probably appropriate in cases in which translation is using at least three removes (e.g., L1>L2>L3); to call an instance of support translation a triangulation L2 and L22>L3 in which the translator has no knowledge of L1 would seem terminologically indiscriminate. Dollerup specifies that support translations do not include the target language into which one is working (Dollerup 2000: 24), though one could argue that other same-target translations should be considered support translations as well.

One more nuance to the discussion on support translation may be found in the migrations of the Lusophone African work, Os Vizinhos. Wolf and Fukari (2007: 156-158) describe how, when the text was translated into French, one of the contentious issues on the project was that the publisher and reviser were using the English translation as their only standard of comparison. Working from the Mozambican Portuguese original, the translators, in order to convince the publisher of the success of their French, had to show how the publisher’s English support was flawed. Here we are led to the conclusion that an unreliable translation supports only inasmuch as the supported translator or editor can evaluate it accurately and advantageously. Further research on support translation would do well to define how these texts are actually used, and to identify support translation subtypes (perhaps by distinguishing source types, passage lengths, the relationship of parallel texts to support translations, or such phenomena as the use of author concordances, unpublished, failed first commissions of translations provided by publishers, or translations of other works by the same author).

6. Sacred texts

Sacred texts deserve special comment in this survey. Bellos notes that indirect translation of scripture has a long history and

[…] is not a modern departure for the Bible. Only the Aramaic targums and the Greek Septuagint were translated directly from biblical Hebrew. The Armenian, Coptic, Old Latin, Syriac, Ge’ez, Persian, and Arabic translations of the Old Testament were done from the Greek; the Georgian Bible was probably first translated from Armenian (though it may have also used the Syriac and the Greek); the Old Gothic likewise, probably with some reference to Latin versions. Jerome used Hebrew and Aramaic texts to complement the Septuagint for his long-influential version of the Old Testament in Latin, and the original Greek for the New Testament. Early German translations of the Bible in the fifteenth century were done from Jerome’s Latin, as were the first Bibles in Swedish.

Bellos 2011a: 171-172

What lies behind the translation chains, the originals seeming to fade as new ones seem to appear, though they are translations? Toker argues that if we can claim,

[…] as Paul does, that the spirit (i.e. the signified) of the Bible is essentially separable from its letter (i.e. its signifier), just as the kernel of a fruit is distinct and separable from its shell, then one could argue that in translating the Old Testament it is possible to effect a transport of pure signified from Hebrew to Greek or any other language. Such a Pauline ‘transport,’ if it were possible, would alter only the signifier or the letter of the Torah – which is, at any rate, deemed unessential – and it would preserve the signified, that is, the spirit, of Holy Writ in its pristine glory. Hence, in the Pauline framework, the Bible is (w)holy translatable…

Toker 2005: 38

T2 appears harmonic with the very mission of Christianity, as opposed to, for example, the Talmudic model of language, in which translation runs headlong into the paradox of attempting to transform something essential with mere words (Toker 2005: 39). Yet the Pauline transport conception of translation would meet many ideological complications, especially in the perception that certain languages are truer, holier, and more spiritual. Bellos argues that the use of modern European translations as intermediary texts to seed new translations is nothing new, but in fact “[confirm and drive] the perception of English and Spanish, not of Hebrew or Greek, as ‘languages of truth’; their status as the source for Bible translation is hard to separate from the political, economic, and cultural status of the speakers of these two vehicular tongues” (Bellos 2011a: 171-172 ; the emphasis is mine).

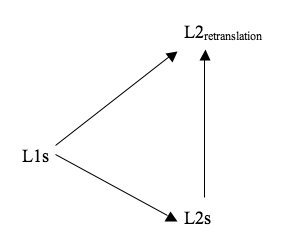

One of the key versions of the Bible taken as an original is of course the Authorized Version (AV), or the King James’ Bible. The title page of the 1611 first edition of the King James’ Bible (not yet called the Authorized Version) reveals the process of the translation’s genesis: “Newly Translated out of the originall tongues: & with the former Translations diligently compared and reused…” (The Holy Bible […] 1611).[16] In literature, this model (a variation on #3 relay above) would fall far from standard practice. Retranslations in the modern era from an L1 and L2 would violate the bounds of authorship as we define them since Romanticism:

Figure 2

L2 retranslation mediated by L2s and L1s

A comparison-revision/retranslation hybrid such as this one actually represents a sound methodology: the most successful parts are retained, the weaker parts shored up. This art consists, then, of trans-editing. If we conduct a thought experiment and imagine that all literature were suddenly unfettered from copyright, we might find such a model, and its corollaries, to be common: literary works in translation, being patchworks, then would perhaps reproduce the cumulative best efforts of translations past and present, but also would lose internal coherence, like the recycled text used in TMs built from different translators, a cento translation, if you will, or what Brian Mossop calls “collage translation” (Mossop 2006: 790, cited in Yuste Rodrigo 2008: 15). Modern copyright constrains translations to individual boundaries, which often means new translations cannot build upon successes the way, say, literary critics can – for instance, in their translations, literary translators cannot quote earlier translators beyond the smallest of non-random word strings.

7. Conclusion

Let us conclude by briefly considering the issue of evaluating indirect translations, and by indicating some future directions for research. One model of interliterary relations could broadly embrace a given text’s shifts from source through its different historical iterations; another might consider the translations vertically, that is, within the environment or field of other texts from its same remove from the source. Thus, with MT standing for mediating text: horizontally, ST>MT or MT>TTs; vertically, TTs. Pictorially, then, we can represent the scheme as in Figure 3:

Figure 3

Evaluating indirect translations: horizontal and vertical approaches

Toury (1995: 134) has identified that the uncertain boundaries between source and target in the case of Hebrew literature necessitates contextualizing all the agents involved in the translations; determining which texts, based on comparative deviations and correspondences, are derived from an original (‘mediated texts’); and sorting out the possible instances of what he calls compilative translations (several L2s>L3, L4 or L1, L2>L3).[17] Martens has undertaken work in this direction, elucidating not only the Goethe/Ossian configuration, but also how

Ulrich Plenzdorf’s Die Neuen Leiden des jungen W. (1973) echoes Goethe’s Werther and – via a German translation– J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye (1951). The English translation by Kenneth P. Wilcox (1979) draws on an English translation of Werther and, to an extent, on Salinger’s original.

Martens 2010

Boundaries, flows, traces, and directions are just some of the facets of indirect translation remaining to be studied. Co-translations with informants can be considered in more detail: Do trots function indexically, or how, according to creativity studies, do they contribute to the official target version? Controversies need settling with more data: Are major works more or less prone to being translated indirectly? We also need to know more about what translation practices have paralleled T2: What historical factors create conditions conducive to it? What characterizes the language of T2 translations? What role has T2 played in preserving (through manipulation) works that might have been lost? What impact do T2 translations have on ‘original’ works? How can we characterize not merely the fact of a translation’s indirectness but its particularities (e.g., an L3 reading of Shakespeare via German versus reading him via Japanese)? What can we make of the reception of T2 in both its overt and covert varieties? Once a literary work has been relay translated, do the shifts that subsequently occur become more radical, on the premise that representational ethics somehow apply less to a translation-turned-source? What are not only the ethical ramifications to the practice, but the legal ones? In collaborative T2, what cognitive factors imprint the translation product? And especially – going to the heart of the assumptions about T2 – what are the hallmarks of T2 quality? Scholarship has begun to answer some of Toury’s questions about preliminary norms and the directness of translation, the power concealed in the practice, and representational codings of T2 translations:

[I]s indirect translation permitted at all? In translating from what source languages/text types/periods (etc.) is it permitted/prohibited/tolerated/preferred? What are the permitted/prohibited/tolerated/preferred mediating languages? Is there a tendency/obligation to mark a translated work as having been mediated, or is this fact ignored/camouflaged/denied?

Toury: 1995: 130

Now, too, corpus tools can help detect the hitherto imperceptible marks of works having traveled indirectly. Significantly, too, trots can be considered, and studied, as part of T2 production chains, as interlingual translation artifacts rather than as ephemera. Textual provenance, whether provable or intuited, proves to still hold powerful sway over how we read and evaluate texts; well-traveled texts may have a harder time concealing their origins in the coming decades, but then too, as theory moves T2 from the shadows, they may have less reason to do so.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

The term indirect translation as used here should not be confused with any of the term’s other designations in translation studies, such as Gutt’s distinction in relevance theory between direct and indirect translation, which contrasts target-oriented translation with interpretive resemblance, or source-orientedness. Retranslation, incidentally, is intended throughout this study to mean new translations; some theorists take retranslation as a synonym for indirect translation; following Ringmar’s misgivings (2006: 2, note 6), the use of the same term for a remotely related concept seems like a complication for scholars. Pym, parenthetically, finds Dollerup’s terms unsatisfying: “The problem here seems to be that the ‘relay’ idea describes the action of the first translator… whereas what is significant is the action of the second translator […]” (Dollerup 2011: 83). In other words, for Pym, the translators’ roles, the relaying and the relayed, are blurred. He recommends the use of the terms indirect translation and mediated translation. Ibrahim, in turn, proposes trans-derivation: “A text could be said to have been trans-derived n number of times, to warn readers of changes” (Ibrahim 1994: 154).

-

[2]

At any given time, only one or two Swedish Academy members, who choose the Nobel Prize in Literature, has proficiency in non-European languages (Lovell 2006: 31).

-

[3]

“Den erreicht es nicht mit Stumpf und Stiel, aber in ihm steht dasjenige, was an einer Übersetzung mehr ist als Mitteilung. Genauer lässt sich dieser wesenhafte Kern als dasjenige bestimmen, was an ihr selbst nicht wiederum übersetzbar ist.” (Benjamin 1980:15)

-

[4]

Most theorists reject or strongly challenge back translation. Ozolins (2009) presents a defense of the practice as a potential way to strengthen intercommunication and translator agency.

-

[5]

Anonymous (2003): Twice Removed: the baffling phenomenon of the translated and re-translated text. The complete review quarterly. IV(4). Visited on 28 October 2011, <http://www.complete-review.com/quarterly/vol4/issue4/doubletd.htm>.

-

[6]

UNESCO (22 November 1976): Recommendation on the Legal Protection of Translators and Translations and the Practical Means to improve the Status of Translators. Final Acts of the General Conference (General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, Nairobi, 22 October – 30 November 1976). Visited on 8 November 2011, <http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=13089&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html>.

-

[7]

“Cuando no sea posible realizar la traducción a partir del texto original y el traductor utilice una ‘traducción-puente,’ deberá, para hacerlo, contar con el permiso del autor y mencionar el nombre del traductor a cuyo trabajo recurra.” ACE-Traductores (n. d.): Código deontológico - El CEATL propone… Visited on 10 June 2012, <http://ace-traductores.org/Codigo_deontologico>.

-

[8]

Translatology (30 December 2010): Cinderella: Conclusions. Unprofessional translation (Anonymous blog) Visited on 2 November 2011, <http://unprofessionaltranslation.blogspot.com/2010_12_01_archive.html>

-

[9]

Gombrowicz, Witold (2000): Ferdydurke. (Translated by Danuta Borchardt) New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, “Translator’s Note,” xvi.

-

[10]

The fables of Bidpai have undergone one of the longest chains involving multiple adaptations: Sir Thomas North produced “the English version of an Italian adaptation of a Spanish translation of a Latin version of a Hebrew translation of an Arabic adaptation of the Pahlevi version of the Indian original” (Matthiessen 1931: 63n cited in Höfele and von Koppenfels 2005: 25).

-

[11]

We may point to a strange case in the epistolary genre, Marianna Alcoforado’s Lettres portugaises (Letters of a Portuguese Nun); its provenance is not conclusively French, nor is it clear that it is an original work.

-

[12]

Intralingual plagiarism of translations appear as well; one such episode gained notoriety in the case of Pujante v. Vázquez Montalbán (Turell 2008: 292), which was actually litigated. See Turell 2004 for the role of quantitative linguistic evidence in that case.

-

[13]

Helder, Herberto (1968): Introduction toO bebedor nocturno (1968). Lisboa: Portugália. Cited in Buescu and Ferreira Duarte 2007: 174.

-

[14]

Domínguez Pérez (2008: 179) uses traducción indirecta manifiesta and traducción indirecta encubierta (visible indirect translation and concealed indirect translation).

-

[15]

On this, see Sakai and Solomon’s (2006) discussion of Malian writer Yambo Ouologuem’s lifting of parts of Graham Greene’s work It’s A Battlefield for his Le Devoir de violence. See also Venuti (2011), particularly for a consideration of authorial boundaries vis-à-vis the categories of adaptation, imitation, and version. Randall (2001: 138-139) divides adaptations from (interlingual) plagiarism thus: Adaptations – reworking of previous literary matter without parodic intent – are often confused with plagiarism, or else plagiarisms are recast in the light of ‘adaptation’ in order to justify borrowings on aesthetic grounds. Corneille’s Le Cid could most effectively be seen as an adaptation of the Spanish play for the French stage; Régine Deforges’s La bicyclette bleue could be seen as a French adaptation of Gone with the Wind – the problem being, of course, that adaptation is only legal on copyrighted work with the permission of the owner of the copyright.

-

[16]

The Holy Bible, conteyning the Old Testament, and the New (1611): London: Robert Barker. Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text & Image. Visited on 12 December 2013, <http://sceti.library.upenn.edu/sceti/printedbooksNew/index.cfm?TextID=kjbible&PagePosition=1>.

-

[17]

Levý (2011: 173) finds compiled translations to be of theoretical, but rarely of literary, value. He notes that Schunemann’s Don Giovanni (1940) was compiled from fifty previous translations.

Bibliography

- Ackerman, Sherry L. (2008): Behind The Looking Glass. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Pub.

- Almberg, S.P.E. (1995): Retranslation. In: Sin-Wai Chan, David E. Pollard, eds. An Encyclopaedia Of Translation: Chinese-English, English-Chinese. Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 925-930.

- Apter, Ronnie (1987): Digging for the Treasure: Translation after Pound. New York: Paragon House.

- Ardila, J.A.G. (2009): The Cervantean Heritage. London: Legenda.

- Bakhtin, Mikhail M. (1981): The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays by M.M. Bakhtin. (Translated by Caryl and Michael Holquist) Michael Holquist, ed. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Barnstone, Willis (1993): The Poetics of Translation: History, Theory, Practice. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Bielsa, Esperança and Bassnett, Susan (2009): Translation in Global News. London/New York: Routledge.

- Bellos, David (2011a): Is That a Fish in Your Ear? Translation and the Meaning of Everything. New York: Faber and Faber.

- Bellos, David (2011b): The Englishing of Ismail Kadare: notes of a retranslator. The Complete Review Quarterly. 6(2). Visited on 28 November 2011, http://www.complete-review.com/quarterly/vol6/issue2/bellos.htm.

- Benjamin, Walter (1968): The Task of the Translator. In: Walter Benjamin. Illuminations. (Translated by Harry Zohn) Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 69-82.

- Benjamin, Walter (1980): Gesammelte schriften. In: Rolf Tiedemann and Hermann Schwepenhauser, eds. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

- Bernofsky, Susan (2005): Foreign Words: Translator-authors in the Age of Goethe. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

- Buescu, Helena and Ferreira Duarte, João (2007): Communicating voices: Herberto Helder’s experiments in cross-cultural poetry. Forum for Modern Language Studies. 43(2):173-186.

- Chan, Leo Tak-hung (2009): Translation, transmission, and travel: culturalist theorizing on ‘outward’ translations of classical Chinese literature. In: Leo Tak-hung Chan. One into Many: Translation and the Dissemination of Classical Chinese Literature. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 321-346.

- Chesterman, Andrew (2001). Proposal for a Hieronymic oath. In: Anthony Anthol, ed. The Return to Ethics. The translator: Studies in Intercultural Communication. 7(2):139-54.

- Cheung, Kai-chong (2003): The Haoqiu zhuan, the first Chinese novel translated in Europe: with special reference to Percy’s and Davis’s renditions. In: Leo Tak-hung Chan.One into Many: Translation and the Dissemination of Classical Chinese Literature. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 29-37.

- Dollerup, Cay (2000): ‘Relay’ and ‘Support’ Translation. In: Andrew Chesterman, Natividad Gallardo, San Salvadoret al., eds. Translation in Context: Selected Contributions from the EST Congress, Granada 1998. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 17-26.

- DomínguezPérez, Mónica (2008): Las traducciones de literatura infantil y juvenil en el interior de la comunidad interliteraria específica española (1940-1980). Santiago de Compostela: Universidade de Santiago de Compostela.

- Ellis, Roger (2008): Oxford History of Literary Translation In English - Volume 1: to 1550. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

- Findeisen, Raoul David (2003): Does the East Asian – European interliterary communication in the Late Qing-Late Meiji periods offer a model for a globalized literature? Canadian Review of Comparative Literature/Revue canadienne de littérature comparée. 30(3-4):555-564.

- Friedberg, Maurice (1997): Literary Translation in Russian: A Cultural History. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Gambier, Yves (2003): Working with relay: an old story and a new challenge. In: Luis Pérez González, ed. Speaking in Tongues: Language across Contexts and Users. València: Universitat de València, 47-66.

- Gasché, Rudolphe (1986): Saturnine vision and the question of difference: reflections on Walter Benjamin’s theory of language. Studies in Twentieth Century Literature. 11(1):69-90.

- Gaskill, Howard (2002): Review. Holderlin’s Sophocles. Translation and Literature. 11(2):270-278.

- Gentzler, Edwin (2001): Contemporary Translation Theories. Clevedon/Buffalo: Multilingual Matters.

- Gerhardt, Mia (1963): Art of Story-Telling: A Literary Study of the Thousand and One Nights. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Gutt, Ernst-August (1992): Relevance Theory: A Guide to Successful Communication in Translation. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

- Heilbron, Hohan (2000): Translation as a cultural world-system. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology 8(1):9-26.

- Hermans, Theo (1999): Translation in Systems: Descriptive and Systemic Approaches Explained. Manchester: St. Jerome.

- Höfele, Andreas and Werner Von Koppenfels (2005): Renaissance Go-betweens: Cultural Exchange in Early Modern Europe. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter.

- Ibrahim, Hasnah (1994): A case for a spectral model. In: Cay Dollerup and Anne Lindegaard, eds. Teaching Translation and Interpreting 2: Aims, Insights, Visions. [Selection of] Papers from the Second Language International Conference (Elsinore, Denmark, June 4-6, 1993). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 151-156.

- Lambert, José (2006): Literatures, Translation, and (De)colonization. In: Dirk Delabastita, Lieven d’Hulst and Reine Meylaerts. Functional Approaches to Culture and Translation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 87-104.

- Levý, Jiři (2011). The Art of Translation. (Translated by Patrick Corness) Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Lie, Raymond S.C. (2000): Indirect translation. In: Olive Classe, ed. Encyclopedia Of Literary Translation into English. London/Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 708-9.

- Lifshey, Adam (2010): Specters of Conquest: Indigenous Absence in Transatlantic Literatures. New York: Fordham University Press.

- Loulakaki-Moore, Irene (2010): Seferis and Elytis as translators. Bern/Switzerland/New York: Peter Lang.

- Lovell, Julia (2006): The Politics of Cultural Capital: China’s Quest for a Nobel Prize in Literature. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

- Marín Lacarta, Maialen (2008): La traducción indirecta de la narrativa china contemporánea al castellano: ¿síndrome o enfermedad? 1611: revista de historia de la traducción: a journal of translation history/Revista d’història de la traducció. 2(2). Visited on 22 December 2011, http://www.traduccionliteraria.org/1611/art/marin.htm.

- Maronitis, Dimitris N. (2008): Intralingual translation: genuine and false dilemmas. In: Alexandra Lianeri and Vanda Zajko, eds. Translation and the Classic: Identity as Change in the History of Culture. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

- Martens, Dorothea (2010): Intertextuality in translation: modeling the textual relationship in translation [abstract]. New Voices in Translation Studies. 6. Visited on 28 December 2011, https://www.iatis.org/images/stories/publications/new-voices/Issue6-2010/abstract-martens-2010.pdf.

- Matthiessen, Francis (1931): Translation: An Elizabethan Art. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Miner, Robert (1972): Aesop as litmus: the acid test of children’s literature. Children’s literature. 1:9-15.

- Mossop, Brian (2006): Has computerization changed translation? Meta. 51(4):787-805.

- Ozolins, Uldis (2009): Back translation as a means of giving translators a voice. Interpreting and translation. 1(2):1-13.

- Pacheco Pinto, Marta (2009/2010): Translating the Oriental otherness at the turn of the 19th century. VI Congresso Nacional Associação Portuguesa de Literatura Comparada / X Colóquio de Outono Comemorativo das Vanguardas – Universidade do Minho. 1-20. Visited on 29 December 2011, http://ceh.ilch.uminho.pt/Pub_Marta_Pinto.pdf.

- Pajares, Frank (n. d.): Oráculo manual i arte de prudencia dacada de los sforismos que se discurren en las obras de Lorenço Gracián, Spanish text: edición de Emilio Blanco, Cátedra, S. A., 1995 English translation by Professor Frank Pajares. Visited on 3 January 2012, http://www.des.emory.edu/mfp/Gracian/GracianFAQ.html.

- Paz, Octavio (1992): Translation: Literature and Letters. Translation by Irene del Corral. In: Rainer Schulte and John Bighenet, eds. Theories of Translation: An Anthology of Essays from Dryden to Derrida. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 152-62.

- Pederson, Jan (2011): Subtitling Norms for Television: An Exploration Focussing on Extralinguistic and Cultural References. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Pérez González, Luis (2003): Speaking in Tongues: Language Across Contexts and Users. València: Universitat de València.

- Pieta, Hanna (2010): Portuguese translations of Polish literature published in book form. In: Omid Azadibougar, ed. Translation Effects.Selected papers of the CETRA research seminar intranslation studies 2009. 1-25. Visited on 8 January 2012, http://www.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/papers.html.

- Pym, Anthony (1998): Method in Translation History. Manchester: St. Jerome.

- Pym, Anthony (2011): Translation research terms: a tentative glossary for moments of perplexity and dispute. In: Anthony Pym, ed. Translation Research Projects 3. Tarragona, Spain: Intercultural Studies Group. Visited on 15 December 2011, http://isg.urv.es/publicity/isg/publications/trp_3_2011/isgbook3_web.pdf#page=67.

- Quentel, Gilles (2006): The translation of H.C. Andersen’s fairy tales in the European literary scene. Revue des littératures de l’Union Européenne. 4:87-99.

- Radó, György (1975): Indirect translation. Babel. 21(2):51-59.

- Randall, Marilyn (2001): Pragmatic Plagiarism: Authorship, Profit, and Power. Toronto/Buffalo: University of Toronto Press.

- Rendall, Steven (2000): A note on Harry Zohn’s translation. In: Lawrence Venuti, ed. The Translation Studies Reader. New York/London: Routledge. 23-25.

- Ricci, Ronit (2011): Islam Translated: Literature, Conversion, and the Arabic Cosmopolis of South and Southeast Asia. Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press.

- Ringmar, Martin (2006): ‘Roundabout routes.’ Some remarks on indirect translations. In: Francis Mus, ed. Selected papers of the CETRA research seminar in Translation Studies 2006. Visited in November 2011, http://www.kuleuven.be/cetra/papers/Papers2006/RINGMAR.pdf.

- Robinson, Douglas (1998): Pseudotranslation. In: Mona Baker, ed. Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies. London/New York: Routledge, 183-185.

- Rónai, Paulo (2005): Notes toward a history of literary translation in Brazil. (Translated by Tom Moore) Translation Review. 69:49-53.

- Ruthvin, Kenneth K. (2001): Faking Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Sakai, Naoko and Solomon, Jon (2006): Translation, Biopolitics, Colonial Difference. Hong Kong/London: Hong Kong University Press/Eurospan [distributor].

- Shuttleworth, Mark and Cowie, Moira (1997): Dictionary of Translation Studies. Manchester, UK: St. Jerome.

- Shvabrin, Stanislav Anatolyevich (2007): Vladimir Nabokov as Translator: The multilingual Works of the Russian Period. Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor in Philosophy. Los Angeles: UCLA.

- St. André, James (2003a): Modern translation theory and past translation practice: European translations of the Haoqiu zhuan. In: Leo Tak-hung Chan, ed. One into Many: Translation and the Dissemination of Classical Chinese Literature. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 39-65.

- St. André, James (2003b): Retranslation as argument: canon formation, professionalization, and rivalry in 19th century sinological translation. Cadernos de Tradução. 11(1):59-93.

- Steiner, George (1975): After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Toker, K. Onur (2005): Prophecy and tongues: St. Paul, interpreting, and building the house. In: Lynne Long, ed. Translation and Religion: Holy Untranslatable? Clevedon/Buffalo: Multilingual Matters, 33-40.

- Toury, Gideon (1980): In Search of a Theory of Translation. Tel Aviv: The Porter Institute for Poetics and Semiotics.

- Toury, Gideon (1995): Descriptive Translation Studies and Beyond. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 53-69.

- Toury, Gideon (2002): Translation and reflection on translation. In: Robert Singerman, ed. Jewish Translation History. A Bibliography of Bibliographies and Studies. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, ix-xxxvi.

- Turell, M. Teresa (2004): Textual kidnapping revisited: the case of plagiarism in literary translation. Forensic Linguistics. 11(1):1-26.

- Turell, M. Teresa (2008): Forensic linguistic evidence. In: John Gibbons and M. Teresa Turell, eds. Dimensions of Forensic Linguistics. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 213-300.

- Venuti, Lawrence (2011): The poet’s version; or, an ethics of translation. Translation Studies. 4(2):230-247.

- Wegner, Paul D. (1999): Journey from Texts to Translations: The Origin and Development of the Bible. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Books.

- Wolf, Michaela and Fukari, Alexandra (2007): Constructing a Sociology of Translation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Yu, Pauline (2007): Travels of a culture: Chinese poetry and the European imagination. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 151(2):218-229.

- Yuste Rodrigo, Elia (2008): Topics in Language Resources for Translation and Localisation. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

L1>L3 translation mediated by support translation

Figure 2

L2 retranslation mediated by L2s and L1s

Figure 3

Evaluating indirect translations: horizontal and vertical approaches

10.7202/014342ar

10.7202/014342ar