Résumés

Abstract

This article aims to investigate a relevant but still little-explored function of cadaveric dissection, a medical procedure that in the early modern age offers itself as the most effective tool for unmasking deception and restoring a regime of authenticity and transparency. In this period, anatomy, perceived as capable of revealing layer by layer the physical and spiritual impostures of human nature, proves particularly useful against behavioural practices of simulation and dissimulation, and especially in countering the social phenomenon of religious dis/simulation (also referred to as “hypocrisy” by early moderns). This moralized conception of anatomy underlies two Italian works published at the end of the seventeenth century: the encyclopaedic and anatomical illustrated atlas L’huomo, e sue parti figurato (1684) by Ottavio Scarlattini (1623–1699) and the moral treatise Anatomia degl’Ipocriti (1699) by Dominican Alessandro Tommaso Arcudi (1655–1718). Both symbolically use dissection as a pharmakon to detect and cure hypocrisy in others and in oneself. In Scarlattini’s case, the metaphorical exposition of human interiority through dissection is also visually represented in a substantial iconographic apparatus in which the debate between masquerade and transparency appears polarized in organic sites, such as the heart and the mouth, symbols of truth and fraud, respectively.

Résumé

Cet article vise à étudier une fonction pertinente et encore peu explorée de la dissection cadavérique : une procédure médicale qui au début de l’époque moderne, se présente comme un outil des plus efficaces pour démasquer la tromperie et restaurer ainsi un régime de transparence et d’authenticité. À cette époque, l’anatomie — perçue comme capable de révéler couche par couche les impostures physiques et spirituelles de la nature humaine — s’avère particulièrement utile contre les pratiques comportementales de simulation et de dissimulation, et notamment pour contrer le phénomène social de la dis/simulation religieuse (également appelée "hypocrisie" par les premiers modernes). Cette conception moralisée de l’anatomie est à la base de deux ouvrages italiens publiés à la fin du 17ème siècle : l’atlas encyclopédique et anatomique illustré L'huomo, e sue parti figurato (1684) d’Ottavio Scarlattini (1623-1699) et le traité moral Anatomia degl'Ipocriti (1699) du dominicain Alessandro Tommaso Arcudi (1655-1718). Tous deux utilisent symboliquement la dissection comme un pharmakon qui détecte et guérit l’hypocrisie chez les autres et en soi-même. Chez Scarlattini, l’exposition métaphorique de l’intériorité humaine à travers la dissection est également représentée visuellement à travers une iconographique substantielle, dans laquelle le débat entre la mascarade et la transparence apparaît polarisé sur des endroits du corps, tels que le coeur et la bouche, respectivement symboles de vérité et de fraude.

Corps de l’article

Introduction. “Under the mantle of Religion”

In the same century that exalts dissimulation as a subtle art of social and political survival, cadaveric dissection offers itself as a tool for unmasking deception and as a model of sinceritas. Indeed, grafted onto the seventeenth-century debate between the behavioural practises of simulation and dissimulation,[1] a moralized view of anatomy emerges in which it is seen as a form of inner unveiling that is able to detect the organic and moral arcana of human interiority. The surgical excavation, which allows the invisible subcutaneous to arise, thus opposes the dominant tendency of the mask, a symbol of hypocrisy against the truth. Anatomy, and medicine more generally, is revealed to be particularly effective against a form of dissimilatory practice which affects the most intimate spheres of human beings—the ethical and spiritual ones—and, at the same time, had important consequences on cultural and social life between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries.

“Religious dis/simulation”[2] is a historical macro-category dating back to the origins of Christianity and includes different trends, such as simony, idolatry, Nicodemism,[3] simulated holiness, possession,[4] and devotion—all animating a lively religious debate in the Tridentine ecclesiastical world.[5] In this period, religious and civil authorities try to control these phenomena with bulls, attestations of authenticity, and inquisitorial trials, which branded religious simulation as a form of popular religiosity, superstition, or paganism.[6] In some cases, the Church also resorted to the help of science, specifically, to medical-anatomical evaluations. For example, to contrast the simulated holiness, which usually manifested through altered states of psycho-physical conditions, careful medical examinations of symptoms, entrusted to physicians and surgeons, proved necessary.

The use of medicine as scientific discrimen between true and false is not new; on the contrary, it has an established tradition in Hippocratic and Galenic medical writings. In his work against disease simulators, De optima corporis nostra constitutione […] Quomodo simulantes morbum sunt deprehendendi, the Pergamon physician and surgeon ascribes to physicians the duty of distinguishing real diseases from simulated ones.[7] In the wake of Galen, other early modern physicians, such as Giovan Battista Silvatico (1550–1621) and Paolo Zacchia (1584–1659), published useful medical guides to allow for recognition of false symptoms and the unmasking of deceivers.[8] Zacchia also includes in the category of the simulation of illness those who pretend to be afflicted with diseases “ut nomen sibi sanctimoniae apud homine concilient” (to be worshipped as saints).[9] Relevant in this regard is the case of the ecstasy of a woman “who—when many people gathered in churches and other sacred places—pretended to be rapt in ecstasy”:

She stood with her arms stretched out in the form of a cross, her eyelids motionless, her eyes fixed. [...] During the whole time of the ecstasy she stretched her body in an extraordinary way, as if she was about to fly into the sky and wanted to rise into the air. But the fact that most amazed me was this woman’s ability to change the colour of her face and the stroke of her eye. Indeed, she first blushed and [...] then—more and more paling—she languished without consciousness as if she was dead, finally she regained the vermilion of her cheeks and simulated coming back to herself, so that the onlookers considered her to be in the grip of divine rapture and worshipped her as a saint. [...] I, who knew this person inside and out, could not refrain from laughing, and I am sure that the Sicilian matron was mocking her devotees.[10]

The relationship between the simulation of illness and holiness is particularly evident here. Both use an essentially—even before verbal—somatic language, expressed through symptoms such as pallor, blushing, convulsions, faints, etc.[11] Torquato Accetto even traces the ability to dis/simulate back to a natural and organic predisposition, noting that “those in whom blood or melancholy or phlegm or choleric humor prevails are very indisposed to dissimulate.”[12]

A medical procedure particularly useful for forensic iatrophysics against simulated sanctity was the cadaveric dissection, which had undergone considerable practical and theoretical development since the publishing of Vesalius’ De humani corporis fabrica.[13] Anatomy played, in fact, a central role in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century canonization trials, in which autopsies were performed on saints’ corpses to trace supernatural signs of divine enlightenment and Grace: an enlarged heart, stigmata, or even a perfect state of preservation of the body in old age could be medical evidences of holiness.[14] Although the anatomical explanations of saints’ symptomatology appear, in some cases, anything but scientific, what is extremely relevant is the role assumed by anatomy as a guarantee of the authenticity and “scientificity” of the miracle, no longer attested by faith alone. More generally, dissection in the early modern age proves to be the most suitable tool for investigating human nature and revealing its impostures, by exposing it layer by layer on both physical and spiritual levels.

This idea informs two works written in the late-seventeenth century: the moral treatise Anatomia degl'Ipocriti by the Dominican Alessandro Tommaso Arcudi (1655–1718) and the anatomical illustrated atlas L’huomo, e sue parti figurato, simbolico, anatomico […] by the Lateran canon Ottavio Scarlattini (1623–1699).[15] They have recently been included in a digital collection, titled the Biblioteca anatomica[16] (Anatomical Library), as Italian-area representatives of a literary genre, that of literary anatomies, which assumes the anatomical method as a paradigm of knowledge and interpretation of reality. Although these works have received little scholarly attention, they allow us to reflect on a relevant but still underexplored function of dissection, highlighted only by a few scholars such as Louis Van Delft, who recognizes the genre of literary anatomies as a category for signifying the unmasking of fiction;[17] it attributes to anatomy a spiritual power of inner penetration and inspection and considers it the science of “découverte, dévoilement, démontage, démystification, déconstrution du moi apparent, du moi social, de la persona.”[18]

In their moral anatomies, both Arcudi and Scarlattini metaphorically interpret the depth of the anatomical excavation as a cure against the superficiality of the mask. But while the former plays the role of Momo, “slanderer of the malignant,”[19] detecting hypocrisy in otherness and analysing its social effects, Scarlattini, instead, is more oriented towards a model of dissection as self-examination and cognitio sui. In Scarlattini’s case, the moralized conception of anatomy is also visually conveyed through a substantial apparatus of allegorical images in which the display of internal organs (and in particular the heart) is conceived as the most tangible expression of sincerity. Comparing these two case studies, I will try to understand the mechanisms through which anatomy establishes itself as an art of dis-deception, to what extent Arcudi’s struggle against hypocrisy is affected by the controversy between Dominicans and Jesuits, and how Scarlattini’s iconographic corpus (compared with other sixteenth- and seventeenth-century figurative repertoires) interprets the debate between truth and falsity.

2. Arcudi and the “hypocrites”

The Salentine Father Alessandro Tommaso Arcudi[20] addresses the issue of religious simulation in his Anatomia degl’Ipocriti, a moral treatise that bears witness to the effort of some religious orders in the fight against the sin of “hypocrisy.” This term, which recalls a long literary tradition ranging from the Bible to the works of Fathers, above all St. Jerome and St. Augustine, describes a precise category of religious simulators: the false devotees and saints. Indeed, in his Anatomia, Arcudi carries on a fierce polemic against “modern Pharisees,”[21] generically identified as those who pursue personal interests cloaked in apparent holiness.

The hypocrisy is conceived by Arcudi as a “pestilential fever”[22] or “deadly poison”[23] which only the pharmakon of anatomy can eradicate. As its title suggests, the entire treatise rests in fact on an anatomical metaphor in which the philosopher and theologian Arcudi plays the role of an anatomist: he sets up a dissection hall and prepares himself to undertake a symbolic anatomy of the Church’s body, from which he wants to remove the sick limbs of hypocrisy. In the preface, significantly entitled “Preparamento di ferri” (Preparation of surgical instruments), Arcudi declares that he is inspired by those anatomists who “sharpened their knives [...] to split the dead for the benefit of the living;”[24] then he invites the “Physicians of the Church” to consider the social body in analogy to the organic body and cut or treat diseased parts like “Physicians of the hospitals.”[25]

Since physical decay is directly linked to moral decay, the removal of diseased parts concerns not only the materiality of the body but also the insubstantiality of the soul.[26] According to this moral and theological re-signification of anatomy, it is possible to analyse the principles and mechanisms of dissection in opposition to the strategies of the art of lying. The simulator, in fact, acts underground, covering himself with veils and masks, while the anatomist opens the body’s external casing to offer a clear vision of the interior. Hence, Arcudi’s conception of the anatomist’s work in analogy with that of the sculptor who, “per via di levare” (by taking away), removes layer by layer all the artifices.[27] On the contrary, the hypocrite imitates the painter and, “per via di porre” (by way of putting), adds veils to the truth. Following Buonarroti, who learned anatomy to excel in sculpture, Arcudi uses “shavers” and “scalpels” to dissect the hypocrisy and to “remove the mask from the superficial Holiness.”[28] The surgical excavation is thus seen as an ablative operation capable of ripping the veil of deception both from the body and from the soul.

The anatomical metaphor also reflects on the work’s structure. The Anatomia degl’Ipocriti consists in fact of eighteen chapters, each devoted to a part of the human body and in turn divided into “cuts” designed to “discover the iniquity of the interior.”[29] In each chapter, Arcudi focuses on the features of the hypocrite and provides, in relation to a specific body part, numerous examples of religious simulation. A deep knowledge of the symptomatology of the hypocrisy will, in fact, allow the reader not only to recognize the disease but also to prevent and eradicate it.

The first chapter is devoted to the face, the part of the body which is most affected by outward signs of hypocrisy, a vehicle of acting skills, such as transfiguration, lying, and imitation. To describe the real aspect of the hypocrisy, Arcudi resorts to a whole series of zoological metaphors, symbolically associated with darkness, evil, fraud, and impurity. In particular, the hypocrite is associated to reptiles like the chameleon, for its ability to change and adapt to any situation, and to poisonous species like the scorpion, the viper, and the snake, who flatter and mortify with their teeth or tail; it is also seen as a larva for its devious creeping and nesting underground, as a greedy and insatiable wolf, as a fox for its cunning, as a harpy or apocalyptic animals like locusts for its harmfulness. Among mammals, the closest animal to the hypocrite is the monkey, which imitates man just like the hypocrite tries to resemble saints.[30] The monkey is not only the symbol of deception and fraud but it is also the animal which Galen used as a substitute of man for his dissections.

The ferine nature of the hypocrite is well described and depicted in Cesare Ripa’s Iconology, where the “Hippocresia” (see Fig. 1) appears as a “skinny and pale woman […] with legs and feet similar to those of a wolf,”[31] who holds with her left hand a long crown and a prayer book, while with the right she, publicly, hands a coin to the poor.

Fig. 1

Anon., Hippocresia, woodcut, 105x125 mm, published in Cesare Ripa, Nova iconologia, Padova, Pietro Paolo Tozzi, 1618, p. 233.

The representation of hypocrisy as a woman, dressed in the religious vestments (the rosary, the habit, the veil), reflects an outdated but still relevant tradition which considered the phenomenon of simulated holiness predominantly female, as witnessed by numerous cases of female mystics and saints recorded in convents and religious communities between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries.[32] For Arcudi, women behave like hypocrites, enacting continuous metamorphoses and illusions and flaunting their false virtues with outward signs. With makeup, women disguise their true appearances, similar to how hypocrites pretend the pallor of abstinence and penitence with powders and mixtures;[33] with “ceremonial tears”[34] (lagrime di cerimonie) and sighs women arouse pity and seduce, while hypocrites, with “inflamed tears”[35] (lagrime infervorate), murmur false orations and penances to exhibit their devotion.

Ever since Eve was deceived by the snake, women became guilty of the moral sin of hypocrisy and, at the same time, its victims. Arcudi’s long misogynistic invective aims, in fact, to target their executioners rather than women themselves. The snake which threatens the modern Church is identified with a category of devotion simulators against which Arcudi rails with vehemence: “Modern Masters of Christian Doctrine […] Mercenary Physicians and fallacious Guides,”[36] who sow new dogmas and teach new doctrines out of opportunism. Although the author claims to address “generic hypocrisy”[37] and never targets specific individuals, behind his biting invectives against these spiritual fathers, we can trace a veiled reference to Jesuits, often accused in the early modern age of consorting with women, of hiding ambition and a thirst for power, money, and social recognition under a cloak of apparent holiness.

The Anatomia degl’Ipocriti echoes, in fact, the religious disputes between the Dominicans, Theatines, and Jesuits which animated the entire Counter-Reformation age. Medieval religious orders, such as the Dominicans, fearing the vertiginous rise of the “new orders” and viewing with suspicion the doctrines spread by the Society of Jesus and their charitable activities, carry out a smear campaign that in the eighteenth century sometimes results in outright expulsions of the Jesuits from Italian cities, up until the order was finally suppressed in 1773 by decision of Pope Clement XIV.[38] One of the cornerstones of the construction of European Anti-Jesuitism[39] is the stereotype of the Jesuit as hypocrite, so deep-rooted that even today dictionaries consider these words as synonyms.

A work that stigmatises the Jesuits is La pietà trionfante[40] by the Theatine Guarino Guarini, a moral tragicomedy which reflects the religious struggles and the hostility between Clerks Regular and Jesuits at the court of the Dukes of Este. Guarini’s source is the famous work Le triomphe de la pieté or L’impieté domptée, written by the Jesuit Nicolas Caussin and focused on the conversion of King Clodoardo of Denmark and his sons to Christianity. Although the work is set during the Carolingian religious wars, it is possible to trace some references to political and religious issues contemporary to the author. For example, behind the constant deceptions hatched by the priests of Mars and the betrayals of the vestal virgins, hides a clear reference to modern religious orders. Guarini probably refers to the Jesuits in an invective in which he accuses the priests to be “hypocrite ghosts/true destroyers of princes and kings.”[41] The centrality of the Jesuits in modern courts, especially in the role of sovereign’s confessors, spread the fear that they could influence the political decisions of the ruler and threatened peace.[42]

Another point at the heart of Italian anti-Jesuitism concerns, in fact, the great importance attributed by the Jesuits to the institution of sacramental confession, considered by Arcudi as the instrument through which the false spiritual guidance spreads its duperies.[43] The relationship between confessor and false worshipper is criticized at several points in the work. Arcudi polemises against the docility of the confessor, who illudes the sinner to obtain grace “without penances and mortifications of the flesh,” but “just with external devotion and frequency of the Sacraments.”[44] This leads to a weakening of the Christian precepts and a distancing of the faith from the harsher devotional practises. In the Renaissance, the Jesuits were accused of having promoted a new trend of holiness, different from that of antiquity and no longer based on martyrdom but on outward practices and supernatural signs (such as stigmata, visions, or mystical crises).[45] Modern saints are in fact thaumaturges, mystics, anchorites, and penitents, mainly gathered around the order of the Society of Jesus.

By taking radical and antinomian positions against the Modern spirituals’ dominant attitude of tolerance, Arcudi also opposes the Ignatian doctrine of “cases of conscience”[46] according to which the state of souls should no longer be considered from a polarised perspective of good and evil but each case evaluated individually. Religion, therefore, approaches souls in the same way as modern medicine approaches bodies: by processing anamnesis for the individual person.[47] Due to his Catholic rigorism, Arcudi instead is unable to mitigate contradictions and capture the grey shades of consciousness. This sharp stance reflects on his entire work, which is based on a dichotomous vision of reality in which transparency and masquerade, light and darkness, good and evil oppose. The first image appearing in the text is in fact that of light, symbolically associated with the author’s pseudonym, Candido Malasorte Ussaro, anagram of his name and epitome of clarity and sincerity. The author thus presents himself as a model of candour against the opacity of his enemies, who live in darkness like Jesuits in their black cloaks.

3. The metaphor of “sinceritas” in L’huomo, e sue parti figurato

Although Ottavio Scarlattini’s anatomical treatise does not directly address the issue of simulated devotion as Arcudi’s does, responding more to moral rather than polemical intentions, the theme of veritas and dis/simulatio is also a core topic in L’huomo, e sue parti figurato, as evidenced by its author’s clear position on simulation, “abhorred” and “detested” as “the most condemnable vice.”[48]

The Bolognese Lateran canon and Archpriest of the Church of S. Maria Maggiore in Castel S. Pietro Terme shares in fact with the Dominican Arcudi a censorious and condemning attitude towards hypocrisy, a motif recurring in his entire literary production.[49] As Scarlattini himself reports, he has diffusely addressed the issue of hypocrisy in a previous work.[50] He probably refers to Saeculum Momi, hoc est; in corruptos saeculi mores et animi passiones,[51] in which—inspired by the mythological figure of Momo—he polemically inveighs against a century depraved by vices. In 1677, Scarlattini also publishes Del Davide musico armato, in which he presents David as an example of an excellent secular and ecclesiastical prince in opposition to those who, following Machiavelli’s political precepts, adopt hypocrisy as a “Teacher of State” and cover simulation “under the mantle of Religion.”[52]

The issue of simulation, hypocrisy, and duplicity is also present —though not central— in L’huomo, e sue parti figurato, which adopts—as Arcudi’s—the anatomy as a structural criterion and heuristic model for scrutinizing the most intimate—and therefore most authentic—part of man.[53] In this magniloquent summa, which encapsulates the complexity of man through myths, stories, symbols, simulacra, proverbs, and emblems, the anatomy of the body is used as a fil-rouge to link every field of human knowledge. The anatomical pattern especially arises from the dense iconographic apparatus which accompanies the first volume of the work, based on the Galenic model of resolution.[54] It consists of 41 illustrations (including emblems, imprese, and hieroglyphics), realized by the engraver and illustrator Domenico Maria Bonaveri, which visually reproduce the dissection process. Each illustration represents a different body part, which is first anatomically described and then associated with moral and spiritual meanings. Scarlattini in fact conceives the body as a topography of good and evil, where each limb is assumed to be a symbol of vices and virtues, of sin and holiness.

According to such a moralized view of the body, the debate between masquerade and transparency can also be polarized into two organic sites: the mouth and the heart. While the former is the locus of deception and fraud, the heart, on the contrary, is the organ which always speaks the truth. Scarlattini, in fact, describes it as the “most perfect of Simulacra,” located at the center of the “little Sun of the Microcosm.”[55] The position of the heart, enveloped by the pericardium and hidden within the thoracic cavity, is particularly significant and lends itself to a range of metaphorical instrumentalizations in the Baroque age. Accetto, for example, justified the behaviour of the dissimulator as a form of adaptation of human actions to the heart’s natural condition.[56]

If the concealment of the heart is associated with acting and deception, the most efficient way to reveal man’s real intentions and restore the truth is its extraction from the natural seat. To the heart en abyme, Scarlattini thus opposes the image of a “little window opened on the chest,”[57] an incredible invention attributed to Momo by Leon Battista Alberti.

Scarlattini includes in his corpus a significant variant of the windowed heart: an emblem which he retrieves from the famous repertoire of hieroglyphics by Pierio Valeriano.[58] It represents a man with a heart hanging around the neck, and as the motto “Intus et extra idem” suggests, it symbolizes the correspondence between actions and words, appearance and feelings (see Fig. 2).[59] The display of the heart becomes therefore in this period the most tangible expression of sincerity, a virtue that in Ripa’s Iconology appears as a beautiful girl clutching a dove in her right hand and a heart in her left.[60]

Fig. 2

Domenico Bonaveri, Intus et extra idem, engraving, 155x110, published in Ottavio Scarlattini, L’huomo, e sue parti figurato […], Bologna, Monti, 1684, p. 323

The topos of the windowed heart, which had a great literary and iconographic fortune in the Renaissance, soon becomes a metaphor of the anatomical dissection.[61] In the Orazione, written by the physician Jacopo Grandi for the inauguration of the anatomical theater in Venice, the surgeon is the one who opens a window on man’s chest to gaze at the inside of the body but also to “introduce the Sun of Truth into the intellect, and to illuminate the dark Heart of Men with the splendor of Virtue.”[62]

Analogous ability has the theologian, a figure that a widespread Christianised conception of anatomy imagines superimposed on that of the surgeon, as in the work of the Cremonese physician Lorenzo Legati, Scarlattini’s close friend and his medical source.[63] Legati considers the surgical excavation of “the most beautiful simulacrum of Nature” as a form of praise to God which can transform “the Anatomist […] into a Theologian.”[64] In the Sermon V of his Prediche quaresimali, the Barnabite Romolo Marchelli even compares the figure of Christ in the Last Judgment to an “expert Anatomist” who scrutinizes sins in the “marrows.”[65]

The prerogative of peering inside the human body is thus no longer attributed only to God but also to the anatomist who, in cutting through the flesh, manages to reach the deepest places of the spirit. In Francesco Pona’s Cardiomorphoseos (1645), the hand of the surgeon works as God’s omniscient gaze, as can be seen in some emblems representing the Divine Love (Divus Amor) as a physician holding the scalpel and dissecting the heart (see Fig. 3).[66] On the basis of such homology, L’huomo, e sue parti figurato symbolically opens with a human sacrifice in which Scarlattini represents himself as a new Abraham ready to sever with a “Knife, no less Physical, than Moral”[67] a “Man,” his literary creature and metaphorically the human body.

Fig. 3

Anon., Scrutator Es Tu, engraving, 217x155, published in Francesco Pona, Cardiomorphoseos, Verona, Bartolomeo Merlo, 1645, p. 13.

The anatomical supremacy of the heart, demonstrated by Harvey in 1628 with the publication of his study on blood circulation, also reflects on its moral and spiritual centrality.[68] The heart is in fact deputed by moderns to guard the soul as mirror of its deepest feelings. Scarlattini, in the “Miracles” section of the chapter, even identifies it as seat of holiness, recalling all the signs that the Heavenly Omnipotence usually left on it, including a “figure of himself” or “most divine Wounds,”[69] as it happened for the hermitess Chiara of Montefalco in whose heart the image of Christ crucified was impressed or for St. Ignatius the Martyr in whose heart the name of Christ was engraved in golden letters.

While the heart is seen as the origin of all virtues, such as truth, courage, fortitude (see the emblem Signa fortium), judgment, faith, etc., the mouth, on the contrary, has a bifid nature since it can “express at will the feelings of the Heart” or “conceal them.”[70] The mouth is in fact an instrument which can easily turn to good, as in the hands of the preacher who uses it to transmit the divine word, or to evil, as in the case of the hypocrite who “hides evil under the Tongue.”[71] For this reason, it can be the organ closer to God or, as “deceiving tongue,”[72] closer to the Devil, who first, in the guise of a snake, deceived Adam and Eve. On this aspect, Arcudi’s position is even harsher: he in fact recognizes the mouth as the organ in which deception is produced and associates it with a series of “diseases,” such as murmuring, lying, word-pumping, and flattery.[73] According to Medieval classifications of sins, these are the most punishable ones because they are generated through the perversion of the faculties of language, God’s gift to mankind.

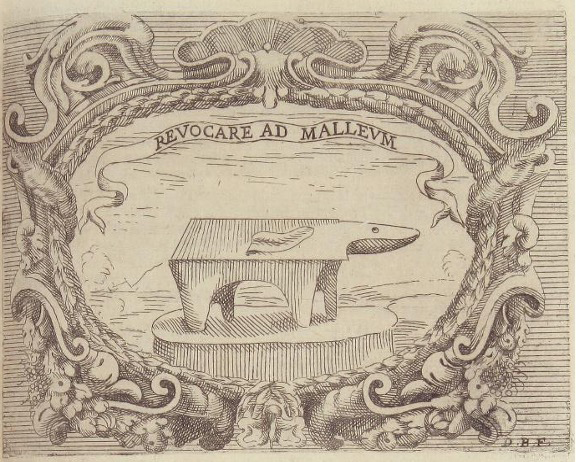

The immoral use of the mouth also determines its physical decay, especially affecting the tongue’s organic consistency. In the emblem Revocare ad malleum (see Fig. 4), representing a tongue placed on an anvil, Scarlattini describes in fact the tongue of Truth as “uncompromising, inflexible, and stable” while that of Lies is “soft, lubricious, and fugitive.”[74] To restore its hardness, Scarlattini provides a series of exempla in which the use of the tongue is combined with other body parts such as the heart and the hand. Bringing the heart closer to the lips or speaking with the heart in the hand are signs which distinguish “the respectable Man, who accommodates the fact with the Word and says what he feels.”[75]

The author also invites the reader to an “ocular” use of words and introduces, alongside the two images of the mouth and heart, that of the eyes, considered by Arcudi as “interpreters of the heart.”[76] The association of mouth and eye, which enables man to fully master the art of speech and make proper use of it, is particularly relevant in the emblem of the Eloquentia verax (see Fig. 5) in which the two organs are represented together to imply that truthful speaking moves from the visual perception of things: only after the eye “foresees things, avoids bad things, follows good things,” the tongue can “properly report its senses”[77] without lies and alterations. A similar idea is expressed in the emblem Dilucidus sermo (see Fig. 6) where an eye injected with blood towers above a tongue, signifying the control it has over the faculties of language and over all the limbs, such as God or a prince rule over the world and the state.

Fig. 4

Domenico Bonaveri, Revocare ad malleum, engraving, 155x110, published in Ottavio Scarlattini, L’huomo, e sue parti figurato […], Bologna, Monti, 1684, p. 181.

Fig. 5

Domenico Bonaveri, Eloquentia verax, engraving, 155x110, published in Ottavio Scarlattini, L’huomo, e sue parti figurato […], Bologna, Monti, 1684, p. 178.

Fig 6

Domenico Bonaveri, Dilucidus sermo, engraving, 155x110, published in Ottavio Scarlattini, L’huomo, e sue parti figurato […], Bologna, Monti, 1684, p. 81.

The eye takes prominence in Scarlattini’s work as a symbol of the relevance of vision in anatomical investigation and imagery of anatomy as introspection and self-knowledge. The anatomical observatio, defined by Grandi as the “eye of Medicine,”[78] is in fact fundamental in the detection and treatment of physical diseases, but it is also seen as inner eye, capable of overcoming the opacity of the body and exposing moral diseases and turpitudes of the soul.

Conclusion. The anatomy as mirror

In the domain of masks and shadowy existences, the practise of dissection thus appears as the most efficient tool through which a regime of authenticity and transparency can be restored. One of the most recurrent symbols in the seventeenth century related to the idea of anatomy as ars revelandi is in fact the mirror, an object which significantly appears on the frontispieces of many anatomical treatises, as in Giulio Casseri’s Tabulae anatomicae where the allegory of anatomy is depicted as an elderly woman holding a mirror in her right hand and a skull in her left.[79] The mirror is repeatedly evoked also in Arcudi’s and Scarlattini’s moral anatomies. In the preface of the Anatomia degl’Ipocriti, Arcudi defines his work as a “Mirror to redemption”[80] of hypocrites and uses it as a kind of Perseus shield against them. The treatise closes on an apocalyptic image: on the day of the Universal judgment, God will place a mirror before the hypocrite, who like the Basilisk will petrify himself.

Slightly different is the role of the mirror in L’huomo, e sue parti figurato, where it is conceived as one of the most powerful expression of nosce te ipsum. Scarlattini does not use the anatomist’s ability of looking beyond the mere external semblance as a weapon to wield against vices but to unveil the self-deceptions and direct the consciousness to good. The iconographic apparatus, especially, which establishes itself as a manual of sincerity, is offered by Scarlattini as a “terse mirror”[81]—a faithful and encompassing portrait of the Microcosm— in which the reader, and the author as well, can reflect and know himself.

In the Baroque age, the transparency of the body becomes therefore the cipher of moral integrity.[82] A relevant example in this regard is one of the most famous Novelas ejemplares of Miguel de Cervantes. The protagonist of the tale is a young lawyer, Tomás Rodaja, nicknamed “Doctor Glass”[83] after a spell—cast by a lady—convinced him that his body was made of glass. The perception that he has of his fragile and subtle constitution determines a change in his behaviour, and from then on, he becomes more sensible, wiser, and oriented towards the truth and the unmasking of fictions; indeed, faced with the glass, all lies, illusions, self-deceptions, and masks collapse.

Parties annexes

Biographical note

Imma Iaccarino studied Modern Philology at the University of Naples “Federico II” and Études littéraires at the Université de Lille. She graduated with a thesis in Comparative Modern Literatures entitled The vertigo of the abyme. Genesis and evolutions of the mirror narrative between literature and cinema. She is currently an assistant (Cultore della materia) in Comparative Modern Literatures and Inter artes Studies at the University of Naples “Federico II” and a Ph.D. student-assistant at the University of Italian Switzerland (USI Lugano) where she takes part in the project The “Civilization of Anatomy”: the genre of literary anatomies in Seventeenth-century Italy (SNSF project, coordinated by Linda Bisello).

Notes

-

[1]

On simulation and dissimulation as social and political strategies: Torquato Accetto, Della dissimulazione onesta [1641], Salvatore Silvano Nigro (ed.), Turin, Einaudi, 1997; Baltasar Gracián, Oracolo manuale e arte della prudenza [1647], Eugenio Mele (trans. and ed.), Bari, Laterza, 1927; Giulio Mazzarino, Breviario dei politici [1684], Milan, Luni Editrice, 2022; Rosario Villari, Elogio della dissimulazione. La lotta politica nel Seicento, Bari, Laterza, 1987; Remo Bodei, Geometria delle passioni. Paura, speranza, felicità: filosofia e uso politico, Milan, Feltrinelli, 2000, p. 144–155; Linda Bisello, Sotto il “manto” del silenzio: storia e forme del tacere (secoli XVI-XVII), Florence, Olschki, 2003; Umberto Eco, “Dire il falso, mentire, falsificare,” in Id., Sulle spalle dei giganti, Milan, La nave di Teseo, 2017, p. 247–284.

-

[2]

See Gabriella Zarri (ed.), Finzione e santità tra medioevo ed età moderna, Turin, Rosenberg & Sellier, 1991.

-

[3]

Carlo Ginzburg, Il Nicodemismo. Simulazione e dissimulazione religiosa nell'Europa del ‘500, Turin, Einaudi, 1970.

-

[4]

Federico Barbierato, “Il ‘peso della religione’ e le possedute felici. Storia di Girolamo Rossi e delle monache di Santa Giustina (1665–1673),” Giuliana Ancona and Dario Visintin (eds.), Omaggio ad Andrea Del Col. Venezia e il Friuli. La fede e la repressione del dissenso, Montereale Valcellina, Circolo Culturale Menocchio, 2013, p. 157–190.

-

[5]

For a historiographical reconstruction of the Counter-Reformation debate on simulated holiness see Adriano Prosperi, L’elemento storico nelle polemiche sulla santità, Turin, Resenberg & Sellier, coll. “Sacro/Santo,” 1991, p. 88–118; Adriano Prosperi, “Santità vera e falsa,” Tribunali della coscienza. Inquisitori, confessori, missionari, Turin, Einaudi, 1996, p. 431–464.

-

[6]

Paola Zito, Giulia e l'inquisitore. Simulazione di santità e misticismo nella Napoli di primo Seicento, Naples, Arte Tipografica, 2000.

-

[7]

Galeno, De optima corporis nostra constitutione […] Quomodo simulantes morbum sunt deprehendi, Autun, 1578, p. 63.

-

[8]

Giovan Battista Silvatico, De iis qui morbum simulant deprehendendis, Milan, Eredi di Pacifico da Ponti, 1595; Paolo Zacchia, Quaestionum medico-legalium tomi tres, Frankfurt, Sumptibus Joannis Baptistae Schönwetteri, 1666.

-

[9]

Zacchia, 1666, p. 243.

-

[10]

“Vidi ego mulierem mihi satis notam, quae se, ubi frequens hominum coetus in templis, sacrisque locis convenisset, raptam in Estasim effingebat, & admiratione non parva dignum erat, quàm aptè simularet. Stabat extensis brachiis in Crucis modum, palpebris immobilibus, oculis fixis […] Interdum veluti ad coelum volatura, & in aerem se elevatura corpus attollebat, illud mirum in modum extendens; sed admirationem omnem superare mihi visum est, quod vultum in mille colores vel ictu oculi commutaret; nam modo rubescebat […] modò adeò pallescebat, ut quasi emortua langueret, denuò, ac dicto citius, rubore perfundebatur, ac denique veluti animo deficiens ad seipsam redire simulabat, ita ut circumstantes omnes eam divino raptu prehensam pro sancta venerarentur […] Non sine mei ipsius risu, & multo majori, ut credo, ispsiusmet foeminae derisu, quam ego quidem intus & in cute agnoscebam; erat autem Sicula,” ibid., Lib. III, tit. II, quaestio VI, p. 254 (our translation).

-

[11]

Alessandro Pastore, Le regole dei corpi. Medicina e disciplina nell’Italia moderna, Bologna, il Mulino, 2006, p. 63–84; Valerio Marchetti, “La rappresentazione cinquecentesca della follia: una biblioteca senza archivio,” Mario Galzigna (ed.), La follia, la norma, l’archivio. Prospettive storiografiche e orientamenti archivistici, Venice, Marsilio, 1984, p. 135–169.

-

[12]

“Quelli in chi prevale il sangue o la malinconia o la flemma o l’umor collerico, è molto indisposto a dissimulare,” Accetto, 1997, p. 23 (our translation).

-

[13]

Andreas Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica libri septem, Basel, Johannes Oporinus, 1543.

-

[14]

About the autopsies of Carlo Borromeo (1584) and Filippo Neri (1595) see Nancy Siraisi, “La comunicazione del sapere anatomico ai confini tra diritto e agiografia: due casi del sec. XVI,” Massimo Galluzzi, Gianni Micheli, Maria Teresa Monti (eds.), Le forme della comunicazione scientifica, Milan, FrancoAngeli, 1998, p. 419–438.

-

[15]

Alessandro Tommaso Arcudi [under the pseud. Candido Malasorte Ussaro], L’anatomia degl’Ipocriti, Venice, Girolamo Albrizzi, 1699; Ottavio Scarlattini, L’huomo, e sue parti figurato […], Bologna, Giacomo Monti, 1684.

-

[16]

Linda Bisello, Imma Iaccarino and Margherita Schellino, “La ‘Biblioteca anatomica’ (1552–1699): consistenza e ragioni di un corpus,” Museo Galileo, https://www.museogalileo.it/it/biblioteca-e-istituto-di-ricerca/biblioteca-digitale/collezioni-tematiche/2417-la-civilta-dell-anatomia-il-genere-delle-anatomie-letterarie-nell-italia-del-seicento.html (accessed 24 February 2023).

-

[17]

Louis Van Delft, “L’anatomie morale,” in Id., Littérature et anthropologie, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1993, p. 217–255.

-

[18]

Ibid., p. 252.

-

[19]

“Momo calunniatore per gli maligni,” Arcudi, 1699, p. 25 (our translation).

-

[20]

On Arcudi’s biographical information see Alfredo di Napoli, “Gli ‘Ipocriti’ di Candido Malasorte Ussaro. La polemica anti gesuitica di Alessandro Tommaso Arcudi (1699),” Mario Spedicato (ed.), ‘Tutti contro uno’. Alessandro Tommaso Arcudi nel terzo centenario della morte, Castiglione di Lecce, Giorgiani, 2019, p. 236–264.

-

[21]

“Illustriss. e Reverendiss,” Arcudi,1699, c. *r.

-

[22]

Ibid., p. 2.

-

[23]

Ibid., p. 410.

-

[24]

“[Gli anatomisti] affilarono i ferri […] per spaccare gli morti a beneficio de’ vivi, spiando dove si annidasse la malignità de’morbi: e ciò per registrare co’ medicamenti le parti sconcertate,” ibid., p. 2 (our translation).

-

[25]

Ibid., p. 600.

-

[26]

Ibid., p. 2. On the overlap between the “anatomy of the body” and the “anatomy of the soul” see Mino Bergamo, L’anatomia dell’anima, Da François de Sales a Fénelon, Bologna, Il Mulino, 1991; Linda Bisello, “‘Intus et extra idem’: l’anatomia morale nella letteratura italiana moderna,” Lettere Italiane, LXVIII, no. 1, 2016, p. 3–41.

-

[27]

On the theme of the ablative art see Michelangelo Buonarroti, Rime, Paolo Zaja (ed.), Milan, Rizzoli, 2010, p. 151–152; but also Giuseppe Allegro e Guglielmo Russino (trans. and ed.), Tenebra luminosissima. Commento alla “teologia mistica” di Dionigi Aeropagita, Palermo, Officina di Studi medievali, 2007 about the Mystica theologia of Dionysius Aeropagita, who applied the principles of the “art of removing” to apophatic or negative mysticism, founded on the ablatio alteritatis, the elimination of all distractions from the divine and mystical union.

-

[28]

“Toglierò la maschera alla Santità superficiale,” Arcudi, 1699, p. 2.

-

[29]

Ibid., p. 2. The work is divided into: (I) Face, (II) Head, (III) Hair, (IV) Eyes, (V) Nose, (VI) Forehead, (VII) Brain, (VIII) Tongue, (IX) Neck, (X) Breasts, (XI) Hand, (XII) Shoulders, (XIII) Stomach, (XIV) Navel, (XV) Skin, (XVI) Bowel, (XVII) Gall, (XVIII) Heart.

-

[30]

Ibid., p. 137–139.

-

[31]

“Donna magra, & pallida, […] haverà in capo un velo, che le cuopra quasi tutta la fronte; terrà con la sinistra mano una grossa, & lunga corona, & un’offitiuolo, / con la destra mano, con il braccio scoperto porgerà in atto pubblico una moneta ad un povero, haverà le gambe, & li piedi simile al lupo,” Cesare Ripa, Nova iconologia, Padova, Pietro Paolo Tozzi, 1618, p. 233, (our translation).

-

[32]

Jean-Michel Sallmann, “Esiste una falsa santità maschile?,” Zarri, 1990, p. 119–128.

-

[33]

“Gl’Ipocriti colla pallidezza artificiosa, le Donne co’gli colori mendicati s’ingegnano rapir pupille matematiche del loro sembiante, e si lasciano rapir dall’aure ambiziose”, Arcudi, 1699, p. 75 (our translation).

-

[34]

“Mi par di veder quelle Donne scarmigliarsi coll’unghie le chiome sciolte, gettando i velli sopra l’imagine profana, e fare a gara chi meglio sapesse fingere gli lamenti […] Per dirla io non posso capire, e stordisco considerando che si trovano lagrime senza dolore, e che si pianga per ingannare, e pure lo vediamo coll’esperienza, ed è l’Abecedario che nella scola dell’Ipocrisia imparano primieramente le Donne,” ibid., p. 267 (our translation).

-

[35]

Ibid., p. 264.

-

[36]

“Dottori mercenarij, ed Guide fallaci, che per stabilire i loro interessi, per accattivarsi la protezione de’ Grandi, per affazionarsi le Dame, è sovvertir feminelle, spianano con novelle opinioni la strada del Cielo; e prometono di condurre gli Fedeli in carrozza fra morbidezze di fiori,” ibid., p. 599 (our translation).

-

[37]

Ibid., p. 5.

-

[38]

Alfredo di Napoli, “L’antigesuitismo napoletano e riverberi in Salento nel secondo Settecento,” Pasquale Corsi (ed.), Atti dell’Incontro di Studio Carlo di Borbone e la “stretta via del riformismo” in Puglia, Bari, Società di Storia Patria per la Puglia, 2019, p. 309–330.

-

[39]

Pierre-Antoine Fabre and Catherine Maire (dirs.), Les Antijésuites. Discours, figures et lieux de l’antijésuitisme à l’époque moderne, Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2010.

-

[40]

Guarino Guarini, La Pietà Trionfante, tragicomedia morale di D. Guarino Guarini modonese, cl. reg., Messina, Stampa di Giacomo Mattei, 1660.

-

[41]

“Ipocrite fantasme/di Prencipi e di Regi veri devastatori,” Guarini, 1660, I, vii, 46–57, p. 44–45.

-

[42]

Claire Ravez, “Mythe(s) et histoire(s). La réception protestante du tumulte de Torun,” Fabre and Maire, 2010, p. 478.

-

[43]

On the relevance of the confession in the Jesuits evangelization strategy see Prosperi, 1996, p. 485–507.

-

[44]

“Sono comparsi ne la Chiesa di Dio alcuni Maestri di Spirito, che hanno inventato una nuova moda di Santità, promettendo di guidar l’anime sicuramente senza penitenze, è mortificazioni della carne, colla sola devozione esterna, è frequenza de’ Sagramenti,” Arcudi, 1699, p. 600.

-

[45]

About the enlightenment and contemplative nature of Jesuits doctrine see Gianvittorio Signorotto, “Gesuiti, carismatici e beate nella Milano del primo Seicento,” Zarri, 1990, p. 177–201.

-

[46]

Jean-Pascal Gay, Morales en conflit. Théologie et polémique au Grand Siècle (1640-1700), Paris, Les éditions du Cerf, 2011, p. 519–550.

-

[47]

At this juncture the figure of the “confessor-physician” was born. Prosperi, 1996, p. 495.

-

[48]

Scarlattini, 1684, p. 275.

-

[49]

Scant biographical information on Scarlattini can be read in Giovanni Fantuzzi, Notizie degli scrittori bolognesi, Bologna, Stamperia di S. Tommaso D’Aquino, 1789, vol. VII, p. 356. Fantuzzi notes that the archpriest was actively involved in the cultural life of his time, as evidenced by his membership in numerous humanistic academies: Scarlattini was enrolled, in fact, in the Accademia degli Innominati in Medicina, in the Accademia degli Intrepidi in Ferrara, in the Accademia degli Inabili in Bologna (with the name “L’informe”) and, from 1682 onwards, in the famous Bolognese Accademia dei Gelati (known as “Il trattenuto”), where he probably came into contact with important physicians and anatomists, such as Lorenzo Legati and Ovidio Montalbani. Archival research aimed at illuminating Scarlattini’s personality, his fields of interest, and his relations with the Bolognese medical milieu is still ongoing by the author.

-

[50]

Ibid., p. 159.

-

[51]

Ottavio Scarlattini, Saeculum Momi, hoc est; in corruptos saeculi mores et animi passiones, Bologna, Giacomo Monti, 1667.

-

[52]

Ottavio Scarlattini, Del Davide musico armato. Idea dell’ottimo prencipe ecclesiastico, e secolare, Bologna, Gioseffo Longhi, 1677, p. 332–333.

-

[53]

Bisello, 2016, p. 8–9.

-

[54]

According to this model the body is vertically dissected from the head to toe. Domenico Laurenza, La ricerca dell’armonia. Rappresentazioni anatomiche nel Rinascimento, Firenze, Olschki, 2003, p. 15–30.

-

[55]

“Giungo nella mia Navigazione per l’Alto Mare delle Parti Umane al più famoso de Lidi, alla più rinomata delle Regioni, al più sublime delle meraviglie, al più perfetto de Simolacri,” Scarlattini, 1684, p. 320.

-

[56]

Accetto, 1997, p. 59.

-

[57]

Scarlattini, 1684, p. 323; Leon Battista Alberti, Momo o del principe [1447?], Rino Consolo (trans. and ed.), Genova, Costa & Nolan, 1992, p. 311.

-

[58]

Pierio Valeriano, Hieroglyphica sive de sacris Aegyptiorum literis commentarii, Basel, Michael Isengrin, 1556, c. R3v.

-

[59]

Scarlattini, 1684, p. 323.

-

[60]

Ripa, 1618, p. 478.

-

[61]

Mario Andrea Rigoni, “Una finestra aperta sul cuore (Note sulla metaforica della ‘Sinceritas’ nella tradizione occidentale),” Lettere Italiane, XXVI, no. 4, October–December 1974, p. 434–458.

-

[62]

“Introdurre il Sole della Verità nell’intelletto, e d’illuminare il tenebroso Cuore degli Huomini con lo splendore della Virtù,” Iacopo Grandi, Orazione detta da Giacopo Grandi publico anatomico nell’aprirsi il nuovo Teatro di Anatomia di Venezia, Venice, Andrea Giuliani, 1671, p. 15.

-

[63]

Giovanni Fantuzzi, Notizie degli scrittori bolognesi, Bologna, Stamperia di S. Tommaso D’Aquino, 1794, IX, p. 9.

-

[64]

Lorenzo Legati, Museo Cospiano: annesso a quello del famoso Ulisse Aldrovandi e donato alla sua patria dall’illustrissimo Signor Ferdinando Cospi, Bologna, Giacomo Monti, 1677, p. 1.

-

[65]

Romolo Marchelli, Prediche quaresimali, Venezia, Storti, 1682, p. 55.

-

[66]

Francesco Pona, Cardiomorphoseos sive ex corde desumpta emblemata sacra, Verona, Bartolomeo Merlo, 1645, VII, LXXXIII, p. 13, p. 169.

-

[67]

Scarlattini, 1684, p. 322.

-

[68]

William Harvey, Exercitatio Anatomica De motu cordis et sanguinis in animalibus [1628], Chauncey D. Leake, Springfield-Baltimore and Charles. C. Thomas (eds.), 1928.

-

[69]

Scarlattini, 1684, p. 332. See also the panegyric of the friar preacher Raffaele Maria Filamondo, La Notomia del cuore, Palermo, Giacomo Epiro, 1688 where the heart takes the seat—later confirmed by autopsy—of Filippo Neri’s sanctity, who justified his frequent palpitations as the exorbitant outpouring of the Holy Spirit.

-

[70]

The mouth is defined “Bocca di Dio” or “Bocca del Cuore” when associated to the functions of the Holy predication, Scarlattini, 1684, p. 161–162.

-

[71]

Ibid., p. 183.

-

[72]

Ibid.

-

[73]

Arcudi, 1699, p. 499–533; about lies see also Camillo Baldi, Delle mentite et offese di parole come possino accomodarsi, Bologna, Thedoro Mascheroni and Clemente Ferroni, 1623.

-

[74]

“Per dimostrare l’inflessibile, e fermo della Verità, Pindaro, quel gran Principe della Lirica Greca, sopra un’Incudine fece vedere una Lingua di ferro con la qual Lingua diceva, che favellava Apolline Pitio sempre inconcusso, inflessibile, e stabile […] Si finge di questo Metallo duro, essendo di Diametro opposta alla Bugia, molle, lubrica e fuggitiva,” Scarlattini, 1684, p. 180.

-

[75]

“Appresso pure ad Horo Apolline, allo scrivere del Causino, si ritrova espressa questa figura, cioè d’uno, che si mette con la Mano destra il Cuore alla Bocca; si accenna, dice il citato, perciò l’integrità, e realtà d’un Huomo da bene, che accomoda il fatto con la Parola, dice quello, che sente”, ibid., p. 160.

-

[76]

Arcudi, 1699, p. 247.

-

[77]

“Così Urbano dell’Occhio alla Lingua soggetto intende la dilucidata perfettion del discorso; come, che questo antivede le cose, vieta le cattive, siegue le buone, così deve la Mente antiveder con l’Occhio della Consideratione le cose, e proferirne adequatamente i suoi Sensi, e perche la parola da se medema poco valerebbe, vi aggiungon la Mano, che denota l’Operatione, che deve proseguire il detto,” Scarlattini, 1684, p. 177.

-

[78]

Grandi, 1671, p. 21.

-

[79]

Giulio Cesare Casseri, Tabulae anatomicae [1627], Frankfurt, Mattheus Merian, 1632.

-

[80]

“Illustriss. e Reverendiss,” Arcudi, 1699, c. *1r.

-

[81]

Scarlattini, 1684, p. 5.

-

[82]

Chakè Matossian, “Le corps de verre: métaphysique de l’anatomie,” Victor Stoichita (dir.), Le corps transparent, Rome, L’Erma di Bretschneider, 2013, p. 109–124.

-

[83]

Miguel de Cervantes, Novelle esemplari [1613], Pier Luigi Crovetto (trans. and ed.), Turin, Einaudi, 2002, p. 243.

Liste des figures

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Domenico Bonaveri, Intus et extra idem, engraving, 155x110, published in Ottavio Scarlattini, L’huomo, e sue parti figurato […], Bologna, Monti, 1684, p. 323

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Domenico Bonaveri, Revocare ad malleum, engraving, 155x110, published in Ottavio Scarlattini, L’huomo, e sue parti figurato […], Bologna, Monti, 1684, p. 181.

Fig. 5

Domenico Bonaveri, Eloquentia verax, engraving, 155x110, published in Ottavio Scarlattini, L’huomo, e sue parti figurato […], Bologna, Monti, 1684, p. 178.

Fig 6

Domenico Bonaveri, Dilucidus sermo, engraving, 155x110, published in Ottavio Scarlattini, L’huomo, e sue parti figurato […], Bologna, Monti, 1684, p. 81.