Résumés

Abstract

The purpose of this article is to explore ways to provide effective as well as practical teaching tools that can be utilized in translation courses for undergraduate students. The present study specifically focuses on the effect of having access to background information of the translation. Two groups are compared for this aim. One group was asked to conduct background research on the translation topic prior to engaging in the translation while the other group only had access to dictionaries to carry out the identical task. Students were asked to complete translations from Korean into English. Outputs of the two groups were compared to assess the impact of background information. The quantity and quality of background information were also analyzed to examine their influence on the quality of translation.

Keywords/Mots-clés:

- background information,

- undergraduate,

- translation education,

- quantity,

- quality

Résumé

Cet article a pour but d’explorer la façon de fournir aux étudiants, inscrits aux programmes universitaires de traduction, des outils d’apprentissage qui sont à la fois efficaces et pratiques. En comparant les résultats de deux groupes, cette étude visait à établir si l’accès des traducteurs aux données de fond d’un texte pourrait influencer la qualité de la traduction. Avant d’entamer la traduction en anglais d’un texte coréen, un groupe devait premièrement obtenir les données de fond tandis que l’autre ne pouvait se fier que sur des dictionnaires pour traduire les mêmes documents. Le résultat du travail des deux groupes a été comparé afin d’analyser l’effet de données supplémentaires. La qualité et la quantité d’information obtenue ont aussi été analysées afin de mesurer leur influence sur la qualité de la traduction.

초록

본 연구는 학부생들을 대상으로 실시하는 번역 교육의 효율성을 제고할 수 있는 방법을 살펴보았다. 특히, 번역 수행에 있어서 주제와 관련된 배경 지식의 중요성을 두 집단에 대한 비교 분석을 통해 알아보았다. 한 집단에게는 번역을 수행하기 전에 주제와 관련된 자료를 수집하고 분석하는 등 사전 준비를 하도록 하였으며 다른 집단은 사전만을 사용하여 번역을 하도록 하였다. 학생들의 번역을 평가한 후 통계적 분석을 통해 관련 자료 준비의 중요성을 입증하였으며 특히 관련자료의 양적, 질적인 차이가 번역의 질에 어떤 영향을 미치는지에 대한 분석 결과도 도출하였다.

Corps de l’article

I. Introduction

While background information research for the topic of the document to be translated is an indispensable step in the translation process, empirical research on the influence of background information on the quality of translation remains scarce. This paper will concentrate on an important, but oftentimes overlooked aspect of translation which has practical pedagogical value in the classroom: the importance of background information and the influence of information quality and quantity on translation performance.

II. Background

2.1. Translation Theory vs. Classroom Reality

What does it take to be a good translator? According to Gerding-Salas (2000) students should hold (1) sound linguistic training in the two languages, (2) knowledge covering a wide cultural spectrum, (3) high reading comprehension competence and permanent interest in reading, (4) adequate use of translation procedures and strategies, (5) adequate management of documentation sources, (6) improvement capacity and constant interest in learning, (7) initiative, creativity, honesty and perseverance, (8) accuracy, truthfulness, patience, and dedication, (9) capacity for analysis and self-criticism, (10) ability to maintain constructive interpersonal relationships, (11) capacity to develop teamwork, (12) efficient data processing training at user’s level, and (13) acquaintance with translation software for MT(Machine Translation). While the ideal student will possess all of the desirable traits, the real world often displays a quite different picture, especially at the undergraduate level.

Teaching undergraduate students how to translate into a second language is a challenging task. More often than not, students are equipped with neither the proper level of linguistic ability nor the appropriate amount of general background knowledge to carry out translation tasks in an efficient manner. Nonetheless, the trend in English education calls for a more pragmatic approach in training students to achieve a higher level of English proficiency, and as a result courses related to the actual use of English after graduation, such as translation courses, are gaining popularity among not only the school administration but also students (Kim 2004).

While theoretical perspectives on the process of translation provide valuable insight into a complicated procedure, translation theory sometimes seems unhelpful, and even irrelevant, to trainee and practising translators, despite a shift in recent years away from a purely theoretical approach and towards integration of practice (Fraser 1996).

2.2. Translators and Technology

When carrying out translation tasks, students must have the necessary resources to deal with the material such as dictionaries, glossaries, and any other resources. Such resources can include websites devoted to translation or terminology, online discussion groups concerning translation, friends or colleagues who work in the profession, and magazines and journals (James 2002). During the past two decades Korea has witnessed a technological revolution that has also had a significant impact on how translators work. A case in point is the personal computer, which has become an irreplaceable tool for translators.

The translation process demands knowledge and skills that range from adequately researching the social and cultural context of the source text, to making the best possible use of dictionaries, general reference books and the Internet. A translator is required to obtain a detailed understanding of the content of each sentence. Field-specific knowledge plays a critical role in successfully recognizing and understanding the concepts and the linguistic tools that translators use to convey information, to introduce a particular concept, or to argue a certain position. With sufficient background knowledge, one may build upon an accurate analysis of a sentence to establish the main points of the sentence. It is during this process that references such as dictionaries, glossaries, encyclopedias, and websites prove their worth. In particular, the translator must reexamine the source text, consult additional references, or (preferably) both when the apparent meaning (based on textual analysis) of the source text conflicts either with the translator's field-specific knowledge or with information gathered from reliable references (James 2002). This problem is a daunting one for many students. Intermediate-level students frequently indicate in footnotes that they know their translations contain inconsistencies but they cannot identify the source of their misunderstanding (James 2002). Since developing and maintaining familiarity with common patterns of expression in the target language by regularly reading or scanning target language publications either in paper or electronic form are important, students should be provided with instruction specifically dealing with background information pertinent to the translation topic at hand.

III. Experiment

3.1 Research Questions

The purpose of this study is to examine whether availability of background information of the translation topic has an influence on translation quality. Specifically, the following research questions will be looked into:

Is background information associated with translation quality?

Which attribute of background information (quality, quantity, or both) affects translation quality?

3.2 Subjects

Participants were 32 undergraduate students enrolled in a Korean/English translation course at a university located in Korea. The students were divided in half into two groups – one group was assigned a translation task without any background information and the other was allowed to collect background information to be used in the translation. Table 1 shows the number of participants in each group.

Table 1

Number of Participants in Each Group

3.3 Experimental Procedure

Because the groups were naturally occurring and not randomized, they needed to be pre-tested for differences in oral proficiency. A pretest was designed to measure the students’ initial level of reading proficiency. For the pretest, a reading section of the TOEIC test was administered.

3.3.1 Pretest: Reading Proficiency Assessment and Survey

A pretest was administered to measure the students’ entry level of reading proficiency. The test which is part of a practice TOEIC reading test consisted of 100 questions testing the ability to understand written English.

3.3.2 Experimental Treatment

Students were given a task to be translated from Korean to English (See Appendix A for the original text). Students were divided into two groups. Group 1 was allowed to consult the dictionary while carrying out the translation task. Group 2 was provided with the original text in advance and was allowed to bring in background information on the topic to be translated.

3.3.3 Translation Quality Assessment

For the first phase of the study, translations from both groups were graded by three native speakers teaching English courses at the university level. The translations were mixed in random order and judges were not provided with any information regarding the experiment treatment (See Appendix B for Translation Assessment Grid).

3.3.4 Quality and Quantity Assessment of Background Information

For the second phase, judges were asked to assess the quality of the background information collected by students in Group 2. The background information was also mixed in random order and judges were unable to associate certain background information with certain translation tasks. The judges ranked the quality of the background information on a scale from 1 (little association with the topic) to 5 (perfect match with the topic). Table 2 presents the criteria that were used to assess the quality of background information. Examples of the background information collected by the students are shown in Appendix C.

The quantity of the background information was represented by the number of words in the articles collected by the students to be used as references for their translation.

Table 2

Background Information Quality Assessment Criteria

3.4 Data Analysis

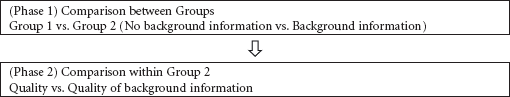

Table 3 summarizes the experimental procedure of the study.

Table 3

Experiment and Analysis Procedure of the Study

For an analysis of the pretest and the translation quality (Phase 1), analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used. Pretest measures of students’ oral proficiency were used as a covariate, and the translation grade as a dependent variable. The two groups were the fixed factors.

For an analysis of the background information and its effect on translation quality (Phase 2), multiple regression was used. Background information quantity, quality, and TOEIC reading test score were independent variables and translation grade was the dependent variable.

IV. Result and Discussion

4.1 Effects of Availability of Background Knowledge: Phase 1

Descriptive statistics in Table 4 show some differences in pretest scores and in translation scores between the two groups.

Table 4

Descriptive Statistics

The test of between-subject effects is summarized in Table 5. The effect of availability of background information was found to be statistically significant [F(1, 29)=3.37, p=.048]. The significant values in Table 5 show that the covariate (TOEIC reading scores) does not predict the dependent variable (translation score) in a statistically significant manner since the significance value exceeds .05. Therefore translation scores do not appear to be influenced by TOEIC reading scores. Background information, on the other hand, is a statistically significant factor in predicting students’ translation scores (p=.04).

Table 5

Tests of Between-Subjects Effects

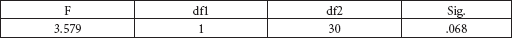

Levene’s Test in Table 6 is not significant, indicating that the group variances are equal and hence the assumption of homogeneity of variance has not been violated.

Table 6

Levene's Test of Equality of Error Variances

Dependent Variable: Translation Score

Tests the null hypothesis that the error variance of the dependent variable is equal across groups.

a Design: Intercept+TOEIC reading +Background Information

4.2 Analysis of Background Information: Phase 2

In order to examine the contribution of background information quantity and quality on translation scores, multiple regression was performed with background information quantity and background information quality as independent variables. Translation scores were the dependent variable. Table 7 shows the mean and standard deviation of the translation score, number of words in the articles gathered for background information and article quality of Group 2.

Table 7

Descriptive Statistics

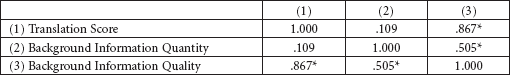

Table 8 gives details of the correlation between each pair of variables. The correlation among the variables shows that background information quality is strongly related to translation score (r=.867) but background information quantity is not (r=.109).

Table 8

Correlations

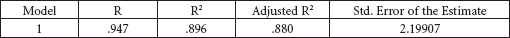

The adjusted R-square (.880) in Table 9 tells us that the model accounts for 88% of variance in the translation score. In other words this model can predict translation quality almost 88% correctly.

Table 9

Model Summary

Standardized Beta Coefficients in Table 10 give a measure of the contribution of each variable to the model. A large value indicates that a unit change in this predictor variable has a large effect on the criterion variable. The t and Sig. (p) values give a rough indication of the impact of each predictor variable – a big absolute t value and small p value suggests that a predictor variable is having a large impact on the criterion variable. Thus the Beta in Table 10 shows that background information quality is a significant predictor of translation score (Beta=1.089, t=10.508, p<.05), while quantity is not.

Table 10

Coefficients

V. Conclusion

The study examined the effect of background information on translation quality. The study further went on to inquire whether the quality and quantity of background information gathered had any influence on the quality of translation. Results indicate that having access to background information does have an effect on translation quality. Interestingly, however, students’ TOEIC reading scores which reflect their general English reading ability do not appear to affect translation quality. In other words, it is the background information rather than the a priori English reading proficiency level that has a more significant influence on the outcome of the translation. The study also found that while background information quality had a significant influence on the translation quality, background information quantity had little effect.

Findings of the study emphasize not only the importance of background information per se, but also its quality in order to ensure translation quality. As is shown in the examples of background information, students these days rely on the Internet in search of resources. However, students in the undergraduate level lack sufficient degree of skills to differentiate authentic, high-quality texts from sources that appear authentic but are actually of little use. As shown in the examples of background information in Appendix C, inappropriate content not only has little utility but also can actually interfere with the translation process and produce translation of poor quality.

Instructors who train students to translate into L2 must take extra precautionary measures to warn students of the pitfall of granting blind trust to everything posted online. One way to do so is to guide students to consult search engines of the target language. A surprising number of students relied more on Korean search engines than English sites in this study.

Cross checking is another method of making sure that the information obtained in one source is confirmed by another online source. In other words, students should always be reminded to be on guard for false or inappropriate information by confirming the veracity of their findings by consulting other sources.

When consulting online sources, one of the most difficult problems facing students is the huge amount of results or ‘hits.’ Instructors should emphasize the importance of figuring out the main idea of the original text and identifying target words before consulting online resources. For example, using only ‘McDonald’s’ as the key word in the search covers too wide a range. Instead, words such as ‘open,’ ‘quality,’ ‘kitchen,’ ‘tour,’ in addition to McDonald’s narrowed the topic down to a manageable level. Since the amount of information gathered did not help much to improve students’ translation output, efficiency in searching for appropriate resources should be emphasized when instructing students.

Introducing students to a wide range of sources is a quick and easy way to steer students away from making mistakes that could easily have been prevented. What is regarded as standard routine for professional translators may and often does come as a novelty to students.

Parties annexes

Annexes

Appendix A

Original Korean Text

맥도날드“매장 속살까지 다 보여드립니다” 주방공개 행사

[동아일보]

한국맥도날드가’반(反)건강식품‘ 이미지에서 벗어나기 위해 다양한 마케팅에 나섰다.

한국맥도날드는 6월6일 전국340개 매장의 주방을 공개해 소비자에게 조리 과정을 보여주는 ’오픈 데이(Open Day)‘ 행사를 연다고16일 밝혔다.

전 세계120여 나라에 진출해 있는 맥도날드가 주방을 공개한 것은 호주에 이어 한국이 두 번째.

한국맥도날드 신언식 사장은“맥도날드는 무조건 건강에 해로운 것처럼 지나치게 공격 당해 왔다”며 “우리 제품이 얼마나 깨끗하고 엄격한 과정을 거쳐 만들어지는지 소비자에게 공개해 정당한 평가를 받겠다”고 말했다.

9세 이상 초등학생부터 참가가 가능하며31일까지 한국맥도날드 홈페이지 (www.mcdonalds.co.kr) 에서 원하는 매장과 시간을 선택해 참가 신청서를 작성하면 된다.

한국맥도날드는 지난달부터 쇠고기, 빵, 감자 등 재료의 영양 정보와 메뉴별 열량을 홈페이지에 공개하는 ’퀄리티 캠페인‘을 벌이고 있다.

2004.5.16 ( 일) 18:30 동아일보

Appendix B

Translation Assessment Grid

Rank from 1 to 5. (5=competent, 1=needs improvement)

Appendix C

Biography

Haeyoung Kim

Prof. Kim received her MA from GSIT at Hankuk University of Foreign Studies and MSTESL and Ph.D in Curriculum and Instruction from the University of Southern California. She is currently professor at the Catholic University of Korea, Department of English Language and Culture, and also a freelance conference interpreter and translator. Her research interest includes language teaching through reading and teaching translation to undergraduate students.

References

- Fraser, J. (1996): “Mapping the Process of Translation”, Meta 41-1, p. 84-96.

- Gabr, M. (2002): “A Skeleton in the Closet: Teaching Translation in Egyptian National Universities”, Translation Journal 6-1, <http://accurapid.com/journal/19edu.htm>

- Gerding-Salas, C. (2000): “Translation: Problems and Solution”, Translation Journal 4-3, <http://accurapid.com/journal/13edu.htm>

- James, D. (2002): “Teaching Japanese-to-English Translation”, Japan Association of Translators, <http://www.jat.org/jtt/teachtrans.html>.

- Kim, H. (2004): “Teaching Translation into the Second Language to Undergraduate Students: Importance of Background Knowledge and Parallel Texts”, Forum 2-1, p. 29-45.

- Dong-A Ilbo (May 17, 2004): 맥도날드 “매장 속살까지 다 보여드립니다” 주방공개 행사 (Original Korean Text).

- McDonald’s set to make history with public tours of restaurants (June 27, 2003): <http://www.mcdonalds.com.au/home/structure.asp?ID=>.

- McDonald's in the Gulf to launch new 'Quality' awareness campaign (Sunday, June 22, 2003): <http://www.ameinfo.com/cgi-bin/cms/page.cgi?page=print;link=25347>.

- Fast Food Fascism (2003): <http://www.commondreams.org/views03/0123-09.htm>

- Foreign food chains spice up marketing (2002): <http://www.foodikorea.com/english/news/news02_view.asp?ns_no=2051&page=1&menu=sja&search=foreign%20food%20chains%20spice%20up%20marketing>

- Fast Food in a Rapid Decline - Anti-American mood, health concern hurt sales <http://foodikorea.co.kr/english/news/news02_view.asp?ns_no=5711&page=11&sj_part=02>

- A brief history of the band : <http://www.summerbash.de/bash/2004/fastfood.htm>.

List of Sources of Text Samples

Liste des figures

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Number of Participants in Each Group

Table 2

Background Information Quality Assessment Criteria

Table 3

Experiment and Analysis Procedure of the Study

Table 4

Descriptive Statistics

Table 5

Tests of Between-Subjects Effects

Table 6

Levene's Test of Equality of Error Variances

Table 7

Descriptive Statistics

Table 8

Correlations

Table 9

Model Summary

Table 10

Coefficients

10.7202/002772ar

10.7202/002772ar