Résumés

Summary

This study examines how the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing university management control strategies have influenced higher education workers’ job security, stress and happiness. The primary quantitative and qualitative data are drawn from a survey of fourteen universities across Australia and Canada, supplemented by secondary research. The analysis examines institutional and worker responses to the pandemic, and resulting conflict over financial control at the macro (sector), meso (university) and micro (individual) levels.

At the macro level, university responses were shaped by public policy decisions at both national and subnational layers of the state, and the higher education sector in both countries had a distinctly neoliberal form. However, Australian universities were exposed to greater financial pressure to cut job positions, and Australian university management might have been more inclined to do so than Canadian universities overall.

Different institutional support for unionism at the macro level influenced how university staff were affected at the meso and micro levels. Restructuring at the universities across both countries negatively impacted job security and career prospects, in turn leading to reduced job satisfaction and increased stress. Although working from home was novel and liberating for many professional staff, it was a negative experience for many academic staff.

Our analysis demonstrates that the experiences of university staff were influenced by more than the work arrangements implemented by universities during the COVID-19 pandemic. The approaches of universities to job protection, restructuring and engagement with staff through unions appeared to influence staff satisfaction, stress and happiness.

Our findings extend the literature that documents how university staff routinely challenge neoliberalization processes in a variety of individual and collective actions, particularly in times of crisis. We argue that theorization of struggles over control of labour should be extended to account for struggles over control of finance.

Abstract

We studied 14 universities across Canada and Australia to examine how the COVID-19 crisis, mediated through management strategies and conflict over financial control in higher education, influenced workers’ job security and affective outcomes like stress and happiness. The countries differed in their institutional frameworks, their union density, their embeddedness in neoliberalism and their negotiation patterns. Management strategies also differed between universities. Employee outcomes were influenced by differences in union involvement. Labour cost reductions negotiated with unions could improve financial outcomes, but, even in a crisis, management might not be willing to forego absolute control over finance, and it was not the depth of the crisis that shaped management decisions.

Keywords:

- COVID-19,

- Canada,

- Australia,

- control,

- management strategies,

- university workers,

- union,

- financial control,

- comparative analysis,

- negotiation pattern

Résumé

Cette étude examine comment la pandémie de COVID-19 et les stratégies mises en oeuvre par la gestion universitaire ont influencé la sécurité d'emploi, le stress et le bonheur des travailleurs de l'enseignement supérieur. Les données quantitatives et qualitatives primaires proviennent d'une enquête menée dans quatorze universités en Australie et au Canada, complétée par des recherches secondaires. L'analyse examine les réponses des institutions et des travailleurs à la pandémie, ainsi que les conflits qui en résultent en matière de contrôle financier et ce, tant aux niveaux macro (secteur), méso (université) et micro (individu).

Au niveau macro, les réponses des universités ont été façonnées par les politiques publiques de l'État aux niveaux national et infranational. Dans les deux pays l’approche avait une forme nettement " néolibérale ". Toutefois, les universités australiennes ont été davantage exposées à la pression financière en faveur des suppressions d'emplois, et la direction de ces universités a peut-être été plus encline à procéder à des mises à pied que l'ensemble des universités canadiennes.

Les différences au niveau du soutien institutionnel au syndicalisme au niveau macro ont influencé la manière dont le personnel universitaire a été affecté aux niveaux méso et micro. La restructuration des universités, dans les deux pays, a eu un impact négatif sur la sécurité d'emploi et les perspectives de carrière, ce qui a entraîné une diminution de la satisfaction professionnelle et une augmentation du stress. Pour de nombreux membres du personnel professionnel, le travail à domicile était nouveau et libérateur, tandis que pour d’autres membres du personnel universitaire, le travail à domicile était une expérience négative.

Notre analyse démontre que les expériences du personnel universitaire ont été influencées par d'autres facteurs que les modalités de travail mises en place par les universités pendant la pandémie de COVID-19. Les approches des universités en matière de protection de l'emploi, de restructuration et d'engagement avec le personnel par le biais des syndicats semblent influencer la satisfaction, le stress et le bonheur du personnel.

Nos résultats s'inscrivent dans le prolongement de la littérature qui documente la manière dont les processus de néolibéralisation sont régulièrement contestés par le personnel universitaire dans le cadre de diverses actions individuelles et collectives, en particulier en temps de crise. Nous soutenons que la théorisation des luttes pour le contrôle du travail devrait être étendue aux luttes pour le contrôle des finances.

Mots-clefs:

- Covid-19,

- Canada,

- Australie,

- Contrôle,

- Stratégies de gestion,

- Travailleurs universitaires,

- Syndicat,

- contrôle financier,

- Analyse comparative,

- négociation collective

Corps de l’article

Introduction

This article examines the pandemic’s effect on universities and how university management control strategies through that crisis influenced key outcomes in higher education, including workers’ job security, stress and happiness. In the implementation of management strategies, worker resistance to a lack of financial control played, at times, an important role. There is extensive debate on how changes to the macro-political economy, managerial cost-control strategies, and worker resistance to these strategies affect the degradation of working conditions in general (Baccaro and Howell, 2017; Standing, 1997), and in higher education in particular (Ross et al., 2020; Giroux, 2002). Our study makes several contributions. First, it situates these dynamics in the COVID-19 health and economic crisis. Second, it responds to Vidal and Hauptmeier’s (2014) call for a richer dialogue between comparative political economy and labour process theory. Third, we identify conflict over resource and financial control as an issue of particular interest during crises, arguing that insufficient attention has been given to the interaction between issues of financial control and workplace industrial relations. Fourth, we show adverse effects of restructuring from certain types of managerial strategies.

We undertook a mixed methods study using quantitative and qualitative data from 14 universities across Canada and Australia. We focused our analysis on two key types of workers: administrative and professional staff, who, importantly, are comparable to many private service sector workers; and academic staff or faculty, who possess and defend historically high levels of autonomy. Both groups are unevenly unionized. Australia and Canada are similar in that they have strong institutional legacies that support public education but largely fall within the liberal market economy cluster. We asked two questions:

What effects did the COVID-19 pandemic have on the university systems in Canada and Australia, and how did actors in those systems respond?

How did responses at the workplace level affect employees’ security, stress and happiness?

To situate our work, we will first consider the literatures on comparative political economy and labour process theory and how the COVID-19 pandemic affected worker insecurity and the behaviour of labour and management. We will then outline our methodology and the outcomes of our analysis. We will conclude with some reflections on crisis processes, the links between institutional and organizational level processes and some implications for the treatment of resource and financial control in labour process theory.

1. Literature Review and Framework

Our research interrogates theoretical perspectives drawn from comparative political economy and labour process theory to explain how responses to the COVID-19 crisis affected workers in higher education. Worker resistance should be situated within its macro-structural context, and through this we can identify how the control of financial resources impacts workers’ experiences. Comparative political economists have shown how macro-level neoliberalization processes eroded the postwar social compact and weakened both collective and individual worker power in favour of management (Streeck, 2014). These neoliberalization processes were instigated by crises. However, the COVID-19 crisis differed from recent economic crises in its effects on capital accumulation (Dobbins, 2020; Susskind and Vines, 2020). As a public health emergency, governments curtailed (rather than expanded) the amount of work otherwise performed in the economy and thus introduced limits on their accumulation agendas, which generated fiscal challenges that left public services vulnerable to austerity.

While the political economy literature has been largely macro in focus, labour process theory gives a central position to issues of control at the organizational level, in particular how managerial strategies to commodify workers and worker responses to those efforts translate into the dialectic of consent and resistance (Braverman, 1974; Thompson and Newsome 2004). Critically, the labour process debate focuses on the control of labour and struggles at the point of production (Thompson and Newsome, 2004). Other issues encompassed by labour process theory, such as the role of skills and technology in labour’s conversion into a commodity, speak to the function of labour in capital accumulation, and in generating financial surplus. However, labour process theory speaks less to the battle over the use of that surplus, which might be for dividends but also for investment in technology or skills development itself, or for the provision of management perquisites.

A dialogue between comparative political economy and labour process theory would provide a lens through which we can examine the dialectic of financial control, which has critical impacts on work in higher education. By financial control, we are referring to decisions about the allocation and withdrawal of resources and the transparency of those decisions. This goes beyond decisions about wages, employment conditions or retrenchments to the range of matters, from marketing to research, from overseas activities to surplus retention, between disciplines and between expertise levels, that a university (or other organization) might spend money on, but which might also immediately or eventually influence the amount that can be allocated to labour. Labour process theory is comfortable in dealing with managerial decision-making over retrenchments and wages, but it is less familiar with debates about control over budgetary and financial decision-making. While the dynamics of control and resistance matter to working conditions, in higher education (Collier 2012) the broader battle over financial control may at times be critical.

In the higher education setting, worker contestation interacts with the core processes that have shaped work outcomes. One such process is the erosion of higher education as a public good via State disinvestment. A second is universities’ increasing reliance on market-based sources of income for revenue and growth. Third is the commodification of key activities and constituents: of students, as a key source of revenue; of research, in the form of industry and corporate funding of research and commercialization of outputs in the form of patents and spin-out companies; and of labour, in the form of Taylorization, intensification and casualization of work for both academics and professional staff (Canaan and Shumar, 2008; Connell, 2016, Kezar et. al, 2019; Shore and Davidson, 2014).

Thus, the neoliberal university draws its inspiration from the governance and managerial practices of the private sector (Shore and Davidson, 2014; Ross, Savage and Watson, 2020). This includes university governance board positions dominated by corporate executives and pay packages for senior leadership and executives that benchmark, and are justified by, private sector compensation norms and practices. A growing proportion of university expenditures are allocated to non-teaching and research activities, such as expanded marketing and legal departments (Giroux, 2009; Ross et al., 2020).

However, the management of higher education is, to use Edwards’ (1979) term, a “contested terrain.” Labour process theory has been used to analyze the ways in which both academic and professional work within the neoliberal university have been fragmented and deskilled and worker autonomy weakened (Ross and Savage 2021). Less attention has been paid to the different manifestations of worker responses in this setting, particularly individual responses and negotiation (Weststar 2012), which would likely range through what Thompson and Newsome describe as “a continuum of possible situationally driven and overlapping worker responses—from resistance to accommodation, compliance, and consent” (2004: 135). Especially salient in the neoliberal academy are forms of collective resistance through unionization.

Institutions that affect trade union rights or coordinated bargaining play an important role in shaping how workers confront insecurity (O’Brady, 2021; Esser and Olsen, 2012) and weather the effects of crises (Glassner 2013). Unions are increasingly concerning themselves with issues of financial control (Hyman and Gumbrell-McCormick, 2017), and how they might influence how management seeks to control or deal with labour (Chai and Scully, 2019; Bamber et al 2022). A growing body of literature connects management practices and decision-making to factors of finance and governance. For instance, Gospel and Pendleton (2003: 558) argue that “managers find ways of enhancing their degree of strategic choice vis-à-vis finance.” In general, under neoliberalism, financial imperatives cascade to lower levels of the firm, and the greater preoccupation with firm-level financial metrics means strategic decisions are made with “little appreciation of their full consequences for lower reaches of the firm” (Gospel and Pendleton, 2003: 567).

2. Method

This study is part of a broader project involving 28 researchers employed across 14 universities (seven each in Canada and Australia). Four of the Canadian universities were in Ontario and the remaining three from the Prairie Provinces. The Australian universities were spread across four states: Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and Western Australia. Three universities in each country were research-intensive (G15 or Go8), and four were not. The study involved a mixed-method research design where both quantitative and qualitative primary data were collected via two online surveys and supplemented by secondary research, documentary analysis and key informant interviews. These sources of data allowed us to analyze the response to the pandemic and the resulting conflict over financial control at the macro- (sector), meso- (university) and micro-levels (individual staff).

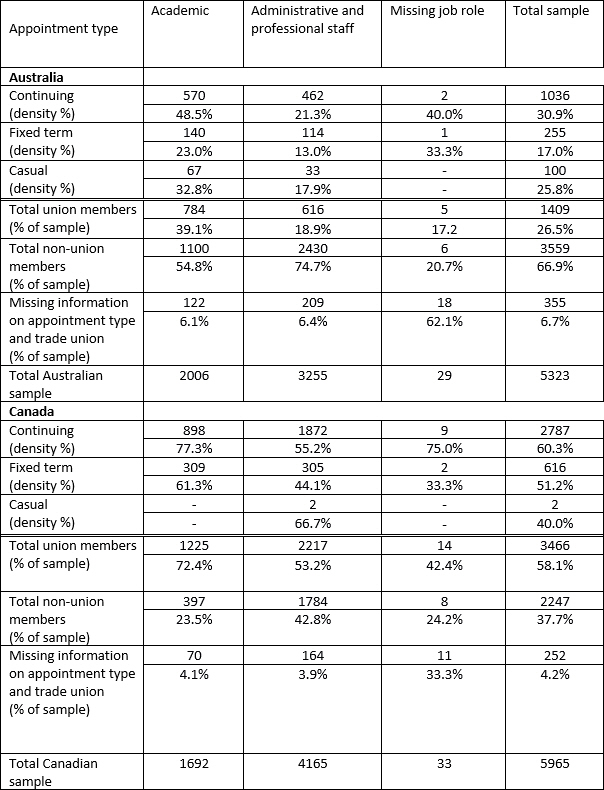

The first survey was administered between June and October 2020 at all 14 universities. In Canada, the first wave of the pandemic ebbed in June 2020, and the second wave rose in September 2020. Australia experienced its second wave from May to October 2020, although that wave was largely localized in the state of Victoria. Responses were gathered from 11,180 university workers. The sample included 3698 academic staff (tenured, tenure-track and contract) and 7420 administrative or professional staff, while 62 respondents did not supply job role information (see Table 1). We excluded 108 senior managers from the analysis in this paper to focus on the experiences of non-managerial staff. Observations per university ranged from 173 to 1825, with a median of 696. Some 58.1% of Canadian respondents reported they were union members, compared to 26.5% of Australians (see Table 2). Across both countries, we found lower unionization among administrative than among academic staff and lower rates among non-tenured/non-permanent workers overall. This figure is slightly lower than expected for the Canadian sample, even with it being dominated by non-academic staff. It is possible that the wording of the relevant question confused respondents who were in non-certified faculty associations or who had not yet reached a threshold to attain union status.

The rest of the survey asked questions about changes to work associated with the pandemic. The key variables analyzed for this paper represent the micro-level experiences of individual university staff. They include four questions that asked whether job security, happiness, job satisfaction and stress had “increased, decreased or remained the same because of the changes associated with moving from pre-COVID to COVID working arrangements.” Our survey also had open-ended questions: “What was the most positive [and then, negative] thing for you about working during the COVID-19 pandemic?” and “Is there anything else you would like to say about your experiences during COVID-19?” The answers to those questions were analyzed for a separate project (Peetz, Baird, Banerjee, Bartkiw, Campbell, Charlesworth et al., 2022) and generally informed our present analysis.

Table 1

Characteristics of the Sample: Job Role and Appointment Type, by Country

Table 2

Union Membership of Sample by Job Role and Appointment Type, by Country

A second survey captured university-level data about the response of each university in the study to the perceived pandemic crisis. It was sent to the 28 researchers involved in the larger project in January 2021 and collected university-level data on matters such as job losses, the process of any restructuring, the forms of adjustment and the involvement of campus unions. As members of the community, these researchers had information about events and interactions in their own universities. Respondents indicated their degree of confidence in their answers. In universities with multiple researchers (most), the response from the researcher demonstrating the greater degree of confidence was retained. Conflicting answers with similar confidence were settled through email consultation to produce consensus. For further verification, the data for each university were circulated to all researchers, and, where appropriate, changes were made.

In our analysis, we categorized the universities in our sample in terms of two factors. The first was whether there was any widespread expectation of job loss among academic or administrative/professional staff at the time the first (university staff) survey was administered. Job losses were typically associated with some restructuring of the university by senior management. Universities at which our informants either reported no “compulsory retrenchments” or “voluntary redundancies” or reported that “There was no widespread expectation of job losses at the time of the survey” were labeled Type I. All of the Canadian universities in our study fit this type.

Second, universities that experienced restructuring were categorized according to the involvement of unions in the restructuring: whether there was high union involvement (Type II, in which our informants said “Major aspects of restructuring were negotiated with unions”; one Australian university); medium-to-low union involvement (Type III, in which our informants said: “Only some aspects of restructuring were negotiated” or “There was consultation with unions but no negotiation”; a majority of the Australian universities); or no union involvement (Type IV, in which our informants said: “All aspects of restructuring were unilaterally decided by management”; one Australian university.)

We called these two factors “loci of restructuring,” and they are used in Tables 3 and 4. During collection of the first survey data, job losses among academic and administrative staff were initially expected or experienced by six of the seven Australian universities but by none of the Canadian universities in our sample (a phenomenon also reflected in labour force data).[1] Therefore, the union involvement factor was relevant only to distinguishing between the Australian universities.

The third source of data consisted of the following: secondary data analysis, including third-party reports and news (obtained through online key word searches); data obtained from relevant labour federations (e.g., polls of member unions and negotiated letters of understanding); opinions and accounts of key union and labour federation informants at the local, regional and national levels (obtained by email or informal telephone conversation); and university-specific communications obtained by the located researchers through participation in departmental, faculty, university and union meetings and as recipients of management and union communications. We used the data to track key institutional developments at the sampled universities and across the sector in each country to capture cross- and intra-national variations important to industrial relations. These sources were particularly relevant for the next section, on higher-level positioning.

3. Higher-Level Positioning: the COVID Crisis and University Responses

Both Australia and Canada are geographically large countries with limited domestic student markets. The university sectors have been shaped by public policy decisions at both national and subnational layers of the state and, although most universities in both countries are public, the sectors have distinctly neoliberal forms.

There remain, however, important differences—the biggest one being in funding. Thus, Australian universities have had greater exposure to financial pressures for job losses. Management might have also been more inclined to implement them, as senior managers there appear to gain more of the financial surplus of universities: Australian vice-chancellors’ pay is amongst the highest in the world—even higher than in the USA or the UK—and seemingly twice that in Canada (Boden and Rowlands, 2020; Kniest, 2017). Yet academic salaries in the two countries seem broadly comparable, with one 2008 analysis suggesting lower-level salaries (lecturer/assistant lecturer) were 10% less in Canada, while professorial salaries were only 2% higher in Australia, both being lower than in the USA (Deloitte 2008:1). Over the last two decades, Australian universities have displayed increasing managerial discretion and growing similarity to private corporations (Pelizzon, Young and Joannes-Boyau 2020). Vice-chancellors have been recast as CEOs who answer to university councils that are akin to corporate boards overseeing large enterprises (Rea 2016).

The countries also differ in their institutional support for unionism and in their macro-economic settings. Union density is higher in Canada (27%) than in Australia (14%) across the general workforce, and also in education (68% vs 38%) (Galarneau and Sohn 2014; ABS 2014). The Canadian Wagner model provides considerable union security within organizations once certification has been achieved (Heery 2002), whereas Australia follows a voluntary membership model in which non-union members can free-ride on union-led enterprise agreements, the major regulatory mechanism for improving wages. (Management can also secure proposed non-union deals with staff via a ballot.)

Across Canada, international students made up 15.7% of enrolments in 2018-19 (Usher, 2020, p.19), and paid two or three times the rate of a domestic student. Nonetheless, Canadian institutions, overall, did not respond to the pandemic with the dramatic austerity measures taken by university administrations in Australia (Whitford, 2020). Timing was a contributory factor: the shift to remote teaching and campus shutdowns occurred in mid-March 2020 and in Canada the term ended in April; by then tuition had already been paid. Universities had time to prepare over the summer for the fall term and assess the pandemic’s effects and longevity. In April 2020, the Trudeau government announced a $9 billion Canada Emergency Student Benefit package (Aiello, 2020). It also lifted restrictions on the number of hours international students could work in “frontline” jobs. Following closure in mid-March, the border was reopened to international students and their immediate families in October 2020 (El-Assal and Thevenot, 2020). While the federal government would not allow universities to access the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy available to private sector employers, universities were eligible for a special research relief fund to help retain staff and resources. Furloughed or laid-off workers were entitled to a new emergency form of employment insurance. Provincial governments also (unevenly) provided some support.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic had a much smaller health effect in Australia than in Canada (the number of Australian deaths in 2020 was barely one-tenth of those in Canada), the financial impact on universities was much worse. Reliance on income from full-fee-paying international students seems to have been more longstanding and more entrenched in Australia than in Canada (Marginson 2010; Horne 2020). Although Australian universities varied in how reliant they were on international students (Parliamentary Library 2019), the proportion of university revenue from international student fees grew from 6% in 1995 to 24% in 2018 (Horne 2020). In 2016, just 37.8% of spending on tertiary education was publicly funded in Australia compared to 49.1% in Canada (OECD 2020).

In March 2020, Australia closed its borders to non-residents. International students were urged to return to their country of origin (Ross 2020). Strict border restrictions continued throughout 2020 and were expected to last well into 2021. International student arrivals fell from 143,810 in the year to July 2019 to just 40 in 2020 (Derwin 2020). With a rapid shift to online teaching, universities continued to receive fees from previously-enrolled international students. However, universities were estimated to lose around $3-4.6 billion in revenue from international students in 2020 alone (Horne 2020). Public universities were ineligible for wage subsidy measures made available to other employers. The federal government’s limited financial support for universities (Markey 2020) reflected what was seen as an ideological “culture war” against “progressive” public universities and a preference for neoliberal policies (Moodie 2020). Despite their neoliberal turn, Australian universities were not neoliberal enough.

The response to this culture war at a time of financial crisis was dramatic and a radical departure from past practice. The National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) is the dominant union representing academics at all Australian universities, and administrative/professional staff in many. A once-centralized national system of wage-setting shifted in the early 1990s to an enterprise-based model of collective bargaining (Bray and Rasmussen 2018) that came to permeate the sector. During the crisis, there was a failed attempt at sectoral bargaining. Foreseeing pressures for cost reduction, the NTEU chose to pre-empt local discussions by negotiating a national Jobs Protection Framework (JPF) with vice-chancellors from the Australian Higher Education Industry Association (AHEIA) (Napier-Raman 2020). This was something neither imaginable nor necessary in Canada, where there had been no prior experience of sectoral bargaining and a less severe perception of crisis. Implicitly recognizing that “academic work as a whole” experienced precarity (Newson and Polster 2021), even more so during this crisis, the JPF aimed to protect casual workers who had a reasonable expectation of ongoing work and minimize involuntary stand-downs of university employees. Crucially, it also allowed for temporary pay cuts and deferred salary increases through bargained variations in collective agreements in return for key guarantees, including scrutiny of university finances (Markey 2020). This trade-off provoked revolts from some union members. Meanwhile university managers resisted the loss of financial control, regardless of any possible savings. In any event, the majority of universities refused to sign up to the framework (Napier-Raman 2020), and fissures remained between many NTEU members, individual university union branches and NTEU federal officials.

The battle over the JPF was an instance of the union recognizing that decision-making over retrenchments and wages was integrally related to control over budgetary and financial decision-making. The union wanted to see the books; the universities’ industry body agreed, but many (not all) individual universities balked. They were so resistant that some preferred to forgo the ability to make labour cost savings (some attempts to achieve cuts in conditions were defeated by union campaigns) rather than hand over financial information. Retaining exclusive financial control became more important than the surplus itself. In the universities we investigated, the depth of the crisis did not, overall, seem to influence either management’s decision to engage with unions or the extent to which they did engage. In some circumstances, unions recognized that financial control over resource allocation was so important for wages and retrenchments that they needed to at least know what was going on there.

In Canada, some institutions attempted significant cost savings early in the pandemic. However, there were considerable institutional and regional differences. For example, a few schools in Maritime (eastern) Canada (not represented in our other data) quickly announced that they would be cutting contract staff positions, reducing operational expenditures and instituting wage freezes and rollbacks for non-union faculty and staff (Devet, 2020; Journal Pioneer, 2020). Many of these measures were ultimately resisted or tempered, particularly when student enrolments did not decrease. Elsewhere in Canada job losses were rarer, with management working with unions and employee groups to redeploy workers or reinvent new work (e.g., pandemic-related health and safety work).

In the early days of the pandemic, most Canadian university administrations imposed restrictions on work-related travel, and some instituted hiring freezes. Campuses were closed in response to provincial directives, and both academic and administrative staff were told to work from home. Teaching moved online. Although, in the view of one national union federation staff member, most “employers ended up being sensible,” many shared governance structures were bypassed. Major decisions were channeled through newly created crisis response teams without union representation that functioned as parallel administrative decision-making bodies outside governance structures. The Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) reported that two-thirds of Joint Occupational Health and Safety Committees met, yet with no real role. Labour-management joint bodies were involved in some decisions, in some disciplinary units and in some institutions, but typically not in a proactive way. The policing of shared governance and the terms of collective agreements relied heavily on the vigilance of members. Unions seemed to have greater leverage if they were in bargaining during the pandemic.

By September 2020, many Canadian universities saw increased domestic enrolments, and some maintained pre-pandemic international numbers (Friesen, 2020). Early dire enrolment predictions did not materialize. Some negotiation occurred between university administrations and unions on lesser financial control issues or administrative matters (such as disrupted sabbaticals, redeployment and wage subsidy top-ups). Overall, industry analysts predicted that negative effects would be felt by the most vulnerable, including non-unionized workers, contract academic staff and non-academic staff (Bodin, 2000; CUPE, 2020). However, the need for austerity did not manifest, and layoffs were mostly seen among staff performing “in-person service” jobs (hospitality, grounds work, etc.). Some campus unions even reported increases in demand for contract faculty.

Australian universities shifted to a model of remote learning from mid-March 2020, early in the academic year. Some institutions allowed staff to use university facilities to undertake their teaching delivery; others mandated that all staff work from home. Most state governments imposed temporary requirements affecting lecture hall capacity. The bigger variation was in the extent of COVID-related job losses, which ranged from nonexistent to severe. Contracts for many professional and academic staff were not renewed, and casual staff numbers and hours were slashed. NTEU branch action to ameliorate the worst impact of these changes varied across universities. Australian universities shed at least 17,300 jobs (about 13%) in 2020, going well beyond “in-person service” jobs. Casuals were the hardest hit. Universities lost an estimated $1.8 billion in revenue (5%) compared to 2019 (Jackson, 2021; Zhou 2020). Other job loss estimates are higher (Littleton and Stanford, 2021). After abandoning the JPF, many individual Australian universities sought to negotiate cuts directly with staff—some successfully, some unsuccessfully—or to unilaterally force layoffs.

In both Canada and Australia, major shifts in production processes involved working from home (Pennington and Stanford 2020). These shifts signified loss of control for some (especially faculty), but for others (especially administrative/professional staff) there were enhanced opportunities for autonomy. Management lost some power, despite technology-based monitoring capabilities. The different macro environments, though, were what initially shaped the different responses by individual universities.

4. Micro-Level Patterns: How University Staff Were Affected

Working life at this time was a contradictory experience for many staff. Working from home (WFH) during COVID-19 was a liberating and a novel experience for administrative staff. Though not without problems, employees could choose when they worked and avoided the grind of daily travel, something the data from the open-ended survey questions showed was valuable. While the location of work was different, for many the computer-mediated labour process itself was fundamentally similar. When asked in our survey to rate their first thought that came to mind about working arrangements, 57% of administrative/professional staff gave a positive rating, while just 26% gave a negative rating. For academics, the experience was very different: most had to adapt to online teaching, something outside their control, and low levels of experience with online teaching were strongly linked to negative views of working from home (Foster, Samani, Campbell and Walsworth, 2022). Overall, only 31% of academics gave WFH arrangements a positive rating, while 50% gave them a negative rating. In Canada, where previous experience with online teaching was much lower, 24% gave a positive rating, compared to 37% in Australia. Most staff were satisfied with the physical aspects of WFH but reported problems with work-life interference, rising workload, rising stress, increased weariness and diminished interactions with other people.

The impact of restructuring was revealed when many university staff reported feelings of decreased job security (44% reported it had decreased “a little” or “a lot,” while just 6% reported it had increased) and a deterioration in career prospects. Both outcomes were significantly worse in Australia. Perceptions of decreased employment security were associated with perceptions of rising workload, poorer organizational support for WFH, problems with technology and respondents’ fear they were not meeting the organization’s expectations. Such perceptions were also related to reduced job satisfaction, increased stress and more negative overall associations with the move to WFH.

Table 3 shows how staff perceptions of changes in job security were tied to the two loci of restructuring. These two loci aligned with the four university ‘types’ mentioned earlier. As would be expected, substantial majorities of both academic and administrative/professional staff perceived declining job security where job losses were expected but saw stable job security where job losses were not expected. Anticipated job losses prompted the potential labour-management conflict over finance that saw varying degrees of union involvement in decisions about university restructuring. Amongst those universities where job losses were expected, perceptions of declining job security were strongest where union involvement was low, and weakest where union involvement was high. This effect was stronger amongst administrative/professional staff than amongst academics.

Table 3

Staff Perceptions of Changes in Job Security, by Loci of Restructuring

N represents the number of those who answered the question. Total Ns do not sum to the total number of respondents in the survey because of missing information.

Changes were associated with an overall rise in unhappiness amongst academic staff, while views were evenly split amongst administrative/professional staff. As Table 4 shows, the rise in unhappiness was greater in Canada, where job losses were not expected but other factors (such as online inexperience) prevailed. But in universities where restructuring and job losses did occur, the rise in unhappiness was greatest where management unilaterally made decisions, again especially amongst academics. Unhappiness rose the most where the conflict over financial control was resolved without input from unions, and the least where employees were able to maintain some control through the high involvement of their union. Although we did not measure trust in the survey, the qualitative comments implied its importance, with, for example, one respondent from a Type II university referring to how the vice-chancellor’s “openness and inclusiveness also engendered trust” while one from a Type III university said: “What trust I felt in my relationship with my employer…has diminished.”

Table 4

Staff Perceptions of Change in Happiness about Work, by Loci of Restructuring

N represents the number of those who answered the question. Total Ns do not sum to the total number of respondents in the survey because of missing information.

Expectations of job losses made little difference to changes in job satisfaction arising from WFH arrangements. However, decline in job satisfaction was still stronger, especially amongst academics, where there was no union involvement in restructuring (where 60% reported a decline) compared to partial (50%) or major union (49%) involvement.

Similarly, there was little difference between reported changes in stress in universities without job losses (81%) compared to those with job losses (77%). Again, especially amongst academics (for whom autonomy and presumably control were especially important), stress in situations of expected job losses was higher in universities where management unilateralism determined restructuring (83%), and lower where unions were involved either partially (78%) or in a major way (75%). These patterns of happiness, stress and job satisfaction suggest that the affective response of university staff was most positive where they still had some indirect financial control, and most adverse where they had none.

Our data suggest that respondents’ answers were influenced by factors other than the COVID-19 work arrangements themselves. Universities’ approaches to job protection, restructuring and engagement with staff through unions appeared to influence the way staff perceived the effects of the COVID-19 working arrangements. Responses to open-ended questions told us more about views on the conflict over finance. For instance, while some respondents from a Type II university referred to how the “university's communication has been really good,” some from a Type III university saw management as demonstrating a “rejection of transparency,” being “increasingly top-down” and lacking “even consultation.” Some from a Type IV university referred to management’s “refusal to use [a] war chest,” the “very distressing” change process or it being a “dog-eat-dog world.” Still, financial control issues were not frequent in the open-ended comments, a fact perhaps reflecting not just priming by other survey questions but also the lesser overt importance attached to financial control by employees than by their negotiators, who saw it as critical to job security.

Discussion

At the macro level, a crisis is determined by the circumstances of accumulation (influenced in this case by the pandemic) and the institutional and policy framework. The extent of a crisis in turn determines managerial choices, such as the size of threatened or actual job losses within universities themselves. Conflicts over financial control may be only exposed by a crisis, and otherwise be covert or latent. Where there is a major threat of job losses, there are variations in management control strategies and worker resistance (influenced by the choices and relative strength of management and labour), but the dialectic of control and resistance can extend beyond the struggle at the point of production (the focus of second wave labour process research: Thompson and Newsome, 2004) and toward conflict over financial control of resource allocation. The outcomes of this conflict may influence not only the actuality of job losses and perceptions of job insecurity by employees but also various affective outcomes amongst employees, such as stress, job satisfaction and happiness, since employees’ perceptions of control will shape affective outcomes (Van der Hoef and Maes, 1999). Overall, and despite the benefits for some staff of working from home (least of all for Canadian academics, more stretched by the new online teaching regime), the pandemic saw increases in insecurity, stress and unhappiness amongst staff, especially academics, and especially in Australia, where the combination of job loss and the sidelining of unions was more common.

Battles over control feature in two ways in our analysis: in the disputes over the Job Protection Framework, including disputes at individual universities; and in the way that different forms of control (joint or unilateral) and outcomes of control (job losses or otherwise) were linked to different outcomes amongst employees. In the former, battles over financial control of resource allocation were important in shaping the form and extent of job losses. In the latter, the outcomes of those battles in turn influenced the outcomes of threatened job losses for employees.

Most (but not all) Canadian universities avoided the deep financial impacts faced by Australian universities and had more favourable industrial relations legislation that enabled unions to stave off severe restructuring decisions. Structural factors at the macro-level matter. In that context, the nature of crises itself, in this case embedded in a marketized project to accumulate capital through international enrolment, had a significant impact on workers’ structural power to negotiate adaptations to crises. Union involvement in restructuring negotiations played a critical role in Australia, where universities were most vulnerable to enrolment shocks, and were indicative of successful contestation to preserve workers’ job security. Some Australian universities shared control with unions by negotiating benefit cuts; others refused to cede control, providing limited information to employees and representatives and either negotiating a limited range of matters or consulting without negotiation.

The neoliberal university is a project-in-the-making. It is both a product of the wider ideational and macro political economic environment in which it operates and a product of the acts of control and resistance by its constituents. When we think of the labour process as one in which there is a battle for control, we must remember it is a battle not just over how work is done and rewarded but also for control over the use of all resources—not only labour—in the organization. Meanwhile, unions and their memberships can have differing priorities: the national union leadership in Australia saw the importance of financial control, but many members focused on the importance of pay rates and job security and saw concessionary union strategy in the Job Protection Framework as securing neither (Vassiley and Russell 2021). They were particularly unwilling to compromise on pay, so they did not mourn the collapse of the national agreement. The lack of union and worker consensus on priorities such as pay and job security will likely constrain the extent to which financial control will be challenged in the future, at least in the Australian context.

Our findings extend the literature that documents the ways in which neoliberalization processes are routinely contested by university staff in a variety of individual and collective actions (Kezar et. al, 2019, Mountz et. al, 2015, Ross et. al. 2020, Shore and Davidson, 2014), particularly in times of crisis. Indeed, the crisis in how, and where, work happens under COVID-19 provides a natural experiment to build on and extend the literature that interrogates how both management and workforces—individually and collectively—respond to dramatic changes in the external environment (see also Ross and Savage 2021).

Importantly, while the labour process debate focuses on the control of labour (Braverman, 1974; Edwards, 1979), developments here show that issues of control may extend beyond labour itself to control over finance, that is, over resource allocation. Particularly if a crisis arises, new dialectics might emerge over financial control, thus providing unions with opportunities to act on behalf of their members. But the parties may prioritize different aspects of financial control. Even in a crisis, management might not be willing to forego absolute control over finance and share that control with representatives of labour, even where such sharing might improve outcomes for the organization in the longer term. In some (but not all) circumstances, management prioritizes financial control, and indeed the opacity of financial control, above the surplus itself. This urge for financial control by management appears to be detrimental to employees, particularly their perceptions of job security but also their levels of stress, job satisfaction and happiness. Detrimental outcomes are especially likely where management seeks to act unilaterally.

When people think of the labour process as being about control, it is necessary to recognize that the urge for control by management over labour often extends to strong resistance by management to oversight of financial control by labour. It is for good reason that management resists not just industrial democracy but also economic democracy within the organization.

Our mapping of major neoliberal restructuring in universities during the COVID-19 crisis provides a solid base on which to understand the changes that universities are undergoing, while setting the stage for future research aimed at exploring how these dynamics shape strategies of resistance to neoliberal work reorganization and intensification.

Parties annexes

Note

-

[1]

Labour Force Survey Data for Canada show that unemployment levels for the “university professors and lecturers” category remained stable at 7-8% for the May-September period across 2019, 2020 and 2021. Direct consultation with campus unions associated with our sample in April 2022 confirmed very limited job loss due to the pandemic in June-September 2020 among academic staff or administrative/professional staff. One campus union did report a 35% decrease in membership among one group of contract faculty members, which was offset by an increase in another (i.e., reduction in evening courses offset by an increase in day courses). Layoffs among university staff were largely experienced by workers in trades, facilities and groundskeeping, and hospitality while campuses were closed. These workers were not included in our sample.

References

- ABS. 2014. ‘Employee Earnings, Benefits and Trade Union Membership, Australia.’ Cat. No. 6310.0. Canberra, Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- Aiello, Rachel. 2020. ‘PM Trudeau announced $9B in below COVID-19 funding for students.’ CTV News (April 22). https://www.ctvnews.ca/canada/pm-trudeau-announces-9b-in-new-covid-19-funding-for-students-1.4906564

- Baccaro, Lucio and Chris Howell. 2017. Trajectories of Neoliberal Transformation: European Industrial Relations since the 1970s. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Bamber, Greg J., Marjorie A. Jerrard, and Paul F. Clark. "How do trade unions manage themselves? A study of Australian unions’ administrative practices." Journal of Industrial Relations (2022): DOI: 00221856221083715.

- Boden, Rebecca and Julie Rowlands. 2020. Paying the piper: the governance of vice-chancellors’ remuneration in Australian and UK universities. Higher Education Research and Development, DOI:10.1080/07294360.2020.1841741.

- Bodin, Madeline. 2020. ‘University redundancies, furloughs and pay cuts might loom amid the pandemic, survey finds.’ Nature (July 30). https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02265-w

- Braverman, Harry. 1974. Labour and Monopoly Capital: The Degradation of Work in the Twentieth Century. New York and London: Monthly Review Press.

- Bray, Mark and Erling Rasmussen. 2018. Developments in Comparative Employment Relations in Australia and New Zealand: Reflections on ‘Accord and Discord’. Labour & Industry, 28(1): 31-47.

- Chai, Sunyu and Maureen A Scully. 2019. It’s About Distributing Rather than Sharing: Using Labor Process Theory to Probe the “Sharing” Economy. Journal of Business Ethics 159, 943–960.

- Collier, S. J. (2012). Neoliberalism as big Leviathan, or…? A response to Wacquant and Hilgers. Social Anthropology, 20(2), 186-195.

- Connell, Raewyn. (2016). What Are Good Universities? Australian Universities' Review, 58(2), 67-73.

- CUPE. 2020. ‘Sector profile: Post-secondary education.’ Canadian Union of Public Employees. National Sector Council Conference (October). https://cupe.ca/sector-profile-post-secondary-education

- Deloitte. 2008. University Staff Academic Salaries & Remuneration, For the New Zealand Vice Chancellors Committee on behalf of the Tripartite Forum Working Group, https://www.universitiesnz.ac.nz/files/u10/deloitte-report-08.pdf

- Derwin, Jack. 2020. ‘This is how many jobs each Australian university has cut – or plans to – in 2020.’ Business Insider Australia (Sept 18). https://www.businessinsider.com.au/australian-university-job-cuts-losses-tally-2020-9

- Devet, Robert. 2020. ‘Mount Saint Vincent University intends to cut 100 part-time instructor contracts this falls, says post-secondary education coalition.’ The Nova Scotia Advocate (June 8). https://nsadvocate.org/2020/06/08/mount-saint-vincent-university-intends-to-cut-100-part-time-instructor-positions-this-fall-says-post-secondary-education-coalition/

- Dobbins, Tony. 2020. ‘Covid-19 and the Past, Present and Future of Work.’ Futures of Work (May 5). https://futuresofwork.co.uk/2020/05/05/covid-19-and-the-past-present-and-future-of-work/.

- Edwards, R. 1979. Contested Terrain: The Transformation of the Workplace in the Twentieth Century: New York: Basic Books.

- El-Assal, Kareen and Shelby Thevenot. 2020. ‘Students and families allowed to travel to Canada.’ CIC News (October 2). https://www.cicnews.com/2020/10/students-and-families-allowed-to-travel-to-canada-1015971.html#gs.ln7hme.

- Esser, I., and Olsen, K. M. (2012). Perceived job quality: Autonomy and job security within a multi-level framework. European Sociological Review, 28(4), 443-454.

- Foster, Jason, Mojan Naisani Samani, Shelagh Campbell and Scott Walsworth. (2022). ‘Newbies vs. old-timers: University workers’ differential experiences of working from home during COVID-19’. Workplace: A Journal for Academic Labor, 33(2022): 11-21.

- Friesen, Joe. 2020. ‘Enrolment up at Canadian universities, mostly because of part-timers.’ Globe and Mail (November 24). https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-enrolment-up-at-canadian-universities-mostly-because-of-part-timers/

- Galarneau, Diane and Thao Sohn. 2013. ‘Long-term trends in unionization.’ Statistics Canada. Catalogue no. 75-006-X. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/75-006-x/2013001/article/11878-eng.pdf?st=YenvtMSv

- Giroux, Henry. 2002. Neoliberalism, Corporate Culture, and the Promise of Higher Education: The University as a Democratic Public Sphere. Harvard Educational Review, 72(4): 425-464.

- Gospel, Howard and Andrew Pendleton. 2003. Finance, corporate governance and the management of labour: A conceptual and comparative analysis. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 41(3): 557-582.

- Horne, Julia. 2020. ‘How universities came to rely on international students.’ The Conversation (May 22). https://theconversation.com/how-universities-came-to-rely-on-international-students-138796

- Hyman, Richard and Rebecca Gumbrell-McCormick. 2017. Resisting Labour Market Insecurity: Old and New Actors, Rivals or Allies? Journal of Industrial Relations, 59(4): 538-561.

- Jackson, Catriona. 2021. ’17,000 uni jobs lost to COVID-19’. Media release. Universities Australia. 3 February. https://www.universitiesaustralia.edu.au/media-item/17000-uni-jobs-lost-to-covid-19/

- Journal Pioneer. 2020. ‘Cape Breton University looks to cut costs amid global pandemic.’ The Journal Pioneer (June 22). https://www.journalpioneer.com/news/canada/cape-breton-university-looks-to-cut-costs-amid-global-pandemic-465090/

- Kniest, Paul. 2017. Australian Universities Top Rankings…For VC pay. Advocate. 24(1).

- Lin, K. H. and Tomaskovic-Devey, D. 2013. Financialization and US Income Inequality, 1970-2008, American Journal of Sociology, 118(5):1284-1329.

- Littleton, Eliza and Jim Stanford. 2021. An Avoidable Catastrophe: Pandemic Job Losses in Higher Education and Their Consequences. Sydney: Centre for Future Work. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/theausinstitute/pages/3830/attachments/original/1631479548/An_Avoidable_Catastrophe_FINAL.pdf?1631479548

- Markey, Ray. 2020. ‘Pay cuts to keep jobs: The tertiary education union’s deal with universities explained.’ The Conversation (May 18). https://theconversation.com/pay-cuts-to-keep-jobs-the-tertiary-education-unions-deal-with-universities-explained-138623

- Moodie, Gavin. 2020. ‘Why is the Australian government letting universities suffer?’ The Conversation (May 19). https://theconversation.com/why-is-the-australian-government-letting-universities-suffer-138514

- Napier-Raman, K. (2020). Anatomy of a disaster: how the NTEU’s plan to save jobs fell apart. Crikey. June 5. https://www.crikey.com.au/2020/06/05/nteu-disaster-how-a-plan-to-save-jobs-fell-apart/

- Newson, Janice, and Claire Polster. "Restoring the Holistic Practice of Academic Work:: A Strategic Response to Precarity." Workplace: A Journal for Academic Labor 32 (2021).

- O'Brady, S. (2021). Fighting precarious work with institutional power: Union inclusion and its limits across spheres of action. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 59(4), 1084-1107.

- Parliamentary Library. 2019. ‘Overseas students in Australian higher education: A quick guide.’ Research Paper Series, 2018–19. Commonwealth of Australia: Australian Parliamentary Library. https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/library/prspub/6765126/upload_binary/6765126.pdf.

- Peetz, David, Marian Baird, Rupa Banerjee, Tim Bartkiw, Shelagh Campbell, Sara Charlesworth, Amanda Coles, Rae Cooper, Jason Foster, Natalie Galea, Barbara de la Harpe, Catherine Leighton, Bernadette Lynch, Susan Ressia, Carolyn Troup, Scott Walsworth, Shalene Werth, Johanna Weststar. 2022. Sustained knowledge work and thinking time amongst academics: gender and working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Labour and Industry, 32(1), 72-92, https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2022.2034092.

- Pelizzon, Alessandro, Martin Young and Renaud Joannes-Boyau. 2020. ‘”Universities are not corporations”: 600 Australian academics call for change to uni governance structures.’ The Conversation (July 29). https://theconversation.com/universities-are-not-corporations-600-australian-academics-call-for-change-to-uni-governance-structures-143254

- Pennington, Alison and Jim Stanford. 2020. Working from Home: Opportunities and Risks. Sydney: Centre for Future Work. https://www.futurework.org.au/working_from_home_in_a_pandemic_opportunities_and_risks

- Rea, Jeannie. 2016. Critiquing Neoliberalism in Australian Universities. Australian Universities’ Review, 58(2): 9-14.

- Ross, Stephanie, Larry Savage and James Watson. 2020. University Teachers and Resistance in the Neoliberal University. Labor Studies Journal, 45(3): 227-249.

- Ross, Stephanie, and Larry Savage. "Work reorganization in the neoliberal university: A labour process perspective." The Economic and Labour Relations Review 32.4 (2021): 495-512.

- Ross, John. 2020. ‘Time to go home Australian PM tells foreign students.’ Times Higher Education (April 3) https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/time-go-home-australian-pm-tells-foreign-students

- Standing, Guy. 1997. Globalization, Labour Flexibility and Insecurity: The Era of Market Regulation. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 3(1): 7-37.

- Streeck, Wolfgang. 2014. How Will Capitalism End? New Left Review, (87): 35-64.

- Susskind, Daniel and David Vines. 2020. The Economics of the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Assessment. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 36(Supplement_1): S1-S13.

- Thompson Paul and Newsome Kirsty. 2004. ‘Labour Process Theory, Work and the Employment Relation.’ In: Theoretical Perspectives on Work and the Employment Relationship, edited by Bruce Kaufman, pp 133-162. Cornell: Cornell University Press.

- Usher, Alex. 2020. The state of postsecondary education in Canada. Higher Education Strategy Associates. https://higheredstrategy.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/HESA-SPEC-2020-revised.pdf

- Van der Doef, Margot and Stan Maes. 1999. The Job Demand-Control (-Support) Model and Psychological Well-being: A Review of 20 Years of Empirical Research. Work & Stress, 13 (2): 87-114.

- Vassiley, Alexis, and Francis Russell. "Concession-bargaining in Australian higher education: the case of the National Jobs Protection Framework." Labour & Industry: a journal of the social and economic relations of work 31.4 (2021): 439-456.

- Vidal Matt and Marco Hauptmeier. 2014. ‘Comparative Political Economy and Labour Process Theory: Toward a Synthesis.’ In: Comparative Political Economy of Work, edited by Marco Hauptmeier and Matt Vidal, pp. 1-32. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Weststar, Johanna. "Negotiating in silence: Experiences with parental leave in academia." Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations 67.3 (2012): 352-374.

- Whitford, Emma. 2020. ‘Here come the furloughs.’ Inside Higher Ed (April 10). https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/04/10/colleges-announce-furloughs-and-layoffs-financial-challenges-mount

- Zhou, Naaman. 2020. ‘Almost 10% of Australian University Jobs Slashed During Covid, With Casuals Hit Hardest.’ The Guardian (October 7). https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/oct/07/almost-10-of-australian-university-jobs-slashed-during-covid-with-casuals-hit-hardest

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Characteristics of the Sample: Job Role and Appointment Type, by Country

Table 2

Union Membership of Sample by Job Role and Appointment Type, by Country

Table 3

Staff Perceptions of Changes in Job Security, by Loci of Restructuring

Table 4

Staff Perceptions of Change in Happiness about Work, by Loci of Restructuring

10.7202/1012535ar

10.7202/1012535ar