Résumés

Abstract

This essay examines the reactions of several Inuit women to an identification system whereby from 1941 to 1978 the Canadian government required the Inuit to wear small numbered disks. The author presents each Inuk woman’s personal perspectives, including her own, through narratives, interviews, and songs. The second part discusses the historical context of the “Eskimo disk list” system and its repercussions decades after it was discontinued.

Résumé

Cet essai examine les réactions de plusieurs femmes inuit devant un système d’identification que le gouvernement canadien imposa aux Inuit de 1941 à 1978: ceux-ci devaient porter un petit disque sur lequel figurait le numéro qui leur avait été attribué. L’auteure présente le point de vue personnel de chacune de ces femmes inuit, incluant le sien, à travers des récits, des entrevues et des chansons. La deuxième partie discute du contexte historique du système «des numéros de disques inuit» et de ses répercussions plusieurs décennies après son abandon.

Corps de l’article

Utsisimajuq (‘knows by experience, has tasted it’)

Ujamiit sounds like a nice, melodic Inuit word, but it represents a system that the Government of Canada implemented for the “tagging” of an entire group of Aboriginal peoples. Ujamiit (‘necklaces’) with small individually numbered disks were expected to be worn by every Inuk person at all times, as a “practical” means to validate Inuit status. This was the “Eskimo disk list” system (Smith 1993), where each disk was stamped “Eskimo Identification Canada.”

Ujamiit became one of the missing items I needed to prove to my own people that I am who I say I am. I had only one thing, her atiq (‘name’). Her named was Angaviadniak, a Pallirmiut woman. She is my maternal anaanatsiaq (‘grandmother’) and I know of her through the oral passing down of Inuit knowledge, Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit. Qaujima is the verb ‘to know,’ and Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit literally means ‘the things that Inuit have known for a long time’ (Stern 2010: 33). It is traditional knowledge from Inuit elders, and how Inuit know who, what, and where they are in this world. It is, as Jaypetee Arnakak says:

a set of teachings on practical truisms about society, human nature and experience passed on orally (traditionally) from one generation to the next […]. It is holistic, dynamic and cumulative in its approach to knowledge, teaching and learning […]. IQ […] is most readily manifested in the knowledge and memories of Nunavut Elders […].

in Martin 2009: 184

Very simply put, Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit “is about remembering; an ethical injunction that lies at the root of Inuit identity” (Tester and Irniq 2008: 61).

The Eskimo disk system is remembered by two Inuit female singers who bravely released songs about it in 1999 and 2002. Susan Aglukark and Lucie Idlout each recorded the words reflecting the continued impact that the Inuit disk system had on themselves, their families, and Canadian Inuit communities in general. Aglukark and Idlout put into songs a rememberance of the disk system and, in doing so, they exposed what it did to them. Inuit elder Saullu Nakasuk states, “I can be asked what I know. I state only what I know” (Nakasuk 1999: 1). Aglukark and Idlout, like Nakasuk, speak from direct personal experience through song and maintain the InuitQaujimajatuqangit. Like the songs of those Inuit artists, who sang their impressions about the disk system years after it had been discontinued, my life history, like that of all Inuit, begins with the words of our elders, their stories, their songs, and their poems. Here is my story.

I am Norma Dunning. I am a disk-less Inuk. I was born into a time when the Eskimo identification system was still in practice in Canada but I did not receive a disk. My Inuk mother never had one, neither did my two older brothers and two older sisters who were born in Churchill, Manitoba, in the “E1” district of the Canadian Arctic. We were all born during the period from 1941 to 1971, when the Government of Canada issued disk numbers to identify the Inuit (Alia 1994, 2007; Roberts 1975). Although most Aboriginal people in Canada were identified by name and number, the Inuit were the only ones to be “tagged” in this way.

I knew little about this system, and it became a thing of significance to me only when I applied in 2001 for beneficiary status[1] as an Inuk originally from the community of Whale Cove, Nunavut. My application was handled as a three-year process and loaded with form upon form to be completed for myself and my three sons. I lacked, however, certain pieces of paper and information that would have made this procedure much less time-consuming. First, my own anaana (‘mother’) was never issued a birth certificate. She was born into a paperless world, where time was not marked by calendar dates or clocks. Time was marked by seasons, but the writing down of information on paper was not in practice. She was born into a time when you knew who you were by the people who loved you best, when the point of every day was to be sure of having food to eat, and when life was marked by the use of basic survival skills. Her life was a life that did not fit the government guidelines of marking and measuring that she was Inuk. When the disks were being issued in her area, the E1 area of the Eastern Canadian Arctic, my mother was away at residential school. She and her two sisters spent eight long years, without a summer or Christmas break, at a residential school in Winnipeg. The RCMP did not go into the city to issue disks to children who were busy surviving a different form of a government-imposed system. She and her sisters were overlooked.

According to government guidelines, my mother now is missing two important pieces of information: first, a birth certificate, and second, a disk. She never applied for or received Inuit beneficiary status. Why would she? She knew who she was and did not require government-issued proof. She lived her life in many ways as a paper-less Inuit Canadian citizen. I have not had the same life experience. Applying for beneficiary status became a task that was loaded with Nunavut government measures and guidelines. Because I could not provide my mother’s birth certificate, I was casually asked over the phone by a female Inuk civil servant for my mother’s disk number. This question is nowhere on the beneficiary status application form. The question was asked as a way of connecting my blood to Nunavut. Disk numbers had become proof of Inuit ancestry.

Digits, pin numbers, credit card numbers, and social insurance numbers have all become commonplace means of identification in our world today. Whether we are withdrawing money from an ATM or applying for a job, in our present-day lives, we make use of identity numbers regularly. We are told to memorise them, to protect our PIN, and never to keep the same login ID for any amount of time, but we are in the 21st century. The Government of Canada, in 1941, thought it had arrived at the perfect method of taking care of their Inuit subjects by issuing numbers to substitute for Inuit names. “The first Qallunaat who were required by their purpose in the Arctic to record Inuit names spelled them as they heard them. Their imperfect ear for Inuktitut steered them in directions as diverse as their individual backgrounds. Their superior formal education was rendered comically inexact in this exercise!” (Nungak 2000: 33)

What the government never considered was the importance of a name to the Inuit. The naming of a child in traditional Inuit culture has practical, sacred, and spiritual purposes. A child was given one main, asexual name by an elder who usually chose the name of someone who had recently died. Saladin d’Anglure (1977: 33 in Alia 1994: 14) states that “Inuit believe that the essential ingredient of a human being is its name. The name embodies a mystical substance which includes the personality, special skills, and basic character which the individual will exhibit in life.” The name of an Inuk not only tells others who he/she is but also explains kinship ties and how that person is connected within a group in terms of his/her skills and personal traits. An Inuit name tells others what to expect or not to expect. To an Inuk, a name was the most important item carried throughout life. I knew my grandmother’s name and, while waiting to have my application for Nunavut beneficiary status processed, I began to look through disk lists for her name and the number that would be next to it. Initially, I thought that I could use this as proof if my application was in any way questioned. This information would be my evidence of being “Eskimo.”

Like my application, my life, like all Inuit lives begins with the words and memories of Inuit elders. I am unable to consult my own mother and grandmother at this time, but I was able to consult one Inuk elder. Her name is Minnie Aodla Freeman. Minnie is 75 years old and has lived through many forms of Canadian government oppression and processes placed upon the Inuit. She was a victim of residential school, a patient at a tuberculosis hospital, a recruited government interpretor, and a young girl who was expected to wear the government-issued necklace. Minnie has vast life experience[2] and understanding that I lack. She lived during the time of the disk system, and I was privileged to interview Minnie on that subject. In keeping with Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit guidelines, I turn to the words and experience of a respected Inuk elder.

Uqalaittuq (‘one who says little wisely, knows what she is talking about’)

I first knew Minnie when we both served on the Native Studies Dean Selection Committee at the University of Alberta in the fall of 2011. She was the elder on the committee and I was a student, but our time together made me feel like I was becoming her student in small ways. While we were on the committee I became Minnie’s driver, and we spent time together in my car, with Minnie giving the directions on how to go from here to there. She knew Edmonton inside out and backwards. Every side street and back alley was a familiar route to her, away from the main areas, and I learned how to get to places without streetlights or bumper-to-bumper traffic.

It is 9 a.m. on January 16, 2012, and I am sitting in Minnie Aodla Freeman’s living room in Edmonton, visiting her for my research on the Eskimo disk identification system. I am surrounded by mementos from the North, memories of the time she lived there and when her husband Milton researched there. It is a very cold morning. The temperature is -35°C, and I feel very fortunate to be in this room with someone I consider my elder. I have brought Minnie a glass swan containing a rosebud. She removes it from the tiny wrapped box and thanks me. She places it on her coffee table, exclaiming, “I thought it was a goose!” We both laugh, and I tell her that I wish it had been a goose.

Minnie looks comfortable on her couch in her black sweats and red T-shirt with the words “Pow Wow” running across it; she looks well and healthy, and her smile is constant. I feel uneasy because I have been taught not to ask an elder questions; rather, the elder begins to talk and we listen. I am a beneficiary of Nunavut, do not speak Inuktitut, and have never set foot in my supporting community of Whale Cove. I am an urban Inuk woman. I am from the south, and yet Minnie does not treat me as someone who knows nothing about being a northern Inuk. She treats me with respect, grace and, more importantly, inclusiveness.

Minnie asks me whether I want to know “about the numbers,” and I nod. Minnie received her disk as a child and feels she knows little about the subject. She speaks only from her experience, as is the Inuit way. Minnie was born in 1937 on the Cape Hope Islands, in the Qikiqtaaluk region. She tells me that the “RCMP gave out the necklaces in the North,” and adds, “The government was terrible to the Inuit and their children. If their parents couldn’t come out of the bush the kids were just taken away from the community and put into residential school.” She says the disks arrived in her childhood area around 1947-1948. “The government didn’t know what to do with last names so they gave numbers out,” she tells me, “like a dog tag.” Minnie does not seem angry about the system. She says practically and sympathetically that the Inuit did not mind the tags because it was explained that the government could not understand their names, so they had “to wear a leather string.” Minnie was E9-434, her brother E9-436, her mother E9-433, her father E9-431, and her grandmother E9-430. The Aodla family was grouped between E9-430 and E9-440.

Were the disk numbers included on income tax forms? She responds, with a look of shock, “The government automatically did it [taxes] for us.”[3] Did Inuit people sign their tax forms? “No, they treated us like we absolutely knew nothing.” Minnie tells me that her father and grandfather knew how to sign their names in syllabics, but the government insisted that they sign with “Xs,” and it was not until the 1960s that they were allowed to use their syllabic signatures.

Of the disk system she says, “I think it helped the government to know who was family. It didn’t help us—we just wore them for the government.” The necklaces were not made of real leather; they irritated the neck so they were only worn on the days when a boat was coming into harbour. We share a good laugh. “The Inuit complained that their children at school were asked to call out their disk number rather than a name and that they occasionally got mail addressed to their disk number alone” (Scott et al. 2002: 28). Was Minnie ever called by her disk number at school? “No.”

In 1953, when she was 16 years old, Minnie worked as a translator at the Mountain Sanatorium in Hamilton, Ontario, where many Inuit were sent for tuberculosis treatments. She also took up nursing along with her cousin and two other Inuit girls, although only one of them graduated. Was her number used when she was in the TB hospital? She tells me that she was “called Minnie the whole time” and wonders whether the hospital knew about the numbers before some Inuit started to give them out.

Sirimajuq (‘grateful again and again’)

Although white people continued to infiltrate and try to assimilate the Inuit in the late 1940s, the culture remained. Like driftwood being battered against a shoreline, waves and waves of white people and their enforcement of the disk system only created a deepening of Inuit culture by the Inuit themselves. Resignation is the only word I can think of to describe Minnie Aodla Freeman’s feelings towards the Eskimo disk system. If a camera were to pan back over Minnie’s life history, government interference would be a repeated theme. Submission and surrender to government practices occurred regularly during her early life. The less intrusive one was to make her wear a leather-like necklace with the number E9-434 stamped onto a round piece of red fibred-cloth. Wearing a tag was just another thing she did to comply with government people. Wearing a tag can be seen as a sigh of resignation in Minnie’s early life, a sigh representing the weariness of yet one more obstacle that the Government of Canada placed in front of Minnie—the wearing of a disk, another item in her life to be accepted.

I have deep respect for Minnie. I will carry and cherish this talk with her throughout my lifetime. She sees the world through traditional Inuit eyes and for one hour offered me that lens. I hear an almost silent sigh when Minnie speaks of the disk system. She does not allow audible anger or disrespect to come forth. Instead, she maintains a sense of dignity and composure. Did the government of the day really think that the Inuit would keep this tag attached to their bodies at all times? Anger, resentment, and regret never enter the conversation, simply because such feelings have no place in being there.

Sullusarut (‘mouth music’)

Minnie’s composure does not mean that anger, resentment, and regret are never used as a form of expression in Inuit tradition. “In Inuit culture, there has always been a tradition that thoughts and feelings, of anger or regret should be expressed, so that they do not turn against oneself or others. Songs were a means of doing this” (Imaruittuq 1999: 201). Orpingalik, a Netsilik elder said, “Songs are thoughts which are sung out with the breath when people let themselves be moved by a great force, and ordinary speech no longer suffices. […] When the words that we need shoot up of themselves—we have a new song” (Lowenstein 1973: xxiii). Culturally, the Inuit do not outwardly express anger. “Cross-cultural research suggests that some cultures, such as the Inuit lack anger […] because they do not blame individuals for their actions. […] Inuit do not merely suppress anger; they appear not to feel it either” (Crawford et al. 2004: 65). Instead, song is used as a means of expressing those thoughts and feelings that need to be set free from within an Inuit soul. Two song types, presented by two female Inuit artists, Susan Aglukark and Lucie Idlout, are representative of the true feelings of the Inuit of Canada and the continued impact of the Eskimo disk system. The traditional song types and methods used by each artist, and released to the Canadian public, are a statement of the lasting impressions of the disk system.

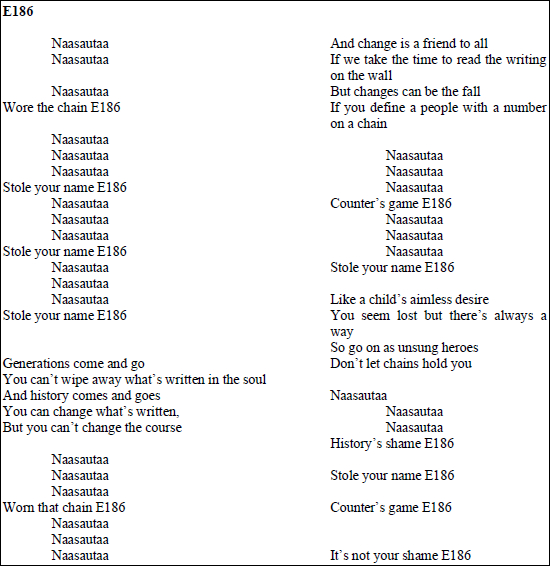

The song E186 was released on Susan Aglukark’s 1999 album titled “Unsung Heroes” (Figure 1). According to Aglukark in an email response to my query, this song is her own “artistic contribution to a time in Inuit history” and she considers it to be a “personal response” as she “chose not to use a real disk number […] E186 is not an assigned number.” It is a soft song of resistance, and I would argue that it reflects the traditional type of Inuit song known as a pisiq. A pisiq “tells of things that happened in the past” (Owingayak 2012: 1) and are “sung with a drum” (Imaruittuq 1999: 201) as the dominant instrument. A guitar should not be used in the modern form of a pisiq (Owingayak 2012: 1), and “E186” follows this form in both the dominance of the drum and lack of guitar accompaniment.

Aglukark is singing of and to the heroes who survived a system that removed names and cultural identity and in many ways tried to erase the faces of Inuit. Repetition of the words, “stole your name E186,” followed by the chorus of the word naasautaa (‘numbers’) does bring to mind a long column of Inuit names being crossed out by a pencil and a number replacing the name of an actual human being. Aglukark encourages the Inuit by telling us all to “go on as unsung heroes/Don’t let chains hold you/It’s not your shame.” In her calm use of lyric and musical notes, Aglukark speaks back to the Canadian government in the same hushed way the Eskimo disk system has been left off the pages of Canadian history.

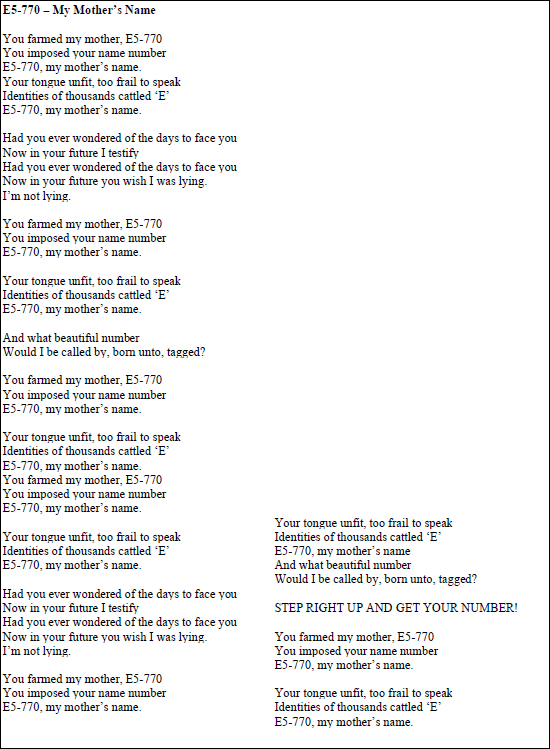

Lucie Idlout sings about the disk system in an opposing and traditional Inuit form of song, an iviutit (Figure 2). Iviutit “were used to embarrass people, to make fun of them, to make fun of their weaknesses” (Imaruittuq 1999: 201). Iviutit were a traditional way of evening the score, a legal and binding method of maintaining peace and order within an Inuit group, a way of stopping physical revenge (ibid.).

Figure 1

E186. Music and lyrics by Susan Aglukark and Chad Inschick (interpreted as the traditional Inuit song type pisiq)

In an email Idlout told me that she wrote this song because she “hated the idea of her mother being referred to by anything other than her proper name” and “wanted to expose the country because at the time the song was written Canada was rated as one of the top countries in the world to live in.” In her words, this was “a fucking joke considering how many treaties have been broken and how many Aboriginal peoples live in poverty.” She concludes, “I wrote it in the style I did to make people listen to a voice that is rarely heard or recognized, and issues are rarely spoken or acknowledged in a spoken form. Music makes people hear you.”

Figure 2

E5-770 – My Mother’s Name. Music and lyrics by Lucie Idlout (interpreted as the traditional Inuit song type iviutit)

Idlout does title her song with a real, registered disk number, “E5-770.” This was the disk number belonging to her mother, Leah d’Argencourt Idlout. Idlout’s song is hard-driving rock with an enjambment of a circus-like shout of “Step Right Up and Get Your Number.” This song does not shy away from poking fun at the Government of Canada and its silent ignoring of what the Eskimo disk system did and continues to do to the Inuit. Idlout does not mince words; she is direct and taunting in her choice of the words for the chorus of the song “E5-770, My Mother’s Name” and her repeated use of the sentence, “Identities of thousands cattled ‘E’.”

It is as though Idlout is at a traditional feast, in a qag’e[4] where all feasts were held, with the Prime Minister of Canada, and is challenging him to a song duel. No lyrical punches are spared and Idlout sticks to the traditional iviutit method of embarrassment. Knud Rasmussen wrote of the iviutit duel as follows:

No mercy must be shown; it is indeed considered manly to expose another’s weakness with the utmost sharpness and severity; but behind all castigation there must be a touch of humor, for mere abuse in itself is barren, and cannot bring about any reconciliation. It is legitimate to “be nasty”, but one must be amusing at the same time, so as to make the audience laugh; and the one who can thus silence his opponent amid the laughter of the assembly, is the victor, and has put an end to the unfriendly feeling.

in Lowenstein 1973: 124

Through her song E5-770 - My Mother’s Name, Idlout rightly leaves a stain of embarrassment on this country, and throws into the face of the authorities a system that tried to replace humanity with digits.

At this point, one could perhaps argue that everyone in Canada has a social insurance number, which is government-issued and can be likened to a disk number. The social insurance number (SIN) was created in 1964 for the administration of the Canada Pension Plan and the Unemployment Insurance Program. In 1967 the SIN began to be used for income tax returns. It did not, however, replace a human name, as did the disk number in 1941. As for the Band List and the Indian Land Registry System, they identified a person as a registered Canadian Indian, signifying equity in access to Indian lands or claims to land (Smith 1993: 64). A disk number replaced a name and had no bearing on land or land claims, the only purpose being state control (ibid.). Individuals from First Nations were never expected to wear their “R-card” around their necks. Canadians in general never had their names scrutinised, removed, or replaced by numbers.

Qaujisarniq titiqqatigut qanuiliuqtauqattarnikunik (‘the study of past events using written sources’)

Inuit names historically dumbfounded missionaries who were among the first to be sent into the North to try to make sense of the populations living there. A sexless, singular name[5] was difficult for them to understand. Missionaries arrived in Labrador in the late 18th century, and a century later in the rest of the Canadian Arctic. The North West Mounted Police (RCMP) were sent to the Western Canadian Arctic in the late 19th century and to the Eastern Arctic in the early 1920s. Two decades later, the Government of Canada tried to demonstrate “effective sovereignty” (Smith 1993: 48) over the North as World War II raged on. “This would involve a large series of measures to show that Canada not only claimed sovereignty in the Arctic but maintained active patrol and administration of its waters, lands, resources, and peoples” (ibid.). The Government of Canada had to discover to whom they were obligated, who were these peoples, and what were their names.

Missionaries had trouble recording Inuit names; the spelling and pronunciation were difficult for them, and so the Inuit people were instructed to use Biblical Christian names (Alia 1994: 26). “Inuit had their names changed by whalers, missionaries or others […] this created more problems as there were several individuals with names such as Paul, Adam, Eve, Mark or Jessie. […] the Inuit had difficulty pronouncing the names, they were ‘Inuiticized’ […] Adam became Atami, Eve became Evie, Matthew became Maitiusi and John became Joanasi” (Crandall 2000: 43). Since Inuit names were without gender, there would be a boy child with the name Mary, which was spoken in Inuktitut as “Imellie” (Alia 2007: 28). Missionary ledgers became grossly confused. Northern medical administrators realised that the writing down of Inuit names was not working, and for a brief time fingerprinting the Inuit was attempted (Smith 1993: 49). But by mid-1935 only 22 Inuit had been fingerprinted. There were concerns that such a method could be seen as implying criminal activity, and that questions might be asked in Parliament (ibid.: 50). Fingerprinting was discontinued, and the Government of Canada devised a category-based method that would avoid the use of Inuit names entirely.

The disk system was implemented in 1941, and “created a system of knowledge by which the Canadian state exercised an ‘intensive surveillance’ over the Eskimo population. Quite literally, ‘the Eskimo population’ became a creation of state practice in order to meet state interests of governance” (ibid.: 44). That year, the Government of Canada had “10,000 disks ‘ready for distribution […]’ and to be supplied to enumerators for the decennial Census of Canada” (Smith 1993: 55). Along with the enumerators, the RCMP were mandated to issue the disks. In a 1997 interview John Arnalukjuak stated, “We were told by the RCMP not to lose those disks so we were fearful that uh, if we ever lose them, because that, in those days, the RCMP were really bossy and you know, so we feared them. So we were told not to lose them” (in Kulchyski and Tester 2007: 211). Rachel Uyarasuk recalled: “I was afraid to lose mine […]. We were told not to lose them […] I didn’t wear it around my neck. All my children’s and mine […] I tied them together. And I lost them! I was ever scared” (ibid.). Uyarasuk realised her family disks were lost while they were travelling from one camp to another. The family returned to their first camp and “even picked on the ice, looking for them. […] I had to tell someone because we had lost them and I was very scared. I thought I was going to be arrested” (ibid.). As commented Kulchyski and Tester (ibid.), “Her story reveals how seemingly simple administrative solutions created significant pressures and burdens on the Inuit.”

An entire group of Canadian Aboriginal people did realise the importance of having the disks on them at all times in some form, whether around their necks or in their pockets. The Inuit of Canada had succumbed to the “tagging” and “herding” of a government-imposed system. Major McKeand, Superintendent of the Eastern Arctic, stated that “[…] once the Eskimo realizes that the white man wants him to memorize an identification number and use it in all trading and other transactions, the Eskimo will fall in line” (in Roberts 1975: 23-24). In 1945, the Family Allowance Act of Canada defined an Eskimo person as “one to whom an identification disk has been issued” (Smith 1993: 59), and “Family allowance payments made to Eskimos at that time were only in the form of supplies, not cash” (ibid.: 60). The intrusive wearing or memorising of a disk number had indeed made the Eskimos fall in line. By the mid-1940s in Canada, the Inuit began to define themselves by the wearing of a disk because it meant they could receive government aid, medical care or, more importantly, the basic necessities of life. Indeed, statistics in 1965 prepared by “[t]he Economic Council of Canada drew particular attention to the fact that the average age at death for all Canadians […] was a little over sixty-two years while the average age for the Inuit was twenty years […] and for Natives 36 years, there were 108.8 deaths per 1,000 live births for the Inuit” (Guest 1980: 159).

Within its first decade, the Eskimo disk system became an important piece of digital information for each Inuk to commit to memory. Zebedee Nungak wrote:

The disk number has a special significance in our lives, even with the abundance of identifications we carry today. Every Eskimo once committed his or her E number to memory, a handy I.D. for all purposes. One of a mother’s great duties was keeping track of all her family’s E-numbers. Even in this age of e-mail-dot-com, I know many who still use their ujamik numbers as a PIN for charge cards, a house number, or a label for their belongings. Losing my disk in early childhood has never erased the number that was so much a part of my early life.

Nungak 2000: 37

Nakinngaqpin? (‘Where do you come from?’)

How uncommon, then, is it to be asked for your mother’s disk number over the phone when applying for Nunavut beneficiary status in 2001? I can only say it is not unusual when the historical context of a disk number is put into a government framework. When we examine the consequences to an Inuk who was raised to believe that all government interactions in Canada were based on a disk number, the casual question over the phone becomes a part of a normal conversation about identity. When we seek to understand the anxiety of not knowing one’s disk number and the result of not being given access to food or medicine, social assistance, child welfare, housing, care of the elderly—the same government benefits extended to any other Canadian citizen without a disk number—then the importance of a disk number becomes clear. The impact of the Eskimo disk system continues to be generational. Aglukark and Idlout sing out about it, and I am asked for a disk number reference 23 years after the system was discontinued.

It is a system that remains consigned to silence in our country. It is important that Inuit artists continue to speak out about and against this system. It is a system that the Government of Canada has never apologised for or spoken about publicly. It is a system that collared its victims—the Inuit of Canada.

It is also a system that suffered from administrative problems. The first issuance of the disks in 1941 was found to have several inconsistencies. It was soon discovered that the RCMP were not including disk numbers on their reports back to Ottawa. There was a shortage of disks in some areas, and in one case “certain Eskimos on the Boothia Peninsula destroyed their disks after receiving them” (Roberts 1975: 14). There was fear of a “multiplication of errors and ultimately, chaos” (ibid.: 17). As Major McKeand noted, “owing to their nomadic, non-tribal life it is impossible to visit every Eskimo family annually” (ibid.: 19). It was also discovered that the Department of Vital Statistics in Ottawa had not been doing its part to transcribe disk information: “To date no attempt has been made to enter onto our Vital Statistic birth returns, completed prior to the 1941 census, the identification numbers which have since been issued to each Eskimo, nor has this been done on birth returns received since 1941, on which the identification number was omitted” (ibid.: 42).

With the introduction of family allowances and the rigid regulations governing their payment, a second mass issuance of disks was made in the Canadian Arctic with the first batch being taken back by those in authority.

The stringent control required for the distribution of Family Allowances brought into being an effective registration program. The Arctic was divided into twelve districts West, (W1, W2, W3) and East (E1 to E9). New disks were issued with blocks of numbers allocated to each district. The old disks were recalled and replaced, with new ones, small fibre disks free of design and stamped simply with a district designation and number, for example: E3-1212.

Roberts 1975: 25

Because the data had not been recorded in Ottawa, the original disks were recalled. Twenty-five years later, Inuit began to question why the system was still in practice.

In 1969, Simonie Michael, the first elected aboriginal Canadian, spoke at a council meeting of his frustration about the continued use of disk numbers by the Canadian government: his mail was still addressed to “Simonie E7-551.” The press picked up the story and soon afterward, the government in the territories undertook the task of registering people under a second name.

Heritage Canada n.d.

In 1970, during the Northwest Territories centennial year, Project Surname was born (Figure 3). Abe Okpik, a respected Inuk politician, headed the project to identify each Inuk in Canada by a first and last name, and not by a disk number. Not once were the Inuit given the choice to be called by their main singular and genderless name. Okpik (2005: 102) says, “I had to draw up a pamphlet and send it to every community, through the RCMP, explaining my little project. I sent it to all the communities in both Inukitut and English. […] Some people were very cooperative, but some said, “Why are you taking our number away? It worked for us all this time!”

Figure 3

Cover of the booklet issued for Project Surname, where disks are being tossed out of the Arctic (source: Okpik 1970).

Again, the Government of Canada was imposing a naming system that was not conducive to traditional Inuit naming practices. Again, the Inuit were being forced to absorb a governmental practice that did not recognise or respect their cultural norms. Again, the Inuit had to submit to a change imposed by the Canadian government.

Surnaming has always been tied to class distinctions and power inequities. A surname can be a mark of “distinction” for those who inherit or pass it to future generations. Or it can be a mark of subjugation, a way of being followed or found if you’re in an underclass […]. It can also signify cultural absorption, a way of “normalizing” a culture considered not “normal”. Motives for giving Inuit surnames ranged from the opportunity to be “like all other Canadians” to the requirement to be “like everyone else.” Surnaming is sometimes a way of controlling less powerful people.

Alia 2007: 70

In the year 1970 the Government of Canada took on a mission to give all Inuit surnames and to complete this task within a year. The result, as Father Mary-Rousselière (1972: 18) wrote, was that “lists have been submitted, everyone has received a birth certificate. A word describes the situation almost everywhere: it is a real mess.” Mary-Rousselière then raised a very important question that the Canadian government never answered in 1971:

If the Eskimo must absolutely adopt a surname for the benefit of the bureaucrats, why could he not keep an intermediary name—recognized by the Vital Statistics—his own Eskimo name […]? A fairly amusing coincidence! It is precisely at the time when a move is afoot to rid the Eskimos of the registration numbers that a social security number is bestowed on each one of the whites in the North West Territories. Let us wager that few objectors will be found!

Mary-Rousselière 1972: 12-13

The irony is simple: why not issue a social insurance number to the Inuit in replacement of their disk numbers and leave their names alone entirely? Why not have a social insurance card number with a singular Inuit name on it? The Government of Canada was working hard at trying to get all its citizens to operate with first and last names as the Eskimo disk system was being dismantled. In trying to tame the Inuit, the Government of Canada created one mess after another. Never once were the Inuit asked what they would like or how they would like to be recognised. Never was the task of learning an Inuit name attempted by the dominant group. Numbers and surnames, however, have never separated the Inuit from their culture or taken away who they are to each other. Abe Okpik tells the story of how he was named:

When we name a child, the namesake lives on. The soul dies and the body is gone, but you have the name, and you have to raise the child as the person you knew. […] there is a drum dancing song in the West that, before my namesake Auktalik died, he taught my father and three brothers to sing. They still use that. It’s a kind of chant, to make people happy. We call it atuvalluk. It means leaving a song of love […].

Okpik 2005: 54

Whether through the imposed Eskimo disk system or through Project Surname, the Inuit of Canada continued to embrace and carry on with their own traditions. The Inuit kept their naming tradition alive within each of their groups, and the names given to Inuit children remained a sacred and practical tradition. Generations continued to leave songs of love to one another. In Nunavut, a legal council has been set up to correct the errors of Project Surname:

In 2000 a new law review committee called Maligarnik Qimirrujiit was formed in Nunavut. Among their assigned tasks is a review of the effects of Project Surname and the implementation of legal correction of some of the errors. Peter Irniq has campaigned for this for many years and is gratified to see it “finally becoming a reality”.

Alia 2007: 115

As of the year 2012, not all of the names of the Inuit in Canada are correct. All of this could have been avoided had the Government of Canada instructed the first missionaries to learn the language and write the names of the Inuit as spoken by the Inuit themselves. The need for disks and the projects that followed could have been avoided had the Government of Canada respected and learned the Inuit language and culture. Instead, Inuit artists today inform the Canadian public of the Eskimo disk system through their words, their poems, and their songs.

Naggavik (‘time to end’)

How did I end up being approved for Nunavut beneficiary status without a disk number? It was all very simple and Inuit-tradition based, very Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit. My oldest brother, who was born in Churchill, Manitoba, sat with a group of elders there, alongside one of my northern cousins. The elders had him state his name and the name of our mother and grandmother and it was the elders who remembered them and who they were within that community—the E1 district. It was these elders who agreed to have us receive Nunavut beneficiary status because all life begins with the words and the memories of the elders.

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

Beneficiaries of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement (1993) who are eligible for benefits and programs.

-

[2]

A woman of many talents, Minnie published a book about her life (Freeman 1978).

-

[3]

One anonymous reviewer insisted that government staff completed tax forms for the Inuit at their request, hence not as an officially assigned task but as a personal favour.

-

[4]

A qag’e is a snow house used for times of drumming, dancing, and singing.

-

[5]

Traditionally, the Inuit did not have family names.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Dr. Keavy Martin who acted as supervisor on my research project, and also to Dr. Brenda Parlee who was my first reader. I presented a preliminary version of this text at the 18th Inuit Studies Conference in Washington, D.C., in October 2012. Travel support was provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

References

- AGLUKARK, Susan, 1999 Unsung Heroes, CD, Mississauga, EMI.

- ALIA, Valerie, 1994 Names, Numbers, and Northern Policy Inuit, Project Surname and the Politics ofIdentity, Halifax, Fernwood Publishing.

- ALIA, Valerie, 2007 Names and Nunavut: Culture and identity in the Inuit Homeland, New York, Berghuahn Books.

- CRANDALL, Richard, 2000 Inuit Art - A History, Jefferson, McFarland.

- CRAWFORD, Rhiannon, Brian BROWN and Paul CRAWFORD, 2004 Storytelling in Therapy, Cheltenham, Nelson Thomes Ltd.

- FREEMAN, Minnie Aodla, 1978 Lifeamong the Qallunaat, Edmonton, Hurtig Publishers.

- GUEST, Dennis, 1980 The Emergence of Social Security in Canada, Vancouver, UBC Press.

- Heritage Canada, n.d. Listening to Our Past - Project Surname (web site at: http://www.tradition-orale.ca/english/project-surname-102.html).

- IDLOUT, Lucie, 2008 E5-770 My Mother’s Name, song on YouTube (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LyCun8Le3jg).

- IMARUITTUQ, Emile, 1999 Pisiit Songs, in Jarich Oosten, Frédéric Laugrand and Wim Rading (eds), Perspectives on Traditional Law, Iqaluit, Nunavut Arctic College, Interviewing Inuit Elders, 2: 201-219.

- Kulchyski, Peter and Frank James Tester, 2007 Kiumajut (Talking Back), Vancouver, UBC Press.

- Lowenstein, Tom (translator), 1973 Eskimo Poems from Canada and Greenland. From material originally collected by Knud Rasmussen, Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press.

- MARTIN, Keavy, 2009 “Are we also here for that?”: Inuit qaujimajatuqangit-traditional knowledge, or critical theory?, Canadian Journal of Native Studies, 29(1-2): 183-203.

- MARY-ROUSSELIÈRE, Guy, 1972 The New Eskimo Names: A Real Mess, Eskimo, 3(spring-summer): 18-19.

- Nakasuk, Saullu, 1999 Introduction, in Jarich Oosten and Frédéric Laugrand (eds), Introduction, Iqaluit, Nunavut Arctic College, Interviewing Inuit Elders, 1: 1-12.

- NUNGAK, Zebedee, 2000 E9-1956, Inuktitut, 88: 33-37.

- OKPIK, Abraham, 1970 Project Surname, Yellowknife, Government of the Northwest Territories.

- OKPIK, Abraham, 2005 We Call it Survival. The Life Story of Abraham Okpik, edited by Louis McComber, Iqaluit, Nunavut Arctic College, Life Stories of Northern Leaders, 1.

- OWINGAYAK, David, 2012 David Owingayak quoted in the section “Music” of the web site Inuit Art Alive (http://www.inuitartalive.ca/index_e.php?p=126).

- RASMUSSEN, Knud, 1999 Across Arctic America: Narrative of the Fifth Thule Expedition, Fairbanks, University of Alaska Press.

- ROBERTS, A. Barry, 1975 Eskimo Identification and Disk Numbers: A Brief History, Ottawa, Department of Indian and Northern Affairs, Social Development Division.

- SALADIN D’ANGLURE, Bernard, 1977 Iqallijuq ou les réminiscences d’une âme-nom inuit, Études/Inuit/Studies, 1(1): 33-63.

- SCOTT, James C., John TEHRANIAN and Jeremy MATHIAS, 2002 The production of legal identities proper to States: The case of the permanent family surname, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 44(1): 4-44.

- SMITH, Derek G., 1993 The Emergence of “Eskimo Status”: An Examination of the Eskimo Disk List Sytem and Its Social Consequences, 1925-1970, in Noel Dyck and James B. Waldram (eds), Anthropology, Public Policy, and Native Peoples in Canada, Montreal, McGill-Queen’s University Press: 41-74.

- STERN, Pamela R., 2010 The Daily Life of the Inuit, Santa Barbara, Greenwood.

- TESTER, Frank James and Peter IRNIQ, 2008 Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit: Social History, Politics and the Practice of Resistance, Arctic, 61(1): 48-61.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

E186. Music and lyrics by Susan Aglukark and Chad Inschick (interpreted as the traditional Inuit song type pisiq)

Figure 2

E5-770 – My Mother’s Name. Music and lyrics by Lucie Idlout (interpreted as the traditional Inuit song type iviutit)

Figure 3

Cover of the booklet issued for Project Surname, where disks are being tossed out of the Arctic (source: Okpik 1970).