Résumés

Summary

Income inequality has risen in Canada with the decline in union density and, thus, in union influence. Both trends have occasioned various proposals to reform federal and provincial labour relations systems, especially those aspects concerning certification. However, most proposals have been based on minor modifications to the Wagner Model of exclusive, majoritarian representation. To realize the full potential of these reform proposals, including, importantly, the likes of ‘broad-based bargaining,’ we contend that union membership should be the default option for new workers. Such a change would enable these proposals to increase absolute and relative levels of union membership, thereby providing the organizing resources (financial, human) required for much higher levels of union influence. In this study, we show that those living in Canada generally support union membership by default and would not opt out afterwards. We believe this popular support justifies making union membership automatic for new workers.

Abstract

Union density has declined in Canada and, with it, wage inequality has risen, occasioning various proposals to reform the certification systems operating provincially and federally. However, such proposals are ordinarily based on only minor changes to the Wagner Model. We contend that to realize the full potential of these proposals, union membership by default is required to increase union membership levels. In this study, we show that those living in Canada generally support union membership as the default option and would not opt out afterwards. We believe this popular support justifies more comprehensive study of the proposal to make union membership automatic for new workers.

Keywords:

- Unions,

- certification,

- union membership,

- labour relations,

- collective bargaining

Résumé

L’inégalité des revenues s’accroît au Canada avec la baisse de la syndicalisation et, ainsi, celle de l’influence des syndicats. Ces deux tendances ont donné lieu à diverses propositions de réforme qui surgissent autant au niveau fédéral qu’aux niveaux provinciaux et qui concernent surtout l'accréditation syndicale. Cependant, la plupart d’entre elles préconisent des modifications mineures du modèle Wagner de représentation exclusive et majoritaire. Pour réaliser le plein potentiel de ces propositions, y compris, ce qui est important, la négociation plus ou moins sectorielle, nous soutenons que l'adhésion à un syndicat devrait être l'option par défaut pour les nouveaux travailleurs. Les réformes proposées permettraient ainsi d’hausser les niveaux absolus et relatifs d'adhésion syndicale, fournissant de ce fait les ressources d'organisation (financières, humaines) nécessaires pour augmenter considérablement l’influence des syndicats. Dans cette étude, nous montrons que les Canadiens appuient généralement l'adhésion à un syndicat par défaut et ne s’en retireraient pas par la suite. Nous estimons que ce soutien populaire justifie qu’on étudie de manière plus complète la proposition d’automatiser l’adhésion syndicale des nouveaux travailleurs.

Mots-clés :

- Syndicats,

- accréditation,

- membership,

- relations de travail,

- négociation collective

Corps de l’article

1. Introduction

We contend that the significant reversal in the fortunes of unions, as the primary means of reducing wage inequality, requires making union membership the default option for workers. In this article, we begin by examining the current situation of union certification in Canada. We then explain the union membership default and set out its virtues. From there, weexamine and then analyze data on the level of support for this option in Canada. We conclude by suggesting that, while there are qualifications to be borne in mind, there is a need for fuller study of the potential for such a change to Canadian labour relations.

1.1 Union Decline in Canada

From the mid-1970s onwards, union density has been significantly higher in Canada than in the United States. In 1984, it was 35 percent in Canada compared to 19 percent in the United States. By 2004, the figures were respectively 32 percent and 14 percent and, by 2021, 31 percent and 10 percent,[1] a sign of growing divergence. This comparison militates against a more profound recognition that density in Canada fell from a peak of 38 percent in 1981 to a low of 29 percent in 2014 before increasing slightly again.[2] Union decline has been observed across all provinces, economic sectors, occupations and genders. The long-term downward trend has been more obvious for men, among whom union density declined 20 percent from 1981 to 2012, and for the private sector, where it declined 16 percent from 1981 to 2012 (Legree et al., 2019:333). To take one extreme, for instance, union density dropped from 55 percent in 1981 to 28 percent in 2012 for men in British Columbia (Legree et al., 2019:333).

1.2 Unions and Income Inequality

Unions have a clear levelling effect on incomes. Their decline has, thus, played a key role in the growth of Canadian income inequality since the mid-1970s, albeit not in a linear fashion (Green et al., 2017) and not reaching American levels (Card et al., 2004). Unions are democratic by law and egalitarian by convention, often with formal or informal links to a left-wing political party (e.g., the New Democratic Party of Canada). As such, they use their economic power to push the interests of those they represent, especially relatively low wage earners and the disadvantaged. International evidence indicates that unions successfully negotiate higher wages (Bryson, 2014) and fringe benefits (Kristal, Cohen, and Navot, 2020). For example, the American union wage premium has remained at a steady 15-20 percent since the 1930s, despite the last four decades of union decline (Farber et al., 2018). For the lowest paid workers, the union wage premium is even higher at 30-40 percent (Card, 2001; Card, Lemieux, and Riddell, 2020). On the other hand, egalitarian union pay norms have resulted in lower compensation levels for executives (Huang et al., 2020). Unions, thus, flatten the pay hierarchies within firms. With sectoral bargaining, they also smooth pay differentials among firms, in part to prevent low-wage competition from undermining higher union wages (Card et al., 2020; Metcalf, Hansen, and Charlwood, 2001). Non-unionized employers will also raise the pay levels of their employees when they are in close proximity to unionized employers, in order to reduce the attractiveness of unionization and remain competitive when hiring (Denice and Rosenfeld, 2018). In aggregate, unions shift monetary resource, i.e., wealth from profits to wages and salaries (Doucouliagos and Laroche, 2009). Research comparing regions or countries with different rates of unionization also shows that unions successfully lobby for social programs and policies that benefit the poor more than the middle class or the rich (Ahlquist, 2017; VanHeuvelen and Brady, 2022). Without unions, there would be fewer and smaller re-distributive social programs. In the long run, a sustained fall of union density threatens to undo the income-flattening effects that unions have produced in the labour market and through social programs.

1.3 Deficiencies in the Labour Relations System

In response to falling union density, there has been increasing debate from the 1990s onwards about reforming the so-called Wagner Model of labour relations common to all Canadian jurisdictions. That model first appeared in the 1935 National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) of the United States and was then adopted by the Canadian federal government in 1944, to be followed later by all ten provinces (Fudge and Glasbeek, 1995). The Wagner Model, in all its versions, enables a single union to establish an exclusive right to represent a particular bargaining unit of workers, usually defined as the workplace or enterprise, if it can win a majority of votes in an election (Gomez, 2016). A dwindling number of Canadian jurisdictions also enable a union to establish the same exclusive right to represent via the “card check” process, while requiring that the level of support from the bargaining unit be greater than a majority (Gomez, 2016).

Several governments have reviewed their labour relations laws in recent decades (Slinn, 2020). These reviews have helped clarify the principal deficiencies in the Wagner Model that have contributed to union decline. Gomez (2016) described several of them, as follows, in a report prepared for the Ontario Government in the 2015 Changing Workplaces Review. First, all new employers (and workplaces) are non-unionized by default: they are non-unionized initially and remain so unless organized by a union (Gomez, 2016). They are legal autocracies, inasmuch as no formal channels are available for employee voice, apart from whatever the employer establishes and allows (Weiler, 1990). Indeed, non-unionized employers, in common law, have a unilateral right to manage their employment relations as they see fit, and the employees a corresponding duty to obey whatever employers decide in this regard (Harcourt et al., 2019).

Second, to maintain, let alone increase, union density, the main challenge for Canadian unions is to unionize the non-unionized workplaces (Gomez, 2016). Retention of existing members at unionized workplaces is not the issue, as decertification elections are rare under Wagner-based systems, at least those offering first contract arbitration (Baker, 2012). Employer resistance to certification is now the norm (Bentham, 2002; c.f., Thomason and Pozzebon, 1998). In addition, surveys suggest that more than 90 percent of current union members are happy to remain as such (Gomez, 2016:18). Persuading current members to stay is relatively easy. Conversely, persuading outsiders, i.e., non-members to join is difficult, as unions are an “experience good”—a good or service whose quality cannot be ascertained prior to buying (Nelson, 1970). Much of what unions offer (e.g., employment security, protection from arbitrary treatment) is intangible and, therefore, indeterminate; it must be experienced to be fully appreciated (Gomez and Gunderson, 2004). Union representation is, thus, difficult to sell to non-unionized workers, an increasing proportion of whom have never experienced union membership, especially in poorly unionized private-sector services (Bryson and Gomez, 2005). Nevertheless, there is still a representation gap: those who want to join a union, approximately half the Canadian workforce, greatly outnumber those who want to remain in one (Freeman et al., 2007).

Third, the union certification process is long, complicated and costly, and it has become increasingly so with elections now mandatory in most Canadian jurisdictions (Gomez, 2016). Only large national and international unions can normally afford the time and resources necessary to conduct a lengthy campaign, to recruit supporters “on the cards,” and then to make the appropriate submissions to the labour relations board. Given the heavy demands of this process, a union will not normally launch an organizing drive unless it is confident of winning overwhelming majority support.

Fourth, Canadian employers, much like their American counterparts, have negative attitudes toward unions (Campolieti et al., 2007, 2013), no doubt in part because unionization normally leads to lower profits and share prices (Bronars and Deere, 1994). Furthermore, because the egalitarian pay norms of unionized firms pressure corporate boards to offer chief executives lower pay, the top managers are incentivized to resist unionization (Gomez and Tzioumis, 2013). Motivated by a desire to exclude unions, Canadian managers have used various soft and hard approaches to cajole and coerce their employees into staying non-unionized (Thomason and Pozzebon, 1998; Riddell, 2001; Johnson, 2002, 2004). Such practices are less often overtly hostile and aggressively anti-union in Canada than in the United States. The reason has to do more with cross-national differences in the certification process, including a faster process and higher fines for noncompliance in Canada, than with more pro-union employer attitudes (Campolieti et al., 2013).

Fifth, it is harder to organize the smaller workplaces with precarious workforces that represent a growing share of the modern economy, especially in private-sector services such as retail and hospitality (MacDonald, 1997; Willman, 2001). Here, work is generally low-paid and part-time, casual and/or short-term. The workplace is normally too small to “take wages out of competition” and offer any economies of scale in the delivery of union services (MacDonald, 1997). Small size and irregular hours also mean no economies of scale in organizing via mass gatherings or townhall-type meetings, for example, which would have been typical of such campaigns at large manufacturing plants in the past (Doorey, 2013; MacDonald, 1997). Since managers can also more readily observe what workers are doing in a smaller workplace, organizing is harder to carry out in secret, and workers are more vulnerable to management retaliation for supporting the union (MacDonald, 1997). Moreover, management retaliation can at least appear to be lawful and, thus, legitimate, as with casual workers having their hours cut or temporary workers not having their contracts renewed (MacDonald, 1997). Thus, successful union campaigns, to the limited extent they occur at all, often rely on activist worker-insiders to recruit co-workers in the face of intense opposition from management, as at Starbucks in the United States.

Reforms have been proposed to fix one or more of the above issues. For instance, widespread re-adoption of certification “on the cards” would accelerate the certification process and limit employer opportunities for mounting opposition efforts. Dropping the majority support requirement and allowing minority representation would make it easier for any given bargaining unit to obtain representation rights, even if on a members-only basis. Broader-based bargaining via the Baigent-Ready Model would enable smaller bargaining units (i.e., with fewer than 50 workers), once certified, to combine together to bargain for a single multi-establishment or even to obtain a multi-employer collective agreement. Likewise, the entire Wagner Model could be augmented with a parallel system of weaker, but more universal, employee representation rights, which might include worker representatives at the shop-floor level and works councils at the establishment level. However attractive such reforms might seem, much of the labour movement remains reluctant to abandon the predictability and security of the Wagner Model (see Slinn, 2020). In fact, some unions, fearing that any legislative change would favour the employer, have even attempted to constitutionalize the Wagner Model via freedom of association cases taken to the Supreme Court of Canada (Doorey, 2020).

1.4 Union Membership by Default

The Wagner Model needs to be overhauled and reinvigorated so that unions may achieve the following goals: (1) more easily establish representation rights in non-unionized workplaces/sectors/industries; (2) rapidly recruit union members; and (3) broaden bargaining coverage to encompass entire economic sectors. To achieve those goals, a key policy would be union membership by default. It could work as follows. First, a union would be certified to exclusively represent a given bargaining unit, with as little support as 20 percent in a workplace or 1,000 workers in a sector, proven via an electronic petition. Some “showing of interest” (i.e., 20 percent) from the bargaining unit would justify awarding exclusive representation by demonstrating that the union is serious about representing a particular group of workers and has some capacity to do so. A 50 percent threshold to win exclusive representation is neither necessary nor desirable. It de-legitimizes union representation when the union has substantial but less than majority support, and it legitimizes employer efforts to resist unionization within the scope of the law. Instead, the law should send the employer a clear message that union representation is unavoidable.[3]

Second, once formally certified, all employees in the unit (and any future ones) would initially become members by default. They would be informed via email and text. Employee names and contact details would be copied to the union.

Third, all employees would be sent another email and text a short time later, with a link providing access to a web-based short form they may use to opt out. All such communications would be standardized, with short scripts provided by the Ministry of Labour (or the equivalent). The employer would organize and execute these notifications. If the employer failed to do so, the affected employees would be legally presumed union members unless and until both notifications had been completed and the electronic opt-out form submitted. The labour inspector would police employer non-compliance and be empowered to issue on-the-spot infringement notices. Unions could also be similarly empowered to issue improvement notices for noncompliance.

Fourth, any opted-out employee would have his/her own individual agreement with the employer. Evidence suggests that employers would pass on the union’s terms and conditions to non-unionized workers, in order to eliminate the incentive to join the union, to ensure administrative simplicity and to preserve a sense of fairness by having common terms and conditions for unionized and non-unionized workers (Barnes, 2005). All employees would also have to comply with any laws or collective agreements that have a Rand Formula (agency shop) arrangement, which requires non-members to pay union dues (or similar).[4]

If two or more unions together met the 20 percent threshold for a sector-wide unit, they could form a bargaining council to bargain exclusively for a single sectoral agreement, with union representation on the council in line with each union’s overall membership in the bargaining unit. A sectoral agreement would set the minimum terms and conditions for the relevant economic sector, and there would be scope to negotiate additional/improved terms and conditions via workplace-based unions. Workplace- and industry-based agreements would therefore be complementary.

The above reform to the Wagner Model would have several major advantages. First, it would enable unions to organize workplaces, enterprises and even whole sectors relatively quickly, once the minimum thresholds for union support had been met. The rapid spread of union representation would help embed the system before the end of a political election cycle, thus, hindering repeal by conservative governments. Second, it would dramatically lower the costs of organizing, as a union would have to invest fewer resources to sign up a much smaller fraction of a bargaining unit. The funds thereby released would be available for more organizing campaigns. Third, it would help unionize whole sectors, such as retail and hospitality, where organizing costs on a shop-by-shop basis are prohibitive. Likewise, it would empower unions to “take wages out of competition” in such sectors, enabling more dramatic improvements to terms and conditions. Fourth, the system would be representative and, therefore, democratic: union representation would be reflected in high levels of union membership, as most workers would be unlikely to opt out once a union had been established. According to research in law, medicine, marketing, finance and other fields, the default option in any choice is more likely to be selected because the transaction costs of choosing it are lower. Decision-making inertia maintains the default option, thereby, turning it into the norm and creating a perception of loss if that norm is surrendered (Harcourt et al., 2019). Fifth, by normalizing union representation, the system would make it more difficult and less advantageous for employers to resist it. For example, employer failure to comply with the automatic enrolment process would deny and/or delay opportunities to opt out of union membership. Sixth, a modified Wagner Model with union membership by default would be readily defensible in any Section 2(d) Charter of Rights and Freedoms constitutional challenge. It would better protect the freedom to associate by lowering the threshold of support for union certification and by making it easier to join a union without management interference. It would also preserve the freedom not to associate by providing an easily exercised right to opt out.

1.5 Purposes of this Study

This study is the first in North America to examine the public’s views of, and likely reactions to, union membership by default. It has three purposes. The first is to assess the extent of public support for that idea across a broadly representative sample of the entire Canadian population. The second is to assess the extent to which employees would stay in a union if automatically enrolled as members. The third is more specifically to assess support for union membership by default and the intention to stay in the union in terms of unionized/non-unionized status, gender, age, income, public/private sector, and province of residence.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Unionized and Non-Unionized Workers

Individuals normally behave in line with their thoughts (including preferences), as this is both the rational and ethical thing to do (Festinger, 1957). Inconsistency between thoughts and actions would otherwise potentially generate cognitive dissonance, causing anxiety and distress from self-assessments of stupidity and/or immorality. Hence, we expect that employees of a unionized organization (pro-union behaviour) would likely support union membership by default (pro-union thoughts) and remain in the union (also pro-union behaviour). In contrast, employees of a non-unionized organization would likely be non-union by default rather than by choice (Harcourt et al., 2021a). The great majority would never have experienced a union organizing drive and, thus, would not have been asked whether they wanted to join a union (or remain outside one). Perhaps 50 percent of such workers want union representation, but that option is simply not available to them in their workplace (Freeman, Boxall, and Haynes, 2007). In the absence of having a genuine choice, their support for union membership by default and their lack of experience with a union would not necessarily generate cognitive dissonance. No inconsistency is implied in their preferring union representation.

2.2 Gender

Historically, men were more likely than women to be union members. However, unionization of the public sector has increasingly exposed women, in particular, to union representation so that in a number of countries in recent years (like Canada), union density has been higher for women than for men. Concurrently, unionization of the private sector has declined, leaving blue-collar men with less and less experience with union representation. Since union representation is an “experience good” (Gomez and Gunderson, 2004), we would expect more women than men to understand and appreciate the benefits of union representation. Thus, we would expect women to be more likely to support union membership by default and stay in the union.

2.3 Age

It has often been claimed that neo-liberalism has ushered in a more individualistic age where younger people especially are less interested in collective entities, such as unions, than in the past (Phelps-Brown, 1990). However, the evidence suggests younger workers are actually more supportive of unions than their older colleagues (Hodder and Kretsos, 2015), although this tendency could reflect their heavy concentration in precarious jobs rather than any general age effect (Dufour-Poirier and Laroche, 2015; Fiorito et al., 2021). Likewise, their failure to join unions reflects the poor opportunities available to them for union membership in the retail and hospitality sectors, where most young workers are employed (Dufour-Poirier and Laroche, 2015; Fiorito et al., 2021). Hence, we would expect age to be negatively associated with support for making union membership the default option and with intention to remain in the union afterwards.

2.4 Income

Higher-income respondents are more likely to believe they have some influence over their economic situation because of their labour market positions (i.e., professionals, managers, business owners) or educational credentials. Unions are, therefore, more likely to be considered at best unnecessary (i.e., professionals) or at worst a challenge to their financial success (i.e., business owners). Lower-income respondents, by contrast, are more likely to believe they have less control over their financial future and, thus, have a greater need for a union to advance their interests, whether in the workplace or in the legislature (Harcourt et al., 2020). Thus, as incomes rise, we would expect to see less support for union membership by default and less intention to remain in the union afterwards.

2.5 Public Sector

Public and private sectors differ significantly in a number of aspects that influence the desire to join a union. Specifically, employer retaliation for union support is less of a concern in the public sector, as laws, regulations and civil service rules often oblige managers to remain neutral in union organizing campaigns. There is also less of a perceived trade-off between wages and jobs in the public sector, which is less affected by markets, prices, consumers and competitors. Public-sector unions are also seen as more politically effective in influencing employer policies, practices and budgets. As a result, public-sector workers generally view union representation more positively (Fiorito et al., 1996).

2.6 Province

Union density levels have been historically higher in British Columbia and Quebec than in most other provinces.[5] So employees in those provinces should show more support for union membership by default and for remaining in the union afterwards.

3. Methods

3.1 Data Collection

We collected our survey data via interviews conducted by The Vector Poll™ from December 21, 2020 to January 7, 2021. The interviews were with 1,200 adults, 18 years old or older, throughout Canada. Ontario was oversampled to increase the respondent numbers in that province to 600. Vector Research weighted the data in each region of Canada to ensure that the sample was demographically representative of the census population. Respondents were free to complete their interview in English or French. Each interview lasted approximately 15 to 20 minutes. The questions were part of ongoing research on public policy, labour market issues and other topics that The Vector Poll had been carrying out for more than 30 years. The entire survey covered 50 questions, most of which were not about unions or labour relations.

Given a pure probability sample of 1,200, a sampling error with 95 percent confidence is plus or minus 2.8 percentage points, where opinion is divided evenly. The sampling error for the Ontario subsample of 600 is 4.0 percentage points. However, this online interview survey was not based on a probability sample. It was based on demographically representative panels of more than one million Canadians who had chosen to opt in or self-select. It is, thus, impossible to estimate the sampling error.

3.2 Variables

The data were all derived from the answers to the survey interview questions. There were two dichotomous dependent variables. First, the respondents were asked whether they would support (coded as 1) or oppose (coded as 0) a law requiring all workplaces to have union representation and all employees, except senior executives and managers, to be automatically enrolled as union members and pay dues (at the first instance). Second, the respondents were asked to imagine a hiring situation where they had been newly employed and automatically enrolled as a union member (union membership by default), in compliance with a new law. They were then asked whether they would stay in (coded as 1) the union or opt out (coded as 0). Industrial relations scholars (e.g., Montgomery, 1989; Park, McHugh, and Bodah, 2006) have long applied the Theory of Reasoned Action (Fishbein and Azjen, 1975) to explain why workers join unions or vote for a union in a certification election. The central idea is that workers have intentions to achieve certain ends, such as higher wages or better working conditions, which manifest in certain behaviours such as voting for union representation. Empirical research does confirm that the intention to join a union, or vote for one in an election, does accurately predict actual voting or joining. For example, one study showed that 91 percent of votes in a union election were correctly predicted by voting intention (Montgomery, 1989: 278). A meta-analysis of such studies found a 0.79 correlation between voting intention and actual voting in union elections (Premack and Hunter, 1988: 227). Thus, it is consistent with past research to use the intention to stay in the union to predict whether workers would actually remain if and when union membership is made automatic.

We used 12 independent variables. Two dichotomous variables indicated whether the respondent’s workplace was unionized. The first variable, “Union,” indicated that the respondent normally worked for a unionized organization (coded as 1). The second variable, “Non-union,” indicated that the respondent normally worked for a non-unionized organization.[6] Both variables were coded as 0 for any respondent not in paid work (i.e., unemployed, student, retired, homemaker, unable to work).

“Gender” was a dichotomous variable. It was coded as 1 for those who indicated a female gender and as 0 for those who indicated a male or other gender (i.e., “you identify in some other way”).[7]

“Age” was an interval variable for the respondent’s age at the time of the survey. It was derived from the answer to “year of birth.”

“Income” was an ordinal variable for the respondent’s before-tax household income, starting from a low of 1 (for household incomes under $30,000) and increasing one unit for each additional $10,000 in household income under $100,000 (e.g., Income was coded as 8 for household incomes from $90,000 to just under $100,000). Household incomes from $100,000 to just under 120,000 were coded as 9, and household incomes of $120,000 or more were coded as 10.

“Public sector” was a dichotomous variable. It was coded as 1 for public-sector workers and as 0 for private-sector workers, non-profit sector workers, the self-employed or those unsure which sector they were in.

Finally, a number of dichotomous variables indicated the respondent’s province of residence.[8] Relatively few were from the Atlantic provinces (i.e., Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador), each of which has a small population. All respondents from Atlantic Canada were, thus, coded as 1. When the province-related variables involved comparisons with Alberta, the code 0 indicated residents of the province of Alberta.[9]

Data Analysis

Survey data were analyzed statistically using the logistic regression program in SPSS. The 12 independent variables were used to predict “Staying in the union” (versus opting out) and “Support for the union default” (versus opposition). The logistic models assumed the following basic form: log (probability (event)/probability (no event)) = β0 + β1X1 + β2X2 + ... + βnXn .

For “Support for the union default” (Model 1), “event” means support for union membership by default (coded as 1), and “no event” (coded as 0) means opposition. For “Staying in the union” (Model 2), “event” means staying in the union (coded as 1) and “no event” (coded as 0) means opting out. The probability of “event” divided by the probability of “no event” is the odds ratio, i.e., the odds of supporting union membership by default versus opposing it and the odds of staying in the union versus opting out. The independent variables were used to predict the log of each of the odds ratios. The coefficient estimates (i.e., the βs in the above equation) indicate the expected change in this ratio for a one-unit change in the associated independent variable.

4. Results

Table 1 gives, in column 1, the percentage of respondents who would stay in a union, if automatically enrolled, and, in column 2, the percentage who would support union membership by default. For the whole sample, most said they would remain in a union (55.8 percent) and support union membership by default (54.0 percent). Intention to stay in a union was more prevalent among workers in unionized organizations (73.4 percent), residents of Quebec (64.0 percent) and public-sector workers (63.0 percent). It was less prevalent among workers in non-unionized organizations (35.3 percent) and residents of Manitoba (49.0 percent). Support for union membership by default was more prevalent among workers in unionized organizations (72.1 percent), public-sector workers (67.7 percent) and residents of British Columbia (61.0 percent) and Quebec (60.3 percent). The percentage of respondents supporting union membership by default was similar to the percentage intending to stay in a union across most groups. There were three notable exceptions. Manitoba residents (49.0 percent versus 42.9 percent) and Saskatchewan residents (57.1 percent versus 42.9 percent) were much more likely to stay in a union than they were to support union membership by default, whereas non-unionized workers (35.3 percent versus 48.6 percent) were much less likely.

Table 1

Percentage Staying in or Supporting

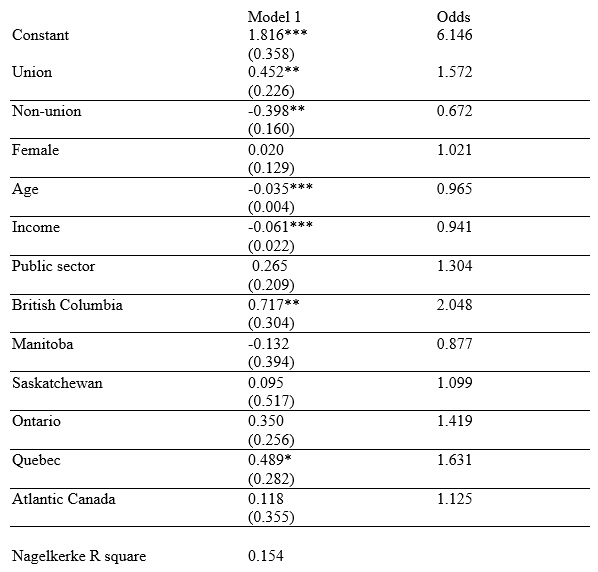

The logistic regression models are outlined in Tables 2 and 3. Model 1 (Table 2) shows the odds of supporting union membership by default rather than opposing it. Model 2 (Table 3) shows the odds of staying in the union rather than opting out.

For Tables 2 and 3, the coefficient estimates of the independent variables are listed in the first column, with standard errors immediately stated below in parentheses. Each coefficient estimate in the first column implies a corresponding odds ratio change, stated in the second column. Positive (negative) statistically significant coefficient estimates indicate an increase (decrease) in the odds for the relevant dependent variable (i.e., “Support for the union default”; “Staying in the union”) in relation to the odds inferred from the coefficient estimate of the constant in the model.

In Table 2, the coefficient of the constant is statistically significant and positive.[10] The coefficient estimate of “Union” is positive and statistically significant, suggesting an increase in the odds of staying in rather than opting out, whereas that for “Non-union” is negative and statistically significant, suggesting a decrease in the odds of staying in rather than opting out. Hence, compared to respondents not normally in paid work, workers at unionized organizations were more likely, and workers at non-unionized organizations less likely, to support union membership by default. For the other independent variables, the coefficient estimates of “Age” and “Income” are both statistically significant and negative. Thus, older or higher-income respondents were less likely to support union membership by default than younger or lower-income respondents. The coefficient estimates of “British Columbia” and “Quebec” are both statistically significant and positive. Thus, British Columbia and Quebec residents were both more likely to support union membership by default than were residents of Alberta. The coefficients for Female, Public Sector and the other provinces are all statistically insignificant. Thus, support for that option was neither more likely nor less likely among women, public-sector workers and Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Ontario and Atlantic residents.

To illustrate the predictions of the model in Table 2, in terms of support versus opposition, let us provide a few examples. First, if you are 46 years old, are out of the workforce, earn a $60,000-$70,000 income and reside in a province other than British Columbia or Quebec, you have roughly even odds of supporting union membership by default (i.e., 6.146 x 0.96546 x 0.9414 = 0.9358), equivalent to a 48.34 percent probability (i.e., 0.9358/1.9358). Second, if you are close to the lower end of support (i.e., 65 years old, non-unionized employer, $120,000 or more income, not a British Columbia or Quebec resident), you have approximately 1:4 odds of supporting union membership by default (i.e., 6.146 x 0.672 x 0.96565 x 0.94110 = 0.2218), equivalent to just an 18.15 percent probability (i.e., 0.2218/1.2218). Third, if you are closer to the upper end (i.e., 18 years old, unionized employer, income less than $30,000, British Columbia resident), you have approximately 10:1 odds of supporting union membership by default (i.e., 6.146 x 1.572 x 0.96518 x 0.9411 x 2.048 = 9.805), equivalent to a 90.74 percent probability (i.e., 9.805/10.805).

Table 2

Predicting support for the Union Default: Coefficient Estimates (Standard Errors)

*** = statistically significant at the 1% level,

** = statistically significant at the 5% level,

* = statistically significant at the 10% level.

In Table 3, the coefficient of the constant is statistically insignificant. The odds of staying in the union rather than opting out were, thus, 1:1, equivalent to a probability of 50 percent.[11] The coefficient estimate of “Union” is statistically significant and positive. The odds of staying in the union versus opting out were, thus, higher for respondents with a unionized employer than for those not normally in paid work. In contrast, the coefficient estimate of “Non-union” is statistically significant but negative. The odds of staying in the union versus opting out were, thus, lower for respondents with a non-unionized employer than for those not normally in paid work. For the other independent variables, the coefficient estimates of “Female,” “British Columbia” and “Quebec” are statistically significant and positive. Women, British Columbia residents and Quebec residents were, thus, more likely to say they would stay in the union than, respectively, men and Albertans. The coefficients for Age, Income, Public Sector, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Ontario and Atlantic Canada are all statistically insignificant. The intention to stay in the union, if membership is provided by default, was, thus, neither lower nor higher for younger individuals, poorer individuals, public-sector workers or residents of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Ontario and the Atlantic provinces.

Table 3

Predicting staying in the union: Coefficient Estimates (Standard Errors)

*** = statistically significant at the 1% level,

** = statistically significant at the 5% level,

* = statistically significant at the 10% level.

To illustrate the predictions of the model in Table 3, in terms of staying in the union versus opting out, let us provide a few examples. First, if you are out of the workforce, female and not a British Columbia or Quebec resident, you have approximately 7:5 odds of staying in the union if membership is provided by default (i.e., 1 x 1.389 = 1.389), equivalent to a 58.14 percent probability (i.e., 1.389/2.389). Second, if you are at the lower end of support (i.e., non-unionized, male, not a British Columba or Quebec resident), you have roughly 1:2 odds of staying in the union (i.e., 0.537 x 1 x 1), equivalent to a 34.93 percent probability (i.e., 0.537/1.537). Third, if you are at the upper end of support (i.e., unionized employer, female, Quebec resident), you have nearly 5:1 odds of staying in the union (i.e., 1.791 x 1.389 x 1.854 = 4.612), equivalent to an 82.18 percent probability (i.e., 4.612/5.612).

5. Discussion

A majority of Canadian respondents supported making union membership the default option and would remain in the union. Moreover, such support existed across all groups despite some important variations. Union members were largely in favour. Nearly three quarters of them supported union membership by default and indicated they would stay in the union. Such support is clearly consistent with their existing union status, since that option would probably increase membership and coverage. On the other hand, approximately a quarter of them opposed membership by default or indicated they would not remain in the union if automatically made a member. No doubt some union members were likely wary of supporting a new and unknown policy, fearing they could lose the security and predictability of the Wagner Model. Some might also be reluctant union members, obliged to join by a union or closed shop clause, and thus happy to say they would opt out and/or oppose membership by default.

Nearly half (48 percent) of the non-unionized workers supported union membership by default, but only 35 percent indicated they would actually remain if they could opt out. The seeming discrepancy might have a number of causes. Many non-unionized workers might support union membership by default because they could see how it would facilitate freedom of association, while, in the absence of membership experience, showing little interest in belonging to a union themselves. They might also be more likely to opt out because they were more likely to fear management disapproval or retaliation. At the very least, union representation might seem inconsistent with longstanding social norms where the default option is non-membership in a union.

Men and women differed little in their support for making union membership the default option, but women were more likely to say they would stay in the union. More women might have been prepared to adapt to the new policy, in this case by not opting out, even if they disapproved of it.

Both younger and lower-income individuals were more likely to support union membership by default than their older and higher-income counterparts, respectively, but not more likely to say they would stay in the union. Greater enthusiasm for membership by default could stem from greater appreciation of the benefits of union representation, especially for workers like themselves. However, their greater vulnerability to management retribution might frighten more of them into opting out even if they favour unionization. In the long-term, of course, they might feel differently once they have experienced the protections of union representation.

Public-sector employment in itself did not seem to affect the respondents’ preferences and intentions. Public-sector workers were more likely to support union membership by default and intend to stay in the union, as noted in Table 1, probably because of such factors as a much higher union density rate, rather than anything to do specifically with the public sector.

Our results also suggest that union membership by default would be better received and lead to a greater number of new union members in British Columbia and Quebec than in the other provinces. This is not surprising. Both provinces have long had greater support for pro-union legislation and have often been governed by social democratic parties sympathetic to unions. Even in federal elections, residents of the two provinces are more likely to vote for a social democratic alternative to the mainstream Liberal and Conservative parties.

The main limitation of our data is the lack of a concrete example that the respondents could evaluate. Union membership by default does not yet exist as a policy “on the ground” in any country. Thus, the respondents were asked about something hypothetical and unfamiliar. We would therefore expect their views to change with actual implementation. Notwithstanding the negative influences of the conservative and business media, we believe that most workers would become more supportive of such a policy over the long term, since unions are an “experience good.” They might become more supportive once they have known it in practice.

6. Implications

We believe that our results are sufficiently encouraging to warrant further study, the ultimate aim being to create an effective mechanism for reducing wage inequality. While we recognize that in Canada, at any rate, some studies suggest that higher union density is not a magic panacea for reducing various types of wage inequality (e.g., Legree et al., 2019:352-353), we believe that union density would greatly increase if union membership were made the default option for new workers. Wage inequality would thus correspondingly decrease, especially if unions established sectoral bargaining units. And, mindful of Haddow’s (2021) conclusion on the limitations of unions using their industrial bargaining power to reduce inequality in Canada, we believe that the introduction of union membership by default would help increase their resources and legitimacy for exercising political influence on income-levelling social policies. Such an option would be a paradigm shift in the country’s institutional framework and public policy on a scale advocated by Rose and Chaison (2001).

Parties annexes

Notes

-

[1]

Union Members — 2021’ https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/union2.pdf In 2021 in Canada, density was 77 percent in the public sector and 15 percent in the private sector compared to 34 percent and 6 percent in the United States.

-

[2]

Unionization rates falling’ https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-630-x/11-630-x2015005-eng.htm

-

[3]

Use of elections for certification could be limited to situations where two or more unions are organizing the same unit simultaneously, and where each has met the 20 percent threshold of support for a “showing of interest.”

-

[4]

Closed and union shops could still be permitted, as under existing laws, but they would require majority support through a ratification vote from the workers of a bargaining unit.

-

[5]

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2013001/article/11878-eng.htm. In recent years, density levels have fallen more precipitously in British Columbia than in other provinces. Its union density level is now lower than the national average.

-

[6]

“Union” and “Non-union” included regular workers plus those who were temporarily laid off and awaiting recall. The reference category (“0”) also included a small number (n=37) of individuals who were unsure whether their organization was unionized.

-

[7]

Just seven individuals identified their gender as “in some other way” (i.e., neither male nor female). Given their small number, we will discuss gender in terms of males and females only.

-

[8]

To keep the sample representative of the population, none of the respondents was from one of the very sparsely populated three territories, and none lived outside Canada.

-

[9]

The latter findings for these province-related variables all involve comparisons with Alberta, the least unionized of Canada’s large provinces.

-

[10]

The coefficient of the constant in this model indicates the odds of support versus opposition, when all independent variables assume a zero value. However, in this particular instance, one cannot interpret the constant by itself, as the Age and Income variables never assume a zero value.

-

[11]

The coefficient of the constant in this model indicates the odds of staying in the union rather than opting out, when all the independent variables assume a zero value.

References

- Ahlquist, J. (2017). ‘Labor Unions, Political Representation, and Economic Inequality’, Annual Review of Political Science, 20:409-432.

- Baker, D. (2012). ‘Canada Proves the Decline of Unions is not Inevitable’, http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2012/09/201291103825936625.html

- Barnes, R. (2005). ‘An Analysis of Passing On in New Zealand: The Employer’s Duty to Manage Concurrent Bargaining in a Mixed Workplace’, Auckland Law Review, 11-56-85.

- Bentham, K. (2002). ‘Employer Resistance to Union Certification: A Study of Eight Canadian Jurisdictions’, Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, 57/1:159-187/

- Bronars, S. and Deere, D. (1994). ‘Unionization and profitability: Evidence of spillover effect’, Journal of Political Economy, 102/6:1281-1287.

- Bryson, A. (2014). ‘Union wage effects: What are the economic implications of union wage bargaining for workers, firms and society’ IZA World of Labor doi: 10.15185/izawol.35

- Bryson, A. and Gomez, R. (2005). ‘Why Have Workers Stopped Joining Unions? Accounting for the rise in never-membership in Britain’, British Journal of Industrial Relations, 43/1:67-92.

- Campolieti M., Riddell, C. and Slinn, S. (2007). ‘Labor law reform and the role of delay in union organizing: Empirical evidence from Canada’, Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 61/1:32–48.

- Campolieti, M., Gomez, R. and Gunderson, M. (2013). ‘Managerial Hostility and Attitudes Towards Unions: A Canada-US Comparison’, Journal of Labor Research, 34/1:99–119.

- Card, D., Lemieux, T. and Riddell, W. (2004). ‘Unions and wage inequality’, Journal of Labor Research, 25/3:519–559.

- Card, D. (2001). ‘The Effect of Unions on Wage Inequality in the United States Labor Market,’ Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 54/2:296-315.

- Card, D., Lemieux, T., and Riddell, W.C. (2020). ‘Unions and wage inequality: The roles of gender, skill and public employment,’ Canadian Journal of Economics, 53/1:140-173.

- Denice, P. and Rosenfeld, J. (2018). ‘Unions and Nonunion Pay in the United States, 1977-2015’, Sociological Science, 5:541-561.

- Doorey, D. (2013). ‘Why Unions Can’t Organize Retail Workers’, Law of Work Blog. http://lawofwork.ca/?p=7061

- Doorey, D. (2020). ’Clean Slate and the Wagner Model: Comparative Labor Law and New Plurality’, Employee Rights and Employment Policy Journal, 24/1:95-108.

- Doucouliagos, H. and Laroche, P. (2009). ‘Unions and Profits: A Meta-Analysis’, Industrial Relations, 48/1:146-180.

- Dufour-Poirier, M. and Laroche, M. (2015). ‘Revitalising Young Workers’ Union Participation: A Comparative Analysis of Two Organisations in Quebec Canada’, Industrial Relations Journal, 44/3:418-33.

- Farber, H., Herbst, D., Kuziemko, I.,and Naidu, S (2018). ‘Unions and Inequality over the Twentieth Century: New Evidence from Survey Data,’ NBER Working Paper 24587, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- Festinger, L. (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford University Press, Palo Alto, CA.

- Fiorito, J., Gallagher, D., Russell, Z., and Thompson, K. (2021). ’Precarious Work, Young Workers and Union-Related Attitudes: Distrust of Employers, Workplace Collective Efficacy, and Union Efficiency’, Labor Studies Journal, 46/1:5-32.

- Fiorito, J., Stepina, L. and Bozeman, D. (1996). ‘Explaining the Unionism Gap: Public-Private Sector Differences in Preferences for Unionization’, Journal of Labor Research, 17/3:463-478.

- Fishbein, M., and Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research, Reading, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley.

- Foster, J., Barnetson, B. and Matsunaga-Turnbull, J. (2018). ‘Fear Factory: Retaliation and Rights Claiming in Alberta, Canada’, Journal of Workplace Rights, 8/1:1-12.

- Freeman, R., Boxall, P. and Haynes, P. (2007). What Workers Say: Employee Voice in the Anglo-American Workplace. Ithaca, NY: ILR Press.

- Fudge, J. and Glasbeek, H. (1995). ’The Legacy of PC 1003’, Canadian Labour and Employment Law Journal, 3/3:357-400.

- Gomez, R. (2016). Employee Voice and Representation in the New World of Work: Issues and Options for Ontario, Ministry of Labour, Government of Ontario, Queen’s Printer for Ontario, Ottawa.

- Gomez, R. and Gunderson, M. (2004). ‘The Experience-Good Model of Union Membership.’ in The Changing Role of Unions. Phanindra V. Wunnava (ed). New York: M.E. Sharpe, pp. 92-115.

- Gomez, R. and Tzioumis, K. (2013). ‘Unions and Executive Compensation’ Centre for Economic Performance Discussion Paper. CEPDP 720. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=1032796

- Green, D., Riddell, C. and St-Hilaire, F. (2017). ‘Income Inequality in Canada: Driving Forces, Outcomes and Policy’ in in Green, D., Riddell, C. and St-Hilaire, F. (eds.) Inequality: The Canadian Story, Institute for Research on Public Policy, Montreal, pp. 1-73.

- Haddow, R. (2021). ‘Do Unions Still Matter for Redistribution? Evidence from Canada’s Provinces’, Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, 76/3:485–517.

- Hodder, A. and Kretsos, L. (2015). ‘Young Workers and Unions: Context and Overview’ in Young Workers and Trade Unions, edited by Andy Hodder and Lefteris Kretsos, pp. 1-15. London: Palgrave.

- Huang, Q. Jiang, F. Lie, E. and Que, T. (2017). ’The Effect of Labor Unions on CEO Compensation,’ Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 52/2:553-582.

- Johnson, S. (2002). ‘Card Check or Mandatory Representation Vote? How the type of union recognition procedure affects union certification success?’, The Economic Journal, 112/2:344–361.

- Johnson S. (2004). ‘The Impact of Mandatory Votes on the Canada–US Union Density gap: A note’, Industrial Relations, 43/2:356–363.

- Kristal, T. Cohen, Y. and Navot E. (2020). ‘Workplace Compensation Practices and the Rise in Benefit Inequality,’ American Sociological Review, 85/2:271-297.

- Legree, S., Schirle, T. and Skuterud, M. (2019). ‘Can Labour Relations Reform Reduce Wage Inequality?’ in Green, D., Riddell, C. and St-Hilaire, F. (eds.) Inequality: The Canadian Story, Institute for Research on Public Policy, Montreal, pp. 325-360.

- MacDonald, D. (1997). ‘Sectoral Certification: A Case Study of British Columbia’, Canadian Labour and Employment Law Journal, 5/2:243-286.

- Montgomery, R. (1989). ‘The Influence of Attitudes and Normative Pressures on Voting Decisions in a Union Certification,’ Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 42/2:262-279.

- Nelson, P. (1970). ‘Information and Consumer Behavior’, Journal of Political Economy, 78/2:311-329.

- Park, H., McHugh, P. and Bodah, M. (2006). ‘Revisiting General and Specific Union Beliefs: The Union-Voting Intentions of Professionals’, Industrial Relations, 45/2:270-289.

- Phelps-Brown, H. (1990). ‘The Counter-Revolution of our Time’, Industrial Relations, 29/1:1-14.

- Premack, S. and Hunter, J. (1988). ‘Individual Unionization Decisions,’ Psychological Bulletin, 103/2:223-234.

- Riddell, C. (2001). ‘Union Suppression and Certification Success’, Canadian Journal of Economics, 34/2:396-410.

- Rose, J. and Chaison, G. (2001). ‘Unionism in Canada and the United States in the 21st Century: The Prospects for Revival’, Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, 56/1:34-65.

- Slinn, S. (2020). ’Broader-Based and Sectoral Bargaining in Collective-Bargaining Law Reform: A Historical Review’, Labour/Le Travail, 85/1:13-51

- Thomason, T. and Pozzebon, S. (1998). ‘Managerial Opposition to Union Certification in Quebec and Ontario’, Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, 53/4:750-771.

- Vanheuvelen, T. and Brady, D. (2022). ‘Labor Unions and American Poverty,’ Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 75/4:891-917.

- Weiler, P. (1990). Governing the Workplace: The future of labor and employment law, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Willman, P. (2001). ‘The Viability of Trade Union Organization: A Bargaining Unit Analysis’, British Journal of Industrial Relations, 39/1:97–117.

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Percentage Staying in or Supporting

Table 2

Predicting support for the Union Default: Coefficient Estimates (Standard Errors)

Table 3

Predicting staying in the union: Coefficient Estimates (Standard Errors)

10.7202/006714ar

10.7202/006714ar