Résumés

Abstract

Informed by eighteen months of ethnographic fieldwork in Montmartre, one of the last village-like neighbourhoods in Paris, in this paper, I analyze how people in this community talked through and acted out the COVID-19 pandemic. Using theoretical frameworks from linguistic, cognitive and medical anthropology, I examine “small stories” (Georgakopoulou 2007) about COVID-19, in particular, the analogical and conceptual aspects of this talk. How do people construct understandings of crisis as it evolves? What does this process look like when talk becomes action and reaction and what does it say about the future?

This paper explores how people employed analogy, cultural scripts and other linguistic wor(l)d-building tools in their talk about their experiences and comprehensions of COVID-19. Following the arguments of Ochs (2012), I propose that talking about COVID-19 is itself an experience of the virus, an experience that informs people’s understandings of their present circumstances and future possibilities.

Keywords:

- COVID-19,

- human futures,

- sense-making,

- linguistic anthropology,

- medical anthropology

Résumé

À partir de dix-huit mois de travail ethnographique sur le terrain à Montmartre, l’un des derniers quartiers de Paris ressemblant à un village, j’analyse dans cet article la manière dont les membres de cette communauté ont parlé de la pandémie de COVID-19 et l’ont mise en scène. En utilisant des cadres théoriques issus de l’anthropologie linguistique, cognitive et médicale, j’examine les « petites histoires » (Georgakopoulou 2007) sur la COVID-19, en particulier les aspects analogiques et conceptuels de ce discours. Comment les gens construisent-ils leur compréhension de la crise au fur et à mesure qu’elle évolue ? À quoi ressemble ce processus lorsque le discours se transforme en action et en réaction, et qu’est-ce que cela dit de l’avenir ?

Cet article explore la manière dont les gens ont utilisé l’analogie, les scripts culturels et d’autres outils linguistiques de construction du travail dans leur discours sur leurs expériences et leur compréhension de la COVID-19. Suivant les arguments d’Ochs (2012), je propose de parler de la COVID-19 comme d’un fait qui constitue en soi une expérience du virus, une expérience de la maladie.

Mots-clés :

- COVID-19,

- avenirs humains,

- création de sens,

- anthropologie linguistique,

- anthropologie médicale

Corps de l’article

Introduction

The ninth of June 2023 will mark the second anniversary of the removal of national restrictions on travel and other “sanitary measures”—notably mandated masks in public spaces, affidavits for permission to leave one’s home or region, and widespread closings of businesses and public services. From March to June 2020, everyone in France (excluding “essential workers”) was confined to their domicile and permitted one hour outside, within a one-kilometre radius, per day, for a government-approved “necessary reason,” such as going to the grocery store or pharmacy. To leave one’s home, a signed affidavit was required as well as a piece of identification. In Paris, these documents were checked by police deployed to enforce the confinement. These restrictions mandated when, where, and how people could (or must) use their bodies in social spaces. This confinement went through multiple versions, mandating varied restrictions on travel and movement until 9 June 2021.

In France, studies of the widespread effects of the COVID19 pandemic, and the human experience of this pandemic abound (such as “Logement et conditions de vie” by the Institut national des études démographiques; “Epicov[1]” by the Institut national de la santé et la recherche médicale). Nonetheless, existing quantitative research lacks complementary qualitative studies of the pandemic to enrich our understanding of the effects of this crisis now and in the future. This research provides ethnographic data about people’s experiences, comprehensions of and reactions to the pandemic, in particular those reactions that affect people’s sociability and use of social space. The results of this study indicate how people’s understandings of and stories about their experience and their future are informed, even during a supposedly unprecedented crisis, by existing cultural scripts.

I adopt Roitman’s (2012) perspective on “crisis” as a “starting point for narration…an enabling blind spot for the production of knowledge.” Roitman proposes that during crises historical events are set apart, signified, and become recognizable. Crises allow us to ask questions and, much like the analogies we use to understand them, obfuscate certain elements of experience while highlighting others. Most importantly to this research, crises signal the necessity of storytelling to human sense-making.

In this corpus, people’s understandings are often scaffolded onto pre-existing cultural scripts or analogies with the past (Hofstadter and Sander 2010). Understandings of COVID-19, confinement, and a post-COVID future are framed by cultural scripts, such as the script for the plague in Europe, and ideologies, particularly techno-optimism. In this paper, I focus on how cultural scripts for cleanliness, pollution, and the foreign Other and (a pessimistic) techno-optimism frame the experiences of my interlocutors of the global health crisis and their ability to move forward into the future.

Ethnographic Context

In this paper, I present an analysis of individual experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic in Montmartre, a neighbourhood in the 18th arrondissement of Paris, over 18 months (March 2020–August 2021). Data was collected from daily participation in the community, participant observation, and semi-structured interviews. All informants were linked to Montmartre, primarily through living or working there. They were from a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds and living diverse economic realities at the time of the research.

Made famous by its bohemian starving artists, today, real estate prices in Montmartre ensure that the majority of the neighbourhood falls into the middle or upper class. There is a distinct lack of ethnic and economic diversity within the neighbourhood and little immigrant presence, whereas the surrounding areas (except for the 9th arrondissement to the south) have markedly lower real estate prices and possess significant African and Asian immigrant populations. Most participants were salaried employees, were able to work remotely, or received government aid and did not experience intense economic hardship during the pandemic. Nonetheless, several participants did face challenges such as losing their apartments, jobs, or being unable to earn income during lockdowns.

Participants were between 23 and 78 years of age, roughly equal men and women, francophone, and confined in Paris (primarily Montmartre) in 2020. Despite their varied vocations and economic class, two dominant themes were ubiquitous in everyone’s discussion: foreign plague and pollution and European cleanliness and “reason” (for example, knowledge, science). These themes of pollution and reason could be partially attributed to discourses in the media concerning COVID-19. However, as my analysis demonstrates, these thematic threads precede COVID-19 and are linked to larger cultural scripts present in Paris.

Local inquiry, such as participant observation in Montmartre, of how people cope with a crisis can prove highly relevant, as localized experience in a highly globalized world is, in many ways, representative of what other people in other places experience during the same period of crisis. This research demonstrates how novel situations, such as crises, are interpreted and reacted to by groups according to pre-existing cultural scripts and ideologies. This sense-making process informs (re)actions with past biases and reproduces the latter. Pre-existing social woes (such as racism and homophobia) were deployed to interpret the pandemic and weave it into a larger conglomeration of tensions that have plagued France for centuries. Montmartre provided a microcosm of a modern, urban, European community where, no matter the amount of new, scientific facts that became available, past cognitive models and cultural texts remained more prevalent in talk and action than new behaviours based on new information.

Montmartre is a distinct neighbourhood within Paris. Residents consider it a “village” separate from the capital and, historically, it was. Montmartre was an independent commune that was annexed into Paris in 1860. The République de Montmartre has its institutions, events, and local celebrities and retains an independent spirit vis-a-vis the rest of the city.

The mentality of a “quartier populaire” in Montmartre manifests itself in the social lives of residents and is reinforced by the neighbourhood’s architecture. Montmartre was largely left untouched by Parisian urbanism, notably the massive architectural projects accomplished in the Haussmannien period (1853–70). The wide boulevards and spacious buildings Haussmann built were not constructed in Montmartre because of a quarry located under the hill. Montmartre retains its narrow, cobblestone streets and its older houses and apartments are very close together and often face one another.

Illustration 1

As there is no useful way to define a “parisien” or a “montmartrois,” I do not use these denominations. My interlocutors and I shared the same space at a singular moment in which residents were essentially the only people in Paris (an unprecedented phenomenon in a city with approximately two million residents that is flooded daily by up to ten million people from the suburbs, in addition to tourists). I moved to Montmartre in 2016 and remained there throughout confinement. Emptied of outsiders and those who could escape their small apartments for the countryside, the social and physical proximity of Montmartre was amplified.

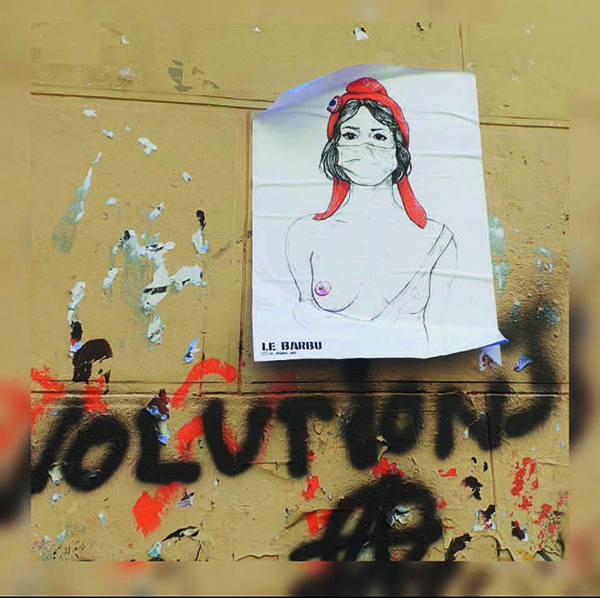

Though physical and spontaneous interactions were limited, the absence of informal face-to-face social exchanges did not equate to the absence of symbolic and linguistic expression in our shared social space. Public culture, “the envelope of communication practices within which public opinion is formed” (Hariman 2016), was not suppressed by the prohibition of pre-COVID social practices and interactions. In Montmartre, a neighbourhood with an active graffiti culture that boasts the work of well-known artists (such as Miss.Tic), graffiti, street art, and stamped messages on the pavement attested to people’s experiences and comprehensions of confinement, sanitary measures and, later, vaccination. These messages often received responses from others, resulting in a dynamic negotiation of the reality of COVID within the neighbourhood. These outdoor communications reflect both the community of Montmartre and Parisian outdoor culture. Given the price per square foot in Paris, Parisians spend their lives outdoors—exercising, eating, relaxing, reading, and protesting in the city’s open spaces. Even when confined, the city’s outdoor culture persisted.

Illustration 2

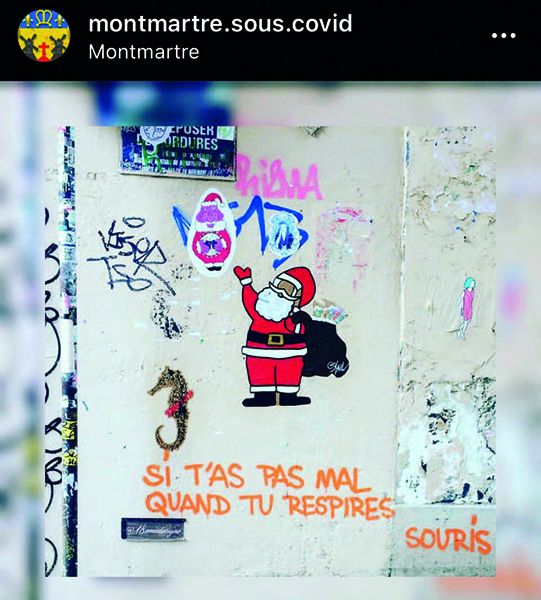

I sought out this discourse, photographing it, and soliciting others to share pictures of their findings. This exchange gave me the idea to create a digital space for this data. I created an Instagram account: @montmartre.sous.covid. The account has 114 followers and continues to function as a space in which people can share their experiences. This space allowed different kinds of interactions with people, specifically, interactions in which they approached me to engage with the research.

Participant Observation and Collection of Linguistic and Symbolic Data

My participant observation is based on Ochs’s (2012, 152) perspective of utterances or “ordinary enactments of language” as “modes of experiencing the world.” I understand talk as an experience of the pandemic and possible post-pandemic worlds, not only a description of these. Talking about COVID19 is a personal and social creation of “unfolding meaning” in which “significance is built through and experienced in…bursts of sense-making, often in coordination with others” (Ochs 2012, 152). I take into account how people speak from a linguistic point of view while paying particular attention to conceptual elements in their talk.

Illustration 3

In addition to talking with people informally, I conducted semi-structured interviews. Interviews occurred in natural contexts; ordinary conversations in an atmosphere where COVID19 was already a constant topic and in places where people felt comfortable. Small group interviews developed organically, with couples, roommates, or neighbours. In these interactions, I aligned myself with practices as they were happening in the community and with the preferences of the people with whom I engaged.

Discussions with participants were two-way interactions in which I shared and compared our experiences. The majority of interviews were conducted with people with whom I had relationships before COVID-19, people who freely expressed their opinions and shared personal information with me. The data in this research represents ordinary talk in Montmartre during the pandemic: gossip, inappropriate jokes, and all. Throughout the research, people repeatedly described the positive, cathartic experience of talking about what was happening. They reflected upon how talking about our new lives helped confront this reality, make it comprehensible, and, often most importantly, especially during the isolation of confinement, make this reality shared.

I took the approach of creating stories about COVID-19 with participants, asking questions following the temporal order of the crisis: what COVID-19 is, where it came from, why it appeared, who is involved, when it began, and when it will end. This technique precipitated conversations in which informants constructed “small stories” (Georgakopoulou 2007) about COVID-19. These interactions were shared sense-making practices in which we not only talked about the crisis we were experiencing but experienced it in new ways by interpreting and embedding these experiences into stories and existing cultural scripts.

Analysis: Storytelling, Sense-Making and Crisis

COVID-19 stories and talk are not simply symbolic forms; they are constructive practices that constitute the objects and worlds of which people speak. These stories allow for the identification of mental schemas at work in people’s sense-making of their experience as well as source domains of knowledge they employ to comprehend new phenomena and information. Using methods to analyze the use of talk to understand illness and disease (Good 1994; Masquelier 1993), I identified dominant themes (notably that of “foreign plague” and of European “reason” and cleanliness) in the stories people created and then enacted in their experiences of COVID19.

Experts and Uncertainty

In my corpus of interview transcriptions, people’s talk reflects many of the same elements of techno-scientific optimism, or the belief that medical knowledge and technology will solve complex human problems, that Black (2021a; 2021b) describes in his research on health storytelling. Though speculations that science itself caused the pandemic were rife, it was rare for someone to not express faith in some form of knowledge perceived as scientific or expert. The salvific role of science and medicine was consistent throughout the data, whether people ascribed to or were skeptical of official narratives or promoted counter-narratives of COVID-19.

Though people regularly deployed science as the probable saviour from the pandemic, this optimistic view of science is hardly absolute in their stories. The “optimistic” part of techno-scientific optimism was compromised by the entanglements of science with wider political and capitalist agendas. Science and medicine were inextricable from questions of political power, economic interests, and a destabilization of scientific credibility as experts with opposing arguments paraded non-stop in national media.

In France, COVID-19 exacerbated an already volatile sociopolitical situation that culminated in January 2020 with the longest transportation strike in French history. The “gilets jaunes” (“yellow vest” referring to the yellow vests worn by protesters) movement, which began in November 2018, created a snowball effect, melding diverse social woes into kilometres of dissent as protesters opposed issues from pension reforms to taxation to gas prices. The expansion of the #MeToo movement in 2017 (manifested in France as #BalanceTonPorc - “denounce your pig”) and the Black Lives Matter movement in 2020 further fueled a context of dissatisfaction and mistrust. These grassroots populist movements were countered by growing nationalism, increasing racism and xenophobia, and the popularization (and unprecedented electoral success) of the Front national (re-branded as the Rassemblement national in 2018), a neo-nationalist political party established in the 1970s that was irrelevant in French politics until the last few decades. The uncertainty and sense of crisis that accompanied COVID-19 escalated mounting unrest in French society and deepened citizens’ lack of trust in the French government.

The COVID-19 pandemic wedded socioeconomic and political uncertainty to the destabilization of scientific credibility. Nevertheless, how close information was to so-called “expert” knowledge was a compulsory component of COVID-19 talk. In people’s talk, the hierarchy of expertise was fairly predictable. Information from medical experts was deemed as most important. Expert information was followed by personal connections through which people obtained expert information. Official government discourses came last; as time passed, most of my respondents confessed to no longer watching them.

The source of information was as important as the information itself in terms of perceived legitimacy. Social media was the most frequent source people referenced, though, as the examples below demonstrate, they tried to link information from social media to an expert. Social media was followed (in order of frequency) by television stations (TF1, France Info), and newspapers (France Press, L’Express, Le Figaro and 20 Minutes). BFMTV, France’s most-watched news channel, was the most frequently referenced; however, the majority of my interlocutors described it as a prime example of contradictory or false information, discussing how panels of so-called experts changed by the minute and prescribed opposing measures.

People claiming to be experts in the media were not the sole purveyors of contradictory information. For 18 months, France endured repeated contradictions from government officials claiming expertise (who, for example, announced masks were unnecessary in March 2020 only to require them nationally three months later) as well as those in major research institutions. The phenomenon incited by Didier Raoult in 2020, specialist of infectious disease at the Faculté des Sciences Médicales et Paramédicales de Marseille and the Institut Hospitalo-Universitaire Méditerranée Infection, is a telling example of how information perceived as “scientific” cleaved comprehensions and behaviours in France. As André, a seventy-two-year-old professor emeritus of film, described,

Il [Raoult] a généré…un espèce de…d’idolâtrie, littéralement, on peut parler de ça, sur les réseaux sociaux parce qu’il y a eu plusieurs centaines de milliers de followers sur certains médias et il a beaucoup été médiatisé…et donc ça contribuait à nourrir…la défiance vis-à-vis du corps médical en général et du pouvoir public, aussi des laboratoires, les fameuses Big Pharma, pour générer beaucoup de conspirationnistes qui ont été voilà nourris.[2] (Translations for all interview quotes can be found in the Endnotes.)

The controversy following Dr. Raoult’s March 2020 claim of having found a cure for COVID is a stunning demonstration of the destabilization of multiple forms of social credibility. Immediately after his announcement, doctors questioned Raoult’s results. The Minister of Health called for further testing and subsequent studies disproved his claim. André, a vocal Socialist party supporter, details how the Raoult polemic, as he put it, “nourished mistrust” in medical experts, political figures, and research laboratories. Many Raoult supporters very literally idolized him (in Marseille prayer candles sporting his photo were sold), condemning the corruption of the French state. Those who were anti-Raoult denounced the corruption of French universities and research institutions. These opposing opinions erupted as gossip, disputes, and alienation of individuals in the community either because a person was perceived as a conspiracy theorist or because they were perceived as “‘naively” trusting the French government.

Montmartre has that small-town characteristic of everyone knowing (or thinking they know) about everyone. This intensified when few people were working, and no one could come in or go out of a one-kilometre radius of the neighbourhood. Divisions within the community based on the extent to which an individual behaved according to official or alternative discourses became palpable and were acted out openly. “Sanitary citizens” (Briggs 2002), or those individuals who conceive of the body and disease in terms of medical epistemologies, adopt hygienic practices and believe in the absolute power of medical professionals, ostracized those they considered unsanitary (Brigg’s “unsanitary subjects” or those who have failed to internalize medical epistemologies) and vice versa.

These divisions were not always clearly demarcated by political stance, socioeconomic positioning, or education. This was further complicated by an overflow of information from the media, and constant input from others concerning the crisis. As confinement continued and people personally experienced the pandemic, they began to prioritize interpretations of the crisis based on anecdotal experiences. Instead of repeating official discourse about the healthcare system, my seamstress talked to me about how her father died in the hospital. Everyone who had COVID discussed whether or not their symptoms corresponded to descriptions in the media. Because not everyone had the same experience of COVID, nor the same symptoms when infected, there was no consensus about what to believe and how to react.

The elements that defined COVID-19 as a “crisis” varied according to these individual positionings. Nonetheless, these positionings were frequently shored up with parascientific communications (Longhi 2022). No matter their background, economic class or political positioning, all of my informants bolstered their arguments with some form of what they determined was legitimate scientific knowledge.

Conversations were habitually peppered with references to experts, like the statement made by Julien, a sixty-seven-year-old drummer, music instructor and neighbor, “À un moment j’ai entendu un mec, très sensé, docteur, ex-médecin des armées, qui avait suggéré…” (“At one point I heard a guy, very sensible, a doctor, ex-Army doctor who suggested…”). People treasured information from family or friends who were members of the medical corps. Daphné, a fifty-one-year-old cabaret dancer who struggled for lack of work during lockdowns, and a strict enforcer of sanitary restrictions for herself and her two teenage daughters, explained how she consulted her family for information about the pandemic:

J’échangeais beaucoup, beaucoup, beaucoup avec ma famille parce qu’ils sont tous médecins. Et, un de mes frères est médecin, spécialisé en médecine de catastrophe, il travaille dans un très grand hôpital français et il est responsable du service COVID.[3]

By associating their talk with expert knowledge, my interlocutors sought to legitimize their arguments and seemed to also seek a form of certainty for themselves. These interdiscursive “constellations” (Foucault 1969, 88), or implicit/explicit relations to other discursive formations were ubiquitous in COVID-19 talk. The stratification and prioritization of expert knowledge in people’s talk reflect French linguistic and cultural ideologies about legitimate forms of discourse, namely, an Enlightenment-styled trust in reason and/or scientific practice.

This prioritization of expert knowledge was reinforced by another widespread practice: the recurrent precision by the speaker that they were not experts, as when Patricia, a forty-year-old implant from Beirut who was severely depressed through the pandemic insisted, “...d’après ce que j’en sais encore parce que je suis pas médecin…” [“…according to what I know, because I’m not a doctor.”]). The most common formulation was “Je ne suis pas [expert], donc je ne peux pas dire…” (“I’m not an [expert], so I can’t say…”) as in an admission by François, a seventy-two-year-old retired librarian, that, “Je ne suis évidemment pas du tout spécialiste, mais d’après ce que j’entends…” [“I am obviously not at all a specialist, but that’s what I’ve heard…”]).

The practice of self-identifying as a non-expert was rampant in COVID-19 talk, demonstrating the symbolic power of science for my interlocutors. Most interviewees did not have a practical or theoretical understanding of the science that informed their beliefs and subsequent practices concerning COVID-19. Rather, they ascribed to these symbolic institutions and engaged in these practices based on their understanding of and confidence in expert knowledge of their environment.

Talking the COVID-19 Pandemic: Analogies and Cultural Scripts

My interlocutors described themselves as well-informed about COVID-19. Too well-informed, many people bemoaned when describing the anxiety-inducing atmosphere created by the media. Even when wielding expert information, people’s COVID-19 talk indicates that a significant part of their sense-making of and reactions to the pandemic was not limited to scientific information but informed by past understandings that were deeply culturally informed.

Sontag (2002, 133) argues that in “the usual script for plague: the disease invariably comes from somewhere else…there is a link between imagining disease and imagining foreignness. It lies perhaps in the very concept of wrong, which is archaically identical with the non-us, the alien.” The “script for plague” that Sontag describes appears in my corpus in parallels made between disease and foreignness and between disease and immorality. “China” is a place that is well-known in my informants’ imaginaries, even if they have never been there, are unfamiliar with the nation’s history, its people, practices, and so forth. China is a place many of them associated, if only vaguely, with questionable sanitary practices, disease, and immorality.

From late 2019 to February 2020, references to China meant that the disease was far away from France; it was merely another problem in Asian countries, much like SARS. Once COVID-19 reached Europe, this discourse shifted toward generalized racism against the Chinese. The fact that Wuhan, China was the setting for their origin stories about COVID-19 was not innocuous. My discussions with people like Clémence, a forty-two-year-old Italian tourism agent, who lost her tourism job early on in the pandemic, are rich in cultural knowledge that most people assumed we shared:

Ça vient…alors, ça alors c’est très flou. C’est très flou, mais comme tout ce qui vient de Chine. *rire*

Ça viendrait de Chine, mais on sait pas exactement. Si ça vient véritablement du marché à Wuhan. C’est-à-dire, le marché de viande. Fin, moi j’ai des images, après c’était peut-être une espèce de propagande occidentale, je sais pas. Donc, je ne vais pas juger là-dessus.

Les marchés de viande sont toujours un peu particuliers dans des pays…moins aseptisés on va dire. Un peu plus populaire. Là, ça viendra soit du marché…directement de marché aux viandes de Wuhan, donc de…de là, ça viendrait de chauve-souris je crois, qui elle-même aurait le virus et pourrait le transmettre, fin, bon, voilà.[4]

Clémence made several arguments, admitting that her ideas may be informed by “a sort of western propaganda” and demonstrating her awareness of negative generalized conceptions of China in France. In her discussion of China, there are many moral judgments, notably that reliable information does not come from China and that China is not as “clean” or “sterile” as European nations.

These perceptions of China as a potential source of pollution (and dissimulation of pollution) are racialized and moralized. Douglas (1966, 140) argues that “a polluting person is always in the wrong.” In the context of COVID-19, the questionable cleanliness, for example, of a meat market, morphed into moral judgements. From hygiene or culinary practices to stereotypes and political critique, talk about China in my corpus is dense with condemnation. These comments were recurrent in everyday conversation, particularly from March to October 2020. However, racism against the Chinese in France did not appear with the pandemic (Lee 2013), it was simply exacerbated by it[5]. Cultural ideologies concerning China were active as were ideological conceptions of Europe in people’s imaginations of COVID-19. Europe represented the stronghold of cleanliness, progressivism, and democracy; echoing Sontag’s (2002, 136) argument that “part of the centuries-old conception of Europe as a privileged cultural entity is that it is a place which is colonized by lethal diseases from elsewhere.” Eighty-five percent of my interlocutors reiterated this conception in interviews and casual discussion, referencing diseases that had supposedly invaded Europe (for example, the Black Plague [five references from participants], Ebola [five references], SARS [five references] and the Spanish Flu [seven references]).

Interviewees most frequently associated COVID-19 with the AIDS epidemic (twelve references in participant discussions). Though a parallel between COVID-19 and SARS may be more sensical from an epidemiological standpoint, there are numerous conceptual parallels between stories of the AIDS epidemic told in France and people’s sense-making about COVID-19. Firstly, people understand that both viruses are zoonotic. For example, thirty-six-year-old Mikhail and sixty-year-old Arthur made jokes (in separate encounters) about interspecies intercourse, linking stories about COmVID-19 to those about AIDS:

Mikhaïl : Pendant le premier confinement, je disais à tout le monde que c’était des Chinois qui avaient baisé avec des singes et que ça avait fait la COVID. Parce qu’à l’époque, il y avait une légende en France qui disait que c’était des noirs qui avaient baisé avec des singes et ça avait fait le sida. J’essaie de le lancer pour les Chinois mais ça n’a pas marché. *rire*

Arthur : Le pangolin, qui a couché avec une chauve-souris et ils ont eu un petit COVID. *rire* Non, non…C’est comme à l’époque 80…quand on a commencé à dire, “Ouais, le virus du sida vient du singe. C’est un homosexuel qui a couché avec un singe.” Ouais. *rire* Non, je pense qu’il peut y avoir des mutations, mais c’est pas si évident que ça quoi. Donc le pangolin, on va le laisser tranquille.[6]

Jokes about sexual taboos as the origin of COVID-19 were ubiquitous. These verbal images reveal active cultural scripts concerning pollution, disease, taboo and moral judgements against “far-away” Others (Davies 1982) that were and remain, active in everyday conversation in Paris. This discourse deploys conceptions that neither Europeans, nor western behaviours are responsible for diseases, but foreigners, notably those who engage in taboo practices such as bestiality or behaviours differing from European customs such as sanitary practices.

As in the above examples, those making these jokes were primarily white, heterosexual males. People were rarely shocked by these comments, nor did they contest them. As the neighbours are not often shy with each other nor avoid disagreement, this is implicit acceptance of these categories as an acceptable jest. The homophobic, racist, and classist bases of these jokes are not particular to pandemic sociability. They demonstrate cultural ideologies in Paris applied to the COVID-19 crisis. These analogies reveal the biases of speakers related to contamination and disease operating at a macro level as frames of understanding for current events.

A second conceptual parallel between the AIDS and COVID-19 crises was that transmission occurred in western countries. Unlike SARS, COVID-19 did not remain a foreign disease. Once in Europe, as with the AIDS epidemic, people who became infected, or who were perceived as engaging in so-called morally adjudicated “risky behaviours” were subject to moral judgements from the larger community. The COVID-19 pandemic, though very different from the AIDS epidemic, prompted a similar creation of “moralized behavioural scripts” (Blommaert 2020, 3). Blommaert says, “People who cough or sneeze…are instantly identified as ‘dangerous’ and treated with public suspicion or even aggression. Behaviour is moralized: obviously, ill people in public are quickly accused of being ‘irresponsible’ (2020, 3).”

Visible symptoms of COVID-19 became identifiers of potentially unsafe or infected individuals in shared social spaces. Close friends since high school, Marie a twenty-eight-year-old video game programmer and Cyril, a twenty-seven-year-old recent graduate in urbanism, attested to this in public transportation:

Cyril : Parce qu’au début c’est ça qui inquiétait les gens, fin, au tout début…c’était vraiment la toux, cette espèce de névrose, tu vois, quand tu étais dans un transport et les gens toussaient, c’était genre “Il a l’Ébola.” Tu vois ?

Marie : Ouais ! Il y a un mec qui a fait ça hier ! J’étais dans le train…j’ai toussé et il y a un type il est parti à l’autre bout de la rame ! *rire*[7]

The question of avoidance or calling out (whether publicly or in private discussion) people with COVID-19 symptoms became a topic of everyday conversation. My ethnographic observations and conversations were rife with judgements of various behaviours—mask-wearing, social distancing, socializing, and so forth. This moralization of social and personal behaviour did not necessarily lighten at the same pace as sanitary restrictions and was intensified by vaccination campaigns and restrictions on access to social spaces for the vaccinated versus the unvaccinated.

Acting the COVID19 Pandemic

People attested to understanding COVID-19 as a problem that must be brought under control through the application of scientific knowledge. As in the above example, a striking result of this way of thinking was the rapid creation and execution of moralizing behavioural scripts, which were present on a national level in government discourse and in individual interactions in which people condemned the actions of others. Once it is commonly accepted that the virus can be countered and that individuals have a responsibility to follow a series of measures to stop the virus, the atmosphere encourages the moralizing of individual behaviour on an everyday basis.

For example, Jean-Denis (63) is a banker who has lived in Montmartre for six years. He talked often about how he felt at greater risk doing his shopping aux Abbesses (or what locals refer to as “Les Champs Élysées de Montmartre”), than going to work in the bank downtown (where he felt the sanitary measures, including plexiglass, masks and distancing were sufficient). He was offended and felt he was “at risk” while at the butcher or baker and often made these feelings known to people who did not respect the health regulations.

Et je vois cette dame qui…qui se penche vers moi pour faire son compte vers le boucher à 20 cm et je lui dis, “S’il vous plaît, pourriez-vous vous repousser un tout petit peu pour respecter quelques règles ?”

Et elle me dit, “Mais, non, il n’y a pas de problème, j’ai un masque.”

J’ai envie de lui dire, mais excusez-moi, c’est parce que vous avez un masque que vous pouvez parler à 20cm de moi ![8]

Everyone had a story where they had chastised or been chastised by someone for not respecting mandated sanitary measures. Joanne, a twenty-eight-year-old acrobat who trains in the neighbourhood gymnasium, rode her bike to avoid wearing a mask. This is not because she is anti-mask (in May 2020 she used her sewing skills to produce over 100 masks for friends and family), but because it fogs up her glasses. She described being reprimanded by people around her or threatened with social sanctions, such as being asked to leave the premises when her mask did not cover both her nose and mouth:

Je me fais souvent engueuler dans les magasins parce que je le baisse en dessous de mon nez, juste le temps que la buée parte et il y a des magasins où on m’a dit que si je mets pas mon masque sur mon nez je peux sortir. Et, il dit ça, et moi je regarde la mauvaise personne parce que je ne vois pas parce que j’ai trop de buée sur mes lunettes ! *rire*[9]

Pascale is a forty-five-year-old marketing executive for FIFA who requested to be repatriated to France when she found herself working in Qatar at the onset of the March 2020 lockdowns. It was her first time in Montmartre; a neighbour she met at a local restaurant helped her find an apartment where she lovingly described the other residents using the category of “family.” Though she engaged in socially distanced activities with neighbours in her building, where everyone benefited from a large, exterior courtyard, she was scandalized to discover the behaviour of certain acquaintances. “Attends, la personne m’appelle tous les jours, ils sont 15 chez eux, juste à côté. Je lui dis, ‘Tu n’as pas compris. Moi je ne veux pas côtoyer des gens qui côtoient 15 personnes. Impossible!’” (“Wait, this person calls me every day, there are 15 people at his house, just next door. I told him, ‘You don’t get it! I do not want to spend time with people who hang out with 15 other people. Impossible!’”)

Alexis, a fifty-one-year-old musician who has lived in the neighbourhood for over a decade, was similarly appalled by his mother:

Ma propre mère a fini par m’obliger à monter chez elle, alors que je la voyais en bas, en faisant du chantage affectif. On a passé une super soirée, c’était très sympa. Le lendemain je l’appelle pour la remercier, elle était chez ses amis. Ils étaient six quoi. 79 ans. Bon voilà. C’est elle le danger pour moi, c’est pas moi le danger pour elle.[10]

Alexis assiduously followed health measures and had taken care from the beginning of the pandemic to ensure his mother’s safety. Social distancing guidelines had already affected their relationship. However, his realization that she did not respect health restrictions shifted his understanding of who was the greater danger to whom in their interactions.

The social and (un)sanitary habits of neighbours were key pieces of information to exchange within the community as individuals advocated their versions of healthy choices. These perceptions worked in opposing directions, as many unvaccinated people protested the pass sanitaire (“sanitary pass”) requirement or, on the contrary, as vaccinated individuals judged the unvaccinated for their refusal to cooperate with what the former perceived as the greater good.

The pass sanitaire was a required presentation of digital or paper proof of 1) vaccination, 2) a negative PCR within 24 hours or 3) a certificate of recovery. The implementation of the pass was a compelling example of how compliance became an issue of morality and risk. When initially released, many bars and restaurants in Montmartre continued to allow locals access, even without a pass. After a few weeks, more establishments began enforcing the requirement; refusing locals who did not have their passes. The pass challenged friendships and professional ties; I watched neighbours get angry at bar owners and had others speak to me privately about how, in their words, “dumb” or “dangerous” their non-compliant neighbours were acting. The pass sanitaire, like masks, became a visual signal of compliance by which individuals in the community were judged.

Conclusion: Disease Manufacturing and Post-Pandemic Futures

The ways people in my study talk about and act out COVID-19 go beyond generalized cultural knowledge, though they are a part of it. COVID-19 stories are constructed on the conceptual scaffolding of already existing cultural scripts, taboos, ideologies and beliefs, demonstrating how biological realities and social constructions are inseparable (Singer 2014). The COVID-19 pandemic is an excellent example of how culture “manufactures disease” (Inhorn and Brown 1990), in that societies change their ecologies and environments to actively increase or decrease the risk of certain diseases while sociocultural beliefs, ideologies and precedents provide the theoretical system for understanding and responding to disease.

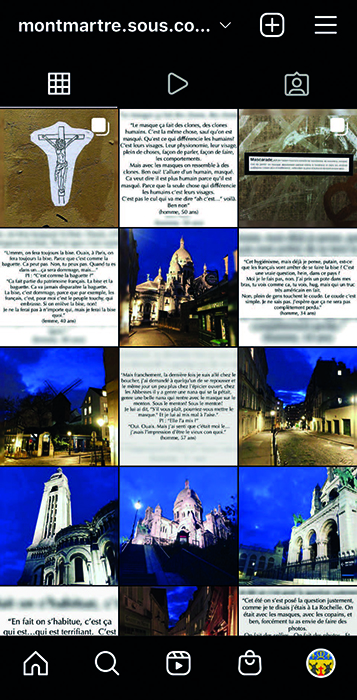

Illustration 4

Talk and stories of disease are foundational practices in sense-making of and (re)action to sickness, illness and disease (Masquelier 1993; Mattingly and Garro 2001). We embed our experience into readable or comprehensible contexts through stories and the creation of subsequent factual or fictional narratives (Wiercinski 2013). Sense-making practices concerning COVID-19 are not solely informed by scientific facts or generalized cultural knowledge. They are conceptually primed by analogies and cultural taboos; scaffolded upon existing narrative structures and ideologies. People’s comprehension and talk about COVID-19 are “awash in significance,” as Sontag (2002, 59–60) argues is often the case for an “important disease whose causality is murky, and for which treatment is ineffectual.” The meanings of these stories influence how people imagine their present and future possibilities by imbuing their worlds with sense, subsequently informing behaviours, beliefs, and goals.

Primary evidence of this in my research was the creation of moralizing behavioural scripts. COVID-19 generated new scripts about how people (should) use their bodies in space and as a social instrument. Among participants, understandings and reactions to these behaviours and their links to infection (or pollution) were informed by analogies with the AIDS epidemic, the cultural script of Europe being invaded by foreign plague, as well as racializing forms of xenophobia that were exacerbated by the pandemic and the stories told to explain it.

This research offers ethnographic evidence of how people’s sense-making of and reaction to crisis is informed equally, if not to a greater extent, by their conceptions of the world before the crisis, than by information accessible to them during the crisis itself. Whether or not the COVID-19 pandemic was as unprecedented as many journalists claimed, people with whom I spent time in Paris made sense of and reacted to it according to precedent. This sense-making was informed by individual experience, shared social traumas and collective conceptual schemas (such as bestiality, disease, and avoidance taboos). Well-ingrained conceptual categories and cultural scripts prime people for particular perceptions and inform how they make sense of and act and react to novel information, even during a period of potential catastrophe.

People did seek out and access new information concerning COVID-19. As discussed, COVID-19 talk in Paris was highly techno-optimistic, frequently referencing scientific data, experts, and expressing faith in scientific tradition. Though many talked about hopes for vaccines, treatments and preventing future crises, they were also deeply pessimistic. Their faith in scientific credibility was incomplete and permeated by mistrust at multiple levels—political figures, scientists, the media, and even people in their communities and families.

Mistrust, uncertainty and lack of control or ability to know are common emotions in the study. Nonetheless, these were not the ideas people generally emphasized when they spoke about the future. “Le rêve de leur nouvelle vie est de revenir à leur ancienne vie” (“The dream of their new life is to go back to their old life.”) Daphné, fifty-one years old, poetically summed up what most everyone talked about. Though “going back to normal life” possessed different meanings for different people, it became a common idiom, linguistically and emotionally. For my interlocutors, “the return to life as before” was the primary goal for the future.

Steven Black (2021a) similarly observed these notions of nostalgia, arguing that techno-optimism is not understood as an opportunity for radical change, but rather an opportunity for retrieving the past. Though people described the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic as having greatly destabilized certainty and social life and intensified socioeconomic inequalities and worries for the future, when they projected themselves into the future their focus was not on preventing future catastrophe, changing inequitable socioeconomic systems that exacerbated the effects of the pandemic or addressing unsustainable practices that contributed to the crisis in the first place (Black 2021a; Lambert and Cayouette-Remblière 2021). They did not express a predominant desire for change, but for return.

In 2020 and 2021, neighbours debated whether or not society and individuals would be permanently traumatized by the experience of the pandemic. Would les bises disappear, they asked. Would we tell our children when they see pictures from the summer of 2021, “This was during the pandemic when we had to wear masks” or “This was the year we had to start wearing masks all the time”? Though certain moralized behavioural scripts, uncertainties about the future, and nationwide sanitary measures persist, in the case of Montmartre there is, and has always been, evidence that permanent social trauma and change in the way it was imagined may not be the case. As restrictions endured, many people developed strategies to circumvent them or ignore them completely. Clandestine get-togethers, apéros ambulants, bars, bistros, nail salons and other businesses that accepted customers behind closed shutters became new forms of “getting back to la vie d’avant.”

As life shifts to a post-pandemic reality that includes more familiar patterns of work and sociability, there remains a swath of the population in Montmartre, and throughout France, who actively protest how this “return to normal” as it is referred to by government and medical experts, has been possible. Vaccination, the pass sanitaire, and paid PCR tests are among government measures taken to restore life and the economy to a certain level of activity. Though the return to a pre-pandemic normalcy, or what is referred to euphemistically as “going back,” appears to be the goal of the majority, how we return remains hotly disputed, yet another source of uncertainty and anguish.

The COVID-19 pandemic provided explicit examples of how communication can create chaos or calm and that this process is not just a question of communicating facts, but of understanding the conceptual worlds—the schemas, stories and symbols—that feed the distinct sense-making processes of the people interpreting this information. Ethnographic research such as this project contributes to a deeper comprehension of how people experience and make sense of crises and the uncertainties they engender. Because talk and stories are informed by and inform mental schemas, perceptions, and world views, they are important conceptual tools in sense-making practices as well as modes through which humans experience (Ochs 2012) and construct new imaginations and experiences of the world and the challenges we face within it.

Parties annexes

Acknowledgements

I thank the Fyssen Foundation for their generous support of the research on which this analysis is based, as well Montmartre—friends, neighbours, strangers and all of the participants who made this research possible and who made sense of the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic with me. Bertrand Masquelier, the LACITO laboratory and Anthropologica’s excellent editorial and blind peer reviewers provided input that strengthened the analysis.

Notes

-

[1]

“Enquête nationale sur l’épidémie du Covid-19.”

-

[2]

He [Didier Raoult] generated a sort of…idolatry we can talk about it in those terms, on social media, because he had hundreds of thousands of followers on certain platforms and he was highly mediatized…so all that contributed to nourishing…a general mistrust in the medical corps and of the government, also of laboratories, the famous Big Pharma, to generate conspiracies that were then fed by him.

-

[3]

I talked a lot, a lot, a lot with my family because they are all doctors. One of my brothers is a doctor, a specialist in catastrophe medicine, he works in a very big French hospital and he is in charge of the COVID ward.

-

[4]

It comes from…well, it’s very fuzzy. It’s very fuzzy, but like everything else that comes from China. *laughs*.

It supposedly comes from China, but we don’t exactly know how. If it comes from a market in Wuhan. What I mean is the meat market. I have images in mind, afterwards, maybe it’s just some kind of Western propaganda, I don’t know. So, I’m not going to judge based on that.

Meat markets are always a bit peculiar in countries that are…less sanitary, we’ll say. Poorer. In this case, either it came from a market…directly from the meat market in Wuhan, so…it would come from a bat, I believe, that would’ve had the virus itself and could transmit it.

-

[5]

As early as February 2020 violent attacks against the Chinese population in France linked to the health crisis dramatically increased (Wang 2020).

-

[6]

Mikhail: During the first confinement, I told everybody that it was Chinese people who had sex with monkeys and that’s what started COVID. Because at one time, there was a legend in France about how black people had sex with monkeys and that had caused AIDS. I tried to start the same legend for the Chinese, but it didn’t work. *laughs*

Arthur: The pangolin, that slept with a bat and they had a little COVID. *laughs* No, no…it’s like in the 1980s…when people started to say, “Yeah, AIDS comes from monkeys. It’s a homosexual who slept with a monkey.” Yeah. *laughs* No, I think there can be mutations, but it’s not as simple as that. So, we should leave the pangolin alone.

-

[7]

Because at the beginning that was what worried people, I mean, in the very beginning…it was coughing, this kind of neurosis, you know when you were in public transport and somebody coughed it was like, “He has Ebola.” You see what I mean?

Marie: Yeah! There was a guy who did that to me yesterday! I was on the train…I coughed and there was a guy who left to go to the other side of the car! *laughs*

-

[8]

And I see this woman…who leans over me to pay the butcher, 20 cm away from me and I say to her, “Please, could you back up a little bit to respect the sanitary rules?” And she responds, “No, there’s no problem. I have a mask.”

I wanted to say, excuse me, it’s not because you’re wearing a mask that you can talk 20cm away from me!

-

[9]

I get yelled at a lot in stores because I pull my mask down under my nose, just long enough so the fog leaves my glasses and there are some stores where I’ve been told that if I don’t put my mask on over my nose then I can leave. And someone says that, and I look at the wrong person because I can’t see anything with my glasses all fogged up! *laughs*

-

[10]

My mother finished by obligating me to come up to her house, even though I came to visit her from below the window, by emotionally blackmailing me. We had a great time, it was nice. The next day I called her to thank her, she was at a friend’s house. There were six people there. 79 years old. Fine. She’s the one who is dangerous to me, it’s not me who’s dangerous to her.

Bibliography

- Black, Steven P. 2021a. “Portable Values, Inequities, and Techno-Optimism in Global Health Storytelling.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 31 (1): 25–42. https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jola.12297.

- Black, Steven P. 2021b. “Linguistic Anthropology and COVID-19.” Anthropology News website, 26 March. Accessed 6 August 2021. https://www.anthropology-news.org/articles/linguistic-anthropology-and-covid-19/.

- Blommaert, Jan. 2020. “The coronavirus crisis of 2020 and Globalization.” Diggit Magazine, 3 December. Accessed 6 August 2021. https://www.diggitmagazine.com/column/coronavirus-globalization.

- Briggs, Charles L. 2002. “Why Nation States and Journalists Can’t Teach People to Be Healthy.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 17 (3): 287–321. https://doi.org/10.1525/maq.2003.17.3.287.

- Davies, Christie. 1982. “Sexual Taboos and Social Boundaries.” American Journal of Sociology 87 (5): 1032–1063. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2778417.

- Douglas, Mary. 2002 (1966). Purity and Danger. New York: Routledge Classics.

- Foucault, Michel. 1969. L’archéologie du savoir. Paris: Gallimard.

- Georgakopoulou, Alexandra. 2007. Small Stories, Interaction and Identities. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Good, Byron. 1994. Medicine, Rationality and Experience: An Anthropological Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hariman, Robert. 2016. “Public Culture.” Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Accessed 27 November 2022. https://oxfordre.com/communication/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228613-e-32.

- Hofstadter, Douglas and Emmanuel Sander. 2010. Surfaces and Essences: Analogy as the Fuel and Fire of Thinking. New York: Basic Books.

- Inhorn, Marcia C. and Peter J. Brown. 1990. “The Anthropology of Infectious Disease.” Annual Review of Anthropology 19: 89–117. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev.an.19.100190.000513.

- Lambert, Anne and Joanie Cayouette-Remblière, eds. 2021. L’explosion des inégalités : Classes, genre et générations face à la crise sanitaire. Paris: Éditions de l’Aube.

- Lee, Gregory B. 2013. “Migration et diaspora chinoises : La Chine et les chinois dans l’imaginaire des français.” Huaqiao: Regards sur les présences chinoises à Valence, Centre du patrimoine arménien, Valence, March, Valence, France. Accessed 14 August 2021. https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02070372/.

- Longhi, J. 2022. “The Parascientific Communication around Didier Raoult’s Expertise and the Debates in the Media and on Digital Social Networks during the COVID-19 Crisis in France.” Publications 10 (7): 1–16. https://www.mdpi.com/2304-6775/10/1/7.

- Masquelier, Bertrand. 1993. “Parler de la maladie. Querelles et langage chez les Ide du Cameroun.” Journal des Africanistes 63: 21–33. https://www.persee.fr/doc/jafr_0399-0346_1993_num_63_1_2370.

- Mattingly, Cheryl and Linda G. Garro, eds. 2001. Narrative and the Cultural Construction of Illness and Healing. Berkley: University of California Press.

- Ochs, Elinor. 2012. “Experiencing language.” Anthropological Theory 12 (2): 142–160. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1463499612454088.

- Roitman, Janet. 2021. “Crisis.” Political Concepts: A Critical Lexicon. Accessed 20 June 2022. https://www.politicalconcepts.org/roitman-crisis/#fn81.

- Singer, Merrill. 2014. Anthropology of Infectious Disease. Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press.

- Sontag, Susan. 2002 (1979 and 1989). Illness as Metaphor and AIDS and Its Metaphors. New York: Penguin Classics.

- Wang, Simeng. 2020. “Compte rendu : Mission d’information sur l’émergence et l’évolution des différentes formes de racisme et les réponses à y apporter.” Assemblée Nationale, 7 July, Compte Rendu 5. Accessed 14 August 2021. https://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/dyn/opendata/CRCANR5L15S2020PO768631N005.html.

- Wiercinski, Andrew. 2013. “Hermeneutic Notion of a Human Being as an Acting and Suffering Person: Thinking with Paul Ricoeur.” Ethics in Progress 4 (2): 18–33. https://doi.org/10.14746/eip.2013.2.2.

Liste des figures

Illustration 1

Illustration 2

Illustration 3

Illustration 4