Résumés

Abstract

Brazilian musicians Milton Nascimento and Nivaldo Ornelas began working together in the 1960s in Belo Horizonte. This was a decade of great transformations for global geopolitics as well as Brazilian society, which was undergoing a rapid growth of urban centers coupled with rural outmigration. During this period, two fields of cultural production emerged in popular music that would become paradigmatic for Brazilian music, namely, música popular brasileira, or MPB, and Brazilian Instrumental Music. This article aims to describe the intersections of these two fields of artistic production by examining the contributions of saxophonist Nivaldo Ornelas to the recordings of Nascimento’s song “Hoje É Dia de El Rey,” understood as manifestations of resistance and resilience of subaltern voices as a decolonial alternative to hegemonic projects—whether within aesthetic, political, racial, or economic scenarios.

Résumé

Les musiciens brésiliens Milton Nascimento et Nivaldo Ornelas ont commencé à travailler ensemble dans les années 1960 à Belo Horizonte. Ce fut particulièrement une décennie de grandes transformations pour la géopolitique mondiale et la société brésilienne, qui traversait un énorme exode rural avec une forte croissance des centres urbains. Pendant cette période, deux domaines de la production culturelle ont émergé dans l’environnement de la musique populaire, qui seront paradigmatiques pour la musique brésilienne à partir de ce moment, à savoir : MPB et la Musique Instrumentale Brésilienne. Cet article vise à décrire les intersections de ces deux domaines de production à travers la contribution du saxophoniste Nivaldo Ornelas aux enregistrements de la chanson « Hoje É Dia de El Rey », de Nascimento, comprise comme une manifestation de résistance et de résilience des voix subalternes comme une solution de rechange aux projets hégémoniques — que ce soit dans des scénarios esthétiques, politiques, raciaux ou économiques.

Corps de l’article

A Sociological Background for música popular brasileira (MPB): The Avant-Garde of Popular Music

During the first half of the 1970s, Brazil’s recording industry was consolidated around a list of artists—composers, lyricists, instrumentalists, arrangers, and producers—who helped to delimit aesthetic paths that pointed to the consolidation of the musical tendency called música popular brasileira. Known by the acronym MPB, this musical style is distinct from the broader category of Brazilian popular music, which refers to Brazilian urban production from the mid-eighteenth century on and which became defined in the forms of lundus[1] and modinhas[2] as elements of nationalism, gathered around the ideals of Brazilian musicologists such as Renato Almeida (1895–1981) and Mário de Andrade (1893–1945) during the first decades of the twentieth century.

These elements were updated in modern Brazilian popular music in the second half of the twentieth century, initially with the cultural movement known as tropicalismo,[3] which had as a musical cornerstone the album Panis et Circensis (Tropicália, 1968), the works of authors such as Gilberto Gil (b. 1942), Tom Zé (b. 1936), Caetano Veloso (b. 1942), and the inventive sonorities of Rogerio Duprat’s (1932–2006) arrangements.[4] Tropicalismo either weakened or transgressed aesthetic oppositions—such as global/local, ancient/contemporary, cultured/vulgar—through the fragmentation of the sonic discourse and the re-articulation of cultural references.

From this point on, Brazilian mass culture opened itself not only to North American and European mass media, but also to Brazilian regional references that moved it away from the country’s better-known urban-centered cultural production. Decentered voices from places other than Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo came to be known nationally to the general consumer public, as the Tropicalista movement became known through the baianos group, and, a few years later, the mineiros[5] group. Milton Nascimento (b. 1942) and his band, Som Imaginário—analyzed in this article through the contributions of the saxophonist Nivaldo Ornelas (b. 1941)—was one of the main articulators of the musical phenomenon known nationally as Clube da Esquina.[6] In fact, this process starts, in modern terms[7]—and in a forceful way as a commodity—with the rise of Luiz Gonzaga[8] (1912–1989) in the early 1940s, followed by Jackson do Pandeiro[9] (1919–1982) and Dorival Caymmi[10] (1914–2008). These three musicians are among the main players that introduced new elements of heterogeneity to the aesthetic horizon of Brazilian urban songwriting, with the introduction of musical genres from the Northeast region of the country, many of them structured with modal melodic/harmonic characteristics. On the other hand, the group Quarteto Novo (New Quartet), formed by Airto Moreira (b. 1941), Hermeto Pascoal (b. 1936), Theo de Barros (b. 1943), and Heraldo do Monte (b. 1935), proved to be the catalyst for a new aesthetic force related to instrumental music, debuting a new tradition where more regional elements of Northeastern Brazilian music are combined in a progressive format that would become the main model for Brazilian urban popular instrumental music in the decades that followed.[11]

During the 1960s, MPB and Brazilian Instrumental music,[12] the ascending musical modalities[13] of national urban identities, coincided with “a process of institutionalization in the music scene, of which it became the dynamic center.”[14] These musical productions were taken at that time as symbolic goods[15] of distinction by a large part of Brazilian urban middle-class audiences. Following a trend that began with bossa nova[16] in the late 1950s, it was the middle-class youth associated with universities—one of the traditional spots of resistance against the Brazilian military dictatorship—that began listening to this new music, notably after the institution of the AI-5 decree[17] in December 1968. From then on, a change started to happen in the logic of musical reception in Brazil, as original urban popular music gained recognition in the media and consumption rose among socially engaged youth audiences.

Another aspect has been less analyzed: the adequacy of the song product to a predominantly “young” demand. This social age category has, since the late 1960s, been marked by the aestheticization of diffuse forms of social contestation, gathered around a culture of consumption disseminated through the media. Tropicalism was the movement that consolidated this trend, verifiable in many Western countries, within Brazil’s borders. By assuming, in the field of music, the culture of consumption to be part of the “young” identity, Tropicalismo helped to further restrict the very possibility of performing its songs outside this circuit. By playing this historical role, the “group of Baianos” placed themselves within a movement to redefine the status of MPB, in progress since Bossa Nova.[18]

As the growth of this new field shows, the MPB becomes established through mechanisms of public formation—from peer-groups to the general public—that consecrated and diffused its songs (the Brazilian Song Festivals—Festivais da Canção—performed this dual function). We derive this proposition from Pierre Bourdieu’s “The Market of Symbolic Goods,” where he argues that intellectual and artistic production becomes autonomous with the emergence of three correlated historical processes: a) the constitution of a public of consumers, b) the constitution of a field of producers, and c) the instances of consecration and diffusion of these symbolic goods.[19]

Transposed to the musical field of MPB, these three instances identified by Bourdieu allow us to understand this specific musical modality as a field of cultural practices tending towards autonomy, a process that will be intensified throughout the 1970s. However, this phenomenon does not happen solely with MPB’s instrumental modality. At the time, the field of Brazilian Instrumental music was unable to “guarantee the producers of symbolic goods […] minimal conditions of economic independence.”[20] That specific cultural field was mainly formed by limited peer-groups, whose work, like those of avant-garde groups discussed by Bourdieu, was reserved for fellow initiates. Only in later years, with the co-opting of a dilettante audience, would this market expand.

Bourdieu, in his argument, draws a dichotomy between scholarly production and the mass culture industry, the former based on originality and the latter on stereotype and imitation.[21] These fields can be simultaneously perceived in the MPB of the 1970s, since they are subjected to a market ruled by record labels and concentrated modes of diffusion, such as radio and television stations. However, Brazilian Instrumental music, an important reference for MPB, and other non-commercial music differed from this market in that they were constituted mostly by composers, arrangers, and instrumentalists from related peer-groups.

Thus, artists dedicated to urban Brazilian Instrumental music[22] would necessarily have to move through other fields of production, which would preferably have aesthetic similarities with that specific instrumental modality,[23] in order to establish themselves professionally in their craft. On the other hand, the circuit of artists involved in the MPB field, both musicians and lyricists, would seek to work with highly skilled musical instrumentalists whose expertise offered legitimacy to their musical craft and artistic distinction. These fields end up demonstrating connections through mutualism,[24] in which the exchanges between agents are designed as reciprocally beneficial deals. This double awareness of the production associated with MPB—that is, the ambivalent relationship between market product and disinterested art—according to Marcos Napolitano, generates a field that is, at the same time, autonomous and heteronomous: “[…] the history of renewed MPB, a product of the 1960s, was marked by the struggle and possible articulations of these two opposing sectors: one instituting movement that configures autonomy and another of reordering the commercial realization of the song, which enables heteronomy.”[25]

Another theorist of autonomy in the art field is Peter Bürger who, in his Theory of the Avant-Garde,[26] identifies constitutive elements of artistic movements to develop a critique of the autonomy of the artistic field once established in a market of bourgeois production and consumption. Commenting on Bürger's theory, Ernesto Sampaio notes:

The concept of autonomy of art is the fundamental touchstone of Bürger's theory, indispensable to understand his idea of the avant-garde. The author identifies autonomy with the attribute of bourgeois art on which the institution establishes its ideological structure. The avant-garde, as a self-criticism of modern art, rejects the Institution, seeking to reintroduce into the practice of life an art devoid of itself, installed in a kind of aesthetic limbo, deprived of function and effect.[27]

Therefore, references of rupture—discontinuity—of artistic schemes already assimilated by other peers and public consumers emerge as one of the key elements of the articulation of avant-garde artistic practices in Brazilian urban popular musical processes. In the case of the MPB in the 1970s, this was distinguished by rare artistic innovation.

Imagining Sounds: A Collaborative Process for Milagre dos Peixes[28]

Recordings figure prominently as primary sources of investigation for the study of popular music, especially when studying performative musical acts. The media used for these recordings have drastically changed the experience of musical production and communication. Recordings—although still limited from the point of view of the hic et nunc of the lived performance—provide marks and memories of the sound gestures of a specific rendition, of its ambience and spatiality, and at the same time, create a new performance of its own articulated by listening.[29] Listening that can be either individual or collective—as in an acoustic arena[30]—as observed by Brotas:

From the development of modern sound media, it is possible to measure a passage from a Cartesian plane of the visualist imagination to a more fluid, mobile, and multiple conception of space. The experience from sound media, in this plural context, presents a double movement, characteristic of history linked, on the one hand, to an interior and connected to the singular, personal. On the other hand, it is oriented towards the production of collective and externalized forms.[31]

The double movement between singular and collective forms of cultural production—and consumption—reinforces the importance of the session musicians in Nascimento’s work, which is the expression of a collaborative process where performers, in Umberto Eco’s words, often decide “how long to hold a note or in what order to group the sounds: all this amounts to an act of improvised creation.”[32]

The musicians around the group of mineiros that accompanied Nascimento during the 1970s would have its first encounters in the mid-1960s at Berimbau Clube,[33] a jazz club dedicated only to instrumental music located at the time in the city of Belo Horizonte, capital of the State of Minas Gerais.

In 1973, at the time of the recordings of his sixth studio album, Milagre dos Peixes, Nascimento’s idea was to get that group together again, to “bring our band together in a new form.”[34] The new directions for Nascimento’s music would place guitarist Toninho Horta (b. 1948) and saxophonist Nivaldo Ornelas (b. 1942) alongside pianist Wagner Tiso (b. 1945), bassist Luiz Alves (b. 1944), and drummer Robertinho Silva (b. 1941). As Tiso comments on the encounters that preceded the recordings of Nascimento’s albums, this band would define the sound of the work he released in the first half of that decade:

We practically set up the whole album in the studio. I arrived with the lead sheets; with ideas for introduction; ideas for the endings; but all musicians that were there gave opinions, the main characteristic of that group, and Milton’s most of all, is that he would accept everyone's suggestions, and would give his. I would later orchestrate all of that. I was the orchestrator, so I put it to orchestra, right? So, I wrote to the orchestra, besides helping with the rhythm section, I directed the orchestra and played piano and organ.[35]

The blurred boundaries between authorship and performance reinforce the impermanence of making music, and therefore of the work of art, as commented by Umberto Eco:

the new musical works […] reject the definitive, concluded message and multiply the formal possibilities of the distribution of their elements. They appeal to the initiative of the individual performer, and hence they offer themselves not as finite works which prescribe specific repetition along given structural coordinates but as “open” works, which are brought to their conclusion by the performer at the same time as he experiences them on an aesthetic plane.[36]

The notion of an “open work” can be extended in a more precise manner by another of Eco’s concepts, that of “the work in movement”: “[...] ‘open’ works, insofar as they are in movement, are characterized by the invitation to make the work together with the author.”[37]

This “work in movement” offers a more accurate sense of the irreproducibility of the moment of performance in art. As Paul Zumthor argues, it situates creation in the moment: “The notion of performance [...] [as] empirical commitment, now and at this moment, of the integrity of a particular being in a given situation.”[38] In the dynamics of popular music, this subverts the roles of authorship and musicianship or, in Bourdieu's words, the social places occupied by the opposed terms of auctor and lector. As we have stated elsewhere:

This distinction between the two practices may be related to the opposed terms lector, referring to the interpreter, to the one who lends his musicality to illuminate the work of another producer, and auctor, in this case the composer or master creator. These practices, which represent respectively the performance of the musician and the products of the culture industry, are linked to the organization of field that is either autonomous or in the process of becoming autonomous, such as the field of erudite or scholarly music.[39]

The negotiations in the roles of these social actors can also be related to Nicholas Cook's[40] understanding of performance as an intermediate instance between the process of making music and the product, its materialization or embodiment, in a singularity here and now. The arrangements (or written parts) work as scripts, representations of what is about to come, to be reified, whether in their evocative (poietic) or fruitive (esthesic)[41] acts. In the case of Milton Nascimento, the network of actions by musicians, lyricists, and producers blurs the borders between collaborators and producers, and should be measured “not by the uniqueness of exceptional creators, but by the agreements generated among many participants.”[42]

It is worth mentioning the autonomy granted by the executive producer Milton Miranda from EMI-Odeon, the label company of Nascimento’s album Milagre dos Peixes. That autonomy is evident when Nascimento defines his musical paths without the interference of his executive producer. This credential was appreciated by the critics and an audience of connoisseurs, many of whom were familiar with progressive jazz and avant-garde European and Latin American music. Napolitano describes some of the aspects of musical autonomy in the music of Nascimento:

With the new status of popular music in Brazil, at the end of the 1960s the acronym MPB came to mean a socially valued music, synonymous with “good taste,” despite selling less than the songs considered “low quality” by music critics [...]. The words of Milton Miranda, director of the Odeon label, demonstrates this paradox, which is constitutive part of the culture industry. Addressing the newcomer Milton Nascimento, Miranda justifies the autonomy that the label granted the composer. We have our commercial acts. You Mineiros are our prestigious band. The record company won't interfere. You record whatever you want.[43]

At the same time, this autonomy was accompanied by a number of calculated risks, as records were subjected to certain conditions of the music market that, closely related to the cultural industry and mass media, would place them on the limits of heteronomy. This ambivalence echoes the internal movements within the artwork, which oscillates between a progressive artistic autonomy and a heteronomy delimited by rules of the phonographic market, understood as a continuity of patterns used to reinforce aesthetic elements already assimilated by the captive public of consumers.

Nivaldo Ornelas in “Hoje é Dia de El Rey”: Rupture and Resistance

The album Milagre dos Peixes was a product of its time.[44] The artistic expression resulted from restrictive policies and censorship: “[O]f the eleven tracks selected for the album, Milton had already decided to record five tracks without lyrics—but he saw this number suddenly increase to eight because of the vetoes of censorship,”[45] which ended up emphasizing the instrumental and experimental character of the album, and thus distanced it from the regular audience’s expectations.

One of the compositions that underwent cuts was “Hoje É Dia de El Rey” (Nascimento, Borges, 1973), which had its lyrics suppressed from the final version. This veto frustrated the initial plan, where Dorival Caymmi and Milton Nascimento would interpret the roles of father and son in a conversation evoking aspects of repression and totalitarianism while also hinting at resistance—to start with, the expression el Rey (the King) in the song’s title comes from old Portuguese, hence making a clear connection to the Brazilian colonial period. An illustrative passage in the song’s lyrics (written by Márcio Borges), which listeners may not be aware of, is this one: “Join the many lies/Throw the soldiers on the street/You know nothing of this land/Today is the day of the moon.”[46]

Regarding the recording of this track, saxophonist Nivaldo Ornelas has commented: “But those lyrics were censored, already during the recording, and that's what's terrible, isn't it? So, in the passages that were supposed to have voices, I did the solo instead.”[47] During the last section of the studio version of the song, one can notice a long saxophone improvised solo where Ornelas, in a contrasting way, presents two opposing but complementary discursive aesthetics. This musical solution symbolizes the contributions of Ornelas' performance as a means of resistance, since the interpreter translates the common feeling of the group of musicians into a narrative that reinforces Nascimento's work of art, and of rupture, since it breaks with the predictable order of musical events.

These discursive aesthetics can be understood in terms of idiomatic and non-idiomatic improvisations, which guitarist Derek Bailey (b. 1993) has used to categorize these antagonistic musical discursive constructions. The former term refers to practices of improvisation under the bias of a stylistic delimitation of standardized melodic-harmonic systems, such as tonal, modal, or even serial systems, with references to the idiomatism as a structured systematization of a social discourse that is commonly shared and ordered by the articulation of sound signals.[48] The latter refers to a system that incorporates free improvisation, an approach characterized by diversity, “established by its sonic-musical identity, and from the person, or people, that are playing the music.”[49]

Even with the author’s delimitation of the terms idiomatic and non-idiomatic in their strict use, the same terminology can be applied in music to organology, that is, the study of musical instruments, their classification and main morphological and acoustic characteristics, including distinct techniques of sound production and the results of it. In this sense, Thomas Cardoso[50] considers the use of the term “idiomatic” referring to an idiomatic construction where the morphological aspects of some instrumentation define, in a certain way, the musical ideas expressed in the performance. This construction would work as an intermediate instance between prescriptive writing and its realization in the face of specific given acoustic and sonic possibilities.

Due to the ambivalence of the term “idiomatic,” which musicologists mostly use when referring to morphological structural characteristics that define some instrumental identities, this article adopts instead the opposed terms of endogenous and exogenous[51] improvisational musical practices. These terms refer to approaches that either correspond to a certain horizon of expectations perceived in a specific musical genre or style or, conversely, allow for unexpected approaches derived from the usage of unusual musical structures of some field of artistic production.

The understanding of these standing points of interpretation accompanies processes of autonomy and heteronomy according to the aesthetic decisions of the group Som Imaginário during the recording session of “Hoje é Dia de El Rey,” especially with the musical decisions of Nivaldo Ornelas on the tenor saxophone. The elements of avant-garde music that are flagrantly identifiable in his playing, which includes both endogenous and exogenous practices, would expand the limits of MPB. In this sense, Ornelas plays with both sides of the coin, dealing with the thin line between tradition and innovation.

The most prominent references to the expansion of sonic possibilities in the field of artistic popular music occurred in a very accentuated way during the 1960s through the development of styles associated with American jazz, and more specifically with free jazz,[52] as exemplified by the music of Ornette Coleman (1930–2015), with the album entitled Free Jazz (1961), and several others: Cecil Taylor (1929–2018) with Nefertiti, The Beautiful One Has Come (1962); Albert Ayler (1935–1970) with Spirits (1964); Eric Dolphy (1928–1964) with Out to Lunch (1964); and John Coltrane (1926–1967), who, towards the end of his career, experienced profound musical freedom imprinted in recordings that presented discursive ruptures applied to music, as in A Love Supreme (1965), Sun Ship (1965), Meditations (1966), and Interstellar Regions (1967), among other records.

The free aesthetics forged by African-American jazz musicians was defined primarily in terms of two elements. On the one hand, an expansion of musical experiences under the sign of transcendence mainly through musical expression itself, and, on the other, as a form of resistance against oppression, prejudice, and inequality. Therefore, the avant-garde of jazz, from an artistic point of view, introduced strangeness as a tool of enjoyment and engagement, making that music, in a certain sense, unrecognizable, rejecting the function of entertainment it once had for the white bourgeois class. As for the strangeness related to avant-garde aesthetics, Bürger comments:

If the Russian formalists view ‘defamiliarization’ as the artistic technique, recognition that this category is a general one is made possible by the circumstance that in the historical avant-garde movements, shocking the recipient becomes the dominant principle of artistic intent. Because defamiliarization thereby does in fact become the dominant artistic technique, it can be discovered as a general category. […] What is claimed is no more than a connection—though a necessary one—between the principle of shock in avant-gardiste art and the recognition that defamiliarization is a category of general validity.[53]

During that same period, in Brazil, saxophonist Nivaldo Ornelas was deeply involved with the reverberations of free jazz while living in Belo Horizonte, having formed, in 1967, the instrumental group Quarteto Contemporâneo alongside drummer Paulo Braga, pianist Jairo Moura, and bassist Tiberius Caesar. What this aesthetic approach proposes is a type of feeling that is ordered and performed, usually in a collective way—as in a dialogue involving all musicians on stage—and in which they elaborate new virtual arrangements. This new musical attitude can broaden horizons in order to manipulate musical schemes by dealing with some of the normative musical references given by Western music. Those musical manifestations reinforce the perspective of the decentering of the paradigms already assimilated by the cultural industry and open new possibilities in the context of avant-garde artforms.

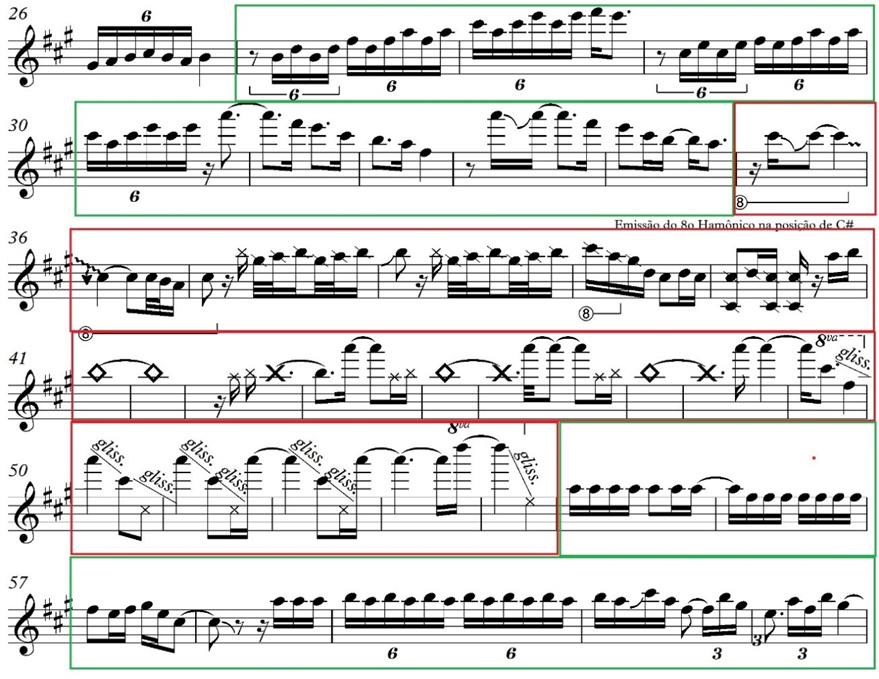

Traces of Ornelas’ experimentalism during the Quarteto Contemporâneo period can be perceived in the solo of “Hoje É Dia de El Rey.” At the beginning of the improvised solo, the musician uses diatonic rhythmic/melodic patterns, deeply rooted in the traditions of Brazilian music. During improvisation, Ornelas develops the lines by digging into almost chaotic melodic material. Both approaches can be understood in terms of endogenous and exogenous musical practices, the first based on already assimilated musical schemes and the second on expansion and extrapolation of what normally surrounds the MPB field, as the following example suggests (see Fig. 1):

Fig. 1

Excerpt of the transcription of Nivaldo Ornelas’ saxophone solo on “Hoje é Dia de El Rey”, from the album Milagre dos Peixes (1973), from 5’42” to 6’43”. The green marks (from bars 27 to 34 and from bar 55 to 61) represent endogenous approaches to improvisation, while the red marks (from bars 35 to 54) indicate exogenous approaches of tonal/modal extrapolation within the usage of extended saxophone techniques, such as top-tones, false fingerings, and multiphonics.

This excerpt of Ornelas’ music includes some innovative extended techniques inspired by North American free jazz[54] and used by international avant-garde musicians and composers such as Sigurd Rascher (1907–2001),[55] Lars-Erik Larsson (1908–1986), Luciano Berio (1925–2003), or Ryō Noda (b. 1948): the top tones in the altissimo registers of the saxophone, false fingerings, multiphonics,[56] and randomness. These approaches are examples of exogenous musical characteristics within the MPB field, but they are also idiomatic in the sense of the organology of the saxophone, since the results of these sonic intentions are properly conceived by that instrument’s typical morphology.

The mentioned aspects of musical rupture reinforce the prevalence of a craft that resiliently works as a key of resistance through subjectivities and the group of musicians as a whole. The strangeness and surprise of Ornelas’ performance choices react to the Brazilian dictatorship’s restrictive policies and offer an affirmative standing point of authenticity of a Latin American artform. Márcio Borges, the song’s lyricist, sums up the general feeling of that group of producers when he says: “To the songwriter, Nivaldo Ornelas: ‘he spoke for all of us’.”[57]

Final Considerations

Our discussion of MPB in the 1970s attempts to demonstrate how the relative autonomy of aesthetic innovation confronted and interacted with the heteronomy of market rules, including processes of consecration and reception emerging with censorship and other limitations in the phonographic industry. In its focus on the exchanges between Milton Nascimento and Nivaldo Ornelas, it also shows how cultural producers affiliated with the MPB field sought artistic ties with Brazilian Instrumental musicians.

The aesthetic aspects of these two fields can be described as a relation of continuity and rupture, quoted here in the manifestations of the recording of the song “Hoje É Dia de El Rey.” This song, which stretched the boundaries of a previous horizon of expectations for the reception of the musical artwork by a specific audience—mainly formed by students—during the 1970s, resonates in later musical productions[58] that convey similar signs of resistance to Brazil and Latin America.[59]

This collective musical representation worked as a manifesto that would engage that generation against censorship and repression, inciting changes that would start to be noticed at the end of the decade. The elements of rupture are linked, in turn, to some of the references of the artistic avant-garde, exogenous to urban popular Brazilian music and in opposition to previously assimilated, endogenous musical schemes. By all means, this aesthetic extrapolation, at least if analyzed by Ornelas’ performance on the tenor saxophone, comes from a technical idiomatic expression of that instrument, which opens new possibilities for its use, as commented by Bürger:

From this perspective, one of the central theses of Adorno's aesthetics, “the key to any and every content (Gehalt) of art lies in its technique” becomes clear. Only because during the last one hundred years, the relation between the formal (technical) elements of the work and its content (those elements which make statements) changed and form became in fact predominant can this thesis be formulated at all.[60]

The originality of the musical production of Nascimento, Ornelas, and the musicians of Som Imaginário is remarkably relevant for understanding the transformations of popular music in contemporary Brazilian culture. As a stance of cultural resistance, the articulations and interpretive solutions given in the recordings tend to assimilate the tensions of censorship into a process of resilience that altered the original song, retaining only the phrase “filho meu” (my son) from the previous lyrics, to make it an instrumental piece where Ornelas’ saxophone provides the metaphorical ground for elements of rupture to bloom into a new praxis, a subaltern locus of enunciation.

Parties annexes

Biographical note

Bernardo Vescovi Fabris is Associate Professor in the Department of Music at the Federal University of Ouro Preto in Brazil. He has conducted post-doctoral research in popular music at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (2017). He holds a PhD in music from the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro (2010) and obtained his Master’s and Bachelor’s degrees in music from the Federal University of Minas Gerais (in 2005 and 2002, respectively) specializing in saxophone and Brazilian music. His research interests include Pan-American popular music; cultural musicology; musical performance; music education; and music and interdisciplinarity.

Notes

-

[1]

As Edilson Vicente de Lima explains, lundus can be defined “[i]nitially, as a form of dance in the eighteenth century and its appearance is first linked to the process of Brazilian colonization and is intertwined, above all, in the confluence of European cultures, via Portugal and Spain, as well as the African culture brought through slave labour in the early centuries of colonization.” Edilson Vicente de Lima, A modinha e o Lundu: dois clássicos nos trópicos, doctoral dissertation, Universidade de São Paulo, 2010, p. 100, our translation. “Inicialmente, como forma de dança no século XVIII e seu aparecimento está inicialmente ligado ao processo de colonização brasileiro e imbricado, sobretudo, na confluência das culturas europeias, via Portugal e Espanha, bem como a cultura africana trazida como mão de obra escrava, nos primeiros séculos de colonização.”

-

[2]

Regarding modinha, de Lima says: “A kind of generic denomination for Luso-Brazilian love songs from the last quarter of the eighteenth century.” De Lima, 2010, p. 17, our translation. “Uma espécie de denominação genérica para a canção de amor luso-brasileira do último quartel do século XVIII.”

-

[3]

For more information concerning the cultural movement Tropicália, see Carlos Calado, Tropicália: a história de uma revolução musical, São Paulo, Editora 34, 1997; Christopher Dunn, Brutality Garden: Tropicália and the Emergence of a Brazilian Counterculture, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, University of North Carolina Press, 2001; Caetano Veloso, Tropical Truth: A Story of Music and Revolution in Brazil, New York, Da Capo Press, 2002.

-

[4]

Even though it is considered a cultural movement with ramifications in cinematography, literature, theater, and visual arts, Tropicália’s greatest recognition probably comes from its musical production, whose aesthetics are considered as the main reference of the 1960s avant-garde MPB.

-

[5]

The influence of the Tropicalist musical aesthetics on the group of mineiros is referred to by Calado as: “Without the musical ‘flood’ triggered by Tropicália, it would also be difficult to imagine, in the early 1970s, Milton Nascimento singing “Para Lennon & McCartney” accompanied by electric guitars. It was the harbinger of the legendary Clube da Esquina, which launched an original group of composers from Minas Gerais, such as Toninho Horta, Wagner Tiso, Lô Borges, Fernando Brant, Beto Guedes, Márcio Borges, and Ronaldo Bastos.” our translation “Sem o ‘alagamento’ musical desencadeado pela Tropicália, também seria difícil imaginar, já no início da década de 70, um Milton Nascimento cantando Para Lennon & McCartney, acompanhado por guitarras elétricas. Era o prenúncio do lendário Clube da Esquina, que lançou um original grupo de compositores mineiros, como Toninho Horta, Wagner Tiso, Lô Borges, Fernando Brant, Beto Guedes, Márcio Borges e Ronaldo Bastos.” Carlos Calado, Tropicália: a história de uma revolução musical. São Paulo, Editora 34, 1997, p. 298.

-

[6]

The title of the homonymous album Clube da Esquina, released under the names of Lô Borges and Milton Nascimento in 1972, referenced the group of musicians, each with their autonomous careers: “There he met the other members of what would be the legendary Clube da Esquina—the Corner Club or Corner Boys: Marcio Hilton Borges, Fernando Brant, Ronaldo Bastos, and later Lô Borges, Beto Guedes, and Toninho Horta. This group became a creative nucleus sharing a language, creation, and performance, from which several partnerships evolved.” Martha de Ulhôa Carvalho, “Canção da America—Style and emotion in Brazilian popular song,” Popular Music, vol. 9, no. 3, 1990, p. 324.

-

[7]

From the 1920s to the end of the 1930s, many groups appeared on the musical scene in Rio de Janeiro, such as Os Turunas Pernambucanos, Bando de Tangarás, or even Os Oito Batutas, who incorporated rural-inspired tunes into their repertoire and explored the “exoticism” of regional themes; however, this article focuses on the processes involved in the development of the so-called MPB, that is, the music that constitutes the “modern,” urban, popular Brazilian music—developments that can be mostly perceived from the mid-1940s on.

-

[8]

Luiz Gonzaga, called Rei do Baião (King of Baião), has been known nationally since 1941 after his first appearance at Radio Nacional in a show presented by the composer Ary Barroso.

-

[9]

Born José Gomes Filho, Jackson do Pandeiro was called King of Rhythm and became nationally famous in Brazil in 1953 for interpreting the song “Sebastiana,” composed by Rosil Cavalcanti. Do Pandeiro is considered the main exponent of the musical genre Forró.

-

[10]

In 1952, Caymmi released the paradigmatic album Canções Praieiras (Seaside Songs), in which the author sang and played acoustic guitar interpreting his own compositions, shaped in idyllic themes that resemble images of his home state of Bahia, organized in modal and tonal harmonic/melodic moods. This work has since influenced many composers and performers.

-

[11]

For more information about the group Quarteto Novo and especially the music of Hermeto Pascoal, refer to: Bernardo Vescovi Fabris and Cléber José Bernardes Alves, “Forró Em Santo André ao vivo em Montreux: um estudo de caso sobre a música de Hermeto Pascoal através dos solos improvisados de Nivaldo Ornelas e Cacau Queiroz,” Anais do IV Festival de Música Contemporânea Brasileira, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 2017, p. 69–88.

-

[12]

The term “Instrumental Brazilian Music” is locally used instead of the mostly common global form Brazilian Jazz.

-

[13]

The term “musical modality” applies best in the cases of MPB and Brazilian Instrumental Music as they are both different ways of interpreting a wide assortment of popular musical genres and styles. As I have noted elsewhere: “[W]e chose to use the term ‘modality,’ because we believe that instrumental music is a way of making popular music and not a constituted genre, that is, because different genres of popular music are contained within this modality, such as samba, baião, choro, jazz, or even rock.” our translation “optamos pelo uso do termo modalidade, por acreditar que música instrumental se trata de uma maneira de se fazer música popular e não de um gênero constituído, ou seja, por estarem contidos dentro desta modalidade gêneros diversos de música popular, tais como o samba, o baião, o choro, o jazz ou mesmo o rock.” Bernardo Vescovi Fabris, O Saxofone de Nivaldo Ornelas e seus Arredores: investigação e análise de características musicais híbridas em sua obra e interpretação, doctoral dissertation, Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, 2010, p. 5.

-

[14]

“Sofreu um processo de institucionalização na cena musical, tornando-se o seu centro dinâmico.” Marcos Napolitano, “A Música Popular Brasileira (MPB) dos Anos 1970: resistência política e consumo cultural,” Anais do IV Congresso de la Rama Latinoamericana de la IASPM, Mexico City, 2002, p. 2.

-

[15]

The expression “symbolic goods” is based on its usage by Pierre Bourdieu in the text “The Market of Symbolic Goods” first published in L’année sociologique in 1971. Pierre Bourdieu, “O Mercado de Bens Simbólicos,” A Economia das Trocas Simbólicas, trans. Sergio Miceli, São Paulo, Perspectiva, 2007, p. 99–153.

-

[16]

For more information concerning the musical movement bossa nova, see Suzel Ana Reily, “Tom Jobim and the Bossa Nova Era,” Popular Music, vol. 15, no. 1, 1996, p. 1–16.

-

[17]

The AI-5 or Ato Institucional nº 5 was instituted on December 13, 1968, and lasted until 1979, and, according to Maria Celina D’Araújo, “it was the most finished expression of the Brazilian military dictatorship (1964–1985). […] [It] produced a cast of arbitrary actions with lasting effects.” The harshest moment of the regime, this period saw political persecutions and intense censorship. For further information about the AI-5 and its consequences for Brazilian culture, see Renato Ortiz, Cultura Brasileira e Identidade Nacional, São Paulo, Editora Brasiliense, 1985.

-

[18]

“Outro aspecto tem sido menos analisado: a adequação do produto canção a uma demanda predominantemente ‘jovem’. Esta categoria sócio-etária, desde o final dos anos 60, tem sido marcada pela estetização de formas de contestação social difusa, aglutinada em torno de uma cultura de consumo disseminada via mídia. O Tropicalismo foi o movimento que consolidou esta tendência, verificável em muitos países ocidentais, nos limites do Brasil. Ao assumir, no campo da música, a cultura de consumo como parte da identidade ‘jovem,’ o Tropicalismo ajudou a restringir ainda mais a própria possibilidade de realização da canção fora deste circuito. Ao desempenhar este papel histórico, o ‘grupo dos baianos’ se colocaram dentro de um movimento de redefinição do estatuto de MPB, em curso desde a Bossa Nova.” Napolitano, 2002, p. 188–189, our translation.

-

[19]

Pierre Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production. Essays on Art and Literature, New York, New York, Columbia University Press, 1993, p. 100.

-

[20]

“propiciar aos produtores de bens simbólicos [...] as condições minimais de independência econômica” our translation, Ibid., p. 100.

-

[21]

“The culture industry can only manipulate individuality so successfully because the fractured nature of society has always been reproduced within it. In the ready-made faces of film heroes and private persons fabricated according to magazine-cover stereotypes, a semblance of individuality—in which no one believes in any case—is fading, and the love for such hero-models is nourished by the secret satisfaction that the effort of individuation is at last being replaced by the admittedly more breathless one of imitation”; Max Horkheimer & Theodor W. Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment, Stanford, California, Stanford University Press, 2002, p. 126.

-

[22]

Lovisi defines Brazilian Instrumental Music in this way: “Here I use the term Brazilian Popular Instrumental Music (MPBI) to delimit a field of musical production that began to gain clearer contours in the 1970s and which has as one of its aesthetic characteristics the use of various Brazilian musical genres as matrixes of creation outside the universe of popular song.” Daniel Lovisi, “Música Instrumental, Tópicas e Identidade Cultural: um olhar sobre as produções de Milton Nascimento, Wagner Tiso e Nivaldo Ornelas no cenário da música mineira dos anos 70,” Revista Vórtex, vol. 7, no. 3, 2019, p. 2, our translation. “Utilizo aqui o termo Música Popular Brasileira Instrumental (MPBI) para delimitar um campo de produção musical que começou a ganhar contornos mais claros a partir dos anos 70 e que tem como uma de suas características estéticas a utilização de diversos gêneros musicais brasileiros como matrizes de criação fora do universo da canção popular.”

-

[23]

An important activity for instrumentalists who were associated with the production of MPB was the practice as studio musicians who could temporarily be hired by the record companies to play on other musicians' records. In the case of Nivaldo Ornelas, one of the agents of this communication, his performances during the 1970s were extremely fruitful, having played not only alongside musicians from his close circle of references (such as those from Minas Gerais), but also from a wide range of performances on records by artists such as Luiz Gonzaga Júnior, Ivan Lins, Edu Lobo, Fagner, Zé Ramalho, among others.

-

[24]

The term “mutualism” is used here in its original application in biology: “[A]ssociation between organisms of two different species in which each benefits. Mutualistic arrangements are most likely to develop between organisms with widely different living requirements.” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/science/mutualism-biology (accessed 28 August 2020).

-

[25]

“[...] a história da MPB renovada, produto dos anos 60, foi marcada pelo conflito e pelas articulações possíveis destes dois vetores opostos: um movimento instituinte que configura autonomia e outro, de reordenamento da realização comercial da canção, que enseja heteronomia.” Marcos Napolitano, Seguindo a Canção: Engajamento político e indústria cultural na MPB (1959–1969), São Paulo, Editora Anna Blume, 2001, p. 7, our translation.

-

[26]

Peter Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde, Minneapolis, Minnesota, University of Minnesota Press, 1984.

-

[27]

“O conceito de autonomia da arte é a pedra de toque fundamental de teoria de Burger, indispensável para compreender a sua ideia de vanguarda. O autor identifica a autonomia com o atributo da arte burguesa sobre o qual a instituição estabelece a sua estrutura ideológica. A vanguarda, enquanto autocritica da arte moderna, rejeita a instituição, procurando reintroduzir na prática da vida uma arte desfasada dela, instalada numa espécie de limbo estético, privada de função e de efeito”. Bürger, 1993, p. 10, our translation.

-

[28]

Milton Nascimento, Milagre dos Peixes, EMI-Odeon, Audio CD, 1973.

-

[29]

Listening here refers to the aspect highlighted by Murray Schafer as distinct from hearing, which is mainly an acoustic phenomenon and a mechanical (passive) act, whereas listening implies a psychoacoustic process of interaction between the listener and the sound object: “Obviously, we hear different things in different ways, and there's a lot of evidence to suggest that not just individuals, but societies as well, have different ways of listening. For example, there is a difference between what might be called focused listening and peripheral listening.” R. Murray Schafer, Educação Sonora: 100 exercícios de escuta e criação de sons, São Paulo, Editora Melhoramentos, 2009, p. 13, our translation. “Obviamente, ouvimos coisas diferentes de diferentes maneiras, e existem muitas evidências a sugerir que não apenas os indivíduos, mas também sociedades, têm maneiras distintas de ouvir. Por exemplo, há uma diferença entre o que pode ser chamado escuta focalizada e escuta periférica.”

-

[30]

“[…] [T]he ‘acoustic arena’ is defined as a region where listeners are part of a community that shares listening to a sound event.” Diego Brotas, Música, Mídia e Espacialidades: reapropriações do lugar para desenvolvimento de relações musicais (geo)localizadas, doctoral dissertation, Universidade Federal Fluminense, 2017, p. 74, our translation. “[...] a ‘arena acústica,’ é definida como uma região onde os ouvintes fazem parte de uma comunidade que compartilha a escuta de um evento sonoro.”

-

[31]

“A partir do desenvolvimento das mídias sonoras modernas, pode-se aferir uma passagem, de um plano cartesiano da imaginação visualista para uma concepção do espaço mais fluida, móvel e múltipla. A experiência a partir de mídias sonoras, nesse contexto plural, apresenta um movimento duplo, característico da história, por um lado ligada a uma internalidade e conectada ao singular, pessoal. Por outro lado, orientadas para a produção de formas coletivas e externalizadas.” Brotas, 2017, p. 88, our translation.

-

[32]

Umberto Eco, The Open Work, trans. Anna Cancogni, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1989, p. 37: “não raro estabelecendo a duração das notas ou a sucessão dos sons, num ato de improvisação criadora.”

-

[33]

For more information about Berimbau Clube, see Márcio Borges, Os Sonhos Não Envelhecem: histórias do Clube da Esquina, São Paulo, Geração Editorial, 1996.

-

[34]

Interview of Nivaldo Ornelas by Bernardo Fabris in April 2009, our translation.

-

[35]

“Wagner—A gente praticamente armou o disco todo no estúdio. Eu chegava com cifras, com ideias de introdução, ideias de final de música, mas todos os elementos que estavam ali, davam ideias, o grande negócio dessa turma, do Milton principalmente, é que ele aceitava sugestão de todos, e dava as dele. Eu depois eu coloria aquilo tudo, não é? Eu era o orquestrador, aí eu colocava orquestra, não é? Então eu colocava orquestra, além de ajudar na base, eu colocava a orquestra, tocava piano e órgão. O Som do Vinil,” Charles Gavin, Canal Brasil, 2018. Available on youtube.com, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sbgC2Z1qODY&t=276s (accessed 22 October 2021), our translation.

-

[36]

Eco, 1989, p. 3.

-

[37]

Ibid., p. 21, emphasis included.

-

[38]

“[...] o comprometimento empírico, agora e neste momento, da integridade de um ser particular numa situação dada.” Paul Zumthor, Performance, Recepção, Leitura, São Paulo, Cosac Naify, 2007, our translation.

-

[39]

“Esta distinção entre as duas práticas pode ser relacionada com os termos de oposição lector, referente ao intérprete, àquele que empresta a sua musicalidade para iluminar a obra de um outro autor; e auctor, no caso o compositor, o mestre criador, onde estas práticas representam respectivamente a atuação do músico junto à produção da indústria cultura e a sua produção, como criador, está ligado à organização de um campo autônomo, ou em autonomização, como o campo de produção erudita.” Fabris, 2010, p. 24, our translation.

-

[40]

Nicholas Cook, “Entre o processo e o produto: música e/enquanto performance,” Per music, no. 14, 2006, p. 5–22.

-

[41]

The terms Poietic and Esthesic refer here to their use in the text by Jean Molino, J.A. Underwood, and Craig Ayrey, “Musical Fact and the Semiology of Music,” Music Analysis, vol. 9, no. 2, 1990, p. 105–111 and 113–156.

-

[42]

“[N]ão pela singularidade dos criadores excepcionais, mas pelos acordos gerados entre muitos participantes.” Néstor Garcia Canclini, Culturas Híbridas; estratégias para entrar e sair da modernidade, São Paulo, Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 2008, p. 39, our translation.

-

[43]

“Com o novo estatuto da música popular vigente no Brasil, desde o final da década de 60, a sigla MPB passou a significar uma música socialmente valorizada, sinônimo de ‘bom gosto,’ mesmo vendendo menos que as músicas consideradas de ‘baixa qualidade’ pela crítica musical. [...] A fala de Milton Miranda, diretor da gravadora Odeon, demonstra esse paradoxo constituinte da indústria cultural. Dirigindo-se ao estreante Milton Nascimento, Miranda justifica a autonomia que a gravadora concedia ao compositor. ‘Nós temos os nossos comerciais. Vocês mineiros são a nossa faixa de prestígio. A gravadora não interfere. Vocês gravam o que quiserem.’” Napolitano, 2002, p. 3, our translation.

-

[44]

In Brazil, the restriction of freedom became more severe after the Institutional Decree Act no. 5 of 13 December 1968, signed by military president Artur da Costa e Silva (1899–1969), and enforced until 1 January 1979. Among the policies of military control were the persecution of any acts or individuals considered subversive to the current order. See note 18 above.

-

[45]

“Das 11 faixas selecionadas para o álbum, Milton já havia decidido gravar cinco com a melodia sem letra—mas viu esse número crescer subitamente para oito por causa dos vetos da censura.” Luiz Maciel, “A Arte de Colocar no Som o Que a Censura Tirou da Letra...e Fazer um Disco Revolucionário: Milagre dos Peixes—Milton Nascimento,” Célio Albuquerque (ed.), 1973: O Ano Que Reinventou a MPB: a história por trás dos discos que transformaram nossa cultura, Rio de Janeiro, Sonora Editora, 2017. p. 259, our translation.

-

[46]

“Juntai as muitas mentiras/jogai os soldados na rua/nada sabeis desta terra/hoje é o dia da lua.” “Hoje É Dia de El Rey” (Nascimento, Borges, 1973), our translation.

-

[47]

“O Som do Vinil”, Charles Gavin, Canal Brasil, 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sbgC2Z1qODY&t=276s (accessed 22 October 2021).

-

[48]

I have used the terms “idiomatic” and “non-idiomatic” to describe the two main forms of improvisation. Idiomatic improvisation, the most widely used, is mainly concerned with the expression of an idiom—such as jazz, flamenco, or baroque—and takes its identity and motivation from that idiom. Derek Bailey, Improvisation: Its Nature and Practice in Music, Boston, Da Capo Press, 1993, p. xi–xii.

-

[49]

Ibid., p. 83.

-

[50]

Thomas Fontes Saboga Cardoso, Um Violonista-Compositor Brasileiro: Guinga. A presença do idiomatismo em sua música, master’s thesis, Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, 2006.

-

[51]

The terms “endogenous” and “exogenous” improvisatory musical practices where coined for the ad hoc use in this investigation.

-

[52]

Free jazz is the name of an attitude to improvisation disseminated by Ornette Coleman (b. 1930) and Cecil Taylor (b. 1929). The term derives from the observation that performances of this style often ignore chord progressions. The music of Coleman’s 1960 record Free Jazz consists of a simultaneous and collective improvisation of two bands trying to remain free of key, melody, chord progressions, and previously determined time signatures. Mark C. Gridley, Jazz Styles: History and Analysis, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, Prentice Hall, 1988, p. 226.

-

[53]

Bürger, 1984, p. 18.

-

[54]

It is important to emphasize that free jazz is a fundamental key of African-American resistance against hegemonic North-Atlantic practices rooted mainly in Western European traditions.

-

[55]

Sigurd M. Raschèr, Top Tones for Saxophone: Four-Octave Range, New York, Carl Fischer, 1977.

-

[56]

For further information about extended techniques on the saxophone, see Patrick Murphy, Extended Techniques for Saxophone: An Approach through Musical Examples, research paper, Arizona State University, 2013.

-

[57]

“Para o compositor, Nivaldo Ornelas: falou por todos nós.” In Sheila Castro Diniz, “Nuvem Cigana: a trajetória do Clube da Esquina no Campo da MPB,” master’s thesis, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 2012, p. 119, our translation.

-

[58]

One of the most remarkable albums of political engagement released by Nascimento during the 1980s was Missa dos Quilombos (Mass of the Quilombos, 1982), where African memories of religious syncretism come together with Catholic rites towards diversity and tolerance throughout communal artistic, political, and cultural messages.

-

[59]

Milton Nascimento has, throughout his career, worked in collaboration with other important Latin American musicians, such as Mercedes Sosa (1935–2009), León Gieco (b. 1951), and Pablo Milanés (b. 1943), and recorded compositions of the Chilean songwriter Violeta Parra (1917–1967) and Uruguayan Eduardo Mateo (1940).

-

[60]

Bürger, 1984, p. 20.

Liste des figures

Fig. 1

Excerpt of the transcription of Nivaldo Ornelas’ saxophone solo on “Hoje é Dia de El Rey”, from the album Milagre dos Peixes (1973), from 5’42” to 6’43”. The green marks (from bars 27 to 34 and from bar 55 to 61) represent endogenous approaches to improvisation, while the red marks (from bars 35 to 54) indicate exogenous approaches of tonal/modal extrapolation within the usage of extended saxophone techniques, such as top-tones, false fingerings, and multiphonics.