Résumés

Abstract

Recent research in audiovisual translation has focussed on the language of both original and translated dialogue, revealing different degrees of alignment between fictional dialogue and spontaneous conversation. In this context, demonstratives deserve special attention as they are major means to highlight segments of the current discourse and extra-linguistic reality in speech and may play a significant role in cinematic language as well. Furthermore, demonstratives are an area of dissimilarity between languages, with their translation being potentially subject to interference from the source to the target text. Through a quantitative corpus-based approach, this study explores to what extent demonstratives occur in the language of Italian dubbing, how similar in this respect dubbed dialogue is to Italian spoken language and what translation operations may account for the observed translation outcomes. Drawing on a small English-Italian parallel corpus of film dialogue, all English demonstrative pronouns have been coded for syntactic role, pragmatic function and translation operation. Results show that demonstratives occur to a lesser extent in dubbed film language vis-à-vis both Italian conversation and the source English dialogues. These findings are discussed in terms of the cross-linguistic contrast between Italian and English as well as the convergence of dubbed dialogue towards the model of original Italian film language.

Keywords:

- demonstratives,

- dubbing,

- spoken language,

- language contrast,

- translation operations

Résumé

En matière de traduction audiovisuelle, des recherches récentes se sont concentrées sur le langage employé aussi bien dans le dialogue original que dans le dialogue traduit, révélant ainsi différents niveaux d’alignement entre le dialogue fictif et la conversation spontanée. Dans ce contexte, les démonstratifs jouent un rôle décisif puisqu’ils constituent un moyen fondamental pour mettre en évidence des segments du discours et de la réalité extralinguistique de la langue parlée et qu’ils peuvent aussi jouer un rôle déterminant dans le langage cinématographique. En outre, les démonstratifs constituent souvent un terrain de contraste entre les langues, et leur traduction peut être exposée à des interférences dans le passage de la langue source vers la langue cible. Grâce à une approche quantitative et au recours aux corpus, la présente étude examine la fréquence d’occurrence des démonstratifs dans le langage du doublage italien et analyse les similarités, quant à cet aspect, entre le dialogue doublé et l’italien parlé ; de plus, elle s’interroge sur les opérations de traduction pouvant donner lieu aux résultats observés. Ainsi, tous les pronoms démonstratifs d’un petit corpus parallèle anglais-italien de dialogues filmiques ont été codifiés selon trois aspects : le rôle syntaxique, la fonction pragmatique et l’opération de traduction. Les résultats démontrent que le recours aux démonstratifs est beaucoup plus restreint dans le doublage que dans la conversation en italien et que dans les dialogues source en anglais. Ces résultats ont été évalués sous l’angle du contraste interlinguistique entre l’italien et l’anglais et de la convergence du dialogue doublé vers le modèle du langage filmique italien original.

Mots-clés :

- démonstratifs,

- doublage,

- langue parlée,

- contraste linguistique,

- opérations de traduction

Corps de l’article

1. Introduction

Recent research on film language has emphasized the need for a thorough assessment of simulated spoken language in audiovisual translation. On the one hand, film dialogue is planned and carefully worded to involve viewers emotionally and aesthetically in “worlds that transcend the here and now” (Gordon, Gerrig et al. 2009: 71-72). On the other hand, films offer a credible imitation of reality in their staging of people, objects and places, but also in their representation of spontaneous spoken language (see Quaglio 2009; Tomaszkiewicz 2009). Previous research has in fact revealed different degrees of alignment between translated audiovisual dialogue and natural conversation, with some linguistic features acting as privileged carriers of orality and others typifying dubbing as a variety of film language (Marzà and Chaume Varela 2009; Pavesi 2008a; 2009; Romero-Fresco 2009; Valdéon 2008).

Within the investigation of translated audiovisual dialogue, demonstratives deserve special attention for a number of reasons. First, demonstratives are central and frequent pragmatic features in face-to-face interaction as they orient the hearer to entities, people and ideas, and are capable of structuring whole texts through their referential and cohesive functions (Becher 2010; Diessel 1999; 2006; Halliday and Hasan 1976; Levinson 1983; 2004; Lyons 1977). Second, as demonstratives point to some aspects of the speech situation and, prototypically, to the physical, visual and generally sensorial context surrounding interlocutors, they may play a considerable role in cinematic language. Here different semiotic codes interact, with verbal language often referring ostensively to entities present visually or acoustically in the scene. At the same time, demonstratives may highlight the connectivity of audiovisual duologues, the main form of dialogue in films (Kozloff 2000). Third, from a contrastive perspective, demonstratives – a universal feature of language and a salient area of dissimilarity between languages (see Diessel 1999; Dixon 2003; Wu 2004; Da Milano 2005; 2007) – are potential triggers of textual restructuring induced by language contrast when moving from the source to the target text. It can therefore be expected that the translation outcomes in dubbing will also be influenced by the differences between source language and target language. The first two reasons for the relevance of demonstratives in the investigation of film translation have to do with the multimodal context in which screen dialogue is embedded; the third one specifically pertains to translation as characterised by typical and recurrent features, identified as laws, universals, or universal tendencies of translation (see Toury 1995/2012; Baker 1996; Mauranen 2008).

Through a corpus-based approach to translation and translated language, this study quantitatively explores the three issues introduced above and addresses the following research questions:

To what extent do demonstratives occur in the language of Italian dubbing translations, and more specifically, how does dubbed Italian place itself with reference to both Italian spoken language and Italian original film dialogues?

What translation operations contribute to the observed translation outcomes, i.e., how do demonstratives in the source texts transfer to the target texts and what systematic translation patterns can be identified?

What are the cumulative effects of the observed translation shifts in relation to the functions performed by demonstratives in the multimodal context of film?

This study is both target- and source-oriented, as it contrasts demonstratives in dubbed Italian, related target varieties, and the English source texts by drawing on an English-Italian unidirectional, parallel corpus of film dialogue compared to reference corpora. At first, the investigation will be carried out on demonstrative pronouns only, as truly indexical items whose interpretation totally rests on either the situational context or the surrounding discourse (see Rocha 2010). This study is thus mainly descriptive, although its findings may be evaluated from a wider explanatory perspective combining features of cross-linguistic contrast and the specificity of film language as opposed to other language varieties.

This article is organized as follows. Sections 1.1 and 1.2 give a brief sketch of demonstratives with special reference to spoken English, spoken Italian and major aspects of contrast between the two languages. Section 2 describes the corpus of film dialogue, and section 3, the frequencies of demonstratives in dubbed film dialogues compared with Italian spoken language and original film dialogues. Section 4 introduces the source-based analysis and illustrates the translation operations from the source to the target texts, whereas results are presented and discussed in section 4.1. A closer look at the influence of language contrast is given in section 4.2. Section 4.3 presents the additions to the target text, whereas 4.4 briefly deals with exophores and endophores in the corpus. The implications of the translation outcomes for the target texts are discussed in section 5, and the conclusions are drawn in section 6.

1.1 A sketch of demonstratives

Demonstratives belong to the repertoire of means the speaker can resort to in order to draw attention to segments of the extra-linguistic reality or current discourse (Halliday and Hasan 1976; Lyons 1977; Levinson 1983; Diessel 1999; 2006). In languages that have two-term systems, demonstratives are traditionally distinguished into proximal and distal ones, depending on the relative proximity (Engl. this), or distance (Engl. that) of the reference object in relation to the speaker or the speaker and hearer (see Da Milano 2005; Diessel 1999; 2006). Despite this seemingly clear-cut semantic differentiation, the perception and conceptualisation of relative distance are far from fixed or shared among speakers and across languages in that the choice of spatial demonstratives is known to be influenced by contextual and affective factors (Biber, Johansson et al. 1999; Carter and McCarthy 2006; Lakoff 1974; Mason and Şerban 2003). Demonstratives can be also analysed in terms of their focussing function. In general, entities identified by a demonstrative pronoun – compared with other referential means such as the third person pronoun it and its equivalents in other languages – stand out more and explicitly bind the interlocutor to the speech event and the situational context (Kirsner 1979: 360; Strauss 1993: 404; 2002). More specifically, Diessel (2006) identifies demonstratives as the means that prototypically and universally index “joint focus of attention.” This function is basic in both communication and social cognition as it coordinates the speaker’s and the addressee’s attention on a specific, shared object of reference. “While there are many linguistic means that speakers can use to coordinate a joint attentional focus, there is no other linguistic device that is so closely tied to this function than demonstratives [emphasis added]” (Diessel 2006: 469). Consequently, still according to Diessel, demonstratives fulfil two interrelated functions: the first one is to locate the referent relatively to the deictic centre, and the second one, “to coordinate the interlocutors’ joint attentional focus” as essential to the “meeting of minds” that occurs in human communication (2006: 468-469).

Pragmatically, two major referential uses of demonstratives can be identified: (i) exophoric and (ii) endophoric (Diessel 1999; 2006; Halliday and Hasan 1976). Exophoric demonstratives are taken to be prototypical deictics shifting interlocutors’ attention onto items of the situational context (Diessel 1999: 93-114). These are here interpreted to include concrete objects (1), as well as – by extension – more abstract situations, conditions and states of minds (2). Endophoric demonstratives, on the other hand, identify either individual elements or whole segments, propositions or illocutionary acts within the verbal text. Hence they are further subdivided into anaphoric (3) and discourse deictic demonstratives (4),[1] depending on whether they are co-referential with a previous noun phrase or refer to a proposition and focus on aspects of meaning expressed by the ongoing discourse. (All examples are taken from the Pavia corpus of film dialogue, see Appendix.)

In spoken language (both English and Italian), endophoric demonstratives often perform a discourse deictic function, i.e. they shift the listeners’ focus of attention on textual portions whose delimitation exceeds individual units and may at times be difficult to establish (Rocha 2010: 18).[2] As for overall frequencies, demonstratives are much more numerous in speech than in written language, both in English and in Italian. In both spoken languages, they most frequently fulfil an endophoric function (see Botley and McEnery 2001; Gaudino-Fallegger 1992; Strauss 2002).

1.2 Cross-linguistic contrasts

English and Italian share a binary system of proximal and distal demonstrative pronouns, with English presenting the two series this-these and that-those, and Italian, the two series quest- and quell-,[3] respectively (Da Milano 2005; 2007). The two languages, however, are at variance in several respects. First of all, they behave differently at the syntactic level in the pragmatic constraints for the use of subject and object pronouns. Clause subjects are obligatory in English, but not in Italian, where the grammatical person is already marked on the verb (e.g., Serratrice 2002). Object pronouns as well exhibit a different syntactic behaviour in the two languages, as they are placed postverbally in English, whereas in Italian they are most often placed preverbally if they are clitics (e.g., I don’t want it vs. Non lo voglio). In Italian, therefore, subjects and postverbal objects are realised as demonstratives only if the speaker wishes to express additional discoursal and pragmatic meanings. That is, demonstratives are strong forms of reference, occurring when entities are highlighted or difficult to access, as when a topic is introduced for the first time in discourse or when two referents are in competition for anaphora (Berretta 1985; Serianni and Castelvecchi 1991). Weaker forms of reference are available and often preferred in Italian, such as zero anaphora, unexpressed subjects or clitic pronouns (Cardinaletti 2009: 44). Interestingly, in the perspective of cross-linguistic contrast, Goethals has suggested that varying degrees of markedness or grammaticalisation account for observed greater or lesser reliance on demonstratives in given language pairs (2007: 95). Consequently, as for the contrast at hand, Italian demonstratives would be more marked or less grammaticalised than their English counterparts.

Spoken English and spoken Italian also diverge in the choice of demonstratives, with English distal demonstratives being considerably more frequent and less marked than proximal ones (Lyons 1977: 646), while the opposite occurs in Italian, where proximals are more frequent and possibly less marked than distals (Gaudino-Fallegger 1992: 161-162).[4] In particular, a major mismatch can be noticed in endophora. When referring back to previous portions of text in discourse deixis, English favours the distal demonstrative pronoun that, unless reference is made by the same speaker in the same turn (Lakoff 1974). For this reason, the pronoun that can be described as a typical index of interactivity and is in fact more than seven times as frequent as this in English conversation (Biber, Johansson et al. 1999: 349). In spoken Italian, by contrast, it is the proximal demonstrative pronoun questo that mostly picks up portions of surrounding discourse, whereas the endophoric quello is mainly confined to highly grammaticalised cataphors, such as in quello che (what) in the following example:

The complex configuration of demonstratives and language contrasts just outlined foreshadows a problematic area in translation (see Richardson 1998: 139), as suggested by previous work on other language pairs. Mason and Şerban (2003), investigating narrative texts translated from Rumanian into English, have argued that the systematic shifts from proximal to distal deixis they observed produce more detached target texts. Goethals (2007), analysing a bidirectional parallel corpus, also discusses the occurrence of shifts in the translation of demonstratives, some of which are clearly related to differences between the two languages considered: Dutch and Spanish. Rocha’s (2010) corpus-based study of the pronoun this translated into Portuguese has also shown that demonstratives are an area highly susceptible to restructuring when moving from one language to another.

2. The corpus

The empirical basis of the present study is provided by the Pavia corpus of film dialogue, a unidirectional parallel corpus of American and British film dialogues dubbed into Italian.[5] All films were manually transcribed both in their original and translated versions, for a total of 117,956 and 111,865 running words in the English and Italian components respectively. The table provided in Appendix lists the 12 films included in the corpus at the moment of analysis, the information pertaining to the original versions (year of release, director and country of production), the title and year of release of their Italian version, the number of running words in each component and the name of the Italian translator-dialogue writer.

The films in the corpus are believed to be good exemplars of contemporary “conversational” films, the sampling cutting across traditional genres to include films which mainly portray spontaneous face-to-face interactions of different kinds (see Freddi and Pavesi 2009 for further details on the corpus and methodology).

All English demonstrative pronouns in the corpus have been manually annotated for syntactic role (subject, direct object, object of preposition) and pragmatic function (exophoric, endophoric) in the source texts, and translation operation from English into Italian. A slightly different annotation system has been applied to the target texts to account for the demonstrative pronouns added during the translation process. No further distinction within endophora between anaphora and discourse deixis has been drawn at this stage as an initial sampling of the data showed that in film dialogue endophoric demonstrative pronouns almost exclusively perform a discourse deictic function. The transcribed and annotated texts have been investigated via concordance lists extracted with the programme AntConc 3.2.1.w.[6]

3. Frequency of demonstrative pronouns in dubbed Italian and related genres

In order to position dubbed language in relation to the linguistic repertoire of the target community, the frequencies of occurrence in the dubbed texts have been compared to those in spontaneous spoken language, since this is the variety of language audiovisual dialogue is expected to imitate so as to provoke viewers’ immersion, feeling of spatial presence and transportation into the film’s fictional world (Green, Brock et al. 2004). To this aim, the frequency data from the dubbed component of the Pavia corpus of film dialogue have been examined with reference to the Lessico di frequenza dell’Italiano Parlato (LIP), a major reference corpus of spoken Italian (De Mauro, Mancini et al. 1993). The occurrences in the first section of the LIP corpus are reported, consisting of face-to-face bidirectional exchanges with free turn-taking (i.e., various types of conversation), together with those of the whole corpus, including a wider spectrum of spoken language productions (De Mauro, Mancini et al. 1993: 39-41).

As shown in Table 1, the frequency of demonstrative pronouns in dubbed language is below that of the reference corpus, with demonstratives being about half those in conversation (52.0%) and just over two thirds (71.0%) of those in the whole LIP.

Table 1

Demonstrative pronouns in dubbed language and in Italian spoken language[*]

Quantitatively, these results identify deixis through demonstratives as an area of divergence between the language used in dubbing and the target community’s average spoken language, with fewer demonstratives resulting in fewer explicit references to the verbal and non-verbal context.[7] This may mean less intensity on the speaker’s part in guiding the listener to pay attention to selected textual and contextual items to establish a joint focus of attention. The two following excerpts show the different attentional focus evoked by the presence or the absence of a demonstrative in the Italian translations. In excerpt (6), taken from the Italian version of Notting Hill, Notting Hill,[8] William comments on the full body scuba diving gear that Spike is wearing. Strong attention is called upon the outfit that is shown on the screen, which Spike is pointing to.

In the following excerpt (7a), on the other hand, a subjectless interrogative clause reduces the verbal salience of the referent (Kirsner 1979: 359), whereas the use of the demonstrative pronoun, as shown in (7b), would have foregrounded the entity and made it more prominent to the viewer.

Excerpt (7a) shows a linguistically implicit reference in which the referent object, i.e. the documents, appears on the screen and is clearly Ed’s and his interlocutor’s shared focus of attention. It should be noticed that (7b) – the literal translation of the original “This is the only thing that you have?” – would be perfectly natural in Italian.

If, on the ground of their frequencies, demonstratives cannot be included among the privileged carriers of orality in dubbed Italian (Pavesi 2008a; 2009), an accurate account of film translation can only be obtained by evaluating the structure of dubbed dialogue with reference to original film dialogue in the target language. Dubbed language is typified by a fictional dimension (Romero-Fresco 2009) and shares with original, non-translated audiovisual dialogue its status of language “written to be spoken as if not written” (Gregory 1967: 191-192), whose communicative functions and conditions of production exceed the immediacy of natural conversation. The purposes of such scripted language can be assimilated to those of conversation at one communication level, but at a higher level they are to inform, narrate, entertain and involve viewers (see Bubel 2008; Kozloff 2000; Romero-Fresco 2009). The careful planning and repetitive editing underlying this unidirectional creation are therefore likely to result in a language containing features that diverge from spontaneous, on-line and multi-party speech production.

For these reasons, the frequencies of demonstrative pronouns in the Pavia corpus of film dialogue have been compared to those in the Forlì corpus of screen translation (Forlixt 1, first release), a multimedia database developed at the University of Bologna at Forlì comprising dubbed as well as original films (see Heiss and Soffritti 2008; Valentini 2008). Although not all the parameters exactly match those of the Pavia corpus of film dialogue, the Forlixt 1 component of original Italian provides a good basis for comparison. The examination of Forlixt 1 does suggest that original Italian film language as well contains strikingly fewer demonstrative pronouns than major spoken varieties of the language (see Table 2).

Table 2

Italian demonstrative pronouns in the Pavia corpus of film dialogue, Forlixt 1 and LIP[*]

These results quantitatively indicate that dubbed language is orientated towards original film language, which appears to be further removed from Italian speech. In other words, dubbed language appears to be placed between original film dialogue and spoken language, but closer to the former. Since a degree of alignment between Italian dubbed and original film language has emerged from previous investigations on sets of spoken language features, including personal pronouns and marked word orders (Pavesi 2008a), these results interestingly confirm the claim that the language of audiovisual dialogue dubbed from English into Italian tends to gravitate towards the simulated orality of original Italian productions (see also Alfieri, Motta et al. 2008).

4. Source-oriented analysis: translation operations

To fully evaluate the status of demonstratives in audiovisual translation, the comparison between dubbed language and related genres of the target language should be combined with a close comparison between source and target texts. To this end, the films in the corpus have been closely examined by matching each instance of a demonstrative pronoun in the English dialogues with its translation outcome in Italian. Such an analysis will show which patterns of translation are likely to shape Italian dubbed texts, where demonstrative deixis plays a minor role compared to the original English counterparts (see Table 3). Newly added pronouns will be discussed in a later section (see section 4.2).

Table 3

Demonstrative pronouns in the Pavia corpus of film dialogue[*]

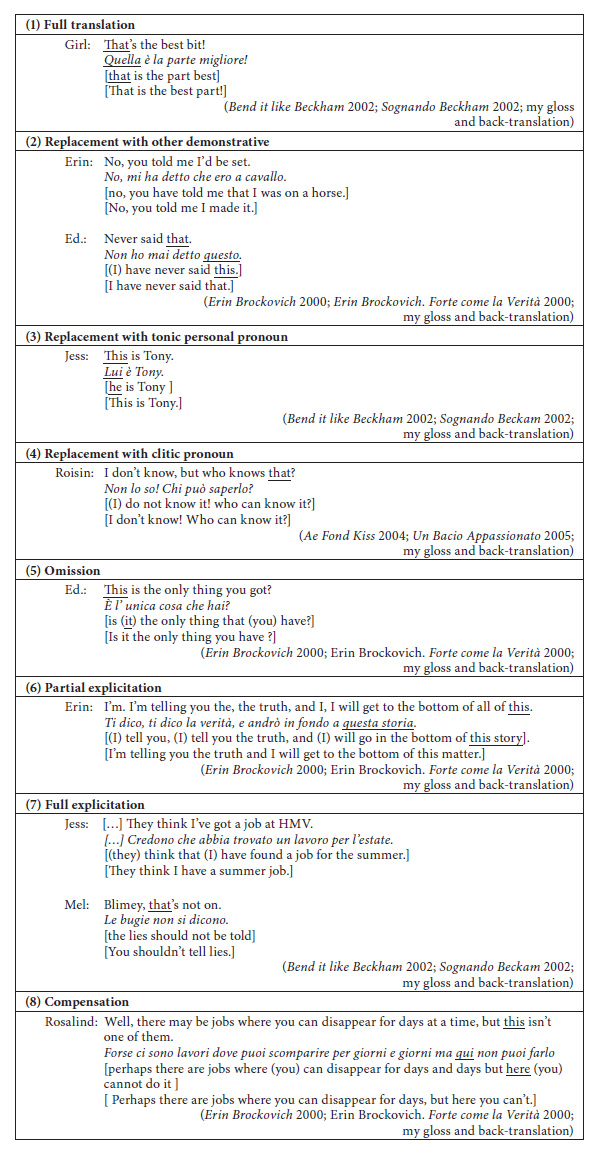

The operations[9] used in translating this/these and that/those into Italian film dialogue were initially identified as belonging to four main groups: retention, substitution, omission, and explicitation (Pavesi 2008b). These operations have been further subdivided for the present study as listed and exemplified in Table 4. Given the high number of occurrences taken into consideration and the search for general trends, these categories necessarily subsume wide-ranging interventions by the translators-dialogue writers and represent unavoidable simplifications of a variety of individual translation solutions.

With the exception of the rendering of English demonstrative pronouns by the formally equivalent ones in Italian, i.e. proximals with proximals and distals with distals (operation 1), all operations involve translation shifts.[10] Demonstrative pronouns in the original text can be replaced with a pronoun of the other series, i.e. a distal demonstrative with a proximal one, or vice versa (operation 2). They can be translated with a full tonic pronoun, either lui (he/him) or lei (she/her) (operation 3), or replaced by a weak, clitic pronoun performing a lower focussing function similar to the English it (operation 4). It sould be stressed that in most cases the clitic pronoun comes before and not after the verb. Omission or deletion of the demonstrative is another translation operation (5), through which the explicit verbal link to the external context or verbal discourse is weakened or removed. When omission occurs, the demonstrative disappears from the text and is not compensated for, nor is it replaced by other deictic or referential devices. Demonstrative pronouns may also be translated via explicitation, realised partially as the replacement of the demonstrative pronoun by a demonstrative determiner within a more explicit noun phrase (operation 6) or fully through the substitution of the demonstrative with non-deictic, full lexical items (operation 7). Finally, the loss of a demonstrative pronoun can be compensated for within the same utterance by means of other deictic or focussing structures such as the demonstrative adverbs qui (here), là/lì (there), così (so/like this/like that), and guarda (look) (operation 8).

Table 4

Translation operations for demonstrative pronouns in the Pavia corpus of film dialogue

4.1 Results of the source-based analysis

Using the taxonomy above, each instance of a demonstrative pronoun in the English section of the corpus has been manually annotated for translation operation. Table 5 reports the raw data and percentages concerning the translation operations for all the English demonstrative pronouns in the Pavia corpus of film dialogue.

Table 5

Translation operations for demonstrative pronouns in the Pavia corpus of film dialogue

1: Full translation; 2: Replacement by other demonstrative; 3: Replacement by tonic pronoun; 4: Replacement by clitic pronoun; 5: Omission; 6: Partial explicitation; 7: Full explicitation; 8: Compensation.

From the data presented, a series of tendencies can be observed. The most general and noticeable result is that only a small percentage – 12.8% – of English demonstratives are translated into formally equivalent pronouns in Italian. In particular, no more than 6% of the pronouns that and those in the original films have been rendered by the corresponding distal pronouns in Italian. This and these are translated to the corresponding proximal demonstratives relatively more frequently, i.e. 28% of the time. Quite often, a distal pronoun in English is translated into a proximal pronoun in Italian, as 13.1% of the pronouns that and those in English have been shifted to quest- in Italian. Conversely, less than 1% of the English proximal pronouns have been rendered as distal pronouns in translation. The trend is opposite to that observed in Mason and Şerban (2003), who report most shifts from proximal to distal demonstratives in translation from Rumanian into English. This suggests rather strongly that the systemic contrasts between the two languages involved and the translation direction have an important impact on the translation process (see Goethals 2007 and below).

Omission is the most common operation in the corpus of translations for dubbing, accounting for 41.5% of the renderings of all demonstratives, with distal pronouns being omitted more often than proximal ones (46.2% vs. 31.5%, respectively). In itself, the considerable frequency of this operation reveals a perceived lack of equivalence between demonstratives in the two languages. In particular, the trend is true for the pronoun that, which undergoes many more shifts than the pronoun this. An operation that also involves the loss of “demonstrativeness” is the replacement of demonstratives by clitics, whereby deixis is expressed more weakly through grammatical devices that cannot highlight the referent. Translation into clitics applies to 12.0% of the original demonstrative pronouns, with distal pronouns again being involved in more shifts than proximal ones.

Another 12.4% of all demonstratives are rendered through explicitation, with full explicitations being preferred over partial ones. Explicitation as well involves the loss of demonstrative pronouns during the translation process, supporting the tendency evidenced by other translation operations and confirming the difficulty in transferring source text demonstratives to the target texts. These transfer operations, however, are worth noticing for their implications within the specific audiovisual context. With explicitation, reliance for interpretation on the linguistic and extralinguistic context is lost or weakened, the immediate verbal text supplying at least part of the information that had to be extracted elsewhere in the source film.

Finally, with compensations – that is, the substitution of a demonstrative pronoun with another focussing device that realises a “joint focus of attention,” deixis is preserved, but expressed differently. The translated text maintains its verbal grip on the audience, but resorts to other means to emphasise entities in discourse, such as through the use of the presentative adverb ecco (here) (Serianni and Castelvecchi 1991: 509-511), frequent and natural in spoken Italian, where it often performs the function of pointing to a new referent or drawing attention to something previously said:

8

Casim: |

She was here having a drink, that’s what she’s doing here. Sta bevendo una cosa. Ecco che ci fa. [She’s drinking something. Here is what she’s doing.] |

Yet, compensation accounts for only 10.3% of all translations. Due to space limitations, the operations of explicitation and compensation will not be further discussed in this paper. It should be stressed that compensations are outnumbered by other translation operations, including explicitations, which bring about a loss or weakening of the focus of attention originally contained in the source texts.

4.2 A closer look at language contrast in dubbing

As the results of the analysis of the Pavia corpus of film dialogue indicate, there is a systematic reduction of demonstrative pronouns when moving from the English film dialogues to the Italian ones. On the one hand, the overall shifts bring about an alignment between dubbed and original film language in Italian; on the other, we hypothesise that such a considerable loss of demonstrative pronouns during the translation process may be triggered by the contrast between source and target languages, translation being a typical contact situation in which two languages are simultaneously processed by the translator (Mauranen 2004-2005; Becher, House et al. 2009). More specifically, systematic cross-linguistic differences may lead to avoidance, i.e. the restraint on the part of the translator to transfer source text features felt to be unnatural in the target language, as discussed in works on omission as a translation operation (e.g., Klaudi 2003: 377-387; Dimitriu 2004; Davies 2007).

The distribution of the operations according to the syntactic role of the demonstrative pronoun in the source text confirms that structural and pragmatic differences between English and Italian have an impact on translation outcomes. Table 6 reports the frequencies of all translation operations as applied to the different syntactic roles of subject, direct object and prepositional object for both this and that. In keeping with the optionality of the grammatical subject in Italian, demonstratives are deleted most frequently when in subject position, as 39.4% of the subjects this and 58.7% of the subjects that disappear in the Italian translations. Consequently, for both proximal and distal demonstratives, omission is by far the most frequent treatment of demonstrative pronouns used as subjects when transferring audiovisual dialogues from English into Italian. The very high proportion of demonstratives in subject position in English texts does in fact contribute to explaining why omissions are so widespread in the whole corpus.

Table 6

Translation strategies divided per grammatical role of the English singular pronouns

1: Full translation; 2: Replacement by other demonstrative; 3: Replacement with tonic pronoun; 4: Replacement with clitic pronoun; 5: Omission; 6: Partial explicitation; 7: Full explicitation; 8: Compensation.

It should be noted that omitting the subject demonstrative often avoids unnatural, marked usages or anglicised structures, in particular when that, and less often this, occurs as grammatical subject in idiomatic set phrases or conversational routines, such as that’s it, that’s right, that blows it, that’s great, that’s good (see Wu 2004: 103-104). Since these formulas often lack a formal equivalent in Italian, the translation disposes of the demonstrative but resorts to equally conventional or idiomatic expressions, which adds to the naturalness of the end product:

9

Peck to Basher: |

Booby traps aren’t Mr Tarr’s style. Isn’t that right, Basher? |

Non sarebbero nello stile del signor Tarr. Dico bene, Basher? |

[They wouldn’t be in Mr Tarr’s style. Am I talking right, Basher?] |

10

Nina Yorkin: |

Oh that’s okay. |

Non fa niente. |

[It’s nothing.] |

11

Ed: |

Ten per cent raise, and benefits. But that’s it! I’m drawing the line! Aumento del dieci per cento e assistenza! Ma è tutto! Ho chiuso i cancelli! [Ten per cent rise and benefits! But it’s all. I’ve closed the gates.] |

12

Billy: |

You don’t know what he’s like. Lei non lo conosce! [You don’t know him!] |

Mrs. Wilkinson: |

Well, that blows it. |

Beh, peccato! |

[Well, that’s a pity!] |

The notion of “idiomatic omission” is pertinent, here, to account for translational choices that occur when “it is more acceptable in the target language to omit a particular item rather than trying to use a translation equivalent ‘by hook or by crook’ to the detriment of idiomaticity and naturalness in the target language” (Ramón and Labrador 2008: 292; see also Rocha 2010). The simulation of orality and the high level of formulaicity in film language (Chaume Varela 2001; Kozloff 2000; Pavesi 2008a) may hence play a part in the reduction of demonstrative pronouns during the translation process, since translators-dialogue writers look for equally idiomatic expressions in the target language that do not necessarily include a demonstrative. Routines and their renderings therefore draw attention to the relevance of genre in the translation of demonstratives,[11] as suggested for deixis in general (Becher 2010).

Yet, the omission of subject demonstratives only partially involves idiomatic reformulations of conversational routines, in that it is of wider application. The following excerpts illustrate both endophoric and exophoric, non formulaic this and that being omitted in the target text.

13

Joe: |

This is the second training session in a row she’s missed. È la seconda volta che non si presenta all’allenamento. [(It) is the second time that she doesn’t come to the training.] |

14

William Yorkin to shop assistant: |

Oh, uh, great, you know, it doesn’t say here if this will work for the Mac or not. |

Oh, bene, senta. Qui non dice se funziona con un Mac o no. |

[Oh, well, listen. Here it doesn’t say whether (it) works with a Mac or not.] |

15

Prof Matthews: |

Jamal, either you happen to have the permission of William Forrester, or have, have you some other explanation? |

Jamal, i casi sono due, o tu hai il permesso di William Forrester, oppure hai, hai qualche altra spiegazione? |

[Jamal, there are two possibilities. Either you have the permission of William Forrester, or you have some other explanation?] |

Jamal: |

No. That’s my paper. No, è un lavoro mio. [No, (it)’s my work.] |

16

Josh to Danny: |

I will see your five hundred and I will raise you another five hundred of my own. |

Vedo i tuoi cinquecento e… rilancio… di altri cinquecento e come la vedi? |

[I see your five hundred and I raise another five hundred and how do you see it?] |

Rusty to Josh: |

That’s a very handsome bet Josh. […] |

È una gran bella puntata Josh. […] |

[It is a very handsome bet Josh.] |

Omission affects direct and prepositional objects as well: 19.6% of the pronouns this and 22.0% of the pronouns that are not translated if they are direct objects in the English texts; slightly higher percentages apply to the objects of prepositions, with 23.3% of the pronouns this and 26.1% of the pronouns that disappearing during the translation process. Frequently, the translated texts are syntactically rearranged so as to avoid the use of an object in an unnatural position in Italian (17). Elsewhere, the demonstrative is omitted by resorting to lexical reformulation (18), or is simply dropped without any syntactic reordering (19).

17

Lydia: |

Why are you pretending I’m Russell? You know I hate that. Perché fai finta che io sia Russell? Lo sai che non mi piace. [Why are you pretending I’m Russell? You know it doesn’t please me.] |

18

Dr. Spencer: |

[…] I’ve been talking to some of the other board members and to Crawford, and bottom line is we don’t want to pursue this anymore than you do anyhow. |

[…] Ne ho discusso col Consiglio e con Crawford e la verità è che non vogliamo andare avanti, come non lo vuoi tu. |

[I’ve discussed it with the Board and with Crawford and the truth is that we don’t want to move forward, like you don’t want to.] |

19

Linus: |

You’re Frank Catton, formerly of the Tropicana, the Desert Inn and the New York State Penitentiary system. Are you not? I take it from your silence that you are not gonna refute that. Lei è Frank Catton, precedentemente stava al tropicana, al Desert Inn e nel sistema penitenziario dello stato di New York. Non è vero? Deduco dal suo silenzio che non ha intenzione di controbattere. [You’re Frank Catton, formerly of the Tropicana, the Desert Inn and the penitentiary system of the New York State. Isn’t it true? I take it from your silence that you do not intend to refute.] |

It should be noted that object deletion occurs to a lesser extent than subject deletion, a trend that substantiates the claim that omission in translation from English into Italian is systematically related to the syntactic role of the demonstrative.

Yet, cross-linguistic contrast between English and Italian does not only result in omissions. Pronominal substitution is another translation operation that, due to its frequency, brings to light a perceived difference between source language and target language, as well as the avoidance of potentially anglicised renderings in Italian. To a great extent object demonstratives are translated into clitic pronouns, this operation accounting for the rendering of 30.4% of direct object this and 43.5% of direct object that. Translation into clitics reflects the role played by these weak pronouns in Italian, where they may perform the same endophoric and exophoric functions as demonstrative pronouns, although with a lower deictic force (see Berretta 1985; Gaudino-Fallegger 1992; Sabatini 1985). Once again, replacing demonstratives mainly results in natural solutions in Italian dubbing.

20

Jamal’s mother: |

Mr. Bradley, hem, there’s no way we could ever pay for this. Signor Bradley, noi, ehm, non avremo mai i mezzi per pagare la vostra retta. [Mr. Bradley, we, hem, we will never be able to pay your school costs] |

Mr. Bradley: |

We’re not asking you to. Jamal, when Dr. Simon mentioned that only the best go to Mailor, he neglected to mention that our commitment to excellence is extensively beyond the classroom. Ma non vi chiediamo di farlo. Jamal, quando il professor Simon ha detto che solo i migliori frequentano la Mailor, non ha sottolineato che il nostro impegno a distinguerci va ben oltre le aule scolastiche. [But we are not asking you to do it. Jamal, when professor Simon said that only the best go to Mailor, he did not emphasised that our commitment to excellence goes well beyond the classroom] |

Jamal: |

I figure that. Sì, lo avevo immaginato. [Yes, I had figured it.] |

Overall in the corpus, many are the cases in which the demonstrative pronoun dissolves into the Italian translation through a reformulation of the textual information, as shown in excerpt (21), where all of the three English demonstratives – exophoric and endophoric – are either deleted or substituted.

21

Jenny: |

No, those are the originals, and they’re yours to keep. That’s your right, under the 1975 Act. I’ve made copies upstairs. I’ll pop those in here, for you. No, non è necessario, puoi tenere gli originali, è un tuo diritto in base alla legge del settantacinque. Ne abbiamo una copia in archivio. Mettiamoli qua dentro, dà a me. [No, it’s not necessary. You can keep the originals. It’s your right, under the 1975 Act. We have a copy of them upstairs. Let’s put them in here. Give me.] |

4.3 Additions to the target text

To complete the picture, it should be pointed out that the systematic loss of demonstratives from the source texts to the target texts is only partially balanced out by the additions of equivalent deictic features during the translation process. More precisely, 407 demonstrative pronouns have been added to the Italian translations versus 1,051 English demonstrative pronouns that were omitted or replaced with weaker pronominal or lexical forms.[12] Hence, during the translation process, the loss of demonstratives is compensated less than half of the time these features fall out of the source texts. As reported in Table 7, many of these additions are grammaticalised demonstratives mostly functioning as nominal heads of relative clauses and indefinite relatives (e.g., quello che > “the one/ones that, what”: “Faquello che ti dice” > “You just do what he says” [Crash]). Given the mere grammatical function of these demonstratives, they hardly express a joint focus of attention and add very little to the deicticity of the dialogue (see Becher 2010; Dixon 2003: 68; section 1.2).

Table 7

New demonstratives in the translated component of the Pavia corpus of film dialogue

The remaining additions can be described as resulting from operations that to some extent represent inverted cases of the translation operations previously described (see sections 4 and 4.1). A total of 62 (or 18.4%) of the new additions to the Italian texts are made up of explicitations and full additions, corresponding to filled out elliptical structures, new turns in the Italian versions, repetitions or rephrasing which include a new demonstrative pronoun. These additions may be considered opposite cases of the omissions of English demonstratives – i.e., operation 5 –, but cannot make up for the extensive loss of pronouns through that operation. In excerpt (22) below, an elliptical clause in English becomes a fully-fledged clause containing an exophoric pronoun in Italian. In excerpt (23), the endophoric demonstrative questo is triggered by the rephrasing in the translated text and explicitly links the first and second part of turn.

22

Ria: |

Look, the car’s registered to a… Cindy Bradley. And that’s not Cindy. That is a… William Lewis. Found under the front seat. Hollywood Division. Beh, la macchina è intestata a una certa Cindy Bradley. E quello non è Cindy. Infatti è William Lewis. Questo era sotto il sedile. Distretto di Hollywood. [Well, the car’s registered to a… Cindy Bradley. And that’s not Cindy. In fact it is a… William Lewis. This was under the front seat. Hollywood Division.] |

23

Matthew Poncelet: |

God knows the truth about me. I’m going to a better place. I’m not worried about nothing. |

Dio conosce la verità su di me. Sto andando in un posto migliore e questo mi rende tranquillo. |

[God knows the truth about me. I’m going to a better place and this makes me calm.] |

Even fewer new demonstratives are instances of implicitation (10.8% of all new pronouns), the opposite strategy of operations 6 and 7. In these cases, an Italian demonstrative pronoun replaces a noun phrase with either a demonstrative determiner or a non-deictic full lexical expression. These pronouns as well increase deixis in the translated text, in that viewers are instructed to rely on the immediate verbal or non-verbal context to identify the identity in focus, as in (24). However, the new pronouns only in part compensate for the loss of demonstratives during the translation process, since they can hardly compare to the number of explicitations replacing the English demonstrative pronouns.

24

William: |

You have a stunt bottom? Hai una controfigura per quello? [Do you have a stunt for that?] |

Compensations account for another 10.6% of all new Italian pronouns. Here, the demonstrative carries the deictic meaning expressed by other structures in the source texts as in (25). Yet, the frequency of this operation represents only 24.9% of the same operation in the opposite direction, corroborating the quantitative discrepancy between the English dialogues and their Italian translations.

25

Anna: |

Okay. And here is your desk. Ok. E questa è la tua scrivania. [Okay. And this is your desk.] |

Despite their restricted frequency, the replacements of source third person pronouns with target demonstrative pronouns interestingly highlight some specificities of the Italian language. These strategies represent opposite cases of operations 3 and 4, although the system-related motivations for substitution clearly differ. The third person tonic pronouns for non-human referents – esso, essa, essi, esse – do not occur in everyday spoken Italian, and are simply left unexpressed or replaced by demonstrative pronouns (Cordin and Calabrese 2001: 549-550):

26

Bill Owens: |

Sy, there’s a thousand other places you could do your photos. There’s no reason to come all the |

way down here other than to fuck with me. |

Ci sono mille altri posti dove puoi portare le tue foto, tu vieni qui solo per un motivo, rompermi le scatole. |

[There are a thousand other places where you could bring your photos, you come here just for one reason, to break my balls.] |

Mr Parrish: |

There’s a very good reason. I calibrated that machine personally. It’s the best mini-lab in the state. |

Oh, ho un ottimo motivo. Ho calibrato io la macchina personalmente. Questo è il miglior laboratorio dello stato. |

[Oh, I have a very good reason. I calibrated the machine personally. This is the best lab in the state.] |

Moreover, differently from English[13] Italian readily allows the use of demonstrative pronouns for human reference, especially to convey a negative evaluation of the person identified (Calabrese 2001: 643). This use increases the idiomaticity of the Italian dialogues by exploiting a typical feature of spontaneous informal Italian[14] like in the following excerpt where an angry woman is on the phone with a friend:

27

Jean: |

[…] I’m not snapping at you! I am angry. Yes! At them! Yes! At-at-at them, the police, at Rick, at Maria, at the dry cleaners who destroyed another blouse today, at the gardener who-who-who keeps overwatering the lawn, I… Non ti sto facendo un rimprovero, è che sono incazzata! Sì, con quelli! Sì, con-con loro, con la polizia, con Rick, con Maria, con… la tintoria che m’ha distrutto un’altra camicetta oggi, col giardiniere che-che-che mi innaffia troppo il prato, io… [I’m not reproaching you, it’s that I’m pissed off! Yes, at them! Yes at-at them, at the police, at Rick, at Maria, at the dry-cleaners who destroyed another of my blouses today, at the gardener who-who-who overwaters the lawn, I…] |

Finally, as for the separate contributions of proximal and distal pronouns, it should be noticed that the latter are added almost three times as frequently as the former, a fact that confirms the contrast between English that-those and Italian quell-. It should be further underlined that, although there are many more additions of Italian distal pronouns, these to a large extent perform a low scope grammatical function, thus restricting the role they play in the deicticity and connectivity of the Italian dialogues.

28

Gerry: |

Helen, I swear. I’ll do anything you want, Helen. Helen, te lo giuro. Fa-farò tutto quello che vuoi, Helen. [Helen I swear to you. I’ll do all you want, Helen.] |

All in all, new additions of demonstratives contribute to a limited extent to the occurrence of these features in the Italian versions, thus confirming the patterns of textual restructuring induced by the translation process.

4.4 Exophoric and endophoric demonstratives in the original and dubbed versions

The special status of demonstratives in the multimodal context in which film dialogue is embedded brings up a further and crucial dimension involved in translation for dubbing: the exophoric and endophoric functions of the demonstrative pronouns. As pointed out earlier, in both spoken English and spoken Italian demonstratives more frequently perform an endophoric function, thus drawing the listener’s attention to the content of the verbal text. By contrast, further analyses of the original English dialogues have revealed that, if demonstratives repeatedly foster verbal cohesion and turn-by-turn interactivity, they almost as often pick up entities in the sensorial and experiential context made accessible via the multimodal setting and film narration (see Table 8). In other words, English demonstratives, to a similar extent, perform an endophoric and exophoric function in films. This means that, in comparison with demonstrative reference in spontaneous spoken English, in this multimodal context more attention is paid to the concrete and abstract entities represented on screen. The relatively greater emphasis on exophora in English film dialogue needs further study as film language should be viewed as a fully-fledged genre characterized by its own discoursal and pragmatic choices (see Piazza, Bednarek et al. 2011).

Table 8

Exophoric and endophoric demonstratives in the original Anglophone component of the Pavia corpus of film dialogue

As for the translation process, it is difficult to identify one pragmatic function that is strikingly favoured when transferring the English pronouns into Italian (see Table 9). By looking at full translations and omissions, an advantage can be assigned to exophora over endophora as relatively more pronouns are retained and fewer omitted when they single out items of the situational context, as opposed to discoursal units. However, this advantage is slightly reduced if full translations and replacements with other demonstratives are conflated in one category, so that what counts is whether a demonstrative pronoun in the source text is translated with another demonstrative pronoun – no matter if proximal or distal – in the target text.

By contrast, cross-linguistic difference in terms of the distinction between proximal and distal demonstratives very clearly appears to affect the translation patterns. Proximal pronouns, in fact, are carried over from the source into the target text more often than the distal ones, independently of the pragmatic function they serve. Conversely, the latter are more frequently and systematically reduced in both functions. It was suggested earlier that the observed greater number of shifts involving English distal pronouns may reflect the different preferences of the two languages in the choice of the pronoun to express discourse deixis, as shown in (29). This hypothesis is once again supported by the considerable number of substitutions and omissions pertaining specifically to the endophoric that. The distal pronoun performing such function is translated with a proximal one 113 times and omitted 361 times, i.e. more than 60% of the time it occurs in the source texts.

29

Sister Helen: |

My name was in the paper? |

Davvero hanno letto il mio nome? |

[Have they really read my name?] |

Helen’s mom: |

That has nothing to do with that. |

Questo non è importante. |

[This is not important.] |

Table 9

A selection of translation operations for exophoric and endophoric demonstrative pronouns

Note that the figures in the right column are not the sums of the figures in the preceding columns (which present only a subset of operations).

Interesting aspects of pragmatic reorganisation come to the fore when the attention is moved to the final product of translation. In comparison with the English dialogues, where demonstrative exophora and endophora, on the whole, balance each other out, at the end of the translation process the Italian dubbed dialogues reveal a shift towards endophora (see Table 10). Most endophoric demonstratives are actually added to the target texts rather than being transferred from the source texts, and many of these – 182 out of the 266 quell- pronouns – are involved in grammaticalised expressions (see section 4.3 above). Although it has been suggested that such grammaticalised structures play a restricted role in the cohesion and inter-turn connectivity of the dubbed dialogues, the overall frequencies of endophores do suggest a greater emphasis on textual rather than contextual reference through demonstratives in dubbing.

Table 10

Exophoric and endophoric demonstratives in the translated component of the Pavia corpus of film dialogue

These results on the pragmatic functions of demonstratives thus show that in the original and translated dialogues alike, these features serve both discourse and contextual deixis in their highlighting of dialogue as well as of the extra-linguistic framework. At the same time, if English pronouns draw viewers’ attention to items of the represented situational context more frequently than in spoken language, dubbed language appears to come closer to spontaneous spoken Italian in its relative preference for endophora over exophora (see Gaudino-Fallegger 1992 and section 1.1 above). Finally, the interaction between the pragmatic functions and the translation outcomes offers supplementary support to the hypothesis that cross-linguistic contrast plays a major role in the transfer of demonstrative deixis, and hence in the shaping of the audiovisual translated text.

5. Translation behaviour and the effects of translation operations

In the present investigation, Italian dubbed language has been found to exhibit fewer demonstrative pronouns than average spoken Italian, and to ultimately gravitate towards the language spoken in original Italian films. The quantitative analysis of translation operations has further shown that demonstratives are systematically reduced when the audiovisual text is transferred from English into Italian, with additions to the target texts of equivalent deictic devices only partially compensating for the losses occurred during the translation process. In particular, the considerable number of omissions and substitutions observed in the Pavia corpus of film dialogue points to the relevant role of cross-linguistic contrast, since such translation shifts mainly take place within areas in which English and Italian differ both syntactically in the expression of the subject and the position of the object, and pragmatically in the choice of preferred reference forms. As a result, it may be suggested that the abidance by the generic norms of audiovisual dialogue in Italian and the cross-linguistic contrast between the source and the target language operate together in defining the patterning of demonstratives in Italian dubbing. Further analysis of the demonstrative pronouns’ pragmatic functions has interestingly shown that during the translation process, a realignment occurs whereby the verbal focus of attention onto physical and abstract entities in the original dialogues undergoes a shift towards relatively greater emphasis on discourse in the translated dialogues, thus bringing dubbed language closer to spoken Italian.

If the observed translation operations produce target text utterances that sound natural and reflect the preferences of the target language, yet, in most cases the operations of omission, substitution and explicitation lead to a cumulative reduction of verbal deixis. Moreover, these systematic shifts are likely to affect dubbed texts through chains of local rephrasing which dispose of the demonstratives contained in the original utterances, simultaneously bringing about an organised restructuring at a higher textual level (Leuven-Zwart 1989-1990; on deixis, see Bosseaux 2007). As for omission, the following excerpt (30) illustrates how the translation operation may trigger a noteworthy rephrasing of the text. The pronoun this in the source text performs a discourse deictic function, projecting the text forward and contributing to the salience of the word in focus: date. By contrast, the Italian text integrates the information into a more tightly structured utterance, which at the same time is devoid of the deictic and emphatic element present in the original.

30

Matthew (voice): |

I know I’m on death row, but there’s guy been here years and years. I didn’t know this was coming! They set a date! |

Lo so che sto nel braccio della morte, ma c’è gente che ci ha fatto la muffa qui! Non sapevo che avessero già fissato la data! |

[I know that I am on death row, but there are people that have moulded here! I didn’t know that they had already set the date!] |

In the following dialogue line as well (31), the syntactic-pragmatic reordering corresponds to a loss of the demonstrative, while the explicit reference to the contextual situation made in English disappears, along with the emphasis on shared knowledge and experience as represented on screen.

31

Mr Walsh: |

There, does that satisfy you, mister Zerga? |

Ora è soddisfatto, signor Zerga? |

[Now are you satisfied, Mr Zerga?] |

The substitution of postverbal demonstrative pronouns with preverbal clitics analogously contributes to a dubbed language where emphasis and contrast are grammatically reduced, and where cohesion relies more on weak, unemphatic forms of reference. In (32) the clitic lo (it) translates the discourse deictic that used in the English text. Both pronouns point to and summarise the whole series of commands issued by Casim, creating intra-turn cohesion and amplifying the challenging force of the final question. However, the climactic that, in Casim’s reply, is a stronger form that is phonetically stressed and hence highlighted, unlike lo, which as a clitic pronoun can never be.

32

Casim: |

Meet her, then! Her name’s Roisin! Meet her! Talk to her! Get to know her! Can you do that? La dovete incontrare! Si chiama Roisin! Parlateci! Conoscetela! Lo farete? [You must meet her! Her name is Roisin! Speak to her! Get to know her! Will you do it?] |

The use of fewer demonstrative pronouns reduces the expression of joint focus of attention, but at the same time, makes the dialogic exchanges more “inexplicit,” as the verbal text must be filled in through access to the visual and narrative setting. In the multimodal context of film, this may mean greater reliance, on the viewers’ part, on the visual, acoustic and generally perceptible context alone for a full interpretation. In the following excerpt (33), the Italian viewer can reintegrate the omitted subject only through the images appearing on screen, by drawing on the characters’ oriented posture and gaze, but without any further verbal direction:

33

Monica: |

(Maurice looks at Monica’s shirt) What is it? Che c’è? [What’s the matter?] |

Maurice: |

Is that a suit? È un completo? [Is (it) a suit?] |

Monica: |

It came as a combination. Ah, è fatto per essere abbinato. [Ah, it is made to be matched.] |

“Inexplicitness” has been put forward as an essential feature of natural conversation, and defined as the “product of the speaker combining language and context to convey her or his meaning in an inexplicit form in the expectation that the hearer can assign an unambiguous meaning to it [emphasis added]” (Warren 2006: 203). With fewer demonstratives, Italian translations appear to resort to greater inexplicitness, which indexes the intrinsic connection between the speakers’ utterances and what surrounds them. This is different from the English dialogues, where verbal emphasis is drawn to contextual entities coming into focus and where the interactivity of the unfolding discourse is clearly highlighted.

The data available therefore show how the translation of demonstrative pronouns from English into Italian may extensively transform audiovisual dialogue. Due to the general structuring capability of these features, two different overall configurations emerge in the source and the target texts at the end of the analysis. On the one hand, English audiovisual dialogues take great advantage of demonstrative deixis to verbally invite interactants and audiences to focus their attention onto a specific segment of unfolding text or represented situation. On the other hand, Italian audiovisual dialogues exploit weaker forms of reference to a greater extent and may consequently rely more on the sharedness of the whole context. That is, the Italian dialogues appear to link to portions of the multimodal text taking advantage of the film’s iconicity and shared universe of representation. Iconicity is considered an intrinsic quality of films, which – compared to other forms of narration – primarily show rather than tell, while we, as audiences, “interpret [them] based on our experience in interpreting the visual world around us” (Kruger 2010: 235).

Interestingly, it has been suggested that when a strong interrelation between context and co-text is posited by speakers, like in very colloquial and informal interactions, Italian calls for fewer demonstratives (Gaudino-Fallegger 1992: 132-151), differently from English, where an increase in shared knowledge leads to a greater use of these deictic devices (see McCarthy 1998: 26-48). This hypothesis distinguishes among different genres of spoken language characterised by varying degrees of familiarity among interlocutors, informality of situation, and emphasis on novel content. In other words, when interlocutors are familiar or intimate with each other and talk freely within a shared universe of discourse, less need is felt in Italian to single out referents by means of strong and marked deictic forms. In English, conversely, where demonstrative pronouns are less marked and more grammaticalised, they typically express inexplicitness and are used to avoid more elaborated noun phrases, while at the same time verbally zooming in on portions of the surrounding environment. It may thus be argued that Italian and English dialogues in multimodal film contexts partially reflect different discourse assumptions, which results in different organisations of the deictic resources in the fictive representation of close interactivity.

6. Conclusions

Demonstratives play a central role in spoken language, and in the present study, they have been interpreted as the major, prototypical means that verbally convey a joint focus of attention in both English and Italian. The two languages, however, meaningfully differ in the syntactic and pragmatic uses of these deictic structures. The results of the target-oriented and source-oriented explorations of a small parallel corpus of original and dubbed film dialogues, the Pavia corpus of film dialogue, have converged in identifying relatively few demonstratives in Italian dubbed from English. The more limited occurrence of these features in dubbed Italian distances it from available corpus data of spoken language, although placing it closer to the language of non-translated Italian films. From a complementary perspective, deixis through demonstratives has been revealed to undergo a considerable transformation from the source texts to the target texts, as indicated by the overwhelming number of shifts from the original to the dubbed dialogues. In particular, omissions and substitutions have been shown to work together towards a reduction of demonstratives when adapting English films for an Italian audience. It has been argued, in fact, that these numerous and systematic shifts involving demonstrative pronouns may be triggered by the syntactic and pragmatic contrasts between English and Italian, hence substantiating deixis in translation as an area susceptible to the cross-linguistic variation between source language and target language.

During the translation and adaptation process of English films into Italian, idiomatic language is produced that safeguards the simultaneous highlighting of the dialogic and multimodal-narrative dimensions of the original: i.e., English dialogues and their translations link to both the ongoing discourse and the setting portrayed on screen. Dubbed Italian, however, verbally draws slightly less attention to the situation represented on screen and more generally appears to be less deictically emphasised than both the target community’s average spoken language and the original English dialogues. As a consequence of the use of fewer demonstratives and their replacement with weaker reference forms, the language of dubbing appears to rely more on the interactants’ mutual understanding and the iconicity of the multimodal product, hence presupposing greater accessibility to the shared situation by the diegetic and extradiegetic participants. By contrast, the original English dialogue appears to offer characters and viewers alike more explicit directions to specific aspects of the unfolding dialogue and represented context of situation.

In conclusion, this study shows the complex interaction between naturalness and language contact in audiovisual translation, suggesting that combining target-oriented and source-oriented perspectives in corpus-based translation studies may contribute to a deeper understanding of the translation phenomena. Finally, Italian film dubbing has been confirmed in its domesticating dimension, whereby the systematic restructuring induced by cross-linguistic contrast brings the translated texts more in line with the target language norms and closer to non-translated texts belonging to the same genre within the repertoire of the target community.

Parties annexes

Appendix

The Pavia corpus of film dialogue

Acknowledgements

The research for this article has been carried out within the international project English and Italian audiovisual language: translation and language learning, generously funded by the Fondazione Alma Mater Ticinensis, University of Pavia. I wish to thank the creators and developers of Forlixt 1: Christine Heiss, Marcello Soffritti and Cristina Valentini for kindly granting me permission to access the corpus, and two anonymous referees for very helpful comments and constructive criticisms on earlier versions of this paper.

Notes

-

[1]

Following Diessel (1999: 100-105) and Himmelmann (1996: 224-229), discourse deictic demonstratives are here taken to refer to what Lyons identifies as “impure textual deixis,” i.e. “the relationship which holds between a referring expression and a variety of third-order entities, such as facts, propositions and utterance-acts” (Lyons 1977: 668). The author contrasts impure textual deixis with “pure textual deixis,” whereby (demonstrative) pronouns may be used to refer to – but are not co-referential with – language units in the surrounding co-text, such as forms, lexemes and text-sentences (Lyons 1977: 667-668). Lyons’s pure textual deixis has been called discourse deixis by some authors (e.g., Levinson 1983: 85-87; 2004: 107-108), although the distinction between the two types of textual deixis is not always clear-cut (see also Dixon 2003: 63-64; Fillmore 1997: 103-106). In view of this and on the ground of the very few instances of pure textual deixis in the corpus, no distinction between the two types of textual deixis will be made in this study.

-

[2]

According to Himmelman (1996: 225), discourse deixis may be hypothesised as the most frequent function for demonstrative pronouns cross-linguistically, unless special forms are available in the language to perform this specific function.

-

[3]

Whereas English does not mark gender on demonstratives, Italian generates a set of demonstrative forms whose morphology conflates number and gender.

-

[4]

The issue is quite controversial and not all linguists agree. In particular, drawing on data from questionnaires and translations of the book Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (Rowling 1998), Da Milano (2005; 2007) posits that in Italian as well distal demonstratives are unmarked. The data however are either elicited or mediated and the discussion pertains only to exophora. Rowling J.K. (1998): Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. London: Bloomsbury. Rowling J.K. (1999): Harry Potter e la Camera dei Segreti. Translated by Marina Astrologo. Florence: Adriano Salani Editore.

-

[5]

It should be noticed that since film translation in the English-speaking countries is virtually restricted to subtitling, the corpus could not include Italian films dubbed into English, and consequently was bound to be unidirectional. This limitation must be kept in mind in the evaluation of the results.

-

[6]

AntConc 3.2.1w is a freeware concordance programme implemented by Laurence Anthony. Last accessed on 18 July 2011, <http://www.antlab.sci.waseda.ac.jp/index.html>.

-

[7]

A previous study has shown that at least the major functions performed by demonstratives are reproduced in dubbed Italian (Pavesi 2008b).

-

[8]

The references for the films can be found in the Appendix section.

-

[9]

The term is here to be interpreted in its broadest and most neutral sense as identifying “all the operations translators perform, from automatic substitutions to conscious redistribution of explicit and inexplicit information” (Klaudi 2003: 153).

-

[10]

Many of these shifts may be argued to be obligatory and thus uninteresting when discussing strategic behaviour. Yet, as pronoun retention does not yield ungrammatical sentences (see Klaudi 2003: 380-381), it is difficult to decide on pragmatic grounds alone whether a shift is obligatory or optional. At the same time, so-called “obligatory shifts” too are indicative of translation norms that ultimately shape the translation outcome. For these reasons, the global frequency of operations rather than a strict distinction between obligatory and optional shifts has been recorded (see Mason and Şerban 2003 for a different procedure).

-

[11]

That omission and substitution of demonstratives is bound to genre is also suggested by the only contrastive study available so far that includes translations from English into Italian. As reported by Da Milano (2005: 215-219 and 233-237), the Italian translation of Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets contains many more full renderings of the demonstrative pronouns than those reported here, with fewer omissions and substitutions, hence pointing to generic variation within translations for the same language pair. The high number of demonstrative pronouns contained in the English film dialogues as opposed to narrative may also contribute to their more frequent omission in the Italian translations (see also Rocha 2010 on the translation of written fictive dialogues from English into Portuguese).

-

[12]

As reported in Table 5, the translation of the English demonstrative pronouns into Italian leads to 697 omissions, 202 substitutions with weaker pronominal forms and 152 full explicitations.

-

[13]

In English, the use of demonstrative pronouns for human reference is in fact restricted to copula subjects in identity clauses – e.g., “I’m Tom Robinson, and this is my wife Mandy” (Erin Brockovich 2000). In all other contexts, the demonstrative must be a determiner followed by a noun – such as guy, woman, or person (Dixon 2003: 66; Halliday and Hasan 1976: 62-63; Himmelmann 1996: 214, 217).

-

[14]

The lack of empathy and disrespectful connotations associated with the use of demonstrative pronouns to refer to human beings are frequently exploited with other translation operations as well. By means of implicitation, for example, translators may substitute a noun phrase made up of a demonstrative determiner plus a full noun by a simple demonstrative pronoun (e.g., that man > quello).

Bibliography

- Alfieri, Gabriella, Motta, Daria and Rapisarda, Maria (2008): La fiction. In: Gabriella Alfieri and Ilaria Bonomi, eds. Gli italiani del piccolo schermo. Lingua e stili comunicativi nei generi televisivi. Firenze: Cesati, 235-339.

- Baker, Mona (1996): Corpus-based translation studies: The challenges that lie ahead. In: Harold Somers, ed. Terminology, LSP and translation. Studies in language engineering in honour of Juan C. Sager. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 175-186.

- Becher, Viktor (2010): Differences in the use of deictic expressions in English and German texts. Linguistics. 48(6):1309-1342.

- Becher, Viktor, House, Juliane and Kranich, Svenja (2009): Convergence and divergence of communicative norms through language contact in translation. In: Kurt Braunmüller and Juliane House, eds. Convergence and divergence in language contact situations. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 125-151.

- Berretta, Monica (1985): I pronomi clitici nell’italiano parlato. In: Günter Holtus and Edgar Radke, eds. Gesprochenes Italienisch in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Tübingen: Narr, 185-224.

- Biber, Douglas, Johansson, Stig, Leech, Geoffrey, et al. (1999): Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. London: Longman.

- Bosseaux, Charlotte (2007): How Does It Feel? Point of View in Translation. The Case of Virginia Woolf into French. Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi.

- Botley, Simon and McEnery, Tony (2001): Demonstratives in English. A corpus-based study. Journal of English Linguistics. 29(1):7-33.

- Bubel, Claudia M. (2008): Film audiences as overhearers. Journal of Pragmatics. 40:55-71.

- Calabrese, Andrea (2001): I dimostrativi: pronomi e aggettivi. In: Lorenzo Renzi, Giampaolo Salvi and Anna Cardinaletti, eds. Grande grammatica italiana di consultazione. I. La frase. I sintagmi nominale e preposizionale. Bologna: Il Mulino, 631-645.

- Cardinaletti, Anna (2009): Si impersonale e dimostrativi: due casi di influenza dei dialetti sull’italiano? In: Anna Cardinaletti and Nicola Munaro, eds. Italiano, italiani regionali e dialetti. Milano: Franco Angeli, 29-54.

- Carter, Ronald and McCarthy, Michael (2006): Cambridge grammar of English. A comprehensive guide. Spoken and written English. Grammar and usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ChaumeVarela, Frederic (2001): La pretendida oralidad de los textos audiovisuales y sus implicaciones en traducción. In: Frederic ChaumeVarela and Rosa Agost, eds. La traducción en los medios audiovisuales. Castellón: Universitat Jaume I, 77-88.

- Cordin, Patrizia and Calabrese, Andrea (2001): I pronomi personali. In: Lorenzo Renzi, Giampaolo Salvi and Anna Cardinaletti, eds. Grande grammatica italiana di consultazione. I. La frase. I sintagmi nominale e preposizionale. Bologna: Il Mulino, 549-606.

- Da Milano, Federica (2005): La deissi spaziale nelle lingue d’Europa. Milano: Franco Angeli.

- Da Milano, Federica (2007): Demonstratives in parallel texts: a case study. Sprachtypologie und Universalienforschung. 60(2):135-147.

- Davies, Eirlys E. (2007): Leaving it out. On some justifications for the use of omission in translation. Babel. 53(1):56-77.

- De Mauro, Tullio, Mancini, Federico, Vedovelli, Massimo, et al. (1993): Lessico di frequenza dell’italiano parlato. Milano: Etaslibri.

- Diessel, Holger (1999): Demonstratives. Forms, Function, and Grammaticalization. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Diessel, Holger (2006): Demonstratives, joint attention, and the emergence of grammar. Cognitive Linguistics. 17:463-489.

- Dimitriu, Rodica (2004): Omission in translation. Perspectives: Studies in Translatology. 12(3):163-175.

- Dixon, Robert M.W. (2003): Demonstratives: A cross-linguistic typology. Studies in Language. 27(1):61-122.

- Fillmore, Charles (1997): Lectures on deixis. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

- Freddi, Maria and Pavesi, Maria (2009): The Pavia Corpus of Film Dialogue: Methodology and research rationale. In: Maria Freddi and Maria Pavesi, eds. Analysing audiovisual dialogue. Linguistic and translational insights. Bologna: Clueb, 95-100.

- Gaudino-Fallegger, Livia (1992): I dimostrativi nell’italiano parlato. Wilhelmsfeld: Gottfried Egert Verlag.