Résumés

Abstract

Employing a triangulation method based on interviews, performance exercises, and think-aloud protocols (TAPs), this study probes the thought processes of ten Hong Kong translation trainees of diverse backgrounds to identify possible self-censorship during translation. The two English source texts for the performance exercise contained sensitive language or content with respect to sex and the trainees’ home country. A text containing mild criticism of Christianity was used as a control. It was found that most respondents were aware of the relationship between ideology and translation, and employed a semantically literal translation approach to render the ideological items in full. They took a broad range of factors into consideration, including translation purpose, text type, register, and target readership. Only one respondent self-censored his translation, while three others revealed their concerns about censorship during the TAP. The results show that the trainees share the same social habitus and highlight a need for ethics-awareness training in the translation curriculum. Given the current lack of such training as revealed by other surveys, recommendations for curriculum design are made. The influence of habitus on self-censorship could be further explored by comparing, for example, translation trainees and professional translators. The research methodology could also be replicated in other cultural and linguistic settings for a broader understanding of this topic.

Keywords:

- self-censorship,

- translation trainee,

- think-aloud protocol (TAP),

- Hong Kong,

- professional ethics

Résumé

En utilisant une méthode de triangulation basée sur des entretiens, des exercices pratiques et des protocoles de réflexion à haute voix (TAP), cette étude de cas vise à décrire les processus de pensée de dix étudiants provenant de contextes divers et inscrits dans un programme de traduction à une université de Hong Kong, afin d’identifier la présence d’une éventuelle autocensure pendant la traduction. Les deux textes sources en anglais contenaient un langage ou un contenu sensible concernant le sexe et la Chine, pays d’origine des étudiants. Un troisième texte contenant une légère critique du christianisme a été utilisé comme contrôle. Il s’est avéré que la plupart des étudiants interrogés étaient conscients de la relation entre l’idéologie et la traduction et qu’ils ont choisi une approche littérale pour rendre les éléments idéologiques dans leur intégralité. Ils ont pris en considération un large éventail de facteurs, notamment l’objectif de la traduction, le type de texte, le registre et le lectorat cible. Un seul répondant a autocensuré sa traduction, tandis que trois autres ont fait part de leurs préoccupations concernant la censure au cours du TAP. Les résultats montrent que les étudiants partageaient le même habitus social et soulignent la nécessité d’une sensibilisation à l’éthique dans les programmes de traduction en Chine. Compte tenu de l’absence actuelle d’une telle formation dans ces derniers, révélée par des enquêtes précédentes, des recommandations pour son inclusion sont formulées. Les résultats montrent également que l’influence de l’habitus sur l’autocensure mériterait d’être étudiée plus avant en comparant, par exemple, des étudiants en traduction et des traducteurs professionnels. Enfin, la méthode de triangulation utilisée pourrait être reproduite dans d’autres contextes culturels et linguistiques, ce qui permettrait d’élargir la compréhension du rôle de l’autocensure pendant l’acte de traduire.

Mots-clés :

- autocensure,

- étudiant en traduction,

- protocole de réflexion à haute voix (TAP),

- Hong Kong,

- éthique professionnelle

Corps de l’article

Introduction

The literary system in which translation functions is controlled by two main factors: (1) agents within the literary system, who partly determine the dominant poetics, and (2) patronage outside the literary system, which partly determines the ideology. Insofar as translation is a form of rewriting, the original work is often rewritten in order to conform to the reigning target-culture poetics and ideology of a particular time and place (Lefevere, 1992). Generally speaking, the term “ideology” can signify the notion of a “worldview,” which encompasses the knowledge, beliefs, and value systems of individuals and of the society in which they live (Lee, 2018, p. 245). Lefevere defines ideology as “the conceptual grid that consists of opinions and attitudes deemed acceptable in a certain society at a certain time, and through which readers and translators approach texts” (1998, p. 48). Translation is seldom, if ever, a value-free process or event. All decisions pertaining to this event—from the choice of a text to be translated right down to the specific techniques applied in the verbal transfer itself—are at least partially governed by extra-textual factors. Chief among these is the milieu; that is, the social, cultural, and political environment in which the translators and their works are located (Lee, 2018, p. 244). This is where censorship can come into play. After the sociological turn of the past decade (see Angelelli, 2014), Translation Studies has paid more attention to the roles of different agents and their interaction in the translation process, placing ideological issues at the centre of the research agenda (see López and Caro, 2014). Many scholars have become interested in how ideology influences the translator’s thought process when engaging in self-censorship, i.e. the “manipulative rewriting” of the source text (Tan, 2019, p. 40). Most studies, however, have focused on professional translators and product- and case-based examples. The point of interest here is how the translator’s ideology is reflected in the translation process, even if expressed subconsciously (see Munday, 2007). No empirical study has yet been designed to test this (López and Caro, 2014, p. 252).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study on self-censorship using the think-aloud protocol (TAP) to probe the thinking process of translation students while translating. Ten participants were recruited for the pre-performance interview and the performance exercise, which entailed translating a text containing sensitive language possibly leading to self-censorship. The interview answers, TAPs, and translations were analyzed to trace respondents’ thought processes, and conclusions were drawn regarding the pedagogical implications of self-censorship and professional ethics. In what follows, we will (1) review the recent literature on the subject, (2) describe the different methods used, (3) present and discuss the study results, and (4) end with a discussion of implications and recommendations.

1. Censorship and Translation

Every linguistic community has its own set of values, norms, and classification systems, which, in translation, may diverge from or coincide with those of the target culture. Not only are translators’ textual manoeuvres subtly shaped by their identities and ideologies (Lee, 2018, p. 245), they can artificially create the reception context of a given text, and be the authority who manipulates the culture, politics, literary system of the original, as well as its acceptance (or lack thereof) in the target culture (Álvarez and Vidal, 1996, pp. 2 and 5). Ideology in translation thus resides not only in the text translated, but also in the voicing and stance of the translator, and in their relevance to the receiving audience. These latter features are affected by the “place” of enunciation of the translator, which is an ideological positioning, as well as a geographical or temporal one. It could be a country, a region, an ethnocultural identity, a social class, or a language., for example. Questions surrounding a translator’s loyalty arise because the translator is inevitably committed to a cultural framework, whether it be that of the source culture, the receiving culture, a third culture, or an international cultural framework that includes both source and target societies (see Tymoczko, 2002).

Censorship itself must be understood as one of the discourses—often the dominant one—produced by a given society at a given time, and expressed either through repressive cultural, aesthetic, and linguistic measures or through economic means. According to Pierre Bourdieu (1982), every discourse is the product of a compromise between the expressive interest of an agent and structural censorship. As agents internalize the limitations of discourse, these form part of their habitus, which Bourdieu defines as the set of “dispositions” that generate practices, perceptions, and attitudes deemed to be “regular” or authorized without being consciously co-ordinated or governed by any “rule” (ibid, p. 168). In other words, “domesticated language” is “censorship made natural” (Gibbels, 2009, p. 74).

According to Camelia Petrescu, the term “axiology” is defined as a socially constituted formation of subjective ideological systems based on individual values (2015, p. 2). The interaction between ideology and axiology has become a matter of interest in Translation Studies, because, in mediated communication, the third actor, i.e. the translator/interpreter, is often presumed to have greater freedom of self-expression than the other two actors, the speaker and the listener. However, as translation has the ability to make the source culture visible within, and accessible to, the target culture, translated texts tend to attract censorial intervention insofar as they voice the presence of the Other (see Sturge, 2004).

Judith Butler uses the term “foreclosure” to describe the construction of subjects through implicit censorship—i.e. self-censorship—, which is seen to be operating “on a level prior to speech” (cited in Gibbels, 2009, p. 72). Self-censorship is always present at the back of the agent’s mind, but, due to its unpredictable visibility, it cannot be easily verified and thus exceeds any form of regulated control by external authorities. Self-censorship acquires “dictatorial power” over the translator when it establishes automatic translation practices (Billiani, 2007, p. 13).

Pertinent empirical research on self-censorship by translators in Chinese communities includes Robin Setton and Alice Guo’s 2009 study based on sixty-two completed questionnaires. Over two-thirds of respondents acknowledged sometimes toning down one of the following aspects: (a) rude or aggressive language: 52%; (b) criticism of one’s own country: 19%; (c) criticism of one’s own institution, company, or group: 18%; (d) criticism of another country: 11%. Zaixi Tan conducted detailed case studies of three well-known examples of censorship/self-censorship in the Chinese translations of Lolita and Animal Farm, as well as in the English translations of Deng Xiaoping’s writings. He found that when certain values, ideologies, cultural practices, and moral presuppositions become internalized by translators, their censorial behaviour is no longer a product of coercion but rather an active choice of their own (2019, p. 39). That said, there is often no clear dividing line between what is coerced (censoring) and what is one’s own (self-censoring) action in contexts where “politically or culturally sensitive” (ibid., p. 58) source texts (STs) are bound to be scrutinized by the censor’s/self-censor’s eye before the final target text (TT) is produced. This recalls Bulter’s notion of “foreclosure” cited above.

In another very relevant study, Lynn Tsai and Da-hui Dong looked at the cognitive knowledge structures of translation ethics by comparing Taiwanese student and professional translators and interpreters. They evaluated 30 undergraduate students, 19 graduate students, and 8 professional translators and interpreters, using a localized tool designed for this purpose. The study first lays out the key concepts involved in the cognitive diagnostic assessment (2010, pp. 199-200), followed by a test on the participants’ translation ethics knowledge structures. They then propose a practical tool to evaluate translation ethics. For their part, Ana María Rojo López and Marina Ramos Caro’s 2014 experiment measured the influence of a translator’s political stance on the time needed to find a translation solution when working with ideologically loaded concepts. The results showed that the type of expression significantly influences the time participants take to find a suitable translation. Words with a valence contrary to the participants’ ideological viewpoint elicited longer reaction times than words that were consistent with their beliefs (2014, p. 263).

The agents producing the target text, along with the patrons and other professionals, thus have the power to censor translations to make the ST ideology adhere to that of the receiving readership. Self-censorship is a result of translators being both the interpreters of the ST and writers of the TT, although, based on their axiological stance, the censorship they engage in is often invisible to others. As mentioned above, whereas the existing research focuses primarily on the products (the translations) of established translators to ascertain possible reasons for (self-)censorship, without considering their thought process, this study sets out to investigate the rationale behind self-censorship by translation trainees using TAPs. Given the step-by-step nature of translational problem-solving, the think-aloud method can yield a range of reliable data on the on-going mental processes involved (Lörscher, 1995, p. 887). The data is especially revealing of individual discrepancies in the participants’ translation procedures (Krings, 1987, p. 173). TAPs have been used extensively with different participants to record a variety of cognitive processes: dictionary consultation skills in translating (see Law, 2009), differences between novices and professional translators (see Göpferich, 2012), translation strategies and mistakes (see Lim, 2013), and the influence of ideology in translating (see Khoshsaligheh, 2018), to name a few.

Though ideology and (self-)censorship clearly play a role in translation, the thought processes of translation trainees have been for the most part overlooked. However, the present study differs from those cited above primarily in its methodology. Instead of using cognitive diagnosis to explore the trainees’ ideological inclinations (Tsai and Dong), or experiments to measure translating time when faced with sensitive content (López and Caro), we propose a triangulated analysis of interviews, translations, and TAPs to gain a deeper understanding of Hong Kong translation students’ thought processes and strategies of self-censorship.

2. Methodology

2.1 Research Objectives and Participants

This research aims to elucidate the following: (1) Hong Kong translation trainees’ thought processes when translating ideologically or politically sensitive items from English to Chinese, especially with respect to self-censorship; (2) the pedagogical and ethical implications thereof. Before implementing the research methods, the following hypothesis was made. Since there was no actual target readership for the translation exercise other than the researcher, it was assumed that the student trainees would follow the conventional translation principle of “fidelity” to the ST content because they shared a similar habitus (see Chang, 2008; Setton and Guo, 2009; Tan, 2019). The ten participants invited to participate were undergraduate students majoring in a four-year program in English and Chinese translation at the university where the researcher formerly worked. They came from a similar social background in Hong Kong and shared the same age range of 18 to 22.

While there are many differences between trainees and professionals, including translation speeds and proficiencies, the most salient variable relevant to this study is the much higher degree of automatization in professional translation, which cannot be accessed through TAPs (Fraser, 1996, p. 67). Lacking the protocols or automatic responses available to professional translators, trainees are more likely to reveal the influence of self-censorship on their thought processes. The present study can thus provide a fuller picture of self-censorship before students become professionals.

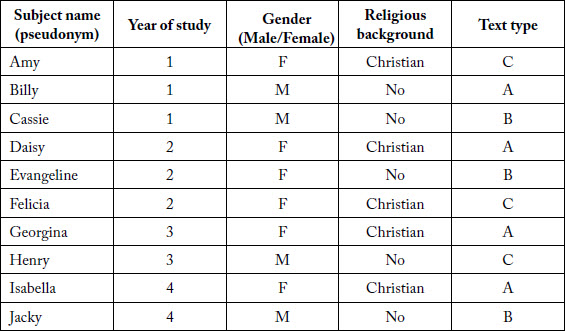

Three variables were taken into account: gender, year of study, and religious background (see Santaemilia, 2005; Fakharzadeh and Dadkhad, 2020). The participants’ basic information is outlined in Table 1 below, with pseudonyms for confidentiality. Although the sample size is small, consideration must be given to depth rather than breadth in qualitative research. Also, it is not uncommon for researchers employing TAPs to involve a small number of subjects, given the expensive and time-consuming procedures (see Johnson, 1992; Pressley and Afflerbach, 1995). The three texts used for the performance exercise cover two ideologically controversial issues: sex (Text A) and politics (Text B). The texts were assigned according to their content and the students’ background. For example, Text A was assigned to students of both genders for possible differences in their treatment of the sexual and vulgar elements. To avoid overload, each student was asked to translate only one text. Text C was used as a control, to see if students of the same habitus would censor even mild criticisms of religion. Invitations were made to students from mainland China, yet none responded. Although disappointing, this result was not unexpected considering the small student population with a mainland Chinese background enrolled in university translation programs in Hong Kong. It was therefore impossible to compare and contrast participants from different social backgrounds to determine whether mainland Chinese students would render Text B differently from their local-born counterparts. Given the rather lengthy time commitment asked of participants, the latter were all paid, which had no bearing on their performance and answers.

Table 1

Basic demographic information on the ten participants and their translated text type

Text A: with vulgar and sexual language (for two males and two females)

Text B: with content critical of one’s own country (for three students)

Text C as control: with mild criticism of Christianity (for two Christians; one non-Christian)

2.2 The Methods

The ten interview questions were intended to provide information about the participants’ possible ideological leanings. The first question focuses on their understanding of general translation principles, and the second, on their knowledge about the relationship between ideology and translation. The next four concern their attitudes towards sensitive issues in four areas: (1) vulgar language; (2) sexual language; (3) language against one’s country; and (4) language against one’s religion (Setton and Guo, 2009). These questions help disclose the respondents’ axiological positioning with respect to both translation norms and sensitive language, and their responses can be compared with what their TAPs reveal when actually completing a translation task. The four remaining questions focus on their personal backgrounds. Students could reply in their first language—Cantonese—to facilitate ease of expression. All procedures were duly explained and clarified before participants submitted their data collection consent forms.

A pilot trial was conducted prior to the actual performance exercise so the participants could become familiar with the TAP. The text was taken from Hilary Clinton’s autobiography Living History (2003), which includes content omitted from the published Chinese version for being too politically sensitive (Tan, 2015). Since no translation brief was provided for the performance text, students could approach it without restrictions and focus on their ideological and axiological positioning vis-à-vis the latter.

The overall methodology adopted in this study is a data-driven, qualitative approach (Cohen et al., 2000, p. 110). This means that, after collecting the data and analyzing the relations between variables (Boyatzis, 1998, p. 30), test-based research can help the researcher prove or disprove the initial hypotheses and provide reliable data to validate the protocols used (Nesi, 2000, p. 31). For the present study, the performance exercise was not graded, but only used for comparison with the results of the thought processes revealed by the TAPs. This was clearly explained to the participants, who could thus use their first and target language (written Chinese) to concentrate on the choice of words for the sensitive language. The word counts of the English STs ranged from 60 (Text A) to 106 (Text C) to 109 (Text B). Short text-lengths were chosen to offset the possible mental burden of the thinking-aloud method. The free quantitative analysis platform Voyant (https://voyant-tools.org/) was used to ensure the STs’ readability in terms of vocabulary density and sentence length. The texts represent a manageable level of difficulty for undergraduate students and were designed for the translation to be completed in around 45 minutes, without too much mental exertion or pressure.

Text A was a literary text taken from Naked Lunch by William Burroughs (1978), containing vulgar language and explicit sexual content, especially in relation to homosexuality, a taboo subject in Chinese communities (see Yu and Zhou, 2018). Text B was a journalistic commentary: “After 70 Years of Tyranny, Where does China Stand Today?” by the editorial board of The Orange County Register (2019). The entire passage expresses negative views on China, the participants’ home country, which could elicit censorship given the country’s recent political climate (see Xu and Albert, 2017; Anon., 2021). Indeed, recent writings deemed in violation of the National Security Law imposed in 2020 have resulted in imprisonments (see Hong Kong Watch, 2023; Human Rights Watch, 2022). Text C is another journalistic piece: “Three Reasons Why Nobody Wants a ‘Christian’ Label” by Craig Gross (2019), with mildly unfavourable judgments of Christianity. The full STs are found in Appendice 1. The specific sensitive segments are listed alongside participants’ translated versions in Section 4.2 below.

3. Results

3.1 The Interview Results

With respect to their general translation principles, five respondents preferred a more literal approach, and the other half a more liberal one. The use of one approach or the other depended on certain factors, the text type and target readership being the most common. Some participants referred to equivalent effects and skopos theory. Given their curriculum, none of the three Year 1 students had taken any courses with an ideological component. The seven seniors described what they had learned in several courses (see Department of Translation, The Chinese University of Hong Kong for the course list, and Table 7 for specific course titles). They were aware of the influence of ideology on translation at least on the theoretical level.

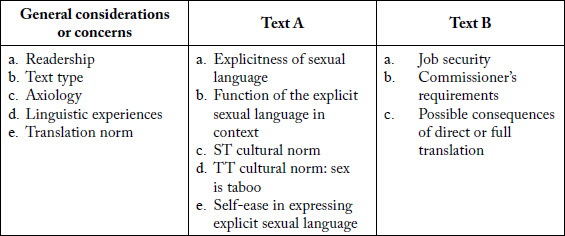

Seven participants said they would translate the sexual expressions in the ST with the readership in mind, adhering to the principles stated in Question 1, while the others said they would tone down the references. Their decisions would be based on the explicitness of the expressions and the text type. The rendition would be direct and full if the text were academic in nature; implicit or partial if general. Two of them said that as sex is taboo in Chinese culture, they would make the English expressions implicit for reader acceptance. But in the opposite language direction, they indicated that an implicit Chinese source could be rendered in full in English. The two students were more concerned with internal inhibitions, especially when the topic was not part of their usual writing or reading. They regarded linguistic inexperience to be the main hurdle, which, in the end, was overcome by adhering to the translation norm of being faithful to the ST. In this case, professional ethics seemed to take precedence over personal preferences and cultural experiences (Cassie, Daisy, Evangeline, Felicia, Henry, and Isabella). The following quotes from interviews and TAPs are translated from the students’ native tongue, Cantonese, a spoken variety of Chinese.

It is not common to be so explicit about sex in Chinese, although it is so in English. Personally, I prefer to use euphemisms for sex in Chinese. I am not used to expressing it explicitly.

Daisy

Sex is taboo in Chinese culture. In English-Chinese translation, it should be implicit. I will downplay or tone down the expression in Chinese. The TT readership can accept it more easily.

Henry

Respondents had a more open attitude to vulgar expressions than to sexual content, with little concern about offending target readers. Such language is common in Cantonese daily life. The students thus showed less concern for toning it down, but gave more thought to its emotive effect, especially when used in films or novels. Recreating an equivalent effect in the TT was deemed important (Cassie, Felicia).

Cantonese vulgar expressions are abundant. I have no bias against using vulgar language. It can express the ST emotion when it is rendered fully. If the language is toned down, it may affect emotional expression. But meaningless vulgar expressions can be toned down.

Cassie

Reference to political issues elicited the most diverse and notable feedback. With respect to political language against one’s country (China), more students had practical concerns, mostly about the consequences of direct translation: job security (Cassie), commissioner’s concerns (Daisy, Isabella), the social climate and reader reception, whether it was politically liberal or conservative (Georgina, Henry, Evangeline), possible political manipulation (Jacky); whether it would be published or banned, or whether the general public would be annoyed by the hostile evaluation (Isabella). They tended to tone down the negative message or even give it a positive slant. Cassie distinguished between negative news and subjective comments. The former could be rendered, while the latter should be adapted. Yet he added that a professional translator should aim for a neutral political stance.

For the question involving criticism of faiths or beliefs, most interviewees were open-minded, probably because only half were affiliated with an organized religion (Christianity). All deemed faith to be something personal that should not interfere with the translation job. Though a few still expressed concerns about reader acceptance, negative representation of these values was considered tolerable, as long as it didn’t cross the line of violating their own beliefs. All five of the Christian students (Amy, Daisy, Felicia, Georgina, and Isabella) agreed on this. Only Henry, although not professing any faith, said he would consider toning down this kind of offensive content.

In comparing the replies of junior students (six in total) to those of their seniors (four in total), no significant difference was identified, except for Question 2 about the relevant courses taken. This result is understandable, given the small sample.

3.2 The Performance Exercise

To avoid risks during the pandemic, all data collection was conducted on Zoom. The STs were sent to the participants after the instructions had been explained and clarified. Since several participants expressed embarrassment or anxiety about working on camera, none of the sessions were filmed, thus ensuring a more natural ambiance. The students then translated the ST while thinking aloud. At times, they were prompted to keep thinking aloud, if silence was maintained for too long. Upon completing the exercise, they were asked to send the TTs to the researcher via Zoom. The time it took participants to complete the task did not necessarily correlate with the text length. The shortest was 15 minutes by Jacky with Text B, and the longest was 90 minutes by Amy with Text C. The segments of interest and corresponding versions are laid out in Tables 2 to 4 below. Back-translations [BT] of the Chinese are included.

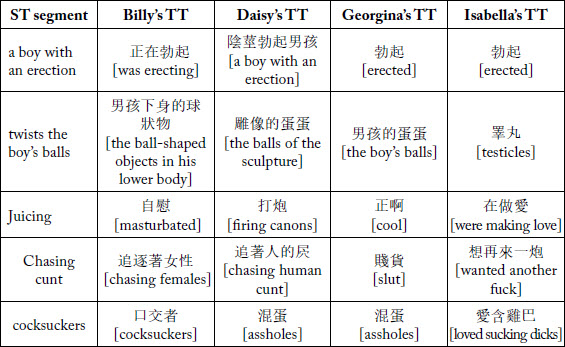

Table 2

Chinese versions of the sensitive segments in Text A by four subjects

Billy chose “implicit” translation for easier reader reception, since he was not used to translating sexual expressions. He generalized “balls” to be “ball-shaped objects,” figuring that TT readers could deduce the meaning from the context. In “chasing cunt,” he has diluted the offensive slang “cunt” into a neutral form “females.” Daisy also took reader receptibility into account, but chose to fully convey the same message and style in the TT. Georgina found her translation to be consistent with her approach to this type of language, without any toning down of the content. But she was not aware that “juicing” carries a sexual connotation, and rendered it as “cool,” probably as a result of misreading rather than ideological rewriting. Isabella also rendered the sensitive expressions fully for Chinese readers’ appreciation of the literary text, even though she was aware of the latter’s moral standards. Lacking professional experience in translating homosexual elements, these trainees were not versed in the common techniques of accentuating (to emphasize or expand), suppressing (to delete or simplify), or interfering with (to add comments on) this content (see Yu and Zhou, 2018):

[…] for the offensive expression “God damn it,” I have to ponder if the tone in Chinese would be strong enough. Can I use 該死的 [the damned], or 他媽的 [fucked]?

For “juicing,” if I choose euphemisms in Chinese, it would not be vulgar enough.

Daisy, Text A

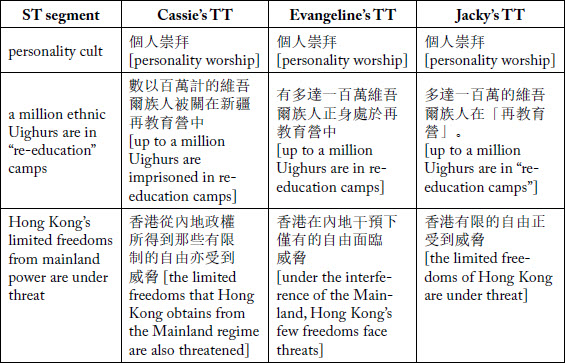

Table 3

Chinese versions of selected sensitive segments in Text B by three subjects

Since the whole passage in Text B depicts China unfavourably, only three selected segments with their translations are presented. Cassie felt he was consistent in applying his principle in translating the ST with a full rendition. He considered changing the meaning of “personality cult” to be more cynical to fit the context. Realizing he was being subjective, he decided to maintain the literal meaning in the end. Evangeline reckoned that Hong Kong was comparatively liberal, and so she dared to use close translation to achieve the same tone and message. All the translations seem to have adopted the close translation approach, with minimal adjustments to the content or tone, contrary to what half of the interviewees claimed they would do in the interviews:[1]

I would personally retain the tone against China in the ST; but professionally, I will consider censorship for job requirements, too. (Daisy, Text B)

Text C served as a control, to show if participants would respond differently when faced with a text that was not very controversial ideologically.

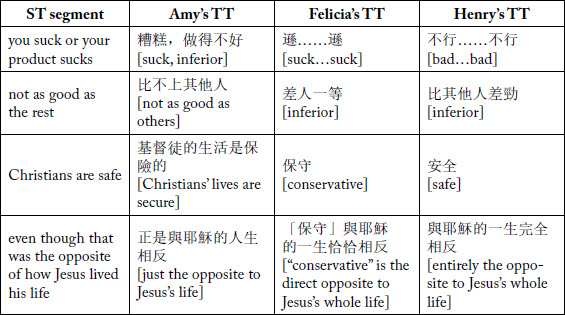

Table 4

Chinese versions of the negative segments in Text C by three subjects

As Christians, both Amy and Felicia gave full translations of the negative expressions involved, though on different grounds. The latter did not take the negativity personally, reckoning that criticisms against a religion are common. The former disagreed with the ST author’s view, yet she was concerned if she gave an inaccurate rendition, the potential readers might agree with the author. Being a non-believer, Henry claimed that the translator has the right to change, add to or delete the ST content, though he did not see the need to so do in this case. Compared with Texts A and B, Text C did not pose any challenges to their axiological positioning, and participants tended to adopt the direct translation approach, without any self-censorship.

3.3 TAP and Retrospection Results

The TAP analysis targets the ideological parts in the STs instead of the whole passage. The original plan was to design TAPs based on participants’ responses, i.e., to be data-driven. Constructs would be created after the TAPs were collected and analyzed for any patterns. But in the end, the only identifiable construct was similar translating procedures: (a) first reading of the ST, giving thought to the text type; (b) looking up difficult words in dictionaries; (c) translating both content and tone in full, generally with a literal approach; (d) editing for clarity, fluency, and naturalness. Having been informed that their STs contained ideological features, students paid special attention to them. But about half of the participants expressed having “no ideological issues” when deciding how to proceed. They cared more about how to achieve the equivalent effect in the target language.

Who is the target readership? [...] There are no ideological concerns.

Jacky, Text B

In retrospect, Evangeline was worried about the use of the communication platform Zoom for fear of possible consequences if the recording was censored by the authorities (see O’Callaghan, 2020; Wood, 2020). But she was hesitant to express those fears.

I don’t want to be explicit in expressing my political stance about Hong Kong and China. So I have to be reserved about my feelings and thoughts.

Evangeline, Text B

Both Cassie and Henry found the TAP useful for making them mindful of their thoughts in spoken form. Over the whole data collection process, Henry’s answers demonstrated the most self-censorship. In the trial exercise, he imagined the target readership to be mainland Chinese.

I am sensitive to mainland Chinese reactions online. I wanted to avoid such responses after my assumed readers read the TT. It was expected that the TT would be circulated among mainland Chinese communities.

Henry, Trial exercise

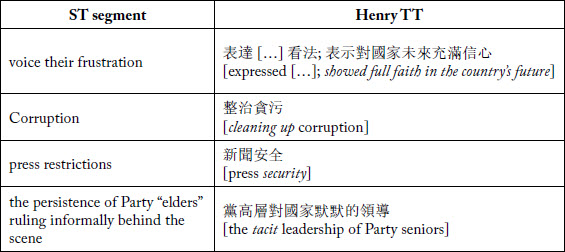

Henry made a number of changes to give the TT a positive slant (Table 5). He used framing or generalization to present a reality that diverged from the ST (see Pan, 2014, 2015; Qin and Zhang, 2018 for more examples). The changes, be they addition, deletion, or alteration, are highlighted by italics. The negative connotations of words or expressions often become positive: “frustration” becomes “full faith in the country’s future”; “corruption” is rendered as “cleaning up corruption”; “press restrictions” is rewritten as “press security.” This is a typical illustration of how translators sometimes artificially create the reception context for a given text (Álvarez and Vidal, 1996), with “domesticated language” (Gibbels, 2009, p. 74). Henry was more field-sensitive to the rules of authorized speech and used strategies that subtly but effectively altered the tone of voice (see ibid.).

Table 5

Chinese version of the sensitive segments in trial exercise by Henry

Overall, a variety of strategies were applied by these students to manipulate the texts ideologically, not unlike the case in Afzali’s 2013 study. Apart from Henry, their approach proved to be more linguistic than cultural or ideological. The TAPs, however, reveal how students consciously manipulate a political text based on their value systems. At the same time, the results support Künzli’s (2004) and others’ observation that translation students tend to stick more closely to the ST than professionals.

A few thoughts can be summarized here. (1) The results of this study concur with those of Setton and Guo’s 2009 survey of Chinese translators and interpreters (hereafter “translators”), where only a minority of respondents said they would self-censor for sensitive language and content, whereas more than half would change rude or aggressive language, and about one fifth would do so when facing criticism of one’s own country. In the present study, both Texts A and B seemed controversial to the students, causing them to struggle more over their options before penning down their TT. However, although all respondents shared a similar Chinese cultural background, our sample is too small to make any conclusive observations. (2) Most students rendered the STs in full using close translation, i.e. introducing the ST language and meaning into the TT, suggesting a relatively liberal ideological stance. One probable factor is that they did not face any actual threat of external censorship: they knew their translation would not be published or read by the outside world, so the inclination to dilute or delete elements was minimized. (3) Their considerations and concerns were comprehensive, including translation purpose, text type, register, and target readership. Since all participants were close in age, grew up and were educated in Hong Kong, it can be assumed that they shared the same social habitus.

Table 6 summarises participants’ considerations or concerns in handling the two texts with sensitive language or content.

Table 6

Summary of the participants’ considerations and concerns about translating Texts A and B

In relation to ethical decision-making, Meng (2022, p. 393) made a review of the neurocognitive models and found that they fall into three categories: rationalist, intuitionist, and dual-system. The rationalist and intuitionist models occupy opposite ends of the continuum. The rationalist models interpret ethical decision-making as a stepwise process (Meng, 2022, p. 393) Without any translation brief being imposed, students followed the rationalist model in their translation ethics decision-making. Henry’s trial exercise is a case in point. According to the rationalist model, in Stage 1, he was attentive to the morally relevant information in his task and parsed it into meaningful neurocognitive patterns. In Stage 2, he actively matched the encountered moral patterns with his stored ethical prototypes, i.e. his political leanings, suggesting a close convergence between his situation in the translating exercise and his past experiences in relevance to the content of the passage. However, it seems his ethical prototypes did not converge with the message in the ST, and pattern-matching failed. In Stage 3, Henry exercised his rational reasoning over his intuitive decisions, and attuned them to the new stimuli, i.e. the politically negative comments against China.

In the context of our study, participants cared more about how to achieve the equivalent effect in the target language than about possible consequences, but they were not working with institutional texts. Our text types were fiction (Text A) and news commentaries (Texts B, C). It is unclear how translation trainees might respond when handling texts in conflict with their moral values and subject to censorship by a commissioner (see Beaton, 2007). Translator trainers should be aware of this in preparing their trainees for future professional development.

3.4 Triangulation of Results

With respect to ideologically loaded expressions in the ST, the participants’ pre-exercise answers were compared with their translation decisions and post-exercise comments, as seen in Table 7 below. Quotations from their interviews and retrospective reports are included for easy comparison. Their actual TT segments can be referred to in Tables 2 to 5 above.

Table 7

Triangulation of results in the pre-exercise interview and the retrospective report (participants’ words in quotations and italics)

Text A: with vulgar and sexual language

Text B: with content against one’s own country

Text C as control: with mild content against Christianity

The triangulation of results provides an interesting picture of the students’ attitudes before and after the exercise. These can be categorized into two types. The first type includes those who remained committed to their translation principles in word and action (Daisy, Evangeline, Felicia, Henry, Isabella, and Jacky). The second type revealed a more ambivalent attitude. During the translating process, their tendency toward implicit censorship or “foreclosure” contradicted their earlier claims (Amy, Billy, Cassie, and Georgina). But in the end, they chose to let their habitus (“fidelity” to the ST) prevail and subdue possible self-censorship (except for Henry in the trial exercise). This distinction is not so much a reflection of their translation competence or personal character, but rather a question of professional training. As trainees, they are not experienced in coping with all the possible translation situations. As such, they were not certain what attitude they should take or what translation approach they preferred when faced with an ST that was ideologically or axiologically charged and at odds with the TT culture. In other words, they have not internalized the limitations of discourse as part of their habitus. This is where professional ethics training is called for to prepare them for these challenges.

4. Discussion and Pedagogical Implications

In 2001, Anthony Pym observed that the scope of translation ethics had widened to include the translator’s agency. But a codified and comprehensive curriculum addressing the issue of text manipulation is still lacking in most of the universities that offer translation courses. Mona Baker and Carol Maier (2011) argue that for students to embrace translators’ responsibility and develop an awareness of their impact on society, the classroom must be configured as an open space for reflection and experimentation. Many scholars hold similar views about the importance of professional ethics in translator training (Rodríguez de Céspedes, 2017; Schnell and Rodríguez, 2017; Liu, 2019 and 2021; Olalla-Soler, 2019; Koskinen, 2020). Educators need to offer trainee translators the conceptual means to reflect on various issues and situations they may be confronted with in professional life, and which they may find morally taxing, without falling back unthinkingly on rigid, abstract codes of practice. Given these observations, it is worth looking at the pedagogical practices in place.

4.1 The Current Scenario

Joanna Drugan and Chris Megone (2011) surveyed translator training programs in the UK and found that ethics is typically not taught at all, or is offered only as part of optional modules. The two scholars defined key areas of study in ethics and identified the main ethical challenges that translators face every day in their work. In China, Yong Zhong’s (2017) exhaustive online search found that complete ethics courses/modules are taught only in a small number of Chinese-to-English Translation and Interpretation (CETI) programs on the tertiary level, where the subject tends to be treated as a set of stagnant concepts (e.g., confidentiality, impartiality, and punctuality) and is presented as a list of dos and don’ts, thus lacking the depth and scope of ethics studies found in other professional disciplines (e.g., medicine and law) that deal with interpersonal relationships. In the same vein, Jie Wang and Yuanyuan Li (2019) observed that discussion of ethics awareness in professional translation has tended to centre on the perceived qualities of loyalty or fidelity to the ST, rather than exploring ethics as a value-based professional system.

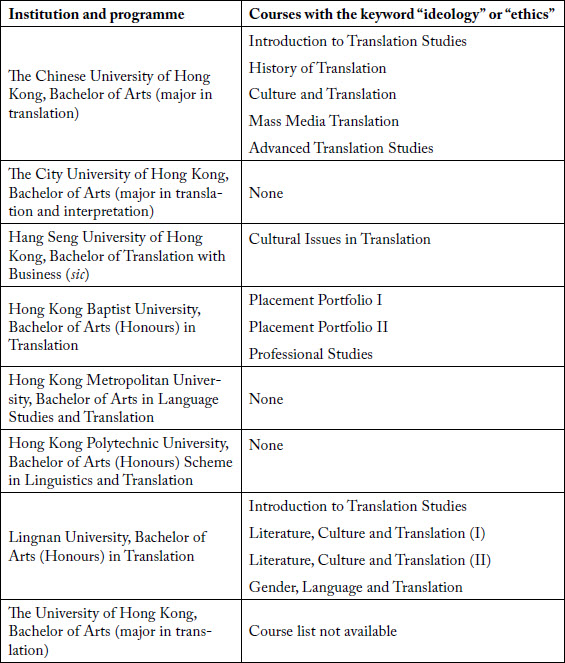

Similarly, this researcher did a cursory survey in June 2023 of the curricula available online to identify any references to ethics training at the eight undergraduate translation training programs in Hong Kong. Keywords like “ideology” and “ethics” were used to search the program course lists. The survey was not intended to be exhaustive but aimed only to sketch a general picture of the relevant training in the city. The results are shown in Table 8 below.

Table 8

Details of Hong Kong translation undergraduate programs featuring topics related to “ideology” and/or “ethics” as of 2023

Out of the eight undergraduate translation programs in Hong Kong, only Hong Kong Baptist University offers courses specialized in “Professional Studies,” which appear to include professional ethics training, given the course objectives. The situation is similar to that observed by Drugan and Megone (2011) in the UK. During the research period of this article from 2021 to 2023, a few study programmes seem to have undergone structural re-organization, with some course lists no longer available. The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hang Seng University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Baptist University, and Lingnan University still provide courses in relation to “ideology” and “ethics” on their course lists. The overall picture shows that ethics is not a key component in translator training in these programs.

4.2 What Should Be Included in Ethics Training

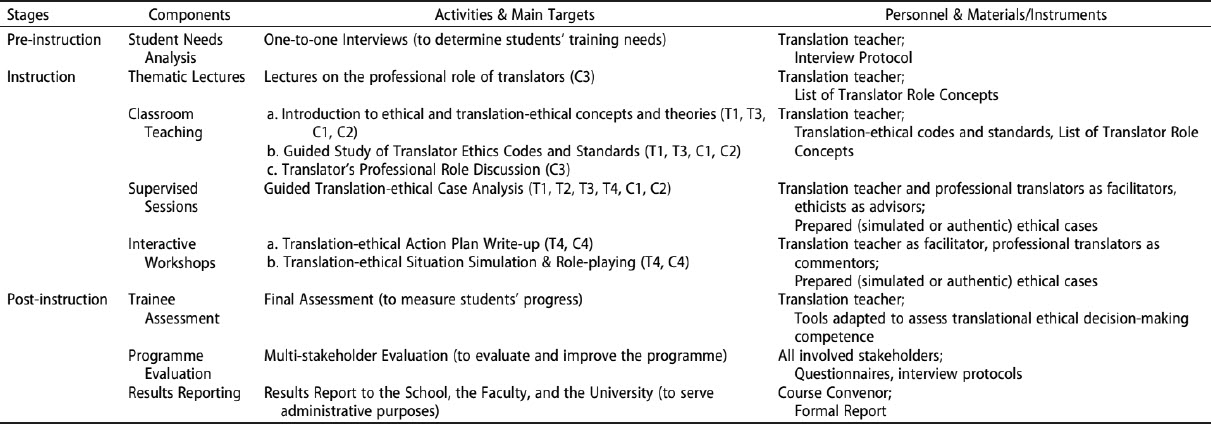

Zhou Meng (2022) argues that translation ethics education has shifted from preaching abstract, universalistic translator codes of ethics to developing the students’ ethical sensitivity and reflexive moral judgement (i.e., ethical decision-making). There is a growing consensus that translation ethics should be explicitly taught using flexible pedagogical activities (e.g., ethical case studies) to sensitize students to ethical issues in translation, sharpen their critical judgement, and provide them with a repertoire of moral problem-solving strategies (Tymoczko, 2007; Baker and Maier, 2011; Baker, 2013; Floros, 2021; cited in Meng, 2022, p. 2). Meng proposes a framework centred on students’ translational ethical decision-making competence (TEDC) and outlines a competence-based education program tailored to their needs. It borrows the Neurocognitive Model of Ethical Decision-Making to theorize the dual components of TEDC, i.e., intuitive and rational ethical decision-making, and proposes a tentative TEDC-targeted translation ethics education program, which is listed in Table 9 below.

Table 9

Overview of the stages and corresponding activities of the proposed program

(T1-T4 refer to the four targets of intuitive ethical decision-making education, and C1-C4 to the components of the Four Component Model)

Meng’s proposal outlines the possible stages, components, and activities that could be tested in translation classrooms. The biggest challenge is to design and validate the different course materials for teaching and assessment purposes (e.g., interview protocols, List of Role Concepts, representative ethical cases), which requires collaboration between the translation teacher, professional translators, and ethical experts (ibid., pp. 14-15).

In the “pre-instruction stage” for “student needs analysis,” Meng proposes “one-to-one interviews” to determine students’ training needs. This is a commendable component, for as we saw in Section 3.3, individual students do differ in their realization of their habitus and field. The interview should be able to sensitize them to the issues involved. But as the study results above show, the analysis would be more accurate using TAPs representing students from diverse backgrounds, including their gender, cultural background, year, and ethical proclivities in a performance exercise. With little professional experience, students may not be aware of the challenges in real-life situations, and what they claim in a pre-exercise interview may differ from their translation outcomes (Section 3.4). The considerations and concerns revealed by students in this study (see Table 6) should also inform the program design, especially given their particular social and cultural context.

Conclusion

This research set out to investigate the thought processes of translation students when translating sensitive items from English to Chinese. Results show that their groundwork analysis was quite comprehensive, including text type, translation purpose, target readership and register. Reader reception of these was also considered. As the target readership was not specified in the performance exercise, Chinese trainees assumed that their reader expectations would align with the ST ones, and their performance confirmed the hypothesis that participants would adhere to the field norm of “fidelity” to the ST. Since there were no participants with a mainland Chinese background, it is unknown if their different social habitus would have produced different results. This triangulation-based study reveals the “power” or “foreclosure” operating at the back of the translation agents’ minds. As the triangulation results in Section 3.4 show, self-censorship has not become an automatic or internalized practice, as some students still struggled with their decisions during the translation process (see Billiani, 2007). Both Amy and Henry recognized the TAP’s usefulness in helping them discover their inner voice when verbalizing it. Even when all participants render full translations using a semantically literal approach, their reasons for doing so may differ. The TAP can thus shed light on their translation procedures, strategies, and deliberations. Teachers can then point out students’ strengths and weaknesses and give them advice. The present study further highlights the importance of raising trainees’ awareness of ideology and (self-)censorship. It is hoped that it can inform translation training institutions and encourage them to incorporate these topics into their curricula. In reference to Meng’s proposed program for translation ethics decision-making, the information collection process proposed here could render student-needs analysis more reliable and relevant.

A limitation of this study was the sample size of each variable and the range of variables (gender, year of study, religion), which were too small for the findings to be conclusive. A larger sample could produce more convincing results, though it would still be impossible to generalize the degree of self-censorship. A study contrasting student translators from China and from a totally different cultural background, e.g., a European nation, or the USA, could provide further insight into who self-censors, what they censor, and why. While self-censorship due to concerns about political approval, job prospects, and online censorship is predictable, it would be interesting to learn whether westerners and Africans self-censor for the same reasons, for example. Other studies could focus on the roles of gender, age, education, academic and political position, field of study, or the commissioner’s influence on participants’ ideological manipulation of texts (Afzali, 2013, p. 11), including both general and institutional texts. Moreover, this study could be replicated in other language combinations and involve translation novices of different cultural and social backgrounds, since their axiological positionings would likely vary. The same methodology could also be used to compare trainees and professionals to examine how their respective habitus influence their thinking and work. Pedagogically, ethics training in translation and its effectiveness in enhancing trainees’ awareness could be the basis for a new area of research on this subject.

Parties annexes

Appendix

I. The full texts

Trial exercise

Students in Beijing and other cities took the opportunity to voice their frustration with corruption, inflation, press restrictions, university conditions, and the persistence of Party “elders” ruling informally behind the scene. (Clinton, 2003, p. 409)

Text A

[…] topped by a gold statue of a boy with an erection. He twists the boy’s balls and a jet of champagne spurts into his mouth. He wipes his mouth and looks around.

‘Where are my Nubians, God damn it?’ he yells.

His secretary looks up from a comic book: “Juicing… Chasing cunt.”

“Goldbricking cocksuckers. Where’s a man without his Nubians?” (Burroughs, 1966, p. 151)

Text B

President Xi Jinping has removed the two-term limit on the presidency and seeks to build a personality cult around himself. Up to a million ethnic Uighurs are in “re-education” camps. Hong Kong’s limited freedoms from mainland power are under threat. Chinese military actions in the South China Sea have antagonized neighbors. Overlaying that strife is the economic reality that China’s once-juggernaut manufacturing prowess is in decline. Industrial output is down, retail sales are sluggish, the jobless rate has risen, the currency is not replacing the dollar in trade and finance as hoped and the government is snapping up stakes in private companies in an effort to prop up entrepreneurship. (Editorial Board, 2019, n.p.)

Text C

That means you suck or your product sucks. If you are a Christian company or have a Christian product then traditionally that means you are not as good as the rest.

Safe. Christians are safe. We put our kids in Christian schools to protect them. I know this because my parents did this to me my whole life. I want to teach my kids not to play it safe. I don’t want my kids living in a world centered around fear, and when you are labelled a Christian, it often means safe even though that was the opposite of how Jesus lived his life. (Gross, 2019, n.p.)

II. Pre-performance exercise Interview

What is your translation principle in general?

Have you been taught about the relationship between ideology and translation? Which course(s)? What have you learnt about it?

How would you translate sexual expressions in the source text? Why?

How would you translate vulgar expressions in the source text? Why?

How would you translate expressions against your country? Why?

How would you translate expressions against your religion or beliefs? Why?

-

Year of study in university:

A. Year 1 B. Year 2 C. Year 3 D. Year 4 or 5

Gender: A. Male B. Female

Growth background: A. Hong Kong B. mainland China C. Other:

Religion:

Post-performance exercise question

How do you reflect upon your translation principle now that you have finished one text with possibly offensive content?

Acknowledgements

This research was partially funded by The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The researcher is grateful to the reviewers’ very constructive comments and advice.

This is to acknowledge that no financial interest or benefit has arisen from the direct applications of this research.

Biographical note

Law Wai-on is formerly a lecturer at the Department of Translation of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. His research interests include bilingual lexicography, translator studies, the translating process, translation policy, and translation pedagogy. His recent publications are: “In Search of a Translation Policy for Hong Kong.” Journal of Translation Studies (forthcoming) and “Roald Dahl’s Voice in Chinese: A Study of Two of his Translators and their Translations.” SPECTRUM: Studies in Language, Literature, Translation, and Interpretation (forthcoming).

Note

-

[1]

In this researcher’s retrospective opinion, if participants could be tested or asked prior to the task about their political views, it would be easier to understand and predict their responses in handling politically sensitive issues in the translation exercise (see López and Caro, 2014, p. 254).

Bibliography

- Afzali, Katayoon (2013). “The Translator’s Agency and the Ideological Manipulation in Translation: The Case of Political Texts in Translation Classrooms in Iran.” International Journal of English Language Translation Studies, 1, 2, pp. 193-208.

- Álvarez, Román and Carmen-África Vidal (1996). “Translating: A Political Act.” In Román Álvarez and Carmen-África Vidal, eds. Translation, Power, Subversion. Clevedon, Multilingual Matters, pp. 1-9.

- Angelelli, Claudia V. (2012). “The Sociological Turn in Translation and Interpreting Studies.” Translation and Interpreting Studies, 7, 2, pp. 125-128.

- Anon. (2021). “Hong Kong’s Liberal Media are Under Pressure: The Communist Party in Beijing Wants to Tighten Controls.” The Economist, 19 June.

- Baker, Mona and Carol Maier (2011). “Ethics in Interpreter and Translator Training: Critical Perspectives.” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 5, 1, pp. 1-14.

- Beaton, Morven (2007). “Interpreted Ideologies in Institutional Discourse.” The Translator, 13, 2, pp. 270-296.

- Billiani, Francesca (2007). “Assessing Boundaries—Censorship and Translation.” In Francesca Billiani, ed. Modes of Censorship and Translation: National Contexts and Diverse Media. Manchester, St Jerome Publishing, pp. 1-25.

- Bourdieu, Pierre (1982). “Censure et mise en forme,” Ce que parler veut dire. Paris, Fayard, pp. 167-205.

- Boyatzis, Richard E. (1998). Transforming Qualitative Information—Thematic Analysis and Code Development. London, Sage Publications.

- Burroughs, William S. (1966). Naked Lunch. New York, Grove Press.

- Chang, Nam Fung (2008). “Censorship in Translation and Translation Studies in Present-Day China.” In Teresa Seruya and Maria Lin Moniz, eds. Translation and Censorship in Different Times and Landscapes. Cambridge, Cambridge Scholars Publisher, pp. 229-240.

- Chinese University of Hong Kong, The (2023). “BA in translation.” Available at: http://traserver.tra.cuhk.edu.hk/en/pro_student.php?cid= 2&id=22%20ment%20of%20Translation,%20The%20Chinese%20University%20of%20Hong%20Kong%20(cuhk.edu.hk) ment of Translation, The Chinese University of Hong Kong (cuhk.edu.hk) [consulted 17 June 2023].

- City University of Hong Kong, The (2023). “Major in Translation and Interpretation (TI).” Available at: https://lt.cityu.edu.hk/Programmes/334/2016/bati/requirement/lation (cityu.edu.hk) [consulted 31 August 2023].

- Clinton, Hilary R. (2003). Living History. New York, Simon & Schuster.

- Cohen, Louis et al. (2000). Research Methods in Education. 5th ed. London and New York, Routledge Falmer.

- Drugan, Joanna and Chris Megone (2011). “Bringing Ethics into Translator Training.” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 5, 1, pp. 183-211.

- Editorial Board (2019). “After 70 Years of Tyranny, Where does China Stand Today?” The Orange County Register, 1 October. Available at: https://www.ocregister.com/2019/10/01/after-70-years-of-tyranny-where-does-china-stand-today/ [consulted 26 February 2023].

- Fakharzadeh, Mehrnoosh and Hajar Dadkhad (2020). “The Influence of Religious Ideology on Subtitling Expletives: A Quantitative Approach.” Text & Talk, 40, 4, pp. 443-465.

- Fraser, Janet (1996). “The Translator Investigated.” The Translator, 2, 1, pp. 65-79.

- Gibbels, Elisabeth (2009). “Translators, the Tacit Censors.” In E. Ní Chuilleanáin et al., eds. Translation and Censorship: Patterns of Communication and Interference. Dublin, Four Courts Press, pp. 57-75.

- Göpferich, Suzanne (2012). “Tracing Strategic Behavior in Translation Processes: Translation Novices, 4th-semester Students and Professional Translators Compared.” In Séverine Hubscher-Davidson and Michal Borodo, eds. GlobalTrends in Translator and Interpreter Training: Mediation and Culture. London and New York, Continuum, pp. 240-266.

- Gross, Craig (2019). “Three Reasons Why Nobody Wants a ‘Christian’ Label.” Fox News, 29 March. Available at: https://www.foxnews.com/opinion/why-nobody-wants-a-christian-label [consulted 26 February 2023].

- Hang Seng University of Hong Kong (2023). “TRA2121 - Cultural Issues in Translation.” Available at: https://stfl.hsu.edu.hk/hk/your-study-plan-2/examples-of-elective-modules/?shortname=TRA2121&cid=247%E7%A8%8B%-E4%BE%8B%E5%AD%90%20|%20-%20The%20Hang%20Seng%20University%20of%20Hong%20Kong%20(hsu.edu.hk)程例子 | - The Hang Seng University of Hong Kong (hsu.edu.hk) [consulted 17 June 2023].

- Hong Kong Baptist University (2023). “Courses.” Available at: https://tiis.hkbu.edu.hk/en/undergraduate/courses/ses | Undergraduate | Study | HKBU - TIIS [consulted 17 June 2023].

- Hong Kong Watch (2023). “List of Imprisoned Protestors.” Available at: https://www.hongkongwatch.org/political-prisoners-database rotestors — Hong Kong Watch [consulted 26 February 2023].

- Human Rights Watch (2022). “Hong Kong: Children’s Book Authors Convicted.” Available at: https://www.hongkongwatch.org/political-prisoners-database [consulted 26 February 2023].

- Johnson, Karen E. (1992). “Cognitive Strategies and Second Language Writers: A Re-evaluation of Sentence Combining.” Journal of Second Language Writing, 1, 1, pp. 61-75.

- Khoshsaligheh, Masood (2018). “Seeking Source Discourse Ideology by English and Persian Translators: A Comparative Think Aloud Protocol Study.” International Journal of Society, Culture & Language, 6, 1, pp. 31-46.

- Koskinen, Kaisa (2020). “Tailoring Translation Services for Clients and Users.” In Erik Angelone et al., eds. The Bloomsbury Companion to Language Industry Studies. London, Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 139-152.

- Krings, Hans P. (1987). “The Use of Introspective Data in Translation.” In C. Faerch and G. Kasper, eds. Introspection in Second Language Research. Clevedon, Multilingual Matters, pp. 159-175.

- Künzli, Alexander (2004). “Risk Taking: Trainee Translators vs. Professional Translators. A Case Study.” The Journal of Specialised Translation, 2, pp. 34-49.

- Law, Wai-on (2009). Translation Students’ Use of Dictionaries: A Hong Kong Case Study for Chinese to English Translation. Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Durham. Unpublished.

- Lee, Tong Lee (2018). “The Identity and Ideology of Chinese Translators.” In Chris Shei and Zhao-Ming Gao, eds. The Routledge Handbook of Chinese Translation. Vol. 1. Routledge, pp. 244-256.

- Lefevere, André (1992). Translation, Rewriting, and Literary Fame. New York, Routledge.

- Lefevere, André (1998). “Translation Practice(s) and the Circulation of Cultural Capital. Some Aeneids in English.” In Susan Basnett, ed. Constructing Cultures: Essays in Literary Translation. Clevedon, Multilingual Matters, pp. 41-56.

- Lim, Chi-Yuk (2013). “A TAP Study on English-Chinese Translation Strategies and Mistakes.” Fu Jen Journal of Foreign Languages, 10, pp. 107-135.

- Lingnan University (2023). “Bachelor of Arts (Hons) in Translation.” Available at: Bachelor of Arts (Hons) in Translation - Department of Translation, Lingnan University (ln.edu.hk) [consulted 31 August 2023].

- Liu, Christy Fung-ming (2019). “Translator Professionalism: Perspectives from Asian Clients.” International Journal of Translation, Interpretation, and Applied Linguistics, 1, 2, pp. 1-13.

- Liu, Christy Fung-ming (2021). “Translator Professionalism in Asia.” Perspectives, 29, 1, pp. 1-19.

- López, Ana María Rojo and Marina Ramos (2014). “The Impact of Translators’ Ideology on the Translation Process: A Reaction Time Experiment.” MonTI. Monografías de traducción e interpretación, pp. 247-271.

- Lörscher, Wolfgang (1995). “Psycholinguistics.” In Sin Wai Chan and David E. Pollard, eds. An Encyclopaedia of Translation—Chinese-English/English-Chinese. Hong Kong, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, pp. 884-903.

- Meng, Zhou (2022). “Educating Translation Ethics: A Neurocognitive Ethical Decision-Making Approach.” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 16, 3, pp. 391-408.

- Munday, Jeremy (2007). “Translation and Ideology: A Textual Approach.” The Translator, 13, 2, pp. 195-217.

- Nesi, Hilary (2000). The Use and Abuse of EFL Dictionaries. Tübingen, Max Niemeyer Verlag.

- Nielsen, Jakob (1994). “Estimating the Number of Subjects Needed for a Thinking Aloud Test.” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 41, 3, pp. 385-397.

- O’Callaghan, Laura (2020). “Christian Persecution: Police Crackdown on ‘Illegal’ Church Services over Zoom.” Express, 14 April. Available at: https://www.express.co.uk/news/world/1268622/china-Christians-arrested-easter-Sunday-church-service-zoom-police-china-newshina news: Police CRACK DOWN on ‘illegal’ church services over Zoom | World | News | Express.co.uk [consulted 26 February 2023].

- Olalla-Soler, Christian (2019). “Bridging the Gap between Translation and Interpreting Students and Freelance Professionals. The Mentoring Programme of the Professional Association of Translators and Interpreters of Catalonia.” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 13, 1, pp. 64-85.

- Pan, Li (2014). “Mediation in News Translation: A Critical Analytical Framework.” In Dror Abend-David, ed. Media and Translation: An Interdisciplinary Approach. London, Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 247-266.

- Pan, Li (2015). “An Ideological Positioning in News Translation. A Case Study of Evaluative Resources in Reports on China.” Target, 27, 2, pp. 215-237.

- Petrescu, Camelia (2015). “Translating Ideology—A Teaching Challenge.” Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 191, pp. 2721-2725.

- Pressley, Michael and Peter Afflerbach (1995). Verbal Protocols of Reading: The Nature of Constructively Responsive Reading. Hillsdale, NJ, Erlbaum.

- Pym, Anthony (2001). “The Return to Ethics.” The Translator, 7, 2, pp. 139-154.

- Qin, Binjian and Meifang Zhang (2018). “Reframing Translated News for Target Readers: A Narrative Account of News Translation in Snowden’s Discourses.” Perspectives, 26, 2, pp. 261-276.

- Rodríguez de Céspedes, Begoña (2017). “Addressing Employability and Enterprise Responsibilities in the Translation Curriculum.” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 11, 2-3, pp. 107-122.

- Santaemilia, José, ed. (2005). Gender, Sex and Translation: The Manipulation of Identities. Manchester, St Jerome Publishing.

- Santaemilia, José (2008). “The Translation of Sex-Related Language: The Danger(s) of Self-Censorship(s).” TTR, 21, 2, pp. 221-252.

- Schnell, Bettina and Nadia Rodríguez (2017). “Ivory Tower vs. Workplace Reality.” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 11, 2-3, pp. 160-186.

- Setton, Robin and Alice L. Guo (2009). “Attitudes to Role, Status and Professional Identity in Interpreters and Translators with Chinese in Shanghai and Taipei.” Translation and Interpreting Studies, 4, 2, pp. 210-238.

- Sturge, Kate (2004). “The Alien Within”. Translation into German during the Nazi Regime. Munich, Iudicium.

- Tan, Zaixi (2015). “Censorship in Translation: The Case of the People’s Republic of China.” Neohelicon, 42, pp. 313-339.

- Tan, Zaixi (2019). “The Fuzzy Interface between Censorship and Self-Censorship in Translation.” Translation and Interpreting Studies, 14, 1, pp. 39-60.

- Tsai, Lynn and Da-hui Dong (2010). “Translator Cognition of Translation Ethics—A Comparison of Student and Professional Translators.” Studies of Translation and Interpretation, 13, pp. 191-217.

- Tymoczko, Maria (2002). “Ideology and the Position of the Translator: In What Sense is a Translator ‘In Between’?” In María Calzada-Pérez, ed. Apropos of Ideology: Translation Studies on Ideology-Ideologies in Translation Studies. Manchester, St Jerome Publishing, pp. 181-201.

- Wang, Jie and Yuanyuan Li (2019). “Incorporating Ethics-Awareness Competence in China Translator-Training Programme.” International Journal of Linguistics, Literature and Translation (IJLLT), 2, 4, pp. 164-170.

- Wolf, Michaela (2007). “Introduction: The Emergence of a Sociology of Translation.” In Michaela Wolf and Alexandra Fukari, eds. Constructing a Sociology of Translation. Amsterdam, John Benjamins Publishing, pp. 1-36.

- Wood, Charlie (2020). “Zoom Admits Calls Got ‘Mistakenly’ Routed through China.” Insider, 6 April. Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/china-zoom-data-2020-4 om Admits Data Got Routed Through China (businessinsider.com) [consulted 26 February 2023].

- Xu, Beina and Eleanor Albert (2017). “Media Censorship in China.” Council on Foreign Relations, 17 January. Available at: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/media-censorship-chinaedia Censorship in China | Council on Foreign Relations (cfr.org) [consulted 26 February 2023].

- Yu, Qing and Yunni Zhou (2018). “Translation of Gay Culture in Light of Review of the Chinese Versions of Brokeback Mountain.” Translation Quarterly, 19, pp. 1-17.

- Zhong, Yong (2017). “Global Chinese Translation Programmes: An Overview of Chinese-English Translation/Interpreting Programmes.” In Chris Shei and Zhao-Ming Gao, eds. The Routledge Handbook of Chinese Translation. London, Routledge, pp. 19-36.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Basic demographic information on the ten participants and their translated text type

Table 2

Chinese versions of the sensitive segments in Text A by four subjects

Table 3

Chinese versions of selected sensitive segments in Text B by three subjects

Table 4

Chinese versions of the negative segments in Text C by three subjects

Table 5

Chinese version of the sensitive segments in trial exercise by Henry

Table 6

Summary of the participants’ considerations and concerns about translating Texts A and B

Table 7

Triangulation of results in the pre-exercise interview and the retrospective report (participants’ words in quotations and italics)

Table 8

Details of Hong Kong translation undergraduate programs featuring topics related to “ideology” and/or “ethics” as of 2023

Table 9

Overview of the stages and corresponding activities of the proposed program

10.7202/037497ar

10.7202/037497ar