Résumés

Abstract

The debate on what cultural translation as an analytical and political tool can offer has sparked much discussion in translation studies as well as in the fields of anthropology, literature, and cultural studies. To a lesser degree, some museum studies scholars have likewise evoked the notion of translation to address the ethics of representing culture in and across differences. This article expands on these discussions by evaluating whether a translational lens can serve to rethink the display of African material culture in museums. Through an analysis of the textual, spatial, and visual elements of the permanent African exhibition at the Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac (MQB) in Paris, France, I argue that though the MQB claims that it seeks to foster cultural dialogue, the “translations” of its African collection tend to reproduce the museum’s norms of meaning-making, rather than the norms of the non-European cultures it presents. However, I also suggest that by approaching its task as one of multimodal translation, the MQB could reshape its museographic language to reflect ways of making meaning that are more evenly in dialogue with ways of making meaning from the objects’ contexts of origin.

Keywords:

- cultural translation,

- Musée du quai Branly,

- African art,

- ethnography exhibitions,

- intermedial translation

Résumé

L’usage de la « traduction culturelle » comme grille d’analyse suscite de nombreux débats, tant en traductologie que dans le champ de l’anthropologie, des études littéraires et des études culturelles. De même, si la traduction est moins souvent étudiée en muséologie, certaines études qui s’efforcent de penser la représentation culturelle et la différence culturelle à travers une éthique fondée sur la traduction. Ainsi le présent article enrichit-il les recherches actuelles afin de déterminer si la métaphore de la traduction culturelle permet de repenser l’exposition de la culture matérielle africaine. S’appuyant sur une analyse du langage textuel, spatial et visuel de la partie africaine de l’exposition permanente du Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac (MQB) à Paris, cet article montre que dans sa présentation des oeuvres, le MQB favorise les normes épistémologiques propres à la muséologie occidentale en occultant celles des cultures d’origine. Néanmoins, l’étude suggère qu’en visant une traduction multimodale, le MQB serait à même de transformer son langage muséographique afin d’ouvrir pour les visiteurs, dans le rapport des objets exposés à l’espace muséal, l’accès à des enjeux épistémologiques équivalents à ceux dont ils étaient chargés dans leur contexte d’origine.

Mots-clés :

- traduction culturelle,

- Musée du quai Branly,

- arts africains,

- expositions ethnographiques,

- traduction intermodale

Corps de l’article

It was fate. Yes, fate that the book I had with me was a novel by my great-grandfather, a text you couldn’t read because my great-grandfather had put a permanent ban on any of his works being translated into English, Russian, or French. He was adamant that these three are languages that break all the bones of any work translated into them.

Oyeyemi, 2016, pp. 85-86

In this article, I ask whether the exhibition of cultural objects from Africa in European museums produces a kind of translation that breaks the bones of their objects. In other words, does the museum’s display result in a loss of the objects’ agency: their ability to move, to produce effects, to act on their surroundings in novel ways? If translating such objects into the language of the museums does indeed lead to bone-breaking, can the objects be invited to, instead, transform the museum’s bones?

The question of translation—its processes and outcomes—in museums is a political question, given that the modern museum in Euro-American societies initially emerged as a strategy of the nation-state for producing a self-regulating, rational citizenry (Duncan and Wallach, 1980; Bennett, 1995; Bal, 1996;). Furthermore, museums are deeply involved in processes of defining, classifying, and modeling cultural identities and collective values (Karp and Lavine, 1991; Karp et al., 1992; Clifford, 1997; Karp et al., 2006). Museums, in other words, are institutions that play a significant role in both representing cultural difference and arbitrating ways of living those differences. These institutions—which are often financed if not governed by the state—have, over the past few decades, been criticized for producing Eurocentric, heteropatriarchal, elitist, and colonialist ideologies through their collecting and representing practices (Hooper-Greenhill, 1992; Hein, 2000; Macdonald, 2003; Acuff and Evans, 2014). They have faced increasing pressure to diversify their representation of social and cultural groups, and make the museum a space accessible to more publics (Bennett, 1995; Bal, 1996; Aldrich, 2005; Dibley, 2005). Addressing these political demands is particularly thorny, as James Clifford argues, for museums that house “non-Western objects for which contestations around (neo)colonial appropriation and cross-cultural translation are inescapable” (2007, p. 9).

This article thus asks: what might translation as an analytical tool reveal in museum practices—specifically in regard to the representation of non-Western cultures in Western centers—and what might a case study of museum practices as translational ones contribute to the debate on the politics of cultural translation, inside and outside of museums? Taking the example of France’s Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac (MQB), I will argue that the MQB’s museographic grammar emphasizes visual and textual literacy as the primary modes of meaning-making, at the expense of multisensorial modes that accompanied the objects in their contexts of origin. I will also suggest, however, that the MQB and similar museums could self-reflexively employ a multimodal translational lens in creative curatorial practices that break the museum’s own bones, so to speak. Such a practice could productively challenge institutional modes of relating to and making meaning with objects, and diversify the appeals to visitors’ horizons of experience as part of the meaning-making process. Finally, in examining cultural translation through a museological framework, I hope to contribute to the scholarly conversation on what translation offers and what it forecloses in a cross-cultural dialogue.

As a case study, this article employs a multimodal translational lens in the analysis of the MQB’s permanent exhibition of its collection of African objects in Paris, France. The MQB holds one of Europe’s most significant collections of the material culture of indigenous cultures from Africa, the Americas, Asia, and Oceania. This museum, and its African collection, is especially pertinent to a discussion of the politics of cultural translation because of 1) its ties to the French state, 2) the government’s deployment of the museum in political discourse, and 3) the contents of its collection. It must be noted that in France, public museums receive significant funding from the government, and moreover, are managed by the National Ministry of Culture and local government councils.[1] The MQB has an especially close relationship with the national government given that it was founded in 2006 by French President Jacques Chirac, as its name suggests.[2] Furthermore, national museums like the MQB are considered public spaces, and thus subject to rules of secular (laïque) spaces. As I will discuss later, the particularities of French museums’ relationship to the national government and their understanding of laïcité influence the kinds of translational choices that are made in these museums.[3]

In addition, the MQB’s collection of over 300,000 objects, acquired mainly during the colonial period by European anthropologists, missionaries, art dealers, and government officials, is a product of France’s colonial past.[4] However, the state officials involved in the project intended for the museum to speak to France’s postcolonial present. The museum opened at a time of high tensions around issues of immigration and racial discrimination. In particular, the police chase of Zyed Benna and Bouna Traoré, two unarmed North African teenagers, that led to the teenagers’ deaths in the low-income Parisian suburb of Clichy-Sous-Bois, sparked three weeks of violent protests the likes of which had never been seen in France and continues to loom large in the nation’s collective memory (see Dias, 2008, pp. 306-307). The MQB opened a little under a year after the riots, and Stéphane Martin, the museum’s president, called the MQB a “political instrument” much needed in a country that had seen social “troubles,” explaining that the museum would explore the “non-European world in our life of Europeans” (in Chrisafis, 2006, n.p.). In a similar vein, in his inauguration speech, Chirac proclaimed: “Au coeur de notre démarche, il y a le refus d’ethnocentrisme” [At the heart of our endeavor is a rejection of ethnocentrism[5]] (2006, n.p.). Nélia Dias summarizes the museum’s dual political role like as follows:

internally as a symbolic effort to reach out to non-Western peoples at a time when France is trying to reconcile increasing ethnic diversity within the Republican model of assimilation and externally as a way to proclaim France’s openness to the world.

2008, p. 301[6]

The MQB’s aspirations of multicultural communication and equity can be likewise heard in its signature phrase “là où les cultures dialoguent” [the place where cultures converse] (MQB, 2015, n.p.).

If cultures are to converse in a museum, one might imagine that translation will be necessary. Kate Sturge argues, in fact, that ethnographic museums can be regarded as cultural translators in that they represent cultures through the medium of objects, transposing these objects from their originating worlds of meaning into a new set of meanings and associations. She contends that ethnographic museum displays have “the task of ‘making sense,’ in terms intelligible to the receiving culture, of a mass of cultural practices” (Sturge, 2016 [2007], p. 129). This work includes both interlinguistic and intermedial translations, transposing the language in which the objects were embedded into other languages, and often from oral accounts to written accounts, as well as representing cultural practices via the medium of objects. Thus, for Sturge, museums both use translation in the preparation of their displays, and produce translations in rewriting the practices of one culture into terms understandable in another culture.

Indeed, all museums, ethnographic or not, can be considered a semiotic system—they have their own set of processes, practices, and signs for making and communicating meaning—that emerged out of Euro-American practices of knowledge production (Hooper-Greenhill, 1992). Museums with non-Western collections like the MQB draw on the disciplines of anthropology and art history, translating through these disciplinary modes of meaning-making objects that were once products and actors in a system that lived by other epistemologies. In terms of African collections more specifically, Mary Nooter Roberts (2008) points out that many African objects served not as aesthetic pieces, but as objects that encoded, transmitted, and produced knowledge. Similarly, Philippe Descola notes many of the objects display as art or artifacts in African museums were originally ritual objects, and contends that

un objet rituel n’a pas vraiment un « sens », un contenu crypté qui pourrait être explicité […]. Il a surtout une fonction, qui est d’opérer certains actions dans des circonstances bien précises et dans une configuration d’actants où sont présents d’autres objets, des personnes humaines et, éventuellement, des entités non humaines.

2007, pp. 146-145

[a ritual object does not really have a “meaning,” an encrypted content to be deciphered […]. It has, above all, a function, which is to make possible certain actions within specific circumstances and through a configuration of actors that include other objects, human beings, and, potentially, nonhuman beings.]

Because of the objects’ epistemological and agentic power in the societies that produced them, Roberts argues, curatorial practices ought to be transformed in order to render more accurately the significance of the objects they display. In other words, rather than translating the objects into the languages of the museum, museum professionals ought to invite “the languages and cultures from which they translate the contexts and purposes of the objects they seek to display” to reshape the practices of meaning-making in their museums (Roberts, 2008, p. 194).

Translation of and between cultures, then, is always already a part of museum practice, whether or not the museum seeks explicitly to “translate” the source culture of the objects it displays. While only a handful of museum scholars have delved into the role of translation in curatorial work, most have celebrated its potential to innovate curatorial work and activate a meaningful cross-cultural exchange with the participation of source communities (Mack, 2002; Neather, 2005; Hutchins and Collins, 2009; Quinn and Pegno, 2014; Tekgul, 2016). While the use of the term “cultural translation” does, I will suggest, have something to offer to curatorial practice, my case study will, like Sturge, consider the ways in which gestures of translation are already a part of standard curatorial practice, and not necessarily in ways that resist Western norms of meaning-making. As Mary Louise Pratt argues, “[a]ny act of translation arises from a relationship—an entanglement—that preceded it” (2010, p. 96). Translation between cultures may produce troubling outcomes; it may allow for the culture with the most resources, power, or privilege in the encounter to structure the conditions of the exchange and reshape the other culture(s) in its own image. In the case of the MQB, Isabella Pezzini notes that the museum may have blended an anthropological and an art historical approach in its museographic display and discourse, yet “[l]’une et l’autre discipline, toutefois, constituent des exemples de visions occidentales des autres civilisations, visions dont l’analyse fait ressortir les préjugés et les préconditionnements” [both disciplines, nevertheless, are examples of Western visions of other civilizations, visions whose analysis brings to light prejudices and preconceptions] (2015, n.p.). This is the type of assimilative translation that Talal Asad (1986, pp. 157-158) critiqued, arguing that anthropologists tended to rewrite the cultures they studied into the norms of the anthropologists’ own (Euro-American) horizon of understanding, thus committing an ethnocentric violence.

The invisible practices of translation that museums rely on to produce their cultural representations must be identified and interrogated if sustainable change is to be made to the epistemological frameworks of museums. Though the MQB collects artefacts from Asia, the Americas, and Oceania as well as the African continent, I am particularly interested in interrogating the exhibition of its African artefacts. The African collection is the one most often embroiled in political controversies due to its questionable acquisition histories[7] and, as of 2017, its central place in repatriation claims.[8] Moreover, as I will discuss later, the MQB was positioned at its opening as an institution that would help address social “troubles” related to the cultural integration of immigrants of North and West African descent. Given the MQB’s explicit claim to play a political role in France’s national cohesion and multicultural understanding, it is important to examine how this particular museum’s exhibitions use—or refuse—translation to promote such a cross-cultural dialogue and evaluate to what extent the exhibition, in Chirac’s words, rejects ethnocentrism. It is imperative, then, to ask: how does translation, as a product or process, manifest itself in the MQB’s displays? What gets translated, for whose benefits, through which systems of meaning-making?

The Museum as Translator

Museums communicate through multimodal address: material objects, visual elements, textual inscriptions, and spatial layout work together to prompt the visitor to make meaning of their experience. Let us imagine this encounter. At the MQB, a beaded funerary crown balances on a thin pedestal, its long fringes shielding its support from sight. A display case with a transparent front and back and nontransparent sides encloses the crown. This case is set in a dark alcove against a green window glaze with a tropical plant motif. A light fixture inside the vitrine shines down on the object, creating a strong contrast with the dimly lit alcove.

Figures 1 & 2

There is a text label placed on the right side of the vitrine, written in French (see figure 2). To read it, a visitor would have to move to the side, with the crown no longer in sight. The label states that the crown comes from present-day Nigeria, and belonged to the leader of the ethnic group known as the Fon people, though, the label explains, it was made in the style of the Yoruba people, their neighbors to the east. The title of the work is translated into English, but the descriptive content is presented only in French. A small map at the top of the label zooms in on the region where the crown was made, and another map, of the entire African continent, is inset to highlight where on the continent this region is located. A list of attributes, such as the crown’s material composition and approximate date of creation as well as categorical title, precede the narrative text in a strict order and with varying font sizes. The name of the donor and the inventory number appear after the text label, in the smallest font.

Imagine now that a visitor approaches the alcove and encounters this ensemble, which combines the major museographic and interpretive elements found throughout the MQB. Taking as a given that exhibitions draw on a variety of semiotic resources that “can facilitate particular forms of visitor interaction, can prioritise some meanings in the exhibition rather than others, and can construct a picture of what the subject matter ‘is’,” (Ravelli, 2006, p. 121), this article asks what forms of meaning-making, perception, and emotion might be prompted by the visual, textual, and spatial translational practices employed by the curators.

The semiotic resources and their material or immaterial qualities—what Gunther Kress and Theo Van Leuween call a “mode” (2001)—through which a translation is produced will affect the knowledges produced with it. Like Kress, I seek to elucidate the “potentials—the affordances—of the resources that are available […] for the making of meaning” (Kress, 2011, p. 38; italics in the original). For this reason, I will speak of gestures and moments of translation, to emphasize the possibilities that are activated through both the museum’s curatorial work and the visitors’ horizons of experience, rather than a translation as a fixed product. Placing the funerary crown I mentioned above in a Plexiglas case for observation is one translational gesture in an assemblage that includes the writing of the text label (another gesture) and its location in the space of the museum (yet another gesture), for example. Though translational gestures, in my theorization, come with a thrust of intentionality and direction, what they set in motion cannot be fully predicted or captured. Nevertheless, these translational gestures, taken together, shape how the visitor interacts with and makes meaning out of his or her encounter with the crown. In museums, what this suggests is that translational gestures must be examined in their multi-modality, as they orchestrate layers of interlinguistic, intralinguistic, and intermodal transpositions which will favor (or discourage) different types of dialogue between cultures.

To tease out the various ways in which translation participates in the MQB’s address, I organized the article into two parts. The first part focuses primarily on the text labels at the MQB, since they are the primary mode of contextualization that is immediately accessible to visitors in the permanent exhibition.[9] The second part interrogates the spatial and visual vocabulary that the MQB employs. Both parts attend to the multimodal assemblages in which the museum’s textual, spatial, and visual vocabulary operate.[10] A multimodal discourse analysis approach reveals that the MQB’s emphasis on visual and textual literacy does not refute ethnocentrism, in that centers an ocular relationship with the objects that is more typical of Western museums than of the way the objects were interacted with in their context of origin. However, my analysis also suggests that more explicitly foregrounding the inherent but subdued multimodality of museum discourse may be a way to foreground the lost multimodality of the objects on display, and thus come closer to a dialogic rather than ethnocentric “cultural translation.”

I. Label Text and Translation

One of the most common critiques levied against ethnographic museums has been one of authorial voice, and the MQB has not escaped such critiques (see Grognet, 2007). The museum speaks about cultural practices and artistic products—often acquired with some degree of coercion[11]—in place of the peoples who created and used them. However, one of the particularities of French museological practice is a reluctance to speak about the objects at all, claiming that the objects can speak for themselves. This was described by the MQB president, Stéphane Martin, as an “absolute cult for the authentic” in which the “French curator will always start from the object” in contrast to Anglo-Saxon curators who will ground their exhibitions in a story or a community and use objects to illustrate the narrative they are communicating (Naumann, 2006, pp. 122-123).

This emphasis of the object over any contextualizing information was confirmed by Gaëlle Beaujean-Balthazar, the current lead curator of the African collection at the MQB. In an interview with me, she reported that the museum’s policy is to place any interpretive media—text labels, videos—at a certain distance from and out of the eyeline of the object they refer to, since they must never distract from the objects (Beaujean-Balthazar, 2018).[12] This suggests that in the MQB, the objects on display are treated as a kind of visual “text” from which linguistic translations can be derived. To put it another way, objects are treated as having a communicative power via their visual qualities, and the label is presented as communicating the same content as the object, just in a difference language.

One example of the emphasis on linguistic translation of visual qualities comes from the label for ceremonial objects from Southern Africa. This label contains a quote, in French, that primes visitors to look for particular visual qualities that are unique to (“se distinguent par”) ceremonial objects in Southern Africa (see figure 3, next page). It then describes the social effects that these visual qualities produced in their culture of origin: “donne à leur aspect quelque chose de très imposant” [gives them an imposing appearance]. The text is descriptive, matter-of-fact, written in the third-person perspective of an observer—“they appear,” “their costumes,”—rather than a participant.

The apparently transparent relationship of equivalence between “original” object and “translated” text label, however, masks a whole series of translational gestures that preceded the object’s arrival in the exhibition space and conditioned the creation of the label. For one, the content presented in the French label is itself a product of many translations that began hundreds of years ago, from indigenous African languages into and between European languages.

Figure 3

In fact, the quote in the label, dated 1827, is attributed to Robert Moffat, a Scottish missionary that evangelized for nearly fifty years in what is present-day South Africa. Moffat translated into written English the meanings of objects and cultural practices that were communicated to him orally in local languages or visually through observation of the practices. This is, then, a knowledge produced via multiple acts of interlingual and intermedial translation, including the choice by the curators to select this quote. The meaning of the object, in other words, is not “recovered” but created in the very process of translating into text label; it is an “invention” in the sense that V.Y. Mudimbe (1988; 1994) argues most knowledge produced in the West about the African continent tell us more about European perceptions of Africa than about the lived realities of the peoples they studied. There are curators at the MQB that are keenly aware of the distance between the “original” object and the museum’s “translation” of it, including Anne-Christine Taylor, who served as director of research and teaching from 2005-2013. Taylor evokes “l’épaisse couche de médiations qui s’accumule entre l’objet dans son milieu d’origine et l’objet tel qu’il est exhibé dans un musée” [the thick layer of mediations that accumulates between the object in its context of origin and the object as displayed in a museum] and argues that the MQB’s purpose is not to show the living cultures of non-European peoples, but rather “l’histoire des regards portés sur ces cultures” [the history of how these cultures have been perceived] (2008, p. 680). While examining such a history is interesting in its own right, it does not square up with the museum’s claim to reject an ethnocentric perspective, since it ultimately centers a European history of perceptions of non-European objects.

Moreover, if the goal of the MQB is to display the history of European views on African cultural objects, such a discussion is curiously absent from a text label which displays (a French translation) of Moffat’s words. Interestingly, Moffat’s book is written in the first person, but the excerpt selected omits any of the “I” phrases, de-emphasizing what was a particular context of enunciation and encouraging a rhetorical interchangeability between the person speaking for the object and the object as a spokesperson. Had the markers of Moffat’s address been maintained within the label text, the fact that the quote spoke to one possible way to look at the objects that was informed by a particular (European) cultural and historical (19th century) context could have been more explicitly addressed. The invisibility of these previous gestures of translations effaces the process of negotiation, (mis)communication, and appropriation that shaped the body of knowledge used by the MQB to make choices about how to display and describe—in other words, translate—their objects. This is not just the case in the label that quotes Moffat, but perhaps even more so in the majority of the labels that, as is standard in museum practice, are not attributed to anyone. The text labels tend to sweep under the rug the thick layer of mediation that Taylor acknowledges.

However, what would happen if museums were to engage with this translational aspect of curatorial work, centering the thick layer of mediation to highlight how their displays are part and parcel in a series of translations, entangled in a history of negotiation of cultural meanings? Indeed, rather than starting with the object as the “authentic” spokesperson, the MQB could choose to point to how the museum, through its archive of information and curatorial choices, actively translates what the object can say—its meanings and effects. One approach highlighting these multiple, overlapping translational gestures that shape the objects’ existence in the museum, would be inviting an explicitly self-reflexive lens in the writing of text labels. A self-reflexive translation does not reproduce the dominant culture’s interpretive horizon; instead, through the rewriting it brings those entanglements—including the translator’s own ones—to the surface. The translation, in this method, is considered to be a product of particular locations of enunciation and reception, rather than a universal address.

In museums, highlighting translation as a local production of meaning—which includes emphasizing the conditions under which the translation was made and the purposes it serves—can enable museums-as-translators to position themselves not as neutral transmitters of a different culture, but as producers of a cultural practice that runs tangent to the cultural practice they display. In one of their temporary exhibitions, Artistes d’Abomey: Dialogue sur un royaume africain [Artists of Abomey: Dialogue on an African Kingdom], the MQB attempted to locate its text labels within particular cultural outlooks along these lines. Each label had a text written by the curator, Gaëlle Beaujean-Balthazar, and a text written by Beninese scholar Joseph Andadé and Beninese curator Léonard Ahonon (or other Beninese scholars and artists they invited). The texts were unsigned, but were marked with a pictogram that identified the words as coming either from the MQB, or from the Beninese participants. The dual-perspective certainly opens up the meaning of the objects on display, demonstrating how the same “original” object can lead to different “translations.” However, by creating a “European text” and a “culture of origin” text, the MQB may have unwittingly emphasized a binary between the two modes of making meaning with the objects on display. Though the exhibition title called it a “dialogue,” the presentation suggested two parallel monologues laid out side-by-side. Instead of exploring the ways in which the two perspectives respond to each other and change over time, by presenting them as equal but separate, the exhibition risked essentializing cultural differences.

Taking the dual-mode of translation a step further, Kate Sturge demonstrates the power of polyphonic gestures of translation in museum practice (2016 [2007], pp. 168-174). She points to the example from the Horniman Museum in London’s “African Worlds” exhibition, renovated in 1999. The labels contain a collectively written text, with some individually written reflections. Each of the authors is named. Moreover, the authors include anthropologists from both European and African countries, and residents of London or of the objects’ countries of origin that identify with the culture being discussed. In addition, some labels include proverbs related to the object on display, or a comment by a community member, alongside the collectively written text. The label notes the date and place where the comment was made, and perhaps even a photo of the commentator. This polyphonic gesture of translation thus allows for a plurality of voices that are nevertheless situated in a particular time, place, and mode of relating to the object (e.g., professional, vernacular, aesthetic, spiritual, etc.). It allows multiple positions and types of discourse (historical and collective, personal and present-oriented) to coexist in the very moment of translation, rather than as distinct sides that are each timeless and hegemonic. In this way, polyphonic translation in museums responds to what Myriam Suchet identified as one of the key issues for postcolonial translation:

garantir qu’une telle substitution ne vire pas à l’usurpation. Il s’agit d’assurer un dialogue avec au lieu d’une parole sur celles et ceux qui sont représentés.

2012, p. 85

[to guarantee that substitution does not turn into usurpation. It is a matter of ensuring a dialogue with instead of discourse on those who are represented]

Particularizing while pluralizing the labels brings, moreover, the questions of who gets to translate cultures, why, and for whom, to the forefront of museological practice, and hopefully also to the forefront of the visitors’ minds. There is some evidence that visitors are already asking themselves questions in this vein. Octave Debary and Mélanie Roustan argue that the MQB’s ahistorical contextualization of the objects on display, and its labyrinthine organization, prompts visitors to ask three questions: what are the objects, how did they get here, and what happened to the cultures that made them? Based on their interviews with visitors, Debary and Roustan conclude that

En assumant cette perte du référent historique, le musée du Quai Branly propose aux visiteurs une expérience réflexive. […] l’on rencontre l’autre en même temps que sa disparation. Comme un songe, un rêve, une définition silencieuse du colonialisme.”

2012, p. 63

[Embracing the loss of historical reference points, the musée du Quai Branly offers visitors a reflexive experience […] where one encounters the Other and the Other’s disappearance at the same time. Like a vision, like a dream, a silent definition of colonialism.]

Debary and Roustan’s research speaks to the important role that visitors’ previous experiences and knowledges play in the production of meaning. However, even if the absence of the voice of the “other” (i.e., non-European) may prompt (European) visitors to wonder what caused the disappearance of this so-called “other”—who might be a visitor themself—it seems more fruitful for an institution that wants to create a space of dialogue to bring the “other” into conversation. A dialogue that is structured around the absence of one of the interlocutors is a curious dialogue indeed. Instead, using polyphonic translation that highlights past and present moments of translation in the MQB’s collection as a curatorial mode of writing, I argue, might help the MQB come closer to its stated goal of facilitating a conversation between cultures, especially if such labels are part of the year-round, permanent exhibition, rather than short-lived interventions like in the MQB’s innovative Artistes d’Abomey. Such polyphonic translations, even if applied to only some of the labels, would amplify the voices that speak to other ways of looking at these objects and counterbalance the voice of the museum as the sole author-ity of the cultural objects it displays.

There is another translational gesture present in the MQB’s labels which merits brief discussion: the practice of non-translation and intralingual translation, visible in several of its thematic labels. One example of a non-translational gesture is found in the “Esprits protecteurs” [Protective Spirits] label (see figure 4, next page), placed next to a room displaying several nkisi from the Congo peoples. This thematic label, like most thematic labels at the MQB, has the textual information presented in both French and English. It primes the visitor to consider the display in the context of a widespread belief in the power of objects to call upon protective spirits. In the third line, the label introduces the word “nganga,” a word in the kikongo language. The refusal to translate is particularly striking since several terms related to spirituality are used in the label text in English and French: “magical charge,” “talisman,” and “evil spell,” for example. For “nganga,” three terms are offered in both French and English through which a translation might be triangulated: “officiant masqué, prêtre et devin”/“masked officiant who is both priest and seer.” The italics emphasizes, in case one did not notice, that this word comes from a different language. In other words, the label enacts a visual inscription of difference in addition to the linguistic inscription of difference.

What does this choice of non-translation and intralingual rephrasing suggest about the model of cultural dialogue that the MQB puts in place? The label does not foreclose the meaning of “nganga” but rather points towards a possible direction. It offers no equivalent term, but suggests that the meaning can be located in the space between the three terms. This gesture of translation thus notes the limits of the translator’s (in this case, the museum’s) language to convey meaning. At the same time—and this is what I want to draw attention to—the MQB still attempts to use a unit of linguistic inscription to create a relationship of understanding between the visitor (whom it presumes will be familiar with the terms “masked officiant,” “priest,” and “seer”) and “nganga.”

Figure 4

Thus, as a translator, the MQB assumes that cultural knowledge is gained and transmitted through written language, and that the obstacle to cross-cultural understanding is not finding the right term. This is short-sighted for two reasons. One is that, as Lydia Liu (2000) notes, the equivalent of a word in a different language does not precede the act of translation but is produced in the moment that the equivalences between two languages are identified and assembled. The fact that “prêtre,” “devin,” and “officiant masqué” exist in French conditions how the museum—and then the presumed visitor—might understand “nganga.” Because French (and English) are “strong” languages (see Asad, 1986, p. 159) in that they hold more economic, political, and social power, these terms eventually shape the meaning of “nganga” in global circulation. The second reason is that while the MQB is right to acknowledge the cultural specificity of “nganga,” the museum limits itself by seeking to communicate the cultural specificity of “nganga” through other linguistic terms. As I will discuss at the end of the next section, other choices are possible, choices that break away from the contextualization through linguistic inscription that the museum emphasizes in favor of extra-linguistic modes of discourse.

II. Spatial and Visual Vocabularies

In this section I will discuss how the spatial and visual language of the MQB, much like its textual language in the labels, translates the objects it displays into the semiotic norms of French museums. The MQB’s museography, I will suggest, invites an ocularcentric visitor experience in that visual perception is the primary resource given to visitors to prompt meaning making, and the emphasis on visual perceptions likewise centers the objects’ aesthetic qualities. This emphasis on visual relations cuts off the African objects on display from a sensory context and set of use-relations that informed their existence in their cultures of origin, translating them into objects for visual pleasure. Once again, this contradicts the MQB’s stated goals of cultural dialogue and countering ethnocentrism. Rather than making space for various ways of making meaning with material objects, the museum “limits the field of cultural diversity to one supposed universal form, the artistic one” and with a “stress put on art as a common denominator across societies” (Dias, 2008, p. 304). As a result, French museums’ culturally-scripted modes of meaning-making are reaffirmed, rather than being expanded through intercultural challenges.

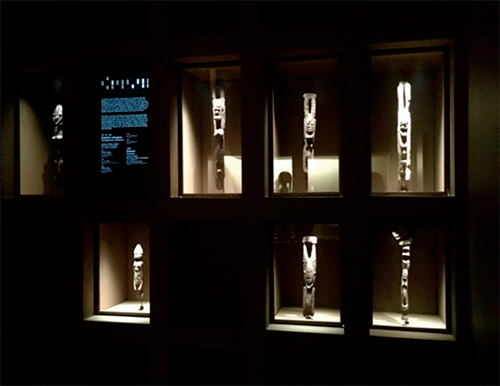

In some ways, the MQB’s exhibition halls—dimly lit, with somber brown and black as the primary hues—share more in their design vocabulary with the anthropological museums of yore than the contemporary white cube aesthetic of art galleries or the marble gleam and gilded trim of museums displaying “universal” collections of (primarily Western) art like the nearby Musée du Louvre. At the MQB, the objects are not displayed on walls, but in Plexiglas cases. Some are stand-alone cases that divide the exhibition corridor, while others are set into long walls that flank the right side of the corridor. On the left side, a series of small rooms create self-contained miniature exhibition spaces, where again the objects are displayed in vitrines set into the walls. The stand-alone vitrines are imposing; the vertical ones loom up past any visitor’s head while the horizontal ones can run a couple meters long.

Figures 5 & 6

Even though vitrines were a key component of the museography at the ethnographic Musée de l’Homme and the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro from which a significant part of the MQB’s collection was built, at the MQB, the vitrines, I argue, translate the objects into a vocabulary of aesthetic formalism that highlights the visual qualities of objects, rather than their social, spiritual, or quotidian functions. Certainly, the vitrines have a practical purpose; there are times when museums, to preserve their objects from variations in climate as well as the threat of visitors’ wandering hands, must keep particularly fragile objects in glass cases. However, even if the vitrines are meant to shelter the objects, they do not appear to have been designed with the objects’ real-world orientations and functions in mind. Sally Price records a particularly flagrant example of this in her study at the MQB’s opening, where a man’s shoulder cape from the Paramaka Maroons was displayed vertically rather than horizontally, as it would have been worn by the peoples who made it (Price, 2007, p. 122). When Sally Price and Richard Price pointed out the error to the curators:

the solution was to add a corrective note to the label (a sort of permanent museological erratum) rather than to change the position of the object in the case itself. Clearly, the cape could have assumed its normal orientation if it had been allowed to extend onto the case’s side panels. But the architect designed the case for a vertical object, so vertical is how the cape remains.

ibid., p. 147

While Price’s example is a particularly striking one, overall, it seems that at the MQB the objects must conform to the shape of the cases rather than the other way around.

The MQB’s systematic enclosure of the objects on display, in that sense, effaces the specificities of how the objects were used, touched, engaged with in their cultures of origin. It privileges, instead, a way of looking at the objects that is informed by Euro-American museum epistemologies. The MQB flattens objects that were three-dimensional and mobile in their cultures of origin, rendering them as static, two-dimensional aesthetic forms to be visually admired. The hanging, lighting, and spatial arrangements emphasize the objects’ formal qualities over any other of its material qualities and meanings. One example of this is found in one of the small exhibition rooms accessible on the left side of the exhibition corridor. Here, the back wall of the room is divided into several rows of individual cases, holding one object per case. The grid frames each three-dimensional object against a neutral background, so that the visitor can only see the side facing out. The visual effect resembles a series of photographs rather than statues (see figure 7).

Another example of the flattened aesthetics is found in the MQB’s displays of clothing, such as caftans from North Africa and boubous from West Africa. These items of clothing are systematically stretched out to hang flat (as shown in figures 8 and 9). As a result, the three-dimensional objects appear two-dimensional. While stretching them out highlights the embroidered designs, it de-emphasizes the textile’s drape, its movement, and how it would have hung on the body of the person that once wore it. Similarly, an indigo-dyed boubou from Cameroon worn by men, hangs flat into a long rectangle. Boubous are luminous and delicately embroidered robes that have a single opening for the head. Their embroidered motifs reference Arabic calligraphy. When worn, sleeves are formed by draping the long cloth over the shoulder and arms, creating elaborate folds. By mounting the boubou flat, more of the embroidery and the geometric shapes are visible, calling attention to the boubou’s formal qualities, expert handiwork, and Islamic references. However, like the caftans, its three-dimensionality and interaction with the human body are effaced; the boubou is thus rendered as a pictorial surface that one gazes upon as an oil painting in a museum or a fresco in a church wall.

Figure 7

Figures 8 & 9

It is as if, to be able to exist in the MQB, the boubou and the caftans have to be remolded to resemble the type of art objects that already populate museums in Europe. Visitors then might learn to appreciate the boubou as a work of art like they would appreciate a painting, but they are not given a chance or challenged to appreciate it on its own terms. Visitors who are unfamiliar with how a boubou is worn are not asked to consider what it would mean to appreciate moving art that flows on a person’s body. Similarly, three-dimensional objects are regularly mounted into a kind of collage that creates a pictorial ensemble. Several wooden carved and painted masks from the Dogon peoples are mounted against a white wall at the end of a long room (figure 10).

Figure 10

This grouping makes certain patterns emerge: the shape of the eyes, the angles of crossed crowns at the top of the masks’ foreheads, the general vertical elongation of the faces. There is nothing wrong with appreciating these formal qualities, nor with admiring the craftsmanship and creativity that generated the masks. But, once more, the objects are translated through formal regimes for visual consumption that speak more to Western cultural practices of museum-going than to the uses, contexts, and meanings of the objects in their cultures of origin. A European gaze is at the center once more.

I noted earlier that the MQB translates its objects through a pictorial vocabulary that effaces the human presence of the people who made, wore, or otherwise used the objects in the collection; it also, however, effaces all signs of curatorial intervention by hiding the mountings and pedestals. Tapestries, masks, doors, spoons, all sorts of objects appear to float in the vitrines. The mounts are painted black to blend in with the paneling and carefully located so that the objects hide them from sight. Videos, text panels and other interpretive materials are placed at a distance from the objects they discuss, so that the visitor can have a “direct” interaction with the objects, without any clutter. The intentions behind this, as described by curator Beaujean-Balthazar, are to not distract from the objects themselves: the “authentic” artistic examples (2018, n.p.). However, by making all curatorial intervention as invisible as possible, the MQB naturalizes the state in which the visitors encounter the objects, when in fact the objects have been reshaped to speak through the semiotic norms of the museum.

To its merit, this does help the MQB avoid some of the language of primitivism that was prevalent in earlier Parisian exhibitions of the same collection. A rich visual world is conjured up in the MQB’s exhibitions, encouraging visitors to relate to the objects like they would any other object in a French museum, “promus au rang d’oeuvre” [elevated to the status of artwork] (Dias, 2007, p. 77). Declaring the MQB’s collection to be part of humanity’s artistic heritage and highlighting the objects’ aesthetic value through the museography appears to be the solution that Stéphane Martin settled on in order to “créer un musée qui s’inscrive dans une tradition française” [create a museum that follows a French tradition] (2007, p. 11). My contention is that the MQB presents African material culture as a set of aesthetic forms to be admired visually and explained linguistically. Through these curatorial choices, the MQB creates a bimodal translation of what were elements of a multimodal cultural practice that prompted a set of sensory experiences and ways of meaning-making through all manners of extra-linguistic and more-than-visual interactions. The cultural capacity of visitors who are accustomed to Western and especially French museum experiences to imagine other ways of relating to and making meaning with objects—ways that do not rely on visual scrutiny or on linguistically deciphering the meaning of objects—is not challenged or provided with alternatives. This does not make cross-cultural dialogue impossible, but it does set the parameters of dialogue through ethnocentric terms, asking the visitors and the objects to speak through the (culturally scripted, Euro-American) language of the museum, rather than inviting the objects (and perhaps the visitors’) languages to sound out their dissonance and differences. In fact, Elizabeth Edwards et al. critique “the pervasive colonial legacies which have privileged the Western sensorium and the role that museums have played in the continuing inscription of this particular way of being-in-the-world” (2006, p. 1). If one of the MQB’s primary goals is to “reject ethnocentrism” as Chirac proclaimed, it has missed the mark; the “dialogue” with other cultures that it offers to its visitors is firmly devoted to reinforcing France’s own universalist values and epistemologies.

This is where approaching translation as a multimodal exercise that attends to the ensemble of material and immaterial resources that participated in a particular objects’ salience in its context of origin, might help transform the semiotic system of museums in service of a deeper dialogue between cultures. The MQB has, actually, made a few curatorial choices that gesture to such a translational approach. In its display of sacred objects made by a Kono association of the Bamana peoples in what is present-day Mali, a text label informs visitors that these objects could only be seen and used by members of Kono associations during male initiation ceremonies. To further convey the object’s sacred past and restricted use, the MQB display the Kono objects in a very small room where only a few people can enter at a time. In addition, the vitrines are partially obstructed by thick, sinuous columns so that the objects are not fully visible. The curatorial choice allows to MQB to display sacred objects while partially restricting the visitors’ visual appreciation of them. It’s a translational gesture that attempts to keep the aesthetic and the sacred qualities of the Kono objects in dialogue.

However, what remains centered is, once again, visual scrutiny. It appears that the choice is either to see the objects and know them, or not see them and respect the secret and sacred knowledge they embody. Translational gestures could go further, I suggest, if they make more explicit calls to other modes of perception and sensation that the visitors are using as they walk, stand, listen to, lean in, etc., in museum spaces. One example of what this could look like comes from a temporary exhibition called Activate/Captivate: Collections Reengagement at Wits Art Museum that took place at the Wits Art Museum (WAM) in Johannesburg, South Africa. For the Activate/Captivate exhibit, curators Laura de Becker and Leigh Leyde invited students from the Digital Arts Department at Wits University to rethink the display of their collection with these conundrums in mind. A Bamana Komo mask was one of the objects in question, given that, like the sacred objects used by Kono associations that the MQB displayed in a special vitrine, only initiated members of a Komo association are allowed to see and use. To harness the power of the mask, members make prayers and sacrifices as they apply potent materials such as blood, chewed kola nuts, and millet beer to the mask. For the Activate/Captivate exhibit, a student designed a way to display the Bamana Komo mask behind a curtain activated by a sensor. The curtain hung open, but whenever visitors approached the mask, their movement triggered the sensor, closing the curtain.

The student’s curatorial choice, I suggest, comes much closer to translating the mode of relating to the object conveyed in its original context. For one, the kinetic element is reintroduced in the relationship between visitor and object—the visitor’s bodily movement responds to the mask. It also changed the affective dynamic between the mask and the visitor, reducing the scopic and agentic capabilities of the visitor, who could get frustrated and as they attempt different ways to get close to the mask, only to have their sight thwarted every time. As WAM curator Laura de Becker eloquently notes, “what we see in [African] museums are, more often than not, static remnants of a dynamic performance” (2017, n.p.). Sometimes, museums will address the African masks’ kinetic dynamism by showing video recordings of (often recreated) performances. While the videos can provide useful context, they invite visitors once again into the role of observer. In contrast, the student’s curatorial choice did not reproduce the “original” dynamic performance, rather it made looking at the mask a dynamic performance in itself. It invited the visitor into a kinetic interaction with the mask that took precedence over the visual interaction. Granted, it is the curtain that moves and not the mask, but the reintroduction of a kinetic interaction in which the visitor might become aware of their body and the mask responding to each other—and in which the mask holds a power over the visitor—transposes some of that sensory experience and relationship to the object that existed in its context of origin.

Furthermore, the interruption of visual access to the object radically resists the dominant mode of meaning-making in museums, which is one of understanding through visual scrutiny and textual inscriptions. In the example of the label that used the word “nganga,” even when the MQB positioned the term as incommensurable to any individual word in French or English, it still attempted to “domesticate” it by giving the visitor linguistic clues to understand it. The label thus suggested that the term posed a problem, not the epistemic tools through which it attempted to understand “nganga.” In the WAM’s deployment of a curtain, to the contrary, the mask is not presented as an object to be deciphered, but rather as something whose primary role is to provoke action. If anything, the mask requires neither (only) visual scrutiny nor (more) linguistic explanation, but a set of movements and interactions with other human and material bodies to begin to convey that power. It is not the term but rather the tools and the visitor’s positionality that set limits on cross-cultural understanding. Certainly, there are other elements from the mask’s use in its contexts of origin that are missing: the tactile interaction, the olfactory stimulation, the collective experience with members of the association. But that is precisely why museums could be approached as a space of translation, in which the purpose of the translation is not to recover an “original” context but produce resonance while communicating the relevance of the source “text.”

In other words, what I find particularly transformative about the curatorial choice made by the student at the WAM is how it casts the discourse and interactions that take place in a museum as culturally-specific practices themselves—as local, socially-constructed modes of dealing with objects, rather than as a universal aesthetic experience. As the visitors are cut off from culturally-scripted modes of interacting with objects in museums, unable to use the sense (sight) that is usually solicited in museum spaces, they are invited to reflect on the activity of visiting a museum as a cultural practice. They are also invited to reflect on what it means to have the power to see that mask in the museum space. At a time when debates on ownership, repatriation, and cultural authority traverse public discussion in France, these questions seem particularly resonant.[13]

Once again, my question is: if the translational lens provides tools for critiquing the way the MQB and similar museums display their African collections, does the study of cultural translation also provide clues, methods, or tools for reimagining the display in ways that break the semiotic bones of the museum? One way in which the MQB’s collection could make space for the objects in its collection to participate in alternative modes of making meaning would be to honor the requests of communities who wish to borrow objects for use in a cultural practice. The goal would not be to create “authentic” performances of a cultural tradition for a museum public but rather to allow communities to deploy the objects as they deem appropriate within their own practice. However, the MQB routinely denies such requests on the grounds of laïcité. As Price reported in her study of the MQB’s opening (2007, pp. 123-126), and Beaujean-Balthazar (2018, n.p.) confirmed in her interview with me, the MQB, as a national museum, is a public space bound by the guidelines of laïcité. The objects in its collection, even if they were once used in religious practice, must be divested of their spiritual charge once they are in the museum. The MQB reasons that if it allowed objects in its collection to be used by a group based on religious or ethnic affiliation, it would be tantamount to showing religious favoritism. The MQB’s head of international relations explained in 2005: “If you really believe that these things have a profound meaning, well, the museum isn’t made for that” (quoted in Price, 2007, p. 124).

But why couldn’t a museum make room for “that” (a rather dismissive way to refer to belief systems)? Why couldn’t the objects’ laïque and spiritual identities be co-operational with their aesthetic and anthropological ones? Mamadou Diouf reminds us that “la notion d’espace public qui exclut l’espace rituel n’est pas nécessairement vraie dans toutes les sociétés” [the notion of public space as excluding ritual space does not necessarily hold true in all societies] (in Latour, 2007, p. 151). By choosing to close off certain possible dialogues on the basis of laïcité, the MQB does in fact demonstrate cultural favoritism—privileging the Judeo-Christian understandings of spirituality that structures the way laïcité is defined and policed in France. Moreover, as James Clifford argues, the imposition of a single dominant meaning that overshadows other potential meanings, is the colonialist act par excellence (Browning, 2006, n.p.). Again, I am not suggesting that the objects’ ability to act within certain religious systems is a “more authentic” way of understanding their meaning, effects, and cultural value. Nor am I suggesting that the MQB ought to attempt to reproduce verbatim the cultural practices and beliefs of other peoples and other times. Brigitte Delron rightly signals that while she finds it perfectly understandable for an individual to request to pray with an object, it would be “extrêmement gênant qu’un musée se réapproprie les croyances religieuses des autres” [extremely discomfiting for a museum to appropriate other people’s religious beliefs] (in Latour, 2007, p. 156). Rather, I am suggesting that making room for those who do hold such beliefs to deploy some of the objects in the MQB’s collection is one of several, co-existing ways of producing knowledge about one’s own and other cultures, and that engaging with all of these forms of meaning-making is crucial to cross-cultural dialogue. In other words, the MQB’s emphasis on the authenticity of objects might be less suited to its mission of cultural dialogue than an emphasis on equity between the interlocutors around its collection would be.[14]

Museums as Multimodal Cultural Translators: Points of Entry and Limitations

This study has shown that attending to the multimodality of translational gestures in museums points to where the MQB could go further in its stated goal of decentering European perspectives. Given the MQB’s aims toward cultural dialogue, this study has also suggested that the inclusive polyphonic addresses and multimodal meaning making that would favor such a dialogue are largely missing. However, I have pointed to some ways in which the MQB and similar museums are already beginning to and could further rethink their museographical choices in creative ways that amplify self-reflexive translational gestures and encourage visitors to engage in multimodal meaning-making experiences through varied forms of perception.

To further research on museums like the MQB as cultural translators, and to make informed curatorial choices that incorporate a multimodal translational lens, the visitor experience is a major avenue of investigation. What modes of engagement are effective for communicating the way translation operates in the museum space? Which practices informed by translation make a memorable impact on visitors? Octave Debary’s and Mélanie Roustan’s anthropological study of visitors in the permanent gallery is an excellent start. While Debray and Roustan relied primarily on the visitor’s verbal and visual processing of their experience, through interviews and asking the visitors’ to draw maps of the gallery, one can imagine a follow-up study in which analysis of the visitor’s embodied experiences, indexed through their gestures, gazing, movements, etc. is also taken into account.[15] In addition, research on how museums or other community organizations on the African continent are translating museums practices to serve local needs and desires would allow us to consider the question of cultural translation in museums from another position: what does it mean when it is the language or culture that has been the source-text, so to speak, of translation, that becomes the translator? How do the political effects of and frameworks for understanding cultural translation shift when European languages and epistemic systems are translated out of rather than into?

While it is beyond the scope of this article to begin addressing these questions, I hope what this study does accomplish is provide examples of translational gestures in museums that will further discussions of the modes of meaning making that can be turned into resources of cross-cultural dialogue in museums. Before closing, I want to briefly return to the metaphor of bone-breaking which opened this article, which comes from a short story written by British-Nigerian author Helen Oyeyemi. Oyeyemi’s protagonist, Radha, eventually chooses to translate her great-grandfather’s novel into French, and English, and Russian, knowing that its bones will be broken, as it allows her to read the novel to the woman who is her love interest. Rhada translates the untranslatable because it allows her to act on her artistic and romantic desires in the present. Radha’s gesture of translation echoes with the translation practices that Evan Maina Mwangi’s study of literary translators translating into and between African indigenous languages refers to as “a foreign text to depict local desires” (2017, p. 155) that have political and social implications. I bring this up to note, as Tomislav Z. Longinovic does, that “[t]he survival of local narratives and rituals as untranslatable events does not insure their permanence and purity as life-affirming practices of a community” (2002, p. 11). Museums with African collections have long placed a premium on authentic cultural practices as those that are timeless and unchanging. I hope that this article’s discussion has shown that preservation of authenticity is not the aim of cultural translation, but rather the creation of relevance in another context. And that, depending on the gestures chosen and positions adopted in the moments of translation, this relevance can be one that resists or transforms the push and pull of power relations at work in museum spaces.

Parties annexes

Biographical note

Abigail E. Celis is assistant professor in the Department of French & Francophone Studies and the Department of African Studies at the Pennsylvania State University, where her research and teaching explore the creative and critical expression of the sub-Saharan African diaspora in France, spanning a range of primary sources that include visual art, literature, cinema, and museum practices. Her scholarly production includes curatorial work and creative collaborations with practicing artists. She is co-editor of A Companion to World Literature: Volume IV (Wiley-Blackwell, 2020) and she has published on the Dak’Art Biennale and colonial encounters in World literature. Her current book project, Unsettled Belongings, brings together contemporary novels, museum exhibitions, and contemporary art installations to investigate the role of material objects in telling stories of migration, nationhood, and diasporic identity in France and West Africa. She has received fellowships from the Ford Foundation, the Camargo Foundation, and the Lurcy Foundation for her research.

Notes

-

[1]

Most museum staff, including curators and conservationists, are government employees (fonctionnaires) who have passed national qualifying exams (concours); moreover the collections of museums with the “musée de France” designation are considered public property and all acquisitions, deaccessions, and conservation decisions must be approved by a governmental committee.

-

[2]

Like Georges Pompidou’s Centre Pompidou for contemporary art and François Mitterand’s Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the MQB is part of a tradition of French presidents’ founding a new, high-profile public cultural institution as a legacy act. See Price (2007) and De l’Estoile (2009) for a comprehensive discussion of the debates and controversies surrounding the MQB’s opening.

-

[3]

See Latour (2007, pp. 145-177) and Price (2007, pp. 122-126) for a discussion of how the MQB articulates its policy of laïcité in relation to both repatriation claims and collaborations with communities of origin.

-

[4]

A good portion of the MQB’s collection was inherited from the Musée de l’Homme and the now-defunct Musée des Arts africains et océaniens, both of which inherited their collection from the Musée des Colonies and the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro. These museums, founded in the 19th and early 20th centuries, were closely related to promoting France’s colonial mission. See Aldrich (2005), Demissie (2009), and Jules-Rosette and Fontana (2009) for a discussion of the history of colonial museums and their relationship to postcolonial Europe.

-

[5]

English translations provided in brackets in the article are mine.

-

[6]

See also De l’Estoile (2007) and Lebovics (2010) for a discussion on the museum’s politicized treatment of France’s colonial past.

-

[7]

For more on the MQB’s acquisition history, see Price (2007, p. 125 and 156); Clifford (2007, p. 15); Sauvage (2007, p. 137 and pp. 143-144); Sarr and Savoy (2018; pp. 87-104). Furthermore, as Price notes, the uneven conditions of knowledge and power in which even 20th century collectors operate allow for acquisition practices that exploit the makers, even if legally, to continue (1989, pp. 68-81).

-

[8]

In November 2017 at a public speech at the University of Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso, French President Emmanuel Macron pledged to return to the African continent African artefacts held in public French museums. Of the museums in France, the MQB has been the center of attention; it holds nearly 80% of the African artefacts inventoried in French public museums (Sarr and Savoy, 2018, p. 75).

-

[9]

See Guillot (2014) and Torop (2000) for more on interlingual and intersemiotic translation in museum labels.

-

[10]

While the MQB provides some audio-visual interpretive media, and offers audio guides for rent, the text panels remains the most prevalent mode of contextualizing the objects on display and the one that visitors do not have to actively “opt-into” and thus for this article I have focused on the text panels.

-

[11]

The MQB holds many objects from the Dakar-Djibouti Mission organized by the French in 1928-1931, and famously documented in L’Afrique fantôme (Leiris, [1981] 1934). Michel Leiris describes thefts in the night and other modes of coercion that the members of the State-sponsored expedition employed to fulfill their mission of gathering a collection for the France’s Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro. See Sarr and Savoy (2018, pp. 75-104) for more on the provenance of the MQB’s collection.

-

[12]

Several scholars have remarked on the separation between interpretive media and the objects the media is meant to contextualize. See Clifford (2007), Dias (2007, p. 77), Vogel (2007, p. 190), and Dias (2008, p. 306).

-

[13]

The debates have been chronicled in a number of international press outlets (see https://www.theartnewspaper.com/restitution-report-2018 for a list). In addition to debates on repatriation, a collective of artists, scholars, and activists called “Décolonisons l’art!” (DLN [Decolonize Art!) has been active since 2014 and published a collection of essays (Cukierman et al., 2018). DLN runs public workshops and interventions at museum exhibits to discuss how what gets valued in supposedly universal domains like art is shaped by colonial history as well as present-day racism, sexism, and classism.

-

[14]

Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy make this argument in their report (published as Restituer le patrimoine africain, 2018) to French President Emmanuel Macron, who asked the two scholars to evaluate whether and how African objects in France’s national museums should be returned to the African continent. Sarr and Savoy insist on the importance transferring ownership to various actors (communities, organizations, institutions, and state entities) in the countries from which the collections came in order to diversify the forms of knowledge that can be produced with the objects. They also insist that it should be up to such actors to decide if they want any objects back at all, which ones, and what they want to do with them. Along the lines that I raise here, they contend that the goal of repatriation is not a restoration to an authentic past cultural practice, but the activation of future relationships and new modes of meaning making that are drawn from diverse epistemic resources and imaginaries.

-

[15]

See Christidou and Diamantopoulou (2016) for an example of a study that uses these methods.

Bibliography

- Acuff, Joni Boyd and Laura Evans, eds. (2014). Multiculturalism in Art Museums Today. London, Rowman & Littlefield.

- Aldrich, Robert (2005). “Le musée colonial impossible.” In P. Blanchard and N. Bancel, eds. Culture post-coloniale 1961-2006: traces et mémoires coloniales en France. Paris, Editions Autrement, pp. 83-101.

- Asad, Talal (1986). “The Concept of Translation in British Cultural Anthropology.” In J. Clifford and G. E. Marcus, eds. Writing Culture: The Poetics and Politics of Ethnography. Berkeley, University of California Press, pp. 141-164.

- Bal, Mieke (1996). Double Exposures: The Practice of Cultural Analysis. London and New York, Routledge.

- Beaujean-Balthazar, Gaëlle (26 April 2018). Interview. Paris.

- Bennett, Tony (1995). The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. London and New York, Routledge.

- Browning, Frank (2006). “New Paris Art Museum Finds Many Critics.” NPR, August 13. [https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5640888&t=1565689664550].

- Chirac, Jacques (2006). “Déclaration de M. Jacques Chirac, Président de la République, sur le Musée du Quai Branly et le dialogue entre les cultures du Nord et du Sud, à Paris le 20 juin 2006.” [https://www.vie-publique.fr/discours/162270-declaration-de-m-jacques-chirac-president-de-la-republique-sur-le-mus].

- Chrisafis, Angelique (2006). “Chirac Leaves Controversial Legacy with Monument to African and Asian Culture.” The Guardian, 7 April. [https://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/apr/07/arts.france].

- Christidou, Dimitra and Sophia Diamtopoulou (2016). “Seeing and Being Seen: The Multimodality of Museum Spectatorship.” Museum & Society, 14, 1, pp. 12-32.

- Clifford, James (1997). “Museums as Contact Zones.” In Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late 20th Century. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, pp. 198-219.

- Clifford, James (2007). “Quai Branly in Process.” October, 120, pp. 3-23. [https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1162/octo.2007.120.1.3]

- De Becker, Laura (19 December 2017). Email correspondance.

- De l’Estoile, Benoît (2007a). Le goût des Autres. De l’Exposition coloniale aux Arts premiers. Paris, Flammarion.

- De l’Estoile, Benoît (2007b). “L’oubli de l’héritage colonial.” Le Débat, 147, pp. 91-99.

- Debary, Octave and Mélanie Roustan (2012). Voyage au musée du quai Branly. Paris, La Documentation Française.

- Demissie, Fassil (2009). “Displaying Colonial Artifacts in Paris at the Musée Permanent des Colonies to Musée du Quai Branly.” African and Black Diaspora: An International Journal, 2, 2, pp. 65-83.

- Descola, Philippe (2007). “Passage de témoins." Le Débat, 147, pp. 136-153.

- Dias, Nélia (2007). “Le musée du quai Branly : une généaologie.” Le Débat, 146, pp. 65-79.

- Dias, Nélia (2008). “Double Erasures: Rewriting the Part at the Musée du quai Branly.” Social Anthropology/Anthropologie Sociale, 16, 3, pp. 300-311.

- Dibley, Ben (2005). “The Museum’s Redemption: Contact Zones, Government and the Limits of Reform.” International Journal of Cultural Studies, 8, 1, pp. 5-27.

- Duncan, Carol and Alan Wallach (1980). “The Universal Survey Museum.” Art History, 3, 4, pp. 448-469.

- Edwards, Elizabeth, Chris Godsen and Ruth Phillips, eds. (2006). Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums, and Material Culture. Oxford, Berg.

- Guillot, Marie-Noëlle (2014). “Cross-Cultural Pragmatics and Translation: The Case of Museum Texts as Interlingual Representation.” In J. House, ed. Translation: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 73-95.

- Hein, Hilde (2000). The Museum in Transition: A Philosophical Perspective. Washington, Smithsonian Books.

- Hooper-Greenhill, Eileen (1992). Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge. London and New York, Routledge.

- Hutchins, Mary and Lea Collins (2009). “Translations: Experiments in Dialogic Representation of Cultural Diversity in Three Museum Sound Installations.” Museums and Society, 7, 1, pp. 92-109.

- Jules-Rosette, Bennetta and Erica Fontana (2009). “‘Le Musée d’Art au Hasard’: Responses of Black Paris to French Museum Culture.” African and Black Diaspora: An International Journal, 2, 2, pp. 84-100.

- Karp, Ivan and Steven Lavine, eds. (1991). Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display. Washington, Smithsonian Books.

- Karp, Ivan, Christine Muellen Kreamer and Steven Lavine, eds. (1992). Museums and Communities: The Politics of Public Culture. Washington, Smithsonian Books.

- Karp, Ivan, Corinne Kratz, Lynne Szwaja and Tomas Ybarra-Frausto, eds. (2006). Museum Frictions: Public Cultures/Global Transformations. Durham, Duke University Press.

- Kress, Gunther (2011). “Multimodal Discourse Analysis.” In J. P. Gee and M. Handford, eds. Routledge Handbook of Discourse Analysis. London and New York, Routledge, 35-50.

- Kress, Gunther and Theo Van Leeuwen (2001). Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication. London, Arnold.

- Latour, Bruno, ed (2007). “Le musée: espace laïc, espace rituel, espace multiple?” In Le Dialogue des cultures: Actes des rencontres inaugurales du Musée du Quai Branly. Musée du quai Branly, Paris, pp. 145-76.

- Lebovics, Herman (2010). “Le Musée du quai Branly. Politique de l’art de la postcolonialité.” In N. Bancel et al., eds. Ruptures postcoloniales. Les nouveaux visages de la société française. Paris, La Découverte, pp. 443-454.

- Leiris, Michel (1981 [1934]). L’Afrique fantôme. Paris, Gallimard.

- Liu, Lydia, ed. (2000). Tokens of Exchange: The Problem of Translation in Global Circulation. Durham, Duke University Press.

- Longinovic, Tomislav Z. (2002). “A Manifesto of Cultural Translation.” The Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association, 35, 2, pp. 5-12.

- Macdonald, Susan (2003). “Museums, National, Postnational, and Transcultural Identities.” Museums and Society, 1,1, pp. 1-16.

- Mack, John (2002). “Exhibiting Cultures’ Revisited: Translation and Representation.” Folk, 43, pp. 99-109.

- Martin, Stéphane (2007). “Un musée pas comme les autres : un entretien avec Stéphane Martin.” Le Débat, 147, pp. 5-22.

- Mudimbe, V.Y. (1988). The Invention of Africa: Gnosis, Philosophy, and the Order of Knowledge. Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

- Mudimbe, V.Y. (1994). The Idea of Africa. Bloomington, Indiana University Press.

- Musée du quai Branly (2015). “Musée du quai Branly : là où dialoguent les cultures.” [Brochure institutionelle]. [http://www.quaibranly.fr/fileadmin/user_upload/1-Edito/6-Footer/8-Missions-et-fonctionnement/BROCHURE_INSTIT_2015_BD_PL_INT-v2.compressed.pdf].

- Mwangi, Evan Maina (2017). Translation in African Contexts: Postcolonial Texts, Queer Sexuality, and Cosmopolitan Fluency. Kent, Kent State University Press.

- Naumann, Peter (2006). “Making a Museum: ‘It Is Making Theater, not Writing Theory’: An Interview with Stéphane Martin, Président-directeur général, Musée du quai Branly.” Museum Anthropology, 29, 2, pp. 118-127.

- Neather, Robert John (2005). “Translating the Museum: On Translation and (Cross-)cultural Presentation in Contemporary China.” In J. House, ed. Translation and the Construction of Identity. Seoul, IATIS, pp. 180-197.

- Oyeyemi, Helen (2016). What is Not Yours is Not Yours. New York, Penguin Books.

- Pezzini, Isabella (2015). “Paris, Quai Branly. Le dialogue des natures et des cultures.” Actes Sémiotiques, 118, 30 January. [https://www.unilim.fr/actes-semiotiques/5367].

- Pratt, Mary Louise (2010). “Response.” Translation Studies, 3, 1, pp. 95-107.

- Price, Sally (1989). Primitive Art in Civilized Places. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

- Price, Sally (2007). Paris Primitive: Jacques Chirac’s Museum on the Quai Branly. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

- Quinn, Traci and Marianna Pegno (2014). “Collaborating with Communities: New Conceptualizations of Hybridized Museum Practice.” In J. B. Acuff and L. Evans, eds. Multiculturalism in Art Museums Today. London, Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 67-80.

- Ravelli, Louise J. (2006). Museum Texts: Communication Frameworks. London and New York, Routledge.

- Roberts, Mary Nooter (2008). “Exhibiting Episteme: African Art Exhibitions as Objects of Knowledge.” In K. Yosida and J. Mack, eds. Preserving the Cultural Heritage of Africa: Crisis or Renaissance? Oxford, James Currey, pp. 170-186.

- Sarr, Felwine and Bénédicte Savoy (2018). Restituer le patrimoine africain. Paris, Philippe Rey.

- Sauvage, Alexandra (2007). “Narratives of Colonisation: The Musée du quai Branly in Context.” reCollections: Journal of the National Museum of Australia, 2, 2, pp. 135-152.

- Sturge, Kate (2016 [2007]). Representing Others: Ethnography, Translation, and Museums. London and New York, Routledge.