Résumés

Abstract

This article introduces the Alpine Garden MisGuide / Le Jardin alpin autrement, a locative media project that endeavours to bring the complex cultural and historical insights of the paper archive on botanical exploration into dialogue with the embodied experience of visiting the living archive of contemporary botanic gardens. Recently created mobile guides to botanic gardens tend to fall back on the discourse of “anti-conquest”—where the colonial subject claims innocence even as s/he subordinates the other to their gaze—to frame their collections for the public. Taking a decolonial approach, this essay explores how the affordances of the MisGuide’s locative platform presents opportunities to challenge innocent or nostalgic presentations of botanic gardens’ collections and engage garden visitors in a more complex account of the influence of colonialism in the history of gardens and the environment.

Résumé

Cet article présente le Alpine Garden MisGuide / Le Jardin alpin autrement, un projet médiatique locatif qui s’efforce de faire dialoguer les connaissances culturelles et historiques complexes des archives papier sur l’exploration botanique avec l’expérience incarnée de la visite des archives vivantes des jardins botaniques contemporains. Les guides mobiles récemment créés sur les jardins botaniques tendent à se rabattre sur le discours de « l’anti-conquête » — où le sujet colonial revendique l’innocence alors même qu’il subordonne l’autre à son regard — afin d’encadrer leurs collections pour le public. Adoptant une approche décoloniale, cet essai explore comment les possibilités de la plate-forme locative du MisGuide offrent des occasions de contester des présentations innocentes ou nostalgiques des collections de jardins botaniques et d’engager les visiteurs des jardins dans un compte rendu plus complexe de l’influence du colonialisme dans l’histoire des jardins et de l’environnement.

Corps de l’article

The mobile app for the New York Botanical Garden, NYBG in Bloom,[1] welcomes garden visitors to its Enid A. Haupt Conservatory with an invitation to “[t]our the world in an hour.” “As you walk through each recreated habitat,” the recorded tour guide explains, “you’ll feel the temperature and humidity change. You can scale an Amazonian rainforest canopy or amble down an African desert path. Be the first among your friends to discover pre-historic cycads and endangered orchids.”[2] Shamelessly invoking a whole variety of colonial clichés associated with the Victorian glasshouse, NYBG in Bloom plays on well-established expectations of garden visitors to be able to enjoy the outer realms of empire from the safety and comfort of home. As Rebecca Preston has argued, the use of exotic plants with origins in the colonial periphery in British gardens during late nineteenth and early twentieth century allowed for “a very private form of imperial display which quietly expanded the horizons of its audience and allowed for a form of imaginative travel beyond, yet framed by the realm of home.”[3] A form of what Edward Said has referred to as “domestic imperial culture,”[4] botanic gardens have long relied on the discourse of “anti-conquest” to legitimate their mandate.[5] Initially associated with writing about natural history and botanical exploration, “anti-conquest,” as Mary Louise Pratt explains, is a term meant to capture the highly contradictory quality of colonial accounts of travel “whereby the European bourgeois subject seeks to secure his or her innocence in the same moment as they assert European hegemony.”[6]

It is troubling, therefore, to see the same “strategies of innocence” Pratt associates with post-Linnaean natural history reinscribed in the way the NYBG in Bloom app frames what the garden has to offer its visitors. “Miles of paths through inviting landscapes unfold for you on their way,” the voice of the recorded guide promises, as he encourages visitors to gaze out past the Leon Levy Visitor’s Centre to the garden in the distance. “Immerse yourself,” he continues,

in the beauty and endless variety of the gardens and collections before you. A narrated tram tour is always an option. Be sure to enjoy lunch in the Café, a return to visit Shop in the Garden on your way home. In between though, discover the scent of an unfamiliar flower, get a closer look at the texture of a fuzzy bug. The secrets of the garden await your discovery. You are invited to stroll at your own pace and explore this urban oasis as you please.

Like the landscapes described in the travel writing of colonial explorers, throughout the NYBG in Bloom app, the garden “presents itself” to “invisible […] seers,”[7] “inviting” and “unfold[ing] itself” without reference to the history of the acquisition or maintenance of its botanical collection. By encouraging the garden visitor to take in the world from a frictionless viewpoint, the app offers the user a “fantasy of dominance and appropriation that is built into this otherwise passive, open stance.”[8] Despite the relatively recent creation of the NYBG in Bloom locative media guide, it nevertheless perpetuates colonial modes of looking and experiencing the garden’s collection, and reinscribes the role natural history and botanic gardens have played in the legitimation of empire.

This article introduces the Alpine Garden MisGuide/Le Jardin alpin autrement,[9] a locative media project—unlike NYBG in Bloom—that endeavours to bring the complex cultural and historical insights of the paper archive on botanical exploration into dialogue with the embodied experience of visiting botanic garden, its living archive, and particular design. The Misguide’s intermedial approach seeks to engage garden visitors in a more critical understanding of the influence of colonialism on garden aesthetics and the implications this has for contemporary perceptions of the environment. The conceptualization and design of the Alpine Garden MisGuide emerged out of the following questions: How can locative media be used to unsettle rather than reinforce nostalgic or “eco-archaic” ways of experiencing botanic gardens, a space that is otherwise coded to encourage a relationship to nature that is innocent, apolitical, and outside time? How is research on colonial plant-hunting and garden writing transformed when it is tied to visitors’ experience of botanic gardens, essentially curating the garden with this material using a locative narratives and mobile media?

The New York Botanical Garden is not the only botanic garden to create an app meant to serve as a guide to their collection. Of late, institutions like the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and the Singapore Botanic Garden are also supplementing the printed information distributed to their visitors with locative media applications such as the Discover Kew app and SBG Navigator. While these digital platforms have the potential to introduce visitors to a more critical understanding of the history of botanic gardens, to date they have tended to serve as digital maps and conventional guides to their collection, or in the case of NYBG in Blooms, reinforce the perception of gardens as a “sanctuary of illusory innocence and eco-archaic return.”[10] If botanic gardens wish to expand their public engagement it is worth considering what kind of visitors their public interfaces encourage. Furthermore, while the promotional materials for these institutions invite visitors to experience the garden through a neocolonial gaze, the holdings of these gardens in their written, living, and material archives complicate this picture.

This article considers the more disruptive role locative media can play in unearthing the complexities of the colonial archive associated with botanic gardens. The Alpine Garden MisGuide—a locative media experience designed for the Montreal Botanical Garden/Le Jardin botanique de Montréal—leverages embodied ways of looking and experiencing the garden, disrupts the veneer of anti-conquest associated with botanical exploration, and activates what has been called transitive reading practices associated with locative media. Rather than encourage a nostalgia for the colonial worldview, the Alpine Garden MisGuide prompts garden visitors to engage with the history of extractivism that has produced the botanic garden’s colonial archive, and grapple with how this history continues to inform the ongoing impact of globalization and imperialism on the environment.

The Birth of the Alpine Garden

I first became interested in the untapped potential of locative media for disrupting the perception of these gardens as spaces outside time and politics while conducting research in the archives and physical spaces of botanic gardens like Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (RBG Kew), Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE), and the Montreal Botanical Garden (MBG). While the written and botanical holdings at these institutions have generated more critical encounters in scholarly works such as Lucile Brockway’s Science and Colonial Expansion[11] and Richard Drayton’s Nature’s Government,[12] there continues to be a disconnect between this rethinking of the history of botanical gardens and their public agenda. As a neo-Victorian institution that is the repository of a living archive of plants (many gathered in the outer reaches of colonial empires), botanic gardens are perfect place to engage publics in thinking about how the history of colonialism has come to shape our contemporary perceptions of the environment. The MBG ranks fourth in the world in terms of the size of its overall collection, and it is well known for its themed gardens, such as the Chinese, Japanese, and First Nations gardens. It is also the home to a large alpine garden—le Jardin alpin—first established in 1936, at a time when European plant hunters had amassed a large collection of alpine plants gathered in colonial regions, and rock and alpine garden culture was at the height of its popularity.

First established in 1931, the MBG was initially under the direction of its founder, Brother Marie-Victorin (a brother in the Christian Schools and President of Société de biologie de Montréal) and received municipal support from former student and then Mayor of Montreal, Camilien Houde. The designer of the garden, Henry Teuscher, was an American botanist with training in landscape architecture who first engaged in correspondence with Marie-Victorin about the garden, and was later appointed at the Chief Horticulturist in 1936.[13] As Erin Despard has argued, Teuscher “believed strongly in the power of gardens to ameliorate many social ills pertaining to life in the city.”[14] As evidence of this, Despard points to an essay Teuscher published shortly after the city took control of the garden in 1942, where he argues that “[m]odern man, living in his man-made desert of stone called the city, is a being without roots.”[15] “The botanical garden” Despard explains, “was conceived by him as a means to provide urban residents, not only contact with nature, but a ‘systematic education’ regarding their relation to it, thereby disposing them to become better citizens.”[16] A project of “social engineering”[17] therefore, the MBG was meant to play a “civilizing” role in relation to the population of Montreal. The alpine garden is singled out by Teuscher in this regard; reflecting specifically on “rock gardens” in a 1940 essay “Program for an Ideal Garden,” Teuscher warns against the modern botanical garden “lay[ing] out their rock garden in a natural manner” because “it is very difficult for the layman to select from such plants, the forms which are more amenable to cultivation and which will give in his own garden the effect he desires.”[18] Instead Teuscher stresses that the plants should be displayed “in a distinctly man-made garden,” and warns against adopting the naturalistic style of an “alpinum” that he characterizes as “an indiscriminate mixture in which it is impossible to find anything except by chance.”[19] While the contemporary Alpine garden at the MBG maintains geographical divisions with regard to the origins of different plants in its alpine collection, they are not displayed in the “straight beds” with the “mass plantings” that Teuscher envisioned in this essay. Instead, a more naturalistic and “wild” aesthetic dominates the design of the garden, complete with human-engineered waterfalls, mountain streams, screes, and trees pruned to appear as though their growth is stunted by high altitudes and falling boulders.

Rock and alpine garden culture first gained momentum in the late nineteenth century. Its popularity was prompted by a shift away from the use of large and expensive Victorian glasshouses (used to maintain more fragile tropical plants in temperature-controlled settings), towards an interest in more “hardy” plants, gathered in the mountainous regions in south and central Asia. Plants that grew in the cooler mountainous zones could be integrated and naturalized in the outdoor gardens in the imperial centre.[20] In other words, rather than maintain exotic plants in greenhouses in the winter and then “bed them out” in formal displays during the summer months (a costly enterprise in terms of heating and labour), European and North American horticulturists came to take pride in sustaining “gardenworthy” alpine exotics outdoors all year round.[21] William Robinson’s 1870 Alpine Flowers for Gardens and The Wild Garden were important guides for establishing the aesthetics associated with rock and alpine gardening, as they promoted the idea of “placing perfectly hardy exotic plants under conditions where they will thrive year round.”[22] In the opening pages of The Wild Garden, for example, Robinson advocates for establishing a “wild garden” over a glasshouse or formal garden because “there can be few more agreeable phases of communion with nature than naturalizing the natives of countries in which we are infinitely more interested than in those of greenhouse or stove plants.”[23] The emphasis in this new garden aesthetic led to the development of large public gardens that included features such as hanging bridges, waterfalls, and mountain streams showcased at institutions like RBGE, RBG Kew, and RHS Garden Wisley. Alpine plant hunters such as Reginald Farrer and Frank Kingdon Ward became celebrated figures who published well-known gardening manuals, such as My Rock Garden[24] and Common Sense Rock Gardening.[25] These books advise gardeners on how to best adapt their gardens to the specific needs of their transplanted specimens. The landscape aesthetic that came to define rock and alpine garden culture, therefore, emerged at a time when the idea of the garden as a “nature preserve” and the concept of ecology gained prominence in scientific discourse.

Though the “wild” aesthetic associated with rock and alpine gardens suggests a critique of anthropocentrism, it also simultaneously masks how the original collection and transplantation of exotic alpines was enabled by the control of territory through European imperialism, as well as the power relations that informed the practices of colonial botanical exploration during this same period. This contradiction, as Richard Grove has established in his book Green Imperialism, is foundational to the discourse of conservationism. As Grove argues, “very little account has ever been taken of the central significance of the colonial experience in the formation of western environmental attitudes and critiques.”[26] “The available evidence shows,” Grove explains, “that the seeds of modern conservationism developed as an integral part of the European encounter with the tropics and with local classifications and interpretations of the natural world and its symbolism.”[27] Questioning anthropocentrism in the context of colonial rock and alpine gardening did not extend to decentring the colonizer’s relationship to indigenous groups or to the non-human world, but rather was focused on conserving the environment in areas under European control to ensure ongoing access to the botanical resources they might yield. Decolonizing the botanic garden in the present, therefore, requires attention to how colonialism has shaped the emergence of discourses related to conservationism, sustainability, and biodiversity, and raises questions about the recent realignment of botanic gardens with these concerns in their current social and scientific mandate.[28]

Planting the Archive in the Garden

While working in the archives at botanic gardens I was conscious of how my research was transforming my experience of visiting the plant collections in their adjacent gardens. Though the archives revealed how botanic gardens’ collections are deeply influenced by colonial botanical exploration, naming, and the collection of exotic plants for display back home, none of this history was referenced in the guided tours or didactic panels that introduced visitors to the contemporary gardens. Although the personal papers and manuscripts of figures such as Ward and Farrer housed in the archives offered many examples of how colonialism has shaped the character of the collections and the design of botanic gardens, little attention is paid to this history in the way the gardens were curated for the public. For example, much of Ward and Farrer’s writing about their plant-hunting expeditions offered autobiographical accounts that position them as autonomous colonial male travellers “discovering” plants in exotic locations—this despite ample evidence that they relied extensively on local communities to help them locate, collect, and preserve their specimens.[29] This blinkered view of Farrer’s plant hunting and garden writing was on display in a series of panels meant to celebrate the centenary of the Rock Garden at the RHS Garden Wisley in 2011. Under the headline “A Rock Garden for £1,350!” didactic panels explain that “[t]he decision to build a rock garden at Wisley [in 1911] was inspired by the writings of the great plant hunter Reginald Farrer in his book My Rock Garden.”

Fig. 1

The installation lauds the “great” influence of Farrer’s plant hunting and garden writing without addressing the colonial context in which he wrote about and collected alpine plants. Wisley’s efforts to engage young visitors around issues related to sustainability and conservationism during their visit to the garden are included on take-out lunch boxes that play on the theme of botanical exploration and plant hunting in an utterly benign fashion. Under a cartoon image of three young children walking though grass, the lunch boxes distributed at the Garden Café promoted the RHS “Garden Explorers” program with the slogan, “[t]he garden is like an adventure playground with lots of fun things to do and discover.” “Be Earth Friendly!” consumers are reminded by a message on the side of the box, “Always use recyclable, sustainable & biodegradable products.”

Fig. 2

Like NYBG in Bloom app, RHS’s “Garden Explorers” program encourages young visitors to experience the garden through the frame of anti-conquest, invoking the narrative of exploration as innocent of power relations. As an isolated example, this reading of the program might seem overly harsh; however, when taken along with these other instances of how contemporary botanic gardens mediate the public’s perception of their collections, it becomes apparent that the discourse of anti-conquest remains fundamental to the stories botanic gardens tell the public about their mandate. As Despard has argued about the MBG,

I think it is important to take seriously the fact that botanical gardens have historically been so conducive to the aims of colonization. While the social and political functioning of a garden such as the MBG today should not be seen as wholly continuous with the legacy of a garden such as Kew, it is also not wholly discontinuous.[30]

While other public institutions such as museums and galleries grapple with recent calls to decolonize their collections by investigating the colonial attitudes that informed practices of acquiring and exhibiting their collections, botanic gardens remain relatively uninvolved in this process of self-reflection.[31] More recently, however, Alexandre Antonelli, Director of Science at the RBG Kew, has called for botanical gardens to decolonize. “For hundreds of years,” Antonelli writes,

rich countries in the north have exploited natural resources and human knowledge in the south. Colonial botanists would embark on dangerous expeditions in the name of science but were ultimately tasked with finding economically profitable plants. Much of Kew’s work in the 19th century focused on the movement of such plants around the British Empire, which means we too have a legacy that is deeply rooted in colonialism.[32]

More often than not, botanic gardens tend to present their plant collections and gardens devoid of reference to the history of colonialism, adopt a paternalistic attitude towards the environment, and thus deflect a serious examination of how this might continue to shape visitors’ perceptions of issues such as sustainability and environmental justice in response to anthropogenic climate change.

As John Dixon Hunt has argued, a garden is not “objective physical surroundings […] but involves the inscription on that site of how an individual or a society conceives of its environment.”[33] Often inflected with “conservative ‘political and cultural motives’,” gardens have been designed to “establish continuity with a suitable historical past.”[34] Botanic gardens can also be understood as “anachronistic spaces,” a term used by Anne McClintok to describe “a space marked as non-coeval with the world around it, and whose implication in modernity is suppressed.”[35] Spaces that are defined by “a blended aura of colonial time and prehuman natural time,”[36] “a modern nature in denial of its modernity,”[37] botanic gardens are coded by the “labour-intensive production of labour’s illusory absence.”[38]

It is this contradictory pull within design practices at botanic gardens, and rock and alpine gardens in particular, that the Alpine Garden MisGuide seeks to explore. “Landscape,” as Jill Casid argues, needs not be understood as just “a technique for the production of imperial power but also as a vital but overlooked medium and ground of contention for countercolonial strategies.”[39] While botanic gardens have their origins in colonial practices of cataloguing and displaying the empire in the imperial centre, the colonial “need and desire to make copies of its ideal self” while also “grasp[ing] and represent[ing] alien flora,” Casid explains, “menaced colonial authority from within its own representational system.”[40] By placing the visual, auditory, and written experience of the archive in tension with the visitor’s embodied experience of the garden, the Alpine Garden MisGuide disrupts the “smooth optics of tourism” associated with popular garden culture[41] and redirects the visitor’s attention to the garden’s ambivalent and anxious relationship to imperial knowledge and authority.

Counter-Landscaping with Locative Narratives

Despite the current lack of innovative mobile apps for critically curating the history of botanic gardens, creators and theorists of locative media working in other contexts have been engaged in charting an ambitious agenda for using mobile media to disrupt habituated ways of seeing and experiencing space and place. Anders Sundnes Løvlie defines locative media as “mobile media applications which are sensitive to the user’s physical location—[and] make it possible to connect texts with places.”[42] On the surface, this is essentially what museum guides do—they are hand-held books or MP3 players that link “data” or information to place in “useful” or practical ways. It is the expectation that mobile media will only provide didactic information that the Alpine Garden MisGuide subverts; instead it mimics the “ordered apparatus” associated with museum apps without sharing their transparent view of knowledge or didactic pedagogy. It challenges the idea of objective knowledge of the botanic garden and defamiliarizes ways of looking and moving through its collection. The app foregrounds the embodied quality of the user’s perception by linking the content and function of the locative app to specific locations in the garden using GPS, and in the process, draws attention to the entanglement of alpine garden design and colonial knowledge-making projects such as plant hunting.

At the entrance of the Jardin alpin at the MBG, signs invite garden visitors to download the app and “explore the relationship between the history of alpine garden design and colonial plant hunting.”

Fig. 3

Alpine Garden MisGuide information panel, Montreal Botanical Garden, 26 May 2015.

As users open the app, they are presented with an animated “field notebook” (complete with turning pages, scrolling text, and a sketch of a distant mountain range cloaked in animated drifting clouds), and greeted by the voice of a narrator who invites them to embark on a “plant-hunting expedition.”[43] “Welcome to the Alpine Garden MisGuide,” states the narrator,

You may be wondering what I mean by calling this a “misguide.” Well, for one thing, it won’t guide you through the garden in the way you might expect. In fact, even if you have visited the Alpine Garden before, I hope the MisGuide will help you see and experience the garden in a new way. Did you ever wonder how the garden and plants got here in the first place? I’m not just talking about the history of this garden, but alpine gardens in general. This MisGuide asks you to consider how alpine gardens have been shaped by the history of colonialism, botanical exploration, and writing about rock and alpine gardens in the first half of the twenty-first century.

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

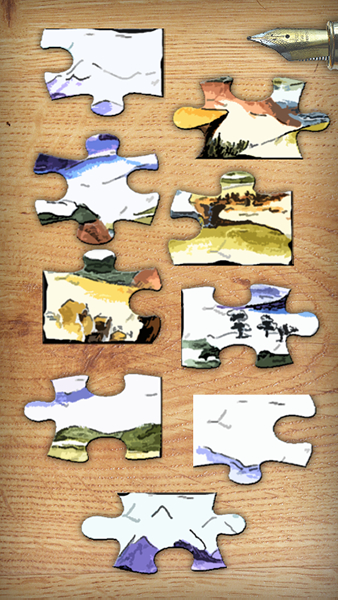

The narrator quickly explains how to use the GPS-enabled “compass screen” to locate nine different QR codes installed throughout the garden, how to use the in-app scanner (disguised as a Kodak Brownie) to scan the QR codes, and how to activate the content linked to images of jigsaw puzzle pieces that appear on the “desktop screen” after a QR code is scanned.

Fig. 6

Alpine Garden MisGuide collectible jigsaw puzzle pieces.

Fig. 7

By scanning the codes, the user “collects” nine different jigsaw puzzle pieces that, when touched, link the user to fictitious expedition paintings of plant specimens. Each plant specimen is surrounded by paperclips that link the user to touch-activated sound recordings, images, and texts.

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

This app content introduces users to different historical, autobiographical, and literary texts about alpine plant hunting and garden design meant to deflect the impression of botanic gardens as “anachronistic spaces.” Flowers in the expedition drawings fall away from the screen if touched by the user and reappear in the in-app “herbarium,” a feature meant to remind the user that plant hunting involved the collection and transport of the plants away from the landscapes in which they were found. The images of the gramophone (sound icon), Brownie camera (QR code scanner icon), and pen nib (navigation icon), represent period-specific forms of media used by plant hunters to frame their experience of travel in foreign landscapes in ways that reinscribed colonial authority. Once all nine jigsaw puzzle pieces are collected, they can be assembled to reveal an alpine landscape—the fictitious location where the apps expedition drawings of different plant specimens were created, and a reminder of the “elsewhere” that is always in tension with the collection housed in the botanic garden.

Fig. 10

Fig. 11

Rather than provide didactic information about the types of plants contained in the garden, the Alpine Garden MisGuide redirects garden visitors’ attention to the historical context and power relations that informed the practices of botanical exploration, the cultural attitudes that shaped the aesthetics of rock and alpine garden design, and details of the labour that goes into maintaining the gardens in the present. For example, the chief horticulturalist of the Jardin alpin at the MBG, René Giguère, describes how he trims the large conifers to appear as though their growth has been stunted by high alpine conditions, and explains how the garden’s “mountain stream” (controlled by a hidden tap) is meant to imitate snow-melt from imagined mountains above. The visitor’s combined experience of the app, the garden setting, and the textual and recorded accounts of colonial and postcolonial plant hunting and gardening, work to disrupt the “smooth optics of tourism”[44] associated with contemporary botanic gardens, and instead, makes visible the “absent-presence” of a colonial archive associated with botanical exploration and garden history.

Transitive Reading in the Garden

The Alpine Garden MisGuide is a locative-media experience that is structured to leverage the productive tension between reading and viewing critical, creative, and archival materials in the context of a site-specific installation. The pedagogical opportunities afforded by tying the experience of place to the experience of reading is one that has received much attention by scholars of locative media. The use of locative media in these literary and counter-intuitive ways is now well over a decade old, with interactive audio installations such as Urban Tapestries,[45] [murmur],[46] and textopia,[47] as prominent examples of early artistic uses of the technology. As Brian Greenspan has argued “locative media represents a productive hesitation between literary fiction, documentary, audio-visual installation, and site-specific theatrical performance.” [48] “As cultural practices,” writes Greenspan, “they are located in the everyday sites of commerce and leisure within both natural and built environments, at the crux of the user’s public and private identities.”[49] The Alpine Garden MisGuide enhances this aspect of the digital interface, asking the user to engage in the practice of searching for and collecting QR codes installed at various locations throughout the garden. Though the app encourages the activity of collecting and accessing the content of the “vouchers” while in the garden (“voucher” being the botanical term for pressed flower specimens used to refer to the app content), the user also accumulates the content as a souvenir of the visit, allowing them to review the material outside the garden, thus extending the user’s engagement with the app content beyond the immediate visit to the MBG.

Of course, encouraging reading or engaging with texts outdoors is not new. As Andrew Piper reminds us in his recent study, Book Was There, “by the end of the eighteenth century, reading outdoors was decidedly in vogue.”[50] “In turning outward toward the woods,” Piper writes, “the tree reminded readers of the turn inward into the expanse of human thought. Even at its most experientially poignant (being in nature), reading a book outdoors could serve as a means of accessing no place at all. It served as a space to lose one’s sense of place.”[51] Reading outdoors, Piper explains, brought book lovers together as a community and encouraged the idea of escape to an elsewhere through the book. Despite the performativity associated with locative media, the experience of reading visual and written signs still relies heavily on the idea of being “transported to fictional worlds,” away from one’s immediate context.[52] However, it is this understanding of the experience of reading that the Alpine Garden MisGuide capitalizes on, while at the same time tying the experience of reading and viewing to a particular location in the garden through the search for QR codes. As Greenspan explains, locative media “mobil[izes] printed literature’s traditional mode of decontextualized engagement within a spatial context in ways that often interfere with the performance of place, foregrounding the productive tension between the traditional experience of fictional transportation and new modalities of mobility that constitutes our present medial condition.”[53] Like Greenspan’s StoryTrek[54] (a locative platform he has developed for adapting to any space using GPS tags), the Alpine Garden MisGuide seeks to exploit the “spatial tension between conventionally sedentary modes of literary engagement and more dynamic, continuous and complex models of spatial interaction” that locative technologies allow for in the garden.[55] Thus “where the book was both somewhere and nowhere,” argues Piper, “digital texts by contrast are almost always somewhere and elsewhere.”[56] In other words, though digital texts like the Alpine Garden MisGuide make it harder for us to get lost in the action of reading (when text is anchored to place through things such as GPS or QR codes), those same texts, tied to specific locations in the botanic garden—pull us away from place, in the manner of the book. Moreover, while users can download the app to their iPhones from anywhere in the world, they cannot unlock the content tagged to the botanical drawings without visiting the MBG Alpine Garden to locate and scan the QR codes. “Despite this intensification of place,” Piper explains, “digital reading can also feel like it is happening in many places at once.”[57] In this sense, locative media counters the disembodied, decontextualized experience of viewing or reading material online in stationary ways by forging what Piper describes as “corporal connections […] between what we’ve seen and where we’ve seen it.”[58] A locative narrative like the Alpine Garden MisGuide, therefore, is meant to span the space between the garden and the archive and serve as an electronic palimpsest that relies on a transitive reading experience, “layering reading on top of real space in an interactive way.”[59]

Artistic or non-didactic uses of locative media are productive precisely because they disrupt taken for granted understandings of place and hail the user not for the purpose of replacing one form of transparent knowledge for another, but rather, to produce a “distracted, ambivalent or otherwise divided subject.”[60] In this sense, the Alpine Garden MisGuide’s disruptive power relies on the counter-intuitive gesture of “calling somewhere else to reconnect to where you are”[61]—unlocking a mix of the playful, fictive, as well as actual archival materials to consider in relation to the anachronistic space of the botanic garden. The Alpine Garden MisGuide invites the user to follow a path through the garden, but unlike NYBG in Bloom, rejects the idea of the detached observer who encounters the garden from an innocent vantage point. Instead, the Alpine Garden MisGuide locative narrative implicates the visitor in the botanic garden’s “geo and body-politics of knowledge,” and disrupts the “illusion of neutral, universal knowledge.”[62] The fragmentary, suggestive encounter, the experience of getting lost or misguided along the way, becomes a communicative gesture that clears the space for the botanical garden to come.

Playing on the embodied quality of experience and place-making affordances of locative media, the Alpine Garden MisGuide was developed to curate alpine collections at contemporary botanic gardens in a counter-colonial manner. The app interface functions to make visible the botanic garden’s implication in the history of imperialism and extractive capitalism, as well as raise questions about how this shapes contemporary attitudes towards the environment. Critical to the success of the locative app was the receptiveness of the administration and gardeners at the MBG when approached about testing and eventually installing the app in their Jardin alpin. After many hours spent designing and testing of the platform, creating the artwork, and researching, writing, recording, and assembling materials for the plant hunting-themed locative narrative, the Alpine Garden MisGuide was published on the iTunes Apple Store and was launched for public use in at the MBG in May 2015.[63]

Parties annexes

Biographical note

Jill Didur is Professor in English at Concordia University in Montreal. She is the author of Unsettling Partition: Literature, Gender, Memory (University of Toronto Press, 2006) and co-editor of Global Ecologies and the Environmental Humanities: Postcolonial Approaches (Routledge, 2015). At Concordia, she is a member of the Technoculture Art and Games Research Centre at the Milieux Institute for Art, Culture, and Technology. She is the Principal Investigator of Greening Narrative: Locative Media in Global Environments, a multi-year Insight Grant, funded by SSHRC. Her current research-creation project Global Urban Wilds explores the affordances of locative media for decolonizing settler environmentalism.

Notes

-

[1]

The New York Botanical Garden, NYBG in Bloom, Computer software, Apple App Store, Vers. 1.2, 4 June 2012.

-

[2]

The NYBG in Bloom app acknowledges the sponsorship of Deutsche Bank, an institution founded in 1870 with a mandate to promote foreign trade. That Deutsche Bank would lend its support to a locative narrative that appears to unselfconsciously rehearse a nostalgia for colonial botanical exploits underscores how the challenge of decolonization extends well beyond the realm of botanic gardens.

-

[3]

Rebecca Preston, “‘The Scenery of the Torrid Zone’: Imagined Travels and the Culture of Exotics in Nineteenth-Century British Gardens,” in Felix Driver and David Gilbert (eds.), Imperial Cities: Landscape, Display and Identity, Manchester, UK, Manchester University Press, 2003, p. 195.

-

[4]

Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism, New York, Knopf, 1993, p. 95.

-

[5]

Mary Louise Pratt, Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation, New York, Routledge, 1992, p. 7.

-

[6]

Ibid.

-

[7]

Ibid., p. 60.

-

[8]

Ibid.

-

[9]

L’article n’est pas disponible dans le store canadien : Jill Didur, Alpine Garden MisGuide, computer software, Apple App Store, Vers. 1.0, 22 May 2015, https://itunes.apple.com/ca/app/alpine-garden-misguide/id991874716?mt=8 (accessed 1 November 2020).

-

[10]

Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2011, p. 187.

-

[11]

Lucile Brockway, Science and Colonial Expansion: The Role of the British Royal Botanic Gardens, New Haven, Connecticut, Yale University Press, 2002.

-

[12]

Richard Drayton, Nature’s Government: Science, Imperial Britain and the ‘Improvement’ of the World, New Haven, Connecticut, Yale University Press, 2000.

-

[13]

For a more detailed discussion of the initially precarious relationship of the MBG to the city of Montreal, see Michèle Dagenais, “Le Jardin botanique de Montréal : une responsabilité municipale ?” Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française, vol. 52, no. 1, Summer 1998, p. 3–22, full text available at: https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/haf/1998-v52-n1-haf221/005375ar/ (accessed 1 November 2020).

-

[14]

Erin Despard, “The Dream of ‘la ville fleurie’: A Non-Linear History and Pragmatic Criticism of Public Gardens in Montreal,” doctoral dissertation, Concordia University, 2013, p. 135, full text available at: https://spectrum.library.concordia.ca/977214/ (accessed 1 November 2020).

-

[15]

Henry Teuscher, “Value of a Municipal Botanical Garden,” The Municipal Review of Canada, vol. 39, no. 9, September 1943, p. 6, italics in the original.

-

[16]

Despard, 2013, p. 148.

-

[17]

Ibid., p. 146.

-

[18]

Henry Teuscher, “Program for an Ideal Botanical Garden,” Memoirs of the Montreal Botanical Garden, no. 1, Montreal Botanical Garden, 1940, p. 9, full text available at: http://www2.ville.montreal.qc.ca/jardin/archives/histoire/pub_pdf_en.php?pub_id=43&Depart=0 (accessed 2 February 2021).

-

[19]

Ibid., p. 8–9.

-

[20]

For an excellent overview of the history of British rock and alpine garden culture, see Brent Elliot, Occasional Papers from The RHS Lindley Library: The British Rock Garden in the Twentieth Century, vol. 6, London, Royal Horticultural Society, 2011.

-

[21]

Elsewhere I have written about the colonial attitudes that link British colonialism, plant-hunting, mountaineering, and rock and alpine culture. See Jill Didur, “‘The Perverse Little People of the Hills’: Unearthing Transculturation and Ecology in Reginald Farrer’s Alpine Plant Hunting,” Global Ecologies and the Environmental Humanities: Postcolonial Approaches, in Elizabeth DeLoughrey, Jill Didur, and Anthony Carrigan (eds.), New York, Routledge, 2015, p. 51–72.

-

[22]

William Robinson, The Wild Garden; or, Our Groves & Shrubberies Made Beautiful by the Naturalization of Hardy Exotic Plants: With a Chapter on the Garden of British Wild Flowers, London, J. Murray, 1870, p. xxiv–xxv, italics in the original. It is a testament to the enduring influence of Robinson’s book on popular garden culture that The Wild Garden has been reprinted ten times since it first appeared in 1870, most recently in 2009 (The Wilde Garden, Expanded Edition, Portland, Oregon, Timber Press, 2009).

-

[23]

Ibid., p. 15–16.

-

[24]

Reginald Farrer, My Rock Garden, London, T. C. & E. C. Jack, 1908.

-

[25]

Francis Kingdon Ward, Commonsense Rock Gardening, London, J. Cape, 1948.

-

[26]

Richard Grove, Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism, 1600-1860, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 3.

-

[27]

Ibid.

-

[28]

A 2013 video distributed by Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) promoting Growing the Social Role of Botanic Gardens reproduces a silence around the other role botanic gardens have played in the past—that of contributing to regional economic and environmental disparity through their implication in colonial practices of resource extraction, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c_592TG6eQI (accessed 1 November 2020). For a recent study that explores botanic gardens’ embeddedness in the nation-state and the discourse of modernity, see also Katija Grötzner Neves, Postnormal Conservation: Botanic Gardens and Reordering the Biodiversity Governance, Albany, New York, State University of New York Press, 2019.

-

[29]

For an extensive discussion on the relationship between the archive of colonial plant hunters and the way colonialism shaped botanical exploration in West China and Tibet, see Erik Mueggler, The Paper Road: Archive and Experience in the Botanical Exploration of West China and Tibet, Berkeley, California, University of California Press, 2011.

-

[30]

Despard, 2013, p. 147.

-

[31]

See Kanishk Tharoor, “Museums and Looted Art: The Ethical Dilemma of Preserving World Cultures,” The Guardian, 29 June 2015, full text available at: https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2015/jun/29/museums-looting-art-artefacts-world-culture (accessed 1 November 2020).

-

[32]

Alexandre Antonelli, “Director of Science at Kew: It’s Time to Decolonize Botanical Collections,” The Conversation, 19 June 2020, full text available at: https://theconversation.com/director-of-science-at-kew-its-time-to-decolonise-botanical-collections-141070 (accessed 1 November 2020).

-

[33]

John Dixon Hunt, Greater Perfections: The Practice of Garden Theory, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000, p. 8.

-

[34]

Sarah Phillips-Casteel, Second Arrivals: Landscape and Belonging in Contemporary Writing of the Americas Charlottesville, Virginia, University of Virginia Press, 2007, p. 112.

-

[35]

Nixon, 2011, p. 181.

-

[36]

Ibid.

-

[37]

Ibid., p. 168.

-

[38]

Ibid., p. 166.

-

[39]

Jill Casid, Sowing Empire: Landscape and Colonization, Minneapolis, Minnesota, University of Minnesota Press, 2004, p. 191, italics in the original.

-

[40]

Ibid., p. 192.

-

[41]

Nixon, 2011, p. 182.

-

[42]

Anders Sundnes Løvlie, “Poetic Augmented Reality: Place-Bound Literature in Locative Media,” Proceedings of the 13th International MindTrek Conference “Everyday Life in the Ubiquitous Era,” Tampere, Finland, 30 October 2009, p. 19–28, full text available at: https://www.duo.uio.no/handle/10852/27215 (accessed 1 November 2020).

-

[43]

The website provides a demonstration of the app being used in the garden: http://www.alpinemisguide.org/ (accessed 1 November 2020).

-

[44]

Nixon, 2011, p. 182.

-

[45]

Proboscis, Urban Tapestries / Social Tapestries. Public Authoring and Civil Society in the Wireless City, 2002–2005, http://urbantapestries.net/ (accessed 1 November 2020).

-

[46]

CFC Media Lab [murmur], Toronto, 2003, http://cfccreates.com/productions/76-murmur (accessed 23 February 2021).

-

[47]

Intermedia Lab, textopia, University of Oslo, 2008.

-

[48]

Brian Greenspan, “The New Place of Reading: Locative Media and the Future of Narrative,” DHQ Digital Humanities Quarterly, vol. 5, no. 3, 2011, p. 1, full text available at: http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/5/3/000103/000103.html (accessed 1 November 2020).

-

[49]

Ibid.

-

[50]

Andrew Piper, Book Was There: Reading in Electronic Times, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2012, p. 109.

-

[51]

Ibid., p. 112.

-

[52]

Greenspan, 2011, p. 3.

-

[53]

Ibid., p. 2, italics added.

-

[54]

Brian Greenspan et al., “Storytrek: A System for Itinerant Hypernarrative,” 2006, full text available at: https://carleton.ca/hyperlab/projects/#story (accessed 1 November 2020).

-

[55]

Greenspan, 2011, p. 2.

-

[56]

Piper, 2012, p. 112–113.

-

[57]

Ibid., p. 122.

-

[58]

Ibid., p. 121.

-

[59]

Ibid., p. 123.

-

[60]

Darren Wershler, “Sonic Signage: [murmur], the Refrain, and Territoriality.” Canadian Journal of Communication, vol. 33, no. 3, 2008, p. 415, full text available at: https://www.cjc-online.ca/index.php/journal/article/view/2000 (accessed 1 November 2020).

-

[61]

Ibid.

-

[62]

Laura A. White, “Novel Vision: Seeing the Sunderbans through Amitav Ghosh’s The Hungry Tide,” ISLE, vol. 20, no. 3, Summer 2013, p. 514, full text available at: https://academic.oup.com/isle/article/20/3/513/677386 (accessed 1 November 2020).

-

[63]

In addition to the programming and design work of Ian Arawjo, I wish to also acknowledge Beverley Didur for creating the botanical drawings used for the app’s visual interface, and the research support of Figura Concordia’s le Laboratoire NT2 and the Technoculture Art and Games Research Centre at the Milieux Institute for Art, Culture, and Technology, Concordia University, Montreal. I am also grateful to the administration and gardeners at the Jardin botanique de Montréal for supporting this project throughout its development, especially René Giguère, chief horticulturalist in the Jardin alpin at the Montreal Botanical Garden. This research and the creation of the Alpine Garden Misguide is funded by the “Greening Narrative: Locative Media in Global Environments” SSHRC Insight Grant.

Liste des figures

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

Fig. 5

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

Fig. 11