Résumés

Abstract

Multinational corporations are undeniably the driving force of globalization and regional economic integration. A convenient institutional framework (Hall and Soskice, 2001) to apply when comparing multinationals from different host countries is the well-travelled road of dividing capitalist economies into coordinated market economies (CMEs) and liberal market economies (LMEs). This article aims to elucidate the tensions between centralized human resources practices and labour union avoidance usually exhibited by multinationals from so-called Liberal Market Economies (LMEs) when they expand into coordinated ones (CMEs). Specifically, it examines the recent acquisition of the German retail giant Galeria Kaufhof by the Canadian multinational Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC).

The article shows that HBC has settled into an uneasy acceptance of the CME institutions, while its investment motives vacillate between a long-term, market-enlargement strategy and a short- to medium-term one, based on the rapidly increasing real estate value of its downtown flagship stores. The article encourages researchers in IR to retain three principal conclusions for the literature and for further study. First, without predetermining outcomes by looking at host-country or home-country effects alone, institutionalist frameworks do present a convenient backdrop for conceptualizing movements of multinationals across jurisdictions. Secondly, concepts such as bricolage, recombining of institutional elements and institutional entrepreneurship, stemming from the institutional change literature, should routinely figure in one’s analytical toolbox, in any attempt at non-deterministic institutional analysis. Finally, sector-level actors, such as trade unions and employers’ associations, can play an essential role in any successful adaptation of collective bargaining institutions in the context of globalization by developing, maintaining and carefully utilizing their repertoire of strategic capabilities.

Keywords:

- multinationals,

- trade unions,

- employers’ associations,

- institutionalism,

- strategic capabilities

Résumé

Les entreprises multinationales sont indéniablement le moteur de la mondialisation et de l’intégration économique régionale. Un cadre théorique institutionnel (Hall et Soskice, 2001) à appliquer lors de la comparaison de multinationales de différents pays hôtes s’avère être la division bien connue des économies capitalistes, à savoir les économies de marché coordonnées et les économies de marché libérales. Cet article vise à élucider les tensions qui se créent entre les pratiques centralisées en matière de gestion des ressources humaines et la recherche de l’évitement de la présence syndicale habituellement affichées par les multinationales d’économies de marché libérales (EML) lorsque ces dernières se développent dans des économies de marché coordonnées (EMC). Plus précisément, il examine l’acquisition récente du géant allemand du commerce de détail Galeria Kaufhof par une multinationale canadienne, la Compagnie de la Baie d’Hudson (CBH).

L’article montre que la CBH est parvenue à accepter avec réticence les institutions des EMC alors que ses motivations en matière d’investissement oscillaient entre une stratégie à long terme d’élargissement de ses parts de marché et une stratégie à court et à moyen termes fondée sur la croissance rapide de la valeur immobilière de ses magasins-phares du centre-ville. L’article encourage les chercheurs en relations industrielles (RI) à retenir trois conclusions principales du point de vue de la littérature qui pourront servir dans des études ultérieures. Premièrement, sans préjuger des résultats et en examinant uniquement les effets sur le pays hôte ou le pays d’origine, les cadres institutionnalistes constituent une toile de fond utile permettant de conceptualiser les mouvements de multinationales d’un pays à l’autre. Deuxièmement, des concepts tels que le ‘bricolage’, la ‘recombinaison d’éléments institutionnels’ et ‘l’entrepreneuriat institutionnel’, tous issus de la littérature sur le changement institutionnel, devraient systématiquement figurer dans la boîte à outils de l’analyste, notamment dans toute tentative d’analyse institutionnelle non déterministe. Enfin, les acteurs sectoriels, tels que les syndicats et les associations d’employeurs, peuvent jouer un rôle essentiel dans toute adaptation réussie des institutions liées à la négociation collective en contexte de mondialisation en développant, en maintenant et en utilisant, avec précaution, leur répertoire de capacités stratégiques.

Mots-clés:

- multinationales,

- syndicats,

- associations d’employeurs,

- institutionnalisme,

- capacités stratégiques

Resumen

Las corporaciones multinacionales son indudablemente la fuerza impulsora de la globalización y de la integración económica regional. Un marco institucional pertinente (Hall y Soskice, 2001) para la comparación de multinacionales de diferentes países anfitriones es la división muy conocida de las economías capitalistas entre economías de mercado coordinadas (EMC) y economías de mercado liberales (EML). Este artículo pretende dilucidar las tensiones entre las prácticas centralizadas de recursos humanos y la evitación sindical que suelen exhibir las multinacionales de las denominadas Economías de Mercado Liberales (EML) cuando se desarrollan convirtiéndose en economías coordinadas (EMC). Específicamente, se examina la reciente adquisición del gigante alemán del comercio minorista Galería Kaufhof por la multinacional canadiense Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC).

Este artículo muestra que HBC ha logrado aceptar con reticencia las instituciones de las EMC, mientras que sus motivaciones en materia de inversión oscilaban entre una estrategia a largo plazo de ampliación de su cuota de mercado y una estrategia a corto y mediano plazo basada en el rápido crecimiento del valor inmobiliario de sus tiendas-faros del centro de la ciudad. Este artículo incentiva a los investigadores de relaciones industriales a retener tres conclusiones principales desde el punto de vista de la literatura y que podrían servir para estudios ulteriores. En primer lugar, si no se determinan de antemano los efectos en el país anfitrión o en el país de origen, los marcos institucionales proporcionan un marco conveniente para conceptualizar los movimientos de las multinacionales entre jurisdicciones. En segundo lugar, los conceptos como el bricolaje, la recombinación de elementos institucionales y el emprendimiento institucional, derivados de la bibliografía sobre el cambio institucional, deberían figurar sistemáticamente en la propia caja de herramientas analíticas, en cualquier intento de análisis institucional no determinista. Por último, los actores sectoriales, como los sindicatos y las asociaciones de empresarios, pueden desempeñar un papel esencial en cualquier adaptación satisfactoria de las instituciones de negociación colectiva en el contexto de la globalización mediante el desarrollo, el mantenimiento y la utilización cuidadosa de su repertorio de capacidades estratégicas.

Palabras claves:

- multinacionales,

- sindicatos,

- asociación de empleadores,

- institucionalismo,

- capacidades estratégicas

Corps de l’article

Introduction

This article aims to elucidate the tensions between centralized human resources practices and labour union avoidance usually exhibited by multinationals from so-called Liberal Market Economies (LMEs) when they expand into coordinated ones (CMEs). Specifically, it examines the case of the recent acquisition of the German retail giant Galeria Kaufhof by Canadian multinational Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC). First findings seemed to indicate that, while stemming from a distinctly LME background, HBC initially opted for an engagement strategy vis-à-vis its host country’s coordinated labour market institutions and actors. However, a conflict soon emerged between the distinctly North American business model and rent-seeking behaviour of the parent company, on the one hand, and the management practices and labour relations on the old continent, on the other. Actors within the coordinated labour market regime had to use various institutional levers at their disposal in order to bind the multinational to the coordinated institutions in which it had originally agreed to enlist.

As the article will show, HBC settled into an uneasy acceptance of the CME institutions, while its investment motives vacillate between a long-term, market-enlargement strategy and a short- to medium-term one, based on the rapidly increasing real estate value of its downtown flagship stores. Within this field of tension created by the hybridization of CME and LME practices, as well as home and host-country pressures, a significant sandbox for strategic actors has opened up. CME actors resort to creative institutional entrepreneurship, managing to coordinate their actions across a number of institutional arenas and among themselves and they expend significant social capital in order to preserve or remodel CME institutions in the wake of external pressures.

Multinational companies and labour practices

There is evidence that multinational corporations (MNCs) are the driving force of globalization and regional economic integration. Understanding them provides clues to the future of human resources practices and what role, if any, trade unions will be able to play regarding their capacity to negotiate fair labour conditions and a more equitable apportionment of profit. They also challenge the traditional roles of other coordinated actors at the national and at the sector-level, such as employers’ associations.

A vast and growing body of literature has analyzed the behaviour of multinationals when they set up shop in a host country, be it organically or through mergers and acquisitions. Most studies attempt to disentangle host and home country effects concerning human resource practices and practices implying the involvement or avoidance of trade unions. Classic literature on management strategy towards trade unions would situate companies’ “strategic choices” on a continuum somewhere between active trade union engagement and outright trade union avoidance (Kochan, McKersie and Cappeli, 1984). Inductive reasoning suggests that we should be able to map multinationals’ preferences on such a continuum, while taking both home- and host-country effects into account.

When explaining which strategy is chosen by a given multinational, the article considers four different strands of argument: first, institutional path dependency of the home and host countries, pushing the multinational to adopt certain HR practices in order to conform to the appropriate “business systems” in one place or another; second, motives for foreign direct investment (FDI) as explanatory factors for union engagement or avoidance; third, the concepts of bricolage and institutional entrepreneurship, as home- and host-country effects mix and mingle; finally, the article will elucidate whether strategic trade union capacities are at play when multinationals make their choice between ‘boxing and dancing’ (Huzzard et al., 2004).

Institutionalist approaches

A convenient institutional framework to start from, when contrasting labour practices of multinationals from different home countries, is the well-travelled road of dividing capitalist economies between coordinated market economies (CMEs) and liberal market economies (LMEs), and then using these two typologies to categorize outcomes in labour management practices in different types of host-country settings (Frege et al., 2004). The distinction usually places Anglo-American countries (the US, the UK, Ireland, Canada and Australia) in the LME column, whereas most of continental Europe, particularly the Nordic countries, the Benelux countries and Germany, fall into the former category (Hall and Soskice, 2001).

Literature has shown that multinational companies from LME home countries apply a more standardized, formalized, and centralized set of human resource practices (Edwards and Ferner, 2002). It has also indicated that US MNCs are particularly hostile to collective worker representation and more likely to deploy HRM practices such as direct forms of employee involvement (Meardi et al., 2009b). British firms have equally been shown to retreat from collective bargaining wherever possible (Brown et al., 2009).

The logic at work has often been attributed to the particular “business system” (Whitley, 1999) within which the company has emerged, seeking to reproduce the said system abroad. For instance, the investment activities of Japanese multinationals have been classified as “transplants, hybrids, and branch-plants” depending on the pervasiveness and attractiveness of “system effects” in the host country, as they pertain to the activities of the multinational (Elger and Smith, 2006: 53).

Anglo-American multinationals are thus usually seen as a danger to the coordinated set of labour market institutions in continental Europe (Walsh et al., 1995; Butler, 2006). Voices in the trade union movement often invoke historic clashes with American companies such as Amazon, Walmart or McDonald’s when they think of North American multinationals settling into the continental European labour market. Walmart in particular has been studied as a prime example of an LME company being at odds with consumer preferences (Pioch et al., 2009) and labour practices (Hågnell, 2002) in coordinated market economies.

However, a counter-argument to the tale of the inevitable incompatibility between LME multinationals and CME labour market institutions would stress that host-country effects, effectively binding MNCs into local institutional practices, path dependencies and business systems, are just as pervasive as home-country effects. A careful comparison of similar multinationals across a variety of host countries is thus a promising approach. One such study (Almond et al., 2005) concluded that host-country effects do have an adverse influence on the degree to which human resource practices can be standardized and centralized within a multinational, but that home-country preferences of LME-based multinationals, in terms of union engagement and union avoidance, are usually reproduced worldwide.

Consumers in service-related industries and the retail sector play a key role in increasing the salience of potential public campaigns and boycotts. Among one of the reasons cited why Walmart left Germany is that their business model conflicted with the local preferences of consumers, notably concerning their human resources practices (Liu, 2014). Iconic fights have equally happened with Amazon in Germany and Toys “R” Us in Sweden. By comparison, other LME multinationals like General Motors and Ford seem to have adapted well to the coordinated world of CME labour relations.

A particular resource that German social partners can resort to is the significant value-added of the German training system, whereby companies, including multinationals, benefit from a highly consensual and fairly efficient vocational training system. Integrating state resources for vocational training, social partnership and collective bargaining in one codependent structure binds their beneficiaries to the coordinated labour market institutions and increases a moral obligation to avoid free riding on either side of the bargaining table. Such reliance on coordinated institutions to further “location-specific skill sets” have shown to be important mediating forces, for example in a study of UK multinationals in Denmark (Kristensen and Zeitlin, 2005).

Additionally, coordinated market economy actors seem to require and create superior levels of social capital and trust, based on which they manage to mediate certain conflicts related to multinationals and the adaptation of their business practices to the host context. Social capital has thus been underscored as a key variable in understanding transnational HR management practices and labour relations (Taylor, 2006). The creation and expending of social capital should thus be considered as a supporting factor for an institutionalist analysis.

According to institutionalist literature, therefore, one overarching research question can be developed (Q1): “What countervailing institutional pressures is HBC encountering as it enters the European retail market?” On the one hand, if HBC is confirmed as a typical LME player, one should see a tendency to centralize business and labour practices. On the other, one should be able to show pressures on the multinational in the host country, effectively binding it to the coordinated labour market institutions in the country where it seeks to operate.

Complementarities between investment strategy and labour practices

In a second strand of theoretical arguments around multinationals, it has been suggested that one should distinguish efficiency-seeking foreign direct investment (FDI) from market-driven FDI and resource-seeking FDI (Dunning, 1998; Cleveland et al., 2000). The latter is motivated by achieving value-added through critical raw materials. Often then, labour represents a negligible portion of the overall investment and operating cost. While some deeply conflictual cases have surfaced, for instance the case of Vale-Inco in Canada (Peters, 2010), pressures on labour-management relations seem less important when FDI is motivated by access to natural resources, because most productivity is derived from capital investment and from the resource itself, rather than through labour intensity.

A very different picture evolves when the sought-after resource is precisely the relatively affordable or efficient labour force, protected by a strong union. The literature predicts that such efficiency-seeking FDI will, especially if the product or service is to be exported, or is part of a larger, global value chain, lead to an inevitable clash of HR practices seeking to “benchmark” staff performance and maximize profit margins through cutting labour costs. The roles of strong trade unions and other coordinated labour market actors are then inevitably challenged (Sisson et al., 2003).

The third form of FDI is driven by market access. In this case, rather than supporting competitiveness on the home market by cutting labour costs offshore, the multinational seeks to expand beyond the home market. Its competitors are thus largely subjected to the same institutional pressures and market dynamics, and thus the relative value-added of the FDI is not necessarily increased by picking a fight with the local union (Meardi et al., 2009a). On the face of it, HBC’s expansion beyond the Canadian retail market, by acquiring the chain of Galeria Kaufhof department stores in Germany and Belgium, as well as Saks Fifth Avenue in the United States, seems to be an example of such foreign direct investment. This research project thus studies the various impacts on labour relations of the June 2015 acquisition of Galeria Kaufhof by Hudson’s Bay Company as a case of market-driven FDI.

The overarching research question stemming from this body of literature therefore is (Q2): “To what degree has one particular investment strategy motivated HBC’s expansion into Europe?” As access to natural resources can be excluded by the very nature of this multinational, two contrary outcomes could be expected from this line of questioning. If, as HBC’s official investment strategy suggests, the case of Galeria Kaufhof is a market-seeking investment, establishing the company on the European continent and thereby turning the Canadian multinational into a global player in the retail market, then one should expect labour relations to follow a continental model. Conversely, if efficiency-seeking investment, largely motivated by real-estate speculation and the promise of short- to medium-term gains is considered, then one should expect a much larger tendency to centralize business practices and, hence, difficult labour relations.

Additionally, one should carefully examine if so-called efficiency-seeking FDI motivated by real estate speculation can be considered efficiency seeking at all (or if we should rather consider it to be rent seeking). Mirroring the business case for HBC’s 2009 sale of its Zellers stores in Canada to US multinational Target, the recent takeovers of Saks Fifth Avenue and Galeria Kaufhof seem to largely depend on the sharply rising real estate value of the prime store locations that were acquired. At the same time, however, commercial real estate is only valuable as long as the business it hosts remains profitable and the retail market remains stable. With the ongoing move towards large-surface and online shopping and the growth in low-cost retail competition, the future of the traditional department store business model is uncertain.

Of course, there are several further macro-level explanations stemming from bodies of literature that are not specifically linked to multinationals. The retail sector itself is prone to union weakness, where traditional labour relations institutions are constantly challenged (Dribbusch, 2005). The ever-changing nature of the workforce (seasonal employment and part-time work) as well as online shopping are testing established business models, value chains and profit margins. Consequently, they are placing a potentially large strain on labour relations in the sector, both in liberal and coordinated market economies, in both multinational and purely domestic companies.

A further explanation relates to power resources, i.e. the presence or absence of strong trade unions (Korpi, 2006). Is it the relative strength of the Verdi trade union (and the relative weakness of the Canadian unions in retail) that provides a key explanatory factor for HBC’s behaviour in Europe? If power resources and union strength are low in North America, we should be able to see a tendency towards uniformization and trade union avoidance there. If they are strong in Germany, then Galeria Kaufhof should buck that trend and resist the tendency towards marginalizing trade union representatives and works councils in that country.

However, because these factors apply to both multinationals and domestic companies, we shall treat them as controlling factors rather than research questions in and of themselves. Furthermore, on a macrolevel, a strong trade union presence with impressive institutional resources are nevertheless hallmarks of CMEs, and thus the power resource approach is not completely incompatible with the Varieties of Capitalism framework. Finally, because macro-level analysis of any kind often tends to overlook important actors on the meso- and micro-levels, let us now turn to two sets of actor-centred literature.

Institutional change, bricolage and hybridization

A weakness of macro- or even company-level approaches to industrial relations in multinationals is the often-deterministic logic at play, and the limited place left for genuine “strategic choice” and agency. It also tends to reduce multinationals to homogenous organizations with little room for local management actors to engage in meaningful struggles over strategy towards labour unions. To reconcile the power of institutional analysis with a more actor-centred approach, we shall consider two more bodies of literature: that of institutional change and that of trade union capabilities.

Multinationals represent a tremendous challenge to the traditional LME and CME dichotomy, even after variations concerning home—and host-country effects, as well as efficiency—versus market-seeking FDI are taken into account. Some level of hybridization (Elger and Smith, 2006) should be expected when multinationals enter a different host country. The degree to which such hybridization will take place is subject to the cost-benefit analysis of diffusing practices from the home country made by managers there (Cooke, 2006), but is also subject to strategic choices by local managers in the host country.

How do local actors react to domestic and international challenges to the dominant institutional framework, and how can they turn into “institutional entrepreneurs” (Crouch, 2005)? In particular, this article is interested in the institutional change literature’s concept of ‘bricolage’ (Højgaard Chsristiansen, 2013), that is, the recombination of elements from different institutional environments, or recombining elements from existing, but weakening institutional layers of the host country in order to encapsulate multinational companies in a thick layer of institutional embeddedness.

In the case of HBC and Galeria Kaufhof, the old business model and its coordinated HR approach seem to have run afoul, first and foremost, of the changing nature of work in the retail sector. The fact that Kaufhof’s main German competitor, the Karstadt chain of department stores (owned by a real estate investor from an equally coordinated market economy, Austria), has recently withdrawn from the sector-level collective agreement (GER1, GER6) seems to indicate that the troubled business model is as much to blame for decaying collective bargaining institutions as potential home-country effects stemming from the foreign investor.

However, other coordinated institutions, such as the German dual system of vocational training, social partnership at the company level and sector-level employers’ associations may also receive renewed importance in the face of jointly experienced shocks and slowly eroding traditional collective bargaining institutions, such as the end of general applicability of collective agreements based on high labour union density (Ochel, 2005; Fitzenberger et al., 2011). In addition, new institutional elements have been introduced in the German retail sector. For example, Germany has introduced a generally binding minimum wage (Mabbett, 2016), engagement HR practices at the workplace have become more common, and online retail has been embraced.

An overarching research question flowing from this literature then would be (Q3): “To which degree is hybridization of institutions and practices taking place?” Moreover, if it is, does it stem from active institutional entrepreneurship by company management, employers’ associations and trade unions on a meso- or micro-level, or can it simply be attributed to institutional and macro-level pressures described earlier?

Strategic trade union capacities

Actors’ capacities, both on the trade union side and by employers’ associations, thus seem to be at the heart of mediating potential conflicts when institutional mismatches between multinational companies and host-country institutions in the labour market occur. In addition, multinational companies should not be seen as monolithic organizations, but rather as “shifting coalitions of interest, subject to complex micro-political dynamics” (Ferner, Quintanilla and Sanchez-Runde, 2006: 7), thereby opening up a significant strategic sandbox in which resourceful actors can operate.

Authors such as Dufour and Hege (2009) have examined the capacity for coordination between institutional levels. In the European case, this entails effective means of communicating, negotiating and mediating between the national union and employers’ association, the local management, the company works council and its board of directors, as well as upper management at the MNC’s headquarters.

As this research will show, both the employers’ association, HDE, and the trade union, Verdi, represent such vertically integrated, high-capacity actors, who—while both sticking to their own bailiwick—manage to partially mediate the brewing conflict between the North American-style business and labour practices of HBC and the coordinated world of labour relations in Germany.

Specifically, on the trade union side, strategic capacities also imply mustering and mobilizing resources for game-changing campaigns, also referred to as “discursive capacities” (Levesque and Murray, 2010335). In the case of the German trade unions in the retail sector, Verdi has been particularly effective in publicizing and denouncing practices of employers such as LIDL (a supermarket chain now known for paying ABOVE average wages) and Walmart (forced to retreat from the German market after a concerted campaign against its labour practices and its business model, see Hamann and Giese, 2004; Liu, 2014). Verdi is the main trade union representing workers at Galeria Kaufhof.

One final trade union capacity, often cited in the quest for understanding successful trade union campaigns in modifying MNC behaviour, is transnational cooperation between labour unions representing workers of the same company in different countries (Dufour-Poirier and Hennebert, 2015; Cooke, 2006). Concretely, this should involve a certain level of “borrowed resources” (Martin and Ross, 2001: 53), and the creation of transnational links between trade unions representing workers of Hudson’s Bay Company in Canada, the US and Europe. Or at the very least, one would expect to find an initiative to unite the efforts of Belgian, Dutch and German workers, maybe by resorting to a European works council (Martin and Ross, 1999).

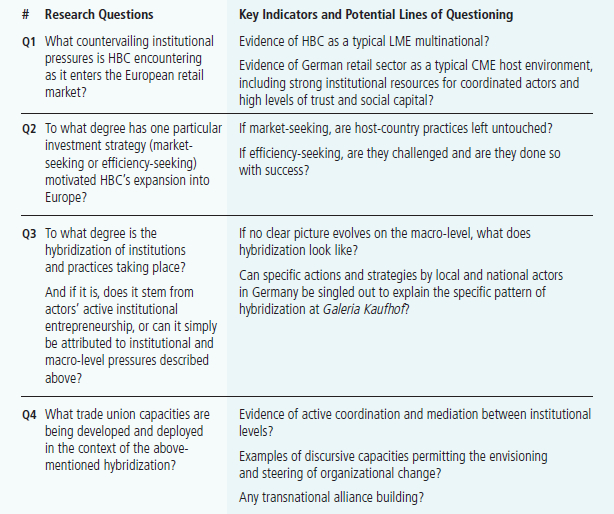

Table 1

Research Questions and Indicators

As the overarching research question related to trade union capacities (Q4) then, we should ask: “What trade union capacities are being developed and deployed in the context of the ongoing hybridization of HR practices at Galeria Kaufhof?” In particular, “Is Verdi resorting to active coordination and mediation between institutional levels, discursive capacities permitting the envisioning and steering of organizational change, and finally transnational alliance building to counteract the overwhelming power resources of HBC as a multinational?”

Methodology and data analysis

This study proceeds as a single-case study, because, while carefully examining and describing HBC’s labour practices and business models in Canada and Kaufhof’s in Germany, separately, the ultimate unit of analysis is a single takeover of one by the other. As suggested by Seawright and Gerring (2008: 299), the study of such a “typical case” is meant to “explore causal mechanisms” suggested by a certain body of literature. “The puzzle of interest to the researcher lies within that case” (ibid.) and may lead to an added layer of richness to several different bodies of literature by providing meaningful interpretation in a given context, but also by developing paths for future studies.

Thus, while HBC’s labour relations are summarily compared between Canada and Germany, the historical development of HR practices in each of the two countries are first be examined in their proper institutional frameworks. Beyond a rich descriptive study of these two retail giants, the specific analytical aim of this study is to then delve into important research questions flowing from the existing literature with regards to the takeover of a CME company by an LME multinational, and apply them to this carefully selected case.

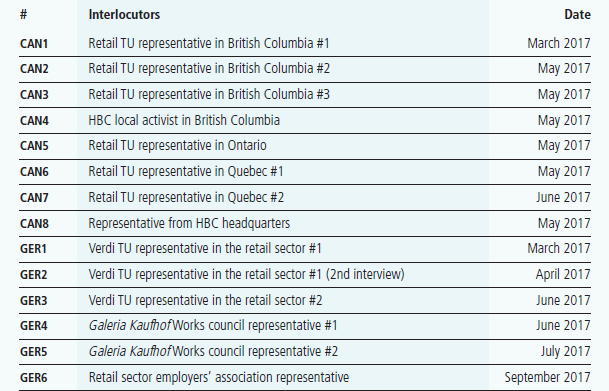

Fourteen interviews (CAN1-8 and GER1-6) were carried out throughout the spring and summer of 2017 in both English and German, with all but one of them taking place over the phone (see Table 2). The semi-structured interviews with an employers’ association representative in Germany (GER6), as well as with trade union representatives within HBC (Interviews CAN1-7) and Galeria Kaufhof (GER3-5) were following a set list of open-ended questions, closely mirroring the indicators and lines of questioning, while still allowing for rich descriptive data of the particular Canadian and German examples involved. Initial interviews of Verdi trade union representatives in the retail sector (GER1-2) were part of a much larger, collaborative interview process concerning labour relations in the German retail sector. It should be noted that HBC’s headquarters in Brampton, beyond a brief telephone conversation confirming some of the publicly available information (CAN8), declined to participate in the study. Following the interview stage, key information was triangulated with experts, news articles and official documents of the actors involved, allowing the reliability of the data to be ensured.

Table 2

Interviews

The article will proceed by presenting each country case separately, firmly establishing HBC in Canada as a typical LME player and Galeria Kaufhof as a hallmark for CME labour relations, before then turning our attention to the effects of the acquisition of Galeria Kaufhof by HBC in 2015. It should be noted that the very recent nature of the transaction necessarily implies that the article is dealing with a somewhat moving target. To exemplify this conundrum: in September 2018, the board of governors of HBC Europe accepted a takeover bid from Signa Holding, owner of Galeria Kaufhof’s main competitor in Germany: Karstadt department stores. The resulting joint venture means that now 49.99% is owned by HBC. As the reader will appreciate, many of the conflicts about business strategy and labour relations are very recent or even ongoing. Precisely for this reason, the article avoids citing interview partners directly.

The Hudson Bay Company – primus inter pares of Canadian retail

Founded in 1670 and being a historical landmark of the retail sector there, Hudson’s Bay Company is the owner of 90 department stores in Canada. It is North America’s oldest company and, at first sight, a typical LME player. With unionization spotty at best, in the context of a general weakening of trade unions in North America, and while also benefiting from generally low wages and deskilling in the retail sector, it has been profitable and has expanded aggressively within Canada, into the US and into Europe, regime shopping whenever possible.

The Canadian labour relations regime closely mirrors the US Wagner Act: union accreditation is awarded on a shop-by-shop basis to a labour organization representing the majority of workers. Card-check accreditation is only available in some jurisdictions, leaving most organizing drives vulnerable to employers’ intimidation tactics in so-called secret ballots. There were also cases of store closures in the retail sector, once a union had been successfully accredited (e.g. Couche-Tard and Walmart, see Laroche et al., 2015). Canadian and American employers in retail thus seem particularly intent on keeping the doors closed to union representation.

The retail sector in Canada is in full upheaval since the arrival of Walmart and the ensuing “retail revolution” as Lichtenstein (2009) phrases it. One of the classic studies of retail sector unionization involved the Eaton unionization drive in 1948 to 1952 (Sufrin, 1983). Many of the distinct challenges for Canadian unions in the retail sector are discussed in great detail in this classic example of a failure of labour organizations to gain a solid foothold in department stores. Many of the challenges reported in the 1950s persist in the Canadian retail sector today.

In several interviews it was confirmed that—up until today—the now defunct Eaton’s, the recently faltering Sears, as well as the Hudson’s Bay Company have been, in a certain sense, at the top of the food chain when it comes to the Canadian labour market in retail. Seen as prestigious downtown palaces of luxury consumption, they have attracted the best trained staff and pay relatively high wages. According to labour union representatives, organizing drives repeatedly faltered because of a strong identification of the staff with the company and the pride and joy of working for some of the flagship department stores in Canada (CAN1, CAN5).

The arrival of Walmart in Canada certainly put pressure on the established retail companies. In part, they reacted by setting up secondary chains (Zellers in the case of HBC), in order to stave off the low-cost competition. Unsurprisingly, the less desirable conditions in Zellers stores (until 2009, a fully-owned subsidiary of HBC) made them more prone to successful organizing drives by Canadian unions (CAN2, CAN5). Hence, when HBC finally decided to part ways with its Zellers operations, many unionized jobs were lost. In order to dissolve the accredited bargaining units, HBC first sold its leases to the American retail giant Target, and then officially closed the stores, thereby putting an end to that fairly well-organized chain of large-surface department stores (CAN5).

On top of the retail revolution induced by Walmart’s low-cost competition, a fundamental change in the retail sector through online shopping has left a mark on profit margins and HR practices alike. While some retail chains (as discussed later in the German case) are trying hard to adapt to the new world of online shopping, the Canadian retail industry seems to have evolved differently. It is ironic that the pioneer of home shopping, the Eaton’s catalogue, was one of the first victims of the retail revolution in Canada, with Eaton’s closing its doors permanently in 1999 (although competitor Sears maintained a certain number of stores under the Eaton’s brand until 2002).

All this is to say that Canadian labour unions have failed in their attempts to impose large-scale unionization at HBC locations in Canada. Beyond one iconic, successful fight led by the Steelworkers Union in Kelowna, British Columbia, only a handful of HBC locations in Canada have collective agreements (CAN5). One UFCW accreditation (in Victoria, British Columbia) stems from a time before closed-shop agreements were commonplace, and thus only covers a handful of employees there (CAN1, CAN2). Two stores in Ontario (both accreditations are held by UNIFOR) and a distribution centre in Saskatchewan (whose accreditation is held by UFCW) are unionized. In Quebec, the province with the highest labour union density in Canada and the most union-friendly Labour Code allowing for card-check accreditation, not a single HBC location is unionized by either les TUAC (French acronym of UFCW) or its main union competitor, the Fédération du commerce of the Confédération des syndicats nationaux (CSN). The latest attempts to unionize an HBC department store in Quebec date from the 1990s (CAN6, CAN7).

Negotiations at HBC’s unionized locations are highly centralized. Local management is not authorized to bargain, and representatives from corporate headquarters in Brampton, backed by labour lawyers from various regional offices, pull the strings (CAN3, CAN4). While there hasn’t been an active attempt at decertifying existing union accreditations, labour negotiations are far from what the literature would consider a ‘union engagement strategy’ and active suppression of organizing drives has been used elsewhere. For example, two successful organizing drives in the province of Quebec were overturned by applications for decertification, one year later, before the trade union was able to apply for binding arbitration.

It should be noted that by expanding into the US (acquisition of Sacks Fifth Avenue), HBC has taken over some historically strongly unionized retail stores in New York City. It would be a natural follow-up study to look at the evolution of HBC’s labour relations in the US.

In summary, HBC behaves as a typical union-avoiding LME company in its home-country setting. Benefiting from its position at the top of the food chain in Canadian retail, and from the bankruptcy of its main domestic challengers Eaton’s and—more recently—Sears, its workforce remains hard to organize. In addition, HBC also does not seem to hesitate to actively oppose the establishment of a labour union, when necessary. As discussed previously, the most egregious case has been the sale of the Zellers franchises to Target in 2013, causing the loss of several bargaining units and thousands of unionized jobs in Canada.

Galeria Kaufhof – a history of rocky labour relations amidst a retail industry in turmoil

Founded in 1879[1], Galeria Kaufhof, with its 97 department stores in Germany and a further 16 Galeria Inno locations in Belgium, is one of the major players in the German retail market. While the history of labour relations in the company closely tracks the trends of many large companies in coordinated market economies, it should be noted that the more recent drop in profitability had created uncertainty about labour relations at Kaufhof well before the arrival of the Canadian investors. At the time of the acquisition, relations between the management and the union was rocky, to say the least (GER4).

German labour relations are highly centralized, normally at the sector level. In the retail industry, the employer association HDE signs collective agreements with the dominant trade union Verdi for the entire retail sector (including speciality retail and supermarkets), for each of Germany’s 16 Länder (regions). However, in the past 20 years, collective bargaining coverage has eroded, either because new competitors on the market have not joined the employers’ association or because members of the employers’ association have switched to so-called OT-memberships (meaning ohne Tarifbindung—without being bound to the collective agreement negotiated by said employers’ association: GER1, GER2). German labour law long required at least 50% of the employees in a sector to be covered by collective agreements, before employers’ associations and unions could file for a generally binding extension of collective agreements. While the 50% requirement was lifted in 2009, the Ministry of Labour now has to prove a situation of “extreme inequity,” before declaring a sector-level collective agreement generally binding. So far, such an application has not been granted for the retail sector.

Within the context of near collapse and bankruptcy, many concessions had been demanded from the workers’ representatives to avoid store closures. In addition, trade unions in the German retail sector have been rocked by several high-profile blows. Notably, the employers’ association ended its commitment to generally applicable sector-level collective agreements in the early 2000s, thereby paving the way for low-wage, large-surface competition (GER1, GER3). In the wake of bankruptcy proceedings, Galeria Kaufhof’s main competitor, the Karstadt chain of department stores, managed to convince the Verdi trade union and the employers’ association to conclude a company-level collective agreement instead. Such agreements are generally accepted as exceptions to the sector-level agreement, but only when a company is on the verge of collapse. In a market, however, where two major players control the vast majority of the market share, leaving only one of the two players bound to the sector-level collective agreement has proven to be a major stumbling block for coordinated labour relations.

Similar to the Canadian case, the German retail sector has equally seen a structural retail revolution. Pressure by large-surface, low-cost competitors has been maintained, despite Walmart’s departure from the German market. Also, with store hours strictly regulated by federal and provincial laws (retail stores are still obliged to regularly remain closed on Sundays, for instance), online and cross-border shopping has ballooned in recent years. As a countervailing strategy, department stores like Karstadt and Galeria Kaufhof have only recently attempted to push back the needle of German retail towards reliance on quality customer service and individualized sales’ advice to high-end customers. Both chains have also launched online portals, experimented with cheaper in-house brands and even opened up low-cost outlet stores.

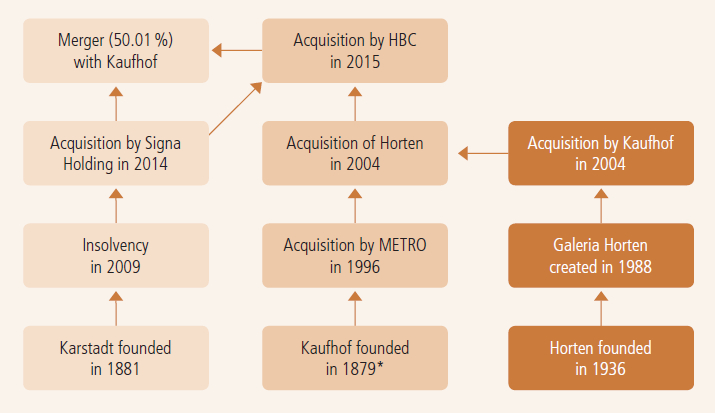

Figure 1

Past Takeovers

The retail sector in Germany had been marked by relatively stable labour relations at the sector level, at least on the surface. Despite a period of upheaval on the employers’ association side, sector-level collective labour negotiations continue to set the benchmark for working conditions and wages for much of the industry. A split between the main employers’ association HDE and its competitor BAG had persisted until 2009, leading to the development of OT-memberships as a recruitment tool on both sides (GER6). While, for the subsector of department stores, BAG never had any significance, BAG forcing HDE to embrace so-called OT-memberships and to withdraw its support for generally binding sector-level collective agreements has left an important scar on the sector. In 2009, the last elements of BAG merged into HDE. However, the latter has not revised its policies regarding either OT-memberships or general applicability (GER1, GER6).

The coordinated world of labour relations in the department store sector was put to a first stark test with the near bankruptcy and eventual restructuring of Galeria Kaufhof in 2009. After biting off more than it could chew when taking over the German number three retail chain Horten in 1994, Kaufhof was subsequently bought by food retail giant Metro group (which also acquired Galeria Inno stores elsewhere in Europe and subsequently transformed the Kaufhof brand into the current label, Galeria Kaufhof). When returns plummeted, Metro sought to sell Galeria Kaufhof, but few interested buyers appeared. Headed for bankruptcy, Galeria Kaufhof hailed the arrival of HBC as a potential saviour. The only alternative in 2015 would have been a merger with Karstadt (by then owned by the Austrian real estate investment firm Signa Holding), which would have led to many redundancies (Galeria Kaufhof and Karstadt locations in major German cities are frequently located right across from one another), and potentially risking a conflict with anti-trust regulators.

HBC’s takeover of Galeria Kaufhof

Hudson’s Bay Company was seen as a golden opportunity for Galeria Kaufhof and the sale was finalized in 2015. As sources in Brampton confirmed to us, the negative example of Walmart’s failure to take root in Germany was interpreted as a definitive warning sign not to impose North American labour relations and business models at Galeria Kaufhof (CAN8). The new ownership thus left the existing European management team largely in place and reassured the union representatives on the board of directors (German codetermination laws dictate that workers’ representatives must be included on the board of directors of any large German company) that adherence to the sector-level collective agreement would be maintained. Beyond that, HBC pursued an active engagement strategy vis-à-vis the works council and the workforce. Even trade union representatives at Verdi concede that this was a smart strategy (GER1). While the active engagement strategy towards workers’ representatives at the company level also had the effect of somewhat marginalizing the national union Verdi, one should treat all this as a clear indication for market-seeking expansion, as suggested by the literature on motivations of FDI.

However, trouble was brewing underneath. The model that was chosen to repatriate profits from Galeria Kaufhof to its parent HBC was profoundly real estate driven. In other words, rather than transferring a share of (potential) profits or losses onto its own income statement, HBC opted to leave Galeria Kaufhof as a functionally independent business venture, while simply leasing the department store locations that are owned by the parent company HBC. In fact, the financing needed for the takeover itself was largely derived from the equity of the real-estate value of the purchased locations, rather than from HBC’s own capital. As a consequence, the increased rental payments from Galeria Kaufhof (a total increase of 50 million Euro per year), especially for the top-notch real estate in the downtown cores of many Germany cities, has left the profitability of Galeria Kaufhof stores plummeting even more (Amman and Salden, 2018). These findings present a more nuanced picture of what motivation for FDI was precisely at work.

Added trouble came from centrally dictated business initiatives. HBC insisted on mandatory purchasing of new brands to be sold at Galeria Kaufhof in Europe (for instance, the British clothing line Topshop—despite having previously flopped at Karstadt). Thereby HBC has deeply shaken the confidence among previous suppliers and creditors, and it has also taken major risks regarding German consumer behaviour (GER5)—in other words, taking precisely the Walmart route. In addition, HBC applied pressure to maintain a model of deep discounts right through the midst of the busiest shopping season—Christmas—previously at the heart of high profitability at Galeria Kaufhof. Eventually all of these initiatives forced the resignation of the European management and the imposition of a new management team with previous experience at attempts in centralizing business practices, notably at Toys “R” Us Europe. By spring 2017, a match seemingly made in heaven had distinctively soured, and HBC looked a lot like following the behaviour of a typical LME player.

However, particular attention should also be paid to the significant social capital that the leadership of the employers’ association, as well as the Verdi works councillors at Galeria Kaufhof have expended in order to continue to help the local management to resist a total integration of business and labour practices within HBC, as well as to sway HBC’s headquarters to see the potential benefits of a locally-adapted model of business strategies and labour practices (GER6). On balance then, institutional and macro-level approaches alone, be they rooted in business models, FDI motivations or power resources, cannot clearly explain the distinct pattern of conflict and hybridization taking place at Galeria Kaufhof under the auspices of HBC.

Coordinated actors to the rescue

Following a near collapse of trust in the takeover and the departure of several key players, new managers at Galeria Kaufhof also threatened to leave the employers’ association fold and no longer adhere to the sector-level collective bargaining agreement. Given the absence of any legal extension of collective agreements in the retail sector and the employers’ association’s openness to OT-memberships, not much could have prevented such a move from happening. However, the tight integration of Galeria Kaufhof representatives in leadership roles on HDE’s negotiating team for the sector-level collective bargaining round in 2017, as well as the hearty interventions by the employers’ association’s leadership, seem to have staved off an immediate departure from sectoral bargaining (GER3, GER6). One should treat these findings as strong support for the institutional forces at work within a CME, as suggested by the VoC literature.

Faced with the choice to either leave the framework of coordinated bargaining relations altogether or to continue to exert a leadership role at the bargaining table, Galeria Kaufhof opted for the latter. It thereby ended up being tied into a process of which it would also have to largely carry the outcome. In this context, one could interpret the threats of leaving the collective agreement as mere posturing for purposes of a better bargaining position. However, in the end, when a company accepts to bargain, and it gets (some of) what it wanted to obtain, it no longer has good reasons to ditch the agreement afterwards. The management strategy thus seems to be stuck in between institutional and organizational push- and pull-mechanisms, leading to a distinct pattern of hybridization. As a further exemplification thereof, the managers brought in during the crisis of spring 2017 have now been shifted to HBC Europe—nominally in charge of implementing HBC’s profit model across its European operations—while Galeria Kaufhof’s German leadership was returned to a more traditional management team (GER4-6).

Additional help for CME institutions came from an interim agreement between the Verdi trade union and Karstadt, signing what was called a “bridge contract”, which would eventually permit the company to rejoin the sector-level collective agreement by 2020 (GER2, GER6). This particular agreement should be seen as an instance of creative institutional entrepreneurship on behalf of the trade union, recombining a new institutional tool born out of necessity, a company-level agreement, with an eventual return and strengthening of a more traditional coordinated labour market institution, the sector-level collective agreement.

Finally, the continued upswing in private consumption, low unemployment and general economic stability in Germany seem to have done their part in calming down HBC’s willingness to break with coordinated labour relations at Galeria Kaufhof—and risk the wrath of German consumers in what was to be the best shopping season in several decades: Christmas 2017.

Analytical discussion

While we now know that HBC and Galeria Kaufhof have ultimately parted ways, the jury is still out on the long-term impact on the labour-management relationship that has transpired during the time as the Hudson’s Bay Company’s fully-owned subsidiary. Preliminary findings allow us to conclude that HBC opted originally for an engagement strategy, defying the trend of Anglo-Saxon multinationals trying to impose their usual HR practices and union avoidance (home-country effects). That engagement strategy originally seemed to aim beyond negotiating with the labour union at the sector-level, and instead involved an active engagement of the company’s works councillors, as well as applying strategic HR management practices towards the workforce. This means that some transfer of HR practices and avoidance of coordinated institutions did equally take place from the get-go—thus pointing to an example of hybridization, as described in the institutional change literature.

The question must be asked, what the consequences are for coordinated labour market institutions if HBC really aimed at the engagement of its works councils at the expense of the national trade union, and what strategic response Verdi has in stock to react to such a potential divide-and-conquer move in the future. In other words, one form of hybridization is not necessarily equivalent to another. In order to counter such moves on behalf of a multinational, trade unions need to become “institutional entrepreneurs” themselves.

One such example seems to be Verdi’s managed acceptance of bridge contracts, effectively trying to bind the company and its works councils to resort to company-level agreements only with the perspective of eventually returning to the fold of sector-level collective bargaining. So far, Verdi has been shying away from applying other levers, such as its renowned pressure tactics, using denunciation and boycotts. It is our understanding that this is largely because it does not want to aggravate the economically difficult situation at Galeria Kaufhof and risk a negative reaction from its members there.

Neither has the trade union attempted to create an international strategy, reaching out to trade unions in the home country of HBC or in other European locations. Instead, the trade union and works council seem to go hand-in-hand, cooperating with the employers’ association when needed, and remodeling coordinated institutions where required, in order to bind HBC’s management to the coordinated labour market. All actors involved seem to expend significant social capital in the process. Once again, these are strong elements of support for the literature on institutional change, bricolage and social capital, in the context of transfer and hybridization of labour practices within multinationals.

We will never know for sure if HBC’s approach could have been compatible with its host-country institutions in the long run. As literature on foreign direct investment would have us suspect, as long as the main motivation is market access to the host country, the multinational should have fared well with respecting and adapting to coordinated labour market practices, both from a marketing and functional point of view.

However, as this study (and HBC’s recent history in Canada) equally shows, the expansion into Europe seems to have been driven in some parts by real estate speculation and related rent-seeking behaviour in the short term, which does not necessarily depend on market access. When this materialized at Galeria Kaufhof, labour unions in Germany had to be creative and resort to coordination capabilities, institutional entrepreneurship, as well as discursive capacities, in order to save their preferred coordinated labour market institutions. While legal frameworks in Canada and in Germany are not the same, German unions certainly took note of the Zellers example: when HBC switches from union accommodation to union avoidance, the real estate-based investment model provides it with powerful tools to break union resistance and, ultimately, cause the loss of thousands of unionized retail jobs, once again. It remains to be seen how the joint venture with Karstadt will unfold with the Hudson’s Bay Company now being the minority stakeholder.

Conclusion

This article has attempted to paint a picture of one particular foreign takeover in the retail market. While this is only one example of foreign direct investment by a multinational company, and the context of this economic sector is somewhat difficult so comparisons to other sectors might thus be perilous, we should nevertheless retain four principal conclusions for the literature in IR and for further study.

First, institutionalist frameworks do present a convenient backdrop for conceptualizing movements of multinationals across jurisdictions. However, one must resist the urge to predetermine outcomes by looking at host-country or home-country effects alone. Hybridization is taking place, thus opening up a significant sandbox within which strategic actors can operate.

Second, this article provides vivid illustrations of investment motives by a North American multinational, as it sets up shop in Europe for the first time. Between market-seeking investment motives paving the way for a positive engagement strategy at the outset, and short-term rent seeking motivations that won the day, later in the process, the expected correlation between management strategy and investment motivations seems to have been borne out by the results of our study.

Third, the analysis presented in this article lends support to concepts such as bricolage, recombining of institutional elements and institutional entrepreneurship, stemming from the institutional change literature. These concepts should routinely figure in one’s analytical toolbox in any attempt at non-deterministic institutional analysis. They are complementary to the institutionalist framework in that they illustrate “institutions within which real actors innovate” (Crouch, 2003: 71).

Finally, the article underscores, once more, the essential role played by sector-level actors, such as trade unions and employers’ associations. By developing, maintaining and carefully utilizing their repertoire of strategic capabilities, they contribute meaningfully to any successful adaptation of collective bargaining institutions in the context of globalization. This article should be seen as support to the literature on strategic trade union capacities in IR, albeit that Verdi did not opt for a new, transnational course of action, but rather exhibited particular resourcefulness at the national sector level and at the company level instead.

Parties annexes

Note

-

[1]

Founded and operated until 1933 under the name Leonhard Tietz AG, the chain of department stores was subject to boycott under the Nazis and was eventually bought out by a consortium of German banks, as well as renamed Westdeutsche Kaufhof AG, to hide the name of its Jewish founder.

Bibliography

- Almond, Phil, Tony Edwards, Trevor Colling, Anthony Ferner, Paddy Gunnigle, Michael Müller-Camen, Javier Quintanilla and Hartmut Wächter (2005) “Unraveling Home and Host Country Effects: An Investigation of the HR Policies of an American Multinational in Four European Countries.” Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 44 (2), 276-306.

- Amman, Susanne and Simone Salden (2018) “Wie ein deutsches Kaufhaus-Mythos zerstört wird.” Der Spiegel, 14, viewed online https://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/galeria-kaufhof-vertraulicher-firmenbericht-zeigt-den-niedergang-des-konzerns-a-1200745.html.

- Brown, William Arthur, Alex Bryson and John Forth (2009) “Competition and the Retreat from Collective Bargaining.” In William Arthur Brown (ed.) The Evolution of the ModernWorkplace, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 22-47.

- Butler, Peter (2006) American Multinationals in Europe: Managing Employment Relations across National Borders. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cleveland, Jeanette, Paddy Gunnigle, Noreen Heraty, Michael Morley and Kevin Murphy (2000) “US Multinationals and Human Resource Management: Evidence on HR Practices in European Subsidiaries.” Irish Journal of Management, 21 (1), 9.

- Cooke, William (2006) “Multnationals, Globalization and Industrial Relations.” In Michael J. Morley, Paddy Gunningle and David G. Collings (eds.), Global Industrial Relations. London and New York: Routledge, p. 326-348.

- Crouch, Colin (2003) “Innovations within which Real Actors Innovate.” In Renate Mayntz and Wolfgang Streeck (eds.), Die Reformierbarkeit der Demokratie. Innovationen und Blockaden. Frankfurt/New York: Campus, p. 71-98.

- Crouch, Colin (2005) Capitalist Diversity and Change: Recombinant Governance and Institutional Entrepreneurs. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 192 pages.

- Dribbusch, Heiner (2005) “Trade Union Organizing in Private Sector Services: Findings from the British, Dutch and German Retail Industry.” WSI Diskussions Papiere, 29 pages.

- Dufour, Christian, Adelheid Hege, Christian Lévesque and Gregor Murray (2009) “Les syndicalismes référentiels dans la mondialisation: une étude comparée des dynamiques locales au Canada et en France.” La Revue de l’IRES, (2), 3-37.

- Dufour-Poirier, Mélanie and Marc-Antonin Hennebert (2015) “The Transnationalization of Trade Union Action within Multinational Corporations: A Comparative Perspective.” Economic and Industrial Democracy, 36 (1), 73-98.

- Dunning, John H. (1998) “Location and the Multinational Enterprise: A Neglected Factor?” Journal of International Business Studies, 29 (1), 45-66.

- Edwards, Tony and Anthony Ferner (2002) “The Renewed ‘American Challenge’: A Review of Employment Practice in US Multinationals.” Industrial Relations Journal, 33 (2), 94-111.

- Elger, Tony and Chris Smith (2006) “Theorizing the Role of the International Subsidiary: Transplants, Hybrids and Branch-Plants Revisited.” In Anthony Ferner, Javier Quintanilla and Carlos Sanchez-Runde (eds.), Multinationals, Institutions and the Construction of Transnational Practices, London: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 53-85.

- Ferner, Anthony, Javier Quintanilla and Carlos Sanchez-Runde (2006) “Introduction.” In Phil Almond and Anthony Ferner (eds.) American Multinationals in Europe: Managing Employment Relations across National Borders. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, p.1-23.

- Fitzenberger, Bernd, Karsten Kohn and Qingwei Wang (2011) “The Erosion of Union Membership in Germany: Determinants, Densities, Decompositions.” Journal of Population Economics, 24 (1), 141-165.

- Frege, Carole, John Kelly and John E. Kelly (2004) Varieties of Unionism: Strategies for Union Revitalization in a Globalizing Economy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Hågnell, Christian (2002) Local Responsiveness of Human Resource Management Strategies and Practices within a Nation: A Study of Walmart Germany. Doctoral dissertation, Graduate Business School.

- Hall, Peter A. and David Soskice (2001) Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 540 pages.

- Hamann, Andreas and Gudrun Giese (2004) Schwarzbuch Lidl. Billig auf Kosten der Beschäftigten. Berlin: Verdi Trade Union, 140 pages.

- Højgaard Christiansen, Laerke and Michael Lounsbury (2013) “Strange Brew: Bridging Logics via Institutional Bricolage and the Reconstitution of Organizational Identity.“ In Michael Lounsbury and Eva Boxenbaum, Institutional Logics in Action, Part B. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited, p. 199-232.

- Huzzard, Tony (2004) “Boxing and Dancing: Trade Union Strategic Choices.” In Tony Huzzard, Denis Gregory and Scott Regan (eds.) Strategic Unionism and Partnership. Boxing or Dancing? London, UK: Macmillan, p. 20-44.

- Kochan, Thomas A., Robert B. McKersie and Peter Cappelli (1984) “Strategic Choice and Industrial Relations Theory.” Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 23 (1), 16-39.

- Korpi, Walter (2006) “Power Resources and Employer-Centered Approaches in Explanations of Welfare States and Varieties of Capitalism: Protagonists, Consenters, and Antagonists.” World Politics, 58 (2), 167-206.

- Kristensen, Peer Hull and Jonathan Zeitlin (2005) Local Players in Global Games: The Strategic Constitution of a Multinational Corporation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 364 pages.

- Laroche, Mélanie, Marie-Ève Bernier and Mathieu Dupuis (2015) “Du caractère multidimensionnel des tactiques antisyndicales: constats empiriques québécois.” Canadian Labour and Employment Law Journal, 18 (2), 557-593.

- Lévesque, Christian and Gregor Murray (2010) “Understanding Union Power: Resources and Capabilities for Renewing Union Capacity.” Transfer, 16 (3), 333-350.

- Lichtensetin, Nelson (2009) The Retail Revolution: How Walmart Created a Brave New World of Business. New York: Metropolitan Books, 311 pages.

- Liu, Larry (2014) Codetermination: Trade Union Power in Germany and the US. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University, www.academia.edu, 14 pages.

- Mabbett, Deborah (2016) “The Minimum Wage in Germany: What Brought the State In?” Journal of European Public Policy, 23 (8), 1240-1258.

- Marginson, Paul and Keith Sisson (2002) “European Dimensions to Collective Bargaining: New Symmetries within an Asymmetric Process?” Industrial Relations Journal, 33 (4), 332-350.

- Martin, Anthony and George Ross (1999) The Brave New World of European Labor: European Trade Unions at the Millennium. Oxford, UK: Berghahn Books, 416 pages.

- Martin, Anthony and George Ross (2001) “Trade Union Organizing at the European Level: The Dilemma of Borrowed Resources.” In Douglas R. Imig and Sidney G. Tarrow, Contentious Europeans, Protest and Politics in an Emerging Polity, Lanham, Marylan: Rowman and Littelfield Publishers Inc., p. 53-76.

- Meardi, Guglielmo, Paul Marginson, Michael Fichter, Marcin Frybes, Miroslav Stanojevic‘ and András Tóth (2009a) “The Complexity of Relocation and the Diversity of Trade Union Responses: Efficiency-Oriented Foreign Direct Investment in Central Europe.” European Journal of Industrial Relations, 15 (1), 27-47.

- Meardi, Guglielmo, Paul Marginson, Michael Fichter, Marcin Frybes, Miroslav Stanojevic‘ and András Tóth (2009b) “Varieties of Multinationals: Adapting Employment Practices in Central Eastern Europe.” Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 48 (3), 489-511.

- Ochel, Wolfgang (2005) “Decentralizing Wage Bargaining in Germany—A Way to Increase Employment?” Labour, 19 (1), 91-121.

- Peters, John (2010) “Down in the Vale: Corporate Globalization, Unions on the Defensive, and the USW Local 6500 Strike in Sudbury, 2009-2010.” Labour/Le Travail, 66 (1), 73-105.

- Pioch, Elke, Ulrike Gerhard, John Fernie and Stephen J. Arnold (2009) “Consumer Acceptance and Market Success: Walmart in the UK and Germany.” International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 37 (3), 205-225.

- Seawright, Jason and John Gerring (2008) “Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options.” Political Research Quarterly, 61 (2), 294-308.

- Sisson, Keith, J. Arrowsmith and Paul Marginson (2003) “All Benchmarkers Now? Benchmarking and the ‘Europeanisation’ of Industrial Relations.” Industrial Relations Journal, 34 (1), 15-31.

- Sufrin, Eileen (1983) The Eaton Drive: The Campaign to Organize Canada’s Largest Department Store, 1948 to 1952. Markham, ON: Fitzhenry and Whiteside, 240 pages.

- Taylor, Sully (2006) “Emerging Motivations for Global HRM Integration.” In Phil Almond and Anthony Ferner (eds.) American Multinationals in Europe: Managing Employment Relations across National Borders. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, p. 109-128.

- Walsh, Janet, Gianni Zappala and William Brown (1995) “European Integration and the Pay Policies of British Multinationals.” Industrial Relations Journal, 26 (2), 84-96.

- Whitley, Richard (1999) Divergent Capitalisms: The Social Structuring and Change of Business Systems. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 301 pages.

Liste des figures

Figure 1

Past Takeovers

Liste des tableaux

Table 1

Research Questions and Indicators

Table 2

Interviews