Résumés

Abstract

This paper focuses on the translation of Nigerian literature into French from the perspective of cultural diplomacy and as a cultural product (Flotow, 2007; Córdoba Serrano, 2013). It reviews Nigerian cultural diplomacy initiatives to determine if translation is highlighted as part of cultural export and as a means through which the Nigerian image and culture are promoted. Even though translation exchanges are not promoted by the Nigerian government, there is a field of translation of Nigerian texts into French. Data from a list of Nigerian novels translated into French between 1953 and 2017 provide contextual and historical information on the circulation of translations as well as on the works that are selected for translation into French.

Keywords:

- Nigerian literature,

- cultural diplomacy,

- translation,

- circulation,

- French language

Résumé

Le présent article propose une étude de la littérature nigériane traduite en français abordée sous l’angle de la diplomatie culturelle et comme un produit culturel (Flotow, 2007 ; Córdoba Serrano, 2013). Il examine les politiques culturelles nigérianes afin de découvrir si la traduction est considérée comme un produit culturel et comme un moyen de promotion de l’image et de la culture nigérianes. En dépit du fait que la traduction n’est pas promue par le gouvernement nigérian, le domaine de la traduction littéraire vers le français est loin d’être aride. L’analyse d’une liste d’oeuvres nigérianes traduites en français entre 1953 et 2017 fournit des informations historiques et contextuelles en ce qui concerne la circulation des traductions de même que des informations sur les oeuvres sélectionnées pour la traduction.

Mots-clés :

- littérature nigériane,

- diplomatie culturelle,

- traduction,

- diffusion,

- langue française

Corps de l’article

Introduction

Nigeria has about 500 living languages, with three of these, Igbo, Yoruba, and Hausa, constituting the major languages in the country (Umefien, 2019, p. 310). In a society as linguistically diverse as this, and in most countries of sub-Saharan Africa where English is the official language, some writers prioritize the use of English as a medium of literary works. English is considered for its “symbolic capital,” that is, its “degree of accumulated prestige, celebrity, consecration or honour” (Bourdieu, 1991, p. 7), and as being impartial, inasmuch as it favors no indigenous language. Authors choose to write in English not only to secure publication, but to further their literary and social capital through international recognition, to obtain a wider reading audience and a release from the perceived social stigma of ethnic or regional provincialism (Sullivan, 2001, p. 75).

Nigerian authors who write in English are able to publish internationally and gain world recognition; their works are thus accessible not only to an unlimited range of international critics, but also to translation into different languages, notably French. Given the fact that Nigerian literature is part of the so-called “minority literature” (Cavagnoli, 2014) and that French is not the only foreign language into which it is translated, one could question the logic of prioritizing the French language in this study. However, apart from the proximity of Nigeria to many francophone countries, a reality which heightens the importance of French and translation into this language in the country, the Nigerian government, under the defunct President, General Sani Abacha, declared French the second official language of the country in 1996. This decision triggered different projects in the education sector. Besides three major Centers of French Teaching and Documentation (CFTD) and a French language village, Badagry Lagos, which serve as in-house resources for Nigerian and other francophone teachers, other French Language Centres are spread across different institutions in Nigeria. The importance of French is similarly illustrated by the numerous graduate programs in Nigerian universities which have specializations in French Translation.

My study is motivated by the fact that, although Nigerian novels are inevitably translated into French, no research has focused yet on the study of translation as a cultural product or a tool for cultural diplomacy in Nigeria, nor examined the trends in the history of French publication of Nigerian literature. More specifically, this paper discusses the transfer of Nigerian literary production through its translation into French. It examines the translation into French of Nigerian literature in English as a cultural product and as a means of developing an international awareness of Nigerian culture and identity. As a cultural product, Nigerian literature in French translation sensitizes the target audience to the lived experiences of Nigerian people, thereby changing established worldviews and existing perceptions. Hence, it seems valuable to investigate the cultural policies that guide and facilitate such translation initiatives (if any) and to review Nigerian cultural diplomacy initiatives to find out if translation is highlighted as part of cultural export and as a means through which the Nigerian image and culture are promoted.

I will first go over the initial theoretical assumptions and scholarly literature that form the basis of my study. I will then review what constitutes Nigerian cultural diplomacy (from post-independence), the various initiatives and institutions of cultural transfer, with a focus on the transfer of literature, in an effort to assess the existence or non-existence, and functionality or non-functionality of translation within these exchanges. Finally, drawing from a list of novels translated into French, I will illustrate that, despite the lesser importance given to translation in Nigerian cultural policies, the translation and publication of Nigerian literature into French is ongoing. While this list of novels proves that Nigerian literature still finds its minimal space in French language and culture, the analysis provides important contextual and historical information on the origins and developments of translation of Nigerian literary texts in France, and the kinds of works that are selected for translation.

Theoretical Considerations

The perspective adopted in this paper is inspired by Luise von Flotow’s “Revealing the Soul of Which Nation: Translated Literature as Cultural Diplomacy” (2007) and María Sierra Córdoba Serrano’s Le Québec traduit en Espagne (2013), both of which highlight translated literature as a cultural product and as a means of cultural transfer. According to Flotow, few studies examine translation as a cultural product because this area of research deals with a type of government policy that funds more significant activities such as research chairs in literature at foreign universities, journeys abroad for orchestras or ballet companies, art exhibitions, and other more visible events related to culture.

the connections between the production of literary translations, the export of literature in translation as a cultural product, and so-called cultural diplomacy, have not been studied extensively, although literary histories do sometimes take account of the effects of translations as literary imports.

Flotow, 2007, p. 188

Reminiscent of Flotow, Córdoba Serrano affirms that culture encompasses traits that form a ready-made (prêt-à-porter) identity that is

ensuite intégrée dans un récit, avec lequel les gens du pays s’identifient et qui est susceptible de captiver les étrangers. Cette construction narrative de l’image de marque associée à un pays donné deviendra dès lors un mythe […] efficace pour rendre un pays concurrentiel sur le plan politique et économique sur la scène internationale.

2013, p. 44

Flotow’s and Córdoba Serrano’s reflections invite a similar discussion on translation as part of cultural diplomacy initiatives, an area that is not considered at all in “Nigerian Studies.” Consequently, for the purpose of this paper, I adopted a qualitative framework to study secondary materials, documents, policies, and cultural exchanges linked to the Nigerian mission in France, and determine if translation of literature is regarded as a tool for cultural diplomacy. The Nigerian Cultural Policy document published by the Institute for Development and International Relations/Culturelink (1996) was used to evaluate, if any, the government discourse on translation. I also made use of the information published on the website of the Nigerian Embassy in France to study cultural exchanges between Nigeria and France.

Furthermore, inspired by the works of Matthew O. Iwuchukwu (2005) and Françoise Ugochukwu (2006), I compiled a list of Nigerian novels translated and published in France between 1953 and 2017. WorldCat was extensively consulted to this end, given that it provides consistent and current data on Nigerian authors who are translated[2]. The Index Translationum was also used[3]. The Bibliothèque nationale de France (BNF) was consulted as well during fieldwork in France. To deepen data collection, individual websites and catalogues of French publishers were also consulted. Even though the catalogues of many French publishers were examined, the search was concentrated on the ones that had previously published a Nigerian work, and on those that have special collections on African literature. This is because some French publishers who publish Francophone African literature tend to publish the translated works of Anglophone African writers as well. For example, Actes Sud has a special collection called “Lettres Africaines” in which many African writers, including Nigerians, are published.

To gain further insight, French literary magazines such as LiRe, Le Magazine littéraire, Le Matricule des Anges, and Transfuge were also consulted given that they offer a review of new translations. Discussions with Nigerian professor Stella Omoni and Nigerian writer Uche Peter Umezurike, email exchanges with Nigerian writers Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani and Chigozie Obioma, and interviews with the editor of Actes Sud, Bernard Magnier, and Nigerian writer Akachi Adimorah-Ezeigbo, provided information both on new translations of Nigerian literature and the place of literature and cultural diplomacy in Nigeria[4].

For the purposes of this paper, Nigerian novel is defined as

any Nigerian literary work of imagination which is written by Nigerians for Nigerians; it discusses issues that are Nigerian and shares the same sensibilities, consciousness, worldview and other aspects of the Nigerian cultural experience.

Awoyemi-Arayela, 2013, p. 29

Hence, the novels compiled in the list mentioned above are written by authors who are Nigerian, whether they live in Nigeria or abroad, and whether their novels are published within or outside the country.[5] The decision to adopt this criterion based on nationality avoids the exclusion of writers who are of mixed race, who may be born and raised outside Nigeria, who do not reside in Nigeria, and whose novels may be set in Nigeria or elsewhere. These writers are mostly identified based on the country of their birth despite having another nationality and the fact that critics have placed their novels “squarely within the tradition of the Nigerian novel in English” (Cuder-Domínguez, 2009, p. 278). Brenda Cooper explains that

there is no clarity as to how to classify these writers–British? Canadian? Black? Simply Writers? There is a hesitation, a stutter, at the heart, at the start, where classification is incoherent and impossible. However, what characterizes all of them is that they are playing with the perplexities of juggling two continents; they struggle with the differences in power between these continents […].

2008, p. 52

Trish Van Bolderen also emphasizes the need to acknowledge the arbitrariness associated with a definition based on nationality (2014, p. 92). While recognizing the ambivalence that emanates even from a definition like the one I adopted, I underscore criteria that will not exclude a writer like Diana Evans[6] or her novel 26A, which is not only set in Nigeria but explores a core Nigerian Yoruba traditional belief in the supernatural power of twins or “ibeji.” With that said, the inclusion of such a writer in my corpus does not dispute any study or identification of the author as lying within another literary tradition or context.

Cultural Diplomacy

Sometimes regarded as a major category under which cultural diplomacy falls, public diplomacy

encompasses a wide and shifting terrain of processes and activities which can range from government actors speaking by way of the media to the people, or in people-to-people exchanges, such as an academic exchange.

Rodin and Topic, 2012, p. 10

Cultural diplomacy deals with the

exchange of ideas, information, art and other aspects of culture among nations and their peoples to foster cultural understanding. Cultural diplomacy creates awareness abroad of the cultural attributes of the home culture by developing interaction through cultural activities with which the projecting culture wants to be identified.

Hurn, 2016, p. 81

As soft power, cultural diplomacy, as it will be called here[7], is a substitute for the forceful communication of culture, ideologies, and institutions of a country. It is a subtle and peaceful means of intercultural communication. Brian Hurn (2016), Edward Nawotka (2013), and Sinisa Rodin and Martina Topic (2012) argue that cultural diplomacy highlights national heroes, literary icons, as well as high-profile authors and their works—both original and in translation. Besides, if book translation, as affirmed by Johan Heilbron (1999, p. 431), constitutes a particular category of cultural goods and a cultural world-system, the translation of Nigerian literature rightly falls within the scope of cultural diplomacy and hereby constitutes a decisive force of culture.

According to Iyorwuese Hagher (2015), a former Nigerian ambassador to Canada and a prolific writer and professor of Drama and Theatre, the concept of “culture” in Nigerian cultural policy relates to the art of winning the hearts and minds of others by attracting them through activities and exchanges that include arts, beliefs, ways of life, and customs. He states that it encompasses all forms of cultural and artistic expressions in Nigeria, especially literature, films, and art, and comprises all the traditions, history, values, beliefs, attitudes, and consciousness of the people—in short, the identity of a people. Recognizing that the reputation of a state is a factor that determines its diplomatic relationships with other countries, Nigeria strives to maintain its identity and reputation through various means of cultural diplomacy. However, is the transfer of literature part of these initiatives, or simply regarded as an element of cultural diplomacy?

Literature and Translation in Nigerian Cultural Diplomacy

In Nigeria, early post-independent initiatives of cultural diplomacy were far from highlighting literature let alone its translation. Ola Balogun explains that

[w]hen it became fashionable (soon after independence) to conceive of culture as a means of promoting national awareness and projecting the pride and dignity of black and African culture, some of those who were entrusted with the responsibility of bringing these concepts to life made nonsense of the whole idea by substituting a large-scale involvement in traditional dance as a substitute for valid cultural policies. The culmination of this absurd process was the humiliating experience by which the World Festival of Black and African Arts and Culture (FESTAC), which Nigeria hosted in 1977, was virtually converted into a mere display of traditional dancing on our side. Sad to say, this pernicious and thoroughly ridiculous fixation on traditional dances as our only form of cultural policy has continued virtually unabated until the present era.

1985, p. 88

Nigerian cultural policy documents show an effort to establish local institutions with a focus on the growth of Nigerian culture[8]. However, the absence of national identity or culture which has been observed by scholars like Joanna Sullivan (2001) results in policies that are controlled by individual objectives rather than national ones (Hagher, 2015). Wapmuk Sharkdam (2012) and Nurudeen Mimiko and Kikelomo Mbada (2014) have also condemned the same one-sided nature of Nigerian foreign policy which is heavily influenced by “domestic […] variables” such as the desires and decisions of the President and of foreign policy elite, the composition and orientation of the legislature, the weakness of public opinion, and, most importantly, religious and ethnic divides (Sharkdam, 2012, p. 143). Initiatives built on unbalanced policies impinge on the promotion of all facets of the multiple Nigerian identities which make up Nigeria’s national culture. Unlike a country like Canada, where national culture is seized upon as an instrument of national foreign policy (Flotow and Nischik, 2007, p. 3), Nigeria has yet to decisively articulate explicit initiatives to promote cultural diplomacy. The information provided on Nigerian cultural policy, as presented on the website of the Institute for Cultural Democracy, states:

Artistic and literary creation depends mostly on individual initiatives or on the local support. The Federal Fund for the Assistance to Arts and Drama offers assistance to artists in the provision of fellowships, study grants for travels and purchase of the needed materials. Other types of support available to artists or writers depend on cultural industries that are directly involved or influence artistic and literary creation.

Institute for Development and International Relations/Culturelink, 1996[9], n.p.

The statement above does not take significant responsibility for promoting and supporting various elements of culture, perhaps due to the challenges of offering support and promotion to all components of Nigerian culture. The Director General of the National Council for Arts and Culture, Segun Runsewe, confirmed this interpretation in an interview with Premium Times: when asked to explain what steps he is taking to promote Nigerian culture, he said that the Nigerian government recognizes the need to develop “cultural contents” (Alabi, 2017, n.p.). However, he emphasized the importance of understanding that “cultural contents are in different spells” and that Nigeria is “of the very strong eco-tourism cultural base” (ibid.). In other words, Runsewe claimed that Nigeria prioritizes aspects of culture that promote exotic, natural environments, and accompanying cultural features that are in need of conservation and protection. He also suggested that cultural products are disseminated and promoted depending on their considered importance. Obviously, the cultural content of literature, and especially of translation, does not emerge as an area of predilection, as it does not offer broad attractions and economic enticements, thus confirming Flotow’s observation cited earlier.

A telephone interview I had on April 20, 2017, with the Nigerian writer Akachi Adimorah-Ezeigbo, and discussion with the Nigerian poet Uche Peter Umezurike revealed that the “cultural industries” of the federal government that promote and subsidize literature remain a mirage. Individual initiatives in the areas of culture as well as the minimal support from the federal level when it comes to translation and other literary activities indicate that literary activities are not among the preferred cultural contents. The case of Bernth Lindfors and the archive of Nigerian literature[10] is illustrative of the situation. In the 1970s, Lindfors, well known for his work on Anglophone literature, and in particular Nigerian literature, attempted to acquire Amos Tutuola’s manuscripts for the University of Texas Humanities Research Center (Harrow, 2001). According to him, this project was very much opposed in Nigeria. The argument was that such an archive should be established in Nigeria since it is Nigerian intellectual property. Lindfors was informed by Nigerian intellectuals that there were plans to set up the archive at the University of Ife and to purchase the manuscripts from Tutuola himself. He finally gave in to the pressure and started advocating for the creation of an archive in Nigeria. In the end, the project did not see the light of day, as the University of Ife never came up with the needed funds. Lindfors revealed that after many years[11], Tutuola and his family sold the manuscripts and other personal belongings to the University of Texas. The purchase of Wole Soyinka’s manuscripts by an American university was similarly opposed by the Nigerian government, who purported that it would acquire the manuscripts for the substantial amount of 2 million naira (approximately 7000 CAD). This never happened either. Soyinka later sold his manuscripts to Harvard’s University Library. As observed by Lindfors, the failure of those projects was in part because the government exhibited “no interest in putting money into anything as arcane as literary manuscripts” (Harrow, 2001, p. 153).

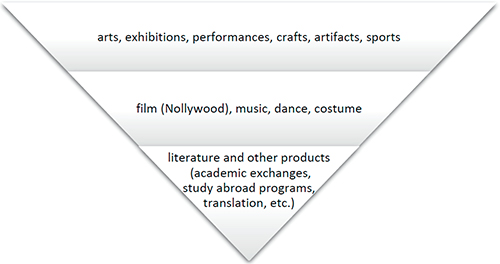

These instances show that literature has yet to find its place in the national echelon of culture even though the country highlights the exportation of its “cultural products” for the purposes of promoting its image and culture. The system of import and export of cultural products assumes a hierarchical categorization such that products found on the peak are highly favored. As shown in Figure 1 (below), artistic exhibitions and sports are favored. In his call for a better instrumentalization of all facets of culture for promoting the image of Nigeria, Hagher attests that “[a]part from the arts [and the traditional dances of course,] sport has been a major cultural diplomacy tool” (2015, p. 73).

Figure 1

Categorization of Nigerian cultural products

The same is affirmed in the Nigerian cultural policy, which states that cultural cooperation with western countries

is mostly based on the presentation of Nigerian arts and crafts, or Nigerian music to the western audiences, and on the transfer of knowledge on cultural institutions and activities from the West. […]. The Nigerian government backs this cultural exchange through exchange of artists, exhibitions, information materials, etc…

Institute for Development and International Relations/Culturelink, 1996, n.p.

This statement is both revealing and cautionary. The confirmation of precedence of certain cultural products over others reveals a stratified appreciation based on a gamut of unsubstantiated preferences. It is cautionary, as all parts of the culture should be promoted, even if not at the same level, provided none is neglected, as could be said in the case of literature and translation. More so, Segun Runsewe’s claim that Nigerian cultural initiatives focus on eco-tourism seems more of a verbalized action that an actualized one in Nigeria.

To further demonstrate that prerogative does not include the areas of literature and translation, there are a number of cultural programs targeting the promotion of arts around the world, some of which are sponsored by the Nigerian government. Although the precise kind of involvement or support the Federal government of Nigeria offers through the National Institute for Cultural Orientation is not mentioned, this parastatal of the Federal Ministry of Tourism, Culture and National Orientation claims to be actively involved in some listed cultural events; however, none of these events are literary. Having said this, it is important to admit that the categorization in Figure 1 does not convey the idea that there is a clear-cut and incontestable demarcation among the different categories, given that sometimes, music, for example, becomes part of various artistic exhibitions and has, in the words of Hagher (2015, p. 74), become a global phenomenon. Figure 1 aims to broadly portray the appreciation of some of the cultural products to clarify the place of literature and translation among them. Even though the Nigerian government describes writers as “cultural engineers,” there is yet no government program directed towards the support or dissemination of Nigerian literature and its translation. The reason, as expressed by Hagher, is that the supposed key players for the promotion of such programs, the intellectuals, are “not given a primary place in national life [and their] ideas do not matter very much” (2015, p. 92). Therefore, Nigeria could be said to pursue the exportation of culture for trade initiatives; however, it has yet to appreciate and invest in translation as a means of cultural transfer.

I have drawn attention to the status of literature and translation in Nigerian cultural diplomacy. Even though French has been the second official language of Nigeria since 1996, and there are cultural exchanges between Nigeria and France, Nigeria has yet to address the lack of interest in literature and the absence of a policy on translation.[12] In spite of this, I managed to document the existence of a thriving field of translation of Nigerian texts into French.

French Translation of Nigerian Novels (1953-2017)

As previously mentioned, I compiled a list of Nigerian novels and their French translations published in France. The data that follow are based on that list. The first ever translation of a Nigerian novel into French occurred in 1953, marking the beginning of the list[13]. At the time of writing this article, the list contained 80 novels originally written in English by Nigerian writers who live and publish within and outside Nigeria[14]. It also included three novels written in Yoruba and one in Igbo[15] which have been translated into French. Featuring 37 authors, the list contains detailed information on the original text: author’s name, title, publisher, publication year, and place of publication. The information provided for the French translations is similar: name of the translator, French title, publisher, publication year, and place of publication. Various trends were observed within the data collected with regards to the selection of the works to be translated[16].

Developments and Interruptions in Translation

The first translation of a Nigerian novel in France was Amos Tutuola’s The Palwine Drinkard. It was translated by Raymond Queneau, and published in 1953 by Gallimard, a year after its original publication. The second would take place 13 years later, in 1966. The novel was Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, which was originally published in 1958, eight years before its translation. The 13-year gap between these first two translations did not mean a gap in writing and publishing by Nigerian writers. A handful of Nigerian authors published in English between the late 1950s and the early 1960s. For instance, Achebe wrote other novels such as Arrow of God, No Longer at Ease, and A Man of the People by 1966. Also, Wole Soyinka published The Lion and the Jewel, The Road, The Swamp Dwellers, The Trials of Brother Jero, Strong Breed, and A Dance of the Forests. Cyprian Ekwensi, one of the most prolific Nigerian writers, wrote Burning Grass and Jagua Nana during the same period, while Tutuola published his second novel, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, in 1954. In 1966, the first Nigerian female author, Flora Nwapa, published Efuru. Like Gerald Moore (1973), Daniel Vignal acknowledges that soon after the publication of Tutuola’s first novel, Nigerian literature developed at a faster pace:

Depuis Amos Tutuola, plus de deux cents écrivains ont produit près de cinq cent cinquante romans, pièces de théâtre, recueils de nouvelles et de poèmes et durant ce quart de siècle, seuls quatre d’entre eux – appartenant tous à la première génération d’auteurs nigérians – purent sauter par-dessus la barrière linguistique qui les séparait encore du monde francophone.

1980, p. 50

Vignal further argues that after 1970, many Nigerian writers published works in Nigeria, Britain, and the United States that would have deserved the attention of translators and publishers in France. Some of these authors—whom Vignal calls “les grands oubliés”—are Obi Egbuna, Eddie Iroh, Isidore Okpewho, Adaora Lily Ulasi, Onuora Nzekwu, John Munonye, Christopher Okigbo, Kole Omotoso, Okechukwu Mezu, and Dilibe Onyeama. None of these authors were translated and published in France after 1966[17], although their works do not differ from those of other Nigerian authors who were translated, especially in terms of themes. Some like Nzekwu, Munonye, and Okpewho were household literary names who wrote about similar themes, ranging from colonial discourse, the human condition, tradition versus western modernity, identity, oral aesthetics, and intergenerational relationships. Furthermore, some of “les grands oubliés” have been recognized with local literary awards. Onyeama won the Niger Award for Literary Merit, for instance, and it was claimed that his novels garnered western attention and were best-sellers in the 1970s and 1980s (Ajeluorou, 2017). Hence, the years of non-translation of Nigerian literary texts do not imply the absence of literary works nor the absence of eligible ones.

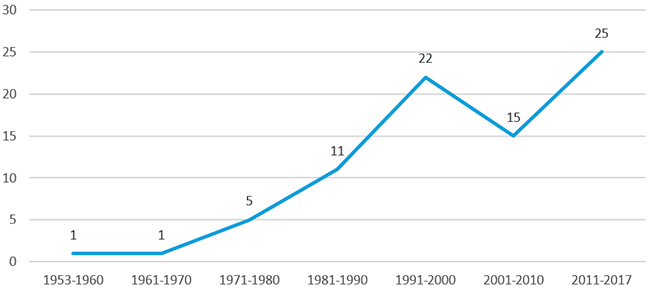

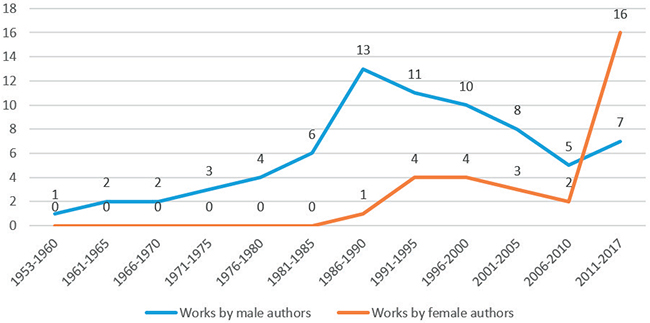

As shown in Figure 2, only one novel was translated in the 1960s. It should be noted that the decade of 1960-1970 was an eventful one for Nigeria—the independence of 1960 and the Nigerian-Biafra civil war from 1967 to 1970 are possible factors that may have shaped interests in the publication of Nigerian texts in France after 1970.

Figure 2

Number of Nigerian novels translated into French

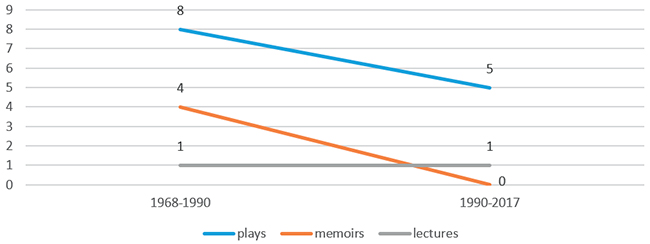

Indeed, the rhythm of publication picked up after the 1970s, and the 1980s proved to be among the most productive years in the history of the publication of Nigerian literature in France, with a total of 20 translated works (including plays). The award of the Nobel Prize in Literature to Wole Soyinka in 1986 marked the highlight of international recognition of Nigerian literary output. According to the data gathered from my list of translated novels, works written by Soyinka in the 1960s were mostly translated after he received the Nobel Prize. Out of the 20 texts (including plays) translated in the 1980s, 9 were authored by Soyinka. The 1990s witnessed a total of 29 works translated, with 7 being Soyinka’s. These fluctuations illustrate the impact of Soyinka’s Nobel Prize on the history of the translation of Nigerian literature in general. Figure 3 below helps to depict the translation of Soyinka’s plays and other works.There was also in the 1980s an interest in Tutuola, as his novel, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, written in 1954, was finally translated (by Michèle Laforest) and published by Belfond in 1988[18].

Figure 3

Translation of plays and other works by Wole Soyinka

The evolution of Nigerian literature in French translation shows that trends and developments in the Anglophone literary sphere influenced the selection of works to be translated. Wole Soyinka, who had published as early as 1954, was translated due to his recognition in the Anglophone world. This recognition led to the discovery, selection, and translation of other Nigerian authors by French publishers. While Soyinka’s works continued to be translated in that period, other writers, like Ben Okri and Ken Saro-Wiwa, were introduced into the French literary system, and L’Harmattan was credited with the first publication of a female Nigerian’s novel, Flora Nwapa’s Efuru, 22 years after its original publication in 1966.

Publishers of Nigerian Novels in French

My results show that Nigerian novels were published by different publishers in France. The data I compiled represent both smaller-scale publishers like Editions Silex/Nouvelles du Sud, Christian Bourgois, Dapper, Karthala, Les Escales, Galaade, Zulma, Titanic, and Hoëbeke, and major ones such as Gallimard, Albin Michel, and Actes Sud, with almost consistent financial growth, and who are among the top 15 French publishers as listed by Livres Hebdo. Some publish more Nigerian novels than others, in specialized collections such as the Actes Sud collection “Lettres Africaines.”

The research carried out for my thesis (Madueke, 2019) revealed that none of the Nigerian novels published was funded by a Nigerian program or institution; rather, some were subsidized by the Centre national du livre (CNL), an institution of the French Ministry of Culture and Communication which offers subsidies or grants to editors and translators. Applying for CNL grants requires that the publishing house, the translator, and the text to be translated meet certain conditions. These include copyright licenses, an appropriate distribution network in France, an independent professional translator, a translation contract, submission of a sample translation, and a copy of the publisher-translator contract. CNL bases its decisions on criteria such as the literary or artistic quality of the original work, its originality as an editorial project, reasons for translation, quality of the translation submitted, competence of the translator, specific difficulties of translating the work, commercial risks undertaken by the publisher, and the economic and commercial viability of the project (e.g., prices, target readership, and distribution). In 2012, for example, CNL received 438 applications, of which 279 were funded. In light of this process, and since some Nigerian novels benefited from CNL funding, it looks as if the quality of the originals and of the translations are given utmost importance by publishers.

Authors Selected for Translations

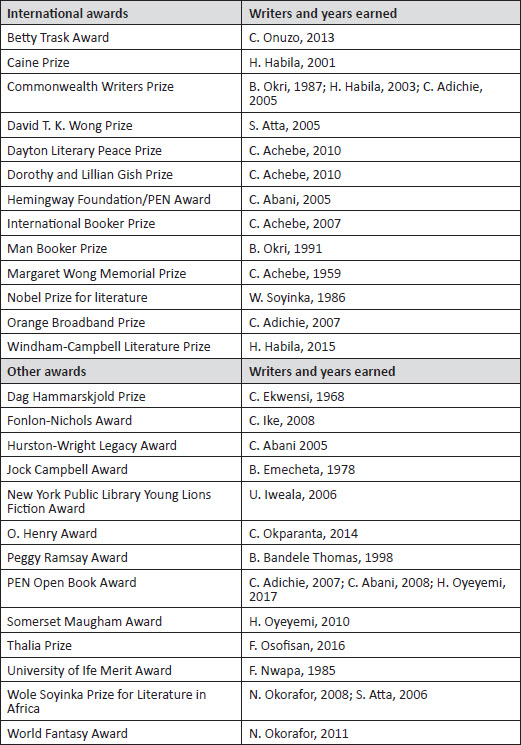

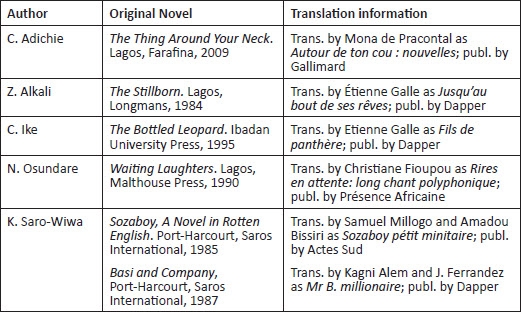

Literary prizes are a means through which Nigerian authors are recognized within and especially outside Nigeria; depending on the nature of the prize, authors can garner both local and international attention. Nigerian authors of different literary status are translated into French, and compete with writers from all over the world for some prizes. Most of them are internationally recognized like Chinua Achebe, Chimamanda Adichie, Elechi Amadi, Cyprian Ekwensi, Helon Habila, Ben Okri, Femi Osofisan, Ken Saro-Wiwa, and Wole Soyinka; they could be described as “afropolitains,” for lack of a better term[19]. Others, such as Sefi Atta, Igoni Barett, Simi Bedford, Ike Oguine, Nnedi Okorafor, and Helen Oyeyemi, may not be as prominent, but are equally recognized literary figures. A study of the biographies and bibliographies of the authors translated shows that they are recipients of at least one literary award (Table 1).

Table 1

Literary awards received by Nigerian writers translated into French

My analysis shows that the French publishers prioritize Nigerian authors who won international prizes, and do not necessarily put into perspective the Nigerian literary recognition standards when considering a work to be translated. Chinua Achebe, winner of the International Booker Prize in 2007, competed alongside nominees such as Margaret Atwood (Canada), Carlos Fuentes (Mexico), Ian McEwan (United States), and Salman Rushdie (India). Chibundu Onuzo, born in 1991 and the youngest Nigerian writer to be translated into French, received the Betty Trask Award in 2013 and was shortlisted and longlisted for other international awards among which are the Dylan Thomas Prize and the Commonwealth Book Prize. The interpretation that emerges is that the literary status of an author and the literary appreciation or recognition of a work occupy a primary position when French publishers choose an author to be translated, and this defines the overall kind of novels published in French. Although some Nigerian authors who have won international prizes are yet to be translated[20], it is indisputable that Nigerian authors are selected for translation based on their literary fame and, especially, their international reputation in the Anglophone literary world. The fact that these writers were first recognized with awards in Anglophone literary circles before they were translated into French proves that the domination of minor literatures by the so-called centers continues.

In the Nigerian scene, only a few prizes are available to writers who publish both at home and abroad. The most prestigious is the Nigerian Prize for Literature, which is worth 100,000 US dollars. Given that writers have difficulty getting published and do not benefit from foreseeable government subsidies, this prize is very competitive. There are a few other local literary prizes, but these do not necessarily project writers into the international literary space nor do they have significant monetary or literary prestige. Besides, some are prone to termination or reduction in monetary value as private stakeholders withdraw sponsorships. For example, the Association of Nigerian Authors, which awards various prizes including the Ken Saro-Wiwa Prize for Prose, J. P. Clark Prize for Drama, and Flora Nwapa Prize for Women (Creative) writing, experienced a setback because of the economic meltdown and the subsequent withdrawal of major sponsors (Ohai, 2017). This was also the fate of the All Africa Christopher Okigbo Prize for Literature, which is now extinct. Informal discussions with Nigerian writers indicated the reliance on these prizes: “Writers in Africa work hard to cover stories with very little resources. There is no money in it, because no one pays you until you win some kind of prize” confirmed Lidudumalingani Mqombothi, the South African writer who won the 2016 Caine Prize for African Writing, in an interview with The Guardian (Sunday, 2016, n.p.).

In the absence of resources and international recognition, some Nigerian writers remain enclosed in their so-called marginal space without the much-needed international attention that provides the potential for translation. Novels that are yet to be translated into French—among which Ayobami Adebayo’s Stay With Me, Teju Cole’s Every Day is for the Thief, and A.H. Mohammed’s The Last Days at Forcados High—may not have received international awards, but they remain well known. Additionally, female writers like Akachi Adimora-Ezeigbo, who have shaped the terrain of feminist literature and criticism in Nigeria and have been translated into other languages, are yet to find their way in French. As is the case for authors in many other countries, Nigerian writers rely heavily on literary prizes[21], especially international ones, not just for status, recognition, wider readership, prospective international publishing, and monetary reward, but also for the prospects of being translated. As long as these writers remain in the shadows, their chances of being translated are almost non-existent. Just like Quebecois writers (Córdoba Serrano, 2010a), most Nigerian writers published in France passed through the Anglophone literary centers by being recognized either in the US or the UK.

Translation of Novels Published in the West

Further analysis of the place of original publication shows that novels published outside Nigeria, that is, in the US or the UK, dominate the list of translations. In The World Republic of Letters, Pascale Casanova described the world literary space as being

organized in terms of the opposition between, on the one hand, an autonomous pole composed of those spaces that are most endowed in literary resources, which serves as a model and as a recourse for writers claiming a position of independence in newly formed spaces; and, on the other, a heteronomous pole composed of relatively deprived literary spaces at early stages of development that are dependent on political—typically national—authorities.

2004, p. 108

For the Nigerian writers who do not benefit from literary prizes or subsidies, being published in the US or the UK provides the major stepping stone into the world of “real” or “legitimate” literary spaces. Prior studies on Nigerian literary history and systems generally confirm that western literary criticism and recognition or canonization are indispensable to the general perception and reception of a Nigerian novel. The imposition of English on various cultural systems in Nigeria and its reification depict a postcolonial situation of imbibed canonicity where weak cultural capital equates with subordination in all its ramifications. The production of literature in Nigeria, a former British imperial state, is synonymous with questions of weak legitimization, thereby making western control of literature one of the most crucial topics for this study. Kenneth Harrow observed that at the heart of all African areas of cultural production lies the problem of decisions about important cultural works and control over their production, and “these decisions are inseparable from the cultures and intellectual industries of the West” (2001, p. 151).

Lindfors’ research on African writers and their reception in the sphere of anglophone literary criticism corroborates Harrow’s observation. Lindfors documented the number of times a writer appeared in detailed discussions of literary criticisms in print by literary scholars and critics, using a corpus of 40 African authors. The result revealed that “all the titles on the list have been published by multinational publishers” (Lindfors, 1995, p. 130). Ede Amatoritsero likewise identified factors such as the place of publication and the institutional position of a publisher in the metropolis (2013, p. 183) as playing a major role in the literary trajectory, recognition, or global canonical inclusion and exclusion of Nigerian texts, further explaining that “the local Nigerian literary prize does not fulfill usual goals of global visibility through active media promotions of winners and remains a local phenomenon” (ibid., p. 164). Conscious of such hegemonic internationalism under which the Nigerian literary system operates, and given that the literary status or fame considered by the French publishers aligns with the testimonies of western publishers, critics and readers, Nigerian books published in the West find their way more easily in translation than books published locally.

This can be illustrated with two examples. In 2015, Parrésia, a Nigerian-based publisher, put out Abubakar Adam Ibrahim’s Season of Crimson Blossoms. The mission of Parrésia to promote Nigerian books by publishing them at home and making them available to readers in Nigeria succeeded if we consider the fame garnered by Ibrahim’s novel in Nigeria: with its original theme of an unholy affair between a devout Muslim and a gang leader, it won the local Nigerian Prize for Literature. In spite of this recognition, Ibrahim’s novel has not yet been translated in French. Teju Cole’s[22]Every Day is for the Thief, published locally in 2015 by Cassava Republic, is another example. Although it captured the attention of western audiences and has been translated into German (2016), Spanish (2016), and Swedish (2015), it has not yet appeared in French.

Table 2

Some translated novels published locally in Nigeria

The visibility that accompanies western publishers and their transnational connections are more often than not absent for local publishers in Nigeria[23]. Loretta Stec buttressed this statement with the example of the British Heinemann African Writers’ Series that published leading names in African literature such as Chinua Achebe and Alex la Guma. According to Stec, since the edition and control of the African Writers’ Series took place in England, these writers were recognized by western audiences “largely because [they] were chosen to be published and reviewed, and acclaimed by [a] compan[y] with the capital and [international] prestige to do so” (1997, p. 142). Parrésia and Cassava Republic are some of the best-known Nigerian publishers[24]; however, publications by smaller houses are bound to face more issues when it comes to credibility and fame. A French publishing house like Gallimard[25] would more willingly translate a book endorsed by Simon and Schuster or Penguin Random House as opposed to an unknown publisher in Nigeria.

Among the authors listed in Table 2, Chimamanda Adichie and Ken Saro-Wiwa are peculiar cases. Adichie has won lots of critical acclaim and has been published in French by Gallimard, while Saro-Wiwa was an international figure, writer, and activist whose execution by the Nigerian government attracted international attention. As confirmed in an interview I conducted in Paris on June 7, 2017, with the French editor of Actes Sud, Bernard Magnier, who published the writer, Saro-Wiwa’s work was considered for translation because of the reputation of the author. In fact, Saro-Wiwa’s Sozaboy initially appeared in Nigeria in 1985 and was republished in 1994 in England by Longman, four years before the French version in 1998. The rights for translation and publication were probably passed through Longman England, and not the Nigerian publisher.

Apart from the already-established fact that Nigerian novels published in western countries are mostly translated and are more recognized internationally, other factors that could further reduce the possibility of translating locally published novels include the lack of agents or contacts in Nigeria, the inaccessibility of book promotion in Nigeria as well as the distance and difficulties of obtaining copyrights from Nigerian publishers. Individual publishers in France have different criteria for the selection of the works to be translated; however, as confirmed in my interview with Bernard Magnier, if an author publishes in Nigeria, it does not mean that his or her novel will not be translated into French and published in France.

Male vs. Female Authors in Translation

The frequency of translation of men and women writers shows that more men than women are generally translated, because early Nigerian writing was male-dominated. However, corresponding to the growing number of contemporary women writing, recent trends as shown from 2011 to 2017 in Figure 4 depict much progress in this area.

Figure 4

Translation of novels by male and female writers

As more women enter and are recognized in the international literary scene, more are being translated and published in French. Between 2011 and 2017, 16 novels by female writers were translated and published in France, while 7 were published by male writers. These translations have been published by Gallimard, Actes Sud, Panini Books (collection Eclipse), Les Escales, Galaade Editions, Hoëbeke, and Presses de la Cité, among others. Notwithstanding, these translations are not representative of Nigerian women involved in literary writing if we consider that some, like Adimorah-Ezeigbo[26], are common names in Nigerian literature and feminist writing, publish at home and have been translated, yet never in French.

Dominance of Literature Written in English

Most Nigerian novels published in French were originally written in English. Although I focus here on the translation of Nigerian literature written in English, the reference to the four indigenous language novels translated into French confirms the trends observed[27]. Olaoye Abioye’s translation of D.O. Fagunwa’s book Ogboju ode ninu igbo irunmale as Le preux chasseur dans la forêt infestée de démons, and of Ireke Onibudo as La fortune sourit aux audacieux are among the indigenous novels available in French. Olaoye is a Nigerian professor of French who was trained in France; his translations were published in Nigeria, in Lagos. Another example of a translation from an indigenous language into French is Françoise Ugochukwu’s rendering of Pita Nwana’s Omenuko. Unlike Olaoye’s translations, hers was published in France (by Karthala). Ugochukwu, who is originally French, was a professor of French in Nigeria. It could be argued that Olaoye’s and Ugochukwu’s translations only occurred because both translators were associated with the culture and language from which the original novels emanate.

As stated by Jean-Pierre Richard, there is an imbalance of languages from which African literatures are translated. Indeed, his research demonstrated that over a 60-year period (1945-2004), only 58 titles out of 613 African translations into German were originally written in a local African language such as Swahili (Richard, 2005b, p. 40). In the case of Nigeria, the insignificant number of indigenous language novels in French translation is linked to their peripheral position even within the Nigerian literary polysystem. According to Lindfors, the problem of the poor representation of indigenous language literatures on the international scene is explained in part by the insufficiencies of institutions promoting international awareness of local literatures and the unavailability of financial and logistic resources for promotion (1988, p. 222). Correspondingly, Alain Ricard, who has translated novels written in African languages and promoted African languages in French translation through the Institut Français de recherche en Afrique (IFRA) and the Centre national de recherche scientifique (CNRS), identifies the difficulty of editing and publishing, the condescending opinions of critics, and the problems of finding good translators of African languages as factors that mar any potential effort to translate and publish indigenous language literatures (2005, p. 58). While these factors impede the translation of indigenous language texts, my own research also reveals an underrepresentation of works written by some ethnic authors. For instance, unlike Yoruba and Igbo writers, Hausa writers—whether writing in English or in Hausa—did not appear in the data I compiled, except for Zainab Alkali, even though writers like Elnathan John and Labo Yari have produced notable works in English.[28] These discrepancies illustrate a few loops when it comes to the representative nature of Nigerian literature in French.

The Lack of Cultural Diplomacy Initiatives and its Impact on the Translation of Nigerian Literature in France

As we have seen, the absence of operational cultural diplomacy, policies, and programs did not hamper the translation of Nigerian literature in France. Rather, a budding number of translations that accounts for around 25% of all translations of African literature in France (Richard, 2005a; 2005b) positions Nigerian literature as the second most translated African literature in France. However, my analysis did illustrate the impact of such absence: selection criteria are determined and controlled entirely by foreign measures. In other words, foreign agents, factors, and standards determine the image of Nigeria that is presented to the French audience through the selected translated works[29]. The relative invisibility of Nigerian-published authors, the prioritization of writers with international recognition, and the underrepresentation of Nigerian writing from diverse ethnic groups and indigenous languages, are some of the gaps that could be filled by an involvement of the federal institutions and networks responsible for the dissemination of literature in translation.

In the past few years, Nigerian literature has been acclaimed for its emergent writers and new voices, as exemplified by the significant number of its productions that circulate all over the world. For example, New Books Nigeria, APortal of New Nigerian Creative Writing (Edem, n.d.) catalogued more than 50 new Nigerian novels published between 2015 and 2016, and more than 20 other publications including memoirs, essays and autobiographies. In comparison, according to my own research, only 9 Nigerian novels were translated and published into French from 2015 to 2017. As already observed, among the writers whose works were published within the aforementioned time frame, and who are yet to be translated and published in French, are writers of different status and literary capital, both within and outside Nigeria. Most of them published within Nigeria[30] or elsewhere in Africa, such as Toni Kan, Othuke Ominiabohs, Kola King, and Tony Nwaka. To sum up, according to my data, less than 15% of Nigerian literature would be represented in translation; in comparison with South Africa[31], a country half the size of Nigeria, this is almost insignificant.

According to Richard, the translation of South African literature represents more than three quarters of African literary works published in French, leaving the rest of the 20% to be shared between other African countries and Nigeria (2005a, pp. 12-13). Richard states that a more diverse and large number of new voices among black South Africans were introduced to French readers through “sustained public funding of literary journals” (ibid., p. 12). Agents such as George Lory, Cultural Advisor in the South African Ministry of Culture from 1990 to 1994, and Pierre Boyer, French ambassador to South Africa from 1984 to 1988, formed teams of enthusiasts[32] who ensured the translation of South African works in France. Such was their influence that they were able to control and determine the politics of publishing South African writers in French at the time. Richard (2005a) mentions neither the cultural programs nor specific ministries which oversee the “sustained public funding” of South African translations; however, the strategic position of these agents within the federal affairs of the country is instrumental to any effective exercise of power over translation. Further examples from previous studies on the translation of African literature into German and Quebec literature translated in Spain demonstrate how institutions or agents at the federal level may play a vital role in shaping the kind of literature which is transported to other countries through translation. Richard points out that there is a strong German policy which ensures the promotion, translation and publication of African literatures in German[33]. A comparison between German and French translations of South African literature within the same time frame (1945-2004) shows that 492 books from Africa were translated into German, and 165 into French. The number of German translations excludes French-speaking African writers.[34]

As of 2004, 45 Nigerian novels have been translated in France[35]. On the one hand, this confirms that the translation of Nigerian literature is ongoing despite a lack of structured programs for its promotion, and that it is significant when compared to all African translations in France. On the other hand, it becomes less significant when compared with South African literature, which had more than 100 titles at the time, or when compared to the myriad of Nigerian novels published as of 2004 that remain untranslated. Furthermore, the total number of Nigerian translations into French becomes less notable when compared to Quebec, whose population is around 4% of the Nigerian population, but boasts more than 76 texts translated in Spain, thanks to provincial and federal institutions and organizations, both in Ottawa and Madrid, whose participation and funding were instrumental (Córdoba Serrano, 2013, p. 64).

It goes without saying that the involvement of institutions of the Nigerian government in the promotion of literature would project more writers into the international limelight and increase the number of translations. Contrary to the case of Canada (Córdoba Serrano, 2010b, p. 47), Nigeria has yet to appreciate or regard literature or its translation as a tool for cultural diplomacy. The prioritization of other cultural products, as well as my discussions and interviews, indicate the non-existence of agency or institutions affiliated with the Nigerian government whose objectives or programs would be concentrated on projecting the translation of literature as a cultural product in France. As reinforced by the observations of scholars already cited (Sharkdam, 2012; Hagher, 2015; Mimiko and Mbada, 2014), the root of the problem lies in the fact that Nigeria has yet to prioritize and orient its foreign policies toward cultural diplomacy. Hence, its literature in French translation remains at the mercy of the agents and institutions of the French cultural system.

Notwithstanding the above, even in countries with more functional cultural programs, the process of exporting literature depends more “on the participation” and “vagaries of public taste” of the target culture, as demonstrated by Flotow (2007, p. 187 and 197). With regard to Nigeria, many factors mitigate against the realization of such objectives of cultural diplomacy. Apart from the obvious position of the country as the “dominated” in relation to imperial France, internal problems such as multiethnic upheavals, disputed nationalism, and poor management of funds impede potential measures aimed at promoting its “national” literature. This might be a limitation of using Flotow’s concept of “cultural diplomacy” in my study, since not all nations can afford to subsidize cultural products like Quebec, and countries like Nigeria are not built on a strong national identity model. Besides, this concept, in relation to translation, is a relatively new development in the US and the UK (Flotow, 2007). It may not be expected that cultural diplomacy or the exporting of culture for the purposes of image promotion would have taken root in Nigeria.

However, recent developments indicate that a dynamic form of Nigeria’s cultural diplomacy is emerging from the private sector, as banks, oil companies and other private institutions are beginning to sponsor cultural and artistic programs (Hagher, 2015, p. 74). Whether the translation of literature (into French) will be potentially prioritized as a cultural product by these institutions remains an open question. As in any country with many checkered legacies, or a broken national identity, a country divided by linguistic and ethnic conflicts, or still developing, with a weak legitimizing power for its cultural productions, the translation of Nigerian literature will continue to be controlled by western definitions, if a way is not found that develops structured and functional programs specifically created for the promotion of literature. For example, could the creation of collaborative translation and co-translation initiatives between French and Nigerian agents (publishers, reviewers, translators, and even writers) not introduce to the French audience the changing faces of Nigerian literature as it is commonly described?

Conclusion

This paper has shown that the transfer of literature through translation has a negligible presence in Nigeria’s cultural diplomacy. Despite ongoing interactions between Nigeria and France, translation does not appear in national discussions and federal policies. Key players who determine the products which are at the heart of Nigerian cultural diplomacy overlook literature and translation, prioritizing other elements of culture and trade. However, the terrain of French translation of Nigerian texts is far from being arid, and different factors were identified as for the kind of books that are translated. Explicable and inexplicable gaps in translation were noted, as well as recent progress in the translation of female writers, the involvement of major and minor publishing houses in the translation and publication, the virtual absence of indigenous language literatures, but most especially, the predominance of works in English that were originally published outside Nigeria. It is still for the most part the characteristics of Nigerian literature in English—controlled by western standards of canonization—that influence its translation into French. We have seen that most of the recognized works of Nigerian literature in English published abroad are easily discovered, translated and published by French agents and publishers. The fact that Nigerian literature as it is recognized in the international realm and translated in France is not representative of the works published in Nigeria implies a gap that may yet be partially filled by the creation of sustainable cultural programs and institutions whose special objective would be promoting literature in general. In fact, until literature and translation are prioritized as national cultural products, a diverse representation of Nigerian literature in French will be far from really attained[36].

Parties annexes

Biographical note

Sylvia I. C. Madueke recently completed her PhD in French Language, Literatures and Linguistics at the University of Alberta. Her thesis focused on the history and strategies of translating and publishing selected Anglophone African literary texts in France. Her research interests include cultural translation, African women and translation, and diversity in literary publishing and translation. Her latest publication is a study of the French translation of Chimamanda Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun.

Notes

-

[1]

This paper is an aspect of my PhD thesis (Madueke, 2019), which was partially funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

-

[2]

Since WorldCat provides information on the different languages or editions of a work, a title search was performed to determine if a specific work is translated.

-

[3]

Although statistical records provided by the Index Translationum contain important information about authors translated in a particular country and the evolution of translation in a given country, data regarding Nigeria are outdated and poor. Indeed, Index Translationum does not provide a significant list of Nigerian authors who have been translated into French.

-

[4]

These discussions and interviews were conducted as part of the fieldwork for my PhD project (Madueke, 2019). They took place between January 2017 and December 2017. Specific references will be given in the body of this paper when an interview is mentioned.

-

[5]

Such a delimitation based on national belonging might bring up questions concerning the definition of a Nigerian writer, considering that there may be immigrants in Nigeria who write about their Nigerian experience. However, in the course of my study, I have not identified any novel that was written by a writer who could be said to belong to this category.

-

[6]

Diana Evans is also identified as a British novelist and critic.

-

[7]

Flotow and Nischik observe that terms like “public diplomacy” and “cultural diplomacy” have been used interchangeably (2007, p. 12).

-

[8]

Administrative structures and cultural parastatals such as the National Council for Arts and Culture, the National Gallery of Art, the National Commission for Museums and Monuments, the National Theatre and the National Museum have been established by the Nigerian government to promote cultural expressions. For more information on cultural policy, articulations and institutions, see Institute for Development and International Relations/Culturelink (1996).

-

[9]

To my knowledge, this document has yet to be updated. The original document titled “Cultural Policy for Nigeria” was produced by the Federal Republic of Nigeria in 1988.

-

[10]

For details, see Harrow (2001).

-

[11]

A precise number of years was not specified in Harrow (2001).

-

[12]

The Nigerian cultural policy states that cultural cooperation is carried out on the basis of signed agreements, either bilateral or multilateral, such as the 2016 cultural agreement with France. The Nigerian foreign mission in France produces online and printed materials to promote Nigeria’s image. According to the mission statement, the guidelines for cultural, educational, scientific, and technical exchanges between Nigeria and France focus on teaching French language, cultural diversity, higher education, and research, as well as strengthening governance and the rule of law. Initiatives such as the Institut Français in Nigeria, The Poets Stream, Dancing City, Win Environment, and New Horizons, which promote concert series to celebrate cultural and creative, musical and artistic exchanges between Nigerian and French artists, are funded by the French government. The Nigerian government also organizes the Nigerian Creative Arts Exchange in France to showcase the traditions, sights and sounds of Nigeria. See Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères, République française (2019), Nigeria Embassy Paris France (2018) and Premium Times (2016).

-

[13]

Given that it is a lengthy document, the full list is not included in this article.

-

[14]

While the data presented here are concentrated on novels, the full list also includes 16 plays, 3 poems and 4 memoirs written in English and translated into French.

-

[15]

The Igbo novel, Omenuko, was translated into English before the French translation appeared. It is not clear if the translator, who is French but has also worked with the Igbo language, translated from the Igbo or the English version.

-

[16]

This paper is not intended as a case study of given novels. General references to specific information on the translation processes and politics will be made only when necessary, based on case studies carried out in my PhD thesis (Madueke, 2019).

-

[17]

There are many possible reasons why these writers are not translated: the thematic appeal of the works, the style of the individual author, and the absence of policies in Nigeria for the promotion of literary works for translation.

-

[18]

This is interesting because his first novel was translated and published by Gallimard immediately after the original. The second one had yet to be considered for translation by Gallimard or another publisher in France 34 years after its original publication. The question of Gallimard’s lack of further interest in Tutuola’s works, despite solicitations by Tutuola’s agent, is discussed in my thesis (Madueke, 2019).

-

[19]

The term “afropolitain,” coined by Taiye Selasi (2005), remains controversial among academics, but serves as a useful descriptor for the most visible or recognized modern Nigerian writers. It refers to writers who are born in Nigeria but have western education and enjoy western recognition. With international mobility, and being citizens of at least one western country, they use English as their writing language.

-

[20]

Such as Lesley Nneka Arimah (What It Means When a Man Falls From the Sky), who won the Kirkus Prize worth 50,000 US dollars in 2017, and Irenosen Okojie (Butterfly Fish), who won the Betty Trask Award worth 5,000 euros in 2015.

-

[21]

As per the information gathered from my discussions with the writers.

-

[22]

It should be noted that Cole’s novel Open City, printed in 2011 by Penguin Random House UK, was published in French by Denoël. This confirms why examining the individual processes of translation of Nigerian texts is important.

-

[23]

This statement does not refer solely to the two Nigerian publishing houses mentioned here, since they are among the most notable in Nigeria.

-

[24]

Parrésia was founded in 2012 by Azafi Omoluabi Ogosi and Richard Ali; Cassava Republic was founded in 2006 by Bibi Bakare-Yusuf and Jeremy Weate.

-

[25]

Gallimard is known for its prestigious nature and publication of internationally acclaimed writers. Apart from Tutuola and Adichie, Gallimard has not published other Nigerian writers.

-

[26]

I recently co-translated Adimorah-Ezeigbo’s short story Reflections from English to French.

-

[27]

I did not research in detail programs that may be targeted towards the translation of indigenous language novels of Nigeria.

-

[28]

Elnathan John’s Born on a Tuesday, originally published in 2015, was recently translated into French, and published in January 2018 by Métailié. It was not yet published in French at the time of this study.

-

[29]

Despite this absence and even though the themes prioritized by these external publishing houses may be a factor, a cursory study of the plots of the translations shows it is rather various themes that are the measure for being translated.

-

[30]

I acknowledge the changing face of Nigerian publishing: the emergence of publishers like Cassava Republic, Parrésia, and Kachifo (Farafina) have introduced a rather thriving industry by acquiring publication rights for titles published in the West and republishing them in Nigeria, thus making these works available to the local Nigerians. These publishers also introduce new voices through the publication of debut works. In 2017, Cassava Republic opened a branch in the UK.

-

[31]

Even though South Africa is mentioned here, I recognize that there are internal imbalances given the over-representation of the white writers of the country in translation (Nadine Gordimer, Andre Brink, J.M. Coetzee, and Breyten Breytenbach), and hence a minimal number of black South African writers. Richard (2005a) notes that because of the apartheid regime and its dismantling, South Africa attracted the attention of the international community, especially of France, where many journals dedicated special issues to South Africa and its literature.

-

[32]

These were also translators who are described by Richard as “militants-traducteurs” because of the various changes they brought to the history of South African literature in French translation (2005a, p. 16). My own study did not allow me to observe a similar phenomenon, since there is no Nigerian translator who has translated any of the texts of my list that were published by the French publishers.

-

[33]

Such a policy according to Richard is absent in France. Having said this, I reiterate that my study is focused on the initiatives that are available in or provided by the source culture for the promotion of its literature through translation.

-

[34]

The total number of translations of the period is 613 according to Richard (2005b).

-

[35]

One cannot but wonder: if South Africa dominates the scene, and Nigeria takes the majority of the rest of titles translated in France, why are other countries of Africa so poorly represented?

-

[36]

In this paper, cultural diplomacy and cultural programs are considered as representing only one of the various factors that will project Nigerian literature in its diversity, whether published at home or abroad, written in English or in ethnic languages, into the translation realms. The description of Nigerian literature in translation would also require, for example, a succinct analysis of the dephasings in Nigerian literature to account for specific time frames in publications as well as thematic predilections in translations vs in original publications. Case studies of translated works would illuminate other factors that determined their translations and publications.

Bibliography

- Ajeluorou, Anote (2017). “Dillibe Onyeama revives occult novels of the 80s.” Guardian Arts, 22 February. [https://guardian.ng/art/dillibe-onyeama-revives-occult-novels-of-the-80s/].

- Alabi, Priscilla (2017). “Why We Won’t Allow Abuja Arts Village Run 24 Hours Daily Runsewe.” Premium Times, 15 July [https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/236905interview-wont-allow-abuja-arts-village-run-24-hours-daily-runsewe.html].

- Amatoritsero, Ede (2013). The Global Literary Canon and Minor African Literatures. PhD dissertation. Carleton University. Unpublished.

- Awoyemi-Arayela, Taye (2013). “Nigerian Literature in English: The Journey so Far?” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention, 2, 1, pp. 29-36.

- Balogun, Ola (1985). “Cultural Policies as an Instrument of External Image-Building: A Blueprint for Nigeria.” Présence Africaine, 133-134, pp. 86-98.

- Bourdieu, Pierre (1991). Language and Symbolic Power. Ed. by J. B. Thompson, Trans. Gino Raymond and Matthew Adamson. Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

- Casanova, Pascale (2004). The World Republic of Letters. Trans. Malcolm DeBevoise. Cambridge, Harvard University Press.

- Cavagnoli, Franca (2014). “Translation and Creation in a Postcolonial Context.” In S. Bertacco, ed. Language and Translation in Postcolonial Literatures. Multilingual Contexts, Translational Texts. London and New York, Routledge, pp. 165-179.

- Cooper, Brenda (2008). “Diaspora, Gender and Identity: Twinning in Three Diasporic Novels.” English Academy Review, 25, 1, pp. 51-65.

- Córdoba Serrano, María Sierra (2010a). “Translation as a Measure of Literary Domination: The Case of Quebec Literature Translated in Spain. (1975-2004).” MonTi, 2, pp. 249-282.

- Córdoba Serrano, María Sierra (2010b). “Traduction littéraire et diplomatie culturelle. Le cas de la fiction québécoise traduite en Espagne.” Globe : revue internationale d’études québécoises, 13, 1, pp. 47-71.

- Córdoba Serrano, María Sierra (2013). Le Québec traduit en Espagne. Analyse sociologique de l’exportation d’une culture périphérique. Ottawa, Les Presses de l’Université d’Ottawa.

- Cuder-Domínguez, Pilar (2009). “Double Consciousness in the Work of Helen Oyeyemi and Diana Evans.” Women: A Cultural Review, 20, 3, pp. 277-286.

- Edem, Fifi (n.d.). New Books Nigeria.A Portal of New Nigerian Creative Writing. [https://newbooksnigeria.wordpress.com/].

- Flotow, Luise von (2007). “Revealing the ‘Soul of Which Nation?: Translated Literature as Cultural Diplomacy.” In P. St-Pierre and P. C. Kar, eds. Translation Reflections, Refractions, Transformations, Amsterdam, John Benjamins, pp. 187-200.

- Flotow, Luise von and Reingard M. Nischik, eds. (2007). Translating Canada. Charting the Institutions and Influences of Cultural Transfer: Canadian Writing in German/y. Ottawa, University of Ottawa Press.

- Hagher, Iyorwuese (2015). Diverse but Not Broken. National Wake-up Calls for Nigeria. Singapore, Strategic Book.

- Harrow, Kenneth (2001). “Bernth Lindfors and the Archive of Nigerian Literature.” Research in African Literatures, 19, pp. 147-154.

- Heilbron, Johan (1999). “Towards a Sociology of Translation: Book Translations as Cultural World System.” European Journal of Social Theory, 2, 4, pp. 429-444.

- Hurn, Brian (2016). “The Role of Cultural Diplomacy in Nation Branding.” Industrial and Commercial Training, 48, 2, pp. 80-85.

- Institute for Development and International Relations/Culturelink (1996). Cultural Policy in Nigeria. [http://www.wwcd.org/policy/clink/Nigeria.html].

- Iwuchukwu, Matthew O. (2005). “Francophonie et production littéraire nigérienne en traduction française : dialogue des cultures.” Neohelicon, 32, 2, pp. 521-527.

- Lindfors, Bernth (1988). “Africa and the Nobel Prize.” World Literature Today, 62, 2, pp. 222-224.

- Lindfors, Bernth (1995). “Desert Gold: Irrigation Schemes for Ending Book Drought.” In B. Lindfors, ed. Long Drums and Canons. Trenton, Africa World Press, pp. 123-135.

- Madueke, Sylvia I. C. (2019). Translating and Publishing Nigerian Literature in France (1953-2017): A Study of Selected Writers. University of Alberta, PhD dissertation. [https://era.library.ualberta.ca/items/7503d30a-f3f8-4bca-89d3-87a70d3b3e4c/view/ba011970-529c-4a31-a2d2-d93e781086cf/Madueke_Ijeoma_C_201812_PhD.pdf].

- Mimiko, Nurudeen and Kikelomo Mbada (2014). “Elite Perceptions and Nigeria’s Foreign Policy Process.” Alternatives Turkish Journal of International Relations, 13, 3, pp. 41-54.

- Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères, République française (2019). “Nigeria.” France Diplomatie. [https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/country-files/nigeria/].

- Moore, Gerald (1973). “La littérature en langue anglaise : une nouvelle vigueur d’expression forgée dans les années d’épreuve.” Le Monde diplomatique. Décembre, p. 42. [https://www.monde-diplomatique.fr/1973/12/MOORE/31999].

- Nawotka, Edward (2013). “What Role Can Literature Play in Cultural Diplomacy?” Publishing Perspectives. [https://publishingperspectives.com/2013/08/what-role-can-literature-play-in-cultural-diplomacy/].

- Nigeria Embassy Paris France (9 May 2018). Nigerian Creative Arts Exchange. [https://www.nigeriafrance.com/nigerian-creative-arts-exchange/].

- Ogunlesi, Tolu (2015). “A New Chapter in Nigeria’s Literature: Writers Are Gaining International Attention.” Financial Times, October 6. [https://www.ft.com/content/2aaa2182-670c-11e5-97d0-1456a776a4f5].

- Ohai, Chux (2017). “Recession: Chevron Withdraws Funding for ANA Prize.” Punch, Feb. 21. [https://punchng.com/recession-chevron-withdraws-funding-ana-prize/].

- Premium Times (2016). “Nigeria, France Sign 5 Bilateral Agreements.” Premium Times, 15 May. [https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/more-news/203427-nigeria-france-sign-5-bilateral-agreements.html].

- Ricard, Alain (2005). “La publication de la littérature africaine en traduction.” Les Cahiers de l’IFAS, 6, pp. 58-62.

- Richard, Jean-Pierre (2005a). “L’autre source : le rôle des traducteurs dans le transfert en français de la littérature sud-africaine.” Les Cahiers de l’IFAS, 6, pp. 12-23.

- Richard, Jean-Pierre (2005b). “Translation of African Literature: A German Model?” Les Cahiers de l’IFAS, 6, pp. 39-44.

- Rodin, Sinisa and Martina Topic (2012). Cultural Diplomacy and Cultural Imperialism: European Perspective. Frankfurt, Peter GmbH.

- Selasi, Taiye (2005). “Bye-Bye Babar (or: What is an Afropolitan).” The Lip Magazine, March 3. [http://thelip.robertsharp.co.uk/?p=76].

- Sharkdam, Wapmuk (2012). “The Changing Role of Non-State Actors in Foreign Policy Making, with Reference to Nigeria.” The IUP Journal of International Relations, 6, 4, pp. 7-18.

- Stec, Loretta (1997). “Publishing and Canonicity: The Case of Heinemann’s ‘African Writers Series’.” Pacific Coast Philology, 32, 2, pp. 140-149.

- Sullivan, Joanna (2001). “The Question of National Literature for Nigeria.” Research in African Literatures, 32, 3, pp. 71-85.

- Sunday, Frankline (2016). “‘There’s no Money in it’: Prize-winning African Author Says Writers must Diversify to Survive.” The Guardian, 10 July. [https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/jul/10/prize-winning-caine-prize-african-author-writers-must-diversify-to-survive].

- Ugochukwu, Françoise (1995). “Thèses et mémoires présentés en français sur le Nigéria : bibliographie (1963-1993).” Journal des africanistes, 65, 1, pp. 123-142.

- Ugochukwu, Françoise (2002). “Nigerian Literature in France. A Survey and Assessment of Fifty Years of French Interest in Nigeria and Its literature.” In T. Falola, ed. Nigeria in the Twentieth Century. Durham, Carolina Academic Press.

- Ugochukwu, Françoise (2006). “La littérature nigériane en traduction et son impact.” Ethiopiques, 77, pp. 151-171.