Résumés

Abstract

Roxham, a creation by Canadian photographer Michel Huneault, produced by the National Film Board (NFB), is a virtual reality project that gathers a series of 33 photographs documenting 180 irregular migrant border-crossing attempts between February and August 2017 at Roxham Road, on the Canada-US border. In order to preserve the identities of the border-crossers, the photographer shows the migrant figures in silhouette, their bodies collaged in composite images of textiles taken by Huneault during the 2015 migrant crisis in Europe. The palimpsestic layering of fabrics and voices on a three-dimensional map, which the virtual reality device allows, underscores the confusion at the border. The ontological and epistemological indeterminacy that results puts into question the representation of the border. With its emphasis on the visual, the aural, the sense of touch as well as its interactive dimension, Roxham seeks to make the experience of human beings at the border more authentic and more real, while underscoring its fundamental opacity.

Résumé

Roxham, une création du photographe canadien Michel Huneault, produite par l’Office national du film (ONF), est un projet de réalité virtuelle rassemblant une série de 33 photographies documentant 180 passages irréguliers de migrants sur le chemin Roxham, à la frontière entre le Canada et les États-Unis, entre février et août 2017. Afin de préserver les identités de ces passeurs de frontières, le photographe fait le choix du photocollage et recouvre les silhouettes des migrants de photographies de matières textiles prises en Europe lors de la crise migratoire de 2015. La superposition des couches de textiles et des voix, sur fond de carte en trois dimensions, que la réalité virtuelle autorise à la manière d’un palimpseste, souligne la confusion qui règne à la frontière. L’incertitude ontologique et épistémologique qui en découle met en question la représentation de la frontière. Dans Roxham, l’accent mis sur les sens de la vue, de l’ouïe et du toucher ainsi que la dimension interactive du projet cherchent à rendre l’expérience d’êtres humains traversant la frontière plus authentique et plus réelle, tout en en soulignant l’opacité.

Corps de l’article

Since 2016, the number of asylum claims processed by the Canadian immigration services has risen sharply from approximately 16,000 asylum claims a year in 2015 to over 55,000 in 2018.[1] This rapid increase has been variously interpreted as a consequence of US President Donald Trump's anti-immigration rhetoric,[2] a manifestation of the global refugee crisis and of the idea, real or imagined, that Canada takes better care of its immigrants and that asylum seekers stand a better chance North of the US border. It has also been blamed, by its detractors, on Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s #WelcomeToCanada tweet[3] in January 2017 and on an alleged loophole in the Safe Third Country Agreement between the governments of Canada and the United States, which is cited as encouraging migrants from the United States to cross irregularly into Canada in order to become eligible asylum claimants.

The Safe Third Country Agreement implemented in 2004 provides that “refugee claimants are required to request refugee protection in the first safe country they arrive in.”[4] By virtue of this agreement, migrants whose first port of entry is the United States are barred from seeking to regularize their refugee status in Canada and are returned to the United States when intercepted at Canadian official border ports. However, under the Canadian Immigration and Refugee Protection Act,[5] signed in 2001, asylum seekers crossing at places other than official border checkpoints may enter the country and apply for refugee status, thereby exploiting what is thought of as a loophole in the Safe Third Country Agreement.[6] It is a matter of political and legal dispute as to whether these crossings should be termed “irregular” or “illegal.”[7] Technically, it is not an offense under Canada’s Criminal Code for migrants to cross outside of official checkpoints (although the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act does require one to report “without delay”[8] at the nearest official port of entry), and potential charges for unlawfully crossing the border under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act are stayed if the claimant obtains refugee status. Border crossing is therefore not illegal, in and of itself, as long as the person is in the process of claiming refugee status. The term “irregular” rather than “illegal” is preferred by government officials, refugee organizations, and lawmakers to describe the act of crossing the border outside of official ports because of the imprecise and pejorative overtones carried by the term “illegal.”

The number of migrants and the perceived illegality of border crossing at Roxham Road in the province of Quebec have triggered a political crisis in Canada, becoming a source of divide between the Liberal and Conservative parties at the federal and provincial levels and fueling the anti-immigration rhetoric of nationalist movements such as the Canadian Patriot. Meanwhile, those whose refugee claims are not granted—about 45%—face deportation.[9]

In 2017 and 2018, over half of the refugee claimants in Canada had entered the country through unofficial border locations,[10] including Roxham Road. Situated in Hemmingford, Quebec on the Canada-US border across from Champlain, in the state of New York, Roxham Road, once perceived as a quiet country road, has become an unofficial crossing point for migrants seeking asylum in Canada. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) initially set up a makeshift border-crossing area about half-way between the Lacolle border station, Route 202, and the Mooers, New York state, border crossing along Hemmingford Road in order to intercept irregular crossers before handing them over to the nearest Canadian immigration services. Owing to the high number of border crossers—about 20,000 in 2017 alone[11]—a new permanent structure has recently been built at the Roxham junction for the initial processing of border-crossers by the RCMP. This includes security checks, fingerprinting, criminal checks, and health checks.[12] Those who make it through security screening are driven by the RCMP to the nearest Canadian immigration services where they may file a refugee claim with the Immigration and Refugee Board.

This article proposes a close reading of the virtual reality installation entitled Roxham (Huneault, 2017). This creation by Canadian photographer Michel Huneault, produced by the National Film Board (NFB), is a virtual reality project described as offering “an immersive experience based on 32 true stories,”[13] and can be viewed online on the NFB website.[14] The project gathers a series of 33 photographs documenting 180 migrant border-crossing attempts at Roxham Road between February and August 2017. At festivals and exhibitions where the virtual reality version is presented, viewers are invited to wear an Occulus Rift mask for a complete immersion. In the physical version of the exhibition,[15] Huneault presents 16 photographs accompanied by a 12-minute binaural soundtrack. In this version, there is no narrative voice, the viewer is therefore less guided in her experience of the work. Some of the photographs in the Roxham series have also appeared in the press.[16]

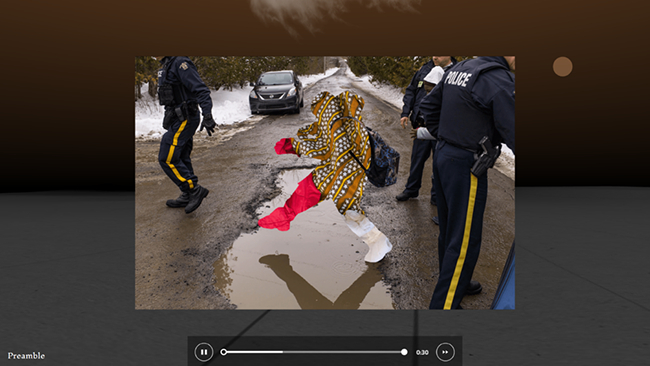

In the virtual reality installation, the spectator, equipped with a mouse and headphones,[17] faces a screen that shows a three-dimensional map of the border area (see Fig. 1). She can click on the silhouettes that appear in the background (see Fig. 2), thus bringing up the photograph of that silhouette to the foreground while setting off the soundtrack associated with it (see Fig. 3). The migrants in the photographs are seen in the act of approaching the border, sometimes actually crossing it, and at other times being taken into custody by the RCMP officers present on site. In order to preserve their identities and in accordance with Quebec legislation regarding image reproduction rights,[18] Huneault shows the migrant figures in silhouette, their bodies collaged in composite images of textiles that he had taken during the 2015 migrant crisis in Europe (see Fig. 4). Each scene, or photograph, is associated with a binaural soundtrack of the exchanges at the border between the migrants and the police agents, dispersedly mingled with other sounds such as the clicking of the camera.[19] The succession of photographs forms a narrative, broken down into seven chapters. These stories and their titles constitute a narrative of hardship, determination, misunderstanding, apology, uncertainty, and sometimes relief on the part of the migrants. The police officers, on the other hand, appear to be both threatening and comforting, humane and aloof as they warn the migrants against crossing and then take them into custody before driving them away to the immigration services.

Fig. 1

Screenshot from Roxham, Michel Huneault, 2017, National Film Board website, https://www.nfb.ca/interactive/roxham/ (accessed 30 June 2020).

Fig. 2

Screenshot from Roxham, Michel Huneault, 2017, National Film Board website, https://www.nfb.ca/interactive/roxham/ (accessed 30 June 2020).

Fig. 3

Screenshot from Roxham, Michel Huneault, 2017, National Film Board website, https://www.nfb.ca/interactive/roxham/ (accessed 30 June 2020).

Fig. 4

Screenshot from Roxham, Michel Huneault, 2017, National Film Board website, https://www.nfb.ca/interactive/roxham/ (accessed 30 June 2020).

Border aesthetics remind us, as Stephen Wolfe and Mireille Rosello have pointed out, that a border must be sensed, whether visually or otherwise, in order to exist.[20] At the heart of Roxham is a multisensory experience of what crossing the border entails physically, emotionally, and visually. In order to appeal to our senses, virtual reality in Roxham resorts to hypermediacy and interactivity. The hypermediacy developed by Huneault, with its complex layering of images and sounds, entails the multiplication and overlapping of various media such as photographic collage, soundtracks, and three-dimensional mapping. The emphasis on the senses of sight, hearing, and touch contributes to this immersive experience and offers the promise of an authentic “border experience.” I argue that the choices of hypermediacy and photocollage made by Huneault in Roxham, in order to convey this “border experience,” essentially question the politics of representation at the border. While the sense of the “authentic” requires the deployment of complex representational and narrative strategies, this in turn generates a sense of confusion and opacity that points to the epistemological uncertainty at the border. The generic tension between the documentary quality of the series of photographs and their fictional potential suggests that only a reinvention of the documentary genre, which invites all protagonists to question where they stand at the border, whether photographer, border-crosser, or spectator, can contribute to what T. J. Demos has termed a new “politics of truth.”[21]

In their book entitled Remediation: Understanding New Media,[22] David J. Bolter and Richard A. Grusin posit that hypermediacy generates epistemological opacity, on the one hand, and a sense of psychological authenticity, on the other. The complex staging of the senses of touch and hearing at the border, through various instances of audio and visual remediation, reveal the power relations at work, the emotions that are played out, the violence of the encounter while refusing to offer a narrative in the form of a coherent whole. The staging devices chosen by the photographer thus suggest the ontological indeterminacy at the border—be it that of the migrant, the photographer, or the spectator. This indeterminacy is further implied by Huneault’s decision to photocollage, which situates the representation of the border-crossers at the intersection between fiction and reality, hypervisbility and invisibility. This visual strategy creates a distance between the spectator and the narrative it seeks to uncover. Ensues from the collaging technique a substraction of sorts of the migrant bodies from the borderscape, which allows what Jacques Rancière has termed a “reconfigur[ation] [of] the landscape of what can be seen and can be thought.”[23] This implies in turn a reflection on the politics of documentary. T. J. Demos’ book The Migrant Image: The Art and Politics of Documentary during Global Crisis has been a valuable source of reflection to discuss the problems posed in documentary practice by the migrant image as he sets to answer how it “is […] possible to represent artistically life that is severed from representation politically.”[24] Ariella Azoulay’s work on the “civil contract of photography”[25] further questions the ethics and the representability of the migrant in situations of distress. The idea she defends that photography can productively be understood as a partnership between equal citizens, that of the photographer, the photographed, and the spectator will guide my reflection on how Roxham makes possible new types of positioning at the border, and therefore a new understanding of the issue of irregular border crossing.

Hypermediacy and the Sensing of the “Border Experience”

Hypermediacy in Roxham finds expression in the re-mediation of various images: the Google map, journalistic photographs of border-crossers, cinematic narratives of migrant stories, or CCTV camera images. In an interview with Sophie Bertrand, Huneault presents his work as a reflection around the discrepancy he felt between “the many images [he had seen] of RCMP agents taking migrants by the hand”[26] and what he had actually witnessed himself the first time he went to Roxham Road. On that day, he tells us, a Nigerian woman, rebuffed by the RCMP, never dared take the step to the Canadian side and was driven away by a US border agent to an uncertain fate (see Fig. 4). The process of remediation constitutes a challenge to the validity or the truth value of images in various media and invites the spectator to look at border-crossers in new, more authentic, ways.

As Bolter and Grusin have shown in their work on hypermediacy and strategies of remediation,[27] the supposed virtue of each new medium is to repair the inadequacies of the medium it supersedes, the inadequacy of which is generally expressed in terms of a lack of immediacy.[28] Epistemologically, immediacy implies transparency, understood as “the absence of mediation or representation”; psychologically, it “names the viewer's feeling that the medium has disappeared [...], a feeling that his experience is therefore authentic.”[29] Whereas the authors associate hypermediacy with “opacity—the fact that knowledge of the world [psychologically] comes to us through media”[30]—they insist “that the experience of the medium is itself an experience of the real.”[31] Whereas the logics of immediacy and hypermediacy oppose each other epistemologically, the one striving for transparency, the other offering opacity, they converge psychologically in their appeal to authenticity. For Bolter and Grusin, “the logic of immediacy dictates that the medium itself should disappear and leave us in the presence of the thing represented,”[32] that we might sense the event directly. Paradoxically, this immediacy requires hypermediacy in order to “reproduce the rich sensorium of human experience.”[33] How then does Roxham invite the spectator to sense the border?

The sense of touch in Roxham appears both through the action of the spectator and through the visual spectacle of the RCMP officers conducting bodily searches of the migrants (see Fig. 3). The virtual reality installation offers the possibility for the spectator to navigate the border with her mouse at a 360-degree angle. This allows an interactive experience of the border as the spectator is called upon to click on figures appearing on a three-dimensional map of the border area. The sense of touch is visually materialized by way of a colour dot (see Fig. 1 to 4). Clicking then implies that the spectator is brushing the silhouettes with her hand, thus suggesting a great proximity. But the act of clicking could also entail the shooting of an enemy, as in a video game, or the spotting of an intruder trespassing the border, as in an act of surveillance. The sense of touch can be associated with more confident and positive gestures in the scenes where the RCMP are seen holding out a helping hand to the migrants. Permitting the spectator to “touch” the migrants or showing the physical contact at the border, points to the rich sensorium of experience at the border. It also underscores the complex web of relations at the border, where the migrant tends to appear as the passive object of this quasi-physical contact even though the installation presented by Huneault does not preclude other types of positioning, which will be discussed later.

The aural aspects of the installation, whether the soundtrack itself or the oral narrative unfolding, further convey an experience of the border as something rather complex, if not confusing. The patchwork of voices in the soundtrack interweaves the narrator/photographer’s voiceover, the voices of the border officers on duty as well as those of the migrants themselves. Other sounds are heard in the background adding to a sense of realism/authenticity: coughing, car doors being opened and closed, voices coming from the walkie-talkies, the sounds of feet shuffling around, of jackets being zipped up, of birds, the clicking of the camera, and metallic noises that seem unrelated to the scene. Each story/photograph has its voice and gives flesh to the bodies pictured by assigning them with a tone (mostly anxious, apologetic, or just factual), a nationality, a language, a gender, and/or an age. As spectator, one hears, or overhears, the exchanges between the agents and the border-crossers, with the latter mostly asking the questions and the former in the position of owing answers. The interactions are very repetitive, often simple, fragmentary, mixing the normative language of the law and the terms that the migrants can muster in French or English. The general sense that emerges is one of misunderstanding and cacophony. The voices give meaning to migrant stories, individualize trajectories, and add depth of narrative. But they also convey the idea that the border, even as it is only a convention, an arbitrary or imaginary line, assigns roles that reveal the asymmetrical power of the migrant and the border agent. The fragmentary nature of these found stories at the border draws the spectator’s attention to the absence of a coherent narrative or to the difficulty of making sense of the border.

The immersive element of the virtual reality project, with its emphasis on the senses—seeing, touching, and hearing in particular—seeks to make the experience of the border-crossers more authentic and more real for the spectator. The immersive quality made possible by virtual reality provides a psychological sense of authenticity. Epistemologically, however, the layering of sound and image, the interactive possibilities offered by the mouse, the multiple appeals to our senses also aim at revealing the complexity of relations at the border. They require that one makes sense of the border beyond the simple dichotomy of the inside and the outside, citizen and non-citizen, spectator and actor. Therefore, the emphasis on the senses can be seen as conveying a vision of the border not as a simple given, not as “natural,” but as a site that essentially questions the ways in which we make sense, or understand, the world around us and the border in particular. In this respect, Walter Mignolo's work on decoloniality encourages us to view the border epistemologically as a site of enunciation, not so much as a theme but as a way of knowing that places the emphasis on enunciation, rather than representation, and on sensing from the perspective of the border, rather than just sensing at the border.[34]

Thinking about Roxham in terms of hypermediacy has pointed to the fact that representing border relations in all their complexity is attempted but illusory to a certain point, because hypermediacy implies a multiplication of filters (each media acting as an additional filter), and thus manufactures “opacity.”[35] If this is the case, how to interpret more specifically the visual embedding process at work in the virtual reality installation? How do the photocollaged bodies of the migrants critically engage with the “border experience”?

Migrant Stories at the Crossroads between Reality and Fiction

The migrants walking down the footpath and stepping over the ditch to Roxham Road on the Canadian side of the border are committing an act with potential life-altering consequences as some of them may be granted asylum or obtain residency permits while others incur the risk of being deported back to their countries of origin. Still others find themselves in unresolved administrative situations where they cannot be deported because they come from countries deemed unsafe by the government of Canada without, however, qualifying for asylum. The physicality of the act of border crossing is thus traversed by this paradox between the triviality of the physical crossing of the ditch and the significance of the act in the lives of the border-crossers.

As noted above, the silhouettes of the border-crossers are digitally collaged with Huneault’s photographs of textiles and various fabrics. The collage acts as a form of inscription on the migrants’ bodies of the history of migration. This palimpsestic form that interweaves present and past migration crises expresses a new cartography of an old phenomenon. It suggests that the stories of border-crossers are multilayered and complex and that the events occurring at Roxham Road need to be understood within a more global context of (in)voluntary displacement.

Visually speaking, the installation offers a strong contrast between the three-dimensional digital reconstruction of the border in scales of gray and the colourful silhouettes of the border-crossers. The very bright colours of the collage render the migrant bodies hypervisible against the grey background of the virtual reality installation and in the photographs themselves. Although the body of the migrant is thus made to stand out, the immediate effect of the digital collage is to erase the migrants’ “real” bodies and features. Some of the collages in fact suggest that the migrant has merged with the background (see Fig. 5). The photographer thus protects the migrants’ identities while insisting on the body as the site where the narrative/challenge of border crossing is inscribed. In this sense, the body is made to bear the physical and psychological marks of the hardships of migration at the crossroad between fiction and reality where a real story—that of irregular border-crossing attempts—is visually fictionalized by resorting to photocollage.

Fig. 5

Screenshot from Roxham, Michel Huneault, 2017, National Film Board website, https://www.nfb.ca/interactive/roxham/ (accessed 30 June 2020).

Fig. 6

Screenshot from Roxham, Michel Huneault, 2017, National Film Board website, https://www.nfb.ca/interactive/roxham/ (accessed 30 June 2020).

The collage, moreover, has the effect of flattening the bodies and thereby reducing them to pieces of clothing hanging from a line. The migrants’ figures thus become reminiscent of disembodied figures haunting the landscape, subjected to unexpected events along the way. This is suggested in the child’s silhouette seen leaping over a large puddle of water (see Fig. 6). These silhouettes, whether metaphorically or actually in a state of suspension, appear as bodies unpinned from “their” places,[36] thus questioning what it means to be at the border. The suspension of bodies further suggests a suspension in time and echoes the double process of “im/mobility”[37] characteristic of migrant journeys, which go through phases of travel as well as long episodes of waiting. The migrant silhouette made hyperpresent through the choice of photocollage emphasizes the physicality, and very concrete reality, of the border-crossing experience and at the same time underscores the evanescent character of the migrant. This paradox embodies the tension between presence and absence, between the hypervisibility of asylum seekers in the media and the invisibility of the refugee, stateless, illegal migrant as they are deprived of political representation and of the rights of political participation in the public sphere.

The tension between the real and the fictive in the narration of border transgression in Roxham likewise expresses the ambivalence of the migratory process as both a period marked by uncertainties and hardships, but also by the dreams and hopes of a better life. These hopes are conveyed by the stars on the fabric covering the leaping child in Figure 6 or by the words on another child’s shopping bag that read: “Be Happy. Dream big. Imagine. Work hard. Play hard. Reach for the STARS” (see Fig. 7). If migration is triggered by hope in a more promising future, it involves down-to-earth strategies of risk-taking such as this exchange between a migrant in the act of crossing and a police officer suggests:

RCMP: “You can’t cross here, Sir, it’s illegal.”

Migrant: “I know that, I know that. I don’t care. Sorry.”

Roxham thus suggests that understanding migrant mobility cannot be reduced to the study of push and pull factors or statistical data, but should seek to integrate the large specter of emotions, reasons, deliberate strategies deployed by migrants at the border.

Fig. 7

Screenshot from Roxham, Michel Huneault, 2017, National Film Board website, https://www.nfb.ca/interactive/roxham/ (accessed 30 June 2020).

The contrast between the dark uniforms worn by the RCMP officers and the carnivalesque attire of the migrants further draws attention to the tension between the real and the fictional, on the one hand, and to the power relations at play at the border, on the other. Contrary to the migrant faces, which remain collaged throughout the installation, the agents’ features are plainly visible, although rarely shown frontally. The homogeneity in appearance imposed by the RCMP uniforms locates the representation of the agents at the level of the purely abstract embodiment of law and order. The migrant bodies, although fictionalized, nevertheless constitute the site of concrete police work: they are asked to raise their hands, searched, and eventually handcuffed. Even as it is regulated by the law, the physicality and the potential violence of border crossing is emphasized by the hypervisibility of the migrant silhouettes and by the exchanges heard in the soundtrack. One RCMP, for example, is heard asking a migrant: “Do you have anything that could harm me? Bombs? Weapons?” Without seeking to trivialize the violence of the border-crossing experience, the narrative in Roxham refuses the simplicity of news reports assigning the migrant and the RCMP highly circumscribed roles. The contrast between the norm and the carnivalesque thus speaks for complex encounters at the border between fiction and reality, between the potentially threatening physical presence and the metaphorical absence of the migrant. These carnivalesque silhouettes at the border are evocative of the barbarian hordes in The Tartar Steppe by Dino Buzzati[38] rumored to live beyond the desert and symbolic of humanity’s fears and illusions in times of change. They underline the imaginative potential of border narratives as opposed to the statistical and administrative narrative, where the border also needs to be understood as plural and as part of larger histories and processes, rather than limit itself to a rhetoric of “crisis.”

At the end of the virtual reality installation, the photographer’s narrative voiceover is heard saying that “standing across the border, a changing world comes toward me.” He can also be heard saying: “Even I don’t know where to stand.” The play between reality and fiction allowed by the photocollage and the choice of hypermediacy serve to express the difficulty sensed by the migrants, the photographer, and the spectator in positioning themselves within this narrative of a changing world. Because Roxham Road constitutes an unofficial point of passage, it underscores the problem of positioning in space, of locating the inside and the outside, and more generally of the confusion at the heart of the “border experience.” The lexical and semantic confusion in the way of defining the act of border crossing as either “irregular” or “illegal” is an instance of this. Huneault’s virtual reality installation sees Roxham Road as a privileged site for the narration of border crossing precisely because it puts to question the old certainties about the inside/outside divide, about difference and sameness, citizen and non-citizen. This approach debunks the idea of a metanarrative or the “natural” logic of an unproblematic border, thereby contributing to what Rancière has named a new “cartography of the sensible”[39] where the marginal acquires visibility, the victim becomes an actor, the carnivalesque reveals the limits of the normalized vision of the border. It thus seeks to make sense of the power relations at the border by relocating these categories into an alternative border narrative. By emphasizing the tension between fiction and reality, this new cartography both reveals and hides what it means to be at the border. Roxham thus confronts the spectator with the fundamental opacity of the border, which in turn leads us to question the very possibility of documentary representation at the border.

Surveillance Photographed or Photographic Surveillance? Positioning Oneself at the Border

Michel Huneault defines his work at the crossroads between the realistic pursuits of “documentary photography,” on the one hand, and the “concerns of contemporary visual art”[40] on the other. A classic definition of the documentary approach such as that proposed by Beaumont Newhall in 1938 emphasizes the idea that documentary photographs are “simple” and “straightforward” without “retouching of any kind,”[41] that they offer themselves as objective and “sociological” in purpose.[42] Although documentary photography remains associated with a transparent (i.e. non-mediated) representation of reality, most definitions of documentary photography today emphasize its hybrid nature,[43] at the intersection between the fictive and the real. Demos insists on the multifarious strategies deployed by documentarians to photograph—and sometimes not—migrants in zones of conflict. If, according to him, the quest for “truth” remains at the heart of the documentary project, it should not be understood as a “truthful doubling of facts,” but rather “a process of unraveling, exploring, questioning, probing, analyzing, and diagnosing a search for truth.”[44]

Demos resorts to Giorgio Agamben’s concept of the “bare life”[45] to describe the migrant condition and reminds his readers that documentary practice is fully entrenched in the relations of power that it appears to reveal. Hence, documentary representation can serve the powerful as it seeks to show the powerless: “when it does take on a relation to bare life, [documentary representation] often serves the interests of the state.”[46] If photography is aligned with biopower, as Demos contends, then it is to be understood from “within ever new and expanding surveillance systems, operat[ing] as judicial and forensic evidence, where ‘truth’ and ‘objectivity’ live on through their continued institutional and legal validation.”[47] The notion that “photography is an apparatus of power”[48] is also central to Azoulay’s discussion of the civil contract of photography. According to Azoulay, vulnerable populations such as refugees and migrants are easily exposed to the violence of the photographic act, especially of the “journalistic kind, which coerces and confines them to a passive, unprotected position.”[49] As a form of resistance to the power of the state, she proposes to envisage photography as a “partnership of governed persons”[50] that includes the photographed, the photographer, and the spectator. Within this citizenry of photography all partners are equal whatever their status in civil life, and therefore escape the power of the state to assign citizenship to some and to exclude others.[51] If the civil contract of photography is “indifferent to the question of whether or not the injured persons who are photographed are citizens ‘of’ a state,”[52] does it then liberate its partners from the violence of the photographic act? Documentary photography at/of the border—as an object of governmental surveillance par excellence—is well-positioned to draw our attention to the politics of documentary. To what extent, then, does Huneault’s documentation of the border at Roxham Road escape the logics of surveillance? With its promise of an “immersive experience”—selling the aesthetic pleasure of witnessing, at least in the imagination, the drama of border-crossers’ lives—the Roxham experiment in virtual reality poses real questions in terms of what documentary representation can achieve. I address this by exploring the ways in which the various partners of the citizenry of photography position themselves within the economy of relations that defines the civil contract of photography.

In the introduction to the virtual reality installation, Huneault clearly presents the choice of photocollaging the migrant silhouettes as a form of protection against the injuries of photographic documentation. The mise en abyme of the photographic act moreover serves to draw the spectator’s attention to the danger of “slipping into” an act of surveillance. The presence of video cameras in the three-dimensional representation of the landscape, the appearance of a photographer in the photograph of the Nigerian woman (see Fig. 4), the omnipresence of the photographer’s narrative voice, and the constant clicking of the camera heard in the soundtrack all converge to highlight the moment of border crossing as one of “picture-taking.” The spectator herself partakes in the act whereby clicking on a migrant figure opens a new window/photograph onto the backdrop of the three-dimensional landscape. By creating a telescopic vision of the border, the window/photograph gives the spectator the sense, or the illusion, that the magnified image will help deepen her knowledge of the border-crosser’s experience.[53] As the window is seen to offer a better insight of the border-crossing process, however, its surface can also be understood as reflecting the spectator’s image of herself at the border.[54] By returning a reflection of herself to the spectator, the window reminds her that she is engaged in an act of “picture-taking”—that carries with it the potential of participating in the act of surveillance at the border. The gesture of clicking on the migrant figure is therefore a potentially violent one—one that threatens to consume the migrant figure through the desire to “experience” what she goes through at the border. The window, like the border, then separates, divides, and creates a distance which underscores the unknowability of the border, but also leads to a re-examination of how the spectator is called upon to position herself at the border.

Within the civil contract of photography, Azoulay seeks to move away from an “ethics of seeing” associated with aesthetic judgement and towards an “ethics of spectatorship” that emphasizes the spectator’s “responsibility to what is visible.”[55] The collaged silhouettes in Roxham prevent the spectator from the “gesture of identification, ‘this is X,’ [which],” according to Azoulay, “homogenizes the plurality from which a photograph is made and unifies it in a stable image, creating the illusion that we are facing a closed unit of visual information.”[56] The impossibility of identification thus undermines the naturalized social practices at the border, such as presenting one's passport as a proof of identity and the very idea that identity is a simple given with a stable meaning. The great diversity in the colours and types of fabrics further conveys a sense of the plurality of identities. The civil gaze then, in that it expresses the plurality of relations between the citizens of photography, is no longer predetermined by the borders within which it exists. Hence, the spectator’s gaze is liberated from the constraints of bordering that tend to make it unidirectional, and navigates freely from one side of the border to the other, beyond the bordering categories of citizen-non-citizen, inside-outside, etc.

As the spectator is prevented from identifying specific individuals in the series of photographs, what is effaced then is the image of the referent as we would expect it to appear in a journalistic photograph: the cliché of the border-crosser. In this way, the photocollaged silhouettes in Roxham summon images of migrants that the spectator has in mind (documentary images taken by photographers such as Huneault himself, images seen on the Internet, on television, or in other media), in lieu of the referent itself. Because the Roxham border “crisis” was largely mediatized, the spectator may be drawn, more or less consciously, into a game whereby she seeks to recognize in the figure of the migrant other images of similar situations. If one returns to Azoulay’s distinction between the “ethics of seeing” and the “ethics of spectatorship,” this game the spectator is involved in may restrict itself to merely questioning “the extent to which the photograph succeeds in arousing a desired effect or experience,”[57] aligning it with an “ethics of seeing.” An ethics of spectatorship, on the other hand, requires the spectator not simply to be addressed, but to posit herself as the addressee of the photograph.”[58] The ethics of spectatorship thus engages the spectator’s responsibility to the citizenry of photography. This could find expression, for example, in the realization that by impressing images onto the borderscape canvas the spectator has herself become an actor in a bordering process.

If, according to Azoulay, “the gaze of the person photographed” is what “signals a consciousness of a spectator beyond,”[59] the suppression of this gaze through the photocollage may constitute the limits of the aesthetic choice made by Huneault, as the silhouettes covered in fabrics are deprived of their capacity to “look back,” either at the spectator or the photographer. Indeed, the silhouettes in vibrant colours stand as perfect targets for the spectator potentially turned border agent or “migrant hunter.” Interestingly, however, it is the very inscrutability of the migrant silhouettes’ gaze that draws the spectator into a process of re-examination of what might have been the “original” photographs within/behind the photocollaged image.

Both the absence of the photographed person’s gaze and the encasing of photographic windows in the virtual reality installation described earlier act as mirrors returning the spectator’s gaze to herself in a process of re-examination of what it means to be photographed at the border. This mirroring process, which borders while it seeks to deborder, is revelatory of the ambivalence of the documentary practice at the border where one is constantly summoned to position oneself between surveilling and being surveilled, between revealing and hiding. “Dissensus,” as defined by Rancière, helps us understand the re-examination at work on the spectator’s part as a form of liberation from the constraints of the real:

Dissensus brings back into play both the obviousness of what can be perceived, thought and done, and the distribution of those who are capable of perceiving, thinking and altering the coordinates of the shared world. This is what a process of political subjectivation consists in; in the action of uncounted capacities that crack open the unity of the given end the obviousness of the visible, in order to sketch a new topography of the possible.[60]

What Rancière’s “political subjectivation” and Azoulay’s “ethics of spectatorship” have in common is that they endow the spectator with the capacity to envisage radically new possible worlds—radically new in that they challenge the surveillance that characterizes and enables the order of the State or of the police.

Conclusion

By challenging the codes of photojournalism and the very possibility of representation, as well as the belief that the photograph fixes a stable identity, the choices made by Huneault contribute “to making visible decolonial subjectivities.”[61] Identification is clearly articulated in relation to coloniality insofar as Roxham underlines the radical difficulty or impossibility of being at the border in its specific set of power relations. The hypervisibility of the border-crossers in their brightly coloured garb contrasts with their often indeterminate statuses and the largely invisible process of selection by governmental immigration services that ensues. It puts to the fore the urgency of reconsidering the political responses of Western countries, be it in North America or Europe, to the arrival of migrants and asylum seekers.

In this regard, Roxham can be interpreted as the construction of Huneault’s complex representational negotiations at the border rather than an attempt at offering a transparent reflection of it. The tension between the documentary quality of the series and its fictional potential, with its emphasis on the senses, challenges the modernist paradigm of photographic transparency and the position of the spectator as exterior to the artwork. It seems that resorting to hypermediacy as a way to draw the spectator's attention to the constructedness of the border and of border-crossers addresses at least in part the moral callousness of the promise of a “live experience.”

One could further follow Demos, in his discussion of other photographic works dealing with migration, to say that the portrait of migrants offered by Huneault “identifies something uncapturable and unmeasurable, something ever mobile and unfamiliar.”[62] The opacity that results from the collaging brings us away from the simple representation of migrants as victims. On the contrary, documentary approaches that blur the division between the fictive and the real “far from designating a completely disempowered status,” see “migration taking on a certain agency, an autonomy and a potentiality.”[63] Édouard Glissant’s concept of opacité as an aesthetics of resistance to modes of knowing that recuperate the other by rendering him/her transparent[64] seems particularly relevant to highlight what is at the stake in the documentary strategies chosen by Huneault. Opacity in Roxham then is what signals the photographer’s refusal to reduce the world’s diversity to a false sense of universality.[65] The opacity conveyed by the photocollage thus liberates the gaze, whether that of the photographer, the photographed, or the spectator. Opacity then is what “free[s]” the migrant “from representation,”[66] to borrow an expression from Demos.

Parties annexes

Biographical note

Gwendolyne Cressman is an Associate Professor in North American Studies at the Département d’études anglophones, Faculté des langues at the Université de Strasbourg; she is also the coordinator of the Licence Langues et interculturalité (Bachelor’s program in Languages and Crosscultural Studies). Her research focuses on photography at the crossroads of the documentary and the conceptual in Canada and the United States, with a specific interest in migration, landscape, identities, and the construction of memories. Recently, she has published the article “Documentary Photography and the Representation of Life on the Streets in Two Works by Martha Rosler and Jeff Wall: Ethical and Aesthetic Considerations” in IdeAs (2019) and the book chapter “Futures de Carole Condé et Karl Beveridge (2013): art, pouvoir et utopie” in Utopies culturelles contemporaines (Presses Universitaires d’Aix-Marseille, 2019).

Notes

-

[1]

Government of Canada, Asylum claims by year – 2011–2016, https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/refugees/asylum-claims/processed-claims.html; Asylum claims by year – 2017, https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/refugees/asylum-claims/asylum-claims-2017.html; Asylum claims by year–2018, https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/refugees/asylum-claims/asylum-claims-2018.html; Asylum claims by year – 2019, https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/refugees/asylum-claims/asylum-claims-2019.html (accessed 30 June 2020).

-

[2]

John B. Sutcliffe and William P. Anderson, The Canada-US Border in the 21st Century. Trade, Immigration and Security in the Age of Trump, New York, Routledge, 2019, p. 246.

-

[3]

Justin Trudeau @JustinTrudeau, “To those fleeing persecution, terror & war, Canadians will welcome you, regardless of your faith. Diversity is our strength #WelcomeToCanada”, 9:20 PM, 28 January 2017, https://twitter.com/justintrudeau/status/825438460265762816?lang=fr (accessed 5 April 2020).

-

[4]

Government of Canada, Canada-US Safe Third Country Agreement, https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/mandate/policies-operational-instructions-agreements/agreements/safe-third-country-agreement.html (accessed 30 June 2020).

-

[5]

Government of Canada, Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, (S.C. 2001, c. 27), https://laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/i-2.5/ (accessed 5 April 2020).

-

[6]

Celine Cooper, “A ‘Safe-Country’ Dilemma for Canada,” OpenCanada.org, 25 July 2018, https://www.opencanada.org/features/safe-country-dilemma-canada/ (accessed 5 April 2020).

-

[7]

The question has been largely debated in the press. One instance of this discussion is found in Brian Hill, “‘Illegal’ or ‘Irregular’? Debate about Asylum-Seekers Needs to Stop, Experts Warn,” Global News, 26 July 2018, https://globalnews.ca/news/4355394/illegal-or-irregular-asylum-seekers-crossing-canadas-border/ (accessed 5 April 2020).

-

[8]

Government of Canada, Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (S.C. 2001, c. 27), Section 27(1), https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/i-2.5/section-27.html (accessed 5 April 2020).

-

[9]

In 2017, out of 50,289 refugee claims, 27,225 were pending. Of those whose outcome is known, 47% (10,930) failed; see Statistics Canada, Government of Canada, Just the Facts: Asylum Claimants, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-28-0001/2018001/article/00013-eng.htm (accessed 5 April 2020).

-

[10]

Ibid.

-

[11]

Cooper, 2018.

-

[12]

Tavia Grant, “Are Asylum Seekers Crossing into Canada Illegally? A Look at Facts behind the Controversy,” The Globe and Mail, 1 August 2018, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-asylum-seekers-in-canada-has-become-a-divisive-and-confusing-issue-a/ (accessed 5 April 2020).

-

[13]

Michel Huneault, Roxham, created with Maude Thibodeau (interactive design) and Chantal Dumas (sound design), National Film Board, https://www.nfb.ca/interactive/roxham/ (accessed 25 July 2019).

-

[14]

National Film Board, http://www.nfb.ca/ (accessed 30 June 2020). The NFB is the producer and distributer of the virtual reality version of Roxham only.

-

[15]

In Western Europe and North America, see Michel Huneault’s website, http://michelhuneault.com/3/index.php/migration/intersection-2017/ (accessed 26 July 2019).

-

[16]

Sophie Mangado and Michel Huneault, “Roxham, le chemin de l'espoir,” Le Devoir, 24 March 2018, https://www.ledevoir.com/societe/523371/rxham-l-experience (accessed 25 July 2019).

-

[17]

In an exhibition setting, as opposed to the viewing experience on one’s personal computer, the spectator, equipped with an Occulus Rift mask, does not require the use of the mouse as the gaze itself activates the zoom on the silhouettes in the landscape.

-

[18]

In Quebec, image representation rights are protected by the Code Civil du Québec, sections 35 and 36, and the Charte des droits et libertés de la personne, section 5.

-

[19]

The binaural soundtrack intends to render, with as little editing as possible, the linearity of the exchanges at the border. No sounds external to the scene are added.

-

[20]

Stephen F. Wolfe and Mireille Rosello, “Introduction,” in Johan Schimanski and Stephen F. Wolfe (eds.), Border Aesthetics: Concepts and Intersections, New York, Berghahn Books, 2017, p. 5.

-

[21]

T. J. Demos, The Migrant Image: The Art and Politics of Documentary During Global Crisis, Durham, North Carolina, Duke University Press, 2013, p. 245.

-

[22]

David J. Bolter and Richard A. Grusin, Remediation: Understanding New Media, Cambridge, Massachusetts, MIT Press, 2000.

-

[23]

Jacques Rancière, Dissensus. On Politics and Aesthetics, transl. by Steven Corcoran, London, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2010, p. 49.

-

[24]

Demos, 2013, p. xv.

-

[25]

Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography, New York, Zone Books, 2008.

-

[26]

Sophie Bertrand, “Michel Huneault, Roxham: An Intersubjective Artwork for Rethinking the Phenomenon of Migrations,” Ciel Variable, no. 110, Fall 2018, p. 19.

-

[27]

“We have adopted the word [remediation] to express the way in which one medium is seen by our culture as reforming or improving upon another,” Bolter and Grusin, 2000, p. 59.

-

[28]

Ibid., p. 60.

-

[29]

Ibid., p. 70 (emphasis added).

-

[30]

Ibid., p. 70–71.

-

[31]

Ibid., p. 71.

-

[32]

Ibid., p. 9.

-

[33]

Ibid., p. 34.

-

[34]

Rubén Gaztambide-Fernández, “Decolonial Options and Artistic/AestheSic Entanglements: An Interview with Walter Mignolo,” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, vol. 3, no. 1, 2014, p. 198–199.

-

[35]

Bolter and Grusin, 2000, p. 70–71.

-

[36]

Rancière, 2010, p. 139.

-

[37]

The term appears in Henk van Houtum and Stephen F. Wolfe, “Waiting,” in Schimanski and Wolfe (eds.), Border Aesthetics: Concepts and Intersections, New York, Berghahn Books, 2017, p. 129–148.

-

[38]

Dino Buzzati, The Tartar Steppe, transl. by Stuart C. Hood, Boston, David R. Goodine, 2005 [1940].

-

[39]

Rancière, 2010, p. 142.

-

[40]

“Bio,” michelhuneault.com, http://michelhuneault.com/3/index.php/bio/ (accessed 5 April 2020).

-

[41]

Beaumont Newhall, “Documentary Approach to Photography,” Parnassus, vol. 10, no. 3, 1938, p. 4–6.

-

[42]

Ibid.

-

[43]

Estelle Blaschke, “Jeff Wall: ‘Near Documentary.’ Proche de l’image documentaire,” Conserveries mémorielles, no. 6, 2009, http://cm.revues.org/390 (accessed 5 April 2020).

-

[44]

Demos, 2013, p. 98.

-

[45]

Giorgio Agamben, Homo Sacer. Sovereign Power and Bare Life, transl. by Daniel Heller-Roazen, Stanford, California, Stanford University Press, 1998.

-

[46]

Demos, 2013, p. 99.

-

[47]

Ibid.

-

[48]

Azoulay, 2008, p. 85.

-

[49]

Ibid., p. 117.

-

[50]

Ibid., p. 104.

-

[51]

Ibid., p. 85.

-

[52]

Ibid., p. 104 (emphasis added).

-

[53]

Azoulay refers to the blowing up of a photograph as exercising the effect of a magnifying glass. Ibid., p. 376.

-

[54]

On the question of the window and its reflection in photography, see Muriel Berthou Crestey, “De la transparence à la ‘disparence’: le paradigme photographique contemporain,” Appareil, no. 7, 2011, https://journals.openedition.org/appareil/1212 (accessed 5 July 2020).

-

[55]

Azoulay, 2008, p. 130.

-

[56]

Ibid., p. 168.

-

[57]

Ibid., p. 122.

-

[58]

Ibid. (emphasis added).

-

[59]

Ibid., p. 183.

-

[60]

Rancière, 2010, p. 49.

-

[61]

Walter Mignolo and Rolando Vazquez, “Decolonial AstheSis: Colonial Wounds/Decolonial Healings,” Social Text, 15 July 2013, https://socialtextjournal.org/periscope_article/decolonial-aesthesis-colonial-woundsdecolonial-healings/ (accessed 30 June 2020).

-

[62]

Demos, 2013, p. 19.

-

[63]

Ibid.

-

[64]

Patrick Crowley, “Édouard Glissant: Resistance and Opacité,” Romance Studies, vol. 24, no. 2, 2004, p. 106, https://doi.org/10.1179/174581506x120073 (accessed 5 July 2020).

-

[65]

Ibid., p. 107.

-

[66]

Demos, 2013, p. 100.

Liste des figures

Fig. 1

Screenshot from Roxham, Michel Huneault, 2017, National Film Board website, https://www.nfb.ca/interactive/roxham/ (accessed 30 June 2020).

Fig. 2

Screenshot from Roxham, Michel Huneault, 2017, National Film Board website, https://www.nfb.ca/interactive/roxham/ (accessed 30 June 2020).

Fig. 3

Screenshot from Roxham, Michel Huneault, 2017, National Film Board website, https://www.nfb.ca/interactive/roxham/ (accessed 30 June 2020).

Fig. 4

Screenshot from Roxham, Michel Huneault, 2017, National Film Board website, https://www.nfb.ca/interactive/roxham/ (accessed 30 June 2020).

Fig. 5

Screenshot from Roxham, Michel Huneault, 2017, National Film Board website, https://www.nfb.ca/interactive/roxham/ (accessed 30 June 2020).

Fig. 6

Screenshot from Roxham, Michel Huneault, 2017, National Film Board website, https://www.nfb.ca/interactive/roxham/ (accessed 30 June 2020).

Fig. 7

Screenshot from Roxham, Michel Huneault, 2017, National Film Board website, https://www.nfb.ca/interactive/roxham/ (accessed 30 June 2020).