Résumés

Abstract

This paper examines the cultivation of global competence in Singapore schools through a compulsory programme known as Character and Citizenship Education (CCE). The syllabuses of CCE, information from selected school websites on CCE and relevant official documents were examined by mapping them with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s conception of global competence. The results reveal a communitarian orientation that emphasizes social attachments, shared interests and communal goals. Specifically, the concept of global competence is framed and positioned as achieving collective well-being and valuing human dignity and diversity. The example of Singapore suggests the significance of communitarian underpinnings for global competence, thereby adding to the existing literature on the diverse formulations of the notion of global competence across education systems.

Keywords:

- Character and Citizenship Education,

- communitarianism,

- global competence,

- Singapore

Résumé

Cet article examine la culture de la compétence globale dans les écoles de Singapour par le biais d’un programme obligatoire connu sous le nom d’Éducation à la citoyenneté et à la formation du caractère (Character and Citizenship Education – CCE). Les programmes de la CCE, des informations sur la CCE extraites des sites Web d’écoles sélectionnées et des documents officiels pertinents ont été examinés en les mettant en correspondance avec la conception de la compétence globale de l’Organisation de coopération et de développement économiques. Les résultats révèlent une orientation communautariste mettant l’accent sur les liens sociaux, les intérêts partagés et les objectifs communs. Plus précisément, le concept des compétences globales est formulé et positionné comme un moyen d’atteindre le bien-être collectif et de valoriser la dignité humaine et la diversité. L’exemple de Singapour suggère l’importance des piliers communautaristes sur lesquels repose la notion des compétences globales, ajoutant ainsi à la littérature actuelle sur les diverses formulations de cette notion des compétences globales au sein des systèmes éducatifs.

Mots-clés :

- Éducation à la citoyenneté et à la formation du caractère,

- communautarisme,

- compétences globales,

- Singapour

Corps de l’article

Introduction

Global competence, with its emphasis on cross-cultural sensitivities and empathic concern for others, is an integral component of 21st century competencies for students to thrive in a cosmopolitan world. Unsurprisingly, policymakers around the world have included this notion in the school curriculum. To date, there is an impressive body of literature on the furtherance of global competencies in mainstream education (Mansilla & Wilson, 2020; Sälzer & Roczen, 2018; Sidhu & Kaur, 2011). There are also variations of global competence across countries. Sälzer and Roczen (2018) observed that the notion of global competence in English-language research emphasizes individual intercultural communication, whereas the focus for the same concept in German-language research is on global and sustainable development. It is therefore essential to examine the diverse sociocultural formulations and assumptions of global competence.

A review of literature shows there is limited attention on the conceptualization of global competence for students in Asia; there are some exceptions, such as studies in China and Japan (Han & Zhu, 2022; Hu & Hu, 2021; Jiaxin et al., 2024; Sakamoto, 2022; Tsang et al., 2020; Mansilla & Wilson, 2020). A common theme in the small number of publications on global competence in Asia is the mediating role of local histories, institutions, norms, worldviews, and lifestyles. Han and Zhu (2022) drew attention to a tendency to privilege “Anglo-American ideologies and practices” as part of the “international elements” of programmes for students in China. In the same vein, Sakamoto (2022) reported that Japanese students do not share some attributes of global competence which are valued in the mostly Western literature, such as self-expression and independent thinking. Clearly, there is a need for more research on the varied understandings and practices of global competence across cultures, including in Asia.

Addressing this research gap, this article focuses on the cultivation of global competence in Singapore through the national curriculum. Singapore has been selected for our examination as it was the top performer in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) assessment on global competence in 2018. Intended for 15-year-old students across the globe, the PISA assessment studies the extent to which students are ready to live and thrive in a global economy and intercultural landscape. At first glance, the fact that Singapore emerged top in the 2018 PISA study on global competence may give the impression that its construct of global competence is aligned with OECD’s interpretations and assumptions of global competence (PISA, 2020). But this assumption overlooks the pluralistic, contextualized, and socioculturally embedded notions of global competence that vary across education jurisdictions.

What has remained under-explored is how different education systems interpret the concept of global competence and promote it to students through the national curriculum. In the case of Singapore, the Ministry of Education (MOE) has emphasized the cultivation of global competence prior to the 2018 PISA assessment. Back in 2012, the attribute of global awareness was already underscored in a nation-wide, compulsory programme known as Character and Citizenship Education (CCE) for all public schools. Accordingly, a person with global awareness is well-versed in cultural interactions, and is cognizant of international trends and their interplay with local communities (MOE, 2021). Notably, the syllabus of CCE has been revamped in 2021, making an analysis of this programme as well as other relevant syllabuses and official documents pertinent to the research on the conceptualization and theoretical basis of global competence.

The model of global competence conceptualized by the Organisation for Economic and Co-operation Development (OECD) has been selected as the conceptual framework for this study. The OECD (2018) states that its global competence framework aims to “support evidence-based decisions on how to improve curricula, teaching, assessments and schools’ responses to cultural diversity in order to prepare young people to become global citizens” (p. 6). At the outset, it needs to be acknowledged that the before-mentioned global competence model was intended by OECD as a policy framework and not an analytical tool for research. However, OECD’s global competence is still useful for this study as the policy framework matches the aim of this study, which is to analyze the policy initiative of promoting global competence in Singapore schools through CCE. Furthermore, the employment of OECD’s global competence as a conceptual framework for this paper gives us the opportunity to critique it and examine the extent to which this framework is helpful to analyze the CCE syllabus in Singapore. To be sure, OECD’s global competence model has been subject to some critique—I shall return to this point and give details in a later segment. Nevertheless, the adoption of OECD’s model as a conceptual framework does not imply the acceptance of this model’s ideological influences, worldviews, presuppositions, and policy outcomes. Rather, this study takes the before-mentioned model, especially its four dimensions of global competence, as the starting point to identify, clarify, question, and generate ideas in relation to the research topic.

The research question for this study is how the concept of global competence is positioned and framed in CCE. The syllabuses of CCE, information from selected school websites on CCE and related official documents were subjected to content analysis through mapping them with the OECD document of global competence as the standard. This article proceeds as follows: an introduction to the concept of global competence, with a special focus on OECD’s framework of the notion. The second part of this paper explains the research method, followed by a report of the research findings and discussion. The last segment delineates the key implications for the concept of global competence arising from the example of Singapore.

The Concept of Global Competence

Global competence is widely regarded as a key attribute for students in an interconnected world (OECD, n.d.). A multidimensional concept that is contested and evolving, global competence is the subject of diverse definitions, frameworks, and strategies. For example, Kang and colleagues (2018) defined global competence as “the comprehensive capability to live, communicate, and work in a multiculturally interconnected world” (p. 684). Underscoring the synthesis of theory and practice, Mansilla and Wilson (2020) defined global competence as “the capacity and disposition to understand and act on issues of global and intercultural significance” (p. 7). Boix Mansilla and Jackson (2011) described globally competent individuals as those who

are aware, curious, and interested in learning about the world and how it works. They can use the big ideas, tools, methods, and languages that are central to any discipline (mathematics, literature, history, science, and the arts) to engage the pressing issues of our time. They deploy and develop this expertise as they investigate such issues, recognizing multiple perspectives, communicating their views effectively, and taking action to improve conditions.

p. xiii

Global competence is closely related to the notion of global citizenship. Global citizenship, as the name implies, transcends allegiance to one’s country to possessing “a sense of belonging to a broader community and humanity” (UNESCO, 2015, p. 14). Global citizens extend their relationships and obligations to people outside their political units on the basis of “universally shared values such as non-discrimination, equality, respect and dialogue” (UNESCO, 2019, para 2). The United Nations (n.d.) stated that the desired outcome of global citizenship education is to develop responsible and active global citizens who demonstrate respect for all people and evince a sense of belonging to a common humanity.

What is common for global citizenship and global competence is the transition from local horizons, interests, connections, and agendas to those at the international level. As mentioned earlier, global competence revolves around the recognition, appreciation, and communication of universal, inter/cross-cultural and cosmopolitan issues, concerns, and relationships (Mansilla & Wilson, 2020). To nurture global citizens and global competence, schools are encouraged to engage students in “projects that address global issues of a social, political, economic, or environmental nature” (United Nations, n.d., para 1).

OECD’s Global Competence

The OECD’s (2018) model of global competence is arguably among the more well-known and widely adopted definitions and frameworks (Tan & Tan, 2014). OECD (2018) defined global competence as “the capacity to examine local, global and intercultural issues, to understand and appreciate the perspectives and world views of others, to engage in open, appropriate and effective interactions with people from different cultures, and to act for collective well-being and sustainable development” (p. 7). The concept of global competence is further explicated through four target dimensions of everyday life (OECD, 2018, pp. 7–8):

1. the capacity to examine issues and situations of local, global and cultural significance (e.g., poverty, economic interdependence, migration, inequality, environmental risks, conflicts, cultural differences and stereotypes);

2. the capacity to understand and appreciate different perspectives and world views;

3. the ability to establish positive interactions with people of different national, ethnic, religious, social or cultural backgrounds or gender; and

4. the capacity and disposition to take constructive action towards sustainable development and collective well-being.

The four dimensions of global competence are buttressed by four interrelated factors: knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values. Briefly, knowledge refers to information concerning international issues and intercultural awareness. Skills are cognitive and behavioural capacities and include “numerous skills, including reasoning with information, communication skills in intercultural contexts, perspective taking, conflict resolution skills and adaptability” (OECD, 2018, p. 14). The third factor is attitude which encompasses a disposition of openness, respect for cultural plurality and global mindedness. Finally, values centre on treasuring human dignity and diversity that ensure equality and fairness towards all and eschewing discrimination and inhuman treatment of others.

A Critique of OECD’s Global Competence

OECD’s formulation and orientation of global competence has been criticized by researchers (Chandir & Gorur, 2021; Cobb & Couch, 2018; Engel et al., 2019; Grotlüschen, 2018; Idrissi et al., 2020; Ledger et al., 2019; Robertson, 2021; Sakamoto, 2022; Sälzer & Roczen, 2018; Tan, 2024). For example, Chandir and Gorur’s (2021) research showed that “there was a clear, Western or global north bias in the scenarios implied in the questionnaire” (p. 21) from PISA test of global competence. Space constraints do not permit this paper to elaborate on the criticisms of OECD’s global competence model. This article shall instead focus on a prominent critique that is pertinent to the research topic: the individualistic presupposition of OECD’s global competence against a neoliberal backdrop. Bailey et al. (2023) maintained that despite “the OECD claims to attend to collective aims, such as the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals,” “it presents an inherently individualistic measure, which is embedded in neo-liberal views of the purpose and forms of social change” (p. 371). Neoliberalism calls attention to the attributes, skills, and competencies individuals need to survive and thrive in a rapidly changing, volatile, uncertain, and internationally-competitive market economy (Cobb & Couch, 2018). Unsurprisingly, governments across the world have embraced human about preparing young people for the international marketplace (Ledger et al., 2019). As explained by Engel and colleagues (2019):

The literature on global competence refers to the specific aptitudes and actions of individual citizens (or workers), thereby embodying more of a skills focus—i.e., what a person can and knows to do. Frequently the emphasis is on the specific proficiencies an individual possesses that provide “a competitive edge” for upward social and economic mobility.

p. 122

OECD’s (2018) individualistic presupposition for global competence does not mean that it has totally ignored the place of community in its conception. Using the example of Ubuntu, OECD (2018) stated, “Collective identity, relationships and context (as impacted by historical, social, economic and political realities) all become major emphases in other cultural discourses on global competence” (p. 19). But the notion of collective identity and associated terms are not incorporated into OECD’s (2018) interpretation of global competence (Grotlüschen. 2018; Ledger et al., 2019).

Research Background

The advancement of global competence for students in Singapore takes place against the backdrop of the multi-ethnic, multi-linguistic and multi-religious composition of the city-state. A young country with a total population of 5.7 million, Singapore residents are comprised of 76% Chinese, 15% Malay, 7.5% Indian, and 1.5% others (Prime Minister’s Office, 2019). Arising from the various ethnic groups (known locally as “races”) in Singapore are the respective mother tongue languages such as Chinese, Malay, and Tamil, with English being the lingua franca (Tan, 2012, 2019). Accompanying the ethnic diversity is religious pluralism; the majority of the population identifying themselves as Buddhists, followed by Christians, Muslims, Taoists, Hindus, and those with no religion (Ho, 2021, Jun 16). The rich ethnic, linguistic, and religious varieties in Singapore make the fostering of cross- and intercultural understanding and appreciation, which is included in global competence, a necessity in Singapore.

In Singapore, global competence is fostered through a whole-school approach but largely through CCE (Tan & Tan, 2014). Among the goals of CCE are for students to “develop respect and appreciation for our socio-cultural diversity, and learn how to empathise with and relate to others who are different from themselves”; define and refine “one’s sense of purpose based on the current world context students are living in” and being “resilient in the face of disruptions in the local and global context” (MOE, 2020a, pp. 26, 28, also see MOE, 2021). In 2011, value-centric and need-based strategies and policies were emphasized. This was signalled by the then Minister of Education Heng Swee Kiat in 2011 (Tan, 2019). Heng launched the CCE framework, which brought together National Education, Values Education, Education and Career Guidance, as well as Cyberwellness and Sexuality Education. This was based on ground-up feedback from numerous stakeholders in the education system. The value-centric focus aligns well with global competence education as it deals with equipping the students with the attitude, values, and mindset that are vital for handling global outlook, perspectives, and issues.

Research Method

The research question is: How is the concept of global competence positioned and framed in CCE in Singapore? This research study relies on the method of content analysis, which is a research tool that focuses on the existence of certain words/phrases, ideas or messages within a text. A total of 43 documents related to CCE are analyzed, comprising two CCE syllabuses (for primary and secondary levels), eight school CCE programmes as specified in the schools’ websites, and 33 official speeches and media replies regarding CCE programmes.

The process of content analysis for this study was guided by Bengtsson’s (2016) four stages: Stage 1: Decontextualization, Stage 2: Recontextualization, Stage 3: Categorization, and Stage 4: Compilation. In the first stage of decontextualization, the meaning units in the text was identified by asking the question: “what is going on?”. The “text” for this study referred to the CCE syllabus, official speeches, and media replies on CCE, and CCE programmes conducted in selected schools in Singapore. All main topics and keywords in the OECD’s framework of global competence (4 dimensions and factors) were also listed. Each meaning unit that has been identified was given a code based on the open coding process. Using an inductive coding system, codes were generated in an iterative manner, and a coding list was created. In the second stage of recontextualization, all areas of the contents had been covered in relation to the research question were checked. To do so, the original text was read again, this time alongside the coding list that contained the identified meaning units. For this study, the CCE syllabus, official speeches and media replies on CCE and the CCE programmes conducted in selected schools were analyzed based on the OECD’s list of the four dimensions and factors.

The third stage was categorization where categories and condensation of extended meaning units were created. Themes that referred to the overall concepts of underlying meanings were generated. The process was guided by the research question on global competence, thereby ensuring that the categorization was based on the data that were obtained in the first two stages. The final stage of compilation involved drawing conclusions from the data collected. Both manifest and latent analyses were adopted: the former focused on the original meanings and contexts, whereas the latter centred on implied meanings in the text. This stage also involved checking where the new findings on global competence were compared with the current literature.

Research Findings

Systematically, all the information in the documents were analyzed by the second author and guided by Bengtsson’s (2016) four stages. For the purpose of mapping the main themes in documents, tables were used to sort and categorize themes, determined categories according to OECD dimensions and factors, and identified messages and meanings that are found in CCE documents. Table 1 shows the breakdown of the OECD’s Dimensions (D) and Factors (F) that were extracted from the content analysis of documents related to CCE.

Table 1

OECD’s Dimensions and Factors Extracted from Documents Related to CCE

The abbreviations mentioned in the table are as follows:

D1: the capacity to examine issues and situations of local, global, and cultural significance (e.g., poverty, economic interdependence, migration, inequality, environmental risks, conflicts, cultural differences, and stereotypes);

D2: the capacity to understand and appreciate different perspectives and world views;

D3: the ability to establish positive interactions with people of different national, ethnic, religious, social or cultural backgrounds or gender; and

D4: the capacity and disposition to take constructive action towards sustainable development and collective well-being.

F1: Knowledge

F2: Skills

F3: Attitudes

F4: Values

The above table is the tabulation of dimensions and factors extracted from the documents (i.e., syllabuses for primary and secondary levels, selected official speeches, official speeches and media replies). Table 2 summarizes the highest and lowest coded dimensions and factors in the documents related to CCE:

Table 2

The Highest and Lowest Coded Dimensions and Factors in Documents Related to CCE

The highest number for Dimension 4 shows the priority placed by the education authority and schools on motivating students to take concrete steps to improve their society in the long run. That Factor 4 (Values) is the highest number and Factor 1 (Knowledge) is the lowest number point to the goal of CCE to go beyond transmitting factual information to inspiring the students affectively. Putting together Dimension 4 and Factor 4, the desired outcome of CCE is to inculcate in students core values such as respect, care and empathy, and spur them on to work towards the larger good locally and globally.

The relative low number for Dimension 3 does not signify that cross-cultural understanding and communication are unimportant. Rather, a probable explanation is that there is relatively less urgency to remind students to engage in positive interactions with people of different backgrounds, given the high level of ethnic harmony in Singapore. A recent survey on racial and religious harmony shows that more than 90% of residents were comfortable with those of other races and religions for public sphere relationships, such as with one’s colleague, boss, employee, or neighbour (Mathews, n.d.). The same survey also reports that around 70% commented that it was good for Singapore to be composed of different races, and that a person’s race does not affect how they interact with that person.

In terms of the codes according to the different types of CCE documents, the CCE primary syllabus ranked the lowest number of codes, at only 11 codes, and speech and press releases ranked the highest at 91 codes. The breakdown of the different types of documents is as follows:

-

For primary syllabus, the highest number of codes is for Dimension 4 and Factor 4 with 4 codes, while the lowest codes is for Dimension 1 and Factor 1, with zero codes.

-

For secondary syllabus, the highest number of codes is for Factor 4 with 19 codes, while the lowest code is for Factor 1, with zero codes.

-

For media, speeches and press releases, the highest number of codes is for Factor 4 with 35 codes, while the lowest codes is for the Factor 1, with zero codes.

-

For CCE at primary schools, the highest number of codes is for Factor 4 with 13 codes, while the lowest codes is for Factor 1, with zero codes.

-

For CCE at secondary schools, the highest number of codes is for Factor 4 with 10 codes, while the lowest codes is for Factor 1, with zero codes.

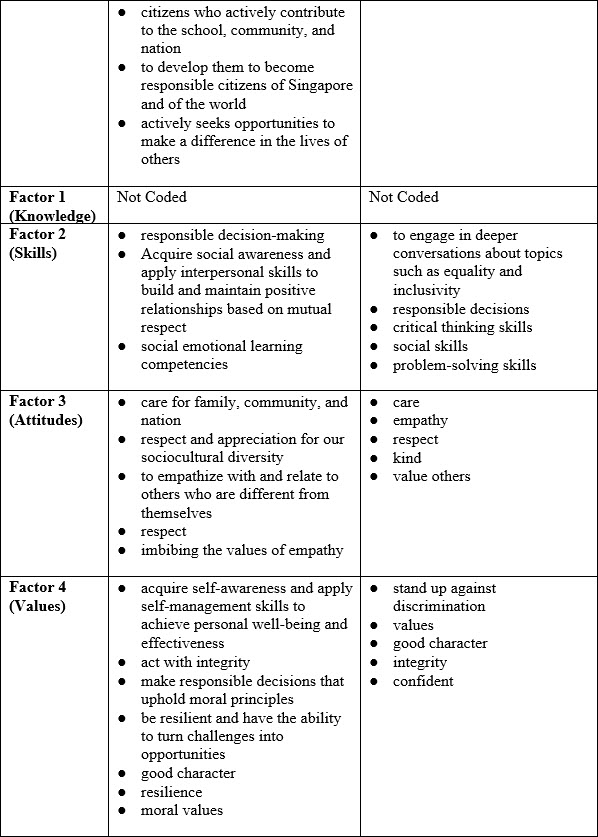

With regards to the extracts from the CCE documents, the samples of the codes and coding themes are tabulated in Table 3 below:

Table 3

The Extracts of Codes and Themes from the Documents Related to CCE

The highest in number from Table 3 are Dimension 4 and Factor 4. Dimension 4 concerns the capacity and disposition to take constructive action towards sustainable development and collective well-being, and Factor 4 deals with values, valuing human dignity and diversity. Notably, Dimension 2 which pertains to the knowledge of the global world, issues and challenges, is not the highest in number in the CCE programmes in Singapore schools featured here. This does not mean that Dimension 2 is unimportant, as issues related to global competence are also taught in other school subjects and co-curricular activities outside the classroom (MOE, 2020b). Subjects such as Humanities (Social Studies) History, Music, and Art, include content knowledge that provides opportunities for exploration into national identity, contemporary issues, as well as Singapore’s constraints and vulnerabilities. The teaching of English and Mother Tongue Languages also provides opportunities to hone students’ sensitivity towards others and learn communication skills for relationship building (MOE, 2020c).

Discussion

Returning to the research question on how the notion of global competence is positioned and framed in CCE in Singapore, the research findings point to a communitarian orientation that highlights social attachments, shared interests and communal goals. Communitarianism, despite its diverse origins, theories, and traditions, generally subscribes to at least two central beliefs (Taylor, 1994; Walzer, 1983; Watson, 1999). First, communitarians disavow the view that the self is detached from society and independent of all concrete encumbrances of moral or political obligations (Sandel, 1981; Taylor, 1989). In particular, they object to “liberal individualism” that emphasizes abstract and excessive individualism at the expense of the centrality of community for personal identity and moral thinking (Arthur, 1998). Communitarians assert that the self is always constituted through a community that exists in shared social and cultural understandings, traditions, and practices.

This brings us to the second shared belief of communitarians: they stress the pivotal place of the community in the formation and sustenance of the individual’s values, behaviour, and identity (Tan, 2013). In other words, communitarians hold that the community provides the constitutive structure and mental model for its members through socialization and enculturation. Individuals derive and justify their values, perceive their world and conduct their lives in accordance with the interpretive framework provided by the community (Walzer, 1983; MacIntyre, 1988). It follows that individuals are expected to transcend the self to carry out their civic obligations; they should pursue the “common good,” understood as a collective determination of an assemblage of norms and goals for the community (Bang et al., 2000; Watson, 1999).

With reference to the research findings, the CCE documents manifest a communitarian emphasis through their focus on Dimension 4, which is taking actions for collective well-being and sustainable development. As evident in Table 2, students in Singapore are reminded to be committed to a larger purpose beyond themselves, feel a strong sense of duty and responsibility to their fellow citizens, serve and help others succeed, and have a shared sense of mission to take care of their fellow citizens and our country. Undergirding the accent on communitarianism are the values of human dignity and diversity (Factor 4) which is the highest number among the four factors in the CCE documents. The values in the contents extracted from selected press releases and speeches on CCE also reiterate communitarian beliefs, namely standing up against discrimination and cultivating integrity as members of the community.

The communitarian ideology that is propounded in CCE is also evident in other subjects taught in schools in Singapore. If one explores the Humanities syllabus, one would perceive that it includes the following relevant aims: students would understand the rights and responsibilities of citizens and the role of the government in society; understand their identity as Singaporeans, with a regional and global outlook; understand the Singapore perspective on key national, regional and global issues; analyze and negotiate complex issues through evaluating multiple sources with different perspectives; and arrive at well-reasoned, responsible decisions through reflective thought and discernment (MOE, 2023). As concerned citizens, students would have a sense of belonging to the nation, appreciate and be committed to building social cohesion in a diverse society; be motivated to engage in issues of societal concern; and reflect on the ethical considerations and consequences of decision-making. As participative citizens, students are encouraged to partake in collective actions to bring about changes for the common good (MOE, 2018).

Echoing the communitarian focus in the Humanities syllabus is the syllabus of History. It is indicated that one of the aims of the history syllabus is to "equip students with the necessary historical knowledge, skills, values and attitudes to understand the present, to contribute actively and responsibly as local and global citizens" (MOE, 2024, p. 11, italics added). And under the aspects of values in learning history, students are expected to internalize the core values and worldviews connected to history learning when they display perspective-taking and contextualized thinking in their interpretations of events and issues; demonstrate flexible thinking by being amenable to competing views; empathize with people from diverse ethnic, political, socioconomic, and cultural backgrounds; establish bonds with past and present communities, and take steps to contribute to the larger good (MOE, 2024).

Another example is the mother tongue syllabus that includes the goals of instituting within the students “respect people from diverse cultural backgrounds, with different worldviews and perspectives”; develop a sense of moral values, good character and civic responsibility, and understand and discuss the impact of contemporary issues and current affairs, both locally and globally (MOE, 2020b, p. 12, emphasis added).

Implications for the Concept of Global Competence

A key implication from the example of Singapore is the significance of communitarianism as a theoretical foundation of global competence, especially in Asian societies. The communitarian orientation for CCE in Singapore shows that there is insufficient attention paid to collective considerations in OECD’s interpretation of global competence. As noted earlier, OECD’s understanding of global competence leans towards individualism against the backdrop of neoliberalism. A global competent person, from a communitarian standpoint, goes beyond individual autonomy to preserve and advance social interests and commitments.

Communitarianism is more than just collectivism, with the latter referring to prioritizing the group over the individual. On the one hand, communitarianism is aligned with collectivism in opposing the “cult of the individual”: the proposition that the self is prior to and ontologically separate from society and communal obligations. But communitarianism goes a step further than collectivism in embedding the self within the community. Instead of viewing individuals as atomistic beings, communitarians hold that humans obtain their personal and shared identities and moral perspectives through social attachment in a community (Arthur, 2000; Haste, 1996; MacIntyre, 1988). Claiming that human beings are “deeply social, embedded in culture and in social practices,” Haste (1996) wrote, “Morality cannot be understood unless we take full account of the social, cultural and historical context” (p. 51). Importantly, an Asian version of communitarianism is observable not only in Singapore but also in other Asian countries such as South Korea, China, Malaysia, and Indonesia (Cummings et al., 2001; Chua, 1995; Tan, 2012; Tan et al., 2015). Researchers have noted that political and educational leaders in East and Southeast Asia tend to incorporate elements of communitarianism into their governance and public policies (Chua, 2005; Tan & Tan, 2014).

The communitarians’ critique of excessive individualism does not mean that they are antagonistic towards liberalism in general (Fox, 1997; Tan, 2013). On the contrary, communitarians support liberal values such as expanding the individual’s talents and potentials, and requiring the state to protect the rights of individuals to achieve their life goals (Arthur, 1998). But the point is that communitarianism, as signified by its name, places a premium on the role of the community in giving meaning to individuals’ life purposes and aspirations (Bang et al., 2000; Cochran, 1989). To put it simply, the self arises from a community that constitutes, motivates, and influences a person’s self-concept, beliefs, values, dispositions, and behaviour (Sandel, 1981; Seitz, 2003). Far from viewing the self and community as adversarial, communitarians see the two as interdependent and complementary. Lim (2023) gave an example of how a school in Singapore harmonizes individual and collective well-being:

[T]o build a positive class culture, at the beginning of the year, each class establishes a set of values or character strengths that they plan work on for the rest of the year. For instance, a teacher-leader shared the example of how one class chose the character strengths that they wanted to collectively develop and formed the acronym “CHISEL” (Curiosity, Hope, Integrity, Social intelligence, Excellence, Leadership), with the intention of sculpting each other and being moulded by learning from experiences to become better individuals and a more flourishing class community

p. 124, emphasis added

In the above example, the selected character strengths were not determined by the school teacher or leaders, but by the students themselves. Each class is free to discuss and arrive at their preferred character strengths, and are committed to develop these attributes collectively through mutual encouragement and support. The reference in the above quote to “better individuals and a more flourishing class community” embodies the synthesis between self and community in communitarianism.

Relating communitarianism to global citizenship and global competence, a global citizen expands one’s sense of belonging from one’s local community to the international arena. A communitarian version of global competence does not eradicate an individual’s loyalty to one’s ethnic or cultural community. Rather, this approach to global competence starts with one’s rootedness in a local tradition, and extends one’s obligations to people outside one’s original setting (Tan, 2024). As noted by Appiah (1998), “it is because humans live best on a small scale that we should defend not just the state, but the country, the town, the street, the business, the craft, the profession, the family, as communities, as circles among the circles narrower than the human horizon, that are appropriate spheres of human concern” (p. 96, emphasis in the original).

To sum up, a communitarian version of global competence gives attention to the varied social and cultural understandings, traditions and practices that make up different communities. While the “global” dimension of global competence is acknowledged, communitarians insist that an individual’s root in a local community should be equally recognized. After all, the community is the source of the interpretive model and outlook within which individuals construct their moral standards, interpret their world and relate with people around them (Walzer, 1983). It follows that, for the communitarians, individuals as global citizens should fulfill their civic obligations locally and internationally.

The key tenets of communitarianism have engendered a potential tension between the global and local. The tension lies in the call for individuals to be “globally competent” by transcending the local experiences and cultures to respect people from other cultures on the one hand, and for them to remain “locally committed” by furthering the common good and civic responsibilities of one’s country on the other. A related criticism of communitarian grounding of global competence is that it presupposes a grand narrative of the common good, which raises questions on its source and legitimacy. Given that the common good is typically predetermined by the leaders of the community, a concern is its imposition on individuals shows voices are marginalized (Tan, 2023). A central issue therefore is how authorities can—and should—balance individual needs and collective interests. In the case of Singapore, there are attempts to integrate individual and communal needs and perspectives. Choo and Chua (2023) reported from their analysis of CCE that there is evidence of ethical criticism in the CCE syllabuses in Singapore, such as equipping students with the critical disposition to make informed choices, and helping them to deal with the challenges of multicultural engagements. Hence the communitarian presupposition of CCE is complemented by the students’ own formulation and realization of values and visions of the good life.

Conclusion

This paper reports a research study on the scope and scale of global competence education through CCE in Singapore. Through a content analysis of the syllabuses of Character and Citizenship Education (CCE), information from school websites on CCE, and relevant official documents, the results reveal a communitarian focus that underscores social attachments, shared interests, and communal goals. The article has explained how the concept of global competence is framed and positioned as achieving collective well-being and valuing human dignity and diversity. The illustrative case study of Singapore suggests the noteworthiness of communitarian ideas and values for the concept of global competence. From a communitarian viewpoint, a globally competent person is first and foremost one who preserves and advances social commitments and collectivism. A globally competent person, from a communitarian standpoint, is necessarily one who preserves and advances social commitments and collectivism. This paper adds to the existing literature on the diverse formulations of the notion of global competence across cultures.

As for the limitations of this study, the first point is that the adoption of OCED’s global competence as the conceptual framework, although useful for this study, means that the data analysis for this project is circumscribed by the four dimensions outlined in the model. Alternative conceptual frameworks for future research include Hunter’s (2004) definition of global competence as “having an open mind while actively seeking to understand cultural norms and expectations of others, and leveraging this gained knowledge to interact, communicate and work effectively outside one’s environment” (p. 101); and Deardorff’s (2004) interpretation of intercultural competence as “the ability to communicate effectively and appropriately in intercultural situations based on one’s intercultural knowledge, skills and attitudes” (p. 184, both cited in Sakamoto, 2022, p. 217).

In addition, the data did not include the extensive array of teachers’ handbooks, teachers’ workbooks, and did not include observation and recording of actual implementation of the CCE programmes in schools. Methodologically, one could argue that the content of syllabuses, press releases and website documentation of the CCE programmes may not adequately or comprehensively represent all that is taught in the classrooms. In other words, it is possible that individual teachers/instructors/programme coordinators may infuse their lessons with content in ways that are not demonstrated through the syllabus. Another limitation is that among the various elements explored in this study is the information contained in the CCE syllabus, press releases and school websites. However, the documents studied do not include the teaching methodologies, teachers’ workbooks, teaching strategies, and the actual implementation of the syllabus in the Singapore schools. These documents are not included in this content analysis, hence are not amenable to a review, making them out of the scope of this research. Future studies should seek to investigate these documents and how they align with the syllabuses and course objectives and assessments, as well as how they assessed in terms of global competence according to the standards set by OECD.

Finally, researchers should explore this line of research further and seek to replicate the current study by gathering syllabuses from other regions such as the European Union, Asia, Africa, Australia, etc., as well as conduct a comparative study between these various regions in order to find if there are similarities or differences in how global competence is taught and developed in their students.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the University of Hong Kong’s Faculty Research Fund.

Biographical notes

Charlene Tan, PhD, was previously a tenured professor at the University of Hong Kong and prior to that, an associate professor at Nanyang Technological University (Singapore). Currently an honorary professor at Life University, her research interests include education policy and philosophy in Singapore and other Asian societies.

Diwi Binti Abbas was a research assistant at the Faculty of education of the University of Hong Kong. She has taught in a secondary school in Singapore and worked at the National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University

Bibliography

- Appiah, K. A. (1998). Cosmopolitan patriots. In P. Cheah & B. Robbins (Eds.), Cosmopolitics: Thinking and feeling beyond the nation (pp. 91–114). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Arthur, J. (1998). Communitarianism: What are the implications for education? Educational Studies, 24(3), 353–368.

- Arthur, J. (2000). Schools and community: The communitarian agenda in education. London, England: Falmer Press.

- Bailey, L., Ledger, S., Their, M., & Pitts, C. M. P. (2023). Global competence in PISA 2018: Deconstruction of the measure. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 21(3), 367–376.

- Bang, H. P., Box, R . C., Hansen, A. P., & Neufeld, J. J. (2000). The state and the citizen: Communitarianism in the United States and Denmark. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 22(2), 369–390.

- Bengtsson, M. (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open, 2, 8–14.

- Chandir, H., & Gorur, R. (2021). Unsustainable measures? Assessing global competence in PISA 2018. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 29(122), 1–25.

- Choo, S. S., & Chua, D. (2023). From moral adaptation to ethical criticism: Analyzing developments in Singapore’s character education programme. Journal of Moral Education, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2023.2255754

- Chua, B. H. (1995). Communitarian ideology and democracy in Singapore. London: Routledge.

- Chua, B. H. (2005). The cost of membership in ascribed community. In W. Kymlicka & B. G. He, (Eds.) Multiculturalism in Asia (pp. 170–195). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cobb, D., & Couch, D. (2018). Teacher education for an uncertain future: Implications of PISA’s global competence. In D. Heck & A. Ambrosetti (Eds.), Teacher education in and for uncertain times (pp. 35–47). Singapore: Springer.

- Cochran, C. E. (1989). The thin theory of community: The communitarians and their critics. Political Studies, 37(3), 422–435.

- Cummings, W. K., Tatto, M. T., & Hawkins, J. (2001). Values education for dynamic societies: Individualism or collectivism (pp. 267–282). Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong.

- Engel, L. C., Rutkowski, D., & Thompson, G. (2019). Toward an international measure of global competence? A critical look at the PISA 2018 framework. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 17(2), 117–131.

- Fox, R. A. (1997). Confucian and communitarian responses to liberal democracy. The Review of Politics, 59(3), 561–592.

- Grotlüschen, A. (2018). Global competence: Does the new OECD competence domain ignore the global South? Studies in the Education of Adults, 50(2), 185–202.

- Han, S., & Zhu, Y. (2022). (Re)conceptualizing ’global competence’ from the students’ perspective. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2022.2148091

- Haste, H. (1996). Communitarianism and the social construction of morality. Journal of Moral Education, 25(1), 47–55.

- Ho, G. (2021, Jun 16). More S'poreans have no religious affiliation: Population census. The Straits Times. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/more-sporeans-have-no-religious-affiliation-population-census

- Hu, X., & Hu, J. (2021). A classification analysis of the high and low levels of global competence of secondary students: Insights from 25 countries/regions. Sustainability, 13(19), 1–17.

- Idrissi, H., Engel, L., & Pashby, K. (2020). The diversity conflation and action ruse: A critical discourse analysis of the OECD’s framework for global competence. Comparative and International Education, 49(1), 1–18.

- Jiaxin G, Huijuan Z., & Md Hasan, H. (2024). Global competence in higher education: A ten-year systematic literature review. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1–16.

- Kang, J. H., Kim, S. Y., Jang, S., & Koh, A.-R. (2018). Can college students’ global competence be enhanced in the classroom? The impact of cross- and inter-cultural online projects. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 55(6), 683–693.

- Ledger, S., L., Bailey, L., Thier, M., & Pitts, C. (2019). OECD’s approach to measuring global competence: Powerful voices shaping education. Teachers College Record, 121(8), 1–40.

- Lim. E. (2023). Teacher perspectives on positive education: Hwa Chong Institution’s journey. In R. B. King, I. S. Caleon, & A. B. I. Bernardo (Eds.), Positive psychology and positive education in Asia: Understanding and fostering well-being in schools (pp. 117–132). Singapore: Springer.

- MacIntyre, A. (1988). Whose justice? Which rationality? Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Mansilla, V. B., & Jackson, A. W. (2011). Educating for global competence: Preparing our youth to engage the world. https://asiasociety.org/files/book-globalcompetence.pdf

- Mansilla, V. B., & Wilson, D. (2020). What is global competence, and what might it look like in Chinese schools? Journal of Research in International Education, 19(1), 3–22.

- Mathews, M. (n.d.). Indicators of racial and religious harmony: An IPS-OnePeople.sg study. https://lkyspp.nus.edu.sg/docs/default-source/ips/forum_-indicators-of-racial-and-religious_110913_slides1.pdf

- Ministry of Education (MOE). (2018). Emphasis on oriental core values and family values. https://www.moe.gov.sg/news/parliamentary-replies/20180709-emphasis-on-oriental-core-values-and-family-values

- Ministry of Education (MOE). (2020a). Character & Citizenship Education (CCE) syllabus secondary. Singapore: MOE.

- Ministry of Education (MOE). (2020b). Mother tongue languages syllabus secondary. Singapore: MOE.

- Ministry of Education (MOE). (2020c). Shaping character and citizenship education in and out of school. https://www.moe.gov.sg/news/forum-letter-replies/20200725-shaping-character-and-citizenship-education-in-and-out-of-school

- Ministry of Education (MOE). (2021). Character & Citizenship Education (CCE) syllabus primary. Singapore: MOE.

- Ministry of Education (MOE). (2023). Humanities (Social Studies) syllabus. Upper secondary express course, normal (academic) course. Singapore: MOE.

- Ministry of Education (MOE) (2024). History teaching and learning syllabuses. Lower secondary express course, normal (academic) course. Singapore: MOE.

- OECD. (n.d.). PISA 2018 global competence. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/innovation/global-competence

- OECD. (2018). Preparing our youth for an inclusive and sustainable world: The OECD PISA global competence framework. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- PISA. (2020). PISA 2018 volume VI: Are students ready to thrive in an interconnected world? Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Prime Minister’s Office. (2019). Population in brief. https://www.strategygroup.gov.sg/files/media-centre/publications/population-in-brief-2019.pdf

- Robertson, S. L. (2021). Provincialising the OECD-PISA global competences project. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 19(2), 167–182.

- Sakamoto, F. (2022). Global competence in Japan: What do students really need? International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 91, 216–228.

- Sälzer, C., & Roczen, N. (2018). Assessing global competence in PISA 2018: Challenges and approaches to capturing a complex construct. International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, 10(1), 5–20.

- Sandel, M. (1981). Liberalism and the limits of justice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Seitz, J. A. (2003). A communitarian approach to creativity. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 10(3), 245–249.

- Sidhu, G., & Kaur, S. (2011). Enhancing global competence in higher education: Malaysia’s strategic initiatives. In S. Marginson, S., Kaur, & E., Sawir (Eds.,) Higher education in the Asia-Pacific (pp. 219–236). Springer, Dordrecht.

- Tan, C. (2012). ‘Our shared values’ in Singapore: A Confucian perspective. Educational Theory, 62(4), 449–463.

- Tan, C. (2013). For group, (f)or self: Communitarianism, Confucianism and values education in Singapore. Curriculum Journal, 24(4), 478–493.

- Tan, C. (2019). Comparing high-performing education systems: Understanding Singapore, Shanghai, and Hong Kong. Oxon: Routledge.

- Tan, C. (2023). Confucian trustworthiness and communitarian education. Ethics and Education,18(2), 167–180.

- Tan, C. (2024). An ethical foundation of global competence and its educational implications. Globalisation Societies and Education, 1–14.

- Tan, C., Chua, C. S. K. & Goh, O. (2015). Rethinking the framework for 21st-century education: Toward a communitarian conception. The Educational Forum, 79(3), 307–320

- Tan, C. & Tan, C. S. (2014). Fostering social cohesion and cultural sustainability through character and citizenship education in Singapore. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 8(4), 191–206.

- Taylor, C. (1989). Sources of the self: The making of modern identity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Taylor, C. (1994). The politics of recognition. In A. Gutmann (Ed.), Multiculturalism (pp. 25–76). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Tsang, K. K., To, H. K., & Chan, R. K. H. (2020). Nurturing the global competence of high school students in Shenzhen: The impact of school-based global learning education, knowledge, and family income. KEDI Journal of Educational Policy, 17(2), 199–21.

- UNESCO. (2015). Global citizenship education. Topics and learning objectives. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- UNESCO. (2019). What is education for sustainable development? https://en.unesco.org/themes/education-sustainable-development/what-is-esd

- United Nations. (n.d.). Universal declaration of human rights. https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/

- Walzer, M. (1983). Spheres of justice. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Watson, B. C. S. (1999). Liberal communitarianism as political theory. Perspectives on Political Science, 28(4), 211–217.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

OECD’s Dimensions and Factors Extracted from Documents Related to CCE

Table 2

The Highest and Lowest Coded Dimensions and Factors in Documents Related to CCE

Table 3

The Extracts of Codes and Themes from the Documents Related to CCE