Résumés

Abstract

Since its publication in 1987, Nicole Brossard’s Le désert mauve has come to be considered a radical feminist novel about translation. While most scholarship has focused on translation as a theme and process within the novel, this article reads Brossard’s text as an invitation for intermedial collaboration that is fueled by desire. In this light, I examine American media artist Adriene Jenik’s 1997 computer art project MAUVE DESERT: A CD-ROM Translation as well as Québécois poet Simon Dumas’ multiple engagements with the work in the 2010s (including the website mauvemotel.net and a theatre adaptation featuring Brossard herself).

Résumé

Le désert mauve (1987) de Nicole Brossard est un roman féministe et radical qui porte, entre autres, sur la traduction. La plupart des études critiques qui se penchent sur l’idée de la traduction dans le roman de Brossard, la considèrent comme un thème ou un processus animant l’oeuvre. Dans cet article, j’envisage la traduction autrement : le roman lui-même est une invitation à la collaboration intermédiale inspirée par le désir. C’est sous cette optique que j’étudie MAUVE DESERT: A CD-ROM Translation (1997) de l’artiste américaine Adriene Jenik et les multiples oeuvres s’inspirant du roman de Brossard de Simon Dumas (dont le site web mauvemotel.net et le spectacle Le désert mauve auquel a participé l’auteure elle-même).

Corps de l’article

Québécoise author Nicole Brossard’s difficult, dense, and beautiful novel Le désert mauve was first published in 1987 by L’Hexagone and translated into English by Susanne de Lotbinière-Harwood in 1990 for Coach House Press. At its core, it is a novel about translation, constructed in three parts: an “original” text, the translator’s working notes, and finally the translated text itself. In Brossard’s fiction, Maude Laures, a Montreal-based teacher reads and falls in love with a text (also titled Le désert mauve)[1] written by the fictional American author Laure Angstelle that recounts the adventures of Mélanie, a young lesbian girl coming of age in Tucson, Arizona. Laures decides to translate Angstelle’s text, and three quarters of Brossard’s novel are devoted to the various intellectual and emotional processes she works through as she successfully completes this endeavour. Angstelle’s text and Laures’ translation (titled Mauve, l’horizon) are both presented in French, but clues in the novel guide readers to understanding that the “original” text was apparently written in English. Kristine Anderson considers Brossard’s mise-en-scène of intralingual translation to be a feminist gesture of embodiment. “Brossard’s novel makes the ‘invisible’ woman translator appear,”[2] she writes. Brossard’s novel certainly reveals how arduous, intimate, and exhilarating the translation process can be. In 2010, les Éditions Typo came out with a critical edition of Le désert mauve which assesses the impact of Brossard’s “brillant travail de mise en abyme, ce jeu de miroir qui est une réflexion sur le langage,”[3] as Jean-François Chassay puts it, and in 2015, Sina Queyras added an afterword to the English edition that considers Le désert mauve to be the road map towards a radical, lesbian, utopian “genre- and gender-defying”[4] future. “What can we learn about the female situation from the act of entering and translating a text?”[5] Queyras further asks.

Since its publication in the late 1980s, scholarship on Le désert mauve has primarily moved in two directions. Some scholars have focused on Mélanie, which has led them to investigate what the young girl’s travels through the American desert can tell us about gender, sexuality, freedom, and destruction as they relate to concepts of femininity, womanhood, mobility, and desire.[6] Many others have used Maude Laures as a starting point to think about the power relations implicit within the dynamics of reading, writing, and translation as they are expressed textually across cultures and languages. [7] Most recently, some critical attention has been placed on the desert itself as a sort of main agent in Brossard’s Le désert mauve. Rather than simply being the backdrop to Mélanie’s dreams or the set upon which action occurs, it can now be understood as “an ecocritical hermeneutic device,”[8] or, an “assertive, ‘outside’ influence on the character’s lives”[9] that forces them to reconsider their own experiences of time, place, and space. What needs to be explored further, however, is how Brossard’s conceptualization of images transforms Le désert mauve into a text that begs to be visually translated. After examining the commentary on light and images that emerges from the novel and situating it within a discussion about creative desire, I will explore two such translations, notably American artist Adriene Jenik’s 1997 artwork MAUVE DESERT, a CD-ROM translation[10] and Québécois poet Simon Dumas’ various intermedial encounters with Le désert mauve that span nearly two decades in the early 2000s. Expanding on the work done by Denis Bachand, Sue-Ellen Case, Beverly Curran, and Bruno Lessard, whose explorations of Jenik’s CD-ROM adaptation uncovered the “nouvelles dimensions esthétiques, herméneutiques et critiques”[11] activated by the digital media environment, I will contend that Brossard’s aesthetic engagement is also an erotic one, centered around building an interdisciplinary community of engaged creators. Le désert mauve awakens readers’ desires to dream, play, and experiment. Through Le désert mauve’s sensuous visuality, Brossard encourages their active participation and invites them both into and outside of the text as if they were entering a video installation at an art gallery or partaking in a writing workshop. In some respects, Jenik’s and Dumas’ complex and very involved projects mirror Maude Laures’s (fictional) undertaking: like Laures, they obsessively replay and rework various details of Mélanie’s story, demonstrating that Le désert mauve inhabits its readers and takes hold of their imaginations. As Henri Servin rightly observes, “Le texte est conçu et pensé de telle façon que l’on est littéralement entraîné à participer à le recréer.”[12] Brossard immerses her readers in the desert’s glaring light and challenges them to make this light tangible, visible, and physical in ways that exceed literature’s boundaries and limits. In so doing, she both models and creates an inclusive space for collaboration and exchange. This process triggers what Brian Massumi, in the twentieth anniversary edition of Parables for the Virtual, calls the “vitality affect” or “the perception of one’s own vitality, one’s sense of aliveness, of changeability (often signified as “freedom”).”[13] Although one may easily get lost while navigating Le désert mauve’s complexities, one thing is clear: participating in Brossard’s virtual worlds is a life affirming experience.

Then reality became an IMAGE[14]

Set in the American Southwest, Le désert mauve is a highly visual—one could even say blinding—text. Nearly every page grapples with the meaning that can be ascribed to light as both Mélanie and Maude Laures investigate its origin and the impression it leaves upon humanity. Whether it be from the sun or from the nuclear explosions evoked in the narrative, the light in Le désert mauve fashions the protagonists’ sense of reality. For example, in Part 2, “Un livre à traduire,” Laures identifies how crucial, yet nearly impossible, it is to see clearly in the desert:

Dans le désert, la lumière meurtrit la réalité, déchire en tous sens le tissu fin des couleurs, supprime la forme. Nous n’avons pas de protection contre la lumière car c’est toujours en plein émerveillement que la lumière assaille et soustrait à notre regard le rapport infiniment précieux que nous avons à la réalité. […] La lumière est crue. Comment pourrais-je déserter Mélanie ? Comment entrer dans l’angle de son regard et m’éviter la lumière ? Comment oublier l’instant ? Car c’est bien là l’histoire de ce livre. L’instant porté par un seul symbole : la lumière. La lumière écrasant toute perspective. La lumière tissant l’enjeu. Aucun livre ne peut s’écrire sans enjeu. Enjeu de vie, enjeu de mort, je ne sais encore. Mais aucun livre ne s’écrit sans enjeu, brutal et immédiat. Tout ceci je l’écris en pensant le personnage et l’auteure songeant leur existence comme une chose attirante dans la vie, une souplesse du corps, un rythme dans la chair, un carnaval multipliant les aubes, les soies et les os dans un costume que la lumière embrouille.[15]

Light is coded in negativity and violence: it wounds, it rips, it suppresses, it flattens; it is raw, harsh, strong. And yet, it is considered by Laures to be essential: light weaves together all that is at stake when writing. Without light, there can be no images. Without images, one cannot create. Laures’s thoughts on what it means to write echo the way Mélanie describes her feelings when she finds herself compelled to write for the first time. In both Laure Angstelle’s original text and in Laures’s translation, Mélanie grabs the notebook that sits under the revolver in the glove compartment of her mother’s car and a pencil from Helljoy Garage to jot down some words while out for a desert drive. Afterwards, she is crushed by the experience:

Cette même nuit, la conscience des mots fit le tour de mon sentiment, l’enroula, le fit tourner à contre-sens. J’eus l’impression de mille détours, de gestes graves dans la matière. La sensation de vivre, la sensation de mourir, l’écriture comme une alternative parmi les images. Puis la réalité devint une IMAGE. Je m’endormis à l’aube, ficelée dans mes draps, objet de l’image.[16]

Cette nuit-là, les mots tournèrent longtemps dans ma tête, s’enroulèrent autour de moi, firent tourner l’émotion. J’eus l’impression de mille boucles dans mon corps, des intuitions solennelles au sujet de la vie, à propos de la mort. Puis la réalité devint une IMAGE. Je m’endormis à l’aube, langée, sirène, objet de l’image.[17]

Somewhat paradoxically, Mélanie feels both objectified and rendered more alive by her own creative process. “Puis la réalité devint une IMAGE,” it reads in both versions of her story. It is as if writing were an endless quest for fusion, a direct transition or translation from light to word, from imagination to creation, from bodily experience to representation.

According to Catherine Perry, the young girl is imprisoned by patriarchy’s hold over language. For this reason, her attempt to become a writer is both empowering and futile. “L’écriture comporte donc un double aspect, positif et négatif : en tant qu’acte, elle libère l’énergie du sujet féminin, pour la réprimer aussitôt puisque les mots sont indissociables de la sédimentation culturelle dont ils sont chargés,”[18] Perry contends. Nevertheless, Brossard undermines what Perry calls “le discours masculin”[19] by imagining a situation in which a woman (Laures) is so moved by another woman’s text (Angstelle’s Le désert mauve) that she decides to teach herself how to translate it. If Mélanie’s struggle to express herself is an illustration of the challenges faced by those who attempt to articulate their experience using language, Laures’s successful translation is proof emancipation “ne pourra se trouver d’abord que dans le domaine de l’imagination créatrice.”[20] Julie Gerk Hernandes also identifies the metastructure of Brossard’s Le désert mauve to be the site of liberating exchange, a site that is intimately related to the desert setting: “Maude is seduced by reading Mélanie’s experience in the desert, which is written by Laure and by Brossard on the macro level. While venturing through and writing about the desert landscape, Mélanie/Laure/Maude/Brossard is/are forging a virtual community and reappropriating the very space that patriarchal power invades.”[21] In other words, the desert’s unwavering light gives life to a creative community within Le désert mauve’s fictional world.

Brossard’s sustained focus throughout the novel on the interplay of light and reality is arguably a call for the kind of representation that is not limited by the confines of textuality. In her notes, Maude Laures carefully studies how Mélanie describes the desert light in order to elucidate the meaning of statements such as this one: “J’avais quinze ans et de toutes mes forces j’appuyais sur mes pensées pour qu’elles penchent la réalité du côté de la lumière.”[22] Laures ruminates on what it can mean to “slant reality towards the light”[23] and concludes that while reality can surely be found by going back to those “choses imagées”[24] that Mélanie only sees in the blinding light of the desert, “à tout cela il y a certainement, pensons-nous, un autre sens, une autre version.”[25] By bringing in the idea of other meanings and versions of the reality that Mélanie tries to describe and that Laures has tasked herself with translating, Brossard opens up the possibility for the existence of new interpretations of Le désert mauve. In fact, the way she presents Laures’ engagement with Angstelle’s text, that is, as an emotional and embodied rather than a purely intellectual endeavor, seems to invite an engagement that exceeds the boundaries of reading. For example, in the following passage, the unidentified omniscient narrator who describes Laures as she prepares to translate Le désert mauve imagines her bringing Mélanie’s story to life in all its sensuality.

S’astreindre à comprendre, ne rien négliger malgré le flot dévergondé des mots. Susciter de l’événement. Oui, un dialogue. Obliger Mélanie à la conversation. L’installer au bord de la piscine et la faire parler. Mettre de la couleur dans ses cheveux, des traits sur son visage. Oui, un dialogue somptueux, une dépense déraisonnable de mots et d’expressions, une suite qui, construite autour d’une idée, dériverait à ce point que Maude Laures aurait le temps de circuler paisiblement autour du motel, de pénétrer dans la chambre de la mère et de Lorna. Un dialogue qui lui permettrait, Mélanie emportée par les mots, de voyager à ses côtés dans la Meteor, d’ouvrir la boîte à gants, de toucher le revolver, de feuilleter le carnet d’entretien[26].

Decoding Mélanie’s world is a very intimate process, and, as the narrator describes it, Laures is working with “des images qui permettent de distribuer le consentement.”[27] Conceptualized in this way, Brossard’s Le désert mauve is more than a text waiting for a reader to interpret its signs and create meaning. It is an invitation for collaboration that is fueled by desire.

As the following analyses will reveal, Adriene Jenik and Simon Dumas are two readers who, after seeking Brossard’s approval, willingly and with varying levels of success, entered into dialogue with her novel by taking up its call for visuality and consenting to the images it evokes. As both experts and critics, participants and creators, Jenik’s and Dumas’s objectives are similar to those of Stephen Shaviro, whose aim in Post-Cinematic Affect is “to develop an account of what it feels like to live in the early twenty-first century.” [28] Pushed by desire and intellectually stimulated by Brossard’s work, Jenik and Dumas strive to identify what if feels like to live in the Désert mauve environment. However, where Shaviro determines how media works “give voice (or better, give sounds and images) to a kind of ambient, free-floating sensibility that permeates society today,”[29] Jenik and Dumas channel the “affective and aesthetic flows”[30] that permeate Brossard’s novel. Instead of studying how media works are “productive, in the sense that they do not represent social processes, so much as they participate actively in these processes and help to constitute them,”[31] they consciously create media works that function as what Shaviro calls “affective maps,”[32] bridging the gap between Brossard’s work, the social processes that informed its creation and continue to inform its reception, and the feelings to which these factors gives rise. Curiously, in attempting to understand the Désert mauve universe and unravel its secrets, both artists were first drawn to reflect upon the dynamics of their own subject positions. “Me voici donc en train de porter un regard sur la figure de la jeune fille depuis le côté hétérosexuel—straight—de l’appellation, et d’y ajouter quelques lignes,”[33] wrote Dumas to Brossard in 2010, suddenly aware of or insecure about the power relation he was inevitably reproducing by engaging with the work. “I am taking it slowly though, and trying to savor each moment in the process (Maude Laures didn’t seem rushed!)”[34] explained a somewhat self-conscious Jenik to Brossard in a fax dated December 17, 1994. Challenged by Le désert mauve’s density and, perhaps, affected by the desire the novel awakens in them, both Jenik and Dumas were led to question their own legitimacy as producers of art, accidental or symbolic usurpers of another’s text, experiencers of desire. Yet it was precisely this line of questioning that allowed them to become Brossard’s visual translators. In a message to Dumas from 2016, Brossard admits that images, for her, are always uncertain, hazy: “Je suis une visuelle mais je n’ai pas le sens de l’image.”[35] Created with Brossard’s blessing and participation, Jenik’s and Dumas’s works give a visual identity to the blinding light that brings Brossard’s text outside of the confines of the novel and into what she considers to be the virtual realm.[36]

Adriene Jenik, digitally translating desire

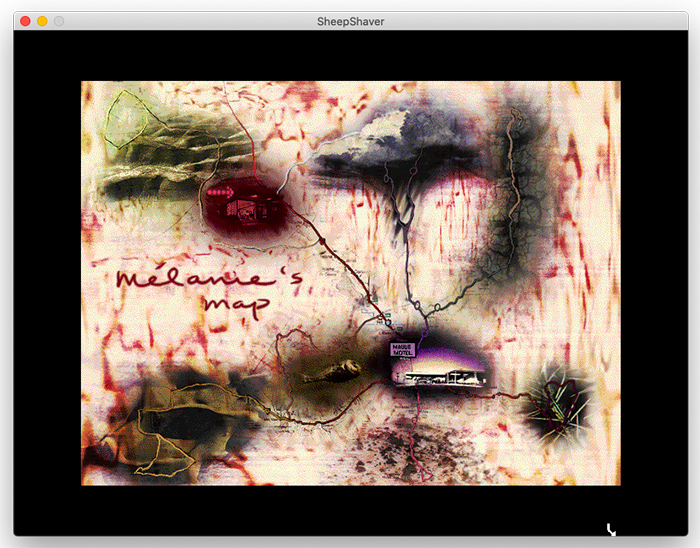

Produced in the early 1990s and published in 1997, or at a time when, as Adriene Jenik puts it, “colleagues would just talk to me about how women’s brains were different than men’s brains and women weren’t cut out to be programmers”[37] and “there was no market for electronic media for women, ”[38] MAUVE DESERT: A CD-ROM Translation is a time capsule, an artistic relic, and an early example of computer art by women. As Bruno Lessard explains in his study The Art of Subtraction. Digital Adaptation and the Object Image, Jenik’s work “is considered a landmark piece of ‘interactive’ storytelling and one of the earliest instances of CD-ROM adaptation.”[39] It brings Nicole Brossard’s Le désert mauve to life in a sort of “choose your own adventure” kind of way because the reader/player is invited into the Mercury Meteor that fifteen-year-old Mélanie regularly borrows from her mother “au moment le plus inattendu,”[40] a vantage point from which they can determine the direction the narrative will take by deciding where, on what Jenik calls “Mélanie’s map,” the car will travel (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Still from Adriene Jenik, MAUVE DESERT: A CD-ROM Translation, Los Angeles, Shifting Horizons Productions, 1997.

In this way, Jenik proposes “myriad alternative conditions to the narrative regime”[41] and explores the freedoms and limits of agency in the digital age. While Sue-Ellen Case considers the image of Mélanie driving to be both an anchoring point “to which all the reading returns”[42] and “the interface between the user of the CD-ROM and the print version [of Brossard’s text],”[43] Denis Bachand observes that the “métaphore de navigation”[44] cleverly woven by Jenik in MAUVE DESERT acts as a “pacte de lecture qui détermine la position du récepteur interpellé sur le plan de la conation par le dispositif qui le presse d’activer les boutons permettant de migrer d’un bloc audio-scripto-visuel à un autre, d’une lexie à une autre.”[45] In Jenik’s CD-ROM translation, the reader/player is meant to embody Mélanie and not only see the world through her eyes but also make decisions and experience their consequences on her behalf.[46] In the context of 1990s computer art, this was a radical innovation. As Maria Klonaris and Katerina Thomadaki have written about their 1983 video installation Orlando-Hermaphrodite II inspired by Virginia Woolf’s novel Orlando, the feminine becomes a disrupting force at the intersection of art and technology, a force that ruins gender order.[47] Through its inclusive and open-ended framework, Jenik’s unique work stands as counterpoint to the age-old, gendered dynamics of the road, contesting what Sidonie Smith calls the “performative act of riderly masculinity,”[48] and allows for the vitality of unbridled adolescence to be shared and experienced by every reader/player who can access it.

Jenik’s programming, however, immediately subverts what at the time were considered by some to be the “liberatory and nonhierarchical”[49] aspects of interactive media in two ways: first, by forcing the reader/player to sit through approximately one and half-minute long video clips every time Mélanie drives (see Figure 2), and secondly, by having Longman—a character who resembles Robert Oppenheimer, head of the Los Alamos Laboratory and the Manhattan Project, and who is thought to have shot Angela Parkins, Mélanie’s love interest, at the end of Angestelle’s Le désert mauve—randomly appear and shut the whole story down (see Figure 3).

Figure 2

Excerpt from Adriene Jenik, MAUVE DESERT: A CD-ROM Translation, Los Angeles, Shifting Horizons Productions, 1997.

Figure 3

Excerpt from Adriene Jenik, MAUVE DESERT: A CD-ROM Translation, Los Angeles, Shifting Horizons Productions, 1997.

For Jenik, the drives are key in ensuring that the CD-ROM’s navigators do not click away from the text adapted from Brossard’s novel. Her goal is for readers to “really be there, and have the language flow over them and through them.”[50] She wants “the language to have [a] chance to penetrate.”[51] As for Longman’s intrusions, these startling occurrences bring the element of fear into Jenik’s work and function as a sort defamiliarizing device, forcing navigators to acknowledge their own paradoxical lack of agency within a supposedly user-controlled domain. According to Bachand, this “effet de cassure,”[52] unique to the CD-ROM format, “ramène au principe de réalité”[53] because the reader/player cannot help but question whether the technology is functioning correctly, an effect that is only further amplified with the passage of time and the CD-ROM’s progressive obsolescence. Given that Longman literally interrupts whatever is happening in the CD-ROM at seemingly random times, and given that he encapsulates destructive masculinity in Brossard’s novel, Jenik’s visual rendering is also, arguably, a visceral commentary on patriarchy’s endless power that is far more disconcerting than the eight short Longman chapters in Brossard’s novel that fragment Mélanie’s narrative.

What ends up emerging from the simple yet effective dynamic coded by Jenik—the one that exists between the young girl driving and the strange man pacing around in a hotel room who interrupts her journey—is the realization that even in hypermedia the body is present and activated. Though it is impossible to be fully immersed in the CD-ROM desert world created by Jenik due to the various constraints and disturbances she programmed in, the computer artwork, like Brossard’s novel, sweeps readers into its narrative flow. According to Jenik, this is a natural effect produced by the technology’s fusion with Brossard’s text. By “including the viewer in the navigational system,”[54] Jenik ensures that there is “identification in terms of moving into the landscape of desire.”[55] In this way, she also digitally mirrors the process of sorting and selecting that is inherent to the acts of translation represented in Brossard’s novel. Jenik’s reader/player makes choices (regarding regard to language, destination, order) based on their personal preferences thereby tailoring their experience of Mélanie’s story to their own desires and priorities. No journey through the CD-ROM is ever the same.

This is not unlike the way in which Brossard’s narrator, in the section “Un livre à traduire,” characterizes the decision-making process that is an integral part of the urge to translate: “Un matin de neige abondante, [Maude Laures] décida de l’existence parmi les scènes et les symptômes de certains qui, dans la langue de Laure Angstelle, l’avaient séduite.”[56] Examined in terms of seduction, Maude Laures—the fictional character invented by Brossard—and Adriene Jenik—the contemporary artist inspired by her work—had arguably similar experiences with Le désert mauve, but Jenik took her engagement further than Laures did by creating an interactive and visual system that endlessly gives rise to new desires and new engagements. Also, as Bruno Lessard rightly points out, by imagining Maude Laures at work, by situating her on a map of Montréal found in the glove compartment of Mélanie’s car, and by depicting a woman’s lips as she mouths the words she is translating, Jenik carves out an important space in her artwork for reflecting on the dynamics of translation from a feminist and embodied perspective:[57]

Jenik’s Maud Laures accentuates the necessary oral activity of the translator who has to hear and mouth the words in order to know if they are appropriate. The oral dimension of Brossard’s poetic output is underlined, and the sentences from the novel are activated in another medium, the human voice, while the printed word on the page is left aside. Moreover, the usual silent reading practices give way to the body of the translator in the reading and reciting of the words. Maude Laures’ practice as a translator joins a feminist conception of language and fascination with the actual sounds of the words that remain mute on the page.[58]

Although the transformation of a print document into an electronic text such as this one is, first and foremost, according to N. Katherine Hayles, a form of media translation, it is also, “inevitably,” Hayles states, “an act of interpretation.”[59] Through its attention to the sensory experience activated by Brossard’s work, Jenik reveals the role that desire plays in the interpretive process.

In fact, MAUVE DESERT: A CD-ROM Translation can be considered an experiment in territorialization as Lawrence Grossberg (following Deleuze and Guattari) defines the term in his essay collection Dancing in Spite of Myself. “To speak of popular culture as having a territorializing power is to suggest… [an image] … in which the places of stability are constructed along the paths of mobility,”[60] Grossberg writes. “Where you stop is defined as you are moving, by the rhythms of your movements. Just as the trajectories and rhythms of your movements are defined as you stop, by the rhythms of your investments or places. It is a matter of what matters and the possibilities of transformation and elaboration,”[61] he adds. Although navigational freedom is an apparent (yet not fully attainable) characteristic of the CD-ROM format, Jenik guides the reader/player on a path through Brossard’s desert world that reflects her own personal journey with the work. She guides them to the places in which she stopped as she herself was moving; she shares with them the affective map of her investments.

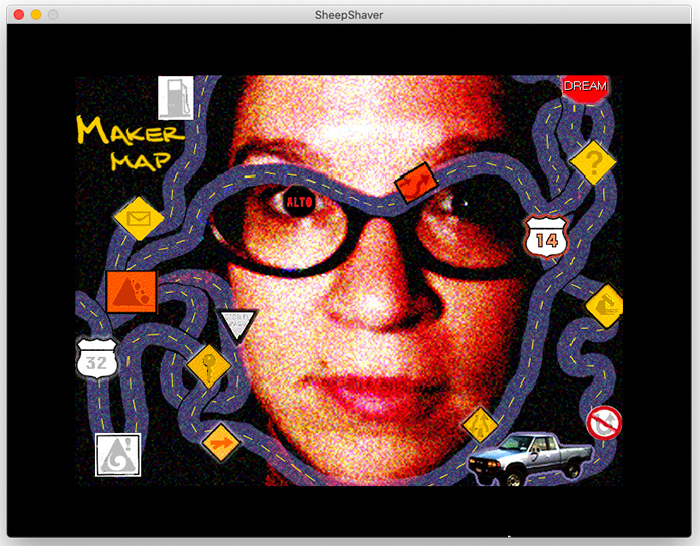

Jenik meditates on the specificity of her own interpretation both visually—for example, by incorporating her own annotated copy of Le désert mauve into the visual aesthetic of the CD-ROM—and as an element of content, when she includes what she calls the Maker’s Map in the glove box of Mélanie’s car (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Still from Adriene Jenik, MAUVE DESERT: A CD-ROM Translation, Los Angeles, Shifting Horizons Productions, 1997.

In this way, she illustrates how the reader—who is a person with experiences, an identity, a past, a future, likes, dislikes and desires—and the text—that elusive, imagined thing—interact: “The body represented within the virtual space is always already mutated, joined through a flexible, multilayered interface with the user’s body on the other side of the screen,”[62] Hayles writes. Or, as Lev Manovich puts it in his 2001 study The Language of New Media, “Interactive computer media… externalize[s] and objectif[ies] the mind’s operations.”[63] In other words, the private associations one creates when a work of culture exerts its “territorializing power,”[64] are rendered not only visual but also public in works such as the MAUVE DESERT CD-ROM. “What [is] hidden in an individual [new media designer]’s mind becomes shared,”[65] Manovich writes. This, in turn, provokes either identification or alienation in the reader/player who, as Manovich rightly points out, is asked to “mistake the structure of somebody else’s mind for [their] own.”[66] By allowing the reader/player a temporary sense of agency within the system, Jenik immerses them in the mirage that is Le désert mauve, shows them what it feels like to live in that (virtual) reality, and then breaks the illusion when her personal desire for connection is revealed: “In Jenik’s CD-ROM translation,” explains Beverly Curran, “the uncomfortable light of the desert is modulated into the desire of a woman writer and her reader to tutoyer in the flickering light of the computer screen[67].”

“Je suis dans la réalité jusqu’au cou,”[68] thinks Mélanie as she slips into the pool at the Red Arrow Motel. What for Brossard is fluid like the heavily chlorinated water in a roadside Arizona motel, in other words, that not quite refreshing sensation we can almost feel on our skin as we read Le désert mauve, Hayles describes as a kind of flickering: “The transformation of the text from durable inscription into a flickering signifier means that it is mutable in ways that print is not, and this mutability serves as a visible mark of the multiple levels of encoding/decoding intervening between user and text.”[69] This is the fluidity or flickering of meaning, which is different from reader to reader, from text to text, from translation to translation. Jenik expertly harnesses the almost limitless potential of Brossard’s novel in her pioneering digital media work.

Simon Dumas’s multimedia Mélanie

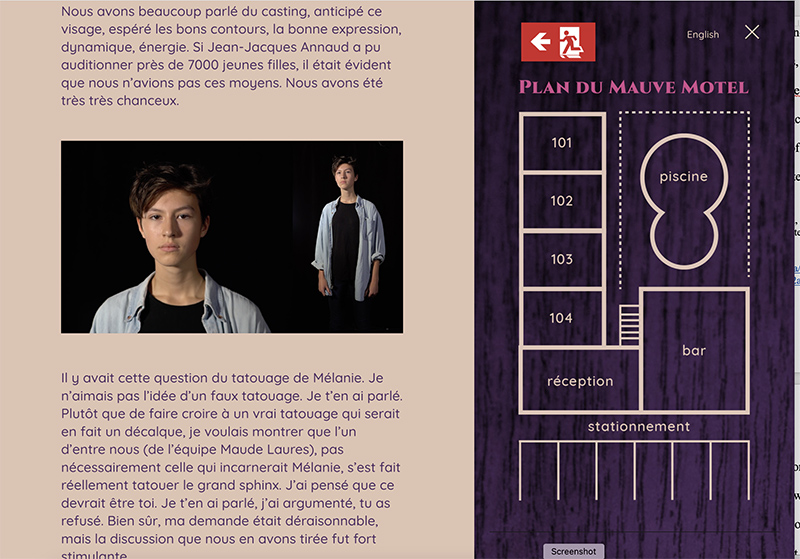

The challenge to resist objectifying the object of one’s desire is precisely that which Québécois poet Simon Dumas, for whom Mélanie has been a source of fascination and inspiration since the early 2000s, took up when he embarked on his multimedia journey through and with Le désert mauve. Dumas’s important contributions to the Désert mauve universe have yet to be studied. The first traces of his engagement with the character Mélanie can be found on the website http://mauvemotel.net, an affective map of sorts, which was created to house the various elements of the epistolary exchange occurring between Dumas and Nicole Brossard in preparation for what would become the Le désert mauve theatre play (which was first performed at L’Espace Go in Montreal in 2018.)[70] Not unlike Jenik’s CD-ROM, which also comprises a repository for the postcards, letters, faxes, and eventually emails Jenik and Brossard exchanged in the 90s, http://mauvemotel.net takes the visual form of a hyperlinked hotel blueprint (see Figure 5).

Figure 5

Screenshot of the website Simon Dumas, Les univers parallèles du Mauve motel, 2018, https://mauvemotel.net/ (accessed 8 December 2022).

Clicking on each hotel room leads to texts and images about the themes explored by the two writers. For example, Room 101 is devoted to “L’auto, le motel, le cinema, un marriage” and Room 102 is on the topic of “La jeune fille, le cinéma, le revolver, la nuit;” at the bar, we find a one-hour long recorded conversation between Dumas and Brossard; at the motel reception, we can read some very polite early emails between the two; thrown into the pool are all the historical, cinematic, musical, and other references; and, finally, in the parking lot, we find the credits to the project.[71] No explanation is provided for the website’s organizational structure, leaving the user the freedom to explore the site and draw their own conclusions about the affinities and associations Dumas weaves.

As we can see from this web archive, in April 16, 2010, Dumas informed Brossard that he was in Mexico on a writer’s residency working on a project about Mélanie. “Je veux matérialiser l’image mentale que j’en ai. Je cherche dans Mexico une Mélanie possible,”[72] he wrote, adding that he was distributing copies of El desierto malva “à la volée”[73] with the hope of “crée[r] de nouvelles fans de Nicole Brossard. Notamment Lyliana Chavez, vingt-quatre ans, jeune militante feministe qui me disait…qu’elle veut faire un travail universitaire sur ton roman.”[74] One month later, Brossard replied and gave him the blessing to “mettre en images ta lecture du Désert mauve.”[75] Throughout the initial stages of the process, Dumas could not help but reflect on the hierarchy between visual and material images present in his own understanding of art, as if intimate knowledge of literature could somehow give him access to better, more complete, more profound visual representations: “Le langage constitue une autre forme de représentation. Différente du théâtre, du cinéma, mais aussi de la couleur, la pierre. Il y a, dans le rapport au langage, comme une distance qui est en même temps une virtualité. Non pas que les mots soient désincarnés, mais bien qu’ils s’incarnent dans la matière invisible du corps. Une invisible intimité.”[76] It is no surprise, then, that Dumas’s first sustained entry point to Le désert mauve was through poetry: in 2013, he published the book of poems Mélanie where the teenaged girl appears as both an object of affection, lust, desire and as a beacon of the youthful freedom that Dumas wished he could still access or, at the very least, tap into.

The correspondence archive reveals that Brossard herself struggled with Mélanie’s potential objectification. She was so concerned with Mélanie’s ability to think and act that she refused to label her a young girl because this would call up theories and discourses that do not adequately describe her. “Il n’y a qu’une seule jeune fille dans Le désert mauve. Ce n’est pas Mélanie, mais sa cousine Grazie, avec laquelle Mélanie aimerait bien coucher… Toute ‘jeune fille’ est ainsi nommée uniquement à cause du regard masculin,” [77] affirms Brossard with authority. In her article “Girls Girls Girls” on the young girl created by capitalism in Post-War France, art historian Jen Kennedy points out that “while the idea of the Young Girl is sometimes separate from the actuality of being a young girl, this intellectual compartmentalization is tricky and difficult to maintain, especially because images often precede language in redefining what it means to be young and female.”[78] Although the opposite is literally true for Mélanie, who first came to life in novel-form and then later was materialized into an image by Jenik and Dumas, Brossard’s poetic depictions were originally intended to wrench her out of heteropatriarchy’s expectations and grasp. She was not destined to be Tiqqun’s Jeune-Fille, “bonne… à consommer ”[79] in Premiers matériaux pour une théorie de la Jeune-Fille nor was she intended to be seen as “l’esclave radieu[se] [du Spectacle]”.[80] But when Dumas presses Brossard on who exactly Mélanie is, how she looks, and how she’s changed over the years, Brossard disembodies her completely: “Mélanie est un condensé de vitalité, d’intelligence, de rébellion, de désir, de solitude, de contestation… Comme si elle était une essence plutôt qu’un personnage… Rien de féminin dans son futur, sinon l’amour d’une autre femme.”[81] This, in itself, is noteworthy because it indicates that even Brossard could not find a way out of the representational impasse that the young female body seems to create. “Mélanie est Mélanie, au mieux une adolescente… Elle pourrait aussi être une teenager au sens où James Dean en fut un,”[82] Brossard adds.

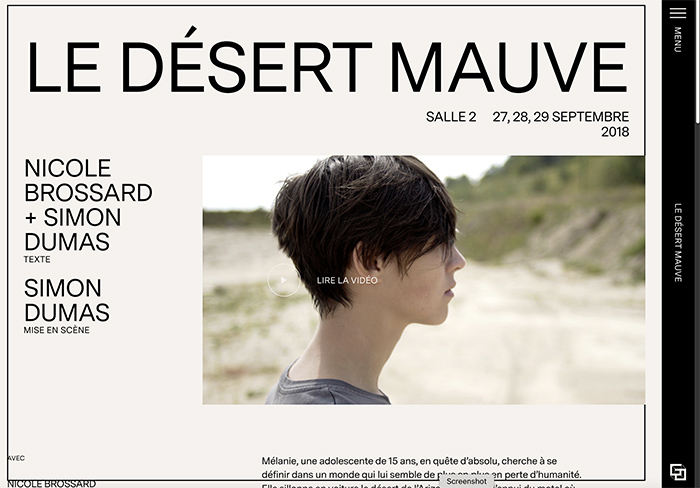

As further conversations reveal, selecting the actress who would play Mélanie in a short film that would be projected on the stage as part of the Désert mauve performance was no easy feat, for, as Dumas writes, “le corps de l’actrice que nous aurons choisie, sa façon d’habiter son visage, ses gestes, fera écran entre Mélanie et l’image que tu t’en fais, que je m’en fais.”[83] If the actress is a screen between Mélanie the fictional character and Mélanie as Brossard and Dumas separately imagine her, then she is also a conduit for an idea or an essence that is by definition multiple. She exists in an impossible tension between the various kinds of representation that any adaptation activates, be they textual, visual, or imaginary. In a screen test found on http://mauvemotel.net, Judith Rompré can be seen slipping into the role of Mélanie for the first time (see Figure 6).

Figure 6

Screenshot of the website Simon Dumas, Les univers parallèles du Mauve motel, 2018, https://mauvemotel.net/piscine/ (accessed 8 December 2022).

When instructed by Brossard and Dumas to manifest anger and wonder at the camera, she remains impassive, still, opaque, yet malleable. Rompré goes on to portray Mélanie in this very manner: calm, serious, blank when Mélanie shoots a gun in the desert, when Mélanie’s mother refuses to read her writing, when Angela Parkins dies in Mélanie’s arms (see Figures 7–8).

Figure 7

Screenshot of the website Espacego, 2018, https://espacego.com/les-spectacles/2018-2019/le-desert-mauve/ (accessed 8 December 2022)

Figure 8

Still from the performance of Le désert mauve by Simon Dumas with Nicole Brossard, Production Rhizome, Espace Go, Montreal, September 27–29 2018.

Things happen to her; things happen around her. Despite all the conversations and planning that went into deciding how exactly to depict Mélanie, Rompré perfectly incarnates the empty shell theorized by Tiqqun, the Jeune-Fille as a surface upon which Dumas, Brossard, the characters in Le désert mauve and even the spectators project their fears and desires. Dumas’s Le désert mauve makes it clear that while Mélanie, at first, was a fictional character in a feminist novel with seemingly unlimited agency, when she is brought to life, she almost inevitably is transformed into a being who incarnates desire. “Je n’étais qu’une forme désirante dans le contour de l’aura qui entourait l’humanité,”[84] Mélanie thinks as she drives.

As if to underscore the virtuality of representation and the fundamentally mediated nature of all such interpretative exercises, at one point in the Désert mauve theatre play, Brossard and Dumas sit at a desk and spar intellectually, proposing complimentary but incongruous readings of Le désert mauve and claiming authorship over various aspects of the project (see Figure 9).

Figure 9

Excerpt from the performance of Le désert mauve by Simon Dumas with Nicole Brossard, Production Rhizome, Espace Go, Montreal, September 27–29 2018.

They go so far as to compete over Mélanie, debating who she is and who she can be. Paradoxically, the two authors limit, in this way, the horizon of what is possible for Mélanie and impose their vision on her freedom. Although she does as she pleases in both Brossard’s novel and Dumas’s representation—she writes feverishly, she drives fast, she hangs out at bars—she is not fully independent. She dreams of embodiment, of being fully present within herself, of “un corps devant l’impensable, un corps qui [peut] filtrer le mensonge, la violence, la peur, la nuit comme à l’aube, un corps capable d’écarter la foudre, d’éloigner le cri tenace d’instinct,”[85] and yet this body is never truly her own. This is especially apparent when Dumas dresses as Robert Oppenheimer and reads fragments of Oppenheimer’s writing out loud while Mélanie spends time in an anonymous motel room, thinking and writing. Immediately afterwards, Dumas sits down next to Brossard on stage and the authors observe Mélanie as she touches herself (see Figure 10).

Figure 10

Excerpt from the performance of Le désert mauve by Simon Dumas with Nicole Brossard, Production Rhizome, Espace Go, Montreal, September 27–29 2018.

As for Mélanie, she looks in a mirror: she seems to be facing the authors, facing the audience, facing the invisible camera. In these moments, she is objectified by language, by patriarchy, and by the desiring gaze. What is actually on display here? Is it Mélanie’s journey to self-discovery, writing, and self-actualization? Or is it her subjugation? Is it the performance of desire? Or is it the performance of desire, Mélanie’s desire, unleashed in the face of the social structures that want to contain it, enjoy it, quell it, profit from it, erase it? This is an intimate, even uncomfortable scene because it immerses the audience in what Kaja Silverman would call Brossard’s and Dumas’ competing “desiring subjectivities”[86] while rendering Mélanie the not quite passive object of their gaze. Although there is no peephole, two levels of voyeurism can clearly be identified as the authors are simultaneously part of the audience, experiencing the Désert mauve film narrative as it unfolds, and on stage, creating, debating, affecting not only the course of the play but also our understanding or interpretation of the events. Their obsession with images and imagination is made plain. Dumas’ mise en scène draws our attention to how little agency teenage girls truly have. The screen through which we see Mélanie when she is finally made visible is drenched in both heterosexual and lesbian desire.

Steven Shaviro’s thoughts on intimacy, allure, and popularity are helpful in unraveling the powers and pressures at work here. “Intimacy,” Shaviro writes, “is what we call the situation in which people try to probe each other’s hidden depths.”[87] Allure, explains Shaviro following Graham Harman, is more profound, slippery, and affectively charged:

What Harman calls allure is the way in which an object does not just display certain particular qualities to me, but also insinuates the presence of a hidden, deeper level of existence. The alluring object explicitly calls attention to the fact that it is something more than, and other than, the bundle of qualities that it presents to me. I experience allure whenever I am intimate with someone, or when I am obsessed with someone or something. But allure is not just my own projection. For any object that I encounter really is deeper than, and other than, what I am able to grasp of it. And the object becomes alluring, precisely to the extent that it forces me to acknowledge this hidden depth, instead of ignoring it.[88]

Shaviro contends that pop stars and celebrities are fundamentally alluring because they embody a promise of happiness that is forever deferred and, as a result, easily commodified.[89] Although this is not true of Brossard’s Mélanie, who has yet to make her entry on the global stage, she occupies a place akin to that of the pop star within the literary and artistic circles sympathetic to Brossard’s work. She is alluring precisely because she inspires readers, players, and spectators to attempt to reach her and through these attempts to imagine what it feels like to be in her presence, what it feels like to be alive alongside her.

Conclusion

In Nicole Brossard’s Le désert mauve, Mélanie is both a character and a prompt. In Simon Dumas’s theatre play, she is the object of debate in a theoretical showdown between Brossard’s lesbian utopianism and Dumas’s incarnation of patriarchal destruction, just as in Adriene Jenik’s CD-ROM, she is the shadowy driver in an unmanned (or unwomaned) car traveling across digital landscapes of the Sonoran Desert. Mélanie’s story is what fascinates; her story is what is translated, as much by Maude Laures, Adriene Jenik, and Simon Dumas as by Brossard herself, who has had a hand in all the Désert mauve afterlives. Despite this fact, Mélanie is not the main protagonist of Le désert mauve. It is not the Mercury Meteor, the notebook, the revolver, nuclear research, desire, or even the act of translating, either. The main protagonist of Le désert mauve is, as Jean-François Chassay writes, representation itself. “Roman sur la mort, sur l’apocalypse technologique moderne, sur l’écriture et sur la traduction, sur l’Amérique et ses paysages, Le désert mauve est au fond un roman sur la représentation. Quelle est la meilleure façon de poser un regard critique sur le réel à travers la littérature ? Comment rendre compte du fonctionnement même de la pensée à l’oeuvre dans le travail sur un texte ? ”[90] Chassay asks. For Adriene Jenik and Simon Dumas, the answer is simple: by making it visual, by giving the phantomatic processes of fiction and the desert’s blinding light a tangible yet always changing form.

One could argue that images arrest us. They overwhelm us, they bury us. With their fixity and flatness, they make it hard to truly see like a sandstorm obscures the sun. While it is conceivable—and even likely—that Nicole Brossard was channeling the postmodern critique of image culture in her novel Le désert mauve, she was also presenting visual space as a zone of possibility and possible collaboration. “Puis la réalité devint une IMAGE.”[91] This is a sentence that Laure Angstelle writes and that Maude Laures chooses not to translate, chooses to keep as is. It is significant. “Puis la réalité devint une IMAGE.” This is the sentence that accompanies Mélanie’s first attempts at writing, an experience that goes hand in hand with her sexual awakening. “Puis la réalité devint une IMAGE.” This is Brossard’s invitation to her readers. “Ce que nous appelons fiction—par opposition à la réalité—,” writes Brossard on http://mauvemotel.net, “est tout simplement ce qui est vrai, plausible et qui, parce qu’empêché pour toutes sortes de raisons (censure, marginalité, hors norme, travail quotidien-prosaïque) est rêvé, imaginé, fantasmé et conçu en dehors de l’évidence matérielle ou culturelle.”[92] In other words, fiction, she claims, can free us. The fictional Désert mauve reality that Brossard’s novel represents became an image in Adriene Jenik’s and in Simon Dumas’s interpretations. While Jenik offered readers/players a chance to navigate with Mélanie along pre-programmed but new avenues, Dumas’s multimedia engagements with the young girl exposed how easily she slips away, no matter how thoughtfully she is pursued. Perhaps virtual reality (as in VR) is the natural next step in the Désert mauve experience. What better way to help build the feminist utopia that Mélanie hopes, one day, to create for herself within Brossard’s fiction than to step into her world, to step into the flickering, and take Longman down with Mélanie’s gun?

Parties annexes

Biographical note

Ania Wroblewski (Ph.D., Université de Montréal) is an Assistant Professor of French at the University of Guelph. A specialist in twentieth and twenty-first century French literature, art, and visual culture, her research centers on the meeting point of literature and its audiences. Her first book, titled La vie des autres. Sophie Calle et Annie Ernaux, artistes hors-la-loi (PUM, 2016) was a finalist for both the Canada Prize in the Humanities and Social Sciences 2017 and the Prix du meilleur livre de l’APFUCC 2017. Her current research, titled Les femmes en cavale, studies representations of women on the run by Nicole Brossard, Sophie Calle, and Catherine Mavrikakis, among others.

Notes

-

[1]

Nicole Brossard, Le désert mauve, Montréal, Éditions TYPO, 2010.

-

[2]

Kristine J. Anderson, “Revealing the Body Bilingual: Quebec Feminists and Recent Translation Theory,” Studies in the Humanities, December 1995, p. 72.

-

[3]

Jean-François Chassay, “Préface. L’érosion comme principe vital,” in Nicole Brossard, Le désert mauve, Montréal, Éditions TYPO, 2010, p. 10.

-

[4]

Sina Queyras, “An Afterword,” in Nicole Brossard, Mauve Desert, translated by Susanne de Lotbinière-Harwood, Toronto, Coach House Book, 2015, p. 204.

-

[5]

Ibid., p. 205.

-

[6]

See for example: Catherine Perry, “L’imagination créatrice dans Le Désert mauve : transfiguration de la réalité dans le projet féministe,” Voix et Images, vol. 19, no. 3, 1994, p. 585–607; Larry Steele, “Fascination et déception : l’Amérique dans Le désert mauve de Nicole Brossard et Une histoire américaine de Jacques Godbout,” Dalhousie French Studies, vol. 64, Fall 2003, p. 69–74, and sections on Le désert mauve in Marie Carrière’s Writing in the Feminine in French and English Canada. A Question of Ethics, Toronto, The University of Toronto Press, 2002, among others.

-

[7]

See for example: Katherine Conley, “The Spiral as Möbius Strip: Inside/Outside Le Désert Mauve,” Québec Studies, no. 19, 1995, p. 143-153; Alice Parker, “The Mauve Horizon of Nicole Brossard,” Québec Studies, no. 10, 1990, p. 107–119, and Patricia Godbout, “Le traducteur fictif dans la littérature québécoise : notes et réflexions,” Cahiers franco-canadiens de l’Ouest, vol. 22, no. 2, 2010, p. 163–175, among others.

-

[8]

Julie Gerk Hernandez, “Fertile Theoretical Ground: An Ecocritical Reading of Nicole Brossard’s Mauve Desert,” Critique: Studies in Contemporary Fiction, vol. 49, no. 3, 2008, p. 257.

-

[9]

Ibid., p. 268.

-

[10]

Please note : In the following pages, I will refer to Brossard’s novel as Le désert mauve or Désert mauve, depending on the flow of the sentence. When referring to Jenik’s work, I will use the title MAUVE DESERT.

-

[11]

Denis Bachand, “Du roman au cédérom. Le désert mauve de Nicole Brossard,” Cinéma et littérature au Québec: rencontres médiatiques, Montréal, XYZ éditeur, 2003, p. 45.

-

[12]

Henri Servin, “Le désert mauve de Nicole Brossard, ou l’indicible référent,” Québec Studies, no. 13, automne 1991–printemps 1992, p. 56.

-

[13]

Brian Massumi, “Keywords for Affect,” Parables for the Virtual. Movement, Affect, Sensation [2002], Durham, Duke University Press, 2021, p. XXXVI.

-

[14]

Brossard, 2015, p. 24.

-

[15]

Brossard, 2010, p. 182.

-

[16]

Ibid., p. 48.

-

[17]

Ibid., p. 225.

-

[18]

Perry, 1994, p. 599.

-

[19]

Ibid., p. 587.

-

[20]

Ibid., p. 607.

-

[21]

Gerk Hernandez, p. 268.

-

[22]

Brossard, 2010, p. 34.

-

[23]

Brossard, 2015, p. 142.

-

[24]

Brossard, 2010, p. 184.

-

[25]

Ibid.

-

[26]

Ibid., p. 84

-

[27]

Ibid., p. 86.

-

[28]

Steven Shaviro, Post-Cinematic Affect, Washington, Zero Books, 2010, p. 2.

-

[29]

Ibid.

-

[30]

Ibid., p. 4.

-

[31]

Ibid., p. 2.

-

[32]

Ibid., p. 6.

-

[33]

Simon Dumas, “102”, Les univers parallèles du Mauve motel, 2018, https://mauvemotel.net (accessed 8 December 2022).

-

[34]

Adriene Jenik, MAUVE DESERT: A CD-ROM Translation, Los Angeles, Shifting Horizons Productions, 1997.

-

[35]

Simon Dumas, “103”, Les univers parallèles du Mauve motel, 2018, https://mauvemotel.net (accessed 8 December 2022).

-

[36]

Ibid. Brossard describes the pathway towards the virtual in very poetic, personal terms, as follows: “La représentation, l’image, photo, film, hologramme, la trace, l’image en tête, l’image qui affole, l’image obsédante. L’image-énigme qui porte au-delà du réel : la virtuelle.”

-

[37]

Beverley Curran, “Obsessed by her reading: An interview with Adriene Jenik about her CD-ROM translation of Nicole Brossard’s Le désert mauve,” Links & Letters, vol. 6, 1998, p. 103–104.

-

[38]

Ibid., p. 108.

-

[39]

Bruno Lessard, The Art of Subtraction. Digital Adaptation and the Object Image, Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2017, p. 112.

-

[40]

Brossard, 2010, p. 38.

-

[41]

Case, Sue-Ellen. “Eve’s Apple, or Women’s Narrative Bytes,” Modern Fiction Studies, 43.3 (Fall 1997), p. 632.

-

[42]

Ibid.

-

[43]

Ibid.

-

[44]

Bachand, Denis. « Du roman au cédérom. Le désert mauve de Nicole Brossard », Cinéma et littérature au Québec : rencontres médiatiques, Montréal, XYZ éditeur, 2003, p. 45.

-

[45]

Ibid.

-

[46]

Navigating virtual space as Mélanie can, in fact, be liberating or alienating depending on your subject position, sexuality, and gender identification. The MAUVE DESERT world is, after all, a primarily lesbian environment. Bruno Lessard claims that Jenik’s CD-ROM translation of Brossard’s novel does not go far enough in presenting a critique of gender biases because, rather than being explored, Mélanie’s teenage rebellion is taken as a given. Furthermore, according to Lessard, “the CD-ROM suffers from Mélanie’s occasional absence given that she is not constantly present and seems to have saved the driver’s seat for an unidentified interactor who may be… a man. Having been associated with masculinity and speed for decades, the car in which the interactor sits may lead him to forget that the actual driver is a young woman,” Ibid., p. 128. This poses a curious problem: if we do not see the young girl, we can easily forget that she exists. It also begs the following question: Can Mélanie be virtually or even visually represented without being objectified?

-

[47]

Maria Klonaris and Katerina Thomadaki, “The Feminine, the Hermaphrodite, the Angel: Gender Mutation and Dream Cosmogonies in Multimedia Projection and Installation (1976-1994),” Leonardo, vol. 29, no. 4, 1996, p. 275.

-

[48]

Sidonie Smith, Moving Lives: Twentieth-Century Women’s Travel Writing, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2001, p. 178.

-

[49]

Margaret Morse, “The Poetics of Interactivity,” Women, Art & Technology, Judy Malloy (ed.), Massachusetts, MIT Press, 2003, p. 20.

-

[50]

Curran, 1998, p. 102.

-

[51]

Ibid.

-

[52]

Bachand, 2003, p. 49.

-

[53]

Ibid.

-

[54]

Curran, 1998, p. 107.

-

[55]

Ibid.

-

[56]

Brossard, 2010, p. 90.

-

[57]

See p. 120–123 of Lessard’s chapter on Jenik’s work.

-

[58]

Ibid., p. 123.

-

[59]

N. Katherine Hayles, My Mother Was a Computer: Digital Subjects and Literary Texts, University of Chicago Press, 2005, p. 89.

-

[60]

Lawrence Grossberg, Dancing in Spite of Myself: Essays on Popular Culture, Durham, Duke University Press, 1997, p. 283.

-

[61]

Ibid.

-

[62]

Ibid., p. 151–152.

-

[63]

Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media, Cambridge, Massachusetts, The MIT Press, 2001, p. 61.

-

[64]

Grossberg, 1997, p. 283.

-

[65]

Manovich, 2001, p. 61.

-

[66]

Ibid.

-

[67]

Beverley Curran, “Re-reading the Desert in Hypertranslation,” Style, vol. 33, no. 2, Summer 1999, p. 208.

-

[68]

Brossard, 2010, p. 39.

-

[69]

Hayles, 2005, p. 151.

-

[70]

The website content was compiled and published in a traditional book format in 2022. See Simon Dumas and Nicole Brossard, Géométries du Mauve Motel: correspondance avec Nicole Brossard, Montréal, L’Hexagone, 2022. The implications, gains, and losses of the move from the digital to the paper publication are significant and should be explored in another context.

-

[71]

It is worth noting that Dumas’s website fills a gap in the Désert mauve universe that Denis Bachand first identified in his 2003 analysis of Jenik’s CD-ROM work: “Le prochain pas consisterait à coupler le cédérom à une toile hypermédia pour réaliser ce que Pamini appelle un ‘instrument pour lire’ distinct des ‘produits à lire’ (ou Expanded Books) qui dominent l’édition électronique. L’interacteur bénéficierait alors des ressources documentaires, biographiques, bibliographiques, critiques et autres sollicitées en adjuvants du texte, comme c’est le cas à l’état embryonnaire avec les segments d’entrevue accordée par Nicole Brossard, lesquels exposent sa démarche d’auteure. La lecture s’extensionnerait ainsi aux dimensions d’une bibliothèque virtuelle selon diverses modalités propres à la culture de l’interactivité favorisant à la fois recherche, création et re-création” (Bachand, 2003, p. 54).

-

[72]

Simon Dumas, “Réception”, Les univers parallèles du Mauve motel, 2018, https://mauvemotel.net (accessed 8 December 2022).

-

[73]

Ibid.

-

[74]

Ibid.

-

[75]

Ibid., 13 mai 2010.

-

[76]

Dumas, “103”, 2018.

-

[77]

Dumas, “102”, 2018.

-

[78]

Jen Kennedy, « GirlsGirlsGirls », esse arts + opinions, n° 82 (Spectacle), automne 2014, p. 26.

-

[79]

Tiqqun, Premiers matériaux pour une théorie de la Jeune-Fille, Paris, Mille et une nuits, département de la Librairie Arthème Fayard, p. 21.

-

[80]

Ibid., p. 128.

-

[81]

Dumas, “103”, 2018.

-

[82]

Dumas, “102”, 2018.

-

[83]

Dumas, “103”, 2018.

-

[84]

Brossard, 2010, p. 59.

-

[85]

Ibid., p. 235.

-

[86]

Kaja Silverman, The Threshold of the Visible World, New York, Routledge, 1996, p. 175.

-

[87]

Shaviro, 2010, p. 8–9.

-

[88]

Ibid., p. 9.

-

[89]

Ibid., p. 10.

-

[90]

Chassay, 2010, p. 25–26.

-

[91]

Brossard, 2010, p. 48.

-

[92]

Simon Dumas, “103 ”, 2018.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Figure 4

Figure 5

Screenshot of the website Simon Dumas, Les univers parallèles du Mauve motel, 2018, https://mauvemotel.net/ (accessed 8 December 2022).

Figure 6

Screenshot of the website Simon Dumas, Les univers parallèles du Mauve motel, 2018, https://mauvemotel.net/piscine/ (accessed 8 December 2022).

Figure 7

Screenshot of the website Espacego, 2018, https://espacego.com/les-spectacles/2018-2019/le-desert-mauve/ (accessed 8 December 2022)

Figure 8

Liste des vidéos

Figure 2

Excerpt from Adriene Jenik, MAUVE DESERT: A CD-ROM Translation, Los Angeles, Shifting Horizons Productions, 1997.

Figure 3

Excerpt from Adriene Jenik, MAUVE DESERT: A CD-ROM Translation, Los Angeles, Shifting Horizons Productions, 1997.

Figure 9

Excerpt from the performance of Le désert mauve by Simon Dumas with Nicole Brossard, Production Rhizome, Espace Go, Montreal, September 27–29 2018.

Figure 10

Excerpt from the performance of Le désert mauve by Simon Dumas with Nicole Brossard, Production Rhizome, Espace Go, Montreal, September 27–29 2018.