Résumés

Abstract

Before Iglulik is an archaeological and oral-historical project undertaken to record and document Inuit settlements around Iglulik (Igloolik) during the period preceding the establishment of modern hamlets in the Canadian Arctic in the mid-20th century. The archaeological component of the research consisted of recording and mapping features at Avvajja, an early 20th-century campsite located approximately six kilometers northwest of Iglulik, while the oral history component involved the facilitation of Inuit engagement with these cultural remains. A series of interviews and site visits were held with former residents of Avvajja (Avvajjamiut). To promote cross-generational knowledge transmission, a reunion event at the site was coordinated by the authors for Avvajjamiut and their loved ones. Attendees shared a feast at the site and toured their ancestors’ dwellings, where many stories were shared.

Keywords:

- Iglulik (Igloolik),

- Avvajja (Abverdjar),

- Nunavut,

- oral history,

- Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit,

- archaeology

Résumé

Before Igloolik est un projet d’archéologie et d’histoire orale dont le but est d’inventorier et de documenter les établissements Inuit près d’Iglulik (Igloulik) durant la période précédant l’établissement de villages modernes dans l’Arctique Canadien, au milieu du XXe siècle. L’aspect archéologique de la recherche visait à inventorier et à cartographier les structures archéologiques à Avvajja, un campement du début du XXe siècle situé à environ six kilomètres au nord-ouest d’Iglulik. La composante d’histoire orale consistait à faciliter l’engagement des Inuit avec ces vestiges culturels. Une série d’entretiens et de visites sur l’île d’Avvajja ont été organisés avec d’anciens résidents (Avvajjamuit). Afin de favoriser la transmission intergénérationnelle des connaissances, un évènement de retrouvailles incluant les anciens résidents et leur descendance a été coordonné par les auteurs. Les participants ont d’abord partagé un festin sur le site ; puis, ont visité les habitations de leurs ancêtres, où de nombreuses histoires furent échangées.

Mots-clés :

- Iglulik (Igloulik),

- Avvajja (Abverdjar),

- Nunavut,

- histoire orale,

- Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit,

- archéologie

ᐅᓂᒃᑳᓕᐊᖅ

ᐃᒡᓗᓕᒃ ᐃᑦᑕᕐᓂᑕᙳᖅᑳᖅᑎᓐᓇᒍ ᐊᒻᒪ ᐅᓂᒃᑳᑦ−ᖃᖓᓂᑕᐃᑦ ᐱᓕᕆᐊᒃᓴᖅ ᑲᒪᔭᐅᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᓂᐱᓕᐅᕐᓗᓂ ᐊᒻᒪ ᑎᑎᕋᖅᑕᐅᓗᓂ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᓄᓇᓕᒋᔭᐅᔪᑦ ᐃᒡᓗᓕᒃ ᓴᓂᐊᓂ (ᐃᒡᓗᓕᒃ) ᑕᐃᒪᙵᐅᑎᓪᓗᒍ ᓴᖅᑭᖅᑳᖅᑎᓐᓇᒍ ᐅᓪᓗᒥ ᕼᐋᒻᖑᔪᑦ ᑲᓇᑕᐅᑉ ᐅᑭᐅᖅᑕᖅᑐᖓᓂ 1901-1999 ᐊᑯᓐᓂᖓᓂ. ᐃᑦᑕᕐᓂᑕᕐᕕᒃ ᐃᓚᖓ ᖃᐅᔨᓴᕐᓂᖅ ᐃᓚᒋᔭᖃᖅᑐᑦ ᓂᐱᓕᐅᕐᓂᖅ ᐊᒻᒪ ᓄᓇᙳᐊᓕᐅᕐᓂᖅ ᐃᑦᑕᕐᓂᑕᐃᑦ ᓴᓇᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᐊᕝᕙᔾᔭᒥ, 1901-1999−ᐊᑯᓪᓐᓂᖓ ᑕᒻᒫᕐᕕᒃ ᓇᔪᕐᕕᖓ ᐃᒻᒪᖄ ᐊᕐᕕᓂᓕᑦ ᑭᓚᒦᑕ ᐃᒡᓗᓕᐅᑉ ᓂᒡᒋᐊᓂ, ᐅᓂᒃᑳᑦ ᖃᖓᓂᑕᐃᑦ ᐃᓚᖓ ᐃᓚᒋᔭᖓ ᐃᑲᔪᕐᓂᖅ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᑲᑎᖃᑎᒌᓐᓂᖅ ᑖᒃᑯᓄᖓ ᐃᓕᖅᑯᓯᕆᔭᐅᔪᑦ ᐱᖁᑎᒥᓃᑦ. ᐊᔾᔨᒌᙱᑦᑐᑦ ᐊᐱᖅᓱᕐᓂᖅ ᐊᒻᒪ ᓇᔪᕐᕕᒻᒧᑦ ᐅᐸᒃᑕᐅᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᐱᖃᑎᒋᓪᓗᒋᑦ ᓄᓇᖃᖅᑲᖅᑕᖅᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᑕᐃᔅᓱᒪᓂ ᐊᕝᕙᔾᔭᒥ (ᐊᕝᕙᔾᔭᒥᐅᑦ). ᖁᕝᕙᒋᐊᖅᑯᓪᓗᒍ ᐊᔾᔨᒌᙱᑦᑐᑦ ᐃᓅᖃᑎᒌᒃᑐᓄᑦ ᖃᐅᔨᒪᓂᖅ ᐅᖃᖃᑎᒌᓐᓂᖅ, ᑲᑎᖃᑎᒌᒃᑲᓐᓂᕐᓂᖅ ᐱᓕᕆᐊᒃᓴᖅ ᓇᔪᕐᕕᒻᒥ ᑲᒪᒋᔭᐅᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᑎᑎᕋᖅᑎᑦ ᐊᕝᕙᔾᔭᒥᐅᑦ ᐊᒻᒪ ᓇᓪᓕᒋᔭᖏᑕ. ᑕᐃᒪᐅᓚᐅᖅᑐᑦ ᐃᓚᒋᔭᐅᔪᑦ ᑲᑐᔾᔨᖃᑎᒌᓚᐅᖅᑐᑦ ᓂᕆᖃᑎᒌᓐᓂᖅ ᓇᔪᕐᕕᒻᒥ ᐊᒻᒪ ᕿᒥᕐᕈᐊᖅᑐᑎᒃ ᓯᕗᓕᕗᑦ ᖃᒻᒪᕕᓃᑦ, ᑕᐃᑲᓂ ᐊᒥᓱᑦ ᐅᓂᒃᑳᖅᓯᒪᔪᑦ.

ᑎᑎᖅᑲᐃᑦ:

- ᐃᒡᓗᓕᒃ,

- ᐊᕝᕙᔾᔭ,

- ᓄᓇᕗᑦ,

- ᐅᓂᒃᑳᑦ,

- ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᖃᐅᔨᒪᔭᑐᖃᖏᑦ,

- ᐃᑦᑕᕐᓂᑕᐃᑦ

Corps de l’article

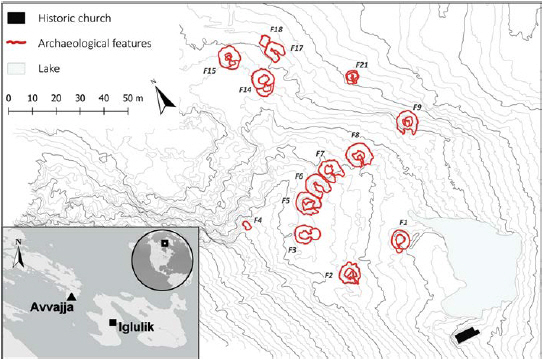

Non-Inuit archaeologists working in Nunavut have paid relatively little attention to the dynamic period preceding the establishment of contemporary Inuit communities in the mid-twentieth century. This is unfortunate, as not only do archaeological features and artifacts from the period abound, but Elders, many of whom are in their 80s and 90s, maintain vibrant memories of these days on the land, sea, and ice, and are keen to share their knowledge with other Inuit, especially younger generations who grew up in contemporary communities, as well as non-Inuit. In this paper, we describe a successful collaboration between Inuit knowledge holders and archaeologists working together toward the reconstruction of Inuit life at Avvajja[1] (NiHg-1), a cold-season camp in Nunavut’s Foxe Basin region. Avvajja was occupied by Inuit from at least the early 1930s to the period immediately preceding the permanent settlement in the municipality of Iglulik (Igloolik) in the 1960s (Figure 1). Avvajja was also the site of the first religious mission established in the region in 1931.

Figure 1

Map of Inuit archaeological features at Avvajja. In 2019, we excavated four test units in a supposed Pre-Inuit feature approximately 35 meters southeast of F9.

We thus present the evolving work of the interdisciplinary Before Iglulik project (2018), the initial goals of which—documenting the occupation history of Avvajja during the first half of the twentieth century—originally involved a straightforwardly-archaeological approach. However, preparatory work for the project in Iglulik showed how complementing the planned archaeological and historical/archival investigation with site visits by former residents (Avvajjamiut) was crucial to building a fuller and more meaningful, picture of recent-historic life at the site. We describe the archaeological work carried out as well as the engagement with Avvajjamiut Elders and their families in the project. We then present firsthand insights from three local participants in the project to gain perspective on a variety of topics they find most relevant to the ethical documentation of cultural history.

Methodology: Archaeology and Traditional Knowledge

Before Iglulik was intended as a one-year pilot project for Limited Choices, Lasting Traditions (2019-2022), an investigation of long-term human reliance on marine mammals in northern Foxe Basin, funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) and led by Sean Desjardins (University of Groningen). In the summer of 2018, a field crew consisting of Desjardins, Scott Rufolo (Canadian Museum of Nature), guide Justin Mikki (Iglulik), and student assistant Noah Mikki (Iglulik) carried out an archaeological investigation at Avvajja. The main objectives were to (1) create a high-resolution map (orthomosaic) of Avvajja using a drone; (2) create a detailed map of semisubterranean cold-season (autumn/winter) sod house features at the site using differential GPS (DGPS) technology; and (3) conduct limited archaeological testing (four 1 m2 test units) of a feature thought to be of Tuniit affiliation (Late Dorset Pre-Inuit; ca. AD 1000 to 1300). No Inuit houses or other features at Avvajja were disturbed during the project.

The archaeological work was complemented by research in the Iglulik Oral History Project (OHP) Archives, and the Deschâtelets-NDC archives of the Oblate Missionary Order (Les Missionnaires Oblats de Marie Immaculée, Richelieu, QC). In January 2018, Desjardins carried out semi-structured interviews in Iglulik with three Avvajjamiut Elders: Herve Paniaq, Julia Amarualik, and Alexina Makkik. These Elders, along with five others—Louis Uttak, Therese Uttak, Matilda Hanniliaq, Madeline Ivalu, and Eulalie Angutimarik—travelled to Avvajja during the 2018 summer field season to share memories about their life there during the early-to-mid twentieth century. Janet Airut of Iglulik provided Inuktitut-English interpretation during all engagements in 2018. In an effort to facilitate dialogue across generations, the Government of Nunavut Department of Culture and Heritage Territorial Archaeology Office coordinated and funded a reunion event at Avvajja toward the close of the 2018 field season. On August 4th, the above-mentioned Elders and approximately 140 of their relatives visited the site, feasted on country food, and traded stories about traditional life in the region.

As a follow-up to the reunion event, in November 2021, LeBlanc facilitated an exchange among three reunion attendees—George Qulaut, Eulalie Angutimarik, and E.H.[2]—who shared stories and impressions of the reunion, as well as other memories relating to Avvajja. The discussion, which underlies much of the reflection in this paper, was wide-ranging but ultimately focused on connection to place and the relationship between archaeology and Inuit priorities to further knowledge about their heritage. Most of the discussion was carried out in Inuktitut, and later translated and transcribed by Rhoda Inuksuuk. The transcripts are held at the Iglulik Oral History Project archives (Nunavut Arctic College).

Avvajja: Setting and Culture History

Avvajja is situated near the southeastern extreme of the Coxe Island group, approximately six kilometers northwest of Itivia (Ham Bay) on the west coast of Iglulik Island. The area is ecologically rich, with a wide variety of marine mammals abundant in the surrounding waters. The Tuniit were the first people to occupy Avvajja. Research carried out at the site by British archaeologist Graham Rowley (in 1940) and Danish archaeologist Jørgen Meldgaard (in 1965) revealed between three and four small, oval-shaped depressions interpreted as Tuniit house pits. These features were excavated by Rowley (1940), who recovered over a thousand cultural objects (artifacts) of various types; most of these objects are currently housed at the Cambridge Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology. Our 2018 excavation of a small Tuniit depression immediately east of the Inuit house row (see Figure 1) produced faunal material, lithic debris, microblades, and a seal-effigy pendant. (The analysis of this cultural material is ongoing.)

Our survey yielded no evidence of a Thule Inuit occupation (e.g., from ca. AD 1250 to 1600) at Avvajja; the reason for this apparent gap in occupation is unclear. What is certain is that by 1930 at Avvajja, Inuit had established a small but prosperous cold-season camp that soon became one of the focal points of colonial encounter in the region. According to the Diocese of Churchill, Inuit from the Iglulik area had learned about Catholicism through contacts with residents of Naujaat (Repulse Bay) and had traveled north to Mittimatalik (Pond Inlet) to request a resident priest for their area (“Thrilling Missionary Work” 1934, 27). In May 1931, Fr. Étienne Bazin (1903–1972), a Roman Catholic Oblate originally from Dijon, France, arrived at Avvajja from Mittimatalik, having traveled mostly by foot.

Upon his arrival at Avvajja, Fr. Bazin constructed a crude structure with spared pieces of wood he had brought with him. The building was used as a chapel, a storehouse, and living quarters. On July 24, 1933, the structure and nearly all its contents were lost in a fire. Fr. Bazin writes, “I had just finished saying mass […] A moment of inadvertence on my part, a candle started the fire, and in a few minutes, all flamed up like a torch. All I could save was the Blessed Sacrament, three small hosts in a pyx, and breaking the window from the outside, I could save my [Inuktitut] prayer book” (“Thrilling Missionary Work” 1934, 23).

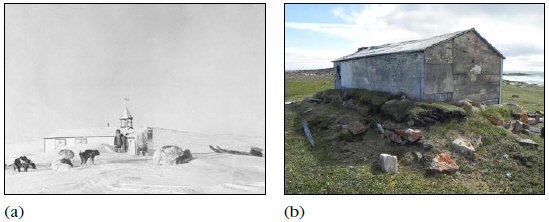

Though Fr. Bazin was alone at Avvajja during this calamity, a local family who had been camping nearby saw the smoke and came to his aid. A few days later, they guided him in building a more locally-appropriate structure using stones from an old cache. The roof was covered with a walrus hide (kauk), as no seal skins were available. Following this event, Fr. Bazin became affectionally known as “Kaumiutaq” (“one who lives under a walrus skin”), a moniker Iglulingmiut still recall with humor (Amarualik 2018a). Eventually, Fr. Bazin was able to construct a new wood-framed church; this was a much sturdier structure than the first one was, bolstered and insulated from the cold on all sides by sod blocks, much like an Inuit cold-season sod house (Figure 2). The Mission church, which was contemporaneous with the Inuit sod houses discussed below, was christened St. Étienne (French for St. Stephen) by the Diocese. To this day, “Kaumiutaq”, who remained in Iglulik until 1948, is generally remembered fondly by the Elders who knew him.

Figure 2

The historic Catholic church at Avvajja

(a) n.d., facing north (photograph by R. Harrington, Library and Archives Canada); (b) 2018, facing southeast. Note the stacked sod and stones surrounding the structure.

At its peak, in the 1940s, Avvajja was led by a charismatic couple, a talented hunter named Ittuksaarjuat and his wife Attagutaaluk, who remains today a much-celebrated figure among Iglulingmiut (Wachowich et al. 1999, 68–72; Mary-Rousselière 1950). Ittuksaarjuat’s influence went far beyond Avvajja. George Qulaut (2021) notes that stories have long circulated about his wisdom and guidance: “I […] knew that there was a well-known leader living [at Avvajja]. Many people from Amittuq[3] had sought his advice; other places did too, like Aivilik[4], Kivalliq[5], East Baffin, Tununiq[6], would come to seek his advice. Ittuksaarjuat was a leader mostly on social issues. That is what I’ve heard.” Attagutaaluk was among the earliest Inuit converts to Catholicism in the Iglulik region. She and her husband were also close confidants to Bazin.

Life at Avvajja: Food, Shelter, and Religion

In addition to establishing themselves as lay spiritual leaders at Avvajja, Ittuksaarjuat and Attagutaaluk worked tirelessly to ensure regular food security for the camp. Prior to the establishment of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) trading post at Iglulik in 1939, the couple would venture regularly to the nearest HBC post at Mittimatalik, exchanging pelts for goods (e.g., tea, flour, sugar, ammunition, and tobacco) on behalf of the entire community (Wachowich et al. 1999, 71–72). Trips were also made to trade at HBC posts in Naujaat (Repulse Bay) and Ikpiarjuk (Arctic Bay). Though such forays provided surplus and luxury supplies, the necessities (i.e., country food) were always plentiful around Avvajja itself (Paniaq 2018a; Makkik 2018a, 2018b). Indeed, the 2018 archaeological crew noted large amounts of animal bones (e.g., of ringed seals, bearded seals, walruses, caribou, and polar bears) scattered across the surface of the site, attesting to past (and continuing) abundance.

Avvajja was used primarily as a fall and winter camp and was occupied alternately by a handful of nearby locales, such as Ikpiarjuk[7]—the site of the community of Iglulik, and Iglulik Point. The latter location is still actively used to stage walrus hunts and cache fermented walrus meat. The remains of a large Thule Inuit cold-season village [NiHe-2] can be found a short distance from the shore. During Thule Inuit times, cold-season houses (qarmat) were constructed using bowhead whale bones, large boulders, and thick rectangular slabs of sod. In recent-historic times, bones were replaced by wooden tent poles or ship masts, and sod slabs were replaced by thinner, cut sod blocks.

The 2018 archaeological survey at Avvajja revealed between 11 and 12 sod houses dating from the early 1930s to late 1950s, in addition to stone caches and graves. Most of the houses are situated approximately 100 m north/northeast of the shore at the base of a large granite outcropping. The overall condition of the site is good, and it is a regular stopover for hunting, fishing, and recreation parties traveling by boat to the channels a short distance northwest of the island. It is also a popular destination during Easter celebrations.

The remains of the houses are roughly circular in shape, measuring between 6.4 and 7.7 meters in diameter (outside wall dimensions). Each house could comfortably accommodate up to seven adults and four children (Amarualik 2018a) (Figure 3). The walls were constructed with stacked sod bricks cut from the broad, flat plain to the north and east of the main house-row. Over time, European architectural features such as wooden doors and window frames were integrated into the sod houses. Until relatively late, the penile skin of walruses and bearded seals was still preferred over glass for windows. Open, central floors were surrounded on three sides by raised gravel sleeping platforms (Paniaq 2018b). Each house featured a central roof-supporting post—usually a wooden boat mast—with its base positioned at the rear of the structure and angled upward. This post supported a sealskin or canvas tent roof, which could be up to two meters high (Paniaq 2018b; Uttak 2018). At the entrance of the house was a cold porch (vestibule) framed with ice blocks obtained mostly from the small pond near the church (Paniaq 2018b). These vestibules (some of which almost as large as the inside living spaces) were used to store clothing and meat (Uttak 2018). Each house had between one and three qulliit (soapstone oil lamps) providing light and heat. There was significant refurbishing and cleaning of houses as they were seasonally reoccupied.

Figure 3

Historic Inuit sod house Feature F8, 2018, facing south toward the entrance passage

In describing daily life at Avvajja, Elders emphasized a sense of great belonging and community. For example, when babies were born, it was customary for each resident to shake the infant’s hand, with an Elder intoning, “You are from Avvajja” (Angutimarik 2018, 2021). The family house of Herve Paniaq was one of Avvajja’s largest. As such, it served as a kind of “community” house, or qaggiq, where people would gather to plan activities and play games (Paniaq 2018b). As children, many of the Elders were given small chores around the camp. When a hunting foray had been successful, Paniaq was often tasked with running from house to house, yelling, “frozen food!” to advertise the bounty; similarly, Uttak was responsible for delivering European goods, such as tobacco, to each household, when they were brought in from the HBC posts (Uttak 2018).

Sometime around 1944, Ittuksaarjuat passed away. He had asked to be buried in a stone cairn on a high point west of Avvajja, as he wished to see the goings-on at Avvajja after he passed (Ivalu 2018; Makkik 2018b; Uttak 2018). Ataguttaaluk outlived her husband by four years, dying in June 1948, aged between 68 and 78 years old. Like her husband, she is widely revered by Iglulingmiut. Her grave near Alarniq on the mainland remains a popular pilgrimage site, and Iglulik’s elementary school is named after her. Even after most families had left Avvajja, the small St. Etienne Church at Avvajja continued for some years to be favored over its intended replacement, the larger St. Stephen’s Church in Iglulik, for its relative warmth and familiarity. Sisters Madeline Ivalu and Alexina Makkik believe their family was the last to leave Avvajja for Iglulik in either 1951 or 1952 (Makkik 2018b).

Crowe (1970) draws a direct correlation between the lower occurrence of walruses in the surrounding waters around 1948 and the abandonment of Avvajja in the late 1950s. However, many Elders recount that near the time of his death, Ittuksaarjuat had declared that Avvajja had been occupied too long and that the land itself had become “too hot”; it had to be abandoned and allowed to “cool down” for some years (Amarualik 2018a; Uttak 2018; Rowley 1985). George Qulaut (2021) argues the English word “hot” is “just a word,” referring not to temperature but rather to a much more complicated phenomenon rooted in pre-Christian cosmological understandings of human-animal/human-environment relationships:

[W]hat Ittuksaarjuat said is true. He’s not the first man to say that, and leaders in other camps were also sensitive to the land as they get to know it. […] It was a common knowledge that they should not live in the same spot for more than three or four years because it gets hot. […] The land reacts if you stay in it too long and it can kill you or your dogs. Or you kill the land by driving away animals, you know when things are growing around it. They know that it’s time to move before any kind of sickness happens either to themselves or their dogs. It was their tradition to keep moving.

Such an understanding does not bode well for long-term Inuit well-being in Nunavut’s modern communities. Informal discussions the authors have had with Elders revealed a common understanding that many modern illnesses, such as cancer and respiratory sickness, either did not exist or were less common when Inuit were moving seasonally. This longstanding view likely contributed to the widespread notion—supported by recent social-scientific research—that too much time spent away from the land and concentrating activities in a single place can be detrimental to multiple aspects of Inuit health and well-being (Cunsolo Willox et al. 2013; Robertson and Ljubicic 2019; Ward et al. 2023).

Belonging and Reconnection

On August 4, 2018, a reunion event facilitated by Sylvie LeBlanc of the Nunavut Department of Culture and Heritage and the Before Iglulik researchers was attended by more than 140 people, mainly Avvajjamiut and their descendants. By design, there was limited on-site organization on the part of the researchers beyond the coordination of boat transportation and food preparation. The authors were present to facilitate and respectfully observe the sharing of stories and memories across generations as Elders moved from house to house, telling stories about their respective house and reminiscing about relationships and life on the land (Figures 4a and 4b).

Figure 4

(a) Iglulingmiut Elders arriving at Avvajja for a knowledge-sharing event, 2018;(b) Elders (from l. to r.) Herve Paniaq, Louis Uttak, Therese Uttak, Matilda Hanniliaq, and Julia Amarualik at Avvajja, 2018.

In 2021, three Iglulingmiut who had attended the 2018 reunion—George Qulaut, Elder Eulalie Angutimarik, and E.H.—described to us how different it had been to visit Avvajja with their relatives and Elders who had lived there, and how the reunion had changed their perspectives about and strengthened their feelings of belonging and connection to the site.

George Qulaut’s parents resided at Avvajja:

I’ve heard many stories from my mother and father about living in Avvajja, but they seemed just like stories, so I had no personal connection to Avvajja. I was a little child when I went south, and I was gone for a long time. By the time I came back, I had no sense of identity, I didn’t know if I was Inuk or white. […] I’ve heard many stories from my mom talking about times when they lived in Avvajja […] My father was twelve years old when they came up with his parents Ukajuituq and Ittikutuq from Chesterfield Inlet. My grandfather Itikkutuq was originally from this area, who had gone down there with Qatuttalik. They came in on that small ship to Igloolik [Island] and worked their own way to Avvajja. They incidentally ended up with a couple they didn’t know before named Qattalik and Saqpisuk, who are my other grandparents who already had a sod house there. It was the leader of Avvajja [Ittuksaarjuat] who organized them to share that sod house. So, they shared their place when my father was twelve and my mother was even younger, when they were still too young for a relationship. Both [sets of] parents had no idea that their children would marry later on as they did when they came of age.

[…]

Having heard all these stories of Avvajja, it’s like a place of my parents. They both had a special connection to Avvajja. As for myself, I never went to Avvajja until I was a teenager when we started going up there to slide. We had Ski-doos then. We were the first young people to have Ski-doos, so we would go sliding and climbing. It was just like a playground for us, no other special connection other than the fact that I knew my parents had lived there.

[…]

It just sounded like old stuff, and I didn’t think there would be any connection to my life. Much to my surprise, we were gathered in Avvajja [during the 2018 reunion], where I dealt with my own issues and began my healing journey. I became more aware of where I came from after seeing where my ancestors had lived and seeing their old sod houses. I found out that there was a large sod house shared by both grandparents. Uqajuittuk was on the left side and Qattalik was on the right side. That moment made me realize my history and my roots when I saw how they had all lived together. I was happier afterwards and it took away stigma, and that was the beginning of my healing journey.

Eulalie Angutimarik was born at Avvajja on November 30, 1943, and spent her earliest years there:

As for myself, Avvajja is an important place to me because Avvajja has been occupied throughout our history. It’s a very old place, possibly from the very beginning of time. I am one of the people who have lived in Avvajja. I have seen our old sod house, and it was clearly explained to me because I don’t recall being there when I was a baby. […] When I saw our old sod house later on, it was explained to me that this is the sod house where my parents and adoptive parents lived.

[…]

We were once hired to do a project in Avvajja in recent years. [Herve] Paniaq asked me if I had been to the sod house where I was born […] I said no, I’ve been to Avvajja one time in spring when all the old sod houses were still covered in snow, so I couldn’t see anything. […] Paniaq said, “Let’s go see your birthplace so that you will know, because I don’t think your relatives would show it to you.” […] [He] took me to where there were four sod houses; when we got to one of them, [he] said, “This was where your parents lived when you were born.” I was born in a qarmaq, a sod house in Avvajja. When I saw the old sod house, my thoughts were, like, “So, this is where my parents lived, and this is where I got adopted.”<CIT>

Eulalie’s daughter (E.H.) had also attended the reunion, and like George spoke at length about how her impression of Avvajja changed after the event:

E.H.: I feel like a new kind of person. I was born later than qarmait [qarmaq in plurial] days, when they lived in sod houses, nor did I ever get sent away to go to [residential] school. But living here [in Iglulik], Avvajja was always like part of Iglulik when I was growing up because we always went there [to Avvajja] towards the end of school year for picnics. For that reason, I’ll think of Avvajja as part of Iglulik. I always knew since childhood that my mother was born in Avvajja and that it was a special place. […] So many of us would go at the same time […] to Avvajja for a picnic. I kept going even after school years were over, I went every spring. It’s an annual event for us and it’s like a playground, more like a place to go for fun. […]

E.A.: That [the 2018 reunion] was when I felt more included by my mother’s family because I always knew that my mother was adopted […].

E.H.: I also knew that we returned to your biological parents, but they never seemed to include us in the family. That reunion was the first time where they were ever included. I remember being included in that reunion to Avvajja. It was uplifting for me to be there with my biological uncle and aunt, it was a welcoming feeling. That was the time I got to see my dad’s old sod house too. I was also shown my mother’s old house. It was a realization for me to see where my parents and grandparents had lived before my time. It was very emotional. I was touched emotionally, and this is something I will never forget for the rest of my life.

E.A.: I’ve always known that I was born in Avvajja, but my adoptive mother never told me exactly where I was born. Since I went to that reunion, I have been more content with myself to find out so many details that one summer. Really to a point where our old sod house was pointed out and they knew everyone’s exact spaces inside that sod house where I was born. […] My mind was more at ease after having seen and been to Avvajja.

E.H.: That was when I realized how long people have been living in Avvajja for so many years. When I was going to school it was like a playground for us even though I’ve heard that my mother was born there, but never realized how much further the history goes. It was my first time seeing all these old sod houses after all the years I had been going there.

The Legacy of Avvajja and the Future of the Past

The recent-historic period of Inuit history (i.e., from the twentieth century onward) has received relatively little attention by archaeologists. This transformative period was one of profound and often traumatic change for Inuit society, significantly affecting traditional harvesting, food security, and traditional belief systems (see Laugrand and Oosten 2010). The shift toward year-round settlement in communities has distanced many people from the special places of their ancestors. While gaining archaeological knowledge about such places is important, we argue that researchers should seek out opportunities to support and facilitate reconnecting and knowledge-transmission experiences. At Avvajja, scientifically-oriented archaeological work, experiential site visits, and the meaning-making reunion event all illuminated our various understandings of social change(s) in recent-historic times and provided a forum for former residents of Avvajja and their families to reify their experiences and understandings of the place.

At the close of the 2021 group interview, the conversation with participants turned to the relationship between Inuit and archaeology:

E.H.: As for myself, I know that we do not have Inuit graduate archaeologists, and this is usually done through [non-Inuit] archaeological students. As long as they record all the findings and keep documentation with the intention of returning the artifacts to Nunavut, it’s ok with me.

E.A.: It’s ok with you?

E.H.: Yes, I’m ok with it because archaeologists preserve their findings that we wouldn’t have found. As long as they return it to Inuit when Inuit are equipped to get these artifacts back, that has been my thinking.

E.A.: I, myself, am very protective of Inuit artifacts made by our ancestors. Inuit had no tools; they made all their tools themselves like using rocks which is a very hard work, making knives and ulus. They hunted with harpoons before they had guns. I would want artifacts to be returned to us and to be put into museums because even our generation didn’t see that time and even local people are at awe when they see old pictures. They wonder. If they could be returned and put in museums with information of what it was, where it came from and with Elders explaining the use of these artifacts.

George continues:

I’m named after an archeologist [Jørgen Meldgaard] through baptism. My father wanted me named after him. (My father couldn’t pronounce “Jørgen,” which was pronounced that way by Greenlanders.) […] Archaeology is special to me and it lives with me and I totally understand different perceptions and different views of different generations. Such as my grandfather’s generation, which didn’t like what archaeologists do. Through shamanism influence, even the children weren’t allowed to be around or to dig any old stuff, but I always knew that. Because these artifacts have owners, and you leave them alone. The older generations were very against the work of archaeologists.

[…]

My children’s understanding is, like, […] “Why is there an archaeologist?” Like, white people, “Why?” They need to learn how Inuit lived before. Any findings must be properly stored so that they’ll understand and learn from it. We don’t know the future of these artifacts, but once there’s a proper place to keep them, our youth can learn facts from them. So, they should be preserved for the future. The young people can learn from these stories, and they can ask questions to Elders about their history of that time.

[…]

My grandfather’s reaction would’ve been, “They [archaeologists] don’t know what they’re talking about, just books and print, it’s all trash.” That part of my knowledge keeps me wondering how we can work together to make it useful for future generations. How can our children and grandchildren use this information? Will they all be speaking more English? Will Inuktitut be less used? Will they be relying more on written material? Will they take Inuit oral history seriously? All these things are still tangled up in my mind.

Yes, I support the archaeological work, but I’ve also argued and spoken against [archeologists] at a university level. I made many people cry, archaeologists from Denmark, United States, and Canada. I made them cry because they don’t recognize Inuit, so it’s like that. Yes, I can spend a whole day on archaeological issues. Yes, I can give my support because this is today 2021. Do we need to change? There’s an old saying that what you swallow will come out the other end. This is in my blood and I’m always working on how I can help in the future. [I am] Ready to work with [the Nunavut Department of] Culture and Heritage, as well as archaeologists or anyone else who are working in that area because I can speak on it.

Conclusion

Until an ideal means of meaningfully integrating—rather than pillarizing or essentializing—scientific and Indigenous knowledge systems is developed, it is incumbent upon non-Indigenous archaeologists to prioritize local/descendant interests for meaningful knowledge construction. We are certainly not the first to engage these issues; indeed, there is a rich body of work on Indigenous-focused and “heart-centered” methodologies (Supernant et al. 2020; Hodgetts and Kelvin 2020; Schneider and Panich 2022; see also the introduction to this special issue). However, we have shown how archaeologists can both learn from and facilitate reconnection to and intergenerational sharing of traditional knowledge. The work at Avvajja also demonstrates how Inuit priorities for research—in this case, a focus on family, connection to place, and the recent past, more generally—can be effectively centered throughout the research process without “diluting” scientific goals or rigor. We acknowledge that each effort to co-create knowledge will be different, and we believe that an integrative approach, coupled with flexibility in developing the research in accordance with local interests can be of significant benefit for everyone involved.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the community members—especially the Elders—of Iglulik; the Municipality of Iglulik and Mayor Celestino Uyarak; George Qattalik and the Iglulik Hunters and Trappers Association; the Government of Nunavut, Territorial Archaeology Office; Levy Uttak of Igloo Tourism and Outfitting (Iglulik); staff at the Canadian Museum of Nature (Natural Heritage Campus, Gatineau); staff at the Canadian Conservation Institute (Ottawa); Elaine Sirois (Archives Deschâtelets-NDC, Les Missionnaires Oblats de Marie Immaculée); Justin Mikki; Noah Mikki; Salomon Mikki; Scott Kadlutsiak and Jeena Kadlutsiak; Janet Airut and Rhoda Inukshuk. The research was funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO), the Groningen Institute of Archaeology (University of Groningen), the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC), and the Government of Nunavut, Department of Culture and Heritage Territorial Archaeology Office (Iglulik). Finally, we thank the two anonymous reviewers for their kind and constructive feedback on the manuscript.

Notes

-

[1]

Variously transliterated in English and French as Abverdjar, Avjavar, Abvayak, and Avvajjaq.

-

[2]

This participant chose to be identified by her initials only.

-

[3]

A large customary region extending roughly from Igloolik Island, south—including Sanirajak (Hall Beach)—to the Amitoke Peninsula.

-

[4]

The region including the present-day community of Naujaat (Repulse Bay).

-

[5]

A large region consisting of the western coast of Hudson Bay and including much of the inland caribou-hunting ranges.

-

[6]

The region surrounding the present-day community of Mittimatalik (Pond Inlet), north Baffin Island.

-

[7]

Not to be confused with the contemporary community of Ikpiarjuk (Arctic Bay).

References

- Amarualik, J. 2018a. Interview/discussion facilitated by S. Desjardins, Igloolik, Nunavut.

- Angutimarik, E. 2018. Group interview/discussion facilitated by S. Desjardins, Avvajja, Nunavut.

- Angutimarik, E.2021. Group interview/discussion facilitated by S. Leblanc, Igloolik, Nunavut. Archived at the Igloolik Research Centre, Igloolik.

- Crowe, K. J. 1979. A cultural geography of northern Foxe Basin, N.W.T. Report to the Northern Scientific Research Group, Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, Ottawa.

- Cunsolo Willox, A., S. L. Harper, V. L. Edge, K. Landman, K. Houle, J. D. Ford, and the Rigolet Inuit Community Government. 2013. “The Land Enriches the Soul: On Climatic and Environmental Change, Affect, and Emotional Health and Well-being in Rigolet, Nunatsiavut, Canada.” Emotion, Space and Society 6: 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2011.08.005.

- E. H. 2021. Group interview/discussion facilitated by S. Leblanc, Igloolik, Nunavut. Archived at the Igloolik Research Centre, Igloolik.

- Hanniliaq, M. 2018. Group interview/discussion facilitated by S. Desjardins, Avvajja, Nunavut.

- Hodgetts, L., and L. Kelvin, eds. 2020. “Unsettling Archaeology.” Canadian Journal of Archaeology (special issue) 44 (1).

- Ivalu, M. 2018. Group interview/discussion facilitated by S. Desjardins, Avvajja, Nunavut.

- Laugrand, F., and J. G. Oosten. 2010. Inuit Shamanism and Christianity: Transitions and Transformations in the Twentieth Century. Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Makkik, A. 2018a. Interview/discussion facilitated by S. Desjardins, Igloolik, Nunavut.

- Makkik, A. 2018b. Group interview/discussion facilitated by S. Desjardins, Avvajja, Nunavut.

- Mary-Rousselière, G. 1950. “Monica Ataguvtaluk, Queen of Igloolik.” Eskimo 16: 11–14.

- Paniaq, H. 2018a. Interview/discussion facilitated by S. Desjardins, Igloolik, Nunavut.

- Paniaq, H. 2018b. Group interview/discussion facilitated by S. Desjardins, Avvajja, Nunavut.

- Qulaut, G. 2021. Group interview/discussion facilitated by S. Leblanc, Igloolik, Nunavut. Archived at the Igloolik Research Centre, Igloolik.

- Robertson, S., and G. Ljubicic. 2019. “Nunamii’luni quvianaqtuq (It is a Happy Moment to Be on the Land): Feelings, Freedom, and the Spatial Political Ontology of Well-being in Gjoa Haven and Tikiranajuk, Nunavut.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 37 (3): 542–560. https://doi.org/10.1177/026377581882112.

- Rowley G. 1940. “The Dorset culture of the Eastern Arctic.” American Anthropologist 42 (3): 490–499.

- Rowley, S. 1985. “Population movements in the Canadian Arctic.” Études Inuit Studies 9 (1): 3–20.

- Schneider, T. S., and L. M. Panich, eds. 2022. Archaeologies of Indigenous Presence. Gainesville: University of Florida Press.

- Supernant, K., J. E. Baxter, N. Lyons, and S. Atalay, eds. 2020. Archaeologies of the Heart. Springer Cham.

- “Thrilling Missionary Work and Extreme Hardships of Father Bazin, O.M.I.” Nov. 1934. St. Marienbote: 23–28.

- Uttak, L. 2018. Group interview/discussion facilitated by S. Desjardins, Avvajja, Nunavut.

- Uttak, L. Group interview/discussion facilitated by S. Desjardins, Avvajja, Nunavut.

- Wachowich, N., A. A. Awa, R. K. Katsak, and S. P. Katsak. 1999. Saqiyuq: Stories from the Lives of Three Inuit Women. Montréal and Kingston, Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Ward, L., M. J. Hill, A. Nikashant, S. Chreim, A. Olsen Harper, and S. Wells. 2023. “‘The Land Nurtures Our Spirit’: Understanding the Role of the Land in Labrador Innu Wellbeing.” InternationalJournal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18 (10): 5102. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105102.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Map of Inuit archaeological features at Avvajja. In 2019, we excavated four test units in a supposed Pre-Inuit feature approximately 35 meters southeast of F9.

Figure 2

The historic Catholic church at Avvajja

Figure 3

Historic Inuit sod house Feature F8, 2018, facing south toward the entrance passage

Figure 4