Résumés

Abstract

Indigenous Bolivians, especially women, are climbing the ranks of global multilevel marketing (MLM) companies like Herbalife, Omnilife, and Hinode, seeking to join Bolivia’s purportedly rising Indigenous middle class. Through MLMs, Indigenous direct sales distributors pursue a dignified life materialized in better homes, smart dressing, international travel, and the respect they receive at recruitment events. In their recruitment and sales pitches to potential buyers and downline vendors, Indigenous distributors fashion testimonials about their successes that explicitly critique existing avenues of class mobility and their racialization in two ways. First, these testimonials counter the skepticism that multilevel marketing companies face by citing a litany of false promises offered by higher education, salaried employment, and public sector jobs—avenues long heralded as the stepping stones to entwined racial and class mobility in Bolivia. They further voice their frustrations with perceived status hierarchies and organizational barriers among Indigenous merchants, highlighting their own sense of alienation from the connections and protections that have enabled the financial success of other Indigenous entrepreneurs. Second, while lodging these critiques, distributors repurpose racialization toward their own recruitment ends. As MLM distributors pursue their visions of the good life, the testimonials that Indigenous MLM recruiters craft to enable their ascent expose, rely on, and rework the bounds of racial capitalism. Ultimately, their critiques reveal how the racial partitioning that enables capitalist extraction operates through the work of direct sales.

Keywords:

- Racial capitalism,

- class,

- racialization,

- Andes,

- indigeneity,

- multilevel marketing

Résumé

Les Autochtones boliviens, en particulier les femmes, gravissent les échelons des sociétés mondiales de marketing à plusieurs niveaux (MLM) telles que Herbalife, Omnilife et Hinode, cherchant à rejoindre la classe moyenne autochtone bolivienne prétendument en plein essor. Par le biais des MLM, les distributeurs autochtones de vente directe aspirent à une vie digne, matérialisée par de meilleures maisons, des vêtements élégants, des voyages internationaux et le respect qu’ils reçoivent lors des évènements de recrutement. Dans leurs discours de recrutement et de vente aux acheteurs potentiels et aux vendeurs en aval, les distributeurs autochtones mettent en scène des témoignages de leur réussite qui critiquent explicitement les voies existantes de la mobilité de classe et leur racialisation, et ce de deux manières. Tout d’abord, ces témoignages contrecarrent le scepticisme auquel sont confrontées les sociétés de marketing à plusieurs niveaux en citant une litanie de fausses promesses offertes par l’enseignement supérieur, l’emploi salarié et les emplois du secteur public – des domaines longtemps considérés comme les tremplins de la mobilité raciale et de classe en Bolivie. En outre, ils expriment leurs frustrations face aux hiérarchies de statut et aux barrières organisationnelles perçues parmi les commerçants autochtones, soulignant leur propre sentiment de marginalisation par rapport aux relations et aux protections qui ont permis la réussite financière d’autres entrepreneurs autochtones. En second, tout en tenant compte de ces critiques, les distributeurs réaffectent la racialisation à leurs propres fins de recrutement. Alors que les distributeurs de marketing à plusieurs niveaux poursuivent leur vision de la bonne vie, les témoignages que les recruteurs autochtones de marketing à plusieurs niveaux élaborent pour permettre leur ascension exposent les limites du capitalisme racial, s’appuient sur elles et les retravaillent. Finalement, leurs critiques révèlent comment le cloisonnement racial qui permet l’extraction capitaliste opère à travers le travail de la vente directe.

Mots-clés :

- Capitalisme racial,

- classe,

- racialisation,

- Andes,

- autochtonie,

- marketing à plusieurs niveaux

Corps de l’article

An Invitation

When Casimira Alanoca Guaygua[1] takes the stage at her own Herbalife Club, she is confident, eyes bright as she scans her small audience at the global multilevel marketing company’s (MLM) recruitment event. “[What’s] the most important thing for me?” she asks. “It’s that you are here. Why? Because successful people are here. Normal people are there, wasting their time,” she asserts, gesturing toward the windows overlooking the Ceja, El Alto, Bolivia’s commercial district and its street vendors. “If you don’t change your understanding, you are never going to get ahead. You’ll live on the ladera—that’s all,” Casimira warns her audience, referencing the steep canyon walls that lead from El Alto to Bolivia’s adjacent seat of government, La Paz.

Living on the ladera is a pointed reference for this audience. Ladera indexes a host of spatial associations of race and class.[2] The ladera is heavily populated by spindly, unfinished homes—unfinished because, like many places in the Andes, residents build up, adding new floors atop the old, as their fortunes rise, suspending construction during lean times.[3] Historically, the neighbourhoods on the ladera have been home to the capital’s Indigenous, working class, and poorer residents—acting as a transitional space between La Paz, home of many mestizo[4] elites, and the heavily Indigenous-identifying city of El Alto, where we are gathered for this recruitment event. The young adults attending Casimira’s event are likely the children of Indigenous Aymara parents who migrated from highland hamlets or from Bolivia’s mining centers following the privatization of state-owned companies in 1994.

In some ways, Casimira’s assertion is a bit dated, as the often-heralded but also contested rise of Bolivia’s Indigenous middle classes—comprised of electronics retailers and used clothing wholesalers, among other comerciantes or merchants—has reworked the cities’ racial and class cartography. These merchants offer a visible manifestation of Indigenous socio-economic mobility and the fluidity or “multidimensionality and undecidability between multiple classificatory criteria” that comprise these categories (Ravindran, 2019, 222).[5] But Casimira invokes this spatial shorthand for mobility’s stagnation to urge new recruits to join the company. If you do not transform your way of thinking, it’s on the ladera, she exhorts her audience, where “you’ll grow old and die. But if you want to live in different places, have other interests, think differently, eat differently, be different, you have to change.” Casimira later adds, “People who do not know how to read are working here, changing their lives. [In Herbalife], people aren’t picked for being the right colour, for having money, or being such and such a person. Here, anyone can do it.” Casimira then turns to how those cast out of “traditional” modes of mobility due to their differences are achieving success through Herbalife. “We have all improved ourselves together, and we all work to grow. We move up levels together,” she concludes with satisfaction.

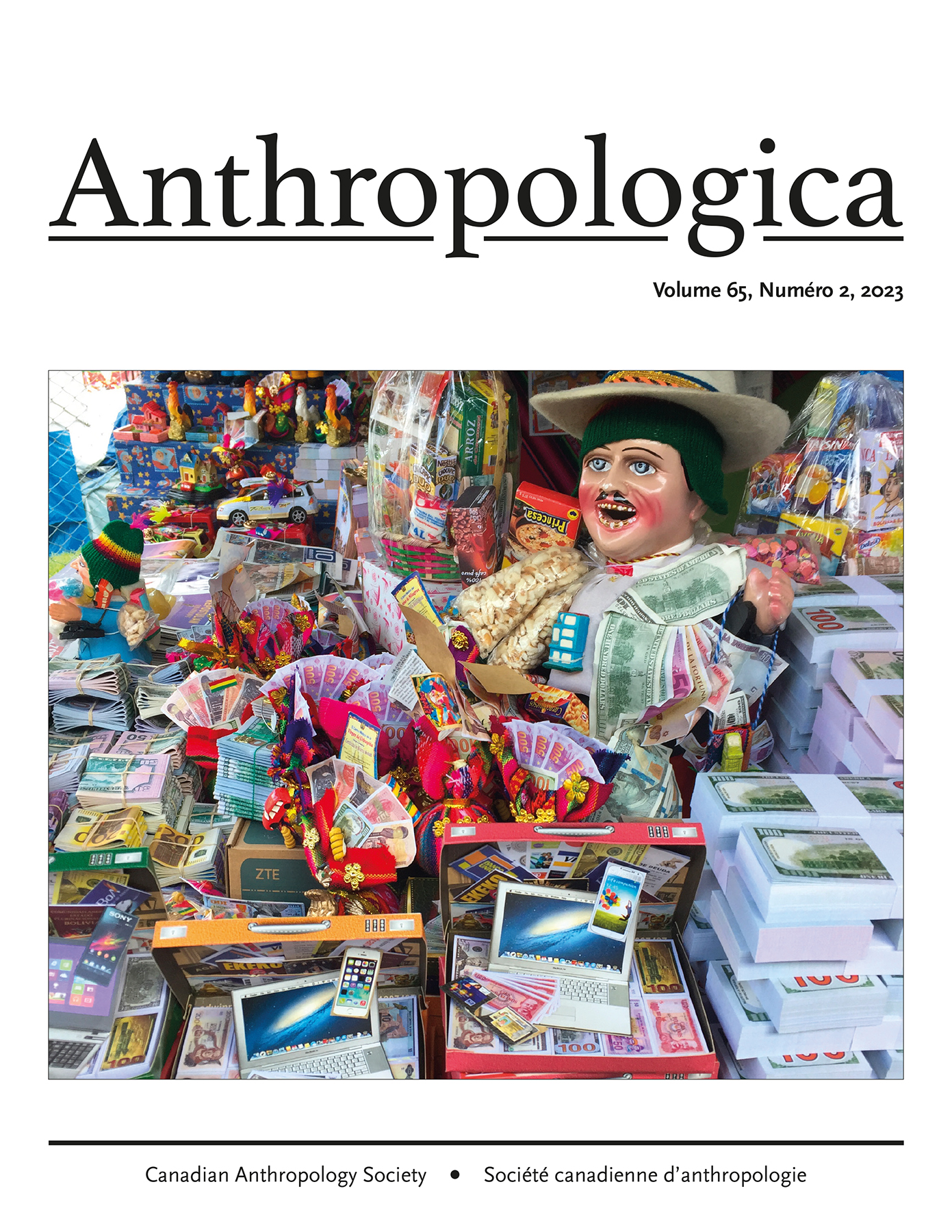

Throughout El Alto, Indigenous Bolivians like Casimira are joining the ranks of global multilevel marketing (MLM) companies like Herbalife, Omnilife, and Hinode (see Figure 1). Multilevel marketing entails the direct or “networked” sales of products ranging from nutritional supplements to housewares. The “level” in multilevel refers to the practice of direct sellers recruiting new people into their “downlines” with commissions for sales flowing upward. MLMs regularly inspire comparisons to Ponzi or Pyramid schemes. While MLMs share a similar upline/downline structure, illegal pyramid schemes generate payments for their members primarily or solely by recruiting new people to the “base.” At some point, downline recruitment saturates the market or government regulators categorize it as a scam and end it—and the upward payment scheme collapses, leaving many people at the bottom bereft of their investments.

Figure 1

Although legal in many countries, MLMs follow similar recruitment patterns and periodically face investigations into their business practices. Herbalife, for example, acknowledges that 90 percent of “distributors make little or no income,” and many lose money.[6] In 2017, the company was forced to return $200 million dollars to former distributors and restructure its business model in a settlement with the US Federal Trade Commission to avoid categorization as a criminal pyramid scheme.[7] Despite these persistent doubts and investigations, MLMs continue to expand globally, including in Bolivia.

Many studies of MLMs trace how their fortunes have risen alongside neoliberal ideologies of entrepreneurship, self-responsibilization, and state decentralization.[8] Other studies foreground faith as a central component of their appeal, showing how MLM adherents draw on prosperity theologies to buoy entrepreneurial aspirations.[9] These studies rightly complicate simplistic explanations that might reduce people’s participation in “fast money schemes” to avarice or a willingness to deceive others.

Yet, in Bolivia, accounts of the neoliberalism-MLM nexus present a puzzle. The neoliberal, race-free promises made by MLMs gained traction during the era of Bolivia’s first Indigenous-identifying president, Evo Morales, and his Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) Party. Morales and MAS came to power on a platform that critiqued neoliberal capitalism, recentred the state as the provider of social safety nets, and celebrated collectivist modes of political engagement and Indigenous resurgence. MLMs, with their grounding in free enterprise ideologies, seem to represent the antithesis of this project. And yet, in the years since Morales took office—and despite the formidable sales realities mentioned above—MLMs proliferated in Bolivia.[10] What to make of this seeming paradox?

To apprehend the appeal of MLMs in the Andes requires attention to how racialization operates in their global expansion. Existing work on MLMs has tended to sidestep discussions of race, centring instead on religiosity, gender, and class—although there are a few exceptions. For example, Davor Mondom explores how American MLM giant Amway recognized persistent discrimination facing Black Americans, yet framed entrepreneurship as the solution to systemic racism (2019, 128). I examine how Indigenous Aymara distributors working in Bolivian MLMs pursue what they term a dignified life materialized in better homes, smart dressing, international travel, and the respect they receive at recruitment events—respect they frequently do not experience elsewhere, as racially-marked citizens.[11]

In their pitches to potential downline vendors, direct sales distributors like Casimira fashion testimonials about their successes that critique predicted avenues of class mobility for Indigenous Bolivians and these avenues’ racialization. These testimonials counter the skepticism that MLMs face by citing a litany of “false promises” offered by state-sponsored higher education, salaried employment, and public sector jobs—pathways long heralded as the stepping stones to racialized class mobility in Bolivia and the Andes. Nevertheless, while lodging these economic critiques, distributors repurpose racialization toward their own recruitment ends. Ultimately, their critiques reveal how the racial partitioning that enables capitalist extraction operates through the work of direct sales.[12]

Herbalife (among other MLMs) is successful in El Alto in part because it taps into people’s profound frustrations and longing for a better life—for themselves, and for their loved ones. But the company’s success is built on Bolivia’s foundation in Indigenous dispossession, exploitative labour practices, and white supremacist ideologies denigrating Indigenous humanity. As distributors like Casimira seek to overcome those long-sedimented inequalities through their investment in multilevel marketing, they secure loans, liquidate property, and pour savings and retirement funds into an investment scheme where wealth ultimately flows upward—into corporate coffers and those of higher-ranking distributors. The testimonials recruiters like Casimira craft to enable their ascent expose, rely on, and rework the bounds of racial capitalism as MLMs extract value from Indigenous vendors whose narratives of racial discrimination operate as downline recruitment tools—but also meaningful ways to critique their own experiences of mobility’s stagnation.

Herbalife is just one of many MLMs expanding in El Alto—where direct sales motivational speakers, DVDs, and pamphlets circulate widely—offering techniques for aspiring distributors to cultivate their pitches. These assorted training materials comprise a much larger MLM ecosystem even as individual MLMs produce their own marketing materials and help cultivate particular testimonial tropes. Accordingly, looking for a corporate mastermind behind the re-packaging of Herbalife’s promises—through a racialized script of Indigenous mobility—cannot explain how MLMs gain traction among new adherents, particularly those who are subject to racism in their daily lives. Rather, Indigenous recruiters like Casimira astutely vernacularize MLM tropes in ways they know will resonate with their particular audiences. This is the hydra-headed quality of the MLM-iteration of racial capitalism.

I conducted fieldwork for this project during the 2018-2019 academic year, but build on ongoing research in El Alto and La Paz since 2008. I begin by reviewing the context of racialization in the Andes before discussing three lines of critique voiced by Indigenous MLM distributors who both decry and repurpose ideologies of racialized class mobility toward recruitment. Let us return, then, to Casimira’s Herbalife Club, and her testimonial in-progress.

Getting Ahead Through Education and Professionalization

In her testimonial, Casimira frequently shifted between the language of superación (improving oneself) and the idea that Herbalife would help its recruits salir adelante (or get ahead). As in much of the Andes, Alteños associate superación and saliendo adelante with education (itself carrying the double meaning of formal schooling and gaining cultural capital/refined manners) as well as professionalization.[13] These interlocking idioms carry racial, spatial, and classed undertones, particularly when used by Indigenous migrants to the city. These migrants include Casimira, who, in her fifties, moved to El Alto from a rural hamlet north of Lake Titicaca.

Such idioms present education as a crucial means to overcome poverty and achieve respectability with salaried employment. Yet notions of respectability in El Alto are often framed in the language of “good presentability” which, Ravindran (2021)[14] argues, reflects an entrenched yet slippery pigmentocratic rationality (colorism). As Ravindran and Canessa (2012) show, evaluations of skin colour remain salient even as they intersect with other fluid criteria of racialization rooted in dress, cultural capital, language, and other ambiguous factors such as perceived comportment.

These racialized ideologies of progress map onto people’s movement from countryside to urban space and the social process of Indigenous whitening or blanqueamiento,[15] evincing what McKittrick (2006) has called the “classificatory where of race.” It is for this reason that Luykx calls rural schooling in Bolivia the “citizen factory” in a context where Indigenous Bolivians are “seen as insufficiently nationalized…not quite Bolivian” because of their racial difference (1996, 240).

Amid the Morales Administration’s vocal revalorization of Indigeneity—and movements for Indigenous revindicación (vindication of demands) that pre-dated his election—many young, politically active Bolivians reject discourses that frame Indigenous Bolivians as suspect citizens and that cast class mobility as a process of whitening or shedding one’s Indigenous identity. In previous decades, shedding one’s pollera, the multitiered skirts worn by Aymara and Quechua women, stood as a symbol of that racial transformation.[16] By contrast, revindicación inverts the temporal dimensions of getting ahead as a forward marching trajectory of progress that breaks with the past and demands Indigenous assimilation. Revindicación instead centres “recovered” and enduring Indigenous lifeways that have resisted colonial erasure as the foundation for a modern, decolonized Bolivia. The Morales Administration thus celebrated the inclusion of women de pollera into positions previously denied them, foregrounding their status as professionals running powerful offices and shaping national policy.[17] Nevertheless, being a woman de traje (who wears “Western”-style attire rather than a pollera) remains tied to notions of professionalization—an aspiration that retains its potency in familiar conversations about intergenerational class mobility and its impediments.

Yet at recruitment events in El Alto, speakers tasked with Herbalife’s sales pitch routinely lambast the twin aspirations of attending college and becoming a “professional,” that is, a white-collar, salaried employee. Consider Miriam, a diminutive Aymara woman de pollera whose Herbalife club overlooks El Alto’s massive 16 de Julio open-air market. Miriam drew a stark contrast, telling me:

Studying is expensive. Now, if you want to be a good professional, you have to spend a house-load of money. So many of the señoras [de pollera] can’t find work. They can only try to sell on the street [as ambulant or small-scale vendors], or continue washing clothes as empleadas [housekeepers]. [In Herbalife] nobody asked me for my CV, nobody asked me for my diploma. Nobody asked if I could read or write. I wouldn’t exchange this company for the world.

Here, Miriam quickly moves from a critique of education’s prohibitive costs to the sense that for many Alteñas, employment opportunities remain limited to jobs that are racially marked as Indigenous and low income: being an empleada (maid) or working as an itinerant street vendor—rather than a wealthier wholesaler, pointing to racialized class hierarchies internal to Aymara residents of El Alto.

By contrast, at multiple MLM recruitment events, I listened as speakers invoked a different kind of education, one achieved by attending the company’s “University of Success.” Braiding together Herbalife’s messaging around the “University of Success” with the locally-significant category of wholesaler, or mayorista, as described later, Miriam told me, “[Herbalife] sends you diplomas! They’ve sent me something like four. They sent me one for becoming a mayorista. This is recognition that you have passed [the test]. It’s like you got your diploma. You’ve studied for your degree.”

What is striking in her word choice is the way Miriam substitutes university diplomas that typically signal receiving one’s licenciatura—akin to a bachelor’s degree, but indexing one’s status as a professional—with another kind of titling: a diploma for achievement within the MLM framework of upline advancement. Recruiters thus supplant the racialized scripts of state-sponsored education as a pathway to socio-economic mobility with an alternative educational track (a “University of Success”) complete with didactic DVDs, reading lists, instructional courses, and titling.

Recruiters further asserted that for those lucky souls who do join the ranks of salaried employees, the prospects are no better. As Casimira challenged her audience, “Many people say ‘I have to study! I have to become a professional! I have to earn…a fixed salary.’ But that secure salary is poor.” I heard similar iterations of this critique at nearly every recruitment event I attended. In many ways, these pitches recall classic critiques of corporate capitalism’s disappointments and “deceptions” circulated by other MLMs dating back to Amway and other established direct sales brands in the U.S. (Mondom 2019). But in the Bolivian context, the racial underpinnings of these presumed pathways to upward mobility—and the ways MLMs promise to transcend racial discrimination—come to the fore.

Testimonials like Casimira’s concretize these critiques in their own “before and after” accounts of life prior to joining Herbalife. Casimira and her husband, Luís, were teachers in a rural Andean province. Both regularly used those salaried public sector jobs as foils in their speeches. By attending the Normal, or Teachers’ College—the “citizen factory” par excellence—Casimira and Luís had achieved respectable salaried employment. Casimira’s account emphasized the hardship she faced as a young mother who insisted on pursuing her education. Casimira’s invocation of those salaried jobs hailed an educational system that has furthered ideologies of racial and cultural mestizaje (mixture) as a means of Indigenous assimilation. But it also hails a kind of job—being a professional rather than, say, a housekeeper or market woman—toward which many Indigenous Bolivians aspire, for themselves or for their children.

Both spouses, however, lament that neither education nor their status as professionals proved satisfying or financially rewarding. Instead, they pointed toward stagnated teacher wages and the very mechanisms through which teachers and other workers might agitate for higher salaries: namely, their sindicato or union. As Luís shared before his wife took the stage, “Before, we did a lot to try to get the government to raise our salaries. We marched. We had strikes. We blockaded roads. And what did it get us? I wasted more than 35 years of my life working like that. You would think that it would have been a more dignified life, but it wasn’t.”

These rhetorical moves recall the promises made by the intellectual architect of “compassionate capitalism,” Amway co-founder Richard DeVos, who combined free enterprise ideology with a critique of actually existing capitalism by appealing to American workers who felt “dissatisfied with traditional, nine-to-five employment, who felt that their jobs did not pay enough or were not emotionally rewarding, and who desired greater control over their lives” (Mondom 2018, 345).[18] Notably, Casimira and Luís extend “compassionate capitalism’s” ideological critique of low-wage jobs to include labour unions and their inability to secure better salaries for members, positioning Herbalife entrepreneurship as a real means to achieve that more “dignified life.”

Here, the free enterprise ideology of “compassionate capitalism” finds resonance with widespread frustrations of Bolivians working in public sector jobs who have seen their wages stagnate, and who sometimes work for months at a time without pay.[19] My argument, however, is that testimonials like those of Miriam, Luís, and Casimira expose the racialized underpinnings of that dissatisfaction and appeals to respectability—state-sponsored education and professionalization was meant to provide a pathway to class mobility that was always-already racialized as a process of whitening. However, the lived experience of pursuing those goals through higher education and salaried employment as “professionals” has proven confounding for many in Casimira’s audience, who still face racial discrimination as they pursue these goals.[20]

As Melamed argues, the “antinomies of accumulation require loss, disposability, and the unequal differentiation of human value, and racism enshrines the inequalities that capitalism requires… it does this by displacing the uneven life chances that are inescapably part of capitalist social relations onto fictions of differing human capacities, historically race” (2015, 77). In this context, much has been made about Bolivia’s so-called rising Indigenous middle classes and the ways Indigenous comerciantes (merchants) have managed to accumulate wealth while sustaining cultural practices that resist capitalist flattening. And, questions over how to characterize this merchant class have driven academics and popular discourses alike. My aim in the next section is not to resolve how one might measure or otherwise account for Bolivia’s Indigenous middle classes, but rather to show how appeals to Indigenous entrepreneurialism are both subject to MLM critique and enshrined in recruiters’ celebration of Herbalife’s inclusivity, accessibility, and variations on racialized respectability.

Getting Ahead as Indigenous Entrepreneurs: Of Mayoristas and Millionarios

Casimira and Luís were not alone in turning their ire on Bolivia’s many forms of collective action that fall under the banner of sindicatos (unions) or gremios (guilds). Casimira and Luís’s son-in-law, Plácido, sold motivational CDs and DVDs on the street before joining his wife as a Herbalife distributor. Like his in-laws, he expressed frustration with existing channels of collective bargaining or political pressure. Unlike his in-laws, however, it wasn’t the failure of such unions that frustrated him, but rather the fact that he did not believe they were accessible to him.

Bolivian MLMs operate amid El Alto and La Paz’s robust “popular economies” (see Müller and Colloredo-Mansfeld 2018).[21] Bolivia’s open-air markets include both ambulantes (ambulant vendors) and puestos fijos (fixed stalls), and their vendors must join politically powerful gremios (guilds/unions) that are organized geographically and by trade (Goldstein 2016). Herbalife recruiters frequently leaflet in these busy markets, renting club space alongside brick-and-mortar shops that line commercial districts. They smile invitingly and thrust flyers toward hurried market-goers, trying to entice them to sample Herbalife products. Other potential consumers/downline recruits are themselves ambulant vendors or labour out of more permanent stalls.

In a context where formal wage labour is absent or unreliable, many Bolivians have turned to commerce as a means of generating an income, with those pursuits further galvanized by celebratory accounts of entrepreneurship. However, newcomers face significant barriers as they navigate the intensive demand for start-up capital, a lack of contacts or knowledge about how to gain entrance into commercial networks, and the significant costs of joining trade organizations or procuring space in the city’s markets (Goldstein 2016; Müller 2019).[22]

In his own account of his efforts to succeed at commerce, Plácido described how hard it was as an “informal” street vendor to go through the bureaucratic hoops required to “regularize” his motivational DVD business venture under the Morales Administration’s expanding efforts to enforce tax regulations. Plácido explained his frustration:

Every Bolivian needs to pay taxes except it doesn’t work that way. Because in the big unions,[23] there are big entrepreneurs, really big, that really make a lot of money each day but don’t pay taxes. I’m talking about the 16 de Julio market. I’m talking about Calle Granaderos or Tumusla, those places. And we are talking about Huyustus and Eloy Salomón—those are the big ones. They don’t give receipts, and they all have a simplified tax regimen, why? Because they belong to the union.

With these references, Plácido specifies locations in the conjoined cityscapes of El Alto and La Paz, where comerciantes are accruing significant wealth selling appliances and electronics and as mayoristas (wholesalers) who supply smaller vendors in the markets. But, his discussions of comerciantes must also be understood in the context of how these groups are racialized in Bolivia, as reflected in both scholarly and popular discourses surrounding Indigenous entrepreneurialism—and efforts to define what some have termed Bolivia’s Indigenous “Aymara bourgeoisie.”[24]

Tassi and colleagues emphasize how Indigenous comerciantes enact a mode of “citizenship that does not presuppose a prior process of transformation directed by external forces or criteria ([namely] civilization, modernization, miscegenation, whitening, etc.)” (2013, 3). Comerciantes they argue, have worked to “create spaces outside the spheres of official scrutiny and, therefore, consolidate their own forms of social organization” (2013, 2). Indeed, in the bustling commercial districts where many Herbalife clubs are located, the power of such guilds/associations is palpable.

Many Aymara mayoristas (wholesalers) emerged from families that migrated to the north of Chile during the 1980s during a period of economic liberalization and limited institutional presence/regulation on the border (Rea Campos 2016). These migration flows helped Aymara comerciantes establish intergenerational cross-border ties that, Rea Campos argues, facilitated their rise as importers of merchandise from Asia, allowing them to “transcend national borders and emerge as global and competitive economic agents” (2016, 380, 396, translation mine).

These studies reveal how Aymara cultural practices of mutual aid sustain “communitarian alliances,” even as they are “not exempt from conflict, [social] differentiation, and inequality” (Rea Campos 2016, 397, translation mine). As Müller shows, the “interweaving of social and commercial relationships” among Bolivian electronics commerciantes “has provided extraordinary opportunities for upward mobility for some Bolivian traders, while others have been left behind” (2018, 21).

Ultimately, Tassi et al. argue that the operations of these family-run businesses and their incorporation into guilds offer visions of “meaningful autonomy” for Indigenous merchants (2013, 10). Nevertheless, these highly profitable strategies and autonomous institutional arrangements co-exist with persistent narratives that locate these same commercial districts and their business operations at “the limit of official legality,” in explicitly racialized language (Tassi et al 2013, 4). Popular discourses characterize them as “improvised, dirty, and illegal,” a narrative that market researchers write firmly against, especially as perceptions of filth in Andean open-air markets are yoked to gendered, racist stereotypes.[25]

Plácido and Miriam’s experiences, however, offer a different angle on these racially-charged representational regimes and popular discourses around Indigenous entrepreneurialism, perceived political power, and illegality. Plácido is shut out of these access points, struggling to play by the rules of bureaucratic formalization and failing, while he perceives well-established Aymara comerciantes as circumventing those regulations through their organizational power. That experience is both particular to Plácido and his ordinary struggles to earn a living amid the Morales Administration’s push for “formalization,” and one that finds support in the MLM language of free enterprise and its rewards.

Plácido couples a familiar bootstrapping vision of upward mobility with a neoliberal critique of fettered entrepreneurship as he bemoans what he calls the “unfair” or “dishonest” competition (competencia disleal) made possible by government connections (pega) and the political might of trade unions. His frustrations also underscore the complex racial terrain of these ideological and bureaucratic struggles. Plácido’s critique inverts questions skeptics might raise about Herbalife and other MLM companies’ legality—concerns Plácido had heard many times before. During our conversations, he often dismissed the idea that Herbalife was a “pyramid scheme.” Instead, he raises the spectre of powerful comerciantes evading regulation—that perceived illegality of Indigenous wealth.

As noted earlier, Miriam highlighted women like herself who could not achieve the status of mayorista in Bolivia’s open-air markets because they lacked the capital and connections to do so, but who nevertheless could be thus crowned and recognized through Herbalife. Miriam insisted that Herbalife offers an alternative to the forms of exclusion one might experience due to the structural constraints that impinge on one’s racially-marked body, the prohibitive costs of accessing higher education, and the absence of institutional supports and political connections that one might otherwise have access to through larger trade unions—but that remain out of reach for small-scale, itinerant vendors.

Merchants in the “popular economy” voice similar concerns amid intense competition. Müller (2019) tracks the caginess with which established Bolivian traders operate as they guard hard-won contacts in China and “infrastructural knowledge,” or, the information, contacts, and access to institutions necessary for the circulation of goods and successful entrepreneurial endeavours. Moreover, as Goldstein (2016, 169) found in Cochabamba’s Cancha market, established fijo vendors spoke disparagingly about ambulantes, deploying racist slurs (that they might themselves endure elsewhere) to safeguard their status as “good,” respectable, and credit-worthy comerciantes in contrast to less successful others.

By contrast, Casimira regularly insisted to me that in Herbalife there is no competition—a statement I struggled to view as anything but marketing patina. Yet, considered alongside the closely-guarded “infrastructural knowledge” observed by Müller and the enduring racial hierarchies of market life, we might interpret her insistence differently: the multilevel mechanisms of Herbalife encourage information sharing as a mode of recruitment—though preferably to one’s own downline. Building a networked sales force encourages sharing information in part because one directly benefits from the human infrastructure that comprises the MLM model. Thus, MLM recruiters acknowledge people’s perception that certain spaces of entrepreneurship are inaccessible to them while casting the company as offering a meaningful alternative to the internal hierarchies of the popular economy that are rife with their own racial connotations—despite celebrations of Bolivia’s Indigenous middle classes. As I show in the final section, contra the disappointments of education, professionalization, and the perceived inaccessibility of entering Bolivia’s Indigenous middle classes, Indigenous Herbalife distributors repurpose their racialization by casting MLMs as opportunities to achieve dignity, respectability, and collective advancement.

Finding Value in Your Points

Most of the attention to race in direct sales has focused on the white middle-class respectability exemplified, for example, in Avon cosmetics’ beauty regimes or the MLM brand LuLaRoe’s leggings empire, which braids together a #GirlBoss model of neoliberal white feminism with Christian—and in LuLaRoe’s case, Mormon—hetero-patriarchal marital norms.[26] By expanding our attention to racialization in direct sales, we can see how the referents to whiteness may shift in the Latin American context, revealing how recruiters vernacularize MLM tropes within locally-meaningful racial scripts, including beyond the Andes.

In El Alto, testimonials like those delivered by Casimira and Luís seize on Indigenous audience members’ sense of being sold a bill of goods that fraudulently promised upward mobility for Indigenous Bolivians through university education and subsequent salaried employment as “professionals.” Further, they do not see themselves represented in the accounts of Bolivia’s rising Indigenous middle classes. By contrast, Casimira and Miriam center their positionality as racially-marked Indigenous Bolivians in their recounting of their positive experiences with the company.

Both women regularly note that at international and regional recruitment events, their Indigeneity is valorized. During the testimonial that opened this paper, Casimira told her audience about an experience she had during a trip to Colombia. Pointing to a photo in one of her slides, she explained that she keeps in touch on Facebook with a woman she met there. Casimira recounted,

We greet each other on Face[book], and it seems like she’s published [photographs of] me all over the Internet. She publishes me, saying “A teacher who is more than 60 years old…she’s making history in Herbalife.” So, it’s clear to me that they want to take lots of photographs of us cholitas. Even people in the street stop you and say, “Ma’am, can I get a photo?” There are no cholitas [in Colombia]. A bunch of us cholitas travelled [for this Herbalife event], and wow! Everybody wants to take a photo!

Casimira concludes, listing off the many people who rank high in the Herbalife echelon: “Presidents, millionaires, [they say] ‘Señora, a photo, a photo please!”‘

As Casimira makes clear, while the woman’s Facebook captions may focus on Casimira’s age and occupation, the photo itself is doing other narrative work: Casimira is visibly Indigenous; she is a “cholita,” an iconic figure of feminine Indigeneity now globally recognized in news stories about Indigenous skateboarders, beauty queens, and lucha libre (wrestling).[27] For an international audience, Bolivian women dressed in the polleras (multi-tiered skirts) and bowler hats that mark them as Indigenous—alongside phenotypical traits like darker skin and long black hair in plaits—are valued for their capacity to authenticate Herbalife’s promises and subsequently circulate globally in other distributors’ verbal testimonials and selfies, even if those recruiters are themselves mestizo/white. Casimira was blunt about her understanding of these images’ power as recruitment tools: it’s all about your story and your photos, she once told me, underscoring the interplay between visual (that is, phenotypic) and biographical-cultural modes of racialization.

One woman’s story has come to epitomize Herbalife’s modes of racial inclusion and circulates in many of the testimonials I observed. Her name is Doña Antonia. Speakers regularly invoked Doña Antonia’s name as evidence of Herbalife’s accessibility as a company unsullied by racial or class-based discrimination. During her above testimonial, Casimira upheld Antonia as a model toward which she aspired, saying, “Doña Antonia travels [to international Herbalife conferences] with all of her [downline and biological] children. I am following her path. She is de pollera, a housewife. She’s not a teacher [like me]. She didn’t [even] study! She only went to school through third grade, but she’s a millionaire,” Casimira proclaimed, referencing not Doña Antonia’s actual income, but rather a status level in Herbalife’s upline/downline structure (although that detail may not be apparent to new recruits when they first hear that someone is a “millionaire”).

Here Casimira draws a contrast regarding her own educational standing and Antonia’s. Casimira epitomizes the notion of passing through the “citizen factory” of formal schooling as a means of Indigenous assimilation and racialized class mobility through professionalization. Antonia’s illiteracy, by contrast, indexes a rawer form of Indigeneity within the racial regime of mestizaje. Yet Casimira does so while emphasizing their shared markers of Indigeneity, namely the pollera skirt. In my own interview with Antonia, she told me, “I studied [with Herbalife] to have success, not to be an empleada,” deploying a word that carries the double meaning of salaried employee and domestic worker, a position frequently held by women de pollera.

Miriam, who also dresses de pollera, told me that in contrast to how women like Antonia, Casimira, and herself are devalued in Bolivian society, in Herbalife, “The more you are a single mother who triumphs, the more valued you are by the people in Herbalife—by the presidents and millionaires.” Miriam further explained: “Because in Herbalife,” she continued, “you are valued for your points.” Miriam acknowledged the power of crafting a narrative arc that leads from financial struggle to the “financial independence” that MLMs tout, and insisted that she had finally found a place where she had value.[28] Miriam frames Herbalife’s point system (which reflect sales, the purchases of bulk product, and points bought to help oneself advance) not as a relentless mechanism of neoliberal audit culture (Shore and Wright 2015), but rather, a value system that allows her to embrace her identity as a struggling single mom and an Indigenous woman de pollera as a badge of honour.

While Miriam feels demeaned for so many reasons—for being, in her words, an uneducated, Indigenous woman, a single mother who is in debt—Herbalife sees her true potential. For Miriam, those points index her strengths as a sales woman, as a recruiter, someone who has overcome shyness and a lack of self-worth to now confidently present on Herbalife stages. These are, for Miriam, meaningful experiences of asserting her dignity, her worth, and of cultivating a good life that is rooted in a sense of being valued and respected.

Coupled with Casimira’s account of the centrality of testimonial narratives for recruitment, however, both women demonstrate that this value system is not colour blind as the language of disembodied points would suggest, but rather one predicated on multifaceted modes of racialization. That is, their value to the company is not in spite of their Indigeneity—that fantasy of the de-racialized point system—but rather because of it. As Casimira’s account of her Facebook friend and trip to Colombia makes clear, the visual signs of Indigeneity are hot property for selfies because of how they can be folded into a narrative arc about Herbalife’s racial transcendence and a claim to truth in advertising contra the “lies” of formal education and professionalization—those historical benchmarks of superación, Indigenous assimilation, or whitening.

Their efficacy serves multiple audiences. In Bolivia, Casimira, Miriam, and Antonia can point to their experiences of racial discrimination and Herbalife as a means of superando (overcoming) that devaluation to address and recruit others for whom such narratives resonate deeply. But that racialized bootstrapping story circulates beyond Bolivia as their racially marked bodies enter the testimonies and photo montages of recruiters who can point to their success as evidence of the company’s ability to generate wealth, even for “illiterate,” dark-skinned, and colourfully-dressed Indigenous women like Antonia. If these poor, illiterate, Indigenous women in Bolivia can do it, so can you, in Miami or Medellín.

Bolivian sociologist Rivera Cusicanqui coined the phrase Indio Permitido (the permissible Indigenous person), later popularized by Hale (2005), to capture a domesticated version of Indigeneity that gained traction in Bolivia under neoliberalism.[29] Herbalife, in many ways, presents us with yet another iteration of neoliberal multiculturalism, one in which folkloric expressions of Indigeneity are welcome, celebrated, materialized in the bowler hat and pollera, and narrativized in testimonials of struggle rooted in racial exclusion that circulate on social media platforms and in slide decks during recruitment events. Here, Indigeneity’s appearance as both the colourful and devalued Other is integral to telling a redemption story that positions the company as a more promising vehicle of inclusion and dignity.

The terms of Miriam’s inclusion in such a system, however, are predicated on both her suffering and her capacity to overcome it—or at least appear to do so.[30] Left out of Miriam’s positive account of her experience of this mode of inclusion is the fact that accumulating and then maintaining value in your points is incredibly hard work, and that advancing levels often requires purchasing bulk product or “points” directly to meet requisite benchmarks. Doing so will allow Miriam—and her benefiting uplines—to remain safely on their rungs (without the danger of finding their monthly checks slashed).

The cost of that investment, however, may be steep. Casimira’s children, for example, have quietly lamented to me about her decision to sell off property she owned in the countryside and dip into her teacher’s pension to keep herself on her level. Such scrambling efforts, however, pose a real risk of accumulating unsurmountable debts as distributors liquefy their savings and other investments for a product many find themselves later struggling to offload.

Conclusion

MLM success in El Alto owes much to recruitment strategies rooted in telling truths that resonate with many people struggling with the terms of racialized class mobility, the racialized forms of superación promised through becoming, for example, “a professional.” Recruiters herald MLMs as an equally-accessible business opportunity—a rhetorical move that conveniently glosses over the extensive start-up costs of joining most MLMs and the challenges of remaining on your level once you get there. Remaining on that rung requires financial investment in product and sometimes infrastructure (for example, renting space for a club). It also requires investing time and money into honing one’s compelling testimonial narrative at recruitment events that charge entrance fees. MLMs thus engage in their own variation of racial capitalism by extracting value from Indigenous distributors whose lived stories of racial discrimination operate as downline recruitment tools.

Yet I want to caution against the idea that Casimira, Miriam, Luís, and Plácido are merely dupes or crass manipulators cynically recruiting people into their downlines despite the emptiness of many of those promises in practice. Instead, I want to take seriously their disappointments in the promises of racialized-class mobility and the longing it reveals. Part of the allure of MLM discourses around “compassionate capitalism” has been its rhetorical appeals to horizontal relations, mentoring between uplines and downlines, and non-competitive social advancement—ironically, of course, offered in the shape of a pyramid.

In Casimira’s account of Herbalife’s promise of shared mobility, ascension within the company is not a private affair. Rather, the very structure of networked sales promotes the idea she and her downlines—often cast in the familiar terms of children and grandchildren, but also accomplished, quite literally, by recruiting and incorporating friends, biological relatives, and fictive kin—will enjoy the fruits of attending the “University of Success,” and will be able to “move up levels together,” as she intoned at the end of her recruitment pitch. Her own uplines assured that, too. Much like the classic notion of superación as a collective will to improve, this turn of phrase centres on the aspiration to shared mobility, casting Herbalife’s pledge of economic uplift in the moralized and, in the Andes, racialized terms of a relational advancement. Bootstrapping, in this narrative, is done collectively. It is that desire to move up levels—but to do so together—that can easily be mobilized as a sales pitch, but gains traction in part because of the possibility of solidarity it promises new recruits.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

Thank you to my Bolivian interlocutors who have shared both their hopeful striving for a more just and dignified life and their critical reflections on the difficulties they face in so doing. I am grateful to Natali Valdez, Eve Zimmerman and the 2022–2023 Fellows of Wellesley College’s Suzy Newhouse Center for the Humanities, and Brown Anthropology’s Colloquium Series organizers and participants for their insightful comments on an earlier version of this work. Research was made possible by the National Science Foundation, American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS), and National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) International and Area Studies Fellowships. Thanks, always, to my forever writing buddy, Andrea Flores.

Notes

-

[1]

All names are pseudonyms.

-

[2]

Barragán 2009; Shakow 2014

-

[3]

See Chuquimia et al. 2007; Torrico Foronda 2017

-

[4]

“Mestizo” refers to people of mixed Indigenous and European (Spanish) ancestry.

-

[5]

Canessa 2012; De La Torre Ávila 2006; Maclean 2018; Rance 2018; Tassi et al 2013; Tassi 2017.

-

[6]

Pfeifer 2013.

-

[7]

Goldstein and Stevenson 2016.

-

[8]

In his study of the Mexican MLM, Omnilife Cahn (2011) argues that the recent literature on neoliberalism in Latin America centres on those who resist it while failing to take seriously why the neoliberal rhetoric enshrined in MLM discourses might resonate with the millions of people joining the ranks of direct sales. See also, Antrosio 2012; Bartel 2021; Burch 2015; Cox 2018; de Casanova 2011; Mondom 2019.

-

[9]

Mondom’s (2019) Amway study, for example, examines how the Dutch Calvinism of co-founder Richard DeVos shaped his formulation of “compassionate capitalism” as a critique of postwar corporate greed, promising more meaningful work rooted in self-help ideologies popular at the time. In Colombia, Bartel (2021, 5) argues that, in the “throes of financializing capitalism” and amid ongoing armed conflict, Christian prosperity and MLM gospels “provide rubrics of aspiration, agency, and survival for individuals who otherwise have little control over their lives.”

-

[10]

Herbalife reports 38,000 distributors in the country of approximately 10 million with 14 percent of its sales occurring in El Alto—2 percent more than in neighbouring La Paz (El Deber, 2019).

-

[11]

Elsewhere I discuss the invocation of buen vivir (good living). See Lyall et al. (2018) on this ubiquitous concept in Ecuador.

-

[12]

For examples of the vast literature in conversation with Robinson’s (2020) theorizing of racial capitalism, see Estes, Gilmore, and Loperena 2021; Kelly 2017; Melamed 2015.

-

[13]

See García 2006; Leinaweaver 2008; Luykx 1996; Shakow 2014

-

[14]

Thinking with Indianist intellectual Carlos Macusaya.

-

[15]

García 2005; Leinaweaver 2008; Luykx 1996; Shakow 2014

-

[16]

Only one of Casimira’s daughters continues wearing the pollera skirt like her mother, while her other daughters dress in traje.

-

[17]

Even as sceptics raised questions about the authenticity or performativity of pollera-wearing bureaucrats.

-

[18]

These rhetorical tropes are common across MLMs—circulating widely in motivational tapes, pamphlets and videos shared on social media platforms. New Herbalife distributors learn to pattern their testimonials and business pitches according to these tested scripts while integrating personal life histories and locally meaningful references.

-

[19]

On MLMs and middle-class respectability in Mexico, see Cahn 2008, 441. See also Bartel 2021.

-

[20]

See Ravindran (2021) for examples of pigmentocracy in practice in the Alteño labour market.

-

[21]

Unfortunately, space doesn’t allow me to deal fully with the imbrications of the broader popular economy and racial capitalism here; however I aim to shed light on the ways MLMs are part of extraction rooted in racial partitioning.

-

[22]

Elsewhere, I explore the intersection between locally meaningful concepts like having a “casera” (established vendor-consumer relationship), experiencing “competencia desleal” (bad faith dealings in the market) accusations of being “celoso” (envy), and confronting “derecho de piso” (slang for skinning/a shake-down or normalized modes of everyday extortion). In these and other ways, MLMs are entangled with the logics, idioms, and institutional practices (such as gremios/unions) operating in Bolivia’s so-called popular economy.

-

[23]

Plácido uses sindicato (union) instead of gremio (guild).

-

[24]

See Guaygua 2003; Maclean 2018; Rea Campos 2016 (“new commercial Aymara petite bourgeoisie”); Salazar et al. 2012 (Proto-bourgoiousie); Shakow 2014; Rance 2018.

-

[25]

See, for example, Babb 2010; Ødegaard 2016; Weismantel 2001.

-

[26]

Dolan and Johnstone-Louis 2011; Lan 2003; Wilson 1999; 2004; Jenner Furst & Julia Willoughby, 2021.

-

[27]

Haynes 2013.

-

[28]

Elsewhere I examine the networked surveillance operative in direct sales through this point system.

-

[29]

Tassi et al. argue that neoliberal reforms extended earlier civilizing projects but “emphasized identity claims at the expense of claims for a more equitable redistribution” (2013, 3).

-

[30]

As I discuss elsewhere, those who cannot overcome such suffering, who struggle in the company and ultimately turn away from it, become liabilities to be disavowed.

Bibliography

- Antrosio, Jason. 2012. “Peasants and Pirámides: Consumer Fantasies in the Colombian Andes.” In Consumer Culture in Latin America, edited by John Sinclair and Anna Cristina Pertierra, 81–90. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Babb, Florence. 2010. Between Field and Cooking Pot: The Political Economy of Marketwomen in Peru. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Barragán, Rossana. 2009. “Organización del trabajo y representaciones de clase y etnicidad en el comercio callejero de la ciudad de La Paz” [“The Organization of Work and Representations of Class and Ethnicity in Street Commerce in the City of La Paz”]. In Estudios urbanos: En la encrucijada de la interdisciplinaridad, edited by Fernanda Wanderley, 207–242. La Paz: Plural.

- Bartel, Rebecca. 2021. Card-Carrying Christians: Debt and the Making of Free Market Spirituality in Colombia. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Burch, Jessica. 2016. “‘Soap and hope’: Direct Sales and the Culture of Work and Capitalism in Postwar America.” Enterprise & Society 17 (4): 741–751. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26568055.

- Cahn, Peter. 2011. Direct Sales and Direct Faith in Latin America. New York: Palgrave.

- Cahn, Peter. 2006. “Building Down and Dreaming Up.” American Ethnologist 33 (1): 126–142. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.2006.33.1.126.

- Canessa, Andrew. 2012. Intimate Indigeneities: Race, Sex, and History in the Small Spaces of Andean Life. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Castellanos, M. Bianet. 2020. Indigenous dispossession: Housing and Maya Indebtedness in Mexico. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Chuquimia, Jaime Durán, Verónica Karen Arias Díaz, and Gustavo Marcelo Rodríguez Cáceres. 2007. Casa aunque en la punta del cerro: vivienda y desarrollo de la ciudad de El Alto [A House Even at the Top of the Hill: Housing and Development of the City of El Alto]. La Paz: Fundacion Pieb.

- Cox, John. 2018. Fast Money Schemes: Hope and Deception in Papua New Guinea. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- de Casanova, Erynn Masi. 2011. Making Up the Difference: Women, Beauty, and Direct Selling in Ecuador. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- De la Torre Ávila, Leonardo. 2015. No llores, prenda, pronto volveré: Migración, movilidad social, herida familiar y desarrollo [Don’t Cry, Promise, I’ll be Back Soon: Migration, Social Mobility, Family Wounds and Development]. La Paz: Institut français d’études andines.

- Dolan, Catherine, and Mary Johnstone-Louis. 2011. “Re-siting Corporate Responsibility: The Making of South Africa’s Avon Entrepreneurs.” Focaal 60: 21–33. https://doi.org/10.3167/fcl.2011.600103.

- El Deber. 2019. “Ricardo Mendoza: ‘Llevamos en alto la visión de hacer un mundo más saludable’” El Deber, 28 April. https://eldeber.com.bo/economia/ricardo-mendoza-llevamos-en-alto-la-vision-de-hacer-un-mundo-mas-saludable_139540 (accessed 3 March 2023).

- Estes, Nick, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, and Christopher Loperena. 2021. “United in Struggle: As Racial Capitalism Rages, Movements for Indigenous Sovereignty and Abolition Offer Visions of Freedom on Stolen Land.” NACLA Report on the Americas 53 (3): 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/10714839.2021.1961444.

- García, María Elena. 2005. Making Indigenous Citizens: Identities, Education, and Multicultural Development in Peru. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Goldstein, Daniel. 2016. Owners of the Sidewalk: Security and Survival in the Informal City. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Goldstein, Matthew and Alexandra Stevenson. 2016. “Herbalife Settlement With F.T.C. Ends Billionaires’ Battle.” The New York Times, 15 July. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/16/business/dealbook/herbalife-ftc-inquiry-settlement-william-ackman.html (accessed 3 March 2023).

- Guaygua, Germán. 2003. “La fiesta del Gran Poder: el escenario de construcción de identidades urbanas en la ciudad de La Paz, Bolivia.” [“The Celebration of the Great Power: the Scenario of Construction of Urban Identities in the City of La Paz, Bolivia”]. Temas Sociales: 171–184.

- Hale, Charles. 2005. “Neoliberal multiculturalism: The remaking of cultural rights and racial dominance in Central America.” PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review (28) 1: 10–28. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24497680

- Haynes, Nell. 2013. “Global cholas: Reworking tradition and modernity in Bolivian Lucha Libre.” The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 18 (3): 432-446. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlca.12040

- Kelley, Robin DG. 2017. “What did Cedric Robinson mean by racial capitalism?” Boston Review, January 12. https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/robin-d-g-kelley-introduction-race-capitalism-justice/#:~:text=Capitalism%20was%20%E2%80%9Cracial%E2%80%9D%20not%20because,Gypsies%2C%20Slavs%2C%20etc. (accessed 3 March 2023)

- Lan, Pei-Chia. 2003. “Working in a Neon Cage: Bodily Labor of Cosmetics Saleswomen in Taiwan.” Feminist Studies 29 (1): 21–45. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3178467.

- Leinaweaver, Jessaca. 2008. “Improving oneself: young people getting ahead in the Peruvian Andes.” Latin American Perspectives 35 (4): 60–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X08318979.

- Furst, Jenner, and Julia Willoughby. 2021. LuLaRich. Culver City: Amazon studios.

- Luykx, Aurolyn. 1996. “From Indios to Profesionales: Stereotypes and Student Resistance,” In The Cultural Production of the Educated Person: Critical Ethnographies of Schooling and Local Practice, edited by Lois Weis, 239-272. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Lyall, Angus, Rudi Colloredo-Mansfeld, and Malena Rousseau. 2018. “Development, citizenship, and everyday appropriations of buen vivir: Ecuadorian engagement with the changing rhetoric of improvement.” Bulletin of Latin American Research 37 (4): 403–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/blar.12742.

- Maclean, Kate. 2018. “Envisioning Gender, Indigeneity and Urban Change: The Case of La Paz, Bolivia.” Gender, Place & Culture 25 (5): 711–726. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1460327.

- McKittrick, Katherine. 2006. Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Melamed, Jodi. 2015. “Racial Capitalism.” Critical Ethnic Studies 1 (1): 76–85. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/jcritethnstud.1.1.0076.

- Mondom, Davor. 2018. “Compassionate Capitalism: Amway and the Role of Small-business Conservatives in the New Right.” Modern American History 1 (3): 343–361. https://doi.org/10.1017/mah.2018.37.

- Müller, Juliane. 2018. “Andean–Pacific Commerce and Credit: Bolivian Traders, Asian Migrant Businesses, and International Manufacturers in the Regional Economy.” The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 23 (1): 18–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlca.12328.

- Müller, Juliane. 2019. “Transient trade and the distribution of infrastructural knowledge: Bolivians in China.” Transitions: Journal of Transient Migration 3 (1): 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1386/tjtm.3.1.15_1.

- Müller, Juliane, and Rudi Colloredo-Mansfeld. 2018. “Introduction: Popular economies and the remaking of China-Latin America relations.” Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology. 23 (1): 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlca.12339.

- Ødegaard, Cecilie Vindal. 2016. Mobility, Markets and Indigenous Socialities: Contemporary Migration in the Peruvian Andes. London: Routledge.

- Pfeifer, Stuart. 2013. “Latinos Crucial to Herbalife’s Financial Health.” Los Angeles Times, February 15. https://www.latimes.com/business/la-xpm-2013-feb-15-la-fi-herbalife-latino-20130216-story.html (accessed 3 March 2023).

- Radhakrishnan, Smitha. 2001. Making Women Pay: Microfinance in Urban India. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Rance, Amaru Villanueva. 2020. “Bolivia: la clase media imaginada” [“Bolivia: The Imagined Middle Class”]. Nueva Sociedad 285: 122–138.

- Ravindran, Tathagatan. 2021. “The Power of Phenotype: Toward an Ethnography of Pigmentocracy in Andean Bolivia.” The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 26(2): 219–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/jlca.12551.

- Rea Campos, Carmen Rosa. 2016. “Complementando racionalidades: la nueva pequeña burguesía aymara en Bolivia” [Complementing Rationalities: The New Aymara Petty Bourgeoisie in Bolivia]. Revista mexicana de sociología 78 (3): 375–407. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309097168_Complementando_racionalidades_ La_nueva_pequena_burguesia_aymara_en_Bolivia

- Robinson, Cedric J. 2020. Black Marxism, Revised and Updated Third Edition: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. Chapel Hill: UNC Press Books.

- Salazar de la Torre, Cecilia, Juan Mirko Rodríguez Franco, and Ana Evi Sulcata Guzmán. 2012. “Intelectuales aymaras y nuevas mayorías mestizas. Una perspectiva post 1952.” [Aymara Intellectuals and New Mestizo Majorities. A Post-1952 Perspective]. Informes de Investigación. La Paz: Programa de Investigacón Estratégica en Bolivia (PIEB). https://fundacion-rama.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/6003.-Intelectuales-aymaras-y-nuevas-mayorias-mestizas-%E2%80%A6-Salazar.pdf

- Shakow, Miriam. 2014. Along the Bolivian Highway: Social Mobility and Political Culture in a New Middle Class. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Shore, Cris, and Susan Wright. 2015. “Audit Culture Revisited: Rankings, Ratings, and the Reassembling of Society.” Current Anthropology 56 (3): 421–444. https://doi.org/10.1086/681534.

- Tassi, Nico, Carmen Medeiros, Antonio Rodríguez-Carmona, and Giovana Ferrufino. 2013. “Hacer plata sin plata”: El desborde de los comerciantes populares en Bolivia [Making Money without Money: The Overflow of Popular Merchants in Bolivia]. La Paz: Programa de Investigacón Estratégica en Bolivia (PIEB). https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?pid=S0301-70362016000200192&script=sci_arttext_plus&tlng=es

- Tassi, Nico. 2017. The Native World-system: An Ethnography of Bolivian Aymara Traders in the Global Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Torrico, Escarley. 2017. Emergencia Urbana: Urbanización y libre mercado en Bolivia. [Urban Emergency: Urbanization and The Free Market in Bolivia]. La Paz: CEDIB.

- Weismantel, Mary. 2001. Cholas and Pishtacos: Stories of Race and Sex in the Andes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Wilson, Ara. 1999. “The Empire of Direct Sales and the Making of Thai Entrepreneurs.” Critique of Anthropology 19 (4): 401422. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X9901900406.

Liste des figures

Figure 1