Résumés

Abstract

Between archives, as documentary by-products of human activity retained for their long-term value, and the archive, as a concept used outside of the discourse of professional archivists, there is a semantic, conceptual, and theoretical gap. However, this interval is particularly fertile. In this space, non-traditional archives users such as found-footage filmmakers find inspiration. Through the narratives of their work, they show what is not always visible in archives. Their artworks confront us with unarchived and unarchivable dimensions (what is not archived and what cannot be archived), constituent of how archives are created. In studying the archives that are part of found-footage works through an archival usage framework (exploitation), three main cat- egories of the unarchived and the unarchivable emerge: absence, which is linked to gaps, fragments, and incompleteness; the forbidden, which manifests in archives as material traces; and the invisible, which is not shown. These three categories have to do with an unconceived (impensé) state – a state of the archival field reflecting the intentional or unintentional inconceivability or omission of some of its theoretical or practical aspects. By investing in the unconceived – in other words, by studying archival science from practices on the margins – it is possible to renew ideas and discourses inside the discipline.

Résumé

Entre les archives, comme produit documentaire de l’activité humaine conservé en raison de sa valeur sur le long terme, et l’archive comme concept, tel qu’utilisé en dehors de la discipline, il existe un écart sémantique, conceptuel et théorique. Toutefois, cet intervalle est particulièrement fertile. C’est dans cet espace que les utilisateurs non traditionnels des archives, comme les cinéastes de réemploi trouvent leur inspiration. À travers leurs mises en récit, ces derniers montrent ce qui n’est pas visible dans les archives. Leurs oeuvres nous confrontent à une double dimension inarchivée (ce qui n’est pas archivé) et inarchivable (ce qui ne peut pas être archivé), qui est constitutive de ce que sont les archives et de comment elles se construisent. En étudiant les archives qui constituent les oeuvres de réemploi à partir de leur exploitation, trois principales catégories de l’inarchivé et l’inarchivable émergent : l’absence, qui relève de la lacune, du fragment et de l’incomplétude ; l’interdit qui se manifeste dans les archives comme traces matérielles ; et l’invisible qui participe de ce qui ne se montre pas. Ces trois catégories relèvent d’un impensé archivistique, c’est-à-dire d’un état de la discipline qui reflète l’inconcevabilité ou l’omission, volontaire ou non, de certains de ses aspects théoriques ou pratiques. C’est en investissant l’impensé, en étudiant l’archivistique à partir des pratiques en marges, qu’il est possible renouveler les discours sur la discipline.

Corps de l’article

Archives and Found-Footage Cinema

As archivists, we anchor our practices and theories in a field that defines its primary object clearly. Despite variations among different archival traditions and national legal systems, we generally understand archives as the documentary products of human activity, preserved for their long-term value. Completing this definition, archives are associated with the characteristics of authenticity, reliability, integrity, and usability, ensuring they are trusted resources and of value to society.[1]

Yet all understandings of archives do not fit into this framework. Some artists identifying with the archival turn challenge this definition, all while invoking archives or the archive in their creative processes. This is the case with found-footage cinema and video art, a set of practices that reuses pre-existing moving images in new filmic or videographic contexts.[2] Even if the reused material is often called “archive(s)” by artists and the researchers who are studying them, it does not always look “archival” at first glance. Found-footage videos and films often show disparate images whose provenance is unknown; decaying, burned, or broken film stock; unknown faces and bodies that are not clearly visible; pieces of film that are too short to fully grasp; and other grotesque forms of materiality worked by the passage of time that explicitly remind us that we, like these fleeting images, inevitably slowly disappear. All these expressions unfold in poetic, affective, or abject ways in a kind of opposition to everything archives seem to embody; found footage may present images in which we do not always recognize the authenticity, reliability, integrity, and usability traditionally associated with archives.

These images, though fragmentary, deformed monstrosities or ghosts of proper records, have nonetheless a link to archives. Found footage invites us to consider questions of history and memory through images from a certain past – images that have been preserved through time, in different forms, and to which filmmakers are giving value – sharing the concerns of archivists when it comes to archives. So why is there a dissonance? Why is it so difficult for archivists to sometimes see and grasp archives in these images?

The Unarchived and the Unarchivable

To understand this gap, we need to come back to the concept at the heart of our common preoccupations: archives and the archive. The notion of the archive is almost omnipresent in found-footage practices and studies. It can be understood as archives, records, institutions, collections, objects, or traces of the past, but it most often refers to documentary materials that are far from what archivists call “archives” and are typically not even in such archives. The archive finds some of its roots in the reflections generated by L’archéologie du savoir (The Archaeology of Knowledge) by Michel Foucault[3] and Jacques Derrida’s Mal d’archive (Archive Fever).[4] These works offer a theoretical framework for the notion of the archive that exists outside of archival science, as an analytical tool used to think about how history and memory are built.

Since the 1990s, the notion of the archive has become part of the discussion in the humanities. Authors speak about an “archival turn,” which can be understood as a “move from archive-as-source to archive-as-subject”[5] that leads scholars to look beyond and question the boundaries of the archive.[6] Archivist Eric Ketelaar has also identified a second archival turn, “which has led to using the archive(s) as a methodological lens to analyse entities and processes as archive(s). In this perspective, instead of viewing archive(s) ‘as it is,’ something is viewed ‘as archive.’”[7] In art, it is an archival impulse that characterizes this same time period (and even more so the early 2000s);[8] artists draw on and create informal archives, blurring the boundaries between “found and constructed, factual and fictive, public and private.”[9]

The use of the archive in art and the humanities, and more specifically in cinema studies, produces different outcomes.[10] First, the dissemination of the concept brings a polysemy. Its definition, from implicit to non-existent, becomes a large metaphor, which, depending on the context, can be read in relation to time, to history, or to memory. This understanding is then often accompanied by a poetic, sometimes even romantic, view of archives (associated with lost things and ruins) or, at the contrary, by a critical voice that says that the archive is in this case an institution enabling forgetting, secrets, destruction, and taboos, which are difficult or impossible to access. Moreover, these considerations usually do not integrate archival views, which could contribute to analytical thinking on the concept. In an argument asking more broadly to “link the conceptual umbrella we call ‘the archive’ with the more quotidian work of ‘the archives,’” Rick Prelinger notes,

Most writers and artists use the terms [archives and archive] interchangeably without interrogating the difference between them, but the imprecision surrounding “the archives” and “the archive” vexes archivists. An unstable amalgam of the unconscious and quotidian, the “archive” is an undemanding construct. It serves the critical disciplines as they interact with history and memory without necessarily requiring deep engagement.[11]

At the same time, the archive, in the singular, is not often studied in archival science. Archivists have been intrigued by its dissemination in different ways (alternately cautiously, critically, or sometimes more optimistically) since the 1990s, especially. They seem nonetheless to keep the concept at a certain distance, viewing it, as Michelle Caswell notes, as a “hypothetical wonderland.”[12] Archivists often underline the archive’s lack of reference to archives and consequently to a concrete set of practices and thoughts that involves institutions, work, objects, and people:

“The archive” has been deconstructed, decolonized, and queered by scholars in fields as wide-ranging as English, anthropology, cultural studies, and gender and ethnic studies. Yet almost none of the humanistic inquiry at “the archival turn” (even that which addresses “actually existing archives”) has acknowledged the intellectual contribution of archival studies as a field of theory and praxis in its own right, nor is this humanities scholarship in conversation with ideas, debates, and lineages in archival studies. In essence, humanities scholarship is suffering from a failure of interdisciplinarity when it comes to archives.[13]

As Schwartz and Cook already noted in the early 2000s,

While some writers have begun exploring aspects of “the archive” in a metaphorical or philosophical sense, this is almost always done without even a rudimentary understanding of archives as real institutions, as a real profession (the second oldest!), and as a real discipline with its own set of theories, methodologies, and practices.[14]

Based on this analysis, we can state that there is a semantic and conceptual gap between archives and the archive that (1) makes the dialogue between the different fields involved with these notions difficult and (2) inhibits the development of a shared definition of archives and of the benefits that could flow from that dialogue. This divide is neither unfounded nor without interest. It is, for example, a well of inspiration for found-footage artists, who regularly play with the boundaries of both notions in their work. To start a conversation between archives and the archive, we therefore need to address the space between them.

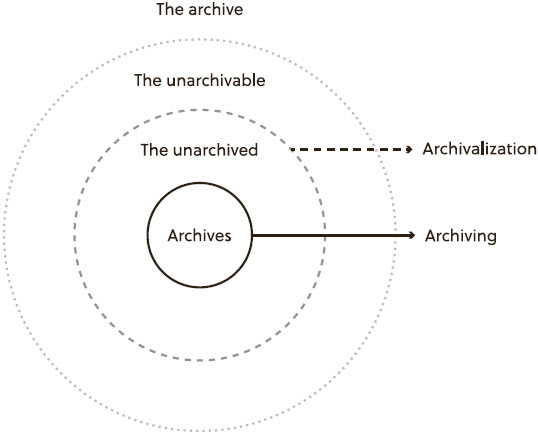

The first step in doing so is to understand what demarcates archives. In archival science, archives are delimited by their definition, which is often inscribed in a legal context. Records are appraised following the mandates, rules, norms, and laws that determine the necessity and possibility of their being archived. Archives are therefore delimited by their definition and the concrete action of archiving. Every record that does not go through this process, does not fit this definition of archives, and is left outside archival institutions represents an unarchived (inarchivé) reality. Additionally, we need to acknowledge what a society considers archivable, or what Eric Ketelaar calls “archivalization.” Archivalization is “the conscious or unconscious choice (determined by social and cultural factors) to consider something worth archiving.”[15] Beyond what is unarchived, there is consequently a dimension that gathers whatever is unarchivable (inarchivable)[16] (see figure 1).

Found-footage works, through their links to archives and the archive, confront us with these two dimensions, constituent of what archives are and how they are created. Between archives, as the documentary product of activities, and the archive, as a concept developed outside of archival science, there is a space in which found-footage artists find inspiration. In this space lies the unarchived, at the threshold of archives, made of everything that has not been archived, and the unarchivable, which represents everything that cannot be archived.

Archival Usage (Exploitation)

To comprehend the unarchived and the unarchivable, let us consider a particular found-footage film and video corpus. To do so, it is helpful to use the archival usage (exploitation) framework developed by Yvon Lemay and Anne Klein[17] as a methodological tool to understand archives in social space. It enables archives to be read from the perspective of their actual and potential uses:

In an archival perspective, it is possible to conceive the “usage” of documents as a transformation of the archive into a new object through the displacement of the meaning, which is the result of an encounter between a user, his/her field of knowledge, his/her culture, his/her universe to a certain extent, and a document, its materiality, its context, its content.[18]

Traditional archival science focuses on archives as objects of the past that belong to the contexts of their creation, and postmodern archival science highlights the moments when they become archives – that is, the products and constructs of archival activities belonging to specific contexts.[19] However, neither of these two points of view considers archives explicitly from the perspective of their usage: what is made with archives and what this tells us about archives and archival science. Postmodern archival science considers that archives are used in various ways and that these uses are part of the archival life of a document, even suggesting that “awareness of the new uses of archives can be of vital support in efforts to convince societies to resolve the digital issue, in order to ensure that these benefits of archives continue to expand.”[20] Nonetheless, few studies analyze the products of archival uses as a starting point for thinking theoretically about archives. Yet the core of our research is neither the original nor the institutional provenance of the archives that found-footage works are made of (often, the material used does not have a known or readily discoverable provenance or even come from any memory institution) but what artists do with archives (or what they call archives).

figure 1

The unarchived (inarchivé) and the unarchivable (inarchivable) dimensions

Archival usage becomes here a method that allows us to understand archival science based on the objects it produces.[21] Indeed, if we observe the results of archival usage, of what is made with archives, this allows us to see archives in a different light; archival uses can underline archival processes and objects in ways that differ from archivists’ usual understanding. For example, artists often use the “negative” characteristics of archives, the same characteristics archivists will tend to avoid or suppress: dust, lack, secrecy, fragility, etc.[22] The usage makes it possible to read found-footage works as archival objects. This process is based on different conditions, through which archives are used: materiality, context, apparatus, and the role of the audience.[23] These four categories are used as an evaluation grid to analyze found-footage works through an archival science lens.

Absence, the Forbidden, and the Invisible

Found-footage works, seen in the light of archival usage, reveal the richness of the unarchived and the unarchivable as concepts and their complexity and permeability as categories. To facilitate the exploration of these concepts, they have been divided into three categories: absence, or that which is not in the archives; the forbidden, or that which cannot be archived; and the invisible, which is present in the archives but cannot be seen. The three categories can be associated with different archival processes such as appraisal, preservation, communication, access, and description. Their study, fed by an archival-science and cinema-studies theoretical and literary corpus (scientific literature, articles, interviews with artists, and film reviews) brings forward several paths for exploring the unarchived and the unarchivable.

Absence

Absence, loss, and lack are constituents of archives and integral parts of the ways in which they are constructed. Absence depends on appraisal, the pivotal moment determining the value of archives and therefore their fate: long-term preservation or elimination. The question of appraisal has long been debated in archival science. Based on the idea that archives represent the testimony of a society at a given moment, archivists reflect on the best way to ensure the preservation of these facts, transactions, and events. Their views diverge, however, when it comes to their role in the matter of selecting archives and the criteria for justifying the selection. At the heart of these debates is often the notion of value and who determines it. The appraisal criteria can be grounded in the needs of the creator, the future uses of archives, or the needs of society in general.[24] In Québec, appraisal is considered to be “one of the most significant and defining functions of contemporary archival practice.”[25] Its theoretical foundation relies on Schellenberg’s value system, to which are added precise functions linked to the utility of archives. Thus, archives’ primary value is associated with the functions of administrative, legal, or financial evidence, and their secondary value fulfills the function of heritage testimony (témoignage patrimonial).[26]

No matter how we approach appraisal, it results in a certain amount of “waste” – that is, the unarchived or the unarchivable, which will never be preserved under the authority of formal institutional archives. Postmodern archival science authors underline what I call several layers of absence in the processes leading to the creation and selection of archives – the societal process of documentation,[27] the archivalization discussed above,[28] and the role of archivists[29] – all acting together as filters that make the preserved documentary heritage but a sliver of the documentary production of a society.[30]

However, the documentary product of this exclusion is not entirely without archival qualities or a link to archives. When appraisal methods “aim to achieve . . . order through the removal of weeds, as part of the process of the creation of a garden of beautiful flowers,”[31] how are those “weeds” viewed when outside of archival institutions? In several interviews and articles, found-footage filmmakers explain where they found the materials they reuse. The films or videos are often bought in second-hand stores or flea markets, given to the filmmakers by people or institutions, or even found in the trash. Filmmakers reuse these “found” films, calling them archives, despite characteristics that seem, at first glance, to be in opposition to the concept of archives. What constitutes the fundamental value of archives has here shifted; what is rejected by memory institutions is cherished by artists. Lucy Reynolds captures this idea by taking Morgan Fisher’s film Standard Gauge (1984) as an example. Standard Gauge shows images of pieces of 35-millimetre film stock, while Fisher talks about the history of cinema and shares personal anecdotes. All the film strips used in the film, and originally destined to end up in the trash, were collected by the artist (who was then working in the film industry). Studying the film, Reynolds brings out this contrast between waste and value:

The filmstrips’ fragile tactility and the care with which Fisher repositions them onscreen, his fingers glimpsed at the edge of the frame, implies that the pieces are treasures of great value. However, Fisher’s filmstrips were retrieved from the apparent arbitrary and uncatalogued archive of the commercial industry, literally discarded scraps from the cutting room floor.[32]

This care of fragile treasures contrasts with their initial status as scraps and recurs in the narratives around found footage and archives. In many examples, artists also address the absence in archives (and the processes that lead to it) through artworks that arose from or showcase exclusion, uselessness, anonymity, lack, transgression, or even illegality. From an archival point of view, these characteristics appear to contrast directly with archival qualities that espouse and value order, transparency, and legality. Artists use as primary material everything that archives have rejected.

In a similar yet paradoxical way, artists also reuse rejected material to extract from it qualities related to history, memory, and temporality. What is considered archival “trash” is for some artists infused with exactly those qualities for which archives are preserved. As filmmaker Craig Baldwin explains,

My project is to liquidate distinctions between official and unofficial history. I think a lot of material from pop culture is archival material: it represents a certain sensibility characteristic of the middle part of the century. I do collect stuff, but my “archive” comes mostly from dumpsters. Refuse is the archive of our times and the resource for what I call “cinema pauvere” [sic] – those people who are impoverished but still intent on making films.[33]

Artists build historical and memorial narratives made from the traces that are not constituent of the official history and memory – in other words, from the traces that are specifically found outside of archival institutions.

This situation has several implications for archival science. First, the characteristics included in many definitions of the value of archives do not consider everything that archives can represent for users. Artists show that archives can be understood beyond a binary system of value. Besides providing evidence for administrative, legal, or financial reasons or having informational or testimonial utility, archives can be read and used for the same characteristics that usually determine their elimination. From lack and exclusion develop abundance and meaningful narratives; using traces outside official archives and giving them an archival status through reuse also creates an occasion to multiply what can be said about and with archives. Furthermore, history and memory can also be found in these specific characteristics, so reused materials are often called “archives” even if they are not preserved in memory institutions. The historical and memorial potential of every trace, through its inscription in time, is here put forward: the authority of archives is no longer unique in the production of discourses about the past. Additionally, reused traces enable this dialogue through those qualities that differentiate them from archives. It is through exclusion, illegality, anonymity, lack, accumulation, or even surprise that artists are addressing a historical or memorial discourse.

To continue with this idea, it is arguable that absence is at the heart of a larger shift in archival spaces. Not only artists find meaning in absence. Alternative archival initiatives such as community archives are indeed emerging with the main motivation of filling the gaps in official archives. They are “motivated and prompted to act by the (real or perceived) failure of mainstream heritage organizations to collect, preserve and . . . accurately represent the stories of all of society.”[34] Absence develops an archival impulse that is present in all of society.

Finally, absence allows us to understand the archive in all its complexities and contradictions. It reminds us, as Derrida noted, that the will to create archives from traces cannot work without a destructive drive, which manifests itself here through selection; it is when we exclude what is deemed useless – what is considered as having no long-term value – that we create archives, which in turn keep a trace of this separation within themselves. Given that found-footage artists are en mal d’archive, as Derrida describes it, they always are “searching for the archive right where it slips away.”[35]

The Forbidden

The forbidden highlights what cannot be archived. It concerns neither what eludes the appraisal processes of archivists nor what is deemed too unimportant to archive, but what is excluded. In the following example, this is because the physical preservation of the forbidden as proper evidence is impossible. Order is considered to be fundamental to maintain archives in the long term: “For archivists, the principal aim is to achieve a condition of positive order in their domain. This they do through the exclusion of what is deemed to be debris, which constantly threatens to undermine the existing order. Dirt and rubbish continually impinge upon archivists’ desire for order and impede their efforts to maintain it.”[36] Manifestations of threats to the physical integrity of archives are the main targets of the exclusion; dust, humidity, and physical deterioration are problems that cannot be tolerated in proper archives. The importance of this archival task is reflected in regulations and codes of ethics, and it appears in the first article of the code of ethics of the International Council on Archives (ICA): “Archivists should protect the integrity of archival material and thus guarantee that it continues to be reliable evidence of the past.”[37]

The duty of long-term preservation comprises two components that depend on each other. There is a material dimension involving a set of rules, practices, standards, and norms to ensure the long-term physical integrity of archives and prevent deterioration as much as possible. But there also is an intellectual aspect to preservation; if archivists secure the material longevity of archives, they need to preserve their qualities as well. Authenticity, reliability, integrity, and usability need to be maintained for archives to be a “trusted resource” and therefore “to be of value to society.”[38] Archives are here considered in a historical, administrative, and legal perspective that sees them mainly as evidence of events and transactions:

Because a record is assumed to reflect an event, its reliability depends on the claim of the record-maker to have been present at that event. Its authenticity subsequently depends on the claim of the record-keeper to have preserved intact and uncorrupted the original memory of that event through the faithful preservation and transmission of its physical manifestation over time.[39]

This aspect of intellectual preservation also encompasses maintaining the links between archival records – that is, the links that characterize them as fonds and that tie them to their creators. As a body of related records, archives maintain connections to their origins that are also meaningful. Through the fonds, archivists preserve the possibilities for archives to be read in light of their creators’ aims and the contexts of the records’ production.

Given this strict archival preservation structure, how can we think about found-footage films and videos that work within an aesthetic of ruins, such as artworks that reuse decomposed and damaged material? Inspiring for some artists, this aesthetic seems, at first glance, contrary to archival preservation practices, which aim to slow down and reduce the effects of time in order to guarantee a certain physical and intellectual longevity for archives.[40] Found-footage films and videos that play with physical or digital decay show what cannot be seen in archives. They are “monstrous” in their representations of archival failure: seemingly ugly glitches, decomposition, and many other types of damage. That said, monstrosity has the advantage of showing what we do not want to see or what we cannot see: it “combines the impossible and the forbidden.”[41] Its role is to transgress, to show, and to warn,[42] and therefore it can be used as an intermediary to study this forbidden aspect of preservation.

Through the prism of monstrosity, found-footage works manifest a materiality that prevails on content and constitutes the narrative. Films such as Decasia: The State of Decay (Bill Morrison, 2002) and Self-Portrait Post-Mortem (Louise Bourque, 2002) are both made of decomposed film stock – Morrison’s coming from different archival institutions[43] and Bourque’s from her own film archive, which she buried in a yard.[44] Alexei Dmitriev’s The Shadow of Your Smile (2015) shows a found pornographic film in which the most explicit scenes are covered in analog static noise, the result of multiple transfers between digital and VHS formats by the filmmaker.[45] In the digital realm, frames melt into one another in Long Live the New Flesh (Nicolas Provost, 2010) and Monster Movie (Takeshi Murata, 2005), provoking glitchy memories. These creations – fading images, deformed faces and places, and untidy pixels – manifest a certain monstrosity while forcing us to stare at decay, in its multiple states, through a different medium.

These films and videos consider archives as material and temporal traces. Not only are they complex objects, implying a materiality, or a medium, that is as significant as its context or its content, but they are also objects marked by visible and concrete sedimentations of time and history. This is as much a changing physical process, resulting from accumulation and decanting, as it is “the latent period between the time when records are accumulated in one place and the time when they are used again for some contingent need.”[46] The time of sedimentation “encompasses all those changes that occur during a certain period of time, corresponding to the preservation time of a specific record, from the moment when it was first produced to the time when it was used again after a period of sedimentation.”[47] This process is unavoidable and meaningful. It reminds us, as André Habib explains, that decay leads us to consider another way to write history, one sensitive to the effects of time, which manifest themselves on the materiality of the medium.[48]

Furthermore, artistic reuse of films and videos escapes a formal reading of archives as evidence or testimony. The artworks can make us think differently about the qualities on which we rely to talk about the trustworthiness of archives; they can be understood outside of that traditional framework. For example, authenticity can be here read in the objects themselves; archives making up the films are authentic because they bear testimony to time passing, in the extremity of decomposition:

Even archival footage, with an old look, gives the illusion of greater authenticity the more it is damaged. Every scratch and waterspot makes it look like it is the authoritative document on the war it must have undoubtedly endured – although the actual conditions which created the war have nothing to do with how much torment the film material suffered.[49]

The static noise strategically hiding some pornographic scenes of Dmitriev’s The Shadow of Your Smile can be understood as a material attempt to reproduce the cinephile authenticity of the VHS era: the repeated rewinding of tapes to rewatch certain parts of the film, leading to their slow degradation. Authenticity is here embodied in the object and resides in the monstruous manifestation of the material’s inherent vice, expressing that “the meaning and value of records extends far beyond their status as reliable and authentic evidence of action as we currently define those terms.”[50]

Finally, this heightened materiality also implies a shift in the way we read history and memory through archives. Here, it unfolds more as an experience made possible through an affective encounter with archives:

The desire for presence is the desire for the archive affect, for an awareness of the passage of time and the partiality of its remains, for an embodied experience of confronting what has been lost, and the mortal human condition. We seek to renew this affect again and again in order not only to know the past but also to feel it.[51]

This emphasizes that the value of testimony and evidence is not always in their content but can sometimes be found in interactions between archival material and its users, which unfold different temporalities and meanings. These specific encounters are even more tangible when archives show signs of decomposition or other traces of time passing. Watching Louise Bourque’s face, in Self-Portrait Post-Mortem, moving slowly through film stock partially digested by decay, for example, creates an affective experience of time which is anchored in a concrete, material reality.

A study of these images, which could be qualified as monstruous and forbidden, shows not so much that found-footage works distort or corrupt the principles underlining the preservation processes but, rather, that they celebrate them, while showing their limits. It is a meeting place between temporalities that enables the making of history and memory in a different framework than the one suggested by traditional archival science.

The Invisible

The invisible can manifest itself in various ways in archives. It can be partly identified in the silences, secrets, and failures that sometimes characterize archival processes[52] or in the invisibility of some archival interventions, making the work of archivists seemingly disappear.[53] But, more broadly, the invisible takes part in what is present but cannot be seen in the archives; it relates to what archives do not show or to what does not appear to the public, to users, or even to archivists.

To reveal the invisibilities in our practices and theories, we need another externality. Where the forbidden notices the monster, the invisible addresses the spectres that allow us to engage in a dialogue with others “who are not present, nor presently living.”[54] These apparitions, existing between the visible and the invisible, outside the linear conception of temporality, enable us to question “the border between the present, the actual or present reality of the present, and everything that can be opposed to it: absence, non-presence, non-effectivity, inactuality, virtuality, or even the simulacrum in general, and so forth.”[55] The spectre as a conceptual metaphor is thus “capable of bringing to light and opening up to analysis hidden, disavowed, and neglected aspects of the social and cultural realm, past and present.”[56]

Studying a corpus of found-footage films and videos through the lens of spectrality brings to light several iterations of invisibility, depending on the context. For example, one form of invisibility can be understood as oversight or forgetting, which comes not so much from the will to make archives invisible but rather from a lack of interest over a certain time. It can be related to the impression that some archives had fallen into oblivion before an archivist or a user brought them back to light. Another form of invisibility can be observed in secrecy – an invisibilization of archives linked to censorship and confidentiality and often associated with historical events, specific political regimes, and other forms of oppression that impose invisibility on archives. In a general way, spectrality is always at play in archival operations:

Beyond the intention and the knowledge of those who hold the apparatuses of archive formation, the spectral will always be at play in them. The space of this play is delimited by mysteries of ignorance or deliberate secreting, by dynamics that are technical or political.[57]

Invisibility can paradoxically appear in the archival processes of accessibility and, more specifically, those processes that make up the functions of dissemination (diffusion) and description.[58] Although these processes are in place to ensure that archives are visible, known, and usable, the delicate work of visibility is also at play here; each step and choice in the matter (the selection of what will be disseminated, the ways of doing so, the philosophy underlining the actions, the dialogue with different users, the tools provided) influences the possibility that archives will be seen. For example, in Québec, the dissemination of archives is mainly organized in a practical way in which information is considered as a resource to manage. Following this approach, archivists focus on the main uses of archives (administrative, scientific, and heritage related) and adapt their tools according to these. This means that dissemination for non-traditional users of archives, such as artists, or for researchers outside this traditional framework, is not always considered or organized. Every archival intervention creates interstices that can generate invisibility, and all our archival measures depend on contexts that themselves hold a certain degree of invisibility.

When Bill Morrison fictionally recreates the Paper Print Collection’s history[59] in The Film of Her (1996), he opens a space for haunting. By associating films from the Paper Print Collection with films he has found elsewhere, his technique plays on the aesthetic and metaphoric qualities of the spectral. The spectrality of archives and images leads viewers to observe the invisibilities in the history of the collection and of the larger history of film preservation, expressed in the treatment of the collection, in the films themselves, or in the succession of technologies. It is also a place for the ghosts of archivists and archival science to express themselves. They point toward the spectrum of (in)visibilities their work is made of: all the gestures, processes, and choices that are not always seen or understood, as well as what they cannot see themselves (bias and the influence of contexts).

Invisibility can also be recognized as an important driver of imagination or imaginaries. When something does not appear but is desired, it can be imagined.[60] In this way, the invisible gaps that constitute archives call for haunting – the possible return of whoever and whatever is not there. The return can unfold poetically as much as politically, when it implies a discourse on justice. Letting ourselves be haunted is also an occasion to

recognize the spectral spaces within every circle of knowledge. And, let us find the courage to offer the spectres hospitality, though they trouble us horribly. This recognizing and this courage draw on gifts usually associated with the shadow realms – imagination, poetry, intuition, emotion, passion, faith.[61]

In The Film of Her, imagination is at play when Morrison invents a reason for the archivist to find the invisible Paper Print Collection and save it. The narrator’s motivation is conveyed through a short clip of an old pornographic film, showing the actress who carries his love for cinema. To this end, Morrison reuses a film, bought in a second-hand shop, which has no tie to the paper prints, leaving part of the story to the imagination and embodying invisibilities and absences. Imaginaries have this double role of inciting dialogues with invisibilities as well as, sometimes, fulfilling them. In this framework, found-footage films and videos open a spectral space that allows ghosts to haunt us.

Following Tom Nesmith’s invitation, based on Derrida, to learn to live “with the ghost . . . how to walk with him, with her, how to let them speak or how to give them back speech,”[62] the spectres become cocreators of archives and their multiple meanings:

Archive traces, of course, never speak for themselves. They are always mediated by readers and apparatuses so that at any moment in time, the archive awaits an indeterminable number of mediations to come. Readings to come. Hosts of ghosts, if you like, opening out of the future, each ghost carrying a potential to disclose, make apparent, meaning and significances within the trace which are awaiting the right reader or reading. Each ghost becoming a co-creator.[63]

These ghosts can therefore be heard when users encounter, read, and use archives. Doing so, they open spectral spaces, allowing spectres to appear and new narratives to be created.

The Archival Unconceived

Studying found-footage works through the archival usage framework allows us to explore the unarchived and unarchivable space between archives and the archive. Usage allows us to look outside archives to observe archival processes in a different light. This exteriority enables characteristics of archives and archival processes – some of which are not always taken into consideration by archivists, even if they are essential to certain users of archives – to appear.

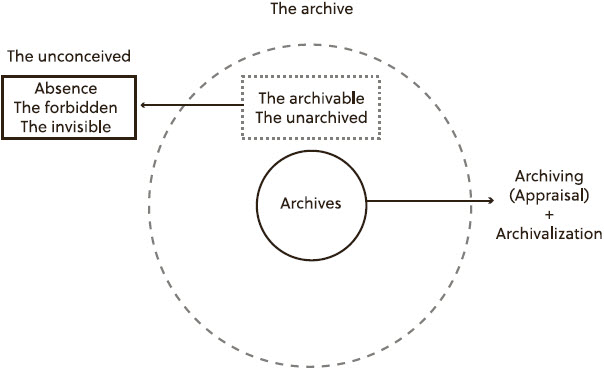

Found-footage films and videos highlight absence, the forbidden, and the invisible, revealing more broadly an archival unconceived (impensé), which can be defined as a dimension of archives consisting of blind spots in our archival thinking that, when noticed, interrogate or challenge the ways archives, archival principles, and certain functions are understood (see figure 2). The unconceived is an unrealized imaginary that gathers objects, concepts, and thoughts that engage archives but are not taken into consideration in specific archival contexts. The notion of an archival unconceived is as important as it is fertile; it allows us, through an exteriority, to think of archives and the archive together and therefore to renew our practices and theories.

figure 2

The unarchived, the unarchivable, and the unconceived

The unconceived can be integrated into our archival thinking by viewing it through the archival usage framework, which, in this case, is essential to our understanding of archives. The concept of archival usage helps us consider the life of archives through their actual and potential uses in social spaces. It is a crucial part of archival work as it brings us to a more global understanding of archives and the multiplicity of narratives they bear. Archival usage acts in some ways as a method of spectral revelation, capable of working the unconceived spaces haunting archives. Moreover, several concepts anchor the unconceived into our thinking: the trace, which leads to what is not gathered under the authority of archives but has the potential to be archival (objects, records, oral culture); the archive as a concept, which allows us to consider all traces in their archival potential, even if they are not archives; and the imaginaries, which are the mechanisms that link the trace (or its absence) to the archive.[64]

The unconceived appears to be a broad and renewable exploration space for archival science. What escapes us? What is unseen? What have we been forgetting? What could be haunting us? Our research points toward several topics that are particularly interesting to analyze through this lens, including the difference between archival science in Québec and that in the rest of Canada and, more specifically, the question of community archives. While some of the issues raised by the unarchived and the unarchivable may have found some answers in the context of Canadian anglophone archival science, this has not always been the case in its Québec counterpart. Since the 1980s, archival science in Québec has been evolving as an independent discipline, with few influences beyond library and information science. While Canadian archivists have been inspired since the 1990s by other fields of research – such as cultural, gender, and feminist studies; de- and post-colonial studies; critical race theory; and postmodern philosophy, to name a few – we can observe that these schools of thought have not always crossed the border into Québec.

As an example, in English Canada, the studies and reflections around community archives stem from this rich interdisciplinary framework. Despite their increasing importance in anglophone archival science, community archives, as a field of research, does not appear as strongly in Québec, even though several initiatives answer to this model.[65] They are a practical and concrete starting point for studying what could constitute the unconceived between the two models of archival science. Community archives can furthermore be analyzed through the dialogue they engage – not only with absence and the invisible but also with archival silences. They highlight several unconceived dimensions of traditional memory institutions. They address the actual preoccupations of archivists, encouraging them to question the role of archives in society, identity, and memory as well as the archival processes that guide them.

More generally, continuous and renewed exchanges between archival theory and practices, as well as between different fields of research, expose the unconceived. It is necessary to enrich our reflections through a conversation between the different actors, reunited around the notion of archive(s), each bringing an opinion, an analysis, a comprehension of our research and work objects. Such a methodology presents a challenge as much as an advantage; it calls for dialogues among different narratives, including their similarities as well as their differences and embracing all their complexities and paradoxes. Found-footage films can play a role in pointing to these and to the resulting opportunities for enriching our archival ideas and practices.

Parties annexes

Biographical note

Annaëlle Winand is a postdoctoral fellow at the Département des sciences historiques de l’Université Laval (Québec). She holds a PhD from the École de bibliothéconomie et des sciences de l’information (Université de Montréal) and a master’s degree in history and archives from the Université catholique de Louvain (Belgium), where she also worked as an archivist. Her research focuses on the notions of archive(s), unarchivable (inarchivable), and archival unconceived (impensé) in experimental found-footage films and videos as well as in the field of community archives. She works actively in several research projects, including Autres archives, autres histoires: Les archives d’en bas au Québec et France (Université Laval, Québec, and Université d’Angers, France).

Notes

-

[1]

International Council on Archives, “What Are Archives?” ICA, accessed July 18, 2022, https://www.ica.org/en/what-archive.

-

[2]

In the cinema studies literature used to prepare this research, we have counted around 550 film titles that were identified as found footage. This number represents a small amount of the production in the field, and therefore lacks representation, mostly concerning the more recent works made by women and BIPOC filmmakers; it should be updated to include grassroots sources such as distributors, festivals, and magazines that specialize partially or entirely in found footage work.

-

[3]

Michel Foucault, L’archéologie du savoir (Paris: Gallimard, 1969).

-

[4]

Jacques Derrida, Mal d’archive: Une impression freudienne (Paris: Galilée, 1995).

-

[5]

Ann Laura Stoler, “Colonial Archives and the Arts of Governance,” Archival Science 2, no. 1–2 (2002): 87–109, 93, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02435632.

-

[6]

Eric Ketelaar, “Archival Turns and Returns,” in Research in the Archival Multiverse, ed. Anne J. Gilliland, Sue McKemmish, and Andrew J. Lau (Clayton, VIC: Monash University Publishing, 2017), 236, https://doi.org/10.26530/oapen_628143.

-

[7]

Ketelaar, “Archival Turns and Returns,” 238.

-

[8]

Hal Foster, “An Archival Impulse,” October, no. 110 (Fall 2004): 3–22, https://doi.org/10.1162/0162287042379847.

-

[9]

Hal Foster, Bad New Days: Art, Criticism, Emergency (London: Verso, 2015), 35.

-

[10]

For a broad and detailed literature review on the uses of the concept of archive(s) in humanities, art, and cinema, see Annaëlle Winand, “Entre archives et archive: L’espace inarchivé et inarchivable du cinéma de réemploi” (PhD diss., Université de Montréal, 2021), 35–74, http://hdl.handle.net/1866/26403.

-

[11]

Sophie Cook, Beatriz Bartolomé Herrera, and Papagena Robbins, “Interview with Rick Prelinger,” Synoptique: An Online Journal of Film and Moving Image Studies 4, no. 1 (2015): 165–91, 190.

-

[12]

Michelle Caswell, “‘The Archive’ Is Not an Archives: On Acknowledging the Intellectual Contributions of Archival Studies,” Reconstruction: Studies in Contemporary Culture 16, no. 1 (2016), https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7bn4v1fk.

-

[13]

Caswell, “‘The Archive’ Is Not an Archives.”

-

[14]

Joan M. Schwartz and Terry Cook, “Archives, Records, and Power: The Making of Modern Memory,” Archival Science 2, no. 1–2 (2002): 1–19, 2, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02435628.

-

[15]

Eric Ketelaar, “Archivalisation and Archiving,” Archives and Manuscripts 27, no. 1 (1999): 56–61, 55, https://publications.archivists.org.au/index.php/asa/article/view/8759.

-

[16]

Winand, “Entre archives et archive.”

-

[17]

See Yvon Lemay and Anne Klein, “Archives et création: Bilan et suites de la recherche,” in Archives et création: Nouvelles perspectives sur l’archivistique, Cahier 3, ed. Yvon Lemay and Anne Klein (Montréal, QC: Université de Montréal, École de bibliothéconomie et des sciences de l’information EBSI, 2016), http://hdl.handle.net/1866/16353; Anne Klein, Archive(s), mémoire, art: Éléments pour une archivistique critique (Québec, QC: Presses de l’Université Laval, 2019); and Yvon Lemay, “De la diffusion à l’exploitation: Notes de recherche 1” (annotations by A. Klein) (Montréal, QC: Université de Montréal, École de bibliothéconomie et des sciences de l’information EBSI, 2017), http://hdl.handle.net/1866/20910.

-

[18]

Anne Klein and Yvon Lemay, “The Artistic Usage of Archives Through the Benjaminian Lens,” Acervo: Revista do arquivo nacional 32, no. 3 (2019): 37–47, 38.

-

[19]

See Schwartz and Cook, “Archives, Records, and Power”; and Tom Nesmith, “Seeing Archives: Postmodernism and the Changing Intellectual Place of Archives,” American Archivist 65, no. 1 (2002): 24–41, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40294187.

-

[20]

Tom Nesmith, “Toward the Archival Stage in the History of Knowledge,” Archivaria, no. 80 (Fall 2015): 119–145, 122, https://archivaria.ca/index.php/archivaria/article/view/13546.

-

[21]

Winand, “Entre archives et archive,” 250.

-

[22]

See Nathalie Piégay-Gros, Le futur antérieur de l’archive (Rimouski, QC: Tangence Éditeur, 2012); Tim Dean, “Pornography, Technology, Archive,” in Porn Archives, ed. Tim Dean, Steven Ruszczycky, and David Squires (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015).

-

[23]

Yvon Lemay, “Le détournement artistique des archives,” in Les maltraitances archivistiques: Falsifications, instrumentalisations, censures, divulgations, ed. Paul Servais, Françoise Mirguet, and Françoise Hiraux (Louvain-la-Neuve, BE: Academia-Bruylant, 2010).

-

[24]

Terry Cook, “Macroappraisal and Functional Analysis: Appraisal Theory, Strategy, and Methodology for Archivists,” in L’évaluation des archives: Des nécessités de la gestion aux exigences du témoignage (Montréal, QC: Groupe interdisciplinaire de recherche en archivistique, 1998), 28.

-

[25]

Carol Couture, “Archival Appraisal: A Status Report,” Archivaria, no. 59 (Spring 2005): 83–107, 84, https://archivaria.ca/index.php/archivaria/article/view/12502.

-

[26]

Carol Couture, “Les fondements théoriques de l’évaluation des archives,” in L’évaluation des archives , 13–14.

-

[27]

See Tom Nesmith, “Archivaria After Ten Years,” Archivaria, no. 20 (Summer 1985): 13–21; Tom Nesmith, “The Concept of Societal Provenance and Records of Nineteenth-Century Aboriginal–European Relations in Western Canada: Implications for Archival Theory and Practice,” Archival Science 6, no. 3–4 (2006): 351–60, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10502-007-9043-9.

-

[28]

Eric Ketelaar, “Archivalisation and Archiving”; Eric Ketelaar, “Tacit Narratives: The Meaning of Archives,” Archival Science 1, no. 2 (2001): 131–41.

-

[29]

Tom Nesmith, “Still Fuzzy, But More Accurate: Some Thoughts on the ‘Ghosts’ of Archival Theory,” Archivaria, no. 47 (Spring 1999): 136–50; Schwartz and Cook, “Archives, Records, and Power”; and Brien Brothman, “Orders of Value: Probing the Theoretical Terms of Archival Practice,” Archivaria, no. 32 (Summer 1991): 78–100.

-

[30]

Verne Harris, “The Archival Sliver: Power, Memory, and Archives in South Africa,” Archival Science 2, no. 1–2 (2002): 63–86, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02435631; Schwartz and Cook, “Archives, Records, and Power.”

-

[31]

Brothman, “Orders of Value,” 82.

-

[32]

Lucy Reynolds, “Outside the Archive: The World in Fragments,” in Ghosting: The Role of the Archive within Contemporary Artists’ Film and Video, ed. Jane Connarty and Josephine Lanyon (Bristol, UK: Picture This Moving Image, 2006), 14.

-

[33]

Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema 3: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998), 176.

-

[34]

Andrew Flinn and Mary Stevens, “‘It is noh mistri, wi mekin histri.’ Telling Our Own Story: Independent and Community Archives in the UK, Challenging and Subverting the Mainstream,” in Community Archives, the Shaping of Memory, ed. Jeannette A. Bastian and Ben Alexander (London, UK: Facet Publishing, 2009), 6.

-

[35]

Jacques Derrida, “Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression,” Diacritics 25, no. 2 (Summer 1995), 57.

-

[36]

Brothman, “Orders of Value,” 81.

-

[37]

International Council on Archives, “ICA Code of Ethics,” International Council on Archives, September 6, 1996, https://www.ica.org/en/ica-code-ethics.

-

[38]

International Council on Archives, “What Are Archives?”

-

[39]

Heather MacNeil, “Trusting Records in a Postmodern World,” Archivaria, no. 51 (Spring 2001), 40.

-

[40]

Smith and Hennessy talk about an “anarchival materiality” as a “the force of material decay in the archive. It is a force that changes the order and classification of things. It is a force that obliterates the things that humans try to save.” Trudi Lynn Smith and Kate Hennessy, “Anarchival Materiality in Film Archives: Toward an Anthropology of the Multimodal,” Visual Anthropology Review 36, no. 1 (2020): 113–36, https://doi.org/10.1111/var.12196.

-

[41]

Michel Foucault, Les anormaux: Cours au Collège de France, 1974–1975, ed. François Ewald and Allessandro Fontana (Paris: Gallimard, Le Seuil, 1999), 51.

-

[42]

Michel Foucault, Les anormaux; Jeffrey Jerome Cohen, ed., Monster Theory: Reading Culture (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1996).

-

[43]

Bernd Herzogenrath, “Decasia: The Matter|Image: Film Is Also a Thing,” in The Films of Bill Morrison: Aesthetics of the Archive, ed. Bernd Herzogenrath (Amsterdam, NL: Amsterdam University Press, 2018).

-

[44]

André Habib, “The Self-Portrait and Other Ruins: Reflections on Self Portrait Post Mortem and Auto Portrait / Self Portrait Post Partum,” in Imprints: The Films of Louise Bourque, ed. Stephen Broomer and Clint Enns (Ottawa: Canadian Film Institute, 2021).

-

[45]

André Habib, “Interview with Alexei Dmitriev,” Found Footage Magazine, no. 5 (March 2019): 4245.

-

[46]

Marco Bologna, “Historical Sedimentation of Archival Materials: Reinterpreting a Foundational Concept in the Italian Archival Tradition,” trans. Gabriella Sonnewald, Archivaria, no. 83 (Spring 2017), 41.

-

[47]

Bologna, “Historical Sedimentation,” 42.

-

[48]

André Habib, “Le temps décomposé: Cinéma et imaginaire de la ruine” (PhD diss., Université de Montréal, 2008), 321.

-

[49]

Sharon Sandusky, “The Archeology of Redemption: Toward Archival Film,” Millenium Film Journal, no. 26 (Fall 1992), 12.

-

[50]

MacNeil, “Trusting Records in a Postmodern World,” 46.

-

[51]

Jaimie Baron, The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History (London: Routledge, 2014), 128.

-

[52]

David Thomas, Simon Fowler, and Valerie Johnson, The Silence of the Archive (Chicago: ALA Neal-Shuman, 2017).

-

[53]

Nesmith, “Still Fuzzy, But More Accurate.”

-

[54]

Jacques Derrida, Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International (New York: Routledge, 1994), xviii.

-

[55]

Derrida, Specters of Marx, 48.

-

[56]

María del Pilar Blanco and Esther Peeren, “Introduction: Conceptualizing Spectralities,” in The Spectralities Reader: Ghosts and Haunting in Contemporary Cultural Theory, ed. María del Pilar Blanco and Esther Peeren (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 21.

-

[57]

Verne Harris, Ghosts of Archive. Deconstructive Intersectionality and Praxis (Abingdon, UK: Routledge, 2021), 54.

-

[58]

The function of diffusion (here translated as “dissemination”) is particular to archival science in Québec. It regroups all actions performed by an archivist to make archives available and known. It can be divided in four groups of actions: valorization, promotion, communication, and reference. See Normand Charbonneau, “La Diffusion,” in Les Fonctions de l’archivistique contemporaine, ed. Carol Couture (Sainte-Foy, QC: Presses de l’Université du Québec, 1999).

-

[59]

The Paper Print Collection is a collection of thousands of motion pictures that were registered for copyright as photographs on paper. The process was used by film companies to copyright their films to the U.S. Copyright Office at the Library of Congress (copyright law did not cover motion pictures until 1912). The collection was forgotten before being “rediscovered” by employees and artists. See Dan Streible, “The Film of Her: The Cine-Poet Laureate of Orphan Films,” in Herzogenrath, The Films of Bill Morrison; Charles “Buckey” Grimm, “A Paper Print Pre-History,” Film History 11, no. 2 (1999): 204–16.

-

[60]

Michelle Caswell, “Inventing New Archival Imaginaries: Theoretical Foundations for Identity-Based Community Archives,” in Identity Palimpsests: Archiving Ethnicity in the U.S. and Canada, ed. Dominique Daniel and Amalia S. Levi (Sacramento, CA: Litwin Books, 2014).

-

[61]

Verne Harris, “On (Archival) Odyssey(s),” Archivaria, no. 51 (Spring 2001): 13.

-

[62]

Derrida, quoted in Nesmith, “Still Fuzzy, But More Accurate,” 149.

-

[63]

Harris, Ghosts of Archive, 158.

-

[64]

Winand, “Entre archives et archive.”

-

[65]

For example, see Les archives gaies du Québec, accessed [February 15, 2023,] http://agq.qc.ca; Archives lesbiennes du Québec, accessed [February 15, 2023,] http://www.archiveslesbiennesduquebec.ca; and Archives révolutionnaires, accessed [February 15, 2023,] https://archivesrevolutionnaires.com.

Liste des figures

figure 1

The unarchived (inarchivé) and the unarchivable (inarchivable) dimensions

figure 2

The unarchived, the unarchivable, and the unconceived