Résumés

Abstract

Occupational therapists who contribute to fieldwork education are exposed to ethical issues when supervising trainees. Both the ethical issues and the solutions to address these ethical issues are undocumented in the literature. A qualitative study was conducted to document these issues and their solutions. Twenty-three occupational therapists with supervising experience participated in this study. All the participants reported experiencing ethical issues while supervising trainees. This article aims to present the solutions proposed by the participants in order to address the ethical issues of fieldwork education. Intrinsic solutions are linked to supervisors’ ethical, pedagogical or occupational therapy competences. The extrinsic solutions deal with the appropriate measures which can and should be implemented so as to better support the supervisors’ work and better recognize the important contribution of occupational therapists who train the next generation of occupational therapists in clinical settings. This study is likely to have implications on clinical practice, teaching, research and governance.

Keywords:

- fieldwork education,

- supervision,

- solution,

- ethical issue,

- occupational therapy

Résumé

Les ergothérapeutes qui contribuent à la formation clinique sont appelés à vivre des enjeux éthiques lorsqu’ils supervisent des stagiaires. Ces enjeux éthiques sont peu documentés dans les écrits et il en est de même des moyens mis de l’avant par les superviseurs pour les solutionner. Une recherche qualitative a été menée pour documenter ces enjeux et leurs solutions auprès d’ergothérapeutes du Québec-Canada. Vingt-trois ergothérapeutes ayant de l’expérience comme superviseurs ont participé à la recherche. Tous vivent des enjeux éthiques lorsqu’ils supervisent des stagiaires. Cet article présent les résultats relatifs aux moyens qu’ils utilisent ou envisagent pour résoudre les enjeux éthiques de la formation clinique. Ces solutions sont de nature intrinsèque ou extrinsèque. Les solutions intrinsèques sont liées aux compétences des superviseurs aux plans éthique, pédagogique ou ergothérapique. Les solutions extrinsèques sont liées aux mesures de soutien pouvant et devant être mises en place pour mieux soutenir les superviseurs et mieux reconnaître l’importe contribution des ergothérapeutes qui forment la relève ergothérapique dans les milieux cliniques. Cette recherche est susceptible d’avoir des retombées pour la clinique, l’enseignement, la recherche et la gouvernance.

Mots-clés :

- formation clinique,

- supervision,

- solution,

- enjeu éthique,

- ergothérapie

Corps de l’article

Introduction

Traineeships are an integral part of an occupational therapy student’s education. Regardless of their country of origin, occupational therapy students must complete and pass a minimum of 1,000 hours of field training in order to obtain the diploma leading to the practice of the profession (1). Although fieldwork education is a prerequisite for occupational therapy, not all occupational therapists contribute to the preparation of future occupational therapists for a variety of reasons (2). On this subject, a plethora of writings has been published about insufficient fieldwork placements in the profession (3-11). However, although there is a great deal of literature about fieldworkeducation (12), little attention has been paid to the ethical issues associated with supervising trainees and, subsequently, the means of addressing these issues in practice. It should be noted that in this article we take an ethical issue to comprise any situation that jeopardizes conformity with at least one value (13). In this sense, a value refers to an ethical ideal that is distinct from a rule (which is imposed and sometimes related to sanctions) or from a principle (which is a statement that allows a value to be applied) (14). This article specifically discusses ways to address the ethical issues raised by fieldwork education in occupational therapy. However, before engaging with the solutions proposed to address these ethical issues, it is important to first address the ethical issues faced by occupational therapists who supervise trainees in clinical settings.

Our team conducted an empirical study to document the ethical issues associated with to fieldwork education[1] through qualitative interviews with occupational therapy supervisors in Quebec (15). Similar to Barton and colleagues (3) and De Witt (15), we found that occupational therapists who contribute to the fieldwork education of the next generation of occupational therapists experience loyalty conflicts. These conflicts are ethical issues because they put professional roles under tension that are ultimately based on different ethical values and that are difficult to reconcile (16). Specifically, many feel divided between their roles as clinicians (loyalty to clients), supervisors (loyalty to trainees), employees (loyalty to their employers) (15), and guardians of the profession (loyalty to the profession). As with Drake and Irurita (17), Ilott (18), James and Musselman (19) and Le Maistre et al. (20), we also noticed that supervisors, when having to deal with trainees experiencing difficulties or failing, may themselves experience stress, perhaps even distress. As guardians of the profession, many supervisors do not feel comfortable with failing a student (13). We have also noted, as did Lemay (21), that the role of trainees’ supervisor may be paradoxical. On the one hand, the supervisor must support the trainee’s learning process (thus developing a pedagogical posture based on trust and proximity), while, on the other hand, the supervisor must evaluate the achievement of the objectives of traineeship (thus developing a normative posture based in neutrality and distance from the trainee). This may in turn result in a lack of neutrality or in biases on the part of the supervisor evaluating the trainee’s learning process and competences. We also uncovered other ethical issues such as the difficulty some supervisors may encounter when teaching to their trainees in a work environment dominated by management practices that are oriented toward efficiency and productivity (22), thus leaving out important professional values like the quality of care, the client’s dignity or professional autonomy (13). Another ethical issue has to do with the difficulty for many supervisors to support the development of their trainees’ ethical and cultural competencies due to a lack of knowledge on these topics (13). Traineeship supervisors also noted various injustices in clinical settings. For instance, the support offered to supervisors may vary from one clinical context to another. Equally important is the fact that the responsibility for the fieldwork education is unfairly distributed amongst supervisors; i.e., it is frequently the same occupational therapists who are responsible for training the next generation of occupational therapists (13).

While it is relevant to shed light on these ethical issues, it is also important to document ways to address them, notably because these issues are likely to have negative repercussions for many individuals (e.g., clients, trainees, supervisors, colleagues, care partners) and organizations (e.g., trainee settings, universities, professional orders), if they are poorly resolved or ignored. For example, disregarding these issues may compromise the quality of trainee supervision and consequently the quality of occupational therapy services provided by trainees to clients. It can also cause distress to supervisors whose desire to contribute to fieldwork education may thus decrease, which may then limit the number of traineeship positions available to students. We therefore base our argument on the reasonable assumption that the greater the ability and commitment of the actors and organizations involved in fieldwork education to resolve these ethical issues, the more barriers to traineeships will be removed, the better will be the training provided to occupational therapy students, and the more comfortable, supported and recognized occupational therapists will feel in this essential role in the training of tomorrow’s occupational therapists. This is why our team considers that the ethical issues of fieldwork education must be better known, as well as the means to address them.

Literature review regarding solutions

Our literature review in four databases (Academic Search Complete, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Medline) helped us identify 48 texts dealing with different issues related to fieldwork education in different health disciplines. Reading these texts allowed us to identify various ways to address the ethical issues of fieldwork education. The following provides a summary of these solutions.

To support the development of supervisory competencies required to provide quality fieldwork education for occupational therapists, some authors recommend that supervisors be better trained in pedagogy and teaching supervision, which may be accomplished through continuing education (3,7-10,23-26). According to Richard (27), this education should be mandatory to supervise a trainee. In addition, supervisors should be allowed to gain feedback on their supervision skills (8,28). Some authors also suggest that students be introduced to their supervisor’s role at the beginning of their occupational therapy degree (3,26). Others suggest the pairing up of experienced and novice supervisors, that groups of supervisors be created or that communities of practice dedicated to supervision be established in the workplace (24,26).

Regarding the failures that may sometimes occur at the end of traineeships, some authors believe that universities should better prepare students for their traineeships (9,19,25,28,29). In addition, expectations for trainees must be made clear (30) and they must receive regular feedback from their supervisor on their achievement of the traineeship’s objectives (17). Communication between traineeship settings and universities must be regular and accurate (7,19,28), and traineeship failures must be resolved in collaboration with the fieldwork coordinator at the student’s home university (25). In addition, explicit policies and procedures must be established to manage these cases (31). Moreover, occupational therapists who agree to host students must be trained in pedagogy to ensure quality of their fieldwork education and they must be supported by universities when experiencing difficult situations with trainees (18,19,28,31) because these can be quite demanding (13).

To reduce the paradox of fieldwork education, Le Maistre, Boudreau and Paré (20) recommend that supervisors gradually move from a pedagogical posture based on trust and proximity to a normative posture based on neutrality and distance. These authors also suggest that formative assessments and self-evaluations made by the trainee should be integrated throughout the traineeship. They also believe communication between supervisor and trainee to be fundamental, perhaps even a key feature to the successful conduct of the traineeship. Communication must be continuous, clear and honest.

With respect to issues related to work overload and performance pressure experienced by supervisors, some authors believe that the clinical environment must better acknowledge and support the supervisor’s work, particularly by reducing their workload (24,26,28). In addition, more resources must be allocated to the supervisors (time, training, online forums, etc.) (9). A third party should be responsible for the logistical aspects of hosting trainees (provide an identity card, an office, a key, a telephone, a computer access, etc.) (7,26).

As for the fieldwork placements issue, because not all occupational therapists contribute to this professional duty, several authors believe that the role of traineeship supervisor should be recognized even more, both financially and formally (3,5,7,8,10,11,26,32). One way to formally recognize this role would be to provide continuing education workshops for supervisors or to grant them an official title in addition to their professional one (7,26,32). Some authors also consider that the traditional one-on-one supervision model is not ideal (4,7,8,10,11). These authors believe that other models of supervision should be explored and tested, such as having a supervisor oversee the traineeship of up to two or three trainees at a time, or perhaps to co-supervise.

Finally, to support fairness and impartiality in the evaluation of trainees, supervisors should have access to accurate and clear university documentation in order to facilitate a just assessment of their trainees’ competencies (15,23,32).

These points sum up the solutions discussed in the literature to address the ethical issue of fieldwork education in occupational therapy. Two main findings emerged from our literature review. First, an analysis of these texts (n=48) reveals that only one study was conducted in Quebec, and it dealt with various health professionals outside the field of occupational therapy (26). Second, two types of solutions are documented in the literature: intrinsic solutions, i.e., solutions for which supervisors are responsible, and extrinsic solutions, i.e., solutions that pertain to the environments (micro, meso and macro) in which the supervisors work. Further, similar to Glaser (33), our team noted that micro-environmental solutions (solutions identified by individuals other than supervisors), meso-environmental solutions (solutions emerging from clinical settings) and macro-environmental solutions (solutions provided by universities or other social organizations) are documented in the literature.

The research question guiding our investigation was the following: What are the ethical issues associated with fieldwork education in occupational therapy experienced by Quebec occupational therapist supervisors and how do they propose to solve the ethical issues they encounter? This article presents the results of this study.

Research methods

Study design

An inductive research design was used due to the lack of knowledge currently available on the subject in Quebec (34). To better understand the phenomenon under investigation, a descriptive qualitative inductive research design was chosen (35). More precisely, this research is inspired by Husserl’s (36,37) descriptive and transcendental phenomenology. That said, the purpose of the study here was not to describe the objects of consciousness, but to access the essence of the phenomenon being studied through interviews with the people who were best able to share their perceptions and experiences of the phenomenon (37). Our team has used this research design successfully in other studies aimed at documenting and assessing the ethical issues arising in the context of occupational therapy (39-41). This design is also widely used in the field of rehabilitation (34,35,38,42).

Participants

In order to gain the fullest possible insights, we sought out people already familiar and experienced with the topic of our research (34). We thus chose occupational therapists who had supervised at least one trainee. No exclusion criteria were used. We hoped to obtain a large and diverse pool of participants, in terms of gender, professional experience, pedagogy and ethics training, clinical setting, areas of practice (physical, mental, cognitive, social, public health), clientele (child, adolescent, adult or senior) and roles (clinician, fieldwork coordinator, lecturer, teacher, etc.). We also wanted to gain insights from occupational therapists working all over the province.

Recruitment

The Ordre des ergothérapeutes du Québec (professional regulatory college for occupational therapists in Quebec) sent an email invitation to occupational therapists who had given their permission to be solicited to take part in various studies. Potential participants were invited to contact the research assistant responsible for data collection. To ensure data saturation, four additional occupational therapists known to the team were approached by a research assistant to participate in the study. Because the data collection tools were written in French, we sought only French-speaking and French-reading occupational therapists.

Data collection

Once they had signed the consent form, participants were invited to fill out a socio-demographic questionnaire and to participate in a 45 to 90 minute telephone interview with a research assistant. Telephone interviews were favoured over Skype or other communication applications to reduce the bias of social desirability. Moreover, to avoid group contamination, individual interviews were favoured over focused groups. The interview schedule was based on the four types of ethical issues proposed by Swisher and colleagues (13). Having conducted several studies on the ethical issues in occupational therapy, the use of this typology has been found to allow occupational therapists to deepen their reflections and perceptions of the ethical issues raised by their practice without compromising the inductive nature of the research (43-49). Thus, after discussing the ethical dilemmas, temptations, silences and distresses of supervising trainees, participants were asked to discuss the means they use or could use to address these issues. The interview guide was sent to prospective participants by email. We believed that since it may sometimes be difficult to discuss ethics, giving participants the chance to read the interview guide before the actual interview could enable richer, more focused and clearer responses. The majority of participants had in fact taken the time to reflect on the ethical issues associated with fieldwork education and the means they employ to solve them. The interviews were digitally recorded in order to facilitate their complete transcription.

Data analysis

As suggested by Giorgi (39), who proposed five steps for applying the fundamental principles of Husserlian phenomenological reduction (36,37) in qualitative research, the following steps were carried out: 1) complete transcription of the collected narrative; 2) repeated reading of these narratives by each of the analysts; 3) progressive creation of themes via data extraction tables during workshops with all analysts; 4) formulation and organization of themes in the discipline’s language; 5) synthesis of the results. This method of analyzing narratives has shown how occupational therapists attribute meaning to the means they use to solve the ethical issues of fieldwork education (40). No data analysis software was used; the analysts manually coded the data. Throughout their analyses and discussions, the analysts (i.e., the first three authors of the article) were committed to presenting the richness of the narratives collected. Several participants had the opportunity to provide feedback on the interpretation of the data following the presentation of the results at a workshop and during a scientific symposium. In all cases, this feedback validated the analysts’ interpretations.

Ethical considerations

An ethics certificate from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières (UQTR) was obtained to conduct this study. As noted earlier, all participants signed an informed consent form in order to participate. By way of appreciation, each participant was given a $25 gift. Some participants refused compensation on the grounds that research funds are difficult to obtain, so these funds should support students and not them. Throughout the study, several considerations were at the heart of the team’s research, including respect and fidelity to participants’ comments, confidentiality, and recognition of their participation to name but a few examples.

Results

Participants in the study

As indicated in Table 1, twenty-three (n=23) occupational therapists in Quebec participated in the study. Among these, twenty (n=20) were women and three (n=3) were men. Participants ranged in age from 25 to 56, with an average age of 37. Concerning their experience, on average the participants had been occupational therapists for fourteen (14) years, with the least experienced participant having been an occupational therapist for three (3) years while the most experienced participant had thirty-five (35) years of experience. All participants had experience in supervising trainees. The participants shared an average of 8 years of experience in fieldwork education. The least experienced supervisor cumulated two (2) years of supervising experience while the most experienced had 23 years of experience in supervision.

Table 1

Description of participants

Nine participants had supervised between 1 and 5 trainees, eight participants had supervised between 6 and 10 trainees and six participants had supervised 20 or more trainees. The majority (n=15) had higher education degrees (professional or research master’s degree, graduate certificate, etc.) while the minority (n=8) had a bachelor’s degree in occupational therapy (university undergraduate degree). Most (n=20) had limited training in pedagogy (a few hours or days of training). Three participants had taken university courses in pedagogy. The majority (n=13) had little training in ethics (no training or some training ranging from a few hours to days). Nine participants had completed at least one university course in ethics.

Most participants were clinicians (n=17) while three were fieldwork coordinators, and two were professors. Eight worked with adults, five with seniors, five with children and four with both adults and seniors. The majority (n=13) worked in physical health, three in mental health, three in cognitive health, three in various clientele groups and one in public health. Participants practiced the profession in eight of Quebec’s seventeen administrative regions, including Montréal, Mauricie, Laurentides, Lanaudière, Estrie, Centre-du-Québec, Saguenay and Montérégie.

Addressing the ethical issues of fieldwork education

Two types of solutions were discussed by participants, namely: 1) intrinsic solutions, i.e., those for which supervisors are responsible, and 2) extrinsic solutions, i.e., those that relate to the environments in which supervisors work, namely other people (colleagues, trainees interns or superiors), clinical settings and organizations outside clinical settings (universities, the health system and professional associations or colleges). When discussing intrinsic solutions, participants referred to supervisors’ professional competencies. When discussing extrinsic solutions, participants discussed the measures that have been or will be put in place to help supervisors. It should be noted that participants did not explicitly use these categories (intrinsic and extrinsic), which are derived from our own analyses.

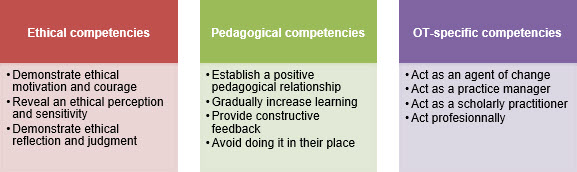

Intrinsic solutions or three professional competencies

Figure 1 illustrates the intrinsic solutions, divided into three competencies, which occupational therapists accomplish. These competencies can help clinical supervisors to address the ethical issues of fieldwork education: ethical, pedagogical and occupational therapy-specific competencies. The following paragraphs explain and illustrate these competencies with excerpts from the interview transcripts.

Figure 1

Modes of public value elicitation

Ethical competences

Most participants discussed the actions they carried out to resolve the ethical issues of traineeship supervision, which are linked to ethical competencies. Although not all participants used ethical vocabulary to name these competencies, the actions they reported revealed their ethical competences. For instance, regarding the shortage of clinical placements, one participant demonstrated ethical motivation. He believed that it was his duty to contribute to the education of the next generation of occupational therapists. He expressed himself as follows: “I consider that I have a clinical mission, an academic mission and a research mission” (participant 14). Invested with his university’s mission, he was committed to doing his part in welcoming trainees. For him, this was an ethical responsibility and part of his professional duty.

When confronted with trainees in a situation of failure, some participants stated that ethical courage must be shown, i.e., one should not run away from the fact that failing a student does not deserve to pass his or her traineeship. Although this decision is very difficult, it takes courage not allow incompetent students to gain access to the profession. “Situations of failure are often where ethical situations can emerge.… Do we want this student to practice in a couple of months, if we give the student a passing grade, when we have serious doubts as to his/her competences?” (participant 14). In these situations, supervisors mention the importance of collecting and documenting the facts detailing their decisions. To facilitate the decision-making process, one participant explained using the following thought process: “Would I want this trainee to treat one of my relatives? … If the student performed an intervention on one of my relatives, how would I feel? This helps me make a decision” (participant 19).

To identify the ethical issues related to fieldwork education, supervisors considered it important to recognize the emotions they experienced, to distinguish the values involved, and to take the time to assess verbally what they experienced with their trainees. These supervisors showed ethical perception, that is, they could identify the issue. Identifying and self-actualising with regard to their own values permitted them to express the ethical issues they experienced.

I feel it is important to understand yourself and to know what your values are. When we are at ease or when we feel there is an ethical conflict, I ask myself: “What value is being violated right now? Mine, or theirs?... What is happening?”… [I] take a moment to stop, then I discuss this with the student: “There, this happened. I feel uncomfortable or sad or I feel that the patient has not been respected. Not enough thought has been given to the professional autonomy of this or that other person”

participant 18

To ensure impartiality and fairness in the evaluation of trainees, participants considered it important to manage their axiological or cognitive biases, which are based on information provided to them by various people regarding their trainees. In becoming aware of their biases (which can be either positive or negative) participants demonstrated ethical perception towards their trainees and in managing their biases.

Supervisors demonstrated their ethical sensibilityviz. their ability to intuitively feel the presence of an ethical issue. For example, supervisors felt uncomfortable when circumstances were such that trainees were imposed on the clientele or made it seem that they gave their consent to be seen by trainees from the outset. For these supervisors, the free and informed consent of the clientele accompanied by trainees is primordial. Other supervisors paid particular attention to trainee confidentiality. For them, the importance of respecting confidentiality is relevant for both trainees and the clientele. With regard to neoliberal management methods, one participant considered that an ethical lens was essential to make administrators and managers aware of the values that should govern care and services for clients.

What could be helpful is if managers had appropriate training or sensitivity to this. Often, in terms of cuts, mergers, service restructuring, and, if in the process of adapting to change, there was this notion, the ethical aspect, if only to name the issue, to allow people to verbalize and all that, I think it would make it a lot less dramatic. I believe that, in this whole process of change, there would really be an advantage in identifying all situations with an ethical eye

participant 14

Several supervisors considered that ethical reflection was important and useful in dealing with ethical issues pertaining to internship supervision. This was the ethical competence most discussed by participants: half referred specifically to this competence, while about one quarter of participants addressed another one (motivation, courage, sensitivity, ethical perception or judgment). To better reflect on the values involved in the ethical issues they uncover, some participants used reflective tools which allow them to further their analyses. “I need to take the time to think about it…I made a kind of conceptual map for myself to try to understand what was going on in the situation. I also referred to ‘tools’” (participant 10). By questioning managerial methods, a participant added the following: “If all [managers and workers] had even basic training in reflective thinking to be able...to analyze the situation [through an ethical eye] and then realize: “Ok, I live in such discomfort, I live such an emotion with relation to such a situation: What action could I perform? What action could I not do again?”... By applying the principles of reflective thinking, I think it would be very useful in practice” (participant 4). Some participants used a decision-making scale to support their decisions, which involved considering different scenarios and identifying the consequences of the options available to them. Others used models to support ethical deliberation, such as the ten steps of ethical reflection developed by Drolet (42,51) or the “I-you-he/she” model used by Sylvie Boulianne (52), a physician who provides training to supervisors. “(The I-you-he/she] addresses clinical supervision in three steps to determine whether the problem stems from the patient or form the organization. This way of approaching ethics with the student is very imaginative, very concrete. I use this model with students when there is an ethical situation” (participant 14). Other participants prioritized the values at stake in the situation. “Do I prioritize the safety of clients or students,...the [trainee’s] need to develop in the action or the clientele’s need?...The most important thing is the vulnerable client. The student is in training, I will get back to her later if she feels hurt.... The clientele is vulnerable, it is necessary to protect them” (participant 19).

When participants think from an ethical perspective, they show ethical judgment. In other words, when supervisors take a moment to examine and develop their ethical decisions through an “ethical eye”, they exercise their ethical judgment.

Pedagogical competencies

In addition to ethical competencies, clinical supervisors discussed the pedagogical competencies they use daily to solve the ethical issues of fieldwork education. More specifically, the majority of participants (n=15) discussed the importance for supervisors to develop their pedagogical competencies. Not only can these competencies enable the provision of quality fieldwork education to trainees, it can also facilitate the resolution of ethical issues that supervisors may encounter. When discussing the pedagogical competencies that supervisors should develop, participants raised the four following themes: 1) building a positive pedagogical relationship, 2) increasing learning, 3) providing constructive feedback, and 4) avoiding doing the tasks for the trainee.

For many supervisors, a positive pedagogical relationship between the supervisor and the trainee facilitates effective learning and helps the trainee to develop relevant competencies. These supervisors believed that it is important to take the time to get to know the trainee and to establish a relationship based on trust with him/her, which makes room for compassion and humanity. “Very often, the first day, the trainee arrives, and he/she has clients. [I take the time] to spend an hour, an hour and a half [with him/her] before beginning with the clients. [I want] just to get to know them…to understand their personality” (participant 16). The supervisor “needs to create a partnership in order to eventually confront trainees facing challenges so as to help him/her progress as a future occupational therapist” (participant 19). Without this alliance, learning is impossible. Most supervisors emphasized the importance of having clear and frequent discussions with their trainees, which may involve scheduling periodic meeting times and frequent feedback concerning their progress in the traineeship.

Once trust has been establish between supervisor and trainee, and both of them agree on the “traineeship contract” (participant 7), supervisors explained that it was necessary to advance the learning and offer constructive feedback to the trainee, all in order to support the development of their competences. As one participant summarized, it always comes down to “gradually raising expectations [and] bringing out one’s strengths” (participant 13). It is important to “bring out the positive”. These supervisors believed that it is important to confront their trainees with “just right challenge” type of situation so as to focus on their strengths while keeping in mind that the point of the traineeship is for the trainee to learn.

When I have a student in difficulty, it is more about sitting down with him/her in order to properly identify the aspects that are problematic, the skills I want him/her to work on, and then to develop an action plan with objectives upon which to work. In doing so, it is a question of increasing the difficulty of the task and finding the best methods of supervision to support it, to accompany it.... [It is relevant] to also return to the evaluation criteria for evaluating the traineeship, and then sometimes to discuss with the fieldwork coordinator [to check] whether there are other elements to consider

participant 7

Moreover, supervisors insisted on allowing trainees to experiment and to test their knowledge, even if this might lead to mistakes. To put it differently, participants articulated the need to avoid doing it for the trainee. In a traineeship, the point is to offer trainees learning opportunities, which implies letting them experience various interventions for themselves. As one participant noted, although it is sometimes tempting to do things for trainees, “I let them experiment, do [things] their way” (participant 18). Supervisors insisted that trainees had a “right to make mistakes” (participant 23) because they are learning. It is through their experimentation that they can learn, train and grow as occupational therapists. Of course, that does not mean letting anything go. “A mistake for me is okay. We are here to [support their] learning....I will make corrections.... [On the other hand], if the error continues and continues,...it will be reflected in my comments or my rating when I do the assessment” (participant 6). In sum, although it may sometimes be tempting to perform some interventions for trainees, supervisors believed that it was more pedagogically beneficial for the trainees to let them do things in their own way, even if it is not perfect, as long as no professional misconduct is involved.

Occupational therapy-specific competencies

In addition to ethical and pedagogical competencies, some participants (n=6) discussed competencies related to roles in occupational therapy that can help to solve the ethical issues associated with fieldwork education. When they discussed such roles, supervisors proposed four related competencies, namely: a) the roles of the agent of change, b) the practice manager, c) the scholar-practitioner, and d) the professional. “We need to get the systems moving” (participant 22). To do this, supervisors must be an agent of change, which implies, “conveying messages to [decision makers] and using your influences....You must denounce and be in solution mode. Then, the solution, often, is found in several ways....Take everyone’s perspective and then find win-win solutions. To be the engine that connects the people you need to find the solution, that’s often what you need, and then to be visionary....You must have a vision, it helps us. You have a dream before [and you follow it]” (participant 22).

Several supervisors mentioned that supervision was time-consuming in their already busy schedules. Participants noted that they had implemented time management strategies which allowed them to free up their schedule to accommodate trainees. In this sense, they appeared to possess qualities related to the role of practice manager. Other supervisors updated their competencies pertaining to their role as a scholar-practitioner when training trainees. “I will read articles related to traineeship in order to develop my supervisory skills” (participant 7). Concerning an ethical issue that she had experienced with a trainee, one participant stated that she “looked for articles, documents that could help me to support myself, to make a more objective decision, in a situation where I was uncomfortable” (participant 10). As another participant summarised, “supervisors must equip themselves to deal with ethics” (participant 14). With respect to training he had received, one participant stated that “if I had not had this training, I would feel very helpless to discuss this subject [ethics] with the trainees” (participant 14). Finally, since ethics is a competency that falls within the role of a professional, several supervisors noted that accepting trainees requires a supervisor to have already developed their own professionalism.

The ethical, pedagogical and occupational therapy competencies that we have outlined so fare can help supervisors to address the ethical issues associated with fieldwork education. Although these competencies are useful and necessary, they are often insufficient. Since the ethical issues that supervisors face have systemic dimensions, additional external resources are often required to address these issues. Building on the intrinsic solutions that presented above, we now turn to extrinsic solutions, viz. solutions that pertain to the work environments in which supervisors operate.

Extrinsic solutions or three levels of supporting measures

Almost all participants (n=22) considered that diverse supporting measures facilitated the resolution of ethical issues emerging in supervising trainees or should be available to help supervisors to address these issues in a beneficial way. At the same time, these measures reduce the barriers to supervising trainees and the distress sometimes experienced by some supervisors. As Figure 3 illustrates, the extrinsic solutions discussed by the participants are macro-environmental, meso-environmental and micro-environmental in nature. Again, these categories were not specifically mentioned by participants, but they emerged from our analyses of the data.

Figure 2

Environmental supporting measures for clinical traineeship supervision in occupational therapy

Macro-environmental support measures

Most participants (n=20) considered that the universities from which the trainees come should play a crucial role in the resolution of ethical issues emerging in the supervision of trainees. Specifically, in acting as a go-to-person, the fieldwork coordinator is essential in helping supervisors feel more confident when facing certain issues. “The first thing I do when I have a big issue..., I will call the fieldwork coordinator at the university in question and talk to him/her about it. Then often, when I did it, he/she would give me good advice on things to do.” One participant mentioned that “Whether it is the woman at the university or our immediate superior who directs us, who says: ‘this is a good way to do things’, it also helps.... We have very good support from the University” (participant 3).

It is not often that university programs will be involved in evaluating trainees who are in difficulty. Supervisors considered that sharing this responsibility with universities would be an interesting way both to ensure a fair evaluation of the trainee and to avoid supervisors having to decide on their own whether to fail a student. “I would be of the opinion that the university should be able to participate in the clinical assessment. It’s done in other professions. I think it would triangulate the information a little bit: we would have [the perceptions] of the student, the university and the supervisor, who each have their own vision of evaluation. I think it could eliminate student and supervisor biases, and then objectify the assessment of student learning” (participant 18). Regarding a very acute failing situation, one participant shared the following reflection:

Was it really up to me to judge her future? Because everything has been a little bit on my back.... She flunked her traineeship and they [the university] immediately terminated her curriculum. After that, I got calls from this student for various reasons. She wanted me to take her back, to show me that she was capable. I find that as a clinician, having all that pressure on your shoulders: deciding a student’s future, I think it’s a lot.... I would have thought that the university should have taken a role in this and should have taken on that role, that of the decision.... I referred to them, they helped me to make my judgment, but after that, I would have thought they would have taken over, but they didn’t.... In terms of informing the student, I would have thought that it would have been more their responsibility, but it was the opposite

participant 5

The training offered to supervisors by some university programs (in-class or online) was appreciated, since it helped them develop their supervising competences. “The [university’s] training program gives us some ideas [to solve supervision issues]” (participant 1). “Training in relation to traineeships (supervising several students at once, communication [with the trainee]), it helps to guide us.... So later on, we don’t need to call them to ask questions. It eliminates the problems at the root, after all” (participant 3). Another participant added the following: “There are online training courses that exist with different modules..., but it would be fun to have more.... I would like to have small video clips with role-playing games on different themes, if only one on the evaluation, the announcement of a failure, etc.” (participant 21).

Some participants mentioned that ethical training specifically applied to supervision would be pertinent. “We still have a good follow-up from the university that gives us training, but the ethical side as such was not a subject that was really addressed. I wanted to be a little better equipped in these things. As part of my continuing education, I decided to go and do a microprogram in which there was an ethics course. It guided me a little” (participant 16). “Having a problem-solving method when you felt you were facing an ethical problem, but the lack of a formal time to establish yourself in an approach like this prevents me from updating it” (participant 18). To address the lack of ethics training, some participants suggested that the results of this study be used to train supervisors. “Having a training after the research could be interesting” (participant 7). This could “help [the supervisors] recognize (ethical issues) and know how to think about them” (participant 19). Another participant felt that Quebec’s College of Occupational Therapists could provide this type of training. “This may be lacking: training in ethical deliberation. I don’t see that in the courses offered by the College, but it could be very interesting to offer training in ethical deliberation and to gather several common dilemmas, challenges, and then just experiment with occupational therapists. Do a continuous training where everyone discusses their situations and learns to deliberate. That way, they could teach it to students. That would be very interesting!” (participant 20).

Still in connection with Quebec’s College of Occupational Therapists, one participant mentioned that it would be useful to have a section in the OT Express, the College’s journal, addressing the ethical issues associated with fieldwork education and solutions to address them.

We could have a section in the OT Express (Ergothérapie Express) so that people [can see that these issues are experienced by others and thus] remove the fear [of supervising trainees]. “Ah, I’ve been through this too.... I’m not alone in my corner that has experienced this.” So, a kind of chronicle on the ethical experiences encountered on a daily basis by occupational therapists with a commentary from an expert on options, how it could be managed. It could also give strength to the profession because I think it’s really something that when you discuss it together, you see the light

participant 20

Participants also noted that constituting a group of supervisors between different clinical settings (in person or online), that is, a forum between supervisors all over the province, would be an efficient way of sharing experiences. It could also be relevant to solving ethical issues associated with fieldwork education. “A kind of group, a community of practice for internship supervisors, with a training component regarding specific issues..., to support the development of their skills. How can I give feedback to a trainee facing difficulties or to one who lacks self-criticism?...How to announce or avoid a failed internship?” (participant 22).

Meso-environmental support measures

Most participants (n=19) also wanted more support from their practice settings when they supervised trainees. Occupational therapists believed that time should be made available for clinical traineeship supervision, including meetings between supervisors at the mid-point of the internship. “If we had more time to sit down with students in difficulty, it would be better” (participant 5). “We have internship supervisor meetings at the mid-point of the internship.... It is something that helps me, that helps us to solve ethical issues.... If we have any questions, we can ask them.... When there are more senior occupational therapists, they certainly help us” (participant 2).

Participants also felt that clear policies and procedures should be implemented in order to ensure the free, informed and ongoing consent of clients to be cared for by trainees. “Having certain policies or procedures, certain guidelines on the work we do, it helps us to think when there is an ethical issue at stake.... Consent by clients to be seen by an trainee [must be formalized because]...it may be that the trainee makes mistakes or that it takes more time, even if I am there to provide supervision; so that still partly responds to one of my dilemmas between [supporting] learning and [providing] quality services” (participant 7).

Material resources (locations, furniture, computers, passwords, etc.) must be dedicated to welcoming trainees in clinical settings. Too often, supervisors noted that trainees did not have access to an office with a computer and faced problems obtaining the credentials required to operate efficiently during their traineeship. “I wish I could accommodate more trainees, but I feel that the receptivity of the community is not necessarily there.... Just getting them a desk, it’s complicated. I made the request so that my trainee could access the computer, and then we never received her password” (participant 1).

To be recognized, that is, to be appreciated, was essential for many supervisors. “In any case, I would work on that, recognition. ... There is a way to do this internally within an institution: recognition.... Because monetary recognition, I’m not saying it’s not important, but if...your manager...doesn’t value it already, it starts off on the wrong foot.... A recognition program for internship supervisors, I find it super what they do here at the university” (participant 22).

Micro-environmental support measures

Many supervisors (n=18) sought and obtained support from colleagues to address the ethical issues they faced. In doing so, they had the opportunity to assess their perceptions, analyses and reflections, and to feel supported. “The primary resource is my colleague at work” (participant 12). “I needed support in this situation. I have spoken to my colleagues, not to all my colleagues..., but to my closest ones. I wanted them to support me in this” (participant 2). “Share with colleagues, ask them...if they have experienced similar situations and what they have put in place. You don’t always have to reinvent the wheel.... I think you have to open up to people you trust, then hear yourself think, explain, then hear them.... You can’t be alone with that. That’s when you get bitter” (participant 22).

Some participants co-supervised trainees. They felt more comfortable assessing competencies this way and found the responsibility for fieldwork education less burdensome. Novice supervisors appreciated being paired with more experienced supervisors. “It was during my first year, I co-supervised with a more experienced colleague.... Then, in the second year of practice, I had trainees” (participant 14). Another participant noted: “The first student I had, I co-supervised with a colleague.…. It was a very nice experience” (participant 16). “I liked it when I co-supervised, because it gave us less time constraints.... It was facilitating. I often do co-supervision with another therapist, so when we have questions, we can validate them” (participant 4). Participants also mentioned that seeking and obtaining support from their superiors when experiencing ethical issues with trainees was always appreciated.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to document the means used or considered by Quebec occupational therapy supervisors in order to solve the ethical issues of fieldwork education. In the following section, we compare the results of the study with those documented in the literature. We then specify the strengths and limitations of the research and explain its potential impacts.

Comparison of results with those documented in the literature

In general, the results of the study are consistent with those previously gathered from the literature. In particular, the recognition of the supervisor’s role has been shown to be an important aspect in supporting occupational therapists. Although some elements proposed in the literature were not specifically mentioned by participants in our study – such as offering continuing education units to supervisors, giving them an official title or recognizing this role in their tasks, or even in their statistics (7,26,32) – participants felt that this responsibility was inherent in the practice of the profession and should be better recognized. Clinical settings should draw on the recognition workshops organized by some universities to not only formally recognize the role of supervisor, but also to value those who contribute to fieldwork education. Another way to recognize and value clinical supervision is to free up supervisors who engage in this role, thus educating the next generation of professionals from which clinical settings will benefit in the future. While some participants suggested that this role should be recognized as time-consuming, the literature is more explicit on this subject: it is strongly recommended that the supervisors’ workload be reduced (24,26,28), and that more human resources be allocated to supervisors. This would include having someone responsible for establishing the logistics of welcoming trainees (7,26).

In general, the results of this study are consistent with the literature (9,18,19,24,26,28,31) in suggesting that workplaces must do more to recognize, support and equip supervisors. This role should not be taken for granted. Environmental conditions must be created in clinical settings to enable occupational therapists to contribute to the clinical training of tomorrow’s occupational therapists, without neglecting the quality of the professional services provided to clients. While some participants in our study noted that their clinical settings were favourable environments for supervision, this is not the case for the majority of participants. Occupational therapists who value fieldwork education do so out of conviction, duty or interest (there are several positive benefits to supervising trainees (2)), often in a context of overload and performance pressure. Since supervision is an occupation and, as with any occupation, a person carries it out in an environment that is more or less constraining, more or less enabling, it is important that constraints to supervision (2) be reduced. This would allow for a greater number of occupational therapists to contribute to the fieldwork, while at the same time maintaining their mental health and providing quality occupational therapy services. To this end, study participants reported that they appreciated various supervision models (including co-supervision) discussed in the literature (4,7,8,10,11). They also believed that formal policies and procedures should be implemented in contexts where this is not the case to ensure the free, informed and continuous consent of clients to be seen by trainees. This would avoid relying on assumed clientele consent.

The study participants’ perceptions are also consistent with the literature when they emphasize the importance of supervisors being better trained, particularly in pedagogy, and so able to support the trainee’s learning and development of competencies (3,7-10,19,23-27). Since the role of a supervisor is essentially pedagogical, supervisor training is required to develop knowledge and pedagogical competencies. To some extent, these are different from the occupational therapist’s usual professional competencies. With respect to competencies useful in addressing the ethical issues applied to supervising trainees, study participants brought up two types that have not previously been discussed in the literature. These include ethical competencies and competencies related to the roles of occupational therapists, as defined in the Profile of practice of occupational therapists in Canada (41). Given the very nature of the issues addressed in the literature, namely ethical issues, this absence is surprising, to say the least. However, this dearth may be due to the fact that ethical competencies, in particular the ethical competencies discussed by Swisher and collaborators (13) (i.e., ethical motivation, courage, perception, sensitivity, reflection and judgment), are still not widely known within the profession. In Canada, ethics education in occupational therapy programs and in continuing education is still in its early stages (50), which likely in part explains these results. Ethics being a philosophical discipline that is sometimes difficult to grasp (14,42,51), specific training on the ethical dimensions of clinical supervision would certainly be relevant and useful. The results of our study therefore suggest that it is important for occupational therapists who contribute to fieldwork education to continue the development of three main competencies: ethical, pedagogical and occupational therapy roles.

Another relevant element identified by participants, but which remains absent in the literature, concerns the role that their professional regulatory college could play in addressing these issues. Practical suggestions were made by some participants, including offering training (face-to-face or online) on the subject, addressing these issues and their solutions in the College’s journal and setting up a pan-Quebec web forum for supervisors. The Quebec chapter of the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists (CAOT) could provide similar support measures, as could other professional associations or colleges of occupational therapists around the world. It is up to each of the clinical settings and each association or college to assess the extent to which the participants’ suggestions are relevant.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

A strength of this study is that it provided supervisors in occupational therapy an opportunity to discuss the solutions that they use to address and solve the ethical issues of supervision. The research was carried out by a team with extensive experience in clinical supervision and expertise in applied ethics. With regard to limits, to prevent an occupational therapy student from questioning a former supervisor or a supervisor from being reluctant to confide in a former trainee, some of the interviews were conducted by an interviewer who did not have knowledge of occupational therapy; this may have limited the interviewer’s ability to discuss with participants the specificities of the occupational therapy practice in the context of traineeship. Additionally, given the fact that occupational therapy programs may differ greatly around the world, and the fact that this was a qualitative study with a small number of participants, the results may not be fully transferable to other contexts.

Potential impacts on practice

This study has the potential to benefit clinical practice, teaching, research and governance. With respect to clinical practice, if supervisors are better prepared, occupational therapists may feel more inclined to take on trainees and be in a better position to balance the requirements of supervision with those of clinical practice. As for teaching, the results of this study can be used to develop professional continuing education for supervisors, as was proposed by participants. Concerning further research, it would be useful for professional development courses dealing with ethical issues in supervising trainees to be evaluated to maximize their benefits. As for governance, we invite clinical settings, universities, professional associations and professional regulatory colleges to consider the suggestions made by the occupational therapists who participated in this study.

Conclusion

Although the literature on clinical occupational therapy education is extensive, few studies have documented the ethical issues associated with supervising trainees and how to solve these issues. This article discusses the ethical issues associated with the role of the occupational therapy supervisor and presents the results of a study that documented the means used or considered by occupational therapy supervisors to address these ethical issues. These solutions are intrinsic and extrinsic in nature. The results suggest that occupational therapists who perform their professional duties in training future occupational therapists through fieldwork education must be better recognized. These gaps appear to partly explain the difficulties experienced by university programs in finding sufficient traineeship placements for occupational therapy students. Finally, documenting how students in occupational therapy perceive and address the ethical issues they face during their internships would be essential to further enhance our understanding of the ethical situations and their solutions.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements / Remerciements

The authors would like to thank the occupational therapists who participated in the study. They also thank warmly Tammy Davis and Louis-Pierre Côté for their help in the revision of the English of this article. They are also very grateful to UQTR for the Clinical Research Fund (CRF) which enabled them to conduct this study. Marie-Josée Drolet extends her gratitude to the FRQSC (Quebec Research Funds – Culture and Society) and the Fondation de l’UQTR for their financial support in conducting this study. Additionally, the authors would like to thank the research assistants who collected the data for this research project. Finally, they are indebted to the reviewers of this article, who providing insightful suggestions to improve the text.

Les auteurs tiennent à remercier les ergothérapeutes qui ont participé à l’étude. Ils remercient également chaleureusement Tammy Davis et Louis-Pierre Côté pour leur aide dans la révision de l’anglais de cet article. Ils sont également très reconnaissants à l’UQTR pour le Fonds de recherche clinique (CRF) mis à leur disposition pour mener cette étude. Marie-Josée Drolet exprime sa gratitude au FRQSC (Fonds de recherche du Québec – Culture et Société) et à la Fondation de l’UQTR pour leur soutien financier dans la réalisation de cette étude. De plus, les auteurs tiennent à remercier les assistants de recherche qui ont collecté les données pour ce projet de recherche. Enfin, ils sont redevables aux réviseurs de cet article, qui ont fourni des suggestions pertinentes pour améliorer le texte.

Note

-

[1]

The article on the ethical issues in clinical training documented by our team is published elsewhere (13).

Bibliography

- 1. World Federation of Occupational Therapy (WFOT). Minimum Standards for the Education of Occupational Therapists. 2016. Available from: https://www.mailmens.nl/files/21072349/copyrighted+world+federation+of+occupational+therapists+minimum+standards+for+the+education+of+occupational+therapists+2016a.pdf

- 2. Drolet MJ, Tremblay L. Les barrières et les facilitateurs à la supervision de stagiaires en ergothérapie. Recueil annuel belge francophone d’ergothérapie. 2019;11:31-57.

- 3. Barton R, Corban A, Herrli-Warner L, McClain E, Riehle D, Tinner E. Role strain in occupational therapy fieldwork educators. Work. 2013;44(3):317-28.

- 4. Clampin A. Not the right time to take a student? Think again. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2012;75(10):441.

- 5. Fisher A, Savin-Baden M. Modernizing fieldwork, part I. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2002;65(5):229-36.

- 6. Jung B, Sainsbury S, Grum RM, Wilkins S, Tryssenaar J. Collaborative fieldwork education with student occupational therapists and student occupational therapist assistants. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2002 April:95-103.

- 7. Kirke P, Layton N, Sim J. Informing fieldwork design: Key elements to quality in fieldwork education for undergraduate occupational therapy students. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2007;54:S13-S22.

- 8. Rodger S, Webb G, Devitt L, Gilbert J, Wrightson P, McMeeken J. A clinical education and practice placements in the allied health professions. Journal of Allied Health. 2008;37(1):53-62.

- 9. Ryan K, Beck M, Ungaretta L, Rooney M, Dalomba E, Kahanov L. Pennsylvania occupational therapy fieldwork educator practices and preferences in clinical education. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2018; 6(1):1-15.

- 10. Sloggett K, Kim N, Cameron D. Private practice: Benefits, barriers and strategies of providing fieldwork placements. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2003;70(1):42-50.

- 11. Thomas Y, Dickson D, Broadbridge J, Hopper L, Hawkins R, Edwards A, McBryde C. Benefits and challenges of supervising occupational therapy fieldwork students. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2007;54:S2-S12.

- 12. Roberts ME, Hooper BR, Wood WH, King RM. An international systematic mapping review of fieldwork education in occupational therapy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015;82(2):106-18.

- 13. Drolet MJ, Sauvageau A, Baril N, Gaudet R. Les enjeux éthiques de la formation clinique en ergothérapie. Revue Approches Inductives. 2019;6(1):148-79.

- 14. Drolet MJ. The axiological ontology of occupational therapy: A philosophical analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014;21(1):2-10.

- 15. De Witt PA. Ethics and clinical education. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2016;46(3):4-9.

- 16. Centeno J, Begin L. Les loyautés multiples. Mal-être au travail et enjeux éthiques. Montréal, QC : Nota Bene; 2015.

- 17. Drake V, Irurita V. Clarifying ambiguity in problem fieldwork placements. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 1997;44(2):62-70.

- 18. Ilott I. Ranking the problems of fieldwork supervision reveals a new problem: Failing students. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1996;59(11):525-8.

- 19. James KL, Musselman L. Commonalities in level II fieldwork failure. Occupational Therapy in Health Care. 2005;19(4):67-81.

- 20. Le Maistre C, Boudreau S, Paré A. Mentor or evaluator? Journal of Workplace Learning. 2006;18(6):344-54.

- 21. Lemay V. La supervision et la théorie des sphères de la justice. L’équité coincée entre l’arbre et l’écorce. In: Boutet M, Rousseau N, editors. Les enjeux de la supervision pédagogique des stages. Québec, QC: Presses de l’Université du Québec; 2002:217-31.

- 22. Baillargeon N. La santé malade de l’austérité. Pointe-Calumet, Quebec, Canada : M Éditeur; 2017.

- 23. Estes J. Promoting ethically sound practices in occupational therapy fieldwork education. The American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA). Advisory Opinion for the Ethics Commission. AOTA Official Documents and websites; 2016.

- 24. Hunt K, Kennedy-Jones M. Novice occupational therapist’s perceptions of readiness to undertake fieldwork supervision. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal. 2010;57:394-400.

- 25. Jensen LR, Daniel C. A descriptive study on level II fieldwork supervision in hospital settings. Occupational Therapy in Health Care. 2010;24(4):335-47.

- 26. Leclerc BS, Jacob J, Paquette J. Incitatifs et obstacles à la supervision de stages dans les établissements de santé et de services sociaux de la région de Montréal : une responsabilité partagée. Montréal : Centre de recherche et de partage des savoirs InterActions, CSSS de Bordeaux-Cartierville-Saint-Laurent-CAU; 2014.

- 27. Richard LF. Exploring connections between theory and practice: Stories from fieldwork supervisors. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health. 2008;24(2):154-75.

- 28. Hanson DJ. The perspectives of fieldwork educators regarding level II fieldwork students. Occupational Therapy in Health Care. 2011;25(2-3):164-77.

- 29. Short N, Sample S, Murphy M, Austin B, Glass J. Barriers and solutions to fieldwork education in hand therapy. Journal of Hand Therapy. 2018;31(3):308-14.

- 30. Evenson ME, Roberts M, Kaldenberg J, Barnes MA, Ozalie R. National survey of fieldwork educators: Implications for occupational therapy education. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015;69:1-5.

- 31. Yepes-Rios M, Dudek N, Duboyce R, Curtis J, Allard RJ, Varpio L. The failure to fail underperforming trainees in health professions education. Medical Teacher. 2016;38(11):1092-9.

- 32. Maloney P, Stagnitti K, Schoo A. Barriers and enablers to clinical fieldwork education in rural public private allied health practice. Higher Education Research and Development. 2013;32(3):420-35.

- 33. Glaser JW. Three realms of ethics: Individual institutional societal: Theoretical model and case studies. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield; 1994.

- 34. DePoy E, Gitlin LN. Introduction to research: Understanding and applying multiple strategies. St. Louis: Elsevier Mosby; 2010.

- 35. Corbière M, Larivière N. Méthodes qualitatives, quantitatives et mixtes dans la recherche en sciences humaines, sociales et de la santé. Québec (QC): Presses de l’Université du Québec; 2014.

- 36. Husserl E. The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology. Evanston: Northwestern University Press; 1970.

- 37. Husserl E. The train of thoughts in the lectures. In: Polifroni EC, Welch M, editors. Perspectives on philosophy of science in nursing. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1999:247-62.

- 38. Hunt MR, Carnevale FA. Moral experience: A framework for bioethics research. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2011;37(11):658-62.

- 39. Giorgi A. De la méthode phénoménologique utilisée comme mode de recherche qualitative en sciences humaines: théories, pratique et évaluation. In: Poupart J, Groulx LH, Deslauriers JP, Lapierre A, Mayer R, Pires AP, editors. La recherche qualitative: enjeux épistémologiques et méthodologiques. Boucherville: Gaëtan Morin; 1997:341-64.

- 40. Kinsella EA. Hermeneutics and critical hermeneutics. Forum in Qualitative Social Research. 2006;7(3):19.

- 41. Canadian Association of Occupational Therapy (CAOT). Profile of practice of occupational therapists in Canada. Ottawa, ON: CAOT Publications ACE; 2012.

- 42. Drolet MJ. Acting ethically? A theoretical framework and method designed to overcome ethical tensions in occupational therapy practice. Ottawa: CAOT Publications ACE; 2018.

- 43. Drolet MJ, Goulet M. Les barrières et facilitateurs à l’actualisation des valeurs professionnelles : perceptions d’ergothérapeutes du Québec. Revue ergOThérapie. La revue française de l’ergothérapie. 2018;71:31-50.

- 44. Drolet MJ, Gaudet R, Pinard C. Résoudre les enjeux éthiques de la pratique privée : des ergothérapeutes prennent la parole et usent de créativité. Ethica – Revue interdisciplinaire de recherche en éthique. 2018;22(1):109-41.

- 45. Drolet M-J, Goulet M. Travailler avec des patients autochtones du Canada? Perceptions d’ergothérapeutes du Québec des enjeux éthiques de cette pratique. Recueil annuel belge francophone d’ergothérapie. 2018;10:25-56.

- 46. Drolet M-J, Pinard C, Gaudet R. Les enjeux éthiques de la pratique privée : des ergothérapeutes du Québec lancent un cri d’alarme. Ethica – Revue interdisciplinaire de recherche en éthique. 2017;21(2):173-209.

- 47. Goulet M, Drolet M-J. Les enjeux éthiques de la pratique privée de l’ergothérapie : perceptions d’ergothérapeutes. BioéthiqueOnline. 2017;6(6):1-14.

- 48. Brûlé A-M, Drolet M-J. Exploration des dilemmes éthiques entourant le traitement de la dysphagie à l’enfance et leurs solutions : perception d’intervenants. BioéthiqueOnline. 2017;6(10):1-16.

- 49. Drolet MJ, Maclure J. Les enjeux éthiques de la pratique de l’ergothérapie : perceptions d’ergothérapeutes. Revue Approches inductives. 2016;3(2):166-96.

- 50. Hudon A, Laliberté M, Hunt M, Sonier V, Williams-Jones B, Mazer B, Badro V, Feldman DE. What place for ethics? An overview of ethics teaching in occupational therapy and physiotherapy programs in Canada. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2014;36(9):775-780.

- 51. Drolet MJ. De l’éthique à l’ergothérapie. La philosophie au service de la pratique ergothérapique. Québec (QC): Presses de l’Université du Québec; 2014.

- 52. Boulianne S, Laurin S., Firket P. Aborder l’éthique en supervision clinique : une approche en trois temps, Le Médecin de Famille Canadien-Canadian Family Physician. 2013;59:795-797.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Modes of public value elicitation

Figure 2

Environmental supporting measures for clinical traineeship supervision in occupational therapy

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Description of participants

10.7202/1060048ar

10.7202/1060048ar