Résumés

Abstract

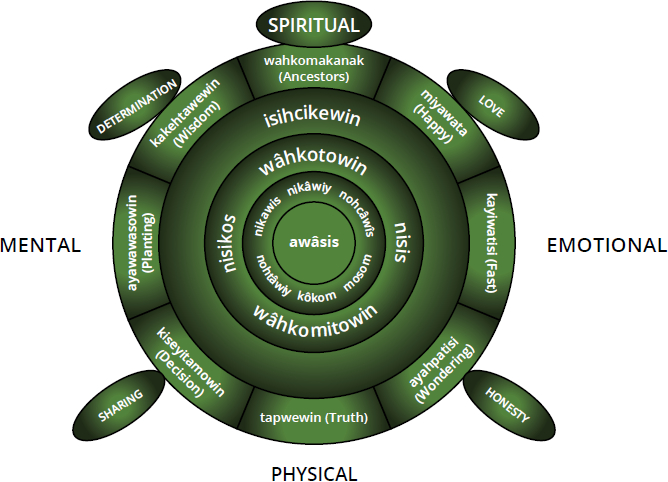

nêhiyaw kesi wâhkotohk (how we are related) is a relationship mapping resource based in the nêhiyaw (Cree) language and worldview. The relationship map was developed incrementally through a five-year process of connecting nêhiyaw worldviews of child and family development with the wisdom and teachings from nêhiyaw knowledge-holders. Over time, in ceremony and with many consultations with wisdom-keepers, the authors began connecting the nêhiyaw teachings into a resource that would allow (mostly non-Indigenous) human service providers working with nêhiyaw children, families, and communities a means to understand and honour the relational worldview and teachings of the nêhiyaw people. This kinship map came to include nêhiyaw kinship terms and teachings on wâhkohtowin (all relations) in order to recognize all the sacred roles and responsibilities of family and community. In addition, the vital role of isîhcikewin (ceremony) and the Turtle Lodge Teachings (nêhiyaw stages of individual, family, and community development) became embedded within this resource, along with the foundational teachings that create balance and wellbeing that enable one to live miyo pimâtisiwin (the good life).

Keywords:

- wâhkohtowin,

- kinship,

- Indigenous child welfare

Corps de l’article

Introduction

What you are about to read here is not an article about “research” in the way the research process is generally understood within the context of mainstream academia or as portrayed in many research publications. The concepts and teachings shared here formed much of the foundation of nêhiyaw family and community relationships long before the first settlers arrived. We are more engaged in a process of re-vealing rather than re-searching.

In our work in relationship mapping, we have had two primary goals. Our first goal has been to challenge, and hopefully replace, Western-based concepts of child development and Western-based definitions of children and families with nêhiyaw teachings, language, and ceremonies that reflect a very different understanding of children and their journey in this world. Western-based assessment tools, when used as default assessment tools with Indigenous children and families, offer minimal cultural insights, blunt the potential to build healthy therapeutic relationships, and are, in many ways, a continuation of the process of colonization.

Our second goal has been to bring to the forefront the pre-contact nêhiyaw teachings and worldviews of children and families, and to support the understanding and use of those teachings in the services and supports that are offered to nêhiyaw families and children today. In the following pages, we will first share many of the fundamental teachings, followed by an exploration of language and its importance, and conclude with drawing the teachings, learnings, and concepts together into a model that reflects those connections and worldviews. Our intent is only to share the learnings that were shared with us–in the hope that nêhiyaw children, families, and communities can, in this one small area, encounter service providers that understand, honour, and incorporate distinct nêhiyaw worldviews and teachings into their practice.

The purpose of nêhiyaw kesi wâhkotohk is to share foundational teachings on kinship, community, ceremony, development, and wellbeing in a method that is transferable to practice. The intention is to create a culturally appropriate and teaching-based process that supports the provision of culturally relevant supports and practice.

Kinship and Background

An emerging practice in Alberta Children’s Services is the inclusion and support of kinship relationships throughout a family’s involvement with child welfare. While the term kin has often been understood as only connected to blood relatives, child welfare, in connection with the teachings and training provided in the model shared here, has begun to extend this definition beyond biological ties and to recognize Indigenous families’ broad social and relational networks (Geen, 2004; Kang, 2007; McHugh, 2009). During the initial child welfare assessment, kinship is prioritized in order to identify both informal resources and existing natural supports within family systems as a means to identify various interventions (Garwood & Williams, 2015; Leon et al., 2016; McHugh, 2009). If out-of-home placement is determined to be necessary, direct kinship care is often explored first in order to enhance child wellbeing and preserve family connection (Garwood & Williams, 2015; Geen,2004; Kang, 2007; Leon et al., 2016; McHugh, 2009). When kinship placements are not viable, concurrent planning occurs with the intent of retaining family input (Garwood & Williams, 2015; Leon et al., 2016; McHugh, 2009). As a consequence of these practices, concepts of what constitutes kinship or relationships are becoming integral to child welfare.

The precedence of kinship within child welfare is highly associated with the intention of maintaining lifelong connection for children and their families. Western legal constructs of guardianship within child welfare legislation are being deconstructed and now encompass the importance of sustained lifelong connections to family and community (Stangeland & Walsh, 2013). Relationships sought through kinship have been understood, from a Western perspective, through Bowlby’s (1969) attachment theory and Erikson’s (1968) psychosocial development, where secure attachments formed in early childhood are linked to positive identity formation in adulthood (de Finneya & diTomasso, 2015; Leon et al., 2016; Lindstrom & Choate, 2016; McHugh, 2009; Simard, 2019; Stangeland & Walsh, 2013). Bronfenbrenner’s (1994) ecological theory captured the linkage of kinship to wider social and community relationships that foster belonging and wellbeing (Leon et al., 2016; McHugh, 2009; Stangeland & Walsh, 2013).

For nêhiyaw children and families, the framework for creating and maintaining lifelong culturally based connections is held within the Turtle Lodge Teachings explored below. These cultural connections are established through relationships with the family, kinship relations, and the community in order to maintain culture and identity (Bennett, 2015).

The process for determining and evaluating kinship connections is typically facilitated through the use of a genogram. Those unfamiliar with the term genograms may be more familiar with the use of similar ancestry diagrams that diagrammatically link, most often, a male (represented by a square) to a female (represented by a circle) with a horizontal line between the two. Any children from that relationship are usually indicated by vertical lines descending from the horizontal line–again with squares and circles indicating gender. While this is admittedly a very simplistic description of a genogram, genograms have certainly gained traction in child welfare practice, with some suggesting that they are one of the most popular tools used by social workers when conducting family assessments (Dore, 2012).

The genogram was first used in family and individual therapy and was guided by family systems theory. Kerr and Bowen (1988) explained that Murray Bowen began using what he called the family diagram, which included all the important information about one generation on one page in order to assess and gain a better understanding of his patients. Later, Bowen wrote that the family diagram was incorrectly considered the same as genealogy and therefore termed the genogram (Kerr & Bowen, 1988). While similar to genograms, genealogy has historically been used to track blood relation-based rights, privileges, hierarchical ascendancy, and, more recently, for religious reasons and family interest. In an effort to improve cultural understanding, social workers and other practitioners have developed other assessment tools as enhancements or alternatives to the genogram–for example, the ecomap (Hartman, 1978) and the cultural genogram (Hardy & Laszloffy, 1995; Warde, 2012). While these tools were adapted with good intentions, they maintain Eurocentric, nuclear definitions of family and subdue the vitality of culture (Lindstrom & Choate, 2016; Simard, 2019). The majority of these tools have been developed from a specific cultural reality focused on Western, commonly accepted concepts of positive family values and often unspoken and unrecognized ideological underpinnings of “nuclear” families and independent community.

The use of cultural genograms or ecomaps often becomes an attempt to impose Western ideologies on Indigenous families through a “cultural lens” that is seldom based within the depth of Indigenous knowledge and worldview. This is a stark replication of colonialism when Indigenous beliefs and values are relegated as secondary to dominant Western understandings of attachment, development, family, and community. An Indigenous understanding of family, relationships, responsibilities, and connection to community and ancestors is vastly different than what the genogram and other Western assessments are able to capture (Lindstrom & Choate, 2016; Simard, 2019). These assessments are simply not designed for the task.

Western concepts of guardianship, attachment, and psychosocial development are being deconstructed to create room and recognition for Indigenous teachings on parenting and child, family, and community development (Bennet, 2015; de Finney & diTomasso, 2015; Lindstrom & Choate, 2016; Simard, 2019; Stangeland & Walsh, 2013). When Indigenous language, ceremony, protocol, and teachings are understood as essential to the development of Indigenous children, families, and communities, then Indigenous teachings on kinship and child-raising become vital to ensuring their individual and communal health and wellbeing–all of which constitute an Indigenous understanding of lifelong connections. These relational connections are much more complex than commonly used Western familial concepts of connection, which are primarily based on bloodline. Within the nêhiyaw worldview, concepts of connection are based on the roles that are played within the life of the child, family, and community.

As such, it has been proposed that new approaches must be created to replace the genogram and find meaningful ways to assess and ensure cultural connections (Lindstrom & Choate, 2016). nêhiyaw kesi wâhkotohk, a Cree relationship mapping resource based in the nêhiyaw (Cree) language and worldview, was created to address this need and provides a way of understanding and relating to Indigenous children, families, and communities, all within an Indigenous worldview.

Our Beginning Journey …

As mentioned previously, the development of the mapping resource occurred over an extended period of approximately five years of direct work–and a lifetime of teachings. A team comprised of Indigenous and non-Indigenous academics, instructors, ceremony-holders, language-speakers, Elders, wisdom-holders, service providers, and community members have been engaged, over the past 20 years, in teaching and training primarily social workers in culturally based practice. Many culturally based resources have been developed by this team, with only one being the relationship mapping resource. All of the resources have been developed within ceremony, with protocol, as much as possible in the language, and with multiple revisions based on Elders’ and community members’ responses.

The concepts and teachings included in nêhiyaw kesi wâhkotohk represent a cumulative journey of learning in ceremony, language, and through teachings and practice-based evidence. In a nêhiyaw world, the process of kiskinohâmakewin reflects that learning and doing are not separated–to know is to do. This aligns with the understanding that practice-based evidence in Indigenous knowledge systems is based on experiencing or doing the learning (Abe et al., 2018; Naquin, 2008).

This learning/doing process, kiskinohâmakewin, has had a strong influence on the approach our team uses to share nêhiyaw kesi wâhkotohk with service providers. The training we provide on nêhiyaw kesi wâhkotohk is facilitated by an Elder, in ceremony, through the language, using the same practice-based evidence that guided our team. While we appreciate the opportunity to share nêhiyaw kesi wâhkotohk in written form in this article, it is strongly advised that these teachings be shared and experienced in ways that honour the practice of kiskinohâmakewin.

It is also important to acknowledge that the concepts within nêhiyaw kesi wâhkotohk and this article provide a basic understanding of nêhiyaw teachings on kinship and child, family, and community development. As a relational society, a full understanding of relationships and protocols becomes very complex. As indicated earlier, nêhiyaw kesi wâhkotohk is situated within the nêhiyaw worldview and language. As such, it is not transferable to all Indigenous ways of knowing. As the concepts and teachings shared are foundational, there may be equivalent or similar teachings within other Indigenous worldviews. Service providers, both Indigenous and non-Indigenous, are encouraged to adapt the use of nêhiyaw kesi wâhkotohk, if possible, in ways that honour their specific community.

Language

Before introducing nêhiyaw kesi wâhkotohk, it is crucial to discuss the impact of language. Indigenous teachings of parenting, kinship, and child, family, and community development are vastly different than Western understandings of these concepts. Beginning to understand this difference is dependent on experiencing the depth of meaning that is contained within the nêhiyaw language. All nêhiyaw teachings and values are embedded in the language–it is through the language that relationships and connections to spirit and identity are truly understood (Makokis et al., 2010). In the context of relationship mapping, the sacred roles and responsibilities associated with child raising can only be understood through nêhiyaw kinship terms. When describing nêhiyaw kesi wâhkotohk, a variety of nêhiyaw kinship terms will be used and the root meaning will be shared in an attempt to convey these spiritual roles and responsibilities.

The dominance of Western worldviews and, with that, the pervasiveness of the English language, often leads to nêhiyaw terms being translated to an English equivalent (Makokis et al., 2010). Again, this further replicates the process of colonization, as meaning is lost when we attempt to fit nêhiyaw concepts into a Western paradigm. There is no possible way to find a direct translation between English and nêhiyaw terms given the difference in worldviews. The nêhiyaw language is primarily verb-based and emphasizes connection and relationship, whereas the English language is primarily noun-based and creates individuality and separation (Makokis et al., 2010). In beginning to understand relationship terms, it is important to remember that these are nêhiyaw verbs (or job descriptions) and thus lose vital meaning when we attempt to translate Indigenous verbs into Western nouns.

The nêhiyaw kinship terms that will be shared are relational words that connect relationship roles to their specific responsibilities and purpose. As the nêhiyaw language is verb/connection/relationship-based, kinship connections are determined by the individual who fulfills that role. Another consequence of Western, noun-based worldviews and languages is that biological relationships are often prioritized and assessed. As noted earlier, a Western genogram focuses on biological relatives and minimizes non-biologically connected individuals who may play a significant role in a child’s life (Lindstrom & Choate, 2016). It is crucial to understand that concepts such as “step”-relationships (step-son, step-mother, for example) are Western-based and again, they are a means for differentiation and separation. In the nêhiyaw language, there is no term for “step” relatives as the language instead privileges roles, connections, and relationships. The concept of tapakohtowin recognizes that the community has a shared responsibility to raise children, especially when additional support is required. In relationship mapping, this allows the person who fulfills a significant parenting or relationship role in a child’s life to be honoured, regardless of genetic connections.

Another fundamental difference between the Western world and the nêhiyaw world is that the nêhiyaw language does not have gender-based pronouns. Rather, nêhiyaw worldviews organize connection in terms of animate or inanimate, a difference that has fundamental implications for relationship roles and responsibilities. Position and connection are not based within or differentiated primarily by gender, rather it is the role that is provided in connection to the child that prioritizes the relationship. In other words, animate beings that create and provide love and caring for small traveling spirits are not distinguished so much by gender but more by role. English gender-based terms, such as aunt or uncle, would not be relevant or appropriate in this context. This suggests that genograms, which are partly based on gender constructs, are even more inappropriate and inadequate for assessing Indigenous families. An “aunt” or “uncle,” in nêhiyaw, would be someone who performs a sacred child-raising role to nurture the spirit of an awâsis. The actual nêhiyaw kinship terms include the connection of that specific relationship role to the child, family, and community and gender is indicated within the description of that relationship. To emphasize, nêhiyaw relationship terms convey a job description and the focus is on the role, relationship, and connection–the action and the verb. For example, unlike Western conventional genograms and familial concepts, an awâsis (described below) may have many aunties or grandmothers who may or may not be blood-related–their connection is determined by how they fulfill those roles in the life of the child. In addition, something that may be considered inanimate in a Western world may be understood as being animate in an Indigenous world.

In nêhiyaw, the term awâsis is often interpreted to mean “child,” however, embedded in this word is the root word awa, meaning animate, and the suffix sis, which indicates smaller version of the root word. Consequently, the concept awâsis more directly implies “a small animate spirit” or “a small spirit engaged in a human journey.” These terms are further embedded in the nêhiyaw concept of good child raising or miyo ohpikinâwasowin, where miyo means good, ohpiki means to grow, and awasow means to warm oneself over a fire. All of these concepts reflect the spiritual role of raising children and how one warms their own spirit so they can then nurture the spiritual fire of the awâsis.

Relationship Words and Concepts

The relationship terms listed below encompass many teachings on the roles and responsibilities animate beings play in nurturing a child or a small travelling spirit. Because these terms are verb-oriented, relational, and descriptive, the true depth of their meaning cannot be fully developed in a written, translated context, and as such, this article conveys only a basic understanding of these relational concepts. Additionally, we hope the readers will try, as best as they can, to remember that these relationship terms are verbs that entail action and responsibility.

While we wish we could share these terms without resorting to the closest English equivalents, we understand that this is necessary to the learning and explanation process. As we explain these relationship terms, our intention is to relay them in ways that are, hopefully, reflective of their verb-based nature. Despite our best attempts, the differences between nêhiyaw and Western language and worldviews will ultimately cause us to explain verbs through the use of nouns.

awâsis

An awâsis, as noted earlier, is a child or rather “a small animate being,” “ a small travelling spirit,” or “a small spirit engaged on a human journey.”

nikâwiy

The relationship term nikâwiy refers to “my mother.” This term honours a child’s relationship to their birth mother and it recognizes the sacred role a child’s mother holds in bringing them into the human world and giving them the gift of life.

nohtâwiy

nohtâwiy is the relationship term for “my father.” Similar to above, this term honours a child’s relationship to their birth father.

nikawîs

The relationship term nikawîs is derived from nikâwiy and the suffix sis indicates small, meaning “my little mother.” This is an animate being who shares the same roles and responsibilities as the mother in nurturing and raising an awâsis. In English, this is understood as an aunt, or “my mother’s sister,” but in a nêhiyaw context, this would be whoever fulfills that nurturing “little mother” role in a child’s life regardless of biological ties. If an awâsis has a step-mother or someone who fulfills this parenting role, they would also be considered a nikawîs.

nohcawîs

The relationship term nohcawîs stems from nohtâwiy and again, the suffix sis indicates small meaning “my little father.” This is an animate being who shares the same roles and responsibilities as the father in nurturing and raising an awâsis. In English, this is understood as an uncle, or “my father’s brother,” but in a nêhiyaw context, this would be whoever fulfills that nurturing “little father” role in a child’s life regardless of biological ties. If an awâsis has a step-father or someone who fulfills this parenting role, they would also be considered a nohcawîs.

nôhkom

nôhkom refers to “my grandmother” and this definition extends beyond “my mother or father’s mother.” It includes “my grandmother’s sisters” or “my great aunts,” “my great uncle’s spouse,” and any “older animate female being” in the community who fulfills the nurturing role of a grandmother.

nimosom

nimosom refers to “my grandfather” and again, this definition extends beyond “my father or mother’s father.” It includes “my grandfather’s brothers” or “great uncles,” “my great aunt’s spouse,” and any “older animate male being” in the community who fulfills the nurturing role of a grandfather.

nisikos

The relationship term nisikos refers to “my father’s sister” and “my mother’s brother’s wife” or “my mother’s sister-in-law” and “my mother-in-law”. A child’s nisikos fulfills a different, but equally valid and cherished role than the nikawîs (little mother). The nisikos is responsible for disciplining a child when required so this does not impact a child’s relationship with their nikawîs (little mother).

nisis

The relationship term nisis refers to “my mother’s brother” and “my mother’s sister’s husband” or “my mother’s brother-in-law” and “my father-in-law.” A child’s nisis fulfills a different, but equally valid and cherished role from the nohcawîs (little father). The nisis is responsible for disciplining a child when required so this does not impact a child’s relationship with their nohcawîs (little father).

wâhkotowin

This refers to any community member or “any animate human being” who is instrumental to nurturing the awâsis. This relationship term is broad and could include anyone, even a social worker, better defined in nêhiyaw as “a good relationship worker,” who is pivotal to a child’s growth and development.

wâhkomitowin

This recognizes the relationship the awâsis has to the land and Mother Earth. It is important that a child remains connected to the land and the community from which they come. In a nehiyaw universe, the land and Mother Earth are understood as being animate–and play a vital role in the health and nurturing of the awâsis.

Isihcikewin

This refers to ceremony, but the root word isihycike means “to organize and arrange.” This represents that ceremony is central to all aspects of the nêhiyaw way of life. Across the lifespan, there are many ceremonies that are integral to one’s mental, emotional, spiritual, and physical wellbeing so they can experience miyo pimâtisiwin on their human journey.

The Seven Turtle Lodge Teachings

The Turtle Lodge Teachings are a nêhiyaw parallel to Western theories mentioned earlier. The nêhiyaw Turtle Lodge Teachings entail key stages or rites of passage that are vital to practicing miyo ohpikinâwasowin or raising children spiritually well to ensure the healthy development of the child, family, and community. These rites of passage encompass many teachings, ceremonies, and celebrations that are essential to creating mental, emotional, spiritual, and physical wellbeing and living a good, balanced life–miyo pimâtisiwin.[1]

Each stage of development within the Turtle Lodge Teachings is represented by one of the seven willow branches that creates the frame for the matotisân (sweat lodge or Turtle Lodge). The term matotisân is derived from the word matoh, which means “to cry,” symbolizing that this lodge is a place for mental, emotional, spiritual, and physical cleansing. The matotisân also represents our mother’s womb, and it is where our birth and beginnings can be re-experienced to ground us in who we are. It is the responsibility of the parents, family, and community to ensure that children experience these stages of development in loving and nurturing ways. The understanding of an awâsis as a “small animate spirit” is embedded in the nêhiyaw preconception teachings on children, where they are seen as gifts loaned to us by the Creator. Children are prepared by the Spiritual Grandmothers to enter the human world bringing gifts, purpose, and teachings from the spirit world. The awâsis chooses their parents, family, and community to experience love on their human journey while being nurtured in ways that are honouring of their gifts so they can know their purpose.

miyawata (Happy Stage)

A child born into a healthy home, family, and community experiences happiness because their entire emotional, spiritual, mental, and physical needs are nurtured. The child is the focus of the parents, family, and community. This stage grounds the child in a loving, caring, and nurturing environment. To help create this environment, a wâspison (moss bag) is used to keep the awâsis safe and secure while allowing them to be kept close to their mother’s heart, replicating the environment of her womb. The nohtawiy (father) takes on the responsibility of building a wêwêpison (swing) for the awâsis, so they can be gently rocked while being sung lullabies.

During this stage, an awâsis is welcomed into the world with a ceremonial song, inviting the spiritual grandmothers, grandfathers, and ancestors who prepared this “small animate spirit” to protect the awâsis on their human journey. The nitisiy (belly-button or umbilical cord) ceremony also takes place to honour the connection between the awâsis and their mother. The Elders put the nitisiy in a special place, such as an ant’s nest, to ask that the awâsis will grow to be a strong, diligent worker. The awâsis also experiences a naming ceremony, where an Elder gifts the child with a spiritual name. This name reflects the gifts and purpose that the awâsis brings from the spirit world and is meant to guide and protect the awâsis on their human journey.

kayiwatisi (Fast Stage)

Children begin to walk and run, so they are building their physical selves. They are also discovering the world around them. Children develop physically, so they are less attached and are beginning a more independent state. At this time of a child’s life, a Walking Out Ceremony occurs to honour when the awâsis begins walking and taking their first steps on Mother Earth. During this ceremony, the awâsis is provided with a sacred bundle to support them on their human journey. Additionally, everyone in the child’s life, their parents, grandfathers, and the community, makes a commitment to supporting the spiritual growth and development of the awâsis.

ayahpatisi (Wondering Stage)

In this stage, children are developing their curiosity. They are wanting to know more about the world, so they are continually inquiring. Language development is critical at this time. As children find things to do, the family teaches them how to live in a good way. This is the stage where children learn how they are related to people and how to respect and listen.

tapwewin (Truth Stage)

The truth stage is when children go through their own experiences and learn through observation. In this stage they go through their rites of passage. Boys make their first successful hunt, they are honoured, and what they provide is shared with everyone in the community. They are no longer a child and are accepted into having adult responsibilities as providers. Boys usually go through a vision quest–either through a fasting ceremony or a Sundance.

Girls go through rites of passage when they experience their first moon-time. They are usually housed with Elderly ladies for four days, and during this time they are taught their responsibilities and how to have healthy relationships. They are also taught about the importance of keeping the body in a balanced state and the importance of boundaries. At this stage, both boys and girls are taught protocols–how to treat other people, relationships, animals, plants, etc.

kiseyitamowin (Decision-Making Stage)

After learning from many people, experiences, and teaching, someone in the decision-making stage will be able to recognize their gifts. In this stage, we decide what we are going to do with our lives and how we can use the gifts we have been given to serve the community. We also would have been taught by the Grandmothers and the Elders the knowledge of what our purpose is in using our gifts and our role. We can be responsible, accountable to the community, know our protocols–this stage also includes determining who our spouse will be.

ayawawasowin (Planting Stage)

Getting married, having children, and raising those children in the ways you have been taught with all the protocols, teachings, ceremonies, relationships and responsibilities happens in the planting stage. Stories, language, and culture are very important in this stage as they are passed from generation to generation.

kakehtawewin (Wisdom Stage)

Having gone through all the stages, we have gained experience and our role then is to share this with others. kiseyiniw refers to an older man who is caring and loving. nocikwesiw refers to an older woman and it means that her home is overflowing with so much love that she sits outside, beside the door, to make sure that it is protected. We honour the wisdom given to us over our journey, which means it is our duty to pass it along in a loving and caring way. It is not our knowledge to keep; the knowledge belongs to all of us. We become the storytellers to guide the next generation.

It is important to acknowledge that these are teachings and the list above is only that – a list, and does not contain the actual teachings. These must be received in ceremony, in the language, from an Elder. When supporting Indigenous families, it is vital that child welfare workers understand the Turtle Lodge Teachings so they can understand where a child (and the family) is at within these stages and support the family in asking for a specific ceremony, celebration, or rite of passage. It is also crucial to note that these teachings are not linear or defined by age–they are circular and relational. The developmental stage of the awâsis is determined by where they are on their human journey; they can journey back and forth between various stages. If an awâsis did not have the opportunity to experience a certain ceremony, celebration, or rite of passage, they are always able to experience them later on in life, even as adults. With that being said, the Turtle Lodge Teachings ensure healthy child, family, and community development while providing ways to restore a child and family’s connection to spirit and culture when needed.

Relationship Mapping

nêhiyaw kesi wâhkotohk is not intended only as a resource for documenting relationships and community connections. It is also intended as a process to engage in the creation of relationships and connections between service providers and service users. Integrating the Natural Laws, the Seven Teachings, language, and ceremony within the context of the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual realms–in connection with the stages of the Turtle Lodge Teachings–supports the creation of an Indigenous worldview-based understanding of our relationships to our family, our community, the environment, and our ancestors.

The most significant challenge in sharing this process as a journal article is the necessity to write in English. As mentioned earlier, the act of translating creates almost insurmountable challenges to true meaning. It is our hope that the deeper meaning of the process can still be honoured and communicated. With that caveat, we will try to share the process of relationship mapping. We suggest that the process be approached in stages, in relationship with the service user, and begin with a smudging ceremony.[2] With reference to the following relationship mapping diagram (Figure 1), we will describe and explain each stage of the process.

Creating the Relationship Image

At the centre of the circle is the awâsis, the small spirit on a human journey. Siblings can also be placed in this circle if that is felt to be an appropriate place for them. It may be repetitive at this point, but a small reminder that we are not using the term “sibling” in the Western sense of the term. In this Indigenous universe, siblings (and all other relationships) are determined by relationship, connection, and role–not by genetics.

The next circle contains the closest relationships to the awâsis, the individuals who fulfill the roles of nikâwiy (mother), nohtâwiy (father), nikawîs (little mothers), and nohcawîs (little fathers). This circle also includes the individuals who fulfill the roles of nohkom (grandmothers) and nimosom (grandfathers). These people have a common role–to directly nurture, love, care for, discipline, guide, and honour the gifts of the little spirit on its human journey. There can be many individuals who fulfill the roles of mother, father, little mother, little father, grandfather, and grandmother in the life of the awâsis.

The next circle contains the nisikos (the father’s sisters) and nisis (the mother’s brothers). Remember that the relationship map of the father will, most likely, contain people who fulfilled significant roles in the father’s life–so there may not be direct genetic connections. This circle also contains wâhkomitowin (the community) and wâhkohtowin (the land). This circle is also significant in that it includes all the resources in the community that support the awâsis, including the agency and the service provider. The service provider is recognized as playing a significant role in the life of the awâsis, and needs to be included within the context of the relationship mapping as the impacts and meaning of the relationship will last a lifetime for the awâsis.

The next circle explores the vital role of isihcikewin (ceremony) in the life of the awâsis and all of those in the previous circles. Ceremony heals, nurtures, teaches, guides, and supports the life journey. Ceremonies are connected to seasons, to life stages, to daily life, to governance, to the essential life teachings, to learning, to the ancestors, to teaching, etc. The community is grounded in ceremony, and it is extremely important to understand the role and meaning of traditional ceremony in a specific community. We cannot thrive without ceremony (and language).

The next circle brings us back to the Turtle Lodge Teachings covered earlier. It is these stages of life and the teachings and ceremonies associated with them that enable us to understand and support the human journey of the awâsis. As we explore the relationship map of the awâsis in connection to the Turtle Lodge Teachings, we can also understand how we can support the ceremonies and rites of passage that are connected to the awâsis. The relationship between the awâsis and their position in the circle of the Turtle Lodge Teachings is specific to the individual human journey of each awâsis, and is not connected to specific indicators such as age or growth. In addition, those people who have nurtured the journey of the awâsis and who may have passed on to become ancestors, if not already added within an earlier circle, can be honoured by being included within the ancestor section of the Turtle Lodge Teachings.

Finally, we understand that the entire relational process and relationship mapping is based within the teachings of the Natural Laws (love, honesty, sharing, and determination) and the lived balance of the four realms (spiritual, emotional, physical, and mental). Different elements in the life of the awâsis can be included within the four realms–for example, sports could be included within the physical realm, school and classes in the mental realm, participation in ceremony in the spiritual realm, and love, support, and caring in the emotional realm.

We have found that the conversation, sharing, and relationship building that occurs within the process of doing the relationship mapping is almost more important than the map itself, fostering wâhkomitowin. The experience has a strength-based focus and encourages the exploration of positive influences and experiences within the journey of the awâsis.

Figure 1

The Turtle Lodge Relationship Mapping Image

Why a Turtle?

nêhiyaw kesi wâhkotohk is framed within the structure of a turtle to bring together nêhiyaw teachings on truth and how an awâsis can live and experience truth. Within the Seven Teachings, the final teaching is tapwewin (truth), and truth is taught by the miskinâhk (turtle) who carries all the previous teachings on its shell. Derived from the word miskinâhk is the term mêskanaw, meaning a pathway or a journey. As tapwewin is taught and modeled by the miskinâhk, to be on a journey means to be on the pathway of living and seeking truth. The miskinâhk is an unwavering being that commits to following the path of truth. Additionally, the miskinâhk has the ability to recede inside its shell and be introspective, affirming that knowing yourself is central to living and experiencing truth. For an awâsis, an experience of truth comes from being raised in ceremony and learning the language, from feeling loved and nurtured by your parents, family, and community, from knowing who you are, where you come from, and having your spiritual gifts and purpose honoured.

Challenges

As stated earlier, we have only explored the basic relationship concepts in this document. As the nêhiyaw universe and language is based within the context of relationships, there are a large number of relationship terms, and relational protocols, that we have not included. Also, there are additional concepts and teachings, such as the spiritual clan of the awâsis, that are extremely important in understanding connections, relationships, healing, and appropriate teachings and must be considered within the life of the awâsis. This article is only a beginning, and we hope that others can carry these concepts further through research, language, and ceremony.

We also acknowledge that we have only focussed on the nêhiyaw worldview, ceremony, and teachings. As we live and work on primarily nêhiyaw land, we have learned that we must honour the teachings of the land where we live. Other communities may have similar concepts as those we have shared, and we encourage others to explore the possible use of relationship mapping in their respective communities. We are very willing to aid and support that work in any way we can.

One of our greatest challenges has been the use of language and translating from nêhiyaw to English. Translating from a nêhiyaw verb to an English noun instantly creates a loss of full meaning–and in the training, we have seen that it is challenging for English-only speakers to think of aunts and uncles not as nouns and to conceptualize, while still conversing in English, of nêhiyaw verbs.

Future work suggests we need to explore the use of the relationship mapping tool with other Indigenous populations. Although many of the agencies successfully using the tool are urban-based (and many others are rural) it would be helpful to understand how to support those Indigenous service users who are less connected to the terms and the teachings and how they might respond to its implementation.

We hope to continue with that work.

Continuing Our Journey …

It is our hope that, by using the relationship mapping model described above, service providers (both Indigenous and non-Indigenous) working with Indigenous children and families will find new ways to work within the context of language, ceremony, protocols, and teachings. As we have been sharing the teachings and the model over the past year, we have noticed some significant changes that have come through it. A number of agencies have committed to no longer using the Western genogram tool, and have replaced the assessment process entirely with the relationship mapping model. They have found, both with Indigenous and non-Indigenous service users, that the model is a strong relationship-building tool, is extremely strength-focused, and presents an accurate picture of the positive resources in the service user’s environment. It allows the inclusion of significant individuals who may not be blood-related and honours the role of the service provider in the client’s life. Other practitioners have run the mapping tool alongside the genogram, and have reported that the mapping tool creates more understanding of the service user’s life experience and allows the provider to explore different systems of support. Some agencies, combining the mapping resource with the teachings in the four realms (physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual) have found that the blending of the two resources allows for a deeper understanding of the service users’ needs and how supports from an entirely Indigenous worldview can be provided to the client. Agencies have also reported that the mapping tool works very well with diverse clients from other areas of the world and that, in some cases, other nationalities relate much better to the teachings and concepts in the mapping tool than the genogram.

Truly, it is only through these practices that we can be miyootôtemihtohiwew otatoskew–good relationship workers.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

The Seven Turtle Lodge Teachings presented in this article are interpreted by author, Leona Makokis

-

[2]

For those readers not familiar with the smudging ceremony, or the local equivalent, we suggest connecting with a local Indigenous knowledge-holder, offer them tobacco or whatever is appropriate in your context, and request a teaching about smudging.

Bibliography

- Abe, J., Grills,. C., Ghavami, N., Xiong, G., Davis, C., & Johnson, C. (2018). Making the invisible visible: Identifying and articulating culture in practice-based evidence. American Journal of Community Psychology, 6(1-2), 121-134. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12266

- Bennet, K. (2015). Cultural permanence for Indigenous children and youth: Reflections from a Delegated Aboriginal Agency in British Columbia. First Peoples Child & Family Review 10(1), 99–115.

- de Finney, S., & di Tomasso, L. (2015). Creating places of belonging: Expanding notions of permanency with Indigenous youth in care. First Peoples Child & Family Review 10(1), 63–85.

- Garwood, M. M., & Williams, S. C. (2015). Differing effects of family finding service on permanency and family connectedness for children new versus lingering in the foster care system. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 9(2), 115-133. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2015.1008619

- Geen, R. (2004). The evolution of kinship care policy and practice. Future of Children, 14(1), 131–149. https://doi.org/10.2307/1602758

- Hardy, K., & Laszloffy, T. (1995). The cultural genogram: Key to training culturally competent family therapists. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 21(3), 227-237. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.1995.tb00158.x

- Hartman, A. (1978). Diagrammatic assessment of family relationships. Social Casework, 59(8), 465–476. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F104438949507600207

- Kang, H. (2007). Theoretical perspectives for child welfare practice on kinship foster care families. Families in Society, 88(4), 575-582. https://doi.org/10.1606%2F1044-3894.3680

- Kerr, M., & Bowen, M. (1988). Family evaluation: An approach based on Bowen theory. Anchor Books/Doubleday.

- Leon, S., Saucedo, D., & Jachymiak, K. (2016). Keeping it in the family: The impact of a family finding intervention on placement, permanency, and well-being outcomes. Children and Youth Services Review, 70, 163-170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.09.020

- Lindstrom, G., & Choate, P. (2016). Nistawatsiman: Rethinking assessment of Aboriginal parents for child welfare following the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. First Peoples Child & Family Review 11(2). 45–59.

- Makokis, L., Shirt, M., Chisan, S., Mageau, A., & Steinhauer, D. (2010). mâmawei-nêhiyaw iyinikahiwewin. Blue Quills First Nations College.

- McGoldrick, M., Gerson, R., & Petry, S (2008). Genograms: Assessment and intervention. Norton.

- McHugh, M. (2009). A framework of practice for implementing a kinship care program. Social Policy Research Centre University of New South Wales. https://www.arts.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/documents/11_Report_ImplementingAKinshipCareProgram.pdf

- Naquin, V., Manson, S. M., Curie, C., Sommer, S., Daw, R., Maraku, C., Lallu, N., Meller, D., Willer, C., & Deaux, E. (2008). Indigenous evidence-based effective practice model: Indigenous leadership in action. International Journal of Leadership in Public Services, 4(1), 14–24.

- Stangeland, J., & Walsh, C. (2013). Defining permanency for Aboriginal youth in care. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 8(2), 24–39.

- Simard, E. (2019). Culturally restorative child welfare practice: A special emphasis on cultural attachment theory. First Peoples Child and Family Review, 14(1), 56–80.

- Warde, B. (2012). The cultural genogram: Enhancing the cultural competency of social work students. Social Work Education, 31(5), 570-586. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2011.593623

Liste des figures

Figure 1

The Turtle Lodge Relationship Mapping Image

10.7202/1077183ar

10.7202/1077183ar